See Maryport.

This very early Celtic name for Britain was first noted about 525 BC, when a traveler’s description located Ireland “alongside the island of the Albiones.” In the Iron Age the name “Alba” seems to have referred to the whole of the island of Britain—the land of the Albiones.

Later, the phrase “the men of Alba” was used to describe the Dark Age Irish colony of Dal Riada (a small kingdom in south-west Scotland) and this led to a narrowing of the word’s meaning; from the ninth century AD “Alba” was local to Scotland. Once what we now call Scotland was recognized as a distinct area, it all became known as Alba, and then Albany. In the tenth century this was Latinized—(for us) rather confusingly—as Albania.

The new Scottish Parliament has its name translated into Gaelic as Pàrlamaid na h-Alba, and to that limited, almost heraldic, extent Scotland has once again become “Alba.”

See Alcluith.

The Dark Age kingdom of the Clyde. The name of the kingdom was also used to denote its chief stronghold, which was perched on Dumbarton Rock: Alcluith meant “Clyde Rock.” The later name of the adjacent settlement, Dumbarton, is derived from Dun Breatann, “Fort of the Britons,” which seems also to have referred to the stronghold up on the crag.

In AD 731 Bede called it “a town of the Britons, strongly defended right down to the present day.” The site is mentioned in the seventh-century Life of Columba, which refers to “King Roderc [= Rhydderch] son of Tothal who reigned in Alclut.” The fortress is spectacularly defended by natural precipices falling on three sides into the Clyde estuary. In the Dark Ages there was a timber rampart defending it on the fourth side.

A major Gaulish oppidum (town) and fortress of the Mandubii tribe; it was the stage set for the decisive event in the Roman conquest of Gaul.

Developed on a hill surrounded by river valleys, Alesia was strongly defended. In 52 BC, it was the scene of a remarkable siege, which marked a turning-point in Julius Caesar’s campaign in Gaul.

Caesar had subdued the Eburones tribe under their chief Ambiorix in 54–53 BC. Then they rose up again, surprising the Roman army in an ambush in which Caesar lost a great many men; this was his first clear defeat in Gaul.

On the initiative of the Aedui, a general council of the tribes of Gaul was called at Bibracte. Only the Remi and Lingones decided to maintain their alliance with Rome: the rest decided that the time had come to rebel. The council appointed Vercingetorix, chief of the Arverni tribe, as the commander-in-chief (or war leader) of the Gallic armies.

The first indication of this new concerted resistance to the Roman conquest was the massacre of all the Roman settlers in Orléans by the Carnutes tribe. This was followed by massacres of Roman citizens in other major towns in Gaul.

Caesar was encamped in northern Italy at the time, but understood the seriousness of the revolt, rallied his army in haste, and crossed the snow-covered Alps into Gaul to try to retrieve the situation. He was in command of the Roman army and was supported by cavalry commanders Mark Antony, Titus Labienus, and Gaius Trebonius. Four legions were sent under Labienus to deal with the Senones and Parisii in the north, while Caesar, with five legions, pursued Vercingetorix.

The Roman and Gaulish armies met at the hillfort of Gergovia: a strong defensive position to which Vercingetorix had made a tactical withdrawal. It was such a strong position that Caesar decided to retreat in order to avoid defeat.

There were several skirmishes during the summer of 52, and Vercingetorix withdrew to the fortress town of Alesia, trying to avoid a formal pitched battle against Caesar’s troops.

Caesar could see that a direct attack on Alesia would be unwise and decided instead on a siege. There were 80,000 Gaulish warriors garrisoned there, in addition to the civilian population, and Caesar hoped to starve them out fairly quickly. To prevent escape and foraging, Caesar had his own encircling fortifications built: a circumvallation consisting of 29 miles (47km) of earthworks 13 feet (4m) high. This was followed inward by two ditches 15 feet (4.6m) wide and 15 feet (4.6m) deep, filled with water from nearby rivers. Caesar added man-traps and evenly spaced watch towers. It was a masterpiece of large-scale Roman military planning, and indeed Alesia is seen as one of Caesar’s greatest triumphs.

Gallic horsemen came out to raid the fortification works, hoping to keep gaps open through which they might escape. In fact one cavalry detachment did manage to escape, and Caesar guessed that it would seek reinforcements from elsewhere. Anticipating that more Gauls would arrive, he constructed a second line of fortifications, the contravallation, this time facing outward. He was laying plans for a siege, but he was also preparing to be besieged himself.

Inside Alesia, conditions were worsening. The Mandubii decided to send their women and children out, hoping to save some food for the warriors and anticipating that Caesar would take pity on them and open a gap to let them out. But he didn’t. He ordered that nothing should be done. The women and children were cruelly left to starve to death in the no-man’s-land between the Gauls and Romans. This inhumane act was a devastating blow to the Gauls’ morale. Vercingetorix tried to keep their spirits up, but some of his warriors were ready to surrender.

Then a Gaulish relief force arrived and the Gauls inside Alesia decided that they would fight on. The relief force, under Commius, attacked Caesar’s contravallation wall, while Vercingetorix directed the Gauls inside Alesia to attack Caesar from within. This tactic was at first unsuccessful, but when repeated Caesar was forced to give up some of his fortifications; only quick action by Antony’s and Trebonius’s cavalry saved the Romans.

By this stage living conditions had become difficult for the exhausted Roman troops. Rationing was introduced. On October 2 a cousin of Vercingetorix, Vercassivellaunus, led 60,000 Gauls in an attack on one of the weak points in Caesar’s fortifications. This huge onslaught threatened to overwhelm the Romans, and Caesar rode around the perimeter in person to rally the legionaries and keep them in position. It looked as if the massively outnumbered Roman army would be annihilated. In desperation, Caesar ordered a force of 6,000 Romans to attack the relief force from the rear. This so surprised both the relief force and the Gauls inside Alesia that they fell apart in panic and began to retreat. Once they started to retreat, it was easy for the merciless Romans to hew them down. Caesar had turned imminent defeat for Rome into victory.

When, the next day, Vercingetorix surrendered, he did so to save his warriors from being forced into a fresh battle that would destroy them—and to save his horses. Addressing an assembly, he said that he had not undertaken the war for private ends, but in the cause of national liberty. And since he must now accept his fate, he placed himself at their disposal to make amends to the Romans as they thought best, either by killing him or handing him over alive. He solemnly offered himself to save his army; it was the Roman formula of devotio, a rite that Caesar would have recognized and respected.

The garrison force and the relief force were taken prisoner and sold into slavery, apart from the warriors of the Aedui and Arverni tribes, who were pardoned and released; this was done in order to secure the alliance of those two important tribes.

See Symbols: Labyrinth.

There was an important religious cult focus on the eastern coast of the island, next to the Menai Strait. Normally the Romans left native temples and sanctuaries alone, but this one was singled out for destruction. It was thought to be an important focus of Druidical power, and Suetonius Paulinus took his troops there to put it out of action once and for all. Tacitus described the attack:

He prepared to attack the island of Mona [Anglesey], which had a powerful population and was a refuge for fugitives. He built flat-bottomed boats to cope with the shallows. In this way the infantry crossed [the Menai Straits], while the cavalry followed by fording or swimming by the side of their horses.

On the shore opposite stood the opposing army with its dense array of armed warriors, while between the ranks dashed women, in black attire like the Furies, with hair dishevelled. All around, the Druids, with hands uplifted, invoked the gods and poured forth horrible imprecations. The novelty of the sight struck the Romans with awe and terror, so that as if they were paralyzed they stood motionless, exposed to wounds.

Then, urged by their general’s appeals and mutual encouragement not to quail before a troop of frenzied women, they bore the standards onwards and beat down all resistance, and wrapped the Britons of their own torches. A garrison was established to keep the conquered in subjection, and their groves, dedicated to superstition and barbarous rites, were levelled to the ground. They [the Britons] deemed it a duty to cover their altars with the blood of captives and to consult their gods through human entrails.

Whether Suetonius Paulinus was correctly informed or not about the importance of the sanctuary on Anglesey or the Druids is impossible to know, but the Druids were widely suspected of being subversive; they were regarded as enemies of Rome. It may not be a coincidence that at exactly that moment the Boudiccan revolt erupted in England (see People: Boudicca). Suetonius Paulinus had to get his troops across Britain quickly to put down the rebellion.

