THE ROAD to Bernard Faÿ’s house in Luceau winds straight through the middle of the Loire valley in west-central France—a place of flat, lush farmland and large skies, of meandering vineyards and provincial towns. Known for its wines, its chateaux, and its cathedrals, the Loire is a region steeped in history. France’s most famous cathedral, Chartres, is just to the north, hauntingly beautiful as it rises out of the flat misty plains. Nearby are the famous chateaux of Blois, Chambord, Chenonceau, Chinon—fairy-tale castles of the French Middle Ages and Renaissance, visible reminders of the glory of the French aristocracy. Joan of Arc led the defeat of the English at the Loire town of Orleans in 1429; some five hundred years later, in 1940, Philippe Pétain shook the hand of Adolf Hitler in a notorious collaboration ceremony at the eastern Loire town of Montoire.

Luceau, a tiny hamlet outside the provincial center of Chateau-du-Loir, in the département of the Sarthe, was the spot Faÿ chose when he went searching for a country house in the late 1930s. With his deep sense of connectedness to prerevolutionary France, Faÿ was naturally drawn to the Loire valley. In Luceau he found his dream house—an elegant stone priory connected to a small twelfth-century church, which he purchased for 35,000 French francs on September 18, 1939.1 To the end of his life, Faÿ found solace and peace in this place. It was to Luceau that he retired during the war when the pressures of Vichy became too much to handle. And it was along the tree-lined road to Luceau that Gertrude Stein traveled for a summer vacation in 1946 at the invitation of Faÿ, who was still sitting in the prison at Fresnes, awaiting his trial for collaboration with the Nazis.

Stein only stayed at Luceau for a few days. Suddenly crippled with the abdominal pain that had been bothering her for months, she was rushed to the American Hospital in the Paris suburb of Neuilly, where she succumbed on July 27, 1946, at 7 p.m. to uterine cancer.2 Her death at the age of seventy-two came as a shock to the many friends, acquaintances, and admirers who had never perceived Stein as anything but enormously vital. As an American friend wrote to Alice Toklas: “There seemed to be a permanence in Gertrude that belongs to no one else I have ever known.”3 For her own part, Toklas, bereft, referred to the moment Stein died as the beginning of “the empty years,” the twenty-one years she would live on alone without Gertrude.4 “Now she is gone and there can never be any happiness again,” she wrote.5

Shocked by the loss, Bernard Faÿ too wondered how he would soldier on. “I lost more and better than a friend,” he mused. “I lost a woman who helped me to love life.”6 Writing to Toklas, he returned to what had always seemed so strong in Stein, her joie de vivre:

She has been one of the few authentic experiences of my life—there are so few real human men and women—so few people really alive amongst the living ones, and so few of them are continuously alive as Gertrude was. Everything was alive in her, her soul, her mind, her heart, her senses. And that life that was in her was at the same time so spontaneous and so voluntary. It is a most shocking thing to think of her as deprived of life.7

Years later, Faÿ remembered feeling glad that Stein had spent the end of her life at Luceau, where “all the objects spoke to her of me, and the walls, decorated with her books, recalled for her our friendship.” And he remembered as well the central lesson she had taught him: “to love the rich tissue of existence” without feeling “disgust” and “anger.”8 “The most useful knowledge is what Gertrude taught me with her easy ways, her broadmindedness, and her gay understanding of people,” he wrote Toklas in 1947.9 Struggling within his postwar “prisons”—literal and psychological, moral and spiritual—Faÿ attributed any moments of serenity to this remembered influence of Gertrude Stein.

For the next five years, Faÿ would indeed know nothing but life in prison. After his trial and sentencing in December 1946, suffering from cardiac trouble, he was sent to the prison hospital on the Île de Ré, an island off the west coast of France. He remained there from January 1947 to August 1950, when he was transferred to Fontevrault, a prison that, with an average of two deaths per week, was widely considered one of the harshest in France. At Fontevrault, his health seems to have rapidly deteriorated, causing him to be transferred to the nearby hospital at Angers. It was there where Faÿ would plan, and successfully carry out, his escape to Switzerland.10

Toklas, supported “for life” by Stein’s will, spent several relatively secure years in Paris after the war, first as the grieving widow and then as an emerging writer in her own right (“As for Alice, she is now running the whole show and seems to be thriving. Talks just as though she were the original Stein,” wrote Sylvia Beach to Richard Wright in 1947).11 Yet Toklas was eventually robbed of most of her livelihood by legal maneuvers among Stein’s relatives. The story of how Stein’s increasingly valuable art collection was literally spirited away from her apartment while Toklas was taking a health cure in Italy is the stuff of legend. Her subsequent destitution was, according to all who saw her, heartbreaking. Nevertheless, in part thanks to Bernard Faÿ, Toklas too would eventually be “saved” by a late-life conversion to Christianity.

Only Gertrude Stein would triumph after the war, her death arriving at a moment of renewed celebrity and long before the depredations of old age could diminish her capabilities. Rediscovered at the Liberation by American GIs and journalists, Stein immediately became a symbol of survival and fortitude for Americans at home and abroad. With her broad smile, homespun aura, and patriotic fervor, Stein embodied the image of healthy, uncomplicated American values triumphing over European decay and despair. Returning to Paris with Toklas in December 1944, Stein found herself again hosting a regular salon, this time made up of a mix of old acquaintances and freshly minted American GIs. Back in the United States, Stein enjoyed a resurgence of the media attention she had experienced ten years earlier. The publication of Wars I Have Seen in 1945 put Stein on the covers of Publishers Weekly and the Saturday Review of Literature. But her biggest coup was a multipage Life magazine spread on August 6, 1945, featuring photos of Stein and GIs touring postwar Germany, accompanied by a text written by Stein, “Off We All Went to See Germany.”12 In a telling example of their divergent fates, this celebratory article appeared almost three years to the day after Bernard Faÿ had been named in Life on a “Black List” of French collaborationist writers.

