CHAPTER 4:

THE MEDIEVAL MAZE

Labyrinths in cathedrals, churches, castles, and chateaux

“Au milieu du labyrinth de cette église.”

—Jules Gailhabaud, 1858

In chapter three we looked at the spiritual maze, and here we continue the sacred theme as we consider a time when labyrinths and mazes were absorbed into the Christian cannon. While we will be looking at mainly Christian examples and those in manuscripts, we will also explore their uses in some other more secular contexts, such as time keeping in ancient China.

We saw in chapter two how the early Christians used the mosaic labyrinth in Algeria, with the centerpiece palindrome on “Sancta Eclesia” (shown here). This particular labyrinth has been interpreted as a depiction of the “Civitas Dei” (City of God) surrounded by the “Civitas Mundi” (City of the World), as described by Saint Augustine in his early fifth-century work De Civitate Dei. There was a second “Algerian Christian Labyrinth,” in Tigzirt, which has not survived, but was written about by the Roman poet Prudentius in Contra Symmachum.

On the path to perdition, the labyrinth represented not the city of God, but a world of sin and heresy. In finding their way out, the faithful would find redemption. These “good” and “bad” labyrinths were the early forerunners of a new order, whereby the Roman four quarters design would disappear and new shapes were realized in churches and in manuscripts, with icons that eventually replaced Theseus and the Minotaur. Labyrinths appeared in ancient manuscripts as illustrations and metaphors used to illustrate philosophical concepts and possibly as calendar references. In some medieval manuscripts, the labyrinth is associated with tables that note the dates of the Easter cycle, echoing a line from a Servius codex that says, “The start of April drew me from this labyrinth.” Perhaps the labyrinthine pathways helped with visualizing the cycle of time. And then, perhaps, as the Sawards observe, the labyrinth symbol was merely present to illustrate the complexity of the subject matter.

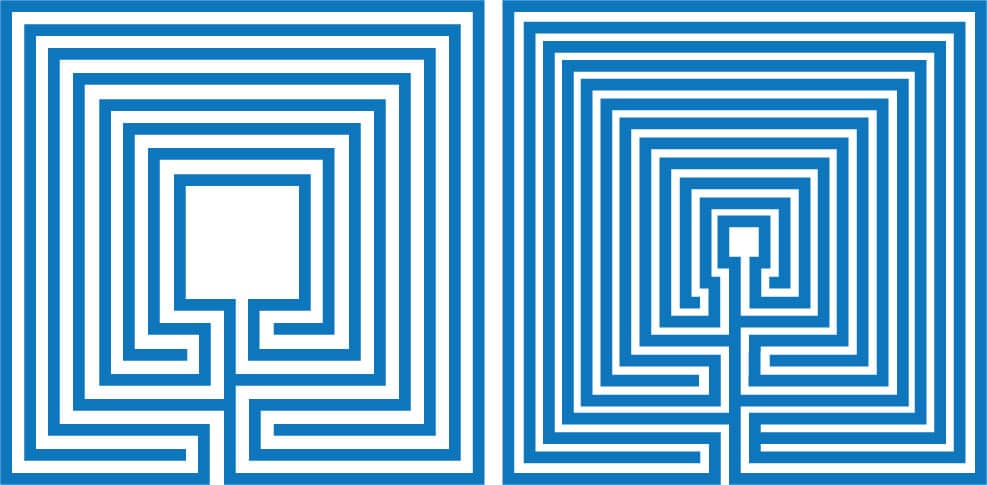

The “Otfrid Labyrinth,” in a manuscript of the Books of Gospels, which dates from 871 and is attributed to the German Monk Otfrid of Weissenburg. With eleven (rather than seven) circuits, this labyrinth is viewed as a precursor to the famous medieval example at Chartres Cathedral in France, which we will explore later in this chapter. In historical terms, it is a vital link between the classical and medieval labyrinth designs (see Fig.1 for an illustration of Otfrid and Fig.2 for a comparison of the two types).

Fig. 1: Illustration of the “Otfrid Labyrinth.” The original was found in a manuscript of the Books of Gospels, which dates from 871 and is attributed to the German monk Otfrid of Weissenburg.

Fig. 2: Comparison of the classical (left) and medieval (right) designs.