A great battle, the Battle of Arderydd, was fought at Longtown on the shore of the Solway Firth in 573. This was remembered in the Triads as one of the Three Futile Battles of the Island of Britain: “the action of Arderydd, which was brought about by the cause of the lark’s nest.” This strange, cryptic remark may be fairly easily explained. The Lowland Scots word for “lark” is laverock, and there is an ancient castle site on the northern shore of the Solway Firth that is called Caerlaverock, literally “The Fortress of the Lark” or more poetically “The Lark’s Nest.” It is close to the mouth of the Nith River. The battle was remembered as being fought for possession of the Scottish shore of the Solway Firth.

The Longtown river-crossing further to the east, at the head of the Solway Firth, was an important strategic point; it was the crossing-place of the Roman road from the kingdom of Rheged into the kingdom of Clyde. The site was controlled by the stronghold of King Gwenddolau, son of Ceidio; this may have stood at Carwinley, nearby. The king was one of the leading combatants who died in the battle in and around his own fortress.

Gwenddolau had a bard, like all other Dark Age Celtic kings, but his bard was called Myrddin, which draws us to look more closely at him. Myrddin took no part in the battle, but watched it. When he saw his lord killed, he went mad and became a hermit in the Wood of Celidon, perhaps between Carlisle and Dumbarton. By the eleventh century, this had become:

The Battle of Arderydd between the sons of Elifer and Gwenddolau the son of Ceidio; in which battle Gwenddolau fell; Merlin became mad.

Elifer is Eleutherius of York, so the battle was of the kingdoms of Rheged and York—a classic conflict among Britons. It may have been Myrddin himself who wrote the verse in The Black Book of Carmarthen:

I saw Gwenddolau in the track of kings,

collecting booty from every border,

now indeed he lies under the red earth,

the chief of the kings of the North of greatest generosity.

See Hohenasperg.

One of the names of the Underworld; the Land of the Dead ruled by Arawn. It is the Celtic equivalent to the Norse Valhalla; the magical, Otherworldly island to which King Arthur was taken, either to die or to be healed, after his final battle. There are many theories about the location of Camlann, this last battle; it is likeliest to be on the Eden River just north of Dolgellau in North Wales, where Arthur was ambushed and betrayed by Maelgwn of Gwynedd. If he was rescued from the battlefield, the safest route out of enemy territory would be to the west, into the Irish Sea. Some have thought that Bardsey Island off the tip of the Lleyn Peninsula might be Arthur’s final resting-place.

There are several, perhaps separate, traditions of magical Otherworldly associations in and around the Irish Sea. The Isle of Man was the abode of the Irish sea god Manannán, but he was also associated with the supernatural island of Emhain Abhlach, “Emhain of the Apple Trees,” which the old Celtic literature identifies with the Isle of Arran in the Firth of Clyde. The island name Abhlach is very close in form to Avallach, the name of the Lord of the Dead, and Avalon was the realm of Avallach.

There is also a lonely spot along the north coast of the Irish Sea, the Scottish shore, which has a strong claim to be Avalon. The Whithorn peninsula was in earlier times called Ynys Afallach, literally “The Island of the Lord of the Dead.” It was never literally an island, though it was fairly remote from the rest of Scotland. Whithorn itself (Ynys Wydryn) was a monastery that had the unique distinction of being regarded as the holiest place in Britain (or Ireland), “The Shining Place.”

In Christian Celtic Britain in the Dark Ages there were Three Perpetual Choirs: religious houses where services were chanted or sung continuously. One was Cor Emrys, which was at Mynydd-y-Gaer. The second was Llantwit Major. The third and holiest was the Cor of Bangor Wydryn at Ynys Afallach, and this was surely the fittest place to take the dying overking, the most successful British leader of battles.

One strange and Otherworldly aspect of Arthur’s rest in Avalon is the idea of his being in some sort of suspended animation there, somehow not quite dead but capable of being recalled to life. Even stranger is that this idea actually preceded Arthur’s lifetime. Stories of a sleeping Arthur entombed in a cave or on an island were shaped by pre-Arthurian Celtic beliefs. In the first century AD, a Roman official called Demetrius visited Britain and noted one of the few myths of the British ever to be recorded objectively in plain, straight terms. His report was transmitted by the writer Plutarch in his book On the Cessation of Oracles. It told of an exiled god, whom he called Saturn, lying asleep in a cave on an island—a warm place in the general direction of the sunset.

Probably both of the cave stories about Arthur’s end date back to pre-Arthurian beliefs, or those beliefs added a mythic resonance to the actual events of Arthur’s last months. Some of the story of Arthur is history, and some of it is myth (see Religion: Otherworld).

See People: Bituriges.

See Maiden Castle.

At Badon, a great battle took place in which the British won a major victory over the Saxons. It was Arthur’s first recorded battle in the year 516. Its outcome was so decisive that it held back the Saxons for several decades, and it was largely due to Arthur’s exploits during this battle that he owes his reputation as a great warrior.

Several locations for Badon have been proposed, but there are early references to the city of Bath in which the name is spelt Badon—for example, in The Wonders of Britain, Nennius refers to “the hot lake where the baths of Badon are”—and so the likeliest battle site by far is Little Solsbury Hill, about 2 miles (3km) north-east of Bath. This was on the eastern frontier of Dumnonia, at the point where the old Roman road, Fosse Way, came down the eastern valley-side from Banner Down toward a crossing-place on the Avon River at Bath. In the sixth century this was a key location, right on the frontier between Celt and Saxon, and would have been a natural access point to the Celtic kingdom for an advancing Saxon army. Little Solsbury Hill, which had a small fort on its summit, was an obvious vantage point from which the British warriors could have watched the invaders approaching from the east or north-east and then descended to attack as they passed below. The Saxons would have been caught between the steep valley side and the river.

In the annals there is a strange description of Arthur carrying a cross on his shoulders. This may be explained by the misreading of the word for “shoulder.” The Old Welsh for “shoulder,” scuid, is very similar to the Old Welsh word for “shield,” scuit. Scribes regularly read whole phrases from the documents they were copying and muttered them to themselves as they wrote. It was easy to make mistakes, especially when words both looked and sounded similar to other words. So the original description may have read, “Arthur carried the cross of our lord Jesus Christ on his shield.” The image of the cross could easily have been painted onto the shield, or designed into the shield’s metalwork, or embroidered into a fabric covering for the shield. It may be significant that high-ranking officers in the late Roman army frequently carried portraits of emperors on their shields. It would be quite logical for a Christian British commander-in-chief educated in the late Roman tradition to carry an emblem of Christ: after all, he recognized no earthly overlord.

The hammering of the Saxons in the Battle of Badon brought about a major change. For a couple of decades the western frontier of the Saxon world was fixed.

See Avalon.

Sulis was a Celtic goddess with associations with the sun. The temple of Sulis was the highest-profile spring sanctuary in Britain, drawing in pilgrims not only from Britain but from overseas as well. The mineral springs here are unusual in being hot springs, and in being very prolific—a quarter of a million gallons a day.

The site began as a cult focus on the floor of the marshy valley in the Iron Age. Then, during the Roman occupation, it was lavishly developed, with Sulis herself being identified with the Roman goddess Minerva, though the name of Sulis was invariably given priority: Sulis-Minerva. The Romans called the place Aquae Sulis, “The Waters of Sulis.”

The Roman engineers transformed the natural spring and its associated pool into a large rectangular ornamental pool, enclosed by a Greco-Roman-style temple. There were also subsidiary buildings, including baths. The temple dates from the time of Nero.

Visitors threw large numbers of coins and lead curse tablets into the pool. The coins were frequently deliberately damaged, to “kill” them so that they could travel across to the Otherworld: a practice that was common to other ancient cultures. Damaging grave goods would also have the practical value of rendering them worthless to potential thieves.

Sulis is mentioned in many of the dedications at Bath, and she was depicted there in a huge and imposing classical-style statue of gilded bronze; unfortunately only her magnificent head has survived.

See Religion: War God.

See Alesia.

See Symbols: Labyrinth.

See Religion: Damona.

See Religion: Boanna.

See Religion: Grannus.

A massive drum-shaped tower standing on the south coast of Rousay and looking out across Eynhallow Sound toward the main island of Orkney. Built about 2,000 years ago, it may have been raised partly to mark territory in an imposing way. It was located on a defensive site: a headland between two narrow geos, and a stone rampart and ditch were added on the landward side—so evidently defense was an important consideration.

