CHAPTER 8:

THE MAZE EXPERIENCE

Tools for personal development, solving puzzles, and having fun

“It is safer to search in the maze than to remain in a cheeseless situation.”

—Dr. Spencer Johnson, 1998

What is it like to experience labyrinths and mazes? We tend to see ourselves as either logically, or creatively, inclined, and this may well influence how we approach our interaction with these intriguing artifacts. In this context some may find it useful to employ the left-brain, right-brain theory. The basic premise is that the left side of the brain governs our ability to be logical, whereas the right side is more in touch with our creativity, and that people tend to be “left-brained” or “right-brained.” While this theory is not proven scientifically, it is still popular and can, if you like, provide a way of distinguishing between your experience of a maze puzzle or a labyrinthine meditation.

As I acknowledged in chapter one, it has been stated that a maze is a puzzle and a labyrinth is not. Therefore, some “left-brained” people may find it easier to engage with a puzzle, and “right-brained” people may prefer the more reflective labyrinthine experience. I also, however, recognized that mazes and labyrinths refuse to conform to any rudimentary definition. The same can be said for our brains. The distinction between our logical and creative selves is not always that clear-cut, and I would not want your experience to be limited by conventional opinion. Should a maze-walker focus solely on solving the puzzle and a labyrinth-walker not? When we encounter labyrinths and mazes, we actually use all of our brain, not just one side. So, let us not get hung up on being logical or creative, or however we (or others) like to define us. Labyrinths and mazes serve many and varied symbolic and practical functions. Surely, it is better to approach them with an open mind.

Having said we should look at this holistically, perhaps listing just a few aspects of the experience is helpful here, at least to dispel even the slightest concern about what to expect. This is not exhaustive, by any means, and the encounter can be different for everyone.

Aspects of the Experience

LABYRINTHS |

MAZES |

Opening up your imagination |

Harnessing your cognitive skills |

Following your intuition |

Honing your sense of direction |

Letting go of your troubles |

Being absorbed in the puzzle |

Taking the time to respond rather than react |

Testing reflexes and decision-making skills |

Greater connectivity with yourself and others |

Competing against yourself and others |

A sense of mystery |

A sense of disorientation |

The loosening of tension |

The rush of adrenaline |

A sense of resolve |

A sense of accomplishment |

Francesca Tatarella in Labyrinths & Mazes tells us that in 1974, at the opening of Richard Morris’ “Masonite Labyrinth” at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, the curator warned, “Persons with claustrophobia or delicate health are not advised to walk through the labyrinth.” Perhaps this particular example presented special challenges with its 10 feet (3 m)-high walls and 17.7 inch (5.4 m)-wide paths.

In 2013 Giovanni Mariotti writes in From Labyrinth to Labyrinth, “Even today the threshold of a labyrinth cannot be crossed without a slight tremor. No frisson, no labyrinth.” Thinking about the emotional and intellectual ways to experience both does help to emphasize their differences, and Robert Ferré writes about the dual nature of the different encounters in The Labyrinth Revival. A popular saying is that the point of a maze is to find its center and the point of a labyrinth is to find your center. In relation to both, it is most likely a matter of being lost and then found.

The eventual, if not immediate, benefits are also manifold. Mazes can help improve your concentration and mental dexterity. Labyrinths can create mindfulness, a heightened awareness of yourself and others, and, eventually, clarity (aha, left-brain, right-brain I hear you say!). Walking meditations are also generally acknowledged as having physiological benefits, such as lowering blood pressure, reducing incidents of anxiety and even chronic pain, and reducing insomnia. Both lead to a resolution of some sort, even if it is simply a decision to come back and do it again. The experience is different every time, and, of course, you may set out on each encounter with a different aim or focus (not forgetting that open mind!). If one day you find it all rather dispiriting, it will most likely be better next time around.

If you can, do try different examples. Australian Dr. Margaret Rainbird, who undertook a year-long “Labyrinths for Life” tour to America, Britain, and Europe in 2017, describes labyrinths as being a bit like people, “There are some that I feel an immediate emotional connection with and others where there is no chemistry at all.”2 The experience is never totally passive. A labyrinth can be contemplated, traced, drawn, painted, carved, planted, sewn, worn, walked, and danced. It can be transformative and it can leave you feeling energized and rejuvenated. American Dr. Kimberly Lowelle Saward, co-founder of Labyrinthos, writes about her insight into the modern resurgence of interest in mazes and labyrinths, and has conducted a psycho-spiritual study of labyrinth folk practices worldwide. She also writes most movingly about her personal labyrinth journey.3

Giovanni Mariotti reminds us that there were times when the labyrinth signified the place where the monster lived; times when it was considered appropriate for warding off thieves and evil spirits; and times when it represented the penitential pathway to Christian salvation. He says in labyrinths we can play the part we are drawn to, the part that best expresses our sentiment of life. The Labyrinth Society has a “365 Experience,” whereby one can encounter a labyrinth every day and contribute to a shared collection of experiences, giving, and receiving wisdom. One does not have to go to a labyrinth, as the Society has examples that can be downloaded and used.4

Apart from my suggestion about having an open mind, I have no intention of providing specific guidance on how to approach a labyrinth, as others, including The Labyrinth Society, are far more qualified to do so. Probably the most well known is the Reverend Dr. Lauren Artress, who, since placing a canvas labyrinth in the nave of Grace Cathedral in San Francisco (a permanent one is now installed), has become the de facto leader of the modern labyrinth movement. Dr. Artress, founder of Veriditas, defines the labyrinth as “a spiritual tool that has many applications in various settings. It reduces stress, quiets the mind and opens the heart. It is a walking meditation, a path of prayer, and a blue-print where psyche meets Spirit.”

