The Commune was therefore to serve as a lever for uprooting the economical foundations upon which rest the existence of classes, and therefore of class rule.

—MARX

Individuals develop allegiances broader than those given by the individualism of money and loyalty to family and kin. Class and community define two such broader social configurations. There is a tendency in modern times to see these as mutually exclusive categories that give rise to antagonistic forms of consciousness and political action. This plainly was not so in Paris, neither before (see chapter 2) nor during the Second Empire. That many felt at home with the idea that there was a community of class as well as a class of community was not an ideological aberration; it had a real material base. What was perhaps more surprising was the way many evidently felt not only that community and class provided compatible categories and identities, but also that their synthesis was the ideal toward which any progressive civil society must strive. This was the basic idea of communism in the 1840s, and the idea of association—so fundamental within the workers’ movement and in the ideals of Saint-Simon that underlay the practices of finance capital—either ignored or unified the distinction. Yet it was also true that the conceptions and realities of both community and class underwent a very rapid evolution as the Second Empire progressed. Haussmann’s works and the transformation of the Parisian land and property market upset traditional notions of community as much as they upset the socio-spatial structure, and transformations in financial structures and labor processes had no less an impact upon the material basis of class relations. It is only in terms of such confusions that the extraordinary alliance of forces which produced the Paris Commune—the greatest class-based communal uprising in capitalist history—can be fully appreciated.

Figure 80 Daumier used the class distinctions set up on the railways to explore the physiognomy of classes.

To put things this way is, of course, to invite controversy. Gould rejects the idea that class had anything to do with the Commune. It was, he says, a struggle to gain municipal liberties in the face of an oppressive state, and therefore purely communitarian in inspiration. There have, over the years, been many such attempts to “municipalize” the revolutionary tradition in France.1 Cobb, to take one well-known example, disputed Soboul’s class-driven account of 1789, and Castells, abandoning his earlier Marxist-inspired formulations, interpreted the Commune as an urban social movement in The City and the Grassroots. And there are, in addition, numerous books, such as Ferguson’s, which so highlight the revolutionary tradition of the city as to turn it into a social force that in and of itself played a critical role in political and cultural change. Against this, I shall argue that there had long been local, neighborhood, and even communitarian identifications of class. Those Marxists who refuse to acknowledge the importance of community in the shaping of class solidarities are seriously in error. But by the same token, those who argue that community solidarities have nothing to do with class are similarly blinded. Signs of class and of class consciousness are just as important in the living space as in the working space. Class positioning may be expressed through modes of consumption as well as through relations to production.

Daumard’s reconstruction of the fortunes left by Parisians in 1847 yields a vivid picture of the distribution of wealth by socioeconomic category (table 8).2 Four major groupings stand out. At the top sat the haute bourgeoisie of business (merchants, bankers, directors, and a few large-scale industrialists), landed gentry, and high state functionaries. Accounting for only 5 percent of the sample population, they had 75.8 percent of the inherited wealth. The lower classes (constituting the last four categories) made up three-quarters of the population but collectively accounted for 0.6 percent of the wealth. Between lay an upper middle class of civil servants, lawyers, professionals, and upper management combined with pensioners and those living off interest. Shopkeepers, once the backbone of the middle class, were, as we have already noted, on the way down the social scale (with almost the same proportion of the population, their share of wealth fell from 13.7 percent in 1820 to 5.8 percent by 1847). But they still were a notch above the lower middle class of employees and lower-level managers (mainly white-collar) and the self-employed (mainly craft workers and artisans). The disparities of wealth within this class structure were enormous.

Table 1 Inherited Wealth by Socioprofessional Categories, 1847

| Category | Index of Average Value of Wealth per Recorded Death | % Leaving No Wealth | % of Recorded Deaths | % of Total of Wealth |

| Business (commerce, finance, etc.) | 7,623 | 26.3 | 1.0 | 13.8 |

| Land and property owners | 7,177 | 8.6 | 3.7 | 54.0 |

| High functionaries | 7,091 | 13.0 | 0.6 | 8.0 |

| Liberal professions and managers | 1,469 | 39.4 | 2.0 | 5.6 |

| Middle functionaries | 887 | 16.9 | 1.7 | 3.2 |

| Rentiers and pensioners | 709 | 38.2 | 5.7 | 8.3 |

| Shopkeepers | 467 | 35.7 | 6.1 | 5.8 |

| State and private employees | 71 | 52.8 | 2.7 | 0.4 |

| Home workers | 61 | 48.5 | 1.8 | |

| 0.2Clergy | 15 | 75.9 | 0.4 | 0.1 |

| Domestics | 13 | 81.6 | 6.9 | 0.2 |

| Withous attribution (and Diverse) | 4 | 79.2 | 29.1 | 0.1 |

| Workers | 2 | 92.8 | 30.2 | 0.2 |

| Manual laborers | 1 | 80.5 | 8.1 | 0.0 |

| All categories | 503 | 72.6 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

I have combined certain minor categories from differently constructed tables without, I think, violating the overall picture.

Source: Daumard (1973), 196–201.

