An Internet search for John Zephaniah HOLWELL (1711–98) produces thousands of references, most of which contain the words “Black Hole.” The back cover of Jan Dalley’s The Black Hole: Money, Myth and Empire explains:

The story of the Black Hole of Calcutta was once drilled into every British schoolchild: how in 1756 the Nawab of Bengal attacked Fort William and locked the survivors in a tiny cell, where over a hundred souls died in insufferable heat. British retribution was swift and merciless, and led to much of India falling completely under colonial domination.1

Dalley’s book tells the story of this foundation myth of the British Empire, a myth that was “based on improbable exaggeration and half-truth” and “helped justify the march of empire for two hundred years” (2007: back cover). The reason Holwell is associated with this myth is that he was its creator. When Holwell’s account of the dreadful night in the Black Hole was printed in 1758, it provoked scandal and horror. Fueled by numerous reprints, the story soon became an event of mythic proportions, a symbol of the fall of Calcutta and the beginning of empire that Dalley lines up with the likes of the Boston Tea Party and the Battle of Wounded Knee (2007:199). According to Hartmann (1946:195) this story was “about as well-known in the English-speaking world as the fact that Napoleon was Emperor of France”; but the fact that this statement occurs in a paper titled “A Case Study in the Perpetuation of Error” points to the raging controversy about the “Question of Holwell’s Veracity,” as J. H. Little put it in the title of his influential 1915 article. Having examined Holwell’s original Black Hole report line by line, Little arrived at the conclusion that the whole episode was a gigantic hoax. Hartmann summarized Little’s observations as follows:

Specifically, Little shows that Holwell (1) fabricated a speech and fathered it on the Nawab Alivardi Khan; (2) brought false charges against the British puppet ruler of Bengal, the Nawab Mir Jafar, accusing him of massacring persons all of whom were later shown to be alive . . . (3) forged a whole book and called it a translation from the ancient sacred writings of the Hindus. (Hartmann 1946:196)

Hartmann defended Holwell against the last accusation by portraying him as a possible victim of fraud rather than a forger:

This last might be defended on Holwell’s behalf if we assume him to have been victimized by some Brahmin or pundit who enjoyed pulling a foreigner’s leg; but certainly the first two cases have a brazen political significance also possessed by the similar story of the Black Hole. (pp. 196–97)

The book that Holwell (according to Little) forged and sold as a translation from the ancient sacred writings of the Hindus was the very Chartah Bhade Shastah that Voltaire from 1769 onward so stridently promoted as monotheism’s oldest testament (see Chapter 1). Is there any evidence that Holwell’s Chartah Bhade Shastah is a brazen forgery? Some modern historians and Indologists have tried to identify the text translated by Holwell, thereby absolving him of the charge of having invented the whole text. For example, A. Leslie Willson thought that Holwell had adapted a genuine Indian text:

John Z. Holwell (1711–1798), a former governor of Bengal and a survivor of the famed Black Hole of Calcutta, gives an account of his favorable impression of the religious and moral precepts of India. Because of his acquaintance with one of the holy books of the Hindus (the Sanskrit Satapatha-brâhmana, called the Chartah Bhade in Holwell’s adaptation), he believed he discerned a great influence of Indic culture upon other lands in ancient times. The more familiar he became with the Sanskrit work, the more clearly he claimed to see that the mythology as well as the cosmogony of the Egyptians, the Greeks, and the Romans was borrowed from the teachings of the Brahmans contained in the Satapatha-brâhmana. Even the extreme rituals of Hindu worship and the classification of Indic gods found their way West, although extremely falsified and truncated. (Willson 1964:24)

Based on the authority of Johannes Grundmann (1900:71), Willson claimed that Holwell’s source, the Śatapatha-Brāhmaṇa, was later lost (p. 24). In The British Discovery of Hinduism in the Eighteenth Century, P. J. Marshall argued that “judging by the words which he reproduces, Holwell must have made his translation out of a Hindustani version” but added that “the original of Holwell’s Shastah cannot be identified” (Marshall 1970:46). Marshall, who took the trouble of annotating Holwell’s Shastah text, thus seems to have regarded it not as a literary hoax or an invention but as a translation of a genuine Indian text, albeit not from Sanskrit but from a Hindustani original. More recent research has questioned earlier opinions but otherwise hardly advanced matters.

In the introduction to the 2000 reprint of Holwell’s text, M. J. Franklin calls the Shastah text “a text which must remain rather dubious as Holwell asserted it covered all doctrine, and no independent record of such a work exists” (Holwell 2000:xiii). Franklin and other recent authors all rely on Thomas Trautmann’s excellent study Aryans and British India, which found that Holwell’s book “contains what purport to be translations from a mysterious ancient Hindu text, Chartah Bhade Shastah (Sanskrit, Catur Veda Śāstra), a work not heard of since” (1997:30). Trautmann characterized Holwell’s “supposed translations of the supposed ancient Shaster” as “obscure and dubious” (p. 33), his Indian sources as “not otherwise known, before or since,” and the details of his account as “confusing” (p. 68). Thus, his valiant attempt to identify Holwell’s Indian sources2 ended with a sigh: “It is all rather murky and more than a little suspicious” (pp. 68–69).

According to his obituary in the Asiatic Annual Register for 1799 (1801:25– 30), John Zephaniah Holwell was born in Dublin on September 17, 1711. At age 12 the intelligent boy won a prize for classical learning but was soon sent by his father as a merchant apprentice to Holland, where he learned Dutch and French. Before he turned eighteen, he became a surgeon’s apprentice in England, and at age twenty he embarked as a surgeon’s mate on a ship sailing to Bengal. As surgeon of a frigate of the East India Company, he soon was on the way to the Persian Gulf and studied Arabic, and on his return to Calcutta he also learned some Portuguese and Hindi. At the young age of twenty-three, he was appointed surgeon-major, and after another trip to the Gulf he could speak Arabic “with tolerable fluency” (p. 27). During his residence in Dacca, he was “indefatigable in improving himself in the Moorish and Hinduee tongues” and began “his researches into the Hindû theology” (p. 27). Back in Calcutta, he quickly rose through the ranks; at age 29 he was appointed assistant surgeon to the hospital, and in 1746 (age 35), he became principal physician and surgeon to the presidency of the Company. In 1747 and 1748, he was successively elected mayor of the corporation. In the winter of 1749/50, he returned for the first time from India to England. It was for health reasons, and while recuperating, he enjoyed the leisure “to arrange his materials on the theology and doctrines of the ancient and modern Brahmans.” Only after his return to India did he become acquainted “with the Chartah Bhade of Bramah,” of which he claims to have translated a considerable part (Holwell 1765:3). During the sack of Calcutta when the Black Hole incident took place, Holwell allegedly lost both the Indian manuscripts of the Chartah Bhade Shastah and his English translation.

After this incident Holwell had to sail back to Europe for the second time, and this time he used his sojourn to publish the famous Black Hole narrative (1758). Upon his return to India, he became governor of Bengal for a few months but was soon replaced. During the last eight months of his long stay in India, he was “freed from the plagues of government” and reassumed his researches into Indian religion “with tolerable success” when “some manuscripts” happened to be “recovered by an unforeseen and extraordinary event” (p. 4), which Holwell never explained. In 1761, at age 50, he returned to England for the third and final time and lived there for almost four leisurely decades until his death in 1798 at the age of 87. Of particular interest among the books published during these decades are the three volumes of Interesting historical events, relative to the provinces of Bengal, and the empire of Indostan (1765, 1767, 1771) and his Dissertations on the Origin, Nature, and Pursuits, of Intelligent Beings, and on Divine Providence, Religion, and Religious Worship of 1786.

