Pabo Post Prydain, “The Pillar of Britain,” was a king of the northern Pennines and brother of Eliffer of York. His territory was south of the Tyne, with borders on the Vale of York and the Pennine frontier of Rheged. His son Dunawt was chief of the Northern Alliance that eventually destroyed Urien.

St. Patrick, patron saint of Ireland, was probably born in South Wales. His father was a Romano-British deacon named Calpurnius, and his own Celtic name was Succat.

According to legend, Patrick was abducted as a 16-year-old boy by Irish slave traders in about 405 or 410 and carried off to Ireland. He was sold in County Antrim to a chief called Milchu. He managed to escape after six years of captivity and made his way 200 miles overland to board ship. He was at sea for three days, then made his way home to his parents. They urged him never to leave again, but a deep restlessness inspired dreams that made him travel to Rome. He became a monk in Gaul, first at Tours, then at Lerins, before returning to convert his captors. According to Patrick himself, he had decided a long time before that he would have to return to Ireland.

Patrick was consecrated a bishop at the age of 45. In 432 he is believed to have been sent by Pope Celestine I to Ireland as a missionary. He landed at Wicklow and from there sailed north to convert his former master Milchu. In Down he was able to convert another chief, Dichu, to Christianity, and at Tara he preached to Loegaire, King of Tara. He also converted the tyrannous Mac Cuil, who became bishop of the Isle of Man.

After 20 years of missionary work, Patrick fixed his see at the royal center of Armagh, close to the ancient capital of Emain Macha, in 454. He died at Saul in 459 and was probably buried at Armagh.

As a slave himself, Patrick had the strongest personal motive for preaching against slavery. He preached from experience. In an open letter probably written in 445, he censured King Coroticus (Ceretic) of Clyde for stealing Irishwomen and selling them to the Picts as slaves. King Coroticus was not only a pagan, he was a committed anti-Christian. According to Patrick’s hagiographer, Patrick turned him into a fox.

In the 450s, Patrick came into conflict with the wizards of King Loegaire, son of Niall, at Tara (See Magicians). Murchu describes the trial of strength:

The fierce heathen emperor of the barbarians reigned in Tara, the Irish capital. His name was Loegaire, son of Niall. He had wise men, wizards, soothsayers, enchanters and inventors of every black art who were also in their heathen, idolatrous way to know and foresee everything that happened. Two of them were above the rest, their names being Lothroch and Lucetmael.

They predicted that a strange new and troublesome faith would come and overthrow kingdoms.

A pagan festival, Beltane, coincided with Patrick’s celebration of Easter. On the eve of Beltane when a great sacred bonfire was lit, a fire was seen to be burning in the direction of Tara: the religious focus of Ireland. This was surprising, as only the magi were authorized to kindle such a fire. They anxiously approached the blaze and found Patrick and his followers chanting psalms round their campfire.

Patrick was summoned to the Assembly at Tara, where he eloquently defended his mission. The magi challenged him to perform a miracle to prove divine support, but he refused. The magi then cast a spell and blanketed the landscape in heavy snow. Patrick made the sign of the cross and the illusion evaporated.

All kinds of magic feats were performed during this contest between Patrick’s white magic and Lothroch’s black arts. At one point Patrick caused one of the magicians to rise up into the air, fall headlong, and brain himself on a rock.

A great deal has been written about Patrick but his only certain literary remains are his spiritual autobiography, called Confession, and the letter he wrote to Coroticus. The point of his Confession was to explain why he would not return to Britain. The implication is that a British synod claimed authority over him and summoned him in order to exert that authority. Patrick implies that he could override the wishes of the British synod, and he evidently had Pope Leo’s (440–61) approval to support him.

In spite of his high profile, Patrick did not have any obvious successor and in the years following his death he was seen in Ireland as just one saint among many.

A sixth-century Celtic saint, the son of a nobleman, Perphirius of Penychen. He had two brothers, Notolius and Potolius, and a sister, Sativola. He was educated at Illtud’s school at Llantwit (some say he was at Caldey Island, which was an offshoot of Illtud’s foundation) and wanted to live the life of a hermit. Illtud tried to dissuade him, but let him go when he insisted.

After spending time in a hermitage on his ancestral estates, Paul was summoned to the court of King Mark Conomorus at Villa Banhedos (later Caer Banhed, and now Castle Dore in Cornwall), where he was engaged in two sea defense projects involving building stone embankments to keep the sea back.

He later emigrated to Brittany, landing at Ushant with 12 disciples and 12 relatives. He won the respect of the local chief, Withur (Victor), whose “city” was at Roscoff. Paul then crossed to the island of Batz, where he got rid of a dragon. Withur and his people begged him to become their bishop. In about 550 he went to Paris with Samson. After foretelling the destruction of Batz by the Normans and directing that his body should be buried on the nearby mainland for the convenience of future pilgrims, he died on Batz.

In the 1950s it was estimated that there were about 250,000 people in Britain in 100 BC, increasing to 400,000 by the time of the Roman invasion. More recent estimates have been more cautious, and few prehistorians now will attempt even to guess a population figure, but the numbers do seem to have increased in the late Iron Age. This population growth may have been associated with improvements in food production. Julius Caesar’s description leaves out numbers:

The population [of Britain] is exceedingly large, and the ground thickly studded with homesteads, closely resembling those of the Gauls, and the cattle very numerous… There is timber of every kind, as in Gaul, except beech and fir. Hares, fowl and geese they think it unlawful to eat, but rear them for pleasure and amusement. The climate is more temperate than in Gaul, the cold being less severe… Most of the tribes of the interior do not grow corn, but live on milk and meat and wear skins.

It was Julius Caesar who also created for posterity the enduring image of blue-painted savages: “All the Britons, indeed, dye themselves with woad, which occasion a bluish colour and thereby have a more terrible appearance.” It is still not clear whether this meant that the Britons painted their bodies with woad or tattooed themselves.

Diodorus Siculus gave a description of what the Gauls did to their hair. Men and women wore it long, sometimes plaited: “They continually wash their hair with limewash and draw it back from the forehead to the crown and to the nape of the neck, with the result that their appearance resembles that of Satyrs or of Pans, for the hair is so thickened by this treatment that it differs in no way from a horse’s mane.” This description is supported by the statue of the Dying Gaul (see Symbols: Nudity) and the coin portrait of Vercingetorix.

Normally, the Celts were warmly clad. They wore close-fitting trousers that the Romans referred to as bracae, “breeches.” Over these they wore a long tunic made either of wool or of linen, which was held at the waist by a belt. Over this, they wore a cloak that was fastened at the shoulder with a brooch. The textiles were dyed bright colors and threads of different colors were woven so as to produce striking striped or checked patterns (See Tartan). The Roman observers were startled by the colors and patterns, which they were not used to seeing.

Nor were they used to seeing beards and moustaches. The Celts grew both and grew them long. Diodorus commented fastidiously, “When they are eating, the moustache becomes entangled in the food, and when they are drinking the drink passes, as it were, through a sort of strainer” (See Dress).

Peredur and his brother Gwrgi were co-rulers of the kingdom of York (north-east England) in the late sixth century. They were the sons of King Eliffer of the Great Army. Peredur Steel-Arm was King of York from about 560 until 580, when he was killed in the Battle of Caer Greu.

A prince called Arthur was associated with Peredur, doubtless named after the great overking of southern Britain who had died not long before (See Arthur).

A Dark Age Celtic saint, the son of Clemens, a Cornish chief. He studied in Ireland for many years, returning to Cornwall with disciples Dagan, Credanus, and Medanus. They landed near Padstow (Petroc’s Stowe). Both Samson and Wethenoc had set themselves up in oratories in the area, and they were expected to move out to make way for Petroc, which they did with reluctance.

After a seven-year pilgrimage to Rome and Jerusalem, Petroc returned to Cornwall following the death of King Theodoric. Then Wethenoc returned and, to avoid a quarrel, Petroc withdrew to Little Petherick. He baptized the Cornish King Constantine. A powerful local magnate, Kynan, built an oratory in his honor near Bodmin.

After many years at Padstow and Petherick, Petroc moved to Bodmin, where he displaced the hermit Guron. He was visiting the monks at Padstow and Petherick when he was taken ill; he died at a farmhouse at Treravel.

St. Petroc spent much of his time teaching and despatching missionary monks from Padstow, which was then the main port for southern Ireland, south Wales, southern Dumnonia, and Brittany.

