5. Eating on the Run

After all is said and done the man who is chiefly responsible for the comfort, and in a large degree for the welfare, of the presidential party, rides in the last car of the train. He is a colored man, and he is in charge of the culinary department of the presidential train. Before he is selected the whole force of the road is carefully scrutinized. He is chosen as one among a hundred, and as a rule feels not only the responsibility but the honor of his appointment. It is told of the chief cook on a previous presidential journey that after an especially fine breakfast the president expressed a desire to see and congratulate the chef on his triumph. Word was taken to the magnate in his special car and he sent back word that if the president desired to see him he could be found in the kitchen.

“On the Presidential Train,” Coalville Times, 17 May 1901

It is when the president departs the White House and goes on a trip that the presidential food story becomes most complex. George Washington found this out early in his presidency whenever he contemplated travel anywhere other than back home to Mount Vernon. As presidential historian Richard J. Ellis observes, “Americans in the early republic did not want the president parading like a monarch, but nor did they want him campaigning like a mere politician…. Americans wanted reassurance that their president traveled as one of them, unburdened by monarchical pretensions.”1 Most of a president’s daily life is hidden from public view unless the White House grants access to outsiders. When the chief executive boards a train, plane, or yacht, these vehicles, infused with the presidential aura, become, for the press and the public, brighter, shinier objects than even the White House. Consequently, when a president travels, concerns about cost, diet regimens, food safety, presidential comfort, press interest, and public perception are heightened. Throughout American history, African American cooks have been on the move with the presidents to help manage the immense juggling act involved—and to attempt to assuage all fears.

Presidential travel cooks faced different challenges than their contemporaries who cooked in the (by comparison) comfortable White House kitchen did. They had less space to cook in and less downtime because they had to do shopping, preparation, and cleanup with fewer personnel. Also, those involved in mobile presidential food service have often had to perform multiple duties in addition to cooking. The reward was that the confined space of a boat, plane, or train often afforded the cooks more familiarity with the president. In this chapter, we learn about the railroad dining car cooks, yacht mess attendants, and flight attendants who nourished our presidents through the experiences of Joe Brown, John Smeades, William Letcher, Delefosse Green, Lizzie McDuffie, Daisy Bonner, Sam Mitchell, Ronald Jackson, Charlie Redden, Lee Simmons, and Wanda Joell.

With his restrictive views on presidential travel, President Washington set a precedent for later presidents from which they were reluctant to stray. Washington chose to travel in as low key a manner as he possibly could—he took few trips, and when he did he traveled by stagecoach with a small retinue of servants, he stayed at private homes as much as possible, and he often refused to be greeted with huge public fanfare. The biggest prohibition felt by presidents in these early years was traveling abroad. Why? Americans had such an aversion to monarchy that they didn’t want their own president to be seen as if cavorting with monarchs—an inevitable occurrence when a president was received by a foreign head of state. A few presidents, including Benjamin Harrison and William McKinley, were so slavish to this early travel taboo that they hilariously tested it by going right up to the Mexican border but not crossing over.2 Theodore Roosevelt finally broke the unofficial proscription in 1906 when he traveled to inspect construction of the Panama Canal. Since then, “modern presidents have typically spent between one-third and one-half of their time away from the White House.”3

Presidents freely and exuberantly, however, explored every inch of domestic territory that they could. Before the 1820s such travel was by horse or stagecoach. When the journey lasted longer than a day, the president dined at a designated inn, at a restaurant, or in someone’s home. By the mid-nineteenth century, the “iron horse,” as railroads were nicknamed, greatly expanded a president’s ability to conduct business and politick away from Washington, D.C. Yet, this mode of travel was never baggage-free, as Von Hardesty, a curator at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, records:

The frequent use of trains by presidents in the nineteenth century and into the early decades of the twentieth century gave birth to renewed concern over the perceived monarchical aspects of the American presidency. Typically, presidents traveled in private cars, which often were richly appointed. By necessity, these train cars were borrowed from railway moguls and rich Americans, because no funds had ever been appropriated by Congress for the construction of special railway cars for the exclusive use of the chief executive. One private car, dubbed the “Maryland,” served several presidents in grand style, including Rutherford B. Hayes, Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison, and William McKinley. More a palace on rails, it was fifty-one feet long with four separate compartments. The parlor was lavish, with sofa, marble-top table, chairs, and decorative mirrors. Such luxury renewed the old debate on what is appropriate for presidential travel in a democracy.4

At first, presidents traveled merely as honored guests of the railroad companies—and sat among the regular, commercial passengers. Later, railroad moguls, as a matter of pride and also to curry favor, loaned their own private luxury railcars to the president to use. On 9 August 1849, President Zachary Taylor became the first president to travel in such luxury when he took a trip from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore. Ellis relates, “Affixed to the rear of the waiting train was a ‘large, new and elegant car’ that had been provided by the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad company ‘for the exclusive use’ of the president. Taylor, however, ‘respectfully declined’ to use the special car, preferring instead, the Baltimore Sun reported, to take ‘his seat in common with other passengers.’”5 Even then, President Taylor realized that the “optics” (to use today’s political language) of having a tricked-out train were bad. Several presidents followed suit, and rail travel was discouraged unless deemed absolutely necessary.

After the Civil War, presidents felt less apprehensive about traveling in specially outfitted railcars, but the practice invited criticism. The postbellum decades saw a great increase in the power and wealth of railroad companies. Along with such growth came a deepening feeling among the public that railroad company owners and executives had politicians in their back pockets and influenced them to enact laws and policies that enriched the owners at the expense of the working class. Having presidents travel in luxurious railway cars only enhanced that sentiment, and it often seemed that what would most draw public ire was the absolute splendor of the railway dining cars. Yet, the public eventually, if begrudgingly, accepted that presidents were special people who deserved some comforts—including a loaned cook from the railroad, usually the railroad president’s private cook. The ultimate in railroad comfort were the Pullman dining cars, so named after George Mortimer Pullman, who founded the “Pullman Palace Company” in the 1860s. The first Pullman dining car was constructed in 1868 and was appropriately titled the “President.” According to the Pullman Company Historic Site website, the President was Pullman’s “first hotel on wheels … a sleeper with an attached kitchen and dining room. The food rivaled the best restaurants of the day and the service was impeccable.”6 These dining cars were overwhelmingly staffed by African Americans—because that fit the social order of the nineteenth century:

With the advent of the dining car, it was no longer possible to simply have the conductor and porters do double duty; a dining car required a trained staff. On the Delmonico, two cooks and four waiters prepared and served up to 250 meals a day. Later, depending on the train and the sophistication of the meals, a staff could consist of more than a dozen men: a steward, a chef, three or more cooks, and up to ten waiters. Pullman resolved the staffing issue by hiring recently freed house slaves. They were experienced and skilled at service, and he believed they would be polite and deferential to his passengers. Moreover, since they needed jobs, they would work for less money than whites. As discriminatory as his policy was, it did have some positive results. The Pullman Company became the largest employer of blacks in the country. Within the black community, working for Pullman meant steady employment, travel, and respect. One could take pride in wearing the Pullman uniform. Nevertheless, the men were underpaid and overworked even by the standards of the time.7

As the nineteenth century progressed, the railroads relied less on the labor of freed slaves but still drew heavily on a black labor force. While overworked and underpaid, Pullman workers, recent histories have shown, came to play a significant role in the development of workers’ rights that benefited African Americans in particular and all American workers in general.

