‘The human organism is the most complex and

extraordinary entity in the known Universe.’

– Hans Selye, The Stress of Life

Picture, if you will, the opening scene from Bambi. A young inexperienced deer is grazing the forest floor under a green canopy of trees. His head is down, rooting for acorns and seeds. Subconsciously, though, his nose is constantly sampling the air, while his ears, like mobile antennae, scan for suspicious or threatening noises. His brain has adapted to the subtle ambient tunes of the wood and pushed them to the background of awareness, as they are deemed not to be a threat. While his eyes are on the floor, he cannot use them to spot predators, so his ears are everything. They can determine where a sound is coming from, and how far away it is, and will triangulate the threat even when it is obscured by a bush or tree.

Suddenly the tranquility is broken by the snap of a twig. He freezes even before he can respond. He uses his ears to locate the noise and focuses his eyes to assess the danger. He breathes slowly through his nose, scenting the air. His pulse quickens and his muscles tense, readying him for action. His forebrain shuts down; there’s no time for thinking about anything except which way to run. Thinking could be fatal. After a moment of intense alertness during which he senses no attack is imminent, he stands down and returns to grazing, but now raising his head up more frequently to survey the landscape. He is twitchier now. He is sensitised.

His brain makes the natural percentage decision that the longer there is no attack, the less likely it is. This time there is no threat.

But now imagine the same scene, this time with a wolf breaking cover, ears back, teeth snarling. Bambi’s freeze turns into a desperate run in the opposite direction. He cuts himself and strikes objects, even breaks a toe, but nothing slows him; he feels no pain – why? Because whatever injury he has is infinitely less serious than being dead; pain at this moment would be an unnecessary distraction from mortal danger. Eventually he outruns the wolf, who skulks off, disappointed. To Bambi’s small and primitive brain, it is a crisis response soon over, a percentage game: survive or die. His wounds heal, and compared to being dead the pain is a trifle. He will continue to graze and think deer-like thoughts because he will not be worried or distracted by what might happen; just by what he knows to be happening now and its level of imminent danger to his survival.

These two scenarios illustrate how pain is mediated by context and the level of stress.

When Bambi breaks a toe or even a leg while fleeing from death, he keeps going, unaware of his injury. Unless the limb has completely buckled and he is unable to support his weight, he will carry on running until he has either escaped or been caught. This phenomenon is called stress-induced analgesia. The brain mobilises its own internal pain relief system based on naturally made opiate chemicals. These chemicals flood all of the relevant synapses involved in the response, blocking the pain. There have been many instances of athletes and soldiers who have suffered serious injuries but have only become conscious of them once they have completed their event or task. For example, soldiers who have had a leg blown off by a land mine have been known to try to get up and walk, unaware of the gravity of their injuries. This is why the first thing an army field medic does when attending an injured soldier is to explain what has happened.

When I was thrown across the bonnet of a car while riding my moped in London recently, the first thing the ambulance crew said to me when they arrived on the scene was: ‘You’ve been in a road accident.’ Stating the obvious, you might think – but necessary. At that point, due to stress-induced analgesia, I was feeling no pain from my injuries and, as we saw with Bambi, my forebrain and emotional centres had shut down while my body dealt with the level of threat to my life.

A contrasting response kicks in once the chase is over. Satisfied that the impending danger has gone, the brain allows the incoming flood of nociception to make its presence felt and starts to assess the effects on the body. Now follows a period of stress-induced hyperalgesia, when the level of pain becomes all-consuming and is escalated by the realisation that the injury is serious and in its own way threatening. Fear and meaning become involved.

A few hours after my moped accident, my body began to ache and bruises started to appear as my brain allowed a flood of messages from all the tissue receptors in my muscles to establish themselves as pain. Thankfully, I had no serious injuries, but even if I had, I would have been protected from the knowledge of this until then – i.e. after the crisis had passed. It was only at this point that my forebrain and all of the other emotional centres I had switched off kicked in, catastrophising about what might have happened and the possible impact on my work and my family.

