A GATHERING OF FORCES

Set-backs at Dunkirk

While it is true to say that the British Chiefs of Staff never had far from their minds the connection between the rescue of the British Army from Dunkirk and defence against the expected invasion, it is probably equally right to remember that similar considerations also influenced the Germans. Every man and weapon which could be saved from Dunkirk for the defence of Britain would make the German invasion task harder. Every ship and every aircraft destroyed in the attempt to bring the troops home damaged the nation’s shield. Kesselring would have been content to prolong the battle for Dunkirk if the balance of losses came down in his favour. Unfortunately for him, however, the Luftwaffe was ill-prepared to apply a stranglehold. In four weeks of heavy combat, as much from unserviceability as from battle casualties, its operational strength had fallen. Some bomber units were 50 per cent below establishment, although the fighter units had maintained a rate of 75 per cent or more, and the single-engined Messerschmitt Me 109 had proved superior to anything it had met so far. Deployment was at fault, too; a great many formations were still operating from bases in Germany because to bring them forward all at once, was beyond the capability even of the excellent field organization then in existence. So the attacks on Dunkirk, which began in earnest on 28 May, never attained the Luftwaffe’s maximum effort. Moreover, it was hampered on occasion by poor weather and, to an alarming extent, by the intervention of British Spitfire fighters, based on airfields in England.1 Suddenly, the Messerschmitt pilots found themselves opposed by an aircraft fought by men who were their equal; the German fighters frequently failed to rendezvous with the bombers they were supposed to escort, and the bombers received heavy punishment.

