CHAPTER 9:

MAZES IN MODERN POPULAR CULTURE

Potent and versatile cultural devices

“I imagined a labyrinth of labyrinths, a maze of mazes, a twisting, turning, ever-widening labyrinth that contained both past and future and somehow implied the stars.”

—Jorge Luis Borges, 1941

Giovanni Mariotti writes that the labyrinth has a metamorphic, versatile, variegated history, and that it has “entertained relationships with poets, philosophers, mathematicians, creators of enigmas, choreographers, painters, designers. It has served as a kaleidoscope of meanings, with different configurations for each age.” He considers the myriad of forms for the labyrinth, as a noun and as an adjective. Labyrinths and mazes have served as potent and versatile cultural devices over generations, and, as we noted in chapter eight, are employed today in vital scientific research. We just have room in this chapter to note a selection of interesting and curious examples from one or two modern cultural cannons.

In 2005 English author Karen Armstrong observes in A Short History of Myth that myths need to be retold differently, as our circumstances change in order to bring out their timeless truth. At the time she was introducing a series of contemporary novellas, retelling a number of myths in modern genres (Russian author Viktor Pelevin contributed The Helmet of Horror, a retelling of the Cretan myth in which the labyrinth is an internet chat room thread). The truth Armstrong is referring to relates to what she terms as “the mysterious workings of the psyche.” In the context of our curious history (and on a much lighter note), I aim to illustrate some of the ways in which labyrinthine mythology has been used to explore the human condition and entertain.

Labyrinths and mazes are a common literary trope. All genres make use of labyrinthine allegories and narrative structures. American critic Harold Bloom writes, “All literary influence is labyrinthine; belated authors wander the maze as if an exit could be found, until the strong among them realize that the windings of the labyrinth are all internal.” Clearly, we do not have the space here to consider a huge number of examples, or to debate their full meaning. We will, therefore, look at just a few, mainly from the twentieth and twenty-first century, starting with Ayrton’s 1967 novel The Maze Maker (Fig. 1). We noted in chapter seven that this publication led to a commission from financier Armand G. Erpf for a maze on his Catskill estate in Arkville, New York.

Fig. 1: Michael Ayrton’s The Maze Maker, 1967.

Ayrton writes, “This maze for the Maze Maker I made from experience and from circumstance. Its shape identifies me. It has been my goal and my sanctuary, my journey and its destination. In it I have lived continually, ceaselessly enlarging it and turning it to and fro from ambition, hope and fear. Toy, trial and torment, the topology of my labyrinth remains ambiguous. Its materials are at once dense, impenetrable, translucent and illusory. Such a total maze each man makes round himself and each is different from every other, for each contains the length, breadth, height and depth of his own life.”

The New York Times viewed the novel as “Proof of the power of classical myths to rekindle the interest and the imagination,” and English author William Golding declared, “Here, at last, mythology is acknowledged and accepted in all its beauty, brutality, unreason, and terror. Ayrton has written a unique book.”5 Described as an “uomo universale,” Ayrton was a true polymath who, in his relatively short life, excelled in writing, painting, sculpting, theatrical design, illustration, and broadcasting (radio and television). His full body of work is imbued with the Cretan myth.

Before we continue with other twentieth-century examples, let us look at the some slightly earlier ones. The nineteenth-century novel Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) by English author and mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson—better known as Lewis Carroll—did not feature a maze as such but the story has a mazelike quality (Fig. 2). Alice finds herself taking a labyrinthine journey and encountering many baffling situations as she asks, “Which way do I go from here?” The novel is a particularly well-known example of a maze archetype in literature, whereby the protagonist must navigate a path with multiple choices and dead ends. In 1966 American artist Robert Smithson declares in his essay on “Entropy and the New Monuments,” it is well to remember that this seemingly topsy-turvy world sprang from a “well-ordered mathematical mind.” Carroll’s popular novel went on to inspire many popular mazes, including that featured in Disney’s 1951 film Alice in Wonderland, and amusement park attractions, such as Disney’s Alice’s Curious Labyrinth (at several Disney attractions worldwide), and the English hedge maze at Merritown, Dorset, designed by Adrian Fisher.

Fig. 2: Illustration by Sir John Tenniel from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1869 edition.

In Mad Mazes, Robert Abbott featured “Alice in Mazeland” a “really hard” puzzle with the Red Queen’s rules. And Carroll, a mathematician and puzzle enthusiast, drew his own maze (opposite) to entertain his siblings, which appeared in Mischmasch, one of his family magazines. Another such archetype is L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (1900), supposedly influenced by Carroll. Baum’s novel, adapted for the big screen in 1939 with Judy Garland as Dorothy, was an overnight success, selling over twenty-five thousand copies in the first year and over three million by the mid-twentieth century.

