Empirical Evaluation of Female Combatant Prevalence

In chapter 1 I presented a theory of rebel mobilization of female fighters that coupled core insights from existing demand-side theories of rebel recruitment with leader expectations of and tolerance for the potential costs associated with this decision. More specifically, I argued that the leaders of armed groups that face resource demands that outstrip the supply of potential male recruits will become increasingly likely to create opportunities for women to participate in the armed wing of the movement, including allowing them to participate in combat. Yet, I also argued that not all groups facing resource mobilization challenges opt to recruit women; rather, the decision to respond to resource shortages by incorporating women into the movement is contingent on the group’s (and its constituents’) commitment to traditional gender norms. These arguments produced a series of hypotheses that linked the prevalence of female combatants in an armed group to (1) the severity of conflict-induced resource demands, (2) group political ideology, and (3) the interaction of these factors.

The case illustrations presented in chapter 3 probed the plausibility of the hypotheses and highlighted the dynamics of women’s mobilization for war and its implications. The quantitative analyses presented in this (and the subsequent) chapter represent a more systematic analysis of the factors associated with the decision to deploy female combatants. I discuss the data used to evaluate the hypotheses presented in chapter 1 and the results of the quantitative analyses in this chapter. I reserve the examination of the strategic implications of female fighters, which was the topic of chapter 2, for chapter 5.

The theory outlined in chapter 1 assumes that rebel leaders are able to coarsely evaluate the expected tradeoffs involved with adopting a given strategy. Herein, this trade off, which I describe as the dilemma of female recruitment, reflects the balance of the expected benefits of recruiting women (easing resource constraints) and the expected costs associated with that decision (e.g., constituency backlash or internal dissent). Fully assessing the rationale that guides rebel leaders to recruit or exclude women is exceedingly difficult, and it is not my intention, nor is it possible using the data and methods I adopt, to thoroughly investigate the individual motives of any specific leader.1 Nonetheless, in this chapter I examine a series of indicators that should serve as reasonable proxies for the factors that I argue are likely to influence rebel decision-making. The results of the analyses allow me to identify a set of general conditions that influence the prevalence of female combatants in armed resistance movements.2

Concepts and Measures

In order to systematically assess the hypotheses presented above, I conduct a series of statistical analyses using novel cross-national data on the presence and prevalence of female combatants in large sample of contemporary rebel movements. Before delving into the technical aspects of the methodology, it is useful to first identify the variables utilized in the analyses and discuss their ability to capture the core concepts reflected in the prior arguments. In this section I therefore devote substantial attention to the measure of female combatant prevalence used in the analyses, including the operational definition of “female combatants” and the data collection process. I also discuss the relevant predictors and control variables used in the statistical analyses.

The Women in Armed Rebellion Dataset (WARD)

Systematically examining the relationships posited in the hypotheses above requires data on the presence and prevalence of female combatants in a variety of rebel movements. I therefore utilize measures from an updated version of the Women in Armed Rebellion Dataset (WARD) (Wood and Thomas 2017) as the dependent variables in all analyses presented in this chapter. Similar datasets capturing various aspects of women’s inclusion in armed groups have emerged in recent years, demonstrating the interest and efforts devoted to understanding patterns of female participation in armed movements. However, each faces shortcomings that limit its usefulness for assessing the hypotheses presented above. For instance, both the Thomas and Bond (2015) and Henshaw (2016a) datasets contain only binary measures reflecting the presence or absence of female combatants. Moreover, the Thomas and Bond (2015) dataset only includes armed groups in Africa while Henshaw’s (2016a) and Loken’s (2017) datasets are limited to armed groups in the post–Cold War era. Finally, Loken’s (2017) dataset is organized at the conflict level, preventing an assessment of the group-level factors that motivate the recruitment of female combatants. I therefore rely on a revised version of WARD for the analyses conducted in this chapter because of its superior geographic and temporal coverage and because it includes an estimate of the prevalence of female fighters within an organization rather than a simple binary measure of their presence.3

The updated WARD includes information on the prevalence of female fighters for a sample of more than 250 rebel organizations active between 1964 and 2009.4 The list of groups included in the UCDP Dyadic Dataset (Harbom, Melander and Wallensteen, 2008) defines the sample of rebel groups included in WARD. Because the primary intention of WARD is to identify female fighters in rebel groups, international conflicts and civil conflicts that involve only military factions (e.g., coups) were excluded from the analysis. Ultimately, WARD includes data on approximately 70 percent of cases included in this subset of the UCDP Dyadic Dataset.

Many of the cases for which data are missing represent examples of factions of other rebel movements. For example, the FMLN was formed as an alliance of five distinct rebel movements,5 two of which are included as distinct actors in the UCDP Dyadic Dataset along with the FMLN. However, despite the substantial amount of information available on women’s participation in the FMLN, very few of the relevant sources located in the data collection process explicitly discuss women’s involvement in the different factions. As such, WARD includes only a single score for the umbrella group (FMLN). Similarly, the UCDP dataset identifies a variety of irregular and formal Croatian, Bosnian, and Serb forces involved in the interconnected conflicts in the former Yugoslavia. While there is sufficient information to determine the presence of female fighters in the Serbian Republic of Krajina, Serbian Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Croatian Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, there is insufficient evidence to determine whether or not women participated in the various “irregular forces” that the UCDP includes as participants in the conflict. Similarly, for some groups there is very little information.6 For instance, coders were unable to locate information of any kind about the composition, attitudes, or actions of the Lahu National United Party (LNUP) in Myanmar or on the Mouvement du Salut National du Tchad (MOSANAT) in Chad, let alone on women’s roles in the movements. As such, these groups are coded as missing.

The temporal domain of the dataset was chosen for both practical and theoretical reasons. Data collection is highly time intensive, and information generally becomes less reliable and less readily available as the time frame stretches further into the past. Women’s participation and roles within armed groups are not reported in any standardized manner; nor are these data stored in any centralized repository. Gathering such data requires an extensive search of a wide range of resources, including news reports, academic accounts (e.g., books and articles), biographies, governmental sources, and international and NGO reports. While the coding process required a substantial investment of human resources, it was nonetheless important to ensure that the dataset included a wide variety of civil conflicts occurring in many different locations, organized around a range of different political disputes, and operating in different global contexts. Achieving sufficient variation among these dimensions therefore necessitated coding a global sample of groups active during and after the Cold War. Importantly, the variables included in WARD provide only a snapshot of women’s participation in armed groups. While the ideal dataset would account for variations in the proportion of female fighters over time, the same information constraints that prevent a more precise measure of female combatant prevalence (see below) prevent the construction of a time-series dataset. Consequently, the dataset only captures cross-sectional variation in women’s participation in armed rebellions.

