François Marie Arouet—better known as VOLTAIRE (1694–1778)—was a superstar in eighteenth-century Europe and for a time one of its most read and translated authors. His plays were performed across the continent, and his view of world history was so influential that the Russian Czar, upon reading Voltaire’s Essai sur les moeurs, sent an embassy to China to verify some of its claims. This chapter will highlight a little known side of this multifaceted man. Though current histories of Orientalism barely mention him,1 Voltaire played an important role in the genesis of modern Orientalism. Since some of Voltaire’s sources and his particular approach are deeply connected with the missionary discovery of Asian religions and mission literature, relevant facets of this missionary basis will first have to be examined in some detail. In Voltaire’s time, much of Asia was still called “the East Indies,” and the focus of previous scholarly discussion on India proper and on religions that are today associated with the Indian subcontinent must be widened in order to understand eighteenth-century views and images. The influence and staying power of old ideas have hitherto been underestimated. Not just the study of the Orient in Voltaire’s time but even modern Orientalism is shaped by earlier impressions and approaches in profound and sometimes pernicious ways. It is a mistake to regard—in the manner of Schwab (1950), de Jong (1987), and many others—the onset of modern Orientalism as a clean break from a “nonscientific” past. As the examples of William Jones (App 2009) and Anquetil-Duperron (see Chapter 7) show, the pioneers of modern Orientalism raised the curtains and set a new stage; but much of the stage set seems recycled from earlier productions, and many actors in this play wear costumes of the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries while expressing ideas that fit those times. The lack of appreciation regarding some of the crucial underpinnings of Voltaire’s venture—particularly of missionary approaches and sources—gave rise to misunderstandings not only concerning his use of India-related sources but also the role he played in the genesis of modern Orientalism. Hence, the first task will be to discuss in some detail a number of facets of the missionary discovery of Asian religions that came to influence Voltaire’s views and sources.

Partly due to the summary dismissal of missionary portrayals of Asian religions as biased, some of the basic events of the missionary discovery of these religions are still ignored even by today’s Orientalists. It is, for example, a fact that the first systematic exploration of non-Islamic Asian religions happened not in India or some other land at a manageable distance from continental Europe but at the very end of the world as it was known at the time, namely, in sixteenth-century Japan. From the beginning of the sixteenth century, Catholic missionaries had settled in India and subsequently in various parts of Southeast Asia; but these were regions where even knowledge of the local vernacular did not yet entail access to sacred literature. Besides, the heathen cults were regarded as works of the devil to be exterminated rather than studied. In Japan, by contrast, the need for study arose from the fiasco of St. Francis Xavier’s Jesuit mission.2 FRANCIS XAVIER (1506–1552) and his Jesuit companions had arrived in the summer of 1549 in Japan with high hopes and accompanied by Anjirō, a Japanese man of modest education who served as their interpreter. He had translated “God” as “Dainichi” (the Sun-Buddha, the principal Buddha venerated by the Shingon sect of Buddhism), “heaven” and “paradise” as jōdo (the Pure Land of Buddhism), and “Christianity” as buppō (the Buddha dharma or Buddhist law); consequently, the Japanese were convinced that the Jesuits were Buddhist sectarian reformers from India. They had indeed come to Japan from Goa in India, and the Japanese (whose world at the time ended in India alias “Tenjiku”) consistently called Xavier and his companions “Indians” (“Tenjiku’s” or “Tenjikujin”) (App 1997a:55–58). The Japanese Shingon priests were so delighted with their new cousins from India that the Jesuits became suspicious; but even after Francis Xavier’s departure toward the end of 1551, the missionaries were still viewed as a bunch of zealous Buddhist sectarians. The document that supposedly proves their most notable success, the donation of a “church” (in reality, a Buddhist monastery) by the regent of Yamaguchi, became an object of widespread interest in Europe as it was printed in various letter collections all over the continent and became the first document in Chinese characters to be printed in Europe (Schurhammer 1928:26–27; App 1997b:236). The confrontation of the crucial portion of the published Portuguese rendering with my translation of the original Japanese text in Table 1 illustrates the heart of the problem: the Japanese regarded the missionaries as Buddhist bonzes intent on promulgating the Buddha dharma, whereas the Jesuit missionaries believed that the donation of a Buddhist temple signaled acceptance of their stated aim of producing Christian saints.3

TABLE 1. EDICT OF THE DUKE OF YAMAGUCHI TRANSLATED FROM JAPANESE AND PORTUGUESE

English translation of Japanese text (actual content of edict) |

Translation of published Portuguese text (how missionaries translated edict) |

The bonzesa who have come here from the Western regions may, for the purpose of promulgating the Buddhist law, establish their monastic community [at the Buddhist monastery of the Great Way]. |

[The Duke] accords the great Dai, Way of Heaven, to the fathers of the occident who have come to preach the law that produces Saints in conformity with their wish until the end of the world. |

a The term “bonze” (from Jap. bōzu) has been in use since the sixteenth century for Buddhist priests or monks (originally of Japan or China, but later increasingly as a generic term). In this book we will also encounter such equivalents as “heshang” for China, “lama” for Tibet, and “talapoin” for Southeast Asia.

Only in 1551, when Francis Xavier was getting ready to leave Japan in order to convert the Chinese, did the missionaries begin to use the word “Deus” instead of “Dainichi” (App 1997b:241–42). Their fiasco triggered a “language reform” that consisted in figuring out which terms were Buddhist, what they signified, and which were safe for use in a Christian context. This could only be achieved by some degree of systematic study and with the help of native informers familiar with Buddhist doctrine and texts. By 1556, eight years after the beginning of the Japan mission, the first report about the country’s religions was sent via Goa to Europe, where it arrived in 1558 (Bourdon 1993:261).4 This Sumario de los errores (Summary of Errors) contained a first survey of Japanese religions including Shinto and listed eight sects of Japanese Buddhism. They were all identified as belonging to “bupō” (Buddha dharma) and associated with a founder called Shaka (Shakyamuni Buddha) (Ruiz-de-Medina 1990:655–67). The Sumario also furnished information about the clergies of these sects, the texts they used, and some of their doctrines including a topic that was to have extraordinary repercussions well into Voltaire’s time: the distinction between two significations of Buddhist doctrines, an exoteric or outer one for the simple-minded people and an esoteric or inner one for the philosophers and literati (pp. 666–67). The esoteric teaching, which was associated with Zen Buddhism and its use of meditation and kōans, was said to lead to the realization that there is nothing beyond life and death and that “all is nothing” (p. 666). This is an early seed of the European misconception of an esoteric “cult of nothingness”5 with a secret teaching that later turned into the legend about the Buddha’s deathbed confession (see Chapter 3).

When the Jesuit Alessandro VALIGNANO (1539–1606) visited Japan for the first time between 1579 and 1582, he quickly realized that the study of the native language and religions was of paramount importance. He reported, “The first thing that I addressed and ordered after arriving in Japan . . . was that the European brothers study [the language] with great care and that a grammar and vocabulary of Japanese be produced” (Schütte 1951:321). Valignano promoted the admission of Japanese novices and, helped by P. Luis Frois who translated his words into Japanese, in 1580–81 held a course of intensive instruction for both European and Japanese novices (Schütte 1958:84–85). One of Valignano’s eight new novices, the middle-aged Japanese doctor Paulo Yōhō, was knowledgeable about Japanese religions and provided information about Buddhism to both Valignano and the novices. Together with his son Vicente Tōin, Paulo helped Valignano craft a catechism whose overall structure interests us here. Since Valignano had studied Francis Xavier’s fiasco and realized the importance of clearly separating truth from error, he decided to write a catechism and devote the first of its two books to the sects and religions of the Japanese in order to build a firm basis for their refutation through rational argumentation (Valignano 1586:3–76). It is a detailed presentation and critique of (mostly Buddhist) Japanese religious doctrine and shows how much knowledge the Jesuits had accumulated since the days of Francis Xavier. The catechism’s second book then treats of Christian life and its basis in the Ten Commandments and other doctrines.

An interesting and influential observation that Valignano made at the beginning of the first part was that, in spite of the multitude of sects in Japan and the confusing doctrines of Buddhism, there was a key that facilitated understanding all of them. This key was the distinction between an “outer” or provisional teaching for the common people (Jap. gonkyō) and the “inner” or true teaching for the clergy (Jap. jikkyō) (p. 4v).6 Valignano’s entire presentation of doctrines and sects is based on this “gon-jitsu” distinction, which he, of course, decries as “fallacious, mendacious, and deceptive” (fallax, mendax, hominum deceptrix) (p. 34v).