In order to understand Holwell’s pursuit and intention, one needs to examine not only the second volume of his Interesting historical events (1767), which contains the Chartah Bhade Shastah “translation” with his commentary, but also the first and third volumes. The title page of the first volume (1765) indicates that Holwell had from the outset planned a three-part work of which the first was to present the historical events of India during the first half of the eighteenth century, the second “the mythology and cosmogony, fasts and festivals of the Gentoos, followers of the Shastah,” and the third “a dissertation on the metempsychosis.” In the first volume (published in 1765 and revised in 1766), there is an easily overlooked account that is crucial for understanding both the “Question of Holwell’s Veracity” and the character of his Chartah Bhade. Modern scholars paid no attention to it, but Voltaire highlighted this sensational report by Holwell in chapter 35 of his Fragmens sur l’Inde under the heading “Portrait of a singular people in India” (Voltaire 1774:212–16). Voltaire wrote:

Among so much desolation a region of India has enjoyed profound peace; and in the midst of the horrible moral depravation, it has preserved the purity of its ancient morality. It is the country of Bishnapore or Vishnapore. Mr. Holwell, who has travelled through it, says that it is situated in north-west Bengal and that it takes sixty days of travel to traverse it. (p. 212)

Quickly calculating the approximate size of this blessed territory, Voltaire concluded that “it would be much larger than France” (p. 212), and exhibited some of his much-evoked “complete trust” in Holwell by accusing him of “some exaggeration” (p. 212). But Voltaire did not exclude the possibility that it was someone else’s fault, for example, “a printing error, which is all too common in books” (p. 212). Instead of double-checking the number in his copy of Holwell’s book (which on p. 197 has “sixteen days” rather than “sixty”), Voltaire proceeded to correct Holwell:

We had better believe that the author meant [it takes] sixty days [to walk] around the territory, which would result in 100 [French] miles of diameter. [The country] yields 3.5 million rupees per year to its sovereign, which corresponds to 8,200,000 pounds. This revenue does not seem proportionate to the surface of the territory. (pp. 212–13)

Feigning astonishment, Voltaire adds: “What is even more surprising is that Bishnapore is not at all found on our maps” (p. 212). Could Holwell have invented this country? Of course not! “It is not permitted to believe that a state employee of known probity would have wanted to get the better of simple people. He would be too guilty and too easily refuted” (p. 212). When reporting biblical events that defy logic, Voltaire often cut the discussion short with a sarcastic exhortation to his readers to stop worrying about reason and to embrace faith. Here he “consoles” readers who are surprised that this blissful country is not found on any map with the tongue-in-cheek remark: “The reader will be even more pleasantly surprised that this country is inhabited by the most gentle, the most just, the most hospitable, and the most generous people that have ever rendered our earth worthy of heaven” (p. 213).

Today we know that Bisnapore (Bishnupur) is located only 130 kilometers northwest of Calcutta (Kolkata). The city is famous for its terracotta craft and Baluchari sarees made of tussar silk and was for almost a thousand years the capital of the Malla kings of Mallabhum. But Holwell’s report carries a far more paradisiacal perfume. The country that he reportedly visited is portrayed as the happiest in the world. It is protected from surrounding regions by an ingenious system of waterways and lock gates that gives the reigning Rajah the “power to overflow his country, and drown any enemy that comes against him.” Holwell, ever the sly and devoted colonial administrator, suggests that the British could avoid an invasion and easily bring the country to its knees through an export blockade that would oblige the Rajah to pay the British as much as two million rupees per annum (Holwell 1766:1.197–98). But, of course, this was just an innocent idea and by no means a call for the colonialization of paradise:

But in truth, it would be almost cruelty to molest these happy people; for in this district, are the only vestiges of the beauty, purity, piety, regularity, equity, and strictness of the ancient Indostan government. Here the property, as well as the liberty of the people, are inviolate. Here, no robberies are heard of, either private or public. (p. 198)

When a foreigner such as Holwell enters this country, he “becomes the immediate care of the government; which allots him guards without any expence, to conduct him from stage to stage: and these are accountable for the safety and accommodation of his person and effects” (p. 198). Goods are duly recorded, certified, and transported free of charge. “In this form, the traveller is passed through the country; and if he only passes, he is not suffered to be at any expence for food, accommodation, or carriage for his merchandize or baggage” (p. 199). Furthermore, the people of Bisnapore are totally honest:

If any thing is lost in this district; for instance, a bag of money, or other valuable; the person who finds it, hangs it up on the next tree, and gives notice to the nearest Chowkey or place of guard; the officer of which, orders immediate publication of the same by beat of tomtom, or drum. (p. 199)

The country is graced by 360 magnificent pagodas erected by the Rajah and his ancestors, and the cows are venerated to such a degree that if one suffers violent death, the whole city or village remains in mourning and fasts for three days; nobody is allowed to displace him- or herself, and all must perform the expiations prescribed by the very Chartah Bhade Shastah whose existence and content Holwell herewith first announced to the world (pp. 199–200).

The country described by Holwell is a carefully delimited territory within whose boundaries time seems to have stood still since the proclamation of the Chartah Bhade Shastah several thousand years ago. Its elaborate water management system with lock gates and canals offers total protection from the dangers of the outside world, and within its boundaries perfect honesty, piety, purity, morality, tolerance, liberty, generosity, and prosperity reign since time immemorial. Surely some of Holwell’s and Voltaire’s readers must have asked themselves why—given the free transport, food, accommodation, and even health care for visitors—Mr. Holwell was the only person ever to transmit the good news about this paradisiacal enclave at Calcutta’s doorstep. Is it too farfetched to think that Holwell endowed Bisnapore with its ideal characteristics in order to prepare the ground for the Chartah Bhade Shastah in the second volume of his Interesting events? If a real country with a real economy existed—a country whose religion was strictly based on the Chartah Bhade Shastah and whose rites had followed this text to the letter for millennia—then the existence of this ancient sacred text could not be subject to doubt, could it?

Of course, Holwell was not the first person to imagine a paradise in or near India; medieval world maps are full of interesting information about it. In the year 883, about eight hundred years before Holwell wrote about Bisnapore, a Jew by the name of Eldad ha-Dani (“Eldad of the tribe of Dan”) showed up in Tunisia.3 Presenting himself as a member of one of the ten lost tribes of Israel (which according to Eldad continued to flourish in Havilah), he told the local Jews a story that could have been written by Holwell. Beyond the boundaries of the known world, somewhere in Asia, he claimed, four tribes of the “sons of Moses” continue to lead pure lives protected by a river of rolling stones and sand called Sambatyon, and their laws and texts remain unchanged since antiquity.4 Their Talmud is written in the purest Hebrew, and their children never die as long as the parents are alive. Eldad supported his own credibility by an impressive genealogy stretching back to Dan, the son of Jacob. Eldad’s tales provoked an inquiry addressed to the rabbinical academy in Sura, Babylon; and while not much is known about the further fate of Eldad, his story pops up here and there in medieval manuscripts. Eventually, the inquiry triggered by his account and the response it received were printed in Mantua in 1480 (Wasserstein 1996:215).

About three centuries after Eldad, in 1122, a story with many similar elements began to make the rounds in Europe, and its protagonist ended up as a prominent feature on numerous illustrated world maps. It was the tale of John, archbishop of India, who had reportedly traveled to Constantinople and Rome. Patriarch John was said to be the guardian of the shrine of St. Thomas, the favorite disciple of Jesus; and through his Indian capital, so the story went, flow the “pure waters of the Physon, one of the rivers of Paradise, which gives to the world outside most precious gold and jewels, whence the regions of India are extremely rich” (Hamilton 1996:173).

In 1145, Otto von Freising also heard of “a certain John, king and priest, who lived in the extreme east beyond Armenia and Persia.” He reportedly was of the race of the very Magi who had come to worship the infant Christ at Bethlehem (p. 174). Otto first connected Prester John with the Magi and with Archbishop John, and soon after the completion of his History in 1157 three corpses exhumed in a church in Milan were identified as the bodies of the Three Magi (pp. 180–81). These relics were solemnly transported to the Cologne cathedral in 1164 and became objects of a religious cult (p. 183). It is around this time that a letter signed by a Prester John began to circulate in western Europe. In his letter Prester John portrays himself as the extremely rich and powerful ruler of the Three Indies, whose subjects include the Ten Lost Tribes beyond the river Sambatyon. Prester John claims to live very close to Paradise and emphasizes that he guards the grave of St. Thomas, the apostle of Jesus.

Though the country described in Prester John’s letter is richer and far larger than Holwell’s Bisnapore, it is also extremely hospitable and its inhabitants are perfectly moral: “There are no robbers among us; no sycophant finds a place here, and there is no miserliness” (Zarncke 1996:83). As in Holwell’s Bisnapore, “nobody lies, nor can anybody lie” (p. 84). All inhabitants of Prester John’s country “follow the truth and love one another;” there is “no adulterer in the land, and there is no vice” (p. 84).

