2. Feeling at Home

The White House steward, in exercising his prerogative of selecting candidates for office in the President’s household, enjoys a political patronage somewhat less than a Member of Congress, but still considerable. He also administers extensive commercial patronage. He purchases all of the supplies for the President’s table, and replenishes all household stores, such as table and bed linen, cooking utensils and crockery.

FLORA MCDONALD THOMPSON, “Housekeeping in the White House,” Junior Munsey, 1901

For thousands of years, stewards have served as the ultimate arbiter of good taste. In the Christian tradition, Jesus Christ performed his first miracle by turning water into wine at a wedding at Cana in Galilee. After the miracle was performed, the wedding’s steward (translated as the “master of the feast”) tasted the miraculous wine and immediately asked, “Why are you putting out the good stuff at the end of the wedding?”1 Presidential stewards have long accomplished roles as both tastemaker and miracle worker, usually under difficult circumstances. Though the proper title and responsibilities of the steward position have shifted over time, presidents have frequently called upon African Americans to oversee the Executive Mansion’s domestic operations, which include the culinary department. This chapter focuses on the White House experiences of six representative presidential stewards: Samuel Fraunces, William T. Crump, Henry Pinckney, Alonzo Fields, Stephen Rochon, and Angella Reid.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a “steward” was generally defined as “an official who controls the domestic affairs of a household, supervising the service of his master’s table, directing the domestics, and regulating household expenditure.”2 Accordingly, presidential stewards have performed the same duties for the presidential household: hiring and supervising all of the residence employees, administering all public and private dining, and ultimately being responsible for purchasing and safeguarding all White House property. Stewards answered solely to the First Family. Presidents have looked for a handful of key attributes in their stewards: trustworthiness, a demonstrated ability to do the job well (usually based on prior servitude in private life to the individual who became president), and African ancestry.

An overwhelming number of the African Americans who have held the presidential steward position have been biracial men, and this fact fed into a persistent stereotype from antebellum America: that enslaved biracial people (usually African and European) worked primarily as servants for the plantation master’s family in the “big house” while the darker-skinned enslaved African Americans labored in the plantation’s fields. In addition, it is believed that the legacy of this purposeful separation and differing status based on skin color has been a major stumbling block to collective black progress to this day. Yet slavery scholar Eugene D. Genovese, among others, has argued that this idea of a sharp color-based division of plantation labor is more myth than reality: “As often as not, southern slaveholders … enjoyed being served by blacks—the blacker the better—as well as by light-skinned Negroes. Even during the colonial period, whites did not show any great partiality to mulattoes, except when they were blood relatives.”3

Genovese’s conclusion became the conventional wisdom in scholarly circles, but Howard Bodenhorn, an economic historian at Clemson University, has recently called for a reassessment: “Eugene Genovese downplayed or dismissed mixed race preferences, but contemporary observations and modern statistical analysis point toward modestly favored treatment [for mixed race slaves]. Planters preferred mixed-race men and women as house servants, and gave them more skill training. Mixed-race slaves were more likely than blacks to receive some education, to eat from the Big House’s kitchen, to be better clothed and shod, and have greater freedom of movement on and off the plantation.”4 With this advantage in skills and training, biracial men were well positioned to get domestic household jobs or to start their own businesses (caterers, hoteliers, and restaurateurs). With this historical context, then, it is not surprising that our first president, a slave owner, put a biracial man—one who had run several successful businesses and one whom he knew very well—in charge of his household affairs.

President George Washington, it turns out, set a high standard for all presidential stewards who followed when he chose Samuel Fraunces to be the first. Before delving into Fraunces’s story, though, we must address a simmering-for-centuries controversy over his race. Some historians have strongly argued that Fraunces was white. In his painted portrait he looks white, and while this is not dispositive of African heritage, the image raises doubts. We know that Fraunces hailed from the West Indies, probably from Jamaica or Saint Domingue (present-day Haiti), but again, that fact in and of itself is not determinative of his race. Alexander Hamilton, a well-known Caucasian, was from the same place. Yet there are other qualities about Fraunces that would have been highly unusual for someone of African heritage—who was not passing for white—to possess in eighteenth-century New York City. First, Fraunces owned white indentured servants, and when they escaped he advertised rewards for their recapture in local newspapers.5 Additionally, he was listed as “white” in the 1790 federal census, he was a member of the Freemason secret society, he was a registered voter, and he attended Trinity Church in New York City.6

The most compelling positive case for his African heritage is that his contemporaries nicknamed him “Black Sam.” In those days, one would be called “black” for one of two reasons: having a villainous disposition or having a dark-complexioned skin tone. The first attribute is highly unlikely, given that General Washington thought so highly of him and trusted him. In a letter to Fraunces, Washington wrote, “You have invariably through the most trying times maintained a constant friendship and attention to the cause of our country and its independence and freedom.”7

The second reason, a darker skin tone, hasn’t always led to the assumption that one had African ancestry; there are whites who have been described as having a “swarthy” complexion without any further speculation about their race. But that’s not the case with Fraunces, who has generated a great deal of curiosity and controversy about his racial background, mainly due to the dogged efforts of journalists and (primarily) amateur historians.8 Supposedly, a birth certificate existed indicating that Fraunces had a white father and an African mother.9 Other “reputable class publications” and contemporaneous media accounts also describe Fraunces as a “mulatto,” the term of that time for biracial people.10 Fraunces biographer Charles Blockson adds, “While researching the story of his life, it was discovered that Fraunces’ racial identity was recorded as Negro, colored, Haitian Negro, Mulatto, ‘fastidious old Negro’ and swarthy.”11 Given the above, Fraunces arguably had African DNA—a conclusion embraced by some of his descendants—and I proceed on that assumption.12

Born in 1722, Fraunces arrived in New York City sometime in the early to mid-1750s, probably as a stowaway on a ship from the West Indies. He had an entrepreneurial spirit and opened his first business selling pickles and preserves. Thanks to his business success, he established his reputation as a dandy, often wearing a heavy watch chain and an elaborate wig. In 1762 he purchased the DeLancey Mansion for £2,000 and renamed it Queen Charlotte’s Head Tavern, which became Queen’s Tavern and then ultimately Fraunces Tavern. A replica of the original building currently stands at its original location of 54 Pearl Street (intersecting Broad Street) in the Wall Street district of New York City.13 Food-and-drink-loving people who were increasingly disenchanted with the British government gravitated to Fraunces Tavern. The British saw the tavern as a dangerous gathering place, and on 23 August 1775 the British warship Asia, patrolling in New York Harbor, shelled the tavern, hoping to kill a group of the revolutionaries in one fell swoop.14 That attempt was unsuccessful, and despite the physical damage to the building, the rebellion, Fraunces, and the tavern soldiered on.

