Figure 15.01: Building 9, Period 1 at 1:200.

All four barracks in the retentura, Buildings 9–12, were investigated by Daniels in 1977–9, with Building 12 in the north-east quarter being interpreted as a stable block whilst 9, 10 and 11 were envisaged as barracks for the soldiers. The northern pair, 9 and 12, were re-examined by Tyne and Wear Museums in 1997–8, which resulted in a significant shift in our understanding not only of those two structures, but, by analogy, of all four retentura buildings, which are now interpreted as stable-barracks, a type not previously recognised on the British frontier.

The account presented below provides only an outline summary of the earliest timber and stone phases of the barracks 9 and 12, focussing on the associated features which were identified in the 1978 and 1979 seasons, along with full treatment of the Daniels evidence relating to 10 and 11. For a fuller description of the layout of barracks 9 and 12 the report on the excavations conducted by Tyne and Wear Museums should be consulted (Hodgson 2003, 37–90).

Grid squares: D12, D13, E12, E13, F13, F14, G13, G14, H13, H14

Excavation of Building 9, the most north-westerly of the four retentura barracks, was initiated in 1977, but mostly undertaken during the 1978 season. Much of the building had been removed by post-Roman disturbance and robbing. Nevertheless a complex structural sequence was apparent, with multiple phases, many surviving only fragmentarily. As a consequence of this fragmentary survival, the structural evidence posed the kind of interpretative problems more commonly faced when examining the results of nineteenth-century excavations, for example multiple intersecting walls which were difficult to form into a coherent pattern and which were rarely relatable to a clear sequence of extensive or wellpreserved floor surfaces. These problems are reflected in the research archive with successive redrafts of the phase plans, sometimes involving radical shifts in thinking.

Re-excavation by Tyne and Wear Museums in 1997– 8, as part of the Segedunum Project, has substantially revised our understanding of this structure. Like its three counterparts in the retentura, 10, 11 and 12, Building 9 is now interpreted as a cavalry barrack block of a type first proposed by Sebastian Sommer (1995), designed to house a full turma of around 30 men and their horses. The four blocks would thus have been able to accommodate an equitate cohort’s full complement of c. 120 cavalry.

In its primary, Hadrianic, form Building 9 was built entirely of timber. No sectioning to find timberbeam slots underneath the main external walls was undertaken in this building in 1978 (in contrast to Building 12 where such features were identified), but slots for external timber walls were located in 1997–8. Together with the evidence from Building 12, this suggests that all the barracks in the retentura, and probably in the fort as whole, were built of timber originally.

As many as nine slots for the internal timber partitions separating one contubernium from another were uncovered by Daniels, mostly by means of small spits excavated at the end of the 1978 season. It is difficult to determine whether the individual partitions were associated with the timber barrack or its stone successor as it is apparent that the footprints of the two ranges were very similar. Together, however, these partition slots give nine contuburnia, plus the officer’s quarters situated at the west end of building. The contubernia were each divided into front and rear rooms (clearly demarcated by a surviving partition slot in the most westerly contubernium, as recorded in 1997–8), the former floored with flagstones and the latter with beaten clay, and opened to the south, facing the parallel block, Building 10, across a 4.00m wide street (Alley 5). A centrallyplaced, elongated pit was recognised in the southern half of each contubernium during 1997–8, leading to the reinterpretation of Building 9 as a cavalry barrack block. The pits, it is argued, were intended to collect waste from stalled horses. The block accommodated a full turma. Each contubernium would have housed three troopers, with their horses stabled in the front (southerly) rooms of the contubernia and the men plus most of their equipment in the rear rooms. It is significant that the cavalry contubernia in the retentura barracks all lacked the distinctive type of internal partition that separated the front room from a side access corridor leading from the front entrance to the back room, which were recognised in the infantry barracks in the northern part of the fort and at South Shields. In a cavalry barrack such partitions would simply have impeded access for the horses into the front room.

Only a few features associated with the timber barrack were uncovered during the Daniels excavations. These can be identified by reference to the phase plans and description presented in the 1997–8 excavation report. The clearest evidence was seen in Contubernia 1 and 2 where successive floor levels were preserved. A sequence of three stone floors was revealed in the south room of Contubernium 1. Only a very small area of the lowest flagging was seen, consisting of fairly small irregular slabs (E13:35), and it is questionable whether this represented an actual floor surface or simply a construction level. A more extensive area of the next level was revealed, comprising regular, rectangular flagstones up to 0.70m × 0.40m in size (E13:34), very similar to some of those used in the floor belonging to the subsequent phase of Contubernium 2 (E13:14). The western edge of this flagging clearly respected a north-south aligned wall slot (E13:38, TWM 8534) which was positioned only 0.70m from the stone wall (E13:17) that separated the officer’s quarters from the contubernia after the barrack block was rebuilt in stone, too close for the wall and slot to have functioned at the same time. Both the slot and, by association, the flagging must therefore have belonged to the preceding timber phase. They were overlain by a further surface of more irregularly shaped stones (E13:23) which evidently represented the floor of the subsequent stone barrack. Similarly, two successive clay layers were recorded in the north room of Contubernium 1, the lower of which (E13:48) probably represented the floor level associated with the timber barrack phase. Up to three clay levels were noted in the north room of Contubernium 2 (E13:47/F13:49, E13:41/F13:36, E13:13). The lowest (E13:47, F13:49), again, must relate to the primary timber barrack. In Contubernium 3, the lowest clay surface (F13:50) was covered by a layer of daub (F13:45), which probably derived from the demolition of the timber barrack. This was in turn overlain by another clay floor (F13:35), presumably associated with the replacement stone block. Further east, a flagged floor (G13:25, TWM 7779) in the southern part of Contubernium 6 was also primary as was the assocated clay level to the north (G13:26). Re-excavation in 1997–8 showed that this flagging respected the edges of 2.20m long waste pit (7795). It was cut through by pitched stones (G13:36, 8542) which lined the replacement sump in the subsequent stone barrack phase, and overlain by secondary flags probably associated with the stone barrack block (G13:37).