Since 1999 Veriditas has been leading pilgrimages to Chartres, using trained facilitators, and has a Legacy Labyrinth Project, creating commissioned installations for families and communities that want to leave a legacy for healing and connection. Of course, it is not only the “Chartres Labyrinth” that is being replicated and used for spiritual purposes. Replicas of European stone and turf labyrinths, for example, are built and used for a variety of purposes in many locations across the world.

Armand G. Erpf, who had commissioned the 1969 Ayrton installation mentioned in chapter seven, describes the labyrinth as an “aesthetic experience, a symbol in a world so caught up with scientific rationalism it doesn’t know where it’s going. You can’t get to the center of a maze by going straight for it. You have to be indirect. The way to attain something is to go away from it. The maze is a spiritual truth.”

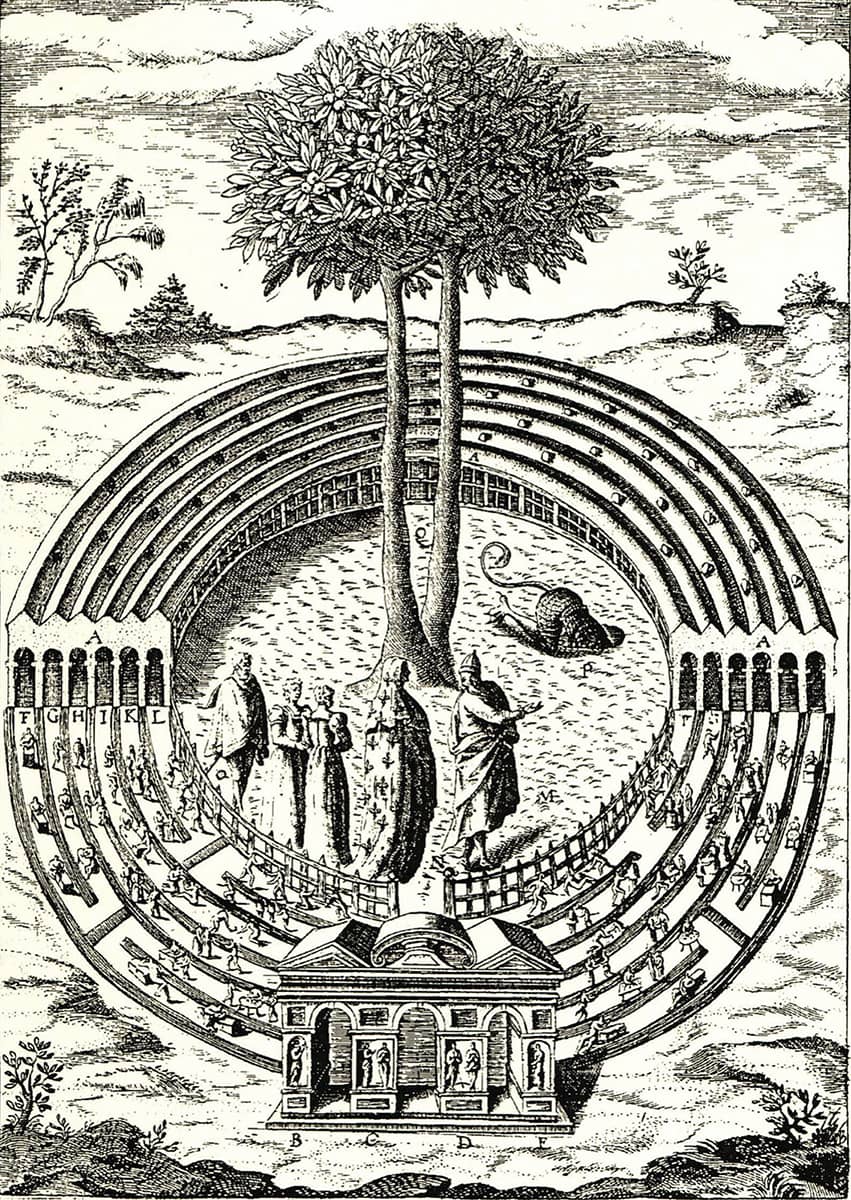

Dedicated to Henri III of France in 1609, a poem entitled “Civitas Veri sive Morum” (“The City of Truth or Ethics,” an allegorical recasting of Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics) by Bartolomeo Del Bene, takes the author’s patroness, Marguerite, Duchess of Savoy, on a spiritual journey through the utopian City of Truth’s five portals. The body is transformed into the city of truth, site of the entire moral cosmos, entered by the gates of the senses. The work features emblematic engravings (not by Del Bene) including a Labyrinthos, in quo vitia duo, Auaritia & Restrictio Magnificentiae (Labyrinth in which the two vices, Avarice and Parsimony, are magnificent) (shown here; see here for an interpretation—featuring greedy persons, lenders, gamblers and thieves).

