1. The Key Ingredients of Presidential Foodways

As I always told the Negro servants and dining room help that worked for me, “Boys, remember that we are helping to make history. We have a small part, perhaps a menial part, but they can’t do much here without us. They’ve got to eat, you know.”

ALONZO FIELDS, My 21 Years in the White House, 1961

You have probably heard a number of presidential conspiracy theories full of foreign intrigue, but perhaps not one that is as American as apple pie. President William Howard Taft was an apple-loving man, and it ran in the family. One newspaper reported, “The Taft family are fond of apples in almost any form. It is not publicly known that one of the invariable rules of the President and all of his brothers is to eat apples just before bedtime. This custom was started by Alonzo Taft, the father of the President, and his children have followed it consistently. Whether traveling or at home the President is never without apples.”1 One of President Taft’s favorite ways to consume the fruit was in the form of apple pie, and when he traveled by train he could get, arguably, the best apple pie on earth. President Taft owed this possibility to John Smeades, an African American man who ran the kitchen on the presidential train. One newspaper described Smeades’s apple pie as “a glory, a Lucullan feast, an eighth wonder of the world.”2 Though President Taft’s heart, mind, and stomach said “yes” to that famous apple pie, those who surrounded him—his wife, physician, and staffers—said “no” because they felt the president really needed to stay on his diet.

This temptation for President Taft presented a serious quandary for members of his staff. How could they be so close to apple pie greatness and not indulge? After all, he was the one who had to watch his weight, not them. In due time, the “Secret Order of the Apple Pie” was born with a membership consisting of the president’s key staffers: Surgeon Major Thomas L. Rhoads, Jimmie Sloan of the Secret Service, Charles D. Hilles, and Major Archie Butt. Their sole purpose was to devise a variety of schemes to eat Chef Smeades’s apple pie without President Taft ever knowing about it. But Taft invariably knew what was happening (as all presidents seem to)—when it came to food, he was hard to fool. At one point, he playfully confronted his deceptive doctor who had crumbs on his face from a recently devoured piece of pie: “‘Major [Rhoads], it is better to practice than to preach. Can’t I have a bit of that pie?’”3 Evidently, President Taft didn’t win this time, but he wasn’t always left disappointed.

Sometime around 1912, President Taft boarded a midnight train to his native Ohio and thought he was going back to a simpler place in time when he wasn’t on a strict diet. Fortunately for him, the First Lady and the president’s physician weren’t on the same train. Once the train left the station, presidential staffers Ira T. Smith and Joe Alex Morris relate, President Taft summoned the train’s conductor for an urgent request: “‘The dining car …’ Mr. Taft began shyly, ‘Could we get a snack?’ The conductor looked surprised. ‘Why, Mr. President, there isn’t any dining car on this train.’ The President’s sun-tanned face turned pink, with perhaps a few splashes of purple. His normally prominent eyes seemed to bulge.” Taft loudly beckoned his secretary, Charles D. Norton, to solve this problem, but Norton reminded the president of his dietary strictures and that he had already eaten dinner and wouldn’t miss breakfast. This only deepened Taft’s resolve as he continued to lobby the conductor: “‘Where’s the next stop, dammit?’ he asked. ‘The next stop where there’s a diner [car]?’”4 The conductor informed him that it would be Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and Taft responded epically, “‘I am the President of the United States, and I want a diner attached to this train at Harrisburg. I want it well stocked with food, including filet mignon. You see that we get a diner…. What’s the use of being President,’ he demanded, ‘if you can’t have a train with a diner on it?’”5

As one might guess, the presidential train made an unscheduled stop at Harrisburg, and a dining car was attached. Right around midnight, President Taft was happily dining on filet mignon. History is silent on what cook the railroad company roused from his slumber for the awesome, probably annoying (this time at least), and nerve-wracking task of preparing the president’s late-night meal. In all likelihood, it was an African American man. Now, “My presidency for a dining car!” isn’t a political slogan that’s going to win a lot of votes with the general public, but this food-related anecdote involving President Taft poignantly shows that the presidential food story can be a mix of joy and pain, of luxury and deprivation, and usually there was an African American cook right in the middle of things.

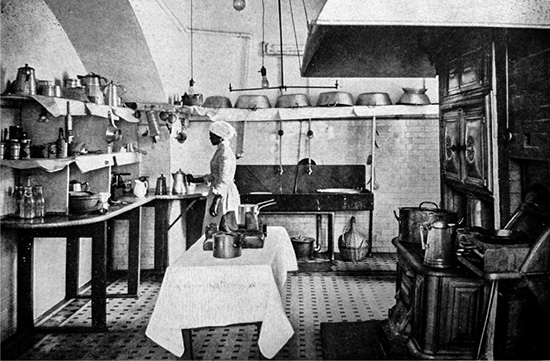

White House family kitchen, circa 1901. Mrs. John Logan, Thirty Years in Washington.

This book explores the role that African Americans have had on “presidential foodways”—places where culture, history, cooking, eating, and the presidency intersect. Presidential foodways involve a lot of moving parts. Rather than go into great detail about how those parts apply and interact with each other as the story unfolds, I’ll first describe them in this chapter. Each aspect of presidential foodways will be peppered with relevant anecdotes involving African Americans that are pulled from two centuries of presidential history. With some exceptions, the presidential food story that follows is told from the perspective of the African Americans who made those meals.

First, a few housekeeping notes. Because this work spans two centuries, some common terminology has changed over time, and I use several words interchangeably throughout the book. Thus, “Executive Mansion,” “Executive Residence,” and “president’s house” all designate the actual home the president had while living in New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C. Only the 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue location in Washington, D.C., has ever been called the “White House.”

Depending upon the historical source that I cite, “African American,” “black,” “colored,” and “Negro” indicate people of African heritage. And I use “chef” and “cook” interchangeably (which might be a bit controversial for some), because I draw upon the original definition of the term chef de cuisine, which simply meant the person “who presides over the kitchen of a large household” or “head cook”—regardless of whether or not the person had professional training.6 Indeed, many African Americans throughout early American history were called cooks when they might have properly been called chefs. This all changed in the United States when in 1976, “the position of executive chef moved from a ‘service’ status to a ‘professional’ classification in the U.S. Department of Labor’s Dictionary of Occupational Titles.”7 Today, the term “chef” is used to identify someone who has had some professional culinary education or training. Historically speaking, this has been a distinction without a difference. Rather than getting caught up in titles, President Lyndon Johnson’s personal cook Zephyr Wright summed it up nicely when she said, “‘Oh, I’m no chef … I just like to cook.’”8

Also, one should note that there are several types of cooking in the White House complex: the large, formal entertaining that happens in the building’s grand spaces, such as the State Dining Room; the small-group entertaining of VIPs in the President’s Dining Room; the family meals prepared and served in the private kitchen and dining areas on the Executive Residence’s second and third floors; the White House Mess, which provides a private dining space in the West Wing for high-level staffers (primarily run and operated by U.S. Navy cooks); and the small cafeteria in the Dwight D. Eisenhower Executive Office building. Though African Americans have their fingerprints on all aspects of the presidential cooking described above, this book primarily focuses on the behind-the-scenes cooking done for the First Family rather than on the high-profile state dinners.

