FROM COUTURE TO MAIN STREET

FROM COUTURE TO MAIN STREET

GLOSSARY

atelier The workshop or studio of a designer and where couture garments are made.

bespoke A garment made to order, specifically for a certain customer, and using that customer’s precise measurements for fitting the garment. The process will usually involve several fittings to ensure a perfect fit and finish.

capsule collection When a limited supply of garments, usually a collaboration between a fashion store and designer or celebrity, is released as a collection. It can also be a few key items of clothing by the same designer that can be used in various permutations to achieve different looks and be added to with more seasonal pieces.

fast fashion Around since the 1960s, but getting increasingly faster with advances in technology, this is the ability of retailers to respond quickly to new trends and styles on the runway, and today also on social media, and reproduce these in clothing for their customers in as short a time as possible. Such clothing is low-cost and is likely to be disposed of once the trend has run its course.

hip-hop From roots in mid-1970s New York, hip-hop began to reach the mainstream during the 1980s, with its music, a combination of DJs and MCs, and an uncompromising urban street style. Aspirational dressing, in the form of elite sportswear brands and high-end designers, has become a key part of the look.

petites mains Translated as “little hands,” these are the skilled artisans who work on the couture garment under the guidance of the designer.

Mod A shortening of “Modernist,” Mods emerged in the late 1950s and early 1960s and sought to demonstrate good taste and the “less is more” ethos of sharp, “cool” dressing based on Italian style. Subsequent revivals of the style have led to a caricature “Mod” style emerging.

slow fashion A movement working toward sustainable fashion and raising awareness of the ecological and social impact of the production of clothing within a global context. With its opposition to mass-produced, “fast,” and cheap clothing it seeks to find alternatives not so reliant on seasonal trends, including clothing already in circulation, for example, secondhand or upcycled pieces.

sweatshop A factory or workshop where manual workers are employed for long hours with low pay and under poor conditions, sometimes dangerously, with very few workers’ rights. Local laws may also have been violated, for instance, the use of child labor or disregarding minimum wage pay levels, with workers exploited to produce cheap goods for manufacturers, usually to sell to the West.

Teddy Boy A youth movement that emerged post-Second World War, for the newly defined teenager, Teddy Boys first appeared in working-class south London. The look required head-to-toe dressing and drew inspiration from tailoring harking back to the Edwardian era, a style then being produced on Savile Row. Longer length jackets, flamboyant vests, and velvet trim were popular, partly as a reaction to postwar austerity, mixed with American influences such as the cowboy’s “maverick” tie.

three-piece suit A coat or jacket, vest, and pants or skirt made from the same material throughout and worn together as one outfit, a style which has evolved from its origins in the 1660s.

upcycling The creative reuse of discarded or unwanted clothing and/or textiles, making something new, and perhaps better than the original.

vintage Generally perceived to be clothing more than twenty years old. As such, clothing will often be secondhand but representative and immediately recognizable as fashion that originated from a particular decade of the twentieth century.

HAUTE COUTURE

According to French law, clothes are only deemed to be haute couture if they are approved by the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture. This legislative organization ensures that couture houses possess a Paris-based workshop, which employs at least fifteen full-time members of staff, present daywear and formal-wear collections biannually before the press, and create bespoke garments that are directly fitted to clients’ bodies. The clothes are made with a high degree of hand finish by petites mains, talented seamstresses who are affiliated to a couture house. Afterward, the embellishmentof garments is typically outsourced to specialist Parisian ateliers, for example, the embroidery workshop Lesage. The first couture house, belonging to Charles Frederick Worth, opened in 1858, and today there are about fifteen couture houses in Paris, including Chanel, Christian Dior, and Givenchy. Haute couture collections are shown to smaller, more exclusive audiences than ready-to-wear, and continue to emphasize craftsmanship and spectacle. However, in the past three decades, couturiers have presented subversive visions of luxury, in collections with overt political and sociological references. Indeed, fashion most approximates art in couture collections, because bespoke production enables the fullest expression of a designer’s creativity.