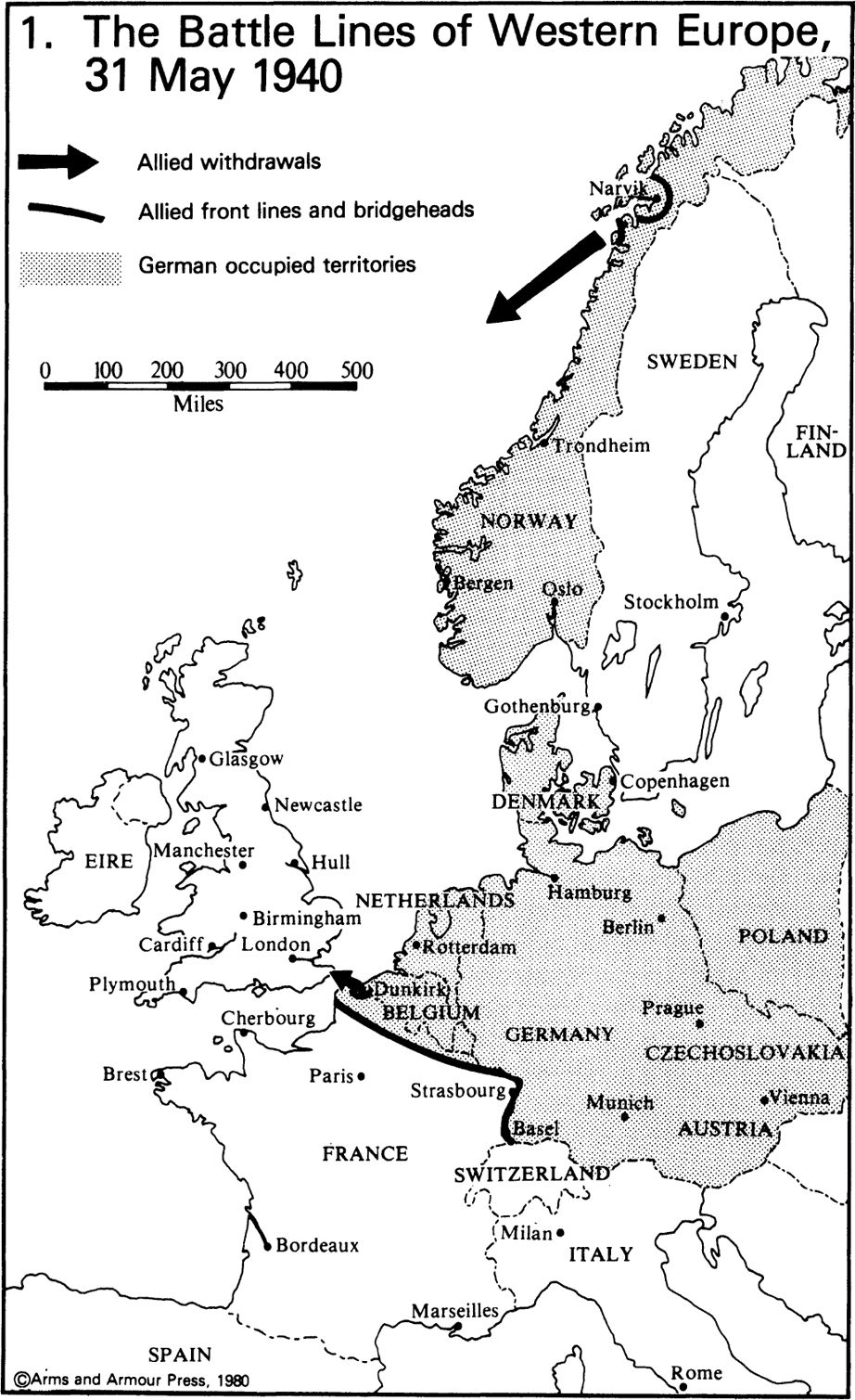

The story of the evacuation of the British and French armies from Dunkirk has been recounted in detail in the British Official History France and Flanders by L. F. Ellis. In summary, the Luftwaffe failed to prevent the evacuation by sea, and when, too late, the Army was ordered to seize the port it was unable to do so before 330,000 men had been snatched to safety from under their noses. Nevertheless, on 4 June, when all resistance had come to an end and the last British ship had disappeared over the horizon, the Germans could take possession of vast quantities of abandoned arms, ammunition and equipment. The British Army, alone, left behind 2,472 guns, about 400 tanks, 63,879 vehicles and all its stores – which represented a major portion of the best materiel it had possessed. Simultaneously, the RAF had lost 100 more aircraft (mostly fighters) and 85 fighter pilots, and the Royal Navy 243 ships, six of which were destroyers (invaluable for anti-invasion operations in narrow waters) together with many more ships damaged, including 19 destroyers. Therefore, although Goering and Kesselring had failed to prevent the evacuation from Dunkirk, and at a stiff price, they had succeeded in wearing down the defenders of the British Isles. Furthermore, ample opportunities to inflict additional losses, when the enemy fought on in Norway and in France, were yet to be presented. Before Dunkirk had fallen, the Wehrmacht in the West had reorganized into three groups – two designated for the conquest of France and the third for Operation ‘Lion’. Only eight infantry divisions and one panzer division were, at this stage, put under the command of General der Infanterie Ernst Busch’s 16th Army. The Luftwaffe, however, tended to retain a larger proportion of its resources for ‘Lion’ than did the Army. To Kesselring’s Luftflotte 2 was allocated a strong force of bombers and fighters plus the paratroop and air landing divisions and the bulk of the transport aircraft allocated to their service. General der Flieger Hugo Sperrle received what was left over for his Luftflotte 3, except when circumstances demanded a maximum effort in support of some special operation. On 5 June, as Luftflotte 2 made its preliminary flights in preparation for ‘Lion’, the Germans, with supreme confidence, moved to overwhelm France with forces deficient of maximum air support. German losses had been relatively light, and the pause at Dunkirk had enabled the Army to rest its mobile troops (the ten panzer divisions and seven motorized infantry divisions) and restore their equipment to a higher state of maintenance. An inspection of the battlefields of May had satisfied the Intelligence Branch that 85 per cent of the best French mechanized divisions, 24 of their infantry divisions and the bulk of their air force had been eliminated. The latest information gained through radio intercept had pinpointed nearly all the surviving Allied formations, and painted a picture of a seriously weakened enemy in a state of disarray. British reinforcements were known to have arrived to the south of the River Somme, even while the lines of circumvallation were closing upon Dunkirk, but these consisted of a single understrength armoured division (the 1st) and the 51st and 52nd Infantry Divisions, plus parts of the 1st Canadian Infantry Division. Their presence was to be welcomed, it was concluded! If these good formations could be mopped-up in France they would not be encountered in England.

The slightest mention of the prowess of British forces fascinated the planners of ‘Lion’. They were impressed by British tenacity, and insisted to Jodi at OKW that during the forthcoming assault on France, priority be given to the destruction of the British forces and the early capture of that sector of the French seaboard which would become the mounting base for the invasion. Von Stülpnagel was both intrigued and pleased by reports of a battle which had taken place near Abbeville from 27 to 30 May, when tanks of the French 4th Armoured Division and the British 1st Armoured Division had attacked a German bridgehead which had been established south of the Somme. At first, the Allied tanks, some of them very heavily armoured, had forced the German outposts to retire, and panic had infected the infantry. But, as had been noticed so often earlier in the campaign, the enemy did not press home his attack or properly co-ordinate his infantry, tanks and artillery. The German anti-tank gunners had stood their ground and repelled the attack, although not without loss to themselves. But, after the enemy had withdrawn, they dispersed their tanks, thus exposing the remaining enemy defenders to the sort of concentrated attack on a narrow frontage which the Germans practised. Von Stülpnagel decided to insist on including the maximum number of tanks and anti-tank guns among the assault formations for Operation ‘Lion’. If this could be achieved, the chances of a British counter-attack succeeding immediately after the Germans had landed would be remote: furthermore, a rapid riposte leading to a breakout would be simplified and accelerated.

The plans take shape

Planning for ‘Lion’ progressed well under the goading of the Luftwaffe and Army enthusiasts and was held back only occasionally by Kriegsmarine scepticism. Von Waldau and von Stülpnagel competed in ingenuity to overcome difficulties and, as was the way with élite General Staff officers, instigated a series of technical investigations into ways of overcoming the problems of transportation. Because of the Kriegsmarine’s alleged inertia, both the Army and the Luftwaffe began to explore methods of their own to ship troops and equipment across the Channel. Meanwhile the Kriegsmarine simply selected the types of ship and inland waterway barge (Schiffs or Prahms as they came to be known) deemed most suitable for the tasks envisaged. Each of the three Services thus assembled its own invasion fleet (with an inevitable waste of effort and the construction of an incredible miscellany of craft), while the Luftwaffe was allowed to concentrate on the air lift, hindered only in the slightest by the other two Services, because Goering, who enjoyed the full confidence of Hitler, made a point of dealing direct with the Führer and by-passing OKW, OKH (the Army High Command) and OKM (the Navy High Command) when it suited him.

Jodi’s plan gave tacit precedence to the Luftwaffe, though airmen were sparsely represented within OKW by comparison with the Army and Kriegsmarine. Indeed, in the final event, OKW could only formalize what was agreed by the joint services planning committee in which von Waldau held a pre-eminent position.