Two features in the north room of Contubernium 1 were overlain by the secondary clay floor surface (E13:42) and should therefore be primary. A stone setting (E13:51) occupied a position against the east side wall characteristic of hearths. Like similar features in the hospital building and Building 1, this was interpreted by the excavators as a coal scuttle. These structures are perhaps more plausibly viewed as a brazier stands. The stratigraphic position of this feature beneath the secondary floor but set right next to partition E13:37 would suggest the latter too belonged to Phase 1. In the centre of the north room, a line of small stones (E13:52), some of which were tipped downwards, was initially interpreted as one side of a possible drain, but the actual structural significance of this feature remains very uncertain. It was 2.10m in length and was recorded as cutting the Phase 1 clay floor.

In the officer’s quarters, the position of an eastwest partition was indicated by a trench (D13:59) and three post-holes (D13:60, 61 and 64), and was shown to extend further westward in 1997–8 (a post hole was marked on site plan P145 here, but not allocated a context in the Site Notebook). This defined the southern edge of a clay floored room (D13:57) which was furnished with a hearth marked by a rectangular patch of burnt red clay (D13:58). The floor was composed of rather patchy pink clay with much grey, sticky, silty material.

On the south side of the partition line, further to the west, an irregular U-shaped feature (D13:72) may also belong to this phase. It was formed by shallow gulleys cut into the clay beneath the stone floor of the Phase 2 barrack (D13:65, 71). The full extent of this feature had been truncated by the later stone partition wall (D13:04) to the south. Its purpose is unclear. A Dressel 20 amphora base uncovered in 1997–8 was set in a circular cut, apparently positioned within the western gulley and might be associated with this feature although this cannot be confirmed as its positioning could be coincidental (base: TWM 8266; cut: 8273; cf. Hodgson 2003, 100 & fig. 67, where it is assigned to the chalet period – TWM Period 4). The amphora was not specifically identified in the 1978 context records though sherds belonging to the vessel were clearly shown on site plans P154 and P157, incorporated in and beneath stone floor D13:65/71. The vessel was sealed beneath the chalet period floor (D13:48) and must predate that period. The green silt contained in the amphora base indicated the vessel may have been used as a urinal.

FINDS

Decorated samian: Flavian-Trajanic (no. D31; E13:20)

Stone: throwing stone (nos 12, 113, E13:38)

Stone: throwing stone (no. 71, E13:34)

The make-up layer in the gap between Contubernium 1 and the officer’s house (E13:20) produced only a single sherd of pottery, from a Flavian or Trajanic samian bowl. The clay floors in Contubernia 1 and 3 produced four sherds, consisting of a secondcentury mortarium, two second-century BB1 flatrimmed bowls and a sherd of Flavian or Flavian-Trajanic samian (E13:48, F13:50). The clay floor in Contubernium 6 produced a sherd of samian and a sherd of BB2, both of Antonine or later date (G13:26).

The material in the levels associated with the timber barrack block is for the most part consistent with a Hadrianic construction date. The BB2 and Antonine samian in clay floor G13:26 may represent material trampled into the floor before its replacement.

The external walls of the barrack were rebuilt in stone, probably in the mid-late second century. Their state of preservation when revealed in 1978 was poor. Most of the north wall of the building was destroyed by modern disturbance, especially by modern sewage pipe trenches. Only fragmentary remains of the foundations of the east wall survive. Slightly more of the west wall was intact. The south wall was the best preserved of the four, surviving several courses high in places. It was 0.65m–0.70m wide and constructed with fine grained, orange-grey, sandstone blocks facing a rubble core, probably originally clay-bonded. The clay and rubble foundations varied in width from 0.70m (e.g. E13:18) to 1.10m at the south-west angle of the building (D13:44). Certain parts of the wall appear to have been rebuilt, i.e. E13:12. The stone barrack was 46.00m in length and was wider at the west end (8.20m), where the officer’s quarters were located, than at the east end (7.80m). The range of nine contubernia occupied 34m of the total length and their internal dimensions from front to back wall ranged from c. 6.20m (east end) to 6.80m (west).

It is not always possible to determine whether the internal features identified in 1978 belonged to the primary timber phase, which Daniels’ team were unaware of, or to the subsequent stone rebuild. The internal arrangements initially remained very similar, with timber partitions continuing to divide nine contubernia one from another after the rebuilding. Moreover the footprint of the successive contubernia ranges was so similar that, with one or two exceptions it was very difficult to determine which of the two phases the individual partition slots should be assigned to.

The evidence for these partition slots was fairly fragmentary, the slots being identified in frantic last minute digging of small spits at estimated contubernia distances. They vary from changes in the colour or texture of the clay, to stones on edge (presumably to support a partition), to the edge of a flagged area and even a ballista ball/throwing stone (G13:35). It was suggested by the excavators that this stone had perhaps rolled into the slot left when the partition was removed, but three were found in slot E13:38 and others were revealed in similar contexts in other barrack blocks which implies their presence was the result of a deliberate action, though its purpose – structural, backfilling or otherwise – is unclear.

Each contubernium was divided into north and south rooms. As in the primary timber phase, the southern rooms were floored with stone flagging, whilst only beaten clay floors were uncovered in the northern ones (although it is conceivable that the clay served as a bedding for wooden floorboards with holes cut in them for the hearths). In some places traces of post holes were identified (e.g. E13:45, 46, F13:37 and G13:29, 30), roughly at the northern limit of the stone floors, which possibly formed part of the east-west partitions separating the two rooms (such east-west partitions were found in Building 1 Phase 1 and also in Barracks XIII at Housesteads and at South Shields). The allocation of these post settings to the stone barrack rather than its timber predecessor is based on the recorded observation that they cut the uppermost clay floor levels. In Contubernium 2, flagging E13:34 – more of which was uncovered in 1997–8 (as TWM 7513) – apparently terminated some 0.70m–0.80m before the line of the east partition wall (F13:38), suggesting the existence of a side walkway, perhaps floored with timber boarding, leading from the front entrance in the south wall to the back room. The restriction of the flagged floors to the south part of the contubernia and location of the hearths only in the north rooms confirms that the two rooms had different functions, with the north rooms forming living areas for the troops whilst their mounts were stabled in the south rooms.

Figure 15.03: Building 9 viewed from the west showing flagged floors – E13:34 in Contubernium 1 (Period 1), E13:14 in 2 and F13:15/27 in 3 (Period 2/3).