The conceptualization and operationalization of female fighters draws on definitions commonly used in disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) programs sponsored by the United Nations and related international organizations. These programs often differentiate female combatants from females associated with armed groups (UN Women 2012, 22–23).7 Specifically, they define these categories as follows:

Female combatants: Women and girls who participated in armed conflicts as active combatants using arms.

Female supporters/females associated with armed forces and groups: Women and girls who participated in armed conflicts in supportive roles, whether coerced or voluntarily. These women and girls are economically and socially dependent on the armed force or group for their income and social support. Examples: porters, cooks, nurses, spies, administrators, translators, radio operators, medical assistants, public information workers, camp leaders, or women/girls used for sexual exploitation.

The variables included in WARD reflect these basic definitions. In the dataset, female combatants refers to all female members who underwent military training, received combat arms, and participated in organized combat activities on behalf of the organization in any capacity at any time during the conflict. This definition excludes women and girls who exclusively occupied noncombat support roles such as those noted above. It is important to note, however, that while female members of rebel movements often occupy multiple roles that blend combat and noncombat activities, key criteria for the noncombat designation is that these women did not receive combat training, carry weapons, or engage in the direct production of violence.

One of the primary challenges in coding information on women’s participation in rebel movements is that the boundary between formal combatant and other roles is often blurred, particularly in the case of guerrilla conflicts. Consequently, the definition of combatant applied by WARD includes women employed in an array of activities ranging from frontline infantry to local militias, to women who were primarily deployed in support roles but who, by virtue of their training and access to weapons, engaged in combat when the situation demanded. For example, Viterna (2013, 129–130) notes that a substantial proportion of female FMLN guerrillas were employed as “expansion agents” whose primary role was recruitment and community engagement. Yet, these (armed) units were occasionally called into battle when frontline forces required additional support and engaged in combat if, in the conduct of their primary duties, they encountered government security forces. Similarly, the majority of ZANLA’s female guerrillas were assigned to support roles such as carrying ammunition and weapons to the front and helping to evacuate wounded soldiers from it. While not considered frontline combat troops by the rebel leadership, these women sometimes engaged in combat because their assignments put them in close proximity to enemy troops. Consequently, as in other guerrilla conflicts, women were often on the frontlines of the Rhodesian conflict because there was no clear boundary between the front and the rear (Lyons 2004, 170). More specifically, the operational criteria for fighter used in the coding process includes any references to women undertaking any of the following activities on behalf of the rebel group:

- Using arms in combat, including during defensive actions (e.g., protecting camps, returning fire when attacked during noncombat operations, etc.) or against civilian targets

- Operating artillery or antiaircraft weapons against enemy targets

- Service in auxiliary and militia forces, provided that they sometimes participated in offensive or defensive combat operations

- Detonating mines or other explosives against enemy or civilian targets

- Conducting assassinations

- Conducting suicide bombings

Making a determination of the presence of female combatants in an organization required the confirmation of three independent sources. When reports explicitly stated that women did not participate in combat, when women’s roles were described as exclusively supportive (e.g., caregivers, fundraisers, couriers, etc.), or when it was not possible to locate any evidence of women participating in combat (despite locating substantial information regarding other group characteristics), the group was coded as not including female combatants. I discuss the challenges of determining the absence of female combatants in more detail below.

The primary variable used in the analyses, female combatant prevalence, is a categorical indicator roughly accounting for the estimated proportion of a group’s combat force composed of women. The categories range from 1, indicating “no evidence” of female combatants, to 3, representing a “high” prevalence of female combatants. WARD relies on a categorical indicator rather than a direct estimate of the proportion of female combatants in an armed group largely because different sources sometimes provide varying estimates of the numbers of women serving as combatants. For example, different sources report the proportion of women in the LTTE as ranging between 15 percent and 30 percent (e.g., Alison 2004, 450; Stack-O’Connor 2007a, 45). Where available, the coding relies on reported percentages or numbers of female troops.8 However, in many cases, the sources provide only qualitative descriptions of the extent of women’s participation (e.g., “rare,” “small numbers,” “very few”). This is particularly true of groups that appear to have few female combatants. The blunter coding scheme therefore reflects a tradeoff between precision and confidence in the measure. The dataset also contains the variable female combatants, which is simply a dichotomization of the prevalence variable, as well as additional variants of the prevalence measure, which are discussed in more detail below. Table 4.1 briefly describes the categories of female combatant prevalence.

Table 4.1 Description of Female Combatant Prevalence Categories

|

Category |

Prevalence |

Estimated percentage |

Examples |

|||

|

0 |

No evidence |

0 |

Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance (MFDC) Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG) Eritrean Liberation Front (ELF) |

|||

|

1 |

Low |

< 5 |

Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) Resistência Nacional Moçambicana (RENAMO) |

|||

|

2 |

Moderate |

5–20 |

Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) Contras |

|||

|

3 |

High |

> 20 |

Movement for Democracy in Liberia (MODEL) Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) |

Note: All examples reflect the “best” estimate of female combatant prevalence from WARD.

Owing to both conflicting estimates of the extent of women’s participation and the fact that available sources do not always clearly differentiate between female combatants and women who engaged in noncombat roles, WARD also includes an alternative “high” estimate of the female combatant prevalence indicator. The case of GAM in Aceh is illustrative. While some available sources suggest that women may have participated in combat operations on rare occasions (Aspinall 2009, 93; Jaulola 2013, 36–37), others assert that women were explicitly denied combat roles or strictly limited to support roles (Barter 2015, 349; Schulze 2003, 255). Based on the overall weight of available evidence, GAM is assigned to category 0 in the more conservative “best” estimate variable. However, it receives the alternative score of 1 in the less restrictive “high” measure of female combatant prevalence.9

Similarly, as I discussed in chapter 1, suicide bombers represents a distinct class of combatants, and female suicide bombers are arguably unique in that in some armed groups they represent the only “combat” role allowed to women. In such cases, they typically represent only a tiny fraction of the group’s combat force, often numbering in the single digits over the span of the entire conflict. Moreover, they seldom appear to receive the same training or are given the same responsibilities as other fighters. Considering female suicide bombers as “combatants” may therefore amount to conceptual stretching because of the unique nature of the role. Consequently, WARD also includes an additional version of the female combatant prevalence variable that excludes cases in which women were exclusively used as suicide bombers and were otherwise denied combat roles in the organization.