By the twentieth century, a racial division of kitchen labor developed on the railroads so that “generally chief stewards and chefs were white and assistant cooks and waiters were black. But blacks did become chefs and were able to add dishes they knew and loved to the menu.”8 One such example is Chef Joe Brown of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. Chef Brown was born on 22 January 1859 in Charles County, Maryland, near the village of Pomonkey. When he was of working age, he landed a waiter job at the Relay House, a famous dining spot along the B&O. Brown was eventually made a cook, and among his famous customers were President and Mrs. Rutherford B. Hayes. The Hayeses were so taken with Chef Brown’s food that they arranged for him to be their personal railroad chef when they traveled to Deer Park, a summer resort in Maryland owned by the B&O.9 Brown’s encounter with a second president was much more tragic, given what he witnessed on 2 July 1882:

There was burly, vigorous President Garfield, who would eat nearly anything the chef set before him. The memory of that incident in Sixth Street Station, Washington, is as clear in Joe’s mind as on the day it happened. He had stocked his pantry with solid food and was waiting besides the special when the Presidential party came along. Mr. Garfield had greeted the chef and gone when Joe saw the assassin, Guiteau, leap forward. “I didn’t know what was happening,” he says. “There was the crack of the gun and the President fell into the vestibule. We were too dazed to stop Guiteau, and he ran from the station and Mr. Garfield was carried into the station.”10

After Garfield was placed in the convalescent care of White House steward William T. Crump and caterer James Wormley, Chef Brown went on to serve thirteen administrations—from President Garfield to President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. During his amazing career as a railroad cook, fortunately, most of his experiences were less traumatic. The Baltimore Sun reported, “One of the secrets of Chef Brown’s long, successful service is that he always tried to remember what his ‘regulars’ liked. He knew the appetites of the presidents and catered to them. Most of them … liked plain food well prepared. A notable exception was President Franklin D. Roosevelt, whose tastes ran to richer foods, and especially to game.”11 Brown’s story would make a fascinating book—just think of all the historical, social, and technological change that he witnessed during his career of fifty-plus years.

While we have few descriptions of the interior of presidential railcars, the Kansas City Times reported that in March 1893, President-elect Grover Cleveland rode from New York to the B&O railroad station in Washington, D.C., in an electrified railcar with “an observation room at the rear, a dining room, two bedrooms, a kitchen and a wine cellar.”12 Railcars took a more luxurious turn in the early 1890s, based on this description of the dining car used by President Benjamin Harrison:

“Coronado” is the name of the dining car. The furnishings of the dining car proper are supremely aesthetic. Seats and seat backs are of pearl gray straw, harmonizing thoroughly with the silver lamps and silvery metal work and contrasting artistically with oak woodwork and green plush curtains. The kitchen is presided by an experienced Afro-American cook, which fact is noted cheerfully by the people of his race as a slap at the French “chef.” The steward’s pantries and refrigerators are laden to their utmost capacity with bottled goods.13

Even railway dining cars could not seem to escape the ongoing rivalry between African American and French cooks.

Dining cars like the Coronado set the standard for presidential rail travel for years to come. And don’t think that just because the president dined in a railcar that there was a steep decline in the quality of his meals. When President Ulysses S. Grant traveled by rail on the Chicago, Alton & St. Louis Railroad circa 1869, the St. James dining car had the following bill of fare for an eight-course meal:

Soup—St. James soup; Fish—Baked white fish with tomato sauce; Boiled—Leg mutton with caper sauce, ham with champagne sauce, pressed corned beef and tongue; Roast—Lamb with mint sauce, loin beef, chicken with giblet sauce; Entrees—Prairie chicken with Huntsman sauce, Mallard duck with currant jelly, Queen fritters with cream sauce, Maccaroni a l’Italienne, chicken sauté with rice; Vegetables—Green corn, hot slaw, lima beans, stewed tomatoes, squash, new beets; Pastry—Peach pie, jelly tarts, apple pie, sponge pudding in brandy sauce, and finally for the Dessert course, wine jelly, brandy jelly, ice cream, watermelon, apples, tea, chocolate and coffee.14

Railroad chef John Smeades, who first cooked for President Theodore Roosevelt, got national attention for his cooking exploits on the dining car Ideal during President William Howard Taft’s cross-country railroad trip in September 1911. As discussed in chapter 1, perhaps no other president used his train to play hooky from his diet more than Taft, and he must have considered Chef Smeades his accomplice-in-chief. The First Lady and White House physician couldn’t have been pleased with press reports of the president’s prodigious railcar eating like this one printed in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

John Smeades is a big man and a black one. He has to be big for he cooks for another big man, and that is a big job. And it is likely that his color helps him withstand the heat that is part of his job. John cooks for the President; rather to be accurate, he has cooked for the President during the long journey across the continent and back that began on September 15. Cooking for William Howard Taft is no child’s play. It is Big Business with capital Bs. The President eats heartily, and eats often, so John Smeades rarely has any spare time.15

Smeades went on at great length about the various foods favored by Taft: a big, thick, juicy steak with the blood oozing out and a side of bacon; “plenty of green vegetables, a delicious salad of romaine and quartered tomatoes, with plenty of French dressing thickened with Roquefort cheese”; fried cauliflower, “a couple of chops and two or three lightly boiled eggs makes a breakfast menu”; fruit before and after every meal, including “grapes, peaches, oranges, oranges, melons, pears, apples, plums”; and chicken, shellfish, boiled salmon, and game (canvasback duck, elk, and deer). Chef Smeades also clarified, “But [President Taft] is not a greedy eater. He eats just what he feels he needs, and will never suffer from overeating.”16

President Woodrow Wilson, a tall and thin man, set a sharp contrast to Taft in many ways, but he loved food just as much and had a knack for getting the best cooks the railroads had to offer, including Chef William “Letch” Letcher. Decades in the making, the extraordinary reputation Letcher achieved as a chef could not escape presidential attention: “‘Letch’ is the Pullman company’s official chef to President Wilson en route, just as he has been commander of the kitchen aboard presidential cars for a number of years. And when it comes to cooking—well, ‘Letch’ gets all the medals. He can cook a steak with a touch of real art. He makes a jelly omelet that is worthy of poetry. And his rolls, his fried chicken, his coffee, and other dishes are beyond description even by a connoiseur [sic] in the good things in life.”17

Another chef in President Wilson’s railroad kitchen was Delefosse Green, who was described in a newspaper as a “king of cooks.” Green started as a butler after finishing high school and before becoming a railway cook. He first cooked for President Taft when he traveled by train and later became one of President Wilson’s favorites. When a local newspaper interviewed him, Green gave readers a rare peek into the work life of a high-end presidential railroad cook. The newspaper even described how he handled grocery shopping:

Whenever the private train drew up for a stop in any city, there would presently emerge a stoutish neat, bustling colored man, who would hail a taxicab and hurry away to the best available market. Here he would shop around as might any busy housewife, and no market-man would be aware of the fact that he was selling food for the table of the President. Receipts for the purchases would be made to Green and payment made in cash. So fresh food was always available. No product out of a can was ever used.18

Sounding a bit like an early spokesperson for the Paleo diet, Green continued, “‘Food should be cooked and served plainly. There should be few mixtures and few sauces. The manner of cooking followed by the early huntsman was the right method. Such food retains its flavor and is good for the stomach.’”19 Keenly aware of the public scrutiny our presidents received during the Prohibition era, Green took the extra step of reinforcing their collective virtue, stating that “one peculiar thing about his ten years of service as cook for presidents is that he never saw a man in that office smoke a cigar or cigarette or take a drink of intoxicating liquor. He wonders if there is something in the Constitution which forbids these indiscretions.”20

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt loved traveling by train, particularly to Warm Springs, Georgia. On these trips, Elizabeth “Lizzie” McDuffie and Daisy Bonner teamed up to provide presidential food service. Fortunately, their culinary adventures were documented, thus allowing history a unique window on how a president eats when on vacation. The first half of his dynamic duo in Warm Springs was Lizzie McDuffie. She mostly served the president’s food when he traveled but would help with cooking when asked. McDuffie was an interesting personality and has an amazing backstory wholly apart from what she did in the kitchen.