Without going into more detail, we note that this catechism is proof that Buddhism was already quite intensively studied by Westerners in the sixteenth century with the help of native experts. For his reform of the Jesuit Japan mission, Valignano even researched and copied some features of the organizational structure of Zen monasteries. Such study continued in the following decades until the expulsion of all missionaries from Japan in the early seventeenth century, and among its major fruits was a Japanese-Portuguese dictionary with about 32,000 entries (Vocabulario da Lingoa de Iapam, 1603; Jap. Nippo jisho). In this dictionary, all Buddhist terms are identified by the marker “Bup,” for buppō (Buddhism)—which proves how aware the missionaries were of Buddhism’s identity as a religion. This dictionary alone should lay forever to rest all claims that Buddhism was not perceived as a religion by Westerners before the nineteenth century. It is easy, however, to overestimate the influence of such mission documents since many of them soon ended up in dusty mission archives. While reports such as the Sumario de los errores got relatively little public exposure, Valignano’s catechism enjoyed the opposite fate. Its first edition, printed in Lisbon in 1586, is exceedingly rare, but the work was included almost unchanged in Antonio Possevino’s Bibliotheca selecta of 1593, a major textbook for generations of Jesuits and for Europe’s educated class (Possevino 1593:459–529; Mühlberger 2001:137–38). At the time, this was just about the most powerful megaphone anyone could wish for, and all the Jesuit protagonists in this chapter heard the message.

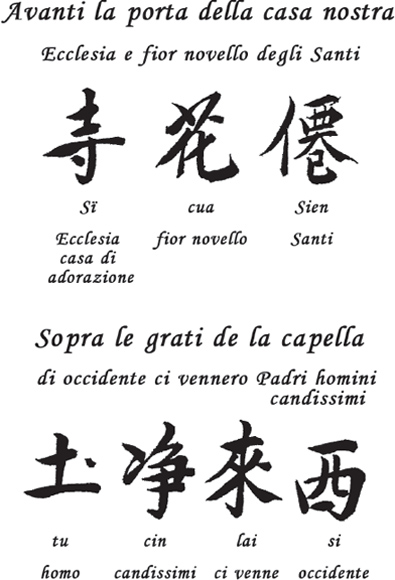

When Matteo RICCI (1552–1610) arrived in China in the summer of 1582 and began to learn Chinese, he benefited from a special introduction to Asian religions since Valignano, who was also in Macao at the time, made him copy the conclusions (“Risolutioni”) that he had drawn from his three-year stay in Japan (Schütte 1958:63). But when Ricci in the same year moved with another Italian missionary, Michele Ruggieri,7 to Canton and then to Zhaoqing in South China, history seemed to repeat itself with a vengeance: the two Jesuits adopted the title and vestments of the Chinese seng—that is, they identified themselves and dressed as ordained Buddhist bonzes. Even their Ten Commandments in Chinese contained Buddhist terms; for example, the third commandment read that on holidays it was forbidden to work and one had to go to the Buddhist temple (si) in order to recite the sutras (jing) and worship the Master of Heaven (tianzhu, the Lord of devas).8 Ruggieri’s and Ricci’s first Chinese catechism, the Tianzhu shilu of 1584—the first book printed by Europeans in China—also brimmed with Buddhist terms and was signed by “the bonzes from India” (tianzhuguo seng) (Ricci 1942:198). The doorplate of the Jesuit’s residence and church read “Hermit-flower [Buddhist] temple” (xianhuasi), while the plate displayed prominently inside the church read “Pure Land of the West” (xilai jingdu).9 As can be seen in the report about the inscriptions on the Jesuit residence and church of Zhaoqing (Figure 1),10 Ruggieri translated “hermit” (xian), a term with Daoist connotations, by the Italian “santi” (saints), and the Buddhist temple (si) became an “ecclesia” (church). Even more interesting is his transformation of the Buddhist paradise or “Pure Land of the West” into “from the West came the purest fathers.”11 This presumably referred to the biblical patriarchs, but it is not excluded that a double-entrendre (Jesuit fathers from the West) was intended.

Nine years later, in 1592, when Ricci was translating the four Confucian classics, he decided to abandon his identity as a Buddhist bonze (seng); and during a visit in Macao, he asked his superior Valignano for permission also to shed his bonze’s robe, begging bowl, and sutra recitation implements. The Christian churches were renamed from si to tang (a more neutral word meaning “hall”), and in 1594 the final step in this rebranding process was taken when Ricci received Valignano’s permission to present himself and dress up as a Chinese literatus (Duteil 1994:85–86). It was the year when Ricci finished his translation of the four Confucian classics, the books that any Chinese wishing to reach the higher ranks of society had to study. In Ricci’s view, these books contained unmistakable vestiges of ancient monotheism. In his journals he wrote,

Of all the pagan sects known to Europe, I know of no people who fell into fewer errors in the early stages of their antiquity than did the Chinese. From the very beginning of their history it is recorded in their writings that they recognized and worshipped one supreme being whom they called the King of Heaven, or designated by some other name indicating his rule over heaven and earth. . . . They also taught that the light of reason came from heaven and that the dictates of reason should be hearkened to in every human action. (Gallagher 1953:93)

Figure 1. Inscriptions for the Jesuit residence and church in Zhaoqing, 1584.

The Jesuit language reform in China took a different direction from the earlier one in Japan; instead of intensively studying the Buddhist and Daoist competition in order to defeat it, Ricci and his companions focused on cozying up to the Confucians. On November 4, 1595, Ricci wrote to the Jesuit Father General Acquaviva: “I have noted down many terms and phrases [of the Chinese classics] in harmony with our faith, for instance, ‘the unity of God,’ ‘the immortality of the soul,’ the glory of the blessed,’ and the like’’ (Ricci 1985:14). Ricci intended to identify appropriate terms in the Confucian classics to give the Christian dogma a Mandarin dress and to illustrate his view that the Chinese had successfully safeguarded an extremely ancient knowledge of God. The portions of Ruggieri and Ricci’s old “Buddhist” catechism dealing with God’s revelation and requiring faith rather than reason were removed, while topics such as the “goodness of human nature” that appealed to Confucians were added (p. 15). Ricci systematically substituted Buddhist terminology with phrases from the Chinese classics. But rather than as a revision of his earlier “Buddhist” catechism, Ricci’s True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven should be regarded as a new work reflecting his view of China’s ancient theology. It was crafted in the mold of the first part of Valignano’s catechism of 1586, and exactly ten years after the publication of that work, Ricci’s supervisor Valignano examined and approved Ricci’s new text for use in China. It was not a catechism in the traditional sense but a praeparatio evangelica: a way to entice the rationalist upper crust of Chinese society and to refute the “superstitious” and “foreign” forms of Chinese religion (such as Daoism and Buddhism) by logical argument while interpreting “original” Confucianism as a kind of Old Testament to Christianity. Ricci’s “catechism” was thus not yet the Good News itself but a first step toward it. It argued that Chinese religion had once been thoroughly monotheistic and that this primeval monotheism had later degenerated through the influence of Daoism and Buddhism. In Ricci’s view Christianity was nothing other than the fulfillment of China’s Ur-monotheism.

Ricci decided to cast this preparatory treatise in Renaissance fashion as a dialogue between a Western and a Chinese scholar who discuss various aspects of Chinese religion. Ricci’s Western scholar analyzes Daoist, Buddhist, and Neoconfucianist beliefs and practices and proceeds to demolish them by rational argument, thus exposing their inconsistency and irrationality. When Ricci’s work was completed and his new manuscript began to circulate in preparation for the printing, the old “Buddhist” catechism was no longer used.

