‘If your back was on your face you’d look after it.’

– Anon.

I have agonised over how to deal with this contentious subject, partly because it is my particular interest – it is what I have specialised in in my clinical practice – but mainly because it just afflicts so many people. Of the 40 to 50 per cent of the population who suffer with chronic pain, 50 per cent report that it is in their spine.62 The good news is that back pain is much more treatable in all its forms than people think. Even so, it represents a major burden on the state and the health system – not least because it comes in several forms, each requiring its own bespoke recipe of management. There is no single answer for all. Every back problem is unique, because we are.

As I sit here typing, I am mindful of the three lumbar discs in my low back and the three cervical ones in my neck that are currently bulging and have been for several years. Two are pretty worn, to the extent that they have lost 75 per cent of their height and resemble a couple of old radial tyres, like those on the rather tired-looking bike sitting deflated and unused in my garage. I know this because I have been through all the usual rounds of MRI and CT scans, which have shown me sliced and diced in multiple dimensions, like the visual version of a salami machine, and given me amazing insight into the structure and condition of my spine. In fact, I have uploaded some of the images to the computer in my practice, to share with patients, not in a macabre way, but to reassure them that my spine is as bad, if not worse, in imaging terms, than theirs. I have to some extent ‘been there’. In some way, this seems to validate me in their eyes as being experientially as well as professionally qualified to help them.

I do this because I do not want them to become victims of a phenomenon one of my colleagues calls ‘V.O.M.I.T. syndrome’ – Victim of Medical Imaging Technology. This is when patients become so absorbed and affected by what they have been shown on an X-ray or scan that they cannot disconnect from it visually. They begin to behave and live within the confines of what they think it means, rather than what it actually does mean. In my experience, patients are very visually impressionable and when they see the isolated image of a bulging or flattened degenerative disc, it becomes indelibly etched on their minds, particularly if an eminent specialist with letters after his name has reinforced the relevance of the ‘injury’ in worrying terms. Believe it or not, patients tend to feel more worried than reassured if we decide to use imaging. ‘Blimey, he wants to MRI me… there must be something serious going on’ tends to be the sentiment.

So, why do I have all of this imaging of myself? Well, as I wrote in the introduction to this book, I sustained a compression fracture to one of the vertebrae in my low back while playing rugby in my youth. I only discovered this when – the pain having become too much and with a growing weakness in the muscles of my left leg – I finally saw a spinal consultant, who sent me for imaging.

‘Poor chap,’ I hear you say. ‘What agony he must be in!’

Thankfully, but not actually miraculously, I am not. In fact, most of the time I have no pain at all (and I have not needed imaging since). Apart from some occasional stiffness in my muscles, consistent with my life and sporting activities, as well as my age, my life is remarkably pain-free. Basically, I eat well, keep fit and slim, and more importantly, keep my back very strong and flexible. I accept that, like showering, shaving and cleaning my teeth in the morning, it is something I have to do to remain pain-free. I also know and accept that if I am going through a stressful period or sleeping poorly, or both, some of the old aches in my neck and back come home to roost for a while. They have become old friends that tell me all is not well in my world. I know that medication will not help because the pain is old and learned (chronic) rather than due to some new ache or injury.

And then very occasionally I have acute episodes, when my back goes into a rather deformed twist and I am limited in my daily activities, but it settles with time and I use all my little tricks of the trade to hasten its recovery. Each time it has been when I have let my maintenance routine slip for a month or two, mainly due to managing a busy clinical practice, which is very physical and emotional, as well as all my family activities and the stresses that life throws at me.

The human spine is an awesome and miraculous thing. It really is. It offers protection to the spinal cord and brain stem, while providing apertures for the nerves to pass into and out of the body, and multiple points of attachment for the myriad muscles that exert forces on it and enable us to stand erect. It allows multiple ranges of movement and provides the biomechanical base for our limbs to work from: our legs to walk and run; our arms and hands to feed us and operate devices requiring extreme dexterity and accuracy of motion and grip. It is capable of growing, adapting and changing on a daily basis even when you are older, not only in its fine structure but also in its density and strength. To give you some idea of the forces it is capable of withstanding, I have had patients who have undergone scoliosis surgery (to correct extreme developmental curves in the spine) – which involves inserting long titanium alloy rods along the spinal column, attached by screws – and who actually break the rods doing normal daily activities, while the bone those rods are there to support is unharmed. Living bone is strong, malleable and adaptable; ‘plastic’ is the term scientists use.