McDuffie, a native of Newton County, Georgia, was the Roosevelts’ most trusted maid, and she pitched in with cooking duties when the president traveled. She entered the Roosevelts’ orbit because her husband, O. J. McDuffie, had been FDR’s valet since 1927. Lizzie had a big personality, and her high school classmates predicted that she was destined for a stage career. Fellow maid Lillian Parks Rogers remembered, “FDR counted on Lizzie for her sense of humor, her sense of the outrageous. Even when we have guests—the old intimate friends, that is—FDR might send for Lizzie to liven things up a bit. Lizzie had show biz in her veins so she loved it. She had two Early-Muppet-style dolls and she would put on a show using various voices. One of the dolls was named Suicide and the other, Jezebel. FDR loved their fights and misadventures and roared with laughter.”21 McDuffie almost had a real chance at show business when a movie executive, who was dining in the White House, took one look at Lizzie and wanted to cast her for the role of “Mammy” in the blockbuster film Gone with the Wind. But despite FDR’s bragging, Eleanor Roosevelt’s personally lobbying the movie studio, and several newspaper reports, McDuffie was never seriously considered for the part that ultimately went to Denver, Colorado, native Hattie McDaniel.22

Kitchen staffer during the Kennedy administration, circa 1961. Courtesy John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum.

McDuffie had a political operative side as well. She half-jokingly called herself the “Secretary of Colored Peoples’ Affairs,” but there was much truth to it. When African American leaders couldn’t get the ear of the president, they would contact her with the hopes that she could draw his attention to a particular issue. McDuffie carried such weight because her political clout went well beyond the White House walls. In the 1936 presidential election, which wasn’t a guaranteed win for FDR, McDuffie was strongly motivated to get the president reelected, and she stumped for FDR in several cities that had an appreciable African American vote. The Baltimore Afro-American reported on her activities:

“No man is a hero to his valet.” For over 350 years since the Prince de Conde made the above statement, the world has debated on both sides of it. Last week, Mrs. Elizabeth H. McDuffie, White House cook and wife of President Roosevelt’s valet, taking the stump before an audience of 700 in St. Louis, classed Roosevelt with Lincoln “whose love of his fellow men has been something akin to the divine.” Here is a valet’s wife to whom her husband’s employer is a hero. That is news. But bigger news is the spectacle of the White House cook doing a swell job as a campaign speaker. Mrs. McDuffie was cheered in St. Louis, Chicago, and Gary. She went out to make one speech, did make three and could have made twenty-four more before returning to Washington in order to cook the President’s meals.23

This is arguably the first time an African American White House employee openly courted the black vote. Newspapers reported that McDuffie campaigned “gowned in black lace over a pink slip [with] her bobbed hair … combed straight back, and long pearl earrings dangled from her ears.”24 Her White House colleagues worried that McDuffie’s stumping blatantly violated the Hatch Act that passed earlier that year and prohibited federal employees from campaigning while on the government payroll. Remarkably, McDuffie was never charged, or chastised, for violating the new law. Newspapers described her as a “Special Assistant to the President” (much to the envy of White House housekeeper Mrs. Henrietta Nesbitt), and FDR summoned her to the Oval Office the day after the election to personally thank her for her efforts.25

FDR often brought McDuffie with him to Warm Springs, where he sought relief for his polio. He built a complex there that would eventually be called the “Little White House.” FDR loved his time there, and as Lillian Rogers Parks noted, “To understand the true FDR, you would have to see him at Warm Springs, Georgia.”26 His primary cook there was Daisy McAfee Bonner, an African American woman loaned to the president by a local wealthy family. Bonner was born in Ft. Valley, Georgia, and followed in her brother’s footsteps by going to Warm Springs to work at the Meriweather Inn. She learned to cook at the inn and then went into service in private homes.27 FDR started visiting Warm Springs in the 1920s while he was governor of New York. When he arrived, Bonner would be on campus ready to cook. During the entire gubernatorial and later presidential sojourns, Bonner stayed on campus and lived in a small servant cottage about twenty-five yards from the main building.

Bonner took every opportunity to get FDR hooked on southern delicacies like fried chicken, pigs’ feet (broiled, not the sweet-and-sour version that he liked), turnip greens, hush puppies, and cornbread. President Roosevelt really loved a dish called “Country Captain,” a chicken curry dish popular in Georgia. As to the dish’s origins, legend has it that in the 1700s, a wayward captain sailing from India to the West Indies accidentally landed in Savannah with a boatload of curry and other spices as well as the recipe for this particular dish. As for Bonner’s version, a frequent guest at presidential dinners at Warm Springs noted that FDR “told everybody, falsely, that her recipe was a secret, with 45 ingredients, which was a joke between Roosevelt and Daisy.”28

Whenever Roosevelt’s wife, physician, or meddlesome relatives were in Warm Springs, the dieting games began. In essence, according to presidential historian Jim Bishop, it was FDR, his stomach, Bonner, and McDuffie against the world:

Lizzie McDuffie could see the President by squeezing her face diagonally against the window screen. Daisy Bonner said, “You think the President looks feeble?” Lizzie nodded, “Yes, but he looks better than when he came here.” Like most women who were close to Roosevelt, Mrs. McDuffie and Miss Bonner loved the President. Daisy was possessed of the magical nostrums of cooks; if you feed a “peek-ed” man right, he will recover. “I know what I’m going to do,” she said. “I’m going to give him the things he likes to eat.” … She would feed him these things…. Daisy cooked; Lizzie served. When relatives maneuvered the menu, Miss Bonner obeyed, but she whispered a word to Mrs. McDuffie to take the platters to the table and whisper to the President “Don’t eat any of that.” Mr. Roosevelt never disobeyed the admonition of the cook. Sometimes, guests like Miss Suckley and Miss Delano would say, “Franklin, aren’t you going to eat what Daisy made?” Mr. Roosevelt would say, “I will eat some of that tomorrow.”29

Daisy Bonner at Warm Springs, Georgia, n.d. Courtesy Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

Their teamwork was one of the reasons that Warm Springs was so beloved by FDR, and Bonner took great pride in cooking for him. “Daisy always said she longed to ‘reach the top of my talent … so someday I might be president of cooking.’”30

Thursday, 12 April 1945, at the Little White House started as any other morning. That day, according to Bonner, “the President was ‘up’ and had breakfast in his room at 9:30. ‘He was always up at 9:30,’ [she said]. That day he had his usual breakfast, orange juice, oatmeal, melba toast and a glass of milk.”31 A few hours later, Bonner went about preparing FDR’s lunch, with a cheese soufflé as the starring attraction, which he was to eat while he read newspapers and sat for an artist’s sketching. The sequence of what happened next varies depending on who is telling the story, but the essential facts are the same. The New York Times offered a Bonner-centric version:

At 1:15, Mrs. Bonner had the cheese soufflé ready and she told the valet, Arthur Prettyman, “Get the President to the table. The soufflé’s ready.” The President always said, “Never put the soufflé into the oven until I come out of my room,” Mrs. Bonner explained. He was reading the Atlanta Constitution when the soufflé was ready. The papers had come late because of the bad weather and “Mr. Roosevelt had been worried about the mail. He’d asked the third time for the papers. So he’d gone right to reading when he came out.” The artist was sketching him—“He’d never sit for her—she had to catch him when she could”—the cook says…. Then, just as he went in, the President said what a terrific headache he had, and he slumped over in his chair. He never ate that soufflé, but it never fell until the minute he died.32

FDR died two hours later, so anyone who has made a soufflé knows that it would be miraculous for it to “stand” for a couple of hours. Bonner alerted the White House switchboard operator of the tragic occurrence, and, grief-stricken, she penciled on the kitchen wall her last tribute to the great man: “Daisy Bonner cooked the first meal and the last one in this cottage for … President Roosevelt.” It remains on that wall, preserved under a glass panel, to this day.33

A year later, Bonner shared her wonderful FDR memories in a newspaper interview. She considered opening up a business to honor the late president, in the way steward William Crump had done to memorialize President Garfield: “Soon though, she plans to sit in a little café museum, rock and tell the story of the President as she knew him. On Sundays she will supervise the making of ‘Country Captain,’ an involved chicken dish. It will be the only café in the world where ‘Country Captain’ can be had fit for a President. It was.”34 Bonner’s museum dream never came true, and she died on 22 April 1958 in Warm Springs, Georgia.35