We can look at this class structure another way. To begin with, what Marx called “the old contrast between town and country, the rivalry between capital and landed property” is very much in evidence. The disproportionate presence of rural gentry and state functionaries is directly connected with the centralized role of Paris in national life. The peasant class is not actively seen, but its presence is everywhere felt, not only as the reserve of labor power upon which Paris could draw, but also as the source of the taxes that supported government and the unearned incomes that the property owners spent so liberally. When we add in pensioners and rentiers (living off interest), we find nearly a tenth of the population of Paris, controlling more than 70 percent of the wealth, lived off unearned incomes. Here lay much of the enormous effective demand that Parisian industry was so well placed to satisfy. The dominance of the “idle rich” or “consuming classes” had tremendous implications for Parisian life, economy, and politics, as did the overblown role of state functionaries. We find only a fifth of the haute bourgeoisie engaged in economically gainful activities. This had a great effect on the comportment of the bourgeoisie, its social attitudes, and its internal divisions.

The internal divisions within the mass of the lower class (74.3 percent in Daumard’s 1847 sample) are harder to discern. The differences between craft, skilled, unskilled, casual, and domestic laborers were obviously relevant, though Poulot later preferred distinctions based on attitudes toward work, and work skill and discipline (table 9). Contemporaries often dwelt (with considerable fear) on that most contentious of all social divisions: between the laboring and the “dangerous” classes. Before 1848, much of the bourgeoisie lumped them together.3 The workers’ movement of 1848 defined a different reality without totally dispelling the illusion. But it left open how to classify the miscellaneous mass of street vendors, ragpickers and scavengers, street musicians and jugglers, errand boys and pickpockets, occasional laborers at home or in the workshop. For Haussmann, these were the “true nomads” of Paris, floating from job to job and slum to slum, bereft of any municipal sentiment or loyalties. For Thiers, they constituted the “vile multitude” who saw the erection of barricades and the overthrow of government as pure theater and festival. Marx was hardly more charitable. The “whole indefinite, disintegrated mass” of “vagabonds, discharged soldiers, discharged jailbirds, escaped galley slaves, swindlers, mountebanks, lazaroni, pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers, maquereaux, brothel keepers, porters, literati, organ grinders, ragpickers, knife grinders, tinkers, beggars,”—“scum, offal, refuse of all classes”—made up a lumpenproletariat, an important support for Napoleon’s coup d’état.4

Table 1 An Abbreviated Reconstitution of Poulot’s Typology of Parisian Workers, 1870

| True Workers | Workers | Mixed Workers | Simple “Sublimes” | True Sublimes | “Sons of God” and Sublimes of Sublimes | |

| Work habits and skills | Skilled workers, not always as capable as the “sublimes”—they agree to everything the owner demands in order to win promotion. They work nights and Sundays willingly, and never absent themselves on Mondays. They cannot be diverted from their duties by comrades, friends, or family. | No more reasonably skilled, but willing to work nights and Sundays, and never absent themselves on Mondays. They are motivated solely by monetary gain. | Least skilled, and incapable of supervising anyone. They simply follow the flow of the rest and will sometimes take Mondays off with them. | Skilled workers, capable of directing a team, but often see “ripping off” the boss as a duty. Will quit work rather than submit to strict discipline, and therefore move a lot from master to master. Always take Mondays off and refuse Sunday and nightwork. | Elite workers of exceptional skill and indispensable to the point where they can openly defy their bosses without fear of reprisal. often earn a living working only 3 ½ days a week. | The most able to direct production teams with great personal influence over others. They organize collective resistance to the bosses and dictate rhythms of work. The sublime of sublimes never submits to workshop discipline, works at home, but is the “prophet of resistance” within the workforce. |

| Drink and society | Of an “exemplary sobriety.” They never get drunk and control their bad humor or sadness by keeping it to themselves. They seek consolation in work. They refuse the camaraderie of the workshop and are often rejected by their workmates for that reason. | The get “pickled” occasionally, but usually at home on Sundays. They rarely drink with workmates because their women would not permit it. | They get drunk most often at home but also with workmates, and celebrate paydays, Monday mornings, and collective events. | Lose at least one day every two weeks through drinking and are often drunk on Saturdays and Mondays, but spend Sunday with their families. | Truly alcoholics. Unable to function in or out of the workplace without eau-de-vie. | Get drunk only on feast days and withfriends and family. They love to drink and discuss politics, and can get drunk more on the politics than the drink. |

| Life before marriage | They prefer professional prostitutes rather than seduction, and marry without practicing concubinage. | They sleep around with laundresses, domestic servants, etc. and thereby avoid the cost of rent or having to live in with the masters. When they marry, they often desert their mistresses and look for a good housekeeper from their native region. | They are either celibate in rooming houses or marry a shrewish wife … or pass to “sublimism.” | They are either celibate, living in rooming houses, or in concubinage. They marry to make sure they have children to look after them in old age. | They guard their freedom jealously and live alone or in free union. They marry only to have children to care for them in old age. | Play “Don Juan” until their late 30s, and seduce with ease the wives and daughters of workers on their team. Marry late and to ensure children to care for them in old age, but often live in free union. Wives usually also work. |