Reading this article today—knowing what we do about Stein and the Vichy regime—may well cause some discomfort. The jaunty humor and blithe tone of Stein’s text is jarring in relation to the sober subject at hand. “One would suppose that every ruined town would look like any other ruined town but it does not,” Stein quips in this piece, as though comparing types of breakfast cereal. “Roofs are in a way the most important thing in a house … and here was a whole spread out city without a roof,” she wonders with faux-naïve amazement about the bombed-out city of Cologne. A photo of Stein among a group of soldiers performing the Hitler salute at his bunker in Berchtesgaden seems at once sophomoric and chilling, given Stein’s attraction to authoritarianism in the 1930s and 1940s. In one of the few serious passages of the text, Stein criticizes the American soldiers for believing in the duplicitous “flattery” of Germans, yet her entire piece in turn both flatters and belittles her American cohorts, who are at once endearing young men and “big babies.” Throughout this article, indeed, Stein seems to want both to celebrate and to mock the American liberation, preventing us from grasping the supposedly “critical, satirical edge” that one critic has noticed in Stein’s visual and written position in this piece.13

FIGURE 6.1 Gertrude Stein and American GIs at Berchtesgaden.

SOURCE: COPYRIGHT GETTY IMAGES

No doubt some contemporaries were also made uncomfortable by the Life article, with its disconnect between tone and subject, affect and focus. In fact, there were a few people, such as Bennett Cerf and Saxe Commins at Random House, who acknowledged outright that they found Stein’s postwar stance disturbing. Commins referred to her political views in Wars as “at best reactionary and at worst reprehensible.”14 Cerf, who had received the proposal for Stein’s introduction to the speeches of Pétain, was already well aware of what he called her “disgusting” views—an opinion he freely shared with her.15 Yet the Life article was clearly meant to capitalize on Stein’s previous celebrity and on the quirky character she had personified so successfully in The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas and her American lecture tour of 1934–1935, now somewhat disconcertingly transplanted into the apocalyptic wasteland of postwar Germany. In other postwar media events, Stein began to be referred to as “Gerty,” a long-lost friend and patriotic mother-figure for GIs abroad. She seemed only too happy to play this role in her postwar appearances and writing, even collaborating with Virgil Thomson on a highly autobiographical new opera, “The Mother of Us All,” which portrays the suffragette Susan B. Anthony orienting her nation within a progressive narrative of freedom and empowerment.16

Two of the several texts Stein wrote at the end of her life suggest the complexity of her postwar stance. In the narrative play Brewsie and Willie, Stein uses her characters as a platform to put forward an uneasy mix of patriotism and reactionary criticism. Brewsie and Willie are both American GIs located within an indeterminate postwar landscape of possibility and despair. Their dialogue centers on the future of America, and the scenarios put forth by Brewsie in particular are far from reassuring. While both Brewsie and Willie are thoughtful and curious figures—the best of American men, Stein would say—both are also dire national prophets. Their comments about the double standards facing black American soldiers are particularly prescient and reveal Stein’s newfound attention to American racism. Yet, in other ways, the book shows Stein rehearsing familiar political views about the United States, including the line from the 1930s that Left politics will only rob America of its wealth and essential independent spirit. Stein has Brewsie utter this line, and it is clear that she shares his views when, in the book’s epilogue, she directly addresses her audience:

To Americans … We are there where we have to fight a spiritual pioneer fight or we will go poor as England and other industrial countries have gone poor, and dont [sic] think that communism or socialism will save you, you just have to find a new way, you have to find out how you can go ahead without running away with yourselves, you have to learn to produce without exhausting your country’s wealth, you have to learn to be individual and not just mass job workers, you have to get courage enough to know what you feel and not just all be yes or no men.17

The specter of a mass of overworked yes-men enslaved to the ideology of production seems as potent in this address to the reader from 1945 as it did in Stein’s political comments from the 1930s. Even at this late date, Gertrude Stein continued to see “communism” or “socialism”—identified always in her mind, as her 1935 articles on money make clear, with the “organization” of Franklin D. Roosevelt—as the greatest threat to the American spirit.

Brewsie and Willie is a strange and unprocessed mix of reaction and enlightenment, patriotism and critique. Yet in a less well-known play written immediately after, and about, the war—In Savoy; or, Yes Is for a Very Young Man—we see another side of the postwar Gertrude Stein emerge. Unlike Wars I Have Seen or “The Mother of Us All,” Stein in this late play avoids featuring herself in a narrative of uplift and triumph. Unlike Brewsie and Willie, Stein doesn’t use the text as a platform to announce her fears about American decline. Rather, Yes Is for a Very Young Man stands as a unique text in Stein’s oeuvre. Stein uses the characters within this play to foreground multiple and often contradictory perspectives, putting on display the “gray zone” of life during wartime. There is Denise, the Pétainiste and fervent anticommunist who believes in taking sides and laments the demise of the “dear marshal.”18 There is Ferdinand, the young Resistance fighter and “silly boy” who stands for love and “disobedience.” And finally there is the Constance, the intelligent but complacent American who watches in dismay as her lover Ferdinand takes his leave from her to join the “organization” of the Resistance. All of these figures are tied together in a morally ambiguous landscape where executions, bloody revenge, and the rending apart of families characterize everyday life. Learning how to say “yes” to this life despite its despair is the only moral of this story, one that perhaps speaks to Stein’s own mature awareness of the difficulty and inevitability of moral judgment during wartime.

