KING SOLOMON’S GOLDEN AGE : HISTORY OR MYTH ?

T he story of the United Monarchy of David and Solomon is one of the greatest epics of western civilization. A young shepherd boy kills the giant Goliath with a single stone slung from his sling, at once saving Israel from the Philistines and becoming western culture’s heroic example of the weak overcoming the mighty. But he then must flee from the rage of King Saul, the first tragic monarch of Israel, who later commits suicide on the battlefield. Conquering Jerusalem, David embarks on an unprecedented campaign of territorial expansion and establishes a great empire. At the height of his fast-rising career, he receives an exceptional, unconditional promise from God: his dynasty will rule in Jerusalem forever.

David’s son and successor, Solomon, has likewise captivated the western literary and religious imagination. His wisdom is the standard by which all rulers are rated. His wealth and opulence were reportedly so great that he became the ideal that countless later kings attempted to emulate.

No wonder that David and Solomon have always been revered in western tradition. From Constantine to Charlemagne, from the “David Throne” of the kings of England through the coronation of the Franks at Reims to the “Crown of Solomon” of the Ottonian kings of Germany, David and Solomon have supplied the greatest monarchs of the world with a model of kingship: pious, wise, courageous, but at the same time capable of moral weakness.

Yet, the question remains, is this great epic historically reliable? What if David and Solomon were, as some scholars now contend, purely legendary characters with no more historical substance than King Arthur or Helen of Troy?

Let me begin at the end. This essay presents “the view from the center.” Against the conservative or maximalist camps, I argue that much of the David and Solomon narrative in the Bible cannot be read as a straightforward historical testimony and that their kingdom was far more modest than traditionally perceived. At the same time, against the so-called minimalists, I contend that David and Solomon are historical figures—the founders of a dynasty based in the Judahite city of Jerusalem.

THE CONVENTIONAL THEORY

The quest for the historical United Monarchy—the glamorous empire of David and Solomon—has been the most spectacular venture of biblical archaeology’s legacy. The obvious place for early scholars to start the search was, evidently, Jerusalem. Yet, Jerusalem proved to be a hard nut to crack. The nature of the site made it difficult to peel away the layers of later centuries and the Temple Mount has always been out of reach for archaeologists.

Therefore, the search for the great United Monarchy of David and Solomon was redirected to other sites; first and foremost among them, Megiddo in the Jezreel Valley. Megiddo is specifically mentioned in 1 Kgs 9:15 as having been built by Solomon. For more than a century now, Megiddo has become the focus of the endeavor to put flesh and bones on the Bible’s literary portrayal of the great Solomonic kingdom. Strategically located on the international highway that connected Egypt and Mesopotamia, Megiddo has been excavated by no fewer than four separate expeditions and, as such, it has yielded more “biblical” monuments than any other site in the Holy Land, including walls, gates, palaces, and water systems, to name but a few.

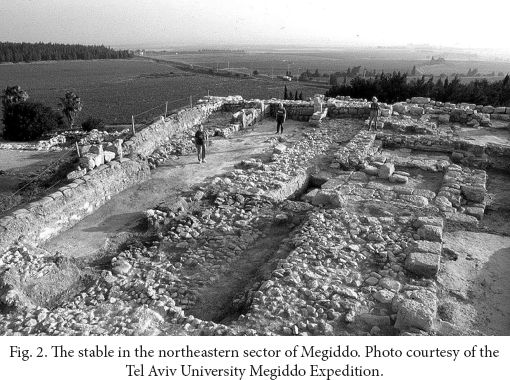

The University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute excavation at Megiddo was the most comprehensive dig in the history of biblical archaeology. Close to the surface of the mound, the excavators unearthed two sets of large public buildings, each divided into three aisles, separated by two sets of stone pillars and troughs. Based on the Megiddo-Solomon linkage in 1 Kgs 9:15 and on the mention in 1 Kgs 9:19 of Solomon’s cities of chariots and horses, P. L. O. Guy, one of the directors of the dig, identified these buildings, now being reinvestigated by a Tel Aviv University-led team, as horse stables, and attributed them to King Solomon (fig. 2 ).

