Yesterday’s beautiful utopia will be the morning’s refreshing truth

—CLOSING SPEECH TO THE FIRST COMMUNIST BANQUET, BELLEVILLE, JULY 1, 1840

In The Painting of Modern Life, the art historian T. J. Clark suggests that Haussmann’s reshaping of Second Empire Paris depended critically upon a capitalistic reimagining of what the city both was and could be about. Capital, he argues: “did not need to have a representation of itself laid out upon the ground in bricks and mortar, or inscribed as a map in the minds of its city-dwellers. One might even say that capital preferred the city not to be an image—not to have form, not to be accessible to the imagination, to readings and misreadings, to a conflict of claims on its space—in order that it might mass-produce an image of its own to put in place of those it destroyed.”1 The argument is intriguing, but while Clark makes much of the mechanisms of commodification and spectacle that replaced what went before, he tells us very little about the image or images of the city that got displaced.

Clearly, the romanticism and socialist utopianism that flourished so wildly in the 1830s and 1840s in France were solidly repressed in the counterrevolution of 1848–1851. Many of those active in the swirling social movements that produced the revolution of 1848 were lost to the cause through death, exile, or discouragement. It is undeniable that some sort of shift in sensibility occurred after 1848 in France that redefined what political struggle was about on both the left and the right. Socialism, for example, became much more “scientific” (as Marx insisted), though it was to take a generation before that idea could bear much fruit, while bourgeois thought became much more positivist, managerial, and tough-minded. And for some commentators this is very much what the transition to modernity and modernism was all about. Some markers are needed, however, because the story of what happened in Second Empire Paris is also a more complicated story of exactly what was repressed, destroyed, or co-opted in the counter-revolution of 1848–1851. How, then, did people in general and progressives in particular see and imagine the city and society before 1848? And what possibilities did they foresee for the future? What was it in all of this that the Empire had to work against?

Figure 20 Daumier’s remarkable Bourgeois and Proletarian (1848) captures the distinction that many felt at the time was fundamental. The bourgeois, static and fat, avariciously eyes commodities in the shop window, while the worker, thin and in motion, determinedly scans a newspaper (the workers’ press?) for inspiration.

On October 22, 1848, some eight thousand workers gathered in a Bordeaux cemetery to dedicate a monument, erected by public subscription, to Flora Tristan, who had died in that city in 1844, shortly after publishing her most famous work, L’Union Ouvrière, a vigorous plea for a general union of workers coupled with the emancipation of women. That a pioneering figure in socialist feminism should be the object of such reverence in 1848 might seem surprising. But there is another way to explain its significance. Ever since 1789, the Republic, the Revolution, and most particularly Liberty had been depicted as a woman. This countered a political theory of monarchical governance that, from the late Middle Ages onward, had appealed to the idea of the state and the nation as being constituted out of what Kantorowicz calls “the King’s Two Bodies”—the king as a person and the king as an embodiment of the state and nation.2 During the French Revolution this depiction of the King and the idea “l’état, c’est moi” came in for some radical satirical treatment. Placing the cap of liberty—a Phrygian cap—on the King’s head was a way of signaling his impotence (the droop of the cap bore a resemblance to a nonerect penis). Daumier, a resolute republican, went to prison in 1834 for his savage depiction of Louis Philippe as Gargantua, a bloated figure being fed by impoverished masses of workers and peasants while he shelters a few affluent bourgeois under his throne.

Figure 21 Daumier’s Gargantua (1834) takes the idea of the body politic quite literally, and has a bloated Louis Philippe being fed by an army of retainers while protecting some bourgeois hangers-on beneath his chair. This cartoon earned Daumier six months in prison.

Figure 22 Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People is one of the most celebrated of the depictions of Liberty as a woman on the barricades. While it was meant as a celebration of the “July Days” that brought Louis Philippe to power, it was considered too incendiary for public exhibition, so the King bought it and stored it away.

Agulhon provides a fascinating account of this iconographic struggle throughout the nineteenth century.3 The motif of Liberty and Revolution as woman reappeared very strongly in the revolution of 1830, most effectively symbolized by Delacroix’s painting Liberty Leading the People. A veritable flood of parallel images arose throughout all France in the aftermath of 1848. How the woman was represented was, however, significant. Opponents of republicanism often went along with the representation but portrayed the woman as a simpleton (a “Marianne” from the country) or as an uncontrolled, lascivious woman no better than a common prostitute. Respectable bourgeois republicans preferred stately figures in classical dress and demeanor, surrounded with the requisite symbols of justice, equality, and liberty (an iconographic form that ended up as a French donation to adorn New York City’s harbor (see figure 117). Revolutionaries expected a bit more fire in the figure. Balzac captured this in The Peasantry in the figure of Catherine, who(:)

recalled the models selected by painters and sculptors for figures of Liberty and the ideal Republic. Her beauty, which found favor in the eyes of the youth of the valley, was of the same full-blossomed type, she had the same strong pliant figure, the same muscular lower limbs, the plump arms, the eyes that gleamed with a spark of fire, the proud expression, the hair grasped and twisted in thick handfuls, the masculine forehead, the red mouth, the lips that curled back with a smile that had something almost ferocious in it—such a smile as Delacroix and David (of Angers) caught and rendered to admiration. A glowing brunette, the image of the people, the flames of insurrection seemed to leap forth from her clear tawny eyes.4

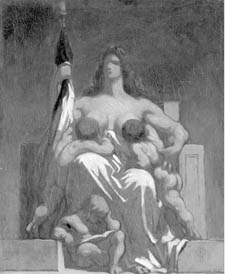

Figure 23 Daumier’s Republic was created in response to the Revolutionary government’s request for new art to celebrate Republican virtues. With two lusty infants suckling at her breasts and another with a book at her feet, Daumier suggests a body politic that nurtures and that takes seriously Danton’s famous saying that “After bread, education is the primary need of the people.”

Flaubert took the negative view. In Sentimental Education he describes a scene witnessed during the invasion of the Tuileries Palace in 1848: “In the entrance-hall, standing on a pile of clothes, a prostitute was posing as a statue of Liberty, motionless and terrifying, with her eyes wide open.”5

It is on this contested terrain that Daumier’s version, painted in response to the Republican government’s invitation in 1848 to compete for a prize representation of the republic, is doubly interesting. For not only is the body politic of the Republic represented as a woman—indeed, it would have been surprising, under the circumstances, if it had not been—but it is also given a powerful maternal rendering. It is a nurturing social republic that Daumier depicts, as opposed to the political symbolism of bourgeois rights or the revolutionary symbolism of woman on the barricades. Daumier echoes Danton’s revolutionary declaration: “After bread, education is the primary need of a people.” This nurturing version of the body politic had become deeply embedded in left socialism and utopian programs during the 1840s.

