“Orientalism” has been portrayed by Edward SAID in his eponymous book, first published in 1979, as a very influential, state-sponsored, essentially imperialist and colonialist enterprise. For Said, the Orientalist ideology was rooted in eighteenth-century secularization that threatened the traditional Christian European worldview. That worldview had been reigning for many centuries and was based on the “Biblical framework.” Said held that “modern Orientalism derives from secularizing elements in eighteenth-century European culture” (1979:120) and pointed out the all-important role that the discovery of Oriental religions and languages played in the birth of Orientalism:

One, the expansion of the Orient further east geographically and further back temporally loosened, even dissolved, the Biblical framework considerably. Reference points were no longer Christianity and Judaism, with their fairly modest calendars and maps, but India, China, Japan, and Sumer, Buddhism, Sanskrit, Zoroastrianism, and Manu. (p. 120)

I quite agree with this. Curiously, though, only Islam—which had the least potential of loosening or dissolving the biblical framework because it made itself use of it—plays a role in Said’s argument. The European discovery of other Asian religions is strangely absent: Zoroastrianism and Brahmanism are only briefly mentioned in the context of Anquetil-Duperron’s studies (p. 76), Hinduism not at all, Confucius once in the context of Fénelon (p. 69), and Buddhism twice more, but (as in the quotation above) only as part of uncommented lists (pp. 232, 259). Focusing on political power and imperialist strategy rather than the power of religious ideology, Said was not in a position to answer how the “loosening” of the biblical framework was connected to the discovery of Asian religions and the genesis of modern Orientalism.

Robert IRWIN (2006:294) rightly criticized the “newly restrictive sense” that Said gave to the term Orientalism: “those who travelled, studied or wrote about the Arab world.” Nevertheless, he declared himself “happy to accept this somewhat arbitrary delimitation of the subject matter” for the very convenient reason that “it is the history of Western studies of Islam, Arabic and Arab history and culture that interests me most” (p. 6). It is thus hardly surprising that non-Islamic oriental religions are as little discussed in Irwin’s book-length study about Orientalism as in Said’s. For example, Buddhism—Asia’s most widespread religion—is only once mentioned in passing, and the religions of Asia’s most populous nations, India and China, play no role at all. While accusing Said of hating “religion in all its forms,” harboring “anti-religious prejudice,” and failing “properly to engage with the Christian motivations of the majority of pre-twentieth-century Orientalists” (p. 294), Irwin’s portrayal of Anquetil-Duperron and of William Jones shows an almost Saidian lack of insight into religious motivations: Anquetil-Duperron’s striking religiosity is completely ignored in favor of his “anti-imperialism” (pp. 125–26), and treatment of Jones’s religious motivations is limited to Irwin’s cursory remarks to the effect that Jones “hoped to find evidence in India for the Flood of Genesis” and had a “somewhat archaic and confused” ethnology in which “Greeks, Indians, Chinese, Japanese, Mexicans and Peruvians all descended from Noah’s son, Ham” (p. 124).

Furthermore, Irwin criticizes Said for attributing far too much importance to Orientalism. In Irwin’s view the “heyday of institutional Orientalism only arrived in the second half of the twentieth century.” Before that time, Orientalism was a relatively insignificant affair given that its exponents, according to Irwin, usually were just “individual scholars, often lonely and eccentric men” driven by curiosity rather than colonialist and imperialist rapacity. This is reflected in the title of the original English edition of Irwin’s book: “For Lust of Knowing.”1 Irwin’s Orientalists, “always few in number and rarely famous figures,” were at best influential in literary, historical, theological, cultural, and, of course, oriental studies (p. 5) but had hardly any impact outside the literary world. For the most part they were just a bunch of relatively isolated “dabblers, obsessives, evangelists, freethinkers, madmen, charlatans, pedants, romantics” driven not by grand imperialist dreams but by “many competing agendas and styles of thought” (p. 7).

This final chapter examines a member of this eccentric crowd, Constantin François de Chasseboeuf VOLNEY (1757–1820), whose life span extends a bit beyond the period covered in this book. In Said’s eyes, Volney was one of the most prominent “orthodox Orientalist authorities” (1979: 38) whose travel account (Voyage en Syrie et en Egypte, 1785–87) and reflections on the Turkish war (Considérations sur la guerre actuelle des Turcs, 1788) constituted “effective texts to be used by any European wishing to win in the Orient.” Said thus saw Volney as a major instigator of Napoleon’s imperialist invasion of Egypt (p. 81). Being “canonically hostile to Islam as a religion,” the “canny Frenchman” (p. 81) was not engaged in some haphazard “innocent scholarly endeavor.” Rather, as an archetypal exponent of “Orientalism as an accomplice to empire” (p. 333), he was fit to join William Jones near the top of Said’s Orientalist blacklist.2

Said’s critic Irwin, by astonishing contrast, portrays Volney as an Orientalist sharply critical of the collusion of religion and political tyranny and as one of the leading spokesmen against the French plan to invade Egypt. Irwin argues against Said that Volney was not just an opponent of Islam but of all religions, particularly of Christianity. Unlike Said, Irwin also mentions Volney’s most influential book, The Ruins, which was published during the French Revolution in 1791. According to Irwin, “everybody read this book. It was a bestseller and the talk of the salons, spas and gaming rooms. Even Frankenstein’s monster read it” (2006:135). But instead of enlightening the curious reader about this startling exception to Irwin’s rule of little-read Orientalist dabblings—after all, Volney’s Ruins was among the most-read books of the revolutionary period and a smashing success by any standard—Irwin complains that “no one reads Les Ruines nowadays. It is quite hard going” (p. 135). In fact, to keep our gaze on the period when attention spans were a bit longer and passions stronger, Volney’s book rapidly caught the attention of a large public, and already in 1792 an anonymous English translation was published in London. Another sign of strong interest is that excerpts of the bestseller were printed in the form of broadsides and pamphlets from late 1792 on. The full English text was also widely available in pocket-sized, undated editions (Weir 2003:48). According to E. P. Thompson, the book was “more positive and challenging, and perhaps as influential, in English radical history as Paine’s Age of Reason,” and during the mid-1790s “the cognoscenti of the London Corresponding Society—master craftsmen, shopkeepers, engravers, hosiers, printers—carried [The Ruins] around with them in their pockets (Weir 2003:48). Among such craftsmen was young William Blake, one of the myriad readers influenced by Volney (pp. 48–55). Prominent statesmen were also among the admirers of the book, for example, Volney’s friend Thomas Jefferson who, before his election as president of the United States of America, was so inspired by The Ruins that he took the time to translate no less than twenty of its twenty-four chapters into English and invited Volney to stay at Monticello (Chinard 1923).

According to Irwin, the key question addressed in Volney’s Ruins is “why the East was so impoverished and backward compared to the West,” and a large part of Volney’s answer consisted in the “prevalence of despotism in the East” (2006:135). Irwin does not mention the central role of religion in Volney’s revolutionary analysis. While both Said and Irwin failed to remark on the centrality of religious tyranny and of the power of religious ideology in Volney’s argument, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century readers certainly did not overlook this. Religion as humankind’s most fundamental value system and primary source of conflicts plays a central role in The Ruins; in fact, more than half of its total volume is taken up by the famous Orientalist’s fascinating survey of the world’s religions and his revolutionary analysis of the origin and genealogy of religious ideas.

In 1780, the twenty-three-year-old Volney began to follow courses in Arabic given by Professor Deshauterayes of the Collège Royal. His teacher was known as a dogged opponent of de Guignes’s farfetched theories about the Egyptian origin of the Chinese, and he also produced some translations and studies of Buddhism-related materials from Chinese.3 Volney also frequented the salon of Madame Helvétius, the widow of the famous naturalist and freethinker Claude-Adrien HELVÉTIUS (1717–71). In her salon, the word “atheism”—which Bernhardus Varenius had 130 years earlier smuggled into his survey of religions—had an entirely different, confident ring. Some Paris salons were teeming with skeptics, agnostics, and atheists, and the house of Madame Helvétius was their favorite hangout. Their bible was a two-volume book of 1770 titled Le système de la nature that had appeared in London under the name of “Mirabaud, perpetual secretary and one of the forty members of the Académie Française.” The name of the eminent Jean-Baptiste DE MIRABAUD (1675–1760)—who had been in his tomb for a decade when this book was supposedly written—was only a shield to protect the book’s real author: the notorious materialist and radical Paul-Henri Dietrich, Baron D’HOLBACH (1723–1789). Holbach also happened to be a frequent visitor of Madame Helvétius’s salon and became a dominating influence on young Volney.