When the first copies of Ricci’s True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven arrived in Japan, one of Valignano’s erstwhile novices, João RODRIGUES (1561–1633), studied it with much interest. Having arrived in Japan in 1577 at the young age of 16, he had at the turn of the seventeenth century already spent a quarter-century in the Far East and had become the best foreign speaker, reader, and writer of Japanese in the Jesuit mission. He had become not only procurator of the Japan mission but also court interpreter for Japan’s autocratic ruler Tokugawa Ieyasu. When Valignano left Japan for the last time in 1603, Rodrigues was just putting the finishing touches on his remarkable Japanese grammar Arte da Lingoa de Iapam, which was first printed in 1604 (Cooper 1994:228). Like any educated Japanese of the time, Rodrigues had also studied classical Chinese and sprinkled his grammar with examples from Confucius’s Analects. The depth of his knowledge of Japanese language and religion is apparent in his advice on letter writing style, which includes an introduction to the various kinds and degrees of Buddhist clergy and the correct ways of addressing them (Rodrigues 1604:199r–201r). His grammar also features a masterly treatise on Japanese poetry that is “the first comprehensive description of Far Eastern literature by any European” and includes a section on the translation of Chinese poetry into Japanese (Cooper 1994:229–30). Rodrigues was very much interested in the origins of Asian religions and peoples, and for this a firm grasp of chronology was needed. The third part of his grammar (Rodrigues 1604:232v–239r) contains Rodrigues’s chronological tables based on both Western and Far-Eastern sources.12 In the section on Chinese chronology, Rodrigues made the first known attempt to relate Japanese, Chinese, and Western chronologies. His aim was to position the founders of China’s three major religions (Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism) in the framework of biblical history and its accepted chronological sequence (pp. 235r–236r).

After being forced out of Japan in 1610, he spent the rest of his life in China. He thus lived a total of thirty-three years in Japan and twenty-three in China. Even though his name is seldom if ever mentioned in books about the discovery of Oriental religions, it is clear that, during his fifty-six years in Asia, he became by far the most knowledgeable Westerner of his time about the religions of Japan and China. Even in his late teens, he had the chance of participating in Valignano’s lecture series leading to the 1586 catechism and was instructed by Japanese experts on Buddhism.13 When Ricci’s Chinese books made their way to Japan, Rodrigues thus was one of the few people capable of studying and criticizing them.14 He noticed a number of “grave things”:

These things arose on account of the lack of knowledge at that time and the Fathers’ ways of speaking and the conformity (as in their ignorance they saw it) of our holy religion with the literati sect, which is diabolical and intrinsically atheistic, and also contains fundamental and essential errors against the faith. (Cooper 1981:277)

Rodrigues’s early doubts about Ricci’s view of Confucianism as a vestige of primeval monotheism were reinforced when he spent two entire years (June 1613–June 1615) traveling in China “deeply investigating all these sects, which I had already diligently studied in Japan” (p. 314). His “three sects of philosophers” are Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, which Rodrigues not only studied in books but also through extensive field research: “To this end I passed through most of China and visited all our houses and residences, as well as many other places where our men had never been so far” (p. 314). The catechism that Rodrigues compiled (pp. 306, 315), a detailed atlas of Asia with tables of longitudes and distances (pp. 302–3), and a small report (p. 321) as well as a voluminous treatise (pp. 310, 277) about Far Eastern religions seem to be lost. However, some of their content survived. Maps and other geographical materials by Rodrigues were used without attribution by his ambitious fellow Jesuit Martino Martini,15 and his reports about Asia’s religions formed a principal source of Niccolò Longobardi’s famous essay that was written in the early 1620s but published in 1701 at the height of the “Chinese Rites” controversy raging in Voltaire’s youth.16 A number of Rodrigues’s letters from China survived and are of considerable help in our reconstruction of the basic direction of his argument.

Contradicting Ricci, Rodrigues maintained that all reigning religions of China, including Confucianism, were fundamentally atheist and thus incompatible with Christianity. Influenced by what he had learned about the provisional (outer) and true (inner) teachings of Buddhism in Japan (the gonjitsu dichotomy underlying the first part of Valignano’s catechism), Rodrigues detected the same two types of doctrines in all China’s religions (pp. 311–12). According to Rodrigues, Ricci’s problems were a result of his failure to understand this fundamental distinction and of his ignorance about the inner teachings:

Until I entered China, our Fathers of China knew practically nothing about this [distinction between exoteric and esoteric teachings] and about the speculative doctrine. They knew only about the civil and popular doctrine, for there was nobody to explain it to them and enlighten them. The above-mentioned Fr. Matteo Ricci worked a great deal in this field and did what he could, but, for reasons only known to Our Lord, he was misled in this matter. All these three sects of China are totally atheistic in their speculative teaching, denying the providence of the world. They teach everlasting matter, or chaos, and like the doctrine of Melissus, they believe the universe to contain nothing but one substance. (pp. 311–12)

The disappearance of Rodrigues’s religion report is very likely due to his fierce opposition to a Ricci-style accommodation with Confucianism that was the central bone of contention in the controversy about Chinese Rites that filled so many book shelves from the mid-seventeenth century onward. The whole question of the acceptability of Confucian rites depended on Confucianism’s pedigree. If it could be traced to monotheism, as Ricci thought it could, then its ancient rites posed hardly a problem. But if Rodrigues was right and Confucianism’s inner doctrine was pure atheism (complete with eternity of matter, lack of a creator God, and absence of providence), then any rite connected to such a religion was to be condemned.

In his letters from China and some of his printed works, Rodrigues identified all three major religions of China as descendants of ancient heathen cults of the Middle East. While Ricci viewed Confucianism as a child of original monotheism and the Chinese literati as relatively free from heathen superstition prior to the influence of Daoism and Buddhism, Rodrigues envisioned a very different pedigree reaching back to Chaldean diviners:

There does not seem to be any other kingdom in the whole world that has so many [superstitions] as this kingdom [of China], for it appears that all the ancient superstitions that ever existed have gathered here, and even modern superstitions as well. The sect of Chaldean diviners flourishes here. The Jesuits call it here the Literati Sect of China. Like them it philosophizes with odd and even numbers up to ten and with hieroglyphic symbols and various mathematical figures, and with the principal Chaldean deities, Light and Darkness, and these two deities are called the Virtue of Heaven and the Evil of Earth. This sect has thrived in China for nearly four thousand years, and it seems to have originated from Babylon when those people came to populate this kingdom. (p. 239)17

Daoism, by contrast, was identified as “the sect of the Magicians and Persian evil wizards” that “seems to be a branch of the ancient Zoroaster” and Buddhism as “the sect of the ancient Indian gymnosophists” that spread all over Asia but had Egyptian roots since it professes “a part of the doctrine of the Egyptians” (p. 238). This may well be the earliest example of an Egyptian genealogy for Buddhism—an idea that had a great career in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (see Chapters 2, 3, and 4). For Rodrigues, all three Chinese religions thus had their roots in the Middle East: Confucianism in Mesopotamia, Daoism in Persia, and Buddhism in Egypt.

Since no one except Noah and his family had survived the great deluge, all three religions could not but have their ultimate origin with someone on the ark. The usual suspect was Ham, the son of Noah who had seen his father naked while drunk and whose son Canaan had been cursed by Noah (Genesis 9:25). According to Rodrigues, the Chinese people were descendants of Belus who “is the same as Nimrod, the grandson of Ham” who began to reign just after the confusion of tongues in Babel. The Chinese settled in their land after traveling “from the Tower of Babel straight after the Confusion of Tongues” and were “the first to develop . . . astrology and other mathematical arts and other liberal and mechanical arts” (Rodrigues 2001:355). Especially the “science of judicial astrology” that Chinese Confucians still practice “after the fashion of the Chaldeans with figures of odd and even numbers” was “spread throughout the world by Ham, son of Noah” (p. 356). All this led Rodrigues to the expected conclusion:

According to this and the other errors that they [the Chinese] have held since then concerning God, the creation of the universe, spiritual substances, and the soul of man, as well as inevitable fate, the Chinese seem to be descendants of Ham, because he held similar errors and taught them to his descendants, who then took them with them when they set off to populate the world. (p. 356)

But how did such knowledge reach China? As Noah’s descendants dispersed to populate the world after the Confusion of Tongues in Babylon, “the wiser families” according to Rodrigues took along such knowledge (and possibly also books) and proceeded to spread them throughout the world. In some places this knowledge was lost, but in others (like China) it was preserved (p. 378). If the transmission of genuine religion extended from God via Adam, Seth, and Enoch to Noah, how about the antediluvian transmission of false religion?