In culinary school, right after a course on kitchen safety, students are taught how to get organized before they start cooking. Most cooks I know fall into one of two camps. The first camp consists of those who pull ingredients from the pantry and the refrigerator as they go along, hoping that they have everything they need to prepare a certain dish. If they don’t, it’s not too big a deal because they are confident that they can improvise a good result—usually without precise measurements. These people are called “dump cooks” or “scratch cooks.” I am not among them. I fall into the second camp, where I need to have all of my ingredients previously measured and laid out before me. This subdues the panic that would overcome me if I didn’t have everything that I needed in order to cook. This latter approach is called mise en place, which is French for “everything in its place.”

Let me borrow from the culinary world and declare that what follows is a literary mise en place comprising four major “ingredients” that make up presidential foodways.

First Ingredient: The President’s Influences on Foodways

THE PRESIDENT’S PALATE

What a president craves to eat is first, last, and everything in between for the White House kitchen staff. Most presidents have been wealthy people with their own personal cooks. Since familiarity bred culinary comfort, they often brought their own personal cooks with them to the Executive Mansion once they became president. If they didn’t have their own cook, they often tasked their First Lady with finding one. Given that assignment, a First Lady would dutifully tap her personal networks to find and vet someone who was capable of performing well in such a demanding job. Thus, for most cooks, the path to the presidential kitchen depended primarily upon on two things: whom they knew and how well they cooked.

Before installing their own cooks, First Families rely on the White House kitchen staff cooks to feed them in the interim—and to get it right. The staff cooks, working closely with the White House’s steward and chief usher as well as with the butlers, pride themselves on anticipating the needs of an incoming presidential family, especially concerning what they might first request to eat and drink as they settle in for those first few days of the presidency. Usually such requests are met without a hitch, but there have been some nerve-wracking moments when the staff missed the mark.

As longtime White House butler Alonzo Fields, an African American, recalled, White House chief usher Howell Crim faced a similar challenge: “One day the President [Eisenhower] gave the crew an unexpected problem. The chief usher, Mr. Crim, was told to get some yoghurt, and the housekeeper and Charles [Ficklin, the maître d’], like Mr. Crim, did not know what yoghurt was. This little incident nearly prevented my transfer [to become head butler] from being O.K.’d.”9 Fortunately, Fields was welcomed at work the next day.

THE PRESIDENT’S FOOD PHILOSOPHY

Besides what presidents put in their stomach, how they think about food affects their cook’s job. Most presidents have been extremely hands-off about White House food operations and have usually delegated such things to their spouse with the understanding that they would consistently get good food to eat. There have been exceptions. We have had gourmet presidents who were extremely interested in what they ate (Presidents George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Monroe, Chester Arthur, and Dwight D. Eisenhower). We’ve had others, like President Abraham Lincoln, who seemed fundamentally uninterested in food. One observer noted, “When Mrs. Lincoln, whom he always addressed by the old-fashioned title of ‘Mother,’ was absent from home, the President [Lincoln] would appear to forget that food and drink were needful for his existence, unless he were persistently followed up by some of the servants, or were finally reminded of his needs by the actual pangs of hunger.”10

Herbert Hoover exemplified the “food as fuel” perspective to the point of hilarity. Lillian Rogers Parks, an African American woman who served for decades as a White House maid, had the rare opportunity to witness presidential personality quirks up close. In her taboo-shattering memoir of her White House experiences, Parks wrote, “The President [Hoover] hardly took enough time to eat, so anxious was he to get back to work. All the servants and kitchen staff made bets on how long it would take him to eat. He averaged around nine to ten minutes, and he could eat a full-course dinner in eight minutes flat. They would come back saying, ‘Nine minutes, fifteen seconds,’ or what the time had been. Eight minutes seemed to be his record. For State dinners, though, he would slow down for the benefit of the guests.”11

Obviously, how finicky the boss is about how the food tastes can make the cook’s job very difficult. No president was nosier about kitchen operations than President Calvin Coolidge. Parks remembered,

Mama came home with a million funny stories having to do with the President’s sense of economy. He was always coming into the kitchen and personally instructing the help on how to cut the meat. He sought out Mrs. Jaffray [who supervised the kitchen staff] and gave her lessons in cutting corners, and once, when he heard the kitchen help griping about his interference, he fixed them with a beady eye and asked them, “Do you have enough to eat?” “Yes, Mr. President,” they agreed, snapping to attention. “Fine,” he said, and walked out.12

This high level of intervention was quite remarkable since President Coolidge built his public persona on being laissez-faire (“let do”) on everything else. Fortunately, most cooks did their job without such intense presidential oversight.

THE PRESIDENT’S SCHEDULE

If there has been a consistent thorn in the side of the presidential kitchen staff, it has been cooking for a commander in chief who is chronically late. Except for special occasions like a state dinner, where everyone knows the night will be long, members of the kitchen staff expect to work a manageable, almost routine, schedule and be home in the evening to spend time with their own families. From the Founding Fathers until the dawn of the twentieth century, our chief executives considered punctuality for meals to be a presidential virtue, which was good news for the kitchen staff. President Washington set the tone when he told a couple of congressmen who arrived late for a dinner he hosted at his presidential residence in New York City, “Gentlemen, we are punctual here. My cook never asks whether the company has arrived, but whether the hour has.”13 But by the twentieth century, the demands on the modern presidency often upset the place and timing of presidential meals. Theodore Roosevelt may have been the first president who implemented a “working lunch” by taking meals at his desk in the newly created Oval Office. Years later, his distant cousin Franklin Delano Roosevelt often ate his lunch from a heat-retaining enclosed cart that was wheeled by a butler from the basement kitchen to the Oval Office.

Working late or feeding a large number of unexpected guests has been the biggest source of irritation for the staff. As Parks wrote of Taft’s presidential kitchen, “No cook would stay. No wonder: the President was forever keeping the kitchen off balance by bringing any number of guests home with him without advance warning. This coupled with Mrs. Taft’s habit of looking into their pots and pans, made them decide that the honor of working in the White House wasn’t worth the strain on their nervous systems. Even the cooks who cooked for the help wouldn’t stay.”14 The kitchen staffs of Presidents Lyndon Baines Johnson and Bill Clinton would have certainly commiserated with their predecessors in Taft’s kitchen. The strain of working in the presidential kitchen often took a toll on the cooks and their families, but the African American cooks suffered on because there were few alternative jobs that carried the same prestige and relatively stable income.

Sometimes a cook’s rapport with the president allowed him or her to “turn the tables” and boss around “the boss.” This can happen only after years of familiarity, as was the case between Zephyr Wright (discussed in chapter 4) and President Lyndon Johnson, which Jim Bishop chronicled while observing Johnson for a day: “Mrs. Zephyr Wright, a middle-aged Negro who has worked as a cook for the Johnsons for twenty-five years, is a lady of poise. She is unimpressed with the Presidency, and is probably the only person who if a President is late for a meal can tell him, ‘Go sit in the kitchen until I fix you something.’”15 All is not lost, though, regarding punctuality in the modern age, for Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama reportedly stuck to their schedules in ways that would have made President Washington proud.