The Prester John story became so widely known that the famous patriarch became a fixture on medieval world maps as well as a major motivation for the exploration of Asia (from the thirteenth century) and Africa (from the fifteenth century).5

Another layer in the archaeology of Holwell’s Indian paradise can be found in the famous Travels of Sir John Mandeville of the fourteenth century, a book that fascinated countless readers and travelers as well as researchers.6 Mandeville’s “isle of Bragman”—like Prester John’s Indies, Eldad’s land beyond the Sambatyon, and Holwell’s Bisnapore—is a marvelous land. Its inhabitants, though not Christians, “by natural instinct or law . . . live a commendable life, are folk of great virtue, flying away from all sins and vices and malice” (Moseley 1983:178). The still unidentified Mandeville, who habitually calls countries “isles,” described a great many of them in his Travels. But the country of the “Bragmans” (Brachmans, Brahmins) is by far the most excellent:

This isle these people live in is called the Isle of Bragman; and some men call it the Land of Faith. Through it runs a great river, which is called Thebe. Generally all the men of that isle and of other isles nearby are more trustworthy and more righteous than men in other countries. In this land are no thieves, no murderers, no prostitutes, no liars, no beggars; they are men as pure in conversation and as clean in living as if they were men of religion. And since they are such true and good folk, in their country there is never thunder and lightning, hail nor snow, nor any other storms and bad weather; there is no hunger, no pestilence, no war, nor any other common tribulations among them, as there are among us because of our sins. And therefore it seems that God loves them well and is well pleased by their manner of life and their faith. (p. 178)

Of course, the antediluvian patriarchs of the Old Testament who lived many years before Abraham and Moses were not yet Jews blessed with the special covenant with God, something only conferred finally after the Exodus from Egypt at Mt. Sinai, much less Christians. But the virtues of these antediluvians were so great that they enjoyed extremely long life spans. Mandeville’s Bragmans, too, though ignorant of God’s commandments as conveyed to Moses, are said to “keep the Ten Commandments” (p. 178) and enjoy the benefits:

They believe in God who made all things, and worship Him with all their power; all earthly things they set at nought. They live so temperately and soberly in meat and drink that they are the longest-lived people in the world; and many of them die simply of age, when their vital force runs out. (p. 178)

Like Holwell’s inhabitants of Bisnapore, they are a people without greed and want; all “goods, movable and immovable, are common to every man,” and their wealth consists in peace, concord, and the love of their neighbor. Other countries in the vicinity of the land of the Bragmans for the most part also follow their customs while “living innocently in love and charity each with another.” Almost like Adam and Eve in paradise before they sinned, these people “go always naked” and suffer no needs (p. 179).

And even if these people do not have the articles of our faith, nevertheless I believe that because of their good faith that they have by nature, and their good intent, God loves them well and is well pleased by their manner of life, as He was with Job, who was a pagan, yet nevertheless his deeds were as acceptable to God as those of His loyal servants. (p. 180)

Mandeville’s naked people are extremely ancient and have “many prophets among them” since antiquity. Already “three thousand years and more before the time of His Incarnation,” they predicted the birth of Christ; but they have not yet learned of “the manner of His Passion” (p. 180). These regions that evoke paradise and antediluvian times form part of the empire of Prester John. Mandeville explains: “This Emperor Prester John is a Christian, and so is the greater part of his land, even if they do not have all the articles of the faith as clearly as we do. Nevertheless they believe in God as Father, Son and Holy Ghost; they are a very devout people, faithful to each other, and there is neither fraud nor guile among them” (p. 169). In Prester John’s land, there are many marvels and close by, behind a vast sea of gravel and sand, are “great mountains, from which flows a large river that comes from Paradise” (p. 169).

The lands described by Eldad, Prester John, Mandeville, and Holwell share some characteristics that invite exploration. The first concerns the fact that all are associated with “India” and the vicinity of earthly paradise. In the Genesis account (2.8 ff.) God, immediately after having formed Adam from the dust of the ground, “planted a garden eastward of Eden” and put Adam there. He equipped this garden with trees “pleasant to the sight, and good for food,” as well as the tree of life at the center of the garden and the tree of knowledge of good and evil. The story continues:

And a river went out of Eden to water the garden; and from thence it was parted, and became into four heads. The name of the first is Pishon: that is it which compasseth the whole land of Havilah, where there is gold; and the gold of that land is good: there is bdellium and the onyx stone. (Genesis 2.10–12)

The locations of this “land of Havilah” and the river Pishon (or Phison) are unclear, but the other rivers are better known. The second river, Gihon, “compasseth the whole land of Ethiopia,” the third (Hiddekel) “goeth to the east of Assyria,” and the fourth river is identified as the Euphrates (Genesis 2.13–14). In his Antiquities, written toward the end of the first century C.E., the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus for the first time identified the enigmatic first river of paradise as the Ganges river and the fourth river (Gihon or Geon) as the Nile:

Now the garden was watered by one river, which ran round about the whole earth, and was parted into four parts. And Phison, which denotes a Multitude, running into India, makes its exit into the sea, and is by the Greeks called Ganges. . . . Geon runs through Egypt, and denotes the river which arises from the opposite quarter to us, which the Greeks call Nile. (trans. Whiston 1906:2)

The location of the “garden in Eden” (gan b’Eden), from which Adam was eventually expelled, is specified in Genesis 2.8 as miqedem, which has both a spatial (“away to the East”) and a temporal (“from before the beginning”) connotation. Accordingly, the translators of the Septuagint, the Vetus Latina, and the English Authorized Version rendered it by words denoting “eastward” (Gr. kata anatolas, Lat. in oriente), while the Vulgate prefers “a principio” and thus the temporal connotation (Scafi 2006:35). But the association of the earthly paradise and enigmatic land of Havilah with the Orient, and in particular with India, was boosted by Flavius Josephus and a number of Church fathers who identified it with the Ganges valley (p. 35) where, nota bene, Holwell located his paradisiacal Bisnapore.

For the Christian theologian AUGUSTINE of Hippo (354–430), too, Pishon was the Ganges River and Gihon the Nile, and his verdict that these rivers “are true rivers, not just figurative expressions without a corresponding reality in the literal sense” hastened the demise of other theories as to the identity of the Pishon and Gihon (p. 46). In the seventh century, ISIDOR of Seville (d. 636) described in his Etymologiae the earthly paradise among the regions of Asia as a place that was neither hot nor cold but always temperate (Grimm 1977:77–78). Isidor also enriched the old tradition of allegorical interpretations of paradise. If paradise symbolized the Christian Church, he argued, the paradise river stood for Christ and its four arms for the four gospels (p. 78).

The allegorical view of paradise as the symbol of the Church, watered by four rivers or gospels and accessed by baptism, had first been advanced by Thascius Caelius CYPRIANUS (d. 258) and became quite successful in Carolingian Bible exegesis (pp. 45–46). The Commemoratio Geneseos, a very interesting Irish compilation of the late eighth century, identified the Pishon with the Indus river and interpreted Genesis’s “compasseth the whole land of Havilah” as “runs through Havilah” while specifying that “this land is situated at the confines of India and Parthia” (p. 87). The Commemoratio also associates the Pishon with the evangelist “John who is full of the Holy Ghost,” and the gold of Havilah with “the divine nature of God [diuinitas dei] which John wrote so much about” (p. 87).

Such Bible commentaries helped to establish an association of paradise with the name “John,” with India, and with a mighty Indian river. Until the end of the fifteenth century, many medieval world maps depicted paradise somewhere in or near India (Knefelkamp 1986:87–92), and travelers like Giovanni MARIGNOLLI of the fourteenth or Columbus of the fifteenth century were absolutely convinced that they were close to the earthly paradise.

Their view that paradise itself was not accessible does not signify that for them “earthly paradise . . . was in a sense nowhere,” as Scafi (2006:242) argues. When Marignolli met Buddhist monks at the foot of Adam’s Peak in Ceylon, he noted that they “call themselves sons of Adam” and reports their claim that “Cain was born in Ceylon.” According to Marignolli, these monks lead a “veritably holy life following a religion whose founder, in their opinion, is the patriarch Enoch, the inventor of prayer, and which is professed also by the Brachmans” (Meinert 1820:85). No wonder that the missionary felt close to paradise. Did these monks not refrain from eating meat “because Adam, before the deluge, did not eat any,” and did they not worship a tree, claiming that this custom stemmed “from Adam who, in their words, expected future salvation from its wood” (p. 86)?7 Marignolli also reports about his arrival “by sea to Ceylon, to the glorious mountain opposite paradise which, as the indigens say according to the tradition of their fathers, is found at forty Italian miles’ distance—so [near] that one hears the noise of the water falling from the source of paradise” (p. 77)—and was proud to have visited Adam’s house “built from large marble plates without plaster,” which featured “a door at the center that he [Adam] built with his own hands” (pp. 80–81). A pond full of jewels was reportedly fed by the source of paradise opposite the mountain, and Marignolli boasted of having tasted the delicious fruit of the paradise (banana) tree, whose leaves Adam and Eve had used to cover their private parts (pp. 81–83).