In addition to this astrological truth acquired through experience by the good sons of Seth, the wicked sons of Cain invented many conceits, innumerable superstitions, and errors. . . . they would commit many evil deeds and offences against God with the encouragement of the devil, to whom they had given themselves. For as it is written about him [Ham] and Cain, they were the first idolaters in the world and inventors of the magical arts. As he was evilly inclined, Ham, the son of Noah, was much given to this magical and judicial art, which he learnt from Cain’s descendants before the Flood. (p. 378)

While the Chinese had safeguarded some useful scientific knowledge and the use of writing (p. 331) from the good transmission and thus had possibly managed to develop the world’s earliest true writing system (p. 350), their religions, including Confucianism, unfortunately carried the strong imprint of Ham and the evil transmission. Rodrigues knew little about India, which he had only briefly visited on the way to Japan as a teenager. For him India’s naked philosophers or gymnosophists and the Brahmans were all “disciples of Shaka’s doctrine” (p. 360), and since Shaka (Shakyamuni Buddha) had “lived long before them,” it was from him that they had learned such mistaken doctrines as that of a multitude of worlds (p. 360)—one of the views, nota bene, that around this time (1600) landed Giordano Bruno on the stake. Rodrigues thus regarded all three religions of China as descendants of the Hamite line that ultimately goes back to Cain, the slayer of his brother Abel. Though Buddhism was transmitted via India and reached China later than Confucianism and Daoism, it had the same ultimate root and atheist core. As we will see in Chapter 3, Rodrigues’s vision of an underlying unity of Asian religions had a great future in the eighteenth century.

While Rodrigues fought against the ancient theology of Ricci and other Jesuits in China, a similar battle unfolded on the Indian subcontinent. In India, too, missionaries who were convinced that India’s ancient religion belonged to the evil transmission fought against colleagues who believed that India had once been strictly monotheistic. The latter saw it as a land of pure primeval monotheism that, alas, had in time become clouded by the fumes of Brahmanic superstition.18 The most famous Jesuit in India to hold the latter view was Roberto DE NOBILI (1577–1656), who was later falsely accused of having authored Voltaire’s Ezour-vedam. The real authors of the Ezourvedam, French Jesuit missionaries in India,19 were also partisans of Indian Urmonotheism—and so was their contemporary and critic in France, Voltaire.

One of Voltaire’s favorite teachers at the Jesuit college Louis-le-Grand in Paris was Father René Joseph DE TOURNEMINE (1661–1739), the chief editor of the journal Mémoires de Trévoux. Father Tournemine had been involved in the controversy about the Chinese Rites that culminated in 1700 with the banning of several books on China at the Sorbonne. This so-called Querelle des rites had been accompanied by the publication of reams of pamphlets and books and is a striking example of public attention to oriental issues in Voltaire’s youth and of their impact on the established religion in Europe (Étiemble 1966; Pinot 1971; Cummins 1993).

On the losing side of the rites controversy, which came to a peak one century after Ricci in Voltaire’s school years, were those who agreed with his idea that the ancient Chinese had from remote antiquity venerated God and abandoned pure monotheism only much later under the influence of Persian magic (Daoism) and Indian idolatry (Buddhism). They liked to evoke Ricci’s statement about having read with his own eyes in Chinese books that the ancient Chinese had worshipped a single supreme God. In order to explain how this pure ancient religion had degenerated into idolatry, they cited Ricci’s story about the dispatch in the year 65 C.E. of a Chinese embassy to the West in search of the true faith (Trigault 1617:120–21). Instead of bringing back the good news of Jesus, the story went, the Chinese ambassadors had stopped short on the way and returned infected with the idolatrous teachings of an Indian impostor called Fo (Buddha). In the following centuries, this doctrine had reportedly contaminated the whole of East Asia and turned people away from original monotheism. Since Ricci’s story20 was told in one of the seventeenth century’s most widely translated and read books about Asia, Nicolas Trigault’s edition of Ricci’s History of the Christian Expedition to the Kingdom of China (first published in Latin in 1615), it had an enormous influence on the European perception of Asia’s religious history.

Ricci’s extremist successors, the so-called Jesuit figurists (see Chapter 5), sought to locate the ancient monotheistic creed of the Chinese not just in Confucian texts but also in the Daoist Daodejing (Book of the Way and Its Power) and of course in the book that some believed to be the oldest extant book of the world, the Yijing (or I-ching; Book of Changes). These figurists included the French China missionaries Joachim Bouvet (1656–1730), the correspondent of Leibniz, and younger Jesuit colleagues like Joseph-Henri Prémare (1666–1736) and Jean-Francois Foucquet (1665–1741), the man to whom Voltaire later falsely attributed the translation of his own “Chinese catechism.”21 The Jesuits of the Ricci camp thought that since genuine monotheism had existed in a relatively pure state at least until the time of Confucius, their role as missionaries essentially consisted in reawakening the old faith, documenting its “prophecies” regarding Christ, identifying its goal and fulfillment as Christianity, and eradicating the causes of religious degeneration such as idolatry, magic, and superstition. Ritual vestiges of ancient monotheism were naturally exempted from the purge and subject to “accommodation.”

By contrast, the extremists in the victorious opposite camp of the Chinese Rites controversy held that—regardless of possible vestiges of monotheism and prediluvian science—divine revelation came exclusively through the channels of Abraham and Moses, that is, the Hebrew tradition, and was fulfilled in Christianity. This meant that the Old and New Testaments were the sole genuine records of divine revelation and that all unconnected rites and practices were to be condemned. From this exclusivist perspective, the sacred scriptures of other nations could only contain fragments of divine wisdom if they had either plagiarized Judeo-Christian texts or aped their teachers and doctrines.

But China was not the only country whose religious pedigree was questioned. As early as the Renaissance, Marsilio Ficino (1433–99) had pored over the texts attributed to Hermes Trismegistos and oracular texts reputed to contain vestiges of pre-Judaic monotheism. In those days the focus of interest was mostly on Egypt, which (at least in heathen circles) had long been regarded as the cradle of humankind. After the discovery of the Americas (“West Indies”) (1492) and the exploration of the “East Indies” following Vasco da Gama’s circumnavigation of Africa and arrival in India (1498), the possibility of finding pre-Mosaic texts containing vestiges of God’s revelation in other civilized regions had to be considered seriously. Following the lead of Epiphanius, who had first identified the Brahmans as descendants of Abraham and Keturah (Paulinus a Sancto Bartholomaeo 1797:63), Guillaume Postel (1510–81) speculated in his interesting book De originibus (On the Origins) that the Indian Brahmans (“Abrahmanes”) are direct descendants of Abraham (Postel 1553b:68–69). Postel was the first to suggest that India might harbor extremely ancient scriptures that could finally bring “absolute clarity” to the Mosaic narrative (p. 72). He thought that India was a land in which “infinite treasures of history and antediluvian books are hidden” and surmised that Enoch’s books could be found there (p. 72). Though his idea was not exactly orthodox, Postel clearly stayed within the biblical framework since Enoch is one of the antediluvian heroes praised in the Bible and revered in Christianity as a pre-Judaic “pagan saint.”22 However, the emphasis on antediluvian texts by Enoch and possibly even older figures such as Seth, the good son of Adam, could also be interpreted as an attack on Mosaic authority and the Old Testament. At any rate, Postel postulated two Abrahamic transmissions: a familiar one in the Middle East and an alternative one to the “sons of the Orient” (p. 64) who were none other than the Indian Brahmans. Though it remained unclear what texts and doctrines this oriental lineage of Abraham had actually transmitted or produced, the tantalizing possibility remained in the air that a kind of alternative (and possibly more ancient) Old Testament could exist in India.