THE PRESIDENT’S WEALTH

In 1858, the Circular reported something that most people probably didn’t know: “For all domestic servants, … except steward and fireman, the President must pay for his own cooks, his butler, his table-servants, his female servants, his coachman and grooms, [etc.], as any other person does who employs such a retinue of servants. He supplies his table, with the exception of garden vegetables, as any other private person does by his own purse.”16 Early in our nation’s history, presidents not only paid for all of their domestic staff but also underwrote all entertaining costs. President Washington started this unwritten rule, and it endured for more than a century after President James Buchanan left office. This custom partly explains why so many slaveholding presidents brought their enslaved cooks and personal servants with them—it was a lot cheaper than paying competitive wages for a professional cook in an open labor market. The custom finally came to an end during the Truman administration, when Congress made presidential residential staff and entertaining a regular line item in the federal budget.

PRESIDENTIAL PREROGATIVE

Few incoming presidents have started their presidencies as perfect specimens of health. They are usually older, sometimes overweight, and often on some physician-ordered diet. Add to that the overwhelming stress of being president, and one has the sufficient conditions for an intense and persistent craving for junk food. Aside from their physicians, usually the only people who have saved the presidents from themselves have been their wives, who constantly and gently remind their husbands to watch what they eat. The First Ladies’ efforts range from being antagonistic to engaging in a playful cat-and-mouse game. Presidents, like any spouse, are interested in promoting domestic tranquillity within their own household, so if they stray from their diet, they do it on the sly. To do so, presidents have enlisted the help of other family members, trusted aides, and the White House residence staff. White House maid Lillian Rogers Parks shared, “Every now and then we would get a chuckle out of hearing that someone had conspired with the staff to smuggle the President [Franklin D. Roosevelt] something he liked to eat. Usually it would be something that needed no cooking or just warming up.”17 In time, these surreptitious food acquisition schemes got fairly complex.

White House family dining room, circa 1901. Mrs. John Logan, Thirty Years in Washington.

Second Ingredient: Others’ Influences on Foodways

The second ingredient in the shaping of presidential foodways is the people who surround the commander in chief—namely, his family, friends, and staff. These folks, as we will learn, restrict the president’s eating habits more often than one would think. It is not, however, accurate to think of this as a collection of people who want the president to be miserable. (That’s the job of the opposition party in Congress.) No, these are people who love the commander in chief and are trying to maintain balance in his life and to keep him vibrant in the job and hopefully around long enough to enjoy a long ex-presidency.

THE FIRST LADY

Few people know a president better than the president’s spouse. And while change is certain to come, through President Obama’s administration our presidents have all been men, and so my research has uncovered a great deal of influence by First Ladies. The First Lady knows the president’s aspirations, fears—and deepest food desires. Because of longstanding gender roles, the voting public, well into the twentieth century, expected most of our First Ladies to be model housewives. A First Lady had to be a good cook, keep her family healthy, maintain the household, and be a great hostess when called upon to entertain. Thus, First Ladies often supervised all of the culinary operations in the White House and became the “diet-enforcer-in-chief.” The head cook would report directly to the First Lady to ensure that the president stayed on the right nutritional course. Knowing what presidents like and dislike, their wives have traditionally planned all of the private menus and consulted with the kitchen staff on what to make (and sometimes on how to make it). When the commander in chief is kept on a strict diet by his wife, cooks can feel caught in the middle between the president, who is their ultimate boss, and the First Lady, who is their immediate boss. When the two are together, the First Lady consistently wins. Take, for example, President Ronald Reagan, whose face, according to eyewitnesses, would light up like a little kid’s when he boarded Air Force One and saw that Bavarian cream apple pie was on the menu. However, if his wife, Nancy, was with him, she anticipated what he would do, and according to one of the plane’s crewmembers, “she would tell him, ‘You’re not having any of that,’ and he would meekly acquiesce.”18

In his memoirs, White House chief usher J. B. West wrote about the time First Lady Pat Nixon made a late-night impromptu food request:

Steaks we had—juicy, fresh, prime filets carefully selected by the meat wholesaler, waiting in the White House kitchen for a family who, we’d heard, loved steak. But cottage cheese? Chef [Henri] Haller called to request a White House limousine. “For two weeks we’ve laid in supplies in the kitchen,” he wailed. “I think we could open a grocery store in the pantry. We’ve tried to find out everything they like…. But we don’t have a spoonful of cottage cheese in the house. And what in the world would be open at this time of night—and Inauguration night to boot?” So the head butler, in a White House limousine, sped around the city of Washington until he found a delicatessen open with a good supply of cottage cheese. The kitchen never ran out, after that.19

West and his team were mortified, but they shouldn’t have felt too bad after the yogurt episode with President Eisenhower. By coincidence, it was John Ficklin, Charles Ficklin’s brother, who rode around town in a limousine to get Pat Nixon’s cottage cheese. Who would have guessed that dairy products would cause the staff so much indigestion?

THE PRESIDENT’S PHYSICIAN

Surprisingly, the First Lady’s powers of persuasion aren’t always enough to keep a president healthy. Such was the case with First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Henrietta Nesbitt, the White House housekeeper during that administration, noted in her diary, “May 31, 1937—The President is cutting up an unusual tizzy-wizzy, as Mrs. R[oosevelt] calls it. She said he just never fussed over his food and this is most unexpected.”20 In such instances, Eleanor Roosevelt called for backup, and her call was typically answered by Navy vice admiral Dr. Ross McIntire,21 the president’s physician.

“Call on me if you need help,” [Dr. McIntire] said [to Mrs. Roosevelt] at the very start of the President’s tizzies, and he co-operated on the menus and tried in every way to get the President’s appetite back to normal. He sent to New York for specialists and finally he brought in doctors from the Naval Hospital, and a dietician arrived in uniform, and for a time the President ate everything he was told to eat, simply because it was “ordered by the Navy.” The President’s reducing diet came from the Navy and was the simplest on record: Cut out all fried foods.22

The president’s own personal doctor from his private life often became the presidential physician, but in recent years, the physician tends to be a military doctor assigned to the White House. Like the First Lady, the presidential physician had veto power on anything the cooks planned to make and serve the chief executive. More times than not, the dynamic duo of the First Lady and the presidential physician formed a dieting alliance that even the president couldn’t overcome, despite having several tricks up his sleeve.

WHITE HOUSE FOOD PROCUREMENT PROFESSIONALS

My blanket term for all of the people who shop for presidential groceries, once the parameters for the presidential diet have been set, is “White House food procurement professionals.” Historically, presidential cooks have seldom shopped for food themselves. From the late 1700s until the late 1940s, the stewards, housekeepers, maître d’, and food coordinators have discreetly bought the groceries. One of the presidential shopping hot spots during the nineteenth century was the Center Market, which opened on 15 December 1801, located where the National Archives Building now stands (700 Pennsylvania, NW). A few chief executives, notably Presidents Thomas Jefferson and William Henry Harrison, visited the Center Market themselves, which was demolished in 1931.23 Only in the case of an emergency—such as a lack of dairy products—did a butler, a member of the Secret Service, or some other staffer purchase food. Today, due to security concerns, food procurement is outsourced to contractors who are vetted by the Secret Service (and sworn to secrecy), or the culinary staff shop anonymously at local grocery stores.24 Regardless of who does the shopping, the procurers usually consult with the president’s head chef to make sure any proposed menus fit presidential tastes. Still, one can’t help but note that in this context, the people preparing the food are denied the joy of being at the market, getting to know the purveyors, and using their own discernment and senses to choose the ingredients with which they will cook—experiences that most personal cooks would have.