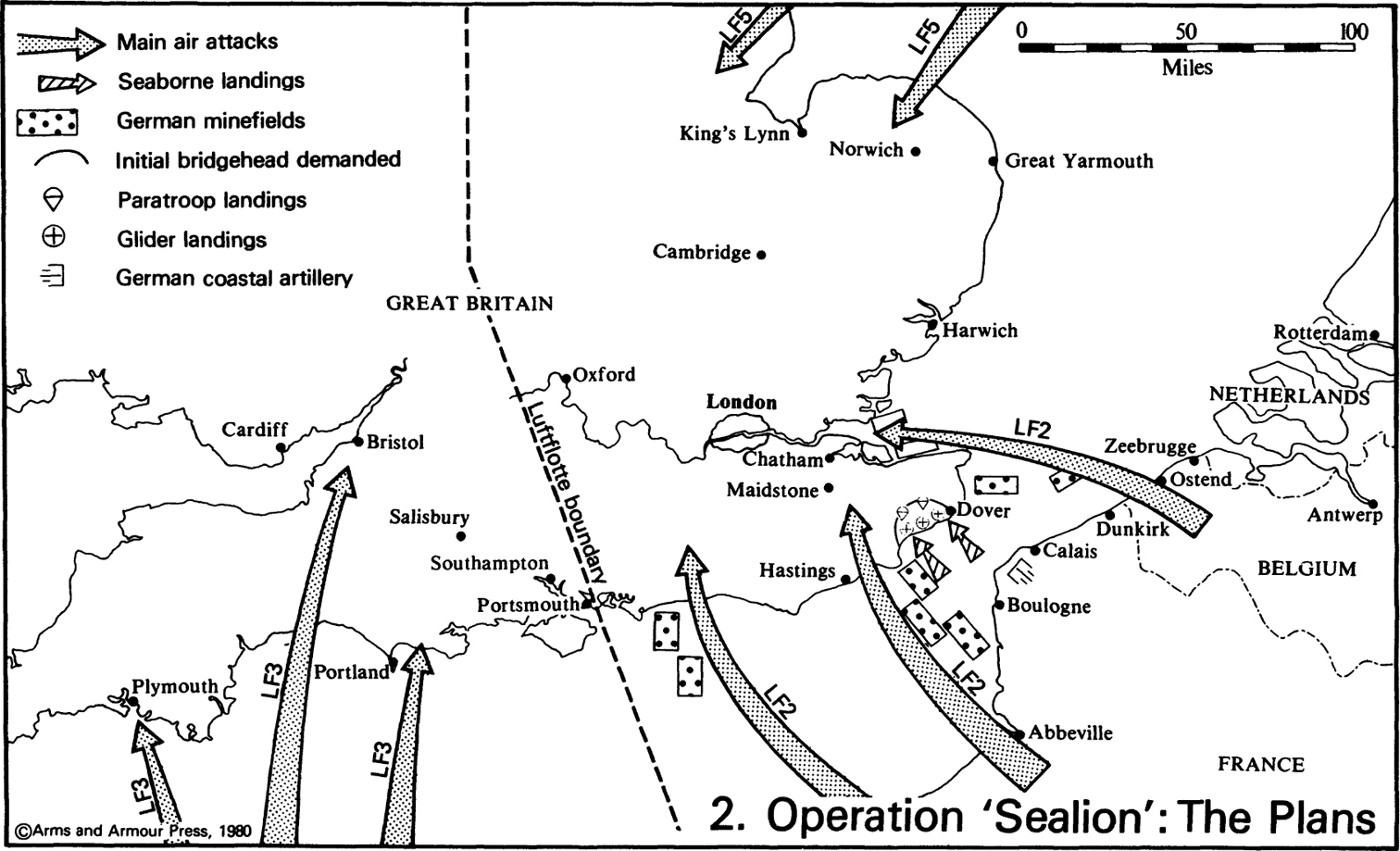

It was instinctive among the Army’s leaders that they desired to launch the invasion on as wide a front as possible, thus providing themselves with the maximum number of options from which to develop alternative directions of thrust. But the primary acceptance by Hitler of Goering’s basic requirement for early commencement of the invasion, and the inability of the Kriegsmarine immediately to procure enough shipping for an early broad-fronted strategy, denied them this luxury. They were compelled by Hitler to adopt a narrow-fronted assault in the hope that the surprise and sheer violence of this single descent upon the enemy would establish an instant and invincible local supremacy. Von Waldau went so far as to guarantee the success of the initial airborne landing, if it took place at the shortest possible distance from France and, therefore, well within fighter aircraft cover. In other words, he left OKW no option but to make the attempt somewhere between Hythe and Deal, where the lines of communication were shortest, air protection would be strongest and the turn round of cargo vessels and aircraft quickest. It was almost incidental that the enemy would understood this too, but so sure were the Germans of their superiority that they relied upon gaining a victory by prowess alone.

In any other circumstances a prolonged argument against the narrow front might have been mounted jointly by the Army and Kriegsmarine, but long-standing friendship between General Franz Halder, the Army Chief of Staff, and Admiral Otto Schniewind, the Chief of Staff of Naval Operations, obviated this. Halder had taken a day off, on 25 May, to visit Schniewind in Berlin to discusss the feasibility of Hitler’s latest venture. Halder doubted if the British would readily sue for peace and felt sure they would eventually have to be brought to battle in their own land. He came away from the meeting satisfied that, by the beginning of July, the Kriegsmarine could assemble ‘A large number [1,000] of small steamers’ enough to carry 100,000 men at one time. In fact, far fewer ships were immediately available and the maximum number of men the Navy could undertake to carry in one lift in mid June would be 7,500. But Halder’s outline notes for a landing visualised the waters out to mid Channel being dominated by German artillery, ships and aircraft, while ‘Artillery cover for the second half of the run across the water and on the beaches must be furnished by the Luftwaffe. Underwater threats [from submarines] can be shut out by net barrages. Surface threats can be minimized by mines and submarines, supplementing land-based artillery and aircraft. Cliffs at Dover, Dungeness, Beachy Head [but] rest of coast suitable for landing …’ He went on to mention the uses to which the normal, large canal barges, towed by tugs, might be put and ‘Dr Feder type concrete barges now under test. Provision in sufficient numbers in July held possible’. Schniewind, for his part, stressed the need of fine weather and smooth water (both of which, indeed, were likely in July) and, of course, the unrestricted use of ports between the River Scheldt and River Seine.2

The Halder-Schniewind meeting not only settled an operational pattern and, to some extent, the immediate planning needs of all three Services, but also gave strong impetus to those engaged in preparing the invasion. Halder had felt certain that Hitler would make the fateful decision on the 24th and that, from then on, he would want ‘everything done at top speed’. With this in mind, he had briefed von Brauchitsch, and by so doing had generated in the C-in-C that sense of practicability he displayed to Hitler. Pressure on the planners was now increased by Kesselring through von Waldau. Once the former had settled the plan for attacking Dunkirk, he left its implementation to his Chief of Staff, Wilhelm Speidel, and turned to study the problem of mounting the preliminary operations for ‘Lion’ so as to dovetail them with the inevitable demands which could be expected to support the renewed offensive which was due to commence against France on 5 June.