Another site consideration may have been the presence of a fine Neolithic tomb, Midhowe; doubtless its large, flat roof-slabs, probably then exposed to view, were an attraction to Iron Age builders. They were dragged off the tomb and used to make the huge room dividers in the interior of the broch. The two monuments stand side by side.

The broch originally had a range of ancillary buildings. Coastal erosion, a problem for all shore sites such as Midhowe, has greatly damaged the remains of these outhouses. The broch itself still stands to a height of 14 feet (4.3m) and the interior is well preserved.

There is also a spring in a crack in the rocks, which even during a modern archeological excavation went on filling the Iron Age water tank with water that was clear and drinkable.

One surprise is that the Iron Age inhabitants of the Broch of Midhowe had Roman goods: pottery and a ladle. This remote location was well outside the arena of Roman activity, so these objects must have been acquired as gifts or by trading with Britons further to the south.

One of the finest and best-preserved prehistoric buildings in northern Europe, built about 2,000 years ago. It featured in the Norse colonization of Orkney and was even mentioned by name in the Orkneyinga Saga:

Then Erland gathered men together and took up his residence in the Broch of Mousa and made great preparations for defence … when Earl Harald came to Hjaltland, he laid siege to the Broch and cut off all communication, but it was difficult to take by assault.

It would have been; it was a massively built defensive tower. This is one of the largest brochs, standing 44 feet (13m) high, and it is the only one that stands to its full original height. It also has one of the thickest wall-bases, and consequently one of the smallest interiors. Its excellent state of preservation is due partly to its unusually massive construction and partly to its remote location. Because the building is a drystone construction, it would be easy to damage and disrupt.

Access is by a single door at ground level. Inside, it is possible to climb a staircase built into the thickness of the wall to reach an open walkway at the top.

In its first phase, the broch was a complex wooden roundhouse, with an upper floor resting on a ledge 7 feet (2.1m) above the ground. A second upper floor or perhaps the roof was supported on a second ledge 13 feet (4m) above the ground. A water tank was cut into the bedrock.

The wooden roundhouse was later demolished and a small wheelhouse was erected in the interior.

The Norse occupations that feature in the Orkneyinga Saga are reflected in certain features. The early low lintels of the entrance were pulled out and the outer doorway was doubled in height, which implies that the interior and the doorway were so full of debris that the Norsemen had to take out the door lintel and raise the passage roof simply in order to gain access. Today the door has been restored to its original low height.

See People: Taliesin.

See People: Iceni.

A British Dark Age kingdom in the lower Severn Valley, between Dumnonia to the south and Powys to the north. There were two towns in it: Cirencester and Gloucester.

See People: Arthur.

See People: Arthur.

See Camulodunum.

The Roman city of Colchester was developed on the site of an existing British oppidum, Camulodunum (or Camulodunon), which was the capital of the Catuvellauni tribe. Earlier, the settlement had been the main center of the Trinovantes tribe.

In the first century BC, the Trinovantes were taken over by the more powerful Catuvellauni tribe, who lived immediately to the west, and the Catuvellaunian kings moved their headquarters from Wheathampstead near St. Albans to Camulodunum. The reason may have been strategic. Camoludunum was only 4 miles (6km) from the head of the Colne estuary and defended to north and south by marshy river floodplains and forests; it was artificially defended on its western side by an elaborate system of defensive dykes built in the first century BC and first century AD. The location near to an estuary also meant that it was possible to escape by sea if it looked as though that would be necessary.

At the climax of the second Roman invasion, in AD 43, the emperor Claudius led his army in triumph into Camulodunum, which was then the stronghold of the late British king Cunobelin and the capital of the most powerful British kingdom. This symbolic act marked the Roman conquest of Britain.

It has recently been suggested that in the first century BC Julius Caesar also marched on Camulodunum, in hot pursuit of Cassivellaunus. Caesar’s description has usually been taken to refer to Wheathampstead, but it is now thought more likely to be Camulodunum:

He [Caesar] learnt that the stronghold of Cassivellaunus, defended by woods and marshes, lay not far away, and that he [Cassivellaunus] had gathered there a great number of men and cattle. Now, ‘stronghold’ is what the Britons call a thickly wooded area fortified by a rampart and ditch, and it is their practice to gather together in such a place to avoid enemy raids. Caesar set out for this place with the legions. He found that it was extremely well fortified by both natural and man-made defences; nevertheless he launched an assault on two sides. For a short time the enemy remained there, but they could not resist the assault of our troops and made their escape from another side of the stronghold. A great many cattle were found there, and many of the people who fled were captured and killed.

Given that Caesar had taken five legions with him—more than 20,000 men—the implication is that the stronghold was very big: only Camulodunum seems to fit Caesar’s account (see Lexden Tumulus).

See Myths: The Legend of Ys, The Salty Sea, The Sigh of Gwyddno Garanhir.

See People: Fogou.

In the area around the town of Carnac, there is an incredible concentration of ancient standing stones, stone circles, stone rows, and chambered tombs, dating from 3500 BC to 2500 BC. A 15 mile (24km) stretch of the Breton coast is known as “The Coast of the Megaliths.”

The most spectacular monuments, now and in antiquity, must be the rows of standing stones. There are three sets of them: Menec, Kermario, and Kerlescan. Kermario has 999 standing stones, while Menec has 1,099 standing stones arranged in 12 rows. The Kerlescan group consists of 55 surviving stones arranged in 13 rows. They lead to stone enclosures that were set up in 3500 BC but the rows themselves were built later, in 3000–2500 BC.

Like Stonehenge in Britain, Carnac has been an integral part of the Celtic cultural consciousness all the way through: a deeply embedded element of the psychological and spiritual landscape of Celtic Brittany. It has often been remarked that the endless rows of standing stones look like a religious procession or a petrified army, and it must have seemed so to many generations of Bretons too. No doubt, hundreds of years ago people imagined the stones to be not just monuments built by their ancestors, but actually their ancestors themselves, turned into stone.

See Religion: Coventina; Symbols: Horse.

See Symbols: Knot.

An Iron Age Celtic fortified settlement on a rocky island connected to the mainland by a tombolo (sandy beach) that makes a natural causeway. The site was discovered in 1933. Since then it has been excavated and the impressive ruins are accessible to the public from the C550 coastal highway south of the fishing village of Porto do Son, though there is a difficult and dangerous one-mile walk over rocks to reach them.

The castro is surrounded by perfect natural defenses—the rocky cliffs and Atlantic breakers on three sides, and a difficult clamber over rocks on the landward side. The sand tombolo is really the only point of access.

The settlement was built and inhabited 2,000 years ago. It has a defensive wall, which turns the site into a miniature hillfort. Inside, the enclosure is filled to a high density with stoutly built roundhouses with thick, stone walls. With a high degree of exposure to strong winds and sea spray, it cannot have been an easy place to live (see also People: Dwellings, Fortifications).

A forest in the north of Britain, probably in the Southern Uplands of Scotland. Medieval Scottish tradition puts it north of Stirling, extending into the Grampians. It was the wood where the bard Myrddin took refuge when he lost his mind after the Battle of Arderydd in about 573.

By the Middle Ages, the Wood of Celidon had acquired a sort of mythic Otherworldly status, like the Mirkwood of Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings.

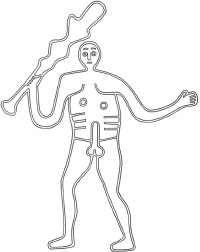

The Cerne Giant is a chalk hill figure: a huge line drawing made by cutting out a turf outline and filling the trench back up to ground level with white chalk rubble. He is 180 feet (55m) high from head to toe and in his right hand he waves a knobbly club 120 feet (37m) long. He is famously naked and even more famously displays an erect phallus 23 feet (7m) long. He looks vaguely menacing and warlike.

The current fashion is to present the Cerne Giant as a seventeenth-century cartoon. This idea hinges on some rather weak arguments; the main one is the fact that the Giant was not mentioned before 1694. But too much is made of the absence of evidence: we know that documents perish with the passage of time and in any case a lot of things happened in the past that were never written down. There are many arguments in favor of an ancient, Iron Age, origin. One is that it would be an extraordinary coincidence for a seventeenth-century cartoon to imitate so perfectly and in so many details a work of art from the Iron Age. There is no other image that looks exactly like the Cerne Giant, but all of his features can be found—in different combinations—in British and European artwork from 500 BC to AD 100.