The stables paradigm became the final word and the mirror for the great achievements of Solomon over the next thirty years. The change came with the 1950s excavations of Yigael Yadin farther north at Hazor. Yadin noticed the similarity between the six-chambered city gate that he uncovered at Hazor and the one that the University of Chicago team had unearthed at Megiddo. Yadin turned to 1 Kgs 9:15, which states, “this is the account of the forced labor that King Solomon conscripted to build the house of the Lord and his own house, the Millo and the wall of Jerusalem, and Hazor, and Megiddo, and Gezer,” and decided also to dig Gezer. But he did not excavate the field. Rather, he searched in the old Gezer reports of the British excavations from the beginning of the twentieth century. Indeed, he discovered there a similar city gate hiding in the drawn city plan of what had been formerly described as a “Maccabean castle.” For Yadin this was a perfect match between text and archaeology. Yadin no longer hesitated and so he described all three gates as the “blueprint architecture” of the Solomonic era (fig. 8 ).

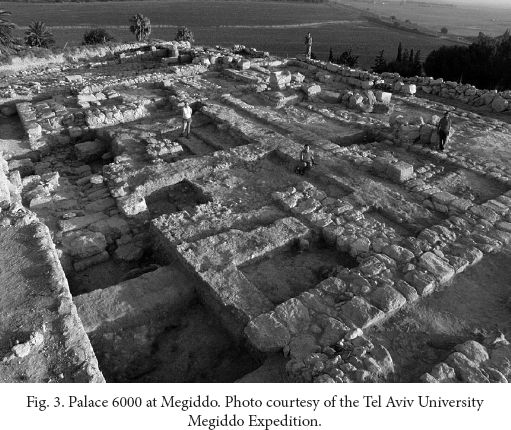

Yadin proceeded to carry out soundings at Megiddo and revised the previous stratigraphy and historical interpretation of the Oriental Institute team. According to him, Solomonic Megiddo was represented not only by the city gate, but also by two beautiful palaces built of ashlar blocks—one discovered by the University of Chicago team in the 1920s (Palace 1723) and the other partially traced by him in the 1960s (and almost fully excavated of recent by the Tel Aviv University-led team; Palace 6000; fig. 3 ). Both buildings were found under the city of the “stables.”

Two more finds at Megiddo seemed to support Yadin’s interpretation: the major city under the city of the palaces—one that still features Canaanite material culture—was destroyed by a terrible fire, and the next city, built on top of the palaces, featured the famous “stables.” Yadin’s interpretation seemed to fit perfectly the biblical testimony:

1. Canaanite Megiddo was devastated by David.

2. The palaces represent the Golden Age of King Solomon; their destruction by fire should be attributed to the campaign of Pharaoh Sheshonq I in the land of Israel, which is mentioned on the walls of the Temple of Amun at Karnak, Upper Egypt, and in 1 Kgs 14:25.

3. The stables (which are later than the palaces) date to the early-ninth century B.C.E. , to the days of King Ahab who, in an Assyrian inscription, is reported to have faced the great Assyrian king Shalmaneser III in Syria with a huge force of two-thousand chariots.

It is no wonder Yadin’s interpretation became the standard theory on the United Monarchy.

WHY THE CONVENTIONAL THEORY IS WRONG

Yet, Yadin’s theory was haunted by severe problems from the outset. First, the city gate at Megiddo seems to have been built later than the gates at Hazor and Gezer; simply put, it connects to a wall that runs over the two palaces. Second, similar city gates have been discovered at other places in the region, among them sites that date to late-monarchic times, centuries after Solomon (for example, Tel ‘Ira in the Beer-sheba Valley and Ashdod on the coast), and sites built outside the borders of the great United Monarchy even as defined by the maximalist view (Ashdod in Philistia and Khirbet Medeineh eth-Themed in Moab). No less important is the fact that all three pillars of Yadin’s theory—stratigraphy, chronology, and the biblical passage—cannot withstand thorough scrutiny. Following is the most pivotal citation from Yadin:

Our decision to attribute that layer to Solomon was based primarily on the 1 Kings passage, the stratigraphy and the pottery. But when in addition we found in that stratum a six-chambered, two-towered gate connected to a casemate wall identical in plan and measurement with the gate at Megiddo, we felt sure we had successfully identified Solomon’s city. (Y. Yadin, “Megiddo of the Kings of Israel,” Biblical Archaeologist 33 [1970]: 67)

Obviously, stratigraphy provides us only with relative chronology—that is, what is earlier and what is later. Unfortunately, the same holds true for old pots. In the case of pottery, archaeologists have committed the ultimate mistake. Some scholars argue that the Solomonic strata at Megiddo, Hazor, and Gezer were dated according to a well-defined family of vessels—red-slipped and burnished ware—which dates to the tenth century. Following is a citation from William G. Dever:

The pottery from this destruction layer included distinctive forms of red-slipped … and hand burnished pottery, which have always been dated to the late tenth century…. Thus, on commonly accepted ceramic grounds—not on naive acceptance of the Bible’s stories—we dated the Gezer walls and gates to the mid-to-late tenth century. (W. G. Dever, What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It? [Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 2001], 132)

The opposite is true. Dever dated this pottery to the tenth century because it had been found in the so-called “Solomonic strata.” In other words, how does Dever know that these strata were constructed by Solomon? From the Bible—another classic case of circular reasoning.