A version of the Game of the Goose (see chapter eight) is featured at the turn of the century in The Will of an Eccentric, an 1899 novel by French author Jules Verne, whereby North America is used as a real-life game board (shown here). Seven players must race each other in pursuit of William J. Hypperbone’s sixty-million-dollar inheritance. In 1895 the Museum of the University of Pennsylvania had listed 146 different editions of Game of the Goose from all over the world. Verne’s novel was not originally published in America, although it might have sold well, considering the popularity of the game.

Over the past century, labyrinths and mazes have continued to feature in popular fiction, as narrative constructs and settings. In his 1980 best seller, The Name of the Rose, Italian author Umberto Eco fuses the world, the book, and the labyrinth—the latter of which is embodied in three ways: the unicursal labyrinth, the multicursal maze, and the rhizome, which is potentially endless, representing the labyrinth of human culture. The library, on the top floor of the Aedificium is a “great labyrinth … You enter and do not know whether you will come out.”

Described as a “vast and intricate library dystopia,” Eco’s library is presided over by a blind monk named Jorge of Burgos, a name not dissimilar to that of Argentine author Jorge Luis Borges, who penned the short stories The Garden of Forking Paths and The Library of Babel (1941). In 2011 a hedge maze in memory of Borges, designed by Randoll Coate, was opened at the San Giorgio Maggiore Island in Venice, Italy. The Library represents man contemplating the universe, with the books representing human experience in all its forms. The Librarian’s desire is that the Library’s final order will assert itself over the chaotic labyrinth.

Illustration of Lewis Carroll’s maze created to entertain his siblings. Find your way to the central diamond.

From The Will of an Eccentric by Jules Verne, 1900. William J. Hypperbone (deceased), millionaire and member of the Excentric Club, would bequeath sixty million dollars to the winner of this most unique version of the Game of the Goose. Seven contestants, assigned by lot from the population of Chicago, would play this Noble Game of the United States of America.

A 1911 ghost story by English author and scholar M.R. James entitled Mr Humphreys and His Inheritance features a “yew maze, of circular form, and the hedges, long untrimmed, had grown out and upwards to a most unorthodox breadth and height.” The true meaning of the tale and the purpose of the maze where one is Penetrans ad Interiora Mortis (“Penetrating into the interior places of death”) is much debated.

“The Liberator,” Simón Bolívar—in the 1989 fictionalized account of his last days, The General in His Labyrinth, by Colombian author Gabriel García Márquez—exclaims during his final moments, “How will I ever get out of this labyrinth!” The novel is a profound labyrinthine exploration of a life, and a final journey that brings to mind the existential isolation of the Mexican people as portrayed in 1950 essay by the poet and diplomat Octavio Paz, The Labyrinth of Solitude Life and Thought in Mexico (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3: Octavio Paz’s The Labyrinth of Solitude, 1950.

