Upon the different forms of property, upon the social conditions of existence, rises an entire superstructure of distinct and peculiarly formed sentiments, illusions, modes of thought and views of life.

—MARX

To try to peer inside consciousness is ever a perilous exercise. Yet something has to be said about the hopes and dreams, the fears and imaginings that inspired people to action. But how to reconstruct the thoughts and feelings of Parisians of more than a century ago? To be sure, there is a vast literary record (popular and erudite), which, when complemented by cartoons, paintings, sculpture, architecture, engineering, and the like, tells us how at least some people felt, thought, and acted. Yet many left no such tangible mark. The mass of the population remains mute. It takes a careful study of language—words, gestures, popular songs, theater, and mass publications (with titles like La Science pour Tous; Le Roger Bontemps; La Semaine des Enfants)—to get even a fragmentary sense of popular thought and culture.1

The Second Empire had the reputation of being an age of positivism. Yet, by modern standards, it was a curious kind of positivism, beset by doubt, ambiguity, and tension. Thinkers were “attempting in differing ways and to differing extents to reconcile aspirations and convictions that [were] incompatible.”2 What was true for the intelligentsia, the artists, and the academicians was also profoundly true for many workers; though passionately interested in progress, they frequently resisted its applications in the labor process. Wrote Corbon: “the worker who reads, writes, has the spirit of a poet, who has great material and spiritual aspirations, the devotee of progress, becomes, in fact, a reactionary, retrograde and obscurantist, when it comes to his own trade.”3 For the craft workers, of course, their art was their science, and their deskilling was no sign of progress, as leaders like Varlin were ceaselessly to complain. Since Paris was the hearth of intellectual ferment, not only for the cream of the country’s intelligentsia but also for the “organic intellectuals” of the working class, it experienced these tensions and ambiguities with double force. There were also innumerable intersections in which the sense of increasing submission of the worker to the money power of capitalism was mirrored by the prostitution of the skills of writer and artist to the dictates of the market. Here was the unity of experience that put la bohème on the side of workers in revolution.

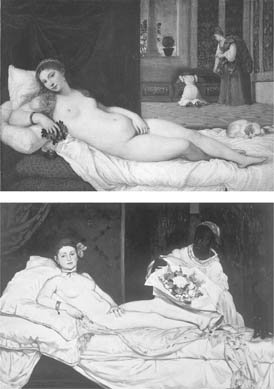

Figure 90 The way in which modernity echoed tradition is beautifully set up with Manet’s Olympia, which clearly used Titian’s Venus d’Urbino for its model. But the obedient dog is replaced by an uncontrollable cat (a symbol of the powerful Masonic movement among the middle classes), the retainer is much more of this world and her power is more ambiguous, and the nude appears less of a courtesan and, as many critics at the time complained, more like a common prostitute.

Most were struck by the virtues of science. The achievements of medicine had particular importance. Not only were the medical students often in the avant-garde in the political and scientific movements of the 1860s, but the image of the cool dissection of something as personal as the human body became a paradigm of what science was all about. And if the human body could be dissected, then why not do the same thing to the body politic? Science was not so much a method as an attitude given over to the struggle to demystify things, to penetrate and dissect their inner essence. Such an attitude even underlay the movement toward “art for art’s sake.” Not only scientists but writers, poets, economists, artists, historians, and philosophers could aspire to science. “It was free of conventional morality and of any didactive motive; it was ‘pure’ in the sense they wished their art to be ‘pure,’ [and] its objectivity and impartiality resembled their determination to avoid sentimentality and an open display of personal feeling.” It was every writer’s ambition, as Sainte-Beuve wrote in praise of Madame Bovary, to wield “the pen as others wield the scalpel.” Flaubert, the son of a doctor, was fascinated by the dissection of cadavers all his life. “It’s a strange thing, the way I’m attracted by medical studies,” he wrote, but “that’s the way the intellectual wind is blowing nowadays.” Maxime du Camp, one of Flaubert’s closest friends in his early years, subsequently wrote an “anatomical dissection” of the “body” of Paris in a six-volume study (and, as Edmond Goncourt remarked in his journal, pretty much dissected Flaubert in his Mémoires in similar fashion). Delacroix was moved to observe that science, “as demonstrated by a man like Chopin is art itself, pure reason embellished by genius.” Many artists saw themselves as working in a spirit analogous to that of a scientist like Pasteur, who was then penetrating the mysteries of fermentation.4