Religion was, of course, a fashionable topic of conversation, as was the information about savages in various parts of the world that posed a continuing challenge to champions of the Bible. However, as Whiston and Lafitau and many others had proved, an author could bend the biblical narrative to a considerable degree without necessarily running the risk of being burned at the stake. In his pioneer study on the cult of fetish divinities (Du Culte des Dieux fétiches, 1760), Charles de BROSSES (1709–77) had achieved the feat of marrying primitive Africans to biblical perfection by arguing that primitive cults (such as African fetishism) only arose after the disappearence of original monotheism:

The human race had first received from God the immediate instructions adapted to the intelligence with which his goodness had equipped the humans. It is so surprising to see them subsequently fallen in a state of brute stupidity that one can hardly avoid regarding this as a just and supernatural punishment for being guilty of having forgotten the beneficial hand that had created them. (de Brosses 1760:15)

Only God’s “immediate instructions,” that is, divine revelation, could explain primeval monotheism since “the human spirit could not have found in itself what led it immediately to the pure principles of theism” (p. 207). De Brosses thus held that “all peoples began with correct notions of an intellectual religion that they later corrupted with the most stupid idolatries” (pp. 195–96). Looking back at the history of humanity from his perch at the apex of French academia, de Brosses saw increasing darkness and blindness pointing to an ancient common polytheism: “The most ancient memory of these people always presents polytheism as the common and ubiquitous system” (p. 204). But such common polytheism was not really the primeval human religion; rather, it was only the result of the biblical deluge: “One sees that the arts of primitive times were lost, that previously gained knowledge was buried under the waters, and that almost everywhere a pure state of barbarity reigned: natural effects of such a general and powerful revolution” (p. 204). Not unlike Giambattista VICO (1668–1744) in his Scienza nuova, de Brosses thus used the deluge as a means of marrying a secular scenario of primitivity and progress to the Christian scenario that ran exactly in the opposite direction, that is, from initial perfection to such degradation that divine intervention in the form of Jesus’s incarnation became necessary.

This was a far cry from the radicalism of Baron d’Holbach, who turned this scheme of initial perfection and subsequent degeneration not just on its head but attempted to reduce it to rubble. For Holbach there was neither a paradise at the beginning of history nor a creator God; in fact, there was no beginning at all since some form of matter infused with energy had always existed and will always exist (Holbach 1770:1.26). “Had one observed nature without prejudice,” he wrote, “one would have been convinced for ages that matter acts by its own force and has no need of any exterior impulsion to set it in motion” (1.22–23). Holbach thus frontally attacked the very foundation of the three Abrahamic religions:

Those who admit a cause exterior to matter are obliged to believe that this cause produced all the movement in this matter by giving it existence. This supposition is based on another, namely, that matter could begin to exist—a hypothesis that until this moment has never been demonstrated by valid proofs. The summoning out of nothing, or creation, is no more than a word which cannot give us any idea of the formation of the universe; it has no meaning upon which the mind can rely. The notion becomes even more obscure when the creation or formation of matter is attributed to a spiritual being, that is, a being which has no analogy and no connection whatsoever with matter. (1.25–26)

Following Epicurus and Lucretius, Holbach’s “nature” is eternal and inherently energetic (2:172). Instead of creation, he sees only transformations of the existing into different forms, “a transmigration, an exchange, a continuous circulation of the molecules of matter” (1:33). It is thus the inherent movement of matter, not some God, that accounts for production, growth, and alteration. From the formation of rocks inside the earth to that of suns and from the oyster to man, there is “a continuous progression, a perpetual chain of combinations and movements resulting in beings that differ among themselves only by the variety of their constituent elements and the combinations and proportions of these elements which give rise to infinitely diverse ways of existing and acting” (1.39). All constituents of the universe follow the order of nature; what may appear to be a disorder, for example, death, is in fact only a transition and a new combination of elements.4 For Holbach, everything is bound to matter infused with energy:

An intelligent being is a being that thinks, wills, and acts to achieve a goal. Now in order to think, will, and act as we do there is a need for organs and a goal that resembles ours. So, to say that nature is governed by an intelligence is to pretend that she is governed by a being equipped with organs, given that without organs there can be no perception, no idea, no intuition, no thought, no will, no plan, and no action. (1.66)

To speak of God or divinity or creation is thus only a sign of the ignorance of nature’s energy; and man, supposedly the goal of creation, is only one of nature’s myriad and fleeting transformations. He is an integral part of nature obeying its universal laws of cause and effect and of self-preservation by attraction of the favorable and repulsion of the unfavorable (1:45–46). Nine decades before Charles Darwin, Holbach was not yet able to clarify man’s origin and to determine whether he “has always been what he is” or “was obliged to pass through an infinity of successive developments” (1.80); due to lack of reliable data, Holbach left the question open while taking issue with the notion that man is the crown of creation:

Let us then conclude that man has no reason at all to regard himself as a privileged being in nature; he is subject to the same vicissitudes as all her other productions. His pretended prerogatives are based on an error. If he elevates himself by imagination above the globe that he inhabits and looks down upon his own species with an impartial eye, he will see that man, like every tree producing fruit in consequence of its species, acts by virtue of his particular energy and produces fruits—actions, works—that are equally necessary. He will feel that the illusion that makes him favor himself arises from being simultaneously spectator and part of the universe. He will recognize that the idea of preeminence which he attaches to his being has no other basis than his self-interest and the predilection he has in favor of himself. (1.88–89)

But for Holbach such egoism is only natural since the goal of man, like that of nature as a whole, is self-preservation and well-being (1.133); and the realization that this goal necessitates cooperation with others and involves the happiness of others forms the basis of morality, law, politics, and education (1.139–47). In this manner Holbach attacked not only the cosmological and religious authority of the Judeo-Christian tradition and other forms of theism but also their exclusive claim to morality. Instead of commandments revealed on Mt. Sinai, Mosaic law, Confucian maxims, Christian catechisms, or Herbert’s five common notions, Holbach proposed a universal natural basis of morality:

If man, according to his nature, is forced to desire his well-being, he is forced to love the means leading to it; it would be useless and perhaps unjust to demand that a man should be virtuous if he could only become so by rendering himself miserable. As soon as vice renders him happy, he must love vice; and if he sees inutility honored and crime rewarded, what interest would he find in working toward the happiness of his fellow creatures or restraining the fury of his passions? (1.151)

It is thus not through revealed scriptures and commandments from above that man’s morality is assured but through self-interest that is healthy and informed enough to encompass fellow beings and the outside world. Gaining true ideas, that is, ideas based on nature and not imagination, is, according to Holbach, the only remedy for the ills of man (1:351). But from where do those ills originate in the first place? From illusions and false ideas; for “as soon as man’s mind is filled with false ideas and dangerous opinions, his whole conduct tends to become a long chain of errors and depraved actions” (1.151). And since religion and its representatives, according to Holbach, concentrate on fostering such false ideas, they must be identified as the source of man’s evils:

If we consult experience, we will see that it is in illusions and sacred opinions that we must search out the true source of that multitude of evils which almost everywhere overwhelms mankind. The ignorance of natural causes created the gods for him; imposture rendered them terrible to him; these fatal ideas haunted him without rendering him better; made him tremble without any benefit; filled his mind with chimeras; hindered the progress of his reason; and prevented him from seeking his happiness. (1.339)

The role of priestcraft in this perversion of nature was most objectionable to Holbach, and like the English deists, he loved describing the fatal results of the clergy’s deception in the most graphic terms:

His fears rendered him the slave of those who deceived him under the pretext of his welfare; he committed evil when told that his gods demanded crimes; he lived in misfortune because they made him believe that the gods had condemned him to be miserable. He never dared to throw off his chains because he was given to understand that stupidity, the renunciation of reason, sloth of mind, and abjection of his soul were the sure means of obtaining eternal felicity. (1.339)

The importance of the subject of religion to Holbach is highlighted by the fact that he devoted the entire second volume of his System of Nature to it. Instead of primitive monotheism, Holbach saw a gradual development of religious cults and offered the following genealogy of monotheism:

The first theology of man was to fear and adore the elements themselves, material and coarse objects; then he extended his reverence to the agents that he imagined to preside over these elements: to powerful spirits, inferior spirits, heroes, or to men endowed with great qualities. While thinking about this, he believed he would simplify things by putting the whole of nature under the rule of a single agent, a sovereign intelligence, a spirit, a universal soul that set this nature and its parts in motion. Recurring from cause to cause, the mortals ended up seeing nothing at all, and it is in this obscurity that they placed their God. In this dark abyss their feverish imagination went on and on churning out chimeras which they will be smitten with until their knowledge of nature shall disabuse them of the phantoms that they have for so long adored in vain. (2.16)

For Holbach, theistic religion was a giant mistake; accordingly, he filled page after page of the second volume with the diagnosis of its origin, characteristics, and disastrous effects. Whether humanity had forever been on this globe or constituted a recent invention of nature that arose after one of nature’s periodical revolutions: a look at the origin of various nations convinced Holbach that, contrary to the mosaic narrative, primitivity and savagery always marked the beginning (2.31). In this point he fully agreed with David Hume’s analysis that was briefly mentioned in Chapter 5.

