THEMES & INSPIRATIONS

THEMES & INSPIRATIONS

GLOSSARY

bias cut Fabric cut on the cross, diagonally across the direction of the weave, which gives the material fluidity and the ability to cling to the body, achieving a close fit.

cheongsam A straight dress with a high collar, the skirt slit on one side, made from cotton or silk and traditionally worn by Chinese and Indonesian women.

crêpe de Chine Originally from China, this is light thin silky fabric, traditionally a mixture of silk and worsted (wool), now manufactured from synthetic fibers too, with the irregular crinkled surface of a crêpe fabric.

drape The way that the fabric falls and covers the body, usually in loose folds.

haute couture Literally “elite sewing,” the haute couture house is based in Paris and is a member of the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture. Garments are bespoke, fitted directly to the client, and made by seamstresses from the drawings or ideas of the chief designer before being embellished, for example, with embroidery or beadwork.

hip-hop From roots in mid-1970s New York, hip-hop began to reach the mainstream during the 1980s, with its music, a combination of DJs and MCs, and an uncompromising urban street style. Aspirational dressing, in the form of elite sportswear brands and high-end designers, has become a key part of the look.

jersey fabric A material with a knitted appearance that has an elasticity and stretch to it, enabling it to both drape and cling to the body. Originally made of wool, various fibers, including cotton, silk, and synthetic, are used today in its manufacture.

Lycra A synthetic fiber made from polyurethane that brings elasticity and therefore tight fit to clothes, particularly sportswear and underwear. It is woven or knitted in with other fibers, for example, cotton, nylon, or wool, not used alone. Spandex was developed during the Second World War in an attempt to find an alternative to rubber. Lycra was the brand name given to Spandex by DuPont and was commercially manufactured from 1962.

pattern cutting The pattern cutter creates the pattern (or template) based on a drawing or a garment that enables it to be further reproduced and look exactly the same. The pattern can then be modified to achieve various sizing and types of fit.

silhouette The overall shape that clothes give the body, as if, for example, seen in a black-and-white outline, which helps to determine how the visual aesthetic of fashions change.

vintage Generally perceived to be clothing more than twenty years old. As such, clothing will often be secondhand but representative of and immediately recognizable as fashion that originated from a particular decade of the twentieth century.