General Washington began frequenting Fraunces Tavern in the 1770s and almost lost his life in what some call the “Poisoned Pea Plot of 1776.” One day Washington dined at the tavern, and Fraunces, knowing what the general liked, prepared a meal that included Washington’s favorite—green peas. Fraunces’s daughter Phoebe, as she had done countless times before, helped cook the meal. Enter Thomas Hickey, who was part of General Washington’s personal security detail but not really on “Team Washington.” Hickey was loyal to the British Empire and increasingly perceived the general as a growing threat to the crown. Hickey concluded that Washington should be assassinated, an event that would certainly have pleased King George III, and he waited for an opportune time to act.

Hickey first sought access to the general via the kitchen at the tavern, and he thought his best chance at that was to win Phoebe’s heart. Hickey started hanging around the kitchen, sweet-talking Phoebe in order to seduce her and gain her trust. When the opportunity presented itself, he distracted Phoebe long enough to add some “special seasoning” to General Washington’s peas. Phoebe suspected that something was up and alerted her father. There was only one problem—the plate had already been sent out to the general’s table. The moment he got word, Fraunces sprang into action, ran to Washington’s table, grabbed the plate of food before the general could take a bite, and threw it out of a window. At that precise moment, a chicken walked by the open window, spotted the providential peas, and started pecking at them. Within moments, the chicken died. Thanks to this instance of animal testing, everyone knew what Fraunces had already surmised: the peas had been poisoned with arsenic, a naturally occurring mineral that is deadly when ingested. Hickey was arrested for treason, jailed, court-martialed, and publicly hanged on 28 June 1776 before a crowd of 20,000 people in a New York public square near the present-day location of the Old Bowery.15 We might call this the first act of culinary homeland security in our great nation.

It’s a fantastic story but probably untrue for several reasons. Fraunces had children, but none of them were named Phoebe, though that could have been a family nickname. Second, Hickey was arrested and hanged, but his crime was counterfeiting (he falsified papers that would have allowed assassins to be in close proximity to General Washington), not attempted murder. Third, it’s not entirely clear that Fraunces was operating the tavern in 1776. Things were getting hectic for revolutionaries, and as British ground troops occupied the city, he escaped from New York to Elizabeth, New Jersey, in 1775 and turned the business over to someone else to manage in his absence. While in New Jersey, he was captured by British forces. Fortunately for Fraunces, his culinary reputation earned him a “get out of jail free” card: instead of imprisoning him, the British general overseeing military operations in the area made the curious and potentially dangerous decision to install Fraunces (an enemy of the British crown) as his personal cook.16 Regardless, Fraunces earned and retained enough of a hero status—through this and other exploits—to later successfully lobby Congress to compensate him $2,000 for his patriotic services to the country.17

Fraunces returned to operate the tavern by 1783, and General Washington continued to patronize the business. The tavern held such a special place in Washington’s heart that he gave his farewell to his Continental army troops in the tavern’s upper room on 4 December 1783. This event caused the tavern to be inaccurately nicknamed “Washington’s Headquarters.”18 General Washington had hoped that it would be a true farewell and that he could quietly retire to his plantation at Mount Vernon, Virginia. Yet the public clamoring for his return was so great that Washington was forced to come out of retirement. He reluctantly agreed to be the first president of the United States.

President Washington was keenly aware that everything he did would be heavily scrutinized and would set precedent for future presidents. How he dined and entertained was no exception. President Washington did not want to act, or even appear to act, as a monarch. Yet, he wanted the best for his table. In May 1789 he hired Fraunces to serve as the steward for the first Executive Mansion, which was the Osgood Residence at 1-3 Cherry Street (intersecting Pearl Street) in New York City.19

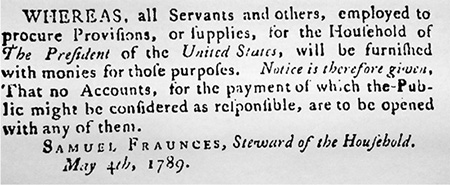

Fraunces newspaper advertisement. Connecticut Courant and Weekly Intelligencer, 11 May 1789.

Once installed as steward, Fraunces quickly let everyone know that he was “in charge.” He anticipated that merchants would try to capitalize on any business relationships they had with President Washington and therefore published a bill of notice in local newspapers that left no doubt that all household business matters went through him.20 Fraunces served a very short stint in New York City before the nation’s capital was moved to Philadelphia in 1790. There, the new Executive Mansion was the Robert Morris House at 190 High Street, one block from Independence Hall. The culinary team that Fraunces put together, subject to President Washington’s approval, included a mix of free whites (hired on the open labor market) and enslaved blacks whom Washington relocated from Mount Vernon. With the team in place, Fraunces began the difficult task of running the presidential household.

Fraunces set a fantastic table for President Washington. In a glowing letter to Tobias Lear, Washington wrote about one meal, “Fraunces, besides being an excellent cook, knowing how to provide genteel dinners, and giving aid in dressing them, prepared the dessert and made the cake.”21 Lear must have agreed. A Washington biographer wrote, “Tobias Lear stared agog at the heaps of lobster, oysters, and other dishes, saying Fraunces, ‘tossed up such a number of fine dishes that we are distracted in our choice when we sit down to table and obliged to hold a long consultation upon the subject, before we can determine what to attack.”22 Fortunately, one of the president’s dinner guests, U.S. senator William Maclay from Pennsylvania, wrote in detail about one of the “genteel dinners” that Fraunces supervised:

In his diary, Maclay described a dinner on August 27, 1789 in which George and Martha Washington sat in the middle of the table, facing each other, while Tobias Lear and Robert Lewis sat on either end. John Adams, John Jay and George Clinton were among the assembled guests. Maclay described a table bursting with a rich assortment of dishes—roasted fish, boiled meat, bacon and poultry for the main course, followed by ice cream, jellies, pies, puddings and melons for dessert. Washington usually downed a pint of beer and two or three glasses of wine, and his demeanor grew livelier once he had consumed them.23

