ry

ry ri ky

ri ky ’

’ sho (Text for Banquets, the Cooking of Fish and Fowl, late eighteenth century)

sho (Text for Banquets, the Cooking of Fish and Fowl, late eighteenth century)Cuisine is like a performance of Noh by the four troupes.

The menu is the program for the performance. The fish, fowl, vegetables, and gourds are the actors.

—Gyoch ry

ry ri ky

ri ky ’

’ sho (Text for Banquets, the Cooking of Fish and Fowl, late eighteenth century)

sho (Text for Banquets, the Cooking of Fish and Fowl, late eighteenth century)

The previous chapter introduced the ironic fact that menu collections (kondatesh ), one of the major categories of published culinary books (ry

), one of the major categories of published culinary books (ry ribon) in the Edo period, included complex meals that most of their readers could not create because of the menus’ expense and complexity and the existence of sumptuary laws that prohibited the use of key ingredients and elaborate methods of serving. Published menus might be thought of as poor substitutes for actual meals, like scripts to plays without actors to perform them, to borrow the metaphor from Text for Banquets cited in the chapter epigraph. But just as a play can be read as literature and enjoyed without being staged, so can a menu. Published menu collections are comparable to the printed books of plays (utaibon) for the masked Noh theater, which provided multiple ways to enjoy Noh beyond acting in a performance. Utaibon, printed in the thousands in the Edo period, were brought by audiences so that they could follow the dialogue at performances and catch all the literary allusions. Amateurs used utaibon as musical scores to study Noh chanting and selections of dances; only professionals could take the stage in full performances. Consequently, many of the thousands of different Noh plays written in the Edo period appear to have been created solely for reading or singing, not for staging as plays.

ribon) in the Edo period, included complex meals that most of their readers could not create because of the menus’ expense and complexity and the existence of sumptuary laws that prohibited the use of key ingredients and elaborate methods of serving. Published menus might be thought of as poor substitutes for actual meals, like scripts to plays without actors to perform them, to borrow the metaphor from Text for Banquets cited in the chapter epigraph. But just as a play can be read as literature and enjoyed without being staged, so can a menu. Published menu collections are comparable to the printed books of plays (utaibon) for the masked Noh theater, which provided multiple ways to enjoy Noh beyond acting in a performance. Utaibon, printed in the thousands in the Edo period, were brought by audiences so that they could follow the dialogue at performances and catch all the literary allusions. Amateurs used utaibon as musical scores to study Noh chanting and selections of dances; only professionals could take the stage in full performances. Consequently, many of the thousands of different Noh plays written in the Edo period appear to have been created solely for reading or singing, not for staging as plays.

Just as printed non libretti allowed new forms of performance and appreciation, printed menu books represent a popularization and transformation of previous culinary discourse, which had conferred special meanings on inedible dishes. Books of menus disseminated information about how h ch

ch nin, the chefs to the samurai and aristocratic elite, utilized inedible dishes like the snacks for the shikisankon and like spiny lobster in the shape of a boat (Ise ebi no funamori) to evoke symbolic meanings and create artistic displays at elite banquets. However, because nearly all the readership of these books could not create these dishes and the elaborate banquets that featured them, printed collections of menus called kondatesh

nin, the chefs to the samurai and aristocratic elite, utilized inedible dishes like the snacks for the shikisankon and like spiny lobster in the shape of a boat (Ise ebi no funamori) to evoke symbolic meanings and create artistic displays at elite banquets. However, because nearly all the readership of these books could not create these dishes and the elaborate banquets that featured them, printed collections of menus called kondatesh became a way to appreciate elegant meals without creating or eating them. Medieval rules for cooking and dining became the guidelines for a literary genre in the Edo period, allowing readers to view not just a few dishes as special, as at an actual banquet, but to conceive of entire banquets as abstract meditations on food. Early menu collections such as Collection of Cooking Menus (Ry

became a way to appreciate elegant meals without creating or eating them. Medieval rules for cooking and dining became the guidelines for a literary genre in the Edo period, allowing readers to view not just a few dishes as special, as at an actual banquet, but to conceive of entire banquets as abstract meditations on food. Early menu collections such as Collection of Cooking Menus (Ry ri kondatesh

ri kondatesh , 1671) and Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony (Cha no yu kondate shinan, 1696) provided readers with the vicarious pleasure of learning about the dining habits of the elite. However, later menu collections, such as Fish Trap of Recipes (Kondatesen, 1760), explored thematic menus with ideas borrowed from the theater and popular culture. All these menu collections included some information about cooking and serving food, but their main contribution to the development of cuisine was their dissemination of ways to fantasize about food in its absence.

, 1671) and Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony (Cha no yu kondate shinan, 1696) provided readers with the vicarious pleasure of learning about the dining habits of the elite. However, later menu collections, such as Fish Trap of Recipes (Kondatesen, 1760), explored thematic menus with ideas borrowed from the theater and popular culture. All these menu collections included some information about cooking and serving food, but their main contribution to the development of cuisine was their dissemination of ways to fantasize about food in its absence.

FIGURE 7. Noh actors crowned with food headdresses, from Text for Banquets: The Cooking of Fish and Fowl (Gy ch

ch ry

ry ri ky

ri ky ’

’ sho). Courtesy of Kaga Bunko, Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library.

sho). Courtesy of Kaga Bunko, Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library.

The first of these published collections, printed in 1671, had the redundant name Collection of Cooking Menus. It was similar to the first published cookbook, Tales of Cookery (Ry ri monogatari), which appeared twenty-eight years earlier. Both of these anonymous books begin with a table of contents, reaffirming the break from the manuscript tradition of h

ri monogatari), which appeared twenty-eight years earlier. Both of these anonymous books begin with a table of contents, reaffirming the break from the manuscript tradition of h ch

ch nin, who eschewed these. The wording of the table of contents for Collection of Cooking Menus, though not as clear as the one for Tales of Cookery, followed a roughly similar format of different types of food preparation.

nin, who eschewed these. The wording of the table of contents for Collection of Cooking Menus, though not as clear as the one for Tales of Cookery, followed a roughly similar format of different types of food preparation.

Cooking Menus for Twelve Months

Plan for Various “Rural Soups”

Plan for Arranging Soups for Snacks [atsumono]

Fish, Fowl, and Vegetable Snacks

The Format for Trays for Weddings

Cooking Menus for Fish, Fowl, and Vegetables

Cooked Salads [aemaze] with Fish, Fowl and Vegetables

Simmered Dishes from Fish, Fowl, and Vegetables

Sashimi from Fish, Fowl, and Vegetables

Blended Dishes from Fish, Fowl, and Vegetables

Plan for Side Dishes Served on Trays [muk zuke]

zuke]

Grilled Things as Snacks

Pairings for Simmered Fowl

Fish for Making Fish Cake1

Despite the title of the book and the wording of some of the headings, only one section contains menus, the one titled “The Format for Trays for Weddings.” The first and sixth sections, titled “Cooking Menus,” focus instead on soups (shiru) and fish and vegetable salads (namasu), the focal dishes on the main tray at a honzen banquet.2

Thus, rather than an actual “collection of menus,” Collection of Cooking Menus is a description of the components for menus in the form of recipes for various dishes found in honzen banquets. The colophon to the manuscript explains the rationale for this:

There are many culinary writings, but this book records culinary pairings on a monthly basis from the first month to the twelfth month [useful] to assemble the parts of a menu and the composition of the dishes in it. There are many varieties of side dishes, grilled dishes, and fish cakes, and this work uses time-honored methods of preparation for these. Since it is a work for publication, it omits serving suggestions for delicacies that are best recommended to people of high station.3

Collection of Cooking Menus provides recipes month by month that can be selected to fit into a menu of one’s own choosing that would be seasonally appropriate and suitable for the status of commoners. The work begins with soups (shiru), whose number would correspond to the size of a menu planned, since each tray for a honzen meal needed one soup. After selecting the soups, readers could choose a number of side dishes, depending on the number they had in mind for each tray. The recipes themselves are simple to the point that it would be better to consider them as serving suggestions, because they offer no advice about methods of preparation. They instead catalogue ingredients that might be served together. For instance, here are the first three soups (shiru) for the second month:

Soup—young sweetfish [koayu], taro buds

Soup—crane, leeks

Soup—crane, mushrooms, raw wasabi, sugina shoots [tsukushi]4

Despite the claims that the book omitted foods for people of high status, crane soup was a high-status dish, one served to daimyo not commoners, who were prohibited by sumptuary rules from eating game fowl at banquets.