A persistent challenge in coding WARD is accurately assessing the absence of female combatants. Indeed, the possibility of false negatives, in which a group is potentially incorrectly coded as having no female fighters when in fact it included some number of female fighters, represents a much larger challenge than false positives, where a group is incorrectly coded as having female fighters when no women ever participated in combat. While there is often variation in the details regarding the number of women in the organization and how frequently they participated in combat, there are few cases where there are competing assertions about women’s participation in conflict. WARD includes twenty-five cases (less than 10 percent of the sample) for which there is some ambiguity as to whether or not women ever participated in combat. In the vast majority of these cases, the different “best” and “high” scores assigned to the group reflect the use of vague language regarding women’s roles in the source documents. For instance, there may be references to “female cadres,” “women rebels,” or “women taking up arms,” which obscure the particular role women played in the group and make it difficult to discern whether or not these female members of the group ever participated in combat. The “best” measure therefore reflects the conservative case that these women were members of the group but not combatants, while the “high” score reflects the more liberal interpretation of the terms and considers these women to be combatants. Thus, unless multiple sources unanimously inaccurately report that women served in combat when they in fact did not, which seems unlikely, the risk of false positives appears low.

The absence of information regarding women’s roles in the rebel organization presents a greater challenge. In these cases, establishing with any degree of certainty that women did not serve in combat roles is difficult. As noted above, the sample included in WARD already excludes a number of rebel organizations for which a dearth of information exists and for which no information on women’s participation was located. For the remaining 250-plus groups, coders were able to locate substantial information about the group, including information about its origins, leaders, activities, ideology, and so on. In most cases, coders also located information explicitly discussing the roles of women within the organization, women’s support for the group, and/or detailed discussions of the group’s gender attitudes. In some cases, there was clear information that women were members of the group’s political or military wing and actively supported the group’s military operations but did not participate in combat. For instance, one source on women’s roles in the MILF in the Philippines asserts that while women are not allowed to serve as combatants, women do assist the movement with “medical, communication, and other auxiliary needs” through its women’s wing (Santos and Santos 2010, 359). Similarly, a source used to code the MFDC in Senegal contends that “although there have been no reports of female combatants,” women assist the rebellion by providing food, ammunition, transportation and other services (Stam 2009, 343).

Reports explicitly noting the absence of women in the organization or describing their roles within the movement were located in roughly 71 percent of the cases included in WARD. The remaining 29 percent represent the subset of cases for which coders were able to locate substantial information about the group but were unable to locate clear references to women’s roles within the group, information confirming or denying the absence of women combatants, or any relevant information about the group from which women’s participation could be inferred. The absence of female combatants is assumed in these cases. Given that women’s participation in combat—or even their participation in noncombat military roles—is so frequently viewed as a novelty or as a challenge to existing societal norms, it seems unlikely that the presence of women would go completely unreported. Nonetheless, WARD includes a binary variable entitled low information to denote these cases. As robustness checks for the analyses presented below, I rerun the models on only the subset of cases for which explicit information on female combatants was located.10

Figure 4.1 Distribution of female combat prevalence categories

The distributions of the versions of the various measures of female combatant prevalence for the sample are presented in figure 4.1. The histogram located in the left-hand panel of the figure shows the distribution for the variable representing the best estimate of female combatant prevalence. According to that estimate, almost 61 percent of the groups in the sample show no evidence of female combatants, while roughly 22 percent have a low prevalence of female combatants, and 11 percent and 6 percent, respectively, have a moderate prevalence and a high prevalence. The trend is similar across the other two variables accounting for female combat prevalence, though the distributions change slightly. The less restrictive high estimate of the measure, which is illustrated in the center panel of the figure, reduces the number of groups in the sample without evidence of female combatants to approximately 51 percent, slightly increases the proportion of groups coded as having a moderate prevalence of female combatants, and almost doubles the number of groups reported as having a high level of female combatant prevalence.

The right-hand panel shows the distribution of cases in the sample using the version of the measure that excludes cases in which women only participated as suicide bombers. This measure results in a reduction in the proportion of groups coded as having a low prevalence of female combatants and a corresponding increase in the groups that were coded as having no female combatants, but otherwise the distribution is unchanged. This is not surprising since suicide bombers rarely account for more than a handful of the fighters in any group, and female suicide bombers represent a small subset of all suicide bombers in most cases. Overall, there are eleven groups included in the sample (about 4 percent of the total) in which women served as suicide bombers but were excluded from any other combat roles. Despite these differences, the measures paint very similar overall pictures of the prevalence of female combatants in rebel groups.

Figure 4.2 shows the temporal variation of the “best” estimate measure of female combatant prevalence.11 The distributions of the data across the four categories of the variable are fairly similar, which suggests that the prevalence of female combatants has not radically changed over the decades for which data are available. However, there is one trend in the data that deserves some additional scrutiny. Across the decades represented in the panels, it appears that the number of cases for which there is “no evidence” of female combatants declines as the temporal window advances, while the number of cases in which there is evidence of a “low” prevalence of female fighters increases. The change is not particularly dramatic—for instance, the proportion of cases for which there is “no evidence” of female combatants declines by 7 percent between the first and second panels and by 4 percent between the second and third panels. Nonetheless, the trend may be indicative of greater information availability for more recent conflicts.