According to one presidential food historian, “At dinner parties [Fraunces] cut quite a figure in his silk knee breeches, white ruffled shirt, and carefully powdered black hair as he stood at the sideboard throughout the meal, watching to be sure the footmen attended all of the guests properly.”24

Though President Washington relished Fraunces’s meals, he was troubled by what he saw as his steward’s reckless spending. This dynamic set up a repeated back-and-forth that strained their relationship. The most celebrated example of such is a bad fish tale that President Washington’s stepgrandson, George Washington Parke Custis, shared in his memoirs:

President Washington was remarkably fond of fish…. It happened that a single shad was caught in the Delaware in February, and brought to the Philadelphia market for sale. Fraunces pounced upon it with the speed of an osprey, regardless of price, but charmed that he had secured a delicacy that, above all others, he knew would be agreeable to the plate of his chief. When the fish was served, Washington suspected a departure from his orders touching the provision to be made for his table, and said to Fraunces, who stood at his post at the sideboard, “What fish is this?”—“A shad, a very fine shad,” was the reply; “I knew your excellency was particularly fond of this fish, and was so fortunate as to procure this one in market—a solitary one, and the first of the season”—“The price, sir; the price!” continued Washington, in a stern commanding tone; “the price, sir?”—“Three—three—three dollars,” stammered out the conscience-stricken steward. “Take it away,” thundered the chief; “take it away, sir; it shall never be said that my table set such an example of luxury and extravagance.” Poor Fraunces tremblingly obeyed, and the first shad of the season was removed untouched, to be speedily devoured by the gourmands of the servants’ hall.25

I’m sure Fraunces went into that situation thinking that his accomplishment was “off the hook,” but he seriously jeopardized his continued status as Washington’s steward. Before this incident, President Washington had frequently lectured Fraunces about controlling costs. In addition to worrying about providing fodder to his political enemies, Washington had a very real concern about frivolous spending. In response, a chastised Fraunces promised to do better but reportedly said, “Well, he may discharge me if he will, but while he is the President and I am his steward his establishment shall be supplied with the best the whole country can afford.”26 President Washington eventually had enough and fired Fraunces in 1790. He experimented with another steward, but that didn’t last long. Washington rehired Fraunces six months later.27

Thanks again to Custis, we have some glimpses of Fraunces’s culinary duties for the Washington household. The president typically ate a light breakfast of corn cakes or buckwheat cakes, but all other meals were top-notch. Every Tuesday afternoon, Washington hosted a social hour called a “levee” where invited guests could interact with him (I am purposefully avoiding the word “socialize” because there appeared to be very little talking at these events). When he hosted members of Congress for dinner, the meals started promptly at 4 P.M., and as noted earlier, punctuality was a must. With Fraunces’s help, the Washingtons earned a solid reputation for their presidential entertaining, and guests looked forward to being at their table. Fraunces managed to stay in President Washington’s good graces until 1794, when he left of his own volition to open a tavern in Philadelphia that he ran with his wife, Elizabeth.28 Fraunces died in 1795 and is buried in an unmarked grave in the cemetery at St. Peter’s Episcopal Church in Philadelphia.29 In remembrance of Fraunces’s life, a tribute obelisk has been placed at the cemetery’s entrance.

Though the Robert Morris House had long been demolished, the site of this early presidential household made headlines in 2002. The National Park Service, during a planned expansion of the Liberty Bell Center, unearthed the remains of the house’s slave quarters. Inexplicably, the National Park Service initially planned to ignore the discovery, but a band of local citizens created enough of a stir to persuade the agency to honor the site’s historical significance.30 Today, visitors to the Liberty Bell complex will see an open-air re-creation of the Robert Morris House with just the building’s frame and walls in their original locations. Through a self-guided tour, visitors may go from room to room and watch an interactive video that explains what daily life was like in that specific part of the house, particularly from the viewpoint of the enslaved workforce.

From President Washington’s time until the Civil War, white U.S. citizens and white foreign nationals were regularly employed as presidential stewards. Yet there were some notable African American exceptions: George DeBaptiste, a leading Detroit caterer, who served during the very brief administration of President William Henry Harrison; William Slade, a messenger in the Lincoln White House whom President Andrew Johnson elevated during his administration;31 and John A. Simms, who served for part of President Rutherford B. Hayes’s administration. These individuals avoided public attention, but one presidential steward loved the limelight: William T. Crump, who served as steward for President Hayes.

Crump was born circa 1840, and though relatively little is known about his early life, we know that he met Hayes during the Civil War when Crump served as Hayes’s Union army orderly. Crump must have made a good impression upon Hayes, which paved the way for his eventual hire as presidential steward. In that role, Crump earned a reputation for being a “faithful and efficient man.”32 For Crump, the steward’s duties were essentially the same as they were in Fraunces’s day: procure the food, supervise the domestic staff, get outside caterers, hire extra help for large events, and have the ultimate responsibility for all government property at the White House.33 Yet, a steward’s duties could vary from administration to administration based on the personality quirks of a particular president. For example, President Hayes directed Crump to shop at the local markets, in contrast to his immediate predecessor, President Ulysses S. Grant, who had his steward economize by getting food from the Army commissary at a marked discount. The difference in these approaches is that President Hayes probably didn’t care about cost because he was wealthy and paid for everything out of his own pocket, while President Grant was a man of limited means.34 Crump’s life as the White House steward was pretty routine, except for two events—one (allegedly) caused by a bottle of liquor and the other by an assassin’s bullet. The former involved a controversial state dinner given by the Hayeses where alcoholic drinks may or may not have been served. While that state dinner (discussed in chapter 6) got on the public’s nerves, the attempted assassination of Hayes’s successor, President James Garfield, truly put the nation on edge.

