Investing is simple, but not easy.

—Warren Buffett

DARSE BILLINGS IS A Canadian computer scientist with a Ph.D. in computer poker from the University of Alberta. His research interests include abstract strategy games. His program “Mona” became the world champion of “Lines of Action” in 2000 when it defeated the best human players and won every game. Billings is credited with saying the following about poker:

1

There is no other game that I know of where humans are so smug, and think that they just play like wizards, and then play so badly.

Many in the investment management industry also fall into this trap of self-assurance.

2 Even worse, it is only one of the many biases that we as investors are afflicted with. This chapter examines many of our flaws, cognitive biases, heuristics we rely on, and errors we make as investors. The objective is to show that even though we understand and perhaps agree on the investment ideas we have discussed in previous chapters, we can fail in implementing them in real life, either in our personal portfolio or in large and sophisticated institutions.

Although this chapter discusses cognitive biases investors exhibit, our discussion differs from what you usually find in a behavioral finance book. We usually discuss how the bounded rationality of investors influences their trading behavior. Here we instead focus on the factors that can influence whether the investment approach discussed in this book can be adopted by institutional investors.

According to Charley Ellis, “Successful Investing does not depend on beating the market. Attempting to beat the market will distract you from the fairly simple but quite interesting task of designing a long-term program of investing that will succeed at providing the best feasible results to you.”

3 The more we obsess over short-term performance and forecasting, the less likely we are to achieve our long-term objectives and even, perhaps, outperform the market. Unfortunately, economic agents like investors, managers, advisors, or any decision maker are often entrenched in their beliefs, which complicates the accumulation of a coherent and generally accepted body of knowledge.

In previous chapters, we have made the case in favor of building investment processes based on three sustainable structural qualities. If we recognize the counterproductive impact of high fees and the role of luck in achieving investment success and agree that few managers are able to consistently generate value added, we must also conclude that it is unwarranted to pay high fees for portfolio management expertise that is not truly unique and can be replicated cheaply through structured investment processes.

We may agree with all of the above and still be unable or unwilling to implement investment processes that lead to efficient and appropriate portfolio solutions. The explanations lie in our own psychological traits and thinking process, an industry that promotes business philosophies at the expense of investment philosophies, and a lack of expertise and knowledge in many decision makers that find themselves unable or unwilling to challenge the status quo. Often being wrong while following the crowd appears less risky.

Chapter 7 is divided in three sections. First, we discuss the limits of human rationality and the many cognitive biases and mental shortcuts (heuristics) we rely on. Humans are not perfect rational beings. Investors do not make consistent and independent decisions, and they are subject to biases and emotions. Second, we closely examine how the confirmation bias reveals itself in the asset management industry. The content of these two sections will lead us to the last section in which we discuss the implementation requirements of a more efficient investment process for the benefits of investors.

The Limits of Human Rationality

We often underestimate the impact of heuristics, emotions, motivations, social influence, and limited abilities to process information on the integrity of our decision-making process. For example, you may recognize yourself in one or many of the following contexts:

• We prefer not to buy recent losers: we find it emotionally easier to buy an asset that has generated recent gains than one that has generated recent losses.

• We prefer to sell recent winners: we find it emotionally easier to sell an asset that has generated a gain than to sell one that has generated a loss. We hope our losing positions will eventually be proven right.

• We attribute successes to our superior skills and our failures to bad luck or market irrationality. We advertise our successes while we hide our failures. We also spend more effort to understand why we underperformed than why we overperformed because we believe success is attributed to our superior skills, while failure is caused by bad luck.

• We evaluate the actions of others according to their personality but our own as a function of circumstances. We will more easily accept that someone selling a losing asset has panicked, while we will rationalize doing the same as managing risk or abiding by some internal constraint.

• We look for sources of information that will reinforce our prior beliefs and disregard those that challenge them. Republicans are more likely to watch Fox News than MSNBC, while most Democrats are likely to do the opposite. Both networks appear more inclined to invite guests that agree with their views and biases.

• We believe more information leads to greater accuracy even though the evidence shows that it is self-confidence that grows with information, not accuracy. Experts have difficulty accepting that often just a few factors explain most of the variability in returns.

• We rewrite history. If our views are proven wrong, we will look for that part of our reasoning that supports the observed outcome and even adapt our prior story. We also take credit for an accurate forecast even if it was the result of faulty reasoning or plain luck. We may emphasize the fact that we had anticipated a weakening of financial conditions in 2007–2008, while ignoring that we were wrong about the amplitude of the crisis. We may have forecasted that oil prices would weaken temporarily in 2014 because of a seasonal increase in inventory, while not anticipating a decline of 50 percent.

• We anchor our estimates in initial values that may not be relevant. An interesting study looked at the sentences given by experienced criminal judges when prosecutors asked for either a twelve- or a thirty-six-month sentence on very similar cases.

4 When prosecutors asked for a longer sentence recommendation, the judge attributed a sentence that was eight months longer on average, indicating that judges were influenced not only by the evidence, but also by the request of the prosecutor. In finance we anchor our fundamental valuations on current pricing, future trends on past trends, and strategic asset allocation and product innovations on what friends, colleagues, and competitors do.

In his book

Thinking, Fast and Slow,

5 the Nobel Prize–winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman wrestles with flawed ideas about decision making. In the 1970s, it was broadly believed that human beings were rational, but that emotions were responsible for making them act irrationally. When the stakes are high enough, people will focus and make good decisions. Economic models mostly relied on rational decision-making agents. But Kahneman questioned whether investors make choices and decisions by maximizing the net present value of future benefits of their actions and whether they understand the potential long-term consequences of their daily actions.

Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky showed that people making decisions under uncertainty do not act rationally.

6 In a series of experiments they identified many cognitive biases that distort our judgment, while never going as far as saying that humans are irrational. These cognitive biases are not necessarily flaws, but perhaps evolutionary adaptations to our environment.

7Following a large number of empirical studies in the fields of psychology and neuroscience, there has been in recent years much improvement in understanding human thought. According to Kahneman, emotions shape the way in which we think and make decisions; emotions precede logic, not the other way around.

In his book, he describes the idea of System 1 and System 2 within the human brain. System 1 is the emotional, intuitive, and fast-thinking process that allows us to successfully navigate much of our daily life. System 2 is our controlled, slow-thinking, and analytical process. While System 1 is effortless, essentially unconscious thought, System 2 requires conscious effort; System 1 is the habitual, System 2 is a goal-directed system. These systems are abstract representations that help us understand the process of decision making; they do not necessarily correlate to specific areas of the brain.