We saw in chapter three how labyrinths and mazes have, in the past, been given a metaphysical or sacred status that takes us beyond the natural world. Dr. Artress has written books on Walking the Sacred Path and The Sacred Path Companion, and calls the labyrinth “a Grail in that it connects individual destiny to service in the world.” This may give us a clue as to why the modern revival shows no signs of abating. Christian faith or not, it seems that people, individually and communally, are turning to this archetype for direction in this troubled world of ours.

The Labyrinthos, in quo vitia duo, Auaritia & Restrictio Magnificentiae from “Civitas Veri sive Morum” (“The City of Truth or Ethics”) by Bartolomeo Del Bene, 1609.

A. Labyrinthus, in quo vitia duo, Auaritia & Restrictio Magnificentiae

Labyrinth in which the two vices, Avarice and Meanness, are magnificent

B. Effigies Senectutis impositae uni de parastatis siue antis ianuae

Statues of Old Age imposed on the pillars of the gates or doorways

C. Statuae Pauoris & Paupertatis

Statues of Paucity and Poverty

D. Famis & Frigus

Starvation and Cold

E. Sitis

You

F. Primus Labyrinthi circulus in quo statuae tenacium, quod primum genus Auarorum est.

The first circle of the labyrinth, in which are those who cling onto things, the first kind of greedy person.

G. Alter circulus, in quo feneratores, quad alterum genus Auarorum.

The second circle, in which are lenders, another sort of greedy person.

H. Tertius circulus, in quo Lenones, tertia species Aurorum.

Third circle, in which are the procurers, the third species of greedy persons.

I. Quartus circulus, in quo aleatores, quartum Auarorum genus.

The fourth circle, in which are the gamblers, the fourth kind of greedy person.

K. Quinctus circus, in quo mendici.

Fifth circle, in which are beggars.

L. Sextus, in quo fures.

The sixth, in which are thieves.

M. Aristoteles

Aristotle

N. Regina

The queen

O. Auctor ipse operis

Author of the work

P. Auaritia ipsa, specie monstrosa

There is avarice itself, in the appearance of a monster.

Q. Arbor Liberalitatis & Magnificentiae

The tree of Liberality and Magnificence

An interpretation (above) of the Labyrinthos (opposite), an allegorical recasting of Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics.

On September 11, 2001, the labyrinth at St. John’s Episcopal Cathedral, Knoxville, became a spontaneous place of solace for hundreds of people. And on that date ten years later, David Ellis Dickerson walked a labyrinth provided by Veriditas at St. Paul’s Chapel, New York (close to The World Trade Center and the National September 11 Memorial and Museum), and wrote about his reflections. Dickerson sees the labyrinth as always being relevant, whatever happens. “It’s older than anything we face,” he says, and describes the path as giving us solidarity through space and time. “The Centennial Park Labyrinth” in Sydney, Australia, a replica of Chartres which opened in 2014, has a team of volunteers who facilitate walks including Aboriginal Elder, Aunty Ali, who says, “The labyrinth invites and welcomes people to walk the path together–it calls them to the land in oneness.”

We also looked at Navajo sand paintings in chapter three and noted that in Indo-Tibetan culture, the labyrinth can be expressed visually as a mandala. Labyrinths are often seen as belonging to the family of mandalas, which is Sanskrit for “circle.” Jill Purce writes in The Mystic Spiral that the labyrinth is “none other than a model of existence as we know it, a mandala, and a two-dimensional version of the spherical vortex.” Like labyrinths, mandalas are universal and may be used as a meditative instrument. Indigenous North American tribes used mandalas, like labyrinths, as part of their ritual practice, believing they represented the circle of life. They are used in many traditions, such as Hinduism and Buddhism, and featured in Mesoamerican society as calendars. Unlike labyrinths, mandalas generally represent the cosmos. Swiss psychologist Car Jung promoted the benefits of using mandalas to stabilize, integrate, and reorder inner life.