When Charles J. Guiteau shot President Garfield at the Baltimore & Potomac Depot in Washington, D.C., on 2 July 1881, he retraumatized a nation still healing from President Lincoln’s assassination. By all accounts, Garfield suffered immensely during his unsuccessful convalescence, and not only from the bullet wound. His doctors, equipped with nineteenth-century medical practices and devices, tried a variety of treatments that hastened his death rather than saved his life. Newspaper readers received daily progress reports on President Garfield’s condition, often directly from Crump, who was the only one who had access to the president besides Mrs. Garfield, General David Swain, Dr. Willard Bliss, Dr. S. E. Boynton, and Colonel A. F. Rockwell (a close friend).35

As a frequent source of news on Garfield’s condition, Crump inadvertently and informally became the White House’s first press secretary a half century before the position became official. Crump knew Garfield’s condition was terminal, but he chose to be upbeat. The Critic reported that “Mr. Crump has every confidence in the President’s recovery, and says he is willing to bet that he will be able to take a drive inside of a month. The speaker grew more enthusiastic as he [warmed] up to his subject, and said, ‘Wait till the President gets well, and then we’ll have a Fourth of July worth talking about.’”36 Crump’s reports boosted the nation’s hopes for the ailing president as well as its economy much more than the reports from Dr. Bliss.37

During President Garfield’s attempted convalescence, Crump tried to provide every comfort, and the nation saw the president’s appetite for food as the strongest indicator of his appetite for life. Folks were downright gleeful to hear that Garfield had graduated from drinking only water, beef broth, or chicken broth to eating a piece of toast that Crump drenched with the juice of a cooked steak followed by a small piece of the steak itself.38

The good news didn’t last long. Though there were flashes of improvement, President Garfield’s health continued to deteriorate. And in response to reports of the president’s poor appetite, an empathetic American public responded to the jarring turn of events with an outpouring of concern, grief, and booze. Much to the dismay of temperance advocates, the White House overflowed with alcohol. As one newspaper of the day reported, “During the first month following the wound of the assassin, when brandies, whiskies, champagnes, sherries, tokay, madeiras, gins, cordials, bitters and stimulants of every description, sent by kindly hands to the sick man, blocked the corridors, rooms and ante-chambers of the White House, Crump, like the skipper of a fast ship in a fair breeze, was always on deck chirpy and cheerful.”39 But the president could not enjoy the flood of libations. He could barely keep down anything but water in his weakened condition.

Crump rose to semicelebrity status, but the glow of his limelight faded after President Garfield died on 19 September 1881. He continued on as presidential steward to Garfield’s successor, President Chester A. Arthur, but Crump didn’t thrive under the new administration and resigned from his White House position in May 1882 for health reasons. After a White House farewell party, where he was presented with a gold-headed cane, Crump reportedly sailed to Liverpool, England, to visit friends.40 Yet he was back at the White House a couple of years later, working for President Arthur again.

President Arthur was generally regarded as a bon vivant and the most accomplished gourmet to entertain in the White House since Jefferson.41 In a newspaper interview, Crump complained about the long hours he and the staff worked due to President Arthur’s late-night entertaining. The interviewer asked him, “Is the position of steward a desirable one?” Crump responded, “Not very at this time. The work is very hard. In addition to the catering and seeing that the house is kept in order, the steward has to watch the relic-hunters.”42 The last part of that sentence referred to guests at White House functions who were compelled to steal—I mean, “take home a souvenir”—from their White House experience.

By 1886, Crump had left the White House to operate a hotel in suburban Washington that was “filled with ghastly mementoes of Garfield’s untimely taking off. He has a part of the shirt which the martyred President wore when shot, the easy reclining chair to which he was transferred from the bed at Elberon [the place in New Jersey where President Garfield died], his ink stands, whisp-broom and many other relics.” He also kept a record of all who were guests at President Garfield’s table when they ate at the White House and a list of those who called on Mrs. Garfield. Included in this list was Charles J. Guiteau, the assassin.43 Evidently the public agreed that the hotel was in poor taste. It was lightly patronized with their business, and it soon closed. Crump fell on hard times and took a page from the playbook of previous presidential steward Samuel Fraunces—he appealed directly to Congress for money. Though he had been paid $1,800 a year in salary as a presidential steward, he asked for an additional $3,000 for rendering additional services under extraordinary circumstances, since caring for President Garfield had been difficult and had adversely affected his own health. His arduous duties had included lifting the ailing president up several times a day for bathing and other care. The controversial appeal led to a prolonged and raucous debate in the halls of Congress and in newspaper editorial pages across the country. In 1888, the U.S. Senate finally approved legislation to pay Crump, and he got $5,000 instead of the $3,000 he initially requested. Crump owed his big payday to the best lobbying effort that he could have had at the time—a letter of support from President Garfield’s widow.44

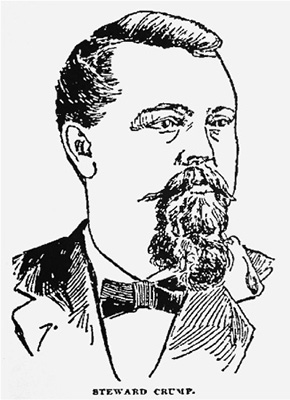

William T. Crump, presidential steward. Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 December 1892.

Crump later figuratively threw his weight around in public as a celebrity pitchman who played on his White House tenure. Crump had entered the White House weighing a spry 225 pounds, but by the time he retired he had gained another 100 pounds. For the sake of his health, he had to do something about his weight. Since losing weight was slow going, Crump adopted a strategy of shifting how his stomach was supported: he got a girdle made for men. Who knows why Crump made the short list, but the marketing people promoting “Dr. Edison’s Obesity and Supporting Band” chose Crump as its spokesperson. Dr. Edison’s marketing team went big with their advertising campaign. Not only did they communicate Crump’s personal experience with excessive weight, but they also highlighted his past presidential staff experience as well as his future prospects. The pun-heavy top line blared, “M’Kinley’s Possible Steward REDUCED.”45 Crump, true to form, showed his confidence in future White House employment by expressing in the ad, “[I]f Major McKinley is elected President, [Crump] will again become a steward in the White House.”46 No one knows if William McKinley ever read this advertisement, but whatever slim opportunity Crump had to regain his old position, it never worked out. McKinley chose another African American man, William Sinclair, to serve as his steward. Crump faded into obscurity and died in 1909. Sinclair resigned when Theodore Roosevelt became president, and that led to the hiring of Henry Pinckney, the last of the great African American White House stewards.