A Celtic tribe in Gaul, with its main center at Lemonum (Poitiers). Julius Caesar depended on the Pictones to build ships for him on the Loire. At the time of the Roman conquest, Duratios was King of the Pictones and frequently aided Caesar in naval battles. The Pictones supported the Romans because they were afraid of the expansionist strategies of other Gaulish tribes. Even so, they did send 8,000 men to support Vercingetorix during the Gaulish rebellion of 52 BC.

A general Latin name given to the people who lived in the northern half of Scotland, “Pictland,” in the third century AD. “The Painted People” was a nickname given by the Romans to northern Brits who wore woad or sported tattoos. “Pict” does not therefore really define a tribal or ethnic group in the Roman period, and Pictland, Alba, and Caledonia seem to have been thought of as being much the same area—Scotland.

In the past it has been suggested that the Picts were in some way the pre-Celtic inhabitants of Scotland, but that presupposes a belief that the Celts arrived in these islands during the Iron Age. Now that we see that they were well-established there by that stage, in fact they had been settled in Britain for thousands of years, the concept of “pre-Celts” has no meaning.

One theory holds that the Picts came originally, in the first millennium BC, from Ireland, having been displaced by incoming Celts—but there seems to be no particular reason for believing this. Any cultural or “ethnic” differences between the Picts and the people living to the south could be explained by their geographical isolation. They did evolve some extraordinary pictorial symbols, which appear to relate to their language. In other words the Picts’ carved memorial stones carry pictograms (no pun intended).

The Irish called the Picts Cruithin, which is an early Irish transliteration of Britanni, so the Irish were not really identifying them as a distinct people either.

A plaid is a tartan blanket thrown over one shoulder to make a kind of cloak. Plaid is the Gaelic word for “blanket.”

A Greek philosopher and polymath (135–51 BC) who studied at Athens. In 86 BC he settled in Rome, where he became a friend of Cicero and other leading figures. He wrote about history and geography and is a source of information about the Celts in the late Iron Age.

King of the Iceni tribe in the first century AD. He was Boudicca’s husband. On his death he left half of his kingdom to Rome and assumed Rome would allow his family to inherit the other half. He underestimated the greed of the Roman administrator, who took everything; this led his successor and widow to lead a revolt against Roman rule in AD 60–61.

Prasutagus was the Latinized form of his Celtic name, Prastotagus. One of his coins was inscribed in a mixture of British and Latin, SVB ESV PRASTO ESICO FECIT, which means “Esico made [this] under Lord Prasto[tagus].” The coin bears Prastotagus’s portrait.

Vix is a village in Burgundy at the site of an important ancient fortified settlement with several burial mounds.

One of the mounds contained the body of a 30-year-old aristocratic woman who died in about 550 BC. Her body was buried with great ceremony on a bier that was made out of the body of a wagon. The wheels were taken off and laid against the wall of her burial chamber. Her grave goods included a range of treasures, including Greek cups and other drinking vessels, but most remarkable was the huge bronze vessel, a krater for mixing wine. This stands as tall as the princess herself and is one of the most beautiful treasures of archaic Greek art that have survived to the present day. It is in the museum at Châtillon-sur-Seine in Burgundy.

The krater was made in Greece or a Greek colony in about 500 BC, and transported in kit form, in labeled pieces, across the Mediterranean and up the Rhône River into central France. The pieces were assembled for the royal client at Vix. This astonishingly exotic and expensive vase was decorated around its neck with a frieze of Greek warriors in full armor with chariots. The Greek krater does not tell us that the Greeks colonized central France, but that the Iron Age kings of Gaul were rich and powerful enough to purchase luxury goods from far afield.

It was importing artwork of this distinction that inspired the Celtic craftsmen to aspire to ever-higher artistic standards. It fueled cultural growth. The burial of the Greek krater also ensured that at least one example of this type of object survived for people of later centuries to enjoy; nothing quite like it has survived in Greece itself. By burying grave goods, the Celts became, unconsciously perhaps, custodians and curators of a European heritage.

An Iron Age Celtic tribe in eastern Brittany, with its main center at Rennes. The Redones sent a contingent to fight against Julius Caesar during the siege of Alesia.

The Roman conquest of Gaul was a bloodbath. A million Gauls, 20 percent of the population, were killed; another million were enslaved. Three hundred tribes were subjugated and 800 towns were destroyed. All the native Gauls living in Avaricum (modern Bourges) were slaughtered by the Romans—40,000 people.

The son of Maelgwn and his successor as King of Gwynedd.

Maelgwn’s son-in-law Elidyr tried to take Gwynedd from Rhun, but was killed on the beach at Caernarvon. Rhydderch Hael sailed south to avenge the killing of Elidyr, but his raid on Gwynedd was unsuccessful and he had to withdraw. Rhun responded by gathering an army and marching it north, through South Rheged, probably by way of York. It was a march of legendary distance and duration. Rhun’s army was away from home for a very long time and is said to have met no resistance. Elidyr’s son and successor, the boy king Llywarch Hen, was in no position to resist and had not the temperament either; it was probably wiser anyway to allow Rhun’s great army pass through unopposed. Llywarch Hen was left alone, and eventually died, an elderly Celtic exile writing poetry in Powys, long after the English had overrun his kingdom.

Rhun marched on, deep into the Gododdin (south-east Scotland), all the way to the Forth, still unopposed. After this impressive parade of military strength, he marched his great army home to Gwynedd. It was a triumph. Yet it also illustrated, just as Arthur’s career had 30 years earlier, how the British could organize brilliant and spectacular military coups de théâtre and yet fail to hold together the polity of a large kingdom. To judge from Gildas, the British disliked kings. They felt no overriding need to unite behind a powerful monarch or submit to central control. They simply did not see, even as late as 560, how dangerous the growing Anglo-Saxon colonies in the east and south-east were. The soldier’s loyalty was always to his lord, but this was a local war-band loyalty. Petty rivalries among the war-band leaders, the kings, and sub-kings, would be likely to erupt quickly, easily, and repeatedly into civil war.

The northern British poems express the spirit of the times well. The highest ethic involved the devoted loyalty of faithful warriors to their lord and his personal destiny. The idea of sacrificing or compromising that loyalty by serving an overlord ran against this sentiment. Long-term loyalty to an overking or commander-in-chief would have been alien to the rank-and-file warrior. The effect was that although British resistance to the advance of the Saxons in the sixth and seventh centuries may have been intermittently highly successful, in the end it was doomed, in the same way that resistance to the Roman invasion had been in the first century, as contemporary Roman commentators had recognized (see Myths: The History of Taliesin).

Rhun, son of Urien, became a cleric, settling in Gwynedd. He may have been the author of The Life of Germanus in about 630. Varying accounts of the baptism of King Edwin of Northumbria exist. One is that Rhun baptized Edwin while the latter was in exile, a boy-refugee in Gwynedd, some 15 years before Paulinus baptized the people of Northumbria. Another account (recorded by Nennius) is that Rhun baptized Edwin in 626, in Northumbria, when he was king. Both may be true, as it may have been deemed necessary to stage a repeat baptism ceremony for the king, in public, for the benefit of his subjects.

Bede’s account is different again, giving Paulinus the credit, but Bede had a political motive. Writing when he did, he may have wanted to show the first Christian Anglian king as sponsored by the Roman Church, not by the Celtic Church. A power struggle between the two had been going on since Augustine’s arrival at the end of the sixth century, and Bede would have had a strong motive for reducing the role of the British priesthood and exaggerating that of the Roman. It seems likely, then, that it was Rhun who actually wrote the account of the baptism ceremony, first hand, in 627.

See Elidyr, Urien.

See Dyfnwal, Kentigern.

One of the things the Romans did for us was to build roads. That at least is what we have been led to believe. But what was there in the way of a road system before the Romans arrived in the Celtic west—in Gaul, in Hispania, in Britain?

Ancient trackways followed the crests of prominent hill ridges, especially where these persisted for long distances. The chalk and limestone escarpments of lowland England and northern France lent themselves to this form of communication. One advantage was that they were raised and on permeable rock, so they were drier and firmer than tracks on lower ground. Another advantage was that navigation was easier; all you had to do was to follow the crest of the ridge. Being raised up also gave better views across the landscape, so you had better opportunities to identify where you were.