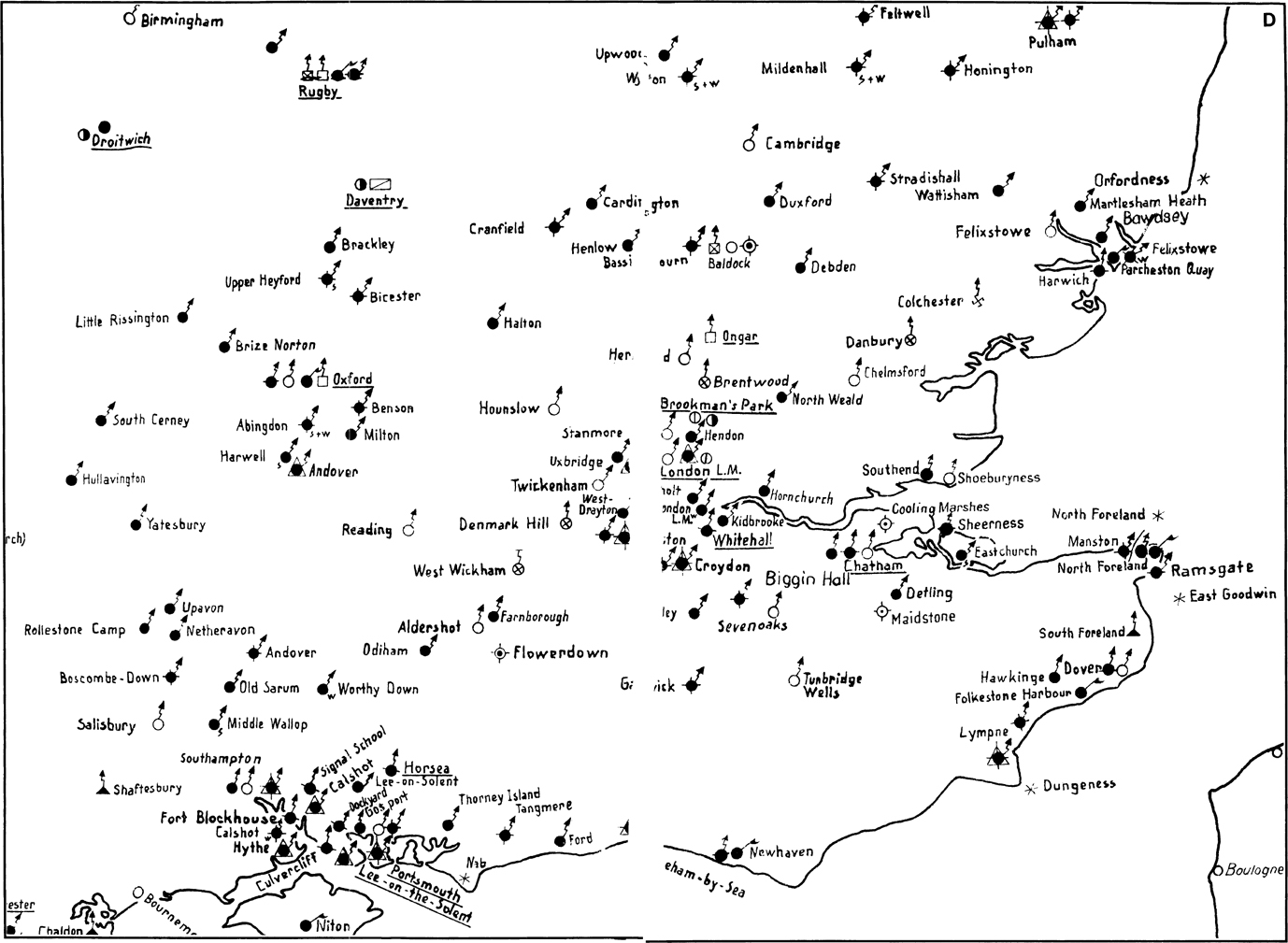

The Luftwaffe was designed principally as a tactical air force for the support of land forces. It included a few units with experience of attacking ships, but none capable of delivering torpedoes – a technique with which the Kriegsmarine had experimented and achieved barely 50 per cent success. It also possessed a limited capacity to deliver strategic attacks on factories and towns, but was dependent upon daytime attacks for accuracy because the beam navigational guidance system had not yet been fully developed for night use. By day, however, the bomber formations were incapable of adequate self-defence against enemy fighters; they depended therefore upon fighter escorts and their safe radius of action was limited to that of the fighters, little more than 150 miles. In the four weeks which Kesselring knew would elapse before he was invited to begin the subjugation of the RAF and provide the direct support of the invasion, he had to establish his Luftflotte 2 on new airfields (not all of them yet in German hands) within striking distance of England; build up their logistic backing; ascertain the enemy’s strength, dispositions and tactical methods; acclimatize his formations and commanders to an entirely new type of operation; and produce a foolproof plan. It was a tall order, but one suited to his talents, frenetic drive and natural optimism.

On the assumption that the strength of the combat formations made available to his Luftflotte 2 on 5 June would be:

200 Long-range bombers (He 111 and Do 17)

50 Twin-engined fighters (Me 110)

20 Long-range reconnaissance aircraft (including some four-engined Focke-Wulf Condors)

and that, in the month to come, this would expand to: —

700 Long-range bombers (including the latest Ju 88)

280 Dive bombers (Ju 87)

550 Single-engined fighters (Me 109)

100 Twin-engined fighters

30 Long-range reconnaissance aircraft,

Kesselring embarked upon a programme geared to a steady intensification of operations both by day and night, aimed at selected targets in and around the coasts of Britain. It was his intention to draw the RAF into battle, sound out the British defences, cause the maximum damage to British ports and shipping, and acclimatize his own men by stages in preparation for the maximum effort scheduled for 9 July. At the same time, Sperrle, whose Luftflotte 3 was already engaged in the preliminaries of the final assault upon France, would begin to make ready to operate on Kesselring’s left flank as soon as he had completed his present task. On 1 and 2 June, the Luftwaffe launched attacks against communications centres in central France and on the 3rd, bombed the outskirts of Paris. The next day its attacks were switched to airfields as the opening moves of the Battle of France rose to a crescendo – its course to be described in Chapter III. During the night of the 5th, the first tentative flights were made by a few of Kesselring’s bombers at a relatively low level over England, causing the air raid sirens to wail in towns and villages and bringing a large proportion of the populace face to face with the throb of foreign engines and the realities of the enemy being actually on their doorstep; learning to live with the Blitz, as they called it. Some bombs were dropped and anti-aircraft guns opened fire, but neither side cared to disclose its full strength or potential, and the Germans were chiefly intent upon practising picked crews in the job of navigating by radio beams transmitted from master stations in Germany. This, the preliminary phase of ‘Lion’, will be described in Chapter IV.