The Giant is a naked warrior; the way some Celtic tribesmen took their clothes off before going into battle was an oddity that was commented on by the Romans (see Symbols: Nudity). Even more telling is the erection. Genital display is common in Iron Age art, where it may have one of two meanings: to ward off evil (and frighten enemies) and to bring good luck.

A virtually unnoticed feature of the Giant is that he is wearing a girdle. Diodorus Siculus described the Celts as “descending to do battle unclothed except for a girdle.” This belt was for holding a knife, for dispatching enemies and decapitating them.

The club suggests a common man who could not afford a sword. The cloak-shield also suggests poverty. First-century BC bronze figurines show naked warriors with cloaks wound around their left arms as primitive shields—the routine equipment of non-professional soldiers.

The resistivity surveys that I undertook in the 1990s showed that there was originally a cloak draped over the left arm.

A close contour survey of the low knoll below the left hand (undertaken by the National Trust) revealed the delicately modeled features of a human head in low-relief on the hillside. The Giant was swinging a severed human head from his left hand. The cult of the severed head is well documented. Headhunting was an integral part of warfare. The Giant was returning home from battle with the head of an important enemy—the service an Iron Age tribe would expect of its protector god.

The fact there may be no early documents that mentioned the Cerne Giant is not a problem. Values change through time, and before the time of John Aubrey antiquities were rarely mentioned in Britain. In 1649 Aubrey visited Avebury by chance while hunting, and described “the vast stones of which I had not heard before,” but we know from radiocarbon dates that they were there by 2500 BC.

The Early Modern hypothesis leans heavily on there being no documentation earlier than 1694. But there are some earlier documented mentions, in the Middle Ages. Accounts by William of Malmesbury and Walter of Coventry are well known, but an even earlier account by Goscelin in the eleventh century is rarely mentioned. In that, St. Augustine comes into conflict with a pagan community worshipping a low-relief pagan image at Cerne; he takes control by taking the site over and colonizing it.

Goscelin was a Norman monk who was in Dorset from 1055 to 1078 and later went to Canterbury, where he wrote various saints’ lives. His final work was a Life of St. Augustine. He was able to incorporate what he had picked up in Dorset about Augustine’s humiliating encounter with pagans at Cerne.

The importance of Goscelin’s text has been overlooked because a passage describes Augustine as “throwing over the idol to Helia,” and this could not refer to the Cerne Giant because it seems to describe toppling a statue, just as in more recent times people have pulled over statues of Lenin, Stalin, and Saddam Hussein. But the passage has been mistranslated for the last 400 years. It should read “Augustine took possession of the bas-relief of Hellia” and that certainly could be the Cerne Giant.

Taking possession of the hill-figure might well involve setting up a permanent mission close beside it, conforming to the tradition of an early Christian settlement on the abbey site. The Life of St. Augustine reports that he saw offensive images that he felt should be destroyed. We know he sought advice from his superior, the Pope, because Pope Gregory’s reply has survived: “Upon mature deliberation the temples of the idols ought not to be destroyed.” Gregory explained that he wanted the missionaries to take them over gradually, occupying the pagan sanctuaries and converting them to Christian worship. The Christian missionaries in time did that at Cerne Abbas, eventually building an abbey church between the Giant and a Celtic pagan sacred spring.

Taking over and Christianizing existing sanctuaries and temples was an officially approved and recommended practice. In AD 601 Gregory the Great sent an explicit letter of advice to the missionaries in England, specifically to Mellitus:

When (by God’s help) you come to our most reverend brother, Bishop Augustine, I want you to tell him how earnestly I have been pondering over the affairs of the English; I have come to the conclusion that the temples of the idols in England should not on any account be destroyed. The temples should be sprinkled with holy water and altars set up in them in which relics are to be enclosed. If these temples in Britain are well-built, then it is better to convert them from the worship of devils to the service of the true God: that the people, seeing that their temples are not destroyed, may remove error from their hearts and adoring the true God may the more freely resort to places to which they have been accustomed.

This is exactly what St. Augustine did at Cerne Abbas, turning a pagan site into a Christian site.

So, a careful look at the medieval texts reveals that there are after all references to the Giant traceable right back to the eleventh century. There was even continuity in his name. Goscelin called him Helia and later writers called him Hele, Helis, and Helith.

When the great pioneering antiquarian William Stukeley visited Cerne Abbas in 1761, the locals told him who the Giant was, but they were uneducated country folk and he was dismissive. “The inhabitants pretend to know nothing more of it than a traditionary account of its being a deity of the ancient Britons,” Stukeley laughed up his sleeve, but the thrust of the evidence is that the villagers were right. The Cerne Giant was, and still is, Helis, a tribal guardian god of the ancient Britons.

He was drawn on the hillside perhaps in 100 BC and the Celtic Sanctuary of Helis-Toutatis stood on the site later occupied by Cerne Abbey. The earthworks that were landscaped into formal gardens for the abbey were originally made in the Iron Age: Roman coins have been found in the earthworks, showing that they were there long before the medieval abbey.

Cerne Abbas is a site that has been much misunderstood, like the Celts themselves. The evidence does point to it being a major Celtic rural sanctuary. It was more or less in the geometric center of the territory of the Durotriges tribe, which corresponds closely with modern Dorset. Cerne Abbas is more or less exactly midway between the three major hillforts of the Durotriges: Hod Hill, South Cadbury Castle, and Maiden Castle. The Durotriges were a loose confederation of tribes and may well have met from time to time at their shared sanctuary, close to the spot where their boundaries met.

The Mars gods of the English West Country were war leaders, protectors of their tribes, but they also were spirits of well-being and prosperity. Even if the warlike attributes were to the fore, there were peaceful and benign attributes as well, including healing. Close to the foot of the hill at Cerne Abbas was a healing spring, St. Augustine’s Well, which is likely to have been involved in the Giant’s cult (see Symbols: Water).

In the Cotswolds, the Mars god appears as a benign god of rustic well-being. At King’s Stanley in Gloucestershire, he is shown in the full armor of a Roman soldier, for the benefit of Roman legionaries no doubt, but it is very unlikely that the local Celtic tribespeople, the Dobunni, would have seen him like this. For a start, they would have seen him naked; in fact more like the Cerne Giant.

There is a striking similarity between the Cerne Giant image and a depiction of Ogmios, the Celtic Hercules, carved in stone at High Rochester in Northumberland. This Romano-Celtic image shows a powerfully muscled naked man with a knobbed club in his right hand and a cloak wrapped round his left arm as an improvised shield.

See Religion: Druids.

See People: Cogidumnus.

See People: Dwellings.

See Calchvynnydd; Religion: Hooded Dwarves, Mother Goddess; Symbols: Sky Horseman.

See Camulodunum, Lexden Tumulus.

This remarkable shrine to the mother goddess, unusually named here as Nehalennia, stood on the East Scheldt estuary. It was discovered in 1970, when fishermen pulled up stone altars from a depth of 85 feet (26m). Since that moment of discovery, more than 120 altars and pieces of sculpture have been recovered from under the water. It seems that this shrine was in use, standing on the riverbank, in AD 200, and later subsided into the sea.

Nehalennia was a Celtic goddess invoked by Romanized Gauls and Romans. Seafarers and traders were important worshipers at this particular waterfront shrine, dedicating altars to her, grateful for safe voyages and profitable trade deals. The images dedicated to her are standardized. She is shown sitting with baskets of fruit and horns of plenty (see Symbols: Cornucopia). She is also usually accompanied by a dog.

See Religion: Holy Well.

See Religion: Cernunnos.

One of the most professionally excavated Celtic sites, this hillfort stands 30 miles (48km) from the sea in the kingdom of the Atrebates tribe. It was in use for 500 years until it was destroyed by fire in around 100 BC. Danebury was strongly fortified permanent settlement, with internal streets laid out according to a regular plan, lined by roundhouses (see Fortifications). About 300–500 people lived there. Its modern name, “Fort of the Danes,” misleads, as it was really “Fort of the Britons.”

The temples were located at the highest part of the oppidum. The road leading westward from the main east entrance took the visitor directly to the shrines on the hilltop. They consisted of three square structures and an enclosure, all in a straight line. The shrines were built of vertical planks set in slots cut into the chalk.

See Religion: Ritual Shaft.

See Dyfed.

Din Eidyn is now Edinburgh’s Castle Rock. It was the principal stronghold of the Gododdin: the Dark Age kingdom that occupied the eastern half of the Scottish Lowlands and much of the Southern Uplands. The people of this kingdom were called the Votadini by Ptolemy in the second century, but the name had been transmuted into Gododdin by the sixth century, when they were immortalized in the heroic poem, written around 600, which refers for the first time to Din Eidyn, ancient Edinburgh (see People: The Gododdin).