Postel’s Abrahamic Brahmans soon became the object of criticism, for example, in Henry Lord’s A Discoverie of the Sect of the Banians, which asserted that the Indians had never heard of Abraham (Lord 1630:71–72). Despite the criticism, in Voltaire’s time there were still supporters of this rather effective way of incorporating the Indians (and other Asians linked to them) into the biblical lineage. One of them was Isaac Newton,23 who wrote in his famous Chronology that was studied by Voltaire,

This religion of the Persian empire was composed partly of the institutions of the Chaldaeans, in which Zoroastres was well skilled, and partly of the institutions of the ancient Brachmans; who are supposed to derive even their name from the Abrahamans, or sons of Abraham, born of his second wife Keturah, instructed by their father in the worship of ONE GOD without images, and sent into the east, where Hystaspes was instructed by their successors. (Newton 1964:5.247)

Another supporter of Postel’s hypothesis was the Jesuit Jean Venant BOUCHET (1655–1732), one of the major contributors to the large collection of Jesuit mission letters entitled Lettres édifiantes et curieuses, which was required reading for men like Voltaire, Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron, Constantin-François Volney, William Jones, and anyone interested in Asia and its religions. The India part of this collection contains a total of nine letters by Bouchet. By far the most famous and influential ones are those to the bishop of Avranches, Pierre-Daniel Huët (1630–1721). Huët’s Demonstratio evangelica of 1678 attempted to prove the unbeatable antiquity of the Old Testament by asserting that all pagan gods derive from Moses (and occasionally other Hebrew patriarchs) or from Moses’s wife or sister. D. P. Walker (1972:216) wrote of being “lulled into a coma by the monotony of ‘Vulcanus idem ac Moses. Typhon idem ac Moses . . . Zoroastres idem ac Moses . . . Apollo idem ac Moses. Pan idem ac Moses . . .’.”24 Huët’s purpose was not the coma of his readers but the fortification of his (and some readers’) wobbling faith in the trustworthiness of Moses. The onslaught could not be ignored: there were, of course, Isaac La Peyrère (1596–1676) with his theory of pre-Adamites (1655) and Baruch de Spinoza (1632–77) with his Tractatus theologico-politicus (1670), who both attacked the Old Testament’s value as a textual source. But hardly less dangerous were assertions by the likes of Martino MARTINI (1614–1661), the Jesuit missionary who shocked Europe by his report that Chinese historical records reached back to antediluvian times (Martini 1658; Collani 2000). Huët’s herculean effort had filled his house with so many books that it ended up collapsing, and Bouchet’s letters from India may have been designed to prevent Huët’s precarious faith (Walker 1972:219) from suffering the same fate. Additionally, these letters mark the onset of a gradual shift from interest in China—which had dominated the second half of the seventeenth century and the first decades of the eighteenth century—to the focus on India promoted by Voltaire that fed the orientalist revolution described in this book.

Voltaire’s Sermon des cinquante, the earliest print of which has been backdated to 1749,25 is something like a prayer book of a society of fifty “pious and reasonable learned people” who meet every Sunday, pray together, and then listen to a sermon before dining and collecting money for the poor. If one replaces “dining” by “breaking bread,” one immediately gets Voltaire’s point: this is the Sunday service of his religion for “reasonable learned people.” After the initial prayer to the one unborn and undying God who rewards good and punishes evil, the president of the society begins his sermon as follows:

My brothers, religion is the secret voice of God who speaks to all human beings; it must unite them all, not divide them. Thus any religion that belongs only to a single people is false. Ours is in principle the religion of the entire universe; because we venerate a Supreme Being, like all nations do; we practice the justice which all nations teach, and we reject all the lies that the peoples accuse each other of. In agreement with them about the principle that unites them, we differ from them with regard to everything that makes them fight. The point that unites all people of all times must necessarily be the unique core of truth, and the points in which they differ, the standards of lie: religion must be in accordance with morality, and it must be universal like morality. Thus any religion that offends morality is necessarily false. It is under this double perspective of perversity and falsity that in this discourse we will examine the books of the Hebrews and those who have succeeded to them. (Voltaire 1749:4–5)

This pamphlet is Voltaire’s deist manifesto, whose beginning already indicates that it entails a harsh indictment against Jewish and Christian exclusivism. It is an impassioned plea against the sects of Moses and Jesus and all their superstitions, divisions, hatred, persecutions, and brutality, and ends with a call to return to a pure, united religion:

Oh my brothers! can one commit such outrages against mankind? Have not our fathers already relieved the people from transsubstantiation, the veneration of creatures and bones of the dead, and from oral confession, indulgences, exorcisms, false miracles, and ridiculous images? Have not the people become accustomed to be deprived of such superstition? One must have the courage to take some further steps. The people are not as idiotic as one might think. They will easily accept a wise and simple cult of a unique God that, we are told, the sons of Noah professed and all the sages of antiquity practiced, as all scholars in China accept. (p. 26)

Voltaire was a convinced deist, and the deists’ creed was thoroughly inclusive: not just those born into a certain region or era or religion had received God’s revelation but all humankind. True religion thus had to be natural religion, that is, the religion that God had poured into the heart of every human being. For this religion, the concept of universal consent was crucial, as the beginning of Voltaire’s sermon shows: all nations and men belong to God’s axis of good. Voltaire was not only in search of a universal history but also of a universal religion; and as soon as he embarked on his quest for a universal history during the 1740s, he also began to examine the religions of the world, particularly those of ancient Asia. Thanks to the writings of Ricci and his successors, he found that in China a pure veneration of God without any superstition and accompanied by excellent morality had once existed. However, as in other countries, this initial purity had become adversely affected through priestcraft and “the superstition of the bonzes” (Pomeau 1995:158). Voltaire was not interested in a simple extension of the biblical narrative to other countries, as was the case with the figurists in China or Father Bouchet in India who sought a link to a “good” son of Noah. That would have been tantamount to letting the Jews and their exclusivist divinity continue monopolizing human origins. For him it was not a question of the transmission of exclusively revealed truths or of the plagiarism of sacred scriptures in the sole possession of one people. Voltaire’s eye was set on a true universal religion, a pure theism forming the root of all creeds. Already in a pamphlet of 1742 he had written,

Deism is a religion that is present in all religions; it is a metal that alloys with all others and whose veins run underground to the four corners of the world. This mine is more exposed, more dug in China; everywhere else it is hidden and the secret is only in the hands of the adepts. There is no land with more adepts than England. (p. 159)

One of these “adepts” was Edward HERBERT, Baron of Cherbury (c. 1600–1655), who had built his central argument on “universal consent,” that is, a common (monotheist) denominator to all religions of past and present. Voltaire thought that a pure, uncluttered monotheism suited to the taste of modern deists had existed in the remote past and that traces of it could be found in the most ancient cultures. Like his teacher Tournemine, Voltaire had with much interest studied the observations of Thomas HYDE (1636–1703) on the religion of Persia (1700) and found himself in agreement with the English scholar’s argument that monotheism had anciently existed everywhere and left vestiges in the form of texts, myths, and rituals far older than those of Judaism. Of course he was also interested in such vestiges because they offered a chance to undermine biblical authority and its monopoly on ancient history. Was God less intolerant, cruel, and vindictive in texts other than the Old Testament—texts that were potentially much older than the scribblings of Moses and far less offensive to a modern deist who believed in God’s universal revelation in the form of natural law for all rather than a secret communication to an individual or tribe?

Voltaire’s search for vestiges of ancient monotheism thus formed part and parcel of his quest for a universal history that began in earnest in the 1740s. “Universal histories” such as the pioneering work by Jacques-Bénigne BOSSUET (1627–1704) tended to begin with the creation of the world in 4004 B.C.E. (Bossuet 1681:7) and to feature events such as Enoch’s miraculous ascension in 3017 B.C.E. (pp. 8–9) and the universal deluge of 2348 B.C.E. For Bossuet, the time up to 1491 B.C.E., when Moses wrote down God’s law, was “the period of natural law [Loy de Nature] when people had only natural reason [la raison naturelle] and the traditions of their ancestors to govern themselves” (pp. 17–18). From Bossuet’s perspective, the histories and religions of all people were rooted in the events described in the Old Testament. Bossuet was well informed about the Chinese and had a hand in the campaign to condemn the Chinese Rites as idolatrous; indeed, it was through his offices that a “Letter to the Pope about the Chinese idolatries and superstitions” was printed (Hazard 1961:197). He was incensed that the Jesuits had dared to write of a “Chinese church” and thundered, “Strange kind of church without faith, without promise, without covenant, without sacraments, without the slightest sign of divine testimony. . . . After all, this is nothing but a confused pile of atheism, politics, irreligion, idolatry, magic, divination, and spells!” (p. 197). In the first edition of his universal history, Bossuet simply ignored this pile of refuse. But when he published the third edition of his history in 1700, at the height of the Chinese Rites controversy, he was forced to add alternative year numbers from the Septuagint version of the Old Testament. The Jesuit China missionaries had long made use of Septuagint chronology because it added 959 years to the world’s age and thus guaranteed that the starting shot of biblical history rang before that of the Chinese annals. Thus Bossuet’s pupil, the French royal heir apparent, and his numerous other readers needed to be informed that there was a second biblically supported date for the world’s creation, namely, 4963 B.C.E. Bossuet’s twelve epochs of world history, which so beautifully show his biblical and Mediterranean bias (1. creation; 2. deluge; 3. Abraham; 4. Moses; 5. Troy; 6. Salomo; 7. Romulus and Rome; 8. Cyrus; 9. Scipio and Carthago; 10. Jesus; 11. Constantine; 12. Charlemagne), thus all received a second, alternative date. As Kaegi (1938:82) aptly put it, these double numbers exposed “a small crack in the royal edifice that within a few decades deepened and eventually led to its collapse.” But Bossuet’s universal history was not the only one that featured a staunchly biblical narrative of origins. Even some more recent works such as the gigantic English An Universal History from the Earliest Accounts to the Present whose publication began in 1730 featured chapters titled “From the Creation to the Flood” and “From the Deluge to the Birth of Abraham” (Sale et al. 1747:1.1–153).

