After studying the topic of gangs in this region for nine years, I was grateful to have the opportunity to do an ethnographic update after putting together a historical puzzle that comprises this chapter.1 Gangs of Mexican descent did not just emerge from El Paso—they created a style of resistance during a timeframe of exclusionary policies and an obsession with using this population for its labor. It was the first and a half to second generation of youth who joined together to fit in. Walking the neighborhoods in Chihuahuita and El Segundo Barrio one hundred years after revolutionary tactics were first inspired offers a first-hand observation of a particular place and how it has changed over time.2 Along El Paso Street, the small shops are filled with pedestrians moving from store to store, browsing and purchasing items. The street continues to the international bridge known as Paso del Norte that was built in the 1800s to connect the United States with Mexico. The Spanish language is present everywhere, from the music playing in the background to the conversations occurring around me. There is no tension in the air. There are no fights or gun shootouts. This is El Paso, one of the safest large cities in the United States, situated adjacent to Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, which has recently moved past one of the most violent periods in its history.

As I walk further into the neighborhood, away from the international shopping strip, the heat keeps most residents who are home inside. The light sound of music emanates from windows covered with bars. Occasionally older men or women sit on the front stoops of their homes or apartment doors. Four housing projects are scattered throughout these two neighborhoods. Many of the buildings possess some amazing murals, many of which have been chronicled and featured as one the key sights to see in El Paso.3 I walk into the library to cool off from the heat, where a free lunch program offers food to children and their families. I venture back outside and observe three Latino police officers talking to an older man who appears to be of Mexican descent. They arrest the man and place him in the back of the police van. I think about how in the 1950s each block was controlled by a gang, but as I walk block after block I do not encounter one group of youths or adults who confronts me. I am aware that if I were to be bothered or attacked, it would defy current data trends. I continue to move through the neighborhood, taking pictures, writing notes, and observing residents interact.

Gang scholar James Diego Vigil’s concept of multiple marginality is one of the central frameworks for explaining the development of gangs.4 Vigil states, “Multiple marginality encompasses the consequences of barrio life, low socioeconomic status, street socialization and enculturation, and problematic development of self-identity. These gang features arise in a web of ecological, socioeconomic, cultural, and psychological factors.”5 Gangs exist on the margins of society in terms of class, education, politics, and social constructions of race. For Mexican Americans, gangs first emerged among the second generation, who were struggling to assimilate into U.S. culture. The groups identifying as gangs lack political power and domestic control, and they offer youth protection, identity, and opportunities for resistance, yet the behaviors highlight a generational and societal disconnect from mainstream officials and institutions. Agents of the state do not classify groups with social power as gangs. In the border region, there have been strategies to resist marginalization. Understanding the process of resistance to marginalization requires a revisionist analysis of history that continues from chapter 1.

The Creation of Pachuquismo and the Rise of the Ku Klux Klan

Researchers have acknowledged that the geographic region of El Paso possesses a style of culture known as pachuquismo as early as the middle of the Mexican Revolution, which later influenced residents in Los Angeles, California, and other locations in the Southwest. Frederic Thrasher, considered the first gang researcher, reported how a man named Roy Dickerson gave him the following account in 1924:

In the Mexican section of El Paso is a group of three or four hundred Mexican boys composed of from twenty to twenty-five gangs, each with its separate leaders. These gangs have been growing steadily for eight or nine years and now embrace a rather seasoned and experienced leadership in all sorts of crime. Eighty per cent of their members are probably under fifteen years of age; most of the older boys are under eighteen. Stealing, destroying property, and all kinds of malicious mischief are their chief activities. In fact, these groups are almost literally training schools of crime and they seem to be related to each other in a sort of loose federation. For the most part, the boys do not go to school or do not work unless it be for an occasional day. Fifty of them have been sent to the State Industrial school, eight are in jail, twenty-five or thirty are being specially investigated, and about two hundred are under surveillance. These boys may be observed in their characteristic groups every evening on street corners and in vacant lots and alleys. The park, which is their favorite meeting place, with its double rows of tall hedges, its trees and shrubbery, affords them a good place to hide and to conceal their delinquencies.6

Based upon Thrasher’s footnotes, it was unclear who Roy Dickerson was or how he gathered information on El Paso gangs. He claimed gangs had existed since 1915 or 1916, which is difficult to verify based on the historical records. Raúl Tovares, a communications professor and author of Manufacturing the Gang: Mexican American Youth Gangs on Local Television, critiqued Dickerson’s claims on three points: 1) gangs were seen as a problem in the Mexican section of town [implying a lack of concern with white gangs]; 2) the groups were described as well organized, hierarchical, and having a criminal intent [not supported by data]; and 3) the argument may have been fabricated not just by the media [the theme of Tovares’s book] but by changing political, economic, and cultural values.7 Roy E. Dickerson comes up in a couple of other searches for the timeframe. In 1919, Dickerson was listed as the General Secretary of the Young Men’s Christian Association in Tucson, Arizona, for which he wrote an article titled “Some Suggestive Problems in the Americanization of Mexicans,” where he provided information on Tucson and El Paso. Dickerson stated Mexicans were an undercounted population largely concentrated in the Southwest with low levels of education (fifth grade), high dropout rates, little knowledge of the English language, poor pay, and living in homes often lacking a father or mother. Dickerson advocated “…the best efforts of our best citizenship must be given to these problems in a much more vigorous and effective way than has hithertofore been manifested.”8 Thus Dickerson’s article and comments to Thrasher may have reflected his method of advocacy or enhancing social control upon Mexican residents.

Possibly a more accurate description of gangs of the time was provided by El Paso historian Mario T. García, who mentioned a lack of organized crime in El Paso except for an occasional gang in 1919 and on rare occasions some residents participating in “dope rings.”9 One of these individuals, Manual Morales, reportedly participated in a dope ring that distributed drugs on both sides of the border from the Chihuahuita neighborhood. He was arrested for the illegal sale of opium. García found disproportionate police concentration, raids, and curfews in the Mexican neighborhoods as the police chief attempted to remove undesirables from the city. Such actions continued the ongoing discrimination against Mexicans, particularly in South El Paso, as reported by historian Miguel Antonio Levario.10 Moreover, Dickerson’s concerns about youth of Mexican descent not attending school or working does not reflect García’s findings regarding school segregation and reports of youth not being encouraged to attend school beyond the fifth or sixth grade.11 The schools primarily emphasized a curriculum geared towards teaching U.S. patriotism and preparation for manual labor.12

Similar to a lack of media panic suggested by Raúl Tovares, it was difficult to find any mention of gangs in the local newspapers from 1915 to 1924.13 Contrary to Dickerson’s statement to Thrasher, a 1919 El Paso Herald article titled “Oh Skinnay! The Gangs All Up in Court!” described a knife fight between regular boys, one of whom was described as “the red headed, freckled faced, titled nose boy” and another a tall and skinny boy, and they went by names such as “Fat” and “Peewee.”14 The judge placed the boys on probation for their behavior. Other newspaper articles from 1919 describe the country after World War I, the conflicts in Mexico, an editorial dislike toward Pancho Villa, local violence, and claims regarding El Paso becoming a center of lawlessness due to being adjacent to Juárez.15 According to Gaspar Cordero’s oral history interview from 1975, Gaspar was born in South El Paso in 1908 and reported that gangs in the 1970s were different from the 1920s because it was more “…like kids getting together, and one guy going up against another, but really nothing vicious. Maybe rock throwing and things like that—nobody ever got hit.”16 Such accounts merge with those of other gang scholars, who found that gangs often began as neighborhood groups and families simply providing protection for one another.17