3-SECOND SKETCH

Haute couture translates as “elite sewing,” and is the most exclusive branch of fashion, because its custom-made garments sometimes require more than 700 hours of labor.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

Factors including the drastic price increase of haute couture after the Second World War and the popularity of ready-to-wear fashion in the subsequent decades, threatened to drive the couture industry into obscurity. However, detailed media coverage of couture presentations and the prominence of custom-made, intricately embellished garments worn by celebrities at events such as the Academy Awards, have played important roles in reengaging public interest in haute couture.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

CHARLES FREDERICK WORTH

1825–95

Couturier who established the first couture house in 1858 in Paris

EXPERT

Katerina Pantelides

Christian Dior regarded haute couture as a collaboration between the couturier’s ideas, the petites mains’ industry and the model’s talents.

SAVILE ROW

A street in London’s Mayfair area, Savile Row has become synonymous with names such as Gieves & Hawkes, Henry Poole & Co., Hardy Amies, and Anderson & Sheppard. They sum up a particular type of men’s tailoring based around the bespoke or made-to-measure suit, a technique that has changed little since the nineteenth century. The suit is made for an individual on an exclusive basis, often with input from the customer. The customer is measured by hand, the pattern is cut by hand, and then the garment is made up in and around the Row, with the process taking around fifty-two hours. The look epitomizes the English gentleman, whether in tweed or pinstripe, and has been worn by royalty, politicians, and movie stars. Henry Poole, who took over a military tailoring business from his father in 1846, was the first to operate from Savile Row, developing the trade to include sporting and civilian clothing. The reinvention of the tradition by Nutters of Savile Row from 1969, and the “New Establishment” tailors Richard James and Ozwald Boateng in the 1990s, has led to a renewed interest in the bespoke suit and English style. The Savile Row Bespoke Association was established in 2004 to promote and protect their trade and name, and their traditions of quality and craftsmanship.

3-SECOND SKETCH

The Savile Row style means elegant, bespoke classical men’s tailoring, although also sometimes quietly surprising with flamboyant linings or hidden messages, worn by the great and the good.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

Henry Poole was a Victorian master of advertising and product placement, using the celebrities of his day, including the Prince of Wales and sportsmen such as the jockey Jem Mason, to wear his clothes. To be “Pooled” from head to foot was used as a description of his clients. His store was also elaborately decorated for special occasions, drawing in crowds and setting the template for retail promotion.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

HENRY POOLE

1814–76

Founder of Savile Row and “tailor to all the crowned heads in the world of any note”

HARDY AMIES

1909–2003

Produced tailored clothes for both men and women, including Queen Elizabeth II

OZWALD BOATENG

1967–

The first tailor to stage a runway show in Paris, in 1994

EXPERT

Alison Toplis

From male peacocks to conservative suit wearers, all have been outfitted by Savile Row tailors.

READY-TO-WEAR

Ready-to-wear clothing encompasses the vast majority of clothing bought and worn today: that is, clothing bought from store stock in a standardized size without prefitting. The clothing can be mass produced in factories or manufactured on a smaller scale, but if it is not made with a particular customer in mind, rather to enter the surplus stock of a retailer, it is ready-to-wear. Over the course of the twentieth century, consumers have increasingly been buying clothing not for durability or function but for fashion, so-called “fast” fashion. Ideas from the couture runways are reinterpreted by ready-to-wear designers and manufactured quickly to reach mass markets. Technological developments have increased the speed of the design process so it is no longer only reliant on the biannual couture shows for inspiration, but takes trends from the street and, today, social media. Information gleaned directly from store sales also influences the design process and how retailers order and reorder clothing. Clothing retailers now get new garments to consumers every few weeks and garments can be of a limited run to sell out and encourage buying. “Designer” ready-to-wear offers a broader customer base for couture houses, giving the essence of the designer, although at a more basic level and with a more affordable price tag.

3-SECOND SKETCH

Off-the-peg is common parlance, denoting hanging on a peg ready for sale, as clothes were displayed before coat hangers came into use in the twentieth century.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

Ready-to-wear clothing has been called various derogatory terms, such as slop or shoddy, literally the waste fibers of old clothes reused for ready-to-wear clothing in the nineteenth century, and was looked down on as cheap, poorly made, and ill-fitting. Today, ready-to-wear is celebrated, from Topshop dresses on the red carpet to the coverage of fashion houses producing ready-to-wear lines alongside their couture collections.

EXPERT

Alison Toplis

A garment bought ready to put on and wear is the mainstay of the fashion business, from couture houses to budget brands.