Figure 14. Paradise near India at Eastern extremity of Osma world map (Santarem 1849).

This paradise mythology was very influential and far reaching, and it shows itself sometimes in perhaps unexpected domains. Christopher COLUMBUS (1451–1506), a man who was very familiar with maps and had once made a living of their trade, also thought that he approached the earthly paradise on his third voyage. While he cruised near the estuary of the Orinoco in Venezuela, he firmly believed he had finally reached the mouth of a paradise river.

Holy Scripture testifies that Our Lord made the earthly Paradise in which he placed the Tree of Life. From it there flowed four main rivers: the Ganges in India, the Tigris and the Euphrates in Asia, which cut through a mountain range and form Mesopotamia and flow into Persia, and the Nile, which rises in Ethiopia and flows into the sea at Alexandria. I do not find and have never found any Greek or Latin writings which definitely state the worldly situation of the earthly Paradise, nor have I seen any world map which establishes its position except by deduction. (Columbus 1969:220–21)

Since Columbus knew that the earth is round and that he was far away from Africa and Mesopotamia, he apparently thought that he was in the “Indies” and noted the unanimity of “St Isidor, Bede, Strabo, the Master of Scholastic History [Petrus Comestor], St Ambrose and Scotus and all learned theologians” that “the earthly Paradise is in the East” (p. 221). Columbus clearly imagined himself near the Ganges and the Indian Paradise.

I do not hold that the earthly Paradise has the form of a rugged mountain, as it is shown in pictures, but that it lies at the summit of what I have described as the stalk of a pear, and that by gradually approaching it one begins, while still at a great distance, to climb towards it. As I have said, I do not believe that anyone can ascend to the top. I do believe, however, that, distant though it is, these waters may flow from there to this place which I have reached, and form this lake. All this provides great evidence of the earthly Paradise, because the situation agrees with the beliefs of those holy and wise theologians and all the signs strongly accord with this idea. (pp. 221–22)

Who would have thought that the “Indian” fantasies of Flavius Josephus, Augustine, and the medieval theologians and cartographers in their wake would one day play a role in the discovery of the Americas? But while Columbus was looking forward to exploring the East Indies and enriching himself with the gold and jewels promised by the Bible commentators, the heyday of the “Indian” Paradise on world maps was coming to a close. In 1449, Aeneas Silvius PICCOLOMINI (1405–64; Pope Pius II from 1458–64) had already come to doubt the identification of the Gihon with the Nile (Scafi 2006:197), and soon the learned Augustinus STEUCHUS (1496–1549) argued that Pishon and Gihon had nothing to do with the Ganges and Nile since Havilah and Cush were not located in India and Ethiopia but in Mesopotamia and Arabia (p. 263).

Subsequently, the location of earthly paradise became unhinged and drifted for a time; Guillaume Postel, for example, first located it in the Moluccas, the home of the paradise birds (Postel 1553a), but subsequently made a U-turn and placed it near the North Pole (Secret 1985:304–5). Though arguing that the entire earth had once been paradise, Postel’s contemporary Jan Gorp (Goropius Becanus) of Antwerp believed that Adam had lived in India (Gorp 1569:483, 508) and that Noah’s ark had landed not on Mt. Ararat but on the highest mountains of the Indian Caucasus, that is, near Mt. Imaus in the mountain range that we now call the Himalaya (p. 473). In his History of the World of 1614, Sir Walter Raleigh called this view “of all his conjectures the most probable” (1829.2.243); and around the end of the seventeenth century, some physical theories related to the deluge and the formation of the earth also revived Gorp’s idea that the entire earth had initially been paradise (Burnet 1694). However, around the turn of the eighteenth century most specialists of biblical exegesis tended to place earthly paradise somewhere near the Holy Land.

While the physical paradise had found a more or less stable abode in the Middle East, the search for the religion of paradise entered a period of chaos. Textual criticism of the Bible increasingly threatened scripture’s claims to antiquity and authenticity; Moses’s ancient “Egyptian” background was explored; and gradually texts from far-away China and India that purportedly were much older than the Old Testament entered the picture.

In contrast to physical and historical interpretations, some allegorical or spiritual (spiritaliter) Bible commentaries likened the lands in the vicinity of the Ganges to the holy Church, its gold to the genuine conception of monotheism, and the four cardinal virtues and foundational gospels to the four paradise rivers (Grimm 1977:87). The land of the Ganges was thus associated with the pure original teaching of Christianity, and Christianity in turn with humankind’s first religion that was personally revealed by God to Adam before the Fall. Indeed, the view of “India” as a motherland of original teachings is a characteristic that links the reports by or about Eldad, Prester John, Mandeville, Prince Dara, Holwell, and Voltaire. They all portray pure original teachings and practices that survived in or near India: Eldad of the original Judaism of the sons of Moses, Prester John of the Ur-Christianity of St. Thomas, Mandeville of the seemingly antediluvian monotheism of the Bragmans, Prince Dara of Ur-Islam, Voltaire of Ur-deism, and Holwell of the Ur-religion. Characteristically, each author also had a particular reform agenda that is apparent or implicit in the critique of the reigning religion as degenerate compared to “Indian” teachings and practices.

The example of Mandeville’s Travels is quite instructive. The pilgrimage motif that forms the setting for his entire tale is really “a metaphor for the life of man on earth as a journey to the Heavenly Jerusalem”—but this promised land can only be reached if Christians reform themselves (Moseley 1983:23). Interestingly, the model for this reform is found not in Rome or the Holy Land but rather in far-away India. This region in the vicinity of the earthly paradise and its extremely ancient religion are held up as a mirror by Mandeville to make his Christian readers blush in shame. Prester John, the guardian of the shrine of Jesus’s favorite disciple, managed to keep original Christianity pure and heads an ideal Christian state where even the empire’s heathen live in ways that Christians should imitate.

Mandeville’s description of non-Christian religions, particularly those of the regions near paradise, thus has a definite “Ambrosian” character and very much resembles Voltaire’s use of the Ezour-vedam and Holwell’s Shastah (see Chapter 1). Like St. Ambrose’s Brachmanes (Bysshe 1665), Eldad’s Ur-Jews, Voltaire’s Indian Ur-deists, Holwell’s Vishnaporians, and Prester John’s prototype Christians, the heathens and Christians of Mandeville’s India have the mission of encouraging European Christians to reflect upon themselves and to reform their religion according to the “Indian” ideal. In each case, the model is the respective Ur-tradition—appropriately set in the vicinity of paradise—which forms both the point of departure and the ultimate goal. This goal can typically be reached by a “regeneration of the original creed” that entails eliminating degenerate accretions and stripping religion down to its bare Ur-form.