In contrast to Volney’s Ruins, Holbach’s System of Nature focuses on the Judeo-Christian tradition and its champions and rarely mentions other religions. Its argument aims at generality but betrays its theistically parochial nature by statements such as “all religions of the world show us God as an absolute ruler” (2.113); “all religions of the world posit a God continually occupied with rebuilding, repairing, undoing, rectifiying his marvelous works” (2.115); “the thinkers of all centuries and all nations quarrel without respite . . . about the attributes and qualities of a God that they have in vain occupied themselves with” (2.191); and “all nations recognize an evil sovereign God” (2.236). At any rate, what people call religion was for Holbach nothing but superstition:

By the admission even of the theologians, mankind is without religion; it only has superstitions. According to them, superstition is a badly understood and unreasonable cult of the deity: or else a cult offered to a false divinity. But where is a people or a clergy that agrees that its divinity is false and its cult unreasonable? How can one decide who is right and who is wrong? (2.291)

Only someone who freed himself of such superstition could be called truly religious; and that is exactly what Holbach understood by atheism.

What is really an atheist? It is a man who destroys the pernicious chimeras of humankind to lead the people back to nature, to experience, to reason. It is a thinker who has meditated matter, its energy, its characteristics and manners of action, and has no need of imagining ideal powers to explain the phenomena of the universe and the workings of nature. (2.320)

This was the kind of provocative discourse that evoked passionate discussions at Madame Helvétius’s salon frequented by Volney and his friends. There is no doubt that Holbach’s Epicurean view of nature and his radical vision of religion exerted a strong influence on Volney. But his focus on the Abrahamic religions prevented him from furnishing a panorama of religion that was truly global in scope. This was an opening for Volney. If Holbach had delivered his diagnosis in the System of Nature (1770) and presented a therapy in his Catéchisme de la nature (1790), Volney offered the former in The Ruins (1791) and the latter in his Natural law or the catechism of the French people (1793).

In the opening scene of Volney’s The Ruins, the narrator is caught in a religious mood while contemplating the ruins of Palmyra:

The solitariness of the situation, the serenity of evening, and the grandeur of the scene, impressed my mind with religious thoughtfulness. The view of an illustrious city deserted, the remembrance of past times, their comparison with the present state of things, all combined to raise my heart to a strain of sublime meditations. I sat down on the base of a column; and there, my elbow on my knee, and my head resting on my hand, sometimes turning my eyes towards the desert, and sometimes fixing them on the ruins, I fell into a profound reverie. (Volney 1796:5)

Why had this city of Palmyra and the whole region been so prosperous while the “unbelieving people” inhabited them: “the Phenician, offering human sacrifices to Moloch,” the Chaldaean “prostrating himself before a serpent,” the Persian “worshipper of fire,” and the city’s “adorers of the sun and stars, who erected so many monuments of affluence and luxury”? And why was it now, as it lay in the hands of “the elect of Heaven” and “children of the prophets”—Christians, Muslims, and Jews—in poverty and decay, bereft of God’s “gifts and miracles” (pp. 9–10)? Was this due to some malediction, or was it decreed by the “incomprehensible judgments” of “a mysterious God” (p. 13)? Lost in such gloomy thoughts, the narrator suddenly becomes aware of a “pale apparition, enveloped in an immense drapery, similar to what spectres are painted when issuing out of the tombs.” It begins to talk to him in “a hollow voice, in grave and solemn accents” (p. 14) and promises, “I will display to your view this truth of which you are in pursuit; I will show to your reason the knowledge which you desire; I will reveal to you the wisdom of the tombs, and the science of the ages” (p. 25).

Carried aloft on the wing of this apparition, the man suddenly sees the world from an entirely different viewpoint: “Under my feet, floating in empty space, a globe similar to that of the moon” (p. 25). Volney’s narrator thus learns to see our planet, its peoples, their political systems, and their religions from a global perspective. The apparition explains to him that the first human beings had, in a “savage and barbarous state,” been driven by “inordinate desire of accumulation” that brought with it “rapine, violence, and murder” (p. 61). In its innumerable disguises, this “spirit of rapacity” had been “the perpetual scourge of nations” and the hotbed of political as well as religious despotism and tyranny (p. 63). Political and religious oppression are portrayed as closely related: in the state of political oppression, people fell into despair and were so terrified by calamities that they “referred the causes of them to superior and invisible powers: because they had tyrants upon earth, they supposed there to be tyrants in heaven; and superstition came in aid to aggravate the disasters of nations” (p. 73). Volney’s narrator thus understands the origin of those “gloomy and misanthropic systems of religion, which painted the gods malignant and envious like human despots” (p. 73), and he mentions some of the means by which the priests, those “sacred impostors,” took “advantage of the credulity of the ignorant” (p. 64):

In the secrecy of temples, and behind the veil of altars, they have made the Gods speak and act; have delivered oracles, worked pretended miracles, ordered sacrifices, imposed offerings, prescribed endowments; and, under the name of theocracy and religion, the State has been tormented by the passions of the priests. (p. 64)

Religious impostors also took advantage of man’s wishful thinking: frustrated by unfulfilled hopes and lack of happiness, man “formed to himself another country, an asylum, where, out of the reach of tyrants, he should regain all his rights.” (p. 74)

Smitten with his imaginary world, man despised the world of nature: for chimerical hopes he neglected the reality. He no longer considered his life but as a fatiguing journey, a painful dream; his body as a prison that withheld him from his felicity; the earth as a place of exile and pilgrimage, which he disdained to cultivate. (p. 74)

Whether man projected such chimerical hopes onto a future life in the yonder or on an imagined past “which is merely the discoloration of his chagrin” (p. 106), his illusion tended to increase the baleful effects of “ignorance, superstition and fanaticism” whose continuous power is apparent in the smoke that Volney’s narrator sees rising high above the battlefields of Asia where Turkish Muslims battle Christian Muscovites (pp. 77–83). Now the narrator begins to understand the basic mechanism of the deceit of humankind: impostors “who have pretended that God made man in his own image” yet in reality “made God in theirs.” Ascribing him their weaknesses, errors, and vices, they pretend to be in the confidence of God and to be able to change his behavior (pp. 84–85). Instituting observances such as the Jewish sabbath, the Persian cult of fire, the Indian repetition of the word Aûm, or the Muslim’s ablutions (pp. 85–86), this “race of impostors” (p. 85) claims that the impartial God preferred a single sect of a single religion—namely, theirs—and withheld knowledge of his will to all except the prophet of their creed. It is exactly this kind of exclusive claim to absolute truth that contradicts and condemns all rival claims that, according to Volney, need to be abolished in a revolution that proclaims “equality, liberty, and justice” (p. 139).

Volney’s readership could harbor no doubt that The Ruins was a revolutionary manifesto. If his subsequent booklet La loi naturelle, ou principes physiques de la morale (The Natural Law, or Physical Principles of Morality) of 1793 attempted to lay out a course of therapy, The Ruins offered the diagnosis of the ailment. Both civil and religious tyrants had much to fear from the trinity of revolutionary values:

What a swarm of evils, cried they, are included in these three words! If all men are equal, where is our exclusive right to honours and power? If all men are, or ought to be free, what becomes of our slaves, our vassals, our property? If all are equal in a civil capacity, where are our privileges of birth and succession, and what becomes of nobility? If all are equal before God, where will be the need for mediators, and what is to become of priesthood? Ah! let us accomplish without a moment’s delay the destruction of a germ so prolific and contagious! (Volney 1796:142)

In chapters 19 to 21 of The Ruins,5 Volney did his best to nurture this contagious germ of equality and freedom. He chose to do so by a confrontation of the religious opinions of humankind in a council of the chiefs of nations and representatives of religions. It is designed to “dissipate the illusion of evil habits and prejudice” (p. 144) and have the impartial light of truth enlighten all peoples of the world.