One myth we need to clear up is that the spine holds us up like a pylon supporting a bridge. It doesn’t; it is much cleverer than that. The spine consists of 33 blocks of bone – the vertebrae – held together in an ‘S’ bend front to back. It is not straight, and in fact, a flat, straight back can have as many problems as a too-curved one. These blocks are held together by a network of tough ligaments that tension it, while also allowing it to move in many directions. The muscles acting on it control the direction and degree of that movement, creating a supporting tension themselves at the same time.

We have two muscle systems: the ones that perform gross movements such as the biceps, which bend your arm at the elbow; and the deeper, more subtle system that fights our greatest enemy as Homo sapiens: gravity. This postural system does not – and cannot – fatigue; otherwise we would fall over. It has the ability to share ‘shifts’ of activity deep within the muscle, so that some fibres switch on while others rest and recover. It can, however, become weak if we sit or are inert for too long in our sedentary working lives and, as it struggles to keep up, we experience this breakdown as a dull ache.

Between the bony blocks are the discs. They are mainly made of cartilage and, amazingly, consist of 60 per cent water. Overnight the discs recover somewhat and imbibe fluid from their environment. They thus slightly reinflate during sleeping hours and so we are technically taller in the morning than in the evening. The cartilage, the annulus fibrosus (a bit like the silicone sealant you use in bathrooms in consistency), is laid down in concentric rings in different directions, much like the radial tyre I described earlier; while the centre of the disc (the nucleus pulposus) is made of a pulpy substance with a consistency similar to toothpaste. In fact, the discs behave at times much like a car tyre, and at others like a chocolate with a soft centre, as you’ll see if you read on…

When a load is applied to the discs, they compress a little, much like a tyre. The rings absorb the load and the soft centre exerts pressure outwards as the cartilage exerts it inwards. There is an equilibrium in pressure and the disc is very strong and stable. But actually most of the bodily pressure is taken up by our core muscles, which provide a corset of cylindrical stability through the abdomen, diaphragm and spinal muscles: in a perfect, athletic spine, very little pressure should be put through the discs. The rest of the large movements of the spine, such as bending, twisting and lifting, are performed by chains of muscles linked all the way from the legs and low back to the upper torso. One of these, the posterior chain, consists basically of the core abdominal muscles, hamstrings, gluteal muscles, deep low back and loin muscles, as well as the laterals, traps and neck muscles.

Each muscular group making up these chains is linked by fascinating stuff called fascia. I guess that makes it ‘fascia-nating’ (sorry!) This can be likened to tough clingfilm, except that it is thick and ungiving. It permeates through the muscle chains and links them to provide tension. It is the membrane stuff you peel off a chicken breast before cooking it.

This whole complex structure works through a system we call tensegrity – integrity through tension. The concept is used in modern engineering for bridges and cranes but nature invented it long before we did.

To get an idea of how it works, look at the image opposite of the child’s toy called a Jacob’s ladder (Figure 5). It consists of a series of wooden tiles joined together by ribbons which weave between them in a snake pattern. The tiles are not glued or stuck in any way but held within the ribbons by tension alone. If you invert one of the tiles it tumbles down the chain but is still held within the ribbons by the tension on them. Magic!

Figure 5: Jacob's Ladder

So, we have to look at the spine as an integrated functional system of support, protection and locomotion. It is self-nourishing and repairing and has all the tools it needs to adapt and heal itself. Evolution has seen to it that there is very little in our bodies that is superfluous to requirements and, indeed, many of the body’s structures fulfil supplementary functions. For example, the diaphragm, the dome-shaped muscle whose primary purpose is to allow us to breathe, has a secondary function of compressing and pumping the stomach and bowel, assisting the mechanical breakdown of food, and aiding the passage of food along the bowel, by pressing down on the stomach wall beneath it. This is borne out in the necessity to strain and hold one’s breath while passing a stool. But let’s not get too graphic. The diaphragm is partly attached to the spine and if it gets very tight from poor breathing it will manifest in locking the spine at that level and causing pain.

This type of dysfunction is what osteopaths, like me, treat all day long. Philosophically, we do not divorce the musculoskeletal system from any other system.

