JAMES MARSHALL’S DISCOVERY OF GOLD along the American River near Sacramento in January 1848 precipitated an influx of immigrants from all over the world to California in search of promised wealth. Rumors of gold began circulating soon after Marshall took his find to John Sutter at Sutter’s Fort, where the two confirmed, to the best of their knowledge, that the metal was indeed gold. Sutter tried to keep the discovery secret, but word soon traveled, carried by teamsters delivering goods to Coloma, among others. Although announcements appeared in San Francisco papers by mid-March, it was not until 12 May, when Samuel Brannan—who operated a store at Sutter’s Fort—arrived in San Francisco, a bag of gold dust in hand and shouting: “Gold! Gold! Gold from the American River!” that workers abandoned their jobs to head for the Sierra foothills.1 When ore samples reached Monterey the following month, “the blacksmith dropped his hammer, the carpenter his plane, the mason his trowel, the baker his loaf, and the tapster his bottle.”2 Gold fever spread quickly, first to towns throughout California. Soon immigrants from Mexico and Chile, pioneers who had traveled west to Oregon, and local Native Americans were all prospecting along streams traversing the Sierra Nevada from the Yuba River in the north to the Mokelumne in the southern Sierra.3 On the East Coast of the United States the first reports were received with skepticism and a suspicion that the so-called discovery was a ruse to entice American settlers to isolated outposts in the Far West.4

Less than two weeks after Marshall spotted gold in his millrace, Mexico transferred vast holdings in the Southwest, including all of California, to the United States by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. At the time, Spanish-speaking Californios accounted for half or more of the estimated ten thousand people, excluding Native Americans, residing in the area. Among the rest were recent American immigrants and Russian and British traders and trappers.5

By the fall of 1848, reports and samples of the gold submitted by Governor Richard Mason and Lieutenant Edward F. Beale reached Washington. With this evidence, President James K. Polk announced the discovery in his annual address to Congress, stimulating thousands of Americans to make plans to set out to seek their fortunes.6 Whether by sea (at first around Cape Horn, and later across the Isthmus of Panama) or overland (after spring snowmelt so stock could feed on grass and before winter storms made the Sierra impassable), the arduous journeys demanded considerable energy and expense. Most travel would take five or six months, and would-be miners—of diverse ages, but overwhelmingly male—frequently had to borrow money from friends and family, forming investment companies to underwrite their enterprise. Nonetheless, most of the Argonauts—a name adopted by the miners and their contemporaries in acknowledgment of the adventure they were undertaking—saw themselves as sojourners in California, intending to reap their rewards quickly and return home.

Overland travel terminated at Sierra mining sites. From about mid-1849 on, ships carrying gold-seekers from the East Coast arrived en masse in San Francisco harbor. They joined vessels from Europe, where accounts of the gold discovery were received amidst food shortages and widespread political turmoil. Aspiring miners were coming from as far away as Australia and China, acquiring essential supplies—often at exorbitant prices—and heading to the mines, weather permitting. By the end of 1849, as a result of this unprecedented international migration, California’s population had swelled tenfold.7

Before the Gold Rush, settlers from the East and Midwest—where the Swiss-born Sutter had stopped as well—had been arriving in California for some time, but the challenges of the overland trek and Mexico’s refusal to allow noncitizens to hold title to property had kept their numbers small. Nonetheless, by 1846, there was a growing American and European presence in California; Sutter could envision establishing a community, to be called Sutterville, close to the fort he commanded near the confluence of the Sacramento and American rivers, on property granted him by the Mexican government in 1839. In August 1847 he contracted with James Marshall to build a sawmill at Coloma.8

Despite increasing immigration and intrigues between Mexican and American political factions, there is scant visual record of California in the months preceding the gold discovery.9 With the arrival of the Argonauts, however, an outpouring of watercolors, drawings, and ambitious oil paintings documented and interpreted the Gold Rush locales, participants, and activities. Unlike earlier immigrants—and previous waves of settlement in the United States spearheaded by would-be farmers—miners flocking to California generally came without their families and were trained in diverse occupations; among them were artists and writers, merchants, machinists, shoemakers, and silversmiths.10 That many sought to bring some aspects of the cultivated surroundings they had left behind into their new lives is reflected in accounts that describe musical ensembles formed at sea by miners who brought their instruments with them, and the popularity of traveling theater troupes in Gold Rush communities large and small.11 The miners’ awareness that they were participating in a historical event and the exotic character of their undertaking stimulated them to record both the everyday and the exceptional events they encountered. Enforced inactivity, when winter rains precluded mining, may also have encouraged their artistic pursuits.

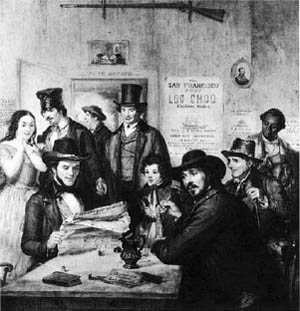

Few views of the Gold Rush were produced by established East Coast artists of the day (William Sidney Mount’s California News [fig. 2] is a notable exception), but a number of capable painters traveled west. Many were lured to California—as were their colleagues—expecting success in the diggings, and returned to their original occupations only when wealth in the placers eluded them. Other painters and illustrators embarked for California for different reasons: the adventure itself, a desire to make money by publishing accounts or creating panoramas for audiences in Europe or the East, or to pursue careers in new communities that had fewer restrictions and less competition. Whatever their motives in joining the California Gold Rush, the painters and draftsmen (some with the advantage of art school training, and others apparently self-taught) created engrossing images of the scenery, people, and activities around them. The results were often satisfying accomplishments of artistic merit, as well as compelling, firsthand documents of their remarkable ventures. In images ranging from casually rendered drawings of mining-camp scenes to large oil paintings commissioned by patrons, artists such as William Smith Jewett, Charles Christian Nahl, A. D. O. Browere, and others created a visual legacy of the Gold Rush. Their images were important in providing information about California and life at the time and in crafting representations of local notables. The paintings and drawings were exhibited in the East and translated into lithographs for international distribution. Along with written accounts—including letters and journals—and daguerreotypes, their efforts afford viewers today a significant understanding of the natural resources, economic changes, and cultural development that distinguished the Gold Rush in California. Art of the Gold Rush explores only part of that vast visual legacy. The focus of the exhibition—and thus of this book—is on original works of art, selected because they represent particular themes and for their high artistic quality.