Gang scholar James Diego Vigil reported that “the rise and formation of the gang subculture, to reiterate, revolves around the broader backdrop of culture conflict and choloization [i.e., the idea that gang members encounter greater difficulty acculturating than non–gang members] of much of the second-generation Mexican American population.”18 Vigil continued, “It was in El Paso, Texas, that the pachuco style originated, although it might be traced to Pachuca, Mexico, where baggy pants were common among males.” The word pachuco was considered by many to have been created to refer to individuals from El Paso, Texas, and it originated around the time of the Mexican Revolution.19 Thus, although the term gang has become politicized, the language, style, and mannerism of pachuquismo is well established as emerging from this geographic area. David Barker, who wrote one of the earliest articles on pachucos in 1950, received information from two of his interviewees who suggested the caló or Spanglish language originated among marijuana smokers and dope peddlers in the El Paso underworld and possibly by members of the 7-X gang. According to the timeline of El Paso gangs in appendix 2, the 7-X gang was one of the earliest groups, but it is unclear whether this organization could date back decades prior.

The caló language intertwined with a unique clothing style and demeanor. Many of the youth had a tattoo of a cross on the hand. In some of the earliest accounts of pachucos and pachucas, scholars argued how the mixing of cultures (American, Mexican, and Native American) and not belonging precisely to either culture resulted in the creation of pachuquismo, which is a hybridization of cultures.20 However, only a small number of Mexican American boys and girls participated in the pachuco style of language and dress. The entire Mexican culture was impacted by discrimination, but they did not passively accept second-class status. Anthropologist Laura L. Cummings emphasized that although pachucos have been analyzed primarily through a deviance lens, most of the youth were not gang members or criminals.21 It was a broader style and culture found within the working class, and it included females. They too had their own style of dress and participation in the use of caló.22

While marginalized Mexican American youth were creating a culture to resist colonization, El Paso’s elite Anglo residents were seeking to solidify control of formal institutions and social life. The Ku Klux Klan emerged during the early 1920s to capitalize on foreigner fears of Mexicans and Catholics. They encouraged a greater emphasis on Protestant morals. The Frontier Klan No. 100 Knights of the Ku Klux Klan was established in El Paso in 1921, and it began its recruitment efforts with prominent individuals in the community.23 Similar Klan developments were occurring across the nation, including Denver, Colorado.24 Klan membership experienced a “rebirth,” growing from 85,000 members nationwide in 1921 to somewhere between three and five million by 1925.25 By 1922, the electorate in El Paso had become primarily Anglo, consisting of many residents from the South and overwhelmingly middle class. Klan rallies were held on Mount Franklin, where ceremonial fires were lit. Klan membership in El Paso was estimated to include as many as 3,500 members, and it influenced all sections of the city.26 According to the Frontier Klansman, segregation between blacks and whites was enforced in El Paso, whereas in Juárez whites were reportedly bullied by blacks and the Mexican policeman did not care.27 The Frontier Klansman described a wedding ceremony in Deming, New Mexico, involving hundreds of Klansmen from El Paso and southern New Mexico. They received an unwelcome reception from the Mayor of Deming, for which the Klan threatened its growing presence in the southern New Mexico area and how it was targeting bootleggers and crooked politicians.

In addition to attempting to gain political control, the Frontier Klansman encouraged closing off the bridge that allowed residents to pass back and forth between Ciudad Juárez and El Paso. The author stated the following,

Is there a bridge closing issue in this town? No. There is an issue between cleanliness and immorality. Count your men, citizens. Make no mistakes. Juarez is a hell hole. It is all that is evil. Excuses don’t go. It is a nest of houses of prostitution. It is a street of low saloons. It is an open market for narcotics. It is unsanitary. It is a disease menace. The world knows it.28

The author continued to argue how U.S. citizens continued to be ruined by visiting this location across the border. However, tourism into Juárez was one of El Paso’s biggest sources of hotel income, thus continuing a sibling type of relationship between both cities.29 An estimated 419,000 tourists visited from El Paso to Juárez during the first year of prohibition, and a wide range of entertainment existed, both those of vice and mainstream family events. Increasing public pressure resulted in the closing of the border in 1923, and ongoing federal concerns led to the creation of the U.S. Border Patrol in 1924.30 Historian Kelly Hernández stated that Anglo American nativists played a crucial role in designing the National Origins Act of 1924, which introduced a nationality-based quota system that limited the number of immigrants allowed to enter the United States each year.31 The Act prioritized Europeans and excluded Asians. Agribusiness prevented nativists from putting Mexicans on the excluded list, but this was primarily because Mexicans were considered to be a temporary and marginal population that was needed for labor purposes. Nevertheless, the Border Patrol’s focus became the policing of Mexicans. Edwin M. Reeves’s oral history in 1974 described working as Border Patrol Officer in the 1920s and 1930s. He stated that any offense (e.g., liquor violation, narcotic violation, property crime, or illegal entry) required notifying different agencies from U.S. Customs, the narcotics division, or the local sheriff.32 A first offense for illegally looking for work resulted in a voluntary return, whereas individuals who had been apprehended two or three times were charged with a Section 1 offense, which resulted in the individual being sent to La Tuna Federal prison in Anthony, Texas, or to Leavenworth in Kansas.

In the early nineteenth century, border enforcement was primarily focused on Asians, but the influence of the Ku Klux Klan and prohibition ensured the focus remained on individuals of Mexican descent. Miguel Antonio Levario situates such acts of militarized segregation along the border as continually defining ethnic Mexicans as an enemy of the state that “…must be subdued lest their presence undermine the social, political, and cultural fabric of white America.”33 Conflict over smuggling and determining who was engaging in illegal activity was an early problem between the Border Patrol and Mexicans entering the United States. A colonel of the Border Patrol estimated that about eight officers and a hundred liquor smugglers were killed during the prohibition years.34 Another estimate during prohibition was 19 border patrol officers killed and 50 smugglers.35 Finally, a Border Patrol agent claimed in his autobiography that, between 1924 and 1934, agents killed 500 smugglers and lost 23 officers.36 Edward Langston’s dissertation described a number of gunfights resulting in death and the difficulty to quickly determine whether someone was crossing into the United States for work or for some illegal activity like smuggling drugs or alcohol.37 Most Border Patrol agents at the time were Anglo males between the ages of 20 to 40. Historian Kelly Hernández stated that the primarily white Border Patrol officers took vengeance upon the wider Mexican population if any of their agents were killed. She emphasized how the white Border Patrol men primarily enforced immigration laws upon poor, brown-skinned Mexican males.38

Although media reports were claiming that the Klan was decreasing in numbers, the Klan argued an increase in membership up to 3,000,000 “native-born, white, Protestant American citizens” nationwide.39 Eventually the Klan in El Paso encountered increased opposition from Catholics and Juárez politicians, and it struggled to maintain a secret society as one of the local El Paso newspapers threatened to publish a membership roster.40 By 1924, the Klan reportedly ceased to be a significant influence, and membership in Texas declined from 12,000 active members in 1927 to less than 2,500 a year later.41 It is unclear how the Klan’s membership patterns were affected in New Mexico during this time period.