This imagery of the ideal republic was indissolubly linked with that of the ideal city. “There is,” wrote Foucault, “an entire series of utopias or projects that developed on the premise that a state is like a large city.” Indeed, “the government of a large state like France should ultimately think of its territory on the model of the city.”6 Historically this connection had always been strong, and for many radicals and socialists of the time, the identity was clear. The Saint-Simonians, for example, with their obvious interest in material and social engineering were totally dedicated to the production of new social and spatial forms such as railways, canals, and public works of all kinds. And they did not neglect the symbolic dimension of urban development. Duveyrier’s description of “The New Town or the Paris of the Saint-Simonians” in 1833 “was to have as its central edifice a colossal temple in the shape of a female statue (the Female Messiah, the Mother); it was to be a gigantic monument where the garlands on the robe were to act as so many promenade galleries, while the folds in the train of the gown were to be the walls of an amphitheatre for games and roundabouts, and the globe on which her right hand rested was to be a theatre.”7 Fourier, though primarily interested in agrarian preindustrial communities, had plenty to say about urban design and planning, and constantly complained about the appalling state of the cities and the degrading forms of urban life. With few exceptions, socialists, communists, feminists, and reformers of the 1840s paid attention to the city as a form of political, social, and material organization—as a body politic—that was fundamental to what the future good society was to be about. Hardly surprisingly, this broad impetus carried over into architecture and urban administration, where the imposing figure of César Daly set out to translate ideas into architectural forms and practical projects (some of which were set in motion in the 1840s).8

While the general connection between thinking about the republic and about the city may have been clear, the details were lost in a mess of confusions as to how, exactly, the body politic was to be constituted and governed. From the 1820s onward, groups of thinkers formed, bonded, imploded, or fractured, leaving behind shards of ideas that were picked up and recombined into entirely different modes of thought. Factions and fragmentations, schisms and reconfigurations flourished. Rational Enlightenment principles were combined with romanticism and Christian mysticism, science was applauded but then given a visionary, almost mystical, status. Hard-nosed materialism and empiricism intermingled with visionary utopianism. Thinkers who aspired to a grand unity of thought (like Saint-Simon and Fourier) left behind such a chaos of writings that almost anything could be deduced therefrom. Political leaders and thinkers jostled for power and influence, and personal rivalries and not a little vanity took their toll. And as political-economic conditions shifted, so innumerable adaptations of thinking occurred, making the ideas of 1848 radically different from those of 1830. How, then, are we to understand these turbulent currents of thought?

“Society as it exists now,” wrote Claude-Henri de Saint-Simon sometime in 1819–1820, “is indeed an upside-down world.”9 And, of course, the only way to improve upon things was to set it right side up, which implied making some sort of revolution. Saint-Simon, however, abhorred the violence of the Revolution (he narrowly escaped the guillotine) and preferred to seek pacific, progressive, and rational change. The body politic was sick, he said, and needed resuscitation. But the end result was to be the same: the world must be turned right side up.

This sense of a world turned upside down had, as Christopher Hill (1975) so brilliantly documents, already had its day across the English Channel in the turbulent years 1640–1688 that followed upon Cromwell’s seizure of power and the execution of King Charles.10 Much the same phenomena are to be observed in France between 1830 and 1848, when speculation and experimentation were rife. But how can this efflorescence of utopian, revolutionary, and reformist ideas in the period 1830–1848 be explained? The French Revolution left a double legacy. There was, on the one hand, an overwhelming sense that something rational, right, and enlightened had gone very wrong, as well as a desperate need to come to terms with what (or whom) to blame. In this the historians of the 1840s played a crucial role by building a potent historical analysis and memory of much that had been lost. But the Revolution also left behind the sense that it was possible for “the people” (however construed) to right things by the mobilization of a collective will, most particularly within the body politic of Paris. The revolution of 1830 demonstrated this capacity, and for a short time it seemed as if constitutional monarchy and bourgeois right could march hand in hand, much as they had in Britain after the settlement of 1688, so as to make republicanism irrelevant. But the disillusionment that followed, as the aristocracy of money took over from the aristocracy of position (with a concomitant repression of many constitutional freedoms, such as those of speeech and the press) sparked an eruption in oppositional thinking (symbolized by Daumier’s savage depiction of Louis Philippe as Gargantua). The effect was to revive interest in republican alternatives. But behind this loomed another set of pressing problems—the grinding poverty and insecurity, the cancerous social inequality, and how work and labor might best be organized to alleviate the lot of an oppressed peasantry and a nascent industrial working class more and more concentrated in large urban centers such as Paris and Lyon. And this provoked thought of a socialist alternative, both among the workers themselves and among the progressive intelligentsia.

The legacy of Revolutionary-period thinkers was important. François Babeuf’s “conspiracy of the equals,” for example, had proclaimed economic and political socialism as the inevitable next step in a French Revolution deemed to be “only the forerunner of another revolution, far greater, far more solemn, which will be the last.” Babeuf sought to overthrow the existing social and political order by force (only to be guillotined, on the orders of the Directory, as a martyr to this cause in 1797). Buonarotti, a coconspirator with Babeuf, escaped the guillotine because of his Italian nationality and lived to publish a full (and possibly much embellished) account of the work of the conspiracy in 1828 (leading Babeuf thereafter to be considered, erroneously in Rose’s view, by Marx and Lenin as a pioneering figure in revolutionary communism).11 This was the tradition that August Blanqui resurrected in several conspiratorial schemes, such as the Société des Saisons that sought unsuccessfully to overthrow the July Monarchy in 1839. The oath of this secret society proclaimed that the aristocracy is “to the social body what a cancer is to the human body,” and that “the first condition of the social body’s return to justice is the annihilation of aristocracy.” Revolutionary action, the extermination of all monarchy and aristocrats, and the establishment of a republican government based on equality was the only way to rescue the social body from “its gangrenous state.”12

Blanqui added two specific twists to this argument. When arrested and charged with conspiracy in 1832, he declared his profession before an incredulous President of the Court as “proletarian”—the profession of “thirty million Frenchmen who live by their work and who are deprived of political rights.” In his defense he evoked the “war between rich and poor” and denounced “the pitiless machine that pulverises, one by one, twenty-five million peasants and five million workers to extract their purest blood and transfuse it into the veins of the privileged. The cogs of this machine, assembled with an astonishing art, touch the poor man at every instant of the day, hounding him in the least necessity of his humble life, and the most miserable of his pleasures, taking away half of his smallest gain.” But Blanqui detested utopian blueprints. “No one has access to the secrets of the future,” he wrote. “The Revolution alone, as it clears the terrain, will reveal the horizon, will gradually remove the veils and open up the roads, or rather multiple paths, that lead to the new social order. Those who pretend to have in their pocket a complete map of this unknown land—they truly are madmen.”13 Blanqui did have a transition program. Those who mounted the revolution—for the most part declassé radicals—would have to assume state power and construct a dictatorship in the name of the proletariat in order to educate the masses and inculcate capacities for self-governance. Blanqui, when not in prison, mounted one revolutionary conspiracy after another, instilling fear into the bourgeoisie, most particularly the republicans. Only after the failure of the 1871 Commune did he finally give in, as Benjamin notes, “to resignation without hope.” He tacitly recognized that the social revolution had not, and perhaps could not, keep pace with the material, scientific, and technical changes that the nineteenth century was experiencing.14

Saint-Simon (who died in 1825) and Fourier (who died in 1837) provided quite different grist to the socialist/reformist mill of oppositional and utopian thought. They were key link figures who reflected on the errors of the Revolution while pursuing alternatives. Both of them left behind legacies that aspired to universality (they both compared themselves to Newton) but which were incomplete, often confusing, and therefore open to multiple interpretations.

Saint-Simon is generally credited with being the founder of positivist social science.15 The task of the analyst, he argued, was to study the actual condition of society and, on that basis, recognize what needs to be done to bring the body politic into some more harmonious and productive state. Many of his works were therefore written as open letters, tracts, or memoranda to influential people (the King, diplomats, etc.). It is hard to extract general principles from such sources. His thinking also evolved in a variety of ways from 1802 until his final, unfinished work on the new Christianity (published posthumously in 1826–1827).