TEXTILES

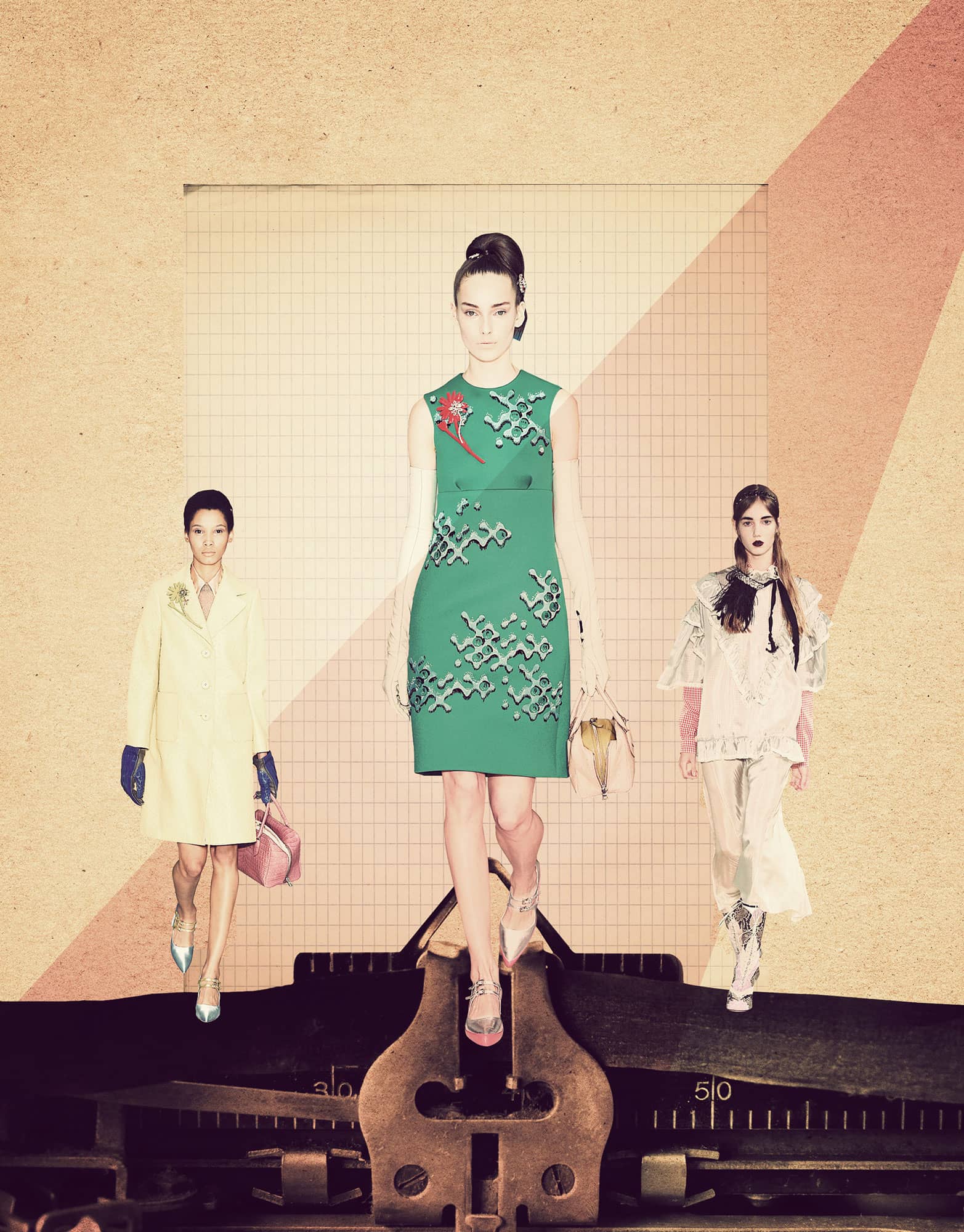

The designer’s choice of textile, or fabric, is fundamental to how the clothing will turn out. Indeed, the work of some designers has been very much informed by the textile selected. For instance, the draping and clinging properties of jersey have been used prodigiously by designers such as Claire McCardell, Donna Karan, and Azzedine Alaïa. The desired silhouette is achieved through the particular use of specific textiles. Color and pattern, as well as the weight, density, and flexibility of the material all help determine the outcome of a design. Increasingly, textile design is at the cutting edge of technology. Companies such as Jakob Schlaepfer, textile designers for fashion houses including Marc Jacobs, Prada, and Alexander McQueen, work with engineers and scientists to produce innovative, futuristic fabrics that use technology such as optoelectronics. Designers can also visit trade fairs such as Première Vision Fabrics, where textile manufacturers exhibit their collections, working on a cycle 18 months ahead of when the clothes will be shown on the runway. Innovations in textiles have often informed the direction of fashion, from cotton and muslin for the early nineteenth-century neoclassical silhouette, crêpe de Chine for the 1930s bias cut dress, and to Lycra for modern sportswear.

3-SECOND SKETCH

The textile is the place where art and science meet to push the boundaries of 2D design and forge 3D fashion.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

A textile altered while already on the runway was Alexander McQueen’s spray-painted dress from his spring/summer 1999 collection. A simple white dress with an underskirt of white tulle was spray-painted black and yellow by two robots while worn by a model on a revolving circular platform. The theater of the runway show fused both the futuristic and the artistic elements prevalent in textile design today, and created a seminal moment for McQueen.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

CLAIRE MCCARDELL

1905–58

Designer and pioneer of casual sportswear for women

AZZEDINE ALAÏA

1940–

Designer nicknamed the “King of Cling”

DONNA KARAN

1948–

New York designer famed for creating clothing for professional working women

EXPERT

Alison Toplis

Using a flat piece of cloth, a designer can cling, drape, or create whatever they desire, as mastered by Ala,ïa in this figure-hugging creation.