| Economic condition | They are the most well off, have savings, and participate in mutual benefit societies from which they try to exclude the “sublimes.” Their wives are often concierges or small-scale retailers. | They sometimes have some surplus money to pay off their debts. Their wives are often concierges or small-scale retailers. | They have permanent difficulties making ends meet. | In permanent economic difficulty and live from day to day. Frequently in debt, they make a virtue out of not paying off debts. The wives are usually workers also. | Always in economic difficulty and lack the resources to support a family, even though the companion usually works, too. | Not in so great difficulty but make it a point of principle not to pay off debts to retailers or landlords. |

| Family life | They act as heads of households, regard their women as inferior by nature. They put strong barriers between their family and work life. | The wife usually manages the household and often controls the friendships and behaviors of the husband. | The wife is a rough policewoman feared by her mate. She has a tight hold on the purse strings and is the main barrier between the worker and “sublimism.” | If the wife has “bourgeois” attitudes, there is a lot of conflict. If she does not work, she has to resort to welfare to survive. Wives who work tend to share the men’s attitudes toward bosses and work, and express their solidarity openly. | If the wife is not also a sublime, there is permanent conflict with a lot of violent and drunken beatings and brawling. If the wife is a sublime, there is common understanding in the midst of many rows. The wife will “take to the streets” and is proud to so support the children at the expense of the exploiters. | The woman companion asserts more and more control as the man grows older and loses vigor. |

| Politics | True democrats, they are against both the Empire and socialism. They share Proudhon’s views on “just aspirations to ownership” and look to association between capital and labor. They read the republican opposition journals, rarely attend political meetings, and disapprove of utopian schemes and worked demagoguery. They defend the Republic and are scorned by socialists. | They do not really understand socialist rhetoric and reject the more advanced ideas. They like to go to public meetings, where they can be persuaded by the demagogues. | They follow the ideas of the “sons of God—and read what they recommend. They often go to the public meetings and defer entirely to the ideas of the the leaders. | They reflect on socialism every payday and consider themselves exploited by bosses and landlords, who are considered thieves. They sometimes go to public meetings, nearly always with a “son of God.” | They rarely talk politics, never read or go to public meetings, but listen very attentively to the commentaries of the “sons of God.” | Read the press daily and offer profound commentary on politics, to which others listen with respect. They dream of solutions to the social problem, are against Proudhon, and animate the workers’ movement. Prepared for martyrdom. The sublime of sublimes is more reflective, a “man of principle” who acts as prophet and guru to the workers’ movement. Prepared to do battle against the Republic, they are the most respected orators at meetings. |

Corbon, a contemporary observer, tried to take some of the drama out of the contrasts.5 The “useless class” accounted for only a fifth of the lower classes, and many of them, like the ragpickers, were so impoverished as to be both passive and “inoffensive” (except for the sight of their poverty); they were not socialized to regular labor, produced and consumed almost nothing, and lacked intelligence, ambition, or concern for public affairs. The “vicious” group among them might be shiftless and perverse, but again had to be distinguished from the minority of truly offensive “dangerous classes” made so much of in the novels of Hugo, Sue, and Balzac, and given such political prominence by analysts as diverse as Thiers and Marx. Then, as now, the question of how to define “marginality” or the “informal sector” and its economic and political role was contentious and confusing. Given the insecurity of employment, the boundary between the “street people” and the workers must have been highly porous. The large number of women trapped in poverty and forced to make a living off the street also gave a strong gender component to the actual constitution of this lowest layer in the population (and, as we will later see, compounded sexual fears with fear of revolution). The street people—living off rather than in the city—were, however, a vital force in Parisian economy, life, and culture.

The boundary between these lower classes and the socioeconomic groups that lay above them was also confused and rendered porous by social and economic insecurity. Hugo remarked, for example, on “that indeterminate layer of society, sandwiched between the middle and lower classes, which consists of riff-raff who have risen in the world and more cultivated persons who have sunk, and which combines the worst qualities of both, having neither the generosity of the worker nor the respectable honesty of the bourgeois.”6 Many shopkeepers (whose aggregate position, we have seen, was in strong decline) were close to this margin of survival. Locked in a network of debt, they were forced to cheat, scrimp, and cut corners in order not to lose the little they had built up out of a lifetime of hard work. Ruthlessly exploiting the people they served, they could also latch onto revolution in the hope for economic improvement. Many of the workshop owners were in a similar position. There were few large-scale factories in 1848, so the material conditions for the direct confrontation between capital and labor in production were not powerfully present. The distinction between workers and masters in the small-scale workshops that dominated Parisian industry was often ill-defined, and they worked closely enough together for bonds of sympathy and cooperation often to be as strong as daily antagonisms.7 Both resented the new mass-production techniques and the “confection” system of subcontracting, and felt as oppressed by the power of high finance and commerce as they were angry at and envious of the idle rich—who, in return, as Poulot complained, looked upon those who worked with their hands for a living with equal measures of disgust and disdain. An often radical petite bourgeoisie of small masters, threatened by new production processes and indebtedness, was much more important for Parisian political life than any class of capitalist industrialists.