Like so many before him, Pinckney began his path to the White House when he became the personal servant of a future president. Pinckney, born in 1857, grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, and was eventually employed as a messenger for several New York governors, including Theodore Roosevelt.47 Unlike many of his predecessors, Pinckney was not a biracial man; rather, he was described as “an undersized negro, black as night.”48 Though his skin color differed, Pinckney shared an important trait with his biracial predecessors—he was extremely trustworthy. Pinckney left his state government job to work for Governor Roosevelt at his private residence in Oyster Bay, New York, before turning to federal employment when Roosevelt became vice president and then president of the United States.49 Pinckney became the presidential steward in October 1901. He and his wife were certainly appreciative, for later that same month they named their newborn son Theodore Roosevelt Pinckney.50

By Pinckney’s time, the White House steward’s power was formidable. The Evening Star reported, “The whole domestic distribution of the White House is under control of the steward. The President’s wife is little more than a distinguished figurehead.”51 In addition to the various butlers, clerks, maids, messengers, and police, Pinckney supervised “five negro women—a cook, assistant cook, scullion and two laundresses—[who] have long been carried on the White House pay roll at $1 a day each.”52 However, the racial makeup of the kitchen staff changed as more ethnic white European immigrant women were hired into the Roosevelt kitchen.53 Even with the changing racial dynamics, Pinckney was good at what he did, and outside observers lauded his professionalism. “He is very quiet and unassuming in manner, but thoroughly trustworthy,” the Hartford Courant related. “Every morning he goes to the markets, and the way in which he conducts these expeditions would do credit to a diplomatist.”54

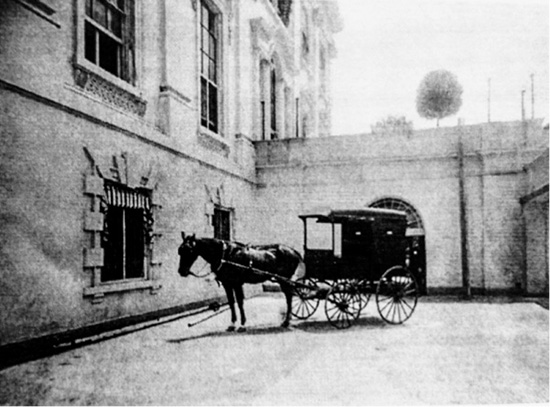

In terms of marketing, Pinckney continued a longtime practice (since Crump’s time) of procuring provisions under a low profile. One newspaper reported, “The majority of the purchases are even sent to the White House in an unlettered wagon. This wagon comes in at the south entrance and drives through the west colonnade to the kitchen door…. Any passer-by looking over the railing could see it, but he would never be able to guess from anything about its appearance what grocery house or market feed which it contains comes from.”55 One big difference between Pinckney and his predecessors was that every day he made a special delivery before picking up groceries. The Washington Times informed its readers that “Archibald Roosevelt goes to school every morning in the White House wagon, which is considered a good enough vehicle for the transportation of a President’s son. Every morning Archibald is loaded aboard the cart, bound for the educational establishment at which he is acquiring large chunks of learning. This wagon belongs, officially speaking, to the steward of the White House, and he is employed ordinarily for bringing provisions to the Executive Mansion.”56

After dropping off Archibald, Pinckney routinely purchased big pieces of meat at the market, which eventually resulted in the first of several press scrutiny headaches he would suffer—and help manage. It began with Pinckney consenting to what he thought would be a harmless Washington Post interview on President Roosevelt’s food habits. The White House immediately went into spin control mode when the following headline appeared: “White House Table Supplied with Best Market Affords, but Wholesomeness First Considered.”57 Much like his predecessor Fraunces, Pinckney wanted the best for the president’s table, but he made the mistake of boasting about it to the press. Pinckney had enthusiastically painted an epicurean image that smacked too much of elitism for a president who purported to be a “man of the people.” President Roosevelt asked the newspaper to print a correction story that extensively clarified that the First Family didn’t regularly consume “fancy dishes” and ate like other typical American families.58 With the follow-up article, President Roosevelt managed to get a “clean plate” with the public.

Another controversy, albeit a much smaller one, came during the holidays. For most people, Thanksgiving is the official kickoff to a holiday season that promises to be full of family, food, and fun. But for Pinckney, the holiday brought another headache that could not be solely blamed on tryptophan. Since the Grant administration, wealthy turkey ranchers vied to have their bird served as the official White House Thanksgiving turkey. Most years, that honor went to Horace Vose of Rhode Island.59 Trouble came when more than one turkey was delivered to the White House.60 Most times, Pinckney would choose among the turkeys, and Vose’s bird was usually preferred because of its high quality. However, the selection process became political as the wealthy donors who were left out were miffed that they were unable to publicize that the president preferred their turkey above all others. In order to keep the wealthy donors happy, Pinckney’s solution was to cook all of the turkeys they received, carve them up, and then mix up all of the meat before serving. This gave President Roosevelt something all presidents covet—plausible deniability. When asked by one of the donors, President Roosevelt could honestly say, “I ate your turkey.” Given his wise resolution of the potential conflict, I truly hope that to “pull a Pinckney” or “mix your turkeys” will enter our lexicon as an alternative to “split the baby.”

White House market wagon, circa 1909. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Things got easier for Pinckney by Christmastime when he oversaw the annual turkey distribution to White House employees—a perk that Roosevelt instituted during his first term. As reported in 1904,

[Pinckney] made a trip to the market early this morning and selected thirty-five of the fattest birds he could find. These he brought back to the White House in the big covered market wagon, and piled them in a tempting array on a table in the basement kitchen. As soon as the word was given out, shortly after 3 P.M., that the turkeys were ready to be distributed, there was a general rush in the direction of “Pinckneyville,” as some of the employes [sic] term the steward’s domain. It was first come, first served, and Pinckney was not charged with favoritism. The unmarried employes [sic] of the White House, who did not share in the distribution, watched the proceedings with envious eyes. “To the benedicts belong the spoils,” remarked Secretary [William] Loeb [Jr.] to one of the bachelor clerks who asked about his turkey. “You may get one next year if you continue to stand in the favor of a certain young woman out in the Northwest.”61

A few years later, the distribution increased to 125 turkeys, and Pinckney created an elaborate tagging and numbering system. The unmarried employees, however, were still left out.62 The turkey distribution scheme may have created an incentive to get married, but it’s unclear if anyone took that step.