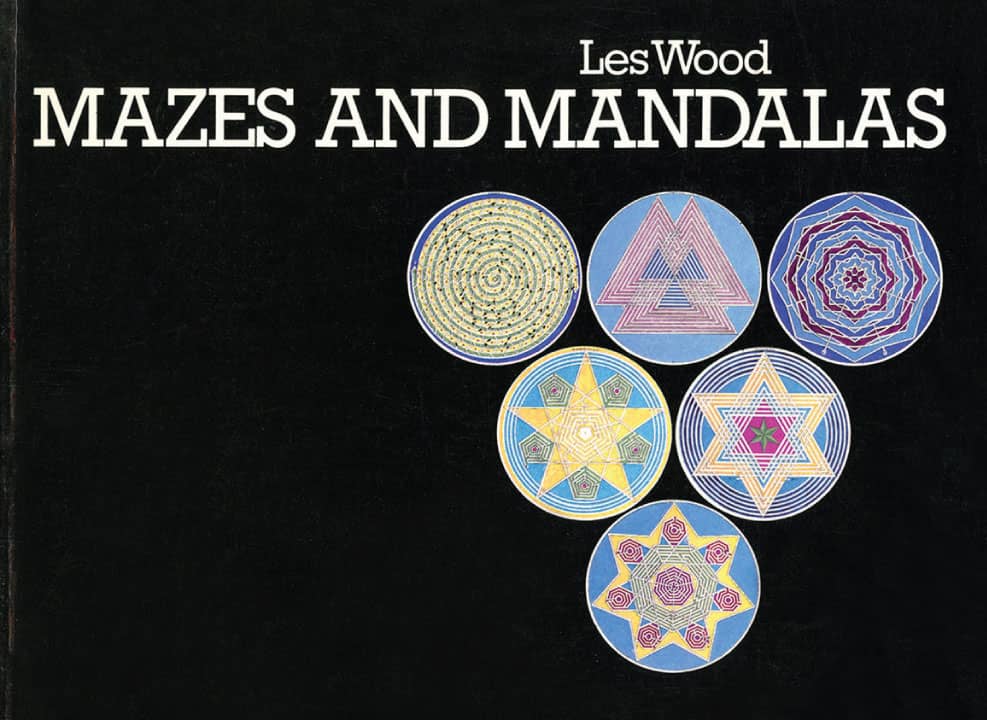

Les Wood, in his 1981 publication Mazes and Mandalas with nine mazes that combine the mandala, numerology, color therapy, and meditation, tells us that when the maze is mastered, the power of the mandala is supposedly increased (Fig. 1). He says the purpose of a mandala is to strengthen the ego, increase confidence, make one pleased with success, and make one look forward to further successes. We do not have the space here to explore more of the meaning and use of mandalas. Just to say, it has been observed that rose windows in churches and cathedrals may be seen as mandalas in themselves.

Fig. 1: Les Wood’s Mazes & Mandalas, 1981.

Before we go on to look at the experience of mazes as puzzles, let us briefly note the practice of geomancy and dowsing. The Geomancy Group describe their practice as “divining the Earth,” working with earth energies to enhance our relationship with Spirit and Place. And dowsing, which is about much more than finding water, also connects with the earth’s energies. Dowsers are interested in labyrinths. Lonegren writes that labyrinths, when walked on a regular basis, can draw primary underground water to them, and notes that the Nazcan civilization were aware of this connection (we looked at the Nazca lines in chapter three). He tells us that geomancy can be used to “tune” sacred spaces (including a labyrinth) like a musical instrument.

Ferré tells us that the first public labyrinth in North America was created at a meeting of geomancers at the Ojai Foundation in California, for the 1986 Council of the Living Earth (this does not account for labyrinths created by indigenous peoples or artistic installations, examples of which we will look at in chapter nine). He also tells us Sig Lonegren built a labyrinth at his home in Vermont that same year, and that walking the labyrinth enlarges and expands our “aura,” our energy field. He says, “I believe we are the electricity, the current that gives the labyrinth its power.”

While labyrinths are good for channeling many things and for personal development, they do not have the monopoly on being utilized for self-help purposes. The popularity of American Dr. Spenser Johnson’s 1998 bestseller Who Moved My Cheese demonstrates that mazes, as well as labyrinths, can be effective tools for dealing with life’s challenges. It is a motivational parable using a maze in which four characters look for “cheese,” a metaphor for whatever they want in life. Conversely, while it is mazes that we tend to associate with the pursuit of leisure, labyrinths can also be fun. We considered ancient labyrinthine dances earlier on, and Ferré also associates them with a game and celebration. An unexpected delight in San Francisco for Dr. Rainbird is the labyrinth at the Saint Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church, a church with colorful icons chosen for their “unified humanity,” including Mahatma Gandhi, Emily Dickinson, and Martha Graham.

Looking at the aspects of the experience listed above for our encounter with mazes (as opposed to labyrinths), the emphasis is on some sort of thrill or amusement. In 1987 Professor Giancarlo Maiorino writes about eccentricity in the Mannerist tradition, describing the Italian mazes as fancies with “dwarfs, deformities, and ragamuffins all enjoying themselves in rough games, sour music and crude laughter”—maybe not how we would express it today. He notes that in the maze we are protected and imprisoned by our own ingenuity, which has created a design of “excessive indirections.” Fisher describes the maze as the ultimate landscape artifact that one can put oneself into and interact with and says it is the element of fun, “of probing the puzzle, of a journey of discovery,” that continues to fascinate.