Samuel Clayton “Mitch” Mitchell was the last great presidential railroad cook to serve during the glory days of rail travel. According to a 1952 newspaper profile of him, Chef Mitchell, a South Carolina native, worked for Presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt, but his big promotion came when he was put in charge of President Truman’s dining car.36 “Mitch, former Pullman porter, is major-domo on U.S. Car No. 1. He readies the car, plans the menus, and gets the food aboard. If he needs extra help, he requisitions it from the presidential yacht Williamsburg.”37 Chef Mitchell nourished Truman on his famous whistle-stop tours around the country, including his famous “comeback” train ride at the end of the 1948 presidential election. On that trip, the iconic photo of the president smiling and holding up the Chicago Tribune with the headline “Dewey Defeats Truman” was taken. Many have concluded that he was smiling because of the huge reporting error, but I like to think that he was recalling a savory meal recently prepared by Mitchell. Presidential rail travel became obsolete with the dawn of the jet age, but Samuel Mitchell was able to keep up with the times, eventually becoming the majordomo of the reception room in the Kennedy White House.38

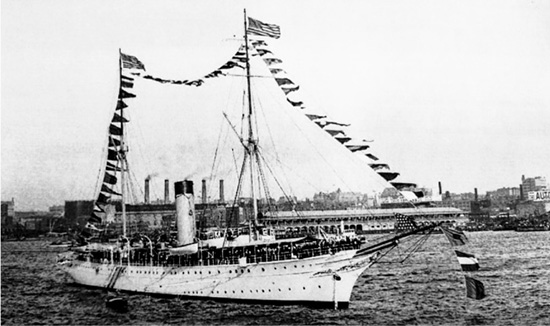

While presidents took to the rails for work and play, certain types of boats—notably yachts—were exclusively for presidential leisure. According to presidential yacht historian Walter Jaffee, “Abraham Lincoln was the first president to use a yacht. In May of 1862 he steamed down the Potomac River in the revenue cutter Miami to review his troops. Three years later the sidewheel paddle steamer River Queen was chartered for him, becoming the first vessel dedicated and maintained for a president’s use.”39 A succession of different boats used for play followed: the Despatch (Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880); the Dolphin, an unarmed cruiser (Benjamin Harrison to Harding); the more elegant Sylph (Theodore Roosevelt); the Mayflower (Roosevelt to Hoover); the Potomac and the Sequoia (Franklin D. Roosevelt); the Williamsburg (Truman); the Barbara Anne and Susan E. (Eisenhower); the Honey Fitz (Kennedy); and the Sequoia (Johnson to Carter).40

Presidential boat travel was typically controversial because it involved yachts, and few words scream snobbery more than “yacht,” as Captain Giles M. Kelly, who has written about the presidential yacht Sequoia, observes:

Presidential yacht USS Mayflower, circa 1912. Courtesy Library of Congress.

The term “yacht” has been a problem for Sequoia because some political figures, Presidents Jimmy Carter and Dwight D. Eisenhower among them, believed that close association with anything called a yacht while in office would tarnish their image because it might seem ostentatious. For that reason even today some congressional and administration leaders are reluctant to support her, let alone use her, though she is indeed a very modest yacht for the government of a superpower. At her inception, her designer referred to her not as a yacht, but as a “houseboat.”41

The prestige factor of the presidential yacht did cut both ways. Kelly related, “Years later, during his retirement, Gerald Ford was asked how he viewed Sequoia. ‘[She] was a superb yacht for special entertaining of presidential White House guests. The Sequoia was more informal than the White House itself, but significant as recognition of the prestige of the special guest…. I strongly believe [Sequoia] was a White House asset that could be used for constructive presidential entertainment.’”42

Aside from class perception, one of the biggest yacht-inspired headaches had a racial undertone, but this was not a black-white racial dynamic. While the railroad revived the French-versus-American cooking rivalry, a new, and artificial, ethnic culinary rivalry roiled the seas—African Americans versus Filipinos. A sad aspect of our military history was the continued denial of African Americans’ right to serve in combat positions, particularly in racially integrated military units. The powers that be knew that demonstrated heroism and patriotism would confer instant humanity upon the heretofore second-class citizen—and the real loser would be Jim Crow. Despite African Americans’ long years of dedicated service as cooks and servants to the U.S. Army’s elite officers, the U.S. Navy, puzzlingly, curbed even those opportunities as early as 1917. A newspaper article printed that year described the advancement difficulties that black sailors faced:

Quartermaster Boyd, of the local navy recruiting station, has just received word from Washington that a limited number of negroes may be enlisted in the navy as mess attendants. Only desirable applicants who have had previous experience in hotels, clubs, restaurants or private families will be accepted in this rating, and then only upon presenting recommendations from previous employers…. The duties of a mess attendant consists in waiting on officers’ messes and taking care of officers’ room and clothing.43

Because of all the extra hoops to jump through, few African Americans became “mess boys.” And when it came to presidential cooks, it was often through the ranks of the U.S. Navy that such cooks were promoted.

Strikingly, the next year the U.S. Navy ramped up its efforts to recruit Filipinos as servants and cooks:

Gunga Din, the humble servitor, immortalized himself by carrying water to the fighting heroes of another day. These cousins of his, Phillippine Americans, face the same chance at immortality by carrying soup and coffee to the U.S. Jacktar, on patrol or in battle. They have been permitted to join the navy as messboys, replacing those of other alien races in Uncle Sam’s flotilla. The first group of 152, soon to be supplemented by others, arrived at San Francisco from Manilla [sic] recently and were assigned to various naval units. Their training has run the gamut from soup serving to submarine spotting. And their mild faces camouflage fighting hearts.44

According to the history of the White House Mess that is printed on the back of its menu, it was aboard the USS Despatch that the U.S. Navy began its long affiliation with presidential cooking: “Since that time, the Navy has assigned their best Stewardsman to the White House to prepare the finest foods and provide outstanding food service for the president around the world.”45

By the time of Calvin Coolidge’s administration, only whites and Asians (a Chinese national named Lee Ping Quan and several Filipino mess attendants) served on the presidential yacht. The advancement prospects for African American mess boys improved, but civil rights leaders were eyeing the desegregation of the officers’ ranks. As the opening paragraph of a 1947 memorandum to the President’s Committee on Civil Rights stated, “The armed forces are one of our major status symbols; the fact that members of minority groups bear arms in defense of the country, alongside other citizens, serves as a major basis for their claim to equality elsewhere. For the minority groups themselves, discrimination in the armed forces seems more immoral and painful than elsewhere.”46

The legendary A. Philip Randolph, who successfully organized black labor in the 1930s and 1940s, pressed the issue on the White House. The discussion that Randolph had with President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox went like this, according to a book by William Doyle based on actual White House tape recordings:

FDR: I think the proportion is going up, and one very good reason is that in the old days, ah, up to a few years ago, up to the time of the Philippine independence, practically, oh, I’d say 75 or 80 percent of the mess people on board ship, ah, were Filipinos. And, of course, we’ve taken in no Filipinos now for the last, what is it, four years ago, two years ago, taken in no Filipinos whatsoever. And what we’re doing, we’re replacing them with colored boys—mess captain, so forth and so on. And in that field, they can get up to the highest rating of a chief petty officer. The head mess attendant on a cruiser or a battleship is a chief petty officer.

Randolph: Is there at this time a single Negro in the navy of officer status?

Knox: There are 4,007 Negroes out of a total force at the beginning of 1940 of 139,000. They are all messmen’s rank. (chatter)

FDR: I think, another thing Frank [Knox], that I forgot to mention, I thought of it about a month ago, and that is this. We are training a certain number of musicians on board ship. The ship’s band. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t have a colored band on some of these ships, because they’re darn good at it. That’s something we should look into. You know, if it’ll increase the opportunity, that’s what we’re after. They may develop a leader of the band.47

FDR’s reluctance to seriously grapple with the issue was discouraging, but the civil rights leaders pressed on in that particular conversation and beyond the White House. Thanks to dogged efforts of civil rights advocates, the officers’ ranks were progressively opened up to blacks in the 1940s and 1950s.