The great Mappa Mundi, a medieval map of the world, at England’s Hereford Cathedral, dating from 1280, features a labyrinth that half-fills the island of Crete, inscribed as Labarintus id est domus Dealli (Labyrinth, the house of Daedalus) (Fig. 3). Created by Richard of Haldingham and Lafford, and drawn on a single sheet of vellum measuring just over 5 by 4 feet (1.5 by 1.2 m), this is not a map as we would know it today, but rather a collection of people, stories, and places. A three-dimensional scan of the document shows a tiny pinhole at the center of the labyrinth, which tells us it was drawn with a tool for drawing circles such as a compass.

Fig. 3: The labyrinth that half-fills the island of Crete inscribed as, “Labarintus id est domus Dealli,” found on the Mappa Mundi. © The Dean and Chapter of Hereford Cathedral and the Hereford Mappa Mundi Trust.

By the twelfth century CE, the eleven-path four-axis labyrinth was dominant across Christian Europe, and it became the medieval design. For over two thousand years, the pagan design had survived unchanged. And then, over just a few hundred years, it moved from manuscripts to ecclesiastical buildings and developed more diverse and complex forms, accompanied by Christian symbolism.

In 1510 the Austrian cartographer Johannes Stabius published a work entitled Concerning Mazes, which included three interesting designs (shown here). Stabius, appointed royal historiographer by the Emperor Maximilian, collaborated with the artist Albrecht Durer on a world map published in 1515. He also invented the heart-shaped world map projection, popularized by Johannes Werner.