To understand why we humans need a stress response and how it makes us behave the way we do, we need to go back to prehistoric times, when our ancestors regularly came face to face with fearsome creatures that made them, like Bambi, freeze or flee. Over time we learned how to use our guile to survive each day; we found safety, protection and power in social groups with whom we could hunt, feed and mate. We even thrived on episodes of high adrenaline, as these kept us alert, sharp, lean and quick. And as Neanderthals gave way to Homo sapiens some 70,000 years ago, we developed altruistic behaviour, such as grooming and nursing, to prevent disease and aid recovery. We learned that if we let the best fighter or hunter die, we endangered the whole tribe because it prevented his knowledge from being passed on to others and from protecting us in the future. So, the tribe took care of him. Anthropologists have found in many sapiens skeletons evidence of major long bone fractures that have clearly healed. This shows that the victim was not left as a sacrificial meal for a lion; he was nursed back to health by the tribe.

Propagation of the gene through survival and sex produced the two key drivers to our existence: fear and lust. Arguably they drive us still, only tempered and tamed by the overlay of modern societal rules. However, we must remember that the environment in which we now live is very different from the one from which we evolved. We evolved over millions of years, but the changes in our more recent history – the development of agriculture 12,000 years ago, and the industrial revolution only 200 years ago – have occurred in such a relatively short time that we have not yet been able to fully adapt to them. As a result, much of our bio-psychology is poorly suited to our current environment.

In the modern, developed Western world, we no longer daily face the sort of mortal dangers that we did in the past, and yet we remain as competitive as we always were. According to Professor Jean Twenge, head of psychology at San Diego University, we are now physically the safest we have ever been but our children are the most emotionally fragile they have ever been.14 Think about that for a moment – because it bodes badly for our experience of pain, among other things, in the future.

The stress response is fundamentally a mechanism we developed to adapt to our environment, to improve our chances of survival. The stressors then were mostly physical, involving running from attack, fighting, competing, gathering and, latterly, farming. They often represented real mortal threat and danger. By comparison, other worries based on social competition and jostling for position in the hierarchy were mere niggles.

And yet now, worries to do with social competition and the like are among our main stressors. These days we have very little in our environment to adapt and respond to, except on a cognitive and intellectual level. We have lost context in relation to fearful events and now, it could be argued, we fear almost anything we simply don’t like. We have become over-sensitised to trivial – even subliminal – worries.

What’s more, as primitive brains grew and developed with each successive generation, humans not only developed an awareness of danger but, crucially, how to anticipate it – a uniquely human trait. And from this anticipation came anxiety, the fear of what might happen. Their offspring started to be born ‘pre-loaded’ with certain neuropsychological software designed to protect them, and hardwired to respond in certain ways. These traits are known in neuropsychology as ‘biases’ and they strongly affect the way we live our lives.

One important example is what we now call negativity bias – this is where we attach more importance to the seriousness of something happening than to the likelihood of it occurring. Back in prehistory, it saved our lives, but in modern times it flaws our decision-making and affects our ability to take risks.

Let’s imagine that one day, back in the time of early man, you went to the watering hole and found a sabre-toothed tiger there. Would you decide never to go back, to avoid the risk of being eaten, or would you risk it because you needed a drink? The effect of negativity bias in our decision-making would dictate that we would rather die of thirst by slow dehydration than risk a painful but quick death at the hands of a predator. The horror of being eaten outweighs the less certain and less painful death by parching. Contemporary research into decision-making by humans today has confirmed this bias: anthropological analysis of hominid remains has been done which shows dehydration of tissues before death.

Anthropologists have discerned that early man could make one of two mistakes in this situation: he could think either that a tiger was lurking in the bushes when it actually was not, or that there was no tiger in the bushes when there actually was. The cost of the first was a life of needless anxiety while the cost of the second was death. Needless to say, we are descended from the ones in the first group – the anxiety-prone ones, who avoided death long enough to procreate. The bolder strain of early man who ran the risk of being eaten by the tiger probably didn’t live long enough to pass on his genes. As a result, the default setting of the modern brain is to overestimate threats and underestimate opportunities, and also underestimate our resources to cope with threat and to fulfil those opportunities.

Unfortunately, this anxiety-prone behaviour then gets amplified by another hard-wired setting, confirmation bias, which is the tendency to search for, interpret, favour or recall information in a way that confirms our pre-existing beliefs or ideas. The more we worry about something, the more we believe it to be true. Thus we become preoccupied with threats which at first seemed small and manageable. I will come back to this later, when I talk about what stresses us in modern life.