Yet, the presidential yacht’s culinary team remained made up of all Filipinos. Though African Americans rarely worked on the yacht, it is instructive to see what life was like for the Filipino crew. Fortunately we have a detailed account from Jack Lynch, a white crewman who served in the 1930s, of how they ate on the presidential yacht:

Since nearly everybody stood some kind of watch, there was a lot eating by shifts; one group would get up and another would be seated, etc. There was also a lot of informal eating—“snacking”—on board. There was always coffee and fresh milk in the pantry, and pies, cakes and breakfast pastry were delivered every day in port and left available in the pantry too. There was always a pot of soup on in the galley and sandwich materials were there, too. All hands had free run of the galley and the cooks really didn’t have too much work to do except underway.48

Fellow crewman Paul Harless added, “We could tell the cook what we wanted for meals or go into the galley at any time and fix our own. We called it ‘open galley.’”49 According to Jack Lynch, the crew ate typical fare on holidays—and made something unique out of the leftovers:

Thanksgiving, we had, of course, the traditional Navy holiday meal—turkey and so forth. The cooks took all the leftovers and concocted a great turkey soup, which was kept simmering on the rear of the galley range for days. That happened to be an early and especially cold winter [1941] and there was a steady procession of guys coming off watch, or taking a respite from work, into the galley for a bowl of soup. As the supply dwindled, the cooks kept adding new ingredients from whatever was handy, ham, vegetables, even oysters, until its original makeup, even its color, changed several times. At Christmas, when turkey parts again became available, it resumed its initial character. The cooks called it “perpetual soup” and it was still bubbling away on the last day of January when I left the ship.50

Creole food aficionados may find this “perpetual soup” akin to a bottomless pot-au-feu.

Speaking of “perpetual,” FDR fished nearly every weekend from May until November where the Potomac River emptied into the Chesapeake Bay. The crew joined him, and the cooks would prepare the day’s catch on the spot. When they caught eels, “the Filipino cabin boys loved them.”51 Even when away from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, the president often saw some of his White House favorites show up on the yacht’s menu. Lynch noted, “I recall that a favorite supper of President Roosevelt’s when we’d be returning on a Sunday night was scrambled eggs and little link sausages. When he had that, our cooks would prepare the same thing for the crew. We liked it, too.”52 The Roosevelt presidency was certainly high tide for presidential yacht use.

During the Truman administration, the growing idleness of the yacht’s crew yielded a benefit in that it helped to solve an emerging labor shortage at the White House. President Truman’s relationship with Congress was acrimonious, to say the least. But how much cooperation could the president really expect after he famously nicknamed the Eightieth Congress (January 1947 to January 1949) the “Do Nothing Congress”? After that, members of Congress acted as if they had nothing to do except exact revenge on President Truman during the budgeting process, especially regarding budget appropriations for the White House Executive Office.

The extensive White House renovations of the 1950s had created a need for more residence staff. The installation of air conditioning units had had a huge impact on work habits—as White House usher J. B. West recalled, “With air conditioning, Washington became a year-round city, the White House a year-round house.”53 But both West and the Trumans knew that getting more staff, especially for the refurbished kitchen, was a nonstarter with Congress. President Truman, who mused aloud about where to get White House kitchen help within earshot of White House chief usher Howard Crim, posited that the only option was military personnel. When West succeeded Crim as chief usher, Mrs. Truman, who had obviously been thinking about the same challenge, said, “Mr. West, I have an idea. We aren’t planning to use the Williamsburg as much as we have been now that it’s so pleasant up here [presumably due to air conditioning]. Could [we] bring some of the Filipino stewards in to be housemen and kitchen helpers? Do you think the Navy would approve?” That set the bureaucratic wheels in motion. West reports that “the Navy quietly acquiesced, assigning three seaman to the White House pantry and as housemen to help with heavy cleaning, vacuuming, waxing floors, and washing walls upstairs. Beginning with Mrs. Truman, the seamen became a White House fixture. Some even stayed on as White House employees after retiring from the Navy. Until that time, though, the Navy paid their salaries.”54 Some of the Filipino mess attendants were employed as butlers, but most went to staff a newly created dining space in the White House’s West Wing called the White House Mess.

White House Mess during the Reagan administration, 1986. Courtesy Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum.

President Truman’s naval aide, Rear Admiral Robert L. Dennison, first recommended the idea of a mess, and it became official by executive order on 11 June 1951.55 This navy-run, semi-exclusive dining space was immediately criticized as elitist. Critics also pointed out that, though staffers paid for their meals, the food often went for below market price. During the Nixon administration, diners were known to “get everything from soup to dessert—including a selection of meat or fish entrees—for two dollars. Those who really want to live it up can treat themselves to a steak or a double loin lamb chop, with the works, for $2.75. And, we note, no tipping is allowed.”56 By the time I worked in the White House, the prices had definitely increased. Those who had privileges but didn’t eat in the mess either brought their own lunch, ate in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Executive Office Building, or went outside of the White House compound.

Bradley H. Patterson Jr. of the Brookings Institution gave a nice description of this clubby, private dining room in his seminal work on White House operations:

Managed by the Navy, the White House Staff Mess consists of three adjacent dining rooms in the lower level of the West Wing that seat forty-five, twenty-eight, and eighteen, respectively, in paneled decorum, for each of the two noonday shifts. Some two hundred staffers and the cabinet are eligible [to dine there]. Dinners are now served as well—a reflection of the lengthening White House workday. Private luncheons in their own offices are available for West Wing senior staff, and carryout trays are provided for harried aides on the run. At the entrance to the mess, hanging noiselessly under glass, is a hallowed symbol: the 1790 dinner bell from the USS Constitution.57

I myself—when serving as a special assistant to President Bill Clinton—was promoted to the senior staff level at the White House, thus becoming one of those “harried aides.” And I had the privilege of eating in the very same White House Mess. I dined in the room only once (I can’t remember what I ate), but I often ordered carryout if I was working late, and I can personally attest that the mess’s cheeseburger at that time was absolutely glorious.

Significantly, while the White House Mess is located within the White House, it “is entirely separate from the first family’s kitchen and dining facilities in the Residence. The mess and the valets—a staff of fifty—are supervised by the presidential food service coordinator. Those who eat in the mess pay for their food, but the salaries of the Navy service personnel are borne by the Navy. When the president travels, mess attendants prepare some of the first family’s meals, and when the chief executive hosts a dinner during a state visit abroad, mess personnel oversee the food preparation.”58 And, also significantly, once the “presidential food service coordinator” position was created, African Americans were finally in the White House Mess mix.

Ronald L. Jackson served a long time as the presidential food service coordinator, starting in the Lyndon Johnson administration and working at least until the Reagan administration. Jackson, who achieved the rank of navy commander, did much to make sure that the mess upheld high dining standards. He once told the New York Times that the mess’s “soups and pies are all homemade” and explained how the skill of improvising, learned so beautifully while aboard a ship, affected everything the mess staff did, from carving realistic-looking flowers from vegetable peelings for the salad bar to making “puffy, crisp and buttery soufflé crackers that melt in the mouth.”59 Jackson wasn’t afraid to seek outside opinions to improve food service. When famous gourmet Gene Lang once ate at the White House Mess, Jackson asked for some recipes from the Four Seasons hotel to put on the mess menu.60

During Jackson’s tenure, the two worlds of the mess and the First Family directly interacted, typically, only on the Thanksgiving holiday, when the First Family would eat at Camp David, and on international trips. The Thanksgiving meals were supervised by Jackson and prepared by the White House Mess staff, and the dishes planned and served were fairly standard. For example, on the 1972 Thanksgiving holiday, Jackson supervised a meal of “roast turkey, bread dressing and giblet gravy with whipped potatoes, green peas and onions, and hot dinner rolls. Salad will be fresh cranberries with minted pears and dessert will be pumpkin pie with whipped cream.”61 However, selecting a traditional menu was not always a safe route for all presidents. When Jackson wrote a memorandum to the Carters proposing a similar menu for their 1977 Thanksgiving dinner meal, someone (presumably First Lady Rosalynn Carter) crossed out a certain side dish and wrote in the margins, “Jimmy doesn’t especially like green peas.”62

Jackson had plenty of additional opportunities to address presidential food quirks, and he was almost always a cool customer. Note, for example, something that Jackson experienced during the Nixon administration:

At Key Biscayne [a vacation spot favored by President Nixon], an automatic ice maker was purchased without authorization from the Secret Service. GSA [General Service Administration] officials said it was solely for the use of Secret Service and military personnel stationed there. But a GSA memo revealed that Cmdr. Ronald Jackson, the White House mess chief, had visited Key Biscayne on May 24, 1975, and noting the lack of an ice machine, said, “The President does not like ice cubes with holes in them.” The $421 machine was installed five days later. More recently, a Secret Service agent conceded the ice maker was for Nixon’s use and said it was “to ensure the President was not using poisoned ice.”63

Though President Nixon spent a good chunk of his second term in political crisis, he managed to shine in some emergencies during an election year. One time, he did so, interestingly enough, with White House food. In the wake of Tropical Storm Agnes, a devastating flood hit Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in late June 1972. A couple of months after the floodwaters receded, President Nixon visited the ravaged area to see how relief efforts were progressing. A Tennessee newspaper reported, “During the tour, he presented a $4 million disaster relief check to a local college to help its reconstruction. Told there was not enough food for a volunteer-organized Sunday picnic, the President later arranged to send Navy Cmdr. Ronald Jackson, chief of the White House mess, and six stewards to Wilkes-Barre Sunday with enough hamburgers, hot dogs, potato chips and soft drinks to feed more than 1,000 people.”64 I never before envisioned Air Force One being used as a food delivery vehicle, but this was a politically shrewd gesture on President Nixon’s part. He used the ultimate presidential perquisite to show that he cared. If “the train symbolized the president’s accessibility to the people,” historian Richard Ellis writes, then, “in contrast, Air Force One projects the power and majesty of the presidency.”65 Nixon illustrated that and more in one fell swoop.

Back aboard the presidential yacht, the mess crew moved back and forth between it and the White House Mess. Sometimes, other navy personnel were used to staff the yacht whenever the president wanted to sail. President John F. Kennedy probably went yachting the most frequently of all the presidents, doing so for relaxation. President Lyndon Baines Johnson used it extensively to lobby members of Congress. But the use of the presidential yacht came to an end when President Jimmy Carter implemented an austerity plan that eliminated many perks. President Carter never used the presidential yacht Sequoia, and it was on the top of his permanent hit list. The boat was thus auctioned off for a reported $286,000 in May 1977.66 Members of Congress were outraged that President Carter would sell a piece of his presidency to the highest bidder, and some tried to persuade wealthy friends to purchase it and donate it back to the Executive Office. Believe it or not, a private group did eventually purchase the Sequoia for more than $1 million. It was presented to President Ronald Reagan, but he refused to use it. That ended the illustrious history of presidential yachting at taxpayer expense. Now, our presidents may sail with wealthy donors at their expense or on their own time.67

Plenty of job opportunities aside from the White House kitchen exist in the presidential food system, but to obtain such jobs one typically must be in the military, which has been tasked to handle different aspects of said service. The U.S. Navy, as already mentioned, operates the White House Mess and food operations at Camp David, and the U.S. Air Force handles food on Air Force One. A recent example of an individual taking advantage of this military option is Chef Charlie Redden.68 Redden grew up in inner-city Wilmington, Delaware, while being the sous chef for a couple of “country girls”—his grandmother and mother—who liked to cook. Years ahead of Michelle Obama’s effort to change school lunches, Redden grew tired of the lunch offerings at Howard Williams High School. One day, while he was walking the hall, he peeked in on a commercial food preparation class and saw that students were eating much better food than what he was getting. He immediately made a plan to get in that class.

After apprenticing at a high-end hotel, Redden joined the U.S. Navy. While doing menial tasks aboard a ship, he noticed that the food service guys ate better than the rest of the crew. (Are you noticing a theme here?) He thus became a culinary specialist in the navy. Given his previous restaurant experience, Redden was quickly promoted and soon cooking for the highest-ranking officers wherever he served. In 1995, while he was stationed in Jacksonville, a spot opened up in the White House Mess, and—at an admiral’s suggestion—Redden applied. During the interview, he was asked why he should get the job out of the three hundred competitors. Without missing a beat, Redden promised to cook the current chefs there “under the table.” That got a hearty laugh from the interviewers, and Redden won the job. At the White House complex, he supervised the mess’s catering department, and in his spare time he earned an executive chef certificate from the American Culinary Federation. He thus became the first executive chef to work in the White House Mess.

During his stint with the Clinton administration, Chef Redden “traveled extensively with the Clinton retinue, checking out hotels and restaurants in advance of the First Family’s arrival, and preparing soups, pizzas, and spaghetti meals for their personal use.” But despite his high achievement, he still had to deal with issues of race at work. When he did advance work for presidential trips, the person on the other end of the phone would often assume that he was white, given his position. This happened most frequently when he planned the food operations for the president’s foreign trips. He would often walk into the kitchens of high-end hotels unannounced, only to have security called on him. Once he showed his credentials, the kitchen personnel would be astonished that an African American had such responsibilities. Even presidential chefs can experience “Cooking While Black.” Redden stayed on through President George W. Bush’s first term and left because he could no longer advance in rank, given his current job. His last event with President Bush was a trip to his hometown of Wilmington, where the president spoke at a predominantly black Boys and Girls Club. Today, Chef Redden does private catering in Maryland.

Though the American public grew weary and wary of presidential yachts, it has been in awe of presidential planes. Franklin Roosevelt was the first president to take to flight, though infrequently, on the presidential plane named the Sacred Cow. President Truman often flew on the Spirit of Independence, and President Eisenhower flew even more often on the Columbine. President Kennedy was the first president to utilize an airplane with the call sign Air Force One, which is technically any plane with the president aboard. First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy consulted with a well-known artist to create the plane’s signature colors and design, which last to this day.

The plane evokes elegance, grace, and style—but can the same be said of the food? Since Air Force One took to the skies, the flight attendants not only serve the food but cook it as well. They work out of two galleys. The galley in the front section handles meals for the president, VIP guests, and senior staff. The remaining passengers have their meals cooked in the rear galley. Though the flight attendants can make a wide range of foods, fried food is a nonstarter because, for safety reasons, no fryer is on board. French fries have been served, but they are reportedly “always soggy.”69 All told, “the crew can store enough food and beverages on Air Force One to serve everyone three meals a day for two weeks.”70 Presidential grocery shoppers wear civilian clothes while looking for the freshest, highest quality ingredients, sometimes getting “enough victuals for up to two thousand meals. Working in an area that occupies two full-size galleys, the steward crew can prepare up to one hundred meals at a sitting.”71

As it was on the presidential train, the comfort and safety of the president are always primary considerations. Former Air Force One steward Howie Franklin shed light on the established protocol in an interview with presidential historian Richard Norton Smith:

The flight attendants are responsible for making sure that nothing on Air Force One will cause a problem, even an upset stomach, for the commander in chief. “We make sure that anything that could be consumed in any way, shape, or fashion has not been tampered with,” says former chief steward Howie Franklin. The flight crew receives an itinerary from the White House and determines how many meals or snacks are needed for each day of a trip. Then the flight attendants propose a menu and submit it to the White House Mess, partly to avoid redundancy. “We wouldn’t want to serve salmon when the president had salmon the night before,” Franklin told me.72

After safety first, it’s comfort second. According to Kenneth T. Walsh, in his history of Air Force One, “The White House provides a list to the Air Force One crew of every new president’s likes and dislikes. The list also includes a rundown of the commander in chief’s health problems, allergies, and anything else the crew might find helpful in serving him.”73 The Air Force One culinary team consists of two teams of three people—a team for each of the two galleys. One person serves as the cook and is responsible for finishing the partially cooked food in the plane’s on-board microwave or small ovens. Another flight attendant helps with the prep work, and the remaining flight attendant is the bartender.74