On another level, Yes Is for a Very Young Man questions the idea of war as meaningful, something from which we can take away a lesson to be applied in other contexts. It makes a strong case for the importance of sheer survival in the midst of chaos. And this may be the most useful knowledge Gertrude Stein offers us out of her experience with World War II and its aftermath. It is a lesson to heed when we find ourselves wanting to be assured that Stein emerged from the war with her prewar views and leanings clearly changed. Yet Stein’s postwar stance offers us no such assurance. In fact, it brings us little closure on the problem of how to understand the relationship between her experimental aesthetics and her reactionary politics. Like her fellow modernists drawn before the war to the political Right—Ezra Pound or T. S. Eliot, Louis-Ferdinand Céline or William Butler Yeats, to name just a few—Stein was taken by the promises of political authoritarianism, always complexly tied to her sense of her own genius and of the “free creative spirit … without limits” that coursed through her aesthetic. Yet while the war turned Pound and Céline into hardcore fascists, while Eliot retreated into the largely religious meditations of Four Quartets (1943), and while Yeats was spared the whole ordeal, Stein’s experience during the war seems not to have changed her mind about much. Neither rabid nor resigned, Stein survived World War II—and emerged from it with her views on America, on Pétain, and on the overriding value of tradition, peace, and everyday life more or less intact.

In Yes Is for a Very Young Man Stein demonstrates why this might be so. Neither hastily patriotic nor bitterly vengeful, Yes presents a vision of war as “pretty bad” and then “over”: an event outside the range of discussion and argument. No decision that is made during this period is a good one; no argument is justifiable. “Peace” is achieved not through well-meaning compromise or pacifist commitments but through an arbitrary end to senseless violence. But its achievement is reason enough for continuing on. In the end, Yes suggests, there is simply the fact of survival and the affirmation of vitality that this fact brings with it: “Yes.”

The stark image of Stein stricken by the cancer that would kill her while visiting Faÿ’s empty country house in 1946 seems somehow representative of the endgame of their relationship. With Stein’s death, this twenty-year relationship came to its natural end, yet in fact the end had been foreshadowed for several years. Shared interests had brought Stein and Faÿ together—the entwined histories of America and France, modernist writing and art, reactionary politics, homosexuality, and a simple love of talk—and for many years the two had enjoyed one of the closest collaborations of their lives. Yet the separate and mutual collaboration of each with Philippe Pétain’s Vichy regime would end up weakening this bond, and it would never again be the same as it was before the war. One of the points of this book has been to show how deeply fascist and profascist politics divided and severed human beings from one another, creating invidious, dehumanizing racial, national, and religious distinctions that would eventually result in the “death world” of World War II. The story of Stein and Faÿ’s friendship is a compelling personal story, but it also captures in microcosm the shape of this era.

Still, if there is any reckoning to be made about the friendship between Gertrude Stein and Bernard Faÿ, we might point to the fact that after Stein’s death Faÿ seemed to retreat into an ever more isolated, dogmatic, and reactionary worldview. This is apparent during the years Faÿ spent in exile in Switzerland and for the rest of his life after his official pardon in 1959. As Antoine Compagnon has written perceptively:

This man, whose intellectual and worldly career had been extraordinarily successful between the two world wars—his existence very full despite his infirmity—had lived at an intense pace between 1919 and 1940 … ; he had [now] become a recluse after seven years of prison, a discreet decade in Catholic Switzerland, and a bitter retirement in his house in the Sarthe region, with no more Gertrude Stein to distract him from his traditionalism and to enlighten his conservatism.19

The implication that Stein, while she was alive, saved Faÿ from extremism in his thinking and writing brings a new twist to their relationship. It suggests that however much their political views ran parallel during the interwar period, their collaboration was also kept in check by countervailing tendencies, especially on the part of Stein, toward democratic, liberal, and “enlightened” ways of thinking. At the very least, her sheer presence—Jewish, homosexual, and American, identity markers with increasing visibility from the start of the war on—would have been a reminder to Faÿ of earlier affinities and attractions that had not yet been rejected or incorporated into an extremist worldview. And while their shared dialogue during the interwar period propelled both into the troubled midst of the Vichy moment, only Stein seemed capable of reassessing after the war—however tentatively—her wartime actions and views. For Faÿ, it is clear, there was no going back.