As we have seen in Chapter 4, the three-step scheme of golden age/degeneration/regeneration and return to the golden age formed the backbone of Andrew Ramsay’s book The Travels of Cyrus, first published in French and English in 1727. It was a smashing success; a Dublin print of 1728 is already marked as fourth edition (Ramsay 2002:7). One of its readers in London may have been a London liveryman8 whose Oration, published in 1733, caught Holwell’s attention at an early stage and influenced him so profoundly that he “candidly confessed” in the third volume of his Interesting historical events that the “well grounded” yet “bold assertions of Mr. John Ilive”9 had given him the “first hints”:

[It was Mr. Ilive’s bold yet well grounded assertions] from whom we candidly confess we took our first hints, and became a thorough convert to his hypothesis, upon finding on enquiry, and the exertion of our own reason, that it was built on the first divine revelation that had been graciously delivered to man, to wit, THE CHARTAH BHADE OF BRAMAH; although it is very plain Mr. Ilive was ignorant of the doctrine of the Metempsychosis, by confining his conceptions only to the angelic fall, man’s being the apostate angels, and that this earth was the only hell; passing over in silence the rest of the animal creation. (Holwell 1771:3.143)

Jacob ILIVE (1705–63) was a printer, owner of a foundry, and religious publicist who in 1729 wrote down a speech, read it several times to his mother, and was obliged by his mother’s testamentary request to proclaim it in public. Ilive went a bit further; after his mother’s death in 1733, he read it twice in public and then printed it in annotated form. Later he rented Carpenters’ Hall and lectured there about “The religion of Nature” (Wilson 1808:2.291). His Oration of 1733, which so deeply influenced Holwell, addresses several themes of interest to deists such as the origin of evil, original sin, eternal punishment, and the reliability of Moses’s Pentateuch. Ilive offered more or less creative solutions to all of the above. Moses was for him not only a typical representative of “priestcraft” but one who began his career with a vicious murder. “I observe, that for the Truth of this, we have only Moses’s ipse dixit, and I think a Man may chuse whether he will believe a Murderer” (Ilive 1733:37). Moses not only commanded people to steal and cheat but he also contrived “a great Murder, yea, a Massacre” while lying to his people as he told them that “the Lord God of Israel” had ordered “to slay every Man his Brother, and every Man his Neighbour” (p. 42). Ilive regarded the author of the Pentateuch as far from inspired:

What is to be understood by delivering Laws as the Result of Divine Appointment, if hereby is not meant, that Moses had for every Law and Ordinance he instituted not received miraculously and immediately the Command of the Great God of Heaven, but delivered them to the Jews only as (what he thought) agreeable to the Mind of God. (p. 41)

Ilive was not content with the Reformation either and described how the first reformers “glossed away the Christian truths”:

In the first Article they say God is without Body, Parts, or Passions: in the second they sware, that God the Son has Body and Parts now in Heaven. In the third, that he went down into Hell, i.e. into the Centre of the Earth, or a distinct Creation from the Earth, I suppose is meant. Article Six they do not insert here, that the Books of the Old Testament were written by the Inspiration of the Holy Ghost, but they dub all the Stories contained in them for Truth. In Article seven, they are not Jews; but because the Old Testament would be necessary to back Christianity, they say, therefore, it is to be held in respect. In the ninth they establish three Creeds at once: in two of them this absurd Doctrine, the Resurrection of the Body, or Flesh. It is too tedious to go through them all. (pp. 43–44)

Ilive was clearly planning a more thorough reform of Christianity and was not happy with the Pentateuch. He felt that Moses had not explained who we are and why we are here in “the Place we now inhabit” (p. 9). Inspired by the notions that there is a plurality of worlds, that our world was created long after a more perfect one, and that souls preexisted, Ilive came up with a scenario that could very well have been inspired by Ramsay’s Discourse upon the Theology and Mythology of the Pagans at the end of the Travels of Cyrus. The Discourse contains almost all the central elements of Ilive’s system and appeared in 1727, exactly two years before Ilive apparently wrote his text, in the city of London where Ilive happened to earn his living in the printing business. As we have seen in the previous chapter, Ramsay had traced in the kabbala and various ancient cultures the idea that angels had fallen from their state of perfection and were exiled; that they formed the souls of beings on planets that are like hospitals or prisons for these fallen higher intelligences; that they were there imprisoned in the bodies of men; and that they had to migrate from one body to another until their purification was complete and the return to their initial state of perfection possible. This was the central theme of Ramsay’s Of the Mythology of the Pagans where it was presented as “a very ancient doctrine, common to all the Asiatics, from whom Pythagoras and Plato derived it” (Ramsay 1814:384–85). The idea had also played an important role in early Church heresiology since it was one of the main accusations leveled against Origenes (c. 185–254).10

Ramsay called this “the doctrine of transmigration,” and its features of “a first earth” where “souls made their abode before their degradation, the “terrestrial prison” where they are confined, and the divine plan for their rehabilitation in order to regain their original state (pp. 366–67) form the very fabric of Ilive’s system that so inspired Holwell. It is a classic golden age/ degeneration/regeneration scenario proposed by people intent on reforming the degenerate Christian religion and defending ideal Christianity against “all the Atheists” including “Spinoza, Hobbes, Toland, &c.” (Ilive 1733:25). The task was to show that the world was “created for the Good and Benefit” and that its evils (ignorance, wars, cruelty, illness, etc.) are not due to the creator God’s sadism but are part and parcel of his compassionate rehabilitation plan for fallen angels. Since “there has not been given as yet any real satisfactory Reason for the Creation of the World,” Ilive (and in his wake, Holwell) attempted to furnish exactly that: an improved creation story. While Holwell eventually cobbled together an “Indian” one and presented it as a better (and older) Old Testament, Ilive relied mostly on inspired interpretations of New Testament passages.11

Ilive’s creation story begins long before Adam enjoyed paradise. “Many years, as we compute Time, before the Creation of Man,” God “thought fit to reveal the Eternal Word, his Equal, unto the Angels” (p. 10). While two thirds of them “were chanting forth their Halleluja’s,” another third were “seized with Anger and Pride” and rebelled (pp. 11–12). Soon there was war in heaven, and the rebels were cast “into this very Globe . . . which we now inhabit, before its Formation out of Chaos” (p. 15). At that time the earth was just a “Place of Darkness, and great Confusion, a rude Wilderness, an indigested Lump of Matter.” The matter “out of which this World was formed, was prae-existent to the Formation of the Earth, and to the Creation of Man,” and this dark chaotic world “was a Dungeon for the Punishment of the Lapsed Angels, and the Place of their Residence” (p. 26). After about 6,000 years of such confinement in chaos, “God began the Formation of the World” (p. 16) as we know it. Whereas for Milton this formation of the second world was designed to repopulate heaven by giving men on earth the chance to join the diminished number of good angels in heaven (Milton 2001:163; book 7, verses 150–60), Ilive regarded it as an act of divine compassion with the aim of giving the banished angels a chance for rehabilitation. Our planet earth, therefore, is, as it were, a rehabilitation center for rebel angels, and the bodies of men are “little Places of Confinement for the Reception of the apostate Angels” within this gigantic facility (Ilive 1733:23). Contrary to Holwell’s assertion (1771:3.143), transmigration is clearly part of Ilive’s design since rehabilitation and purification can take a very long time: “The Reader is desired to observe, that I suppose the Revolutions of these Angels in Bodies, and that they may have actuated or assumed Bodies many times since the Creation, in order for their Punishment, Probation and Reconciliation” (Ilive 1733:24).

In Ilive’s narrative, human souls are thus fallen angels who must atone for past rebellious acts in small prison cells (our bodies) within a facility (the earth) that was created for the very purpose of punishing and rehabilitating them. One might say that our earth resembles a giant Guantanamo Bay prison camp, which during the administration of U.S. president George W. Bush was established as a facility tailor-made to house evil spirits (terrorists) brought in by “extraordinary rendition.” The delinquents were incarcerated without the possibility of appeal since they were considered outlaws undeserving of the ordinary course of justice. The worst offenders were subjected to the trademark “Guantanamo frequent flier program” in which prisoners were constantly moved from cell to cell after short periods of sleep. In terms of our metaphor, they had to undergo seemingly endless transmigration from body to body and feel lucky if they got to inhabit a better cell for a little while. The final goal of this grueling regime was atonement, rehabilitation, and eventual release; but since this was a realm without habeas corpus rights, the best the prisoners could do was to follow the rules in order to accumulate expiation points. Regaining their original status and returning home, however, possibly necessitated an almost endless sequence of transmigrations.

In the Historical events, Holwell makes a great effort to convey the impression that his entire system is based on the Chartah Bhade Shastah of Bramah and that he is no more than a translator and commentator of an ancient text who intends “to rescue from error and oblivion the ancient religion of Hindostan”12 and to “vindicate” it “not by labored apologies, but by a simple display of their primitive theology.”13 Following Holwell’s candid confession that he took his “first hints” from Ilive and “became a thorough convert to his hypothesis,” one would expect him to acknowledge that he subsequently found a similar system in the Shastah. Instead, Holwell makes the startling claim (1771:3.143) that Ilive’s system “was built on the first divine revelation that had been graciously delivered to man, to wit, THE CHARTAH BHADE OF BRAMAH”!