Others, sensing the widening gap, sought to close it. “The time is not far off,” wrote Baudelaire, “when it will be understood that any literature which refuses to march fraternally between science and philosophy is a homicidal, suicidal literature.” Hugo thought likewise: “It is through science that we shall realize that sublime vision of poets; social beauty.… At the stage which civilization has reached, the exact is a necessary element in what is splendid, and artistic feeling is not only served but completed by the scientific approach; the dream must know how to calculate.”5 Craft workers like Varlin would surely have agreed; that was, after all, why they set out to educate themselves. The historian Michelet was even more programmatic. He sought “the poetry of truth, purity itself, [that] which penetrates the real to find its essence … and so breaks the foolish barrier which separates the literature of liberty from that of science.”6

Confusions and ambiguities arose because few were ready to separate science from sentiment. While a scientific posture helped liberate thinkers from the traps of romanticism, utopianism, and, above all, the mysticism of received religion, it did not absolve them from considering the directions of social progress and the relation to tradition. “A little science takes you away from religion; a lot brings you back to it,” said Flaubert. Saint-Simon had earlier led the way by insisting that his new science of society could go nowhere without the power of a renovated Christianity to drive its moral purpose. Auguste Comte (who collaborated with Saint-Simon in his early days) followed suit. The systematizer of an abstract, systematic, and theoretical positivism in the 1830s converted to a more humanistic strain of thought in the 1840s. From 1849 until his death in 1857, tract after tract dedicated to the foundation of positivist churches of humanity issued forth from his house close by the Place Sorbonne.

Those most concerned with constructing a science of society did not want to separate fact from value. Prior to 1848, social science had been divided between the grand systematizers like Comte, Saint-Simon, and Fourier, whose abstractions and speculations might inspire, and the empiricists, who, like the hygienists of the 1840s, confined themselves to moving but Malthusian descriptions of the awful pathologies and depravities to which the poor were exposed and the dangerous classes prone. Neither tactic yielded incisive social science. It took Proudhon to make the connection between capitalism, pauperism, and crime more explicit in the French context, and Marx’s Capital, the first volume of which came out in German only in 1867, made the connections even clearer. The medical students who later formed the core of the Blanquist movement likewise used their materialist scalpels to great effect in the dissection of society and its ills. But other, less encouraging trends could be observed. Le Play combined positivism with empiricism to construct a new kind of social science during the 1850s in order to support the Catholic cause. His extensive studies of family budgets and family life were dedicated to securing the Christian concept of the family as the basis of the social order. The liberal political economists were no less assiduous in shaping their “objective” social science to political ends.7

These confused crosscurrents are hard to understand without reference to the complex evolution of class relations and alliances that produced 1848, the conservative Republic, and the Empire. In the Revolution of 1848, as we have seen, progressive social democrats were joined on the barricades by a motley assortment of la bohème (Courbet and Baudelaire, for example), romantics (Lamartine, George Sand), utopian socialists (Cabet, Blanc), and Jacobins (Blanqui, Delescluze), as well as by an equally motley assortment of workers, students, street people, and representatives of “the dangerous classes.” The bitter days of June shattered that alliance in all manner of ways. Whatever their actual role may have been, the powerful ideological stamp that the romantics and the socialist utopians put upon the rhetoric of 1848 was totally discredited with the June repression. “Poets cannot cope,” quipped Flaubert. Proudhon found the demagoguery on the barricades vapid and utopian, totally lacking in practicality. Yet romanticism and utopianism had been the first line of defense against the subordination of all modes of thought to religion. Some other means of defense and protest had to be found:

Utopianism was now, generally speaking, displaced by positivism; the mystic belief in the virtue of the people and hopes for a spiritual regeneration gave way to a more guarded pessimism about mankind. Men began to look on the world in a different way, for splendid illusions had been shattered before their eyes, and their very style of talking and writing changed.8