When Voltaire in the early 1740s set out to write his Essai sur les moeurs et l’esprit des nations et sur les principaux faits de l’histoire depuis Charlemagne jusqu’à Louis XIII (which in the following will simply be called Essai), he intended not to supplant Bossuet’s history but rather to supplement it; but it irked him no end that a few rather insignificant nations around the Mediterranean Sea had hijacked the early history of humankind. In the introduction to the first fragments for his new beginning of universal history, Voltaire wrote,

Until now, the majority of Universal Histories treated other peoples as if they did not exist at all. Greece and the Romans have seized all of our attention, and when the famous Bossuet says a word about the Mohammedans, he speaks of them only as an inundation of barbarians, even though many of these nations possessed useful arts that we inherited from them. . . . We are neither just nor wise to ignore them. (Voltaire 1745:8)

While getting ready to remedy this state of affairs, Voltaire wanted to collect what his predecessors had neglected (p. 5) in order to furnish a truly universal history of “the customs of man and the revolutions of the human spirit” (p. 5). The first draft chapters of this new history dealt not with Adam and creation but with China and India, which pointed to a looming revolution in Europe’s perception of origins. Voltaire’s central and most influential work is without any doubt the Essai. With regard to his view of Asian religions and to the development of his vision of India and its religions, the Essai is most interesting because its different editions reflect different stages of Voltaire’s outlook. We will thus focus on this central text of Voltaire and adduce other works as needed. Table 2 lists the stages of the Essai’s genesis with brief remarks about the relevance for our inquiry.

TABLE 2. VOLTAIRE’S ESSAI SUR LES MOEURS AND ASIAN RELIGIONS

1745 |

The 1745 fragments (later used in the Essai) published in the Mercure de France contain an introduction and the first two chapters on China and India which reflect Voltaire’s early view of Asian religions and literature. |

1756 |

The first edition of the Essai sur les moeurs contains many changes and additions to the 1745 texts on China and India reflecting Voltaire’s intensive study of missionary and travel literature before his encounter with the Ezour-vedam. Apart from the China and India chapters, ch. 120 on Japan contains information about Voltaire’s view of India and its sacred literature. |

1761 |

The second edition of the Essai sur les moeurs reflects Voltaire’s study of the Ezour-vedam and contains—apart from a new chapter on the Brahmans, the Veda, and the Ezour-vedam—also many interesting revisions and additions. The Indies part of the Japan chapter now forms a separate chapter (ch. 139) and contains some revisions and additions. |

1765 |

Voltaire’s La philosophie de l’histoire (published separately under the pseudonym of Abbé Bazin but in 1769 incorporated into the Essai sur les moeurs) contains Voltaire’s views on the early history of religion and contains a chapter on “Bram, Abram, Abraham” and one each on India and China. (Voltaire’s 1767 La défense de mon oncle is a defense against a critic of the La philosophie de l’histoire and, besides adding some relevant information, represents the apex of Ezour-vedam influence) |

1769 |

The third edition of the Essai sur les moeurs newly features the 1765 La philosophie de l’histoire as Introduction to the Essai. The Essai itself also contains numerous passages reflecting Voltaire’s study of Holwell’s Interesting historical events and its fragments of the Chartah Bhade. |

1775 |

For collective editions of his works, Voltaire revised his Essai text three more times and added some polemics (Pomeau 1963:xviii); these revisions are of little importance to our inquiry. |

Voltaire’s admiration of India is often described in the context of his purported shift from a similar but earlier admiration of China. In the eyes of Wilhelm Halbfass, this transition from infatuation with China to indomania happened in 1760 on contact with the Ezour-vedam:

China at first appeared much more attractive and important than India in Voltaire’s eyes, and he played an active role in helping to idealize the “practical philosophy” and civic institutions of the Chinese. However, after studying the manuscript of the Ezourvedam which the Chevalier de Maudave had given him in 1760, he became convinced that the world’s oldest culture and most pristine religious thought was to be found in India and not in China. (Halbfass 1990:57)

However, Daniel Hawley detected some admiration for India already in the 1756 version of Voltaire’s Essai. But in support of his thesis that until the encounter with the Ezour-vedam Voltaire’s India was the “exotic India” of Bababec and the Fakirs (1750), Hawley states that “before 1756 the majority of references to India in the Essai were no more than exotic details” (1974:166). A closer look at Voltaire’s 1745 Essai chapters on China and India, however, results in a completely different picture.

Since Voltaire took the revolutionary step of beginning his universal history not with the creation story and Adam but rather with a chapter on China, questions of chronology were of great importance. Voltaire used information furnished by the learned Father Antoine Gaubil of the Jesuit China mission to characterize the accuracy of Chinese historiography as “indisputable” because it is “the only one based on astronomical observations” (Voltaire 1745:9). As we have seen, Bossuet (1681:17–18) had Moses write down God’s law in 1491 B.C.E. or, if one used the Septuagint-based calculation, in 2450 B.C.E. At the beginning of Voltaire’s China chapter of 1745, Gaubil’s information is used to show that China’s first king reigned twenty-five centuries before Christ. The fact that he already united fifteen kingdoms, Voltaire wrote, “proves that several centuries earlier this region was very populated, governed, and partitioned in numerous sovereign countries” (p. 11). Voltaire adduced China’s gigantic population and towns, the Great Wall, its ancient use of paper and printing, and many other facts to convince his readers of both the antiquity and excellence of Chinese civilization (pp. 11–18). But near the end of his litany comes the surprising statement that there is one thing that might merit more attention than all China’s mentioned achievements: “that from time immemorial they partition the month in weeks of seven days” (p. 18). This statement persisted unrevised through all subsequent editions of the Essai, but an explanation added in the 1769 version clarifies its significance: “The Indians used this; Chaldea modeled its method on it and passed it on to the small country of Judea; but it was not adopted in Greece” (Voltaire 1829:15.268).26 The fact that Voltaire paid so much attention to this and mentioned it once more in his India chapter of 1745 (“their weeks always had seven days,” Voltaire 1745:29) indicates that already in 1745 Voltaire was determined to use ancient India and China to destabilize biblical authority. The idea that the basic scheme of the Old Testament’s creation story, the tale of seven days, was derived from far older peoples further east was a direct attack on Judeo-Christianity.

While Judea clearly was no more in competition for the oldest human culture, Voltaire was at this point still vacillating between India and China. Yet there were already signs that India was about to gain the upper hand. Voltaire mentioned that the ancient Greeks had traveled to India for instruction in the sciences and that the Arabs had adopted Indian numbers; but what most attracted his interest was the report that the Chinese emperor treasured Indian antiquities: “Perhaps the ancient Indian medals, which the Chinese make such a fuss about, are proof that the arts were cultivated in India before they became known to the Chinese” (p. 8). Regarding the other competitor, Egypt, Voltaire argued,

If one had to decide between the Indies and Egypt, I would think that the sciences are much older in the Indies; my conjecture is based on the fact that the land of the Indies is much easier to inhabit than that in the vicinity of the Nile River whose inundations doubtlessly deterred the first colonizers until they tamed this river by digging canals; besides, the soil of the Indies shows a much more varied fertility and must have stimulated human curiosity and industry to a greater degree. (p. 29)

Even though Voltaire as early as 1745 suspected that the earliest human civilization was in India, his idealization of China held up as he added to the above quotation that in India “the science of government and of morals does not seem to have been as sophisticated as with the Chinese” (p. 29). But the question of origins was far from solved in Voltaire’s mind. Eleven years later, in the 1756 version, he was to replace this last sentence about Chinese sophistication with the following:

Some have believed that the human race originated from Hindustan, arguing that the weakest animal had to be born in the mildest climate; but all origin is veiled for us. Who is able to say that there were no insects, no grass, no trees in our climates when they were present in the orient? (p. 30)