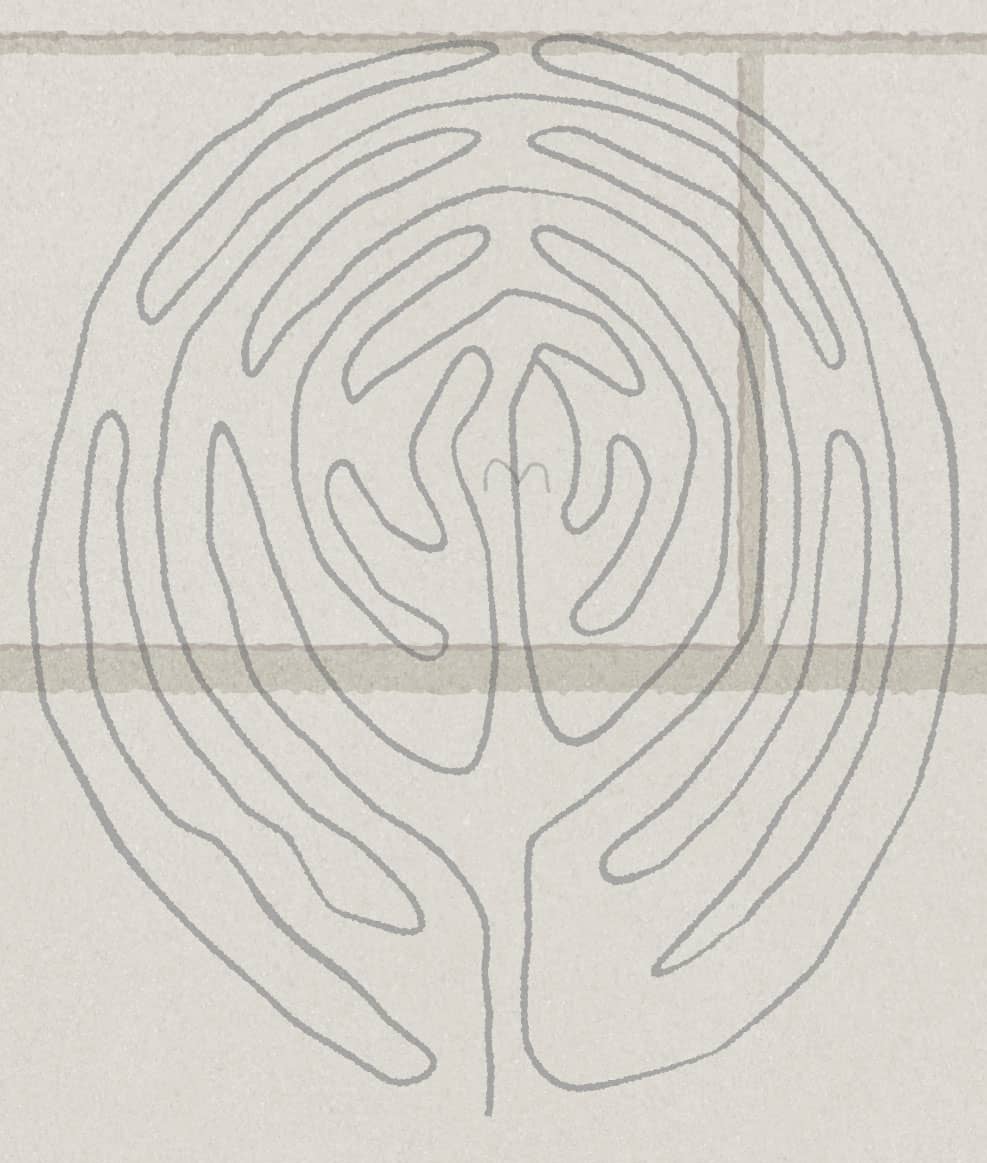

The development of the Christian medieval maze was concentrated in Europe, with the most impressive examples in Italy and France and others found in Poland, Britain, and Scandinavia. The Italian labyrinths tended to be smaller than the French, although that should not detract from their beauty. Labyrinths were laid on church floors and carved into church walls. Some early examples still feature the Cretan myth, although the Christian narrative is clearly coming through. An example found on a wall at Lucca Cathedral in Italy, just over 11/2 feet (45 cm) in diameter, did feature the Theseus and the Minotaur at the center, worn away by tracing fingers over the years (shown here). A late twelfth-century-carved artifact, another “finger labyrinth,” from the convent church of San Pietro de Conflentu in Pontermoli, Italy, has the monogram of Christ at its center. He is not killing a monster, but, instead, redeeming those who have sinned.