Figure 15.04: View from the south of Period 1 flagged floor G13:25 in the south room of Contubernium 6 and the protruding slab wall of the Period 2/3 urine sump (G13:36) at the extreme left foreground. In the background, beyond the Period 4 spine wall, can be seen at top left hearth flag G13:21 sitting on Period 2/3 clay floor, with flags G13:23 belonging to the Period 2/3 floor of Contubernium 7 to the right.

In Contubernia 1, 2, 3 and 6, the floor levels which were associated with the stone barrack could be identified on the basis of their relative position in the sequences of floors revealed here (Figs 15.03, 15.04). The upper flagging in the south half of Contubernium 1 (E13:23), ran over the top of the earlier flagging (E13:34) and the slot which formed the west wall of the primary contubernia range, and extended towards the stone wall which separated the officer’s quarters from the contubernia, indicating that Contubernium 1 was enlarged to the west when the barrack was rebuilt in stone. This flagging was presumably contemporary with the uppermost (E13:42) of the two successive clay floors recorded in the north room. Similarly the upper clay levels encountered in the north rooms of Contubernium 2 (E13:41/F13:36, E13:13) and Contubernium 3 (F13:35) should relate to the stone barrack block not its predecessor, with the clay floor in Contubernium 3 seen to be covering a spread of daub (F13:45) which probably derived from the demolition of the primary partition walls. The flagging in this contubernium (F13:15/27) had subsequently subsided into the underlying urine sump. Two levels of clay flooring were identified in Contubernium 2. In Contubernium 6, the primary flagged surface (G13:25) was overlain by a stone floor (G13:20, 37) associated with the secondary barrack and cut by the upright slabs (G13:36) lining the west side of the urine sump associated with this phase (Fig. 15.04). To the north, the corresponding clay floor (G13:24) was noted, again overlying its primary counterpart (G13:26). A further sandy clay layer (G13:19) covered all of these surfaces and probably represented makeup or a floor level for the subsequent chalet range.

The surviving evidence for the internal furnishings of the contubernia was limited. Hearths were revealed in the northern rooms of Contubernia 2, 3, 4, 6 and 7 (F13:39, 40, 41, G13:21, 22) comprising small patches of burnt red clay and/or single flagstones sometimes surround by spreads of coal. These were often set against the side or medial partition walls of the contubernium. One of the hearths (F13:40) comprised a single flagstone (F13:42) overlain by a spread of coal, rather than burnt clay or ash. This suggests the fire was not set directly on the ground and the feature might therefore conceivably be interpreted as a brazier stand rather than a hearth proper. Several post holes towards the north ends of the contubernia (e.g. F13:47–48, G13:27–8) may also relate to the internal arrangements of the early barracks in some way (F13:47 cuts upper clay floor F13:35 in Contubernium 3; relationship of F13:48 to equivalent clay floor F13:44 in Contubernium 4 is uncertain, but G13:27–8 also cut upper clay levels).

There was evidence for the location of a doorway through the front wall of Contubernium 4, in the form of a 0.90m wide section where only a single heavily worn course of the wall footings was present (F13:32). One of these stones, though displaced, preserved a pivot hole and a groove perhaps worn by the door leaf. The doorway was positioned at the western edge of the contubernium frontage.

The officer’s house measured 11.80m by 8.20m and was separated from the range of contubernia by a 0.70m wide stone wall (E13:17). Two possible entrances to the officer’s quarters were identified, one in the south wall near the building’s south-west angle and one in the middle of the north side (D13:47). An east-west medial wall (D13:04, E13:26) divided the house into two unequal parts, the northern room being the larger. The western half of this wall had later been entirely robbed out (D13:16). When it was first excavated in 1978 Daniels was uncertain whether the medial wall was an original component of the stone-built quarters. Internal stone walls of this kind were not a feature of officer’s quarters in other barrack blocks of this period in the fort, timber partitions generally being used instead. The 1997–8 excavators assigned the wall to the following chalet-barrack phase (Fort Period 4) and restored a timber partition in the initial stone barrack phase (Period 2/3), which was represented by a single surviving post hole (TWM 8237, cf. Hodgson 2003, 51 fig. 37, 58, 98–9). However, the relationship of the wall to the lowest stone surface (D13:65, 71) in the north-western room suggests that it did belong to this overall period of the stone barrack (see below). The junctions between this wall and the east and west walls of the officer’s house have not survived so the possibility that it represented a secondary insertion or sub-phase rather than an original feature, cannot be ruled out.

The northern room was divided by a north-south aligned wall. Only a single course of the east face of this wall survived (D12:51, D13:49), backed by a clay deposit (D12:52, D13:50), giving the surviving remains a rather unusual aspect, similar to the side of a water tank. At the north end of the wall, a line of three blocks immediately to the east may have represented some form of stepped threshold (D13:47), though set well inside the line of the building’s north wall.

A large stone-lined urine-pit (D13:46), measuring internally 2.45m by 0.45m–0.50m, was constructed in the north-west room. This pit is probably a more elaborate version of those recently found in the front rooms of the contubernia, appropriate to an officer’s accommodation, and was presumably designed to hold the waste from the decurion’s horses. The sides consisted of large slabs set on edge sloping down into the bottom of the pit (see Fig. 15.05), giving an overall depth of 0.50m–0.60m. The pit’s construction trench (D12:59) was observed on its north side, cutting into a grey clay spread (D12:60, D13:66 – a timber barrack level?), which in turn covered a grey clayey silt layer (D12:61) interpreted as the ‘old ground surface’ (prebarrack?), overlying the natural subsoil. An overflow drain (D13:52/53) ran from the west end of the latrine southward along the inner face of the west wall (see Fig. 15.06), exiting at the south-west angle of the building (D13:62). This was found to contain a greengrey sandy silt (D13:70) including much pottery and glass. The remains of a stone surface survived to the north and south of the pit (D12:58, D13:65, 71). This was composed of small rough sandstones (D12:58, D13:71) and was suggested this might represent the sub-floor for timber boarding. On the north side of the urine pit the stone surface was observed to directly overlie the fill of the pit’s construction trench. Further east this floor level took the form of very worn and cracked flagstones (D13:65, TWM 7895), which incorporated three facing stones belonging to the lowest course of the medial wall (D13:04). The facing stones exhibited the same wear pattern as the flagging (D13:65) and lay at virtually the same level, demonstrating there must have been a doorway through the wall at this point which was in use at the same time as the flagstone surface.