This argument about insects points to Voltaire’s belief that human beings of different races could, just like insects, have originated anywhere on the globe. In the 1761 version, he added a long paragraph in which he mocked Bibleinspired monogenetic ideas, including that of the Ezour-vedam. Voltaire’s dismissive attitude toward the Ezour-vedam is at odds with the kind of admiration and complete trust that Halbfass’s and Hawley’s narratives make readers expect. Voltaire’s trenchant critique of the Ezour-vedam tale of Adimo (here misprinted Damo but later corrected) clearly shows his unwillingness to replace biblical monogenesis with an Indian equivalent:

All these considerations [about the fertility and easy life in India] seem to strengthen the old idea that mankind was born in a land where nature did everything for men and left them with almost nothing to do; but this only proves that the Indians are indigenous, and it does not prove at all that other kinds of people came from these regions. The whites, negroes, reds, Laplanders, Samoyedes, and Albinos certainly do not stem from the same land. The difference between all these species is as marked as that between a greyhound and a mullet; thus, only a badly instructed and pigheaded Brahman would pretend that all humans descend from the Indian Damo and his wife. (Voltaire 1761:1.44)

Returning to the 1745 India chapter after this foretaste of Voltaire’s critical attitude toward the Ezour-vedam and his rejection of any monogenetic conception of origin, we note that in 1745, too, Indian religion was harshly criticized. From 1745 to the end of his life, Voltaire used the term “Bracmanes” or “Brachmanes” for the ancient clergy of India and “Bramins” for their modern successors. In 1745, he accused both the “Bonzes” (Buddhist clergy) and Brachmanes of fostering superstition, believing in metempsychosis or transmigration of souls and thus “spreading mindless stupidity [abrutissement] together with error” (Voltaire 1745:30): “Some of them are deceitful, others fanatic, and several of them are both;” and all “still prod, whenever they can, widows to immolate themselves on the body of their husbands” (p. 30).

We have already encountered several avatars of the idea that priests believe in a secret “inner” doctrine while misleading the people with “outer” lies and superstitious practices. This idea did not originate in the missions but already forms the basis of Plutarch’s portrayal of Egyptian priests in his Isis and Osiris and runs like a thread via Lactantius, Augustine’s City of God, and many other texts to the eighteenth century with its Jesuit figurists, John Toland’s Letters to Serena (1704), and Ramsay’s Voyages de Cyrus (1728) to Voltaire’s Essai. We will see in Chapters 2, 3, and 5 that one of these avatars, the Buddha’s deathbed confession story, played an important role throughout the eighteenth century. Of course, the conception of an “inner” doctrine appreciated by the elite and an “outer” one for the ignorant masses was also fundamental for Ricci and other missionaries who portrayed Chinese or Indian religions in this manner and produced the reading material that inspired Voltaire. Thus, it is by no means surprising that he adopted this very scheme in his 1745 portrait of Indian and Chinese religions. With regard to the Indians, Voltaire wrote,

These Brahmins, who maintain the populace in the most stupid idolatry nevertheless have in their hands one of the most ancient books of the world, written by one of their earliest sages, in which only one Supreme Being is recognized. They preserve with great care this testimony that condemns them. (Voltaire 1745:30)

As Pomeau (1995:161) pointed out, Voltaire here probably amalgamated information about two Indian books from a letter of January 30, 1709, by Father Lalane included in the Lettres édifiantes et curieuses collection. The first concerns a book called Panjangan that proves the Indian recognition of one supreme being. Very much in the tracks of his Jesuit colleagues in China, Father Lalane wrote,

Based on the evidence from several of their books, it seems evident to me that they [the Indians] formerly had quite distinct knowledge of the true God. This is easy to see from the beginning of a book called Panjangan whose text I have translated word for word: “I venerate this Being that is subject neither to change nor anxiety [inquiétude]; this Being whose nature is indivisible; this Being whose simplicity does not admit of any composition of qualities; this Being who is the origin and the cause of all beings and who surpasses all in excellence; this Being who is the support of the universe and the source of the three-fold power.” (Le Gobien 1781–83:11.219)27

The second refers to the Veda, which Father Lalane described as follows:

The most ancient books, which contained a purer doctrine and were written in a very ancient language, were gradually neglected, and the use of this language has entirely disappeared. This is certain with regard to the book of religion called Vedam, which the scholars of the land understand no more; they limit themselves to reading it and to learning certain passages by heart, which they then pronounce in a mysterious manner to dupe the people more easily. (p. 220)

For Voltaire’s China the same distinction applied. On one hand, he was enchanted with China’s “morality, this obedience to the laws joined to the veneration of a supreme Being” that “form the religion of China, of its emperors and scholars [lettrés]” (Voltaire 1745:22). In the 1745 Essai fragments, Confucius is said to have “established” this religion “which consists in being just and benevolent [bienfaisant]” (p. 22) and conveyed “the sanest ideas about the Divinity that the human spirit can form without revelation” (p. 23). As Voltaire did not believe in any divine revelation other than the laws of nature, reason, and the moral principles in everyone’s heart, it is clear that in 1745 he regarded this idealized Confucianism as the model of a religion. On the other hand, China also had its superstitions for the masses. Sects like the cult of “Laokium” (Laozi; Daoism) that “believe in evil spirits and magic spells [enchantements]” and “the superstition of the Bonzes” who “offer the most ridiculous cult” to the Idol Fo (Buddha) (p. 23) are certainly not to the liking of the “magistrates and scholars who are altogether separate from the people.” But these members of the elite who “nourish themselves with a purer substance” nevertheless insist that superstitious sects “be tolerated in China for use of the vulgar people, like coarse food apt to feed them” (p. 25). In Voltaire’s religion there was no tolerance for intolerance.

Unlike the scattered chapters published in 1745, the 1756 Essai was the first complete version that Voltaire submitted to the public. It resounded, as we will see in Chapter 7, not only throughout Europe but even elicited an interesting echo in far-away India.

The most striking change in the Essai’s India chapter is found at its end where Voltaire eliminated two passages that were cited above. The first is about the bonzes and brachmanes who spread mindless stupidity and are deceitful, fanatic, or both; and the second is about the brahmins who maintain the populace in the most stupid idolatry even though they safeguard a book that recognizes a supreme being. In place of such critique, Voltaire in 1756 almost justifies the Brahmins:

It would still be difficult to reconcile the sublime ideas which the brahmins preserve about the supreme being with their garrulous mythology [mythologie fabuleuse] if history would not show us similar contradictions with the Greeks and Romans. (Voltaire 1756:1.32)

What had happened in the eleven years between 1745 and 1756? How did the Brahmins get rid of their superstitions, fanaticism, and evil instigation of the ritual suicide of widows (sati)? And how did the “most stupid idolatry” get transformed into a “garrulous” or “fabulous” mythology whose contradictions are not worse than those of the Greeks and Romans? A partial answer is not found in the India and China chapters at the beginning of the 1756 Essai but rather way back in chapter 120, “On Japan.” For some reason, in this unlikely place Voltaire included new information on India, and here he also mentions a lesson learned through experience:

It is true that one must read almost all reports that arrive from faraway lands with a spirit of doubt. People are busier sending us goods from the coasts of Malabar than truths. A particular case is often portrayed as a general custom. (Voltaire 1756:3.203)

Voltaire was now informed about some of the most striking features of Asian religions. He saw “almost all peoples steeped in the opinion that their gods have frequently joined us on earth”: Vishnu had gone through nine incarnations, and the god of the Siamese, Sammonocodom (Buddha), reportedly took human form no less than 150 times (p. 204). Voltaire noted that the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans had very similar ideas, and he sought to interpret this “error” amiably and monotheistically:

Such a rash, ridiculous, and universal error nevertheless comes from a reasonable feeling that is at the bottom of all hearts. One feels naturally one’s dependence on a supreme being; and the error which always joins truth has almost everywhere caused people to regard the gods as lords who came at times to visit and reform their domains. (p. 205)

Another characteristic common to many religions is identified as atonement: “Man has always felt the need for clemency. This is the origin of the frightening penances to which the bonzes, brahmins, and fakirs subject themselves” (p. 205). For the Indian cult of the lingam, he also found Mediterranean counterparts in “the procession of the phallum of the Egyptians and the priapus of the Romans” (p. 205). Voltaire thought it “probable that this custom was introduced in times of simplicity and that at first people only thought of honoring the divinity through the symbol of the life it gave to us” (p. 205). These interpretations show how eager Voltaire was to find vestiges of monotheism even in ideas and cults that not so long ago would have elicited harsh words of condemnation or ridicule. Now he not only tried to interpret them as signs of ancient monotheism but also pointed to an ancient source:

Would you believe that among so many extravagant opinions and bizarre superstitions these Indian heathens all recognize, as we do, an infinitely perfect being? Whom they call the being of beings, the sovereign being, invisible, incomprehensible, formless, creator, and preserver, just and merciful, who deigns to impart himself to the people to guide them to eternal happiness? These ideas are contained in the Vedam, which is the book of the ancient brachmanes. They are spread in modern books of the brahmins. (p. 206)

Voltaire then hints at the source of this information: “A learned Danish missionary on the coast of Tranquebar” who “cites several passages and several prayer formulae that seem to come from straightest reason and purest holiness.” Had he finally found an alternative to the Jewish Old Testament? While in 1756 he had quoted only the first five words of a single prayer from a book called Varabadu—“O sovereign of all beings, etc.” (p. 206)—the 1761 Essai features the whole prayer; and though the source is not further identified, it appears that Voltaire got all this information from the book published in 1724 by Mathurin Veyssière de LA CROZE (1661–1739) that will be analyzed in the next chapter.