After the war, and after Stein’s death, Faÿ’s stance toward the world around him became one of ever greater animosity. Most importantly, his aesthetic connection to the world of art and letters—embodied in his relationship with Stein—was increasingly given over to a religious worldview dominated by clear divisions between saints and sinners, virtue and vice, redemption and corruption. This is an important point that goes to the heart of Stein and Faÿ’s collaboration. As this book has attempted to show, Stein and Faÿ were drawn to each other through a shared political and historical vision, one steeped in an eighteenth-century ethos at odds with the industrialized, technocratic era of modernity. Both also saw themselves as future-oriented in rejecting the “communist” orientation of France and American and in anticipating the radical political vision of Philippe Pétain’s National Revolution. Their attraction to each other revolved around this playful vacillation between conservatism and revolution. In their sense of a shared mission the two friends allowed each other to have it both ways. But Stein and Faÿ also had an aesthetic bond that coursed through and beyond politics. For Faÿ in particular, there was the sheer pleasure—the “joy”—that Stein’s extraordinary linguistic experimentation offered him, her devoted reader and translator during the 1920s and 30s. Her writing was for him not just political but also intellectual, emotional, erotic, and instinctually vital. For such an ambitiously political individual, Faÿ’s response to Stein’s writing as brilliant, profound, and joyous seems, in hindsight, at once anomalous and fascinating—a sign of aesthetic openness that was lacking in other facets of his life.

In an important way, then, Stein’s death paralleled the death, for Faÿ, of this aesthetic openness. From the Vichy regime onward, Faÿ became increasingly rigid, increasingly self-righteous. Indeed, as his trial for collaboration made evident, Faÿ seems never to have felt any remorse for his Vichy-era activities. Even in his private prison diary, with its discourse of expiation, Faÿ consistently justified his actions by arguing that his single goal was to save France from the decadent elements in its midst as well as from rampaging occupiers. The latter seemed always to justify the former; protecting France also meant cleaning it up. Resolutely unrepentant, a Pétainst to the end, Faÿ after the war found himself allied with a new and ever more rigid group of interlocutors. Many of these were ex-Vichy ideologues who looked to the rise of Pétain’s movement—rather than its downfall—as evidence that a new form of political organization could take root in France. Some of these figures had been colleagues of Faÿ in the prewar European federalist movement, a movement that after the war ceded its ground to the more progressive movement to create an economic Council of Europe. The postwar environment forced these men to take their politics underground, but it seems not to have dissuaded them from adhering to their positions.20 And even from their postwar prisons, the prewar Right found a ready network of international interlocutors and publishing ventures that would help them broadcast their views. One of these interlocutors was a man with whom Faÿ had had a close correspondence in the late 1930s, a man who shared with Faÿ both a deep sense of history and a Catholic and authoritarian worldview: Gonzague de Reynold, the eminent professor of French literature at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland.

One of the most renowned and eloquent proponents of Swiss nationalism during the interwar period, de Reynold advocated in the 1930s a “third way” between liberalism and communism centered on aristocratic and Catholic values. With his noble particule and eighteenth-century dress, de Reynold seemed to live a life where “time had stood still,” and his values were inherently attractive to Bernard Faÿ.21 As with Faÿ, de Reynold’s opposition to the French Revolution and the Catholic traditionalism he had inherited from his family would define him; alongside Faÿ, de Reynold would take part in such activities as an annual commemoration of soldiers killed protecting the French monarchy in 1792.22 And again like Faÿ, de Reynold’s ultratraditionalism would inevitably be co-opted by the Nazis, especially by intellectuals and ideologues who had no trouble manipulating the slippage between Catholic authoritarianism and fascist totalitarianism. Although de Reynold had been intrigued by the idea of a Catholic and Latin “federation” of dictatorships as an alternative to modern liberalism, this idea also would play right into the decidedly secular plans of the Nazis. One Nazi intellectual, the German jurist Hans Keller, was likely the figure who introduced Faÿ and de Reynold. It was Keller who had himself first published in Switzerland a work entitled The Third Europe, devoted to the idea of an “ideal” national socialism of independent nations connected through “supranational peace.” Predictably, Keller argued for the sanctity of national “identity” and “cultural values” under the protection of a German-dominated Europe. Keller’s organization, the Academy of the Rights of Nations, had solicited the views of both Faÿ and de Reynold, even bringing Faÿ to Berlin in March 1937 to give a speech on the subject of the looming threat of communism in the United States.23 Two years later, Faÿ and de Reynold would appear together in a book edited by Keller, Der Kampf um die Völkerordnung (The Battle for a People’s Order) as academy representatives in their respective countries.24 They had already worked together in 1938 to nominate Charles Maurras for the Nobel Peace Prize, and by the start of the war they had a voluminous shared correspondence.25

Gonzague de Reynold appears to be the friend who moved into the vacuum created in Faÿ’s life by the loss of Stein. He would prove to be essential to Faÿ’s postwar activities, providing a sounding board for his ideas and the intellectual and institutional cover to keep his enemies at bay, at least for a time. But Faÿ’s actual route to exile in Switzerland, starting with his dramatic escape from prison, would be made possible by the combined efforts of a small circle of friends and fellow postwar reactionaries. And once in Switzerland, Faÿ would feel right at home in the atmosphere of familiar faces in the cities clustered around Lac Léman (Lake Geneva), a place so full of ex-collaborators that after the war it earned the unhappy title of “Vichy-sur-Léman.”

FIGURE 6.2 New York Times announcement of Faÿ’s escape from prison (1951).