System 1 governs most of our life. As we learn and repeatedly use new skills, they become internalized, automatic, and unconscious. System 1 provides an immediate environmental impression so that we may quickly respond to our surroundings; the system is efficient, but far from infallible.

On the other hand, System 2 is slow but able to perform more complex tasks. Kahneman uses the examples of 2 + 2 and 17 × 24 to illustrate both systems. Most individuals do not think about 2 + 2; the answer 4 comes automatically. However, computing 17 × 24 generally requires greater mental effort. The relative efficiency of System 1 and System 2 is very much a function of individual skill, training, and learning by association. A grand chess master may be able to look at a chessboard and see that you will be checkmate in two moves. However, most of us would need to expend concerted effort and thought on the problem, some unable to ever reach the chess master’s conclusion. We therefore rely on System 2 to tackle this intellectual challenge, but also find evidence that System 1 can be improved over time.

Though System 2 monitors System 1, it usually only endorses the actions generated under System 1. System 2 is in principle the master of System 1, but it is also lazy. A continuous effort from System 2 is mentally and physically demanding. When driving at a low speed on an empty road, System 1 will do most of the work. However, when driving in a blizzard on snow-covered roads in bad visibility, System 2 will engage, leaving the driver mentally and physically exhausted.

When System 1 is left unchecked by System 2, errors in judgment may occur. Decisions made under System 1 lack voluntary control; this can be problematic, considering how often System 1 is employed to make decisions. Because System 1 is on automatic mode, it is also responsible for many of the biases we have and for errors in judgment we make. System 1 believes that it possesses all the necessary information. Kahneman refers to this bias as WYSIATI (What You See Is All There Is); decisions are made on the basis of sparse and unreliable information. System 1 allows personal feelings to influence our judgment of a speaker’s credibility, while also allowing an individual’s beliefs or occupation to influence our personal feelings about them.

Impressions from System 1 are fed to System 2. Whenever System 1 senses an abnormal situation, System 2 is mobilized to protect us. In principle, System 2 can override the inaccurate impressions of System 1, but System 2 may be unaware that System 1 is misled in its conclusions. Because System 2 is unable to always identify or correct System 1’s mistakes, it is not necessarily the ultimate rational tool used by economists. For example, because the average individual is usually not good at all with probabilities and statistics, we simplify our judgments such that System 1 can handle complex situations using heuristics, that is, simple and practical but not necessarily accurate methodologies.

As an illustration, Kahneman recalls an experiment called “the Linda problem.” Participants were told the imaginary Linda was a single, outspoken, bright individual who as a student was deeply concerned with the issue of discrimination and social justice. Participants were then asked if it were more likely that Linda is a bank teller or if Linda is a bank teller that is active in the feminist movement? Eighty-five percent of the students at Stanford’s Graduate School flunked the problem by selecting the second answer even though we know that all bank tellers who are active in the feminist movement are by definition bank tellers. The second answer better fits our perception of Linda’s personality; System 1 engaged in the story, while System 2 remained inactive, allowing us to jump to a false conclusion.

Another example is the problem of the baseball and the baseball bat. Together they cost $1.10 and the bat costs $1 more than the ball. What is the cost of the ball? Most people unthinkingly answer 10 cents, allowing System 1 to think for them. However, carefully thinking about the question statement reveals that the ball must cost $0.05 such that both together cost $1.10. Again, System 2 did not step in when it should have.

There may be a reason for the sluggishness of System 2. According to neuroscientists, the parts of the brain associated with emotion are much older than those associated with logic.

8 The evolutionary need for emotion preceded the need for logic. James Montier of GMO uses the example of the snake behind the glass: when it jumps and strikes the glass, you will react, though you aren’t in any real danger. System 1 assesses the threat and tells you to step back before System 2 realizes that it is not necessary.

Below is a list of personality traits, cognitive biases, and heuristics we have observed in investors (including the two of us) during our careers. Kahneman provides in his book a more thorough discussion of heuristics and biases. Most of them also make implicit references to our imperfect understanding of probabilities and statistics. Here our discussion centers on the world of portfolio management.

• Paying too little attention to prior probabilities: We often misuse new evidence and inappropriately adjust probabilities we attach to different events. Some investors listen to stories from fund managers, like the great trade they did last quarter, and attach too much weight to them compared to the base probability of a fund manager being talented.

•

Paying too little attention to sample size: Many of us rely on a track record of three to five years to determine a fund manager’s talent, but as discussed in

chapter 3, standard statistics indicate that it is almost impossible to infer any conclusion from such a small sample. Yet many of us believe it is sufficient evidence of a manager’s talent.

• Illusion of correlation: When Kahneman examined the performance of twenty-five advisors working at a wealth management firm, he could not find any correlation between their performance ranking in a specific year with their ranking any other year, indicating that no advisor displayed more skills than any of his peers. Yet bonuses were paid based on short-term performance. Though the firm’s management did not expect a high correlation, they were surprised to find none at all; they had never attempted to collect such data.

• Misconception about predictability: We believe we can predict what is unpredictable: “This firm will be the next Google.” Yet no one could have predicted that Google was the next Google, even its founders. Indeed, Larry Page and Sergey Brin were willing to sell their company for less than $1 million a year after its founding, but the buyer thought the price too high.

As discussed in

chapter 4, we can predict what is the most likely event or characteristic of the distribution of likelihood of different events, but the event itself is unpredictable. During a 2013 investment innovation conference, Craig Pirrong, professor of finance and energy specialist at the University of Houston, presented his views of the energy sector and started with the following statement: “I hope I will be lucky or that you have a short memory.”

9 Craig understood that even though his forecasts were grounded in his greater understanding of the energy industry, our track record at understanding what can be predicted, especially in complex systems (the new world order and the energy industry certainly qualify), is dismal and marred with distortions, an opinion shared by the trader-philosopher-statistician Nassim Taleb.

•

Misconception of regression to the mean: We prefer assets or funds whose recent performance has been exceptionally good. We shun those whose recent performance has been exceptionally bad. If these exceptional performances are simply luck (high or low ε), it is not indicative of future performance.

10 Imagine that a manager has just been extremely lucky. His expertise lies in spotting undervalued companies, but he was uniquely positioned to profit from the plunge in oil prices, which he did not fully anticipate. Subsequently, his performance is less stellar. Has he lost his edge? Not necessarily. It is just regression to the mean at work. His previous outperformance is more likely to be followed by less impressive outperformance. It was luck and thus not indicative of future outperformance. Yet many of us would mistakenly conclude that this fund manager has necessarily lost his edge.