Despite a nationwide decrease in Klan membership, racist portrayals continued against the region’s residents, as did patterns of keeping Mexicans as manual laborers. In July 1925, Harper’s Monthly Magazine, out of New York, described as “the oldest general interest monthly in America,” published an article titled “New Mexico and the Backwash of Spain.” In this article, the author Katharine Fullerton Gerould criticized residents by stating, “New Mexico is, all in all, a wild and uncivilized state. Life is cheap, ignorant Mexican juries are easily packed, and if a sheriff grows (which seldom happens) too zealous on behalf of law and order, it is pretty difficult, in the end, to find out who killed him.”42 New Mexico was described as corrupt and un-American for allowing the Spanish language to continue. Fullerton Gerould confusingly wondered why the dominant white race had failed in this area compared to other parts of the Southwest. The Mexican sheep-herder received an even more negative depiction from Fullerton Gerould: “But he is too ignorant, too mongrel, too indolent a creature to win any long-drawn-out contest, or even to express in his own person the perpetual question, ‘What are you going to do about me?’ We are not going to do anything about him except wait for the generations slowly to oust him.”43 Fullerton Gerould described pueblo Indians more positively compared to Mexicans, despite the fact that this racial group continually being denied federal and state citizenship.44

Several authors have reported better race relations in New Mexico and El Paso compared to other sections of the country and Texas overall, but this does not mean problems were non-existent.45 Mexicans continued to be marginalized, and blacks were a numerically small population. For example, a police officer in El Paso reported to the El Paso Herald in 1929 how lynchings were a problem in other parts of the South but there were no issues in El Paso, “a good-sized country town,” because, Sergeant Mathews reported, “The negroes here attend strictly to their own business.”46 The Sergeant Mathews did recall an incident where a black man asked a young white woman on a date, which resulted in him receiving a 60-day sentence on a chain gang for disturbing the peace. Mathews said that, about a month later, the man was found dead on the other side of the river. Despite the infrequent lynching of African Americans, new research on mob violence against Mexicans in the Southwest by historians William Carrigan and Clive Webb in their book Forgotten Dead highlights a significant number of deaths that occurred from 1848 to 1928, which conservative estimates place in the thousands.47 Many of these occurred in New Mexico and particularly in Texas. Thus, racial contestation was not enough to alter whites becoming the elite, Mexicans being pushed to the bottom, Asians being excluded, Native Americans being isolated, and blacks being kept numerically less prevalent.

The Rise of Organized Crime in Ciudad Juárez and the United States

Prohibition in the United States created the perfect environment to supply the needs of U.S. residents with goods emerging from the Mexican side of the border. From 1920 to 1934, legalized gambling in the Mexican state of Chihuahua kept tourism the center of politics in Mexico.48 Nevertheless, federal officials often opposed such practices, which led to divisions between Chihuahua and the capital in Mexico City, resulting in the international bridges between El Paso and Ciudad Juárez occasionally being closed to regulate businesses. Federal immigration and customs officials controlled the bridge and, due to conflicts, Juárez municipal leaders created their own police to protect their interests. In addition to federal officials, conflicts also emerged with Mexican military soldiers, many of whom took advantage of their positions to reap some of the gambling proceeds.49 Much of the city’s vice had been pushed to Ciudad Juárez with at least 40 percent of businesses operated by individuals with non-Spanish surnames.50 Robin Robinson, in her dissertation at Arizona State University, stated:

While the elites competed over gambling, everyone else struggled for the remaining vice. No matter who ruled Juarez, violence and corruption plagued the city. As a border town, Juarez possessed all the predictable vices. The prohibition era increased demand for already practiced public gambling and bootlegging. The existence of these enterprises required official sanction, legal or otherwise. At the top, politicians and generals took advantage of their positions to enrich themselves through kickbacks, partnerships, and “fees.” In the middle, local businessmen produced and distributed the liquor smuggled across the border. At the bottom, low-level police and border agents practiced extortion, bribery, and shake-downs.51

Nicole Mottier, a Latin American historian, estimated that by 1926, two thirds of all business in Ciudad Juárez catered to tourism and employed a large proportion of the workforce.52 She argued that from 1928 through 1934, Enrique Fernández and La Nacha led the first organized crime organization to influence local and state politics. Anthropologist Howard Campbell concurred, saying that La Nacha, or the “Dope Queen,” was first employed by Enrique Fernández and her real name was Ignacia Jasso González.53 According to Mottier, in 1930, members of the Quevado family ran drugs and received protection because they also held positions of political power. The influence of the drug market occurred at a time of economic instability and political fluctuation. Mottier outlined four types of gangs based on degrees of responsibility, authority, power, and income: 1) the politically and economically connected; 2) those in charge of dealing large-scale shipments, many of whom were local officials; 3) the owners of opium dens with less protection; 4) pistoleros who killed rival gang members and the Juárez madams who were bold drug traffickers. She argued that the pistoleros were the majority of gang members and the most frequently caught. Mottier’s conception of gangs more frequently overlaps with the organized crime literature rather than that of U.S. gangs.54 However, even Campbell argues drug trafficking organizations should be conceptualized as more shifting, contingent, and temporal in that alliances, conflicts, imprisonment, and death continued to keep these organizations in flux. Thus, rather than a pyramidal structure, cartels should be conceived more as rectangular.

In the United States, sociologist Howard Abadinsky reported that, prior to prohibition, organized crime primarily consisted of corrupt city officials or police officers, whereas afterward it led to a new form of criminal organization.

In order to be profitable, the liquor business, licit or illicit, demands large-scale organization. Raw material must be purchased and shipped to manufacturing sites. This requires trucks, drivers, mechanics, warehouses, and laborers. Manufacturing efficiency and profit are maximized by economies of scale. This requires large buildings where the whiskey, beer, or wine can be manufactured, bottled, and placed in cartons for storage and distribution to wholesale outlets or saloons and speakeasies. If the substances are to be smuggled, ships, boats, and their crews are required…and there is obvious need to physically protect shipments through the employment of armed guards.55

Such ventures required association and connections with legal institutions. It was during prohibition that several crime syndicates became organized in Chicago, Detroit, and New York City. Street gangs on the other hand were often conceived as poorly organized youth groups living in poverty and existing in several cities such as Boston, Cleveland, Denver, El Paso, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, and St. Louis.56 Along the U.S.-Mexico border, during prohibition, liquor traffic remained in local hands, and it was not taken over by U.S. crime syndicates.57 Such a finding is supported by a different culture and language that was required along the U.S.-Mexico border region, which the primarily European organized crime syndicates did not possess. This does not mean, however, that U.S.-based companies with pre-existing financial and corporate ties did not play a role in distribution; rather, it simply was not controlled by U.S.-based organized crime families.