Let’s get trauma out of the way. I have one rule that I teach my students about trauma to the brain, spine, or indeed any bone. If someone reports immediate pain that continues at the same level after a fall or a blow, particularly at night, then it is a fracture until proven otherwise and needs to be imaged, at least X-rayed. This is particularly the case in the elderly and the very young. Old people are brittle and young bones have growth plates and are apt to hide injury within their flexibility. This rule has never let me down and I am only too happy to be wrong.

Obviously, trauma is a particular situation. What I want to look at here is what happens to the vertebral discs, first as a natural process, and then when they get injured.

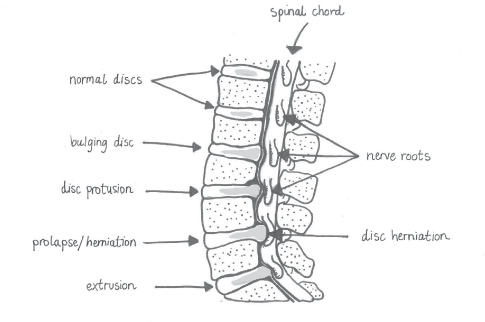

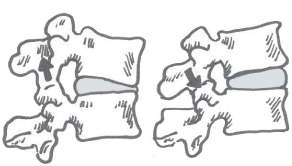

Imagine placing a strawberry-cream-filled chocolate between your thumb and index finger and gently squeezing it so that it slightly flattens but stays intact: that is what happens to a disc when it is loaded or as we get older. The chocolate sides will bulge very slightly. This effect occurs slowly and over time and there is nothing about it that causes acute disturbance of its structure or any neighbouring structure and therefore no inflammatory response is needed. As a result, neither of these events cause pain… ever! So, although they account for about 90 per cent of the bulges you will see in spines on MRI scans, and are often cited as the cause of pain, they are nothing to worry about.

Likewise, as part of a natural and normal process, partly genetic and partly due to time and how much you abuse your back, discs lose their water content and thus become drier. This process can produce micro-cracks within them, again very like an old rubber tyre. Pressure on these cracks creates the potential for bulges to form. This does not matter at the front of the disc as there are no nerves to be irritated. At the back of the disc, the biggest cause of bulges is sitting, because of the uneven pressure put on it, which encourages it to push backwards over time. But even when the discs do bulge significantly, so that they nudge a nerve, if this happens slowly, the nerve can move over and assume a better position. And, unless the patient complains of pain consistent with the distribution of that nerve, it is irrelevant.

I saw a great example of this in a Formula One driver a few years ago while I was working as a human performance advisor to the team. We performed baseline scanning of the drivers’ spines to spot potential problems that might be a risk to them when their bodies were placed under the extreme G-forces of racing. We were gobsmacked to find that one driver had such an enormous disc prolapse in his low back that the path of the nerve was almost indiscernible. Yet he had never complained of any pain in his back or leg. The only reason for this that we could come up with was that the disc, though bulging and distorted, had not actually ruptured, so no inflammatory response had been mounted. Though the nerve was compressed to half its width, it could still move within the hole it exited through, so it was happy. Also, the driver was supremely fit with a very strong core and back.

To ram this home, I want to give you a stat. In 2014, researchers at the famous Mayo Clinic in the US found that disc degeneration was normal at all ages.63 ‘Black’ (which is how they look on MRI scans), dehydrated discs were present in a third of 20-year-olds who had no symptoms at all. It was there in 96 per cent of 80-year-olds, also with no back pain. The Mayo concluded that these findings were not ‘part of a pathological process requiring intervention’ – medical-speak for, ‘if you see them do nothing’.

Back to the chocolate cream. Keep squeezing it until a small crack appears in the bulge but the centre does not actually leak out. That is what we call in the trade a disc (annular) tear with a small herniation (protrusion). These tears can occur suddenly after repetitive straining or lifting (gardening, sweeping), and are often painful, but rarely compress nerves, so the pain stays in the back and does not travel down a leg. This sudden disruption causes inflammation and produces chemicals that irritate the outer layer of the spinal cord and a small network of fine nerves that supply the back of the disc. The tears are visible on a scan, appearing as a ‘lit up’ section within the bulge and telling us that the injury is new and inflamed. There is usually accompanying spasm and a lot of pain, with a barrage of ‘worry’ messages being sent to the brain (nociception). Unfortunately, spinal discs have a very bad blood supply, which means that the tears take longer to heal than in other soft tissues, but they do heal. A bad muscle tear, for example, will take three weeks to heal because it has a rich supply of blood vessels to activate and supply healing cells and nutrients. The average disc tear will take eight to twelve weeks to settle, though, if well managed, most people will see a big improvement after three weeks.