The two menus for weddings also betray a bias toward elite manners of serving that were inappropriate to commoners. One wedding banquet begins with the three ceremonial rounds of drinks (shikisankon) featuring the most formal types of foods, including dried chestnuts, abalone, konbu seaweed, dried anchovies (gomame), pickled apricots, green onions, and a simmer (z ni) made from rice cake, dried intestines of sea cucumber (iriko), konbu tied in knots, potato, bonito flakes, and skewered abalone. This version of z

ni) made from rice cake, dried intestines of sea cucumber (iriko), konbu tied in knots, potato, bonito flakes, and skewered abalone. This version of z ni included two skewered dishes, indicating that it was prepared in a style favored by elite warriors and aristocrats.5 Following the shikisankon, there were several snacks listed: herring roe, rolled squid, dried mullet roe (karasumi), a soup (atsumono) prominently featuring a fish fin in the style of ceremonial cuisine (shikish

ni included two skewered dishes, indicating that it was prepared in a style favored by elite warriors and aristocrats.5 Following the shikisankon, there were several snacks listed: herring roe, rolled squid, dried mullet roe (karasumi), a soup (atsumono) prominently featuring a fish fin in the style of ceremonial cuisine (shikish ry

ry ri), and two types of sake: sweet (nurizake) and heated.

ri), and two types of sake: sweet (nurizake) and heated.

The wedding banquet menus also call for more than two trays of food, a style of service denied commoners according to a bakufu edict issued three years before the publication of Collection of Cooking Menus. The first menu consists of three trays, with a soup on each and five, three, and three side dishes, respectively (i.e., a 5–3-3 format). Additional trays of snacks followed. The other menu is for five trays—a style of dining that even daimyo could not utilize—in a format of 4–5-2–3-2. Both of these menus show a profound influence of ceremonial cuisine, the trademark of h ch

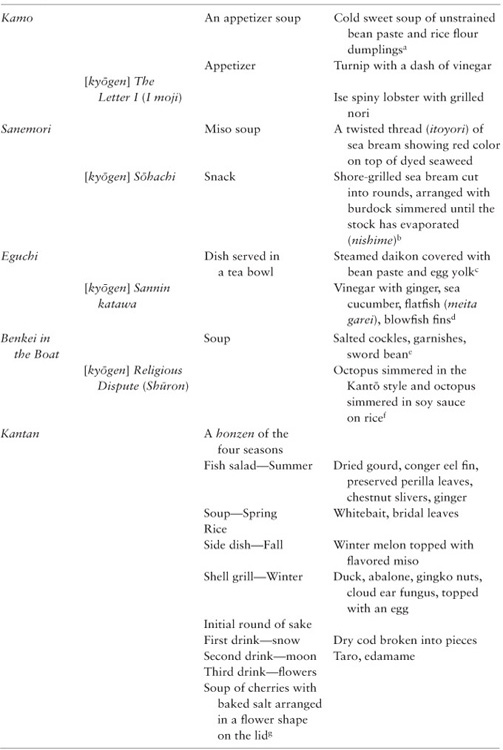

ch nin, as the first menu, consisting of three trays of food, reveals:

nin, as the first menu, consisting of three trays of food, reveals:

Main Tray

Fish salad (namasu) of ginger, fish, daikon, chestnut, and citron

Soup of skewered fish, skewered abalone, burdock, daikon, and shiitake

Grilled dish, sliced

Simmered dish

Pickles

Cooked salad (aemono)

Here only the soup and salad are described, and the type of fish in the namasu is omitted, but the presence of both a namasu and an aemono, which were similar dishes, speaks to the luxury of the meal. The soup also makes use of skewered foods, which indicate high status, as noted earlier. The author likewise specifies only the ingredients of some of the dishes on the second and third trays.

Second Tray

Shell grill (kaiyaki)6

Soup: miso soup with fowl, mushrooms, and wheat gluten

Octopus

Dried squid

Fish cake

Sushi

Third Tray

Snipe wing serving (hamori)

Soup (“anything appropriate and seasonal”)

Spiral shellfish

Spiny lobster served in the shape of a boat (ebi no funamori)

FIGURE 8. Chefs preparing a meal, from Collection of Cooking Menus (Ry ri kondatesh

ri kondatesh ). Courtesy of Iwase Bunko.

). Courtesy of Iwase Bunko.

The second and third trays of this menu show the influence of ceremonial cuisine in the decorative “servings” (mori) of lobster and the snipe prepared with its feathered wings reattached (hamori), two trademark pieces of professional h ch

ch nin (see plate 4). This text does not include directions for the hamori and spiny lobster. Therefore, in order to have them at a banquet, a reader would have to employ a h

nin (see plate 4). This text does not include directions for the hamori and spiny lobster. Therefore, in order to have them at a banquet, a reader would have to employ a h ch

ch nin, something above the status of the readers addressed in the colophon of this work.

nin, something above the status of the readers addressed in the colophon of this work.

That cooking is something for occupational specialists and not for amateur readers is confirmed by the illustrations to Collection of Cooking Menus. The text contains several illustrations of chefs at work and lists their names and duties. The first (figure 8) depicts two chefs wearing formal kimono and trousers with swords tucked in their belts, working at cutting boards. One slices a sea bream and the other a game bird, probably a goose. A third chef, dressed more casually, with his sleeves rolled up, cuts a monstrous catfish hanging from a rope.

Another image (figure 9) shows six more individuals at work: on the top right side, a master of the menu (kondateshi) points to a menu affixed to the wall. Next to him is the master of simmered dishes (nikata no mono). Two pages (kosh ) who carry trays head off to the left while a master of the room (ita no ma no mono) puts the final touches on some additional dishes for the pages to carry. The figure in the bottom right corner is difficult to identify, since the text is obscured, but he is probably the kitchen overseer (daidokoro bugy

) who carry trays head off to the left while a master of the room (ita no ma no mono) puts the final touches on some additional dishes for the pages to carry. The figure in the bottom right corner is difficult to identify, since the text is obscured, but he is probably the kitchen overseer (daidokoro bugy ). All these workers appear to be lower-level samurai, employed presumably by a more powerful upper-level samurai, such as a daimyo, who could afford an extensive cooking staff.

). All these workers appear to be lower-level samurai, employed presumably by a more powerful upper-level samurai, such as a daimyo, who could afford an extensive cooking staff.

FIGURE 9. Kitchen staff, from Collection of Cooking Menus. Courtesy of Iwase Bunko.

Both the wedding menus and the portraits of chefs suggest a realm of cuisine beyond the capacity of nearly all the readers of Collection of Cooking Menus to emulate except in the most basic ways. Readers might create a recipe for a “rural soup” from one of the book’s recipes, but the most elaborate dishes, such as the spiny lobster in the shape of a boat, are not even described in full. Nevertheless, by including these dishes and descriptions of elaborate banquets, the book offers the possibility that food exists in a system of culinary meaning beyond the level of the rural soup. In the absence of the ability to create and eat these dishes in reality, readers could still imagine such banquets and the employment of the people who could prepare them. Collection of Cooking Menus is sketchy on the details of such dreams, but the next text we will consider offers a complete vision of what such a fantasy banquet would look like if one could invite the shogun to dinner.