There were the South Downs Way and the Pilgrims Way in Sussex and Kent, the Ridgeway in Wiltshire, the Jurassic Way in Northamptonshire and the Icknield Way in Buckinghamshire, Hertfordshire, Suffolk, and Norfolk.

In wetlands, wooden walkways were constructed. In the Somerset Levels, around 40 wooden tracks dating from 3000 BC onward were built so that people and livestock could cross from Wedmore to the islands of Byrtle, Westhay, and Meare, and from there to the Polden Hills. These tracks were up to 2 miles (3km) long.

Some roads that we think of as Roman roads were in fact Roman surfaces added on top of pre-existing Iron Age roads. These were roads that had been built by the indigenous people. A rescue dig next to a quarry 2 miles (3km) south of Shrewsbury gave an opportunity to test a long stretch of known Roman road. The road surface was first built in 200 BC after the land was cleared by burning. The route was used for driving cattle, and their hooves churned it into mud (the Irish Gaelic word for road is bothar, which means “cow-path.”)

To improve the road, a layer of elder brushwood 15 feet (4.5m) wide was laid down, with earth on top, followed by a layer of gravel and sand, then river cobbles, which were compacted into this foundation. The result made an all-weather roadway about 16.5 feet (5m) wide. It was subsequently remade a little wider, and then remade again. The road’s surface was grooved by parallel ruts, showing that carts with a 6.5-foot (2m) wide wheelbase were being used. And all this happened before the Roman occupation, when a Roman road surface was added on top of the Iron Age road layers.

So, there were decent, dry, all-weather engineered roads in Britain—and Gaul—before the Romans arrived. Julius Caesar does not describe these roads, but he does say that the Gallic charioteers preferred to fight off-road, which means that there must have been roads.

Even in Italy, there were roads before the Romans. The Via Gabina was mentioned as early as 500 BC and the Via Latina in 490 BC, when the Etruscan king had only just been overthrown and the Roman republic was scarcely underway, yet it seems the “Roman” road system already existed.

The son of Birra of the Eoganachta (in Munster, Ireland). Ruadan was a huge man, said to be 12 feet (3.6m) tall. He revived the son of a British king who was drowned when one of Brendan’s ships sank in the Shannon estuary.

His monks lived an easy life, thanks to the manufacture of a “lime juice” that was evidently a distilled liqor. The easy living and the lime juice attracted many monks from other houses. Under pressure from indignant abbots, Finnian told Ruadan to stop production and practice conventional subsistence farming.

Ruadan is said to have written several books, including Against King Diarmait, The Miraculous Tree, and The Wonderful Springs of Ireland. He died at Lothra; his head was preserved in a silver reliquary until the sixteenth century. A bell that was found in a well at Lorrha was venerated as the bell he rang at Tara against King Diarmait.

Unfortunately the recipe for lime juice has not survived.

St. Samson was a sixth-century contemporary of Arthur. His father was a Demetian landowner and also an altrix, a companion of the king, who was at that time probably Agricola (See Aircol).

The idea that Samson should attend Illtud’s monastic school at Llantwit Major in Glamorgan, next to a ruined Roman villa, came from “a learned master in the far north,” probably Maucennus, Abbot of Whithorn, who is known to have visited Demetia at the right time. Samson was duly sent to St. Illtud’s. Illtud was responsible for educating many boys from aristocratic families, from the age of five until they were 16 or 17. He had great influence, in that he turned out men of the caliber and importance of St. Samson, Paul Aurelian, Gildas, Leonorus, St. David, and Maelgwn, King of Gwynedd.

By the age of 15 Samson was already very learned and at an unusually young age was ordained priest and deacon by Bishop Dubricius. This aroused the jealousy of Illtud’s nephews, who feared that he might succeed as the school’s head when Illtud retired and so deprive them of their inheritance. Perhaps because of this ill-feeling, Samson gained a transfer to another of Illtud’s monasteries, newly set up by Piro on Caldey Island, where his great scholarship and austerity astonished the Caldey monks.

He did not stay long at Caldey. He “longed for the desert,” and was really more suited to the life of a hermit than the monastic life. He lived for a time in an abandoned fort on the Severn River, and then in a cave at Stackpole. He was guided by visions and his inner voices directed him to cross to the monastery of Landocco, founded by Docco at St. Kew in Trigg in Cornwall. This was the earliest monastery we know of in Cornwall; it was already old when Samson arrived there. Docco, a nickname of Kyngar, had been born in about 410, when the Romans were still in Britain. But the abbot at Landocco, Iuniavus, did not want Samson there. He told him plainly, “Your request to stay with us is not convenient, for you are better than us; you might condemn us, and we might properly feel condemned by your superior merit. You had better go to Europe.”

When St. Petroc landed in Trigg, he found Samson living, not surprisingly, in a cell beside the Camel estuary. After some dispute, Petroc forced him to leave. Samson was stupefied by his rejection in Cornwall.

Before he left St. Kew he had a revealing encounter with a crowd of non-Christians at Trigg. He came upon the crowd, subjects of a Count Gwedian celebrating pagan rites at a standing stone. Samson dispersed the crowd and carved a cross on the stone with his pocket knife, an ad hoc example of the Christianization of pagan monoliths that was very common in Brittany.

He made his way across Cornwall to “the Southern Sea,” visiting Castle Dore, the power base of one of the Cornish sub-kings, Mark Conomorus. In 547, he sailed to Brittany, where he became bishop of the kingdom of Jonas of Dumnonie, based at Dol. Samson’s journey southward was repeated by a steady flow of Irish-inspired missionaries.

In 557, he is recorded as attending a church council in Paris. He seems to have died of old age in 563.

The oldest surviving Life of Samson dates from about 600, but it is based on a contemporary original written by Samson’s cousin Enoch, who is known to have gone to the trouble of interviewing Samson’s mother for details about his childhood. So, what is written about St. Samson is rather more reliable than the stories we have about some other saints.

A Roman commentator, Lactantius Placidus, described how the Gauls singled someone out as an emissary victim or scapegoat:

The Gauls had a custom of sacrificing a human being to purify their city. They selected one of the poorest citizens, loaded him with privileges and thereby persuaded him to sell himself as victim. During the whole year he was fed with choice food at the town’s expense, then, when the accustomed day arrived, he was made to wander through the entire city. Finally, he was stoned to death by the people outside the walls.

(See also Religion: Human Sacrifice.)

See Brennus.

In remote antiquity the logboat was the commonest vessel in use on rivers and in estuaries. Possibly composite boats were made for use on unsheltered open water by lashing two or three logboats together for stability. These trimarans might well have been fitted with decks for transporting goods.

A simple, small, bowl-shaped, one-person boat was made of wicker and covered in hide to make a coracle. Coracles are still made in Wales today, but instead of hide canvas is used, daubed with pitch. These small boats are really designed for paddling across lakes, or fishing in rivers, but in 1974 a Welshman called Bernard Thomas crossed the English Channel in one. In antiquity, it was usual to use larger vessels on the open sea, but constructed in exactly the same way; they were called curraghs.

There are several documentary references to curraghs, which are still built in Ireland. Festus Rufius Avienus wrote a poem, Ora Maritima, based on a sixth-century BC source, in which he refers to the Oestrymnides (who perhaps lived in Brittany) plying “the widely troubled sea and swell of monster-filled ocean with skiffs of skin… [They] fit out boats marvellously with joined skins and often run through the vast salt water on leather.” Pliny quotes a third-century BC source about Britons traveling to an island “to which the Britons cross in boats of osier covered with stitched skins.” Strabo mentions “boats of tanned leather.” Julius Caesar gives a little more detail: “The keels and ribs were made of light wood, the rest of the hull was made of woven withies covered with hides.”

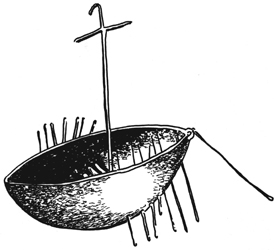

We even know what these boats looked like, thanks to a gold boat found on a former shoreline of Lough Foyle in County Derry in 1896. It was discovered along with a hoard of other gold objects, including a large torc, two necklaces, and a bowl. It is the gold ship, however, that particularly captures our imagination, not just because it tells us in detail what an Iron Age curragh looked like, but because of its beauty:

The ship is broad in the beam, slightly pot-bellied, with a mast and a yard-arm to carry the sail, seven pairs of oars, originally nine benches for rowers, and a steering-oar at the stern.