Do they need an MRI?... Nope. Any back specialist worth their salt can work out the nature of the injury from a good case history and clinical examination. As for the treatment, rehabilitation and strengthening of the back and core is vital. But complete immobilisation (bed rest) is a disaster – keeping moving as much as possible is best. We also need to educate the patient not to fear the pain or its recurrence. I am a big fan of helping patients with pain relief in the form of painkillers and anti-inflammatories as it allows them to feel better while nature takes its course. There is evidence that antiinflammatories slow healing, but in my experience not by much, and the patient is happy to forgo a few days of healing if they are in much less pain. I also think that any delay in healing is offset by their ability to keep moving and initiate special exercises. Even more importantly, the quicker you stall or prevent too much nociception (receptors firing into the cord and brain) entering the nervous system, the less likely that this will get established centrally in the brain and become chronic or persistent pain later.

Many patients will respond well to over-the-counter medicines such as ibuprofen but often use them wrongly by taking them only when the pain is bad instead of keeping a constant preventive level of it their bloodstream, which is more effective. Imagine that the tiny dose has to get all the way through your gut and around the body to get to the target tissue and do its thing.

Good manual therapy is also very useful after the first week, but not before. However, chiropractic-style ‘cracking’ at this stage is a no-no and may make it worse. Ultrasound and laser therapy are a complete waste of time for back pain; any perceived improvement is placebo. Of course, some would argue that if the placebo effect results in relief to the patient, why not do it? We will come to that in Chapter 9.

Now, if you overdo it and squeeze the chocolate too hard, the strawberry cream will spill out through the crack in the chocolate. Likewise, when a tear appears in the disc wall, the contents can potentially leak on to and compress the nerves on either side of it, which are very susceptible to irritation and are pain-sensitive. These nerves supply power and sensation to the muscles in the leg. Eighty per cent of these tear injuries occur in one of the two last discs in the low back. The most common symptom is pain in the back of one leg, known as sciatica, though this is a general term.

In most cases, the sciatica too will ease as the immediate inflammation and swelling in the disc settles and the compression retracts. However, this type of nerve pain can be horrendous and really gets to you. And, in my experience, this is when patients are most vulnerable and susceptible to giving into surgery. If their pain is not managed, they will agree to almost anything to get rid of it, only to regret it later. Psychological mood and resilience are very low and sleep is poor. I know; I have been there.

Figure 6. Stages of degeneration of a disc from top to bottom. Believe it or not, most of these will not cause pain if the back and core are kept strong.

Figure 7. Different degrees of disc bulging. Again, all may be pain-free.

If the compression is severe, it interferes with the transmission of impulses in the nerve and will affect sensory perception and be felt as pins and needles or numbness in the distribution of that nerve. In rare cases, the motor fibres to the muscles are affected, with resultant weakness in them. Footdrop, which results in the inability to lift the foot off the ground, is an example of this. It is extremely debilitating and disabling and it is often necessary to operate to remove the disc, as the nerve can be permanently damaged if not relieved quickly.

There is only one other acute necessity for surgery and that is when the disc has effectively herniated so much that it occupies a large section of the canal space which should house the base of the spinal cord. We call it the cauda equina (horse’s tail) because at this level there is no actual spinal cord, only a skein-like bundle of nerve roots. Again, this is very rare but does happen and can cause loss of urinary and bowel function, as well as loss of sensation to the nether regions and erectile dysfunction. Such symptoms require urgent assessment with an MRI scan and a neurosurgeon. Cauda equina syndrome usually happens because the nerves are compressed acutely and without warning. I say this because it is quite common to find, almost incidentally, that patients have compression of the same nerves by slow bony overgrowth into the canal (canal stenosis) equivalent to that of the acute disc. However, they have no symptoms at all. This is because in this case, with time, the nerve roots can adopt a new position and adapt to the squeeze. Here, the scan should be used to confirm the diagnosis only if symptoms develop and based on a good clinical examination.