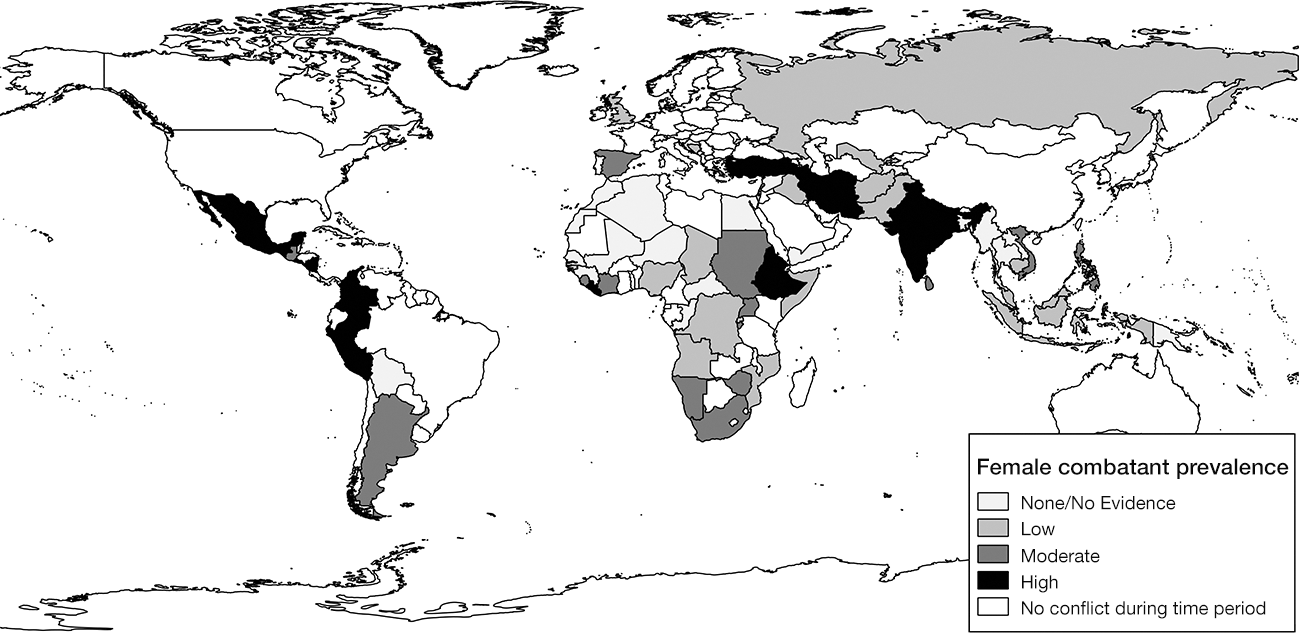

Figure 4.3 shows the geographic variation in the prevalence of female fighters. Specifically, the figure shows the highest level of the “best” estimate measure of female combatant prevalence for all groups active in the state between 1964 and 2009. States that did not experience a civil conflict during this time period are colored white. States that experienced a civil conflict but for which there is no evidence of female fighters within the rebel group(s) that fought in the country during the specified time period are indicated with light gray shading. Medium gray shading indicates states in which at least one group had a “low” prevalence of female fighters. Dark gray reflects a “moderate” prevalence of female fighters, and black indicates a “high” prevalence of female fighters in at least one group in the state.

Figure 4.2 Distribution of female combat prevalence categories by time period

The figure confirms previous assertions that female fighters are a global phenomenon (e.g., Mazurana et al. 2002). Indeed, some number of female combatants were present in roughly three quarters of countries experiencing a civil conflict during the period specified. However, the figure also illustrates some geographic variation. Particularly, female combatants are most prevalent in Latin American conflicts during this period. In addition, the high frequency of female fighters across Latin America and within a number of contiguous countries in southern and western Africa and the absence of female combatants in North Africa suggests a certain degree of geographical clustering.12 It is important to note, however, that many countries hosted multiple different rebel groups during this time period. Given that most rebel groups exclude women from combat roles, the variation in the presence of female combatants seems to be greater across groups than across countries. This suggests the need to consider group-level characteristics when theorizing about the factors associated with the presence and prevalence of female fighters.

Figure 4.3 Maximum female combatant prevalence by country, 1964–2009

Resource Demands and Conflict Costs

In chapter 1, I hypothesized that as the severity of the conflict increases, the prevalence of female combatants is expected to increase. Ideally, it would be possible to account for the specific resource constraints imposed on rebels during the conflict. For example, an estimate of the ratio of recruitment rates (supply) and loss rates (demand) would effectively capture the recruitment shortfalls in human resources that I hypothesize drive rebel leaders’ decisions to open combat positions to women. Unfortunately, the components necessary to construct this measure do not readily exist. Consequently, I rely on the annual rate of battle-related deaths as a proxy measure for resource demands.

The variable annual battle deaths represents the natural log of the average number of deaths per annum that are attributed to the conflict in which the group was engaged. While this variable does not explicitly capture the gap between and loss and recruitment, it should nonetheless capture some element of the human resource demands imposed on rebel groups by the conflict process. Specifically, as the severity (e.g., death rate) of the conflict increases, rebels must locate increasingly greater numbers of troops to take the place of those lost in battle. Data for this variable come from the Battle Deaths Dataset (v3.0) (Lacina and Gleditsch 2005) available from the Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO). To construct this variable, I calculate the total number of battle deaths that occurred during the years in which a given group was actively engaged in armed conflict with the state and divide that value by the number of years during which the group was active.13

One potential issue associated with the use of the data from the Battle Deaths Dataset is that it reflects the total number of deaths from a conflict—including those accruing to the state and to any other nonstate actors involved in the conflict—rather than the number of deaths suffered by a specific rebel movement. For this reason, I also employ a similar measure created using data from the UCDP Battle-Related Deaths Dataset (Allansson, Melander, and Themner 2016) as a robustness check. This measure captures the number of deaths suffered only by the specific rebel group under observation. The primary drawback of this measure is that its temporal domain extends back only to 1989, nearly halving the sample size. Nonetheless, the results are generally robust to this measure.

Political Ideology

In order to evaluate the hypotheses related to group ideology, I rely on the binary indicators previously constructed by Wood and Thomas (2017).14 To construct their measures, the authors relied on multiple existing databases, including the Nonstate Armed Groups (NAGs) Dataset (San-Akca, 2015); the (now-defunct) Terrorist Organization Profiles (TOPs), which were previously available from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START 2016), and the Big Allied and Dangerous (BAAD) Dataset (Asal and Rethemeyer 2015). Overall, the ideologies assigned to the groups in the sample are highly consistent across the various sources. However, in the few cases in which the coding differs, additional sources were consulted to make a determination. These databases typically assign groups to a few broad ideological categories, including leftist, rightist, religious, nationalist, no ideology, and so on. Using this information, Wood and Thomas constructed the following mutually exclusive binary indicators reflecting a group’s primary ideology: leftist, religious, secular nationalist, and secular (other). While these categories are not exhaustive, they reflect the primary ideological categories of the majority of the rebel groups included in the sample.

Leftist rebellions include all groups that adopt a Marxist-inspired ideology (e.g., socialist, communist, Maoist, Marxist-Leninist, and so on). Religious groups are those that organize specially around a defined religious doctrine or set of religious beliefs. In most cases, these are groups who seek to impose their group’s religious doctrine on the areas and/or population over which they exercise control or seek to implement a legal or political system based explicitly on their group’s religious principles. Importantly, having a membership drawn primarily from one religious community or simply organizing around a specific religious identity is not sufficient to be coded as having a religious ideology. Such groups are generally coded as nationalist. Rather, religious movements must advance a set of social or political objectives that reflect the belief system or values of their specific religious community and seek to impose them on the areas they govern or control.