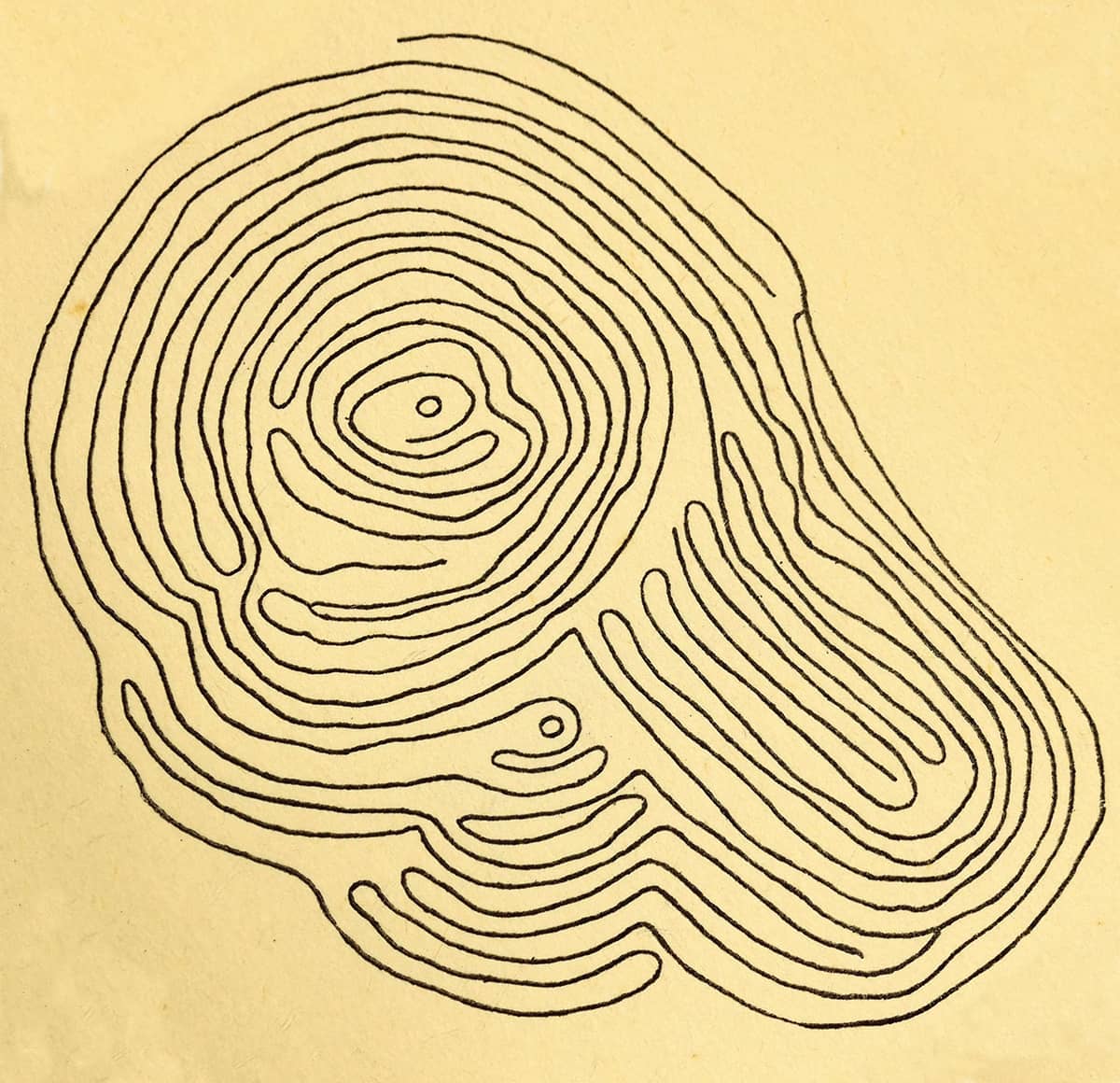

It is these excessive indirections, plus a variety of ingenious devices and tricks invented by maze makers such as Fisher, that provides the essence of the puzzle maze experience. The modern maze designers that we noted in chapter seven certainly gave solvers a run for their money. But a maze does not have to be so intricate or flash to entertain. In her 1912 book, Some Zulu Customs and Folk-Lore, L. H. Samuelson writes that African Zulus are very fond of drawing mazes on the ground (shown here). The one who draws asks someone else to find the way into the royal hut. If he fails to follow the right course, he is greeted with “Wapuka sogexe!,” meaning one is done for in the labyrinth and has to start again. Samuelson tells us that the game is a great favorite, often played for hours at a time.

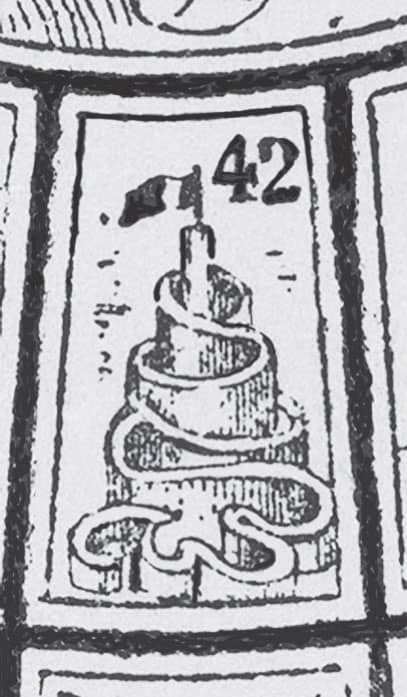

A labyrinthine board game with royal associations is the Game of the Goose, played in the sixteenth century at the court of King Philip II of Spain. Many variations have been produced since the eighteenth century, with different themes including religious and educational. Played by adults and children alike, this allegorical game is about the journey of life. It takes the players to different scenarios including prison, death, and a maze, which is always located at number 42 (see example in Fig. 2 drawn by Mexican José Guadalupe Posada). All goose games end on the number 63 square. If you win, you may start again, which is perhaps why the game is in the shap e of a spiral, as it can be never ending. I wonder if the maze always being thus located has anything to do with the selection of 42 as the answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe, and everything by Douglas Adams in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.