Let us terminate to day the long combat of error: let us establish between it and truth a solemn contest: let us call in men of every nation to assist us in the judgment: let us convoke a general assembly of the world; let them be judges in their own cause; and in the successive trial of every system, let no champion and no argument be wanting to the side of prejudice or of reason. (p. 145)

No sooner had the inhabitants of the earth gathered, agreed to “banish all tyranny and discord,” and enthusiastically chanted the words “equality, justice, union” than the major source of conflict became apparent:

Every nation assumed exclusive pretensions, and claimed the preference for its own opinions and code. “You are in error,” said the parties pointing at each other; “we alone are in possession of reason and truth; ours is the true law, the genuine rule of justice and right, the sole means of happiness and perfection; all other men are either blind or rebellious.” (pp. 151–52)

The demolition of such unproven claims to exclusive possession of truth is exactly the aim of Volney’s chapters 20 (“Investigation of Truth”) and 21 (“Problem of Religious Contradictions”). He has representatives of each religion explain the central doctrines; but no sooner has each group laid out its tenets than its assumptions are severely criticized by representatives of other faiths.

In the thirteenth century, Roger Bacon had, in imitation of the Great Khan’s open debate of religions, adopted a similar scheme of competitive argument: but he had too quickly declared victory for the Christians on the grounds that “philosophy” is in perfect accord with such doctrines as the “blessed Trinity, Christ, and the Blessed Virgin, creation of the world, angels, souls, judgment to come, life eternal, resurrection of the body, punishment in hell, and the like” (Bacon 1928:2.807). Obviously, the Jews, Muslims, and idolaters had no chance against such impeccable logic. Predictably, Bacon’s argument culminated in his assertion that perfectly illustrates the attitude criticized by Volney: because “Christ is God, which is not true of Mahomet and Moses according to the testimony of even Jews and Saracens, it is evident that he alone is the perfect lawgiver, and that there should be no comparison of Moses and Mahomet or of any one else with him” (2.814).

Volney, by contrast, lets a mass of “worshippers of Jesus” acknowledge using the same books as the Muslims and believing in “a first man, who lost the whole human race by eating an apple.” Though the Christian also professes faith in a single God, he “proceeds to divide him into three persons, making each an entire and complete God” (Volney 1796:158). He believes in an omnipresent God but nevertheless is adamant that “this Being, who fills the universe, reduced himself to the stature and form of a man, and assumed material, perishable, and limited organs, without ceasing to be immaterial, eternal, and infinite” (p. 159). Not only that, the Christians are extremely divided among themselves and dispute almost everything regarding God’s essence, mode of acting, and attributes (p. 159); hence, Christianity’s “innumerable sects, of which two or three hundred have already perished, and three or four hundred others still exist.” In Volney’s universal assembly, the large Christian delegation is led by a Roman faction in “absurd and discordant” attire, followed by adherents of the Greek pontiff who dispute Roman legitimacy, Lutherans and Calvinists who accept the authority of neither, and an exotic crowd of sectarians: “the Nestorians, the Eutycheans, the Jacobites, the Iconoclasts, the Anabaptists, the Presbyterians, the Wiclifites, the Osiandrins, the Manicheans, the Pietists, the Adamites, the Enthusiasts, the Quakers, the Weepers, together with a hundred others,” all “hating each other in the name of the God of peace” (p. 161) and convinced of their exclusive claim to truth, even if that means perpetrating or suffering persecution.

Volney’s portraits of other religions are hardly more flattering. The Jews insist on being God’s favorite people “whose perfection consists in the cutting off of a morsel of their flesh” yet reduce their almost total insignificance in terms of numbers (“this atom of people that in the ocean of mankind is but a small wave”) even more by acrid dispute about fundamental tenets among its two principal sects (pp. 162–63). The disciples of Zoroaster, now feeble and dispersed, will, as soon as they pick up the broken pieces of their creed, begin to dispute anew “the literal and allegorical senses” of “the combats of Ormuz, God of light, and Ahrimanes, God of darkness” as well as good and evil genii and “the resurrection of the body, or the soul, or both” (p. 164). The Indians worship gods like “Brama, who, though the Creator of the universe, has neither followers nor temples” and is “reduced to serve as a pedestal to the Lingam” (p. 165), or “Vichenou, who, though preserver of the universe, has passed a part of his life in malevolent actions” (p. 166)—not to speak of the Indian people’s “multitude of Gods, male, female, and hermaphrodite, related to and connected with the three principal, who pass their lives in intestine war, and are in this respect imitated by their worshippers” (p. 167). The believers in the God “Budd” who worship him under many different names in numerous Asian countries—Volney mentions China, Japan, Ceylon, Laos, Burma, Thailand, Tibet, and Siberia—disagree about the necessary rites and ceremonies, are divided about “the dogmas of their interior and their public doctrines,” and quarrel about the preeminence of incarnations of their God in Tibet and Siberia (p. 168). Volney also mentions other religions such as Japanese Shinto (p. 168), Confucianism (p. 169), the religions of the Tartars and other Siberians (pp. 169–170), and those of the “sooty inhabitants of Africa, who, while they worship their Fetiches, entertain the same opinions” as the shamans of Siberia (p. 170). But the picture is the same everywhere: the world’s religions are an ideal breeding ground for division and conflict.

Like Varenius, Volney also has a special category in his lineup: people without any desire to join the colorful club of religions. However, unlike some of Varenius’s atheists, they do not belong to the civilized nations:

In fine, there are a hundred other savage nations, who, entertaining none of these ideas of civilized countries respecting God, the soul, and a future state, exercise no species of worship, and yet are not less favoured with the gifts of nature, in the irreligion to which nature has destined them. (p. 171)

With this reminder of the narrator’s initial question why Palmyra flourished when governed by heathen and fell into ruin while in the hands of God’s faithful, Volney turns to the analysis of some of the major contradictions in the discussed religions. Rival claims of monopolies of divine revelation, proof of their truth via miracles and martyrdom, unique records of divine communication, and so on quickly show that there can be no common ground as long as everybody insists that his religion “is the only true and infallible doctrine” (p. 173). A revolution is called for.

Volney’s Ruins is obviously a composite book consisting of segments that had been written separately and for different purposes. The initial ode and introductory section may stem from 1787 or earlier; in fact, the preface and the last page of Volney’s 1787 travelogue already announce The Ruins. The body of the book can, I think, be associated with three revolutions that Volney was intimately involved in.

During the time of the book’s composition, Volney became a major player in the French Revolution. He published political pamphlets, became a member of the commission for the study of the revolutionary constitution, and worked as an influential legislator (Gaulmier 1959:65–111). His political and revolutionary interests are reflected in the titles of chapters 5 (“Condition of Man in the Universe”), 6 (“Original State of Man”), 7 (“Principles of Society”), 8 (“Source of the Evils of Society”), 9 (“Origin of Government and Laws”), 10 (“General Causes of the Prosperity of Ancient States”), 11 (“General Causes of the Revolutions and Ruin of Ancient States”), 12 (“Lessons Taught by Ancient, Repeated in Modern Times”), 13 (“Will the Human Race Be Ever in a Better Condition Than at Present?”), 14 (“Grand Obstacle to Improvement”), 15 (“New Age”), 16 (“A Free and Legislative People”), 17 (“Universal Basis of All Right and All Law”), and finally chapter 18 (“Consternation and Conspiracy of Tyrants”), which ends with the convocation of a general assembly of religions. This entire group of chapters is related to Volney’s political and legislative activities during the French Revolution and appears to have been written between the revolution’s first climax in 1789 when Volney became member of the representative assembly of the three estates (États généraux) and 1790 when he was elected to the influential position of secretary of the National Constituent Assembly.