The Dressel 20 amphora base set in a circular cut in the north-west room may belong to this phase rather than the primary timber barrack. The amphora base was uncovered during the 1997–8 excavations (base: 8266; cut: 8273; cf. Hodgson 2003, 100 & fig. 67, where it is assigned to the chalet period – TWM Period 4). The amphora was not specifically identified as a feature in 1978 though sherds belonging to vessel were clearly marked on site plans P154 and P157, in and beneath stone floor D13:65/71. The amphora setting and sherds were all sealed beneath the chalet period floor (D13:48) and must predate that period.

The south side of the officer’s house was divided into a range of three rooms. In the south-west corner, a flagstone surface (D13:37) was observed to spread directly over the pink clay foundations of the building’s south wall (D13:44/45), suggesting there was another entrance at this point. This surface was shown to extend further northward in 1997–8 (TWM 7701), forming a flagged lobby which encompassed the entire south-west corner of the building and was bounded on the east side by a timber partition slot (8234, cf. Hodgson 2003, 51 fig. 37, 58).

The central room of the south range was divided off from the next room by a stone wall (D13:21) extending south from doorway into the northern part of the house. The dimensions of the central room were c 3.00m (east-west) by 2.20m (north south). The room occupying the south-east corner measured 4.00m by 2.20m and was floored with stone flags (D13:19, E13:32) which abutted the two surviving facing stones of wall D13:21. Just outside the south wall of the building a further line of flagging shown on site plan P145 was re-exposed in 1997–8 (TWM 7561).

Figure 15.06: Stone channel D13:52/53 leading away from the west end of the urine sump, from the north.

Along the north side of the building parallel to the wall of the later stone barrack, lay a stone-lined drain or gutter (E12:18, F13:13, G13:05). Originally this probably ran the full length of the building, but, like the north wall, it had been badly damaged by modern sewer trenches and only a few fragments of its central section, spanning a distance of 16m, were revealed. The channel varied between 0.20m and 0.25m in width and was filled with a light brown sandy silt, whilst the side walls were composed of at least two courses of sandstone blocks, although in places only one course survived. The drain was set into the lowest cobbling of the via quintana revealed in 1977–8, which was composed of orange gravel, crushed sandstone and clay (E12:21, F13:24, G13:04). It should therefore be contemporary with the occupation of the stone barrack and may even initially have been constructed at the same time as the primary timber block.

FINDS

Coin: Domitian, 81–96 (no. 20, E13:23)

Iron: chain (no. 36, E13:42), stud with copper alloy sheet (no. 53, E13:24)

Samian stamp: c.125–50 (no. S35, E13:13)

Copper alloy: chape (no. 220, F13:36), stud (no. 231, E13:41), mounts (no. 240, F13:36)

Iron: spearhead (no. 10, E13:41)

Pottery: disc (no. 51, E13:13)

Iron: studs (nos 45–6, F13:50)

Iron: clamp (no. 42, F13:44)

Stone: throwing stone (no. 36, G13:35)

Copper alloy: plate (no. 307, G13:24)

Decorated samian: c.125–40 (no. D67, G14:17)

Glass: bead (no. 45, G14:17)

Mortarium stamp: 110–40 (no. 19, D13:71)

Glass: cup (no. 32, D13:70), bowl (no. 41, D13:70), window (no. 42, D13:50)

Coin: Crispina, 180–3 (no. 115, D13:71)

Bone: pin rough-out (no. 23, E12:18)

The walls produced only four sherds of pottery, including a sherd of late second-century samian (F14:19) and one sherd of late second-century or later BB2 (E12:13).

The clay floors in both the officer’s house and the contubernia produced BB2 and a small amount of allied fabrics of the late second-century or later. The stone floor in Contubernium 1 produced only about 15 sherds, mainly BB1 and locally produced grey wares plus a sherd of Hadrianic or Antonine samian (E13:23). The occupation material over this floor was different in composition, being made up of almost equal quantities of second-century locally produced grey wares and BB2 of the late second century or later and only a single sherd of BB1 (E13:24).

The intermediate clay floor in Contubernium 2 was dominated by sherds of BB1 cooking pots (F13:36), and there was another BB1 vessel, a flatrimmed bowl, in the upper clay floor. However, the upper layer also contained the remains of two Nene Valley indented scale beakers, each almost one-third complete, dating to the third century. (E13:13, fig. 22.15, nos 77–8). The amount of pottery from the floors in the other contubernia was small, mostly consisting of late second-century or later material, but with a few sherds of third-century Nene Valley ware in the flagged surface in Contubernium 3 (F13:15) and the clay floor of Contubernium 6 (G13:24).

There was a single sherd of Trajanic or early Hadrianic samian alongside sherds from two Lower Nene Valley mortaria dating after 230 and one dating to the late third or fourth century (E12:18). There were no surviving coarse wares.

The use of stone dividing walls in the officer’s house of Barrack 9 Phase 2 is anomalous. Nothing similar was encountered in the equivalent phase of the other officer’s quarters investigated at Wallsend. Yet the stratigraphic evidence provided by the Daniels excavations to support this association appears convincing. Most crucial is the close relationship recorded between the worn threshold through the main, east-west aligned, partition wall and the Phase 2 stone floor to the north (D13:65/71, D12:58). This floor must have been associated with the initial phase of the stone-lined latrine sump (D13:46) and its outlet (D13:52/52). It was clearly too low to have been associated with the chalet period, when the height of the sump’s side walls was raised well above the level of D13:65/71 and a new floor was laid (D12:39, D13:48). Secondly the lower flagged floor (D13:19/ E13:32) in the south-east room of the house abutted the south side of the wall and was evidently broadly contemporary with it. This flagged surface extended as far south as the line of the south wall of the house, but did not extend over the robber trench for that wall (D13:35), unlike the chalet period flagged floor above (D13:20/E13:31), which obviously post-dated the demolition and removal of the redundant south wall.