So do we even need this stress response any more? Yes, because if you need to be alert to a threat or danger, like any normal mammal dealing with an acute emergency, and you cannot activate the stress response, you are in big trouble. In people with conditions such as Addison’s disease and Shy-Drager syndrome, who are unable to secrete vital stress hormones, this becomes all too apparent. When confronted with an acute stress like a car accident, they cannot maintain their blood pressure and go into shock.

But equally damaging, and much more common, is an excess of stress hormones. When we are sitting in traffic, endlessly worrying about mortgage payments or fretting about a bullying boss, and are unable to switch off the stress response, we risk serious damage to our health.

And this is where stress and pain meet. Stress is fundamentally linked to pain and illness and, if not addressed, can go on to cause disease. Like pain, it arises when we can no longer cope with an imbalance that has developed between ourselves and the three elements or domains of our environment (see Figure 3 at the end of this chapter): society, biology and psychology. And I feel passionately that a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of stress can not only benefit professionals – doctors, coaches, policy makers – who in turn will be able to treat illness effectively, but also provide a new philosophy to guide us all within the laws of nature and help us improve the way we live.

Like most mammals, we humans are generally able to maintain our internal environment very successfully – i.e. the composition of our body chemistry remains remarkably constant – despite all the changes around us. For example, even when exposed to extremes of heat or cold, our body temperature does not vary. And the way it does this is by a process called homeostasis. This is what ensures that our internal environment is maintained and regulated against whatever our external one throws at us.

A stressor is anything in the outside environment which knocks us out of homeostatic balance. And the stress response is what our body does to re-establish this balance. For most animals, the stress mechanism is not only what maintains their health but helps them stay alive. Their bodies’ physiological responses are superbly adapted to dealing with short-term physical emergencies, for example being chased by a predator. For the vast majority of beasts, stress is about a short-term crisis which ends in either survival or death.

But for Homo sapiens it’s different. As we evolved and adapted, our new-found cerebral and emotional abilities brought with them more angst, and more to process. Our ability to cope began to be tested in new ways as we had to mobilise many more subtle physiological responses to manage an ongoing, unrelenting type of stress – and ultimately our coping mechanism began to be eroded if it was tested for too long. To reflect this, Bruce McEwen, a neuroscientist at Rockefeller University, expanded the idea of homeostasis into allostasis, whereby rather than our having specific responses to specific stressors, stress actually has a more wide-reaching effect on us, with myriad adjustments being made throughout different systems in the body to address the shift in balance.15 He coined the term ‘allostatic load’ to describe the micro wear-and-tear which ensues as a result of a continued assault on our internal control mechanisms and to explain how, if this becomes damaging enough, the system will fail.

As Professor Robert Sapolsky, a researcher and author on stress at Stanford University says: ‘This is the essence of what stress does. No single disastrous effect, no lone gunman. Instead, kicking, poking, impeding here and there, make this a bit worse, that a bit less effective. Thus, making it a bit more likely for the roof to cave in at some point.’ 16

This combined and global effect of stress has been demonstrated in numerous studies, including one carried out by military researchers many years ago which looked at the cardiac health of soldiers who had seen intense active combat.17 One cohort of subjects comprised veterans from the Second World War and the other veterans from the Vietnam War, some of whom were just 19 years old. Comparing the two cohorts, the researchers found that the physiological condition of the hearts of the soldiers who had fought in Vietnam was poorer for their age than those of the Second World War soldiers – indeed, the Vietnam veterans’ hearts were like those of 50-year-olds who had not seen combat in a normal population.

The researchers worked out that, although the WW2 veterans had seen intense and traumatic periods of fighting, they had also had extended periods to rest and recover, whereas the young Vietnam veterans had seen enemy fire almost every day of their tour. An additional stressor had been the fact that the enemy in the Vietnam war did not wear a uniform, so the soldiers could not distinguish them from local villagers, and they were thus unable to predict where the next attack would come from. This extended stress had far more damaging and permanent effects on their health.