The bourgeoisie also registered some confusions. La bohème was more than a dissipated group of youthful students, posturing and impoverished. It really comprised an assortment of dissident bourgeois, often individualistic in the extreme—seeking identities as writers, journalists, painters, artists of all kinds—who often made a virtue of their failure and mocked the rigidities of bourgeois life and culture. Courbet’s café companions often bore more resemblance to Poulot’s “sublime” workers than they did to any other layer of the bourgeoisie. And a large number of students (mostly of provincial origin and usually living on a meager allowance) added to the confusions of class. Skeptical, ambitious, contemptuous of tradition and even of bourgeois culture, they helped make Paris “a vast laboratory of ideas” and the foyer of utopian schemes and ideologies.8 Relatively impoverished, they were forced into some kind of contact with the street people and some workers, and knew only too well the rapacity of the shopkeeper and the loan shark. They formed the core of many a revolutionary conspiracy (the Blanquists, for example), were active in the International, and were likely to launch their own spontaneous movements of protest into the streets of the Left Bank. And they often merged with the disgruntled layers of la bohème. A strong dissident movement within the bourgeoisie, which sometimes encompassed relatively well-off lawyers and professionals as well as successful writers and artists, had its roots in these layers of the population.

This class structure underwent a certain transformation during the Second Empire. While data are lacking to make exact comparisons, most observers agree that if there was any change at all in the lopsided distribution of wealth, it was toward greater rather than less inequality. Important shifts occurred within the class fragments, however. Business activities (banking, commerce, limited companies) became relatively more important within the haute bourgeoisie, drawing to their side not only those state functionaries (like Haussmann) bitten with the Saint-Simonian vision but also a segment of the propertied class that found diversification into the stock market and Parisian property more remunerative than relatively stagnant rural rents. But if traditional landed property became rather less prominent, divisions between finance, commerce, and industry became more so, while rivalries among fractions (such as that between the Rothschilds and the Pereires) assumed greater importance. The haute bourgeoisie was no less divided in 1870 than it was in 1848, but the divisions were along different lines.

There were similar important mutations within the working class. Transformations in the labor process and in industrial structure had their effects. The consolidation of large-scale industry in sectors such as printing, engineering, and even commerce (the large department stores) set the stage for more direct confrontation between labor and capital in the workplace, signaled by the printers’ strike of 1862 and the commerce workers’ strike of 1869. The reorganization and deskilling of craft work also exacerbated the sense of external domination either by the small masters or by the innumerable intermediaries who controlled the highly fragmented production system. Strikes by tailors and bronze workers in 1867, by tanners and woodworkers in 1869, and by the iron founders at Cail in 1870 registered the growing confrontation between capital and labor, even in trades where outwork and small-scale production were the rule. The prospects for craft workers to become small masters seem to have diminished as the latter were either pro-letarianized or forced to separate themselves out as a distinct layer of bosses, with all that this entailed.

But if Paris had a rather more conventional sort of proletariat in 1870 than it did in 1848, the working classes were still highly differentiated. “The crucible in which workers were forged was subtle,” says Duveau; “the city created a unity out of working class life, but its traditions were as multiple as they were nuanced.”9 And nothing was done to assuage the condition of that dead weight of an industrial reserve army and of the under-employed. Living close to the margin of existence, their numbers augmented by migration, they merged into a massive informal sector whose prospects looked increasingly dismal as Haussmann shifted the state apparatus toward a more neo-Malthusian stance with respect to welfare provision. But with nearly a million people living at or below the poverty level (according to Haussmann’s own estimates), there were limits to how far even he could afford to go. A surge of unemployment in 1867 thus provoked the Emperor into opening an extensive network of soup kitchens to feed the hungry.

The internal composition of the middle classes also shifted. While the liberal professions, managers, and civil servants participated in the fruits of economic progress, the rentiers and pensioners had a harder time of it as rising living costs and rents in Paris eroded some of their wealth (unless, of course, they switched to more speculative investments, in which case, if Zola’s L’Argent (Money) is anywhere near accurate, they were as likely to lose their fortunes to the stock exchange wolves as to augment their stagnant rural rents). The shopkeepers, if their diminishing hold on Parisian property is anything to go by, continued their descent into the lower middle class or even lower, except for those who found new ways of selling (like the grand department stores and the specialized boutiques, which catered to the upper classes and the flood of tourists). This is the sort of transition that Zola records in such excruciating detail in The Ladies’ Paradise. At the same time, the boom in banking and finance created a host of intermediate white-collar occupations, some of which were relatively well paid.

The class structure of Paris was in full mutation during the Second Empire. By 1870 the lineaments of old patterns of class relations—traditional landowners, craft workers and artisans, shopkeepers, and government employees—could still be easily discerned. But another kind of class structure was now being more firmly impressed upon it, itself confused between the state-monopoly capitalism practiced by much of the new haute bourgeoisie and the growing subsumption of all labor (craft and skilled) under capitalist relations of production and exchange in the vast fields of small-scale Parisian industry and commerce. Deskilling was at work undermining craft worker power. And economic power was shifting within these frames. The financiers consolidated their power over industry and commerce, at least in Paris, while a small group of workers began to acquire the status of privileged aristocracy of labor within a mass of growing unskilled labor and impoverishment. Such shifts produced abundant tensions, all of which crystallized in the fierce class struggles fought out in Paris between 1868 and 1871.