Dinas Emrys, “Fort of Ambrosius,” is a place associated with a legend—the confrontation between Vortigern and Ambrosius Aurelianus is said to have taken place here. But in spite of the name and the legend, it is hard to believe that Ambrosius had any connection with the place. Nennius seems to be referring to this Ambrosius when he uses the title Gwledg Emrys—gwledig means “prince” in Welsh and Emrys is the Welsh form of Ambrosius—but although this might seem to associate Ambrosius with Wales, and therefore conceivably with Dinas Emrys, the Britons living in the West Country, the Severn Valley, the Midlands, and the north of England also spoke a language very close to Old Welsh. The fact that the form Emrys survives now only in Wales does not mean that someone called Emrys in the sixth century was Welsh.

The principal fortress of the South Wales kingdom of Glevissig. An eleventh-century castle was built on the ruins of a sixth and seventh-century fortress. It was a compact but well-defended homestead inhabited by a powerful chief and his immediate family. It contrasts with the much larger Iron Age hillforts of southern Britain, which were designed to house a whole clan or tribe.

A lake on Bodmin Moor in Cornwall. This is the lake from which Arthur is said to have taken the sword Excalibur and to which the sword was eventually returned after his death.

A Dark Age kingdom consisting of what is now Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, and Dorset. It was named after the Iron Age people who lived there long before the Romans arrived: the Dumnonii.

An Iron Age castle built on the high cliffs of Innie Mór, the biggest of the Aran islands in Galway Bay. The fortress was first occupied in the late Bronze Age and it was reused repeatedly until the first millennium AD. The first settlement would probably have had a single stone wall perimeter that was rebuilt and repeatedly modified. The present innermost fortification is a stone wall 16.5 feet (5m) wide and 16.5 feet (5m) high. It was rebuilt in the Iron Age, but may contain the original Bronze Age wall. The defenses consist of three concentric perimeter walls.

The fort is now semi-circular, because of cliff retreat; presumably when it was new it was circular. Outside the three walls is a chevaux-de-frise: a zone of angular stones embedded in the ground close together to make them an obstacle to attackers. They are very difficult to walk across. Chevaux-de-frises are found in Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and Galicia.

A fortress on a low rocky crag on the Crinan isthmus of the Kintyre peninsula in Argyll. It was fortified in the Iron Age, then reoccupied after the Romans left. When the Kintyre peninsula was colonized by Irish settlers in the fifth century and became part of the British kingdom of Dal Riada, the ruling dynasty made this little drystone-walled citadel its capital. It continued in use like this, as a royal stronghold, for 300 years.

Imported Mediterranean pottery proves Dunadd’s high status in the Dark Ages. The survival of the ancient name Dunatt from the contemporary Irish Annals almost unchanged right down to the present day makes it absolutely certain that this is the place referred to in the Dark Age documents (see also Tintagel).

See Traprain Law.

See Maiden Castle.

A Dark Age Celtic kingdom that was also known as Demetia after the Iron Age tribe who lived there: the Demetae. It later became the county of Pembrokeshire.

See Maiden Castle.

A Dark Age Celtic kingdom consisting of the Pennines. In the middle of the sixth century, Pabo Post Prydain, “Pabo the Pillar of Britain,” was king of the Pennines. When he abdicated, the Pennine kingdom was divided between his sons Dunawt (Donatus), who ruled in the north, and Sawyl Benasgell (Samuel), who ruled in the south.

These small units had probably seen an earlier history as tribal territories. What happened during the Iron Age, sub-Roman, and post-Roman periods was a cyclical process of aggregation and disaggregation, and integration and devolution. Elmet was the southernmost of a chain of Brigantian territories that re-emerged after the Romans left. It was probably a return to a much older, perhaps middle, Iron Age territory. But by 550 this splintering process was weakening the Celtic fringe and making it easier for Saxon colonization to resume.

A round enclosure of 15 acres (6 hectares), on a prominent drumlin ridge just a mile (1.6km) west of the city of Armagh. It is known today as Navan Fort. It was, according to historical tradition and Irish mythology, the legendary capital of the Ulaidh: the tribe who gave their name to the province of Ulster.

The large, circular enclosure is 820 feet (250m) in diameter and surrounded by a ditch and a bank. Significantly, the ditch is inside the bank, which shows that the earthworks were not defensive but had a ritual function. This is the same layout that is seen in the Neolithic henges of western Britain, and it may be helpful to regard Emain Macha as a very large (but very late) henge, with correspondingly high status. The reference back to ancient practice is significant; ceremonies often include extremely archaic elements.

Inside the large enclosure, off-center to the north-west, is an earthen mound 130 feet (40m) in diameter and 20 feet (6m) high. To the south-east is a plowed-down ring-shaped monument about 100 feet (30m) in diameter.

The large mound covers the site of a roundhouse that was standing from about 350 BC to the late second century AD and was rebuilt nine times. After the final roundhouse, a new structure was laid out, a huge array of concentric posts 130 feet (40m) in diameter, with an entrance toward the west. The final act in the building of this monument was the raising of an enormous post 43 feet (13m) tall at the center. This happened in 94 BC. Then, in what seem to have been ritual deposition ceremonies, a cairn of stone, clay, and turf was built up around the internal posts, producing a huge mound. The outside timbers were deliberately set on fire and the building as a whole was covered in a turf mound, making something that looked like a Neolithic passage grave. The surrounding bank and ditch were created at the same time.

The whole sequence of events and the architecture of the Emain Macha monument smack of Neolithic rituals from a much earlier time, around 3000 BC, including the deliberate destruction by fire. It is long-held traditions and continuities of this kind that make the idea of a very long-established Atlantic Celtic community seem plausible.

Archeology shows that the hill was in use in the Neolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age.

The low ring-shaped monument was a round timber building that was rebuilt twice over. The remains of similar but smaller buildings with hearths were found under the 130-foot (40m) mound; they were large circular dwellings inhabited 600–250 BC, and it is tempting to see them as royal palaces. In the debris from these Iron Age dwellings was the skull of a macaque, perhaps the pet monkey of an ancient Irish king.

The Annals of the Four Masters say that Emain Macha was abandoned after being burned down in AD 331. The ancient place was destroyed by the Three Collas after a battle in which they defeated Fergus Foga, King of Ulster.

In Irish legend, especially in tales of the Ulster Cycle, this is one of the most important power centers in pagan Ireland. The ancient capital of Ulster was founded by the goddess Macha, perhaps in the seventh century BC, and it became the seat of Conchobar mac Nessa. He had three houses at Emain Macha. One was the Cróeb Ruad (pronounced creeve-roe), meaning “The Ruddy Branch,” which is where he had his residence; the name “Creeveroe” survives still as a local place-name. Another was the Cróeb Derg, “The Red Branch,” where the king’s battle trophies were kept. The third was the Téte Brecc, “The Twinkling Hoard,” where the war-band’s weapons were kept.

Many names celebrated in Irish mythology are connected directly with Emain Macha and the Red Branch warriors: Amergin the poet, Cú Chulainn the warrior, Emer his strong-willed bride, Conall Cernach his friend, Cathbad the chief Druid, Conchobar mac Nessa, the King of Ulster, and Deirdre of the Sorrows, the most beautiful woman in Ireland.

Today there is little to see beyond a grassy mound; a great contrast to the Emain Macha of myth and legend, which is a grand and mysterious place, the capital of the Ulaidh. The archeology shows a site that was relatively simple and primitive, but with ceremonies rooted in a distant past. The name “fort” is misleading, as the place was laid out for pagan ceremonies.

Navan was threatened by the expansion of a limestone quarry in the 1980s. A Friends of Navan group was formed and a public inquiry led to quarrying being stopped; the site was to be developed for tourism. A visitor center was opened in 1991, closed in 1993 through shortage of funds then reopened on a seasonal basis in 2005. The Celtic heritage is vulnerable, and not to be taken for granted.

Entremont was the capital of the Saluvii tribe. It was sacked by the Romans in 123 BC.

The famous sanctuary at Entremont was placed on the highest point in the area. It was built in the third to second century BC and fitted with limestone pillars 8.5 feet (2.6m) high with incised carvings of human heads. There were other sculptures too, mostly connected with severed heads (see Religion: Headhunting).

See Religion: Shrines and Temples.