Not only Egyptian religion and the Pythagorean system but even Ilive’s ideas are thus supposedly based on an ancient Indian text whose two manuscripts Holwell claims to have bought very dearly and thereafter lost in the sack of Calcutta:

It is well known that at the capture of Calcutta, A.D. 1756, I lost many curious Gentoo manuscripts, and among them two very correct and valuable copies of the Gentoo Shastah. They were procured by me with so much trouble and expence, that even the commissioners of the restitution, though not at all disposed to favour me, allowed me two thousand Madras rupees in recompense for this particular loss; but the most irreparable damage I suffered under this head of grievances, was a translation I made of a considerable part of the Shastah, which had cost me eighteen months hard labour: as that work opened upon me, I distinctly saw, that the Mythology, as well as the Cosmogony of the Egyptians, Greeks and Romans, were borrowed from the doctrines of the Bramins, contained in this book; even to the copying their exteriors of worship, and the distribution of their idols, though grossly mutilated and adulterated. (Holwell 1765:1.3–4)

If Holwell had spent no less than eighteen months of “hard labor” to translate a “considerable part” of the Shastah, then one must assume that he had bought a text of gigantic proportions. The manuscripts that he owned and translated were, he says, lost in 1756. However, he claims to have recovered “some manuscripts . . . by an unforeseen and extraordinary event” that allowed him to publish his translation; but though he tantalizingly adds that he “possibly” may “recite” this wondrous recovery afterward (p. 4), he never explained himself, and nobody has ever seen an original manuscript. One is reminded of James Macpherson’s phantom Ossian manuscripts that excited the curiosity of an entire generation of Europeans after the publication of their English “translation” in 1761. But though there are some striking similarities one notes a major difference: Macpherson’s Ossian was very prolix compared to Holwell’s Brahma. Holwell’s entire translation from the Shastah amounts to a skimpy 531 lines, printed in large type on narrow pages with very conspicuous quotation marks at the beginning of each line. In fact, there was so little substance that Edmund Burke decided to include Holwell’s entire translation in his Annual Register book review (1767:310–16), and it fit neatly on six and a half pages!

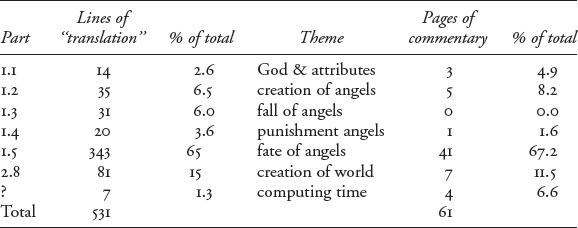

This means that the “unforeseen and extraordinary event,” which Holwell never explained, yielded very little material. Moreover, over 80 percent of the translated text deals with the fate of angels: their creation, their fall, their punishment, and of course their incarceration on “rehab station” earth. A single section entitled “The Mitigation of the Punishment of the delinquent Debtah, and their final Sentence” (Holwell 1767:2.47–59)—which basically replicates Jacob Ilive’s argument spiced up with some Indian terminology—constitutes no less than two thirds of Holwell’s Shastah translation; see Figure 15. This is the section that explains the core of Holwell’s system, namely, that human bodies host the souls of rebellious angels; that the earth was created as a rehabilitation facility in which these souls could purify themselves in successive existences; that transmigration is part of this rehabilitation process; and that vegetarianism is obligatory for the obvious angelic reason

Figure 15. Chapter theme percentages of Holwell’s Shastah translation (Urs App).

Table 10 shows that the volume of Holwell’s commentaries on sections translated from the Shastah is similarly lopsided.

The thematic analysis of Holwell’s Shastah fragments indicates that the Shastah author’s interests strangely resemble those of Ilive and that the possibility of an ancient Indian origin seems remote. But does the content of Holwell’s text—which purportedly “is as ancient, at least, as any written body of divinity that was ever produced in the world” (Holwell 1767:2.5)—support such doubts about the Shastah’s authorship? Let us examine the first section of Holwell’s translation, which is shown in Figure 16.

While an ancient Indian inspired by Brahma might have had other ideas, a European would quite naturally tend to have a catechism begin with an affirmation of monotheism and a creator God. The very first sentence of the Shastah already points toward an author familiar with Christian theology. Holwell seems to have vacillated on how to formulate this crucial initial statement that echoes God’s first commandment to Moses. The text cited in Burke’s review in the Annual Register for the Year 1766 (1767:310) must stem from the galley proofs and begins with “God is the one that ever was” in place of the final version’s “God is ONE.” If Holwell’s Indian text—which was written in Hindi, as his note suggests—contained the words ek (one) and hamesha (always), then “the one that ever was” or “the eternal one” seem just fine. So why did Holwell at the last minute decided to change his initial translation (which did not need a note) to “God is ONE” and to banish the literal translation into a note? Did a unitarian friend who read the proofs suggest this, or did Holwell try to “improve” the text Voltaire-style? At any rate, the published text begins with a strong statement against trinitarianism.

TABLE 10. TEXT PERCENTAGES IN HOLWELL’S TRANSLATIONS PER THEME

That this God rules all creation by “general providence resulting from first determined and fixed principles” again points to an author familiar with eighteenth-century theological controversies. Moreover: what ancient Indian author would have thought of prohibiting research about the laws by which God governs? Here, too, one has reason to suspect the interference of a certain eighteenth-century author who was opposed to scientific research into the laws of nature. It so happens that Holwell had exactly this attitude. Pointing out that Solomon had called the “pursuits of mankind, in search of knowledge, arts, and sciences . . . all futile and vain,” Holwell called it a Christian reformer’s duty “to prevent the misapplication of time, expence, and talents, which might be employed for better purposes” (1786:45). Of what significance is it, he asks (p. 46), “to know whether our globe stands still, or has a daily rotation from East and West?” This might sound strange coming from a man who had traveled so much at sea, but Holwell offered an explanation in tune with Brahmah’s will:

Figure 16. First section of Holwell’s Shastah in review and published versions.

It is highly improbable, that when the DEITY planted the different regions of this globe with the fallen spirits, or intelligent beings, his design was, they should ever have communication with each other; his placing the expanded and occasionally tempestuous ocean between them exhibits an incontestable proof to the contrary. But in this as in every thing else, man has counteracted his wise and benevolent intentions. (pp. 49–50)

The first lines of the Shastah thus already strongly indicate European authorship. Another example suggesting an eighteenth-century author is the crucial passage in Section 2, titled “The Creation of Angelic Beings.”

The ETERNAL ONE willed.—And they were.—He formed them in part of his own essence; capable of perfection, but with the powers of imperfection; both depending on their voluntary election. (Holwell 1767:2.35)

In his commentary Holwell explains that this passage is related to the problem of “free will” and “the origin, and existence of moral evil” (p. 39). Here he openly joins the fray and attacks authors “who have been driven to very strange conclusions on this subject” and even “thought it necessary to form an apology in defence of their Creator, for the admission of moral evil into the world” (p. 39). One of the culprits is Soame Jenyns’s A Free Inquiry into the Nature and Origin of Evil whose fourth edition appeared in 1761 just after Holwell’s final return to England. Holwell quotes from Jenyns’s book and then contrasts it with the Shastah’s solution that is, in his eyes, by far the best to date:

How much more rational and sublime [than such eighteenth-century apologies is] the text of Bramah, which supposes the Deity’s voluntary creation, or permission of evil; for the exaltation of a race of beings, whose goodness as free agents could not have existed without being endued with the contrasted or opposite powers of doing evil. (p. 41)

Though Holwell gives all the credit to his Shastah, this was an ingenious if somewhat circular solution that both Ilive and Ramsay had proposed.

Whoever authored the Shastah, it certainly addressed problems of utmost interest not to any ancient Indian author but rather to a certain eighteenth-century Englishman familiar with Indian religion as well as the theological controversies of his time. Is it not noteworthy that Holwell seems to have recuperated only Shastah sections that deal exactly with the questions he felt passionate about? One gets the distinct feeling that he was considerably more than just a translator of “Bramah’s” ancient text, and as one reads on, the signs pointing to Holwell multiply. Section 4 of the Shastah begins with the words: “The eternal ONE, whose omniscience, prescience and influence, extended to all things, except the actions of beings, which he had created free” (p. 44). In his remarks Holwell points out that this section begins “by denying the prescience of God touching the actions of free agents” and that “the Bramins defend this dogma by alleging, his prescience in this case, is utterly repugnant and contradictory to the very nature and essence of free agency, which on such terms could not have existed” (p. 46). Whatever these Bramins may have explained to Holwell, here it is old Bramah himself who seems to react to the attacks of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century deist writers, and it is striking how familiar he is not only with Indian religion but also—as his omniscience and prescience would have one expect—with eighteenth-century Europe’s theological controversies!