From 1929 to 1939, the United States fell into the Great Depression, and Juárez politicians and business leaders pushed to capitalize on this market potential. Robinson stated:

The U.S. public and less informed government officials of the 1920s placed much of the blame for border vice problems on Mexico and its citizens. Americans believed Mexicans, and border Mexicans in particular, to be morally deficient, receptive to and encouraging of vice, and possessing a government without concern for the health and morality of its citizens. Another general misconception is that prohibition created a liquor smuggling problem of overwhelming proportion.58

During this time, the Quevado family’s struggle for leadership resulted in a number of deaths of people working for Fernández in 1933 and 1934, and eventually Fernández’s own death that same year. Alcohol sales were made legal again in El Paso in 1933, and the U.S. prohibition ended in 1934, ending much of Juárez’s tourism.59 The Commissioner of Prohibition estimated that possibly only one twentieth of smuggled liquor was seized.60 The administration of Mexico’s President Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–1940) focused on eliminating gambling and prostitution. After the death of Fernández, Campbell reported that La Nacha developed her enterprise to last for the next 50 years by shifting from the sale of alcohol to the distribution of marijuana and heroin. Her ability to maintain stability may have been influenced by her philanthropy in helping the poor and disenfranchised by financing an orphanage, offering a free breakfast program, and never becoming over-zealous.61 By 1936, the drug trade was reportedly led by members of the Quevedo family. This family too lost political power as an individual named Talamantes took over in 1937 and then targeted Quevedo’s gambling empire.62 Throughout this period there were back and forth stances on gambling, in which it was occasionally stopped for moral reasons and then renewed due to financial needs.63

Poor Living and Working Conditions Coincides with Increased Attention on Gangs

In 1930, the sociologically trained Emory Bogardus outlined the context for differential outcomes resulting from Mexican and Mexican American populations being segregated to live on the other side town across the railroad tracks. Bogardus stated the reasons for segregation, included Latinos not wanting to become citizens, reaping the benefits of the United States without citizenship, loyalty to their native country, and continuing to be treated as greasers and seen more as laborers than as “full-fledged human beings” when attempting to fit in.64 Neighborhood segregation resulted in schools that were primarily Mexican and did not receive the same resources and opportunities. Anthropologist James Diego Vigil elaborated on how Mexican immigration in the 1920s consisted of 1.5 million to 2 million residents who were being utilized for cheap labor along the southwestern railways and farms.65 The railroad brought the pachuco culture westward in the 1930s and 1940s. There were several notable Chicano leaders from the Ciudad Juárez–El Paso area who had since moved to Los Angeles, including Oscar Acosta, Bert Corona, Ruben Salazar, and Luis Rodriguez. Bert Corona, the influential labor and community activist, observed that many individuals from El Paso moved to Los Angeles during the Great Depression because there were more jobs in California.66 Thus, individuals along the line from Ciudad Juárez and El Paso to Tucson and on to Los Angeles shared cultural influences.67

The zoot suit generation, along with its music and style, were captured perfectly in Anthony Macías’s book Mexican American Mojo: Popular Music, Dance, and Urban Culture in Los Angeles, 1935–1968.68 Similar to others, Macías described how the style in Los Angeles emerged from El Paso. Don Tosti, an artists who had become successful in Los Angeles, was born and raised in the Segundo Barrio of El Paso. His hit “Pachuco Boogie” later went on to influence the work of another famous musician of the time, Lalo Guerrero. Musicians during this period created a blended style from jazz, blues, doowop, Motown, and Afro-Latin music. Public officials often looked upon the excitement and style of this culture with disdain. Early pachuco writer David Barker even suggested that the El Paso Police Department may have threatened prison sentences on some youth unless they left town.69 The State Juvenile Training School, located 582 miles away in Gatesville, Texas, housed at least sixty boys from El Paso each year.70

In New Mexico, racialized histories existed in a state that avoided at all costs any discussion of racial inequality. Political leaders continued to fear that the majority population (mestizos and Native Americans) would eventually no longer tolerate white Anglo domination.71 As tourism became identified as New Mexico’s industry of the future, the title of “Land of Enchantment” was adopted in 1937.72 Illusions of inclusiveness hid the power of wealth and social standing that dictated the creation of a Spanish American culture. From the point of time of pursuing statehood, to adopting a tourist slogan, the term Mexican began to be used by state officials as a derogatory term. Even in El Paso, Texas, when officials desired to give the population a positive connotation, they used the term Spanish or Latin.73

The news reporting of gangs began to increase in frequency after 1936 as captured by this article in El Paso Herald-Post report, titled “South El Paso Gang Scored.”74 The article’s author reported how the secretary of the Sacred Heart Church believed gangs were endangering the lives of residents near their church. The gang had destroyed a $300 fence, and drug addicts had gathered near the church and planned robberies. Historian Mario T. García describes how the Sacred Heart Church was located centrally in the segregated Chihuahuita neighborhood where Mexicans had lived in slum-like conditions.75 In response to the problematic conditions, a tenement ordinance was put into effect in 1930 and housing projects were initiated in 1933.76 On March 12, 1940, a “gang clean-up” was issued, and twelve “Mexican speaking youths” between the ages of 16 and 22 were arrested. The youth were described as not attending school, playing dice, hanging out on street corners, and being a nuisance.77 In 1941, raids continued as thirty-two men were jailed during additional “clean-up campaigns” in South El Paso.78 Pedestrians and automobile drivers reported feeling unsafe and filed complaints with the police department. Police officers confiscated brass “knucks,” butcher knives, pocket knives, and clubs. Police charged the youth with vagrancy. The Captain of the Sheriff Department believed most of the petty thefts, breaking into parked vehicles, and simple assault cases were a result of these gangs. Arrests continued during the spring and throughout the summer; on August 14, 1942, the El Paso Herald-Post described a “War on Gangs,” during which thirteen young men between the ages of 17 and 23 were arrested.79 Despite law enforcement efforts, the Captain believed gangs would be an ongoing problem.

Regardless of an increase in media attention, the overall proportion of youth who were involved in groups identified as gangs appears to be minimal. Jamie F. Torres’s personal narrative about growing up in El Segundo Barrio from 1925 until 1943, prior to being drafted into the Navy to fight in World War II, only included one paragraph about gangs in a book 514 pages long.80 He notes, “We did have our share of young punks that can be found in all dense neighborhoods,” but he had no personal recollection of gangs and he didn’t recall any mention of them in the newspapers. Although he agreed the term pachuco was coined to reflect residents from El Paso, the zoot suit presence appeared to become more of a fad in the early 1940s. His own life reflects doing well in segregated schools and later attending college. After leaving the military, Torres attended college through the GI Bill and had a successful engineering career. Although the historical record for gangs in El Paso between 1916 and 1936 was sparse, the same cannot be said about the timeframe afterward, when the discussion of gangs became a prominent issue. A noted change occurred among these groups during this time frame: organizing for defense in the early days shifted into rivalries among neighbors who lived in different neighborhoods.