Such ships carried iron anchors, of a design that continued in use for many hundreds of years, slung on iron chains (see Symbols: Boat).

See Caratacus.

The first High King of Ireland (See Genealogy).

By the first century BC, there is clear evidence of the nature of Celtic societies. They are heroic, on the Mycenaean model. They are hierarchical, with kings and queens at the top, heading an aristocracy of warriors. Some of the earliest Irish literature shows swaggering, boastful, aggressive heroes who are constantly quarreling and fighting in order to prove their worth to their peers. The quarrels are often over small matters, but even a small snub cannot be overlooked. It is very reminiscent of the sort of society described in Homer’s Iliad, which was not written down until about 700 BC, but contains material from 500 years earlier.

Priority at the feast was important to these heroes (See Food and Feasting). Feasting can be detected in the archeology of places such as Danebury hillfort in Hampshire, England, where there were hooks to carry cauldrons, spits, and middens containing the remains of joints of meat.

In Ireland cattle-raiding was another way in which warriors showed their prowess. Wealth was measured in cattle—the cow was the unit of currency.

Julius Caesar set out the structure of Celtic society clearly. It was organized into Druids (learned men), warrior-nobles, and ordinary people. He mentioned at least one king, Divitiacus, who in the early first century BC held lands on both sides of the English Channel. At the lowest level there were slaves, so the plebes (ordinary people) must have comprised at least two categories: slaves and freemen. Slaves certainly existed in Britain; the slave-gang chain complete with neck-shackles found at Llyn Cerrig Bach in 1943 proves this. Diodorus Siculus says that in Gaul a slave could be bought for an amphora of wine.

Irish sources show that Celtic society was rather more complex than Caesar noticed, which is what we might expect. The Irish texts mention kings, sub-kings, warrior nobles (flatha), lesser nobles, freemen (bo-airigh), and serfs. Freemen consisted mainly of farmers who paid food-rent to the king, though the class included priests, artists, and craftsmen as well as landholders. The main social unit was the extended family or derbfine, which included the four generations of descendants from a common great-grandfather, and groups of these made up the tuath, or tribe. The derbfine owned land collectively, in common; there was no individual ownership.

Looked at in terms of straightforward hierarchy, Irish society was feudal, with the High King of All Ireland at its head; below him the five kings of the provinces, Ulster, Munster, Connaught, Leinster, and Meath; below them the kings of the counties, and below them again the kings of the hills and the peaks. Then came the four classes of nobles, then the cattle-chiefs, then freemen and craftsmen, and then last of all the bondsmen. All of these except the last held land.

Kings were more than political and judicial leaders: they were battle leaders too, and they had priestly functions to perform when making sacrifices and when undertaking divination. In some Gaulish tribes, such as the Santones, the Remi, and the Treveri, the nobility abolished kingship, devolving the kingly powers upon a magistrate called a vergobret after an election. He served for a year only, and to prevent a return to kingship a second magistrate was appointed to take military power. The nobles devised every means possible to avert a return to kingship.

The king (Latin rex, Gallic rix) and his sub-kings bound themselves to one another by personal oaths of allegiance; similar bonds held lower social classes to higher social classes.

By 100 BC Celtic society had taken on a strongly stratified structure. The emergence of craftsmen and artists into the status of freemen was an interesting development. This may reflect the development of long-distance trade and the consequent availability of exotic raw materials for craftwork. The same long-distance contacts would have exposed kings and nobles on the Atlantic fringe to the refined art and craftwork produced in the Mediterranean region. The western kings wanted their own craftsmen to produce similarly refined pieces and so the craftsmen and artists achieved enhanced status.

Relationships between people were more ordered than might be expected. Classical writers normally intent on portraying the Celts as savages occasionally found themselves praising them for the structure and restraint of their society. Tacitus wrote a book called Germania about the northern tribes. One of his motives seems to have been to warn the emperor about the danger from the north, from these particular barbarians, but Tacitus found some things about them wholly admirable. Monogamy was strongly upheld, he said. Unmarried women guarded their virginity and valued it as something precious; they lived in a state of impregnable chastity. When an act of adultery came to light, which happened only occasionally, the offenders were punished severely, with flogging and public humiliation. All of this was in stark contrast to the scandalous goings-on in contemporary Rome. In certain ways, Tacitus said, the barbarians were more civilized than the Romans.

Inter-tribal politics were complicated. Quarrels and skirmishing were common. But the placing of major religious sanctuaries on tribal frontiers, and sometimes at the point where the frontiers of three tribes ran together, suggests occasional peaceful meetings. In northern France, for instance, the sanctuary of Morvillers was at the place where the lands of the Ambiani, Caleti, and Bellovaci met; Gournay was where the lands of the Ambiani, Bellovaci, and Viromandui met.

No doubt the sanctuaries were, like Christian churches, regarded as places of protection: places where “sanctuary” in the more general sense might be claimed. There may have been annual festivals at which representatives of neighboring tribes would gather to worship together, settle disputes, and negotiate political problems of common interest. In Caesar’s time several Gaulish tribes, such as the Bellovaci, had a council, described by a Roman general as a senate, and it allowed the nobles of the tribe to debate issues. But the tribal senate could be a very large body, of 600 members. It met when there was a crisis that affected the fate of the entire civitas.

But the tribes were not bound together with one another and did not easily agree. There was no real mechanism to bring them to agreement. This is clear from the response of the British tribes to the two Roman invasions. Some of the tribes were favorable toward Rome, seeing the advantage of greater access to luxury goods. By the time of the Claudian invasion, several of the tribal territories had become client kingdoms, and therefore in effect Roman allies. The British tribes were divided and this made conquest by Rome easy.

But in Caesar’s time, the tribes of one region in south-eastern England did come together to resist Caesar: the Trinovantes with their capital at Colchester, the Catuvellauni with their capital at St. Albans, and to some extent the Cantii across the Thames estuary in Kent. The confederation was fragile, however, and perhaps too much depended on the charisma of individual tribal chiefs.

In Britain, in the post-Roman sixth century, the social hierarchy had at its top the king (tighern or gwledig), though certainly in time of war there was an overking, commander-in-chief, or leader of battles above him (amerawder or pendragon). Under the king came the nobles (uchelwr) and the king’s hearth companions (teulu or altrix). Then came the ordinary people: the free-born citizens (boneddig), bondmen (taeog), and slaves (caeth).

Although the Celtic lands were divided up into countless kingdoms—some large, some small—there was a recognition that there was a need for a joint effort when a common threat appeared. Confederations of kings were formed, appointing one of their number overking to act as military commander-in-chief. He was known by different titles: sometimes by the Latin title dux bellorum (leader of battles), or sometimes by a Celtic title, amerawder (emperor) or gwledig (overking). Geoffrey of Monmouth has often been criticized for imposing a mindset from his own times on the Dark Ages, but his list of the “Kings of Britain” may actually tell us the succession of overkings. Geoffrey was using an early medieval list:

GORTHEYRN. GWETHUYR

VENDIGEIT. EMRYS

WLEDIC.

UTHERPENDRIC. ARTHUR.

CONSTANTIUS. AURELIUS. IUOR.

MAELGON GOYNED.

Translated and expanded, this becomes:

Vortigern the Elder (of Powys);

Vortigern the Younger (of Powys);

Ambrosius the Overking (of

Dumnonia); Uther Pendragon (of

Dumnonia); Arthur (of Dumnonia);

Constantine (of Dumnonia); Aurelius

(the Aurelius Caninus mentioned by

Gildas = Cynan of Calchvynnydd);

Ivor(?); Maelgwn of Gwynedd.

This is interesting in that it is consistent with what can be pieced together from other sources. It also shows the high kingship passing from one kingdom to another, but always within the province of Britannia Prima (Wales and the English West Country).

An underground chamber associated with Iron Age settlements in Brittany. The souterrain is tunneled out of the natural coarse granitic sand and then enlarged by making side chambers. It is still uncertain what these chambers were for, but the likeliest function is for storing seed-grain. Some archeologists believe they were built as refuges or for ritual (see Fogou).

See Patrick.

The Roman general who in AD 60 crossed the Menai Strait and attacked the Druids’ headquarters on the island of Anglesey. When he heard of the Boudicca rising, he marched his troops across to meet her and her army on Watling Street, where he defeated her.

Posidonius said that Gauls might commit suicide in certain circumstances, for instance in exchange for gifts that were distributed to their entourage. The Gauls were also ready to kill themselves after defeat in battle rather than surrender to an enemy.