The work of eighteenth-century luminaries like Pierre Bayle, Voltaire, the French encyclopedists, Buffon, Hume, Helvétius, Holbach, and Charles-François Dupuis contributed to the erosion of biblical authority and helped in creating a revolutionary picture of religions, their origin, and their role. Christianity and its Jewish parent came to be seen as peculiar varieties of Mediterranean religions and their scriptures as repositories of local myths that were not only younger but also in many ways inferior to their Asian competitors (see Chapter 1). Our quick survey has already shown how modern Volney’s conception of religion appears in comparison even with that of Holbach. The Ruins marks a decisive stage in what W. C. Smith has called the “reification” of religion—a stage in which even the deist attachment to a creator God evaporated and Christianity lost its incomparability. It now became an object of impartial study as an exemplar of “religion in general” (Smith 1991:43–49) whose sacred scriptures and doctrines, just like those of any other cult, had to undergo critical scrutiny and comparison. Thus, Volney’s assembly of religions had to begin with the agreement to “seek truth, as if none of us had possession of it” (Volney 1796:172).

It has recently been claimed that the “construction of ‘religion’ and ‘religions’ as global, cross-cultural objects of study has been part of a wider historical process of western imperialism, colonialism, and neocolonialism” (Fitzgerald 2000:8) and that the origin of modern comparative religions or the science of religion can be located between 1859 and 1869 (Sharpe 1986:27). Fitzgerald’s point that much of the field of “religious studies” is still theology in disguise is valid; but it helps to investigate such issues in a broader historical and cultural context.6 Volney’s Ruins and the other case studies of this book illustrate both the complexity of processes at work and the very limited usefulness of bumper sticker labels such as “western imperialism” and “colonialism.”

In the second half of the eighteenth century, Europe’s confrontation with an increasingly complex world and an exploding history triggered an extraordinary amount of thought about the origin of things. Academies held essay contests about the origin of inequality among men (inspiring Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s first philosophical work in 1755) or the origin of language (won by J. G. Herder in 1772); among European historians and philosophers, it became fashion to inquire about the origins of just about anything. For example, in 1758, Antoine-Yves Goguet published three volumes of his thoughts On the origin of laws, the arts, and sciences and their progress among the ancients; in 1773, the first volume of Antoine Court de Gébelin’s 9-volume set of studies on the primeval world appeared; in 1777, Jean-Sylvain Bailly published his letters to Voltaire about the origin of sciences and their Asian inventors; and in 1781, Dupuis offered to the public his analysis on the origin of star constellations, which had such a profound impact on Volney and his Ruins.

In this environment, it was only natural that the origin of religion should also be a question of great interest. Volney addressed it in Chapter 22 of The Ruins (“Origin and Genealogy of Religious Ideas”) which is disproportionately large (13 subsections). Chapter 22 appears to have been written as a separate essay under the influence of Holbach, Helvétius, and Dupuis before 1787. It fits awkwardly into the narrative; it seems as if a drab professor of religious studies took over the speaker’s podium to lecture the representatives of the world’s religions on his pet theory about the origin of religions. He is only occasionally interrupted by representatives of the world’s religions muttering a few words of protest when one of the pillars of their faith gets reduced to astrological hocus pocus.

In spite of such stylistic problems, Volney’s ideas about the origin of religions and of religious ideas are of great interest. Like David HUME’s (1711–76) account in The Natural History of Religion (1757) and the second volume of Holbach’s Systême de la nature (1770), Volney’s history of religion begins with an “original barbarous state of mankind” (Volney 1796:224). He explains:

If you take a retrospect of the whole history of the spirit of religion, you will find, that in its origin it had no other author than the sensations and wants of man: that the idea of God had no other type, no other model, than that of physical powers, material existences, operating good or evil, by impressions of pleasure or pain on sensible beings. You will find that in the formation of every system, this spirit of religion pursued the same track, and was uniform in its proceedings; that in all, the dogma never failed to represent, under the name of God, the operations of nature and the passions and prejudices of man; that in all, morality had for its sole end, desire of happiness and aversion to pain. (p. 295)

In stark contrast to the usual perfection-fall-redemption scheme of Christian theologians, Volney’s genealogy of religions traces humanity’s tortuous path from total primitivity toward advanced theistic superstition and religious despotism—a state that cries out for a revolution and a new catechism for the citizen. The Ruins is the manifesto for this revolution, and Volney’s catechism (which he called the “second part” of The Ruins) proposes a “geometry of morals” that reduces God’s role to the provision of natural law (Volney 1826:1.253).

Volney thus offers a rather bleak vision of the nature and history of religion. The Ruins’s representative of “those who had made the origin and genealogy of religious ideas their peculiar study” (p. 297) regards the entire history of religion as “merely that of the fallibility and uncertainty of the human mind, which, placed in a world that it does not comprehend, is yet desirous of solving the enigma” (pp. 295–96). Thus, ignorant men invent causes, suppose ends, build systems, and create “chimeras of heterogeneous and contradictory beings,” losing themselves “in a labyrinth of torments and delusions” while “ever dreaming of wisdom and happiness” (p. 296).

Volney’s view of Christianity, which radicalizes Dupuis’s outlook, has a particularly revolutionary tint. The title of the longest subsection of Volney’s genealogy of religious ideas, section 13, ominously reads “Christianity, or the allegorical worship of the Sun, under the cabalistical names of Chris-en or Christ, and Yês-us or Jesus” (p. 283). Volney not only reduces major elements of Christian dogma to features of sidereal worship but declares that the Savior himself, Jesus of Nazareth, represents a solar myth and must thus be regarded as a mythological rather than a historical figure. The Christians may have faith in their Son of God, “this restorer of the divine or celestial nature” who in his infancy led “a mean, humble, obscure, and indigent life,” but Volney’s professor mercilessly demythologizes their belief:

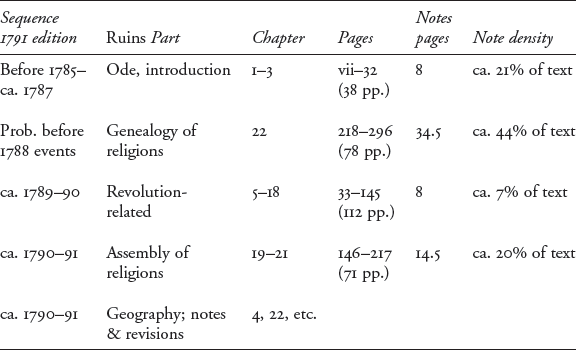

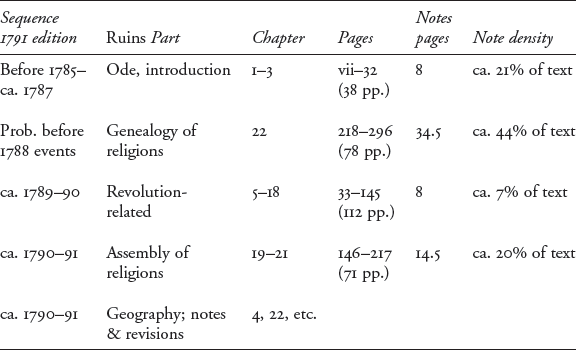

TABLE 18. PHASES IN THE GENESIS OF VOLNEY’S RUINS

By which was meant, that the winter sun was humbled, depressed below the horizon, and that this first period of his four ages, or the seasons, was a period of obscurity and indigence, of fasting and privation. (p. 292)

As mentioned above, Volney’s essay on the origin and genealogy of religious ideas (chapter 22 of The Ruins) appears to have been written earlier than chapters 19, 20, and 21 on the assembly of religions. In his 1791 preface (1796:iii), Volney notes that he had formed the plan of The Ruins “nearly ten years ago,” around the time of his travels in the Middle East (December 1782 to April 1785) and that his work was already “in some forwardness when the events of 1788 in France interrupted it” (p. iii). Such information, along with data gained from the analysis of Volney’s sources, discrepancies in style, annotation density, and content of specific parts of The Ruins (shown in Table 18) suggests the genealogy of the text.