Published twenty-eight years after Collection of Cooking Menus, the 1696 book Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony continued the trend in presenting elite menus for a wider audience. Despite the title, only the last three volumes in this eight-volume work cover menus for the tea ceremony. The first three feature the most formal cuisine appropriate to a visitation (onari) by a shogun or daimyo to the mansion of another high-ranking warrior or a temple. The type of food served on this occasion falls in the realm of ceremonial cuisine prepared by h ch

ch nin. However, this text is not directed to an audience of “men of the carving knife” like the culinary texts written by h

nin. However, this text is not directed to an audience of “men of the carving knife” like the culinary texts written by h ch

ch nin. Instead, it marks a new way of understanding food preparation and service: as one best realized as a mental activity rather than an actual one. It becomes clear after dipping into the text that the banquet described would have been beyond the financial capabilities of all but the most wealthy and powerful, who would number a few of the richest daimyo.

nin. Instead, it marks a new way of understanding food preparation and service: as one best realized as a mental activity rather than an actual one. It becomes clear after dipping into the text that the banquet described would have been beyond the financial capabilities of all but the most wealthy and powerful, who would number a few of the richest daimyo.

The author of Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony, End Genkan (d. c. 1700), was the most prolific writer about the tea ceremony in the Genroku period (1688–1704). He wrote thirteen of the twenty-five books on tea ceremony published in that period, introducing many topics to readers for the first time.7 His Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony is the first published work on the topic of meals for tea ceremonies, while his Three Teachings about the Tea Ceremony (Cha no yu sendensh

Genkan (d. c. 1700), was the most prolific writer about the tea ceremony in the Genroku period (1688–1704). He wrote thirteen of the twenty-five books on tea ceremony published in that period, introducing many topics to readers for the first time.7 His Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony is the first published work on the topic of meals for tea ceremonies, while his Three Teachings about the Tea Ceremony (Cha no yu sendensh ), published in 1691, was the first work on flower arrangement for tea.8 Despite his achievements, we know little about him, and only a few of his texts are available in modern editions.9 What we do know about End

), published in 1691, was the first work on flower arrangement for tea.8 Despite his achievements, we know little about him, and only a few of his texts are available in modern editions.9 What we do know about End comes from what can be gleaned from this writings.

comes from what can be gleaned from this writings.

End Genkan was a practitioner of the Ensh

Genkan was a practitioner of the Ensh school of tea, which traced its heritage back to Kobori Ensh

school of tea, which traced its heritage back to Kobori Ensh (1579–1649), not Sen no Riky

(1579–1649), not Sen no Riky , the founder of the Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushanok

, the founder of the Omotesenke, Urasenke, and Mushanok ji Senke lineages that dominate tea practice, research, and appreciation today. Accordingly, End

ji Senke lineages that dominate tea practice, research, and appreciation today. Accordingly, End Genkan’s name and contributions are omitted from the so-called bible of the Japanese tea practitioner Sasaki Sanmi, the classic Chado, the Way of Tea: A Japanese Tea Master’s Almanac (Sad

Genkan’s name and contributions are omitted from the so-called bible of the Japanese tea practitioner Sasaki Sanmi, the classic Chado, the Way of Tea: A Japanese Tea Master’s Almanac (Sad saijiki), which details the lore of the Urasenke tradition. There has been only one short chapter on his published works, leaving his unpublished writings on tea and his works on other topics yet to be catalogued and studied by modern scholars.10

saijiki), which details the lore of the Urasenke tradition. There has been only one short chapter on his published works, leaving his unpublished writings on tea and his works on other topics yet to be catalogued and studied by modern scholars.10

Based on what can be learned from his writings, End Genkan was a pediatrician who, in 1656, became a student of tea master Okabe D

Genkan was a pediatrician who, in 1656, became a student of tea master Okabe D ka (1591–1684) in Edo, studying with him for nearly three decades. Okabe was a samurai in the employ of the Maeda daimyo house of Kaga domain (modern Ishikawa prefecture) as an instructor of the gaudy Ensh

ka (1591–1684) in Edo, studying with him for nearly three decades. Okabe was a samurai in the employ of the Maeda daimyo house of Kaga domain (modern Ishikawa prefecture) as an instructor of the gaudy Ensh way of tea, which featured a more flamboyant “daimyo style” over the rustic style (wabicha) expounded by Riky

way of tea, which featured a more flamboyant “daimyo style” over the rustic style (wabicha) expounded by Riky ’s successors. Okabe, who studied directly with Kobori Ensh

’s successors. Okabe, who studied directly with Kobori Ensh , was an extremely long-lived and renowned teacher said to have had more than a thousand students by the time he died, at age ninety-seven.11 After his teacher’s death, End

, was an extremely long-lived and renowned teacher said to have had more than a thousand students by the time he died, at age ninety-seven.11 After his teacher’s death, End moved to Kyoto, where he continued his medical practice, taught the tea ceremony, and wrote about it.12 In the introduction to Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony, he describes himself as “having a body that is old and wasting” and identifies his occupation as “retired” (inshi). Yet Genkan was able to publish several more books on the tea ceremony in the late 1690s. His publications ceased in the first decade of the eighteenth century. Formal Service for the Tea Ceremony (Cha no shin daisu, 1705), is probably the last work printed in his lifetime, according to Yokota Yaemi, who has surveyed all of End

moved to Kyoto, where he continued his medical practice, taught the tea ceremony, and wrote about it.12 In the introduction to Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony, he describes himself as “having a body that is old and wasting” and identifies his occupation as “retired” (inshi). Yet Genkan was able to publish several more books on the tea ceremony in the late 1690s. His publications ceased in the first decade of the eighteenth century. Formal Service for the Tea Ceremony (Cha no shin daisu, 1705), is probably the last work printed in his lifetime, according to Yokota Yaemi, who has surveyed all of End ’s published writings on tea.13

’s published writings on tea.13

End Genkan’s tea writings are distinguished by their detailed attention to all aspects of the tea ceremony. His first published work, Three Teachings about the Tea Ceremony, presents the instructions of Sen no Riky

Genkan’s tea writings are distinguished by their detailed attention to all aspects of the tea ceremony. His first published work, Three Teachings about the Tea Ceremony, presents the instructions of Sen no Riky , Furuta Oribe (1543–1615), and Kobori Ensh

, Furuta Oribe (1543–1615), and Kobori Ensh on topics such as flower arrangements for tea, the arrangement of charcoal for the brazier, interior design, and the instructions for hosting a tea ceremony, including the preparations. The three masters represent the lineage of End

on topics such as flower arrangements for tea, the arrangement of charcoal for the brazier, interior design, and the instructions for hosting a tea ceremony, including the preparations. The three masters represent the lineage of End ’s way of tea, called the Ensh

’s way of tea, called the Ensh school, and the text is an homage to End

school, and the text is an homage to End ’s teacher, Okabe D

’s teacher, Okabe D ka, whose instructions supplied most of the information in three volumes of the work, according to End

ka, whose instructions supplied most of the information in three volumes of the work, according to End , who also added a fourth volume of additional teachings. End

, who also added a fourth volume of additional teachings. End revised the text in 1695, as Illustrations of the Secrets of the Tea Ceremony (Cha no yu hiden zushiki), and the book was published again in 1824, a century after End

revised the text in 1695, as Illustrations of the Secrets of the Tea Ceremony (Cha no yu hiden zushiki), and the book was published again in 1824, a century after End ’s death.

’s death.

End provides a précis to his early tea writings in the introduction to Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony. After humbly describing his Three Teachings about the Tea Ceremony as a “source for jokes,” and saying that “he hoped it would be some help to people,” he explains that he edited Hoarfrost Moon Collection (Shimotsukish

provides a précis to his early tea writings in the introduction to Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony. After humbly describing his Three Teachings about the Tea Ceremony as a “source for jokes,” and saying that “he hoped it would be some help to people,” he explains that he edited Hoarfrost Moon Collection (Shimotsukish ), published in 1692, “to inform people about how to decorate a drawing room [shoin] for a tea ceremony.” He continues: “Since Three Teachings about the Tea Ceremony did not record all the intricacies of the prescribed actions between the host and the guest, I created Transmission on the Style of Tea Ceremony [Cha no yu ry

), published in 1692, “to inform people about how to decorate a drawing room [shoin] for a tea ceremony.” He continues: “Since Three Teachings about the Tea Ceremony did not record all the intricacies of the prescribed actions between the host and the guest, I created Transmission on the Style of Tea Ceremony [Cha no yu ry densho], in which these matters are set down in detail.”14 This six-chapter work published in six volumes in 1694, also known as Transmissions for Our School’s Way of Tea Ceremony (T

densho], in which these matters are set down in detail.”14 This six-chapter work published in six volumes in 1694, also known as Transmissions for Our School’s Way of Tea Ceremony (T ry

ry cha no yu ry

cha no yu ry densho), is a veritable encyclopedia of the Ensh

densho), is a veritable encyclopedia of the Ensh style of tea.

style of tea.