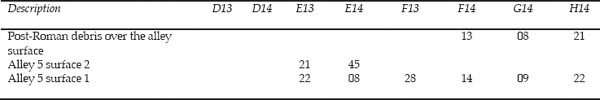

Buildings 9 and 10 were separated by a 4.00m wide street (Alley 5). Two phases of metalled surface were recognised here (see Table 15.01). The lower surface, which was exposed along the full length of the alley, consisted of small, well-laid sandstone cobbles, generally worn smooth (E13:22, E14:08, F13:28, F14:14, G14:09, H14:22). Quantities of broken amphora were found on this surface in one area (E14:08). The cobbling dipped slightly along the north side of Building 10, the small stones here showing less sign of wear (E14:15=F14:30). The excavators were unsure whether this 0.35m wide depression formed some kind of gutter or a construction trench for the north wall of Building 10 and whether the cobbles exposed in the bottom represented an earlier road surface. A second layer of metalling was recorded in one small area and comprised worn small-medium sized cobbles (E13:21, E14:45). Elsewhere the lower cobbling was directly overlain by the walls of Chalet Range 9 (for example the walls of Chalet U sat on top of F13:28 and F14:14). No surfaces survived which post-dated the construction of the chalets and belonged to Fort Period 4 or later.

Table 15.01: The cobbled street surfaces of Alley 5 between Buildings 9 and 10

FINDS

Samian stamp: 125–50 (no. S7, F14:14)

A total of 52 Dressel 20 amphora sherds, and two samian sherds of Hadrianic and Hadrianic or Antonine date were found on the lower road surface (E14:08, F13:28, F14:14). All but one of the Dressel 20 sherds derived from E14:08 and this may represent a single amphora smashed on the road.

Grid squares: D14, E14, E15, F14, F15, G14, G15, H14, H15

Very little of Building 10 survived (see Fig. 15.07), even by comparison with Building 9 its neighbour to the north, when it was excavated by Daniels in 1978 (as with Building 9, initial clearance of overburden took place in 1977). The south-west corner in particular, including much of the officer’s quarters, had been entirely removed by modern cellars. Of the outer walls not more than two courses of the superstructure, including the wide plinth course, remained at any point. However their foundations survived sufficiently extensively to establish clearly the outline of the second-century barrack. Building 10 was not included in the area re-excavated by Tyne and Wear Museums for the Segedunum Project in 1997–8, but the overall conclusions with regard to the retentura barracks derived from that programme nevertheless have important implications for our understanding of this barrack block’s development as well.

The primary building was initially interpreted by Daniels as a stone walled barrack block with nine contubernia separated by timber and wattle and daub partitions. However, the 1997–8 excavations of Buildings 9 and 12, demonstrated that these two barracks were both constructed entirely of timber in their initial phase and each comprised a row of nine contubernia designed to accommodate a cavalry turma, with a separate officer’s house standing at one end. It is inherently probable that the same was true of Building 10 and that it was only later rebuilt with stone outer walls and a stone dividing wall separating the officer’s quarters from the row of contubernia. Indeed, the surviving remains provided clear evidence that such was the case. Traces of eleven or twelve timber partitions were uncovered by Daniels in the contubernia, many of which could not be fitted comfortably into the layout of the stone barrack block and must instead have been associated with an earlier timber-built phase.

The timber or wattle partitions separating the contubernia were represented by a series of eleven linear slots, distinguished by fills of gravel chippings or differently-coloured clay. These fills probably represent construction debris deposited when the timber partition panels were dismantled and removed. One pronounced soil change (F14:56) was also interpreted as the edge of a partition, although this may now be questioned. Most of the slots were found during last minute excavation of small spits at likely intervals and they were numbered from 1 to 12, running from west to east. They were planned (cf. archive plan P162) and assigned context numbers, but those examples in the western and central parts of the block were not recorded in detail in the site notebooks, so their stratigraphic relationship with the successive clay floors or make up levels is often uncertain. Despite the predictive nature of the investigative methodology, too many slots were discovered at too close a spacing to fall into a simple, single-phase, if it is assumed that each example divided one contubernium from another. The partitions must have related to at least two phases of barrack contubernia which evidently had significantly different footprints along their east-west axis. This forms a marked contrast with Building 9 where it is clear that the two phases of contubernia occupied virtually identical plots and it was correspondingly difficult to distinguish one phase from another.

Figure 15.08: Building 10, Period 1 with the outline of the later stone barrack shown for reference at 1:200.

Initially two groups of slots were differentiated in Building 10, based on the depth that they cut into the underlying deposits, with Slots 1, 3, 5, 8, 12 falling in one group and 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11 in the other, the second group cutting much deeper than the first. It would be logical to interpret the deeper slots as representing an earlier phase than the shallower examples, with the former representing part of a primary timber barrack whilst the shallower slots were associated with the stone rebuild. However, this was evidently not the case. Slot 1 (E14:50), one of the shallower examples, was only c. 1.40m from the stone wall separating the officer’s quarters from the contubernia, too near to be contemporary with it, whereas the much deeper Slot 2 (E14:51) is positioned at about a contubernium’s width away from the stone wall.

A more reliable method of determining which partitions were associated with which phase is to examine the spacing of the slots. On this basis, slots 1, 3, 8, 10 and 12 could belong to the earlier timber phase. As noted above, there is only a narrow gap between slot 1 and the east wall of the officer’s quarters, whilst Slot 12 (H15:29) is too close (2.40m) to the line of east wall of the stone barrack block to create a full-sized contubernium. Several missing partitions must be restored in the centre and east end of the range to complete the series. A second series, comprising slots 2, 4, 5, 7, 9 and 11, fitted reasonably comfortably within the footprint of the later stone-walled barrack block, their spacing beginning with the wall separating the officer’s quarters from the contubernia (E14:46) and ending neatly at the east wall of the building (H14:46, H15:21). They should therefore belong together in association with this phase. In contrast, Slot 6 (F14:56), which was represented by a change in the colour of the clay flooring with chippings on the east side, doesn’t fit with either layout and may well represent the trace of some other type of internal arrangement.

Some degree of confirmation for this two phase interpretation of the partition slots is provided by the relationship of Slots 3 and 4 (E14:52, 53) with the flagging in the southern part of the barrack (E14:38). Although it was not recorded as such in the site notebook, the flagged floor appeared to be made up of an upper and lower level of flags (cf. archive plan P147), presumably reflecting a later repair. Both levels were very patchy, but the lower ones did appear to respect the edge of the Phase 1 slot (no. 3) whilst the upper flags respected the later slot (4).