ART

Fashion and visual art are both aesthetic media. Yet fashion’s commercialism, mutability, and associations with femininity, are often pitted against the more autonomous, intellectual, and masculine sphere of art. Nevertheless, the fashion and art worlds have continually intersected. Between 1910 and 1930, the artist and designer Sonia Delaunay pursued her signature style of geometric and coloristic abstraction called “simultanism” in the paintings, textiles, and fashions she created. She marketed her dynamic, enveloping “simultaneous dresses” as artworks, rather than transient fashions. Yves Saint Laurent’s 1965 shift dresses, which featured the linear color-blocking of Piet Mondrian’s paintings, presented a literal transposition of fine art into fashion, as the designer wanted his collection to be imbued with the artist’s stark simplicity. During the 1990s and 2000s, Alexander McQueen’s and Hussein Chalayan’s fashion shows resembled performance art as both designers showed that the design and presentation of clothes could be as subversive as fine art. More recently, several artists have collaborated with major fashion brands. In 2012, for example, Louis Vuitton created a collection with Yayoi Kusama, with the artist’s signature bold spot patterns featuring on both the clothes and the in-store decoration.

3-SECOND SKETCH

In recent years big fashion brands have become a presence in the art world through their sponsorship of international art fairs, exhibitions, and museums.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

Is fashion a type of art? Since the 1960s, the art college rather than technical school training of prominent fashion designers has produced diverse collections that express individual creativity, and reinforce the notion that clothing is a form of artistic self-expression. Further, the complex techniques required to make haute couture especially, also denote artistic skill. Additionally, fashion’s presence in museums and galleries, spaces originally consecrated to fine art, imbues it with the latter’s aura of permanence and gravitas.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

PIET MONDRIAN

1872–1944

Artist

SONIA DELAUNAY

1885–1971

Artist and designer

YAYOI KUSAMA

1929–

Artist who produced a collection with Louis Vuitton

HUSSEIN CHALAYAN

1970–

Fashion designer

EXPERT

Katerina Pantelides

Saint Laurent’s Mondrian dress was a literal expression of fine art’s influence on fashion.