The other anatomical structure in the spine most commonly involved in back pain is the facet joint (Figure 8 below). Each vertebra is linked by two sets of facet joints. One pair faces upward and one downward. They are located at the back of the spine, and have a flat face, lined with cartilage. They are synovial joints, which means that they can get inflamed and cause pain as they have a membrane around them (the capsule) which is pain-sensitive. This capsule is supplied by a hair-like nerve called the medial branch.

Figure 8. The arrows indicate the facet joints opening and closing with movement.

These joints are easily irritated by repetitive loaded movements, particularly if they are one-sided or asymmetrical or involve rotation, such as in golf and tennis. In the neck, they can become painful from poor posture, working at laptops, overuse of smartphones or sleeping on your front. Over time, they can become arthritic and produce bony spurs, which resemble the edge of an oyster shell. And, if not supported by good surrounding muscles, the joints can become irritated and painful. However, as with discs, on scans we regularly see degenerative joints that are not causing any pain. For me in clinic, the biggest giveaway of facet joint-mediated pain is the associated wasting of the deep spinal muscle also visible on the scan. This usually indicates that a reflex has developed between the pain and the spinal cord that has shut down those muscles as a protective response. Treatment must be aimed at not only settling the irritation of the joints but also ‘waking up’ and dramatically increasing the strength of the affected muscles. Only this will give prolonged relief and prevent recurrence.

The spine needs to be stable in many ranges of movement, including bending and twisting, but equally this is when most injuries occur. This is because most of our daily activities, including a lot of the exercise we do, involve only one plane of movement. The three sports that most commonly set off backs are golf, tennis and football; all of them involve multiple rotation and side-bending, which we do not do all week. Then at the weekend we are surprised when something goes twang when we perform aggressive movements that our backs are not ready for. Often the pain emanates not from a structural injury, but from the brain telling us that our tissues are becoming strained and will potentially get injured. The pain is protective rather than an emergency.

The important thing to take away here is that almost all back pain is avoidable. Being flexible and strong as well as slim and active is vital. Realising that many of the things that you do at work or play involve ‘habit’, in terms of how you use your muscles, is key. Even if you cannot change an action you have to perform, do stretches to prevent muscles you overuse from tightening. Even sitting on a sofa which is offset to the TV will produce neck or low back pain if you constantly have to rotate to face the screen. Similarly, jobs such as working as a cashier in a supermarket or bank often involve reaching and turning while your chair is facing in a fixed direction. Asymmetries in muscle tension can develop and produce pain. So, move either yourself or the screen and stretch as much as possible.

The real problem is that most of us are lazy. I know that sounds harsh but it’s true. Hand on heart, most of us know we do not look after ourselves. We wait for something to happen and react rather than being proactive. Anyone in the world of physical medicine will tell you that getting patients to do what you tell them is the most difficult thing to achieve. Yet they are very quick to complain when it all goes wrong! You have to see yourself as a finely tuned sports car. You can either go on to become an equally tuned vintage car, admired and coveted by all, or end up a rusty old jalopy destined for the crushers. It’s all about maintenance: with just a bit of servicing and a regular polish, the engine will keep firing and work well for its years. You can moan at the boss about desks and ergonomics, but you are driving the car and responsible for it.

At the other extreme, we have the Iron Man-loving, ultramarathon loonies, who shake their joints to bits and push their physiology to the limits for too long. It becomes an obsession that takes over their lives. They come to the clinic and say: ‘It only hurts when I run 20 kilometres, Doc.’ Deep down inside I want to respond: ‘Well, run five and bog off.’ I can only say this because I have been there too. Some years back, I trained fanatically and got to the point where I felt constantly tired, with muscle and joint fatigue, and was too busy training to see my wife and family and ended up with a heart arrhythmia, which I had to have fixed. So, one day, at the end of an ultramarathon, with my body screaming at me, I did a Forrest Gump and just stopped. I looked up at the sky, asked myself who I was proving myself to and whether I was going to wait for my knees to give out before I realised my madness. I threw my trainers in the bin by the finishing line and began to enjoy life once more.

Moderation, as my grandmother always said, is the key to everything.

So, as far as acute pain is concerned, it should be easy to avoid, but do not worry unduly if it happens; in about 85 per cent of cases it will settle down with time and treatment. Very few back problems should ever need to be referred to a specialist, and often that can be a slippery slope to surgery. But do get professional advice from a therapist or doctor and choose someone who knows how to use their hands for manual therapy. And don’t be afraid of short-term medication for pain, as it will help get you moving. Start with the chemist and go to the GP only if the low-level medication is not cutting it.