Herein lies the significance of Courbet’s sudden breakthrough into realism (called “socialist” by many) in art, Baudelaire’s fierce and uncompromising embrace of a modernity given a much more tragic dimension by the violence of 1848, and Proudhon’s initial confusion followed by total rejection of utopian schemes. Courbet, Baudelaire, and Proudhon could, and did, make common cause.9 Their disillusionment with romanticism and utopianism was typical of a social response to 1848 that looked to realism and practical science as means to liberate human sentiments. They may have remained romantics at heart, but they were romantics armed with scalpels, ready to take shelter from the authoritarianism of religion and Empire behind the shield of positivism and detached science. The respectable bourgeoisie drew a similar sort of conclusion, though for quite different reasons. Professional schools should be organized, wrote one, to train competent workers, foremen, managers of factories “for the combats of production” instead of producing “unemployed bacheliers embittered by their impotence, born petitioners of every public office, disturbing the state by their pretensions.”10

It would seem that the Empire, with its concerns for industrial and social progress, would have welcomed this turn to realism and science, would have encouraged and co-opted it. And on the surface it did just that, through promotion of Universal Expositions dedicated to lauding new technologies, the establishment of worker commissions to examine the fruits and applications of technological change, and the like. Yet the Second Empire did nothing to reverse and, until 1864, even exacerbated what most commentators agree was a serious decline of French science from its pinnacle early in the century into relative mediocrity by the end.11 Little was done to support research—Pasteur, for example, had a hard time obtaining funds—while government policies (denying students free speech on political questions, for example) often threw the universities into such turmoil that student protests were forced onto the streets or into underground conspiracies like the Blanquist. Science and positivism, free thought and materialism, became forms of protest. The mysticism of religion, the censorious authoritarianism and the frivolity of Second Empire culture were its main targets.

The contradictions in imperial policy also have to be understood in terms of the shaky class alliance upon which Louis Napoleon had to rest his power. It was, indeed, his genius and misfortune that he sought the implantation of modernity in the name of tradition, that he used the authoritarianism of Empire to champion the freedoms and liberties of private capital accumulation. He could occupy such an odd niche in history precisely because the instability of class relations in 1848 gave him the chance to rally the disillusioned and fearful of all classes around a legend that promised stability, security, and perhaps national glory. Yet he knew he had to move forward. “March at the head of the ideas of your century,” he wrote, “and those ideas follow and support you. March behind them and they drag you after them. March against them, and they overthrow you.”12 The problem, however, was that Napoleon had to seek support from a Catholic Church that was reactionary and uncultured at the base and led by a Pope who totally rejected reconciliation with progress, liberalism, and modern civilization. To be sure, there were progressive Catholics, unloved by Rome, who, like Montalembert, supported the coup d’état but later so deplored the alliance of Catholics with Empire that they were hauled before the public prosecutor. But the net effect, at least until the breakdown of the alliance in the 1860s, was to surrender much of education to those who thought of it solely as a means for social control by the inculcation of traditional values rather than as a fount of social progress. That, combined with censorship, transformed the free-thought movement in the universities into a major criticism of Empire.

The Empire also was vulnerable because it uncomfortably straddled the break between modernity and tradition. It sought social and technological progress, and therefore had to confront in thought as well as in action the power of traditional classes and conceptions (religion, monarchical authority, and artisanal pride). The Empire was also founded on legend; but the legend could not bear too close an inspection. There were two principal embarrassments: the manner of the First Empire’s emergence from the First Republic, and its ultimate collapse. The censors sought to impose a tactful silence on such matters, banning popular performances and plays (even one by Alexander Dumas) that referred to them. Victor Hugo, thundering against the iniquities of Napoleon “le petit” from the safety of exile, took up the cudgels. He inserted a brilliant but, from the stand-point of plot, quite gratuitous description of the defeat at Waterloo into Les Misérables, editorializing as he did so that for Napoleon I to have won at Waterloo “would have been counter to the tide of the nineteenth century,” that it would have been “fatal to civilization” to have “so large a world contained within the mind of a single man,” and that “a great man had to disappear in order that a great century might be born.” Les Misérables, though published in Brussels, was “in everyone’s hands” in the Paris of 1862, and Hugo’s message was surely not lost on his readers.13