It is certain that during his long stay in India Holwell had conversed with many Indians about their religions. He severely criticized Western authors who “have (either from their own fertile inventions, or from mis-information, or rather from want of a competent knowledge in the language of the nation) misrepresented” the Indians’ religious tenet (pp. 4–5). Holwell was proud of having studied the language and to have had “various conferences with many of the most learned and ingenious, amongst the laity of the Koyt,” the tribe of writers,14 as well as “other Casts, who are often better versed in the doctrines of their Shastah than the common run of the Bramins themselves” (p. 21). Holwell also mentions a “judicious Bramin of the Battezaar tribe, the tribe . . . usually employed in expounding the Shastahs” who explained images to him (p. 113). It is from such Indians that Holwell claims to have learned about the origin of his text.15 But the origin and other aspects of this text are clouded by a number of strange contradictions. On one hand, Holwell openly admitted that his idea of “the antiquity of the scriptures”—namely, that the Shastah of Bramah “is as ancient, at least, as any written body of divinity that was ever produced in the world”—is based upon “our conjecture and belief” (p. 5) and emphasized that the ideas of the Brahmins are not very trustworthy and that they led to conjectures rather than historical facts:

Without reposing an implicit confidence in the relations the Bramins give of the antiquity of their scriptures; we will with our readers indulgence, humbly offer a few conjectures that have swayed us into a belief and conclusion, that the original tenets of Bramah are most ancient; that they are truly original, and not copied from any system of theology, that has ever been promulged to, or obtruded upon the belief of mankind: what weight our conjectures may have with the curious . . . we readily submit to those, whose genius, learning and capacity in researches of this kind, are much superior to our own. (p. 23)

On the other hand, Holwell presented an elaborate scheme of the origin of Indian sacred literature with precise dates: it was precisely “4866 years ago” (3100 B.C.E.) that the Almighty decided to have his sentence for the delinquent angels “digested into a body of written laws for their guidance” and ordered Bramah, “a being from the first rank of angels . . . destined for the eastern part of this globe,” to transmit God’s “terms and conditions” to the “delinquents” (pp. 11–12). Bramah “assumed the human form,” translated God’s sentence from “Debtah Nagur (literally, the language of angels)” into “the Sanscrît, a language then universally known throughout Indostan.” This oldest book of the world “was preached to the delinquents, as the only terms of their salvation and restoration” and is known as “the Chartah Bhade Shastah of Bramah (literally, the four scriptures of divine words of the mighty spirit)” (p. 12). This was the text that Holwell claimed to have found, translated, lost, found again in fragments, translated again, and finally published in 1767. Since Holwell’s text titles are a bit confusing—he claims at the bottom of the same page that Bhade means “a written book”—I will call this first Sanskrit scripture from 3,100 B.C.E. “Text I.”

For a thousand years Text I remained untouched and many delinquent angels were saved by its teachings; but in 2100 B.C.E. some commentators wrote a paraphrase called Chatah Bhade of Bramah or “the six scriptures of the mighty spirit” and began to “veil in mysteries the simple doctrines of Bramah” (pp. 12–13). The product of these commentators, Text II, consisted of Text I plus comments.

Again five hundred years later, in 1600 B.C.E., a second exposition swelled “the Gentoo scriptures to eighteen books”; this was Text III, called “Aughtorrah Bhade Shastah, or the eighteen books of divine words” (pp. 14–15). In Text III the original scripture of Bramah, Text I, “was in a manner sunk and alluded to only” and “a multitude of ceremonials, and exteriour modes of worship, were instituted,” while the laity was “precluded from the knowledge of their original scriptures” and “had a new system of faith broached unto them, which their ancestors were utterly strangers to” (p. 14).

Text III “produced a schism amongst the Gentoo’s, who until this period had followed one profession of faith throughout the vast empire of Indostan” (p. 14). But now the Brahmins of South India formed a scripture of their own, “the Viedam of Brummah, or divine words of the mighty spirit” (Text IV: p. 14). The southerners claimed that their Viedam ( = Veda) was based on Text I; but in reality they had, like the authors of Text III, included all kinds of new things and even “departed from that chastity of manners” still preserved in Text III.

While the southerners based their religion on the Viedam (Text IV), the northerners continued to use the Aughtorrah Bhade Shastah (Text III):

The Aughtorrah Bhade Shastah, has been invariably followed by the Gentoos inhabiting from the mouth of the Ganges to the Indus, for the last three thousand three hundred and sixty six years. This precisely fixes the commencement of the Gentoo mythology, which until the publication of that Bhade, had no existence amongst them. (p. 18)

Having read about Holwell’s “conjecture” and “belief,” the reader is astonished to find such a precisely dated genealogy of the sacred scriptures of India. To ensure that the reader understands that this is not Holwell’s personal “conjecture” and “belief,” every line of this 12-page history (pp. 9–21) begins with a quotation mark. But who said or wrote all this, including what was just quoted about the precise beginning of Gentoo mythology? Holwell calls it a “recital” that he had heard “from many of these [learned Bramins]”—which must signify that these twelve pages, in spite of no less than 329 conspicuous quotation marks, present no quotation at all but rather a kind of summary of things that Holwell had heard at various times from a variety of people.

However, in Europe, Holwell’s fake precision had a great impact. In the second volume of his Interesting historical events (1767), Holwell delivered extended “quotations” from numerous “learned among the Bramins” (p. 9) who hitherto had hardly discussed such things with foreigners; he ostensibly translated parts of the world’s most ancient book; he declared that this text was much older and more authentic than the Veda that the Europeans had coveted for so long; he explained the origin and unity of Indian religion (the religion of the Gentoos or, as we would say today, the Hindus); he furnished precise dates for a “schism” that had set the religion of the South against that of the North; and he asserted that his Shastah was the one and only original revelation that God had granted to the ancient Indians. Holwell’s “conjecture and belief” seemed to have vanished underneath a giant heap of certified facts.

Another contradiction that strikes the reader concerns the story Holwell weaves around the transmission of his Shastah text. On one hand, he claims that this text was extremely rare and hard to find; hence, the high price he had to pay for the acquisition of the two manuscripts lost in 1756, the failure of acquiring a replacement after that, and the miraculous (though unexplained) recovery of just a few fragments. On the other hand, the Shastah text seems to have been rather well transmitted. Holwell claims to have had not just one but two complete copies in the early 1750s and insisted that it was from recovered fragments of this original text that he translated the chapter on the fate of the delinquent angels (which forms 65 percent of the entire translation).16 Furthermore, Text I could not have been rare since it was also included in Text II and to some extent in Text III, which both “derive their authority and essence, in the bosom of every Gentoo, from the Chartah Bhade of Bramah” (p. 29), and could easily be consulted when the need arose:

It is no uncommon thing, for a Gentoo, upon any point of conscience, or any important emergency in his affairs or conduct, to reject the decision of the Chatah [Text II] and Aughtorrah Bhades [Text III], and to procure, no matter at what expence, the decision of the Chartah Bhade [Text I], expounded in the Sanscrît. (p. 29)

Those who included Text I in Text II, commented on it, and eventually produced Text III—“some Goseyns and Battezaaz Bramins”—obviously also had access to Text I (p. 13):

Thus the original, plain, pure, and simple tenets of the Chartah Bhade of Bramah (fifteen hundred years after its first promulgation) became by degrees utterly lost; except, to three or four Goseyn families, who at this day are only capable of reading, and expounding it, from the Sanscrît character; to these may be added a few others of the tribe of the Batteezaaz Bramins, who can read and expound from the Chatah Bhade [Text II], which still preserved the text of the original, as before remarked. (p. 15)

Also blessed with access to Text I were apparently “many of the most learned and ingenuous, amongst the laity of the Koyt, and other Casts, who are often better versed in the doctrines of their Shastah than the common run of the Bramins themselves” (p. 21). Furthermore, as mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, Holwell reported that there existed an entire country near Calcutta whose religion had forever been based on Text I and that had preserved paradisiacal purity! And just before the end of his second volume, Holwell mentions another group who intimately knows Text I and seems also on course to paradise:

The remnant of Bramins (whom we have before excepted) who seclude themselves from the communications of the busy world, in a philosophic, and religious retirement, and strictly pursue the tenets and true spirit of the Chartah Bhade of Bramah, we may with equal truth and justice pronounce, are the purest models of genuine piety that now exist, or can be found on the face of the earth. (p. 152)

Yet another contradiction concerns the language of Text I. Holwell stated that his text first existed in the language of angels17 and was then translated and promulgated in Sanskrit. He accused missionaries as well as “modern authors . . . chiefly of the Romish communion” of having presented “the mythology of the venerable ancient Bramins on so slender a foundation as a few insignificant literal translations of the Viedam” that were not even “made from the book itself, but from unconnected scraps and bits, picked up here and there by hearsay from Hindoos, probably as ignorant as themselves” (Holwell 1765:1.6). Holwell, by contrast, was using the unadulterated original Shastah text rather than the degenerate southern “Viedam,” and his thirty-year sojourn in Bengal (p. 3) had supposedly equipped him to deal with this original text. Holwell never claimed openly to have studied Sanskrit, but the reader of his account gets the impression, as Voltaire did, that Holwell knew Sanskrit since he was able to translate the ancient text and labored for many months to produce not only a literal translation but one that even took the diction and style of the original into account. But it is evident that Holwell never studied Sanskrit and that the Indian words he quotes from Text I are not Sanskrit.