SOURCE: COPYRIGHT THE NEW YORK TIMES

In his memoirs, Faÿ writes that sometime during the course of 1951, during his stay at the Fontevrault prison, his health took a sudden turn for the worse. He was rushed to the municipal hospital in the nearby town of Angers. “Death was coming along slowly, and then more rapidly,” he writes. “When I felt it approaching, I decided to escape.”26 However the dying Faÿ mustered the strength to flee across France for Switzerland, he was apparently aided in his efforts by the financial support of Alice Toklas.27 Her help served him well. Crossing the border in disguise on the morning of October 1, 1951, Faÿ found a brand new life awaiting him in exile. Not only would he survive his escape, but he would live on for almost three more decades, to the ripe old age of eighty-five. He would date each passing year after this event in terms of his Christ-like resurrection (“Resurrectionae meae Anno I, II, III,” etc.).

The story of Faÿ’s escape from prison is a dramatic one. According to his own account in his memoirs, as well as to the official police report from Angers, events began unfolding on September 29, 1951. During that day, an unusual young woman was spotted in an alleyway underneath Faÿ’s hospital window, dressed in an alpine-style pointed hat and blue cape with the insignia of the Red Cross. The following day, a Sunday, the same woman appeared at the hospital Mass, which Faÿ too attended, under the watch of his guard Francis Meignan. Leaving Mass together, Faÿ “accidentally” jostled the young woman—earning a rebuke from Meignan and creating enough confusion to slip the woman a note. Returning to his room, he asked Meignan if he could use the bathroom, which was located down a dark hallway. Meignan, knowing Faÿ suffered from a heart condition and “walked shufflingly and only with great effort,” agreed to let Faÿ go alone. Fifteen minutes later, Meignan found the bathroom empty and realized that Faÿ had disappeared. An intern of the hospital later reported seeing a young blonde woman in a navy cape leading an elderly man through the side gates of the building. By the time the police in Angers were alerted, at four that afternoon, Faÿ and his companion were already halfway across the country.28

Slipping across the border dressed in a cassock, Faÿ entered Switzerland early on the morning of October 1. His anonymous French benefactress—probably a young woman named Jeanne Marie Therese Bigot—handed Faÿ over to the warm embrace of reactionary Swiss friends and fellow French collaborators.29 The anti-Semitic writer Paul Morand, the Pétainist intellectuals René Gillouin and Alfred Fabre-Luce, Abetz’s friend Jacques Benoist-Méchin, and Henri Jamet, the director of the collaborationist Paris bookstore Rive Gauche were just a few of the Vichy allies who surrounded Faÿ in Switzerland. Other friends came from the wealthy elite of right-wing French-speaking Switzerland. One of Faÿ’s first stops after his arrival in Switzerland was at the home of Lucien Cramer, a lawyer, journalist, and historian who wrote on the Swiss nobility, including his own family. His sumptuous villa in the eastern suburbs of Geneva was also the meeting place for an international organization devoted to fighting the spread of communism. It was at the Cramer villa where Faÿ would receive his mail, addressed to him under his Swiss pseudonym: Pierre Conan.30

Henry Rousso has eloquently described this postwar Swiss setting as a “provisional crucible” of ex-collaborators who lived, wrote, and “discoursed at length about a more-than-uncertain future while awaiting better days.”31 The holding pattern of these “exiles”—as Faÿ called himself, to avoid the unpleasantries associated with being a fugitive—was marked by a shared bitterness toward the course of present-day history and an increasingly black-and-white sense of the future. Writing about his “liberation” onto the streets of Geneva in October 1951, Faÿ nevertheless turned his mind to darker thoughts: “I realized that … up to my death, I would be, like everyone else, captive to madness, to violence, and to hatred over which no-one would triumph until the birth of a new and divine wisdom.”32 Faÿ equated the birth of this new day with two events: the moment when he would be pardoned by France and allowed to return home to his native country and the time when bolshevism, communism, and/or leftism would finally cede to a “rebirth” of traditional “wisdom.”33 This would be the vision to which he devoted himself with increasing religious fervor until the end of his life.

Aside from a brief stint teaching in Madrid from October 1952 to May 1953, Faÿ would call the French-speaking cantons of Switzerland home for the next decade. There he would be aided by the Catholic intelligentsia as well as by certain high-ranking authorities in the Swiss federal administration and police force who were favorably inclined toward his political position. Already known as a refuge brun (“brown refuge,” after the color of the Nazi uniforms) for its covert willingness to aid fugitive Nazis, Switzerland after the war accepted an array of French ex-collaborators ranging from high-ranking ministers to more radical collaborationists. According to Luc van Dongen in his recent book on Switzerland as a “transitional zone” for ex-Nazis and their collaborators, one has to take seriously the possibility that certain elements within Switzerland welcomed these figures as refugees “out of respect for their fundamental principles.”34 Such would be the case with Faÿ’s former assistant William Gueydan de Roussel, who, despite having been identified to the Swiss authorities as a Gestapo agent in early 1945, was still able to find work in the Swiss federal government before the war had even ended.35 This political bias—or willful blindness—on the part of certain Swiss authorities may explain the ease with which Faÿ was able to travel and work within a matter of months after arriving in Switzerland. It also explains why Faÿ was granted refugee status by the Swiss state as early as 1953.36

Arriving in the small Swiss town of Fribourg in December 1951, Faÿ at last found a place where he could settle, a profoundly Catholic environment where he could finally enjoy the Christian holidays of Christmas and Lent. He was soon surrounded by aristocratic friends—Philippe de Weck, the former head of the Swiss bank UBS; Viscount Georges de Plinval, a right-wing dean at the University of Fribourg;37 Count Raoul de Diesbach and his son Frédéric, the editor of La Revue Anticommuniste; and the equally anticommunist Swiss diplomat Carl Jacob Burckhardt. Doctor Walter Michel, the head of the Mouvement National Suisse, a fascist group active in Switzerland during World War II, was a faithful ally to Faÿ, just as he had been to Faÿ’s former assistant Gueydan de Roussel.38