Slot 1 (E14:50) was shallow, with no depth to the chipping fill and no discernable difference between the colour of the clay in the fill and that of the adjacent clay floor. Slot 3 (E14:52) was shallower with a saucershaped cross-section. It lay 3.75m from slot no. 1, probably about the right distance for a contubernium’s width. Slot 8 (G14:30, G15:33) comprised a shallow, 0.30m wide strip of gravel chips containing some mortar. This may have marked the west wall of Contubernium 8. Slot 10 (G14:23, G15:29) was another deeper slot consisting of a visibly different-coloured strip of clay, but no gravel or chippings. Slot 12 (H15:29) was slight, shallow and gravel-filled. It is unclear how footprint of the Phase 1 contubernia range corresponded with that of Phase 2. If the officer’s house was a freestanding structure, as was the case in other barracks of this phase in the retentura, which were revealed more fully in 1997–8, Slot 1 might represent the west wall of Contubernium 1, the east wall of the officer’s house or, conceivably, the west wall of Contubernium 2, although one of the first two options is more likely.

An east-west partition slot (D14:33, E14:42) was uncovered towards the eastern end of the later Phase 2 officer’s house, along with three or possibly four post-holes for some kind of room divider (D14:34–35, E14:43). A fourth post hole (D14:36) was found to the south of the slot. All these features were cut into a layer of orange silty clay (D14:32, E14:37), which was the lowest level investigated in this area, and they could conceivably relate to the officer’s accommodation associated with the primary timber barrack, but too little evidence was recovered to form a coherent, overall picture in that regard and the possibility that they formed part of the initial arrangements in the stone officer’s quarters, instead, cannot therefore be excluded.

FINDS

Coin: Crispus, 321–4 (no. 182, G15:19)

Stone: throwing stone (no. 87, G14:29)

Copper alloy: ear-ring (no. 42, G15:20)

There were only two sherds of pottery from this phase, both from a second-century flagon in the clay floor of Contubernium 2 (E14:48).

Building 10 was rebuilt with stone outer walls and a stone dividing wall (E14:46) separating the officer’s quarters from the contubernia. At 45.00m in length the barrack was about a metre shorter than Building 9, and as a result did not extend quite as far west, whilst the full length of the contubernia range was 34.40m. The building’s width varied between 8.50 and 8.60m.

Although severely damaged, sufficient survived of the north wall to show it was of unusual construction (cf. F14:09 and G14:12). The core of the lowest course above the foundation was composed of small flat slabs to create a flat base, 0.85m wide, for the wall superstructure. The latter was noticeably inset, particularly on the outer face, and measured 0.75m in width (see Figs 15.10 and 15.11). At its east end several faced stones (H14:31) were linked to the east wall (H14:45) and its foundations were continuous with those of the east wall (H14:44). The construction of the latter was similar to that in the north wall with traces of a flat, thin base course between the clay and rubble foundation and the wall proper. Some trace of later, possibly chalet-period reconstruction was discernable midway along the east wall (see Chapter 16 below). The actual foundation measured between 1.00 and 1.05m in width.

Significantly, a narrower band of foundation material (H14:46, H15:21), apparently underlying H14:44, was seen particularly towards the south end of the east wall and in the bottom of modern drain trenches which cut its line. This was interpreted as the foundation of an earlier stone-walled phase of Building 10 and if so would imply that the flat plinth course belonged to a later reconstruction, the chalet phase being the favoured candidate. A degree of uncertainty existed over this interpretation, however. It is conceivable that the ‘earlier’ foundation simply represented the bottom of upper foundation H14:44, as suggested by one of the excavators (IDC). Furthermore the style of the north wall, with its good, clay-packed rubble foundation and its wide (i.e. Off-set), well-laid base course was quite distinct from the east and west side walls of all the chalets in this area which, while quite functional, were simple. None had any depth of construction let alone foundations. Two of these walls, F14:27, the east wall of Chalet AA, and F14:43, the west wall of Chalet Z, were said to have been bonded with the north wall, which would have made that wall contemporary with the chalets (Site Notebook entries F14:09 and G14:12), but examination of the site plan (P136) and photographs suggests this is far from conclusive and if anything would contradict this with the chalet walls apparently overriding the plinth course, but butting up against one surviving facing stone of the north wall. Accordingly it is more likely that the chalet side walls were simply keyed into the pre-existing masonry of the north wall, with rebuilding perhaps limited to that required to break the north wall of Building 10 into a series of separate chalet walls (Research Archive – Building Y Summary). Furthermore, if the narrower foundation H14:46 was indeed distinct from foundation H14:44 and therefore represented the initial stone phase, the flat plinth course must have represented a secondary reconstruction of the barrack prior to chalet phase.

The north wall of the officer’s quarters (D14:07) did show signs of rebuilding over part of its length, to form the north wall of Chalet AB and perhaps on more than one occasion (see below Chapter 16: Chalet AB). Significantly, the wall here lacked the flat plinth course noted elsewhere and the excavators distinguished two levels of foundation, though on what basis was not made explicit in the records. The upper layer, directly beneath the wall masonry, was described simply as angular rubble (D14:21), whilst the lower and presumably original foundations were said to have comprised angular rubble firmly set and packed with grey clay (D14:25). The south wall of the building, which was even less well preserved, probably experienced a similar history, though it is unclear whether it was retained in use during the chalet phase.

PARTITION WALLS

Six of the slots identified in 1978 (nos. 2, 4, 5, 7, 9 and 11) were distributed at sufficiently convincing intervals between the east wall of the officer’s quarters (E14:46) and the east wall of the building as a whole (H14:46, H15:21) for them to have represented partitions separating the various contubernia of the Phase 2 stone barrack block. Two missing partitions must be restored to complete the series, one c.0.40m west of soil change no. 6 to divide Contubernium 4 from 5, and a second c. 1.20m west of partition 11 to separate Contubernia 7 and 8.

The normal contubernium width was c. 3.20m, although there was considerable variation. In particular two or three contubernia at the east end of the building were significantly wider than the other six rooms (the width of Contubernium 9 varied between 4.20m and 4.40m, whilst 7 and 8 were perhaps around 3.90m wide internally, although 7 could have been closer to the normal range and 8 similar in width to 9 for instance). One possible explanation for the larger size of these contubernia could be that they included junior officers of the turma – the duplicarius and sesquiplicarius – amongst their complement.