Some presidents have utilized the White House grounds for small-scale food production. President John Adams was troubled that the Executive Mansion didn’t have a kitchen vegetable garden when he arrived. To him, “a house could not operate without a garden.”25 That was one of the first things he took care of when he moved into the Executive Mansion. President Jefferson expanded its cultivation and yield. During the Andrew Jackson administration, the kitchen garden was moved to the southwest portion of the grounds.26 Historian William Seale argues, “It seems probable that the vegetable garden that spread southwest from the west wing supplied most of the needs of the table. The kitchen accounts of the various Presidents list few vegetables, and we know from the supplies purchased that through the summer and fall the cooks were much occupied with ‘putting up’ fruits and vegetables and otherwise making ‘preserves’ for the winter. These must have come from the garden.”27 The White House’s kitchen garden took a quantum leap in recent years thanks to First Lady Michelle Obama’s efforts (discussed in chapter 7).

There has been some small-scale husbandry over the years, mainly confined to a few dairy cows. Unlike many other households in nineteenth-century America, the White House grounds were not home to free-range chickens and pigs. Specific references to cows grazing on the White House grounds mark the Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, Jackson, William Henry Harrison, and Harding administrations.

Third Ingredient: White House Culture

The third ingredient that shapes presidential foodways is the culture, including the food culture, of the White House. The White House kitchen is a workplace just like any other professional kitchen, which brings an entire cast of people into the picture. I am sure that professional cooks everywhere will relate to how the food culture of their particular employer affects their ability to do their job.

THE WORKSPACE

Presidential chefs based in the Executive Residence have multiple workspaces. The starring attraction, of course, is the main kitchen, located in the White House’s basement. If one stood in the current White House kitchen, one’s first reaction might be, “That’s it? It seems so small!” The first White House kitchen was located under the Entrance Hall, on the basement floor, where the Green Room is now. An early description indicates that the first White House kitchen “was about 43 feet long and 26 feet deep [wide], with two open fireplaces, whose hooks are still standing.”28 In the early days of the White House, its visitors could look down through the basement windows and into the kitchen and get a preview of what was cooking while they waited to get inside.29 By the time of President Lincoln’s administration, the kitchen had moved to the northwest corner of the basement and shrank a little to “40 feet in length and 25 feet wide. Leading out of it is a smaller apartment, known as the family kitchen, which is about half the size.”30 Servants ate their meals in the smaller space. Today, after more renovations, the White House kitchen is now a slightly smaller 30 by 26 feet in the 55,000-square-foot Executive Residence.31

Over time, First Families added cooking spaces to meet their needs. FDR added a kitchenette to the third floor solarium to accommodate the numerous relatives who dropped in for visits—and also to escape the horrible food he usually got (more on that later). President Truman added the White House Mess dining space and kitchen (further explained in chapter 5) during his administration to give his key aides a precious perk. In order to have a more intimate dining environment for her young family, Jacqueline Kennedy turned Margaret Truman’s bedroom in the northwest corner of the second floor into a small kitchen, pantry, and dining space now known as the Family Dining Room. Given the space constraints of the existing White House, all of these additional cooking spaces are small and place a premium on functionality.

KITCHEN EQUIPMENT AND TECHNOLOGY

For most of its history, the White House kitchen has been on the cutting edge, being supplied with the finest and latest cooking equipment. Whenever the kitchen’s equipment was upgraded, African American cooks stood as the expert practitioners of the old technology and were the first ones to try out the new technology. For the first fifty years, White House food was prepared in one of two large fireplaces. President Jefferson installed an iron range in one of the fireplaces that “burned coal, had spits, and was equipped with a crane. His ‘stew holes,’ or water heaters, also used coal. Presumably the fireplace at the opposite end of the room was fueled with wood and operated like any cooking fireplace of the day.”32 In the hearth, the cook expertly prepared all presidential meals, including state dinners for up to thirty-six people.33

In 1850, Millard Fillmore installed an updated cast-iron, coal-fired range in the kitchen. However, this was not a peaceful technological transition. Historical sources note that the new stove was immediately rejected by an unnamed African American woman who had been the head cook since the 1820s. According to a newspaper account of the new stove’s installation,

its presence was first entirely ignored by the colored cook in charge, who continued to prepare the food served from her proprietary domain with the accoutrements with which she had been born and bred so to speak. Diplomatic pressure from Mrs. Fillmore in regard to the matter at first brought silent opposition and then incipient rebellion. The grapevine exchange in the kitchens of official Washington hummed with sympathy in the desecration of a great art that was involved before the altar of “dis contraption of de debil hiself which had done been unloaded on Marse Fillmore and his Missus.”34

White House kitchen, circa 1952. Courtesy Library of Congress.

President Fillmore took a personal interest in the settling the matter, and he walked to the U.S. Patent Office, got the diagrams for the stove, learned how it worked, and made several demonstrations to the disgruntled cook. The stove’s ease of use eventually won her over, and she, in time, became its fiercest advocate.35

The cast-iron range stayed a little more than a decade before it was moved to the new kitchen in the northwest corner. It soon developed mechanical problems that required Mary Todd Lincoln to call in the armed forces. A former soldier involved in the repair effort recalled in his memoirs, “Mrs. Lincoln told Colonel Butterfield [commanding officer of the Twelfth New York Militia guarding Washington] that the White House cook was in trouble—the ‘waterback’ of the range was out of order…. It certainly was a sight—four uniformed militiamen, with arms and accoutrements, marching into the White House kitchen, with an admiring group of colored servants looking on.” President Lincoln thanked the soldiers in advance, saying, “Well, boys, I certainly am glad to see you. I hope you can fix that thing right off; for if you can’t, the cook can’t use the range, and I don’t suppose that I’ll get any ‘grub’ to-day!”36 Once the range was working, it was a workhorse for decades. The earliest photograph of the White House kitchen shows that range as it existed during the Benjamin Harrison administration and with Dollie Johnson, his African American cook, nearby. We learn more about Chef Johnson in chapter 4.

By the twentieth century, the White House kitchen lost its status as the model kitchen of the United States. In the 1920s, Elizabeth Jaffray, the White House housekeeper of the time, observed, “The White House kitchens are … anything but modern. The only electric machine—with the exception of two or three small electric refrigerators—is an electric ice-cream freezer. There are really two White House kitchens—a very large one, and a reserve kitchen which is used only on the nights of special big dinners. Ordinarily the extra kitchen serves as a dining-room for the colored help. The dish-washing is done in the big kitchen by old-fashioned hand methods.”37 This slightly antiquated equipment managed to serve the presidential household well, but a decade later, the Wall Street Journal chided, “the executive mansion lacks many of the modern household appliances and equipment that new homes have today.”38

A resourceful FDR figured out a way to modernize the White House kitchen while politically draping it as “putting people to work”: he made the White House kitchen one of the federal Works Progress projects. As the press predicted, “the new stoves to be installed will mean learning new ways of cooking to the crack Negro staff, Ida Allen, chief cook, and her assistants, Catherine Smith, Elizabeth Moore and Elizabeth Blake.”39 When the work was completed, the revamped kitchen was shown off with much fanfare as First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt personally led the first tour: “The touring party was made up of newspaper reporters. They had come for the First Lady’s press conference but before they were through they saw everything from a collection of electric waffle irons to the napkin rings of the domestic staff…. [Mrs. Roosevelt] announced with obvious relief that Ida Allen and Elizabeth Moore, first and second cooks, brought here from the Governor’s mansion in Albany, approve of the new ‘cook stove.’”40 Once again, African Americans, as the first adopters of new cooking technology, given their status in the kitchen, had to approve the new equipment.