Of special interest in our context are some important discrepancies in Volney’s view of Asian religions between the earlier “Genealogy of religions” (chapter 22) and the later “Assembly of religions” (chapters 19–21). They mainly concern his abandonment of Egypt as the geographical location of humanity’s cradle. This is a symptom of a revolution that involved, as we have seen, a deepening crisis of biblical authority and new scenarios for humankind’s origin based on the study of Asian antiquities and texts. Since the mid-seventeenth century, questions about the authenticity of the Bible and particularly its first chapters by the likes of Isaac LA PEYRÈRE (1596–1676) and Baruch SPINOZA (1632–77) grew louder; and in 1753, four years before Volney’s birth, the Frenchman Jean ASTRUC (1684–1766) presented a detailed analysis of the glaring inconsistencies pointing to multiple authors and textual layers of the Pentateuch. The growing realization that the Pentateuch was a local myth of origin rather than a universal history went hand in hand with the study of Asian texts whose claim to antiquity seemed formidable. Alternative narratives of origin began to be explored, and many of them were based on reputedly very ancient Oriental sources. The Ruins was written at an important juncture of this revolution, and its layers reflect three distinct phases.

The earliest layer, Volney’s “genealogy of religions” (chapter 22), still shows little influence of contemporary scholarship on non-Islamic Asian religions. It cites only three, rather dated, sources: Kircher’s Oedipus Aegyptiacus (1654), Hyde’s Historia religionis veterum persarum (1700), and Beausobre’s Histoire critique de Manichée et du manicheïsme (1734).

The second layer (the “assembly of religions” section, chapters 19–21), by contrast, refers to more recent sources. Apart from Engelbert Kaempfer’s study of Siamese and Japanese religions (1729) Volney here cites the history of the Huns by de Guignes (1756), Giorgi’s Alphabetum Tibetanum (1762), Holwell’s Interesting historical events (1765–71), Mailla’s History of China (1777–83), the Ezour vedam (1778), and Sonnerat’s voyages (1782). Volney certainly also used Dow’s History of Hindostan and materials by his compatriot Anquetil-Duperron but pointedly included no reference to them. At the time of writing The Ruins, Volney must have heard that the first two volumes of the Asiatick Researches were published in Calcutta in 1788 and 1790. However, he had not yet gained access to this new source, which was to ring in a new phase of the European discovery of Asia’s religions. Apart from the first published translation of a genuine Indian classic, Charles Wilkins’s Bhagvat Geeta (1785), Volney may also have consulted Francis Gladwin’s Asiatic Miscellany.7 But The Ruins was published just before the Asiatick Researches and other new English sources became available on the European continent. Volney wrote,

Scarcely even is the Asiatic Miscellany known in Europe, and a man must be very learned in oriental antiquity before he so much as hears of the Jones’s, the Wilkins’s and the Halhed’s, &c. As to the sacred books of the Hindoos, all that are yet in our hands are the Bhagvat Geeta, the Ezour-Vedam, the Bagavadam, and certain fragments of the Chastres printed at the end of the Bhagvat Geeta. These books are in Indostan what the Old and New Testament are in Christendom, the Koran in Turkey, the Sad-der and the Zendavesta among the Parses, &c. (p. 351)

The third layer consists of the changes that Volney made to The Ruins between 1816 and his death in 1820. They were incorporated in the version published as part of his collected works in 1826. Volney mainly eliminated notes that had become outdated, revised old notes, and added new ones that exhibit his continued research on Asian religions and growing interest in Buddhism. The changes in Volney’s view of this religion, which will be discussed below, represent significant signposts of the third major revolution that took place in Volney’s lifetime: the revolution triggered and sustained by the work of orientalists and the beginnings of organized, state-supported Orientalism.

The first phase of the Orientalist revolution that, as was shown in Chapter 1, saw India gradually move to center stage, shows surprising parallels to aspects of the Italian Renaissance three centuries earlier. The Italian Renaissance had also been inspired by antiquity and obsessed with origins, and the hermetic texts—supposedly the world’s most ancient works by Hermes Trismegistos, the inventor of writing—were naturally of great interest. In 1460, while Marsilio FICINO (1433–99) was translating the books of another major inspiration of the Renaissance, Plato, his sponsor Cosimo de Medici convinced him to render the hermetic texts into Latin first. Ficino’s translation was finished in 1463 and published in 1471 under the title of Pimander. Ficino’s preface called Hermes Trismegistos “the first theologian” and “the first philosopher who turned from natural and mathematical subjects to the contemplation of the divine” and situates him at the beginning of a line of esoteric transmission leading to Pythagoras and Plato (Ebeling 2005:92).

Already in the sixteenth century doubts were aired about the authenticity of the Pimander (pp. 130–31), but even in the early 1700s when it became common knowledge that these texts were for the most part products of the first Christian centuries (Nock and Festugière 1960), the hermetic renaissance continued in the writings of men like Kircher and Ralph Cudworth as well as the arcane doctrines of Rosicrucians, alchemists, and freemasons.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, a very similar mechanism was at work: Europeans were once more confronting the Orient and were in search of their identity and origin. But this time the Orient was—thanks to many missionaries, travelers, traders, and scholars—much larger and more diverse. As more information about the world and its peoples accumulated and the biblical narrative gradually lost credibility, humanity’s past seemed murkier than ever. The French encyclopedists “kept repeating that all the sciences, all the arts, all human wisdom had been invented in Egypt,” and they often linked their view of Egypt as the cradle of humanity to a portrayal of the Hebrews as “a gross, brutal, uncultivated, unlearned people” (Hubert 1923:42). However, thanks in part to Voltaire’s provocative publications (see Chapter 1), during the 1760s and 1770s India became the new focus of interest in the search for beginnings. Could the Vedas and other ancient texts of India throw a ray of light into the darkness of antiquity?

It is obvious that the “oriental renaissance” of the nineteenth century described by Schwab (1950) had roots that stretched deep into the eighteenth-century orientalist revolution with its decisive turn toward India and “Indian” texts. The authenticity and age of these texts were as vastly overestimated as those of the hermetic texts during the Italian Renaissance three centuries earlier. Both renaissances began with a phase of intensive discovery of remote antiquity that was riddled with mistaken assumptions, questionable sources, farfetched conclusions, and claims that today seem utterly ridiculous; yet both produced an explosion of interest in ancient history, art, languages and texts that ended up working wonders for art, philology, and the humanities in general.8 Works like Sinner’s Metempsychosis of 1771, Raynal’s Histoire philosophique of 1773, Voltaire’s Fragmens sur l’Inde of 1774, Herder’s Ideen (1784–91), and Volney’s Ruins of 1791 mark a crucial phase of excited discovery preceding the arrival of the first copies of Asiatick Researches on the European continent. As the works just mentioned illustrate, this was a period when the cradle of humanity made a decisive move from the Eastern Mediterranean region toward India and the Himalayas. Here we will focus on a particularly poignant reflection of this process in Volney’s Ruins: the evolution of the French Orientalist’s image of Buddhism.

Volney’s image of Buddhism evolved in three phases. The first phase is reflected in the early “genealogy of religions” section of The Ruins (Chapter 22) written before the French Revolution. In this first phase, Volney saw Buddhism as an offshoot of Egyptian cults. In the second phase, the “assembly of religions” section of The Ruins (chapters 19–21), Buddhism is portrayed as a pan-Asian religion with a variety of exoteric and esoteric teachings expounded by representatives of various countries. The third phase, stretching over a quarter-century from Volney’s 1795 public lectures to his revisions of The Ruins before his death in 1820, is characterized by his study of new information by British Orientalists and new theories about the identity and history of Buddhism.

In the initial phase, as reflected in the “genealogy of religions” section of The Ruins, all religions including those of Asia still are firmly rooted in Egypt:

And this, O nations of India, Japan, Siam, Thibet, and China, is the theology, which, invented by the Egyptians, has been transmitted down and preserved among yourselves, in the pictures you give of Brama, Beddou, Sommanacodom, and Omito.9 (Volney 1796:271)

However, this view of a connection at the root did not imply identity of the branches. As we have seen in previous chapters, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the idea of an Egyptian “root” gave a feeling of unity to Asian “branches” that is missing from today’s perspective; but this should not be occasion to commit what Montesquieu called the cardinal sin of the historian, namely, to project modern knowledge on the past.