Secular nationalist groups mobilize on behalf of a distinct ethnic or national community with the intention of advancing the interests of that community, often through establishing autonomy or self-governance. I exclude nationalist movements that also advance religious or Marxist goals from this category in order to isolate the specific effects of each ideology. However, in alternative tests discussed below, I further disaggregate leftist and religious groups by those that also include a nationalist component in order to assess the extent to which nationalist beliefs interact with the other ideological categories. Finally, the variable secular (other) includes all remaining groups that did not advocate a nationalist, religious, or leftist ideology. This includes groups that did not appear to espouse a specific ideology as well as a handful of groups that espoused other ideologies that did not fit in the other categories.15

The distribution of ideologies for the rebel groups included in the sample is presented in figure 4.4. In the sample, 20 percent of the groups espoused a Marxist, Maoist, or other leftist ideology, while 21 percent of groups adopted a religious ideology. Thirty-four percent of groups in the sample adopted a secular nationalist ideology that did not include any variant of Marxism, and 24 percent of groups adopted some other secular ideology (again excluding leftist ideologies). As noted above, the ideology variables are constructed such that nationalism is not a mutually exclusive ideology. Rather, with the exception of secular nationalist, nationalist groups that also adopt Marxist or religious ideologies are subsumed by those ideological categories. Overall, 47 percent of the groups included in the sample espouse some form of nationalist ideology or advance nationalist goals. Roughly 71 percent of all nationalist groups are included in the category secular nationalist, while 15 percent are included among the leftist category and 14 percent are included in the religious category.

Figure 4.4 Distribution of ideologies for rebel groups in the sample

Other Independent Variables

I also include several potentially relevant confounding variables in the statistical analyses. These variables are intended to account for alternative factors that may influence the presence or prevalence of female combatants within a rebel movement. The first such variable is the duration of the conflict. Anecdotal evidence suggests that rebel groups are often initially reluctant to recruit female fighters but eventually become more willing to include women in combat roles. As I argued, resource demands, which often become more acute over time, are a primary driver of the decision to incorporate female combatants into the movement. However, it is possible that duration exerts an independent influence on leaders’ decisions, such that over time groups simply become more willing to accept women into the ranks and to deploy them in combat. This could occur either because women eventually pressure the group to include them and to provide them with more expansive, prestigious roles or because over time women are able to effectively demonstrate their capabilities and commitment to skeptical rebel leaders. For this reason, I include the variable duration, which is operationalized as the log-transformed value of the number of years between the group’s initiation of violent conflict with a government and its cessation of those hostilities as reported in the UCDP Dyadic Dataset.16

I also include a variable accounting for the use of forcible recruitment strategies by rebel groups. I include this variable because rebel groups that rely on them are often indiscriminate in their selection and may be more likely to recruit female fighters to fill resource needs. Groups that face acute resource demands are also more likely to engage in forced recruitment, which necessitates the inclusion of a variable accounting for this recruitment strategy. The binary measure forced recruitment reflects whether abduction or other forcible recruitment strategies are ever employed during a given conflict. Data on rebel use of forced recruitment is taken from Cohen (2013a). One potential limitation of this indicator is that it only reflects forcible recruitment at the conflict level and does not explicitly identify whether a specific group relied on this strategy.17 Regardless, to my knowledge it is the only readily available cross-national measure of such behavior covering the majority of groups included in this sample.18

Previous research suggests that some rebel groups may employ female suicide bombers because they provide the group certain tactical and strategic advantages. Particularly, female bombers are more likely to avoid scrutiny by security agents and may be more effective and more lethal in their attacks (Bloom 2011; O’Rourke 2009). For this reason, groups that routinely rely on suicide terrorism may also be more likely to recruit women and to deploy them in this role. It is worth nothing that not all groups that use suicide terrorism employ female bombers; moreover, some groups that utilize women in such roles also employ them in other types of combat roles. The variable suicide terrorism is a binary indicator reflecting whether or not the group used suicide bombings as a war strategy. Information for the measure is taken from the Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism (2015).

I include the variable population size because rebel groups active in countries with large populations should theoretically have a larger pool of recruits to draw from, thus potentially mitigating the need to recruit female combatants as conflict costs rise. In other words, a large pool of potential male recruits would reduce the pressures on reluctant rebel leadership to open combat positions to women. This variable is operationalized as a natural log of the average size of the population of the country in which the conflict took place during the years in which the group was active. The measure is adapted from data available in Gleditsch (2002).

The binary indicator active 2000s reflects cases ongoing after 1999. As shown in figure 4.2 above, the distribution of the prevalence of female combatants varies somewhat by decade. Most notably, the proportion of cases with high levels of female combatants marginally increases while the proportion with no evidence of participation appears to decline somewhat for conflicts surviving into the 2000s. I therefore include these indicators to help adjust for the differences across these time periods. Specifically, they account for potential bias caused by the possibility that more (or better) information is available for more recent conflicts. If this were the case, I would expect that groups that were active in more recent years would be more likely to be coded as having female combatants. However, it is also possible that global advancements in women’s rights and status have also positively influenced the likelihood that rebels recruit women for combat roles. In either case, these variables should help capture this trend.

Finally, fertility rate is a measure of the number of live births per woman in a given country. I use this measure to capture the general status of women in society and the rights and privileges afforded to them. While this is a crude measure, it has been commonly employed in previous studies as a proxy for women’s status in a society because it “captures multiple aspects of the complex matrix of discrimination and inequality” (Caprioli 2005, 169). High fertility rates indicate a social expectation that women’s primary duties are childbearing and motherhood, and, in practice, inhibit women from participating in social and economic activities at rates comparable to men. Where fertility rates are high, women are less likely to be as educated as men, to work outside the home, and to engage in political activism. All else being equal, countries in which women face the greatest pressures to assume maternal roles at the expense of other positions in society are the least likely to produce armed groups that are willing to deploy women in combat. This indicator is taken from the World Bank’s (2018) “World Development Indicators.” Because the data on women’s participation in armed groups are time invariant, I use the value at the start of the conflict. A country’s fertility rate may vary as a function of the severity of the war, which is included in the model as an independent predictor. As the costs of war increase, the annual number of births is likely to decline due to the deterioration of the healthcare system, the displacement of the population, and the dissolution of family structures.19 Using the value at the start of the conflict reduces potential endogeneity among these variables.

Analysis and Results

The dependent variables in the following analyses are the various measures of the presence and prevalence of female combatants contained in WARD. I rely on probit models to assess the probability of observing the presence or absence of female combatants in a rebel group (female combatants). In order to assess the prevalence of female combatants (female combatant prevalence) in a rebel group, I employ ordered probit models, which are a generalization of the probit regression that explicitly models the likelihood of observing one of multiple possible discrete outcomes on an ordinal scale.20 I cluster standard errors on the country in which the conflict occurred in all models in order to correct for correlation among conflicts occurring within the same country.