It wasn’t until after his presidency that Roosevelt would again have egg on his face for White House food operations. In 1910, newspaper editors who were not fans of the former commander in chief salivated at the opportunity of a lifetime. Roosevelt, the very man who had crusaded for food protection laws, allegedly ate and approved of the tainted meat while in the White House. One newspaper gleefully reported,

At the White House dinners during the last Administration the meat was often so unwholesome that it was ready to fall to pieces, according to the testimony given to-day by Food Inspector Dodge of the District Health Department before the Moore special committee of the House investigating the food cost question. He said that while Mr. Roosevelt was President the steward at the Executive Mansion used to hang up his beef and keep it there until he could stick his finger into it in order to allow it to get “ripe.” When it was ready to fall to pieces, the food inspector declared, it was taken down and served, and not before. But the testimony continued with the statement that the practice of using unduly aged meat was well established in many wealthy homes and that dealers who catered to a fashionable trade had to keep old meat on hand because some of their customers would take no other.63

A seriously offended Pinckney quickly rebutted the allegations, using with some irony the same sentiment that had gotten him in hot water four years prior—the excellence of White House food. Decrying the article’s lies, Pinckney emphatically stated that all meat procured by the White House was fresh as ordered by the cook and that he never hanged such up in the White House. On top of that, he said no health inspector ever went to the White House during his tenure and shouldn’t be there, since it is a private residence. He concluded by restating that Inspector Dodge’s testimony was “a falsehood from beginning to end.”64

Pinckney went on to serve as steward in the William Howard Taft administration, but he died in April 1911, a little more than two years into the job, and along with him died the long reign of African American stewards. The not-so-wealthy Tafts, in a cost-saving move, eliminated the position of White House steward and put all domestic operations under the control of Elizabeth Jaffray, a white woman who served as the White House housekeeper. This was a significant change, because the White House’s food operations, which had functioned as a hybrid between how food service happens at a hotel and how it happens at a wealthy residence, made a full transition to mimicking that of a wealthy home: all cooking was done on site with no meals outsourced to caterers. The White House housekeeper position would reign supreme in the residence for the next three decades. The housekeeper had the same duties as the steward, minus the responsibility for White House property. That responsibility was charged to another White House employee, typically an African American. With the ascendancy of a powerful white housekeeper, it would be several decades until an African American again played an important role in presidential food operations. That person was Alonzo Fields.

Alonzo Fields was born in 1901 in the all-black community of Lyles, Indiana. He was the son of two entrepreneurs: his father ran a general store, and his mother operated a boardinghouse for railroad workers. His father was also musically inclined and directed a large and popular brass band that he had formed. Fields, who could play instruments and sing, loved music as well and planned a career in that field. His journey led him all the way to the New England Conservatory of Music in Boston, but he soon ran out of money. A friend offered to help Fields get a job as a butler for Dr. Samuel W. Stratton, who was president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Fields wasn’t keen for such a position, but he was persuaded that it was just a job and would help him observe how people of good breeding and connoisseurs of good taste like Stratton behaved. That, in turn, could be of use when he resumed his classical music career. So Fields agreed, and while in the Stratton household he soon met a lot of notable people who would eventually help him out in a pinch.65

Fields wrote in his memoirs about how various personal connections helped him get a job at the White House:

When I went to the White House through Mrs. Hoover’s [the First Lady] invitation, Dr. Stratton had died suddenly. I was at the time trying to follow a musical career as a concert singer. That was the height of the Depression. My wife lost her health. Mrs. Hoover had Lieutenant [Frederick] Butler call me and ask me what I was going to do. I said I didn’t know what I was going to do. So he said that Mrs. Hoover thinks that you ought to come down here [to the White House] for the winter. And I went down for the winter. And, of course, Ike Hoover [the chief usher] didn’t know of my coming whatsoever. This was all above him. You see, when I went on the job, of course, as I say, he was always very kind to me. But I think he interpreted the fact that Mrs. Hoover had invited me there. I didn’t give him any reason, and I wouldn’t give him any reason. But he was always very kind to me.66

Fields began his lengthy White House career in 1931. At six foot one and 240 pounds, he was a memorable figure in the Executive Residence. By some accounts, the first floor ceiling creaked as he walked on the second floor (this was an early warning sign of the sad state of the White House’s deteriorating physical condition), and dishes rattled when he entered and exited the pantry.67 When he was first hired, he was in charge of President Herbert Hoover’s “medicine ball breakfast” table—so called because Hoover would meet with his staff early in the morning and pass a medicine ball around for exercise while they discussed the day’s topics.68

Early in the Franklin Roosevelt administration, Fields rose in the ranks, though he apparently wasn’t angling for a promotion. In his memoir, Fields described how “accidental” his promotion was with this sequence of events, chiefly involving then chief usher Ike Hoover and a butler named Incarnation Rodriquez:

And when the Hoovers went out, he [Ike Hoover] and Lieutenant [Frederick] Butler got together, I’m sure, and a man by the name of Incarnation Rodriquez was in line to be the head man. Ike Hoover just came into the dining room and took it all over. Ike Hoover came into the dining room and said to call all of the butlers together. He said, “Rodriquez, you’re the second man here.” He said, “Yes.” He said, “Well, you’ll still be the second man.” And he pointed to me and he said, “Fields, you take charge.” That’s all the information that I got. And I took charge.69

Fields got his next promotion while the Trumans lived in the Blair House during the White House renovation that took place in the early 1950s: “I went to the Chief Butler during the Truman administration. Then, President Truman decided that I should be in complete charge, plan all of the menus, and so forth, and so I was the maître d’hôtel in the Truman administration.”70 With Fields’s new title and redistributed responsibilities, we see the White House transitioning from being run like a wealthy residence back to being run like a hotel.

Fields described his duties as the maître d’hôtel during the Truman administration in ways that were not far off from those of a nineteenth-century steward: “For more than twenty-one years I served the White House as butler, chief butler and maître d’hôtel…. I planned and directed all of the family, state, and social functions of four Presidents and kept the inventories of china, glassware, table linens, and silverware…. As the maître d’hôtel, I was further required to plan all the menus and direct the activities of the butlers and the kitchen.”71 Here, Fields is really describing what he did toward the end of his career, for while he worked in the Roosevelt administration, Henrietta Nesbitt supervised all culinary operations in her capacity as White House housekeeper. Fields took over after Mrs. Truman fired Nesbitt for refusing to let the First Lady take a stick of butter from the White House kitchen to a potluck luncheon hosted by one of her friends.72

Consciously or inadvertently, members of the First Family often put a lot of pressure on the culinary staff, who have to make sure that they get the food they like and that it meets any dietary restrictions they may have. Reflecting on the Trumans, Fields wrote,

Preparing menus for the Trumans was not too easy. Not that they were difficult to please or fussy, but Mrs. Truman was on a salt-free diet, the President required a low-calorie and high protein diet, and Mrs. Wallace [President Truman’s mother-in-law] needed all the calories that she could get. Miss Margaret was away most of the time, working at her career of singing and the stage. Only when she was home could we go overboard. The family meals were simple three-course affairs except for Sundays or when guests had been invited.73