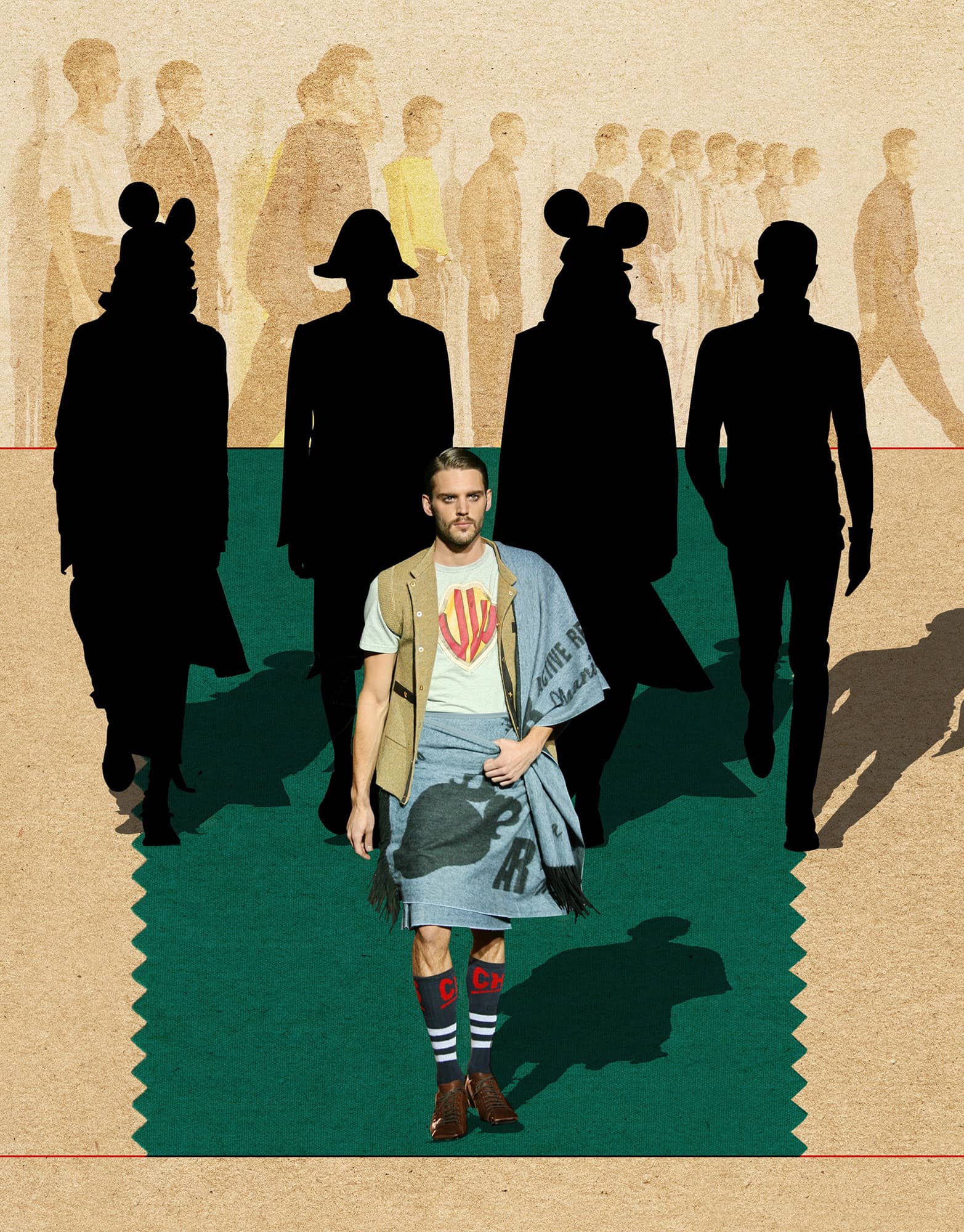

MENSWEAR

Tailoring, based around the three-piece suit, has been the foundation of menswear for the last 300 years. However, since the 1960s, designers specializing in men’s fashion, rather than traditional tailoring, have emerged. Italian designers, for instance, Nino Cerruti in the 1960s and Giorgio Armani in the 1970s and 1980s, have been particularly influential in menswear, playing on the seductive elegance of the Italian look in contrast to English tradition. Although menswear has been seen as less exciting and more staid than women’s fashion, it has absorbed many diverse influences over the last fifty years, from subcultural and street styles including Teddy Boys, Mods, and hip-hop, to sportswear. Designers such as Vivienne Westwood and Alexander McQueen have pushed gender stereotypes by placing men in skirts, and the profile of men’s fashion has also shifted, with Hedi Slimane at Dior Homme one of the originators of the influential skinny silhouette for the suit in the first decade of the twenty-first century—a youthful and androgynous look. The reinvigoration of traditional masculine brands such as Louis Vuitton, Dunhill, and Burberry, with designers such as Christopher Bailey at the last, has given a new focus to menswear, which now vies with womenswear in significance at the runway shows.