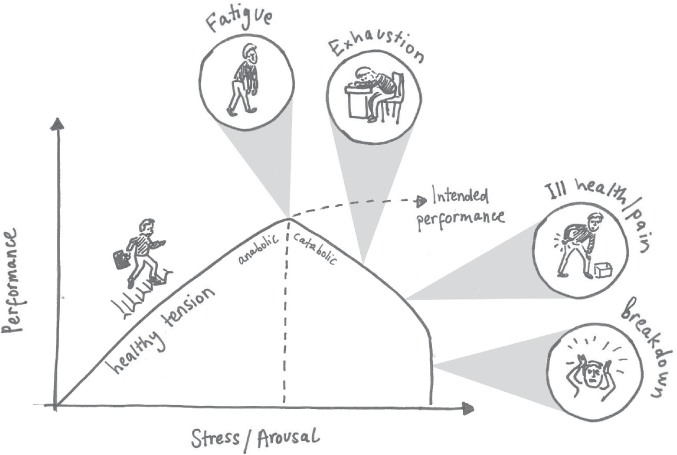

It was a London cardiologist, Dr Peter Nixon, who in 1979 first elucidated and described the ‘Human Function Curve’ (Figure 2, below), which depicted graphically the fatiguing stress response.18

Figure 2: Dr Peter Nixon's Human Function Curve, depicting the fatiguing stress response

What Nixon’s graph shows is how the body can absorb, adapt to and cope with ongoing stress for a while – even benefit from it – until a critical inflection point, when, if there is no respite, the system fails, usually resulting in some form of illness. Nixon’s work was seminal and has become even more relevant now in the stressful 21st century.

It is important to note that although the curve shape is the same for all of us, the point at which the inflection or collapse occurs will be different. Some people are quite simply better at coping within their environment than others.

In general terms there are two types of stress. The first is eustress, which is the sort of exciting, ‘on-it’ stress that occurs when an individual feels extremely busy but also useful and valued, and excited about the outcome of something. I call this ‘benign’ stress, because although it may make you tired or bad-tempered, it is short-lived and does not cause illness.

The other type is distress. This is the unpleasant or harmful variety which causes illness and disease. I call this sort of stress ‘malignant’, because it also carries with it the potential and actual ability to cause cancer and heart disease, as well as pain. This is the stress that is cumulative and arises from long-term issues such as an unhappy marriage, childhood trauma or a dead-end job.

A Whitehall study carried out by Professor Michael Marmot, an epidemiologist at UCL, highlighted this in a startling way.19 It studied 28,000 employees in the civil service from 1967 up to the present day, looking at the social determinants of health, i.e. which are the economic and social conditions that influence individual and group differences in people’s health. It discovered that there was a ‘status syndrome’, where the lower the grade of an employee and the less control they had over their job, the higher their levels of stress and resultant effects on their general health. The further down the hierarchy they were, the higher their levels of disease and mortality rate and the more likely they were to experience pain.

It is not always easy to distinguish good from bad stress, however – and, in some sectors, we are losing our ability to tell the difference. In high-performing, competitive corporate environments, stress has become a dirty word. It is seen as a weakness and so it tends to get ‘sucked up’ or buried. Even workplace jargon has become unemotive. We don’t talk about a ‘problem’ but a ‘challenge’ or an ‘issue’. More on this later.

As we saw earlier, we Homo sapiens, with our hugely developed cerebrums and limbic (mood and emotional) centres, have the ability not only to activate the same flight responses as animals, but also to know when we might need them in the future. We learned to make associations with danger and to predict their likelihood.

As time went on, with our bigger brains, we learned to cook, which meant we could spend less time chewing plants (poor old chimps spend eight hours a day doing it) and more time on social development and cognition. We learned to outwit our predators and prey rather than overpower them. We formed social hierarchies which required sophisticated new behaviour, and we developed emotions to encourage protection and attachment to others. This not only kept us alive but also ensured the propagation of our genes in a new and altruistic way. But with all that came a different kind of stress – psychological stress – because with our increased intellectual capacity came fear, anticipation and anxiety as well as suffering and pain.

Today, when we sit around and worry about mortgages, taxes and public speaking (which for some people is scarier than death), we switch on very similar stress responses to the more physically initiated ones. The problem is that in our modern society we are almost never free of those stressors. The response never stands down; it becomes ever-present, sapping resources. Much like pain, it becomes a habit which is easier to keep with us than to let go of. Research has shown that, when we are continually stressed, a part of the brain known as the amygdala becomes sensitised not just to actual dangers but to small or even potential risks. As a result, we become more anxious and sensitive to threat, and more vulnerable to the very thing that is meant to protect us. We adopt psychological ‘crutches’ to support the state we are in, either in the form of fear-avoidance behaviours, or by taking stimulants to make us happy and relaxants to keep us calm.