Swords had bronze or iron hilts that were well made for gripping, but they were also highly decorative. One fine hilt made in about 100 BC is in the shape of a stylized human being, with the arms and legs acting as functional guards.

Swords were worn in scabbards, and the scabbards themselves had decorated mounts made of sheet metal. Scabbard mounts have been found in England, dating from around 100 BC.

Swords were believed to have magical properties and they were given pet names, usually known only to their owner (see Symbols: Magic). Arthur famously had his sword named Excalibur.

A bard, probably attached to the court of King Urien of Rheged (Cumbria). His name means “Radiant Brow.” Little is known about him beyond what is in his poems, but these are considered to be genuine and historically based; the historical references show that he was active around 550–60. The legendary account of Taliesin’s life written in the sixteenth century is probably not based on fact.

Twelve poems by Taliesin are now reckoned to be authentic productions. Eight are conventional praise poems for Urien as a “successful battle prince,” “generous patron of bards,” “protector of Rheged,” and “ruler of Catraeth.” Seven end with Taliesin’s signature tune—an identical formula expressing the wish to praise Urien until death:

And until I perish in old age

in my death’s sore need

I shall not be happy

if I praise not Urien.

In one poem, Urien has “overcome the land of Brynaich, but after having been a hero lies on a hearse.” This is interesting in showing that the allegedly conquered land was in the last quarter of the sixth century still being called by its British name, Brynaich, rather than by its Anglian name, Bernicia—at least by the Britons.

Taliesin wrote at least two battle-listing poems. In Rheged arise, he lists six of King Urien’s battles:

There was a battle at the ford of

Alclud,

a battle for supremacy,

the battle of Cellawr Brewyn,

long celebrated,

battle in Prysg Cadleu, battle in

Aber,

fighting with harsh war-cry,

the great battle of Cludwein,

the one at Pencoed.

The Battles of Gwallawg lists ten battles: one in the land of Troon, one near Gwydauk and Mabon, and the battles of Cymrwy Canon, Arddunion, Aeron Eiddined, Coed Baidd, Gwenster, and Rhos Eira. Taliesin gives only the smallest amount of detail about each encounter. This was probably a standard formula in widespread use for flattering kings, and probably Arthur’s bard wrote a very similar poem to celebrate a selection of Arthur’s greatest battles.

In Rheged arise, Taliesin says to Urien, “I have watched over you even though I am not one of yours” and the praise poem To Cynan Garwyn implies that he may have come originally from Powys, serving Cynan, King of Powys, before moving north to Rheged.

Taliesin was loyal to the British cause above all else and when he saw Urien’s power beginning to wane at the close of the sixth century he shifted his efforts to the support of Gwallawg, King of Elmet: there are two poems in praise of Gwallawg, The Battles of Gwallawg and Gwallawg is other. Urien was at that time still alive and it was probably then that Taliesin wrote The Conciliation of Urien as a way of apologizing to the old king who was nettled at Taliesin’s shift of loyalty.

Several important themes emerge from Taliesin’s poems. One is that the kingdoms of the north were allied in a loose confederation against the Anglo-Saxon menace, sometimes under one king—sometimes under another—and Urien is portrayed as one of these commanders-in-chief. Another theme is the in-fighting that went on among the British and the wide geographical range of sixth-century military expeditions against other British kingdoms. Cynan of Powys is described as waging war on Brycheiniog, the Wye Valley, Gwent, Dyfed, Gwynedd, and Dumnonia, and Urien “ranges himself” against Powys.

There are also insights into the motives for warfare. The Battle of Wensleydale mentions that Urien is king of the rustlers, farm leader, suggesting that acquiring livestock was a prime motive for fighting. Acquiring wealth was essential in order to make the show of gift-giving that was the hallmark of great kingship. In You are the best, Urien is Christendom’s most generous man: “a myriad gifts you give to the world. As you hoard, you scatter.” In Gwallawg is Other, Taliesin tells us, “Hoarding kings are to be pitied … they cannot take their riches to the grave: they cannot boast about their lives.”

A further recurring theme is the importance of horses in Celtic warfare. The Spoils of Taliesin say, “fine are fast cavalrymen” and “fine is the rush of a champion and his horse.” Taliesin was unable to go on an expedition with Urien, but wished that he could have gone “on a frisky horse” to be “with the foragers.” The sound of battle was dominated by the horses: “From the stamping of the horses a furious din.” Horses ranked among the most highly prized gifts: Taliesin claimed that Cynan gave him “a hundred steeds with silver trappings.”

Several so-called Taliesin poems have to be rejected because they contain contaminating later material or are written in a metaphysical prophetic style, such as The Battle of Godeu. Medieval copyists tended to expand and develop early material that was too terse or cryptic for medieval taste. The nature of the problem is most transparently seen in a poem about Gwallawg ap Lleenawg in The Black Book of Carmarthen, where a medieval monk has written an additional stanza—his own—in the margin (see Myths: The History of Taliesin).

A woven woolen cloth with patterns consisting of criss-cross bands in various pre-dyed colors. The name “tartan” is thought to derive from the Gaelic word tarsainn, meaning “across,” because the bands of color go across one another. Tartan is particularly associated today with Scotland, but its use in antiquity was certainly more widespread.

Tartan was worn by the Iron Age Celts of the Hallstatt culture in central Europe. The earliest known tartan has been found near Salzburg, dating from about 400–100 BC. The earliest example of Scottish tartan dates from the third century AD; a piece found at Falkirk was stuffed into the mouth of a pot containing 2,000 Roman coins. This was a simple check design made out of two natural wool colors: one light and the other dark. This was a native British fabric and it is likely that the pre-Roman Iron Age Britons wore this and other tartan patterns (See Dress).

Diodorus Siculus wrote that the Gauls wore “a striking kind of clothing—tunics dyed and stained in various colours, and trousers which they called by the name of bracae; and they wear striped cloaks fastened with buckles, thick in winter and light in summer, picked out with a variegated small check pattern” (See Plaid).

Tartans became associated with clans at the time of the Jacobite rebellions, as the main Jacobite supporters were tartan-wearing Highland clansmen. Before the middle of the nineteenth century, tartans were specific to districts, not to clans. Local weavers produced tartans to suit local preferences and they were restricted by the availability of local dyes. It was noted in 1703 that in the Western Isles the tartans varied from island to island.

The suppression of the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion meant a clampdown on all aspects of Highland culture, which included tartans. In an attempt to bring the Highlands to heel, the 1746 Dress Act banned the use of tartans. Forty years later the act was repealed and during the nineteenth century there was a revival in the use of tartan.

The great craze for tartan began with George IV’s visit to Edinburgh in 1822, when Sir Walter Scott, the novelist and founder of the Celtic Society of Edinburgh, encouraged the king and all his guests to wear tartan costumes. One observer scoffed at “Sir Walter’s Celtified Pageantry,” but the result was a surge of interest in tartans.

This interest was fed by an 1842 book called Vestiarium Scoticum by John and Charles Hay. The content of the book was fake, and the authors were fakes too, having arrived in Scotland 20 years before claiming to be Bonnie Prince Charlie’s grandsons, which they were not. They claimed that the clan tartans allocated in their book were based on an ancient manuscript, which they were never able to produce. This book was the origin of the idea, now widespread, that certain tartans are to be associated exclusively with certain clans; in reality, anyone can wear any tartan.

Prince Albert was caught up in the tartan craze and used it to excess in his redecoration scheme for Balmoral: red Royal Stewart and green Hunting Stewart for carpets, and Dress Stewart for curtains and upholstery.

Today the two most popular tartans are said to be Black Watch and Royal Stewart. Modern chemical dyes produce strong, dark colors, but “ancient” tartan colors are lighter in shade. “Muted” tartan colors, developed in the 1970s, are a shade in between modern and ancient and represent the closest match to the tartans produced in the eighteenth century.

The idea that specific tartans have specific meanings is a modern importation. A common misconception is that red tartans were “battle tartans,” worn so as not to show blood.

New tartan designs have been commissioned in recent times in order to give Canadian provinces and American states their own tartans. These contain an element of symbolism, such as blue for lakes, green for forest, and yellow for corn. This inventive development of tartan is a symptom of the international Celtic movement, or pan-Celticism.

Ruler of the Catuvellauni tribe from about 25 BC until 10 BC, and the father or grandfather of Cunobelin.