There are also many unanswered questions concerning Holwell’s recovery of some fragments of the Shastah that ought to have taken place before his return to England in 1761. A comparison of Holwell’s announcement in 1765 with the actual content of the 1767 volume seems to indicate that, in 1765, Holwell was not yet planning to include any translations from the Shastah except for the creation account. The 1765 announcement only mentioned “A summary view of the fundamental, religious tenets of the Gentoos, followers of the Shastah” and “A short account, from the Shastah, of the creation of the worlds, or universe” (p. 15). The latter became in 1767 the eighth section of the Shastah’s second book (1767:2.106–10). Why did Holwell in his first volume (on whose title page the second and third parts were already announced) not lose a single word about the literal translations he was about to publish from the world’s oldest text? Did Holwell decide around 1766 to transform his “summary view of the fundamental religious tenets of the Gentoos” into “translations”? The content of the Shastah texts as well as their style, inspired as they seem by Milton’s Paradise Lost, Salomon Gessner’s Death of Abel (1761), and James “Ossian” Macpherson’s Fragments of Ancient Poetry (1760), also point in that direction. Are all those hundreds of quotation marks signs of a bad conscience?

Contradictions pertaining to Holwell’s (and Ilive’s) system will go unmentioned here, except for one related to the salvation of fish that was pointed out in a delightful passage by Julius Mickle who noted many suspicious facets of Holwell’s text:

Nature has made almost the whole creation of fishes to feed upon each other. Their purgation therefore is only a mock trial; for, according to Mr. H[olwell] whatever being destroys a mortal body must begin its transmigrations anew; and thus the spirits of the fishes would be just where they were, though millions of the four Jogues [yugas; world ages] were repeated. Mr. H. is at great pains to solve the reason why the fishes were not drowned at the general deluge, when every other species of animals suffered death. The only reason for it, he says, is that they were more favoured of God, as more innocent. Why then are these less guilty spirits united to bodies whose natural instinct precludes them the very possibility of salvation? (Mickle 1798:190)

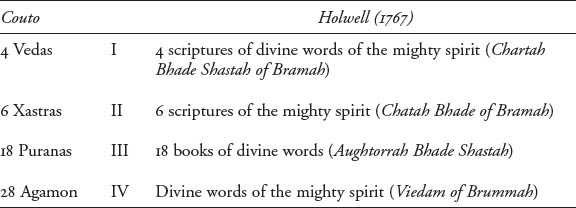

A further contradiction concerns the discrepancy between Holwell’s and the standard Indian view of Vedas and Shastras. To contemporaries like Voltaire or Anquetil-Duperron, Holwell’s presentation of sacred Indian literature—delivered purportedly in the words of learned Indian informers—seemed impressive. Holwell apparently set the beginning of the last world age (and thus the promulgation of Text I in Sanskrit) at 3100 B.C.E.,18 but nobody knows how he came up with a 1000-year golden age until Text II and another 500 years until Text III. The descriptions of the four corpora of Indian sacred scriptures by Holwell’s “learned Bramins” seem to stem, in spite of their 329 quotation marks, from a non-Indian source since Indians of all stripes always regarded the four Vedas as their basic sacred scriptures and Shastras as commentarial literature.19 This is also what European reports since the sixteenth century had affirmed (Caland 1918), and it is why Abbé Bignon urged Father Calmette to acquire and send the four Vedas to Paris and not some Shastras. So where did Holwell get this idea that the Vedas are late and degenerated scriptures, a mere shadow of the far older Shastah of Bramah?

Holwell boasted that he had “studiously perused all that has been written of the empire of Indostan, both as to its ancient, as well as more modern state” but added that what he had read was “all very defective, fallacious, and unsatisfactory to an inquisitive searcher after truth” (Holwell 1765:1.5). However, in the meantime we may have learned not to take every word of Holwell as gospel. He occasionally cited Ramsay’s Travels of Cyrus, which contained an interesting passage about Indian religion that could not fail to inspire him. Ramsay reported that the Veda states

that souls are eternal emanations from the divine Essence, or at least that they were produced long before the formation of the world; that they were originally in a state of purity, but having sinned, were thrown down into the bodies of men, or of beasts, according to their respective demerits; so that the body, where the soul resides, is a sort of dungeon or prison. (Ramsay 1814:382)

Ramsay attributed this passage to Abraham Roger’s De Open-Deure tot het verborgen Heydendom (The Open Door to the Hidden Paganism), whose French translation (1670) he had consulted. In the preface to that edition, translator Thomas La Grue particularly emphasized “what was also clearly a motif with Roger himself: that the Indians did indeed possess a pristine and natural knowledge of God, but that it had decayed almost completely into superstition as a result of moral lapses” (Halbfass 1990:46–47). But Holwell, a good reader of Dutch, could consult Roger’s original edition of 1651.20 There Roger called the Indian Dewetaes (Skt. devatas; Indian guardian spirits or protective divinities) “Engelen” or angels (Roger 1915:108). But here we are primarily interested in Roger’s description of the Vedam, which for him is the Indian’s book of laws containing “everything that they must believe as well as all the ceremonies they must perform” (p. 20).

This Vedam consists of four parts; the first part is called Roggowedam; the second Issourewedam; the third Samawedam; and the fourth Adderawanawedam. The first part deals with the first cause, the materia prima [eerste materie], the angels, the souls, the recompense of good and punishment of evil, the generation of creatures and their corruption, the nature of sin, how it can be absolved, how this can be achieved, and to what end. (p. 21)

After a brief explanation of the content of the second to fourth Vedas, Roger states that conflicts of Vedic interpretation generated a literature of commentaries called Iastra (Skt. śāstra), “that is, the explanations about the Vedam” (p. 22). As Willem Caland has shown in detail (1918),21 Roger’s source for such information was Diogo do Couto’s Decada Quinta da Asia of 1612. Couto’s account of the content of the Vedas was in turn, as Schurhammer (1977:2.612–20) proved, plagiarized from an account by the Augustinian brother Agostinho de Azevedo’s Estado da India e aonde tem o seu principio of 1603, a report prepared in the 1580s for King Philip III of Portugal, which “includes an original summary of Hindu religion, from Shaiva Sanskrit and Tamil texts” (Rubiés 2000:315). The question as to what exactly Azevedo’s sources were still awaits clarification in spite of Caland’s speculations (1918:309–10); but here we will concentrate on Couto whose report about sacred Indian literature, unlike Azevedo’s, was used by Holwell who could handle Portuguese. Couto’s report of 1612 describes Indian sacred literature as follows:

TABLE 11. DO COUTO’S VEDAS AND HOLWELL’S SACRED SCRIPTURES OF INDIA

They possess many books in their Latin, which they call Geredaom, and which contain everything they have to believe and all ceremonies they have to perform. These books are divided in bodies, members, and articulations. The fundamental texts are those they call Vedas which form four parts, and these again form fifty-two in the following manner: Six that they call Xastra which are the bodies; eighteen they call Purana which are the members; and twenty-eight called Agamon which are the articulations. (Couto 1612:125r)

The numbers four, six, and eighteen first made me think that Holwell’s weird history of Indian sacred literature might be modeled on Couto’s report. As we have seen, Holwell also mentioned four textual bodies. The number of scriptures of the first three bodies thus correspond exactly to Couto’s, as shown in Table 11.