So, we are back to square one. Yadin’s stratigraphy and chronology tell us nothing when it comes to absolute dating. In order to reach a date, we need an archaeological find that would anchor the archaeology of Israel to the securely dated monarchs of Egypt and Assyria. The problem is that no such anchor for the tenth century B.C.E. exists. In fact, there is no such anchor for the entirety of the more-than-four-centuries of the Iron Age that span the mid-twelfth to the late-eighth centuries B.C.E.! The fragment of the Sheshonq I stele found in the 1920s at Megiddo could have given us such an anchor, but unfortunately, it was recovered out of context. The same holds true for the Mesha stele from Dibon in Moab (in modern Jordan) and the Hazael inscription from Tel Dan in northern Israel. This means that the connection between the remains in the ground and the historical sequence is based on one’s interpretation of the biblical material. Hence, Yadin’s theory relied on the biblical verse, 1 Kgs 9:15, and nothing but the biblical verse. This must be made clear: the entire reconstruction of the great Solomonic state—by Yadin as well as by others—has been based on a single biblical verse.

So we should take a close look at this verse. There is no question that the material in the books of Kings was put in writing not earlier than the late-seventh century B.C.E. , three centuries after Solomon, and that its description of the United Monarchy paints a picture of an idyllic golden age, one that is wrapped in the theological and ideological goals of the time of the authors. Is it possible that despite all this, the author did know about Solomon’s building activities in the north? The commonsensical answer would be that he could have consulted with a Solomonic archive in Jerusalem. But over a century of archaeological investigations in Judah has failed to reveal any meaningful scribal activity before the late-eighth century. The idea of a Solomonic archive is therefore no more than wishful thinking. If this is the case, how should we understand 1 Kgs 9:15? I would argue that the author referred to the three most important lowland cities of the Northern Kingdom in the eighth century B.C.E. , namely, Megiddo, Hazor, and Gezer, in order to justify his own pan-Israelite ideology that the great Solomon ruled from Jerusalem over the entire country including the lands of the Northern Kingdom (though in the writer’s time, the North had already been destroyed).

To sum up this point, Yadin’s stratigraphy and pottery tell us nothing at all as regards a United Monarchy and the biblical verse can tell us nothing about the days of Solomon. As far as I can judge, the conventional theory rests on a somewhat simplistic reading of the biblical text, the importance of which has been magnified by wishful thinking.

Now, there are many more reasons to reject the conventional theory. It raises severe historical and archaeological problems. Following are three examples:

1. The rise of territorial states in the Levant was an outcome of the westward expansion of the Assyrian Empire in the early-ninth century B.C.E. Indeed, extra-biblical sources leave little doubt that all major states in the region, namely, Aram-Damascus, Moab, Ammon, and northern Israel, emerged in the ninth century B.C.E. It is extremely difficult to envision a great empire ruled from the marginal region of the southern highlands a century before this process.

2. Affiliating the destruction of the Megiddo palaces with the campaign of Pharaoh Sheshonq I leaves us with no destruction layers in the north for the well-documented later assault of Hazael, king of Aram-Damascus, on the Northern Kingdom in the mid-ninth century.

3. Most problematic of all is the fact that over a century of archaeological explorations in Jerusalem—the capital of the glamorous biblical United Monarchy—has failed to reveal evidence for any meaningful tenth century building activity. The famous Stepped Stone Structure—usually presented as the most important archaeological remnant of the United Monarchy—was probably built later (fig. 6 ). Pottery that dates to the ninth century, if not later, was found between its courses. The excavator has interpreted the foundations of a building recently unearthed on the ridge of the City of David above this structure as the remains of the palace of King David. But a careful examination of the architecture and the finds indicates that this building should be dated to the later phase of the Iron II, if not later. The common pretext for the absence of tenth-century remains in Jerusalem—that they were eradicated by later activity—should be brushed aside. Monumental fortifications from both the Middle Bronze Age and late-monarchic times (that is, the sixteenth and eighth centuries B.C.E. respectively) did in fact, survive later occupations. To make a long story short, tenth-century Jerusalem—the city of the time of David and Solomon—was no more than a small, remote highlands village, and not the exquisitely decorated capital of a great empire.