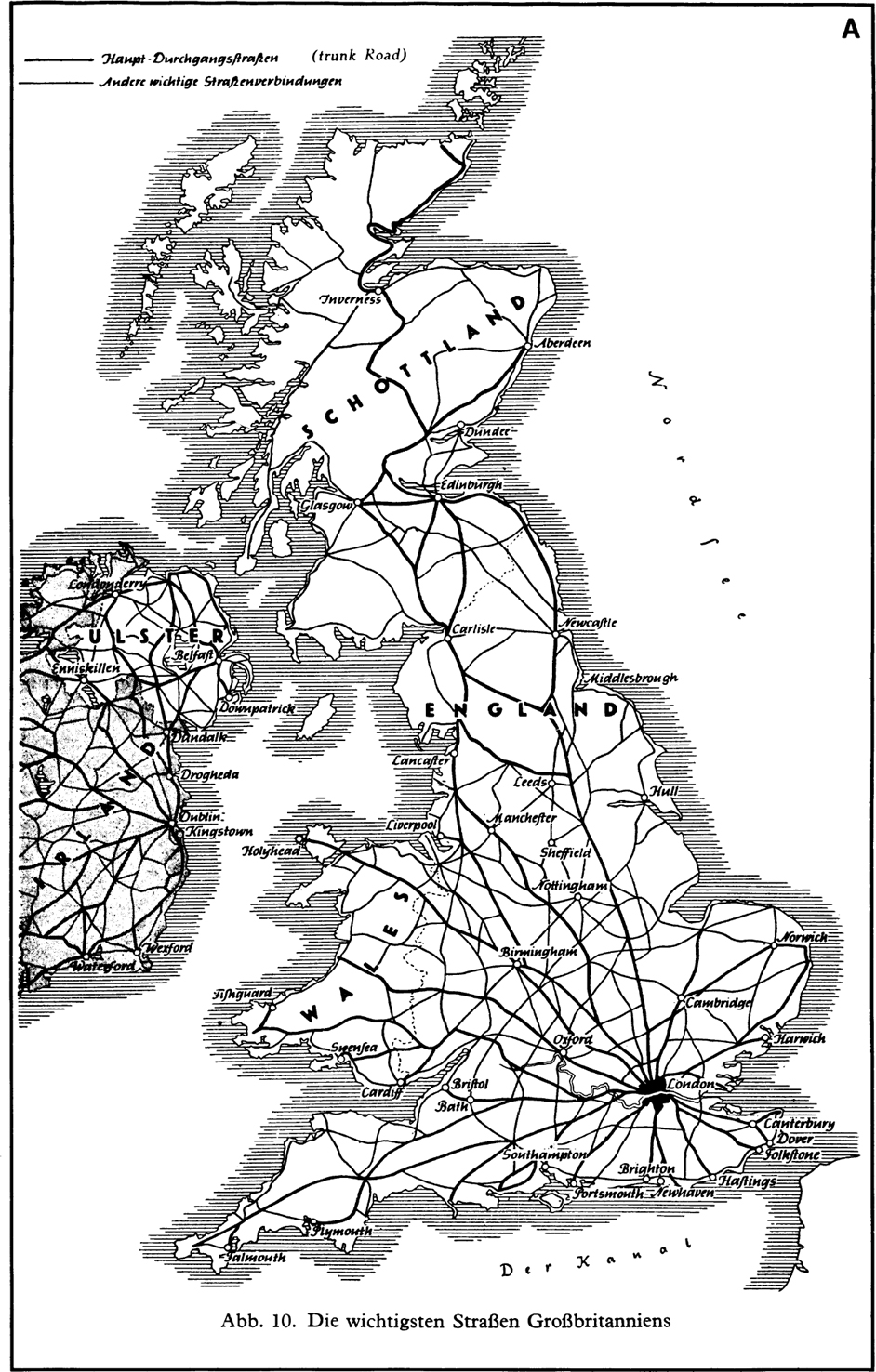

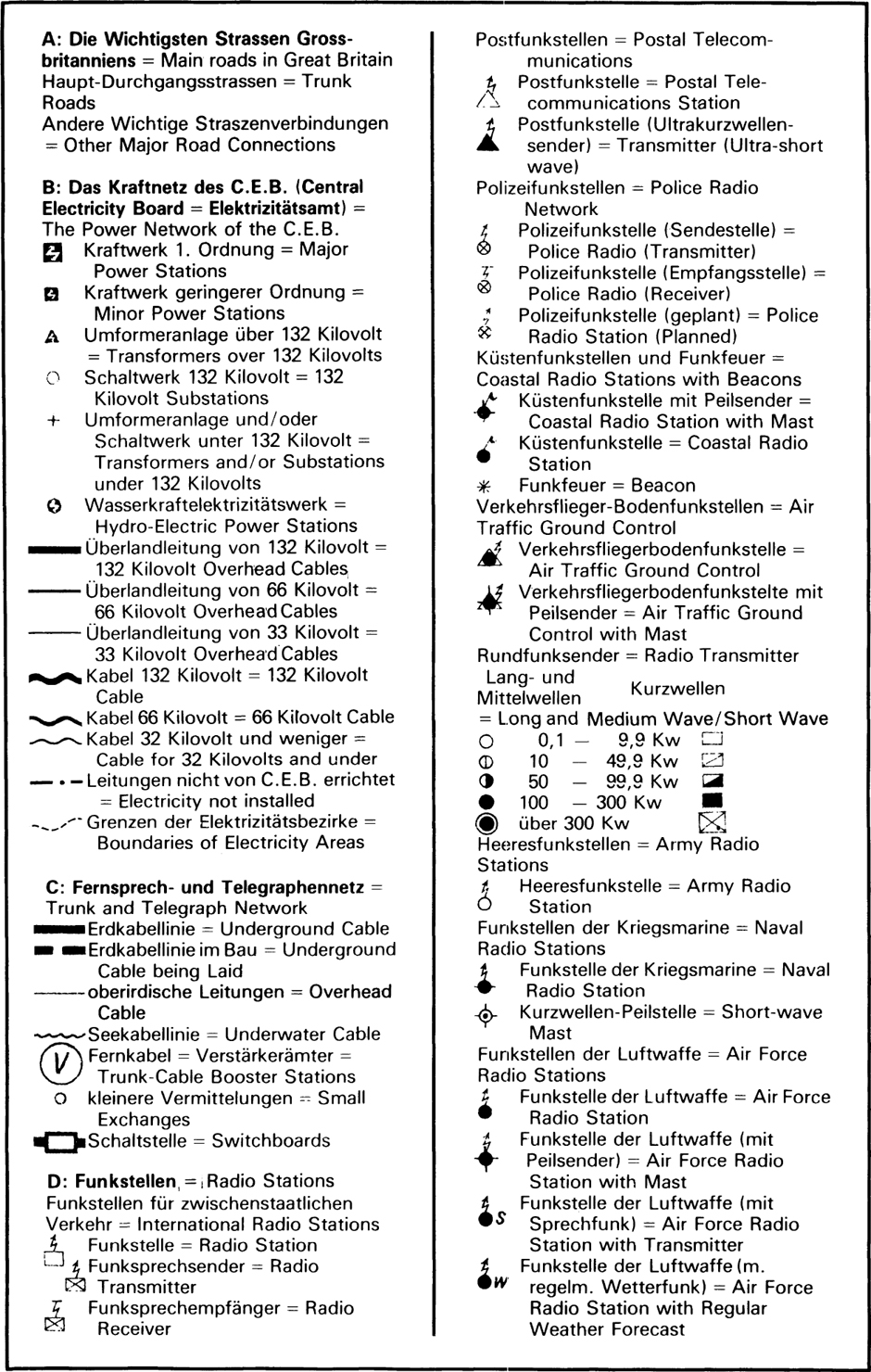

Maps prepared by the Germans for their conquest of Britain. With Translations and keys.

The Kriegsmarine

Totting-up the resources which might be available to them in mid July, the Kriegsmarine concluded on 1 June that, providing they were spared additional losses in the vicinity of Norway, they might, by extraordinary exertions, assemble in the approaches to the English Channel a fleet consisting of:

2 Battle cruisers (Scharnhorst and Gneisenau)

2 Obsolete First World War battleships (Schlesien and Schleswig-Holstein)

1 Pocket battleship (Admiral Scheer)

1 Heavy cruiser (Hipper)

3 Cruisers (Köln, Emden and Nürnberg)

10 Destroyers and torpedo-boats

34 Escorts

30 U-boats

20 Motor torpedo-boats (S boats, usually called E boats by the British).

There were also many minesweepers, armed trawlers, and launches available. It was not, of course, a Fleet fit to engage in a general action with the Royal Navy but, aided by the Luftwaffe and supported by coastal artillery in narrow waters, it might just see ‘Lion’ through.

As has already been mentioned, there were no specially designed assault landing craft in existence, so the land forces would have to be carried in an improvised fleet consisting of small ships, converted barges (Prahms), naval vessels and fishing boats. In addition, there were the Siebel ferries developed by the Luftwaffe, driven in some instances by aircraft propellers powered by aircraft engines mounted above the superstructure and carrying 88mm antiaircraft guns to give accurate fire support during the assault. Raeder gloomily foresaw that the removal of so many civilian craft from their commercial work would lead to a 30 per cent reduction in Germany’s important inland shipping traffic, as well as a serious curtailment of fishing. But the work of selecting, hiring and commandeering suitable craft went ahead regardless of the objections. At the same time, repairs began of the ports upon which the invasion would depend for embarkation and the dispatch of supplies. Rotterdam, Ostend, Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne – none of them in full working order, but not one of them totally unusable – were to be used. Stocks of mines and anti-submarine nets were hauled forward and local defensive barriers were laid. Behind the ports, the chosen Army assault units began to assemble. Everywhere anti-aircraft batteries stood by to protect the ports and vital points.