This kind of exploitation of tradition was not new. The grapplings of historians and writers like Michelet, Thiers, and Lamartine with the meaning of the French Revolution had played a major role in the politics of the 1840s. Republicans used history and tradition after 1851 to make political points. They were as much concerned to invent tradition as to represent a certain version of it. This is not to accuse them of distortion, but of reading the historical record in such a way as to mobilize tradition to a particular political purpose. It was almost as if the dead weight of tradition were such that social progress had to depend on its evocation, even when it did not weigh “like a nightmare on the brain of the living,” as Marx puts it in the Eighteenth Brumaire.14 In this respect, artists, poets, novelists, and historians made common cause. Many of Manet’s paintings of the Second Empire period, for example, portray modern life through the overt re-creation of classical themes (he took the controversial Olympia of 1863 directly from Titian’s Venus d’Urbino). He did so, Fried suggests, in a way that echoed Michelet’s political and republican tracts of 1846–1948 while answering Baudelaire’s plea for an art that represented the heroism of modern life.15

The experience of craft workers was no different. Their resistance had forced much of Parisian industry to all manner of adaptations. They had defended their work and their lifestyle fiercely, and had used corporatist tactics to do so. When the Emperor invited them to inspect the virtues of technological progress and document their reactions to the Universal Exposition of 1867, they responded with a defense of craft traditions.16 Yet their power was being eroded and sometimes swamped by competition and technological change within the new international division of labor. This posed enormous problems for the “organic intellectuals” of the working-class movement as well as for revolutionary socialists who sought a path to the future but had to do so on the basis of fiercely held ideological traditions (stemming, in the Blanquist case, from the French Revolution). And the mass in-migration of often unskilled workers, clinging to bastardized rural traditions and parochial perspectives, did not help matters. But the coup d’état had also revealed significant pockets of rural revolutionary consciousness and resistance, from which were reimported revolutionary sentiments that Paris had hitherto prided itself upon exporting to a supposedly backward countryside. That the countryside was itself a site of class relations and contestations, and hence a breeding ground for class politics, was a fact that most Parisians, as we have seen (chapter 1), preferred to deny.

The problem, however, was that the new material circumstances and class relations in Parisian industry and commerce required a line of political analysis and action for which there was no tradition. The International, which began rooted in mutualist and corporatist traditions, had to invent a new tradition to deal with the class struggles of 1868–1871. This put a forward-looking and modernist gloss on some of what happened in the Commune. It was, sadly, more successful after the martyrdom of many of its members in 1871 than before. Consciousness is as much rooted in the past and its interpretations as in the present.

The modernity that Haussmann created was itself powerfully rooted in tradition. The “creative destruction” necessitated by the demolitions and reconstructions had its precedents in the revolutionary spirit. Though Haussmann would never evoke it, the creative destruction of the barricades of 1848 helped pave his way. And his willingness to act decisively was admired by many. Wrote About in the Paris Guide of 1867, “Like the great destroyers of the eighteenth century who made a tabula rasa of the human spirit, I applaud and admire this creative destruction. “ Haussmann was not, however, above the struggle between modernity and tradition, science and sentiment. Subsequently lauded or condemned as the apostle of modernity in urban planning, he could do what he did in part because of his deep claims upon tradition. “If Voltaire could enjoy the spectacle of Paris today, surpassing as it does all his wishes,” he wrote in his Mémoires, “he would not understand why Parisians, his sons, the heirs of his fine spirit, have attacked it, criticized it and fettered it. “ He appealed directly to the tradition of Enlightenment rationality and even more particularly to the expressed desire of writers as diverse as Voltaire, Diderot, Rousseau, and Saint-Simon—and even of socialists like Louis Blanc and Fourier—to impose rationality and order upon the chaotic anarchy of a recalcitrant city. The Haussmannization of Paris, suggests Vidler, carried the “techniques of rationalist analysis and the formal instruments of the ancien regime, as refurbished by the First Empire and its institutions, to their logical extreme.”17 It was, I suspect, in part because of these roots in tradition that Haussmann’s works gained the acceptance they did. In addition to About, several authors in the influential Paris Guide of 1867 (written by eminent authors to highlight the Universal Exposition of that year) praised Haussmann’s works in exactly these terms.