I present the results from the regression analyses in table 4.2. The various models utilize the versions of the female combatant indicators specified at the top of each column. Models 1 and 2 report the result of the probit model using the binary female combatants indicator as the dependent variable. Models 3 through 7 include results from ordered probit models in which the various ordinal measures female combatant prevalence are employed as the dependent variable. Overall, the results provide support for the primary hypotheses related to the expected roles that conflict costs and rebel political ideology play in determining the prevalence of female combatants in an armed group. The variable annual battle deaths, which served as a proxy for group resource demands, is positive and statistically significant across all of the models. These results indicate that as the severity of the conflict increases, the prevalence of female combatants is expected to increase. This corresponds to one of the core arguments made in chapter 1: rebel leaders’ decisions to deploy women in combat often come as a result of growing resource demands produced by the expansion of intensification of the conflict. This result is consistent with Hypothesis 1.

Table 4.2 Factors Influencing Presence and Prevalence of Female Combatants

|

Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

Model 7 |

||||||||

|

Female combatants |

Female combatants |

Female combatant prevalence (best) |

Female combatant prevalence (best) |

Female combatant prevalence (high) |

Female combatant prevalence (excluding suicide) |

Female combatant prevalence (best) |

||||||||

|

Leftist |

1.176 (0.326)** |

1.321 (0.318)** |

1.290 (0.316)** |

1.488 (0.315)** |

1.351 (0.340)** |

1.439 (0.309)** |

1.536 (0.334)** |

|||||||

|

Secular nationalist |

0.295 (0.296) |

0.101 (0.262) |

0.062 (0.298) |

−0.038 (0.252) |

0.190 (0.289) |

−0.070 (0.253) |

−0.042 (0.257) |

|||||||

|

Religious |

−0.141 (0.383) |

−0.760 (0.431)* |

−0.317 (0.367) |

−0.654 (0.376)* |

−0.920 (0.462)* |

−1.097 (0.503)* |

0.691 (0.680) |

|||||||

|

Annual battle deaths† |

0.123 (0.068)* |

0.186 (0.057)** |

0.118 (0.058)* |

0.164 (0.049)** |

0.173 (0.049)** |

0.199 (0.055)** |

0.230 (0.060)** |

|||||||

|

Duration† |

0.227 (0.082)** |

0.258 (0.097)** |

0.194 (0.077)** |

0.159 (0.088)* |

0.271 (0.099)** |

0.241 (0.098)** |

0.172 (0.088)* |

|||||||

|

Forced recruitment |

0.417 (0.236)* |

0.356 (0.207)* |

0.452 (0.203)* |

0.385 (0.210)* |

0.329 (0.203)* |

|||||||||

|

Suicide terrorism |

0.906 (0.418)* |

0.335 (0.305) |

0.499 (0.304) |

−0.631 (0.396) |

0.308 (0.312) |

|||||||||

|

Population size† |

−0.079 (0.070) |

−0.036 (0.070) |

−0.046 (0.063) |

−0.038 (0.071) |

−0.030 (0.068) |

|||||||||

|

Fertility rate |

−0.115 (0.068)* |

−0.081 (0.053) |

−0.129 (0.053)** |

−0.093 (0.056)* |

−0.079 (0.051) |

|||||||||

|

Active 2000s |

0.381 (0.266) |

0.416 (0.209)* |

0.352 (0.206)* |

0.342 (0.221) |

0.433 (0.209)* |

|||||||||

|

Religious* |

−0.191 |

|||||||||||||

|

Annual battle deaths† |

(0.090)* |

|||||||||||||

|

Wald X2 |

33.64 |

80.31 |

57.63 |

90.67 |

119.41 |

102.96 |

102.46 |

|||||||

|

BIC |

321.88 |

278.23 |

506.89 |

446.65 |

491.59 |

403.55 |

449.43 |

|||||||

|

N (groups) |

249 |

220 |

249 |

220 |

220 |

220 |

220 |

**p < 0.01

*p < 0.05 (one-tailed test)

†natural log

Note: Coefficients from probit (Models 1 and 2) and ordered probit (Models 3–7) models with standard errors (clustered on conflict country) in parentheses.

The results of the variables accounting for group ideology are also generally consistent with the hypotheses presented above. Because the ideology variables are mutually exclusive, the coefficients compare the effect of a given ideology to the excluded base category, which in all cases is secular (other). Across the various models, leftist is statistically significant and positively signed. Moreover, the absolute value of the coefficient on this variable is much larger than that of any of the other binary variables, suggesting that it exerts the largest substantive impact of any of the ideology variables. I address the substantive effects of the variables in more detail below. For now, it is sufficient to say that the results suggest that groups embracing Marxist, Maoist, or other similar socialist ideologies are much more likely to recruit a larger proportion of female combatants than groups espousing other political ideologies. This result is consistent with Hypothesis 2.

By contrast, the signs of the coefficients for religious are negative across all of the specifications, and it is statistically significant in the majority of them. It is important to note that the two cases in which the variable fails to achieve statistical significance are those that do not include the control of suicide terrorism. In other words, after accounting for this variable, and acknowledging that this represents the only combat role available to women in many radical religious movements, the religious ideology variable becomes a significant predictor of both the absence of female combatants (Model 2) and a lower prevalence of female combatants overall (Model 4). This relationship is also apparent in the increase in the absolute value of the coefficient in Model 5, which uses the version of female combatant prevalence that excludes cases where women only served as suicide bombers. These results support the assertion that groups organized principally around religious beliefs and goals are comparatively less likely to recruit substantial numbers of female combatants. They therefore provide broad support for Hypothesis 3.

While the religious and leftist variables appear to exert a significant influence on the likelihood of observing female combatants, the variable secular nationalist, which reflects groups that were primarily organized around the interests of a specific ethno-national community but adopted neither a religious ideology nor a Marxist-oriented ideology, fails to achieve statistical significance in any model. Moreover, the sign on the coefficient reverses across the specifications. This result therefore suggests that nationalist rebel movements are no more or less likely than the secular non-Marxist rebel groups (the excluded category) to recruit female fighters. Moreover, the results also imply that they are comparatively less likely to recruit female fighters than leftist rebel groups but more likely to recruit female fighters than religious movements.

The absence of a statistically significant relationship between nationalist ideologies and female combatants may appear somewhat surprising. As I noted in chapter 1, some previous studies have asserted that nationalism inherently promotes patriarchy and forces women (and men) into traditional roles. Yet, as highlighted therein, nationalism often interacts with other political ideologies, producing a wide range of attitudes toward women’s roles in combat. As such, nationalism itself may exert little independent influence on group attitudes toward the deployment of women in combat, and nationalist ideologies may be highly malleable with respect to attitudes toward gender norms and women’s roles. As such, the prevalence of female combatants in these groups is likely to be shaped by the other ideologies that are often grafted onto nationalist movements. For instance, nationalist movements that also adopt Marxist ideologies (e.g., the EPLF, PKK, and ETA) are more likely to include female combatants, while those that incorporate orthodox religious beliefs (e.g., ASG or Hamas) are unlikely to deploy women in combat.