The body politic had, Saint-Simon held, assumed harmonious forms in the past (such as feudalism in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries), only to dissolve in contradictions out of which a new body politic should emerge. The seeds of the new were contained within the womb of the old. This historicist view of human evolution influenced many subsequent thinkers (including Marx). The crisis in the body politic in Saint-Simon’s own time derived from an incomplete transition from “a feudal ecclesiastical system to an industrial and scientific one.”16 The French Revolution had addressed the problem of hereditary privileges, but the Jacobins had failed because they sought to impose constitutional and juridical rights by centralized state power. They had resorted to terror and violence to impose their will. “The eighteenth century has been critical and revolutionary,” he wrote, but the nineteenth has to be “inventive and constructive.” The central problem was that the industrial—by whom Saint-Simon meant everyone who engaged in useful productive activity, including workers and peasants, as well as owners of enterprises, bankers, merchants, scientists, thinkers, and educators—were governed by an idle and parasitic class of aristocrats and priests whose mentality derived from the military and theocratic powers of feudalism.

Spiritual power must therefore pass from the hands of priests to those of savants—the scientists and artists—and temporal power to the leading figures among the industrials themselves. The latter’s interest would be to minimize the interventions of government and to devise a least-cost and efficient form of administration to facilitate the activities of the direct producers. The function of government would be to ensure that “useful work is not hindered.” Government by command should give way to effective administration. This system would, furthermore, have to be Europe-wide rather than national in scope (part of Saint-Simon’s current reputation lies in his prescient view of the necessity for a European Union for a peaceful and progressive organization of economic development). “All men will work,” Saint-Simon declared as early as 1803, and it is to the proper organization of production and useful work that we must appeal if the ills of the social body are to be cured. He emphasized individual initiative and liberty, and sometimes appears to echo the laissez-faire ideals of many political economists (such as Adam Smith).

But Saint-Simon is concerned with the exact nature of the political institutions that could maximize individual liberty and promote useful work through collective projects. The principle of association reflective of divisions of labor plays a vital role, though the ideal of a grand association among all industrials (including workers and peasants as well as employers, financiers, and scientists) is frequently invoked. At one point he proposed the formation of three chambers of governance, elected by the industrials—a Chamber of Invention (made up of scientists, artists, and engineers who would plan systems of public works such canals, railroads, and irrigation “for the enrichment of France and the improvement of the lot of its inhabitants, to cover every aspect of usefulness and amenity”); a Chamber of Execution (made up of scientists who would examine the feasibility of projects and organize education); and a Chamber of Examination (made up of industrials who would decide on the budget and carry out large-scale projects of social and economic development).17

The industrials were not construed by Saint-Simon as homogeneous. But he did not accept that the divisions among them would blind them to their common interests or lead them to object to the hierarchy of powers in which educated elites of producers, bankers, merchants, scientists, and artists would take decisions in the name of the ignorant masses (whose education was a primary goal). “Natural leaders” were defined according to technical ability and merit. “Each man will be placed according to his capacity and rewarded according to his work.” Popular sovereignty was not a useful principle of governance because “the people know very well that, except for a few moments of very brief delirium, the people have no time to be sovereign.” But he became deeply concerned with the question of moral incentives. Naked egotism and self-interest were important, but they had to be ameliorated by other motivations if the economy was to realize collective goals. This was the power that Christianity had always promised but never delivered. A new form of Christianity, founded on moral principles, was required to ensure universal well-being as the aim of political-economic projects. “All men should treat each other as brothers,” he argued, and “the whole of society should work to improve the moral and physical existence of the poorest class.”18 With this, Saint-Simon opened the floodgates to millennarian thinking and religious mysticism as a basis for radical change.

How his ideas spread is a complicated story. His immediate followers published a selective (some would say bowdlerized) account of his ideas after his death, and interest flourished after the July Revolution (in which the Saint-Simonians played no active role). There were many well-attended meetings during the early 1830s that garnered support from reform-minded bourgeois and workers, and a movement was launched to educate workers, though, as Rancière shows, many workers had trouble appreciating the motivations and the paternalism involved.19 Almost anyone exercised about the right to work and its proper organization to relieve poverty and insecurity among peasants and workers during the early 1830s was likely to have had some contact with Saint-Simonian ideas. Much of the thinking about alternative urban forms was deeply influenced by this mode of thought (see below). The role of women and religion became controversial issues, however, and the movement soon imploded in a conflict between factions led by a charismatic (and some said hypnotic) Barthélemy Enfantin (with Godlike pretensions) and a less fanatical Saint-Amand Bazard. Thereafter the legacy of influence dispersed in all manner of directions, and much of the movement’s energy dissipated in religious cult activities. Saint-Simonian feminists, however, evolved their ideas (sometimes in contact with Fourierism) on topics such as divorce and the organization of women’s work. They became vocal and strong enough to come in for satirical commentary from Daumier, and they played an important role in 1848.

Some Saint-Simonians took the Christian path, and Pierre Leroux turned to an associationist kind of Christian socialism. Leroux identified individualism as the primary moral disease within the body politic; socialism—and he is generally credited with being the first to coin the term in 1833—would restore the unity of reciprocal relations between the parts and revive the body politic, he argued. But the role of the body politic was not to impress conformity upon everyone; it should, rather, service “autonomously developing individuals who were realizing their felt needs.”20 Others shifted their allegiance to Fourier. Marx absorbed ideas of social scientific inquiry, productivism, historicism, contradiction, and the inevitability of social change from Saint-Simon but turned to class struggle as the motor of historical change. Still others, like the Pereires, Enfantin, and Michel Chevalier, pursued the idea of association of capital and leadership by a scientific-engineering and financial elite. They became major figures within the Second Empire structures of governance, administration, and capital accumulation through large-scale public works (such as the Suez Canal and the railroads).

That this last group were able to evolve in this way in part reflected Louis Napoleon’s engagement with Saint-Simonian ideas.21 Large-scale public works fascinated the Emperor-to-be. As early as the 1840s, while imprisoned at Ham (after an ill-fated attempt to invade and launch a revolution in Boulogne), he studied a proposal by the newly independent Nicaraguan government to build a canal between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans (to bear Napoleon’s name). He also published a pamphlet titled The Extinction of Pauperism. In this he championed the right to work as a basic principle and proposed state legislation to set up associations of workingmen empowered to engage in the compulsory purchase (with state loans) of wastelands. Put under cultivation, he argued, these would provide employment as well as profitable and healthy activity in the production and sale of agricultural products. A rotating fund for repayment of the state loans and the indemnification of landholders would finance the project. Socialist leaders and reformers rallied to his cause and some, like Louis Blanc and George Sand, even visited him at Ham. Employers and economists mocked the proposal and depicted him as an idle and (based on his failed revolution) incompetent utopian dreamer (an image that led many to underestimate his potential when elected President of the Republic in 1848). While his proposals owed something to Saint-Simon, they also smacked of Fourierist influence (as late as 1848 Louis Napoleon was said to be in touch with Fourierist groups and early in the Empire he showed considerable interest in building cités ouvrières on the model of Fourier’s Phalanstères as a solution to the working-class housing problem).

Figure 24 The feminist movement became strong enough in the 1830s and 1840s for Daumier to devote a series to “bluestockings” (women with artistic and literary pretensions), divorcees, and socialist women. In this cartoon the man is accused of trying to prevent the women from going to a public meeting. Rather than punish him, they leave him to wrestle with his guilty conscience.