But Paris had also long been dubbed a sick city. Haussmann could therefore also appear in the guise of surgeon:

After the prolonged pathology, the drawn-out agony of the patient, the body of Paris, was to be delivered of its illnesses, its cancers, and epidemics once and for all by the total act of surgery. “Cutting” and “piercing’ were the adjectives used to describe the operation; where the terrain was particularly obstructed a “disembowelling” had to be performed in order that arteries be reconstituted and flows reinstated. The metaphors were repeated again and again by the pathologists, the surgeons, and even by their critics, becoming so firmly embedded in the unconscious analogies of urban planning that from that time the metaphor and the scientific nature of the action were confused and fused.18

The metaphors of “hygienic science” and “surgery” were powerful and appealing. Haussmann’s representational strategy when approaching the metabolic functions of the city—the circulation of air, water, sewage—was to cast the city as a living body whose vital functions must be cleansed. The Bois de Boulogne and Vincennes were fondly referred to as the giant lungs of the city. But Haussmann more generally saw the city dispassionately as an artifact that could be understood and shaped according to mechanical, natural scientific principles and techniques. The towers from which the triangulation of Paris proceeded symbolized a new spatial perspective on the city as a whole, as did Haussmann’s attachment to the geometry of the straight line and the accuracy of leveling to engineer the flows of water and sewage. The engineering science he put to work was exact, brilliant, and demanding; “the dream” of Voltaire and Diderot had, as Hugo would have it, “learned to calculate,” or, as Carmona prefers to put it, the dreamer (Louis Napoleon) found someone (Haussmann) who could calculate. But Haussmann also tried, as we have seen, to pander to sentiment, even to engineer it—hence the elaborate street furnishings (benches, gas lights, kiosks), monuments, and fountains (like that in the Place Saint-Michel), the widespread planting of trees along the boulevards, and the construction of Gothic grottoes in the parks. He sought to reimport romance into the details of a grand design that spelled out the twin ideals of Enlightenment rationality and imperial authority.

But if the body of the city was being radically reengineered, what was happening to its soul? The responses to this question were clamorous and contentious. Baudelaire, for example, who knew only too well the “natural pleasure in destruction,” could not and did not protest the transformation of Paris. His celebrated line “Alas, a city’s face changes faster than the heart of a mortal” was critically directed more at the incapacity to come to terms with the present than at the changes then occurring. And for those concerned with hygiene (and in particular the containment of cholera that did serious damage in 1848–1849, then reappeared, less virulently, in 1853–1855 and 1865), the reengineering could be welcomed as a form of purification of both the body and the soul. But there were many who were visceral in their condemnation. Paris was dying under the surgeon’s knife, it was becoming Babylon (or, worse still, becoming Americanized or like London!). Its true soul and essence were being destroyed not only by the physical changes but also by the moral decay of the fête impériale.

Lamentations, more often than not laced with nostalgia, were everywhere to be heard. The destruction of old Paris and the evisceration of all memory were frequently evoked. Zola inserts a telling scene in La Curée (The Kill). A former workman member of a commission to assess compensation for expropriation visits a neighborhood where he once lived as a youth. He is seized with emotion when he sees the wallpaper of his old room and the cupboard where he “put by three hundred francs, sou by sou,” exposed in a building under demolition. This was a theme that Daumier invoked more than once. Saccard, on the other hand, “seemed enraptured by this walk through devastations.… He followed the cutting with the secret joys of authorship, as if he himself had struck the first blows of the pickaxe with his iron fingers. And he skipped over the puddles, reflecting that three millions were awaiting him beneath a heap of building rubbish, at the end of this stream of greasy mire.” Nowhere is the brazen joy of creative destruction better invoked than in this extraordinary novel of Haussmanization in all its crudity.19

But nostalgia can be a powerful political weapon. The royalist writer Louis Veuillot invoked it to great effect in his influential Les Odeurs de Paris. Contemplating the destruction of the house in which his father had been born, he writes: “I have been chased away; another has come to settle there and my house has been razed to the ground; a sordid pavement covers everything. City without a past, full of spirits without memories, of hearts without tears, of souls without love! City of uprooted multitudes, moveable heaps of human rubble, you can grow and even become the capital of the world, but you will never have any citizens.” Jules Ferry (1868), in his dissection of Haussmann’s creative accounting, wept copious (and certainly opportunistic, if not crocodile) tears “for the old Paris, the Paris of Voltaire, of Diderot and of Desmoulins, the Paris of 1830 and of 1848,” when confronted with “the magnificent but intolerable new residences, the affluent crowds, the intolerable vulgarity, the appalling materialism, that we are leaving to our descendants.”20 Haussmann almost certainly had this passage in mind when he defended his works as being precisely in the tradition of Voltaire and Diderot. In one of his last works, published in 1865, Proudhon saw a city destroyed physically by force and madness, but insisted that its spirit had not been laid low, that the Paris of old, buried beneath the new, the indigenous population rendered invisible by the flood of cosmopolitans and foreigners, would arise phantom-like from the past and evoke the cause of liberty. For Fournel, as well as for many others, the problem was the monotony, the homogeneity, and the boredom imposed by Haussmann’s geometrical attachment to the straight line. Paris would soon be nothing other than a giant phalanstère, Fournel complained, in which everything would have been equalized and flattened to the same level. The Paris of multiplicity and diversity was being erased and replaced by a single city. There was only one street in Paris—the Rue de Rivoli—and it was being replicated everywhere, said Fournel, which perhaps explains Hugo’s cryptic response when asked in exile if he missed Paris: “Paris is an idea,” he said, and as for the rest, it is “the Rue de Rivoli, and I have always loathed the Rue de Rivoli.”21