Fig. 2: The number 42 in a Game of the Goose, this version drawn by Mexican José Guadalupe Posada.

From L. H. Samuelson’s 1912 publication Some Zulu Customs and Folk-Lore.

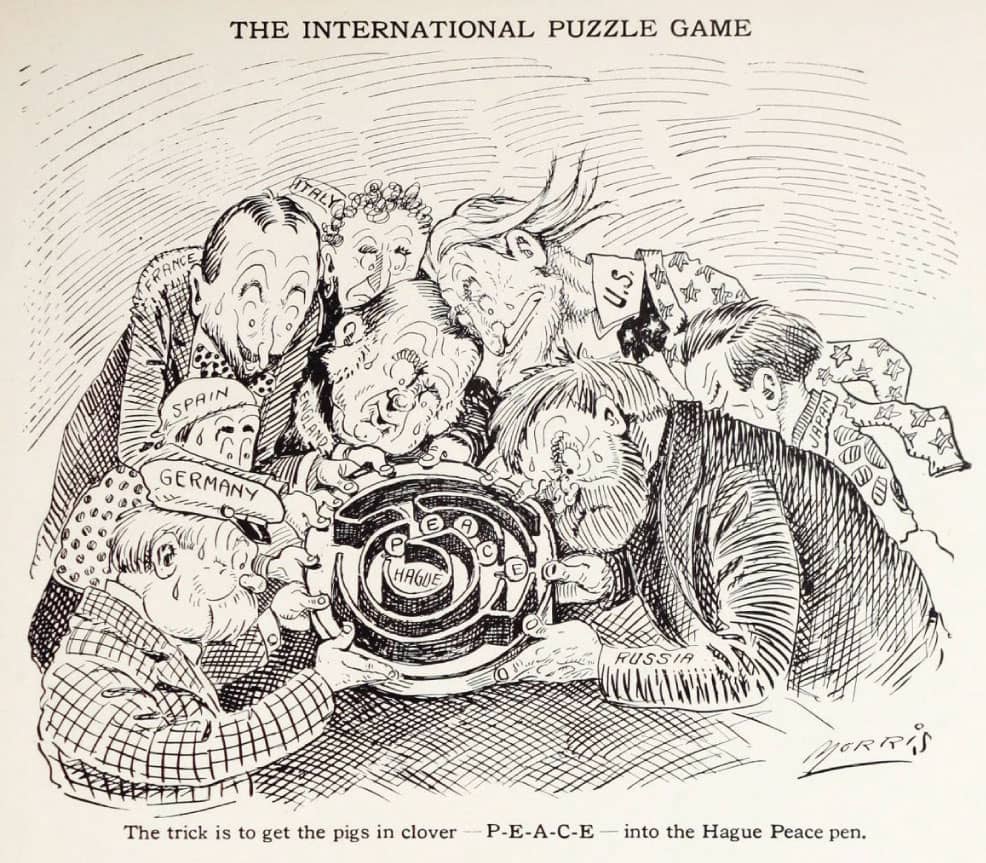

Mazes as games have taken many different forms, as we have seen here and in other chapters. In 1889 American Charles Martin Crandall invented Pigs in Clover, a hugely popular ball-in-a-maze dexterity puzzle whereby the pigs (marbles) had to be manipulated though a maze of concentric circles by the solver and held in the center (Fig. 3). Over a million sets were reportedly sold, and the game spawned many copies, as well as a patent dispute. Mark Twain featured the game in his 1896 novel The American Claimant, a humorous tale of mistaken identity and role switches.

Fig. 3: The game, Pigs in Clover. Author’s collection.

His character, Colonel Mulberry Sellers (Fig. 4), invents the game, which, according to him, “makes a strike,” and—according to the press reports he sees—“from the Atlantic to the Pacific all the populations of all the States had knocked off work to play with it, and that the business of the country had now come to a standstill by consequence; that judges, lawyers, burglars, parsons, thieves, merchants, mechanics, murderers, women, children, babies–everybody, indeed, could be seen from morning till midnight, absorbed in one deep project and purpose, and only one–to pen those pigs, work out that puzzle successfully.”

Fig. 4: Mark Twain’s Colonel Mulberry Seller, “He was constructing what seemed to be some kind of frail mechanical toy.”

See Fig. 5 for a slightly later political cartoon featuring the game. Much later, the game appears in the 2016 American science fiction television series Westworld (based on Michael Crichton’s 1973 movie). The game’s maze pattern in the television series is different to the real thing, and the pattern is featured in several episodes in different contexts. Variations of Pigs in Clover are still popular, as toys and online.

Fig. 5: The Hague Convention of 1907. Editorial cartoon by William C. Morris, c.1906–8.

In 1976 Janet Bord writes about a transparent plastic cube maze puzzle through which the player navigates a marble. Pocket puzzles have come on a long way since then; balls and cubes with running beads and lasers, money banks (solve the puzzle and get your pennies), pens, calculators, watches, and models one can create on demand with a 3-D printer. The terms used to promote these games tell us something about their appeal. For example, as brainteasers it is claimed that they enhance intellect, intelligence, dexterity, balance, hand-eye co-ordination, and wisdom. They also perplex and are hard to put down!