3-SECOND SKETCH

The great masculine renunciation of fashion, the sober dark suit, has never quite taken complete hold and the flamboyant peacock frequently rears his head.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

The first runway show of menswear was shown by Savile Row inhabitant Sir Hardy Amies in 1961. Called “Man,” the ready-to-wear collection was shown at the Savoy Hotel, London, with around a dozen models walking to prerecorded music, the designer coming out at the end to take a bow—the first time music and applause had been used and taken in this way. Amies thus set the template for future runway shows.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

NINO CERRUTI

1930–

Designer who opened his first boutique in Paris in 1967

GIORGIO ARMANI

1934–

A protégé of Cerruti, forming his own company in 1975

EXPERT

Alison Toplis

Although men in skirts have not yet become a mainstream look, menswear designers continue to push the boundaries of the masculine silhouette in other ways.

FRAGRANCES, BEAUTY LINES & ACCESSORIES

The fragrances, beauty lines, and accessories ranges launched by designer brands function as both a lucrative secondary source of income and an effective method of constructing a coherent brand image and identity. Perfumes, makeup, handbags, scarves, jewelry, and other items associated with a design house possess a unique appeal as luxury status objects marketed at a more affordable price point, merging aspiration and accessibility while, simultaneously, heightening the commercial and cultural visibility of a brand. The seductive exclusivity implied by these products signifies an authoritative notion of taste and quality while the significantly weighted value of a designer’s name lends the consumer cultural and stylistic “capital”: perfume bottles become objets d’art and handbags are transformed into ubiquitous icons of design. Luxury brands such as Ralph Lauren and Missoni have expanded their design empires to incorporate homewares and accessories such as candles, translating their distinctive design signatures into a comprehensive lifestyle philosophy. By licensing these products, designers are able to both reach a broader consumer market and financially sustain global businesses that may otherwise be reliant on the more limited scope of the affluent haute couture or ready-to-wear customer.

3-SECOND SKETCH

Aspirational objects in their own right, fragrances, beauty products, and accessories provide an osmotic extension of a designer brand’s sartorial and cultural cachet at a more accessible price point.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

Packaging remains central to the aspirational appeal of a designer’s beauty and perfume lines, visually capturing the essence of a brand’s identity and aesthetic. The modernist design of Chanel’s lipsticks and perfume bottles are both instantly recognizable and indisputably iconic. Similarly, Jean Paul Gaultier’s Classique perfume bottle comes in various editions, each displaying a Gaultier design signature upon its corseted form, from nautical stripes to the iconic conical-breasted Madonna corset.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

PAUL POIRET

1879–1944

The first couturier to develop his own fragrance, Rosine, in 1911, the same year he launched a home décor range

COCO CHANEL

1883–1971

Her iconic signature fragrance Chanel No. 5, introduced in 1921, remains the world’s most successful fragrance

EXPERT

Julia Rea

Designer accessories occasionally attain iconic status, being positioned as cultural artifacts with an enduring investment appeal.

MAIN STREET

Chain stores, stores with multiple branches, have developed over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, some from market stalls, and others from department stores. In competition with boutiques, independent stores, and department stores, the chain store will stock a selection of ready-to-wear fashion, usually aimed at a particular type or range of consumers, at relatively cheap prices. Stores dealing specifically in fashion were a postwar development, catering to the spending power of the new “teenager,” particularly during the 1960s. In the late twentieth century, the Italian retailer Benetton and the American retailer The Gap found huge international success, the latter offering a version of the American preppy look. After a hiatus, the market has been reinvigorated by new names such as Mango and Zara from Spain and collaborations with designers and models. The sector is increasingly diverse in both style and price point with chains such as J. Crew and Reiss offering high-end clothing and a particular look, in contrast to budget chains such as Primark and Target, which provide cheap basics and their own take on fashion. Today, styles influenced by the runway, and sometimes designed by fashion house stars, are within financial and geographical reach of the majority of consumers.