Enhanced punishment designed to target gangs increased in Los Angeles, California, after the June 1943 Zoot Suit Riots. This event also intensified tensions between U.S. soldiers and individuals of Mexican descent in other cities such as Denver, Colorado.81 The Zoot Suit Riots brought pachucos nationwide attention.82 Sociologist Emory Bogardus argued that most Zoot Suiters and Mexican American youth were not gang members, and U.S. society needed to demonstrate greater racial tolerance and understanding.83 He chastised U.S. sailors involved in the riots for taking the law into their own hands and police officers for creating a feeling of injustice. Carey McWilliams participated in a legal case preceding the riots (Sleepy Lagoon case) and served on a committee to study the reasons for why the riot occurred.84 He emphasized the discriminatory actions of law enforcement officials, military officers, and the general public in their response to Mexican Americans during the Zoot Suit Riots. He challenged the inflammatory news articles of the Los Angeles Times. McWilliams stated, “The riots were not an unexpected rupture in Anglo-Hispano relations but the logical end-product of a hundred years of neglect and discrimination.”85

By World War II and after the Zoot Suit Riots, Macías referred to Los Angeles as the nation’s pachuco capital, and the early notoriety of El Paso seemed to be forgotten.86 During World War II, officials in El Paso began developing its closest relationships in history with Ciudad Juárez.87 Mexico joined the United States as an ally and provided a steady flow of war materials. Fort Bliss grew from 3,000 soldiers in 1939 to 40,000 by 1944 and was considered the third largest military base in the country. Although no clear accurate numbers were available due to being categorized as white instead of black, it was estimated that more Mexican Americans served in the military during World War II and received medals of valor and other accomplishments than any other racial or ethnic group.88

In July 1942, the Bracero Program began, which allowed U.S. farm owners to hire Mexican agricultural workers.89 The numbers grew annually from 4,200 in 1942 to 238,500 by 1945, including 121,350 Mexican workers repairing railroad tracks. As a state, Texas was not allowed to have Braceros until 1947 due to the Mexican government condemning this state for its unfair treatment of Mexicans. Despite this ruling, El Paso businesses constantly negotiated opportunities to utilize undocumented labor. Wartime efforts began to improve health standards, although the overall health status of most residents living along both sides of the border was very poor.90 There were higher rates of sexually transmitted diseases, tuberculosis, typhus, typhoid fever, whooping cough, and infant and maternal mortality. Winifred Dowling, in his dissertation at the University of Texas at El Paso, stated:

Venereal disease was one of the greatest health concerns along the U.S.-Mexico border. It was exacerbated by the growing number of U.S. military men stationed near the border. With so many young men there came young women. Leaders on both sides of the border took a number of steps, including the Pan American Sanitary Bureau’s emphasis on venereal disease.91

Juárez closed its legal zone of prostitution in 1942, and El Paso did the same in 1941, yet much of the activity continued underground. The source of much of the poor health was attributed to poverty and horrible conditions in South El Paso. Once the war ended, relations between the two countries became strained once again. In addition, returning Mexican American veterans began to realize that their fight for U.S. freedoms did not ensure this treatment was provided once they returned home. Still often treated like second-class citizens, Mexican American servicemen started a reform-focused group called the American G.I. Forum, which was focused on obtaining equal citizenship rights.92

Gangs of the 1950s—El Paso’s Peak Period and the Arrival of the Bicycle Priest

The summer of 1950 began with a series of investigations into gangs. An El Paso Herald-Post reporter stated that a grand jury had begun investigating juvenile gangs.93 The grand jury noted that while gangs had been primarily confined to South El Paso, these groups were appearing in the northern section of the city and many of the members came from prominent families. Most of the members knew each other through nicknames, and the gangs emphasized the importance of secrecy. Informants encountered vengeance, often in the form of the mark of a large cross scratched onto informers’ foreheads. The newspaper reporter stated that several residents told him they were living in terror of these organizations and the police offered little protection. Gang activities ranged from destroying lawns, vandalism, throwing rocks, molesting girls, and racing down streets. Similar to most news stories, there was very little or no data presented as to rates, total numbers, or comparisons among various years or groups. Nevertheless, sensational stories continued. A grocery store display window had a large rock thrown threw it with a note written from the “Dukes.”94 Duke members denied involvement. Police broke up potential rumbles between the X-2 gang and the 7–11 gang and arrested several youths for vagrancy and loitering, booking them into the county jail.

A probation officer called for a meeting between county and city law enforcement agencies in an attempt to create a plan to combat gangs and “rat packs.”95 Parents were urged to supervise their children, and efforts were focused on gathering intelligence on gang-involved youth and publicizing their names through the radio and newspaper when taken into custody. The El Paso County Grand Jury felt they had conducted an exhaustive survey of the juvenile situation and believed that, unless officials corrected the existing conditions, there would be cause for alarm. Another story the same day reported that several members of the Dukes who attended El Paso High School were arrested for carrying rifles, zip guns, and an assortment of knives and home-made blackjacks. Fights centered between members of the X-2 gang and the 7–11 gang of East El Paso. During the summer of 1950, a news story reported a bigger boy beating a smaller boy to be initiated into the group in front of a crowd of older youth.96 They all wore white shirts. In another section of town, police found a sign that read “7–11 has been here.” The police and city leaders were looking into how to break up groups they called “rat packs.” The next day, a judge told parents to take charge of their kids to prevent fights and mischief.97 The gangs of the time were considered to be in open warfare, and they included several Southside gangs (7-X gang, OK-9s, Old Fort Bliss gang, and Lucky 13s), whereas East El Paso was “terrorized” by the 7–11 gang.98 On the Northeast it was the Dukes and the female auxiliary group known as the Duchesses. Such feuds between gangs led to a 15-year-old boy being shot, stabbed, and dying from these injuries in December 1951.99

Such a context shaped the entrance of white Jesuit priest named Father Harold J. Rahm, S.J., who arrived in El Paso, Texas. on July 12, 1952; he brought with him little insight into the area but spiritual faith.100 He had spent the previous summer working in Cuba. Not entirely fluent in Spanish, he was given the task of serving as the assistant pastor for the Sacred Heart Church. In the early 1950s, Father Rahm reached out to youth and attempted to create a safe place where they could play sports and participate in church activities.101 He noticed that El Paso was separated into five areas (East, North, Northeast, South, and Sunset Heights), and he was assigned to work in South El Paso, the most deprived section of the city.102 At the time, the city had a population of around 250,000 residents, and Juárez had 150,000. South El Paso consisted of 30,000 residents: one or two of them were Anglo, and there were twenty black families, and the rest were Latin American. Father Rahm purchased a bicycle and rode around the neighborhoods and was invited into homes. He observed and was told about a wide variety of problems in the community involving issues such as domestic violence, health complications, interpersonal violence, officer-involved shootings, poverty, teenage pregnancy, unemployment, unsanitary housing, and many more difficulties. At first he was unsure how to be of best use, but he understood that the service organizations that existed were understaffed and underfinanced.