On 31 May, the planners encountered a tactical difficulty. Whereas the Army insisted that the troops be delivered in an orderly manner to the hostile shore, in combat groups sailing in compact echelons so that they were properly balanced for battle on arrival, the Kriegsmarine could offer no such service. The sailors pointed out that it was asking too much of the captains of ships of unequal performance to keep to a rigid formation and schedule in tidal streams among a maze of sandbanks, wrecks and minefields such as littered the narrow Straits of Dover. They hoped to maintain a steady flow of ships spread over a period of several days, but the Army units might well become disordered prior to landing. The Kriegsmarine would do its best to meet the Army demands, but the Army must plan on the basis of chaos. For five days there was an impasse which was broken when the matter was taken to Hitler who, on 5 June, ruled that the two Services must compromise. He ordered the Kriegsmarine to do all in its power to satisfy the Army’s essential demands and he warned the Army to expect unusually severe battlefield frictions. The soldiers should bear in mind, Hitler insisted, that they would not be the first ashore. The airborne troops would have landed already, and the enemy would be distracted. Moreover, the well-tried German system of organization and tactical flexibility, making use of ad hoc battle groups, should help to overcome any accidental intermingling of troops on the beach. It would look like ‘Formation Pigpile’ (Sauhaufen), admitted Kommodore Friedrich Ruge, who was in command of the minesweeper and escort forces – but it should work.3

The land forces

In Germany, the airborne formations upon which so much depended, had been rested after their exertions in Norway and Holland. Moreover, their potential had been improved so that all three regiments of 7th Air (Parachute) Division were capable of landing efficiently (only two had been ready for Holland). Now they trained hard with the units of Fliegerkorps Zbv, which had been brought up to strength in machines to replace those lost or damaged in the earlier campaigns. By invasion day there would be at least 500 Ju 52 and several four-engined Ju 90 ready, though not all serviceable at once. Alongside the 7th Air Division and the 22nd Air Landing (non-parachute) Division were certain other units which would go into battle by air. Special Unit 800, which came under the wing of the Abwehr (German Military Intelligence) had men able to land by parachute and carry out seaborne raiding; they had been used with indifferent results on 10 May. So too had the men of Infanterie Regiment Grossdeutschland, several hundred of whose members were trained to ride in the remarkable Feisler Storch monoplane which could deliver five assault troopers at a time on landing strips only a few yards in length.