In addition to his thirteen volumes of published tea writings, End published two texts on warrior etiquette and customs: Review of Warriors in Our Land (Honch

published two texts on warrior etiquette and customs: Review of Warriors in Our Land (Honch buke hy

buke hy rin) and Grand Genealogy of a Review of Warriors in Our Land (Honch

rin) and Grand Genealogy of a Review of Warriors in Our Land (Honch buke hy

buke hy rin

rin  kezu). Both appeared in print in 1699. Additionally, he wrote a treatise on marriage, Recorded Treasury on Taking a Bride (Yometori ch

kezu). Both appeared in print in 1699. Additionally, he wrote a treatise on marriage, Recorded Treasury on Taking a Bride (Yometori ch h

h ki), published in 1697. These writings demonstrate a concern for formality and procedure. Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony confirms that the author took great interest in every aspect of ceremonial matters, and that he was eager to convey these minutiae to readers.

ki), published in 1697. These writings demonstrate a concern for formality and procedure. Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony confirms that the author took great interest in every aspect of ceremonial matters, and that he was eager to convey these minutiae to readers.

Yokota Yaemi, the scholar who undertook the first survey of End Genkan’s published writings, has praised him for omitting anecdotal information and discussing only factual matters of the tea ceremony.15 Yet there is also a degree of unreality in End

Genkan’s published writings, has praised him for omitting anecdotal information and discussing only factual matters of the tea ceremony.15 Yet there is also a degree of unreality in End ’s writings. Though participant in a revival of tea traditions that included not only Riky

’s writings. Though participant in a revival of tea traditions that included not only Riky but also the other founders of his Ensh

but also the other founders of his Ensh lineage, End

lineage, End also lived at a time when novelist Ihara Saikaku (1642–93) and playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724) were making their livings by offering dramatizations of daily life for a popular audience, and there are similarities between End

also lived at a time when novelist Ihara Saikaku (1642–93) and playwright Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653–1724) were making their livings by offering dramatizations of daily life for a popular audience, and there are similarities between End ’s writings and those of these other authors.16 Like Chikamatsu and Saikaku, End

’s writings and those of these other authors.16 Like Chikamatsu and Saikaku, End sustained his art through the support of commoners—his tea students and the audience for his published writings.17 Chikamatsu and Saikaku used fiction to dramatize possible outcomes to mundane situations, while End

sustained his art through the support of commoners—his tea students and the audience for his published writings.17 Chikamatsu and Saikaku used fiction to dramatize possible outcomes to mundane situations, while End provided a view of elite warrior life so rich in detail that it seemed real, but at the same time, one so elevated that it too was a departure from the mundane life of his audience of affluent townspeople and lower-level samurai. End

provided a view of elite warrior life so rich in detail that it seemed real, but at the same time, one so elevated that it too was a departure from the mundane life of his audience of affluent townspeople and lower-level samurai. End enumerated the customs of the military elite, and, like playwrights and novelists of the time, he observed the government prohibition against including the actual names of contemporary daimyo and shoguns in his book. Finally, in the same way that Saikaku and Chikamatsu wrote about notorious love affairs or lovers’ suicides secondhand, End

enumerated the customs of the military elite, and, like playwrights and novelists of the time, he observed the government prohibition against including the actual names of contemporary daimyo and shoguns in his book. Finally, in the same way that Saikaku and Chikamatsu wrote about notorious love affairs or lovers’ suicides secondhand, End was not a direct participant in the scenes he described. He explained that he had to rely on informants for all his knowledge about hosting visitations by elite warriors. Taking their various accounts and weaving them seamlessly together, End

was not a direct participant in the scenes he described. He explained that he had to rely on informants for all his knowledge about hosting visitations by elite warriors. Taking their various accounts and weaving them seamlessly together, End presented his imagined version of events for his readers’ pleasure.

presented his imagined version of events for his readers’ pleasure.

In the introduction, End lists his reasons for writing Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony, and he intimates how he obtained his information.

lists his reasons for writing Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony, and he intimates how he obtained his information.

There are many customary instructions in the way of tea, and as for the finer points from long ago, these too are diverse. That being said, there are no writings about the kaiseki meals for the tea ceremony. Consequently, I assembled this text, Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony.

A long time ago there was a text called Riky ’s Hundred [Tea] Ceremonies that was something worldly people carried in their pockets, but this has old practices not suitable for tea meals today. I do not know much about cuisine [ry

’s Hundred [Tea] Ceremonies that was something worldly people carried in their pockets, but this has old practices not suitable for tea meals today. I do not know much about cuisine [ry ri]. However, following my deceased father’s direction, I saw and heard about the tea ceremony from childhood; and each year, thanks to my teacher, I learned anew the cuisine for the ceremony of the opening of the tea jar [kuchi kiri], so that if I were to recall two or three of these [meals] and record them, eventually it would add up to one hundred.18 If [most] people try their hand at these, there would probably be something out of season; and even if they had fish or fowl, the pairing would not be good. They may not notice this because of their ignorance.

ri]. However, following my deceased father’s direction, I saw and heard about the tea ceremony from childhood; and each year, thanks to my teacher, I learned anew the cuisine for the ceremony of the opening of the tea jar [kuchi kiri], so that if I were to recall two or three of these [meals] and record them, eventually it would add up to one hundred.18 If [most] people try their hand at these, there would probably be something out of season; and even if they had fish or fowl, the pairing would not be good. They may not notice this because of their ignorance.

Despite his humble protests that he did not know much about cuisine, End Genkan claimed that he knew more than most people because of his special experiences, such as attending more than a hundred celebrations of the “opening of the tea jar” (kuchi kiri), one of the most important events in the tea ceremony calendar. Called the “New Year for tea practitioners,” the “opening of the tea jar” in the tenth month of the year, when it was celebrated in the Edo period, marked the first serving of the year’s harvested thick tea and the transition to a winter mode of tea service using a sunken hearth (ro). The fact that End

Genkan claimed that he knew more than most people because of his special experiences, such as attending more than a hundred celebrations of the “opening of the tea jar” (kuchi kiri), one of the most important events in the tea ceremony calendar. Called the “New Year for tea practitioners,” the “opening of the tea jar” in the tenth month of the year, when it was celebrated in the Edo period, marked the first serving of the year’s harvested thick tea and the transition to a winter mode of tea service using a sunken hearth (ro). The fact that End Genkan claims to have attended one hundred such ceremonies, despite the fact that these events occurred only once a year, speaks to his claims to expertise in the formalities of the way of tea. End

Genkan claims to have attended one hundred such ceremonies, despite the fact that these events occurred only once a year, speaks to his claims to expertise in the formalities of the way of tea. End casts himself as a narrator who promises to guide readers through the world of tea cuisine, the closed preserve of specialists and the elite, and one fraught with pitfalls even for those who could afford to serve fish and fowl but were ignorant of the proper way to do so.

casts himself as a narrator who promises to guide readers through the world of tea cuisine, the closed preserve of specialists and the elite, and one fraught with pitfalls even for those who could afford to serve fish and fowl but were ignorant of the proper way to do so.

End ’s personal recollections of New Year’s tea ceremonies contrast his presentation of himself in the remainder of the introduction as an outsider to meals served during formal visitations by a shogun or daimyo. Since only the shogun or daimyo made such visitations, either one is the possible intended guest in End

’s personal recollections of New Year’s tea ceremonies contrast his presentation of himself in the remainder of the introduction as an outsider to meals served during formal visitations by a shogun or daimyo. Since only the shogun or daimyo made such visitations, either one is the possible intended guest in End ’s description, and he left that person’s identify for readers to decide. This lack of specificity may also reflect a deficit of knowledge. End

’s description, and he left that person’s identify for readers to decide. This lack of specificity may also reflect a deficit of knowledge. End explains that he had to learn about visitations from others since his own rank prohibited him from witnessing them firsthand.

explains that he had to learn about visitations from others since his own rank prohibited him from witnessing them firsthand.