Father Rahm described how the community’s Latin Americans were divided into three groups: 1) American, 2) Chicano, and 3) Juareno. Americans were the most assimilated and smallest in number in South El Paso because they primarily lived in middle-class areas. Chicanos were the largest in number and many had one or both parents born in Mexico. Juareno’s had greater difficulty with the English language and were from Mexico. Within the city there was conflict between Anglos and Latins, but not between “Negroes” and Latins. Gang scholar James Diego Vigil reached a similar conclusion that gang culture emerged out of the Chicano culture’s opposition to the dominant culture.103 In El Paso as in Los Angeles, the largest number of gang-involved youth came from high-poverty neighborhoods, and many had disrupted families. Father Rahm first reached out to the fathers of the households. The kids played sports in the street and had nowhere to go for activities. During his bicycle travels, Father Rahm, found a deserted building and obtained the rights to purchase it. He and others cleaned up the building, and soon it opened as the Our Lady’s Youth Center. It averaged around 250 teenagers and children every day.104 Father Rahm utilized his previous experience visiting Boys Town, which was an internationally recognized boys’ home in Nebraska that began in 1917 to provide services to disadvantaged youth.

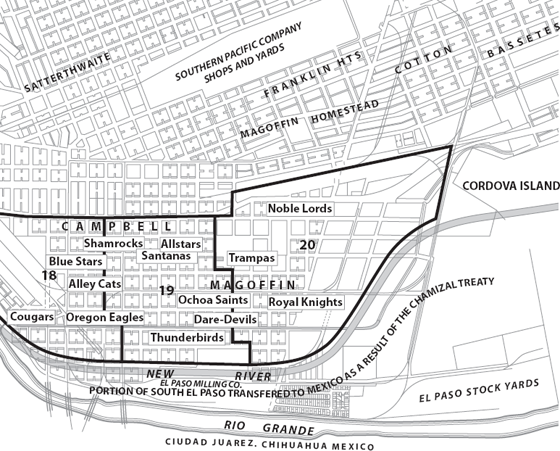

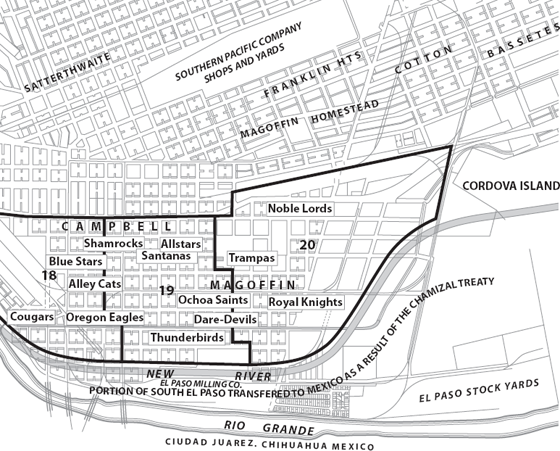

As the Our Lady’s Youth Center continued operations, Father Rahm realized that for the center to survive he would need to focus on gangs. The gangs consisted a variety of groups, the largest being the 4-Fs (Mesa Street), Little 9ers (Frontera Park), Lucky 13s (5th and Oregon), 14s (4th and St. Vrain), and 7Xs (Durango Street). South El Paso was divided into two with the 14-7X allies and the Lucky 13–9 allies (See Figure 4). Our Lady’s Youth Center existed in 13–9 territory. Throughout these neighborhoods there were small pockets of other gangs, such as the Charms, X9s, LMs, Terrengers, DDT’s, TPM, and Rebels. The names of the gangs largely emerged from the street where they existed and were primarily in English. One previous gang that was known as notorious was the K9s, whose members departed due to adulthood or prison incarceration. The neighborhoods and housing projects shaped which groups the youth joined. Residents at the Alamito Housing project became a 14. The youth who didn’t join were known as squares or independents.105 The smuggling of narcotics rarely influenced the youth, who were themselves loosely organized. Based on the notes and reports of the participant observers working with the gangs, Father Rahm described gang activities as follows: “Mostly gangs don’t do anything. They just sit around talking, arguing, bragging, telling stories. They make elaborate plans, which are mainly group phantasies that never happen. They drink, they take pills, they have parties, they talk about girls, and occasionally they fight.”106 The social worker assigned to each gang attempted to reduce conflict between the groups and help members to attain summer employment. The main conflict in the neighborhood continued to be between the 4-Fs and Lucky 13s. Father Rahm believed the Center had a positive impact with the 4-Fs, but little impact on the Lucky 13s or the Lucky 9s. He hoped the overall efforts of Our Lady’s Youth Center would help shine light on the needs of South El Paso.

By 1954, efforts to focus on gangs continued as detectives and probation officers visited Austin High School to talk with boys regarding a teenage theft ring involved in looting and stripping parked cars.107 The district attorney reported how the parents of these teenage boys might be called before a County Grand Jury. By 1956, an El Paso Herald-Post reporter stated that there was a presence of fifty organized gangs of teenagers, and that some of these groups had fifty to seventy-five members “roaming” the streets of El Paso.108 Their activities included beatings, stabbings, zip-gun shootings, thefts, burglaries, vandalism, auto-thefts, and drinking. During the year, one person had been shot with a zip gun, several individuals were beaten or stabbed with at least eight requiring a visit to the hospital. It was reported that such levels of violence had only been present in 1950–1951. However, no data were provided to compare the time period changes. All of the high schools reportedly had the presence of a gang. Throughout the 1900s to 1950s, the public schools were segregated, and it was unclear from any data I could obtain what changes may have been occurring in each school.

Politically, El Paso accomplished one of its greatest feats in the election of Raymond Telles as mayor in 1957, the first Mexican American mayor of El Paso, and he served as mayor until 1961. Jaime Torres, a neighbor and friend who supported Telles’s political campaign, emphasized how Mexican Americans were the numerical majority, yet they had no representation in the local or regional government.109 According to historian Mario T. García, between 1900 and 1950 no Mexican American had been elected as mayor or as a member of the city council.110 Raymond Telles was born in South El Paso in 1915. He had served in the military and worked as a county clerk before launching a peoples’ campaign designed to gather Mexican American and Anglo votes, because votes from both racial and ethnic groups were needed to secure a victory. After his election, he increased the number of Mexican Americans attaining city jobs. García described Telles’s political strategy as the “politics of status,” which was not geared toward combating the root causes of Mexican-American underdevelopment but was more reformist in that it was focused on ensuring treatment of his ethnic group as full-fledged U.S. citizens. In assessing Telles’s role as the first Mexican American mayor, García stated, “Conservative in personal and social outlook, Telles in retrospect was a moderate reformer but one liberal for his own historical period.”111