See Symbols: Water.

See Glevissig.

The Celtic site is not, as might have been expected, the great ruined abbey with all its legendary associations, but an unpromising marshland location nearby where an Iron Age lake village was discovered by Arthur Bulleid in 1892. The lakeside village consisted of more than 90 huts, of which perhaps 30 were occupied at any one time. The round huts were built of closely set upright timbers, with the gaps closed by hurdles. The floors were clay, with central hearths also made of clay. The village stood on a shelf of peat and was surrounded by a wooden palisade. It was in use from 250 BC to 50 BC.

The waterlogged conditions at the site meant that wooden objects that have been lost elsewhere were well-preserved here: ladles, wheel spokes and hubs, tool handles, a ladder, and a loom.

An important Celtic oppidum. It consists of a fortified settlement and several burial mounds. It was the seat of power of tribal chiefs in the late Hallstatt and early La Tène periods (see People: Cultures). In the 1990s it yielded major new evidence about burial, sculpture, and monuments.

The site stands on a spur of the Vogelsberg range, rising 490 feet (150m) above the surrounding fertile landscape. The hilltop, surrounded by springs, is very level and about 2,600 feet (800m) across, with a steep drop on all sides.

It had been known for a long time that there were ruins on the Glauberg plateau, but it was assumed they belonged to the Romans. The chance find of a La Tène torc in 1906 pointed to a more ancient ancestry for the site. Work in the 1930s had a focus on the fortifications. In the 1980s and 1990s the burial mound was investigated. Studies in 2004–6 looked at the settlement history and revealed much about the Hallstatt and La Tène periods, though people had been living there since the Neolithic (4500–4000 BC), and it is possible the Glauberg may have been fortified even at that early stage. The hill was also occupied in the Bronze Age by the Urnfield people (1,000–800 BC). By the middle Iron Age, the Glauberg was the seat of an early Celtic prince, who ordered the building of extensive fortifications.

In the Roman occupation, the Glauberg was unoccupied. The Romans may have emptied it because of its proximity to their fortified border, Limes Germanicus. The hill was refortified by the Franks in the seventh to ninth centuries. The Celtic fortifications were developed on a large scale in the sixth or fifth century BC and remained in use for 400 years. They define the Glauberg as one of the network of oppida existing across most of southern Germany.

The fortified town had at least two gates. There were also additional defenses farther out, to the north-east and south-west. This was a large settlement.

To the south were two royal burial mounds. The larger was originally 160 feet (50m) in diameter and 20 feet (6m) high, surrounded by a ditch 33 feet (10m) wide. At its center was an empty pit, evidently to fool looters, while the real burial chamber was to the north-west. This was a small wooden burial chamber containing a burial; there was a cremation burial as well, which is more characteristic of Hallstatt. Both were the graves of warriors, to judge from their grave goods. The burial chamber was removed to a lab intact in order to excavate it more slowly. Each of the finds in the main chamber had been carefully wrapped in cloth, including a fine gold torc and a bronze jug that had once contained mead. A processional way 1,100 feet (335m) long approached the mound from the south-east.

A second mound, 800 feet (250m) to the south, was invisible on the ground, as it had been plowed flat. This was a smaller mound than the first, but contained a warrior with a gold ring.

A cluster of 16 postholes was associated with the mound; this structure was a simple astronomical calendar, probably to determine the dates of important seasonal festivals.

The mounds and the processional way were unusual enough, but the find of a life-size pink sandstone statue was very rare. This dated from around 500 BC and was found close to the larger burial mound. Made of local stone, it depicts an armed warrior in great detail: his trousers, armored tunic, wooden shield, and typical La Tène sword. On his head he wears a strange hoodlike headdress crowned by two extensions, perhaps intended to look like a mistletoe leaf. Unfortunately, to a modern visitor they look like the ears of Mickey Mouse. But this was no whimsy on the part of the sculptor: this type of headdress is known from a couple of other statues of the period.

Fragments of three similar statues were found in the area and it is possible that originally all four statues once stood together in the rectangular enclosure.

Remarkable though this site appears to be, the same sort of thing was happening at other Celtic sites in central Europe. There are three other sites of the La Tène period—Holzgerlingen, Pfalzfeld, and Hirschlanden—where similar large warrior statues were erected.

A Dark Age kingdom corresponding to today’s Glamorgan.

See Calchvynnydd.

See Glevissig.

See Religion: Shrines and Temples.

See Religion: Shrines and Temples.

A major sanctuary at Gournay-sur-Aronde, close to the north-eastern corner of the land of the Bellovaci and within easy reach of the Ambiani, Viromandui, and Suessiones tribes. The sanctuary was probably used as a meeting-place for the four tribes.

The square enclosure bounded by a ditch had its entrance on the south. It was in use from the fourth century BC to the fourth century AD. It was laid out inside but near the edge of an oppidum. The sanctuary was perched on a valley slope 175 feet (53m) from a stream, which here widened into a lake about 4 acres (1.6 hectares) in extent. Possibly some of the cult activity at the sanctuary was related to the lake, or the sanctuary was built to commemorate the very early settlement that stood close by in the Bronze Age.

Many animal and human sacrifices were carried out, probably in the oppidum, though not in the sanctuary. Selected parts of the slaughtered animals were taken to the rectangular sacred enclosure and deposited in its surrounding ditch. The remains of sheep and pigs were deposited in the middle section of each side, cattle skulls on either side of the entrance, horse skeletons at intervals right around, and human remains at the corners. The distribution of the sacrifices was orderly and methodical.

In the middle of the sacred enclosure an array of nine pits surrounded a large central pit. At the end of the sanctuary’s life, a small Romano-Celtic temple was built right in the center: a rectangular roofed building surrounded by a roofed verandah. There was exactly the same sequence of events at the sanctuary at Vendeuil-Caply.

A Dark Age kingdom in north-west Wales corresponding approximately to the modern county of Gwynedd.

See People: Cultures.

See Maiden Castle.

See Symbols: Sky Horseman.

A Celtic ritual enclosure 260 feet (80m) square. The entrance halfway along its eastern side led the visitor directly to the doorway of a large, circular temple. Offerings deposited here included chariots, horses, scabbards, and swords.

In AD 50 a small stone Romano-Celtic temple was built on the same spot and it looks as though the religious cult activity continued as before (see Religion: Shrines and Temples).

This headland at the mouth of the Wiltshire Avon commanded Christchurch Harbor. In the first century BC this was a major port. The fortified Iron Age settlement stood on the peninsula jutting eastward and forming the southern side of the harbor (see Fortifications). This peninsula was separated from the mainland by a defensive bank and ditch. A substantial settlement of roundhouses was built on the more sheltered northern slope of the peninsula, overlooking the large harbor (see People: Dwellings).

The ancient name of this important port is not known, but it has been established that it had strong trading links with ports in Brittany. Breton pottery was imported and a lot of Breton coins have been found in the area. Imported wine jars (amphorae) that came directly from Italy have been found in a scatter up to 20 miles (32km) from Hengistbury. One of the wine ships sank off the Breton coast; its cargo of wine remains undrunk on the seabed.

Both Strabo and Julius Caesar commented that there was a lot of cross-Channel trade, and Hengistbury supplies proof of it. The Veneti in Brittany in particular ran a fleet of merchant vessels. Caesar disrupted this trade when he defeated the tribe in 56 BC; they had opposed him. The Dorset tribe, the Durotriges, were equally opposed to the Roman conquest 100 years later.

A fortified settlement on a hill above the Danube (see Fortifications). It was a very important early Iron Age center in the seventh, sixth, and fifth centuries BC, on the site of an earlier Bronze Age settlement that flourished in the fifteenth to twelfth centuries BC, though it was abandoned in between. This was the key center of power and trade in south Germany in the Iron Age.

A remarkable feature of the settlement was the citadel’s circuit wall, built in 600 BC. It was a mudbrick wall 13 feet (4m) high, probably with a roofed walkway on top. Rectangular towers projected from it at intervals. It was destroyed by fire in 530 BC.

Associated with the Heuneberg is the Höhmichele Barrow, an important grave mound built in the sixth century BC. Inside were two wooden chambers. One contained the body of a woman with a wagon. The other contained the body of a man with a wagon and harness, laid on a bull’s hide with a woman beside him. The man had with him the grave goods of a warrior-prince: two bows, a quiver, and 50 iron-tipped arrows. What was most surprising about this grave was its opulence. There were bronze vessels and jewelry and rich textiles in the shape of clothing and wall-drapes, which incorporated Chinese silk. It was an exceptionally rich tomb and it challenges classically influenced ideas of a barbaric Iron Age Europe.