• The availability heuristic: The availability heuristic describes our tendency to attribute a higher probability to an event that can be easily recalled or understood. We tend to attribute more weight to what we are familiar with even though it may not be as relevant, and vice-versa. Many investors confuse investment philosophies and investment methodologies. An investor not familiar with quantitative processes is more likely to dismiss this approach compared to a fundamental approach even though both may be targeting the same investment style with different methodologies.

The availability heuristic also explains why it is so hard for us to recognize our limited forecasting ability. This is because we tend to remember forecasters whose predictions turned out to be right and forget those that turned out to be wrong. It is easier to recall the first instance than to recollect all of those whose predictions have failed. Hence we overestimate our average forecasting ability.

•

Inferring the general from the particular: Many asset management firms have a large number of products on their platform. Because all products do not outperform (and perhaps few do outperform in the long run), they have the ability to market those products that have recently outperformed, maintaining a positive profile for the firm at all time. Many investors mistakenly have more favorable views of the global performance of this firm’s funds.

Another example comes from the survivorship bias in performance data. Some firms maintain a database of historical funds’ performances, for instance hedge funds. When a fund closes its doors due to poor performance, its performance can either be kept in the database or its entire history can be dropped. In the latter case, our assessment of the overall performance of hedge funds would be too favorable because it would overlook the ones that performed poorly.

• Confusing personal preferences with an investment’s risks and benefits: Our own evaluation of the attractiveness of an investment may be tainted with our personal views. For example, we can view technologies that we like as lower risk investments than those that we don’t. We can attribute a higher value to risky technologies that are still in their infancies. Renewable energy is generally an attractive idea, but it took a long time for profitable business models to emerge.

• Illusion of understanding or the outcome bias: We often revise our prior understanding of events given what has happened, forgetting what may have happened but did not.

The financial crisis of 2007–2009 is a perfect example. There is a good reason we say “crisis” and not “recession” or “downturn.” By definition, a crisis requires that the causes are hard to discern and the consequences hard to predict, otherwise the events do not unfold into a crisis. Let’s say that enough economists, policymakers, and financiers are able to spot the problems that subprime lending could create. They act by either publicizing their analysis, instituting new regulations, or trying to benefit from their information in financial markets (by short selling subprime lending related securities for example), all of which diminishes the causes and likelihood of a potential crisis. To turn this into a crisis requires that these actions do not happen to a large enough extent, that not enough people

knew there would be a crisis.

Yet many people, with the benefit of hindsight, say that they knew either the crisis would happen or that it was obvious that it would happen. Knowing the causes and the fact that it happened, of course it is obvious that the crisis happened. We also like to rewrite history by turning our previous “I expect a weakening of credit conditions” into “I knew that there would be a financial crisis.” We also often fail to take into account other risk buildups in the system that may cause a dramatic event that actually did not happen or has not yet happened.

•

Hostility to algorithms: We have already touched on this issue in

chapter 4. Experts dislike statistical approaches because they democratize the ability to explain and predict and hence reduce people’s reliance on their opinion. In many instances, a statistical algorithm based on a small set of explanatory variables left unaltered by the subjective opinions of experts will perform better. It does not mean that investment experts are not needed; we still need to determine the nature of these simple models and the variables that should be used. Rather, it is that altering the results with subjective opinions often does not improve the results.

Simple algorithms are already pervasive in our economy. Genius in Apple iTunes is the result of a relatively simple algorithm that evaluates music taste based on the predefined characteristics of songs listened to in the past. Many financial products are now built around relatively simple methodologies (Fundamental Indexing, equal weight allocations, equal risk allocations, etc.).

• The illusion of validity: Complex systems, such as financial markets, are hard to understand and predict. Many managers believe they will achieve better forecasts if they compile more information. Having more information may make you feel that the conclusion you reach is more valid, but adding more variables may not necessarily increase the explanatory power of your model. In many cases, using complex models with many variables to understand complex systems illustrates an inability to identify the most relevant factors. Such an approach is likely to succumb to data mining, the idea that if we test enough variables, we will eventually find a pattern, albeit a spurious one.

This effect is well known to statisticians. Adding more variables that do not add additional information to a model may appear to boost its explanatory power unless we explicitly control for such phenomenon.

• Our bias against the outside view: When confronted with a complex situation, experts are more likely to extrapolate based on their unique experience (the inside view), often leading to overoptimistic forecasts. Kahneman in what he calls the planning fallacy, examines how we overestimate benefits and underestimate costs of outcomes. We tend to ignore pertinent input, actual outcomes observed in previous, similar situations (the outside view). Is it more reliable to estimate the cost of remodeling a kitchen based on the components you believe would be involved or would it better to inquire about the cost of several similar projects?

Let’s consider the financial crisis. When it occurred, most were faced with a situation they had never experienced. Economic forecasters were making overly optimistic predictions on how quickly the economy would recover. However, Carmen and Vincent Reinhart looked at the behavior of economic growth, real estate, inflation, interest rates, employment, etc. over a twenty-year period in fifteen countries that lived through a financial crisis after WWII, as well as considering two global crises (1929 and 1973).

11 They used these examples as benchmarks to determine what could happen after the most recent crisis. The results were more accurate than most had initially expected.

Although the reality of these biases is confirmed by well-designed empirical tests, how do we understand and avoid them? Heuristics alone cannot explain all of the behaviors observed in our industry. The next section further discusses the role of the confirmation bias and its interaction with investment experts’ incentives and conflicts of interests.

Different Forms of the Confirmation Biases

In many circumstances the biases discussed in the previous section also serve one’s interests.

12 Individuals will often seek or interpret evidence in ways that are partial to their existing beliefs or expectations. This trait, known as the confirmation bias, is possibly the most problematic aspect of human reasoning. This confirmation bias can be impartial (spontaneous) or motivated (deliberate, self-serving), perhaps even unethical.

When the confirmation bias is impartial, evidence is gathered and analyzed as objectively as possible, but it is unconsciously subjected to biases. When the confirmation bias is motivated, evidence supporting a position is gathered and purposely accorded undue weight, while evidence to the contrary is ignored or minimized. According to John Mackay, “When men wish to construct or support a theory, how they torture facts into their service!”

13 Of course, confirmation bias can be either impartial

or motivated. Cognitive biases alone cannot fully explain the existence of self-serving biases, but they may provide the means by which our own (biased) motivations have the capability to impact our reasoning.