When it comes to the matter of a lord’s visit to a grand room [daishoin], which is the formal reception room decorated in the shoin style, I myself have always been a person of low status, therefore I do not know much about matters pertaining to people of high rank. I listened to what my teacher said, and visited people who were accomplished in our school, and although my understanding about this is insufficient, I relied on my brush to record it all, completely, in every detail, so that it might take us all one step forward [in our art].19

Constructing a narrative pieced together from the words of his teacher and other informants, End is necessarily presenting an idealized version of events based on other people’s accounts. Inviting his readers to join him in this meditation, he allows them the opportunity to observe something they ordinarily could not see and, perhaps, to go so far as to envision themselves in the role of a powerful and wealthy lord who would play host to another one.

is necessarily presenting an idealized version of events based on other people’s accounts. Inviting his readers to join him in this meditation, he allows them the opportunity to observe something they ordinarily could not see and, perhaps, to go so far as to envision themselves in the role of a powerful and wealthy lord who would play host to another one.

End ’s text promises in eight volumes something special, not simply menus for the tea ceremony but also a description, based on secondhand knowledge, of how to serve a meal to a shogun or a daimyo paying a formal visit to another person of high rank. This he provides in exhausting detail in the first three volumes of his book. Volumes 4 through 6 present more conventional but still glamorous menus for the tea ceremony arranged month by month, with some notations about food preparation. Volume 7 offers vegetarian (sh

’s text promises in eight volumes something special, not simply menus for the tea ceremony but also a description, based on secondhand knowledge, of how to serve a meal to a shogun or a daimyo paying a formal visit to another person of high rank. This he provides in exhausting detail in the first three volumes of his book. Volumes 4 through 6 present more conventional but still glamorous menus for the tea ceremony arranged month by month, with some notations about food preparation. Volume 7 offers vegetarian (sh jin) tea menus, including a vegetarian version of the meal for the lord’s visitation. The eighth volume covers other matters of formal banqueting, including the three ceremonial rounds of drinking (shikisankon) and more general pronouncements about tea cuisine, such as proper dining behavior at tea meals, further recipes, and tea and dining utensils.

jin) tea menus, including a vegetarian version of the meal for the lord’s visitation. The eighth volume covers other matters of formal banqueting, including the three ceremonial rounds of drinking (shikisankon) and more general pronouncements about tea cuisine, such as proper dining behavior at tea meals, further recipes, and tea and dining utensils.

Before I examine End Genkan’s description of hosting a visitation (onari), some background information about these formal visits by shogun and daimyo is warranted. The custom of visitations began in the Muromachi period as an annual or irregular visit by a shogun to one of his chief retainers or by one powerful warlord to another.20 The shogun’s visitations began in the early afternoon around 2:30 and ended in midmorning the next day around 10:00.21 The host greeted his guest in a private room, where the three ceremonial rounds of drinking (shikisankon) occurred. Then the host and the shogun exchanged gifts, such as swords and saddles.22 Afterward, the group retired to a larger “public” room (kaisho) for a banquet in the honzen style. On these occasions the most formal types of ceremonial cuisine (shikish

Genkan’s description of hosting a visitation (onari), some background information about these formal visits by shogun and daimyo is warranted. The custom of visitations began in the Muromachi period as an annual or irregular visit by a shogun to one of his chief retainers or by one powerful warlord to another.20 The shogun’s visitations began in the early afternoon around 2:30 and ended in midmorning the next day around 10:00.21 The host greeted his guest in a private room, where the three ceremonial rounds of drinking (shikisankon) occurred. Then the host and the shogun exchanged gifts, such as swords and saddles.22 Afterward, the group retired to a larger “public” room (kaisho) for a banquet in the honzen style. On these occasions the most formal types of ceremonial cuisine (shikish ry

ry ri) was served to the main guest, with other warriors in attendance receiving less lavish servings according to their rank. Further rounds of drinking followed the meal, and more presents were exchanged, such as swords, Chinese paintings, horses, imported artifacts, and robes. After more drinking, the shogun retired to a separate room for a rest and perhaps a bowl of tea. Later in the evening, he returned to the main room to enjoy Noh theater and other entertainments, accompanied by even more drinking and refreshments.23

ri) was served to the main guest, with other warriors in attendance receiving less lavish servings according to their rank. Further rounds of drinking followed the meal, and more presents were exchanged, such as swords, Chinese paintings, horses, imported artifacts, and robes. After more drinking, the shogun retired to a separate room for a rest and perhaps a bowl of tea. Later in the evening, he returned to the main room to enjoy Noh theater and other entertainments, accompanied by even more drinking and refreshments.23

Onari were expressions of shogunal authority and power, as well as occasions for the shogun to reaffirm his personal relationship with key vassals. Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimochi (1386–1428) conducted an average of sixty such visits yearly to the homes of retainers and to prominent temples. In the year 1440 alone, the sixth shogun, Ashikaga Yoshinori (1394–1441), made 130 onari. Some onari occurred annually, others were by invitation. By custom, the Ashikaga shogun visited the home of the deputy shogun (kanrei) on the second day of the New Year.24

The practice of shogunal visits continued in the Edo period. The second and third shoguns, Tokugawa Hidetada and Tokugawa Iemitsu, averaged four visitations a year to powerful daimyo. Edo-period visitations were simplified compared to their Muromachi forerunners. The opening events began in the early morning around 6:00 and usually took place in tea-ceremony rooms (sukiya) with a tea ceremony and simplified meal. Following that, a shikisankon was performed in a larger room, in the Muromachi-period custom.25

Visitations allowed the shogun and daimyo with sufficient status and wealth to demonstrate authority and confirm hierarchical relationships through ritual. Sumptuary legislation and cost prevented anyone else from even attempting such political exercises. For example, End Genkan’s description of a meal for a lord’s visitation, analyzed in detail below, included three trays with a soup each and nine side dishes in the 3-2-4 format.26 Even if a commoner could manage to put together the components for the extensive meal and consume it in secret, staging a visitation required an appropriate architectural setting, as End

Genkan’s description of a meal for a lord’s visitation, analyzed in detail below, included three trays with a soup each and nine side dishes in the 3-2-4 format.26 Even if a commoner could manage to put together the components for the extensive meal and consume it in secret, staging a visitation required an appropriate architectural setting, as End indicated, which would have been much more expensive and impossible to conceal from the authorities. For a visit by Shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (1646–1709) in 1698, the daimyo of Owari domain rebuilt his mansion in Edo at the cost of two hundred thousand ry

indicated, which would have been much more expensive and impossible to conceal from the authorities. For a visit by Shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (1646–1709) in 1698, the daimyo of Owari domain rebuilt his mansion in Edo at the cost of two hundred thousand ry , an amount more than the domain’s total annual expenditures for a typical year.27

, an amount more than the domain’s total annual expenditures for a typical year.27

Since a formal visitation might necessitate constructing new buildings in preparation, Guide to Meals for the Tea Ceremony begins its descriptions of visitations by providing directions for creating the appropriate building, called a grand study (daishoin), where the initial proceedings for the visitation would take place.28 Construction of such a room and the building to house it would have to begin “two to three years before hosting a visitation by a lord” in order to be completed in time, according to End Genkan.29 He admitted that the size of such a room would depend on the wealth and status of its owner, and that carpenters would know the particulars of its construction.

Genkan.29 He admitted that the size of such a room would depend on the wealth and status of its owner, and that carpenters would know the particulars of its construction.

After sketching out the architectural details, End described the appropriate decorations for the grand study, which featured a series of alcoves, each requiring different displays. One alcove pictured in his illustrations shows a hanging scroll with a painting of a large bird in the background; an incense burner in the shape of a deer sits on a small table in the foreground. In another alcove a box for writing papers, a large container for a seal, and a mouth organ (sh

described the appropriate decorations for the grand study, which featured a series of alcoves, each requiring different displays. One alcove pictured in his illustrations shows a hanging scroll with a painting of a large bird in the background; an incense burner in the shape of a deer sits on a small table in the foreground. In another alcove a box for writing papers, a large container for a seal, and a mouth organ (sh ) rest on a row of high shelves; a small statue of what appears to be an Iberian merchant sits on a lower shelf or the floor in front. Other illustrations show the appropriate flower arrangements, either standing alone or complementing small paintings, for these alcoves. In one of these a large basket of wisteria hangs suspended above a miniature garden of stones on a platter.