Slot 2 (E14:51), which probably separated Contubernia 1 and 2, was deep and definite with differently-coloured clay and chippings right down through the fill. It possibly ran down the east side of flags E14:31. This would give Contubernium 1 an internal width of 3.60m. Slot 4 (E14:53), between Contubernia 2 and 3, was again deeper and was recognised in two separate sondages. The northern length was filled with chippings in a dark matrix. The surface to the east was light-coloured, whilst that on the west side had a lot of plaster in it as though the partition had been rendered. The more southerly had darker clay on each side and a lighter fill with chippings and upright stones for a socket or post-hole. With Slot 2 this was appropriately spaced (3.20m) to define another contubernium (2). Two separate lengths of Slot 5 were revealed some 3.30m further east. The northern section (F14:55) was very slight, with again decayed mortar to the west. More of this slot survived to the south (F15:25), containing a lot of chippings, but it was narrower than its northern counterpart. Two possible strips were also identified in the case of Slot 7, which must have separated Contubernia 5 and 6, the northern (F14:57) being 0.19m wide with dark coloured clay on either side and mixed clay, but not many chippings, along its line. This possibly lined up with F15:24 to the south (recorded in the Site Notebook, but not on the plan), which underlay the later clay floor F15:17. The ninth slot (G14:31) was also filled with gravel chippings and was 0.30m wide, but of some depth. It was appropriately situated to represent the partition between Contubernia 6 and 7 and would make 6 some 3.10m wide. Slot 11 (H14:42), which probably marked the west wall of Contubernium 9, was also relatively deep, and contained the usual gravel fill.

URINE SUMP

No definite examples of the kind of urine sumps recognised in Building 9 were identified in this block, either in association with this phase or with the preceding timber barrack. The only possible instance was to be found in the fourth contubernium from the west where an oval pit (F14:51, F15:07), faced by stone blocks along its east side (F14:52, F15:15), was revealed, the western side wall having presumably been robbed out. Flagstones associated the Phase 1 floor (F15:23) were exposed in the bottom of the feature. However the urine sumps identified in Buildings 9 and 12 were invariably positioned on or close to the medial line of their respective contubernia, whereas this drain was located very close to the estimated eastern edge of Contubernium 4. It is therefore more likely to have been associated with the subsequent chalet phase instead, since it did occupy the medial line of Chalet Z (see Fig. 16.14 below).

FLOOR LEVELS

The fullest sequence of floors was encountered in E14 and E15, where the lowest level comprised areas of flagging (E14:31, 38, E15:11) in the southern part of the barrack block (see Figs 15.09, 15.12), as noted above, and corresponding clay floors to the north (E14:48, 49, overlain by a layer of possible occupation material E14:47). Both the clay and flagstone layers were covered by another clay level which was subdivided into many separate contexts, but appeared to extend the full length of the block. In F14 and F15 areas of flagging were noted to the south, but the corresponding clay floor in the north was not identified. The same overlying clay level was present, however. No relationships were noted between either of these clay levels and the partition slots in E14 and F14/15, with the exception of slot F15:24 (no. 7) which was recorded as being underneath clay level F15:17.

In the eastern third of the building, probably corresponding to Contubernia 6–9, only a few fragments of flagged flooring survived (G15:19, H15:18). A single clay level was also recorded across this end of the barrack (G14:25–9, G15:20, 26–8, 30, H14:41, H15:25, 27), which apparently overlaid the flagging (G15:20 over G15:19). Conversely, however, some of the primary partitions (G14:30/G15:33 and G14:23/G15:29 – no record in the case of H15:29) were recorded as cutting this clay level, which should imply that the clay level belonged to Phase 1 as well. It is possible that two phases of clay floor surface have been conflated into a single recorded level or that some of material associated with Phase 2 was removed during cleaning (G14:19, 20, G15:11) of the clay.

Figure 15.12: Successive phases of flagging in the southern ends of contubernia 1, 2 and 3, overlain by chalet walling.

These contradictory records underline the problems faced in trying to analyse the earliest phases of Building 10. It is tempting to assign the upper clay levels to the stone barrack and the lower to the timber barrack phase, however, in Contubernium 3, two levels of flagging (E14:38/E15:11) were noted, the lower of which may be assigned to the primary timber barrack and the upper to its stone replacement, as described above, but both levels were overlain by the upper clay layer (E14:24/E15:09). The upper clay level might therefore represent either a replacement clay floor of Period 2/3, associated with the later stages of the conventional stone barrack block, or conceivably, makeup levels for the subsequent chalet range (TWM Period 4). The actual sequence was probably fairly straightforward and similar to that encountered in Building 9, but the excavation records do not enable specific contexts and the dateable material contained therein to be confidently ascribed to a particular phase.

The distribution of the flagging and clay associated with the lowest surfaces suggests that each contubernium was divided into two rooms, a clay-floored north room and flagged south room, like Building 9. It is noteworthy that the traces of flagged floors were again confined to the southern part of the contubernia, as in Building 9. However this poses a problem regarding the orientation of block. If the two barracks faced one another, as was commonly the case, the flagging, which presumably floored the front rooms, should have been restricted to the northern halves of the contubernia. Instead the location of the flagging suggests that 10 faced south towards the intervallum road and the rampart. This is not unparalleled; at Housesteads, Building XIII, in the north-east quarter of the fort, faces north onto the rampart and intervallum road rather than south towards the neighbouring barrack, XIV, though in this case the layout was probably influenced by topographic considerations. In this case, the face to back layout of Buildings 9 and 10 may reflect the difficulties that would have been experienced if two opposing turmae had both attempted to issue from their barrack with their horses and mount up at the same time in the relatively restricted space of the intervening street (Alley 5), which was no more than 4.00m wide. It was perhaps judged more efficient if each turma had its own space to assemble, with the turma from Building 9 drawing up on Alley 5 whilst that occupying Building 10 used the intervallum road. The fragmentary evidence from Building 11 suggests that it too followed the same pattern, the drains or urine sumps associated with the Period 2/3 stone barrack block being located in the southern half of the contubernia.