But most important to Faÿ’s well-being in Fribourg was Gonzague de Reynold, a man who seems to have replaced Stein in Faÿ’s affections after the war. Correspondents since before the war, Faÿ and de Reynold became intimate friends after it. Manifesting the same combination of hard-headed political critique and demonstrative banter, the correspondence between the two intellectuals of the Right recalls the Stein-Faÿ correspondence from the 1930s. As with Stein, Faÿ flattered the elder de Reynold, praising him for the gift of his friendship and for his stimulating companionship during an otherwise bleak moment of history.39 As with Stein, Faÿ seems to have appreciated the “virility” of his friend, referring to de Reynold as a salutary counterforce to the “feminine” twentieth century.40 In turn, de Reynold, like Stein, praised Faÿ for being a cultural intermediary between France and his own native country. Both pairs of friends laced their correspondence with sharp observations about the decadence of their times and the menace of communism.

But there are several telling differences between the two sets of correspondence. Above all, Faÿ appealed to de Reynold on the grounds of a shared religious faith, even implicitly comparing the latter to Christ.41 Where Stein’s Jewishness remained at times a point of difference between herself and Faÿ, there was no such sensitivity regarding de Reynold. Likewise, Faÿ felt no compunction about disparaging what he called “Judeo-American” politics with de Reynold. And Faÿ’s rhetoric becomes even sharper in the hearing of de Reynold: describing a trip to Solesmes Abbey in France, Faÿ registers disgust at the unholy juxtaposition between the ancient monastery and the heterogeneous racial and cultural mix of the French tourists around him.42 In this and other letters, the two aging reactionaries solidified their postwar bond by means of a vocabulary that was at once pious, bitter, and uncomprehending—far different from the energetic right-wing critique shared by Stein and Faÿ in the 1930s.

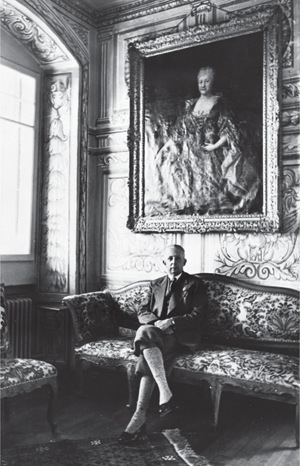

FIGURE 6.3 Gonzague de Reynold, in eighteenth-century breeches (1940).

SOURCE: COPYRIGHT PRINTS AND DRAWINGS DEPARTMENT, SWISS NATIONAL LIBRARY, BERNE.

Gonzague de Reynold, a figure who as a boy had been coached by his aristocratic mother to publicly snub the bourgeoisie, would facilitate Faÿ’s entry into Fribourg high society.43 Although Faÿ himself had bourgeois origins, his much-published defense of the aristocracy and his Catholic piety effectively gave him a free pass into the Fribourg nobility. It was also de Reynold who would help Faÿ secure teaching positions at various institutions around town.44 With its strong reputation for hosting the foreign-study programs of American institutions including Georgetown, La Salle College, and Rosary College, Fribourg was the perfect place for Faÿ to not only survive but thrive. The modest family income on which he had been living was soon supplemented by work. Because of his scholarly background and teaching experience, Faÿ found himself a regularly employed adjunct professor in both Fribourg and at a high school in Lausanne. Eventually, in 1957, he became a chargé de cours (lecturer) at the Institute of French Language at the University of Fribourg. It was a far cry from the Collège de France but certainly better than Fontevrault prison. Gradually, through his contacts with de Reynold and others, Faÿ developed a circle of sorts: Fribourg nobility, fellow French “exiles,” and a gaggle of students who knew nothing of his past but who enjoyed his elegant social teas, held every week at five o’clock at his house on the Grand Rue.45

But even more it was Gonzague de Reynold, again, who helped Faÿ develop an association with the religious conservatives centered in Fribourg. A town of some thirty thousand inhabitants, of whom the majority are Catholic, Fribourg has long been known as “a small island of traditionalism.”46 As its “spiritual head” during the 1950s and 1960s, de Reynold shared with many of his neighbors a deeply conservative understanding of Catholicism.47 A central tenet was the belief in a strict interpretation of the faith based in the traditional Tridentine Latin mass. Tied to this belief was an equally strong sense that the Catholic faith had lost its moorings and that the Church of Rome was increasingly moving toward a troubling reconciliation with contemporary values. The modernizing and secularizing reforms of Vatican II (1962–1965) were imminent. Sensing this, de Reynold and other members of the Fribourg Catholic elite felt themselves to be the last bastion of standards keeping the church from sliding into modern decadence. Their discontent would prove enormously attractive to Bernard Faÿ, who over the course of his time in Fribourg transferred his bitterness about the turn of events of his life, and of history, into a new commitment to anti–Vatican II Catholicism.