This is the unpleasant, harmful form of stress I mentioned earlier – the one that can cause illness and disease. There is a difference between these two, by the way; illness is a person’s subjective experience of their symptoms, while a disease is a definable medical condition. And pain and stress belong in both domains. Basically, if pain and stress continue for long enough, an illness can develop into a real and verifiable disease. So you can feel very unwell, as with the painful and distressing condition known as fibromyalgia, even though there is no detectable evidence of disease. As I explained in Chapter 2, you can have nociception without pain and pain without nociception.

This is an important point because the ‘ill’, and in most cases ‘chronically stressed’, rather than the ‘diseased’, represent a very large number of patients visiting the doctor. Research would suggest that in the USA the number of visits which are for stress-related conditions is as high as 60 to 80 per cent and it looks similar in the UK.20 However, it is difficult to be very accurate because the studies examine separate symptoms and conditions rather than those specifically related to stress as the cause.

In the UK, most data looks at mental health problems related to stress, a phenomenon which is rising at a terrifying rate; and there is significant overlap of mental health problems with pain. Many of those presenting to their GP will be treated with painkilling drugs, useful or not, or will be referred for expensive tests and scans because the doctors, who are under enormous pressure and have precious little time, will practise ‘defensive’ medicine and refer them ‘just in case’. Most will have nothing abnormal diagnosed and go on to get better anyway. However, the small percentage of these presenting patients who are really sick will not be given the time and attention they need. On average, most British GPs have seven minutes for an appointment.21 It is worth noting that if the stressed contingent realised their symptoms were a response to their stress and therefore didn’t bother going to see their GP about them, the really sick would have much more time with the doctor. Moreover, fewer GPs would be leaving the profession.

One of the difficulties in treating people suffering from stress is that we all have different stress thresholds and we all perceive stress differently. For some, stress is external and encapsulates the burden of daily life which is harmful and to be avoided. For others, it is more internal and represents a response inside the body; if we feel anxious about something we say we are ‘stressed’. There are high-powered executives for whom it is a status symbol without which they would in some way feel inferior or invalid: the crazily busy, totally stoked man or woman, doing high-stakes deals around the world, meeting fabulous people in fabulous places. Athletes and performers, meanwhile, manage to convert or reframe stress mentally as excitement, readiness, a coming-together of all the elements of their training and a chance to shine and win.

We all have an in-built capacity to cope with stress, with our bodies acting as a buffer. Each time we are tested we can shift the equilibrium a little to absorb the demand. But when those demands become too great or too repetitive, depending on our individual threshold, the balance is disturbed and our well-being is threatened. A situation that is stressful for one person may be benign or even stimulating for another; stress is subjective, like pain – an individual’s responses to different stressors relying on their past experience, education, beliefs, personality and genetic make-up. As Hans Selye, the eminent researcher on stress whom I quote at the beginning of this chapter, once said: ‘Stress, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.’ 22

In 1956, researchers in Montreal looking into nutrition and growth rates in rats made an unexpected discovery about how stress works.23 During their experiments, it became conspicuously clear that one group of caged rats was not only not thriving but was actually not growing at all, despite being on one of the best diets. It was a PhD student who pointed out the reason why: the rats had been placed within a few feet of a cage containing a cat, which was part of a different study.

The stress of being close to the cat and unable to escape from the cage was inhibiting their growth. When the cage was moved, they quickly caught up. This showed the importance of three factors as contributors to chronic and debilitating stress in the study on rats: an imminent and threatening danger; a constant and unremitting presence of it; and a lack of control over their ability to escape.

Another example which elegantly shows the far-reaching effects of stress (again incidental and unintended) was provided in a study carried out in the 1930s by Dr Elsie Widdowson, a formidable character who pioneered nutritional science and was the first to analyse food and its constituents.24 After the war she would be tasked with drawing up nutritional programmes for Holocaust survivors.

In her study, Widdowson looked at the effects of different breads on children’s growth. Her subjects lived in an orphanage, which was divided into houses run by house mistresses.

Widdowson was puzzled to note that the children in one house failed to grow nearly as quickly as the others. Eventually, a mistress from a different house approached her secretly, and helped shed light on the matter. She explained that the house in which the children were failing to grow was run by a mistress known as ‘Dragon-lady’, who was notoriously sadistic and mean to the children at mealtimes, castigating and punishing them so that they dreaded eating. It turned out the reason the children were not growing was because of the stress induced by her remonstrations. After ‘Dragon-lady’ was removed, there was an almost complete recovery in their growth rates.