14What is the source of motivated confirmation biases? “It is psychology’s most important and immutable behavioral law that people are motivated to maximize their positive experiences and minimize their negative ones.” Individuals remember their decisions and actions in ways that support their self-view. When they cannot appropriately promote themselves or defend their interests, they will misremember or reconstruct events and circumstances and make excuse for poor performance along the lines of: “I would have been right if not for…” or “I was almost right but something happened.” Individuals’ interests can be classified in many categories, but the most important levels of interests are those related to Global Self-Esteem, Security, Status, and Power, and finally Respect, Affluence, and Skills. Montier uses a more colorful nomenclature such as pride, envy, greed, and avarice, all of which can lead to confirmation biases.

Another source of motivated confirmation bias is peer pressure. Research has shown that when individuals are confronted with a group answer that they believe to be wrong, one-third of them will still conform to the answer of the group. Similarly, standing alone with a distinctive opinion is painful to us. Neuroscientists have found that maintaining an opinion opposed to the majority stimulates a region of the brain most closely associated with fear. Therefore it is easy to imagine why we may succumb to anchoring.

Unfortunately, all of these circumstances are present in our industry. We have witnessed cases of strong-willed individuals swaying entire groups in the wrong direction, leading in several cases to extremely costly consequences. Groups can easily succumb to anchoring and tunnel vision. The first individual in a group discussion to express a strong opinion can strongly influence decision making (intimidation), narrow the set of alternatives being considered (tunnel vision), and intimidate/attract support from less knowledgeable and less confident participants (anchoring) even if he is not the individual with the highest authority. If you act as an advisor during one of those meetings, you may attempt to present other arguments and hint at potential consequences, but you cannot necessarily challenge an officer of this firm (your client) if no one else within this firm dares challenge his views. The same process occurs if, as a manager, you notice incorrect statements were made by an overconfident advisor in front of his client. Will you challenge this advisor if it can cost you a portfolio mandate and if it is likely the client is unable to understand the nature of the conversation even if it would be in the best interest of the client?

There exists a great deal of literature supporting confirmation biases, and those who have spent enough time in the corporate world have run into some form or another. We will provide a few examples.

15 However, we always have to remain aware that some biases can be intentional, while others are the product of System 1.

Restricting Our Attention to a Favored Hypothesis

This occurs when we are strongly committed to or familiar with a particular opinion, allowing ourselves to ignore other alternatives or interpretations. Failing to examine other interpretations is the most prevalent form of confirmation bias. Let’s consider a few examples.

Example 1—

Chapters 5 and

6 supports the case for an integrated portfolio management process across asset class factors and for the asset allocation process itself. This implies that a properly structured balanced product of asset classes or factors is far more efficient than a piecemeal approach. However, most portfolio structures in our industry are designed around the concept of specialized asset class buckets (such as fixed income, equity, real estate, other alternatives) because of the belief that it is more efficient to manage the asset allocation process as a fully independent function. The investment policies of many organizations make it difficult, sometimes impossible, to integrate balanced products in their portfolios. Of course, the consulting industry is not fond of an integrated approach either because it removes part of their contribution to manager selection and asset allocation. It is not as profitable a business model for them. Even advisors have conflicts of interest.

Example 2—Every quarter, managers often explain their performance in front of investment committees. Presenting a favorable performance is gratifying and favorable performances generate far fewer questions by investment committee members than unfavorable performances. Have you ever heard an investment committee member saying: “This performance is very good but I worry about the level of risk that was required to achieve it. Could you explain?” or “Could your outperformance be the result of a benchmark that is not representative of your investment style?” Rarely is the benchmark itself a subject of deep discussions. However, when we compare the performance of a portfolio to a benchmark, we should always ask: “Is the portfolio outperforming the benchmark or is the benchmark underperforming the portfolio?”

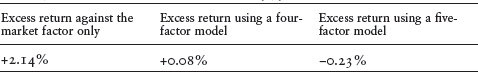

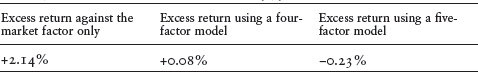

Table 7.1 illustrates this aspect. It again presents the three measures of alphas for the FTSE RAFI U.S. 1000 Index shown in

table 6.3. One measure of excess return is largely positive, while the two others are close to zero. One is even slightly negative. As we already indicated, there is nothing wrong about having a small α as long as the sources of returns are understood, investors have the desired exposure to the risk factors, and they do not pay excessive management fees for exposure to risk factors. The sources of performance in the RAFI products have been well documented and the licensing fees to institutional investors are very reasonable.

TABLE 7.1

Measures of excess return (1979–2015)

However, most managers do not disclose their factor exposure and all excess return is presented as α. Over the years, we have come to realize that not all institutions use fair or representative benchmarks. Because compensation is related to outperforming a benchmark, there is much incentive by managers to choose a reference point that is more likely to be outperformed over the long run. The following situations have been observed in several organizations:

• A fixed income portfolio with almost no Treasury securities benchmarked against an index with a large allocation to Treasuries;

• A mortgage portfolio benchmarked against a fixed income index also containing a large allocation to Treasuries;

• An equity portfolio benchmarked against a combination of cash and equity without having completed a proper factor analysis to determine what is appropriate;

• A private equity portfolio benchmarked against a cash plus index in which the plus part is fairly low;

• And long biased equity hedge funds benchmarked against a cash plus index. It seems we forget common sense when we use the words “Hedge Funds.”

Investors must realize that some managers are wealthy not because of their skills but because of their benchmarks.

According Preferential Treatment to Evidence Supporting Belief

This bias occurs when we give greater weight to information that supports our beliefs, opinions, or business models than to information that runs counter to them.

Example 1—In

chapter 5, we mentioned the two studies on commodities published in the same issue of the

Financial Analysis Journal in 2006. One study concluded that commodities delivered a substantial risk premium between 1959 and 2004, while the other found that the risk premium was actually negative. Two studies with different conclusions—and unsurprisingly the one favoring a higher risk premium has been cited 50 percent more often in the literature.

16Example 2—We have discussed the importance of having a benchmark appropriate to the portfolio policy. However, the design of certain indices can present a more favorable view to incite potential investors to invest. For example, the Hedge Fund Research Fund Composite Index (HFRI) uses a monthly rebalanced equal weight allocation to all available hedge funds. This can contribute to better risk-adjusted return for the index due to diversification benefits. However, no investor could actually achieve the same performance because it would be impossible to implement the same allocation process. Of course, the benchmark construction methodology is disclosed to investors, but we doubt that most investors fully understand the favorable impact of the methodology on measures of past performance.

Seeing Only What One Is Looking For

Unlike the previous bias, which results from a tendency to favor specific sources of information and ignore others, here the bias occurs because we unfairly challenge the validity of information that runs counter to our beliefs and support unsubstantiated or irrelevant claims that bolster our case.