3-SECOND SKETCH

Branching out firstly into mail order, now online shopping, the chain store caters for everyone and every pocket.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

With its origin in arcades and covered bazaars, the first enclosed shopping mall was opened in 1956, near Minneapolis. A natural home for fashion chain stores, the mall proliferated across the West in the late twentieth century, particularly in suburban areas. The mall is now seen across all continents, bringing Western clothing brands to all corners of the world and homogeny to fashion consumption. Whether this should be entirely welcomed is another question.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

DONALD FISHER & DORIS FISHER

1928–2009 & 1932–

Cofounders of US chain The Gap

LUCIANO BENETTON

1935–

Founder of Italian chain Benetton

PHILIP GREEN

1952–

Chairman of the Arcadia Group, which includes Topshop

EXPERT

Alison Toplis

For those on a budget, main street is the place where fashion dreams are transformed into garment reality.

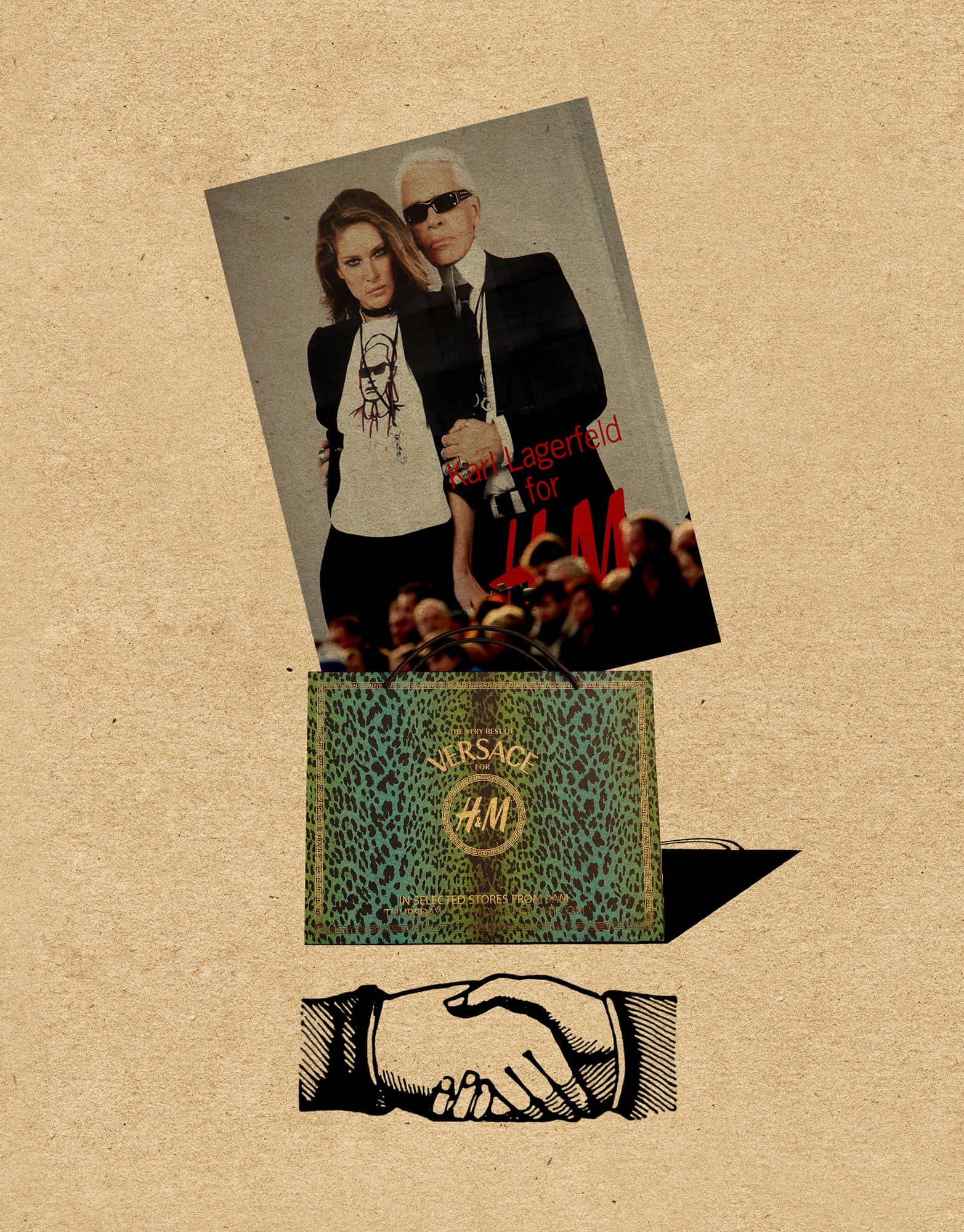

COLLABORATIONS

Collaborations between high fashion designers and main street retailers have become hugely successful in the last decade, launching the term “high-low” (or “high end—low end”). American mega-retailer Target first launched its limited-edition collaborations in 2003 with a capsule collection by Isaac Mizrahi. In the ensuing years, Target’s series of collaborations with such fashion powerhouses as Missoni, Peter Pilotto, and Joseph Altuzarra regularly sell out hours after being released. Likewise, Swedish fast-fashion company H&M, which began its designer collaborations in 2004 with Karl Lagerfeld, has had phenomenal success with them. Its list of collaborators includes such notable figures as Alexander Wang, Alber Elbaz of Lanvin, and Versace. In some cases, the H&M collaboration launch days have been so successful that customers have had to wait hours just to get into the stores. These high-low collaborations have brought high fashion to a new consumer base. Previously, these brands would have been inaccessible, if not wholly unknown, to the average person. Of course, the garments produced for these collaborations are quite different from their luxury counterparts. Design elements are modified to meet the production requirements of fast-fashion factories and the price tag requirement of fast-fashion consumers.

3-SECOND SKETCH

Collaborations between high fashion designers and main street retailers have democratized the luxury industry and opened the fashion world up to the everyday consumer.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