In this section, Volney’s description of Buddhism follows that of Zoroastrianism, which “revived and moralized among the Medes and Bactrians the whole Egyptian system of Osiris, under the names of Ormuzd and Ahrimanes,” and “only consecrated the already existing reveries of the mystic system” (p. 281). In this respect, “Budoism, or the religion of the Samaneans,” appeared to be very similar:

In the same rank must be included the promulgators of the sepulchral doctrine of the Samaneans, who, on the basis of the metempsychosis, raised the misanthropic system of self-renunciation and denial, who, laying it down as a principle, that the body is only a prison where the soul lives in impure confinement; that life is but a dream, an illusion, and the world a place of passage to another country, to a life without end; placed virtue and perfection in absolute insensibility, in the abnegation of physical organs, in the annihilation of being: whence resulted the fasts, penances, macerations, solitude, contemplations, and all the deplorable practices of the mad-headed Anchorets (sic). (p. 282)10

“Brahminism,” which is discussed immediately after this critical portrait of “Budoism,” is “of the same cast” since its founders only refined Zoroaster’s dualism into a “trinity in unity” of Brahma, Shiva, and Vishnu (pp. 282–83). These sections on Buddhism and Brahmanism are followed by Volney’s discussion of Christianity (pp. 283–96), which characterizes the religion as an allegorical worship of the sun and equally links it to Egypt. Volney’s genealogy of religions section (chapter 22 of The Ruins) clearly shows that at this stage he regarded all major religions as developments of ancient Egyptian cults.

The chapter’s separate sections about “Budoism” and “Braminism” show that Volney distinguished these two religions. In the second phase, reflected in the “assembly of religions” section (chapters 19–21), this distinction gains profile. Here he clearly identifies “Budoism” as a single creed holding sway over many Asian countries from Tibet to Japan. It reportedly centers on “one God, who, under various names, is acknowledged by the nations of the East.” They all “agree as to most points of his history” and celebrate events of his life while fundamentally disagreeing on doctrines and practices” (pp. 167–68). Though Volney does not yet use the modern spelling of this religion’s name, the appellations of its “God” leave no doubt as to its identity:

The Chinese worship him under the name of Fôt; the Japanese denominate him Budso; the inhabitants of Ceylon, Beddhou; the people of Laos, Chekia; the Peguan, Phta; the Siamese, Sommona-Kodom; the people of Thibet, Budd and La; all of them agree as to most points of his history; they celebrate his penitence, his sufferings, his fasts, his functions of mediator and expiator, the enmity of another God his adversary, the combats of that adversary and his defeat. (pp. 167–68)

In Volney’s time, the reification of religion took on a whole new dimension when the incomparability of Christianity gradually waned. As Christianity became just another religion and its sacred scriptures came to be seen as examples of Middle Eastern mythography and legend formation, the mechanisms operative in the formation and history of religions gathered interest. Volney’s chapter 22 on the origin and genealogy of religious ideas is firmly rooted in Charles-François DUPUIS’s (1742–1809) new theory that sought to explain “the origin of all cults” (Dupuis 1781, 1795).

All the theological dogmas respecting the origin of the world, the nature of God, the revelation of his laws, the manifestation of his person, are but recitals of astronomical facts, figurative and emblematical narratives of the motion and influence of the heavenly bodies. (Volney 1796:223)

The origin of religious ideas lies thus not in a divine “miraculous revelation of an invisible world” (p. 223) but rather in human observation of nature and primitive ways of understanding and representing it. Human beginnings were not blessed with divine wisdom; rather, as all histories and legends proved, man was savage in an “original barbarous state” (pp. 224, 357) and only gradually “learned from repeated trials the use of his organs” (p. 226). Only after “a long career in the night of history” did he begin to “perceive his subjection to forces superior to his own and independent of his will,” such as the sun, fire, wind, and water (pp. 226–27). Volney traced the process of man’s gradual rise, his representation of the incomprehensible powers of nature through emblems and hieroglyphs, the origin of religious specialists, the beginnings of agriculture, the development of a system of astronomy and almanacs, and eventually the idea of gods as physical beings (pp. 227–35). Like Dupuis, he rejected the Bible-based chronology and voted for significantly longer time spans, as well as Egyptian roots of astronomy and organized religion:

Should it be asked at what epoch this system took birth, we shall answer, supported by the authority of the monuments of astronomy itself, that its principles can be traced back with certainty to a period of nearly seventeen thousand years. Should we farther be asked to what people or nation it ought to be attributed, we shall reply, that those self-same monuments, seconded by unanimous tradition, attribute it to the first tribes of Egypt. (p. 235)

When Volney wrote his genealogy of religious ideas in the 1780s, he still criticized Jean-Sylvain Bailly for placing the cradle of humanity somewhere in Siberia (p. 361). For him, the first humans needed a place “in the vicinity of the tropic, equally free from the rains of the equator, and the fogs of the north” (p. 235). At that time Volney did not doubt that it was “upon the distant shores of the Nile, and among a nation of sable complexion, that the complex system of the worship of the stars, as connected with the produce of the soil and the labours of agriculture, was constructed” (p. 236). It was also in Egypt “at a period anterior to the positive recitals of history” (p. 278) that the “complex power of Nature, in her two principal operations of production and destruction” was first projected into a “chimerical and abstract being,” a development that Volney regarded as “a true delirium of the mind beyond the power of reason at all to comprehend” (p. 277). The ideas of an immortal soul and of transmigration were also linked to this notion of a power of nature or world soul (p. 273), and Egypt thus appeared as the mother of the world’s major religions: “Such, O Indians, Budsoists, Christians, Mussulmans, was the origin of all your ideas of the spirituality of the soul!” (p. 277). Combining ideas from Maimonides’s Guide for the Perplexed about early Sabean sidereal worship with the genealogies of Dupuis and Holbach, Volney envisioned a large tree of religions with Egyptian roots. His genealogy features separate sections for five major branches of this tree: the religions of Moses and Zoroaster, “Budoism,” “Braminism, or the Indian system,” and “Christianity, or the allegorical worship of the Sun.”

One of humankind’s imagined divine beings was Volney’s Buddha. While the “genealogy of religions” section had little to say of his “sepulchral doctrine of the Samaneans” that regards the body as a prison and life as a dream (p. 282), the “assembly of religions” chapters and especially its notes present a later, much more elaborate layer of Volney’s views. As mentioned above, that second layer reflects his views in 1791 after he had studied a range of new sources about Asian religions, and it represents a marked advance over the view expressed in the earlier “genealogy of religions” section of The Ruins. In the “assembly of religions” section (chapters 19–21) that represents the second layer, Buddhism is presented as a pan-Asian religion deeply split by “the dogmas of their interior and their public doctrine” (p. 168). Volney identifies this religion via its central figure of worship and through the similarity of the founder’s biographical details in various countries. He locates Buddhism in China, Japan, Ceylon, Laos, Pegu (Burma), Thailand (Siam), Tibet, and Tartary (pp. 167–69). If Jesus was for Volney a mythological rather than a historical figure, the same was true of the founder of Buddhism. He associates him with Kircher’s “orphic egg” (p. 270; Kircher 1654:2.205):

The original name of this God is Baits, which in Hebrew signifies an egg. The Arabs pronounce in Baidh, giving to the dh an emphatic sound which makes it approach to dz. (p. 345)

According to Volney (who transposed an idea of Henry Lord, Kircher and La Croze into a different key), the “world egg” cosmogony was a major element of Egyptian influence on Asia. During the discussions in the assembly of religions, Volney has a “Lama of Thibet” explain this cosmogony. Volney drew its first part from de Guignes’s History of the Huns (1756:1/2.225–26):

“In the beginning,” said he [the Lama of Thibet], “there was one God, self-existent, who passed through a whole eternity, absorbed in the contemplation of his own reflections, ere he determined to manifest those perfections to created beings, when he produced the matter of the world.” (Volney 1796:205)

The next part of the Lama’s account in The Ruins stems from Henry Lord’s cosmogony of the Banians (1630:2), which, as Volney notes (1796:352), is said to be of Egyptian origin:

The four elements, at their production, lay in a state of mingled confusion, till he breathed upon the face of the waters, and they immediately became an immense bubble, shaped like an egg, which when complete became the vault or globe of the heavens in which the world is inclosed. (p. 205)

Volney’s Tibetan Lama asserts that “God, the source of motion” gave each living being “as a living soul a portion of his substance” that never perishes but “merely changes its form and mould as it passes successively into different bodies” (p. 205). He informs the assembly that God’s “greatest and most solemn incarnation was three thousand years ago, in the province of Cassimere, under the name of Fôt or Beddou, for the purpose of teaching the doctrine of self-denial and self-annihilation” (p. 206). The Lama then reads some excerpts from de Guignes’s translation of the Forty-Two Sections Sutra to the representatives of the world’s religions (pp. 207–8). Volney’s notes leave no doubt that he regarded this founder to be a mythological figure like Zoroaster: “The eastern writers in general agree in placing the birth of Bedou 1027 years before Jesus Christ, which makes him the cotemporary (sic) of Zoroaster, with whom, in my opinion, they confound him” (p. 353).