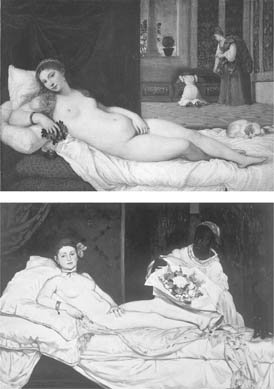

Figure 91 The spectacle of the demolitions—for the Boulevard de Sebastapol (above by Linton and Thorigny) and the rue de Rennes (below, by Cosson, Smeeton, and Provost)—was frequently recorded in lithographs of the time.

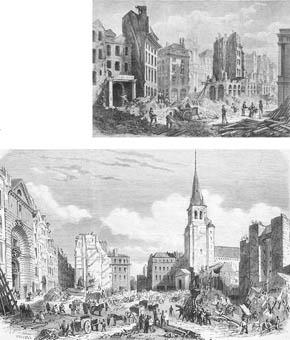

Figure 92 In these two cartoons, Daumier takes up the theme of nostalgia for what has been lost through the changes that Haussmann wrought. In the first the man is surprised to find his house demolished, and comments that he seems to have lost his wife, too. In the second, the man complains of the insensitivity of Limousin workers, who have no respect for memory as they tear down the room in which he spent his honeymoon.

It is not clear, of course, how much of this was a genuinely felt sense of loss and how much merely a tactical move (as I suspect it was in Ferry’s case) by monarchists or republicans to invoke some past golden age as a means to attack imperial rule. But Haussmann’s works were only one focus. The disappearance of older trades, the rise of new employment and ownership structures, the emergence of the credit institutions, the dominance of speculation, the sense of time-space compression, the transformations in public life and spectacle, the gross consumerism (lamented in the Goncourts’s journal), the instability of neighborhoods through immigration and suburbanization—all gave rise to a grumbling sense of loss that could easily erupt into full-fledged anger at the way the new Paris was superseding the old. Those who got left behind, like Baudelaire’s old clown, were unlikely to be mollified by tales of modernity and progress as both necessary and emancipatory for daily life.

Figure 93 The Rue de Rivoli, with its very straight-line alignment, was often viewed as symptomatic of everything that Haussmann was about. Hence Hugo’s comment from exile that Paris was still a great idea, but it all seemed to have physically become like the Rue de Rivoli, and “I loath the Rue de Rivoli.”

How to read all of this was the problem. Certainly something had gotten lost. But what was it, and should it really be the focus of that much regret? Consider, in this light, Baudelaire’s prose poem Loss of a Halo.22 Baudelaire records a conversation between a poet and a friend who surprise each other in some place of ill repute (much as actually happened, according to the Goncourts’s journal, when Baudelaire, coming out of a bordello, bumped into St. Beuve, who was going in, St. Beuve was so entranced that he changed his mind and went drinking with Baudelaire instead). The poet explains that, terrified of horses and vehicles, he hurried across the boulevard, “splashing through the mud, in the midst of seething chaos, with death galloping at me from every side” (a tension given visual form in Daumier’s splendid rendition of “the new Paris”—see figure 27). A sudden move caused his halo to slip off his head and fall into “the mire of the macadam.” Too frightened to pick it up, he left it there but finds he enjoys its loss because now he can “go about incognito, be as low as I please and indulge in debauch like ordinary mortals.” Besides, he takes a certain delight in the thought that “some bad poet” might pick it up and put it on.