Example 1—The circumstances of the last U.S. presidential election illustrate this point fairly well. Politicians and pundits tend to criticize the accuracy of polls that do not reflect their own beliefs. According to Tetlock, it is not necessarily that these individuals are close-minded, but simply that it is easy for partisans to believe what they want to believe and for political pundits to bolster the prejudices of their audience.

Nate Silver predicted the presidential winner in all but one state as well as all thirty-five senate races in 2008. In 2012, he accurately predicted the presidential winner in all states as well as thirty-one of thirty-three senate races. Nevertheless, some of Silver’s critics attempted to discredit all of his conclusions by attacking his methodology. For example, the political columnist Brandon Gaylord wrote about Silver:

17Silver also confuses his polling averages with an opaque weighting process (although generally he is very open about his methodology) and the inclusion of all polls no matter how insignificant—or wrong—they may be. For example, the poll that recently helped put Obama ahead in Virginia was an Old Dominion poll that showed Obama up by seven points. The only problem is that the poll was in the field for 28 days—half of which were before the first Presidential debate. Granted, Silver gave it his weakest weighting, but its inclusion in his model is baffling.

However, what Silver does is simply to consider all relevant information and attribute to each component a weighting based on its strength using variables such as the accuracy of such polls in the past, sampling size, and timeliness of information. For example, the Virginia poll in question had received a low weighting in Silver’s model. His approach is based on a rigorous application of probability theory as it is being taught in most colleges.

Example 2—For many years, the Canadian mutual fund industry suffered a reputation as having one of the highest total expense ratios (TER) in the world, following a report published in a top journal.

18 Answering criticisms in a letter to the president and CIO of the Investment Funds Institute of Canada, the authors confirmed their results, indicating that total expense ratios and total shareholder costs in the Canadian industry were higher than those in Australia, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, and so-called offshore domiciled funds from Dublin, Luxembourg, and various offshore locations. Furthermore, the situation in Canada is even worse because, according to the Canadian Securities Administrators, individual investors have a limited understanding of how advisors are compensated. Fortunately, new regulations may now force greater disclosure.

19 The industry has been attacking this inconvenient report for years.

The Canadian industry requested an “independent” study to challenge this perception.

20 They narrowed their intervention to the United States only because it may be difficult to challenge the observation that Canadians pay more than investors in almost all jurisdictions. The main argument of the industry is that TER in the United States do not incorporate advisory fees while in Canada they do, and by accounting for this factor, the difference with the United States may not be as significant. It has been our experience, however, that Canadian financial products are in fact more expensive than similar products in the United States. In the end, the Canadian industry has to fight the argument that TER are higher in Canada until it can restructure itself and become more competitive, no matter what reasonable evidence would show.

This bias refers to our tendency to express a higher degree of confidence than is justified by our actual performance.

Studies have shown that specialists in a wide range of fields including attorneys, physicists, physicians, psychologists, and engineers are overconfident when making professional judgments. As we mentioned in

chapter 4, although investing experts are more confident in their forecasts than laypeople, they are not necessarily more accurate. Though studies show clinical diagnosis based on case statistics to be more accurate than those derived from clinical judgments, experts still have more confidence in their own judgment.

21 One exception is professions that benefit from immediate and continuous feedback (like weather forecasters), although feedback, especially negative feedback, is not necessarily welcomed.

According to Tetlock, “One of the things I’ve discovered in my work on assessing the accuracy of probability judgment is that there is much more eagerness in participating in these exercises among people who are younger and lower in status in organizations than there is among people who are older and higher in status in organizations. This doesn’t require great psychological insight to understand this. You have a lot more to lose if you’re senior and well established and your judgment is revealed to be far less well calibrated than those of people who are far junior to you.”

This discussion helps us understand why the super forecasters in the Good Judgement Project discussed in

chapter 4 have had much greater success than others. Tetlock used our understanding of human psychology and evidence concerning the superiority of algorithms over human judgment to design an experiment that identifies individuals trained in probabilistic thinking and suffer less from the effects of ego. They seek continuous feedback and are unafraid to challenge their own views. They are the closest representation of human algorithms. We recommended the use of robust investment processes in

chapters 6 because most of us do not possess that which is required to become a good forecaster. Process is what protects us against our own human biases. We have to remember that the obstacles to a rational process can be overwhelming, even among scientists and specialists. For example, Newton could not accept the idea that the earth could be much older than six thousand years based on the arguments that led Archbishop Usher to place the date of creation to 4004

B.C.E. “The greatest obstacle to discovery is not ignorance—it is the illusion of knowledge” (Daniel J. Boorstin). It may be that better forecasters and better scientists are among those who have fewer illusions about their own knowledge and a smaller ego.

The Requirements of a More Rational Decision Process

How can investors implement a more rational investment process in the face of the obstacles discussed so far? In principle, while it is difficult to overcome biases, it should be easier to implement a rational process for an organization than for an individual. Decisions in most organizations are often subjected to a lengthy, complex process, while many retail investors make quick, emotional, and uninformed decisions.

A provider of low-cost investment solutions to retail clients reminded us how some of his clients will quickly move their assets to another manager if the balanced portfolio solutions he offers underperformed slightly compared to another product in their portfolio. The short-term return without concerns for risk seems to be the only consideration for some uninformed investors. Tremendous efforts at financial education are required at a younger age and much better education tools than are currently available must be designed.

This being said, organizations are certainly not immune to biases. Important decisions can be pushed through by individuals even though they may be suboptimal for the corporation. Decisions are sometimes subject to committee approval in which some members may lack necessary expertise, lowering the odds of individual accountability in the case of failure, but allowing all to claim contribution to a successful endeavor.

Investment committees with overloaded agendas may simply rush through them. For example, as a manager you may be given less than twenty to thirty minutes to explain your strategy to an investment committee in order to win an approval for a mandate that could be several hundred million dollars in size. Hence we operate in an industry in which we must often oversimplify the message to the point at which a meaningless but entertaining storyline becomes more important than understanding the investment principles.

The purpose of this last section is to provide the basis for the implementation of more rational investment processes by investors and their representatives, such as CIOs, investment committees, etc. We will use the term Management to refer to those parties in positions of authority of allocating capital to managers and strategies. On the other hand, managers, advisors, and consultants refer to those who manage assets, sell investment products, and provide asset management services.

Managers and Advisors Are Not Your Friends

An important principle to keep in mind is that fund managers and advisors are not your friends. Their interests are often not aligned with Management’s interest. Managers are selling Management a product, and they respond to their own set of incentives and are subject to biases. Alan Greenspan said the following with respect to the subprime crisis: “Those of us who have looked at the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholder’s equity (myself included) are in a state of shocked disbelief.”