In addition to the new equipment, the renovation made the White House basement more functional. According to the Baltimore Afro-American, “The staff had been remembered in the renovation plans to the extent being provided, for the first time in [history], with locker rooms, a place in which to change their clothes and a rest room. Footmen, who in the past have been burdened with frequent trips up and down spiral stairs, leading from the kitchen to the main floor, also have some relief in store, through the installation of two large dumb waiters from the elaborate service pantry to another on the floor above.”41 Ultimately, the New York Amsterdam News, another African American newspaper, declared, “The new, most modern White House kitchens … have become the talk of the country, and [of] leading hotels, tea-rooms and dining rooms in Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, Atlantic City, New York, Ithaca and Boston.”42

The next kitchen upgrade came in the early 1950s during the last years of the Truman administration. At that time, the White House was literally falling apart, and it had become too dangerous for the First Family to reside there. Though the structural quality of the residence was improved, the cooking appliances remained relatively the same. From that time until the early twenty-first century, the kitchen equipment has been updated as needed—for example, getting a microwave installed—but not necessarily with the latest gadgets. Today, the White House kitchen is adequately equipped and doesn’t lag as far behind other professional kitchens as it has in the past.

COWORKERS

In his culinary memoir, former White House assistant chef John Moeller recalled a candid moment in the 1980s that he had with then White House executive chef Pierre Chambrin. Chef Chambrin “talked about the complex personalities you have to deal with [at the White House]. ‘It’s not so much the president or the first lady—it’s all of the other characters who work in and around the White House. Cooking at the White House is different.’ He made an important point: ‘It’s not a restaurant; it’s not a hotel. You’re cooking in somebody’s home—and you’re serving them almost every single day.’”43 Yet, this is not just any home—it’s a unique home, the most famous public housing in our country. Thus, the White House cooking crew is not a “dysfunctional, mercenary lot, fringe-dwellers motivated by money,” as former restaurant chef and current television personality Anthony Bourdain once described the typical restaurant kitchen staff.44 The U.S. Secret Service’s screening process makes sure of that.

As with any workplace, an inordinate amount of White House cooks’ happiness depends upon their relationship not only with their bosses but also with their coworkers. The presidential kitchen has been a multicultural workplace from the beginning, with people of different races, classes, sexes, legal status (enslaved or free), and countries of origin all working side by side. The earliest presidential kitchens were staffed by a five-person team: the steward or housekeeper, who purchased groceries and planned menus; a head cook in charge of all the meals involving the president; a second cook, who prepared meals for the residence staff; and two other workers who shared a variety of preparation and cleanup duties.45 By the 1880s, the work dynamic changed when outside caterers and chefs were hired to handle the big entertainments like state dinners, congressional dinners, diplomatic corps dinners, and the U.S. Supreme Court dinners. The Taft administration ended this practice when, in a cost-saving move, all cooking operations were brought in-house.

As the White House staff, including political appointees and those who maintained the residence, grew in number over succeeding administrations, so did the culinary team. In the main White House kitchen, the team increased from five to eight people, including the first cook (what used to be called the “head cook” and would later be called the “executive chef”), two assistant chefs, a pastry chef, an assistant pastry chef, and three kitchen helpers to perform various kitchen duties.46 Sometimes, the residence’s culinary team grew to nine if a president wanted a private chef designated to cook meals solely for the First Family. For events with a large number of guests, like state dinners, extra chefs were temporarily hired after they passed an extensive security screening.

In such a high-stress environment as the presidential kitchen, it’s no surprise that there always seems to be some interpersonal conflict simmering in the kitchen, but rarely have things boiled over to the point where it has been recorded for posterity. The cause of these disputes generally have involved the respect one feels one deserves, including how one feels about one’s boss, how the boss feels about him or her, the cook’s perceived status with the president, how one’s salary compares with others’, available perquisites (“perks”), and perceived slights based on race, seniority, or gender. Former White House housekeeper Henrietta Nesbitt probably put it best when she wrote, “There is something about working over a hot stove that brings out the best and worst in people.”47 At least some perks could help keep the worst in people at bay.

PERKS

Given their relatively low pay, presidential cooks constantly sought ways to supplement their income. As late as the twentieth century, White House residence staffers, including the kitchen staff, got tips from guests—that is, until First Lady Mamie Eisenhower banned the practice. Not surprisingly, her decision was not well received by the staff. As longtime White House maid Lillian Rogers Parks elaborated, “I know one kitchen worker at the White House who was widowed and supporting two children on about $48 a week before taxes. Losing the tips was hard for her and others like her. Many people think working at the White House is easy, because the work is divided among so many people, and those who work there have soft prestige jobs. Let me tell you that more people have ruined their health under the grueling strain of working at the White House than you would believe.”48 For people living on the margins, as White House staffers often did, the slightest changes in salary and supplemental income made a tremendous difference in their quality of life.

Living in the White House was another perk, but not always a pleasant one. Enslaved cooks were forced to live the majority of their lives in the White House’s basement or attic, where the servant quarters were located. Jesse Holland, author of The Invisibles, helps us grasp the life circumstances of White House slaves:

The African-American slaves most often had rooms in the White House’s basement, referred to as the ground floor today because it opens out onto the South Gardens and the National Mall. These were airy rooms directly beneath the principal floor of the house and on the north and south sides of the long groin-vaulted hall that ran from one end of the house to the other…. These rooms are now used as a Library, China Room, offices, and the formal oval Diplomatic Reception Room. However, this vaulted corridor once accessed a great kitchen forty feet long with large fireplaces at each end, a family kitchen, an oval servants hall, the steward’s quarters, storage and workrooms, and the servant and slave bedrooms. This is where the presidents stashed their slaves, where enslaved Africans ate, slept, socialized and made the best of their imprisonment, all while making the lives of the president and his family as easy as possible so that the affairs of the household could be ignored for the more important affairs of state.49

This “live-in” job requirement continued even for free laborers well into the 1920s. White House housekeeper Elizabeth Jaffray wrote in the 1920s, “All of the servants, with the exception of the white maids, the four [African American] footmen, the firemen and the mechanic and the electrician, lived in the basement of the White House in rooms off the kitchens, and had their meals at a common table.”50 By the time of the FDR administration, African American cooks lived in their own homes off the White House grounds; however, the First Family’s private cook lived in an apartment on the White House’s second or third floor.