Chief usher J. B. West added, “We even had to remove the water-softening system from the cold-water plumbing, because it contained sodium.”74

Fields’s next concern was making sure that there was enough food to go around, given budgetary restraints. This hasn’t been a problem for most First Families because few presidents have had large families living with them in the White House, and even fewer entertained extended family. One big exception was President Franklin and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. “The Roosevelt grandchildren and nurses added many problems to the duties of serving meals on trays,” Fields noted. “Finally a kitchen was built on the third floor which also served as a diet kitchen for the President. When all the grandchildren were present, meals could be prepared there and served in the sun parlor or hall.”75

The new kitchen meant the Roosevelts needed another cook, and that process took an interesting turn for the Fields family. Fields recalled,

My wife, Edna, was hired by Mrs. Nesbitt to cook for the grandchildren. I protested, for as I told her, my wife was not a cook. Nevertheless, she went to work and I must say she surprised me, for she certainly cooked much better for them than she had for me. My wife still tells me off about the time I told people at the White House that she couldn’t cook. I am not sure whether she has forgiven me, but she certainly hasn’t forgotten about it. She happened to cook a few meals there for the President when the grandchildren were there, so now I dare not go into the kitchen at home when a meal is being prepared.76

Fortunately, Fields lived to see another day.

As maître d’, Fields also knew the importance of building a sense of camaraderie with the White House staff. He often looked for opportunities to lighten things up around the workplace and to build a rapport with those he supervised. In his memoirs, he shared this story about how his joking put one of the black cooks on edge:

The Trumans moved into the White House in time for the President’s birthday, May 8, 1945, and Elizabeth Moore, who was then the head cook, baked a cake for the President. It was rather funny, for the kitchen had never baked a birthday cake in twelve years; for that matter, no hot rolls, doughnuts, coffee cake, or breads either. Sometimes they made popovers for breakfast. Otherwise a local bakery supplied all of the breads; hot rolls at the White House meant warmed-over bakery rolls. President Truman was so pleased with his birthday cake that after dinner he wanted to see the cook and personally thank her. But Elizabeth and her crew had cleared out as soon as the cake had been set up. Next morning I told her, with a long face, that the President had wanted to see her the night before about the cake she had baked. She said, “Oh, Fields! What happened? What was wrong with it?” “You baked it,” I said. “Don’t you know?” Then I pulled up a chair and said, “Girl, take this seat before you faint. The President was so pleased that he merely wanted to thank you personally.” She found it harder to believe that the President wanted to thank her than that something was wrong with the cake. So on his way to the office the next morning the President did stop by the kitchen and met the whole crew.77

Dispensing compliments about the food was not always left to Fields. White House history is full of anecdotes where presidents paused a moment to praise their cooks. Despite Moore’s reaction, President Truman was known to do so regularly. Such a small act meant the world to these cooks and made up for the long hours they spent in a frequently high-stress environment.

Fields was in a privileged position to observe some amazing scenes in the private White House, including experimentation and consumption of unusual foods. In the 1920s, Franklin Roosevelt spent time in Warm Springs, Georgia, to get treatment for his polio. While there, many of his meals were cooked by a woman named Daisy Bonner (who is further discussed in chapter 5). Bonner introduced FDR to a lot of southern delicacies, and he took a liking to one you might not expect—pigs’ feet! In no time, FDR was grubbing on pigs’ feet in a variety of ways and was eager to share this culinary delight with others—including “Very Important People.” One day, Fields was an eyewitness to President Roosevelt sharing his love of sweet and sour pigs’ feet with a favorite VIP:

It was this type of pigs’ feet that he requested to be served at a luncheon for just the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, and himself. Princess Martha of Norway, who lived at Pookshill, Maryland, during the war, had a cook who often prepared pigs’ feet in this style and she had brought the President this dish. He had a twinkle in his eye when he said, “Let’s have them for the luncheon tomorrow for the Prime Minister.” When the luncheon was served and the Prime Minister started to help himself, he inquired, “What is this?” He was told, “Sir, this is pigs’ feet.” He said, “Pigs’ feet? I never heard of them,” and then heartily helped himself. After tasting them he said, “Very good, but sort of slimy.” The President laughed and said, “Yes, they are a bit, but I am fond of them. Sometime we will have some of them fried.” Whereupon the Prime Minister replied, “No, thank you. I do not believe I would care for them fried.” Then they both had a hearty laugh.78

This may have been one of the top soul food moments in White House history. Still unconvinced as to President Roosevelt’s pigs’ feet habit? In 2011 I visited the “Little White House” site in Warm Springs, Georgia, and saw on display the shopping list written in advance of what would be FDR’s last week of life. It lists “4 hog’s feet.”

Once Fields retired in 1953, he passed the white gloves to Charles Ficklin, an African American who served as the maître d’hôtel until 1965, and then Charles’s brother John (profiled in chapter 6) assumed the position and served for several decades. During the Ficklins’ stint, the nature of the maître d’hôtel job changed when First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy created the position of White House executive chef in 1961. From that point on, the executive chef has handled most of the culinary duties and directly consulted with the First Lady. As we’ll also see in chapter 6, the maître d’ became the White House sommelier during John Ficklin’s tenure. Otherwise, the maître d’ position is essentially that of chief butler or headwaiter. Though a diminished role from the presidential stewards of yore, the maître d’hôtel job was still a very important one in White House food operations.

It would be decades before an African American once again held total responsibility for the operation of the Executive Residence, and that happened on 27 February 2007, when President George W. Bush tapped Rear Admiral Stephen W. Rochon, USCG (Ret.), to be the eighth White House chief usher in history. Admiral Rochon’s distinguished naval career began in the Coast Guard in 1970. According to the White House press release about his hiring, “With 36 years in public service, Admiral Rochon has an extensive background in personnel management, strategic planning, and effective interagency coordination.”79 Rochon caught President Bush’s attention because he was the Coast Guard’s head person in charge of the Port of New Orleans during a devastating oil spill in 2000 and during the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005.80 Rochon’s ability to handle crisis situations involving a lot of moving parts made him a great candidate for the usher’s job. Who better to run a tight ship like the White House than a former admiral? Again, with the executive chef in the mix, Rochon had little to do with culinary operations other than hiring kitchen staff, but he had to manage what many describe as “an invisible army.”81 Although Rochon was the first African American to serve as a chief usher in a technical sense, the duties that came with the position put Rochon squarely within the legacy left by African American stewards a century earlier.