AN ALTERNATIVE THEORY

So much for the negative evidence; more straightforward clues as to the appropriate dating of finds come from two sites related to the great Omride dynasty, which ruled over the Northern Kingdom in the ninth century—Samaria in the highlands, its capital, and Jezreel in the valley, generally considered to be its winter palace.

Ashlar blocks uncovered in the foundations of one of the so-called Solomonic palaces at Megiddo preserve distinctive masons’ marks on their surfaces. Such marks have been found only in one other building in Israel, namely, the ninth-century palace of Omri and Ahab at Samaria. I should stress that we are not speaking about two sites, or two strata, but about two buildings! These masons’ marks are so distinctive that they must have been executed by the same group of masons. Yet, one palace was dated to the tenth century and the other to the ninth century B.C.E. There are only two alternatives here: either we push the Megiddo building ahead to the ninth century, or we pull the Samaria palace back to the tenth century. The answer to the riddle lies in the biblical source on the building of Samaria by King Omri of Israel. This source must be a reliable one since it is supported by Assyrian texts that refer to the Northern Kingdom as bit omri , that is, the “House of Omri,” the typical phraseology employed when referring to a state that had been named after the founder of its capital. Therefore, there is hardly any doubt that down-dating the Megiddo palaces to the ninth century is the only option.

The recent Anglo-Israeli excavations at Jezreel, located less than ten miles to the east of Megiddo, revealed equally surprising results. The destruction layer of the royal compound there, dated to the mid-ninth century B.C.E. , yielded a rich collection of vessels identical to a Megiddo assemblage that has conventionally been dated to the late-tenth century B.C.E. Again, we need either to push the Megiddo assemblage ahead or to pull the Jezreel one back. Since the Jezreel compound is architectonically identical to that of Samaria, it must date to the ninth century. In this case too, then, there is only one option: one must down-date the Megiddo palaces to the ninth century B.C.E.

So far I have dealt with traditional archaeology and biblical exegesis. Can we add to these circumstantial considerations a more accurate method? The answer is positive and it comes from the exact sciences. In recent years, samples from Iron Age strata of several sites in Israel have been subjected to 14 C dating procedures. The resultant dating of a large number of readings from Dor on the Mediterranean coast, Tel Hadar on the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee, Megiddo, and Yoqne‘am in the Jezreel Valley, Tel Rehov south of Beth-shean, Hazor in the north, and Rosh Zayit near Acco were found to be lower than expected by almost a century according to the conventional chronology. A comprehensive study by the Weizmann Institute and the University of Arizona laboratories has placed the transition from the Iron I to the Iron II, which is traditionally dated from around 1000–980 B.C.E. to 920–900 B.C.E. Destruction layers, which have conventionally been dated to the late-tenth century, provide dates in the mid- to late-ninth century B.C.E.

A set of readings from Tel Rehov has been interpreted by Amihai Mazar as supporting the conventional dating. Yet, a more thorough reading of the Tel Rehov radiocarbon data (that is, taking into consideration all readings rather than a selection of results) can be interpreted as supporting the down-dating of the Iron Age strata (that is, the Low Chronology). In addition, comparison of the pottery assemblages of Tel Rehov and Megiddo indicates that the Megiddo palaces should be placed in the later phase of the period labeled “Iron IIA,” that is, in the first half of the ninth century B.C.E.

In sum, the radiocarbon results confirm my earlier conclusions: the date of the “Solomonic” monuments should be lowered by seventy-five to one-hundred years.

BACK TO HISTORY

What is the meaning of all this for biblical and historical studies? The mention of the “House of David” in the Tel Dan inscription from the ninth century B.C.E. leaves no doubt that David and Solomon were historical figures. And there is good reason to accept that many of the David stories in the books of Samuel—mainly the heroic tales and the description of his life as a bandit on the fringe of the Judean highlands—contain genuine, early historical memories. These in turn were transmitted orally and put in writing not before the late-eighth century B.C.E. But the great biblical story of the United Monarchy is left with no material evidence. In the tenth century B.C.E. , places such as Megiddo in the north still featured Canaanite material culture. The kingdom of David and Solomon was no more than a poor, demographically depleted chiefdom centered in Jerusalem, a humble village.