Stressors can of course be physical (injury, disease, surgery) as well as psychological, but it is the latter that we will focus on here, as psychological stress affects more people more of the time in modern Western and industrialised nations. What’s more, it also elicits biological responses which eventually develop into pain, illness and disease. In most, it will produce the symptoms and pain of the ‘worried well’ or, as psychologist Oliver James so brilliantly coined it ‘affluenza’.25 Sadly, in some, however, it goes on to produce serious conditions such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease and depression (for which I will produce real evidence).

In the UK, pain costs the state more than cancer and diabetes combined,26 but no one is really talking about it or coming up with answers to treat it. My experience, and that of many other professionals, is that much of this pain is a manifestation of a stress-filled society.

Stress has many strikingly similar traits to pain. Our response to it is very personal and depends on how we assess the demands placed on us and our capacity to cope with them. Psychological stress is as much about how we see the world as about how it really is. And importantly, as with pain, the brain can feel stress without being conscious of it. Subconsciously, too, we can be affected by other people’s stress: people who are stressed often exhibit it in their behaviour so that family members or work colleagues pick up on it and feel it themselves.

The ‘contagious’ nature of stress has been confirmed by research carried out by the US army, which showed that we detect and subliminally respond to the fear and stress hormones (pheromones) secreted by other people; we literally smell their fear.27

The evolutionary value of this is clear – it is usful to be able to communicate to the group any gathering or impending threat, and this is particularly pertinent to females and their fertility. In the case of animals, for example, if a new habitat or feeding ground became potentially dangerous, it was not a time to be giving birth or raising offspring; and so the stress response was communicated through the group and resulted in impaired ovarian function and a failure of the eggs to implant. Males in the group would also see a decrease in their libido and sperm count. And that reaction – something that was created by nature to protect the group and allow for agility and mobility in the event of attack – has become in modern times a response that causes enormous angst and misery.

Even though there is no mortal danger, the constant low levels of stress in our society – not helped by the fact that many people are opting to have children much later due to financial pressures – are lowering fertility rates. This in turn causes further stress and anxiety. Indeed, it is now known that such stress activates inflammatory and immune responses in both males and females, which prevent conception. A joint American-British study has shown a correlation between elevated levels of an enzyme associated with stress found in saliva and infertility in women.28 The study suggests that finding safe ways to alleviate stress may play a role in helping women become pregnant.

And then there is the way in which stress manifests as pain. Many of my patients have expressed the ‘pain’ of not being able to conceive: not only emotional but physical pain – headaches, and neck and back pain. Some of my female patients also express it as deep pelvic pain, the source of which is chronic tension in their pelvic floor muscles. As one of my very wise tutors used to say: ‘This woman’s pain is a megaphone for her emotions.’ This is just one example of how stress and pain are fundamentally linked and, in many cases, how long-term stress evolves into a physical condition or illness.

From as early as the late 1960s, Dr John Sarno, a rehabilitation specialist, working at the Rusk Institute for Rehabilitation Medicine at New York University, came up with a very interesting theory: that most chronic pain is the result of deep-seated pent-up anger and rage, often originating from childhood.29

He believed the patient’s subconscious anger was trying to establish itself consciously as physical pain, in order to distract them from more personal and emotionally painful issues. He discovered that if you could make the patient understand and accept this phenomenon and deal with what was really behind the pain, then the subconscious brain just got back in its box, as it no longer needed to establish itself. If you like, the call from within was being answered. This was particularly the case with hard-working perfectionists, driven by self-imposed pressure that left them feeling stretched to breaking point. Sarno posited the idea, which would later be evidenced by research, that there was a trend in those who had chaotic childhoods, in which they struggled to get control over their unpredictable environments, particularly women, towards producing chronic pain in adulthood.

When Sarno published his book The Mind-Body Connection in 1991, it was widely acclaimed – although it was also clear that many in the medical profession, particularly in spinal medicine at the time, wanted his theory to go away as soon as possible, as it threatened to put a spanner in the works of a lucrative industry.

I was lucky enough to train with Sarno and saw him achieve remarkable results with patients who had suffered agonising pain for years. By far the biggest cohort he helped were patients with back pain, which is the most common type of chronic pain. He would famously give them three lectures in order to cure their pain. (I should point out that he did first screen patients by telephone to assess their suitability for his treatment.)