Then, as now, the ideals and realities of community were hard to sort out. As far as Paris was concerned, Haussmann would have nothing to do with the ideal, and if the reality existed, he was blind to it. The Parisian population was simply a “floating and agitated ocean” of immigrants, nomads, and fortune—and pleasure-seekers of all types (not only workers but also students, lawyers, merchants, etc.), who could not possibly acquire any stable or loyal sense of community.10 Paris was simply the national capital, “centralization itself,” and had to be treated as such. Haussmann was not alone in this view. Many in the haute bourgeoisie, from Thiers to Rothschild, thought of Paris only as “the geographical key to a national power struggle” whose internal agitations and propensity for revolution disqualified it for consideration as a genuine community of any standing.11 Yet many who fought and died in the siege of Paris and in the Paris Commune did so out of some fierce sense of loyalty to the city. Like Courbet, they defended their participation in the Commune with the simple argument that Paris was their homeland and that their community deserved at least that modicum of freedom accorded to others. And it would be hard to read the Paris Guide of 1867, the collective work of some 125 of the city’s most prestigious authors, without succumbing to the powerful imagery of a city to which many confessed a passionate and abiding loyalty. But the Guide also tells us how many Parisians conceived of community on a smaller scale of neighborhoods, quarters, and even the new arrondissements created only seven years before. That kind of loyalty was also important. During the Commune, many preferred to defend their quarters rather than the city walls, thus giving the forces of reaction surprisingly easy access to the city.

“Community” means different things to different people. It is hard not to impose meanings and thus do violence to the ways in which people feel and act. Haussmann’s judgments, for example, were based on a comparison with a rural image of community. He knew all too well that the “community of money” prevailed in Paris, rather than the tight network of interpersonal relations that characterized much of rural life. And he had a visceral aversion to any version of community that invoked the socialist ideal of a nurturing body politic. Yet while Haussmann denied the possibility of community of one sort, he strove to implant another, founded in the glory of Empire and oozing with symbols of authority, benevolence, power, and progress, to which he hoped the “nomads” of Paris would rally. He used, as we have seen, the public works (their monumentalism in particular); the Universal Expositions; the grand galas, fêtes, and fireworks; the pomp and circumstance of royal visits and court life; and all the trappings of what became known as the fête impériale to construct a sense of community compatible with authoritarian rule, free-market capitalism, and the new international order.

Figure 81 The cartoonist Darjou here responds to Haussmann’s comment that Paris is not a community but a city of nomads by pointing out that displacement by Haussmann’s works has been a primary cause of nomadism.

Haussmann tried, in short, to sell a new and more modern conception of community in which the power of money was celebrated as spectacle and display on the grand boulevards, in the grands magasins, in the cafés and at the races, and above all in those spectacular “celebrations of the commodity fetish,” the Universal Expositions. No matter that some found it hollow and superficial, a construction to be revolted against during the Commune, as Gaillard insists.12 It was a remarkable attempt, and much of the population evidently bought it, not only for the Second Empire but also well beyond. In his decentralization of functions within the arrondissements and in the symbolism with which he invested them (the new mairies, for example), Haussmann also tried to forge local loyalties, albeit within a hierarchical system of control. Again, he was surprisingly successful. Loyalties to the new arrondissements built quickly and have lasted as a powerful force to this day. They were vital during the Commune, perhaps because the arrondissements were the units of National Guard enrollment, and the latter, perhaps not by accident, turned out to be the great agent of direct, local democracy. Haussmann’s impositions from above became the means of expression of grassroots democracy from below.

That sentiment of direct, local democracy had deep historical roots. It was expressed in the Parisian sections of 1789 and in the political clubs of 1848, as well as in the manner of organizing public meetings after 1868. There was strong continuity in this political culture, which saw local community and democracy as integral to each other. That ideology carried over to the economic sphere, where Proudhon’s ideas on mutualism, cooperation, federation, and free association had a great deal of credibility. But Proudhon emerged as such an influential thinker precisely because he articulated that sense of community through economic organization which appealed so strongly to the craft worker tradition and even to small owners. And Paris had long been divided into distinctive quarters, urban villages, each with its own distinctive qualities of population, forms of economic activity, and even styles of life. The neighborhood wineshop, as has frequently been emphasized, was a key institution for forging neighborhood solidarities. In addition, the flood of immigrants often had their distinctive “receiving areas” within the city based upon their place of origin or their trade, and the “nomads” of Paris seem often to have used their kinship networks as guides to the city’s labyrinths.

There is a thesis, held in rather different versions by writers as diverse as Lefebvre and Gaillard, that Haussmann’s transformations, land speculation, and imperial rule disrupted the traditional sense of community and failed to put anything solid in its place. Others argue that the administration’s refusal of any measure of self-governance that would give political expression to the sense of community was the major thorn in Parisians’ side. The Commune can then be interpreted as an attempt by an alliance of classes to recapture the sense of community that had been lost, to reappropriate the central city space from which they had been expelled, and to reassert their rights as citizens of Paris.13

The thesis is not implausible, but it needs considerable nuancing to make it stick. It is, for example, fanciful to argue that the notion of community had been more stable and solidly implanted in 1848. There was sufficient disarray in evidence then for the thesis of Haussmann’s disruptions to be easily dismissed as a romanticized retrospective reconstruction. What is clearer is that the realities and ideologies of the construction of community underwent a dramatic transformation in Second Empire Paris. And the same processes that were transforming class relations were having equally powerful impacts upon community. The community of money was dissolving all other bonds of social solidarity, particularly among the bourgeoisie (a process that Balzac had complained about as early as the 1830s).