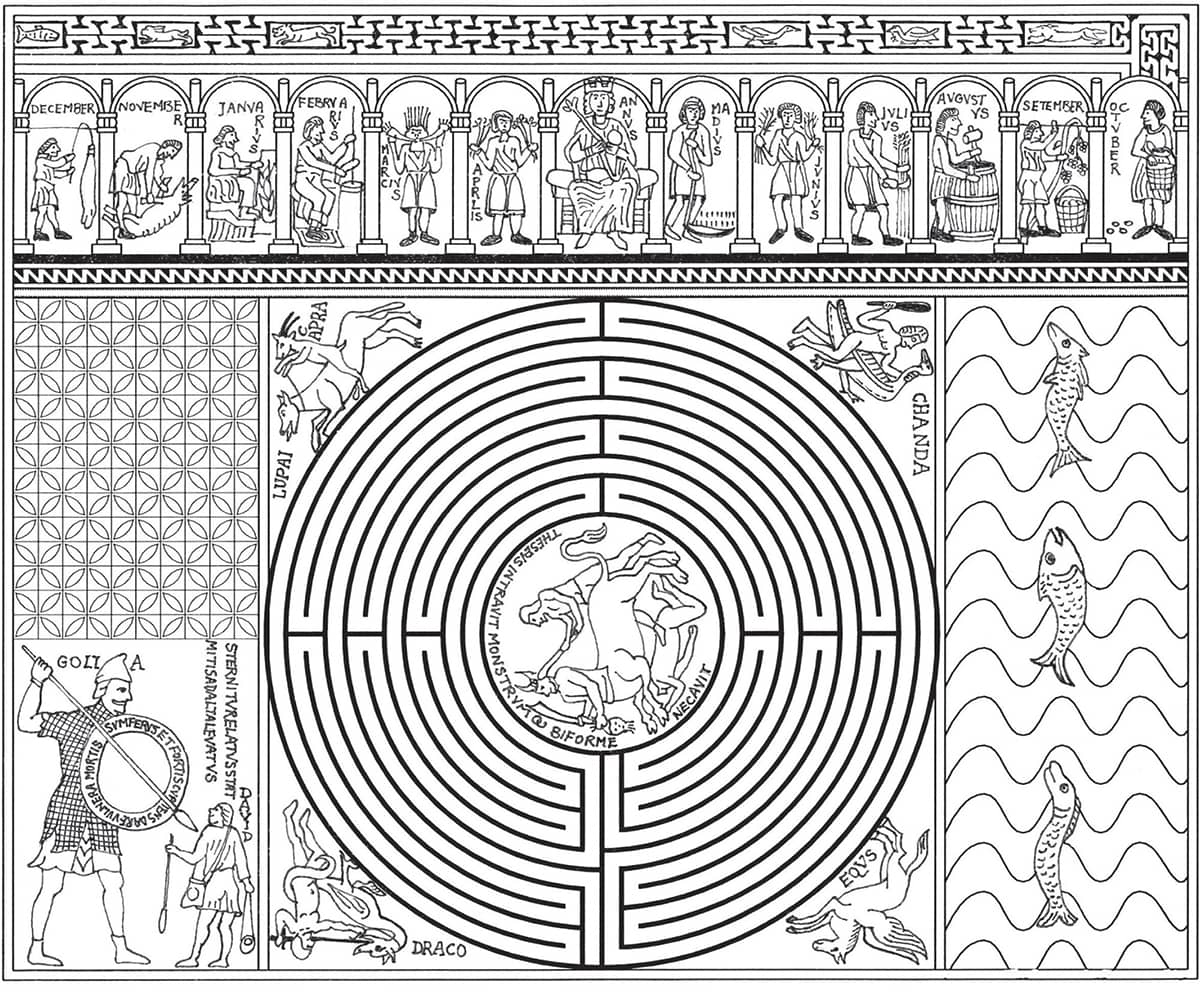

The symbolism of Old Testament stories, such as the struggle between David and Goliath, also feature in labyrinths. Take the extraordinary pavement in the San Michele Maggiore Basilica in Pavia, Italy, laid in 1100 on the floor of the church choir. From a sixteenth-century drawing reproduced by Saward (shown here), we can see not only the fight between good and evil, but also a frieze depicting Annus and the twelve months of the year. We have already noted the connection between labyrinthine iconography and the calendar in manuscripts, but at the time these would not necessarily be seen by ordinary folk. Perhaps the medieval maze in a church setting had an educational as well as a moral purpose. Some, however, would have been simply decorative, such as the unique gilded roof-boss (one of 1,200) in Saint Mary Redcliffe Church, Bristol, England, dating from the 1390s. It has been suggested this was possibly an architect’s signet.

Jeff Saward claims the true flowering of the labyrinth during the medieval period took place in northern France during a wave of cathedral construction and a quest for ever-grander monuments. Maze maestro Adrian Fisher believes the catalyst for the innovations of the gothic cathedrals was probably contact with the Arab world during the Crusades. Robert Ferré tells us that the Crusades succeeded in introducing “barbaric” Europe to culture and learning from the Islamic world. The exact purpose of labyrinths in these settings, while clearly not only contemplative, has been the subject of much debate. In chapter eight we will consider what engaging with labyrinths and mazes today can do for us from a psychological and even physiological perspective. For medieval times, we can look to the evidence and we can use our imagination. A number of different uses are suggested including symbolic games, dances, and pilgrimages.

Design by the Austrian cartographer Johannes Stabius, published in a 1510 work entitled Concerning Mazes.

Design by the Austrian cartographer Johannes Stabius, published in a 1510 work entitled Concerning Mazes.

Design by the Austrian cartographer Johannes Stabius, published in a 1510 work entitled Concerning Mazes.

Illustration of the labyrinth found on a wall at Lucca Cathedral in Italy.

The extraordinary pavement in the San Michele Maggiore Basilica in Pavia, Italy, laid in 1100 on the floor of the church choir. Illustration: Jeff Saward/Labyrinthos Photo Library.

Dancing the labyrinth path was a ritual for the canons at Auxerre Cathedral in France, performed each Easter Sunday from 1396 until 1538. A ball called a pilota was thrown back and forth while the canons chanted the Victimae Paschali Laudes during their ring-dance, accompanied by organ music. The pilota is said to have represented the dance of the sun throughout the year. Afterwards, everyone was treated to a meal at the chapter house, paid for by the most recently appointed canon, who also had to provide the ball. We know that games at some cathedrals disturbed the cannons and their worshippers. As early as 1311, the Council of Vienna forbade the dances and the games, and much later, in 1538, a decree of the Parliament of Paris re-enforced the ban. In 1690 the “Auxerre Labyrinth” was destroyed, because the game, and possibly the ritual itself, had become a distraction, and, in 1779, Canon Jacquemart destroyed the labyrinth at Rheims (constructed between 1287 and 1311) for similar reasons (see Fig. 4 for a comparison of the medieval and “Rheims Labyrinth” designs).