Based on a variety of ancient sources and stretching de Guignes’s argument, Volney saw Zoroaster as identical with the mythical Egyptian Hermes—which brings also Bedou into the Egyptian fold and is “supported” by a another deathbed confession story:

It is certain that his [Hermes’s] doctrine notoriously existed at that epoch: it is found entire in that of Orpheus, Pythagoras, and the Indian gymnosophists. . . . If, as is the case, the doctrine of Pythagoras and that of Orpheus are of Egyptian origin, that of Bedou goes back to the common source; and in reality the Egyptian priests recite that Hermes, as he was dying, said: “I have hitherto lived an exile from my country, to which I now return. Weep not for me, I ascend to the celestial abode, where each of you will follow in his turn: there God is: this life is only death.” (p. 353)

Additionally, the much-cited coincidence that the day in the middle of the week was associated with Hermes and Buddha (as an avatar of Vishnu) quickly led Volney to the expected conclusion:

Such was the profession of faith of the Samaneans, the sectaries of Orpheus, and the Pythagoreans. Farther, Hermes is no other than Bedou himself; for among the Indians, Chinese, Lamas, &c. the planet Mercury, and the corresponding day of the week (Wednesday) bear the name of Bedou: and this accounts for his being placed in the rank of mythological beings, and discovers the illusion of his pretended existence as a man, since it is evident that Mercury was not a human being, but the Genius or Decan. . . . Now Bedou and Hermes being the same names, it is manifest of what antiquity is the system ascribed to the former. (pp. 353–54)

Inspired by a suggestion of de Guignes, Volney also drew another group into the circle: the shamans of “Tartary, China, and India” who are famous for their mortifications. Their system “is the same as that of the sectaries of Orpheus, of the Essenians, of the ancient Anchorets of Persia and the whole Eastern country” (p. 354). Out of this potent ancient Oriental matrix grew the entire sacred literature:

That is to say, pious romances formed out of the sacred legends of the Mysteries of Mithra, Ceres, Isis, &c.; from whence are equally derived the books of the Hindoos and the Bonzes. Our missionaries have long remarked a striking resemblance between those books and the Gospels. M. Wilkins expressly mentions it in a note in the Bhagvat-Geeta. All agree that Krisna, Fôt, and Jesus, have the same characteristic features; but religious prejudice has stood in the way of drawing from this circumstance the proper and natural inference. To time and reason must it be left to display the truth. (p. 356)

The inference, of course, was that they are all branches of the same myth, as Dupuis had so eloquently suggested. Sacred literature had little religious appeal for Volney, and recent translations from ancient Persian and Sanskrit such as Anquetil-Duperron’s Zend Avesta (1771), the Ezour-vedam (1778), Wilkins’s Bhagvat Geeta (1785), and the Bagavadam (1788) did not impress him:

When I have taken an extensive survey of their contents, I have sometimes asked myself, what should be the loss to the human race if a new Omar condemned them to the flames; and unable to discover any mischief that would ensue, I call the imaginary chest that contains them, the box of Pandora. (p. 351)

As his catechism for the citizen shows, Volney had a rather different idea of religion. But like other Europeans studied in this book, he also projected his own religion on ancient Asia and chose to put at least part of it into the mouth of Buddhist monks. When the participants in The Ruins’s council of religions fail to come to a common understanding after protracted discussions and presentations, “a groupe of Chinese Chamans, and Talapoins of Siam came forward, pretending that they could easily adjust every difference, and produce in the assembly a uniformity of opinion” (pp. 209–10). They explained that they had an elegant way of accounting for differences by calling them “exterior” and could overcome such differences by recourse to an underlying “esoteric” core. Volney explains in a note:

The Budsoists have two doctrines, the one public and ostensible, the other interior and secret, precisely like the Egyptian priests. It may be asked, why this distinction? It is, that as the public doctrine recommends offerings, expiations, endowments, &c. the priests find their profit in teaching it to the people; whereas the other, teaching the vanity of worldly things, and attended with no lucre, it is thought proper to make it known only to adepts. (p. 356)

Volney, the revolutionary sworn to equality and fraternity—and the author of a new law expropriating the French Church—could not but harshly criticize this tactic: “Can the teachers and followers of this religion, be better classed than under the heads of knavery and credulity?” But in his narrative he needed representatives from somewhere to present an atheist viewpoint to the assembly; and who was better equipped for this delicate task than the “Chinese Chamans, and Talapoins of Siam,” the supposed experts of the Buddha’s secret doctrine? The triangular connection between “esoteric” Buddhists, ancient atheists like Epicurus and Lucretius, and modern thinkers accused of the same vice—particularly Spinoza—had long been made by the likes of Jean Le Clerc (1657–1736) and Pierre BAYLE (1647–1706). In The Ruins, Volney thus decided to use these Chinese and Siamese Buddhists as stand-ins for Holbach and himself. He has them explain:

The soul is merely the vital principle resulting from the properties of matter, and the action of the elements in bodies, in which they create a spontaneous movement. To suppose that this result of organization, which is born with it, developed with it, sleeps with it, continues to exist when organization is no more, is a romance that may be pleasing enough, but that is certainly chimerical. God himself is nothing more than the principal mover, the occult power diffused through every thing that has being, the sum of its laws and its properties, the animating principle, in a word, the soul of the universe; which, by reason of the infinite diversity of its connections and operations, considered sometimes as simple and sometimes as multiple, sometimes as active and sometimes as passive, has ever presented to the human mind an insolvable enigma. (Volney 1796:211)

In this way these Buddhists become advocates of a God that very much resembles that of Volney’s work of 1793, the Catechism of the Citizen, which he regarded as the second part of The Ruins. Its first precept is the belief in a natural law inherent in the existence of things, and the second advocates the faith that this law “comes without mediation from God and is presented by him to each human being” (Volney 1826:1.253). This unmediated law becomes apparent when one “meditates on the properties and attributes of each being, the admirable order and harmony of their movements” and thus arrives at the realization that “a supreme agent exists, a universal and identical engine, which is designated by the name of GOD” (1.257). Volney instructs the revolutionary citizen that “the partisans of natural law” [les sectateurs de la loi naturelle] are by no means atheists: “On the contrary, they have stronger and more noble ideas about the divinity than the majority of other people” (1.257). The esoteric Chinese and Siamese monks of The Ruins couch their doctrine in a somewhat different terminology, but there is no doubt that they represent Volney and some of his radical friends when they say,

What we can comprehend with the greatest perspicuity is, that matter does not perish; that it possesses essential properties, by which the world is governed in a mode similar to that of a living and organised being; that, with respect to man, the knowledge of its laws is what constitutes his wisdom; that in their observance consist virtue and merit; and evil, sin, vice, in the ignorance and violation of them; that happiness and misfortune are the respective result of this observance or neglect, by the same necessity that occasions light substances to ascend, heavy ones to fall, and by a fatality of causes and effects, the chain of which extends from the smallest atom to the stars of greatest magnitude and elevation. (Volney 1796:211–12)

Whereas William Jones detected his favorite brand of mystical Neoplatonism in the writings of Kayvanites, Sufis, and Vedantins and came to regard their teachings as vestiges of the purest and oldest monotheism expressed in Vedic prayers (App 2009), Volney found some of the basic precepts of his own revolutionary catechism in the giant heap of superstition that the world calls its religious systems.

When in the mid-1790s his reduced duties as a revolutionary lawmaker left Volney more time for study and he gained access to the first volumes of Asiatick Researches, he realized that he had still been caught in a rather parochial, Bible-influenced and Mediterranean-centered view of origins. In his second public lecture of 1795, the newly elected history professor of the École Normale criticized the so-called universal histories for being partial histories of some peoples and families.

Our European classics wanted to speak to us only of the Greeks, Romans, and Jews: because we are, if not the descendants, then at least the heirs of these peoples with regard to the civil and religious laws, language, sciences, territory; which makes it apparent to me that history has not yet been treated with the universality that is needed. (Volney 1825:7.8–9)