) rest on a row of high shelves; a small statue of what appears to be an Iberian merchant sits on a lower shelf or the floor in front. Other illustrations show the appropriate flower arrangements, either standing alone or complementing small paintings, for these alcoves. In one of these a large basket of wisteria hangs suspended above a miniature garden of stones on a platter.

End clarifies the types of flower arrangements for these occasions.

clarifies the types of flower arrangements for these occasions.

The previous illustrations of large floral settings are quite different from the ones typical of formal flower arrangements [rikka]. The form here is for tea flowers [chabana], so that is the method I am conveying here, not the one for formal flower arrangements. The public might think that it has to be formal flower arrangements for occasions like a lord’s visit, but employing arrangements such as these is formal enough. Consequently, I have presented in illustrations large floral settings of various types for the edification of ordinary folk.30

End ’s comments regarding the history of flower arrangement reveal a transition away from the stiff rikka style favored in the medieval period to the more whimsical and simple style of tea flowers, but his rhetoric also deserves close attention. He writes as if members of the public (sejin) could actually build such a grand study and fill it with flowers and other delicate furnishings. He allows “ordinary folk” this fantasy while at the same time confirming his role as authority in these matters. Readers might go so far as to reproduce one of End

’s comments regarding the history of flower arrangement reveal a transition away from the stiff rikka style favored in the medieval period to the more whimsical and simple style of tea flowers, but his rhetoric also deserves close attention. He writes as if members of the public (sejin) could actually build such a grand study and fill it with flowers and other delicate furnishings. He allows “ordinary folk” this fantasy while at the same time confirming his role as authority in these matters. Readers might go so far as to reproduce one of End ’s suggested flower arrangements as a memento of a world otherwise forbidden to them, but that would be only a fraction of the setting required. End

’s suggested flower arrangements as a memento of a world otherwise forbidden to them, but that would be only a fraction of the setting required. End ’s illustrations complete the fantastic scene by including illustrations of the formal doorway for a closet in the room and illustrations showing how decorations for the tea implements should be arranged.

’s illustrations complete the fantastic scene by including illustrations of the formal doorway for a closet in the room and illustrations showing how decorations for the tea implements should be arranged.

After setting the stage and putting the props in place, End proceeds to arrange for the lord’s visit.

proceeds to arrange for the lord’s visit.

After a grand study has been constructed, the host who desires a lord to visit will, two or three months or even half a year in advance, pay a visit to the lord’s subordinates and request the honor of the lord’s presence on such and such a date. The subordinates present this request to the lord. Following that, the host is summoned to the lord’s presence and the date of the visit is proclaimed, as well as a command that the preparations for the visit be as simple as possible. The host thanks the lord graciously, saying, “I could not ask for anything better,” and then he departs. Then the host ought to pay a visit to the lord’s subordinates and senior retainers in order to express his thanks.31

Like a playwright, here and in other places, End provides snippets of dialogue for his scenes, all the better for his readers to imagine them occurring. He allows the lord to adopt a moralistic tone by requesting his future host to exercise some frugality in making his plans. The host eagerly accepts both the moral and the financial responsibility for the enormous expense related to the event.

provides snippets of dialogue for his scenes, all the better for his readers to imagine them occurring. He allows the lord to adopt a moralistic tone by requesting his future host to exercise some frugality in making his plans. The host eagerly accepts both the moral and the financial responsibility for the enormous expense related to the event.

Next End advises readers on the steps needed to prepare for the visitation. These would begin with finalizing the decorations in the grand study according to his previous directions, then determining the menu and the events that would proceed and follow the meal. He instructs readers to create a to-do list and copy it out two or three times before assigning servants to the appropriate tasks and drilling them until they become accustomed to accomplishing them well.32

advises readers on the steps needed to prepare for the visitation. These would begin with finalizing the decorations in the grand study according to his previous directions, then determining the menu and the events that would proceed and follow the meal. He instructs readers to create a to-do list and copy it out two or three times before assigning servants to the appropriate tasks and drilling them until they become accustomed to accomplishing them well.32

Of all the preparations, deciding on the menu appears to have been the most complicated and serious one, even though it was only a meal for one. End does not discuss what anyone else present at the visitation should eat. Others, such as the host and the lord’s retainers, might consume something, but like the readers, they were to be spectators of the lord’s gastronomic pleasures, and their likes and dislikes and menu did not merit much attention. The process of creating the menu for the lordly guest proceeds through several steps and involves a range of people from the host’s and lord’s staffs. Initially, “the menu should be decided by politely discussing the foods with the masters of the lord’s chambers [niwaban], his inspectors, and by summoning chefs [ry

does not discuss what anyone else present at the visitation should eat. Others, such as the host and the lord’s retainers, might consume something, but like the readers, they were to be spectators of the lord’s gastronomic pleasures, and their likes and dislikes and menu did not merit much attention. The process of creating the menu for the lordly guest proceeds through several steps and involves a range of people from the host’s and lord’s staffs. Initially, “the menu should be decided by politely discussing the foods with the masters of the lord’s chambers [niwaban], his inspectors, and by summoning chefs [ry rinin].” Then, End

rinin].” Then, End indicates, one should

indicates, one should

call the masters of affairs [det ban] from the castle and show them the menu that was decided. Ask about the lord’s likes and dislikes and revise the menu accordingly. Since using even a little of something that the lord dislikes might make him ill, it is best to make careful inquiries well in advance. Moreover, asking the masters of affairs about the menu will mean that the topic will come up in the lord’s presence. One will learn the lord’s preferences that way. Accordingly, if one inquires well in advance, one will be able to conform to the lord’s tastes and will avoid any illness caused by the foods.33

ban] from the castle and show them the menu that was decided. Ask about the lord’s likes and dislikes and revise the menu accordingly. Since using even a little of something that the lord dislikes might make him ill, it is best to make careful inquiries well in advance. Moreover, asking the masters of affairs about the menu will mean that the topic will come up in the lord’s presence. One will learn the lord’s preferences that way. Accordingly, if one inquires well in advance, one will be able to conform to the lord’s tastes and will avoid any illness caused by the foods.33

However, in a manner this serious, outside experts must be consulted.

From the time the menu is determined, one should summon one or two medical doctors associated with the lord and consult with them about the menu. Carefully examine the good and bad points of the food combinations. Also, let those affiliated with the lord know about the menu, and ask them to carefully investigate these matters for some time. This way, doctors will also take great care in the matter, and the menu will be something that is well conceived.34

End was himself a doctor, and in volume 8 of the same book he provides a list of foods that should not be eaten together. He observes that eating ripe persimmon after consuming crab frequently causes food poisoning, and that devil’s tongue (kon’yaku) should not be served with spiral shellfish.35 Since any meal for a daimyo or shogun would contain a multitude of dishes, his listings of problematic food combinations was no substitute for the advice of specialists needed to detect potential problems with a menu. End

was himself a doctor, and in volume 8 of the same book he provides a list of foods that should not be eaten together. He observes that eating ripe persimmon after consuming crab frequently causes food poisoning, and that devil’s tongue (kon’yaku) should not be served with spiral shellfish.35 Since any meal for a daimyo or shogun would contain a multitude of dishes, his listings of problematic food combinations was no substitute for the advice of specialists needed to detect potential problems with a menu. End ’s caution reveals the anxiety inherent in preparing a meal for a daimyo or shogun. He omits mention of the possible punishments awaiting someone who might even accidentally sicken a daimyo or shogun, but his worries about food poisoning and unhealthy food combinations add a dose of realism and a touch of dramatic tension to End

’s caution reveals the anxiety inherent in preparing a meal for a daimyo or shogun. He omits mention of the possible punishments awaiting someone who might even accidentally sicken a daimyo or shogun, but his worries about food poisoning and unhealthy food combinations add a dose of realism and a touch of dramatic tension to End ’s account.