So what, then, can we say of Fourier himself? An autodidact, he published his foundational work, The Theory of the Four Movements, in 1808. In it, he sought a transition from “social chaos to universal harmony” by appeal to two basic principles: agricultural association and passionate attraction. Even Fourier’s admirers admit that the work is “diffuse and enigmatic” and “a veritable crazy quilt of ‘glimpses’ into the more arcane aspects of the theory, ‘tableaux’ of the sexual and gastronomic delights of Harmony, and critical ‘demonstrations’ of the ‘methodological mindlessness’ of contemporary philosophy and political economy.” Some of Fourier’s arguments (concerning, for example, the copulation of planets) are bizarre, and others so outlandish that it is easy to dismiss him as a crank. A lonely and often beleaguered figure, he produced a mass of writings that did little to clear up the confusions even as they elaborated and deepened his critical understanding of the defects of the existing order. He sought to conceal some of his more outrageous ideas about passionate attraction and sexuality (his defense of what many regarded then, as now, as sexual perversions, for example). After his death this concealment was even more vigorously pursued by the Fourierists, who, under the authoritarian leadership of Victor Considérant, carefully controlled expurgated versions of his writings to shape what became an important wing of the pacific social democratic movement (with an influential newspaper, the Phalanstère). This “became an intellectual and even political force of some significance during the last years of the July Monarchy and the early phases of the 1848 revolution.” But with the crushing of the revolution, many of the leaders, like Considerant, had to go into exile and the movement lost direct influence.22

Fourier mounted a generic attack upon “civilization” as a system of organized repression of healthy passionate instincts (in this he anticipated some of Freud’s arguments in Civilization and Its Discontents). The insidious problem of poverty derived from the inefficient organization of production, distribution, and consumption. The main enemy was commerce, which was parasitic upon and destructive to human well-being. While we may be destined to work, we need to organize it to guarantee libidinal satisfactions, happiness, comfort, and passionate fulfillments. There was nothing noble or fulfilling about grinding away at awful and monotonous tasks, hour after hour. Civilization not only starved millions a year but it also “subjected all men to a life of emotional deprivation which reduced them to a state below that of animals, who at least were free to obey their own instinctual promptings.”23 So what was the alternative? Production and consumption had to be collectively organized in communities called “Phalanstères.” These would offer variety of work and variety of social and sexual engagements to guarantee happiness and fulfillment of wants, needs, and desires. Fourier took immense pains to specify how Phalanstères should be organized and around what principles (he had a very complicated, mathematically ordered description of passionate attractions, for example, which needed to be matched up between individuals to guarantee harmony and happiness).

If Saint-Simon, Blanqui, and Fourier provided the initial sparks, then a host of other writers spread the flames of alternative thought in all manner of directions. The year 1840, for example, saw the publication of Proudhon’s What Is Property; Etienne Cabet’s influential utopian tale, Voyage in Icaria (shortly after his lengthy study of the French Revolution that depicted Robespierre as a communist hero); Flora Tristan’s expose of misery and degradation among the working classes of London in Promenades in London; Louis Blanc’s social democratic text, The Organization of Work; Pierre Leroux’s two-volume study, On Humanity (which explored the Christian roots of socialism); Agricol Perdiguier’s Book of Compagnonnage (which sought reforms within the system of migratory labor); and a host of other books and pamphlets that offered critical commentary on social conditions while exploring alternatives.24 Villermé’s study of the conditions of labor in the French textile industry was being widely read, and Frègier’s dissection of the problem of the Parisian underclass struck fear into the hearts of many bourgeois readers. Romantic writers (Hugo, Lamartine, Musset, Sand) were throwing their support to radical reform and fraternizing with worker-poets, the first organized communist banquet took place in Belleville, a general strike occurred in Paris, and a communist worker tried to assassinate the King. The floodgates were open, and in spite of attempts at repression and police control, there seemed to be no way, short of revolution and counterrevolution, to stem the turbulence.

It is hard to capture the intensity, the creativity and the commonalities within the diversity of radical arguments articulated during these years. But there was widespread agreement on the nature of the problem. A frustrated Flora Tristan in her influential book l’Union Ouvrière (published in 1843) invoked the innumerable commentators who had preceded her:

In their writings, speeches, reports, memoirs, investigations and statistics, they have pointed out, affirmed and demonstrated to the Government and the wealthy, that the working class is, in the present state of things, materially and morally placed in an intolerable condition of poverty and suffering. They have shown that, from this state of abandonment and neglect, it necessarily follows that the greater part of workers, embittered by misfortune, brutalised by ignorance and exhausting work, were becoming dangerous to society. They have proved to the Government and to the wealthy that not only justice and humanity imposed the duty of coming to the aid of the working classes by a law permitting the organisation of labour, but that even general interest and security imperiously recommended this measure. But even so, for nearly twenty-five years, many eloquent voices have been unable to awaken the solicitude of the Government concerning the dangers courted by society in the face of seven to eight million workers exasperated by neglect and despair, among whom a great number find themselves torn between suicide … or theft!25

While Tristan shaped her account to suit her cause, none of her contemporaries would, I think, dispute the general situation she portrayed, even down to the problem of worker suicides, which were by no means uncommon.

The diagnostic, however, varied greatly: civilization and commerce (Fourier), the anachronistic power of aristocrats and priests (Saint-Simon, Blanqui), individualism (Leroux), indifference to inequality, particularly of women (Tristan), patriarchy (Saint-Simonian feminists), property and credit (Proudhon), capitalism and unregulated industrialism (Considérant, Blanc), corruption of the state apparatus (romantics, republicans, and even Jacobins), failure of workers to organize and associate around their common interests (Cabet and the communists). The list goes on and on. And what to do about it, what the aims and goals of transformative social movements should be, was even more confused. The problem of diagnosis and remedy of the ills of the body politic was made more difficult by a common language undergoing rapid and treacherous shifts in meanings. Among the workers, Sewell shows, linguistic shifts played a crucial role in changing political interpretations and actions between 1793 and 1848.26 But there were some common themes. The differences often reflected the specific ways in which ideas about equality, liberty, republicanism, communism, and association got blended together programmatically. The principles laid out by Leroux in 1833 for the Society of the Rights of Man, shortly after his break with the Saint-Simonians, were typical of this genre:

This party unanimously conceives of equality as its goal, of assistance to proletarians as its first duty, of republican institutions as its means, of the sovereignty of the people as its principle; finally it considers the right of association to be the final consequence of this principle and the means of implementing it.27

But what might these individual terms mean?

Everyone agreed inequality was a problem. But if the aim was improvement, then what kind of equality should be striven for, and by what means and for whom? This had, of course, been a contentious issue ever since the Revolution inscribed the word égalité upon its banner. But by 1840, consensus was submerged beneath a welter of different interpretations. Blanqui persisted with a radical Jacobin idea of secular egalitarianism—to be achieved, however, by means of a dictatorship of the proletariat. Again and again speakers at the 1840 communist banquet (with more than a thousand in attendance) asserted that political equality was meaningless in the absence of social equality. Equality of well-being was important to the Saint-Simonians, but the working classes were to be raised up by education, proper governance, and resources assembled thanks to the initiative of a meritorious and technically superior elite of industrials. The health and well-being of the body politic as a whole was more important than the well-being of individuals (a point upon which Leroux broke with the Saint-Simonians and which has sometimes led them to be portrayed as protofascists). The communists and Jacobins wanted equality of empowerment as well as of life chances. But there was very little support among the workers themselves for revolutionary action to overthrow the whole system and put an egalitarian communism in its place; it was more a matter of wanting to be treated as human beings, placed on the same footing as the bourgeoisie, while being accorded a modicum of security and fair remuneration for employment.28 Workers objected, for example, to the patronizing attitude of the petit bourgeois radicals (particularly the Saint-Simonians) who sought to educate them (rather than give them secure jobs), and found this arrogance almost as hard to bear as the indifference of their employers. Agricol Perdiguier, a worker, insisted on exactly this kind of equality: “You should understand that we are not made of any substance less delicate or less pure than the rich, that our blood and our constitutions are in no way different from what we see in them. We are children of the same father and we must live together as brothers. Liberty and equality must be brought together and reign in concert within the great family of humanity.”29