The subtitle of Robert Abbott’s 1990 book Mad Mazes is Intriguing Mind Twisters for Puzzle Buffs, Game Nuts and Other Smart People, which clearly reveals something about those who are attracted to this type of pastime. The puzzles in Galen Wadzinski’s The Ultimate Maze Book of 2005, mentioned in chapter seven, are described by the publisher as taking from five to ten minutes to solve, to hours. The symbol in the book to indicate the level of difficulty is a brain with varying amounts of grey matter.

On the subject of gray matter, maze games have been employed in the advancement of science over many years, for testing what has been described as the ability to create and navigate an ecocentric cognitive map of our environment. The “Morris Water Maze,” for example, invented in 1981 by Professor Richard Morris, tests spatial learning and memory in rodents. Other lab mazes include the “Barnes Maze,” the “Radial Maze,” the “Elevated Plus,” the “Elevated Zero,” and the “Y- and the T-Maze.” In 2009 American neuroscientist David Tank created a virtual lab maze in which mice navigate the open source video game Quake (the mouse wears a metal helmet and walks on the surface of a Styrofoam ball).

A ground-breaking online and virtual reality maze game called Sea Hero Quest, mooted by German neuroscientist Professor Michael Hornberger, is today being used in dementia research, measuring people’s 3-D navigational skills (one of the first lost in dementia). The game involves a sea journey taken by a son in a quest to recover the memories his father has lost to dementia. There are three sections: navigation, shooting flares to test orientation, and chasing creatures. The game is designed to be fun as well as scientifically valid, and by early 2017, over 2.7 million people had played it, with data from 193 countries. The number of people living with dementia is projected to almost triple to 135 million by 2050. The game won nine Cannes Lions at the International Festival of Creativity and has been played at the UN General Assembly.

In chapter six we met Professor Rouse Ball, who was distinctly unimpressed by the notion of the “Hampton Court Maze” as a puzzle. At his home in Cambridge, England, the Professor (a keen amateur magician and founding president of the Cambridge Pentacle Club) created his own garden maze (Fig.6). Citing French author Charles Pierre Trémaux, the professor outlines a system for walking through a maze whereby no path is traversed more than once in each direction and the maximum distance traveled amounts to twice the sum of the path lengths. In doing so, the solver must distinguish between new and old paths and nodes (a node is where two or more paths meet).

Fig. 6: The plan for Professor Rouse Ball’s garden maze at his home in Cambridge, England.

How do you do that? Like Hansel and Gretel, you use markers, but perhaps not breadcrumbs. You need two different types of marker, one for the nodes and one for paths that have been walked twice. From the entrance you take any path. If you come to a new node, leave a marker and take any new path. If you come to an old node (that you have already marked), or a dead-end and you are on a new path, then turn back. If you come to an old node and you are on an old path (one you have walked once already and marked), take a new path (if such exists) or an old one, but never go down a path more than twice. This is not the shortest route, but you will at least get to experience the whole maze.

One way of experiencing the whole maze or labyrinth is to run it. W.H. Matthews writes about a temporary maze for a 1921 English garden fête made of galvanized-wire netting supported on 6-foot (1.8 m) fir stakes and thickened with elm foliage. A sign at the entrance declared:

Beware the dreadful Minotaur

That dwells within the Maze.

The monster feasts on human gore

And bones of those he slays.

Then softly through the labyrinth creep

And rouse him not to strife.

Take one short peep, prepare to leap

And run to save your life!

I noted some of the traditional games around turf mazes in chapter five. It strikes W.H. Matthews that those mazes with no branches or dead-ends made for rather simplistic races, unless the contestants were blindfolded or “primed with a tankard or two of some jocund beverage.” Other games were played in the vicinity of turf mazes. The setting for an old strategy game called Nine Men’s Morris, mentioned by Shakespeare in A Midsummer’s Night Dream, was a labyrinthlike square design cut into the turf, chalked on floors, or even carved onto tables and seats. The aim of the game, played by two, is to make lines of three pieces (known as “mills”) and reduce the other players’ to less than three, or render them unable to play.

Shakespeare writes, “The nine men’s morris is fill’d up with mud; And the quant mazes in the wanton green, For lack of tread, are indistinguishable” (Titania in Act 2, Scene 1, lines 98–100). With a variety of names, including “Siege of Troy” and “Merrils” (jeu de merelles in French), this game may be more strongly linked with the traditional children’s game of hopscotch. In Man, Play and Games (1958), French sociologist Roger Caillois writes, “In antiquity, hopscotch was a labyrinth in which one pushed a stone.” The stone represents the soul, which is moved across the high altar of the church, represented on the ground by a series of rectangles. We know the game today as a more secular playground activity.