Tasciovanus’s name means “Killer of Badgers.” His Catuvellaunian tribal capital was at Wheathampstead near St. Albans, but there was another center at Braughing and Puckeridge: two neighboring villages north-east of Hertford, where coins were minted. Tasciovanus had one of his coins inscribed TASCIO RIGON—“Tasciovanus the Great King” or “Giant King.” This boast may mark the annexation of the neighboring territory to the east of the Catuvellauni, the lands of the Trinovantes, when Tasciovanus deposed the Trinovantian king Addedomarus. This major expansion of power must have made Tasciovanus feel like an emperor.

The portrait of Tasciovanus on his coins shows him young, with Romanized short hair. This may be misleading, though, as the portrait imitates the image on coins of the emperor Augustus, even to the very high bridge to the nose.

The coins minted in the enlarged kingdom in Tasciovanus’s time imply that there were several sub-kings ruling under him, each with their own coins: Andocomarus, Diasumaros, and Rues.

See Theodoric.

See Thynoy.

In spite of the Gothic name, Theodoric, or Tewdrig, was a Celtic king with estates in both Wales and Cornwall, in about 500–530. His great namesake was still ruling in Ravenna, and the Cornish Theodoric was evidently named after him. His dates can be inferred from three independent traditions regarding Fingar, Cynan, and Petroc. He was a contemporary of King Brychan of Wales.

Theodoric saw military action in South Wales, where he was supporting his daughter Marchel in her marriage to the Irish Anlac, son of King Coronac. The interrelationships between Cornwall, South Wales, and Ireland were very complex, and the Irish attempts to colonize Wales had to be countered. It seems Theodoric was there dealing with one of these incursions.

Later, Theodoric was in Cornwall, dealing with an Irish incursion there. Fingar sailed with 770 men from Ireland to Hayle Bay (St. Ives) and Theodoric descended on these incomers and massacred them.

The Life of Cynan portrays Theodoric as a powerful king living at Goodern, close to Truro. He was also active in Brittany.

The mother of Kentigern. Thynoy (or Thaney) was seduced by a soldier, became pregnant, and was thrown off the top of Kepduf (in Irish), or Traprain Law, in a cart, but landed unhurt. She was then set adrift in a boat without oars and the waves carried her to Culross in Fife, where she was rescued by St. Servan. Then she gave birth to Kentigern.

Tighernmas, “The Lord of Death,” was an Irish High King who is supposed to have set up the cult of the idol called Crumm Cruach on the Plain of Adoration. At the feast of Samhain, he was killed in a frenzied riot.

A Catuvellaunian king; one of the sons of Cunobelin. Togodumnus and his brother Caratacus were the joint kings of the powerful Southern Kingdom at the time of the Roman invasion in AD 43. It looks as if Togodumnus ruled the lands north of the Thames River, while Caratacus ruled the lands to the south.

It seems that they did nothing to oppose the Roman landings, which was a tactical mistake. Instead they fell back to the Medway estuary and gathered their armies there. An onslaught from the Romans pushed the Britons back to the Thames, where Togodumnus was killed. This was the turning-point.

Eleven British kings decided to surrender to Rome, seeing that there was little alternative after the most powerful kingdom in Britain had been overpowered.

The Roman conquest of Britain was formally marked by a 16-day visit to Camulodunum, Togodumnus’s capital, by the emperor Claudius himself (see also Amminius, Catuvellauni).

See Dress.

The large communities of kin-related people known as tribes occupied distinct territories that varied in size, but typically might be 1,000 or 2,000 square miles (2,500 or 5,000 square km)—the size of a county in England or America.

There were too many of them across the entire Celtic realm to list, but in England and Wales there were the Brigantes, Parisi, Coritani, Deceangli, Ordovices, Demetae, Silures, Cornovii, Dobunni, Catuvellauni, Trinovantes, Iceni, Dumnonii, Durotriges, Atrebates, and Cantiaci (or Cantii).

The tribal territory or civitas was clearly defined, and made up of a large number of equally well-defined local territories known as pagi in Latin. The pagus was an identifiable physical landscape, recognizable on a human scale: perhaps a plain, a valley, or an area surrounding a lake.

See Gildas.

See Gildas.

A British tribe whose territory extended across the modern English counties of Essex and south Suffolk. They may have been responsible for founding London at the lowest fording-place on the Thames River.

In the time of Julius Caesar the Trinovantes were on hostile terms with their immediate neighbors to the west, the Catuvellauni, and probably separated from the lands of the Iceni to the north by a belt of wooded country.

Some of their kings are known: Mandubracius (ruled about 54–30 BC), Addedomarus (30 and 20–10 BC), Tasciovanus (Catuvellaunian, usurped 30–20 BC), Dubnovellaunus (10 BC–AD 10), and Cunobelin (10–41).

The Trinovantes were conquered by the Romans in AD 43. This was a familiar experience for them; they had been repeatedly conquered by the Catuvellauni.

See Religion: Headhunting.

A Celtic tribe in Gaul. Its main center was at Tours.

The most famous King of Rheged (north-west England), who held court at Cair Ligualid (Carlisle). Unfortunately most of what we know about him was written by his bard: a professional spin-doctor who was paid to praise his king. So we keep reading of his wonderful qualities: “Urien, the most liberal man in Christendom.”

He had a son called Owain, who succeeded him in about 590. Urien led a coalition of northern British kings, including Rhydderch of Clyde and Gwallawg of Elmet, in a campaign against the Angles under their king, Hussa, who were encroaching from Bernicia to the east. Urien thus became an unofficial northern dux bellorum, like Arthur in Britannia Prima some 70 years earlier.

Urien’s neighbor to the north was Mynyddawg Mwynfawr, King of Gododdin, who was based at Din Eidyn, while his neighbor to the north-west was Rhydderch Hael, King of Clyde, who fought with Urien against Thedoric of Bernicia, the leader of the Angles in the north.

In 590, Urien’s ally Morcant commissioned two men, Dyfnwal ap Mynyddawg and Llovan Llawddino of Din Eidyn, to murder King Urien out of jealousy for Urien’s all-surpassing generalship, “because in him above all the kings was the greatest skill in the renewing of battle.” They assassinated him while he was out on campaign. Urien’s bard, Taliesin, sang nostalgically of the greatness of the dead king:

Sovereign supreme, ruler all highest, the strangers’ refuge,

strong champion in battle.

This the English know when they tell tales.

Death was theirs, rage and grief are theirs,

burnt are their houses, bare are their bodies.

These are fine words, but they conceal the truth of what was happening. They convey that the warriors of Rheged were defeating the English. But death was not theirs, not theirs at all. At Arderydd, and in the murder of Urien too, the British were destroying one another, not the English (see also Rhun, Son of Urien).

See Cultures.

A Celtic tribe in Gaul, with its main center at Rouen. Before the Roman conquest, the Veliocasses controlled a large area in the lower Seine Valley. They joined the tribal coalition that resisted the Romans in 57 BC, fighting beside the Bellovaci in the last stand against the Romans.

A seafaring tribe living on the south-west coast of Brittany. The Veneti built ships powered by leather sails; the hulls were made out of oak with large transoms fixed by thick, iron nails. They built sturdily to withstand the harsh sea conditions in the Bay of Biscay.

See Cartimandua.

A leading member of the Arverni tribe in Gaul and a cousin of Vercingetorix.

Chief of the Arverni tribe in Gaul. At a crucial general council of the tribes in 52 BC, he was appointed war leader in the Gaulish resistance to the Roman conquest. We know what he looked like from a coin minted in 48 BC.

Vercingetorix was the Gaulish commander-in-chief in the major confrontation between Gauls and Romans at Alesia. In this large-scale battle, he came close to winning, but finally lost.

After formally surrendering his weapons to Julius Caesar, he was taken prisoner along with all of the Gaulish warriors. He languished in prison for five years, awaiting Caesar’s Roman triumph at the end of the Gallic War. Like a caged animal, he was to be one of the chief exhibits.

When the triumphal procession ended, no more was ever heard of Vercingetorix, but it is said that he was taken to the Mamertine prison and strangled.

King of the Atrebates in central southern England. He was expelled by the Catuvellaunian chiefs, Togodumnus and Caratacus, and fled to Rome.

A powerful king of Powys from AD 425 onward. Vortigern’s main stronghold was at Viroconium (Wroxeter). His palace stood among the ruins of the Roman city.