MOVIES

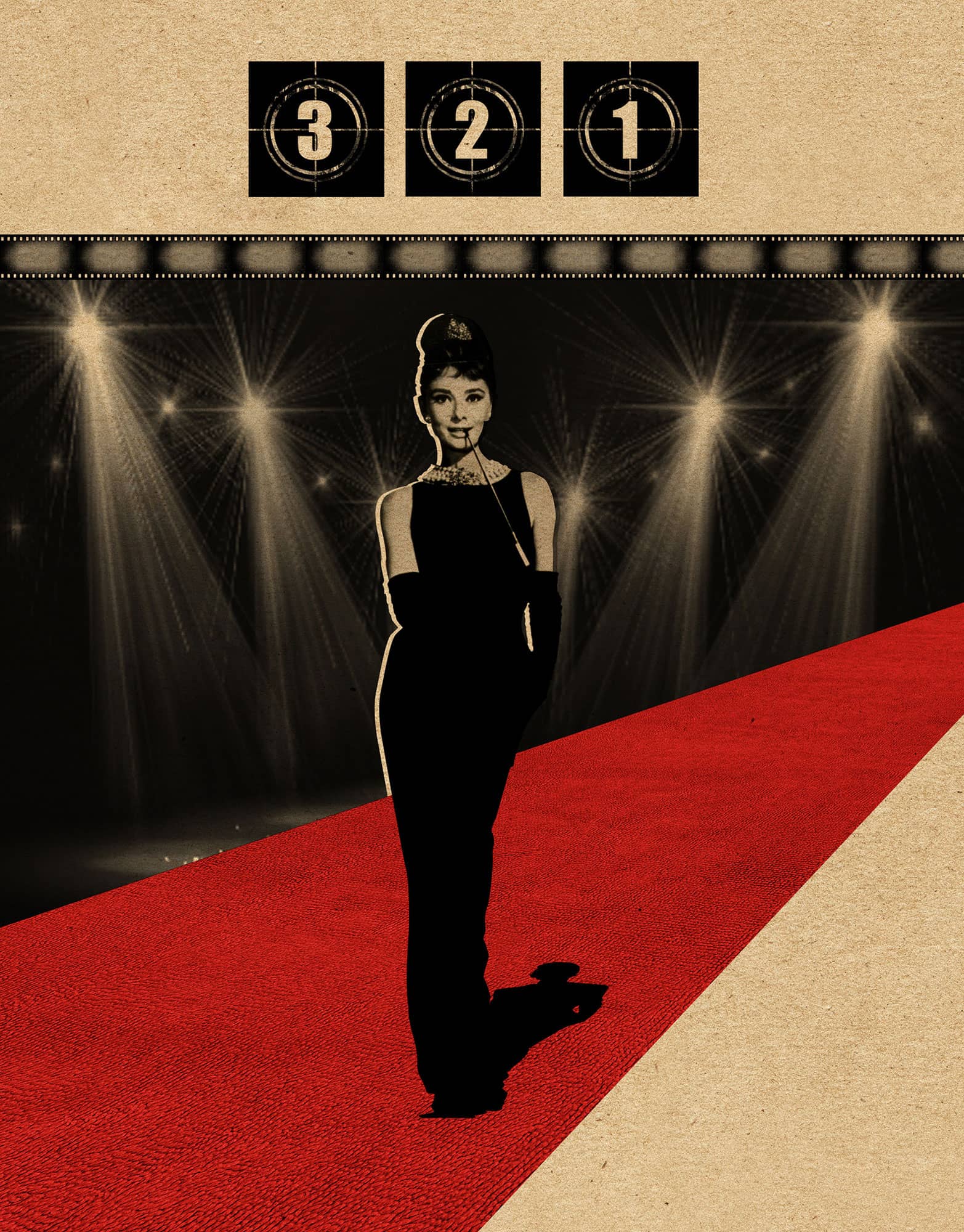

As well as defining a character’s personality and status, movie costume creates narrative and emotional resonance. For the audience, costume helps to construct the movie’s milieu and aesthetic. From its earliest days, movies have been an ideal medium to display fashions, and inevitably, to affect fashion itself. Hollywood dominated from the 1920s, with chain stores selling movie-star-inspired styles to eager fans. As color film stock emerged, fashion shows also became a favored plot device in movies such as The Women (1939) as a way of displaying glamorous designs and allowing the audience to dream. Costume designers helped to create the stars’ style—Joan Crawford was known for wearing the big-shouldered suits designed by Adrian. Fashion designers also lent their skills to big productions, keen to project their work to a captive audience, Givenchy’s costumes for Audrey Hepburn being a prime example. Such collaborations underline the interconnections between fashion and movies, with magazines still referencing Hepburn’s iconic look from Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961). More recently, fashion brands have recognized the movie’s power to espouse their seasonal message—with digital media providing an ideal platform to disseminate short, arty films to a huge audience, for example, Autumn de Wilde’s witty series for Prada in 2015.

3-SECOND SKETCH

Movies bring style to a global audience, from long leather coats in The Matrix (1999) to cheongsams in In The Mood for Love (2000).

3-MINUTE DETAILING

Movie costume instantly transports the viewer to another time and place. Historical styles, such as Milena Canonero’s designs for Marie Antoinette (2006) inspired soft pastels and rococo frills in fashion magazines. Equally, movie stars are important assets to fashion brands, with actors fronting advertising campaigns, and the red carpet becoming a runway show displaying the latest styles.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

EDITH HEAD

1897–1981

Dominated Hollywood design for decades, including designing costumes for many of Alfred Hitchcock’s movies

ADRIAN ADOLPH GREENBERG

1903–59

Known simply as “Adrian,” his hugely successful work on mid-twentieth-century Hollywood movies led to his own fashion line

MILENA CANONERO

1946–

Costume designer whose work is based on meticulous research and attention to detail

EXPERT

Rebecca Arnold

Iconic movie costumes translate into mainstream fashions, and provide inspirations for millions of viewers.