22 Well, self-interest should be expected when considering the exorbitant bonuses of some individuals in financial services. Let’s consider the statement by Greg Smith, former executive at Goldman Sachs: “I don’t know of any illegal behavior, but will people push the envelope and pitch lucrative and complicated products to clients even if they are not the simplest investments or the ones most directly aligned with the client’s goal? Absolutely. Every day, in fact.” One of the messages of agency theory, which studies the relation between principals (shareholders) and their agents (management), is that the asset owner should not be surprised that the agent’s primary concern is not for the client.

Even if you like your advisors on a personal level or are intimidated by their understanding of the subject, it does not mean that they should not be challenged. According to the field of evidence-based management, decisions should be made according to four sources of information: practitioner expertise and judgment, evidence from the local context, a critical evaluation of the best research evidence, and the perspective of people affected by the decision.

23 However, corporations will often implement processes recommended by advisors who have in fact little case evidence of the efficacy of their proposals. In the field of management, a senior consultant admitted that the restructuring processes they implemented in several firms made millions in revenues during the initial phase and then millions more from the same clients who had to fix the organizational issues created by the restructuring.

24 It is perplexing that some advisors require, in recommending a product to investors, a performance track record of a few years, but no such equivalent evidence for implementing new processes or strategies that they have designed themselves. In principle, the roles of advisors are to:

25• Provide specialized technical and subject matter expertise;

• Validate what management wishes to do or has done;

• Present, particularly to boards, unpleasant realities;

• Serve as a catalyst, facilitator, enabler, and guide to the organization.

In most cases, advisors provide support and facilitate the decision process of Management. In this process, advisors must challenge Management while Management challenges advisors, but often advisors are not sufficiently challenged. Here are two examples.

During a recent investment conference, one presentation was given on how investors should allocate their assets between tax-free retirement accounts and taxable accounts. The presenter provided the traditional advice that fixed income securities should first be allocated to the tax-free account because tax rates on interest income are usually greater than on domestic dividends and capital gains.

As recently as February 2015, when the most prevalent bond index in Canada was trading at about a 1.75 percent yield before fees, investors were still being advised the following by a national publication:

If you have enough money to build both a registered (tax-free) and non-registered (taxable) portfolio, then investments such as bonds, GICs and high-interest savings accounts are best kept inside of an RRSP (tax-free account equivalent to an IRA), because their interest income is taxed at a higher rate. Capital gains and dividends are taxed at a lower rate, so stocks can go outside your RRSP.

26This may have been the appropriate recommendation when interest rates were much higher, but in mid-2015 we operated in an environment in which yields on bonds were as low as 2 percent, dividend yields on some equity products were sometimes even higher than bond yields, and equities still had an expectation of long-term capital gains while the argument was more difficult to make for bonds. Do you prefer to avoid taxes on a bond product having a 2 percent expected return that would normally be taxed at a higher rate and be taxed at a lower rate on an equity product having a 6 percent expected return? Or do you prefer to avoid taxes on that 6 percent of expected return and be taxed at a higher rate on less than 2 percent of expected return? From a return compounding point of view, it is preferable to avoid taxes on the asset that has the higher nominal expected return.

Furthermore, foreign equity usually does not benefit from a preferential tax treatment on dividends and some specialized equity products target dividend yields that could even be higher than bond yields. Hence in a low-return environment, the argument to allocate dividends paying foreign securities to the tax-free account first is even stronger, especially in the context of exchange traded funds that charge relatively similar fees on fixed income and equity products (although there must be considerations for how withholding taxes are impacting performance in different investment vehicles). Finally, if bond portfolios are more likely to produce long-term capital losses, these capital losses would be very useful within a taxable account. The point is that this traditional advice may be valid on average, but not necessarily in the current market conditions.

The second example refers to an institutional investor that asked its advisor how they could increase the risk of their portfolio. The portfolio was mostly allocated to large market capitalization global equity and investment grade fixed income. Because the portfolio already had a relatively low allocation to fixed income, the advisor initially recommended that the portfolio be leveraged using equity futures contracts in order to maintain appropriate portfolio liquidity from the fixed income component. This advice is based on the traditional assumption that fixed income securities are more liquid than equity. But the recent decade of financial research has shown how securities are subject to liquidity risk, which is the possibility that their level of liquidity may vary through time, and especially vanish in crisis time.

27 The liquidity of bonds from provincial government in Canada was minimal during the worst of the financial crisis in the fall of 2008. If liquidity was required at that moment, it was easier to trade large market capitalization stocks than these bonds. The advice provided was unfortunately based on outdated knowledge.

Traditional advice should always be challenged. These two examples are not alone either. In finance, we encounter many dubious claims, for example:

• Managers with high active shares have more expertise;

• A 50 percent currency hedging on foreign exposure is a neutral position;

• Managers are more likely to outperform in an environment in which there are greater discrepancies in sector returns. The statement here refers to the probability of outperforming not to the scale of outperformance;

• Quantitative management is not as effective as, or is different from, fundamental management;

• Published funds’ ratings are always useful to identity future performers;

• Commodities (in general), gold, and real estate are good inflation hedges;

• The average forecasting expert brings benefit to the allocation process;

• Nominal corporate profits will lag in a rising inflation environment.

Each of these statements has been challenged with existing literature. Let’s consider the first four. We already mentioned in

chapter 2 the study by AQR indicating that managers with a high

active share may have a small-capitalization bias, which may explain some of the results. Furthermore, even if we ignore this aspect, performances could be explained by the fact that such funds would be more efficient at diversifying mispricing because the allocation processes of benchmark agnostic managers are generally insensitive to the impact of market prices on weights. We also discussed in

chapter 6 how the pro- or counter-cyclical nature of a currency impacts the optimal currency hedge ratio of a portfolio. Hence a 50 percent hedge ratio is not necessarily a neutral position. Although active managers often say that greater volatility among sectors, countries, or securities is preferable to outperform, there is no evidence that greater volatility increases the probability of outperforming (although it will impact the scale of outperformance) by specific managers. Finally, there is no study that indicates that traditional value managers outperform systematic value investment processes. Again, the exposure to the value factor is a more significant determinant of long-term performance than the specific methodology used to achieve it.

The previous two examples are also good examples of the System 1 and System 2 discussion at the beginning of this chapter. When we no longer challenge traditional beliefs, answers are simply stimulated by System 1. Montier also mentions how expert advice attenuates the activity in areas of the brain that correlate with valuation and probability weighting. Thus, when Management is provided with advice from what is believed to be a reliable source, their System 2 is prone to get lazier. Therefore using advisors does not mitigate the responsibility of Management to remain diligent and Management should not be intimidated by the clout of advisory firms.