Much of the area of the officer’s quarters had been removed by the construction of a modern cellar (D14:09), leaving only the northern part of the house available for examination, whilst the north-east corner was concealed by later road surfaces and chalet period structures which were largely left in situ, though the sandstone and grey/pink clay exterior wall foundations (D14:42, 44) were traced. The wall dividing the officer’s quarters from the contubernia remained only as a very patchy foundation of pinkish and orange clay (E14:46) which had no clear line. No trace of an earlier timber partition was recognised in this area.

As a result of the limited extent of the area examined, no clear impression of the overall development of the house could be gained, though a number of features were identified. Within the officer’s quarters, a drain (D14:15/31) and parts of the flagged floor (D14:15, 28) were revealed and assigned to the stone barrack by the excavators (Figs 15.13, 15.14). All these features overlaid or cut into a layer of orange silty clay (D14:32, E14:37). The drain was 0.33–0.35m wide, with side walls constructed of neatly coursed stone blocks (Fig. 15.13), and was filled with a mid-grey silty soil with small stone and coal inclusions (D14:26). A 1.30m length of the drain survived, but could be seen, in the bottom of a modern drain cut (D14:03), to extend further northward and may have continued via an outlet through the north wall of the building, though this was not traced. The flagged floor was separated into two distinct areas by a 0.80m wide spread of small, close-set stones (D14:27), mostly consisting of rubble, but with a few small flags. The flagstones on either side formed a clear edge (Fig. 15.14). In plan, the feature is reminiscent of the urine sumps found in Building 9 and 12, but analysis of the site photographs demonstrates that no pitched stones defining such a pit were evident in section, and nor was any staining apparent in the bottom of the modern drain cut to the north. It seems likely that flagging was respecting the edges of an internal structure, perhaps of timber construction, which sat on the stone spread. Such a structure may have been associated with the stabling of the officer’s horses. To the east of the flagging an area of rounded cobbles stones (D14:29) was recorded, running north-south, though evidently partially removed by later activity so its full extent could not be determined. Some of the stones appeared to be worn so the feature was interpreted by the excavators as a possible surface. However the site photographs suggest the band of was of some depth and it might therefore represent the foundations for a north-south partition wall, perhaps defining a passageway at the eastern end of the house. At its south end some of the flagstones of D14:28 apparently extended across the wall’s line.

Figure 15.13: The stone-lined drain in the decurion’s quarters of Barrack 10 (Stone Phase 1), from the north.

A number of timber features, including an east-west partition slot (D14:33, E14:42) and three or possibly four post-holes (D14:34–36, E14:43), uncovered in the eastern part of the officer’s house, might relate to the earlier timber barrack (see above), but there was too little evidence to present a coherent sequence of developments in this part of the block. The external dimensions of the officer’s quarters in this period were 10.80m × 8.40m.

Three drains were noted in the road surfaces adjacent to the building. Immediately to the east of the building, lay a north-south drain (H15:16), which was characteristic of the primary drains noted at the ends of several barracks, e.g. Buildings 1, 3, 4, 5 and 11. Only the west side of this drain remained, with up to three courses surviving (Fig. 15.15). The east side had been removed by a modern drain trench. The gap between the north-south drain and the east wall of the building was packed with rubble including some facing stones (H15:15). This was thought to be secondary to the drain, but to pre-date Chalet X. It may therefore have been packed in when the barrack was rebuilt in stone. In a subsequent phase the drain was reconstructed using upright slabs to reline the sides (Fig.15.15). Elements of both of the slab sidewalls survived, though several stones were displaced by the modern drain. This method of construction is typical of some of the later drains in the fort, notably that running south eastward from the south end of the granary past the south-west corner of the principia (G11:04). It may even form another stretch of the latter drain, perhaps connecting up with the similarly constructed length observed in the east carriageway of the south gate (H16:06). This latter phase of the drain may be contemporary with the construction of the chalets.

Figure 15.14: Period 2 stone surfaces in the decurion’s quarters of Barrack 10 partially reused in the chalet barrack.

Figure 15.15 View of Building 10 from the east showing the east wall. The drain side-wall and the flagstones of the secondary drain lining can just be seen alongside.

A second stone-walled drain (E15:05, F15:03, G15:17) was noted set into the intervallum road surface south of the barrack. The drain’s slightly sinuous course ran parallel to the building, its distance varying between 1.40m and 2.20m from the south wall of the block. It was filled with a mixture of dark grey clayey silt and brown sandy silt and stone (E15:06, F15:04, G15:18). This drain was tentatively attributed to the chalet phase (i.e. Period 4) by the excavators, although the stratigraphic evidence is inconclusive.

The road surface into which the drain was set was composed of orange gravel and small cobbles (E15:04, F15:05, G15:07) which covered the area between Building 10 and the drain (the area south of the drain was not cleared of overburden). This was the only extensive level of the via sagularis recognised south of Building 10 in 1978 and was thought to represent the primary road metalling. However the full sequence of levels in the south intervallum road was not investigated so the attribution of this surface to Period 1 cannot be confirmed, although the orange gravel composition and small size of the metalling is consistent with the earlier road surfaces recognised elsewhere in the fort (cf. the west via quintana for example).

The drain running along the intervallum road to the west of the barrack block was also exposed for a length of 8.00m (D13:26, D14:11). This formed a continuation of the drain traced alongside the west wall of the hospital in 1977 and 1983.

FINDS

Mortarium stamp: 125–45 (no.15, E14:28)

Coin: Trajan, 103–17 (no. 57, E14:24)

Bone: die (no. 36, E14:24)

Mortarium stamp: second century, before 180 (no. 38, F14:44)

Copper alloy: brooch (no.30, F14:44)

Pottery: lamp (no. 8, F15:20)

Stone: throwing stone (no. 66, G14:31)

The east wall foundation contained two sherds of mid to late Antonine samian (H15:21). The foundation for the north-south internal wall contained a number of sherds from a single locally produced grey ware cooking pot and a sherd from a flat-rimmed BB1 bowl/dish, both second-century in date (E14:46).

Most of the contubernia produced only one or two sherds of pottery, second-century in date, from the clay floors. The exception was Contubernium 2, where much of the pottery came from the lower part of a single BB2 cooking pot (F14:41). There were also sherds of BB1 and locally produced wares, a sherd of mid to late Antonine samian, and a single sherd of third-century Nene Valley ware (E14:24).