Fig. 4: Comparison of the Rheims (left) and medieval (right) labyrinth designs.

On a more devotional note, perhaps pilgrims traced the labyrinth path, possibly on their knees, as they reached the final stage of a pilgrimage. Or perhaps they did not. Known from the late eighteenth century as the “Jerusalem mile” or the Chemins de Jerusalem, walking the labyrinth may have taken the place of a pilgrimage to the Levant, but we cannot be certain of that. At the center of the Notre Dame in Rochefort, Belgium, we find a depiction of the celestial city of Jerusalem, representing a new heaven and earth.

Probably the most well-known cathedral labyrinth is at Chartres, France, and was most likely constructed between 1215 and 1221 when the cathedral was rebuilt after a fire in 1194. Measuring just over 42 feet (13 m) across (shown here). Divided into four quadrants, the walk to the center and back is around one-third of a mile. This labyrinth is the oldest surviving full-size medieval Christian example. A common myth about Chartres is that if you folded down the great rose window above the cathedral’s west door, it would fit exactly over the labyrinth. Robert Ferré claims that the diameter of the “Chartres Labyrinth” is one-millionth the polar diameter of planet earth. He also observes that this labyrinth would have 114 complete “lunations” (ornamentation forming a halo around the outside of the labyrinth), but for those missing to make room for the entrance. He then notes that the Koran is divided into 114 chapters called “surahs,” that the first is known as “The Opening,” and that he considers these similarities to be noncoincidental. Many have surmised about the so-called Chartres “lunations” (also called “scallops” or “cogs”). Another labyrinth, of a Chartres-type circular design, was at Sens Cathedral (shown here). This was destroyed in 1769.

Originally, there was a bronze plaque in the center of the “Chartres Labyrinth,” probably featuring the Cretan legend. In 1792 this was removed and melted down for cannon during the French Revolution. Not all labyrinth centers depicted legends, Christian or otherwise. The center plaque at Amiens Cathedral, which is all that remains of the original labyrinth created in 1288, depicts Bishop Evrard de Fouilloy, who commissioned the building of the cathedral, and the architects. See page 68 for an illustration of the “Amiens Labyrinth” that was destroyed in 1825 and credited to Jules Gailhabaud, which was published in 1858 and originally reproduced by W.H. Matthews. This labyrinth was subsequently restored in 1894 (shown here).