Vortigern is mentioned in several early sources. The Life of Germanus, written in about 470 by Constantius, presbyter of Lyons, gives the following information:

He had three sons, whose names are Vortimer, who fought against the barbarians [non-Christian Saxons] as I have described; the second, Cateyrn; the third, Pascent, who ruled over the two countries called Builth and Gwerthrynion after his father’s death, by permission of Ambrosius, who was the great king among all the kings of the British nation. A fourth son was Faustus, who was born to him by his daughter. St Germanus baptized him, brought him up and educated him. This is his genealogy. Fferfeal, who now rules in the countries of Builth and Gwerthrynion, is son of Tewdwr. Theodore is king of the country of Builth, the son of Pascent, so of Gwyddgant, son of Moriud, son of Eldat, son of Elaeth, son of Paul, son of Meuric, son of Briacat, son of Pascent, son of Vortigern the Thin, son of Vitalis, son of Vitalinus, son of Gliou. Enough has been said of Vortigern and his family.

Constantius has included too many generations between his own time and Vortigern’s; ten generations back in time from 470 would put Vortigern in the second century when he obviously belongs to the fifth. Germanus nevertheless picked up significant information on his visits to Britain in 429 and 445. In particular he saw that Vortigern was a powerful king more or less in overall control in southern Britain.

It is possible that Vortigern was a royal title rather than a personal name; it appears to come from Vawr-tighern, meaning “supreme leader” or “overking.” This is supported by the mentions in documents of more than one king called Vortigern. An account, by Nennius, of a war fought in the fifth century between Ambrosius Aurelianus and a chief called Vitalinus may in fact be about Vortigern. Some scholars think that Vitalinus might be Vortigern, and that Vitalinus might be a personal name and Vortigern a title. Gildas calls him a “tyrant” and he may have meant “powerful king.” One view of Vortigern is that he was responsible for introducing (or reintroducing) into Britain the Irish practice of High Kingship.

If Vortigern is seen as one king, he ruled as High King of southern Britain from around 425 until 447. What happened to him then is unclear, as there are several different lurid versions of his fate. Vortigern the Elder, Vortigern Vitalinus, may have died or abdicated in 447 and been replaced by Vortigern the Younger, whose personal name may have been Britu.

The closing years of Vortigern the Elder’s reign were darkened by a double disaster: an overt attack from the north by the Picts and a more sinister and treacherous attack from the east by people of Germanic origin—Angles, Saxons, and Jutes. Vortigern unwisely took on Jutish mercenaries under their leaders Hengist and Horsa in an attempt to keep the Pictish invaders from the north at bay, while at the same time opening the door to more Jutes settling in Kent.

A third attack came from within the British community. A nobleman called Ambrosius the Elder launched a rebellion against Vortigern in 430, apparently in protest against his use of Germanic auxiliaries and the costs that this must have involved in increased taxation. But by 440 Vortigern was enlisting more mercenaries from the same source. In the following year their numbers were large enough to begin demanding higher payment from Vortigern, who gave them the Isle of Thanet (East Kent). Gildas, writing a century afterward, was characteristically outspoken:

To hold back the northern peoples, they introduced into the island the unspeakable Saxons, hated of God and man alike… What raw hopeless stupidity! Of their own free will, they invited in under the same roof the enemy they feared worse than death…

The Saxons later narrated the story from their side in The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle:

449: In this year Mauricius and Valentinian obtained the kingdom and reigned seven years. In their days, Hengist and Horsa, invited by Vortigern, King of the Britons, came to Britain at a place which is called Ypwines fleot [Ebbsfleet] at first to help the Britons, but later they fought against them. They then sent to Angeln, ordered [them] to send more aid and to be told of the worthlessness of the Britons and the excellence of the land. They then sent them more aid. These men came from three nations of Germany from the Old Saxons, from the Angles, from the Jutes.

The dangers of employing Hengist’s and Horsa’s mercenaries were now obvious, and Vortigern’s son Vortimer led an army to drive the Jutes back though Kent and confine them to the Isle of Thanet, at that time still separated from the mainland by a broad stretch of open water, the Wantsum Channel. Vortimer himself was killed in the fighting.

Three independent sources support this sequence of events. Vortigern’s campaign against the Jutes was successful, but in the process he lost two of his sons and his forces were sapped by plague. The Jutish army remained bottled up in Thanet for five years before breaking out in 465. The British response to this new crisis was to rebel against Vortigern, in about 459. As the situation became increasingly unstable and unsafe, many of the surviving members of the British nobility in eastern England emigrated to Brittany.

Vortigern invited Hengist to attend a conference with 300 members of the British Council. Hengist told his men to conceal daggers and then to slaughter the unarmed elders. It was said that only Vortigern himself was left alive, but now a broken man. At this point he disappeared from history. He was toppled from his position as commander-in-chief or pendragon—very likely deposed by his successor, Ambrosius.

A king of Demetia (Pembrokeshire), son and successor of Aircol. He became king in 515. The Vortipor Stone at Castell Dwyran appears to be his grave: certainly this inscribed standing stone was raised as a memorial to him. The inscription, MEMORIA VOTEPORIGIS PROTICTORIS, means “The memorial of Vortipor the Protector.” The sixth-century historian Gildas corroborates this with his reference to “Vortipor, the usurper of Demetia.”

The warrior-prince burials from both Hallstatt and La Tène cultures show an interest in fighting. It looks as if, just as with the Mycenaeans, high status was inextricably tied up with outstanding performance on the battlefield. To be a leader, you had to be a war leader.

The classical writers who described the Celts commented particularly on their aggressive and warlike nature. Diodorus Siculus wrote:

The Gauls are terrifying in appearance, with deep-sounding and very harsh voices… Their armour includes man-sized shields, decorated in individual fashion. On their heads they wear bronze helmets.

Warriors, according to Julius Caesar, acquired status above that of freeman. Warrior-princes rode to battle in chariots, collected the heads of enemies as trophies (see Religion: Headhunting), performed feats of skill and engaged continually in individual duels as well as skirmishes.

There are many bronze figurines to show us what Celtic warriors looked like in action. A third-century BC spearman (found near Rome) is naked apart from a torc, a horned helmet, and a belt. The belt, which was commonly worn even by warriors who were otherwise naked (see Symbols: Nudity), has rarely been commented on. It was worn to hold a knife, sometimes tucked through just behind the hip. The knife was used to finish off a wounded enemy—and sometimes to cut off his head as a trophy.

Warriors went into battle looking as ferocious as they could. This meant getting themselves into a strange state of mind and pulling remarkable faces (see Symbols: Shapeshifting).

Their style of fighting was described by Roman writers, but in contradictory ways. Livy described them as having neither discipline nor strategy and surging about in uncontrollable hordes. But this is in the context of the Celts’ third-century BC invasion of northern Italy, and the Romans were experiencing the sharp end of it. Livy had every incentive to portray this act as a feral attack by a barbarian horde. Caesar gives a very different impression of the Celts in his Gallic War. The Gauls calculate and trick, and carry out some complicated and dangerous maneuvers. They must have been commanded by imaginative chiefs with ideas of strategy and fairly effective chains of command, even if they did not always remain in full control of events.

In the early Iron Age the Celts were individual fighters and skirmishers. They formed recognizable armies only at a late date, though they were able to do this when the crisis was great enough.

Success depended on collaboration. The Celts did form military alliances, and they could present formidable opponents to the Roman legionaries, but those alliances were fragile. In the end, the Romans were able to conquer Gaul and Britain by virtue of the disunity of the Celtic tribes. Tacitus commented, “They eventually failed because they are distracted between the jarring factions of rival chiefs. Indeed, nothing has helped us more in war with their strongest nations [the tribal confederacies of the British] than their inability to co-operate.”

Some of King Arthur’s Wonderful Men was written in the tenth century but based on earlier documents reaching back to the Dark Ages. The warriors described as the members of Arthur’s war-band are colorful, larger-than-life saga heroes. Morfran, son of Tegid, was said to be so ugly that at the Battle of Camlann no man raised a weapon against him, thinking he was a devil. Sandde Angel-Face survived Camlann because he was so beautiful that people thought him an angel. Other men who fought beside Arthur were Gwefl, son of Gwastad, Uchdryd Cross-Beard, Clust, son of Clustfeinad, Gilla Stag-Leg, Gwallgoig, and the three sons of Erim: Henbeddestr, Henwas the Winged, and Scilti the Light-Footed.