Inequality was also manifested through the subordination of women. In 1808, Fourier argued that “social progress and changes from one era to the next are brought about in proportion to the progress of women towards freedom, and social decline is brought about in proportion to the decrease in women’s freedom.”30 The emancipation of women was a necessary condition for the emancipation of humanity and the liberation of passionate attractions. Enfantin also promoted the emancipation of women (though from a different male perspective), and several women within the Saint-Simonian movement struggled to connect these ideas with actual practices, launching their own journal, La Tribune des Femmes, to debate issues of sexual liberation and women’s equality. While the Fourierists downplayed questions of sexuality and gender, most feminists were soon drawn to Fourier’s ideas. Flora Tristan, for example, considered the right to work for a remunerative wage equal to that of men and the legal right to divorce as by far the most important reforms needed to liberate women from a form of marital bondage that was nothing less than enslaved prostitution. Questions of sexual liberation gradually gave way, however, to arguments about women’s autonomy and right to work as a condition of freedom from male domination. “What we mean when we speak of liberty, or equality,” wrote a contributor to the Tribune des Femmes, “is to be able to own possessions; for as long as we cannot, we shall always be slaves of men. He who provides us our material needs can always require, in exchange, that we submit to his wishes.”

But on this point there arose another barrier (with which we continue to be dismally familiar). “In industry, very few careers are offered to us. Agreeable work is all done by men; we are left only the jobs that hardly pay enough for survival. And as soon as it is noticed that we can do a job, the wages there are lowered because we must not earn as much as men”31 Tristan in no way romanticized (as Sand did) the working-class or peasant woman. Ill-educated, legally deprived, forced into marriage and dependency at an early age, deprived of rights, she learned to become a sharp-tongued harridan, more likely to drive her husband to the cabaret and her children to theft and violence than to establish a domestic hearth capable of giving succor to all (including herself). Tristan appealed to male self-interest: the education and emancipation of women was a necessary condition for the emancipation of the male working class. Proudhon, however, would have no truck with this; the family was sacrosanct, women belonged in the home under the control of men, and that was that.

The dialogue between material and moral egalitarianism, between the right to gain a living wage under conditions of security and to be treated with dignity and respect, no matter one’s position in terms of class or gender, was a complex one. But it is then not hard to see how conceptions of individual dignity and self-worth, deeply embedded in Christian teachings though not in priestly practices, could also be evoked among authors as diverse as Proudhon (in his early years), Tristan, Saint-Simon, Cabet, and many other reformers. To be anticlerical was one thing, but a radicalized Christianity (of the sort that Saint-Simon and Leroux proposed) seemed to many to be part of the answer. Theologies of liberation abounded, as did millenarian thinking and even mystical musings. Not a few leaders either adopted (like Enfantin or even Fourier, who liked to call himself “the messiah of reason”), or had forced upon them (like Cabet), the status of a “new messiah” ready to announce “the good news” and offer a path to social redemption of society’s ills. It was not clear whether equality was to be regarded as a divine gift or as a triumph of secular reason. The romantic poet Lamartine looked to “an industrial Christ” to guarantee the right to work.

One cannot probe far into the literature of the time without encountering the principle of association either as means or as an end of political institutions and actions. But, again, association encompassed a variety of meanings, and it was sometimes defined so narrowly that others downplayed it in favor of some other principle, such as union (Tristan) or community (Leroux). What was at stake here was how the collectivity might be better organized to take care of material wants while creating a milieu suitable for education and personal fulfillment. Fourier certainly saw it this way in his tract Agricultural and Domestic Association, published in 1822, and it was fundamental to his proposal to construct Phalanstères. But Fourier confined his vision to agricultural production (and even then of a horticultural variety), and never adapted his theory of association to industrial settings. Furthermore, for him, the establishment of associations depended either on philanthropic finance or on private investments in stock, the self-organization of the laborers played no part.

For the Saint Simonians the idea of association among the industrials was fundamental, but it operated at two distinct levels. Differentiated interests (particularly those resulting from divisions of labor or of function) within the body politic were to be organized as associations expressive of those interests. Scientists and artists, for example, would have their own deliberative organizations. But these associations had to be embedded in a “universal association” that depended on a class alliance among all the industrials working for the common good, pooling resources, and contributing and receiving according to productivity and talents. It is not hard to see how such ideas could reappear during the Second Empire as principles of organization, administration, credit, and finance with even a limited role for worker associations under the umbrella of imperial power. This ideal of some grand association of interests and of a class alliance that could bridge bourgeois and worker interests retained considerable importance because many radicals (true to their own class origins and perspectives) felt that the workers and peasants themselves were not strong enough or educated enough to initiate action. Cabet in the early 1840s looked for bourgeois support, and only after repeated rejections did he take a separatist road and define a communistic communitarianism as his goal. Leroux likewise looked for bourgeois support (based on Christian values), and received enough of it (primarily from George Sand) to finance his ultimately unsuccessful agrarian commune and printing works in Lussac.

The idea of independent associations formed by the workers themselves had a long history. Repressed after the Revolution, it reemerged strongly in the revolutionary days of 1830 and found immediate support in the work of Buchez, a dissident Saint-Simonian. Buchez objected to the top-down perspective given by principles of universal association, and argued for bottom-up associations of producers with the aim of freeing workers from the wage system and shielding them from the unjust results of competition. From this perspective, factory owners and employers were just as parasitic as the aristocracy and landowners. This idea was later taken up forcefully by Louis Blanc in his influential The Organization of Work, as well as by Proudhon. Blanc, however, saw it as a duty of state power and political legislation to establish and finance the associations and to supervise their management (much as he later insisted upon the state financing of the national workshops in 1848). Proudhon, for his part, wanted the state kept entirely out of it and looked toward a model of self-governance that would turn the workshop into the social space of reform. But his thinking kept shifting, in part because he did not trust associations to solve the problem or workers necessarily to do the right thing. At some points he invokes a strong disciplinary role for competition between workshops, and at others says that not all workshops needed to be organized on associationist lines. Vincent reconstructs his views as follows:

Basically, what Proudhon desired was to organize an interconnected group of mutual associations which would overcome the contradictions of existing society and thereby transform it. This projected social transformation would commence with the organization of small companies of around one hundred workers which would form fraternal ties with one another. These associations would be primarily economic … but also (functioning) as the focuses of education and social interaction. They would, he claimed, set examples for the establishment of similar associations because of their superior moral and economic qualities.… [and] … resolve “the antinomy of liberty and regulation” and provide the synthesis of “liberty and order.” … The decisive function of the association was to introduce an egalitarian society of men producing and consuming in harmony; they would thereby uproot the opposition between capitalist and worker, between idler and laborer.32

This was very different from Fourier’s or Louis Blanc’s vision, though it did have some commonalities with Cabet. But Proudhon worried that associations might stifle individual liberty and initiative, and he never sought to abolish the distinction between capital and labor; he merely wanted to make relations more harmonious and just. Proudhon also recognized that the mutual associations needed money and credit to function. Anxious to turn his ideas into practice, he launched a People’s Bank in the revolutionary days of 1848, only to have it fail almost immediately.