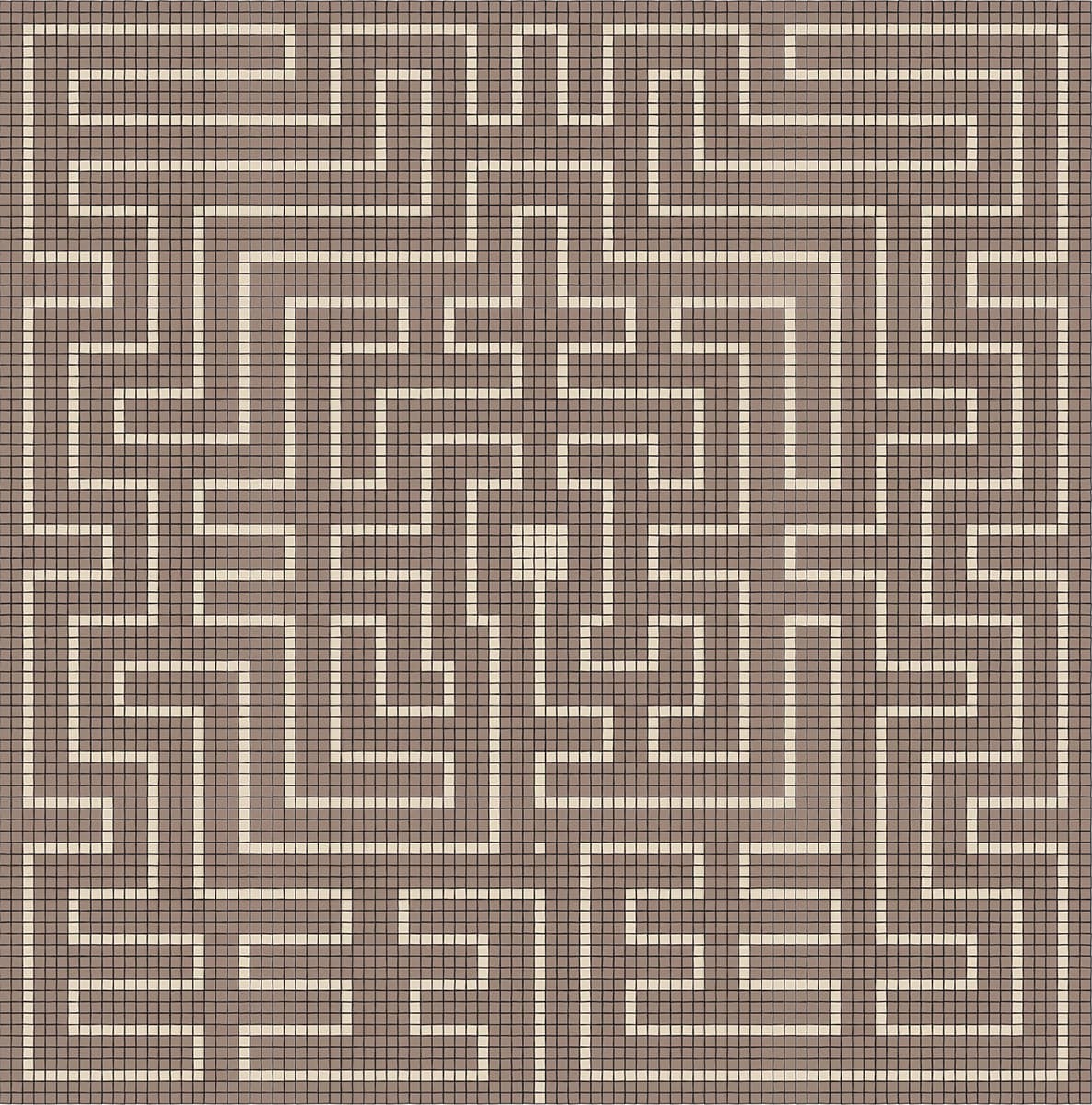

Two quite unusual church mazes that unfortunately no longer exist were at Poitiers Cathedral and the Abbey of Saint Bertin, in Saint-Omer, France. Evidence of the former is a graffito scratched on the wall (see Fig.4 for an interpretation). The path is confusing and appears not to lead to a center but, instead, returns to the outside. We do not know if a labyrinth existed on the floor of the nave. The latter, at Saint-Omer, was constructed in 1350 with 2,401 square paving stones (shown here). Nearly 36 feet (11 m) wide, the meandering design appears to be faulty at first glance, although it is not. In 1843 a half-sized replica of the original that had been destroyed in the French Revolution was installed in the cathedral Notre-Dame in Saint-Omer.

Created in 1533 as part of a sixteenth-century revival and clearly inspired by the original installation at Saint-Omer, we find a labyrinth in the Pacification Room in the town hall of Ghent, Belgium. Unlike Saint-Omer, this one is rectangular, with a different alignment and measuring 43 by 36 feet (13 by 11 m). But like Saint-Omer, it features a cross in the design. Increasingly, from this time, labyrinths were being built in secular settings. We find another example in the treasury in the Castel Saint Angelo in Rome dated 1546. In this instance, the labyrinth provided symbolic protection of the revenues and archives stored here. This was the beginning of a wider interest in labyrinths and mazes in different settings, such as parks and gardens, though, as with the convolutions of the form itself, we will see that the garden maze has medieval roots. These are examined in chapter six—I did say in the beginning that this curious history does not run in a straight line!

Fig. 4: Illustration (above and below) of the graffito on the wall of Poitiers Cathedral, France. Described by Matthews, neither the original nor the version in his book function as labyrinths. Our interpretation of the originator’s intent produces an eccentric but functioning labyrinth.

Illustration of the labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral in France.

Illustration of the labyrinth at Sens Cathdral in France (destroyed in 1769).

Illustration of the labyrinth at Amiens Cathdral, France, destroyed in 1825. Credited to Jules Gailhabaud, published in 1858, and originally reproduced by W.H. Matthews.

Illustration of the restored labyrinth at Amiens Cathedral, France.

Illustration of the labyrinth at St. Omer Cathedral, France.

Jacob Cats’ Dool-hof der Kalver-Liefde (Labyrinth of Calf-Love) depicts Cupid leading a lady into the complex pathways of young love. This would appear to be the original illustration on which Goossen van Vreeswyk based his Hermetick Labyrinth drawing (shown here).