• If the practitioner wants to use imaging immediately, ask why and what they are looking for. If they can’t provide a reason of concern, they either don’t know what’s going on or they have some other incentive, in which case don’t go back.

• If they don’t examine you, or if they ask you to pay up front, don’t go back.

• If they keep taking X-rays and talking about small alignment issues, don’t go back. You won’t get any better in the long term – and you will end up glowing in the dark!

• There is no such thing as a perfect spine on imaging. It’s the functioning of it that matters.

• If a practitioner is defensive or impatient, they don’t see therapy as a partnership and are not empowering you with knowledge and control. Don’t go back.

• If they tell you: ‘You are lucky not to be in a wheelchair,’ don’t go back.

• If you ask for a second opinion, they should welcome it. If they are correct in their diagnosis, then another professional should agree with them and reassure you that you are with the right person.

• Knowledge is everything and there are some great books out there, many of which are in ‘Further Reading’ at the back of this book.

• Most importantly, as Corporal Jones said in Dad’s Army, ‘Don’t panic!’ It never helps and mostly makes things worse. Pain rarely means serious harm. Breathe and get some help. Call on friends to help. Don’t be a hermit; isolation only makes things worse and depresses you.

• Lastly, unless you are screaming like a banshee, don’t take to your bed. If you absolutely have to, get up every half-hour.

So now the biggy – chronic or, as I prefer to call it, persistent back pain. The one that just doesn’t seem to get better. Incidentally, there is a whole vocabulary around pain and backs that is depressing in its very essence, and I would have an industry-wide change of terminology if I could. Words like ‘chronic’ and ‘degenerative’ should come with a health warning; for me, and most of my patients, they conjure up misery and the ‘beginning of the end’. Radiology reports on X-rays and scans are particularly guilty of this. They use long, complicated and depressing terms to describe findings that are actually quite normal for the age and sex of the patient.

Jeffrey G Jarvik, a marvellously innovative neuroradiologist in the US, once tried an experiment with his report writing. He included a message that read: ‘The following findings are so common in people without low back pain that while we report their presence, they must be interpreted with caution and in the context of the clinical situation.’ 64

Jarvik was surprised to observe on follow-up that the patients whose reports contained his message were significantly less likely to pursue other medical investigations or to have repeated imaging. Furthermore, they were less likely to get follow-up prescriptions for strong medications. Extraordinarily, having understood that the pain did not reflect a dangerous pathological process, they felt confident enough to pursue exercise and other rehabilitative strategies.

One of the things I find astounding about the current chronic pain crisis is that much of the medical world is blissfully unaware of its prevalence. One reason for this is the ‘90/10 rule’, a concept that arose from some research into people with back pain who went to see their doctors. The study found that 90 per cent of the millions of people seeing their doctor each year about back pain recovered on their own within two to three months. People with back pain get better…65

…Or maybe not. Further research in the UK by epidemiologist Peter Croft, director of Keele University’s Primary Care Research Centre,66 showed that this data was highly unreliable. In his estimation, only a quarter of back pain patients recovered within a year. It was true that 90 per cent of them did not return to their doctor within three months but this was not because they had resolved the problem. It was because they had simply given up on primary care as a source of help and moved on to other types of practitioner and interventions. This shows just how much conventional medicine has lost track of the problem.

Pretty much all persistent pain was once acute pain that was simply not treated quickly enough. Almost all of it manifests in soft tissues rather than bone. Most acute pain settles and disappears. However, for some – and it would appear to be a very significant number – that pain undergoes change, and something makes it persist. For us in the medical world working with pain, finding out who those people are, so that we can help prevent the crossing of the Styx into the underworld of suffering, is the key issue.

In many cases, the acute episode is just the straw that breaks the camel’s back. And what really matters is the state that many of us get ourselves into as a backdrop to the episode. One of the major problems that society faces today is that 80 per cent of us sit all day and often for most of the evening, too. Sitting around for most of the day has become as deadly as smoking or obesity. The Lancet medical journal reported that too much sitting increased risk of mortality by 59 per cent. About 5 million deaths globally each year can be attributed to prolonged sitting. This is similar to the level found for obesity and smoking.67

Microbiologist Marc Hamilton at the University of Missouri-Columbia is a researcher into the effects of inactivity, and as he puts it, ‘sitting too much is not the same as exercising too little.’68 This is because when sitting the legs are inactive and we do not use the specialised leg muscles known as the ‘deep red quadriceps’, and there is rapid loss of a vital enzyme that helps remove fat and cholesterol from the bloodstream.