Since Sarno first posited his ideas in the 1960s, medical science has moved forward in leaps and bounds, particularly in the field of imaging and MRI scanning, which is now able to pick up brain activity (known as fMRI). It was Sarno who put the previously poorly described mind/body relationship vis a vis pain on the map, but he was never really appreciated for it. He died in 2017, aged 93, disappointed, I believe, that his ground-breaking work had not been formally recognised and was still regarded as controversial. I think if he could have seen how his ideas are being incorporated into the mainstream today, just a couple of years after his death, he would feel vindicated.

Of course, for many sufferers, the concept that the very real physical pain they feel might have its roots in childhood is hard to take on board. But the fact is that the most consistently identified risk factor in the production of chronic pain is the inability to express emotions, particularly those associated with anger. Repressed anger increases the physiological stress on the person and creates an unnatural biochemical environment in the body. Often other emotional factors are involved, such as hopelessness and lack of social support.

As Gabor Maté has said: ‘The person who does not express negative emotion will be isolated even if surrounded by friends, because his real self is not seen. The sense of hopelessness follows from the chronic inability to be true to oneself on the deepest level. Hopelessness leads to helplessness since nothing one can do is perceived as making a difference.’ 30

A Dutch study showed how negative emotions could affect pain.31 The authors compared female patients who had been diagnosed with fibromyalgia with a group who had no pain. They applied an unchanging painful stimulus to both groups and asked them to grade the pain, firstly when they were thinking about an emotionally sad or angry event, and then when they were thinking about something emotionally neutral. In all cases the pain level reported was higher when the women thought of emotionally negative events, and particularly so in the case of the fibromyalgia sufferers.

Psychological factors such as uncertainty, conflict, lack of control and lack of information are also seen as powerful activators of the stress-response system. The most important of these factors is lack of control – the impact of any stressor depends upon the degree to which it can be controlled, i.e. can the person escape, alter or eliminate the stress or pain? However, many experiments, on both animals and humans, have shown that it is the subject’s perception of the control they have on their health, rather than their actual degree of control, that has the greatest impact on them.

I have seen in my own clinical practice time and again how important a sense of control is in helping patients deal with chronic pain. A person who believes they are in control of their pain will consistently cope with it better. This has also been demonstrated in an experiment comparing the amount of painkillers required by post-operative patients.32

The authors of the study found that those who were put in charge of their own pain medication took far fewer painkillers than those who had them administered. They concluded that this was due to the fact that they didn’t have to worry about when they would get the medication from the nurse.

So we can see that the mind and body are constantly striving to return to a state of balance and that they have the capacity to absorb and cope with stresses put upon them and to correct imbalances through various adaptive compensating mechanisms. Hippocrates made this point way back in the 5th century BC when he taught that disease is not only suffering or pain (pathos) but also toil (ponos); the fight of the body to restore itself to normal. These processes are better understood now. And understanding them, as well as being able to recognise when they are under strain and where that strain comes from, is the answer to relieving the suffering of many.

This is all good news. Because, by changing how we view the world, learning to understand stress and when we are subject to it, we can alter our susceptibility to it and its most frequent outcome – pain.

On the page opposite is a working pictorial representation of how I assess a patient’s situation with respect to their pain and the contributing stressors affecting their system. I have it on my desk and in my mind’s eye while taking a history. Remember the bio-psycho-social model we discussed in Chapter 1? Well, the same interlocking rings are relevant to both the pain and stress factors in a patient’s life. And, if we superimpose the two, we end up with a model by which to assess which factors are key to that person in terms of where their pain and stress collide, and which factors are less relevant – i.e. is the pain/stress coming mostly from the psychological sphere? Or is it more socially motivated? Which area do we need to work on to bring them back into balance?

Figure 3: The bio-psycho-social model of pain and stress factors and how they interlock

It is here that I want to introduce you to Lucy, who presented with painful symptoms that were ultimately the result of a long-term stress response.

Lucy was 34 and a successful executive in a small media firm which employed 100 people. She had been promoted to senior management and reported directly to the CEO, Michael.

Lucy was engaged to be married and arrangements had begun for the wedding. She was conscientious and something of a perfectionist. She generally over-worried about life but that also made her good at her job.