The idea that workers could form their own associations was, however, fundamental and increasingly popular within the various trades. It became a major topic of discussion in republican and worker-based publications. The main difference was between those who wished to keep competition between associations in order to ensure labor discipline and technological innovation and those who looked for eventual monopolistic control of a whole trade. The movement was to culminate in statutes for a Union of Associations in 1849 (largely passed through the efforts of the socialist feminist Jeanne Deroin), which were just about to be put into practice when the leaders were arrested and the movement suppressed. There were, at that time, nearly three hundred socialist associations in Paris in 120 trades with as many as fifty thousand members. More than half of these survived until the coup d’état of 1851 led to their suppression.33

Proudhon was vigorously opposed to community. If “property was theft,” then “community is death,” he argued.34 Many speakers at the 1840 communist banquet viewed communism and community as interchangeable terms, and Proudhon abhorred centralized political power and decision-making. Dézamy, one of the chief organizers of the banquet, wrote out an elaborate Code of Community in 1842, complete with a plan of the communal palace. Industrial parks and noxious facilities were dispersed into the countryside, and gardens and orchards were closer in. The code constituted a whole legal system governing relations within and between communities. Distributive and economic laws, industrial and rural laws, hygienic laws, educational laws, public order, and political laws and laws on the union of the sexes, absent the family, “with a view to preventing all discord and debauchery,” were all specified. These laws were subsumed within a concept of community construed as “nothing other than the realization of unity and fraternity” as “the most real and fully complete unity, a unity in everything; in education, language, work, property, housing, in life, legislation and political activity, etc.”35 To many, like Proudhon, this seemed horribly oppressive.

Dézamy had been a close collaborator of Cabet but broke with him in part over the level of militancy, as well as over the details of how the ideal community might be organized. By the late 1840s, however, Cabet was by far the more influential communist, espousing pacific methods and rather more acceptable forms of community organization in Icaria: “The community suppresses egoism, individualism, privilege, domination, opulence, idleness and domesticity, transforming divided personal property into indivisible and social or common property. It modifies all commerce and industry. Therefore the establishment of the community is the greatest reform or revolution that humanity has ever attempted.”36 Both Proudhon and Cabet, as opposed to Fourier, Enfantin, and Dézamy, advocated traditional family life, arguing that the negative aspects of women’s lives (which Cabet in particular recognized) would largely disappear with the reorganization of production and consumption along communal lines.

Cabet and Proudhon were indefatigable polemicists and organizers, and by the late 1840s the former’s Icarian communist movement had become substantial, drawing support mainly from the working classes as then defined rather than from educated professionals (who tended to be Fourierist or Saint-Simonian in orientation), or from the déclassé radicals who supported Blanqui or the more radical wing of communism. As early as 1842, over a thousand Parisian workers signed the following declaration in Cabet’s newspaper, Le Populaire (whose circulation rose to more than five thousand by 1848):

It is said we want to live in idleness.… That is not true! We want to work in order to live; and we are more laborious than those who slander us. But sometimes work is lacking, sometimes it is too long, and kills us or ruins our health. Wages are insufficient for our most indispensable needs. These inadequate wages, unemployment, illness, taxes, old age—which comes so early to us—throw us into misery. It is horrible for a great number of us. There is no future, either for us or our children. This is not living! And yet we are the producers of all. Without us the rich would have nothing or would be forced to work to have bread, clothes, furniture, and lodging. It is unjust! We want a different organization of labor; that is why we are communists.37

Cabet’s efforts at class collaboration with reform-minded republicans were, however, rebuffed, forcing him to recognize by the late 1840s that his was a workers’-only movement. In 1847 his thinking turned to Christianity, and he suddenly decided that emigration to the United States and the founding of Icaria there was the answer. Johnston surmises that Cabet was not temperamentally able to confront the possibility, as Marx and Engels subsequently did, that class struggle (perhaps even violent forms of it) against the bourgeoisie was the only path to radical progress. In this, Cabet may well have been in tune with much worker sentiment; as Rancière repeatedly shows, the workers writing in their own journals “demanded dignity, autonomy, and treatment as equals with masters without having to resort to undignified street demonstrations.”38 Cabet carried many of his followers with him and thereby, as Marx complained, diverted many a good communist from the revolutionary tasks in Europe. But what also clearly separated Marx from Cabet was the geographical scale on which they envisaged solutions. Cabot could never think much beyond the small-scale integrated community characterized by face-to-face contact and intimacy as the framework within which communist alternatives must be cast.

While the writers of the time criticized many aspects of their contemporary social order, everyone acknowledged that the question of work and of labor was fundamental both to the critique of existing social arrangements and to proposed solutions. Again and again, the degrading conditions that did exist were contrasted with a world that might be. And the belief that labor produced the value which the bourgeoisie appropriated and consumed was widespread. But alternative visions varied widely.

Fourier, for example, saw the solution as a matter of matching variety of work with his elaborate understandings of passionate attractions. The social division of labor would disappear entirely, and work would be equivalent to play. This was probably the least practicable aspect of Fourier’s system, since it probably could happen only in a world devoid of significant industry and then at only the smallest of scales. When something akin to his Phalanstères did come into being, they functioned more as pioneer forms of localized consumer and living cooperatives than as vigorous production enterprises. Nevertheless, Fourier’s insistence that the activity of laboring defines our relation to nature and the inherent qualities of human nature has been a recurrent locus of critique of the labor process under both capitalism and socialism/communism. It continues to echo down to this day. The Saint-Simonians, on the other hand, were prepared to reorganize the division of labor on much larger scales and with an eye to greater efficiency. But this depended upon the administrative and technical skills of an industrial elite who would designate tasks and positions for workers who would be expected to submit willingly to their dictates. The benefit to the workers depended on the moral presumption that everything would be organized to be of greatest benefit to the poorest classes (the parallel with John Rawls’s contemporary theory of justice is interesting).

There was little in Saint-Simonian doctrine to suggest that quality of work experience was important. Almost any kind of labor system, such as those later called Taylorism and Fordism, would be entirely compatible (as Lenin believed) with socialism/communism as well as with capitalism. The Saint-Simonians who became influential during the Second Empire adopted an eclectic stance to the labor question, conveniently forgetting the moral imperative to render justice. Proudhon’s sterling defense of principles of justice in 1858 was designed to highlight this omission. But the “Saint-Simonian vision as well as the subsequent Marxist dream of mechanized socialist mankind wresting a bountiful living from a stingy and hostile environment would have seemed a horrible nightmare of rapine to Fourier, for he knew that the natural destiny of the globe was to become a horticultural paradise, an ever-varying English garden.”39

Models of what much later came to be called worker self-management or autogestion also abounded in the 1840s with Proudhon’s mutualism, Cabet’s communism, and even Leroux’s Christian communitarianism emerging as competing variants. But Proudhon got into all manner of tangles as he sought to come up with a labor numéraire (money notes) to reflect the fact that laborers produced the value and needed to be remunerated according to the value they produced. Proudhon mainly oriented his thinking to the small-scale workshop or enterprise, and was far less comfortable with any attempt to consciously organize large-scale projects that might involve what he considered degrading conditions of detailed divisions of labor. This led him back to accept the necessary evil of competition as a coordinating device, and he tried to put a positive gloss on the anarchy of the market by praising what he at one point called “anarchistic mutualism” as the most adequate social form to allocate labor to tasks in a socially beneficial manner. All of this was to bring a series of scathing responses from Marx after 1848.40

These arguments have, interestingly, been revived in recent years, particularly since the publication of Piore and Sable’s The Second Industrial Divide. They argue that a magnificent opportunity to organize labor according to radically different principles, in small-scale firms under worker control, was lost around 1848, only to appear again with the new technologies that allowed flexible specialization, self-management at a small scale, and the dispersal of production to new industrial districts (such as “the third Italy”) from the 1970s onward. The organizational form that got lost in 1848 was, according to them, largely that proposed by Proudhon (minus his misogyny) rather than those of Fourier, Cabet, Louis Blanc, Saint-Simon, or the communists. Competition was beneficial, and there was nothing inherently wrong with capital ownership and dependency on institutions of credit, provided these could be organized along “mutualist” lines. Had this transpired in the mid-nineteenth century, we would, they argue, have been spared the disasters that flowed from the factory system organized by large-scale (often monopoly) capital and the equally miserable factory systems of communism.