As we learned with President Reagan’s unsuccessful attempts to get Bavarian cream apple pie, the potential excesses of this airborne cornucopia of food might be controlled only by the First Lady or by the White House physician. Walsh writes, “Particularly during the Bush and Clinton eras, the presidents and First Ladies have insisted on more low-fat meals and have preferred bottled water or diet soda rather than sugary soft drinks or alcohol, all for health reasons. Under Ford and Carter, breakfast would often be scrambled eggs with cream cheese, hefty sausages, fried hash brown potatoes, a biscuit or danish, and a small fruit cup. Today, breakfast on board tends toward bran muffins, cereal, fresh fruit, and yogurt.”75 Walsh further wrote, “During the Clinton years, it was First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton, not the president, who set the tone for everything on board, including the food. ‘If Mrs. Clinton was with us, the menu leaned heavily to chicken Caesar salads with low-cal dressing,’ [CBS news correspondent Mark] Knoeller said.”76 Still, just as in President Taft’s heyday, a president could indulge in eating any food if he really wanted to do so. “If the president was traveling alone, you could usually get a good old-fashioned cheeseburger,” Knoeller added.77

Not everyone was a fan of the aircraft’s bill of fare. Former Clinton White House press secretary Mike McCurry didn’t mince words when he said, “Not to offend the Air Force, but it’s basically military chow.”78 The most famous example of a disgruntled diner may have been when a famous broadcast journalist disapproved of the offerings: “The food service was a source of constant complaint. When Gerald Ford went to China in 1975, TV personality Barbara Walters flew on Air Force One and was not pleased when the stewards served her the dinner of the day—stuffed pork chops, which she spurned as too heavy. A flight attendant returned a few minutes later with a deli sandwich, and she was so displeased that she complained about the food on television.”79 Kenneth T. Walsh elaborated on the perspective of the Air Force One crew when he wrote, “Passengers are expected to eat what they are served. And the stewards are not pleased if a guest rejects a regular meal. That means more work for the galley. When a passenger asks for a substitute, such as a chicken-salad sandwich or similar light fare, the stewards try to handle the requests diplomatically but aren’t happy with the disruption of their routine.”80

The Obama Air Force One menu had a chef-driven vibe to its makeover of presidential plane food. The New York Times listed the meals offered on a 2012 flight: “a blue-cheese burger with lettuce, tomato and garlic aioli, accompanied by Parmesan-sprinkled fries. Chocolate fudge cake. Pasta shells stuffed with four cheeses, topped with meat sauce and shredded mozzarella, and served with a garlic breadstick. Cake infused with limoncello. Buffalo wings with celery, carrots and homemade ranch dip.”81 Nodding to one of President Obama’s most notorious campaign stumbles, a former staffer helpfully added some perspective to the common perception that President Obama’s plane food is always of the healthier variety: “It’s American fare, in that it’s not going all arugula on people,” said Arun Chaudhary, who was President Obama’s videographer from 2009 to 2011. “It’s not aggressively nutritious.”82

All in all, complaints about Air Force One provisions have been heard only now and then. A happy stomach often led to camaraderie among the crew. This would happen especially when a president took interest in specific crew members who assisted with presidential food service. Lee Simmons, who became an Air Force One flight attendant and presidential steward, shared his experiences in an oral history collected for the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Simmons was more involved in presidential food service as a steward, not as a cook, and he developed a remarkable friendship with President Ford.

Simmons was born in Akron, Ohio, and grew up in “the sticks of Alabama” but returned to Akron to work in a rubber factory before enlisting in the air force. During the Kennedy administration, Simmons recalled, “I was the first African American to be assigned as a crew member [as part of the presidential flying squadron that included Air Force One and a couple of backup planes. At first, Simmons flew on the backup planes.]. There were other African Americans flying on the airplanes in other capacities—White House staff or whatever. Or even maintenance people—some African Americans were in the maintenance squadron, and security. But as a crew member, which are [called] wings, I was the first one.”83

Being the only African American steward left Simmons in some awkward off-duty social situations:

I felt very welcome. I felt very comfortable. Of course, there were times when I knew that I should not be going to dinner with these guys in certain parts of the country—we’d go down in Texas. When they went to these hillbilly joints at night—I don’t want to say hillbilly, I’m sorry. Or go to the country and western restaurant to eat, I figured, ah, maybe I ought to skip that and stay at the hotel. But mostly the crews treated me nice. I was, for about ten years, the only African American on the crews whenever we flew overseas or stateside.84

Simmons also encountered professional difficulties because of his race. The higher-ups in the command chain wouldn’t assign him to serve on Air Force One or give him jobs that would put him in the pipeline to serve on Air Force One. Consequently, Simmons frequently flew on the backup planes and built up enough miles to create a “friends and family plan” with First Lady Pat Nixon. That opened the door of opportunity that he sought.

As a matter of fact, I flew with Mrs. Nixon—that’s where they made the mistake—they let me fly with Mrs. Nixon and the girls, so we got to be friends. And then occasionally I would get to fly on the main airplane, on Air Force One itself, instead of the backup—occasionally. Well, anyway, Mrs. Nixon saw me one day, she said, “Oh, there’s my friend, Lee.” From then on, later on, I was assigned as his personal steward on Air Force One—President Nixon. And he would tell me whenever there was a trip that Mrs. Nixon didn’t go with him, when she would represent the United States to inaugurations and to other functions for the government, he would tell me personally, he would say, “Lee, I want you to go with Mrs. Nixon. She’s going to Africa.” And I went to Africa with her.85

Mrs. Nixon took such a liking to Simmons that she even invited him and his wife, Jeannette, to attend a state dinner.86

Simmons had interesting encounters with President Nixon as well. On a return flight from Moscow, the president requested some eggs. Simmons dutifully went to the galley to fulfill the order, but the cook informed him that, being on the back end of a ten-day trip, the eggs had been deemed old and thrown away. Simmons informed President Nixon, who, with his chief of staff, Bob Haldeman, standing there, asked, “Well, do you have any chickens?” Simmons said he would check when Haldeman interjected, “No, the President was making a joke about chickens producing eggs.” Simmons added, “That’s what I remember about President Nixon’s humor.”87

Like so many other people involved with presidential food service, Simmons was an eyewitness to history and featured in this account of Nixon’s last flight on Air Force One: “Shortly after takeoff, Nixon asked Master Sergeant Lee Simmons, first personal steward, for a martini, which was unusual. He was a light drinker on Air Force One and rarely had alcohol at all in the morning. But on this day, he was, understandably, deviating from his routine…. He and Press Secretary Ron Ziegler sipped martinis in the president’s cabin, and ate a lunch of shrimp cocktail, prime rib, baked potato, green beans, salad, rolls, and cheesecake.”88 As Nixon’s presidency ended, Simmons enduring friendship with President Gerald Ford began.

Simmons first met Ford in 1972 on the way to Miami, where Ford would serve as chairman of the GOP convention.89 Simmons and then congressman Ford hit it off. After Ford became president, he picked Simmons be his personal steward while aboard Air Force One. Over time, they frequently dined together, particularly when Ford didn’t have guests:

He would say, “Lee, you got anything to do today or for dinner tonight?” And I would say, “No, sir.” I never had anything to do if the president wanted me to have dinner with him or lunch. I’m always available. “If you’re not doing anything, why don’t we just eat together.” Sometimes he would say, “Why don’t you find a restaurant—ask the Secret Service to find a restaurant close by someplace and let’s just go out and have dinner.” It would just be he and I. Of course, I ate that up. I thought that was great. Here I am sitting in the corner with President Ford having dinner and I’m sure the public is looking there and seeing this African American guy over here saying, ummm, wonder who that is? Must be the ambassador from Africa or somewhere—some diplomat.90

As part of his official duties, Simmons did what he could to satisfy President Ford’s craving for butter pecan ice cream—while playing “cat and mouse” with the White House physician. “Air Force One always had that ice cream aboard when President Ford flew,” Simmons said. “One day [White House physician] Dr. [William] Lukash put Mr. Ford on a diet and sent us a list of proper foods, and butter pecan ice cream was not on it. By mistake a lunch tray was handed the President with butter pecan ice cream on it. President Ford ate it up before touching anything else on the tray and told us not to tell Dr. Lukash.’”91 After all, that’s what friends are for.