The beautiful Megiddo palaces—until recently the symbol of Solomonic splendor—date to the time of the Omride dynasty of the Northern Kingdom, almost a century later than Solomon. They were probably constructed by King Ahab. This should come as no surprise. Contemporary monarchs—Shalmaneser III of Assyria, Mesha of Moab, and Hazael of Damascus—all attest to the great power of ninth-century Israel. The biblical story about the reign of the Omride princess Athaliah in Jerusalem, which is widely considered to be a reliable historical testimony, indicates that the Omrides dominated the marginal, powerless Judah to their south. The great, powerful, and glamorous Israelite state was the Northern Kingdom—the wicked kingdom in the eyes of the biblical historians—not the small and poor territory dominated by tenth-century Jerusalem. If there was a United Monarchy that ruled from Dan to Beer-sheba it was that of the Omride dynasty and it was ruled from ninth-century Samaria.

If these are the facts on the ground, what is the origin of the biblical tale of an illustrious United Monarchy? In order to answer this question, we need to remember that the biblical narrative of the ancient history of Israel—the Deuteronomistic History—was put in writing in the late-seventh century B.C.E. , in the days of King Josiah, who is described in the book of Kings as the most righteous monarch of the lineage of David. The Deuteronomistic History was intended to serve Josiah’s agenda of centralization of the cult in Jerusalem and territorial expansion into the northern lands of vanquished Israel after the withdrawal of Assyria. It is not difficult to identify the landscapes and costumes of late-monarchic times—the time of the compilation of the text as well as the immediate past—as the stage setting behind the biblical tale of the United Monarchy. The stories of Solomon’s cities of chariots and horsemen must reflect a memory of the great horse-breeding and training facilities of the Northern Kingdom in eighth-century B.C.E. Megiddo. King Hiram of Tyre must be identified with the only Hiram known from reliable extra-biblical texts—the contemporary of Tiglath-pileser III in the eighth century; the story of the trade relations with him was designed to equate the grandeur of Solomon with that of the great monarchs of the Northern Kingdom. The lavish visit to Jerusalem of Solomon’s trading partner, the Queen of Sheba, undoubtedly reflects the participation of late-eighth and seventh-century Judah in the lucrative Arabian trade under Assyrian domination. The same holds true for the description of the trade expeditions to lands afar that set off from Ezion-geber on the Gulf of Aqaba—a site that was not inhabited before late-monarchic times.

As I have mentioned, some of the David stories in the books of Samuel may contain earlier, even tenth-century B.C.E. traditions. But they too had been put in writing much later, possibly in the late-eighth century, and were then inserted into the larger history of Israel in the seventh century. At that stage, they absorbed the realities and ideology of the later time. The armor of Goliath, for instance, which resembles that of a Greek hoplite of the seventh or sixth century B.C.E. (and not an early Aegean warrior), should probably be understood against the background of the service of Greek mercenaries in the army of seventh-century Egypt. That was a time when tiny Judah faced mighty Egypt of the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, which inherited the Assyrian territories in the Levant. So, the victory of David over the giant Goliath—described as a Greek hoplite and thus symbolizing the power of Egypt—could have depicted the hopes of Judah in Josiah’s time.

But why was it so important to project these late-monarchic images back into the early history of Israel? The tale of a glamorous United Monarchy had an obvious meaning for the people of Judah in the days of the compilation of the text. In a time when the Northern Kingdom was no more than a memory and the mighty Assyrian army had faded away, a new David—the pious Josiah—came to the throne in Jerusalem, intent on “restoring” the glory of his distant ancestors. He was about to “replay” the history of Israel. By cleansing Judah of the abominations of the nations and undoing the sins of the past, he could stop the cycle of idolatry and calamity that characterized the history of ancient Israel. He could “recreate” the United Monarchy the way it should have been, before it went astray. So Josiah embarked on reestablishing a United Monarchy. He was about to “regain” the territories of the now-destroyed Northern Kingdom, and rule from Jerusalem over all Israelite territories and all Israelite people. The description of the glamorous United Monarchy served these goals.

While all this may seem somewhat to belittle the stature of the historical David and Solomon, in the same breath we gain a glimpse into the grandeur of the Northern Kingdom—the first true, great Israelite state. No less important, we are given a glimpse into the fascinating world of late-monarchic Judah whose authors created the image of the great United Monarchy.