The general and wide-ranging effects of doing nothing are catastrophic in the long term. And in the shorter term, the stasis in our bodies caused by inactivity, as well as the wasting and deconditioning of the muscles in our legs, backs and abdomens, predisposes us to developing pain. How does this happen without us actually injuring ourselves? After all, sitting at a desk can’t tear muscle or strain ligaments. Well, it’s a set of different effects. When people sit, they place three times the pressure through the back of the spinal discs as when they stand and move. Sitting slumped is even worse. Over a prolonged period, bulges develop in the discs and the ligaments, which hold them in, slacken and stretch them. This in itself is not painful, but once the back of the disc is weakened, it is vulnerable to the larger movements we do when we are more active, perhaps playing sports or gardening at the weekend. Add into the pot the weakening of the stabilising system of the spine, the abdomen and back muscles, and it’s a recipe for disaster. Disc injuries can occur acutely as a result, and these will settle, as we have discussed. But most people will be satisfied once the pain has gone and go on living their lives without ever changing how they look after their backs or establishing a regular exercise programme or stretching. And, as the saying goes, if you do what you always do, you will get what you always get. On the other hand, many also believe, quite wrongly, that if they do certain things it will all happen again and so they shut down their activity, thinking it is a protective strategy. The cycle of fear and protection begins.

There are additional effects beyond what happens specifically to the discs. Most of us, as we have discussed earlier, sit racing our engines and going nowhere. We often work under a lot of stress, physiologically producing all the adrenaline-filled normal responses of being chased by a mammoth but not actually acting on it physically. Our bowels shut down, our muscles tense across our entire bodies, without us being aware of it, and our ‘thinking’ brain centres shut down by about 25 to 30 per cent. Pain-firing trigger points pop up in our muscles and seem to spread, which makes us think something much more sinister is going on. Isolated back pain seems to creep to other areas. Over time, our immune systems are impaired, so we get more infection and colds, and inflammation increases, so that our joints and backs hurt more. The changes in our breathing patterns (hyperventilation and breath-holding) produce tension in our necks, which results in headaches and dizziness, and we clench our teeth at night, so that our jaws and craniums ache and we sleep poorly. Consequently, we don’t get good recovery-type sleep. The glass of wine we take to help us drift off into the world of Morpheus only makes things worse, as it prevents the natural wave-like changes between deep and shallow sleep that we need, to rationalise all the day’s events and store memory. Before we know it, we have gone into what I call the Corti-zone.

Once the stress hormone, cortisol, is pumping around us, we store fat in our abdomens. As we put on weight, the increased inflammation generated by the fat causes pain in the back and joints, as well as loading them with more to carry. It also causes cholesterol to line our blood vessels. We seek greater and greater gratification in the form of sugar and other carbohydrates, because we don’t feel good. We may drink caffeine, smoke and vape more to get more dopamine and happy brain chemicals. The short-term effect is outweighed by the stimulants ramping up our pain. Basically, we go into a state of long-term physiological ‘hypervigilance’, which becomes a habit we can’t shake off. We know it is happening as we look in the mirror and see bags around our eyes and pallid skin and wonder at the how the doughnut we had for elevenses has miraculously reformed as a ring around our bellies. For some of us, the lack of control over our lives and the realisation we may never get out of the rut we are in only heighten our anxiety and tension. Our emotionally based limbic and pain systems switch on and we sensitise further to the pain we already feel. Our emotion filter becomes more sensitive and our moods swing randomly. The pain seems to spread and intensify as our brains undergo central sensitisation (the top-down process we talked about in Chapter 1) and even in the periphery our neurones change the receptors on them so that they fire more for less and turn up the neuro-volume knob.

As a result of this, what was a background level of altered state is now escalated by the acute episode. The tsunami wave of pain swamps us and our ‘cope-ability’ is exhausted. We are left in a pain state that does not go away, even though the actual injury has long since healed. Welcome to the world of seemingly interminable back pain, fibromyalgia, IBS, migraine, fatigue and depression. They are all basically the same thing presenting in different ways.