Some of the claims made on their behalf were fanciful in the extreme, and perhaps we can hear, dimly, the sort of wild drunken boasting that might have accompanied many a feast. Medr, son of Medredydd, could shoot a wren in Ireland from Kelliwic in Cornwall. Gwaddu of the Bonfire’s shoes gave off sparks. Osla of the Big Knife could bridge a river with his magic knife. Drem, son of Dremidydd, could see Scotland from Kelliwic. Finally, there was Cachamwri, who was Arthur’s servant.

Weapons and armor changed during the Iron Age. In fact on the European mainland there were significant changes even within the La Tène period, about 460 BC to 50 BC. La Tène A1 was a transition from the Hallstatt culture to the solidly Celtic La Tène, beginning in 460 BC. Offensive weapons were dominated by spears. The warriors’ graves were fitted out with several spears: usually a single large fighting spear and several lighter throwing spears or javelins. Swords were usually short side-arms, with blades 16–20 inches (40–50cm) long; these were little more than substantial daggers and designed for stabbing in close-quarter fighting. Metal shield fittings were rare, often only a reinforcement for the grip. It was common for belt-hooks to be made of ornate openwork. At this stage the warrior-elite, the nobles, were fighting mainly from chariots.

By 400 BC, the start of La Tène A2, slight changes were under way. Swords became more common in warrior graves, and with a fairly standard sized blade of 24 inches (60cm). Spears were still very much in use, and often in pairs or larger numbers. The Waldalgesheim Style (or Vegetal Style) appeared. This is used on helmets, scabbards, and personal ornaments, often covering every inch of the object with decorative line. An S-form using dragon or bird images appeared on scabbards. Shields were still mainly organic (wood or leather), but with metal fittings, and sometimes a metal rim. There was a strong emphasis on chariot warfare.

From 300 BC onward (La Tène B), the Celtic warrior reached the height of his power. The most common type of warrior was the heavy infantryman, who fought not only for his own tribe but fought for others as a mercenary. Warrior aristocrats fought as cavalrymen or as chariot warriors; cavalry was on the increase, with chariot warfare now on the decrease. The standard fighting gear was now a single large fighting spear, a sword, and a shield. Swords were now slightly longer, with blades 26 inches (66cm) long, with a midrib, and were heavier. On shields, metal umbos (bosses) began to appear: initially as twin plates nailed to the wooden boss, and later as the strap-boss. Metal rims were still uncommon.

In La Tène C, from 260 BC onward, the standard warrior gear remained the same: heavy fighting spear, sword, shield, and now always an iron belt chain. The infantry were still the most common type of soldier, but cavalry were becoming more important. The typical sword was longer and thinner, a rapier with a blade that was lens-shaped in cross-section; blade lengths vary, but up to 32 inches (80cm) long. Later blades had almost parallel sides. Spears also changed in shape; some developed a long, tapering quadrangular point. The artistic style of this phase was more restrained, with sparer decoration using triskeles and flowing asymmetrical lines.

In La Tène D, which lasted from about 125 BC to AD 100, the Celtic warriors reached their final flowering. Professional warriors included an important class of noblemen who were cavalrymen, and also large numbers of infantrymen who were more lightly armed. The equipment consisted of a long, heavy fighting spear or lance, a long cutting sword, and often a helm. The sword was large and its blade was parallel-sided for most of its length; the point was usually short. This design was less for stabbing, more for cutting, with a blade often 32–6 inches (80–90cm) long.

Shields sometimes had a spindle umbo, but as time passed the spindle disappeared and a domed metal boss appeared. The decorative style became simpler and severer.

Whether the Iron Age Celts were more warlike than other, later peoples is hard to gauge. They had a reputation for being quarrelsome, fierce, and ready fighters. In recent years this warlike image has been downplayed. Even the massively fortified hillforts have been presented as peaceful settlements, with probably a ritual and ceremonial function, with the ramparts put up mainly for show.

But new evidence from Fin Cop, a hillfort in the English Peak District, south-west of Sheffield, shows that forts did have a military function, and that defense against violent attack was very necessary. Fin Cop’s defenses were built in haste in about 420 BC, in response to a real and immediate threat. The defensive wall 6.5 feet (4m) high on the fort’s eastern perimeter was pushed over into the ditch beside it, leveling the fortification. This wall was attacked and destroyed, and its stones pushed on top of the corpses of scores of people. The most gruesome discovery was that of the skeletons that could be identified, all were women and children—none were warriors. They had no bone damage, which suggests that they all died of soft-tissue injuries, perhaps by having their throats cut. It was a massacre of civilians, and it happened within a few years of the fort being built.

See Beuno.

See Petroc.

See Symbols: Oak.

A British ascetic who died in 588. He traveled to Tours from Britain on his way to Jerusalem in 578; a very conspicuous figure wearing nothing but sheepskins. He ate nothing but uncooked vegetables and drank only sips of wine. Gregory, the bishop of Tours who wrote a detailed History of the Franks, was impressed by his extreme abstinence and ordained him priest, hoping to keep him at Tours.

In 586 Winnoc fell ill from malnutrition and took to swigging large quantities of wine. He often became drunk and attacked people with a knife or a stone. He was so violent that he had to be chained up. After two years in chains, he died.

This episode was the result of prolonged undernourishment. It goes a long way toward explaining the bad temper, intolerance, and wild and violent behavior of some of the Celtic “saints.” It also explains why the majority of monks were against this intensity of self-denial and why Gildas condemned St. David.

See Paul Aurelian.

See Places: Lindow Moss.

Celts were reluctant writers. They rarely wrote records of any kind. The Anglo-Saxon colonists in England famously kept a summary record of their history, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, but the Celts appear to have felt no need to make such a self-account. They do not speak to us directly and this makes them less accessible to us. What we know about them we know through archeology or through the writings of contemporary literate societies. We know about the Gauls and the Britons thanks to the writings of Roman historians and commentators.

The Druids passed on their knowledge by reciting it from memory. Because knowledge was of divine origin, it had to be kept secret, reserved only for transmission to novice Druids. Here we can see why the Druids shied away from writing. They were not ignorant of writing; writing was available. The Minoans and Mycenaeans had developed well-established written scripts by 1500 BC, and the Romans were great documenters of everything that happened. The Druids, and the Celts generally, chose not to write their knowledge down, which to us is a great loss, but to them it meant that they could control who had access to it and who did not. They excluded us by refusing to write down what they knew.

The Celts did use writing for commercial transactions, and when they did they used the Greek alphabet. One Greek usage came to be what has been described as a Gallic-Latin spelling habit. A Greek “X” was used to represent the Celtic “ch” sound, as in the Scottish loch, especially when followed by the letter “t.” This is seen in inscription from Gaul, such as TIOCOBREXTIO on the Coligny calendar. In South Shields in Britain there is the inscription ANEXTIOMARO. It also crops up on some coins of the British King Tasciovanus in the form TAXCIAV [ANOS] in about 20 BC–AD 10. This custom suggests a deliberate modification of the Roman alphabet, using Greek, by Celtic scholars, to accommodate phonetic values that existed in Celtic speech but not in Latin.

It is also an exciting possibility that writing was rather more common in the Celtic world than we may have thought. There is evidence that papyrus may have been imported into Britain in the period between the invasions of Julius Caesar and Claudius. If the British were importing papyrus, it can only have been for the production of documents; both imply a higher level of literacy and more widespread literacy in Britain than we normally allow for.

The situation in Ireland seems to have been quite different, with a society that was wholly or almost wholly illiterate, though with elaborate systems of oral transmission. It was only from about the fourth century AD that the Irish adopted Ogham as an inscriptional alphabet.

The annals recording the pedigrees of Celtic aristocrats were written down from the fifth century AD, probably under the influence of Rome. It seems probable that the genealogies were committed to memory and recited from time to time, and so passed from generation to generation orally.

The Welsh and English chronicles seem to base the structure and subject matter of their earliest entries on the Irish Annals. The Welsh Annals for the fifth and sixth centuries have 18 out of the 22 earliest entries copied straight from the Irish Annals. The Irish pedigrees were more developed, more complete, and more ancient than any other in Europe. This may be a reflection of Ireland’s freedom from Roman invasion; the Celtic way of life was allowed to continue uninterrupted. An astonishing 20,000 named Irish people are known from the Irish Annals, from the period before AD 900.