Rochon, with a strong appreciation for history, was acutely aware of the honor bestowed upon him. In 1996, as a coast commander stationed in Baltimore, he hosted a ceremony to posthumously award the “Gold Life Saving Medal” to seven African American men who had performed a “daring rescue off North Carolina’s Outer Banks in 1896” by saving the lives of several people on a sinking ship while a hurricane raged around them.82 With the essential help of some outside researchers, Rochon was able to right a wrong and shine a light on bravery and skill that had been overlooked due to racism. Rochon was the first person besides former president and Mrs. Bush to greet President and Mrs. Obama in the White House. President Obama would soon be needling him about installing a basketball court on the White House grounds. In a final example of history coming full circle, Rochon, in one of his last public events as White House chief usher, attended the U.S. Coast Guard Academy graduation ceremony of Patrick George Bennett III, his grandson, held in May 2011. The commencement speaker that day was none other than President Barack Obama.83

When Admiral Rochon left the White House to work in the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, President Obama also broke the mold when he selected Angella Reid to be the first African American woman (and first woman, period) to serve as chief usher. Reid is a Jamaican national who earned her chops in the hotel management industry. Before the White House, Reid was in an upper management position at the Ritz-Carlton properties in Pentagon City, Virginia; Miami, Florida; and Washington, D.C. Prior to her tenure with the Ritz-Carlton, which began in 2008, Reid was general manager at the Hartford Marriott Rocky Hill Hotel in Connecticut and director of operations at the Renaissance New York Hotel in New York City. Reid holds a degree in hospitality management from the Carl Duisberg Gesellschaft School in Munich, Germany, and is conversational in German and basic Spanish.84

When the Obama White House announced Reid’s hire, they elaborated on her duties in a way that gives much more clarity to what the current job entails. As chief usher, Reid would be responsible for overseeing all aspects of the operations and activities within the Executive Residence and on the Executive Residence grounds. Among her many concerns, Reid would oversee management of the Executive Residence to ensure activities and resources are used efficiently and effectively. In addition, she would maintain close liaison with the White House Historical Association, the Committee for the Preservation of the White House, the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, and other related entities to maintain and preserve the historic People’s House. Reid would also oversee “the annual inventory of White House property, conducted by the Office of the Curator and the National Park Service.”85 Reid believes that “genuinely caring for people” is the secret to success.86 Mindful of the same concerns that had plagued George Washington and Samuel Fraunces more than two centuries earlier, the New York Times reported that Reid was “not [hired] to make the house more luxurious … but simply to bring its various functions a bit more up to date.”87

Over the span of roughly 150 years, two-thirds of presidential history, African Americans have had the awesome responsibility of making sure that things ran smoothly wherever the president lived, especially concerning the food operations. In the nineteenth century, the White House operated as its creators first contemplated, akin to the big house on a plantation. With the increase of staff, the Executive Residence has morphed to the point where it operates like a high-end hotel. In that context, it makes perfect sense that a hotel industry person currently runs the residence’s operations. As the steward, maître d’hôtel, or chief usher, these powerful people literally and figuratively set the table for the presidential culinary story. As we’ll see next, it was the personal chefs, whether enslaved or free, who ultimately translated the president’s culinary hopes and dreams into an edible reality.

Recipes

MINTED GREEN PEA SOUP

This is a culinary shout-out to one of George Washington’s favorite foods, sans arsenic. White House executive chef Walter Scheib developed this recipe, and it quickly became a favorite for First Lady Laura Bush. The soup is regularly served at the George W. Bush Presidential Library’s restaurant in Dallas, Texas, where I first savored it.

Makes 4 servings

1 1/2 cups freshly shucked or frozen peas

1 tablespoon butter

1/3 cup julienned leek whites

1/4 cup diced onions

4 cups chicken or vegetable stock

1/4 cup chopped mint

1/2 cup heavy cream

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

4 mint sprigs

1. Blanch and cool the peas; reserve 2–3 tablespoons for garnish.

2. In a soup pot over medium heat, cook the leeks and onions in the butter until tender, 3–4 minutes.

3. Add the stock and simmer for 4 minutes.

4. Add the peas and mint and cook for 2–3 minutes, or until the peas are tender.

5. In a blender or with an immersion blender, purée the soup until very smooth; strain the soup into a bowl through a fine-mesh sieve and discard the solids.

6. If the soup is to be served hot, return the soup to the soup pot and add the cream and lemon juice and reheat gently. If the soup is to be served chilled, cool it quickly by placing the bowl in an ice bath and then add the cream and lemon juice.

7. Garnish with reserved peas and the mint sprigs.

BISON MEAT BRAZILIAN ONIONS

Few of Samuel Fraunces’s recipes survive, but one of the more famous ones that do was his “onions done in the Brazilian way,” which was served at his tavern that future president George Washington frequented. The original recipe appears in Martha Washington’s Rules for Cooking used everyday at Mt. Vernon; those of her neighbors, Mrs. Jefferson, Mrs. Madison and Mrs. Monroe, by Ann Parks Marshall in 1931. Here, with the help of Ramin Ganeshram, I developed a healthier version using seasoned bison, sweet onion, egg whites, and olive oil instead of the beef mincemeat and egg yolks called for in the original recipe.

Makes 4 servings

4 medium-sized sweet onions (like Vidalia or Walla Walla)

1/2 pound ground bison meat

1 green bell pepper, chopped

1 garlic clove, minced

1/4 cup beef stock

1/4 teaspoon dried sage

1/4 teaspoon dried oregano

Salt and pepper to taste

2 egg whites, lightly beaten

1/2 cup olive oil

1. Peel and halve the onions and parboil for 5 minutes.

2. Remove the inner core of the onions to create cups and set them aside. Discard the cores.

3. In a large bowl, combine the meat, bell peppers, garlic, stock, sage, and oregano and season with salt and pepper.

4. Fill the onion cups up with the meat mixture, packing them just enough to ensure that the mixture doesn’t fall out.

5. Brush the tops of the meat mixture with the egg white wash.

6. In a large frying pan, heat the olive oil over medium heat. Invert the meat-packed onions into the pan and cook for 5 minutes, or until the meat mixture is cooked through.