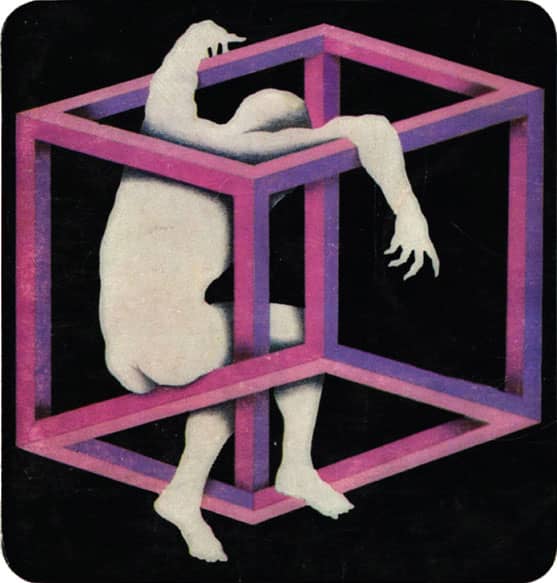

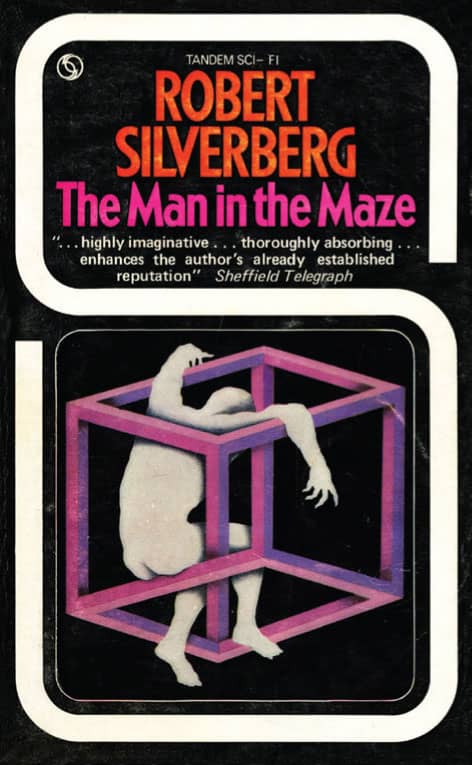

Labyrinthine constructs and mazes are found in many fantasy and science fiction texts, including Mervyn Peake’s Titus Groan (1946), J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings (1954–55), Robert Silverberg’s The Man in the Maze (1969) (Fig. 4), Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Tombs of Atuan (1971), Terry Pratchett’s The Dark Side of the Sun (1976) and Small Gods (1992), and Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (2000).

Fig. 4: Robert Silverberg’s The Man in the Maze, 1969.

All manner of scenarios are presented, including booby-traps with penalties, shifting shadows, tiles that must be stepped upon to avoid death, pathways in time, mines, ever-expanding pathways, and a labyrinth that is different for every visitor such as Pratchett’s ancient labyrinth of Ephebe, “full of one hundred and one amazing things you can do with hidden springs, razor-sharp knives and falling rocks. There isn’t just one guide through it. There are six, and each one knows his way through one-sixth of the labyrinth … The furthest anyone ever got through the labyrinth without a guide was nineteen paces. Well, more or less. His head rolled a further seven paces, but that probably doesn’t count.”

The maze at the Triwizard Tournament in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2000) presents several challenges for Harry, such as a gold mist that turns the world upside down, although it is the maze itself in the 2005 movie adaptation of the book that attacks Harry and his competitor, Cedric. Batman was lost in a maze for eight days in Scott Snyder’s comic strip The Court of Owls (The New 52 #1) (illustrated by Greg Capullo), where he was subjected to mental torture and physically beaten.

James Dashner’s The Maze Runner (2009) is the first in his young adult science fiction series. Dashner writes in his blog “this idea popped in my head about a bunch of teenagers living inside an unsolvable maze full of hideous creatures, in the future, in a dark, dystopian world. It would be an experiment, to study their minds. Terrible things would be done to them. Awful things. Completely hopeless. Until the victims turn everything on its head. I thought of it as Lord of the Flies meets Ender’s Game meets Holes.”6 The Maze Runner was released as a 20th Century Fox movie in 2014, followed by Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials (2015), and Maze Runner: The Death Curve (2018).

The hedge maze in The Maze, a 1953 3-D horror movie directed by William Cameron Menzies, described as “a spooky, evocative setting, practically dripping with latent menace,” is perhaps an influence upon The Shining, Stanley Kubrick’s adaptation of the 1977 Stephen King novel. The Shining has many labyrinthine motifs including a maze, which does not actually feature in the book. In the movie, Jack develops Minotaur-like characteristics and has a Cretan-esque ending. Initially viewed as a commercial failure, but now with a cult following, is Jim Henson’s fantasy Labyrinth (1986), described as a “mash up” of many genres. The works of Lewis Carroll and Jorge Luis Borges, among others influences Guillermo del Toro’s 2006 fantasy Pan’s Labyrinth. And in Chris Nolan’s Inception (2010), Ariadne is asked to draw a maze in one minute that can be solved in two as she is interviewed for the role of team architect.

Labyrinths and mazes have inspired television game shows, the most famous of which is The Crystal Maze (originally hosted by Richard O’Brien and revived in 2017), itself inspired by the 1990 French game show Fort Boyard. Versions of the French show were also produced in many other nations, including Sweden, The Netherlands, Finland, Russia, China, Japan, Canada, and Algeria. The American version was called Conquer Fort Boyard and Fort Boyard: Ultimate Challenge. The Crystal Maze spawned books, video versions, books, board games, and themed visitor attractions.

Based on Shakespeare’s Macbeth (with a nod to Hitchcock and film noir), Sleep No More is an immersive theatrical mazelike experience first shown in London in 2003. In New York, since 2011, at a block of warehouses named the McKittrick Hotel, members of the audience (masked and silent) go on a choreographed chase through the labyrinthine building—if you happen to be in London, look out for the 270 labyrinths on the London Underground, created by English artist Mark Wallinger in 2013 to mark the Underground’s 150th anniversary.