Managing Overclaiming and Disappointments

The human tendency to exaggerate success provides biased information, complicating Management’s decision process. We sometimes overrate our ability to spot deception and distinguish the relevant from the irrelevant. As discussed in

chapter 4, individuals draw attention to correct forecasts while downplaying bad predictions. Additionally, there are ways of presenting numbers in a more favorable light. We mentioned in

chapter 2 that some variable annuity products guarantee a minimum return of 5 percent per year during the accumulation phase, which can be ten years or more. However, in the United States the return is compounded, while in Canada it seldom is. Canadians looking at these products may be unaware of the nuance. Yet it means the U.S. minimum guarantee over ten years is greater by nearly 13 percent of the initial contract notional (62.89 percent versus 50 percent). There are many more nuances that only emerge through a careful analysis of these contracts.

The incentive to overclaim is substantial because claims made by managers, advisors, and consultants are often left unchallenged. This unfortunate state of affairs can be reduced in several ways depending on the circumstances:

• Requesting empirical evidence supporting the skill being marketed by managers, advisors, and forecasters.

In the end, when an organization considers hiring an expert who claims to have a specific forecasting ability, it should request empirical evidence over a long period before arriving at a decision and consider the sample size and the inaccurate as well as the accurate forecasts. Forecasting a recession that does not occur can be costlier (financially and professionally) than failing to forecast a recession. In marketing themselves, forecasters will emphasize only their successful forecasts. It may seem obvious, but the work of Phil Tetlock illustrates that experts with no forecasting abilities can still have very long careers.

• Establishing the rules of a pre- and post-mortem ahead of any important decision. When making an important decision, investment or otherwise, Management should attempt to determine potential issues and consequences before they occur and which metrics will be used to measure success after implementation of this decision.

28 The understanding by all that are involved in the decision process that there will be a defined feedback mechanism and that this information will be communicated will downplay overclaiming at the initial stage.

29 Furthermore, it is also important to manage the effect of surprise. It is much easier for Management to understand and communicate internally unfavorable performances in specific circumstances if Management was already aware of the specific circumstances that would trigger an unfavorable outcome.

Consider, for instance, the implementation of a plan by a pension fund to move away from an indexed equity allocation to products that extract specific factors, such as size, value, momentum, and low-beta. Moving away from an indexed allocation creates a tracking error risk not only against the index, but also possibly against the peer group. Even if Management fully understands this aspect, it is doubtful that most of the pension fund participants do. Implementing a true long-term approach for asset management is challenging.

For example, Andrew Ang mentions how the year 2008 erased all the active returns the Norwegian fund had ever accumulated.

30 The public understood the decline in market returns but not in active returns. The issue at hand is communication and education. The public was well informed of market risk but not of factor risks. They never understood that active management could perform so badly across the board under specific circumstances.

The quant meltdown in 2007 gives a proper example of this risk. During the week of August 6, 2007, a significant decline in the performance of strategies linked to risk factors other than the market portfolio occurred in the U.S. stock market. The cause is believed to be a large fund that closed its positions, thereby precipitating the decline of stocks bought and an increase in stocks sold short by similar funds. What is particular is that important losses were experienced in these strategies, whereas the market index was unaffected. For example, the momentum and low-beta factors ended the week about 3 percent down, while the market was up by more than 1 percent.

We also reported in

chapter 6 that on a rolling ten-year basis, 2015 is one of only two periods since the early 1950s in which the market factor dominated all other risk factors. In the first seven months of 2015, the stock market performance was dominated by large market capitalization and growth firms, leaving well behind lower market capitalization and value firms that are the backbone of many smart beta strategies. Amazon alone explained one-third of the rise of the entire consumer discretionary group during this period.

31By definition, a risk factor is exposed to bad times. Hence although factor-based products tend to outperform traditional indices in the long run, Management must understand that they can underperform for several years. The most important aspect is to educate Management about the sensitivity of returns to risk factors and how specific products load on these factors. We must do more than manage overclaiming (i.e., that a new strategy will necessarily outperform), we must also manage overexpectations. The following section examines this recommendation further.

Raising the Bar on Benchmarking

Without proper benchmarks, we cannot easily detect or challenge overclaiming. In our industry, significant bonuses and fees are paid, while many researchers have shown the average manager of mutual funds, hedge funds, and private equity has added no value to, and even subtracted value from, fair benchmarks.

When building portfolios in

chapter 6, we noted that our framework should also be used to build better benchmarks. We used our return equation to evaluate the merits of three different indices: the RAFI U.S. 1000 Index, the S&P Equal Weight Index, and the Max Diversification USA Index. We put the return of these indices on the left-hand side of our return equation, and market, size, value, and momentum as factors on the right-hand side:

Rproduct = Rf + α + βmarketFmarket + βsizeFsize

+ βvalueFvalue + βmomentumFmomentum + ε.

Of course, factors can and should vary depending on the product being evaluated. Management should run such regressions and evaluate the product accordingly. For instance, they can prefer their active managers to have low exposures βmarket and βsize to the market and size factors, but high exposures βvalue and βmomentum to the value and momentum factors.

The idea is to better assess a manager’s worth. Use of multifactor-based benchmarks helps explain investment performance and better segregate excess performances due to α and exposure to risk factors. A fund manager can add value by outperforming a set of risk factors, that is, by having a high estimated α. He can also add value by appropriately timing his exposures to the different risk factors. Thus, even if managers do not report their performance to Management using a multifactor approach, Management should request the data that would allow for this analysis. Again, although a positive α is preferable, an investor can be satisfied to achieve a balanced exposure of risk factors at a reasonable cost unless it does not want to expose itself to some of these factors.

It is unusual for managers to use multifactor benchmarks, at least in their reporting to Management. First, it adds an element of complexity to the client reporting, but it also demystifies some of the reported sources of excess performance. Many traditional managers would be uncomfortable with this “transparency.” For example, we witnessed the case of an institutional manager using a combination of cash and equity to benchmark their value strategy. The rationale was that as the tilt toward value stock lowered the volatility of the portfolio, a proper benchmark was a watered-down market portfolio, say 85 percent allocated to the market portfolio and 15 percent allocated to cash. This is a badly designed benchmark for two reasons. First, weighting the market portfolio in the benchmark is not necessary. Running this regression will automatically assess the level of market risk in the portfolio through the estimated βmarket. Second, the value risk factor needs to be included in the analysis, otherwise the value tilt will be misconstrued as α. We are interested in assessing whether the proposed value strategy is good at combining the market and value risk factors, is good at picking particular stocks that will outperform these two factors, or both. Using an 85/15 benchmark is like using a misspecified return equation and assuming arbitrary values for the factor exposures.