In order to more directly assess the role of nationalist ideologies on female combatant prevalence, I conducted a series of additional analyses. First, I replicated the models presented in table 4.2 but included only a variable for nationalist ideology in place of the other ideology indicators. This allowed me to determine if nationalist exerts any independent influence on the presence or prevalence of female combatants. Across each model in these alternative specifications, the variable is negative, but it does not achieve statistical significance. Second, I replicated the models, including the variables leftist, religious, and nationalist but interacted the nationalism indictor with each of the other ideology variables.21 These interactions allowed me to explicitly examine the potential conditional effect of nationalism on the prevalence of female combatants in groups espousing either leftist or religious ideologies.

Plotting the marginal effects of the interaction demonstrates that nationalist ideologies do not moderate the relationships between the other ideologies and the prevalence of female combatants; rather, the relationship runs in the other direction.22 However, the incorporation of leftist or religious ideologies substantially alters the likelihood that a nationalist group deploys female fighters. Specifically, nationalist groups that also adopt religious ideologies are less likely to utilize female fighters (e.g., MILF), while those that adopt leftist ideologies are more likely to employ women in combat (e.g., LTTE). This finding supports the assertion made in chapter 1 that the relationship between nationalism and women’s roles in rebel movements is primarily driven by other ideologies that may interact with nationalist beliefs. It also provides further evidence that nationalist ideologies fail to exert an independent influence on the prevalence of female combatants.

Before proceeding to the discussion of Hypothesis 4, which posited that ideology conditions the relationships between conflict severity and female fighter recruitment, it is helpful to illustrate the substantial independent influence that ideology exerts on the prevalence of female combatants. Figure 4.5 depicts the substantive effects of the various ideology indicators on the probability of observing female combatants. Each panel in the figure illustrates the predicted probability of a given outcome of the four-category female combatant prevalence measure (y-axis) by the specified political ideology espoused by a group (x-axis), based on the results from Model 4. The most notable aspect of the figure is the large substantive effect exerted by the presence of a leftist ideology. With the exception of the top-right panel, which plots the predicted probability of observing a low prevalence of female combatants in a group, the effect of leftist ideology dwarfs all other ideologies. For example, in the top-left panel, the prediction suggests that groups espousing leftist political ideologies have just over a 10 percent probability of having no female combatants. By contrast, groups espousing a predominantly secular nationalist or other secular ideology have just over a 60 percent probability of observing this level of female fighters, while the probability of no female fighters in groups with religious ideologies is over 80 percent. The effect is equally striking in the bottom-right panel, which shows the probability of observing a high prevalence of female combatants. Here, the probability of observing that prevalence of female fighters is approximately 35 percent for leftist groups but only about 3 percent for both secular nationalist and other secular movements, and less than 1 percent for groups with religious ideologies.

Figure 4.5 Predicted effect of group political ideology on female combatant prevalence

Finally, Hypothesis 4 proposed that the type of ideology the group embraces conditions the influence of conflict severity on leaders’ decisions to deploy women in combat roles. Rising conflict costs are expected to have a comparatively weaker influence on the decisions of the leaders of rebel groups adopting orthodox or fundamentalist religious ideologies than on groups espousing other ideologies. Thus, while secular rebel movements become increasingly likely to recruit and deploy female fighters as the resource costs produced by the conflict increase, those groups embracing religious ideologies are less likely to do so. In order to test this hypothesis, Model 7 includes a term reflecting the interaction of religious and annual battle deaths. In order to assess the significance of this proposed relationship and its substantive effect I present the predicted probabilities from that model in figure 4.6.

Figure 4.6 Conditional effect of annual battle deaths on female combatant prevalence

Each panel of the figure represents the probability of observing a given outcome of the four-category female combatant prevalence measure (y-axis) over the range of value of annual battle deaths (x-axis). The thick solid black and dashed black lines represent the predictions for groups espousing nonreligious and religious ideologies respectively. Examining the top-left panel of the figure, rebel groups that espouse religious ideologies as well as those that adopt nonreligious political ideologies both become less likely to completely exclude female fighters as conflict severity increases. However, the rate of the decline in these probabilities differs markedly over the range of the severity variable. For very minor conflicts, the difference between the two groups is minimal, and there is no statistically significant difference between them, as indicated by the overlapping confidence intervals. However, the difference between the two groups increases as conflict severity increases. At the mean level of annual deaths for conflicts in the sample (~6.5 on the logged scale), groups with religious ideologies are predicted to have an almost 85 percent chance of having no female fighters, while those with nonreligious ideologies have only a 60 percent chance of excluding female fighters. At one standard deviation above the mean (~8.5 on the logged scale), the likelihood of no female fighters declines to 35 percent for nonreligious groups but only to 80 percent for those with religious ideologies. Thus, while both groups become increasingly likely to recruit some number of female fighters as the conflict intensifies, the cost threshold at which rebel groups with nonreligious ideologies become willing to utilize female combatants is much lower than the threshold for religious groups.

The probabilities of observing a moderate prevalence of female combatants, which is depicted in the bottom-left panel, also illustrate this trend. For instance, religious and nonreligious groups are comparatively equally resistant to deploying substantial numbers of female combatants in minor conflicts. However, nonreligious groups become increasingly likely to do so as the conflict intensifies, while there is virtually no change in the odds that a religious movement utilizes female combatants. For a hypothetical conflict that is one standard deviation more severe than the sample mean (~8 on the logged scale), the probability of a nonreligious group employing a moderate prevalence of female combatants is approximately 15 percent, while the probability for a corresponding religious group is less than 4 percent. Moreover, for nonreligious groups this probability abruptly increases beyond this point, rising to almost 30 percent for the most intense conflicts. However, the probability of observing a high prevalence of female combatants remains essentially flat for armed groups embracing religious ideologies. These predictions suggest that group ideology—particularly the presence of a religious ideology—moderates the influence of conflict severity on the prevalence of female combatants. These predictions support Hypothesis 4.