But… before you descend into a black hole of despair and helplessness, if you read back over this chapter, you will realise that it is all changeable, manageable and curable. It’s just about knowing that in order to heal ourselves we need to take steps to change many variables in our lives, not just our workstation. If you make that mindset adjustment and see that it is possible, then it will become entirely more probable. As Frank Vertosick says in his book Why We Hurt: ‘We must try to shed the chains of pain, cloak our souls against the cold, and continue to climb our mountains.’69

I first heard about Pamela from her niece, a patient of mine. Pamela was 80 years old and had been living alone since being widowed 20 years previously. She belonged to that war-time generation, raised on rationing and making-do, for whom independence was an absolute priority. She had never spent a night in hospital in her life. She lived in a bungalow and tended the quarter acre of land surrounding it without any assistance. She frequently did at least the recommended 10,000 steps a day walking her two dogs; and for journeys to the village a mile away, she rode a sit-up-and-beg bike, rather like Miss Marple. Also, like Miss Marple, she spurned wearing a cycle helmet.

The trouble began when a Pilates class started up in the village hall. Pamela went along and enjoyed it at first. But then a local group of yummy mummies joined and started demanding harder exercises. Pamela gamely carried on attending until, after a particularly tough class, she woke in the night with such pain in her low back, pelvis and right leg that she had to phone her son for help. Her GP told her it was her age and prescribed bed rest and strong painkillers, which made her feel anxious and woozy and brought on fears of dementia.

So, Pamela booked an appointment with a chiropractor in the next town. She was initially reassured when the practitioner didn’t dismiss her fears: he took a full medical history and sent her for an X-ray. But when she went back, it was to alarming news. The chiropractor showed her the image of her spine, which Pamela could see was anything but the smooth, straight supportive structure she had in her mind. The chiropractor told her she had scoliosis, bone spurs and herniated discs, which were compressing nerves, and which would get worse if she did not act quickly. With a course of 12 treatments, he promised he would render her pain-free.

Pamela had always been very careful with her money but when she thought of what it would cost her to have someone to do her garden if she couldn’t manage it, 12 treatments seemed like a bargain, so she paid upfront. Sure enough, after 10 sessions she did feel better – though she still got leg pain if she did too much – and she appreciated the interest the practitioner took in her life. But when the course of treatments came to an end, the chiropractor recommended another course as preventive treatment. Luckily, before paying up, Pamela happened to mention this to her niece, who mentioned it to me and asked if I would take a look at her aunt before she handed over any more money.

This I was happy to do. I examined her and took a full case history and established that, prior to the Pilates problem, Pamela had lived an active life that belied her years. So, unless she had randomly experienced a compression fracture or developed some rare disease, which her history told me she had not, the pain had a mechanical or soft-tissue origin. I didn’t go over her X-ray, which she had with her, but said I would look at it later. I didn’t want to reinforce her idea of having a ‘crumbling spine’, as she called it. However, I showed her my own low back X-ray, which, she had to agree, was worse than hers even though she had 30 years on me. Thorough examination confirmed that she had no signs of fracture or nerve compression; in fact, I could get her leg 90 degrees in the air.

Furthermore, she never complained of any pins and needles or numbness, which would correlate with nerve involvement. Hunting for trigger points, I found some scorchers in her hip muscles, which referred pain straight down her leg in the distribution she complained of. These were likely to have been activated by a particular exercise she had been given in Pilates, which had tightened up already overactive muscles.

Gentle treatment to release these trigger points gave her instant relief and I showed her how to work on them herself over the next ten days to further relieve them. I also gave her very specific exercises to wake up some lazy muscles in her hips and legs and to stabilise and strengthen her low back. I advised her to give up not only the chiropractor but also the Pilates for a while, as it had been too generic for her and she needed exercise to be more specific to her personal issues. The class had become too big for the instructor to monitor all the participants. Perhaps she could spend her money on a few one-to-one sessions after I had had a quick chat with the instructor to guide the rehab? We also put her in touch with a t’ai chi class in her area.

As a parting shot, I suggested that if she really wanted to live to be 100, then wearing a cycle helmet might be a good idea, too. Her niece tells me Pamela has taken up t’ai chi and has no pain, but the cycle helmet she bought her hangs unused on the coat peg.