’s account.

Not sparing any expense, End stipulates that all the trays for serving the lord his food will have to be newly lacquered. New rice bowls must be ordered for the lord’s use. The lacquer bowls should bear the lord’s crest. For readers curious about the exact dimensions and designs of these, End

stipulates that all the trays for serving the lord his food will have to be newly lacquered. New rice bowls must be ordered for the lord’s use. The lacquer bowls should bear the lord’s crest. For readers curious about the exact dimensions and designs of these, End provides his characteristically exacting descriptions.

provides his characteristically exacting descriptions.

Having discussed all the preparations that would go into the menu, the expert advice to be sought, the arrangements to be made with samurai officials, the orders to be placed with craftsmen, and the food combinations to be medically analyzed, End finally presents his “formal menu for the visit by a lord” (onari no seishiki kondate), which would take place on the twenty-sixth day of the eighth month. Though End

finally presents his “formal menu for the visit by a lord” (onari no seishiki kondate), which would take place on the twenty-sixth day of the eighth month. Though End provided some notations about serving vessels, he was not consistent in doing so; and the following description omits these and focuses on the foods alone.36

provided some notations about serving vessels, he was not consistent in doing so; and the following description omits these and focuses on the foods alone.36

Main Tray

Fish salad (namasu)

sea bream, whiting, turbot, chestnuts, ginger, kumquat, udo shoots, peeled tangerine37

Soup—a stew using dark miso

daikon, taro, dried sea cucumber on a skewer, pressed cut meat of fish or fowl, small shiitake mushrooms

Pickles38

pickled Moriguchi daikon

pickles in the Nara style

tiny eggplants

Salad (aemono) of seafood and vegetables:

finely cut abalone on a stick, dried gourd, hulled chestnuts, miso with sesame and black pepper

Rice

The fish salad (namasu) exemplifies the luxury of the foods served in this menu. It is a lavish version of dish typically found on the first tray of a honzen meal. Here it contains three varieties of seafood accented with ginger, tangerine peels, and other ingredients.

Typical recipes for namasu such as those found in Assembly of Standard Cookery Writings (G rui nichiy

rui nichiy ry

ry rish

rish ), published six years before End

), published six years before End ’s text, call for only one fish and use only lower-quality fish such as carp, sardines, and crucian carp.39 The salad (aemono) is similar to the namasu, and the presence of both dishes on a single tray indicates luxury. Similarly, End

’s text, call for only one fish and use only lower-quality fish such as carp, sardines, and crucian carp.39 The salad (aemono) is similar to the namasu, and the presence of both dishes on a single tray indicates luxury. Similarly, End ’s soup contains dried sea cucumber on a skewer, a dish restricted by sumptuary legislation to high-ranking samurai such as daimyo.40 Though the Nara-style pickles and the Moriguchi daikon might be produced locally, creating the other dishes in Kyoto, where End

’s soup contains dried sea cucumber on a skewer, a dish restricted by sumptuary legislation to high-ranking samurai such as daimyo.40 Though the Nara-style pickles and the Moriguchi daikon might be produced locally, creating the other dishes in Kyoto, where End Genkan lived, would require that the seafood be transported over a considerable distance. Consequently, even assembling the ingredients for the first tray would have been a considerable undertaking in End

Genkan lived, would require that the seafood be transported over a considerable distance. Consequently, even assembling the ingredients for the first tray would have been a considerable undertaking in End ’s time, but the banquet to be set before the lord was even more complex since it included two more trays.

’s time, but the banquet to be set before the lord was even more complex since it included two more trays.

Second Tray

Simmered dish

whitebait mixed with scrambled egg and citron

Soup—crane in a light miso broth:

sinews from a crane’s leg, burdock, salted matsutake mushrooms, eggplant, shimeji mushrooms, leafy green vegetables (kona)

Grilled dish—salmon with wasabi and sauce

Small dishes of parched salt and cracked Japanese pepper (sansh )

)

Third Tray41

Sashimi—carp with roe, shredded and also cut into flat sections

Soup—grated yam with boiled sea cucumber marinated in sake with green nori

A large carp, broiled without seasoning, served with a sauce

Broiled game bird—duck on round slices of tangerine with water dropwart (seri)

Crane, served in a soup on the second tray, was a focal point in elite warrior banquets. It is of course no longer served in Japan, but matsutake mushrooms remain an expensive autumn delicacy. One modern commentator called eating them “one of the great experiences of life.”42 Matsutake are a delicacy because they cannot be cultivated and have to be gathered in the wild. Here, these foods compete with other dishes for the diner’s attention. Grilled salmon, broiled duck, simmered whitebait, and sea cucumber soup all provide delectable distractions.

End gives directions in volume 3 for serving the meal to the lord. He indicates that the lord will take the precaution of bringing his own food tasters to sample the dishes before he eats, but that it will be the personal honor of the host to serve the lord. In this procedure, the host first inquires of the lord’s men if the lord would like to eat, saying, “If it is convenient for you, I would like to present the banquet trays.” The vassals convey this message to the lord, who responds, “That would be fine if it is convenient for you,” at which point the host appears before the lord.

gives directions in volume 3 for serving the meal to the lord. He indicates that the lord will take the precaution of bringing his own food tasters to sample the dishes before he eats, but that it will be the personal honor of the host to serve the lord. In this procedure, the host first inquires of the lord’s men if the lord would like to eat, saying, “If it is convenient for you, I would like to present the banquet trays.” The vassals convey this message to the lord, who responds, “That would be fine if it is convenient for you,” at which point the host appears before the lord.

The host serves the main tray to the lord, placing it in front of him, and then stands and retreats.

The host’s oldest son brings out the second tray and places it on the side of the main tray with the soup on it.

The second son brings out the third tray and places it on the side of the main tray with the rice on it.

Servants bring out the trays for the lord’s followers.

Servants bring out the grilled and simmered dishes. Generally once the trays are served, the host and his sons do not appear needlessly in front of the lord.43

End goes into great detail about how the trays should be carried, where they are to be placed, and what to do if the lord kindly offers something tasty from his own plate to the host. According to the above description and custom, the second tray goes on the right side of the main tray, and the third tray on the left, from the perspective of the guest.

goes into great detail about how the trays should be carried, where they are to be placed, and what to do if the lord kindly offers something tasty from his own plate to the host. According to the above description and custom, the second tray goes on the right side of the main tray, and the third tray on the left, from the perspective of the guest.

End advises readers on the polite way to behave in front of a lord. “It is rude to talk while eating something or to burst out in a loud voice. Of course, when eating a large amount [of food], no one can say anything.” Presumably it was a bad idea to eat a large amount of food in the first place. However, there were far worse things to avoid: “Using a chopstick as a toothbrush is completely out of bounds.” And “making loud munching sounds when chewing on a bone from a grilled dish or something else is atrocious.”44

advises readers on the polite way to behave in front of a lord. “It is rude to talk while eating something or to burst out in a loud voice. Of course, when eating a large amount [of food], no one can say anything.” Presumably it was a bad idea to eat a large amount of food in the first place. However, there were far worse things to avoid: “Using a chopstick as a toothbrush is completely out of bounds.” And “making loud munching sounds when chewing on a bone from a grilled dish or something else is atrocious.”44

End ’s banquet hardly ends with three trays of food. Following the custom of honzen meals, no sake would be served until the foods on the trays had been eaten or at least been given some of the guest’s attention. The guest might also want to save some room for the delicacies in the form of snacks (sakana) and snack soups (atsumono) that accompanied the “interval sake” that followed the honzen banquet. These additional soups and snacks were served on individual small trays (oshiki). The snacks End

’s banquet hardly ends with three trays of food. Following the custom of honzen meals, no sake would be served until the foods on the trays had been eaten or at least been given some of the guest’s attention. The guest might also want to save some room for the delicacies in the form of snacks (sakana) and snack soups (atsumono) that accompanied the “interval sake” that followed the honzen banquet. These additional soups and snacks were served on individual small trays (oshiki). The snacks End planned to serve with sake for the lord’s visit were quite elaborate.

planned to serve with sake for the lord’s visit were quite elaborate.