SPORT

From sportswear giants including Australia’s Rip Curl, America’s Nike, and Germany’s Adidas to niche brands such as Japanese label A Bathing Ape, sportswear dominates contemporary fashion. As dress codes gradually became more relaxed in the late twentieth century, sportswear infiltrated everyday wardrobes. In addition, sportswear is one of high fashion’s major references in recent years; for example, Alexander Wang’s 2015 collections used sneaker detailing as a decorative element on clingy dresses. Sports stars have long been fashion influencers—in the 1920s, French tennis player Suzanne Lenglen sparked a trend for shorter skirts, while more recently footballer David Beckham has featured heavily in men’s style magazines, inspiring multiple grooming and style trends. From the 1930s, sport stars have fronted clothing ranges and given visibility to the fit, athletic physique that has dominated since then. Sport’s influence is therefore doubly significant—affecting not just the way people dress, but also the way they think about their bodies. While America is known for having the most sportswear-inspired fashion designers—tarting with Claire McCardell in the 1930s—it is also home to hip-hop, whose stars from Snoop Dogg to Pharell Williams have ensured sportswear remains globally significant.

3-SECOND SKETCH

From sneakers to hoodies, sportswear-inspired fashion dominates the way people dress globally.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

Sportswear brands’ collaborations with fashion designers underline the symbiotic relationship between the two genres. Japanese brand Sacai’s designs for Nike unite high fashion with sportswear, and bring street style credibility and a larger audience to the designer. Smaller, one-off collaborations include Adidas’ with Brazilian label The Farm Company, which used the latter’s signature bright prints to create a vibrant reinvention of Adidas’ famous triple stripe designs.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

JEAN RENÉ LACOSTE

1904–96

Tennis player, who turned his nickname “the crocodile” into a logo that is still used by the Lacoste brand

CLAIRE MCCARDELL

1905–58

Designer, whose relaxed yet smart, sporty styles crystallized New York’s fashion style in the 1930s

PHILIP HAMPSON KNIGHT

1938–

In 1964, he cofounded the sportswear label that would become Nike Inc., one of the world’s most influential brands

EXPERT

Rebecca Arnold

From active sportswear to high fashion—sport is one of the biggest influences on what we wear every day.

ANDROGYNY

Androgyny is one of fashion’s most persistent recurring themes and aesthetics, with its potent collision of traditional ideas of masculinity and femininity constructing an entirely separate aesthetic founded on modernity and ambiguity. The flapper girls of the 1920s are widely considered to be sartorial androgyny’s first and most visible advocates, promoting flattened breasts, eradicated waistlines, and short cropped hair as a decade-defining ideal of beauty and sexuality. This boyish silhouette coincided with young women being afforded new social and sexual freedoms. The 1930s saw Coco Chanel eroticize and legitimize menswear elements such as tailoring and pants as sartorial symbols of feminine power and strength. Androgyny’s reemergence in the 1960s and 70s was similarly catalyzed by the influence of feminism and the sexual liberation movement. Yves Saint Laurent lent femininity a modern appeal with the iconic “Le Smoking” tuxedo suit of 1966. Musicians such as Marc Bolan and Mick Jagger glamorized the feminization of menswear with their long hair, makeup, and layers of jewelry. Fashion’s acknowledgment of the increasing fluidity of gender definitions has extended to the twenty-first-century runway, reflected through the use of transgender and gender ambiguous models.

3-SECOND SKETCH

A powerful fusion of masculinity and femininity, androgyny reverses, subverts, and eradicates stereotypical gender-specific aesthetic boundaries in order to express identity, sexuality, beauty, and modernity.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

The late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have seen androgyny return to the fore of mainstream fashion, with designers challenging traditional gender roles and stereotypes. In 1985, designer Jean Paul Gaultier playfully subverted and erased existing boundaries by creating skirts for men, while the minimalistic aesthetic of the 1990s provided a backdrop to the unisex approach of designers such as Helmut Lang, Comme des Garçons, and Calvin Klein.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

MARLENE DIETRICH

1901–92

Actress whose eroticized interpretations of menswear in the 1930 movies Morocco and The Blue Angel sparked controversy

YVES SAINT LAURENT

1936–2008

Designer who revolutionized women’s fashion with the “Le Smoking” tuxedo trouser suit

EXPERT

Julia Rea

From flappers and movie stars to rockers such as Marc Bolan, fashion’s relationship with androgyny is both enduring and complex.