The finds at the Heuneberg show that the people here carried on a prosperous trade with the Greeks of Massilia (Marseille).

Another Celtic tomb dating from about 600 BC has been found not far from the Heuneberg. It is unusually well preserved and contains elaborate jewelry of amber and gold. The tomb consists of an underground chamber 16 feet (5m) by 13 feet (4m). Its oak floor is intact and well preserved. The finds suggest that a woman was buried there. The entire burial chamber was lifted by cranes onto a flatbed truck and taken to a lab at Ludwigsburg. Other tombs at Heuneberg have been found, but usually they have been looted; this one was not.

A late Hallstatt burial mound north-west of Stuttgart. A remarkable life-sized stone statue was found here, probably originally standing on the summit of the tumulus. Pre-Roman Celtic stone statuary is rare. It seems that in later antiquity the Celts were ready to copy Roman statues, but this one is too early for that to be the explanation: it seems to be the product of a purely native Celtic inspiration. It was carved in sandstone and erected on the mound at the end of the sixth century BC. It depicts a warrior wearing a helmet, torc, belt, and dagger, but otherwise naked (see Pfalzfeld).

The country home and resting-place of an Iron Age prince who lived around 525–425 BC (late Hallstatt or early La Tène period). His principal seat of power was at Hohenasperg, nearby. The three sites—the seat of power, the country residence, and the grave—are all within 10 miles (16km) of Stuttgart on a tributary of the Neckar River.

The country home, locally known as Hochdorf Reps, consisted of some very big houses, up to 1,507 square feet (459 square meters), underground huts up to 25 feet (8m) long, and storage pits. All of these were surrounded by a rectangular fence. The main residence was a large, bow-sided house. Local wheel-turned pottery dominated the pottery assemblage, but some fragments of Greek kylices were found, dating to around 425 BC.

The storage pits were for storing barley, spelt wheat, and millet. Six rectangular trench granaries were identified at the residential site; at least two of them are thought to be associated with the production of barley beer.

The wagon grave at Hochdorf is one of around 100 wagon graves known from 550–500 BC in France, Switzerland, and Germany. It is a huge barrow, 200 feet (60m) in diameter and 20 feet (6m) high when first constructed. The entrance to the mound was to the north. The mound was surrounded by a ring of stones and oak posts. Inside the barrow was a central chamber, 15 feet (4.6m) square, made of oak beams. Laid out on a platform inside was a man’s skeleton, with a large, bronze cauldron filled with honey mead at his feet.

Also in the chamber was a large four-wheeled wagon with harness for two horses. Inside the wagon was a dinner service of three serving bowls and nine bronze dishes and plates. Along the walls were nine 9-pint (5-liter) drinking horns, eight made from aurochs’ horns and one of iron inlaid with strips of gold. The dead king—he must have been a king—was expecting to entertain eight other people when he reached the Otherworld. The chamber was decorated with wall hangings and carpets. There were two further square chambers: one 24 feet (7.3m) across and the other 36 feet (11m) across.

Over the chamber roof was a layer of 50 tons (45 tonnes) of stones, and it may be that it was this layer that prevented the grave-robbers from looting the tomb.

The man in the Hochdorf grave was 40 years old and unusually tall for the period: 6 feet, 1 inch (1.85m). He wore a flat cone-shaped hat (a coolie hat) made of birch bark, decorated with circles and punched decoration. His body was swathed in colored fabric. He wore a golden necklace and golden shoes. Beside him were his toilet requisites: a comb and a razor. There were also items of hunting equipment: a small iron knife, a quiver of arrows, and a bag containing three fish-hooks.

The big, bronze cauldron, probably Greek-made, was decorated with three lions on the rim and three handles with roll attachments. It would have held up to 109 gallons (500 liters) of honey mead; traces of mead were found inside. On top of it was a small, golden cup.

The bronze hearse on which the king was resting is supported by eight female figurines cast in bronze. They are standing on wheels, so that the hearse could be rolled.

Only a highly civilized culture could have produced a kingly burial such as this.

See Maiden Castle.

A steep-sided, flat-topped mountain rising abruptly 300 feet (90m) above the surrounding hill country and above the town of Asperg. The Hohenasperg naturally lends itself to fortification and it has been the site of a fortress through many different periods of history. It is clearly visible from a long way off.

In 500 BC, the Hohenasperg was a fortress-refuge and a cult focus for the local Alamanni tribe. There are many Iron Age cemeteries in the area, and they have been located in a way that offers a line of sight to the Hohenasperg. The grave site on the Katharinenlinde near Schwieberdingen is one of these; the great chieftain’s grave at Hochdorf is another. The Kleinaspergle is a burial mound that lies about half a mile (0.8km) to the south of the Hohenasperg; this offers an exceptionally good close-up view of the Hohenasperg.

The area was overrun by the Franks in about AD 500. After that the Hohenasperg was occupied by the Frankish lord and his legislative assembly. Under the Franks, the mountain was called Ascicberg: the origin of the modern name of the place, Asperg.

See The Heuneberg.

A La Tène ritual enclosure here contained three ritual shafts. One of them was 26 feet (8m) deep with a wooden stake placed at the bottom. This post was surrounded by traces of blood and flesh. The implication is that animals or people were thrown down the shaft as sacrificial offerings. This echoes an almost identical practice at Swanwick in England several centuries earlier, in 1000 BC, which implies a very widespread and persistent sacrificial practice (see Religion: Human Sacrifice).

The Dark Age Irish name for the English Channel.

The island of Ictis, mentioned by Diodorus, was St. Michael’s Mount in Cornwall.

An early stone-built coastal settlement that was inhabited intermittently for a very long time, Jarlshof seems to typify the complex history of the Atlantic Celts. It began in 2000 BC as a late Neolithic village and was reoccupied in the Bronze Age, Iron Age, and later by the Vikings. It was engulfed by sand during a storm, and it was the sand that preserved the remains until modern times.

See Symbols: Labyrinth.

See Traprain Law.

See Carnac.

See Myths: The Ballad of Bran.

See Carnac.

See Religion: Brighid.

See Hohenasperg.

An important archeological site at the eastern end of Lake Neuchatel. The name La Tène means “The Shallows” and it was in the shallow water along the lakeshore that evidence of a distinctive middle Iron Age culture came to light. The place has given its name to the La Tène culture, which lasted from 450 BC until 50 BC.

The site, near the village of Marin-Epagnier, includes a sanctuary, a walkway, and two bridges: the Pont Desor and the Pont Vouga; these were first discovered when the lake levels were lowered in the 1860s. The site includes features dating from both the Hallstatt and La Tène cultural periods of the Iron Age, from about 650 to 200 BC.

Two hundred feet (60m) out into the lake, scuba-divers have found the most complete remains of a Celtic ship, a 60-foot (18m) single-masted cargo ship. Its shadowy shape had been spotted by aerial photography. It is a reminder that La Tène lies on an important early trade route connecting Rhône and Rhine valleys.

La Tène was first discovered in 1857 and excavated in 1906–17, when it yielded a rich haul of objects that were of new types, including iron swords and everyday ironwork—even woodwork. Of the 3,000 or more objects recovered from the site, 60 percent are weapons or artifacts closely connected with weaponry (see People: Warfare). Other objects include iron tools, sickles, axes, tweezers, fishing gear, basketry, pottery, wooden bowls, and horse and cattle skulls—even chariot wheels.

The discoveries at the start of the twentieth century and the identification of the new culture sparked a new enthusiasm for archeology. The site does not seem to have been a settlement; it is likely that it was a ritual focus: a place where people came specifically to deposit offerings in the lake.

See Religion: Sacred Lake.

See La Tène; Religion: Sacred Lake.

See Religion: Sacred Lake; Symbols: Water.

A large royal burial mound in Colchester, dating from about 10 BC or a little later. When it was excavated in 1924 it was found to contain the 2,000-year-old burial of a king inside a substantial timber mortuary house. He was laid out on a bed, surrounded by an array of grave goods: shoes, clothes, jars, amphorae of wine, swords, shields, and spears. He may have been one of the Catuvellaunian kings, Addedomarus, Tasciovanus, or even his son Cunobelinus.