Despite such a political accomplishment, the conditions in the community repeated previous historical patterns. The El Paso Police Chief ordered a crackdown on youth gangs after two Southside families were assaulted.112 The families planned to move out of the neighborhood, and residents reported living in fear. Officials believed the gang responsible included twenty members of the 7-X gang, which had been in the area for fifteen or twenty years.113 The city enacted a 10:00 P.M. curfew. Less than a month later, the Lucky 13s were believed to be involved in the beating and kicking of a 35-year-old man after he refused to give them a nickel.114 Similar to previous efforts, Mayor Telles appealed to parents to increase their level of surveillance on their children. Shortly after, the community mourned the death of a 19-year-old man who was fatally stabbed at the Our Lady’s Youth Center.115 The young man was a 4-F and was killed by a Little 9er. Father Rahm began having the youth hold a night court where they could settle their differences one on one.116 Mayor Telles thanked Father Rahm for his increased efforts to reduce violence. A city council member stated that new laws were needed to curb gangs and encouraged support for a law that would try youth who were 17 years of age as adults instead of juveniles because they could only be held until the age of 21 at the State Reformatory.117 The police were giving close crew cuts for “sanitary reasons” to youth detained in the city jail, which they hoped would serve as a deterrent for resuming gang activities. Despite increased public punishment, a 14-year-old boy was shot in the back with a .22 caliber rifle and died, reportedly due to gang warfare between the X-14s and the Cypress Kids.118 Residents stated that a member of the Scorpions had been knifed by an X-14 member, and the Cypress Kids went to avenge that attack by firing zip guns at rival members. During the same day, a 17-year-old was beaten to death with a steel bar.119 A Captain of El Paso County’s Detention Home stated that a year before there had been fifty-two gangs. The problem of gangs was described as increasing since 1951, brought down in 1953 due to police efforts, but it re-emerged in full force in 1957 with three youths dying from stab wounds and the comeback of members of the 7-X gang.

By the end of the 1950s, gangs were reported to have gone underground.120 The areas that were once hotbeds for gang activity had since gone quiet. There were no more reports of stealing hubcaps, crashing parties, drinking, arrests for vagrancy, drunkenness, traffic violations, burglary, theft, or possession of dangerous weapons such as knives or zip guns. The churches and schools were given credit for providing alternatives to gangs and violence through athletic recreational programs. A newspaper article written twenty years later reported that if you were to walk in the Southside during the 1950s you risked getting beat up.121 It was described as a time when the 7-X gang was on a crime spree and in open warfare with its rivals. The police department and city hall responded with “an all-out attack,” and a grand jury in 1951 investigated the problem. Bill Rodriguez’s oral history captures many of these themes. 122 Mr. Rodriguez, who was born 1936 to a Mexican father and an Anglo mother and eventually became the chief of police in El Paso, stated that in the mid-1950s he did not care for the police. At that time the police were physically aggressive with the Mexicans and the gangs, yet no one ever filed a complaint because it wasn’t considered macho. Once he became a police officer, he began to realize that, to advance in the police department, you had to be selected by the Anglo leadership, and that despite doing well on tests he continued to be overlooked. In response he went to college and earned a degree. He then went on to become a police sergeant and worked in community relations to help improve the police image among minority groups. By 1977 he was Chief of Police and served in this role until 1986. He continued working in law enforcement and various community positions for the city.123

Gangs of the 1960s–1970s

Compared to the 1950s, the 1960s was a quiet period of gang activity despite the departure of Father Rahm, who was sent to continue his religious efforts in Brazil in 1964.124 The decade began with an act of violence that made it appear gang activity may re-emerge. A 15-year-old boy was beaten and stabbed to death in South El Paso.125 He had previously been in a fight with members of the Lucky 14s, but several of his friends reported they did not believe the recent killing was from members of the Lucky 14s or the 7-Xs. Contrary to persistent negative media coverage of gangs, the El Paso Times wrote a four-part series devoted to the Charms and how several of its members had gone on to become heroes in the marines and athletics and it all began through youth athletic programming.126 The Charms was formed in 1956 by members of the 4-Fs, Lucky 13s, and Little 9s who were 14 years old and wanted to have fun. At the time, gang problems and rivalries were high and almost led to the closing of Bowie High School.127 Fred Morales, born in 1954 and raised in South El Paso, reported in a 1975 interview that gangs were very active during his years in grammar school and junior high.128 He thought the pachuco influence, machismo, and being el más chingón influenced youth to fight among each other and with Juárez gangs across the river. He mentioned several gangs, including the 7–11s, Eagles, Trampas, Alley Cats, Crusaders, Cougars, Jokers, Lucky Charms, and Shamrocks.

William E. Wood, who provided an oral history in 1994, stated he was a former government real estate appraiser during the Chamizal settlement. He reported that South El Paso had a lot of gangs, but in the early 1960s it was safe to walk the streets and the residents were hard working.129 A 1962 city ordinance outlawed discrimination in El Paso two years prior to the Civil Rights Act of 1964.130 In 1963, the Chamizal dispute was settled between United States and Mexico, and the agreement provided an additional 193 acres of land to the United States. Bowie High school was later relocated to this area, and more residents were relocated to the Tays Housing Projects.131 Residents were displaced by Southside housing projects and brought to new places.132 According to the Population Reference Bureau, the fourth wave of immigration occurred from 1965 to the present.133 One law scholar argued that the Immigration Act of 1965 was historic in its elimination of discriminatory national origin quotas. However, despite massive reforms compared to the previous waves, naturalization laws still imposed tighter entry requirements and increased enforcement.134 By 1965, the country shifted its policy from national origin to people who had relatives in the United States. The Civil Rights Movement argued on behalf of removing racial and ethnic discrimination in immigration law. The United States allowed access to previously excluded or underrepresented groups from Asia and Latin America.

Although gang activity dissipated in the 1960s, the root causes for gang formation were never resolved. A probation officer interviewed in a 1976 news article stated that he had been part of gang in the 1960s.135 At that time, a gang member had been killed and several of the gangs decided things were getting out of control, so they formed a Mexican American Youth Association (MAYA) to fight the system, but it failed to sustain leadership. According to the probation officer, many in the barrio were now junkies getting high, from spray paint to heroin. In 1971, several researchers from the University of Colorado’s Mexican-American Studies Program published a report titled “South El Paso: El Segundo Barrio.”136 In this report, the authors provided a historical overview of the neighborhood and current conditions by providing census data along with poetry and pictures. One of the poets who contributed to this work, Abelardo Delgado, described how South El Paso gave its residents a strong foundation educationally, recreationally, spiritually, and at home, yet it also served as a geographic prison. Paisano Drive, also called the Tortilla Curtain, was the main street separating Chihuahuita and Segundo Barrio from the rest of the El Paso. The report went on to describe the population, manufacturing jobs, and Anglo domination that persisted in the city of El Paso. Close examination was given to the Chihuahuita neighborhood, and census tracts 18, 19, 20 in particular (See Figure 4). The authors looked optimistically to the El Paso Boy’s Club and the opening of the Marcos B. Armijo Community Center in 1968. They criticized the city for failing to act on numerous reports of the need to “clean up” South El Paso since 1901.