EROTICISM

Fashion’s preoccupation with eroticism is unsurprising given its overlaps with the qualities central to the very nature of fashion itself: desire, pleasure, seduction, and powerful visual appeal. Close links to self-image and identity inevitably transforms fashion into a vehicle for sexual expression, while the tactile appeal of clothing being worn directly against the skin possesses a more explicit erotic potential. The aspirational value embedded in certain fashion objects can also possess a near-fetishistic quality akin to sexual desire, with consumers seeking validation and gratification through the acquiring of desirable products. Similarly, designers and photographers look to eroticize elements in order to communicate their visions of fashion and femininity, whether amplifying and objectifying the female form, or subverting traditional notions of sexuality. The femme fatale aesthetic of Hedi Slimane’s designs for Saint Laurent, for example—all thigh-grazing leather, ripped, sheer fabric, and navel-grazing necklines—recalls the dark glamor of fashion photographers Guy Bourdin and Helmut Newton, both grounded in a hedonistic vision of assertive 1970s erotica. Conversely, Jean Paul Gaultier’s hyper-camp corseted showgirls, sequin-clad sailors, and bondage-inspired lingerie plays with the stereotypes and mutability of erotic identity.

3-SECOND SKETCH

Echoing fashion’s potential for seduction and pleasure, eroticism is employed to project fantasies that promote or subvert contemporary ideals of desirability and suggest uninhibited alternative identities.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

The notion of fashion’s “shifting erogenous zones,” a phrase coined by dress historian James Laver, is deeply rooted in both clothing’s close proximity to the body and changing and often culturally-specific ideals of the female form. From Vionnet’s 1930s backless dresses to McQueen’s influential low-slung 1996 “bumster” pants, fashion’s conscious emphasis of specific body regions continually creates new sartorial and visual sites of fantasy and eroticism.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

AZZEDINE ALAÏA

1940–

Designer whose figure-hugging sheath dresses underpinned the erotically assertive aesthetic of the 1980s

JEAN PAUL GAULTIER

1952–

Designer whose playful subversion of sexuality and eroticism is visible through his championing of underwear-as-outerwear, in particular his iconic cone-breasted corsets

EXPERT

Julia Rea

Fashion both amplifies and subverts ideas of eroticism to create fantasy and meaning.

NOSTALGIA

The fashion industry is defined by its preoccupation with “the new” and its fundamentally ephemeral nature yet, paradoxically, it continually looks to the past for inspiration and validation. As with art, music, and movies, fashion’s relationship with nostalgia has gained a renewed momentum in the twenty-first century. In an era characterized by fast-paced technology and cultural sanitization, designers have increasingly been drawn to nostalgic aesthetics in order to recreate the sensation of “the new” and reconstruct a romanticized vision of a past rich in meaning, narrative, and authenticity. The designs and advertising imagery of Miuccia Prada and Marc Jacobs, for example, are often filtered through a lens of nostalgia, harking back to lost ideals of glamor and recalling the styles of previous decades in order to infuse both the designs and brand identity with authenticity, while avoiding overtly reverential reproduction by updating these aesthetics with touches of modernity. Wholly new and innovative ideas have become a rarity within fashion design, with historical elements continually being revived and blended together in order to create fresh interpretations and new relevance, whether offering a rose-tinted perspective on a lost, idealized age or becoming tinged with a sense of irony.

3-SECOND SKETCH

Fashion’s relationship with nostalgia is complex and contradictory, presenting an interplay between past and present that simultaneously romanticizes and reinterprets the past while maintaining its desire for the new.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

The cultural tendency to fetishize the past is visible through the vogue for secondhand or vintage clothing, which accelerated during the 1980s. Rejecting high fashion’s often stylized and artificial recycling of historical elements, this type of clothing is often employed as a means of authentic sartorial self-expression, as well as providing an affordable alternative to commercial fashions.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

CHRISTIAN DIOR

1905–57

Couturier whose signature hourglass silhouette of 1947 displayed a nostalgia for prewar notions of femininity

MARC JACOBS

1963–

Designer whose designs and dreamlike advertising imagery create a soft-focus vision of femininity grounded in nostalgic influences

EXPERT

Julia Rea

Past fashions are continually revived and reinterpreted by designers, blending nostalgia with a modern perspective.