Haussmann’s urbanization was conceived on a new and grander spatial scale. He simultaneously linked communities that had formerly been isolated from each other. At the same time, this linking allowed such communities specialized roles within the urban matrix. Spatial specialization in social reproduction became more significant, as did spatial specialization in production and service provision. True, Haussmann’s programs also wiped out some communities (Ile de la Cité, for example), punched gaping holes through others, and sponsored much gentrification, dislocation, and removal.

This provoked a great deal of nostalgia for a lost past on the part of all social classes, whether directly affected or not. Nadar, a photographer, confessed it made him feel a stranger in what should have been his own country. “They have destroyed everything, even memory,” he lamented.14 But however great the sense of loss or the “grieving for a lost home” on the part of the many displaced, collective memories in practice were surprisingly short and human adjustment rather rapid. Chevalier notes how memories and images of the old Ile de la Cité were eradicated almost instantaneously after its destruction.15 The loss of community, which many bourgeois observers lamented, probably was generated primarily by the breakdown of traditional systems of social control consequent upon rapid population growth, increased residential segregation, and the failure of social provision (everything from churches to schools) to keep up with the rapid reorganization of the space of social reproduction. Haussmann’s neo-Malthusianism with regard to social welfare, plus the insistence upon authoritarian rule rather than municipal self-government, undoubtedly exacerbated the dangers. The problem was not that Belleville was not a community but that it became the sort of community that the bourgeoisie feared, and the police could not penetrate, the government could not regulate, and where the popular classes, with all their unruly passions and political resentments, held the upper hand. This is what truly lay behind the prefect of police’s complaint of 1855:16

The circumstances which compel workers to move out of the center of Paris have generally, it is pointed out, had a deplorable effect on their behavior and morality. In the old days they used to live on the upper floors of buildings whose lower floors were occupied by the families of businessmen and other fairly well-to-do persons. A species of solidarity grew up among the tenants of a single building. Neighbors helped each other in small ways. When sick or unemployed, the workers might find a great deal of help, while on the other hand, a sort of human respect imbued working class habits with a certain regularity. Having moved north of the Saint Martin canal or even beyond the barrières, the workers now live where there are no bourgeois families and are thus deprived of their assistance at the same time as they are emancipated from the curb on them previously exercised by neighbors of this kind.

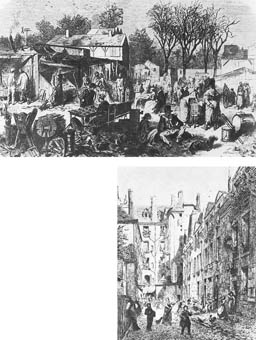

Figure 82 The clearances on the Ile de la Cité, here recorded in a late 1860s photo, were extensive even by present-day standards.

The growth and transformation of industry, commerce, and finance; immigration and suburbanization; the breakdown of controls in the labor market and the apprenticeship system; the transformation of land and property markets; growing spatial segregation and specialization of quarters (of commerce, craft work, working-class reproduction, etc.); reorganization of housing, social welfare provision, and education—all of these taken together, under the overwhelming power of the money calculus, promoted vital shifts in the meaning and experience of community. Whatever the sense of community had been in 1848, it was radically changed, but no less coherent or viable (as the Commune was to prove), in 1870. Let us probe these differences a little more deeply.

The workers’ movement of June 1848 was crushed by a National Guard drawn from over three hundred provincial centers. The bourgeoisie who moved within the commercial orbit of Paris had the advantage of “much better communications over long distances than the working class, which possessed strong local solidarity but little capacity for regional or national action.”17 The bourgeoisie used its far-flung spatial network of commercial contacts to preserve its economic and political power.

Behind this incident lie a problem and a principle of some importance. Does “community” entail a territorial coherence—and if so, how are boundaries fixed? Or can “community” mean simply a community of interest without regard to particular spatial boundaries? What we see, in effect, is the bourgeoisie defining a community of class interest sprawled over space. This was, for example, the secret of Rothschild’s success (with his far-flung family network of correspondents in the different national capitals). But armed with the lessons of 1848, and following their class interests, the haute bourgeoisie in business and administration (such as Pereire, Thiers, and Haussmann) increasingly thought and acted along such lines. Thiers mobilized to repress the Commune in exactly the same way as had been done in 1848. The bourgeoisie had discovered that it could use its superior command over space to crush class movements, no matter how intense local solidarity was in particular places.