Much has been said about Loss of a Halo. Wohlfarth records “the shock of recognition” in the image when juxtaposed with the Communist Manifesto: “The bourgeoisie has stripped of its halo every occupation hitherto honored and looked up to with reverent awe.” Capitalism “has converted the physician, the lawyer, the priest, the poet, the man of science, into its paid wage laborers.” To Wohlfarth, the poem signifies “the writer’s plight amidst the blind, cut-throat laissez-faire of the capitalistic city: the traffic reduces the poet in his traditional guise to obsolescence and confronts him with the alternative of saving his skin or his halo.” What better way to summarize the dilemma of the craft workers in the revolution of 1848? But Berman takes interpretation in another direction.23 He focuses on the traffic:

The archetypal modern man, as we see him here, is a pedestrian thrown into the maelstrom of modern city traffic, a man alone contending against an agglomeration of mass and energy that is heavy, fast and lethal. The burgeoning street and boulevard traffic knows no spatial or temporal bounds, spills over into every urban space, imposes its tempo on everybody’s time, transforms the whole modern environment into “moving chaos.” … This makes the boulevard a perfect symbol of capitalism’s inner contradictions: rationality in each individual capitalist unit leading to anarchic rationality in the social system that brings all these units together.

But those who are willing to throw themselves into this maelstrom, to lose their halo, acquire a new kind of power and freedom. Baudelaire, says Berman, “wants works of art that will be born in the midst of the traffic, that will spring from its anarchic energy … so that ‘Loss of a Halo’ turns out to be a declaration of something gained.” Only a bad poet will try to pick up the halo of tradition and put it on. And behind that experience Berman sees Haussmann, that archetype of the capitalist developer, the archangel of creative destruction. The poem is itself a creative product of the transformation of Paris, as is Daumier’s representation.

Wohlfarth sees it differently. It is no accident that the poet ends up in a place of ill repute. Here “Baudelaire foresees the increasing commercialization of bourgeois society as a cold orgy of self-prostitution.” That image also echoes Marx on the degradation of labor under capitalism, as well as his thoughts on the penetration of money relations into social life: “Universal prostitution appears as a necessary phase in the development of the social character of personal talents, capacities, abilities, activities.”24 Baudelaire’s fascination with the prostitute—simultaneously commodity and person through whom money seems to flow in the act of sex—and the dissolution of any other sense of community save that defined by the circulation of money is beautifully captured in his “Crepuscule du Soir”:

Against the lamplight, whose shivering is the wind’s,

Prostitution spreads its light and life in the streets:

Like an anthill opening its issue it penetrates

Mysteriously everywhere by its own occult route;

Like an enemy mining the foundations of a fort,

Or a worm in an apple, eating what all should eat,

It circulates securely in the city’s clogged heart.25

The city itself has become prostituted to the circulation of money and capital (see the Gavarni cartoon, figure 40). Or, as Wohlfarth concludes, the place of ill repute is the city itself, an old whore to whom the poet “like old lecher to old mistress goes,” as the epilogue to Paris Spleen puts it. Having dubbed the city “brothel and hospital, prison, purgatory, hell,” Baudelaire declares: “Infamous City, I adore you.”

The tension that Haussmannization could never resolve, of course, was transforming Paris into the city of capital under the aegis of imperial authority. That project was bound to provoke political and sentimental responses. Haussmann delivered up the city to the capitalists, speculators, and moneychangers. He gave it over to an orgy of self-prostitution. There were those among his critics who felt they had been excluded from the orgy, and those who thought the whole process distasteful and obscene. It is in such a context that Baudelaire’s images of the city as a whore take on their particular meaning. The Second Empire was a moment of transition in the always contested imagery of Paris. The city had long been depicted as a woman. Balzac (see chapter 1) saw her as mysterious, capricious, and often venal, but also as natural, slovenly, and unpredictable, particularly in revolution. The image in Zola is very different. She is now a fallen and brutalized woman, “disemboweled and bleeding,” the “prey of speculation, the victim of all-consuming greed.”26 Could so brutalized a woman do anything other than rise up in revolution? Here the imagery of gender and of Paris formed a strange connection—one that boded ill, as we shall see, for both women and the city in 1871.