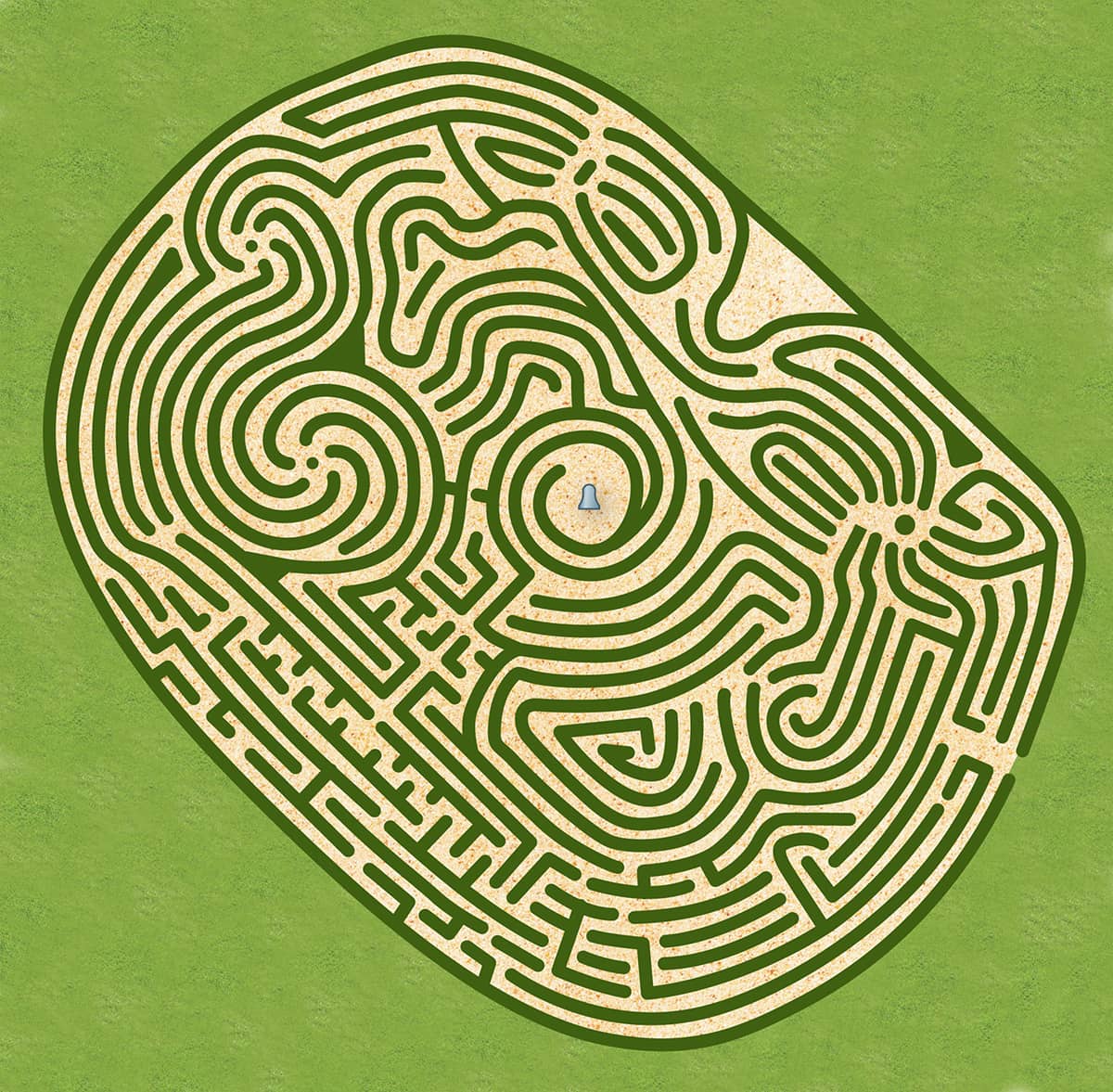

Illustration of “The Peace Maze” at Castewellen, Northern Ireland, planted in 2000. Upon solving the maze there is a bell to ring at the center. This bell is considered to be one of the most frequently rung bells in Ireland, with over half a million rings every year.

In chapter seven we considered the larger hedge and corn or maize mazes that emerged from the 1970s onward. Over the years, maze-makers created devices to provide escape routes if needed. For example, visitors to Greg Bright’s wooden maze at Pigeon Forge, Tennessee, in the 1980s, were given pennants so they could be spotted, and they could escape via a small opening if they so desired. Increasingly, maze makers have also provided entertainment en route. At Pigeon Forge’s, vast mirror mazes today, solvers can enhance their experience in different ways such as wearing 3-D glasses. Spectators can also watch the action through a two-way mirror.

As a former theatrical producer, Don Frantz decided from the beginning of his enterprise to create an “experience” for the visitors to his American maize mazes, a full “show” with music, characters and comedy. The aim was to entertain throughout, to prevent boredom and even anxiety. The first, in 1993, had eleven thousand visitors over three days (see chapter seven). There are now hundreds of unique installations across America every year, produced by many different firms and farmers. Many are interactive, with clues and QR codes, challenge apps, trivia quizzes, and exhibits. Attendants may be on hand to assist with reorientation. It is not advisable to try and break through the corn like those who did so in the past in hedge mazes. While there have been instances of visitors getting lost and calling 911, the general feedback from those who have completed a maize maze is a feeling of tremendous elation. En route, they may have experienced anxiety, confusion, and even claustrophobia, but at the end they have a great sense of accomplishment.

In this chapter I have captured something of the essence of the labyrinth and maze experience. There is so much more to explore and learn, through further reading (see Works Cited and Notes) and engaging with them where you can. In chapter ten there is a gazetteer that indicates the whereabouts of some historical and well-known examples. Before that, in the final part of our curious history, we turn to mazes in modern popular culture.