FIG. 2. William Sidney Mount, California News, 1850. Oil on canvas, 21½ × 20¼ in. Museums at Stony Brook, New York, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ward Melville.

Like other American art of this period, images of the Gold Rush were created almost exclusively by men of European descent who brought their perceptions and the technical conventions in which they were trained (generally in the East or Europe) to their representations of new subjects. What they chose to depict and how their motifs were presented embody the cultural biases of a subset of the thousands of people from throughout the world who participated in the event. Only a small percentage of the paintings, watercolors, and drawings created during this remarkable time survives today. Fires that swept through San Francisco (including the devastating blaze that followed the earthquake in 1906) destroyed many works; others were lost to various natural calamities or to carelessness. Examples of Gold Rush painting are therefore rare and prized, and only incompletely document the exceptional outpouring of artwork that characterized this period. Nonetheless, the art of the Gold Rush contributes significantly to our understanding of both American culture and its interpreters during the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

What we have documents rapidly changing events that had an ongoing impact on California. Even in the initial months of mining, conditions and technologies changed dramatically. We can date drawings and paintings with some certainty from depictions of mining tools or the types of operations. Artists arrived in successive waves and made their way to the mines by various routes. When passage across Panama via the Chagres River gained popularity over the trip around the Horn, for instance, representations of Panama’s verdant tropical landscape become abundant. Nostalgia for the recent past set in quite early. By the mid-1850s, artists such as A. D. O. Browere were producing romanticized paintings that showed earlier—rather than current—Gold Rush practices (see figs. 65 and 74). Artists also responded to an evolving audience for their work. Most of their earliest productions were realized as prints or illustrations, but by 1850 large oil paintings, such as E. Hall Martin’s Mountain Jack and a Wandering Miner (fig. 1) or William Smith Jewett’s The Promised Land (fig. 33) were also in demand. Little information survives about art patronage of this period, but it is clear that changes were taking place. And, although the Gold Rush is considered to have spent itself by 1854, artists continued to arrive in California, to explore both the possibilities of mining and the state’s other attractions.

Contrary to the perception that portraits dominated early Gold Rush art, scenes of developing cities and mining sites are well represented in drawings and watercolors in 1849 and early 1850 (see Augusto Ferran’s Vista de San Francisco [fig. 13] and Harrison Eastman’s watercolor Saint Francis Hotel [fig. 18]). Late in 1849, one of the earliest known public displays of artwork in San Francisco consisted of scenes sketched “in all parts of California” by William Cogswell, who planned “to take these to the eastern states to show graphically and truly California scenes, men, and women.”12 Landscape figures prominently in William McIlvaine’s sumptuous watercolors (figs. 14 and 15), although they also contain elements of genre painting—scenes of everyday life—in their depiction of mining and camp life.

There was a growing taste for genre painting among the American public by midcentury, and Argonauts engaged in mining tasks assume prominent roles in some of the large canvases being produced at this time, among them Martin’s images of prospectors, and in scenes such as The Lone Prospector by A. D. O. Browere (fig. 61). The ambitious scope of such compositions suggests that, although San Francisco boasted few artistic resources in the early 1850s (Benjamin Parke Avery noted that few examples of European painting were available),13 patronage was growing and a community of artists was beginning to develop.

Nonetheless, the First Industrial Exhibition of the Mechanics’ Institute in 1857 was the initial opportunity afforded to artists in San Francisco to show their work to the public—and view the accomplishments of their colleagues—on a large scale. The dominance of portraiture among the offerings was duly noted in the catalogue, with the statement that “the luxuries of painting can only follow the introduction of wealth-creating improvements, and it cannot be expected at this epoch of development of arts in California that the talents of artists in this class will be duly encouraged.”14 Within a few years, however, several artists of stature were attracted by the state’s magnificent landscape and moderate climate, as well as by the prosperity that followed in the wake of the Gold Rush. By 1863, when Samuel Marsden Brookes, Thomas Hill, and Virgil Williams were among the resident artists, and Albert Bierstadt first visited the state, John S. Hittell could make the following assessment:

Art does not flourish usually in new countries. The proportion of rich families is small; and most of the rich, having become suddenly wealthy, are unaccustomed to frequent contemplation of fine pictures, have not taste, and perhaps cover their walls with miserable daubs. We could not expect therefore that art would more than exist in California, . . . But it does exist.15

Artists participated in the Gold Rush in various ways. Some arrived in California, proceeded to travel through the mining communities, responding to the views and activities they witnessed, and soon returned home. Some, such as Martin and Thomas A. Ayres, succumbed to the diseases or dangers that cut short the lives of many Forty-niners. Others established studios in Sacramento or San Francisco, found markets for their work, and became long-term residents who contributed to the development of Northern California as a major regional art center later in the century.

FIG. 3. Thomas A. Ayres, San Francisco Bay, 1851. Watercolor, gouache, and pencil on paper, 6¾ × 6¾ in. Oakland Museum of California, gift of the Reichel Fund.