She came to see me because she had done the rounds of therapists and surgeons for ongoing headaches, neck and facial pain, and tinnitus. She frequently experienced pins and needles in her face and hands. She felt foggy-brained most of the time and her sleep was poor. Her anxiety was worsened by the fact that no one seemed to be able to help her or identify the source of the problem. She was convinced she had multiple sclerosis and had googled a number of her symptoms, which only worried her more.

Various doctors had begun to imply that she was simply neurotic because all of her scans were normal. In fact, the more they imaged her, the more concerned she became.

From her very first appointment, it was obvious that Lucy suffered with hyperventilation (breathing too shallowly and rapidly) and tended to hold her breath for extended periods. When she did take a breath, she used her neck, shoulder and chest muscles all the time, acting against gravity and wasting energy. She looked washed out and tired and her hands were pale and cold. She also sweated a lot from her armpits, which made her feel self-conscious at work, so she never took her suit jacket off. She had lost her confidence and had become very self-critical, and dreaded presenting to colleagues as she got tongue-tied and forgot details. She had experienced a decrease in her libido, which worried her further because she was hoping to get pregnant soon after the wedding.

In short, her outlook on life had become very negative and she was concerned she was becoming depressed. She had fought low moods as a teenager but thought that she had kicked them. She had also recently put on weight around her belly and she just couldn’t shift it.

I started by reassuring Lucy that all was not lost and that I was pretty sure she not only did not have MS but that the source and cure for the problem was fairly simple.

I got her to lie on the examination couch and taught her how to breathe from her diaphragm – by asking her to expand and contract her belly and not her chest as she breathed. Immediately, the tight and tender muscles in her shoulders and chest relaxed, and she became less clammy.

I explained how her posture had changed due to the breathing dysfunction and that her postural muscles never rested and were full of painful trigger points. Many of these points were in her jaw and neck muscles, and were causing her headaches.

I asked her to wear a breathing monitor for a week which would ‘speak’ to her phone and track her breathing. It would also buzz at her when it caught her holding her breath or breathing erratically. At her next appointment, when we looked at the tracking app, we discovered that Lucy regularly went into erratic breathing and, at a specific time (3pm) on specific days (Tuesday and Thursday), markedly held her breath. I asked Lucy what it was that she was doing at this time that stressed her so.

She was surprised when she realised that the 3 o’clock slot was a twice-weekly catch-up meeting with her boss, Michael. I asked her how she felt about her relationship with him, and she admitted that she found him difficult and volatile and that he seemed to shut her down when she was being creative or wanted to take a lead on something. He also tended to undermine her in front of junior colleagues. We went back over her childhood and discovered that Lucy’s father had been an alcoholic. When he was drinking he was volatile and she and her siblings would tiptoe around him, trying not to antagonise him. Her mother had always been timid and submissive with him and implored them not to upset him. As a result, Lucy had always dreaded and avoided confrontation.

I suggested to Lucy that elements of Michael’s behaviour might remind her of her father and that she was struggling to assert herself with him. She agreed that this was a distinct possibility. I proposed some strategies to help her move forward with him, including suggesting to him that they had a drink outside work to discuss their relationship issues. Bravely, Lucy did this and it was a great success. Michael admitted that he felt threatened by her as she was clearly capable and more creative than he was. By discussing her feelings with him, Lucy had encouraged him to open up. Over the next month, the improvement in their working relationship, and the general atmosphere in the office, was evident to all concerned.

Most importantly, the rest of Lucy’s symptoms faded away. This is not to say that she would not face stressful situations in the future, but she now had all the tools to treat herself, and could recognise when a confrontation needed to be broached. The fear and dread involved in doing so also waned with practice. Her confidence grew. Equally gratifying for her was that the corset of fat that had developed around her middle – the classic fat distribution of long-term cortisol secretion which causes the body to store fat in this way – disappeared without her needing to diet. Lucy’s body had been releasing the hormone cortisol into her system due to the long-term stress she had been under. As we will find out later, there are a number of processes that cortisol changes, including how and where we deposit fat.

I suggested to Lucy that she seek professional help from a psychologist to help her deal further with the issues around her difficult childhood and the anger she had towards her father. For although we had succeeded for now in ridding her of her pain, I was concerned that it would either re-present itself or create a problem somewhere else. She has continued to use the breathing device as it helps her know when she is shifting into a stressed state and it keeps her calm.