The following are examples of potential factors that could be used to design benchmarks such as:

• Private equity: Market (Equity) + Market (Bonds) + Liquidity + Credit

• Corporate bonds: Market (Bonds) + Credit

• Value equity: Market (Equity) + Value

It is unlikely that most managers would use a multifactor-based approach to report their own performance unless it is specifically requested. A first step is for Management to perform their own internal analysis and implement it among managers. It would certainly change the nature of the discussion between managers and Management and help reduce the issues of overclaiming and agency.

Learning to Be More Patient

Sir John Templeton said, “It is impossible to produce a superior performance unless you do something different from the majority.” However, it may take much longer than investors expect to increase the likelihood of outperforming an index or specific target. A three-year track record is far from sufficient to judge managerial expertise.

There are also other implications. Management tends to fire a manager after a few years of underperformance. Assuming we truly understand the investment process of the manager and are comfortable holding the strategy on a long-term basis, we should be more concerned with the performance of our portfolio of managers than with the performance of any single manager. In a study of U.S. equity managers done by a consulting firm, 90 percent of top-quartile managers over a ten-year period encountered at least one thirty-six-month period of underperformance. For 50 percent of them, it was five years.

32 Therefore it would be impossible to maintain a long-term investment philosophy if we question the relevance of owning each manager that underperforms for a few years. Firing managers that underperform for a few years without consideration for other factors is akin to not properly rebalancing a portfolio or to buying high and selling low. Retail investors underperform because they buy into rising markets and sell into declining markets. Most of them do not have a process to manage their emotions. It is difficult to maintain a smart long-term investment approach without a proper understanding of the investment process of our managers.

In a 2014 interview, Seth Alexander, Joel Cohen, and Nate Chesley of MIT Investment Management company talk about their process for partnering with investment managers for what they hope will be several decades and how this can be achieved.

33 They make three statements that should resonate with our discussions in this book. First, great investors are focused more on process than outcomes. Of course, the intent is still to outperform in the long run, but they do understand that even the best managers and the best processes can have a mediocre year and three to four years of underperformance. Second, great managers do not have a cookie-cutter approach to investing or try to cater to what they think allocators want; they spend time tailoring their investment approach to what works for them. Hence both great investors and managers must have convictions in the processes. Finally, they state Jeff Bezos who often mentions how if your investment horizon is three years, you are competing against a whole lot of people, but if your time frame is longer, there is a world of other possibilities. Only with a long-term horizon and patience can we truly start emphasizing the importance of process.

Raising the Level of Knowledge in Our Industry

There is a wedge between the state of knowledge in academia and industry practices in the asset management industry. Consider two of the most important developments in the financial literature over the last seventy years: portfolio diversification by Harry Markowitz in 1952 and the capital asset pricing model (CAPM) by William Sharpe in 1964.

The first paper allowed us to understand that portfolio volatility can be reduced for a given level of expected return through diversification, hence increasing compounded returns. The second showed us why risk should be divided between its systematic component (the market), which is compensated by a market risk premium and a nonsystematic component that is unrewarded because it is diversifiable.

Many people dismiss these contributions in the industry. Mean variance investing as described in the first paper is plagued with estimation issues, and naïve implementation is a sure way to lose money. The one-factor CAPM has a poor empirical record as there are other risk factors that are remunerated.

But these papers are practically relevant, and their insights are crucial in a conversation on investments. The difficulties in measuring expected returns, volatilities, and correlations that make the Markowitz portfolios hard to implement in real life can be addressed with different solutions, as we discussed in

chapter 6. But most importantly, its insight that diversification is the only free lunch in finance is crucial and underpins many existing investment solutions.

The CAPM is derived using a set of assumptions that are not entirely realistic. Similar to the case of Markowitz’s work, subsequent work relaxes these assumptions and provides better performing asset pricing models. But most importantly, the model shows each investor allocating their portfolio results in a risk factor being remunerated with positive expected return and other risks not being remunerated. Extensions of this paper similarly show the economic underpinning for other risk factors to be remunerated in financial markets. This insight allows us to understand that some factors will be remunerated and other types of risk will not.

These insights are crucial in examining the worthiness of new products. What is their source of performance? Are they properly diversified? What are the investors’ preferences and market structure that lead to this source of performance being compensated with positive returns?

Even though these papers are several decades old, their insights are often misunderstood, and we are still limited in our ability to explain simple concepts and use standard terminologies when explaining investment strategies to many investors. Continuous and relevant education is essential. Without it, we will keep repeating the same mistakes, rediscovering old investment concepts through different forms, and making investment decisions based on imperfect information. The responsibility should not rest solely on asset managers to better communicate their strategies and know-how, but also on Management to improve their general knowledge of subject matter. We hope that this book has contributed to this end.

Concluding Remarks

It is said that investing is an art and a science. The science part concerns an understanding of performance drivers and methodologies. We live in a multifactor world that requires us to identify what is relevant, what is not, and how to integrate relevant factors. We must also convince investors and their agents of the validity of our approach, and therein lies the “art.”

Many investors remain unconvinced of factor-based approaches. We often hear investors say that factor tilt portfolios have considerable risk relative to market capitalization–weighted portfolios. They have underperformed over many periods and entail greater transaction costs.

However, this reasoning is based on the assumption that we live in a single-factor world and that the market factor is always the appropriate benchmark for each of us. It also assumes that the market is the most return/risk efficient portfolio for any investor. However, which is more likely: that we live in a single-factor world or that we live in a multifactor world? That a combination of the market factor and some other riskless asset leads to the most efficient allocation for all of us or that specific combinations of factors could lead to more efficient and appropriate portfolios for some of us?

The key to making good decisions involves “understanding information, integrating information in an internally consistent manner, identifying the relevance of information in a decision process, and inhibiting impulsive responding.”

34 When luck plays a small role, a good process will lead to a good outcome. But when luck plays a large role, as in the investment management industry, good outcomes are difficult to predict, a poor state of affairs when patience is in short supply. This book is entirely about the process of making good investment decisions in the long term for patient investors. Implementing a good investment process requires a body of knowledge. Unfortunately, this knowledge may be tainted by biases and conflicts of interests in our industry. Even if we understood the requirements of efficient processes, there are significant implementation challenges. We hope this book provides a step in the right direction and contributes to a productive conversation on investment.