Among the close friendships Faÿ developed in Fribourg through de Reynold was with the man known as the “rebel archbishop” in Rome, Marcel Lefebvre. Deeply opposed to what he called the “adulterous union of the church with the [French] Revolution,” Lefebvre eventually broke with Rome over the reforms of Vatican II. 48 Activist and archconservative, Lefebvre was aligned not just with traditionalist forces within the church but with right-wing elements outside it. His friendship with Bernard Faÿ was founded on this seamless union of reactionary religious and political worldviews. For Lefebvre, the critique of Vatican II was inseparable from the critique of the French Revolution’s “Masonic and anti-Catholic principles.”49 Faÿ would soon provide the moral support—and initial physical space—for Lefebvre to plan a breakaway seminary espousing his ideas, originally to be based in Fribourg but eventually established at Ecône, Switzerland.50 Lefebvre’s seminary was called the Fraternité Sacredotale de Pie X, named after the resolutely antimodern pope Saint Pius X. The organization continues to be active today and is known as a breeding ground for reactionary political ideas, including Holocaust denial.51

Faÿ was a key player in helping Lefebvre set up the Ecône seminary. In the 1970s, he gave frequent lectures there, most of them centered around forces in history that had sought to topple the church, including humanism, the French Revolution, and the inevitable Freemasonry.52 Meanwhile, ever prodigious in his writing, Faÿ began publishing work that reflected this increasingly dogmatic religious orientation. On the one hand, he continued to produce scorching critiques of modernity, democracy, and liberalism in books such as Naissance d’un monstre: L’opinion publique (1965) and Louis XVI, ou la fin d’un monde (1966). He wrote a hagiographic treatment of Philippe Pétain in 1952, finally published in 2000 under the title Philippe Pétain, portrait d’un paysan avec paysages. But other tracts Faÿ wrote after the war confronted more directly the liberalism of the modern Catholic church. In L’église de Judas? (1970), for example, Faÿ attempts to trace the insidious lines of influence between the contemporary church and Marxism, Freemasonry, and science. All had contributed to the process of “ruining, everywhere they could, traditional faith.”53 It was not enough that Marxists had “infiltrat[ed] the seminaries” during the Popular Front or that certain Jesuits had attempted to “make a bridge between theories of evolution and the Catholic faith.”54 More dangerous still was the way in which modernity itself had led people to “want to bend their God to their tastes, and take their habits as more important than the dogmas of their faith.”55 Turning inevitably to politics, Faÿ even suggests in this book that in the long run Hitler was less destructive to France than Otto Abetz. If Hitler—“incapable of commanding his victory”—had caused havoc in France, he nevertheless had waged an “indifferent war against the church.” Abetz, on the other hand, had encouraged the forces of anticlericalism, socialism, and republicanism to flourish during the occupation and thus had a more lasting and detrimental effect on the Catholic church in particular and France in general.56

Vilifying science, progress, liberalism, democracy, “laicité,” and above all modernity, L’église de Judas is Faÿ’s darkest screed, a cry of outrage from a man no longer able to contain his loathing for a world that, by 1970, seemed utterly foreign to him. When he died eight years later, on December 31, 1978, Faÿ was described by Le Monde as a “‘Man of the ancien régime’ as one doesn’t find them anymore—and as one didn’t during the high point of the regime.” He remained always “faithful to himself almost to the point of rigidity.”57 In an era that had weathered the 1960s and remained gripped by the specter of nuclear war, Bernard Faÿ in the 1970s had become somewhat of a caricature, existing in a fantasy land of monarchs, nobles, and popes. The urbane Collège de France professor, the lover of all things American, the connoisseur of experimental modernist literature—all these real-life roles seemed to have vanished. So too had a reputation that before the war extended across the Atlantic and that had made him, for a time, the “‘unofficial ambassador’ of France to the New World.”58 At his death the New York Times, a newspaper that had mentioned Faÿ by name over 150 times between 1923 and 1944, did not even publish an obituary. Bernard Faÿ had been largely erased from history.

But some remembered. Archbishop Lefebvre, who had heard Faÿ deliver a lecture at Ecône only two months before his death, gave a powerful eulogy at his funeral mass in the archtraditionalist Church of Saint Nicolas de Chardonnet in Paris. He spoke there of Faÿ’s “courageous battles and sufferings which he endured for his Faith.”59 And the postwar journal of Action Française, Aspects de la France—still churning out Maurrassian propaganda in 1979—eulogized Faÿ in the terms that would have mattered to him: “Faithful to himself, to his King, to his God.”60

Religion would increasingly take center stage in Faÿ’s postwar years. But religion would also prove to be a source of disappointment and frustration for the elderly Faÿ. When he was finally pardoned by French President René Coty in January 1959, an act that restored to him his civil rights and pension and allowed him to travel freely in France, the celebration was short lived. Within months, Faÿ would find himself at the center of a new controversy concerning his Vichy past.