Soup—oysters, finely ground pepper

Side dishes (sakana)

Shelled crab with tofu lees

Abalone covered with Japanese pepper-miso sauce

Soup of dark miso with small grilled crucian carp

Dried mullet roe

Grilled pheasant with salt and Japanese pepper

Soup of water snail (tanishi), mioga buds, light soy sauce45

Fish cake

Fish salad of clam with Japanese mustard (karashi)

Soup of dried sardines and freshwater suizenji nori in light soy sauce46

Dried squid tied together and artfully cut (makizurume)

This was quite an assortment of snacks, but the menu contained yet another stage of eating, namely, sweets to accompany thick tea.

Tea Sweets

Quail rice cakes (uzura mochi)

Gingko nuts cured in spices (nishime)

Peeled chestnuts (mizuguri)

Tea—“recent past” (hatsu mukashi) variety [served in a] tenmoku bowl with a stand

Accompanying Sweets

Persimmons from Yamato province

Large pears

The tea sweets continue the overall message of opulence of the banquet. The “recent past” variety of powdered tea named here was produced in Uji, south of Kyoto, and it was preferred by the Tokugawa shoguns who gave it that poetic name (mei).47 The use of a Chinese-style (tenmoku) tea bowl with a stand indicates a high level of formality appropriate to the exalted rank of the guest. The quail rice cakes were made from glutinous rice mixed with water that was first steamed, then pounded in a mortar, and then formed around a filling of adzuki bean paste; the shape of the rice cake suggested the appearance of a quail.48 The peeled chestnuts soaked in salt water called mizuguri were restricted to high-ranking samurai such as daimyo.49 Though the pears were just coming into season, the Yamato persimmons, also called “imperial palace persimmons,” would have been early for the twenty-sixth day of the eighth month, when End set his menu. Moreover, eating these at that time would have been illegal for commoners, following bakufu sumptuary legislation promulgated in 1686 (a decade before End

set his menu. Moreover, eating these at that time would have been illegal for commoners, following bakufu sumptuary legislation promulgated in 1686 (a decade before End published his book) and stipulating that these persimmons could be purchased only after the ninth month.50 (Of course, such restrictions did not apply to elite samurai or to the imaginary world of culinary books.) Despite their rarity, the tea sweets were more savory than sweet and would probably disappoint modern readers craving a rich dessert. Nevertheless, by late-seventeenth-century standards these were ostentatious.

published his book) and stipulating that these persimmons could be purchased only after the ninth month.50 (Of course, such restrictions did not apply to elite samurai or to the imaginary world of culinary books.) Despite their rarity, the tea sweets were more savory than sweet and would probably disappoint modern readers craving a rich dessert. Nevertheless, by late-seventeenth-century standards these were ostentatious.

Even though End Genkan warned his readers in his introduction to avoid foods that were out of season, his menu demonstrates a creative use of seasonality in several places, meaning that he chose foods without regard to whether they were available or at their supposed peak in flavor. Today, Japanese chefs and tea masters pride themselves on expressing seasonality with their foods, but this turns out to be a recent idea. Seasonality may not have been a concern until it became possible to eat foods out of season, as is possible with technology like modern transportation and refrigeration. According to scholar Kumakura Isao, seasonality, while fundamental to modern tea aesthetics, was not so rigidly considered in tea writings before the nineteenth century. Edo-period tea texts, for example, reference foods and flowers that would be out of season in the months they were suggested for use.51 Culinary historian Nakayama Keiko has identified a disjunction in End

Genkan warned his readers in his introduction to avoid foods that were out of season, his menu demonstrates a creative use of seasonality in several places, meaning that he chose foods without regard to whether they were available or at their supposed peak in flavor. Today, Japanese chefs and tea masters pride themselves on expressing seasonality with their foods, but this turns out to be a recent idea. Seasonality may not have been a concern until it became possible to eat foods out of season, as is possible with technology like modern transportation and refrigeration. According to scholar Kumakura Isao, seasonality, while fundamental to modern tea aesthetics, was not so rigidly considered in tea writings before the nineteenth century. Edo-period tea texts, for example, reference foods and flowers that would be out of season in the months they were suggested for use.51 Culinary historian Nakayama Keiko has identified a disjunction in End ’s suggestions of certain sweets and their typical seasonality.52 And we can find a similar disconnection between seasonality and some of the other ingredients he uses in his menus when we compare these to contemporary guides to seasonal foods used by chefs, namely, Record of Seasonal Fish, Fowl, Vegetables, and Provisions (Gyoch

’s suggestions of certain sweets and their typical seasonality.52 And we can find a similar disconnection between seasonality and some of the other ingredients he uses in his menus when we compare these to contemporary guides to seasonal foods used by chefs, namely, Record of Seasonal Fish, Fowl, Vegetables, and Provisions (Gyoch yasai kanbutsu jisetsuki, listed in table 4 as Record), which reflects perceptions of seasonality and the availability of ingredients during the Kan’ei period (1624–44), and Anthology of Cuisine Past and Present (Kokon ry

yasai kanbutsu jisetsuki, listed in table 4 as Record), which reflects perceptions of seasonality and the availability of ingredients during the Kan’ei period (1624–44), and Anthology of Cuisine Past and Present (Kokon ry rish

rish , listed in table 4 as Anthology), published sometime between 1661 and 1673.53 Omitting preserved foods and prepared foods like tofu that were available year-round, the list in table 4 indicates that several of End

, listed in table 4 as Anthology), published sometime between 1661 and 1673.53 Omitting preserved foods and prepared foods like tofu that were available year-round, the list in table 4 indicates that several of End Genkan’s chosen ingredients for his menu for the eighth month (those indicated with an asterisk) were out of season by contemporary standards.

Genkan’s chosen ingredients for his menu for the eighth month (those indicated with an asterisk) were out of season by contemporary standards.

In this list of ingredients for End ’s banquet, nine of the ingredients would have been at their prime when served in the eighth month, but approximately half would have been out of season. Some of these, like pheasant, may have been available year-round but would not have reached their peak flavor, according to the authors of the two seasonal food texts. Even assuming these ingredients were available, it would still be a feat to find all of them in a modern supermarket or gourmet shop, let alone a market in late-seventeenth-century Kyoto or any other city. To obtain these in a form suitable for serving a lord would have been a monumental task, and a worrisome detail that End

’s banquet, nine of the ingredients would have been at their prime when served in the eighth month, but approximately half would have been out of season. Some of these, like pheasant, may have been available year-round but would not have reached their peak flavor, according to the authors of the two seasonal food texts. Even assuming these ingredients were available, it would still be a feat to find all of them in a modern supermarket or gourmet shop, let alone a market in late-seventeenth-century Kyoto or any other city. To obtain these in a form suitable for serving a lord would have been a monumental task, and a worrisome detail that End Genkan uncharacteristically omitted discussing, indicating that, although his representation of the realities of hosting a meal for a lord describes the high points like room architecture and menu planning, it omits the real drudgery of preparing the meal, such as shopping and doing dishes.

Genkan uncharacteristically omitted discussing, indicating that, although his representation of the realities of hosting a meal for a lord describes the high points like room architecture and menu planning, it omits the real drudgery of preparing the meal, such as shopping and doing dishes.

TABLE 4 SEASONALITY OF INGREDIENTS IN GUIDE TO MEALS FOR THE TEA CEREMONY, INDICATED BY MONTH

Ingredient |

Record (ca. 1624–44) |

Anthology (ca. 1661–73) |

|

Month |

|

sea bream* |

1st |

10th |

udo shoots |

8th |

8th |

tangerine |

|

8th |

taro |

|

7th–1st |

dried sea cucumber on a skewer |

|

8th–1st |

small shiitake mushrooms* |

4th |

|

dried gourd* |

11th |

|

whitebait* |

11th |

11–12th |

citron* |

9th |

|

crane* |

|

1st–3rd |

salted matsutake mushrooms |

8th |

8th–10th |

eggplant |

|

4th–10th |

shimeji mushrooms |

|