This has been a controversial argument, of course, both historically and today. Piore and Sable shunted aside the problem that what might be attractive to labor about flexible specialization might also provide abundant opportunities for irresponsible and decentralized forms of subcontracting and flexible accumulation on the part of capital. That the latter is the dominant story in the recent history of capitalism seems to me undeniable and, as we shall see, industrial organization in Second Empire Paris avidly exploited small-scale structures of subcontracting more than large-scale factories (see chapter 8).41 But by the same token, it also has to be admitted that the Saint-Simonian and Marxist solutions have been found wanting. The labor question, as debated in France in the 1840s, placed a whole range of issues on the table that still need to be addressed. And if we can hear echoes in today’s anti-globalization movements of Proudhon’s mutualism, Leroux’s Christian communitarianism, Fourier’s theories of passionate attraction and emancipation, Cabet’s version of community/communism, and Buchez’s theories of associationism, then we can derive some historical lessons from France in the 1840s at the same time that we can deepen our grasp of the key issues involved.

It was in the banner year of 1840 that the twenty-nine-year-old engineer/architect César Daly launched his Revue Générale de l’Architecture et des Travaux Publics, a journal that was to be a central vehicle for discussion of architectural, urban design, and urbanization questions for the next fifty years or more.42 In introducing the first issue, Daly wrote:

When one recalls that it is engineers and architects who are charged to preside over the constructions that shelter human beings, livestock and the products of the earth; that it is they who erect thousands of factories and manufacturing establishments to house prodigious industrial activity; who build immense cities furnished with splendid monuments, traversed by straightened rivers encased in cyclopean walls, basins carved out of rock, and docks which harbor entire fleets of ships; that it is they who facilitate communications between peoples by the creation of roads and canals, who throw bridges over rivers, viaducts across deep valleys, pierce tunnels through mountains; that it is they who take the surplus waters from low and humid places to spread them over arid and sterile lands, thereby allowing of an immense expansion of agricultural lands, modifying and improving the soil itself; it is they who, undeterred by any difficulty, inscribe everywhere in the land through durable and well-made monuments testimonials to the power of genius and the works of man; when one reflects on the immense utility and the absolute necessity of these works and the thousands to whom they give employment, one is naturally led to appreciate the importance of the science to which we owe these marvelous creations and to feel that the slightest progress in these matters is of interest to all the countries of the globe.43

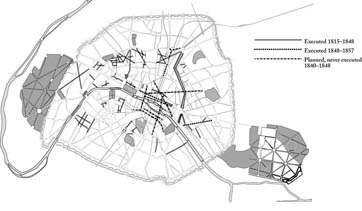

Figure 25 The new road systems realized and proposed during the 1840s.

The tone is Saint-Simonian, which is, on the surface, somewhat odd, given that Daly had been very much influenced by Fourier. The Revue often merged the Saint-Simonian penchant for large-scale public projects and the Fourierist insistence that they be articulated according to well-reasoned, “scientific,” and harmonic (i.e., Fourierist) principles. Considérant, the leading Fourierist of the time, contributed to the Revue, and his occasional collaborator Perreymond (whose actual identity is not known) wrote an extraordinary series of articles on the need to reorganize the interior space of Paris.

Most of the administrators, thinkers, and writers of the period had something to say, either directly or indirectly, about the urban question. They had to, because it was too obvious and too pressing an issue to be avoided. The up and coming Adolphe Thiers took on the Ministry of Commerce and Public Works in 1833, and spent a good deal of time and money on monumental projects and getting bills passed to finance canals, roadworks, and railways. His main contribution, for which he was roundly criticized, was to spend vast sums on the new system of fortifications to protect Paris from invasion. Thirty-five years later, in an odd twist of fate, he had to break through those same fortifications in order to crush the Paris Commune. The prefect of Paris, Rambuteau, set about devising and implementing plans to improve communications (including the street that still bears his name). Urban health and hygiene became a big issues after the devastating cholera epidemic of 1832. And the architect Jacques Hittorff was busy designing the Place de la Concorde and several other projects that animated the drift of the center of Paris toward the north and west. This drift, largely impelled by speculative building (of the sort that Balzac describes around the Madeleine in César Birroteau) was creating a new Paris to the north and west of the overcrowded and congested center. Lanquetin, an ambitious businessman who headed up the City Council in the late 1830s, commissioned a plan for the revitalization of Paris that was far-reaching as well as fiscally ambitious. This was not, therefore, a period of inaction. What Pinon somewhat inaccurately calls “the utopians of 1840” pressed a number of concrete plans for reordering the city streets, some of which were actually realized (see figure 28).44 The difference between this activity and Haussmann’s was twofold. First, there was little in the way of grand vision at the metropolitan scale incorporated into practices (as opposed to ideas). The clearances were piecemeal and the scale of action cautious. Second, Rambuteau was reluctant to exceed the city’s budget; fiscal conservativism was the rule, and Rambuteau was proud of it.

There was, however, no shortage of ideas. Most of the grand thinkers of the period had something to say about the urban question. Fourier’s first encounter with Paris in the 1790s, with “its spacious boulevards, its handsome town houses and its Palais Royal had inspired him to devise the ‘rules’ of a new type of ‘unitary architecture’ which was later to become the basis for the blueprints of his ideal city.” As early as 1796 he had been “so struck by the monotony and ugliness of our modern cities” that he had conceived of “the model of a new type of city,” designed in such a way as to “prevent the spread of fires and banish the mephitism which, in cities of all sizes, literally wages war against the human race.”45 And by 1808 he clearly saw “the problems of urban squalor and cut-throat economic competition as symptoms of a deeper social sickness.” But his alternative designs for urban living, elaborated over the years, were far more suited to an agrarian horticultural society with internalized production and consumption, and harmonized sexual relations, than they were to industrial activities and the extensive networks of trading relations arising out of improved communications in the Paris of the time. Benjamin suggests that “Fourier recognized the architectural canon of the phalanstèry” in the arcades. But there are, Marrey notes, reasons to doubt this.46 The arcades were mostly built before the 1830s as ground-level commercial spaces; Fourier’s analogous spaces were residential and on the second floor, and more likely modeled on the long galleries in the Louvre and at Versailles. Fourier made no explicit mention of the arcades until the 1830s. The Phalanstère did, however, prove influential within the history of urban design, though not necessarily in the way that Fourier thought of it. It provided an architectural prototype (once modified and stripped of many of its social features, particularly those pertaining to sexual and social relations) for various experiments by industrialists with collective and cooperative living arrangements, such as the cités ouvrières tried out in the early years of the Second Empire. But the Phalanstère did not offer an alternative urban plan for restructuring the urban body politic as a whole. Fourier’s schemas were too freighted with nostalgia for some lost past and too small-scale to offer tangible help for reconstruction of a city like Paris.