The formations selected for the initial seaborne assault were the 17th Infantry Division and the 6th Mountain Division, the former to go ashore across open beaches to the west of Folkestone, the latter to climb the cliffs between Folkestone and Dover. The mountaineers would have to depend almost entirely on their own skill to reach their objectives, but the men of the 17th would have the assistance of Armour. Already the technique of making the standard Pz Kpfw III and IV tanks wade ashore totally submerged had been mastered. Now the crews of Detachment B of the Panzerwaffe were finding out how to do this on a sloping beach. They would be in possession of 32 fully adapted Pz Kpfw III – a machine which could wade to a depth of 8 metres after entering the water down an extended ramp from a Prahm.

Engineer detachments, already well-practised in the launching and navigation of rubber assault boats in the gentler currents of rivers and canals, began to learn how to do it in a tidal stream and through surf. Throughout June and early July, the beaches of the Baltic and of the North Sea and Channel coasts were the scenes of intensive activity as the soldiers and sailors got to know each other’s problems and tried to overcome each difficulty as it arose. With the basic skills barely mastered, the skippers of the landing craft selected for the leading assault echelons, began to combine as formations in rehearsals and tactical exercises which showed only too clearly how formidable the problems would be on S Day when it came. Grimly, however, they stuck to the task, working round the clock to eliminate as many of the problems as they could, praying, in some cases, that they might be spared the ordeal. They would never be completely proficient, but the needs of the hour wonderfully concentrated their determination and ingenuity.

Meanwhile, on the headlands overlooking the Channel, and in sites within range of Dover, German artillery began to settle in. For protection of the shore line and the seaward approaches out to about 11,000 yards, stood batteries of 10.5cm Field Howitzers (FH 18). Emplaced a little farther back and tasked to deal with targets out to 11,000 yards were the 15cm Medium Howitzers (FH 18) and nearby, reaching out to about 15,000 yards, 15cm K 18 medium guns and 21cm Mrs 18 howitzers whose task was to protect the invasion fleet in the earlier stage of its journey. Superimposed over this standard layout of German field artillery were to be 29 very long-range pieces (some of them on railway mountings) of 17cm—38cm calibre, whose task would be to bombard the environs of Dover, Hythe and Folkestone, and ships sailing close to the English shore. They could produce a heavy and fairly accurate volume of fire whose effect on civilian morale was expected to be severe.

Behind the Channel coast and reaching back into Germany, the lines of communication were being rapidly improved. Canals that had been blocked during the recent fighting were being cleared to permit the passage of invasion craft to the embarkation ports. High priority was given to the restoration of the railways and the replacement of the many bridges which had been demolished. After that the stocking of supply bases adjacent to ports and airfields could go on apace – and, indeed, the rate of progress was rapid. Also, the recovery of abandoned enemy stores and equipment from the battlefields not only denied them to prospective partisans but proved beneficial to the German logisticians. Local labour made its contribution as the curfew and close surveillance of civilians was relaxed when it was realized that the conquered people had lost the will to fight. A mere handful were resolved to resist; only the Belgians and the Dutch were thinking up ways to hinder the Germans and, most useful of all to the British, transmit information about German activities. Nothing, however, could prevent the Germans solving their logistic problems. By 5 June they were well prepared for the advance to the south, and it would be a mere few weeks before their major supply requirements for ‘Lion’ were satisfied.

‘Sealion’ is christened

In the knowledge of the resources which would be provided, it was possible for detailed plans to be laid and disseminated by OKW to enable Busch at HQ 16th Army, Kesselring at Luftflotte 2 and Vice-Admiral Lütjens, the Fleet Commander who would coordinate the naval operations, to move 16th Army to England. By 5 June, Hitler had satisfied himself, in so far as he was able, of the feasibility of the Armed Forces’ plans and had instructed Keitel to complete the Directive which would authorize the physical preparations for ‘Lion’. Much already was in train as commanders and staff took such action as they could to make ready. Two days later, the Führer signed Directive No 16 which, incidentally, renamed the operation ‘Sealion’.4 Its stated intention was ‘To eliminate the English homeland as a base for the continuation of the war against Germany and if necessary, to occupy it completely.’ It went on to instruct:

1. The Luftwaffe to achieve air superiority over the enemy air force as the essential prerequisite of establishing a bridgehead by the dropping of airborne troops a short distance inland from the places where the Army would come ashore. Thereafter its task would be to act as artillery in support of the Army and the Kriegsmarine, in addition to its role of preventing interference with the Lines of Communication.

2. The Army to execute a surprise landing on a narrow front of approximately 20 miles between Hythe and Deal, and then, in order of priority:

a. Link up with the airborne forces.

b. Seize control of the ports of Folkestone and Dover.

c. Extend the bridgehead inland to a line from Rye to Faversham, making particular efforts to gain early possession of airfields to enable the Luftwaffe to operate from them as soon as possible.

a. Transport the Army to its landing areas.

b. In co-operation with the Luftwaffe, prevent interference with the Lines of Communication.

c. Open up the ports and transport the follow-up forces to the bridgehead.