The Marcos B. Armijo Community Center was a central place of activity for a sports club known as the Thunderbirds. Due to the location of the Center, the facility encountered challenges similar to those experienced by Father Rahm at the Our Lady’s Youth Center. In early April 1972, a conflict emerged between the Thunderbirds and group of individuals called the Tecatos, of whom most were described as heroin addicts and former convicts from the state penitentiary. Several Thunderbirds allegedly told Tecato members to inject their heroin somewhere else and that they could no longer use the handball court.137 After some time, the dispute increased to the point where several Tecatos drove up in a vehicle and fired upon Arturo Corrales, the leader of the Thunderbirds, killing him and wounding four others. Arturo Corrales was a Vietnam veteran who had previously attended Bowie High School.138 Members of the Thunderbirds reiterated to the news media how they were a sports organization in South El Paso and had been active for the past two years.139 The Thunderbirds had formed with the purpose to help the poor and keep kids out of trouble. They sponsored picnics for fatherless children and provided help to needy families. They worked to keep the area clean and keep trouble out of the neighborhood. The police said the “T-Birds” were a gang, and the El Paso Times ran a headline “Clubs or Gangs” with a news story acknowledging the difference between the groups of the time and the gangs existing fifteen years before, such as 7-X, Little 9s, and 7–11, but nonetheless concluded that the “T-Birds” were a gang.140 An El Paso policeman concurred that the evidence suggested the Tecatos were using drugs in the back of the Armijo Center, but the facility or the police should have been notified rather than the “T-Birds” assuming responsibility.141 These news articles also laid out the description of where each group existed (See Figure 5).142

By 1976, gang issues and juvenile delinquency continued to be a source of concern. The police department expanded its force by twenty men to help with case overloads, and they created a new youth-service division.143 Officials also became concerned with a young man given the nickname “El Raton” or “The Rat” because he snuck back and forth across the border committing property crimes and harassing elderly residents with his gang.144 One of the housing projects in Segundo Barrio, the Ruben Salazar housing complex, was described as being controlled by four gangs: Flaming Angels, Fonzies, La Sana, and Chicanos In Action (CIA).145 Residents stated that the gangs didn’t bother anyone if they were left alone. However, in September an 18-year-old man who lived in the projects was shot to death while talking with friends when a car of several individuals drove by and fired shots at him.146 The Flaming Angels sent flowers to his grave. The City of El Paso created a diversion unit.147 In September 1976, 583 juveniles received a referral, of whom 216 (37 percent) were Anglo, 336 (58 percent) were Mexican American, thirty (5 percent) were black, and one (less than 1 percent) was Asian. The newspaper reported that various gangs existed in the city, including Chicanos in Action, Blue Stars, Los Demonios, Flaming Angels, and Southside.148 Much of the gang activity was described as resulting from inadequate schools, a lack of jobs, and illegal “aliens.”

The following month, a 16-year-old boy who lived in the Ruben Salazar project was killed and was allegedly a member of a gang from San Antonio, Texas.149 The police said that the housing complex included the Thunderbirds gang, whereas the Metizos [sic] and La Sana were Central El Paso gangs. Another gang known as the Lords was present on the east side of El Paso. As the year continued, several South El Paso gangs continued shooting at each other despite the creation of a youth assistance program the previous year.150 Nevertheless, most agencies were not focused on youth gangs. Due to the repeated killings, residents in the Salazar housing projects asked for more security.151 Reportedly, several youths who were causing problems at Bowie and Douglas Elementary were from one of the housing projects. Two youth were arrested for the murder of a 23-year-old man who was shot off his motorcycle in South El Paso.152 The newspaper stated that there had been at least four killings since 1972 in feuds between gangs in South El Paso, but gathering information was difficult because gang members did not talk with authorities. Some residents blamed the police, whereas the police blamed parents. There was an overall distrust of Anglos. The Executive Director of the El Paso Boys Club, William H. Brown, called the organizations groups instead of gangs because the members didn’t have jobs and started as clubs or social groups.

Pete Jurado wrote his master’s thesis on a gang he gave the pseudonym the Chicano Aggregation (CA, which appears to be Chicanos In Action [CIA]) by covertly interviewing some of their members through his history of growing up in the neighborhood and working at the El Paso Job Corp Center.153 The gang existed in the Second Ward, which continued to have the highest concentration of Chicanos, deteriorated housing, and poverty. The members were between the ages of 14 to 33 years of age, and they all grew up near Our Lady’s Youth Center. Jurado described the conflict between the Saints (a pseudonym for the Thunderbirds) and the Tecatos. He stated that the Saints began around 1964 when a youth worker from Our Lady’s Youth Center organized the youth into a club for recreational and social activities, and they rarely were involved in delinquency. After 1969, several members had returned home from Vietnam and they began to re-establish old friendships, but they had become more interested in using marijuana or alcohol. They continued to hang out at the Our Lady’s Youth Center. Some members got married, whereas others continued to participate in athletic tournaments. In 1971, they began to get harassed more by the police and were having problems with the law and with the most powerful gang in the Second Ward, the Los Machos. After the shooting of Marales (pseudonym for Corrales), Jurado reported that the Saints didn’t hang around the Our Lady’s Youth Center for a period of time, and in their place emerged a group of youth named CA. They even challenged members of the newer Los Machos, now called Latin Lords (the pseudonym appears to be the Noble Lords), to a fight. Several Latin Lords were stabbed, and the CA became the toughest gang in the Second Ward. They continued to battle the Latin Lords and Tecatos, even killing one in 1975 at the Tays housing project. Jurado stated that the CA sold marijuana to make money. At the time, several members were in jail for this activity, and the gang had participated in at least two murders. Over time they stopped fighting with many other groups because at the time only two others existed (the Santana Revivals and the Alley Cats). Members of the CA received respect and were not bothered.

El Paso has a long history of gangs. The earliest accounts of these organizations range from 1915 to 1919. However, most this activity seems to be in the form of a wider style of cultural resistance to colonization in the form of pachuquismo. Mexicans were largely segregated at the time and were concentrated in the poorest housing conditions of the city in South El Paso. The Ku Klux Klan, which emerged among Anglos in the early 1920s, did not influence the area for long, but the overall sentiment of anti-Mexican and anti-Catholic sentiments had persisted since colonization. As these communities continued to be neglected, the 1940s brought neighborhood groups into conflict with one another. By the 1950s it became dangerous to walk into other territories. Father Rahm, in conjunction with the churches and community centers, stepped in to help gangs evolve into athletic clubs, and the violence decreased. The Chicano Movement helped displace some gang activity in the late 1960s, but the lack of sustained leadership did not allow the city’s activism to reach levels such as that seen in Denver, Colorado, or in Crystal City and San Antonio, Texas.154 The 1970s reflected these shifts as the groups focused on giving back to the community, but members of these organizations faced addiction and other issues after Vietnam as well as conflicts with individuals who had been incarcerated or addicted to heroin. It is this context that shaped the conditions prior to my arrival in the border region.