Presidential cooks also expected in-house meals. This was particularly important for African Americans on staff because in Jim Crow Washington, there wasn’t a place for them to eat near the White House; they would be refused service. As Jaffray shared in her memoirs, “The White House help are fed much the same as the servants in any other large house. They are given staple vegetables that are served on the President’s own table, but they are not given the same meats or expensive luxuries that necessarily grace the President’s table. It is an invariable rule that on every Thursday chicken be served to the help, and this is always counted a great day by the colored servants.”51 The cooks did have some say in the staff meal menu. White House maid Parks observed,

The cooks ate at their own table in the kitchen. Lunch was our big meal. We ate at twelve o’clock sharp because the family ate at one, and some of us would be needed to serve them. Again, we were sure that aside from state dinners, we servants have the best meals at the White House. Lunch might be roast beef, pork, stewed chicken, or baked ham. On Friday we always had fish. Every day we had hot vegetables and various cakes and ice creams for dessert. [In] summer we have watermelon, which I didn’t eat. I would be accused of being prejudiced against Negroes—a little ethnic joke. One cook was a whiz at spoon bread, and she would frequently make it for us.52

Servants had autonomy over their in-house staff meals for several decades. This created a space for soul food to be the White House’s everyday cuisine—at least for the majority black residence staff. As White House chief usher J. B. West observed, “Because Congress had permitted us to feed the servants since the beginning of the Trumans, [Johnson administration food coordinator] Mary [Kaltman] had $1,000 a month to spend for two meals a day (the servants worked on two shifts) for the thirty-two-person staff. They selected their own menus—not chili or pâté, but plain American Southern-style cooking: fried chicken, pork chops, pigs’ feet, cornbread, black-eyed peas. They ate family style, in the help’s dining room in the lower basement.”53 In some respects, the Executive Mansion operated as a daily “House of Soul,” as the Carters soon discovered after they started living in the White House. When First Lady Betty Ford led her successor Rosalynn Carter on a White House kitchen tour shortly before Jimmy Carter’s inauguration, Mrs. Carter overheard one chef say to another, “You know I really think that we’re going to please the Carters with our Southern cooking—we cook like that every day for the help.”54

Another plum food-related perk was getting the leftovers from the fancier White House meals. In the South, it had been customary for servants to take leftovers home, which was a great way to feed their families. This practice was called “to tote” or “toting”—a phrase derived from a West African word meaning “to carry.” White House workers, however, were denied this privilege, which meant that leftovers had to be consumed on the spot. As White House housekeeper Henrietta Nesbitt explained,

There was a rule that no “tote” be permitted from the White House kitchen. Nothing could be carried out as in other homes in Washington, where the Southern influence showed in letting the help “tote” home the leftover food. Mrs. Roosevelt and I had an understanding that red-letter day ice cream and cake should go to the charitable organizations, but we were overruled in this by an older, established White House tradition that decreed all the leftover specially made cakes, the specially made ice cream, and all the food left on the platters, or on the table, belonged to the help. They had to eat it then and there, since nothing could be carried out.55

Regardless of the amount of perks, the aura of working in the White House remains the best way to recruit and retain presidential employees. Jaffray summed it up best when she noted, “Naturally it is a great honor to any servant to be chief cook at the White House and the position carries considerable prestige with it. In some ways this offsets the disadvantage of the modest pay.”56 That same ethos survives to the present day.

PRESIDENTIAL PETS

As if cooking for and with humans doesn’t cause enough drama, White House cooks have had to deal with presidential pets as well. For example, much like people, FDR’s dogs had menus, meals of meats and vegetables, and they even had to go on periodic diets.57 White House maid Parks relates,

One day Eleanor returned from a trip to find an urgent message waiting for her at the White House to come to see the President in his bedroom. She had been worried about her husband’s health and rushed there. The President looked very concerned. “I’m so glad you’re here,” he said. “I came right away. What’s wrong, Franklin? Have you seen Dr. McIntire?” “No,” he said, “I’ve seen Fala’s vet. He left this special diet and says it’s very important. So will you please give this to the cooks and see that this special medicine is added to it?”58

That’s an interesting twist where the president, with respect to feeding his pets, acted much like a First Lady by keeping a beloved pet on a diet.

A president’s concern for saving money can also get unleashed on pets, not just on humans. Former White House pet trainer Traphes Bryant wrote about his experiences with President Lyndon Johnson and his dogs, Him and Blanco:

I’ll never forget the day LBJ went on an economy kick, petwise. My diary records the date as July 22, 1965. It was the day the President discovered what dog food costs. It had been a day like so many others—the President gave a speech in the Rose Garden and afterwards took Him and Blanco to the south fence where tourists took pictures, shook hands, and formed quite a crowd. But at 9:00 P.M., the President suddenly blew his stack. He had just found out his monthly dog-food bill was $80. “Goddamn it,” he said, “I’d be laughed out of Johnson City if anyone knew what I’m paying to feed a couple of dogs. Christ, a family could live on it.” I told the President I would leave word for the ushers to stop buying hamburger. I did and Usher Carter asked me if the dogs were getting too fat. I said, “No, the President’s pocketbook is getting too lean.”59

Though LBJ’s edicts had been in place for several years, he still sent mixed messages. Bryant’s diary entry for 20 July 1968 reads, “I told the President that I took Yuki [another one of the president’s dogs] to the second floor at 7:30 P.M. every night and Zephyr fed Yuki. But the Prez was still at it. The President said, ‘You and Zephyr make a good salary. You all should put some weight on Yuki.’ … He said maybe I was confused about his wanting to put some weight on Yuki but to take the fat off the beagles.”60 As one can see, when it came to feeding pets to keep both them and the president happy, the cooks often faced a “no-win” scenario.

Once in a blue moon, presidential pets have also interfered with the White House cooks’ dining plans. One morning in March 1934, twelve plates of fried eggs and ham were set out for breakfast in the servants’ dining room. After the cook stepped away to summon the staff to come eat, she returned to find the food missing from all of the plates! After an intense search, the culprit was identified as man’s best friend, or in this case FDR’s best friend—a Llewellin setter named Winks. President Roosevelt had picked up the dog during one of his sojourns to Warm Springs, Georgia. As much as Roosevelt loved that dog, Winks soon disappeared, leaving many to speculate whether or not he left the White House to “spend more time with his family.” This event, along with others, cleared the way for FDR’s more familiar dog, Fala.61

WHITE HOUSE WILDLIFE

This section doesn’t refer to cute deer or fuzzy rabbits grazing on the White House lawn. No, it is about vermin, specifically the critters that one would expect to thrive in a swamp like the one where the White House is situated. During President Martin Van Buren’s time, in the 1830s, the White House kitchen regularly flooded after rainstorms. By the 1890s, the basement was so overrun by insects, rats, and other vermin that one of the African American cooks allegedly killed rats by sitting on them.62 As we’ll see, some First Ladies were so exasperated that they wanted out of the White House altogether. The last known wildlife feed happened during the Lyndon Johnson administration when rats dragged an entire ham off the servants’ dining room table. Only after an atrocious odor emerged months later did someone find a completely gnawed ham bone decaying behind a wall.63 Don’t be alarmed, gentle reader; the current White House is rumored to be quite immaculate.