Collaborations have not always been successful. In 1984, American designer Halston collaborated with mainstream retailer J.C. Penney to produce a line called Halston III. When it debuted, some of Halston’s most important high-end retailers, including Bergdorf Goodman, dropped Halston’s main line. They felt he had tarnished the exclusivity of his brand. Sadly, J.C. Penney consumers were not interested in purchasing cheap Halstons either. Soon after the failure, Halston was ousted from his own company.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHIES

ROY HALSTON FROWICK

1932–90

Fashion designer known for his minimalist designs

KARL LAGERFELD

1933–

Creative Director for Chanel, Fendi and his eponymous label

ISAAC MIZRAHI

1961–

Fashion designer and television personality

EXPERT

Emma McClendon

Collaborations have changed the hierarchy of the fashion industry. Today, anyone can own a piece of “designer” clothing.

ETHICAL ISSUES

Ethical issues in fashion today are broad and diverse, from how textiles are produced, including the environmental impact on the surrounding landscape and the effects of globalization, to how the factories that weave the cloth and make the clothes operate. The move of manufacturing from the West to Asia has brought consumers cheap “fast” fashion, but at the expense of low wages and poor working conditions for the factory workers, including the use of child labor. The collapse of the Rana Plaza factory building near Dhaka in Bangladesh in 2013, which killed more than a thousand people, shocked Western commentators with the conditions that the employees worked in making garments for Western retailers. While there is now more awareness, particularly of building safety, there seem to have been few changes in Asian workers’ conditions or the mainstream attitudes of Western consumers. However, the “slow fashion” movement has been gaining momentum, promoting sustainable clothing over mass-consumption, for example, wearing secondhand or vintage clothing. In the United States alone, anywhere between eleven and fifteen million tons of clothing is thrown away every year, which suggests recycling or upcycling are increasingly important choices.

3-SECOND SKETCH

As they have come under increasing scrutiny from consumers and the media, fashion companies have adopted ethical policies to create a responsible foundation on which to build their collections.

3-MINUTE DETAILING

Animal welfare also falls under the umbrella of ethical issues, with designers such as Stella McCartney refusing to work with fur and leather in her company. Sustainability is also part of her ethos, and she has continued to win numerous fashion awards while still heading an “honest” and “responsible” company. She has supported PETA, the animal welfare organization, whose campaigns include the famous “I’d Rather Go Naked than Wear Fur” series.

3-SECOND BIOGRAPHY

STELLA MCCARTNEY

1971–

Designer, famous for her ethical stance

EXPERT

Alison Toplis

The hidden costs of a garment, whether environmental or ethical, are an increasingly important issue for consumers.