Formations taking part were to complete their plans by 7 July, on the understanding that S Day would be 13 July. Logistic support systems would be kept as similar as possible to those normally employed by the Army; the Kriegsmarine participation was that of an extra cog in the machine. It was appreciated, however, that some serious interference with surface routes of supply must occur, either from adverse weather or because of prolonged enemy intervention. The Luftwaffe, therefore, must be prepared to supplement the transport services with air-lifted supplies, the maximum use must be made of captured enemy material and by living off the country, and units must take the minimum of equipment to save space.

The administration of conquered territory, in the first instance, was to come under the jurisdiction of the Army and was to be laid down by OKH. It would be the subject of a special instruction headed ‘Orders concerning the Organization and Function of Military Government in England’ issued on 1 July.

In order to deceive the enemy as to the timing, objectives, nature and scale of ‘Sealion’, an elaborate deception plan was devised. The enemy was to be led to believe in the likelihood of several descents against widely separated parts of the British Isles (including Eire), but give the impression that they would not take place until August. As the rest of the French coast fell into German hands, activities in the westerly ports were to be made to appear as intensive as those in the easterly ones – and, indeed, it was visualized that some supply convoys might well use the ports of Le Havre, Cherbourg and Brest once the initial lodgement had been made near Dover. Reconnaissance of the enemy coast line and inland territory was to be widespread and not aimed solely at the chosen beach head. Rumours and misleading information were to be fed to the British Intelligence through diplomatic channels, the news media and any other communication systems that could be used. At the same time, measures were taken so as to suggest a build-up of forces in the mounting area which bore no relation to actuality and instead falsified the agreed date of departure. Above all, the airborne forces were forbidden to send their members outside Germany in order to prevent their being identified by enemy agents in the occupied territories.

To implement the operational aspects of the plan, a joint headquarters was set up in Brussels, adjacent to the headquarters of Luftflotte 2. There, under the overall supervision (or chairmanship, as some called it) of Kesselring, the staffs of Busch and Lütjens co-ordinated their activities. As the din of battle in Norway died away and the Battle of France rose to its final peak, and as German aircraft embarked upon their first serious incursions over the British hinterland, the commanders and staffs who were to conduct the Battle for Britain grappled with problems which, in their experience, were unique and, to some among them, extremely forbidding.

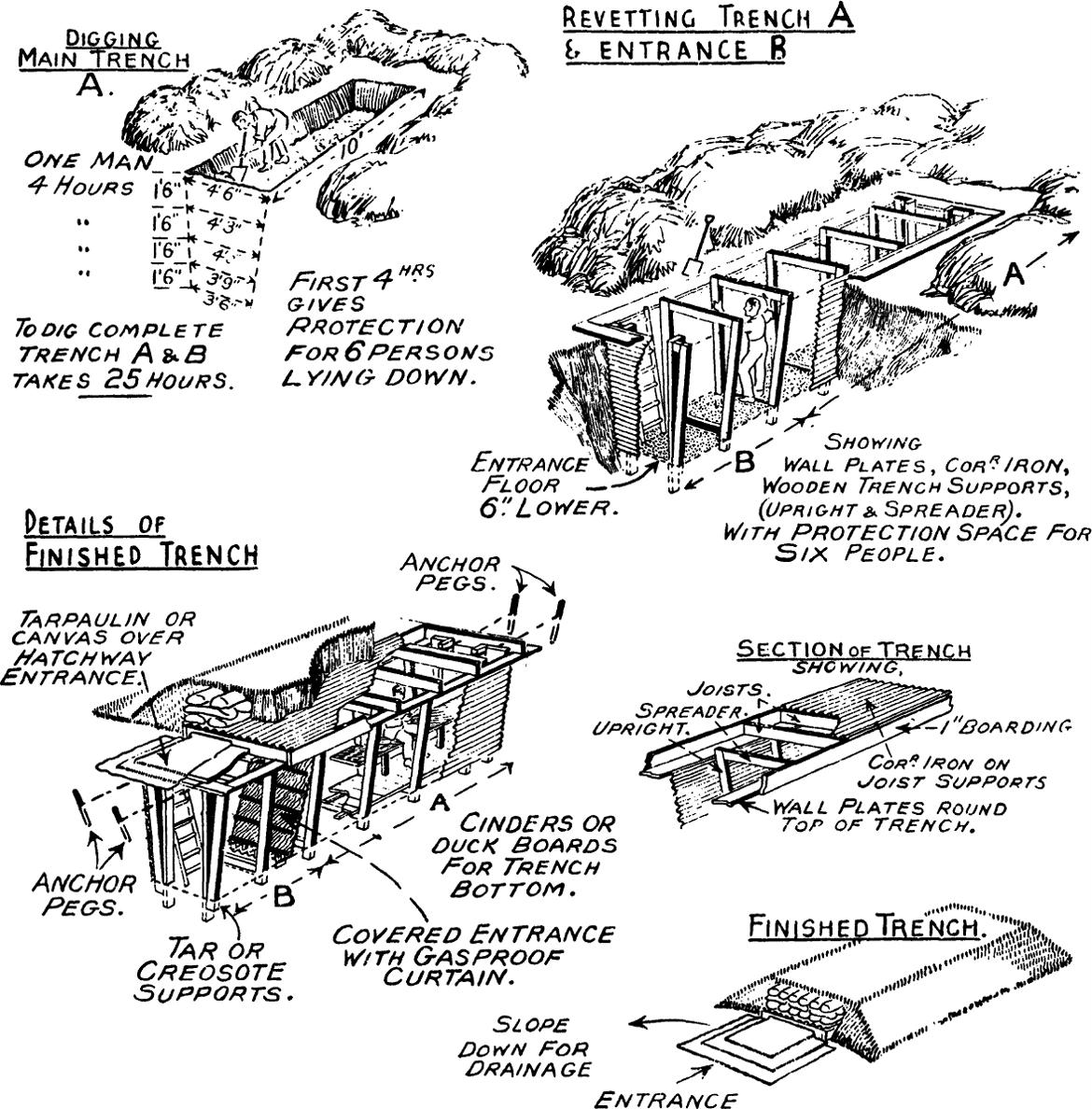

Contemporary instructions to the British public concerning the digging of trenches as protection against German air raids. (Lionel Leventhal Collection)