RACIAL ATTITUDES

Until the civil rights movement in the 1960s, the social status of African Americans in general provides a strong subtext for their role as presidential cooks. As we’ll see in this narrative, whites held a consensus that blacks were created for servitude. Most relevant to our story is the widely held belief that African Americans were “natural born cooks.” Thus, many African Americans became cooks because it was one of the few occupations open to them. Race shaped how blacks, as a perceived servant class, got the job as a cook and influenced the expectations of how they should perform, what they got paid, and what they ate. Disappointingly, in this dysfunctional environment, African Americans internalized racial attitudes so much that it actually affected how they related to one another. Housekeeper Elizabeth Jaffray described how this intraracial dynamic played out in the 1910s and 1920s:

Mrs. Taft and I had an embryo servants’ revolt over the question of where the different servants should have their meals. For many years the servants had settled themselves into very distinct castes. At a special table the four of the five highest colored men of the staff would dine in state—the head steward, the head coachman and two or three others. At a table in the butler’s pantry the dining-room staff would eat what was left over from the President’s own table. Then the laundry-women and scrubwomen would eat at a table by themselves. I immediately ordered that all colored servants, regardless of rank or position, should eat at a single table and at a given hour. The white servants were to have their own table—but there was no other distinction of any kind. There were signs of sharp dissatisfaction, but when I promised dismissal the revolt died.64

In her memoir, Lillian Rogers Parks reported that this trend continued well into the twentieth century: “I must confess that backstairs, there is a little matter of a caste system among the help, based on position and seniority. For a time, we even took our positions at our long dining table according to the system. I sat ‘high.’”65 As one will see, before the 1960s, racial attitudes led many African Americans to the White House kitchen. During and after the 1960s, changing racial attitudes led African Americans not only away from the White House kitchen but also away from professional cooking in general.

Fourth Ingredient: Surprising Elements

Here we have arrived at the fourth and final ingredient in the shaping of presidential foodways: the always surprising elements that just simply extend beyond the president’s control.

U.S. CONGRESS

As noted earlier, during the Truman administration Congress began appropriating money for White House residence staff, food, and entertainment. Congress has frequently used its executive office appropriation as a check on any aristocratic indulgences by the chief executive. At other times, certain members of Congress used the appropriation as a political weapon to either exact revenge or embarrass the president. Such tendencies were on high display when the “Do Nothing Congress”—so named by President Truman—had say-so on his household budget.

In terms of figuring out the finances, the process works like this: Congress appropriates a sum of money that sets the budget parameters for presidential living expenses. When members of the First Family request anything involving food and drink, they are presented a bill for expenses, which is then settled out of their account on a weekly or monthly basis. Entertaining expenses are treated the same way. If the money runs out, the president must find funding from other sources or go back to Congress to ask for more money. The latter would be a public relations nightmare, so presidents have often “found” extra money by “borrowing” cooks from and/or charging expenses to other government agencies or outside parties. Aside from their salaries, this budgeting process has also had a direct impact on how the servants ate, but they were able to carve out some autonomy, as mentioned above. Because Congress is the repository of the people’s power and sentiment, the next element is a fairly potent one.

PUBLIC PERCEPTION

This is the intangible element that worries presidents the most. A consistent narrative that the commander in chief is somehow out of touch with the average citizen can starve a president of the political capital needed to complete his political agenda—and can most certainly hurt his chances of getting reelected. In a democracy where everyone is theoretically equal, being perceived as a snob is a serious offense. The Founding Fathers’ generation was very concerned about not aping the monarchy from which they had successfully rebelled. President Washington, knowing the very powerful precedent that his administration would set, remained very image-conscious during his presidency. But since he and the other Founding Fathers were doing things on the fly, they couldn’t entirely shed the English customs they knew so well.

For European and American elites, French cuisine set the standard for elite dining. Accordingly, the American voting public has long been suspicious of a president who has a French cook, regularly dines on French food, and drinks French wines. For example, Patrick Henry heavily criticized Thomas Jefferson for celebrating Franco-southern fusion food and made him seem unpatriotic for doing so.66 Because of the ease with which one could be charged with snobbery, presidents were frequently on the defensive if they indulged in French cuisine. The public disdain for “Frenchness” created the backdrop for an enduring rivalry: French chefs versus African American chefs. Time and time again, African American chefs and the food they prepared represented what was great in American cooking and supposedly lacking in French cuisine: comfort, informality, ingenuity, and simplicity. Many presidents went out of their way to reassure the public that they loved the homey dishes prepared by their African American cooks, though they rarely dignified these cooks by referring to them by their full names.

Thus, in the public imagination, the culinary competition between American and French food (and, by inference, between American and French cooks) ebbed and flowed with intensity from the time of Jefferson until LBJ. Since President Nixon, the White House has been pushed to be a strong advocate of American food and drink. The main difference of late is that such cooking is not expressly tied to the culinary genius of African American cooks. Sam Houston Johnson, LBJ’s brother, underscored that point when he wrote in his autobiography, “The Kennedys had a fancy French chef who prepared all kinds of unpronounceable dishes, but I’m sure the White House has never had a better cook—or a more independent one—than Zephyr Wright. When she cooked her special roast with Pedernales River chili sauce or fried chicken with spoon bread, you started wishing you had two stomachs.”67

FOOD GIFTS

As mentioned earlier, Americans feel a need to connect with their president. One way they have shown this desire is by sending great amounts of food to the Executive Residence by mail and special delivery. People dispatched food at the slightest impulse—a media report of the president’s favorite food, congratulations for some achievement, wishing a speedy recovery from an illness, lobbying for a certain product, and many times just out of sheer admiration. It was definitely a different time, for past presidents would accept and actually eat these gifts! The U.S. Secret Service would never let that happen today, so the White House table is now provisioned by an array of security-checked food suppliers. If you feel motivated to send the president any food, you should eat it yourself or give it away, because it will be destroyed if it arrives at the White House.

CLIMATE

Cooking in the White House was seasonal employment until air conditioning was installed in the 1950s. Before then, presidents would regularly leave the Executive Residence for a milder climate because it got unbearably hot during the summer. Their travel destination was often an entirely different part of the country or their hometown. There were a few presidents who stayed in the D.C. area but just moved to higher elevations, as President Lincoln did at the Old Soldiers’ Home in northwest D.C. or as Grover Cleveland did in the part of D.C. now known as Cleveland Park. The extended stays away from the Executive Mansion made a lot of sense because the threat of contracting a tropical disease like malaria was very real. After all, the White House kitchen was literally mired underneath a swamp. However, we’ll see that, in some instances, the black cooks were forced to stay and cook for presidential staff, even though the president had left.

All four of the major ingredients in presidential foodways, as I’ve described above, are affected to one degree or another by a final, rather intangible ingredient—I call it the “White House Way.” This means “tradition.” It’s astonishing, but understandable, how really closely presidents have stuck, through the years, to the way George Washington did things while he was in office.

It is the members of the Executive Residence staff—perhaps everyone except the head chef—who serve as the standard bearers for this sort of institutional memory. In short, staff members communicate to an incoming president, “It’s our world, and you’re just a visitor.” Though many a First Family come to the White House with ideas of shaking things up, you would be surprised by how many acquiesce when the staff communicates how things have been done in the past.

In the midst of all of the potential and rich combinations of the ingredients considered above, each providing varying influences on and lending different flavors to a particular presidential administration, I note some trends that have emerged and have affected how African American presidential chefs have done their jobs. The first is a progressive trend, moving through time from slavery to freedom: chefs who were once forced to cook became chefs who could choose their profession. The second trend is how the White House residence operation transitioned, under President Lincoln, from that of a “plantation big house” to that of a wealthy home (Lincoln to Hoover) and, since FDR, became like a hotel. The third and ongoing trend is the intensifying interest of the general public in presidential foodways.

The author (left) in the White House kitchen with presidential kitchen steward Adam Collick, 2015. Author’s photograph.