The workers were also pressed to redefine community in terms of class and space. Their movement of 1848 had been marked by xenophobia against foreign workers coupled with intense sympathy for oppressed peoples everywhere (solidarity with Poland sparked major street unrest in Paris in May 1848). The new space relations and changing international division of labor prompted writers like Corbon to argue that the labor question now had no local solution but had to be looked at from a European perspective, at least.18 The problem was, then, to make this internationalist perspective compatible with the mutualist and corporatist sentiments that infused the working-class tradition. The tradition of compagnonnage and the tour de France provided some kind of basis for thinking about new kinds of worker organization that could command space in a fashion comparable to the bourgeoisie. This was the problem the newborn International Working Men’s Association faced. The effect was to create an enormous and uncontrollable panic within the ranks of the bourgeoisie, precisely because the International set out to define a community of class “across all provinces, industrial centers and states” and thus match the power the bourgeoisie had found so effective in 1848.19

In practice, the bourgeoisie trembled without good reason. The relative weakness of the International’s connections, coupled with the powerful residue of a highly localized mutualism, became all too apparent in the War of 1870 and the Commune. In contrast, the creation of the citywide Fédération des Chambres Syndicales Ouvrières in 1869—an umbrella organization (under Varlin’s leadership) for the newly legalized trade unions—helped build a worker perspective on labor questions on a citywide scale consistent with Haussmann’s urbanization. This kind of organization synthesized powerful traditions of localized mutualism and direct democracy into citywide strategies of class struggle over the labor process and conditions of employment. This was to be part of the volatile mix that gave the Commune so much of its force.

The space over which community was defined altered as the scale of urbanization changed and spatial barriers were reduced. But it also shifted in response to new class configurations and struggles in which the participants learned that control over space and spatial networks was a source of social power. At this point the evolutions of class and community intersected to create new and intriguing possibilities and configurations.

The new communities of class were paralleled by new forms of the class of community. The social space of Paris had always been segregated. The glitter and affluence of the center had long contrasted with the dreary impoverishment of the suburb; the predominantly bourgeois west, with the working-class east; the progressive Right Bank, with the traditionalist though student-ridden Left Bank.20 Within this overall pattern there had been considerable spatial mixing. Dismal slums intermingled with opulent town houses; the businesses of craft workers and artisans mingled with aristocratic residences on the Left Bank and in the Marais; and, though diminished, the celebrated vertical segregation (rich bourgeois on the second floor above the boutique and worker families in the garret) still brought some social contact between the classes. Masters and employees in industry and commerce also had traditionally lived close to each other, particularly within the city center, and this pattern continued to hold in spite of Haussmann’s efforts at deindustrialization.

While it would be untrue to say that Haussmann created spatial segregation in the city, his works, coupled with the land-use sorting effect of rent in the context of changed land and property markets, produced a greater degree of spatial segregation, much of it based on class distinctions. Slum removal and building speculation consolidated bourgeois quarters to the west, while the separate system of land development on the northern and eastern peripheries produced tracts of low-income housing unrelieved by any intermingling with the upper classes. In Belleville, La Villette, and Montmartre this produced a vast zone of generic rather than occupationally specific working-class concentrations that were to play a crucial role in the agitation that led up to the Commune. Land-use competition also consolidated the business and financial quarters, and industrial and commercial activities also tended toward a tighter spatial clustering in selected areas of the center—printing on the Left Bank, metalworking on the inner northeast, leather and skins around Arts et Métiers, ready-to-wear clothing just off the grand boulevards. And each type of employment quarter often gave social shape to the surrounding residential quarters—the concentrations of white-collar employees to the north of the business center, the craft workers to the northeast center, the printers and bookbinders (a very militant group) on the Left Bank. Zones and wedges, centers and peripheries, and even the fine mesh of quarters were much more clearly class or occupationally defined in 1870 than they had been in 1848.

Figure 83 To meet their needs, working-class people had to search out either peripheral housing (often of a temporary nature) or the more substantial inner courtyards within the center, where overcrowding was chronic.

Though this had much to do with the spatial scale of the process that Haussmann unleashed, it was also a reflection of fundamental transformations of the labor process, the industrial structure, and an emergent pattern of class relations in which craft and occupation were playing in aggregate a less significant role. The consolidation of commercial and financial power, the rising affluence of certain segments of the haute and middle bourgeoisie, the growing separation of workers and masters, and increasing specialization in the division of labor that permitted deskilling were all registered in the production of new communities of class. Old patterns could still be discerned—the intermingling on the Left Bank was as confused as ever—but it was now overlaid with a fiercer and more definite structuring of the spaces of social reproduction. Spatial organization and the sense of community that went with it were caught up in the processes of reproduction of class configurations. As Sennett perceptively concludes, “localism and lower class fused” during the Second Empire, not because workers necessarily wanted it that way but because social forces imposed such identifications upon them.21

Exactly how the community of class worked is best illuminated by Poulot’s jaundiced account of “sublimism” among Parisian workers. As a significant industrialist and employer, he was infuriated by insubordination in the workplace and attitudes of anti-authoritarianism and class opposition. He considered failures of family formation to be a major part of the problem (hence his attempt to co-opt the women and promote “respectable” forms of family life). The neighborhood wine bars were a problem. Workers and even whole families habitually gathered there to voice complaints that could not be heard under the oppressive conditions of the workshop or in the isolation of subcontracted work at home. The fact that patronage of the wine bar was mostly neighborhood rather than trade-based,22 allowed a perspective to build on the condition of the working class in general rather than on conditions of labor within a particular trade. There were also tensions in and around what the wine bar was about for, as Sennett notes: “When the café became a place of speech among peers at work, it threatened the social order; when the café became a place where alcoholism destroyed speech, it maintained the social order.” It was for this reason that socialists like Varlin cultivated cooperative eating establishments (La Marmite) as political spaces for the articulation of socialist ideals. What Poulot recognized, and what has often proven to be the case, is that class solidarities and identifications are far stronger when backed, if not sparked, by community organization (the case of mining communities is paradigmatic in this regard). Class identifications are forged as much in the community as they are in the workplace. Poulot’s frustration was that he could assert some level of control over the workplace but not in the space of community.