Voltaire already appears to have used La Croze’s book when writing his brief 1745 portrayal of the cult of Fo or Foe (Ch. Buddha) that described its Indian origin around 1000 B.C.E. and its popularity in most of Asia (Voltaire mentions Japan, China, Tartary, Siam, and Tibet; 1745:23–25). Such information was found in La Croze’s survey of “Indian idolatry” (1724:424–519) that contained an early synthesis of ancient and contemporary information about phenomena that we today associate with Buddhism. But it also featured much information on Indian religion that Voltaire used for the 1756 version of his Essai. La Croze, a former Benedictine monk who had converted to Protestantism, had read early accounts of the sacred scriptures of India, the Vedas, and his status as Prussia’s royal librarian helped him get access to a treasure trove of recent information on India’s religions. These were the unpublished manuscripts of the German Lutheran missionary Bartholomäus ZIEGENBALG (1682–1719), who in 1706 had arrived in South India as India’s first Protestant missionary and spent thirteen years in the Danish enclave of Tranquebar on India’s southeastern coast (Tamil Nadu). Just two months after his arrival, Ziegenbalg proclaimed in a letter what was to become the tenor of his extensive studies of Hinduism: “They have many hundreds of gods yet recognize only a single divine Being as the origin of all gods and all other things” (Bergen 1708:19).28 This assertion of ancient Indian monotheism was not only repeated and documented in Ziegenbalg’s manuscripts but also found its way into two of Voltaire’s major sources, namely, La Croze (1724) and Niecamp (1745).

Near the beginning of La Croze’s investigation about the “idolatry of the Indies,” Voltaire read that “in spite of the grossest idolatry, the existence of the infinitely perfect Being is so well established with them [the Indians] that there is no room for doubt that they have preserved this knowledge since their first establishment in the Indies” (La Croze 1724:425). Calling the Indians “one of the oldest people on earth,” La Croze thought it “a very probable fact that in ancient times they had a quite distinct knowledge of the true God and that they offered an inner cult [culte interieur] to him which was not mixed with any profanation” (p. 426). To find out more about this, La Croze suggested, one would have to get access to the Vedam, “which is the collection of the ancient sacred scriptures of the Brachmanes” (p. 427). In the Vedam “in all likelihood one would find the antiquities [Antiquitez] which the superstitiously proud Brahmins conceal from the people of India whom they regard as profane” (p. 427). Consequently, the Brahmins (the modern successors of the ancient Brachmanes) introduce ordinary people only to “the exterior of religion enveloped in legends [fables] that are at least as extravagant as those of Greek paganism” (p. 428). According to La Croze, the Vedam, which can be read only by Brahmins who are its guardians, “enjoys the same authority with these idolaters as the Sacred Writ does with us” (p. 447). Always following Ziegenbalg’s and his fellow missionaries’ manuscripts, La Croze quoted a passage “from one of the [Indian] books” about God whom the Indians call “Barabara Vástou, that is, the Being of Beings” (p. 452).29 La Croze did not identify this book, but Voltaire must have been so impressed by the information about the monotheistic Vedas that, in the 1756 Essai, he jumped to the conclusion (Voltaire 1756:3.206): “These ideas are contained in the Vedam, which is the book of the ancient brachmanes.”30 In fact, the ideas mentioned by Voltaire—“the being of beings, the sovereign being, invisible, incomprehensible, formless, creator, and preserver, just and merciful, who deigns to impart himself to the people to guide them to eternal happiness”—were culled in almost identical sequence from a longer passage in La Croze, which reads as follows (words taken over by Voltaire are italicized):

The infinitely perfect Being is known to all these gentile pagans. They call it in their language Barabara Vástou, that is, the Being of Beings. Here is how they describe it in one of their books. “The Sovereign Being is invisible and incomprehensible, immobile and without shape or exterior form. Nobody has ever seen it; time has not included it: his essence fills all things, and all things have their origin from him. All power, all wisdom, all knowledge [science], all sanctity, and all truth are in him. He is infinitely good, just, and merciful. It is he who has created all, preserves all, and who enjoys to be among men in order to guide them to eternal happiness, the happiness that consists in loving and serving him.” (La Croze 1724:452)

With regard to the lingam cult Voltaire also followed La Croze and indirectly Ziegenbalg. La Croze had explained that “the lingum . . . is a symbolic representation of God . . . but only represents God as he materializes himself in creation,” (p. 455) while Voltaire speculated that this cult “was introduced in times of simplicity and that at first people only thought of honoring the divinity through the symbol of the life it gave to us” (Voltaire 1756:3.205).

At this point, Voltaire leaned toward India as the earliest human civilization (1756:1.30) and believed that the most ancient text of this civilization was called Vedam and contained a simple and pure monotheism. So he must have been elated when a reader of his 1756 Essai, Louis-Laurent de Féderbe, Chevalier (later Comte) DE MAUDAVE (1725–77), wrote to him from India two or three years after publication of the Essai. Maudave had left in May 1757 for India and in 1758 participated in the capture of Fort St. David and the siege of Madras (Rocher 1984:77). While stationed in South India, Maudave had gotten hold of French translations from the Veda31 and decided to write a letter to Voltaire. Having read the Japan chapter of the 1756 Essai, he knew how interested Voltaire was in finding documentation for ancient Indian monotheism through the Vedam. In the margin of a page of his Ezour-vedam manuscript (which he later passed on to Voltaire), Maudave scribbled next to two prayers to God: “Copy these prayers in the letter to M. de Voltaire” (p. 80).32 Though these prayers are not found in the extant fragment of Maudave’s letter, it is likely that Maudave included them in order to document the existence of pure monotheism in the Vedam. The second major point of Voltaire’s 1756 Essai that Maudave addressed in his letter was the cult of the lingam.33 In his discussion, Maudave quoted the Ezour-vedam as textual witness and offered to send Voltaire a replica of a linga and a copy of the Ezour-vedam (Rocher 1984:48).

Maudave’s letter to Voltaire described the Ezour-vedam as a dialogue written by the author of the Vedas: “This Dialogue presupposes that Chumontou is the author of the Vedams, that he wrote them to countervail the empty superstitions that spread among men and, above all, to halt the unfortunate progress of idolatry” (p. 49). Maudave also specifically mentioned the author of the text’s French translation: “Its author is Father Martin, the former Jesuit missionary at Pondichéry” (p. 49). Since this missionary had died in Rome in 1716, Maudave must have thought that the translation from the Sanskrit original was about fifty years old. This missionary connection clearly disturbed Maudave. First of all, a strange agreement with Christian doctrine made Maudave suspicious about the quality of the translation. More than that, he let Voltaire know that his doubts were specifically connected with the tendency of the translator’s Jesuit order to find traces of their own faith in just about every part of the world—in Chinese books, in Mexico, and even among the savages of South America (p. 80)! Maudave had carefully studied the Jesuit letters including those of Calmette that announced the dispatch of the four Vedas to Paris and wrote the following about their content to Voltaire:

This body of the religion and regulations of the country is divided in four books. There is one at the Royal Library. The first contains the history of the gods. The second the dogmas. The third the morals. The fourth the civil and religious rites. They are written in this mysterious language which is here discussed and which is called the Samscrout. (Ms 1765, Musée d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris, 118v)