Before concluding, it is worth reviewing the results of the control variables. First, consistent with the anecdotal evidence presented in chapter 1, the likelihood of observing female combatants is greater in longer conflicts compared to shorter conflicts. The variable duration, which reflects the logged value of the number of years the group was actively involved in armed conflict against the state, is positive and statistically significant across the specifications. Because the data employed in the analysis are time invariant, it is not possible to determine if rebel groups on average deploy women at a later date in the conflict. Nonetheless, these results indicate that the probability of observing female combatants increases as the duration of a conflict increases. They also indicate that factors such as group ideology and the intensity of the conflict are more influential in determining the prevalence of female fighters than the age of the group. For example, an increase in the logged duration of the conflict from the mean to one standard deviation above the mean decreases the probability of observing no female combatants from 88 percent to 84 percent and increases the probability of observing a high prevalence of female combatants from 2 percent to 3 percent. These changes are substantively much smaller than those resulting from comparable changes in the severity of the conflict or the differences between ideological categories.

It is also worth noting that group ideology conditions the relationship between conflict duration and female combatant prevalence. Much like the relation between conflict costs and the prevalence of female combatants, the likelihood that a group embracing a nonreligious political ideology utilizes female fighters increases as the duration of the conflict increases. By contrast, the likelihood that a religious rebel movement employs female fighters remains relatively flat regardless of the conflict’s duration. This is largely consistent with the arguments put forth in chapter 1, though these results may reflect evidence of an alternative, complementary mechanism as play. Specifically, they suggest that while leaders of secular armed movements might initially resist incorporating women into the group’s combat force, they become increasingly likely to do so as the conflict drags on and the resources necessary to sustain the movement continue to increase. However, consistent with the expectations of the theoretical arguments outlined in chapter 1, leaders of religiously motivated rebel movements continue to exclude women from combat roles.

The coefficient on the variable forced recruitment is positively signed and statistically significant in each of the specifications. These results support the claim that groups that rely on the forced recruitment of combatants are also more likely to deploy female fighters. This result is intuitive because groups that resort to involuntary recruitment methods to meet their resource demands are likely to be less selective in their recruitment. Indeed, such groups often utilize child soldiers, who are generally viewed as less effective combatants.23 This result is also generally consistent with the logic that underlies one of the principal arguments outlined in chapter 1. Given that the need for human resource inputs is a primary driver of forced recruitment, it makes sense that groups that engage in this practice are also more likely to recruit female combatants. In other words, similar processes may drive both strategies.

Somewhat surprisingly, while suicide terrorism is positive in most models, it achieves statistical significance in only a single model. This result contrasts somewhat with previous findings, which often identified reliance on terrorist tactics as a primary motivator for recruiting women. It is perhaps worth reiterating here that while some groups employ women as suicide bombers and in other combat roles (e.g., LTTE and PKK), the majority of groups that employ them as suicide bombers restrict their participation to only that role (e.g., Hamas and Boko Haram). Indeed, in this sample only six groups employed women as suicide bombers but also allowed them to participate in other combat roles, while eleven employed them exclusively to conduct suicide bombings. Moreover, as Wood and Thomas (2017) note, this appears to be the only combat role that women are afforded in fundamentalist Islamist organizations, which are also the most likely to utilize suicide terrorism.24 Thus, the effect of this variable on women’s participation seems to be largely driven by the presence of a (very) small number of female suicide bombers in extremist Islamist rebel groups and not a general relationship between suicide bombings and female combatants.

Population size is negative across the models in which it is included, but it is not statistically significant in any of them. Thus, groups with access to larger populations are on average no less likely than other groups to recruit female combatants. Consistent with previous studies (e.g., Thomas and Wood 2018), fertility rate is negative and statistically significant in most of the specifications in which it is included. According to these results, as the number of births per woman in a given country increases, the likelihood of observing female combatants declines. To the extent that this measure captures information about the social expectations imposed on women and the gender norms of the society, this result suggests that the extant social status of women is likely to influence rebel leaders’ willingness to deploy women in combat roles.

Lastly, the variable active 2000s, which indicates that a rebellion was active until at least the year 2000, is positive across the specifications and is significant in three models. Thus, those rebellions that were ongoing or began in the 2000s include greater numbers of female fighters than those that terminated in earlier time periods. This finding suggests that female fighters may have become more common in more recent years. Alternatively, it could suggest changes in news coverage, reporting, and general interest that have eased the task of identifying the presence of female combatants. In either case, the result indicates that the time period in which the conflict occurs is an important predictor of female fighter recruitment.

Conclusion

In this chapter I proposed a set of testable hypotheses based on the arguments set forth in chapter 1. I then outlined the data and methods used to assess the validity of those hypotheses and discussed the results of the analyses. Overall, the results reported above support the arguments made in chapter 1. As I argued, the decision to deploy women in combat roles (and the numbers in which to recruit them) rests with the groups’ leadership. As such, the critical question is what factors are likely to positively incline the leaders of rebel movements to open recruitment to women and to train, arm, and deploy them in combat?

The argument I present suggested that a combination of strategic and ideological factors shape leaderships’ decisions in this regard. More specifically, rising resource demands brought about by the intensification of conflict should, on average, increase leaders’ willingness to accept women into the groups’ armed wings as a way to address rising resource constraints. As the severity of the conflict increases, the prevalence of female fighters is therefore expected to increase. I further argued that the political ideology adopted by a group strongly influences the prevalence of female combatants. Revisionist and revolutionary ideologies are more likely to favor disrupting, challenging, and replacing extant social norms and orders, including those related to gender roles. By contrast, more conservative and traditionalist ideologies are more likely to favor preserving or reinforcing such norms and the structures that support them. An implication of this general relationship is that rebel groups that embrace leftist ideologies are much more likely to recruit and deploy female fighters, while fundamentalist and orthodox religious movements are much less likely to do so.

I empirically evaluated four hypotheses drawn from these arguments. Overall, the results presented above support these hypotheses. First, I find support for the general argument that sharply rising resource demands increase the probability of observing female combatants. Second, I find evidence that groups espousing leftist ideologies and those embracing religious ideologies represent opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of the prevalence of female fighters in their ranks. The former are much more likely to permit women to participate in combat, while the latter are much more likely to exclude them. I also find that groups with other ideologies, including nationalism and other forms of secular ideologies, occupy the middle ground between these poles. Furthermore, the results suggest that nationalism has no independent influence on the prevalence of female combatants. Nationalist groups are therefore no more or less likely than other groups to utilize female combatants. Rather, nationalism tends to intersect with other ideologies that do exert a significant influence on the prevalence of female combatants. Lastly, I found that group ideology—particularly the presence of a religious ideology, conditions the relationship between conflict severity and female combatants. In short, while nonreligious movements become more likely to mobilize women for war as resource constraints increase, armed groups espousing orthodox religious beliefs appear unwilling to adopt this strategy, even at the risk of jeopardizing the success of the rebellion.