The same difficulty arose with many of the other thinkers of the time. While Proudhon showed occasional glimpses of being able to think bigger (witness his intuition that much depended upon the restructuring of credit institutions), he never really escaped the scale of the artisan workshops of Lyon that inspired much of his thinking. Leroux (expectedly) and Cabet (disappointingly) got no further than experiments with small-scale communities. Cabet’s efforts turned out to be as disastrous in practice when founded in America as they were in theory. The communists showed some signs of being able to think bigger. Dézamy’s urban code diverged from Fourier’s in part because he emphasized collective property rights and radical egalitarianism, but also because he proposed the communal organization of both work and living within a system of territorially organized communes in fraternal communication and support of each other. Industrial armies would “carry out immense work projects of culture, afforestation, irrigation, canals, railroads, embankments of rivers and streams, etc.” Careful attention would be paid to matters of health and hygiene, and the communes should be situated in locations most suited to health.47 In addition to zoning codes to assure rational land uses in relation to human health and well-being, the communes should be administered and regulated in such a way as to provide equal education, sustenance, and nurture to everyone. Here, indeed, was a complete body politic on an extensive if not large scale, which incorporated the best of Cabet and Fourier in combination with the principles of Babeuf and Blanqui and the administrative ideals of Saint-Simon. But what rendered so much of this utopian and nostalgic was a fierce attachment to the ideal of small, face-to-face communities.

There was a disjunction, therefore, between the rapidly transforming realities of urban life and many of these utopian plans. There were exceptions, however. Saint-Simon had appealed to the leading industrialists and scientists to take matters in hand, and to the polytechnicians and engineers who had the know-how to rethink the city at the requisite scale. He also insisted that the seeds of any alternative must be found in the contradictions of the present. And although Saint-Simonians dispersed and dissipated their energies as a coherent movement in the early 1830s, their ideas had wide currency among a technical elite of financiers, scientists, engineers, and architects (as Daly’s statement illustrates). The reforms envisaged by others were on such a small scale that they could never aspire to anything more than a localized radicalization of social relations, of working and living conditions in the city. Either that, or they were conceptualized as new communities to be constructed in “empty” spaces such as the Americas (Cabet) or the colonies (Algeria, then in course of occupation, frequently featured in discussions; Enfantin, still considering himself the father of the Saint-Simonian movement, wrote a detailed book on plans for the colonization of Algeria along Saint-Simonian lines in 1843).

The big exceptions were the Fourierists, Considérant and Perreymond, who in effect scaled up Fourier’s ideas of harmony and passionate attraction to merge with Saint-Simonian thought. Both considered the railroads as they were then being built to be destructive of human interests and a primary agent in the degradation of the human relation to nature. They were not opposed to improvements in communications, but objected that they were being implemented in an irrational way; that they promoted increasing centralization of power and capital among a financial elite in the large cities; that they operated to stimulate industry and urban development rather than the all-important agriculture; and that the penchant for the “straight line” was being superimposed upon a sensually more satisfying relation to nature. They proposed the nationalization of the rail network and its construction according to rational harmonic (i.e., Fourierist) principles and without resort to private capital. The government was impressed, and produced a national charter for railroad construction, but centered it radially on Paris and inserted a clause that allowed of private exploitation. Interestingly, Benjamin cites Considerant’s objections to the railways at some length but ignores his positive suggestions.48

Considérant and Perreymond likewise offered extensive arguments for the thorough amelioration of Paris’s problems, and did so in a way that was practical and plausible enough to avoid the charge of vacuous utopianism. The most systematic consideration of this question was given by Perreymond in a series of articles beginning in 1842, titled “Studies on the City of Paris.”49 The chaos, disorder and congestion that beset the city center, the lack of harmonious relations between the parts, and the drift of activity toward the north and west was the main focus of concern. Perreymond produced a careful and empirically grounded diagnostic of the situation and then appealed to Fourier’s scientific principles to come up with a solution. He argued that the city must return to its traditional center and then be linked outward to its many growing parts in a coherent and harmonious way. This entailed a radical restructuring of internal communications within the city (including a better positioning of rail access and the building of boulevards), but just as important was a complete reconstruction of the city center. He proposed that the left branch of the Seine be covered over from Austerlitz to the Pont-Neuf and the space used to bring together commercial, industrial, administrative, religious, and cultural functions in a rejuvenated city center that would also depend on the total clearance of properties from the Ile de la Cité.

Perreymond provided engineering specifications and financial calculations to prove the feasibility of his project. He was prepared for debt financing and was critical of Rambuteu’s fiscal conservativism. Here was a plan every bit as daring and ambitious as anything that Haussmann was later to devise. When taken together with proposals on the railways, it effectively addressed the issue of the role and structure of the Parisian metropolitan space in relation to the national space. It was by almost any measure modernist in tone but the big difference from Haussmann is that Perreymond eschewed appeal to the circulation of capital and private speculation in land and property. He insisted that state interventions should work to the benefit of all rather than for a privileged elite of financiers. Probably for that very reason this grand but practical plan was never seriously discussed.

Similarly far-reaching proposals came from Meynadier, whose book Paris Pittoresque et Monumentale was published in 1843. Like Perreymond, Meynadier insisted on the revitalization of the city center by clearances and by the construction of a much more rational system of roads to integrate with the rail system. His detailed plans for new boulevards in many ways anticipated, as Marchand points out, Haussmann’s proposals (particularly given his advocacy of the straight line).50 The clearance and replacement of insalubrious dwellings was also considered a priority, particularly in the old city center. Meynadier was deeply concerned with questions of health and hygiene, and also pushed very hard on the idea of a park system for Paris to rival that of London. And if access to the rejuvenating powers of nature was not to be available within the city, then the suburbs and the countryside could provide a restful alternative if access was created. Balzac’s pastoral fantasy could be realized in the form of the little house in the country. In many respects, Haussmann realized in practice in the 1850s much of what Meynadier had earlier proposed.

Considérant, Perreymond, Meynadier, and even Lanquentin, produced practical plans rather than utopian ideals, even though their thinking was animated by Saint-Simonian and Fourierist ideas. It is against the ferment of this kind of thinking that we have to read what Haussmann actually did. He did not begin from scratch, and owed an immense debt to these pioneering ways of thought (he surely read Daly’s Revue). The problem for him was that these ideas arose out of political presuppositions and utopian dreams that were in many respects anathema to Bonapartism. Hence the myth that Haussmann propagated of a radical break. That much of what he did was already present in embryo in the 1830s and 1840s does not, however, detract from the fact that modernity, as argued in the introduction, entered a new and distinctive phase after 1848 and that Haussmann contributed immensely to how this new form of modernity was articulated.

The world did not get turned right side up in 1848. The socialist revolution failed, and many of those who had been engaged in its production were sidelined, exiled, or simply repressed after the coup d’état of December 1851. The counterrevolution that set in after 1848 had the effect of turning upside down many of the hopes and desires, and reining in the proliferating sense of possibilities, that had been so fulsomely articulated in the 1830s and 1840s. For what really clashed on the boulevards in June of 1848 were two radically different conceptions of modernity. The first was thoroughly bourgeois. It was founded on the rock of private property and sought freedoms of speech and of action in the market, and the kind of liberty and equality that goes with money power. Its most articulate spokesman was Adolphe Thiers, who would have been perfectly content with a constitutional monarchy if the monarch had not perverted matters. Thiers, who had been a minister in the 1830s, was certainly willing to step in to try to save the monarchy in the February days of 1848. He then became the guiding light for the so-called “Party of Order” that emerged in the National Assembly after the elections of April 1848, and avidly sought to guide national policy toward the protection of bourgeois rights and privileges.