Gould disagrees with this perspective. “The rebuilding of central Paris, the geographical dispersion of workers in a number of industrializing trades, and the significant expansion of the population in the new peripheral arrondissements,” he writes, “created the conditions for a mode of social protest in which the collective identity of community was largely divorced from the work-based identities of craft and its more elusive cousin, class.” The neighborhood was a “basis for a collective identity that had little to do with the world of labor.” The Commune was, therefore, “predicated on identification with the urban community rather than with craft and class.”23 Gould claims to have arrived at this conclusion solely on the basis of “neutral” empirical evidence, and rails at those of us who supposedly superimpose a class interpretation upon recalcitrant facts.

Gould is quite correct to insist that the new peripheral spaces (such as Belleville), which played such an important role in the Commune, were less defined by craft, but is quite in error to assume a lack of relation to “its more elusive cousin, class.” The evidence he adduces is that Belleville did not significantly increase its class concentration between 1848 and 1872 (it merely remained stable, by his own account, at the astounding level of 80 percent classified as workers in a vastly increased population in 1872). Poulot, for one, would doubtless appreciate Gould’s insistence on the importance of neighborhood networks and institutions in the creation of social solidarities, but would have been astonished to learn that these had nothing to do with class. The main evidence that Gould presents for cross-class solidarities is the class composition of witnesses at working-class weddings—the witnesses for workers are disproportionately in the categories of owners and employers. From this he concludes that social networks in the neighborhood had no class basis. Gould conveniently ignores the fact that concubinage was the rule and marriage the exception (in 1881, Poulot went to great lengths to found a society for the promotion of working-class marriages precisely for this reason). Most workers did not get married because it was too expensive and too complicated. Those who did, were almost certainly seeking some upward mobility and respectability, and were therefore far more likely to want “respectable” witnesses (such as doctors, lawyers, local notables).

The distinction between workers and small owners was, as we have repeatedly noted, porous, and this was not the primary class divide—bankers and financiers, landlords, merchant capitalists, the industrialists, and the whole oppressive network of subcontractors constituted the main class enemy for the workers, and I doubt very much if any of them ever turned up as witnesses in Gould’s data. That the witnesses were part of the local social network is undeniable, but the meaning to be ascribed to that is also open to question. The wineshop and café owners, according to Haine, frequently acted as witnesses for their clients, but this is hardly evidence of lack of class solidarity because those establishments were often centers for the articulation of class-consciousness.24 Gould is, however, quite correct to point to the issue of municipal liberties as a crucial demand both before and during the Commune. But the evidence is strong on both sides—bourgeoisie as well as workers—that this was conceptualized as a class demand, albeit one that overlapped (sometime uneasily) with the more radical forms of bourgeois political republicanism.

Figure 84 Working-class street life around Les Halles (by Le Couteux) and night-life in the wineshops (by Crepon) was a far cry from bourgeois respectability. Note how women and children seem fully integrated into the wineshop scene.

Contrary to Gould’s unsubstantiated opinion that “there is no evidence” that the socialist content of the public meetings which occurred after 1868 was having any effect, we have Varlin’s confident assertion as early as 1869 that eight months of public discussion had revealed that “the communist system is more and more favored by people who are working themselves to death in workshops, and whose only wage is the struggle against hunger,” and Millière’s thoughtful press articles in 1870 on the prospects and dangers of “the social commune” as a solution to the problems of working class life.25 Control of the body politic had, as we have seen, been seriously contested along class lines ever since the 1830s, if not before, and the association between “communism” and “commune” was actively being revived. That the demand for municipal self-governance was so salient in a city where the working class constituted a clear majority can hardly be taken as evidence of a lack of class interest. And if the Commune was solely about municipal liberty, why did the republican bourgeoisie (who generally favored it) flee the city so fast and why did the monarchists (who had long campaigned for political decentralization) provide the core of military leadership that dealt so savagely with the communards as “reds” in the bloody week of May 1871?

Interestingly, much of the evidence that Gould mobilizes about the salience of spatial propinquity in social (class) relations, and the importance of neighborhood institutions and of the new arrondissements as loci of social solidarity, is perfectly consistent with the account I am offering here. The Commune was indeed a different kind of event from 1848, and in part it was so because of the radical reorganization of the living spaces that haussmannization accomplished along with the equally radical transformations in labor processes, in the organization of capital accumulation, and in the deployment of state powers. The community of class and the class of community became more and more salient features of Second Empire daily life and politics, and without the close intermingling of these elements the Commune would not have taken the form it did.