Adrian Fisher writes in 1990, “Beyond a certain point, consideration of appearance, atmosphere and meaning overtake mere puzzlement … mazes should be judged as much on artistic impression as technical merit.” Labyrinths and mazes have inspired artists worldwide for generations, and we will note just a few examples here from the modern era.

A remarkable and arguably controversial labyrinthine installation is Spiral Jetty by American artist Robert Smithson, a 1970 earthwork sculpture at Rozel Point, Great Salt Lake, Utah. Made of mud, precipitated salt crystals, rocks, and water, the spiral is 1,500 feet (457 m) long and 15 feet (4.6 m) wide (Fig. 5). An assessment in American Scientist observes that while little environmental consciousness seems to have been involved as “the environment yields to the flats of the engineer-geometer, Daedalus,” Smithson probably did want the work to disappear through natural entropy (the reconquest of human works by persistent natural processes).7 In 2017, Utah’s House of Representatives and Senate approved the designation of Spiral Jetty as the official state work of art.

Fig. 5: Spiral Jetty by American artist Robert Smithson, a 1970 earthwork sculpture at Rozel Point, Great Salt Lake, Utah. Photo: Soren Harward.

Another earthwork, but not on the same scale, is American Richard Fleischner’s 1974 Sod Maze, in the grounds of the Chateau-sur-Mer, one of the preserved mansions in Newport, Rhode Island (we noted Fleischner’s cornfield mazes in chapter seven). The Sod Maze reflects the turf mazes we looked at in chapter five. It has a diameter of 142 feet (43 m) and was commissioned as part of the Monumenta exhibition of outdoor sculpture. It is now part of the collection of the Preservation Society of Newport County. His 1973 Tufa Maze, installed at the Rockefeller Estate in Pocantico Hills, is made of moss-covered tufa stone. According to Tatarella, this piece recalls the solemnity of a tombstone. Fleischner himself writes in 2011, “My work grows out of the details that I recognize and acknowledge within the commonplace and universal.” In 1978 Fleischner created a Chain Link Maze on the campus of the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, as part of a series titled Surface. Made from galvanized chain-link fencing, this installation, which reminds Tatarella of a prison yard, was subsequently destroyed.

In 2004 the Japanese architect Arata Isozaki and artist Yoko Ono created an ice maze entitled Penal Colony 1 for the Finland Snow Show. Using one thousand blocks of ice cut from a frozen lake, the maze was square and technically transparent, although it became increasingly opaque toward the center. While the walls became shorter toward the center, making the space more visible, it would still have been cold and dark inside. Previously, in 1971, Ono created a maze from plexiglass, metal, and wood, which is still exhibited.

Since 1994 the Japanese artist Motoi Yamamoto has been creating (and destroying) intricate labyrinthine salt installations worldwide. Moved to do so by the death of his sister, who was only twenty-four, Yamamoto says that drawing a labyrinth with salt is like following a trace of his memory. In Japanese culture salt is a symbol of purification and is often used in ceremonies that celebrate life and death. After each exhibition, Yamamoto performs a ceremony called Return to the Sea by collecting up the salt and taking it back to the water. In 2012 Yamamoto created a salt labyrinth for the Making Mends exhibition at the Bellevue Arts Museum, Washington. The process of creating and destroying the labyrinth is both meditative and transcendental, reflecting to some extent the North American sandpainting Navajo mandalas that we looked at in chapter three.

In 2013 a counselor at Sacramento State University, California began to create labyrinths of golden leaves from the gingko trees in the campus grounds. Joanna Hedrick, who says she is inspired by the work of English artist Andy Goldsworthy, rakes the leaves into intricate spirals and labyrinths. Engaging with such installations, whether they are made from leaves or from salt, may stimulate a gentle, if not profound or emotional experience, which is perhaps intended by the artist.

There are many labyrinthine-esque installations, however, which move us in different ways and may even disturb. For example, Belgian artist Carsten Höller’s Decision, a labyrinth described by the artist as a “test site” to “induce hallucinations, in the widest sense.” Argentinian artist Tomás Saraceno’s immersive Cloud City, which debuted in 2012 at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, is described in the New York Times as “a particularly prominent example of fun-house formalism.”8 That may be good or bad, depending on what sort of experience the visitor is seeking.

I could go on citing other examples and genres, but, alas, have run out of space. I hope I have gone someway to satisfying your curiosity. Do contemplate and complete the puzzles in this book, and should you want more, take up further reading and interact with labyrinths and mazes “out there” in any way you can. As the puzzle aficionado Chris M. Maslanka recently declared, the golden age of the maze is … NOW!