On the eve of the 1960s, Switzerland was just beginning to assess its own actions during the recent world war. In a controversy that pitted Swiss youth against their elders and Catholics against Freemasons, Faÿ became the point man for this debate. His profile raised by having been asked, for the first time, to teach a course on the fraught subject of “French culture and civilization” at the University of Fribourg in 1959, Faÿ soon found himself on the hot seat. Student groups, catching wind of the rumor that they were about to be taught about France by an ex-Vichy official, notified the media of their unease. Immediately articles in the National Zeitung of Basel, a liberal German-language newspaper, and in the French-Swiss newspaper La Gruyère questioned why a man accused of “anti-Semitic and anti-Masonic activities” by the French government had been “given the contract to make Fribourg students familiar with French civilization.”61 Faÿ’s defenders quickly mobilized, announcing publicly that La Gruyère was the organ of disgruntled Freemasons and rehearsing the familiar line that Faÿ’s Vichy activities had been directed toward saving the Masonic archives rather than destroying them. Moreover, by this date Faÿ had already been pardoned by the French government and was no longer a fugitive. Nevertheless, the damage was done, less in alienating Faÿ from Swiss Freemasons than in sticking him with the public charge that he was an anti-Semite. This charge had been rather marginal in Faÿ’s 1946 trial for collaboration, but by 1959, it was fatal. Within months the image of Faÿ as a Vichy-era persecutor of Jews working freely in Switzerland would become the latest scandale in a country that was just coming to terms with its postwar past as a “brown refuge.”

While Faÿ conferred with a lawyer, the Affaire Faÿ exploded. Almost a year after the first newspaper attacks, in early 1960, the Jewish Student Union of Switzerland, a group composed of students in Basel and Zurich, with a small satellite group in Fribourg, issued the following statement: “The association of Jewish students in Switzerland … supports the Fribourg Student Association in its position that the professorship of Herr Faÿ is incompatible with the principles of freedom and dignity of man.”62 Newspapers across Switzerland jumped on the story. A Swiss judge was asked by the cantonal government of Fribourg to investigate the charges. He found Faÿ “innocent of anti-Semitism.” Nevertheless, at the end of November 1960, Faÿ—who had remained largely silent about the affair—asked the University of Fribourg to discharge him from his duties. Perhaps fearing further disclosures, Faÿ chose to close the door on his past and retreat. The tides of history and society had definitively turned against him. One Fribourg acquaintance who saw him after his resignation recalls that Faÿ had an air of negativity and sadness about him and rarely smiled.63 Teaching occasional courses for foreign-study students in Fribourg, traveling back and forth from Switzerland to Luceau to his brother Jacques’ home in Paris, Bernard Faÿ spent the last two decades of his life writing, ruminating, and dreaming of a Catholic life unmarred by the catastrophe of modernity.

FIGURE 6.4 Bernard Faÿ in Fribourg, Switzerland (1960s).

SOURCE: COPYRIGHT ALEX ERIK PFINGSTTAG.

But Faÿ did publish one short response to his Swiss critics. In a letter to the Geneva newspaper La Suisse, in June 1960, Faÿ disputed the “tendentious and false” claims against him, announcing that he had “always been opposed to Nazism and detested its agents.” In fact, Faÿ writes, he had “protected or saved” Jews throughout the war, including “Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas during the entire Occupation.”64 Ironically enough, this official line—first uttered by Faÿ and repeated uncritically by every single one of Stein’s subsequent biographers—would remain the most memorable utterance Faÿ ever made. It would be the one assertion that would keep Faÿ’s name in print as Stein’s star continued to rise in the last two decades of the twentieth century and as biographers began to assess her life. The complexities of Stein’s own actions during the Vichy years and the shifting influence of Faÿ over his fractious Vichy colleagues would be turned into a potted narrative. Bernard Faÿ was now a “Vichy official” with a soft spot for an old friend; Stein and Toklas simply “persecuted Jews.”

Inevitably, the charge of anti-Semitism against the elderly Faÿ has also become, for recent critics, the single most important mystery surrounding his relationship with Gertrude Stein. However much Stein, who shared some of Faÿ’s attraction to Catholicism, may have felt conflicted about the issue of Jewishness during her lifetime, and however much their relationship may have been founded on a variety of other interests, passions, and political and aesthetic affiliations, recent critics have fixated their attention upon the unlikelihood of a friendship between “the anti-Semite” and “the Jew.”65 Allowing their story to remain on this reductive but moralistic terrain distracts us from the reality of their actions and convictions. It also keeps us from grasping the real dilemmas of their time—most importantly, the seemingly improbable attraction of modernist writers and thinkers to right-wing or reactionary politics.

It was Stein’s greatest defender, the Jewish-born Alice Toklas, who would, at the end of her own life, bring Stein and Faÿ back together again. In 1957, with the help of Faÿ and his friend Denise Azam—herself a Jewish-born Catholic convert—Toklas was initiated into the Catholic church. Her conversion was made “most of all,” according to her biographer Linda Simon, “for the conception of a populated heaven where she would find Gertrude.”66 Rejecting the Jewish background that she had never really acknowledged, Toklas made Catholicism into an expedient means toward an end. For the next decade of her life, until her death on March 7, 1967, Toklas continued to look forward to this final and ultimate reunion with Stein. And to the end of her life she praised Faÿ for giving her faith and for making this dream seem possible.67 “You were her dearest friend during her life and now you have given her that eternal life,” she wrote to him in a poignant letter.68

For his part, Bernard Faÿ remained skeptical. He had converted Toklas and Denise Azam, but Gertrude was somewhere in limbo, the place of unbaptized souls. As he said to a family member, the greatest regret of his life with Stein was in fact his inability to convert her to Christianity: “Avec Gertrude, j’ai raté” (“With Gertrude, I failed”).69 Faÿ had ultimately failed to bring Stein around to his worldview, and because of this neither he nor Toklas would ever meet her again. The death of Stein was a loss of both his power and his love. Never fully able to separate one from the other, Faÿ could only regret, as he would do so often in his life, being misaligned with a fallen world.