The royal burial discovered not long ago at Prittlewell near Southend was similar—in fact remarkably similar, considering that it dates from about AD 620. There is the same sort of timber mortuary house buried beneath a substantial barrow and accompanied by exotic items from as far afield as the Mediterranean. There is even the same sort of folding stool. At first sight, these two kings belong not merely to the same culture, but to the same dynasty—they might be brothers, and yet they are separated from each other by 600 years.

Addedomarus, the likely occupant of the Lexden Tumulus, was King of the Catuvellauni, while Saebert (who died in 616), the likely candidate for the Prittlewell Prince, was King of Essex. They are separated by what we have been conditioned to see as two major conquests—by the Romans and the Anglo-Saxons—and by culture changes, yet the evidence shows that there was a strong force for continuity embedded within Britain, and within the lands of the Atlantic Celts generally.

A third-century BC Celtic or Germanic ritual enclosure. It was laid out with a square plan, which suggests that it may have been a forerunner of the later Celtic rectangular enclosures.

The well-preserved body of a young, red-haired man with a ginger beard was found here in waterlogged peat. He had been in his early twenties in around 300 BC when he had been poleaxed, garroted, and had his throat cut. He had not just been killed, but killed three times over—the Celtic magic number—and this indicates a ritual killing (see Symbols: Rule of Three). Apart from a band of fox-fur around his left arm, he was naked, which also implies ritual.

Investigation revealed that his killers first hit him twice over the head with ax blows that stunned but did not kill him. Then they carefully tied a cord tightly around his neck, knotted it, and neatly cut off the cord ends from each side of the knot. Then they pushed a stick under the cord and twisted it like a tourniquet, garroting him until his neck broke. Then they cut his throat, opening his jugular vein. After the killing, the young man’s naked body was put face-down in a crouched position in the bog.

His condition is intriguing. He was well-built, 5 feet, 6 inches (1.68m) tall. He had a full head of hair, grown to medium length, and a short beard. He had well-manicured fingernails, showing that he was not a laborer. His moustache was neatly clipped. Archeologists think he was an aristocrat or a Druid. He had eaten a griddle cake shortly before his death. This was a carefully prepared, carefully executed killing, with the character of a sacrifice rather than a normal murder. Lindow Man is one of the most evocative examples of human sacrifice to have been found in Britain.

A poorly preserved human head was found in a peat bog in Lancashire in 1958. This has recently been re-examined by computer tomography, and its owner, Worsley Man, was murdered, executed, or sacrificed in the same way as Lindow Man. Worsley Man met his end between AD 70 and AD 400, in other words during the Roman occupation of Britain. It is a reminder that Celtic practices went on “under the Romans,” just as they had before.

Irish folk-tales often contain the motif of the Threefold Death, where a human being suffers three different deaths. In one legend, a king is wounded, the house inside which he is trapped burns down around him, and he finally drowns in a vat of liquor as he attempts to escape from the flames. What happened to Lindow Man is that a Threefold Death was planned and carried out deliberately, perhaps to make some prophecy come true.

See Symbols: Dragon.

See Religion: Brighid.

See People: Cadfan.

See People: Illtud.

See Religion: Sacred Lake.

See Religion: Sacred Lake.

See Symbols: Dragon.

There are several major ancient stone monuments here. The most spectacular is the Grand Menhir Brisé, “The Great Broken Standing Stone.” This lies on the ground, broken into five large pieces and apparently felled by a lightning strike in antiquity, though Aubrey Burl thinks it was broken before it could be raised. Dragging it to this spot from the quarry 3 miles (5km) away in about 1700 BC was in itself a huge undertaking. When (and if) standing intact, this 256 ton (232 tonne) monster would have stood at least 80 feet (24m) high.

There is also a fine Neolithic tomb nearby, the Table des Marchands, and another, the Dolmen des Pierres Plats, which is full of decorated stones.

See Myths: The Legend of Ys.

Nodens was a British healing god who, like Lenus, was equated by the Romans with their god Mars. He had an imposing sanctuary at Lydney in Gloucestershire, on high ground overlooking the Severn River. It comprised a substantial hostel, baths, and a long building that has been interpreted as an abaton: a dormitory for the pilgrims’ sacred curative sleep.

Lydney was a wealthy sanctuary, fitted with mosaics, and it was probably built fairly late, toward the end of the third century AD, and renovated a few decades later. The dedications are to Nodens on his own, or Nodens with Mars, or Nodens with Silvanus.

Nobody knows what Nodens looked like, because there are no surviving images of him. The cult objects include a number of dog figurines, and dogs are often associated with healing; their saliva is thought to heal wounds. Other objects include a votive offering of a model arm.

Some of the imagery at Lydney suggests a marine theme. There is a diadem showing the sun god driving a four-horse chariot with tritons and anchors; a relief shows a sea god. Maybe the sea connection at Lydney is the Severn bore, which might have been observed from there.

The association of Nodens with Silvanus is hard to explain. Silvanus was a hunting god, and dogs were used for hunting; perhaps it is the dogs that connect the two. But Lydney is a strange jumble of images and it may be unwise to look for too many connections.

Among other finds was a seated mother goddess carrying horns of plenty—a fertility image (see Cornucopia).

See Symbols: Dragon.

See Symbols: City Swallowed Up by the Sea.

See Religion: Lugh, Lughnasad.

A royal Celtic tomb near Villingen-Schwenningen in the Black Forest. A recent re-evaluation in Mainz of old excavation plans of the central royal tomb and the burials around it has led to a new discovery: the layout corresponds with the arrangement of the stars in the northern sky. The approach is similar to the proposition that the layout of the three pyramids at Gizeh represents the stars of Orion’s belt.

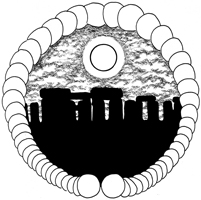

The burial mound at Magdalenenberg is more than 330 feet (100m) in diameter. The builders positioned long rows of wooden posts on the site of the mound in order to locate the lunar standstill, the northernmost position on the horizon where the moon rises. The standstill is reached every 18.6 years and it marks the completion of a lunar cycle. It is thought that it might have been a key landmark in the Celtic calendar. The northernmost moonrise was certainly of interest to the builders of Stonehenge. In about 3000 BC they put up a post each year on the entrance causeway to mark the northernmost position of the moonrise. After observing for more than a century, they had enough data to work out the cyclical pattern, be certain of it, and be confident about predicting it too.

The Magdalenenburg constellation map—if that is what it really is—suggests to Dr. Allard Mees a date of 618 BC. Julius Caesar commented about the Celts using a moon-based calendar (the Romans based their calendar on the sun). Now there seems to be a little archeological evidence for the Celtic emphasis on the moon.

A huge hillfort with soaring earth ramparts enclosing an area of 47 acres (19 hectares). Maiden Castle was the central place of the Durotriges tribe. The Durotriges were probably ruled by 10 or 20 petty chiefs, each commanding a pagus, or district. They used up a great deal of energy in internal disputes and power struggles, and possibly fending off raids by Atrebates or Catuvellauni tribesmen. Although they were resolute and bold, they were not organized to defend themselves against Rome. The easy progress of Vespasian’s conquering army through Wessex shows that in AD 43 Durotrigian power was decentralized and uncoordinated.

Several centuries before, the Durotrigian heartland had been dominated by six huge hillforts, each with several ramparts: Maiden Castle, Eggardon Hill, Ham Hill, South Cadbury Castle, Hod Hill, and Badbury Rings. Tribal territories spread out from these power centers, which were roughly equidistant from each other. By 100 BC, the three biggest hillforts—Hod Hill, Cadbury, and Maiden Castle—had emerged as the most powerful, vying with each other for supremacy; this can be seen in the increasing elaboration of their showy defenses. They evolved into towns, and Maiden Castle was the most important of them. It emerged as the capital, with rows of round, thatched houses ranged along streets (see People: Dwellings).

The site began as a Neolithic enclosure on the eastern summit in 3700 BC and was turned into an unusual monument, a huge bank barrow, in 3200 BC. In the Bronze Age a small henge was laid out at what would be the center of the Iron Age hillfort. In 350 BC a small hillfort was laid out on the site of the Neolithic enclosure. In 200 BC a much larger hillfort was created by extending the single rampart westward to encompass the western summit. A hundred years later this was elaborated with extra ramparts.

After the Durotriges’ resistance to the Romans was crushed, the site was abandoned. In about AD 70 the Romans built an open settlement, Durnovaria, on low ground to the north; this has become Dorset’s county town, Dorchester.