Years after he had stopped flying on Air Force One, Simmons repeatedly spoke of President Ford’s enduring kindness: “He always was very thoughtful. I’d have dinner with him, [and] if we were at some function that he was going to make a speech, regardless of where it was at, he would always introduce me. He would tell people, ‘This is Lee Simmons, who has been on my staff for x number of years,’ and that kind of thing.”92 President Ford showed Simmons several more acts of kindness—he gave Simmons a job as his personal assistant after his presidency and flew Simmons to California as a guest on Air Force One to start the new job, giving him one last opportunity to sip “the famous Air Force One lemonade” while he was waited on by his former colleagues.93 After twenty years of service on the presidential plane, Simmons spent ten more years with Ford as personal assistant and valet.94 Their relationship proved that “flying the friendly skies” went both ways for them.

The skies are not always friendly. On 11 September 2001, our nation’s skies were filled with fear and terror. Senior Master Sergeant Wanda Joell, the first African American woman to serve on Air Force One, worked that day. Her military training and life experience kept a truly terrifying situation from becoming overwhelmingly chaotic. Joell, a native of Bermuda, wanted to be a flight attendant ever since her family flew on a plane to immigrate to the United States when she was six years old. “I don’t remember the exact airline—it had blue and white colors—possibly Eastern or Pan-Am, but I remember the flight attendant,” Joell related. “She was so nice to me, and made me feel comfortable. If I talked to someone who can draw, I could describe her exactly. That’s how much of an impression that she made on me. From that day on, I knew that I wanted to be a flight attendant.”95

Reagan-era Air Force One, rear galley, 2015. Author’s photograph.

Joell held on to that dream all through high school, and after graduation she immediately applied with several commercial airlines to be a flight attendant. The airline industry was going through a series of booms and busts at that time, so her application languished. She then decided to enlist in the military and get flight attendant experience there and apply later. She first spent some time at a military base in Texas acquiring some culinary training (though not as extensive as one would get with a commercial airline) before being assigned to a traffic management office position at the Royal Air Force base in Suffolk, England, jointly operated by the U.S. Air Force and the Royal Air Force. It was during that three-year stint (1982–85) when Joell learned that U.S. active duty personnel were serving as flight attendants on military flights. When she transferred to Grissom Air Force Base, Indiana, in December 1985, she immediately applied to become a flight attendant. She was interviewed on a Gulf Stream military plane that stopped at the base, and her paperwork was sent to Andrews Air Force Base in December 1986. In no time, she was officially a military flight attendant.

No one starts off working on Air Force One, so Joell first worked on planes that carried members of Congress. Joell noted that supervisors scrutinized “your customer service skills, appearance, timing, how you prepare a meal, etc. These things determine your prospects for promotion. Flight attendants are also rotated through different positions to see how you do.” Joell was promoted to the vice president’s plane (George H. W. Bush held the position at that time), also known by the call sign Air Force Two, and soon was splitting time between Air Force One and Air Force Two. In 1990, Joell became a full-time flight attendant on Air Force One.

On the culinary side, gearing up for a presidential trip on Air Force One involves extensive teamwork. According to Joell, “Before planning a meal, we got a list of the president’s dietary needs, likes, and dislikes from the White House. We then came up with a menu and sent it back to White House for approval. In addition to the approved menu, we made two or three extra meals, just in case.” Once the menu was approved, Joell and the other flight attendants shopped for the groceries. At this point in the process, the ground crew at Andrews Air Force Base pre-cooked most of the meal’s component parts, which were then frozen until reheated and further cooked by the flight attendants once the plane was in the air. Joell admitted that her team became known for some of their dishes, especially a French toast dish they developed on Air Force Two where they used Hawaiian bread. “We got a lot of compliments on that one,” Joell proudly said.

Joell has a lot of fond memories from working for four presidents, from President George H. W. Bush (“Bush 41”) until she had to mandatorily retire in 2010 for length of service while flying with President Obama. She had served the military for twenty-eight years and flown on presidential planes for twenty-four years. Yet, 9/11 was the most memorable day. On the tenth anniversary of that tragic day, Joell reminisced to a Suwanee, Georgia, television station, “We had to remain calm for our passengers as flight attendants, but at the same time, you’re still worried about the country,” she said. “I felt safe. I felt Air Force One was safe, but you’re still worried in general about what’s going on back home.”96 Still, Joell and her team were able to keep it together: “Everyone was doing their thing. It wasn’t chaotic. Everyone had a plan. We knew what we were supposed to do.”97 Joell has no problem focusing on the positive aspects of her service on the presidential plane: “I’ve got special memories that I can keep forever,” Joell said. “It’s still a special place in my heart.”98

Presidential travel cooks had a full range of experiences using limited equipment for a limited period of time. Their main concern was to take care of nourishing the chief executive—whether traveling by train, boat, or plane—until the desired destination was reached. As these travel cooks learned, presidents needed food, and food often served as comfort for the presidents.

Recipes

DAISY BONNER’S CHEESE SOUFFLÉ

Here’s the recipe for the miraculous soufflé that Daisy Bonner prepared the day that her beloved president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, died. Bonner always served this dish with stuffed baked tomatoes, peas, plain lettuce salad with French dressing, Melba toast, and coffee.

Makes 5 servings

1 tablespoon butter

2 heaping tablespoons flour

Pinch of salt

1/2 teaspoon prepared mustard

1/2 cup whole milk

3/4 cup grated sharp cheddar cheese

5 eggs, separated

1 teaspoon baking powder

1. Preheat the oven to 375°F.

2. Melt the butter in a saucepan and blend in the flour, salt, and mustard. Gradually add the milk, whisking constantly, to make a thin sauce.

3. Beat the egg yolks slightly and add them and the cheese to the sauce. Stir to combine.

4. Set aside to cool until ready to bake.

5. When ready to bake, beat the egg whites stiff with the baking powder.

6. Fold the egg whites into the cheese mixture.

7. Transfer the mixture to an 8 × 8-inch baking dish and bake for 30 minutes.

8. When the soufflé is done it should be very high and brown but soft in the middle.

9. Serve immediately.

HAWAIIAN FRENCH TOAST

Given the small galley on Air Force One, Wanda Joell had little latitude to create a lot of dishes, but this was one of her creations. She came up with this dish on one presidential trip because the crew wanted to do something new. This was one that President Clinton really enjoyed, and I think you will, too.

Makes 4 servings

1 cup eggnog

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

1 teaspoon cinnamon, plus more for serving

1 teaspoon ground nutmeg

8 slices King’s Hawaiian bread

Sifted powdered sugar to taste

1. Heat a frying pan over medium heat and coat with butter or nonstick cooking spray.

2. Thoroughly combine the eggnog, vanilla, cinnamon, and nutmeg.

3. Dip the bread in mix on both sides.

4. Fry until golden brown on each side.

5. Remove from the pan and dust with powdered sugar and extra cinnamon.

6. Serve with butter, fresh fruit, maple syrup, and a choice of meat.

JERK CHICKEN PITA PIZZA

Chef Charlie Redden takes great pride in this dish because it was the very first thing that he cooked for President Clinton. The White House Mess had a pita pizza on its regular menu, and Redden adds jerk chicken, a standby in Jamaican cuisine, to give it a unique spin. This was another one of President Clinton’s favorites.

Makes 4 servings

4 pita breads

12 tablespoons pizza sauce

1/2 teaspoon dried oregano (optional)

1/2 teaspoon dried basil (optional)

Sliced chicken breast strips

2 tablespoons jerk seasoning (I recommend Island Jerk Seasoning by Tropical Pepper Co.)

1 cup low-fat shredded mozzarella cheese

4 tablespoons Parmesan cheese

1/2 cup thinly sliced red onion (optional)

1/2 cup thinly sliced green bell peppers (optional)

Red pepper flakes, to taste

1. Place the pita breads on a cookie sheet.

2. Spread 3 tablespoons of the pizza sauce onto each pita.

3. Sprinkle 1/8 tablespoon each of oregano and basil, if using, onto each pita.

4. Toss the chicken strips with the jerk seasoning and arrange them on the pizza.

5. Top each pita with 1/4 cup of mozzarella cheese and 1 tablespoon of Parmesan cheese.

6. Top each pita with 1/8 cup each of the onions and bell peppers, if using. Season to taste with red pepper flakes.

7. Place the pizzas in the oven and broil for about 4–5 minutes at 425°F (recommended).