To tell this diverse story over every presidential administration since George Washington’s, I found it fascinating to shape The President’s Kitchen Cabinet by large themes, exploring the wildly diverse daily duties and responsibilities, concerns, and often very entertaining realities of life for presidential cooks and food service staff. Chapter 2 begins with those responsible for hiring cooks, planning menus, and procuring the food. In chapter 3, we take a closer look at the different classes of cooks, some of whom worked side by side in the White House kitchen before the Civil War: slaves and independent culinary professionals. Chapter 4 chronicles how independent culinary professionals, military personnel, and personal servants shaped the White House food story after Emancipation. We then see, in chapter 5, what happens to food operations when the president travels away from the White House. Chapter 6 closely explores what beverages our presidents have used to wash down their food and, sometimes, their cares. We will finish up with some divining on my part about the future prospects of African American chefs.

Chefs and cooks predominate these pages, but there will be times when non-chefs, airplane crews, butlers, maids, maître d’s, and wait staff join the story. And throughout, marveling at all these personalities and their stories, I strive to answer these essential questions about the presidential cook staff: How did they learn to become a cook? What was their path to cooking for a president? What type of food did they make? Over the course of American history, we will see how African American presidential chefs stood at a unique intersection of class, personal relationship, race, and power. Though they primarily related to the president and First Families through the excellent and comforting food they prepared, we’ll see how these culinary professionals used their positions to illuminate race relations, advocate for civil rights, gain trust as a confidante, become part of the First Family, and sometimes become close friends with the presidents they served.

During the presidency of Andrew Jackson, much ink (positive and negative) was spilled in newspaper editorials over the creation of an informal group of presidential advisers who were often unnamed and unaccountable to the public but highly trusted by the president. Because they reportedly met with the president in the White House kitchen in order to avoid scrutiny, this group of advisers was nicknamed the “Kitchen Cabinet.”68 Speaking of these informal advisers, presidential historian Michael Nelson quoted President Franklin Roosevelt as once saying, “The president ‘needs someone who asks for nothing but to serve [the president].’”69 Many presidents found such individuals among the African Americans who prepared and served their meals. These are their stories.

Recipes

HOW TO ROAST DUCKS

Since the beginning of the presidency, journalists have often failed to record the names of those working in the White House kitchen. I stumbled upon this recipe credited to one of President McKinley’s African American cooks while flipping through a dusty, old cookbook. In Cooking in Old Creole Days, author Celestine Eustis lists several recipes attributed to Katie Seabrook, whom she identifies as “Pres. McKinley’s Colored Cook.” I love this recipe because it shows a complex melding of flavors despite the recipe’s simplicity.

Don’t wash your ducks, but wipe them thoroughly with a clean cloth, inside and outside. Rub the back (inside and outside) with a small piece of onion. Salt and pepper them the same way. Tie them up tightly so the juice does not escape. Rub the breast of each duck with a spoonful of olive oil. Lay in your dripping-pan a slice or two of bacon, one carrot, one leek, two bay leaves, a piece of celery. Place the ducks on this, and let them cook in a moderate oven twenty-five minutes. Put in any dressing you would make for a roast chicken. With all your roast meats put in the bottom of your roast-pan a carrot cut in half, a piece of onion, celery and parsley. The same with boiled meats or fish, to give foundation taste to your food.

ZEPHYR WRIGHT’S POPOVERS

Lynda Bird Johnson Robb, Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson’s elder daughter, graciously reminisced over the phone with me about Zephyr Wright. I asked her about her fondest culinary memories, and these popovers were foremost in her mind. The recipe is credited to Lady Bird Johnson, but it was Zephyr Wright’s cooking of the popovers that brought back the memories.

Makes 6 popovers

1 cup sifted all-purpose flour

1/4 teaspoon salt

2 eggs, beaten

1 cup milk

2 tablespoons shortening, melted (or 1 tablespoon butter and 1 tablespoon shortening, melted)

1. Preheat the oven to 450°F. Generously grease a 6-cup popover pan and place it in the oven while it preheats.

2. Sift the flour and salt into a large bowl.

3. In a separate bowl, combine the eggs, milk, and shortening.

4. Gradually whisk the liquid into the flour mixture.

5. Beat the mixture for one minute or until the batter is smooth.

6. Carefully remove the pan from the oven and fill the cups three-quarters full with the batter.

7. Bake for 20 minutes.

8. Reduce the heat to 350°F and continue baking for an additional 15–20 minutes.

SWEET POTATO CHEESECAKE

Chef Sonya Jones grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, and, when she was ten years old, began helping her mother prepare food sold in the family café. Chef Jones coupled that early culinary education with professional training at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York. She now runs the Sweet Auburn Bread Company in Atlanta, Georgia, not far from where she grew up. In 1999, President Clinton took one bite of Chef Jones’s rich riff on a traditional cheesecake and loved it. Sweet potatoes are the magic ingredient for this cheesecake, and the “crust” is made of thin slices of southern pound cake.

Makes 10–12 servings

For the pound cake crust

1 1/2 cups (3 sticks) butter

1 (8-ounce) package cream cheese

3 cups sugar

6 eggs

2 teaspoons pure vanilla extract

2 teaspoons pure lemon extract

3 cups unbleached all-purpose flour, sifted

For the cheesecake

About 1 pound sweet potatoes

3 (8-ounce) packages cream cheese

1 1/2 cups sugar

3 large eggs

1 cup half-and-half

1 teaspoon pure vanilla extract

1 teaspoon freshly grated nutmeg

Fresh berries to taste

To make the pound cake:

1. Grease and flour a 10-inch tube pan.

2. Using a mixer, cream together the butter, cream cheese, and sugar until the mixture is light and fluffy.

3. Add the eggs one at a time, beating well after each addition.

4. Blend in the vanilla and lemon extracts.

5. With the mixer set to low speed, gradually add the flour and beat just until incorporated.

6. Pour the batter into the prepared pan.

7. Place the pan in a cold oven and turn the temperature to 325°F; bake for 1 1/2 hours, or until a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean.

8. Remove the cake from the oven and allow it to cool in the pan for 10 minutes before turning out onto a wire rack.

9. Cool completely before slicing.

To make the cheesecake:

1. Boil the sweet potatoes for 40–50 minutes, or until tender.

2. Drain the potatoes and run them under cold water to remove the skin.

3. Mash the sweet potatoes in a bowl; you should have 2 cups. Set them aside and allow to cool completely.

4. Preheat the oven to 350°F.

5. Line the bottom of a 9-inch round cake pan with parchment paper and spray the sides of the pan with nonstick cooking spray.

6. Lay flat six or seven 1/4-inch slices of the pound cake in the bottom of the pan (they should not overlap). Set aside.

7. Using a mixer, beat the cream cheese until fluffy, then gradually add the sugar until it is well blended.

8. Add the eggs, one at a time, beating well after each addition.

9. Stir in the mashed sweet potatoes.

10. Add the half-and-half, vanilla, and nutmeg and mix well.

11. Pour the mixture into the prepared pan and bake for 1 hour, or until the center is almost set.

12. Remove from the oven and allow the cheesecake to cool.

13. When the cake is cool, run a knife along the edges and remove it from the pan by inverting it onto a plate.

14. Transfer the cheesecake to a serving platter, crust-side-down, and refrigerate until ready to serve.

15. Garnish with fresh berries.