| CHAPTER |

|

| 5 |

Security Policies, Standards, Procedures, and Guidelines |

| |

|

The four components of security documentation are policies, standards, procedures, and guidelines. Together, these form the complete definition of a mature security program. The Capability Maturity Model (CMM), which measures how robust and repeatable a business process is, is often applied to security programs. The CMM relies heavily on documentation for defining repeatable, optimized processes. As such, any security program considered mature by CMM standards needs to have well-defined policies, procedures, standards, and guidelines.

• Policy is a high-level statement of requirements. A security policy is the primary way in which management’s expectations for security are provided to the builders, installers, maintainers, and users of an organization’s information systems.

• Standards specify how to configure devices, how to install and configure software, and how to use computer systems and other organizational assets, to be compliant with the intentions of the policy.

• Procedures specify the step-by-step instructions to perform various tasks in accordance with policies and standards.

• Guidelines are advice about how to achieve the goals of the security policy, but they are suggestions, not rules. They are an important communication tool to let people know how to follow the policy’s guidance. They convey best practices for using technology systems or behaving according to management’s preferences.

This chapter covers the basics of what you need to know about policies, standards, procedures, and guidelines, and provides some examples to illustrate the principles. Of these, security policies are the most important within the context of a security program, because they form the basis for the decisions that are made within the security program, and they give the security program its “teeth.” As such, the majority of this chapter is devoted to security policies. There are other books that cover policies in as much detail as you like. See the References section for some recommendations. The end of this chapter provides you with some guidance and examples for standards, procedures, and guidelines, so you can see how they are made, and how they relate to policies.

Security Policies

A security policy is the essential foundation for an effective and comprehensive security program. A good security policy should be a high-level, brief, formalized statement of the security practices that management expects employees and other stakeholders to follow. A security policy should be concise and easy to understand so that everyone can follow the guidance set forth in it.

In its basic form, a security policy is a document that describes an organization’s security requirements. A security policy specifies what should be done, not how; nor does it specify technologies or specific solutions. The security policy defines a specific set of intentions and conditions that will help protect an organization’s assets and its ability to conduct business. It is important to plan an approach to policy development that is consistent, repeatable, and straightforward.

A top-down approach to security policy development provides the security practitioner with a roadmap for successful, consistent policy production. The policy developer must take the time to understand the organization’s regulatory landscape, business objectives, and risk management concerns, including the corporation’s general policy statements. As a precursor to policy development, a requirements mapping effort may be required in order to incorporate industry-specific regulation.

Chapter 3 covered several of the various regulations as well as best practice frameworks that security policy developers may need to incorporate into their policies.

NOTE The regulatory landscape includes U.S. federal and state laws regarding data and personal privacy, European laws restricting what organizations can do with personal data, laws from other countries that must be followed when an organization does business there, and industry-specific standards. All relevant regulations must be incorporated into the policy development objectives.

A security policy lays down specific expectations for management, technical staff, and employees. A clear and well-documented security policy will determine what action an organization takes when a security violation is encountered. In the absence of clear policy, organizations put themselves at risk and often flounder in responding to a violation.

• For managers, a security policy identifies the expectations of senior management about roles, responsibilities, and actions that should be taken by management with regard to security controls.

• For technical staff, a security policy clarifies which security controls should be used on the network, in the physical facilities, and on computer systems.

• For all employees, a security policy describes how they should conduct themselves when using the computer systems, e-mail, phones, and voice mail.

A security policy is effectively a contract between the business and the users of its information systems. A common approach to ensuring that all parties are aware of the organization’s security policy is to require employees to sign an acknowledgement document. Human Resources should keep a copy of the security policy documentation on file in a place where every employee can easily find it.

Security Policy Development

When developing a security policy for the first time, one useful approach is to focus on the why, who, where, and what during the policy development process:

1. Why should the policy address these particular concerns? (Purpose)

2. Who should the policy address? (Responsibilities)

3. Where should the policy be applied? (Scope)

4. What should the policy contain? (Content)

For each of these components of security policy development, a phased approach is used, as discussed next.

NOTE Executive management’s involvement and approval will be required. But initially, the executives may not understand the subject matter. As the policy developer works through the policy development process, gaining executive-level buy-in, feedback, and approval at each stage is useful in garnering support for the security program. This is a good opportunity to correlate executive management’s business requirements and concerns, regulatory requirements, and standards guidance to security policy components.

Phased Approach

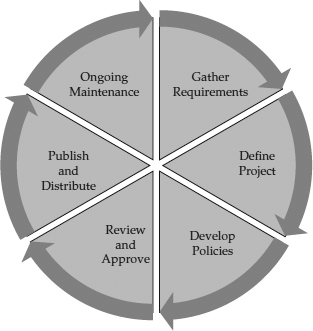

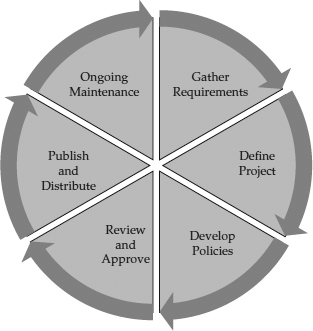

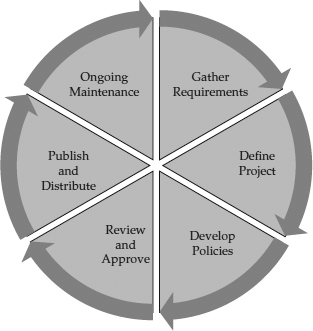

If you approach security policy development in the following phases, depicted in

Figure 5-1, the work will be more manageable:

Figure 5-1 Security policy development process

1. Requirements gathering

• Regulatory requirements (industry specific)

• Advisory requirements (best practices)

• Informative requirements (organization specific)

2. Project definition and proposal based on requirements

3. Policy development

4. Review and approval

5. Publication and distribution

6. Ongoing maintenance (and revision)

After the security policy is approved, standards and procedures must be developed in order to ensure a smooth implementation. This will require the policy developer to work closely with the technical staff to develop standards and procedures relating to computers, applications, and networks.

Security Policy Contributors

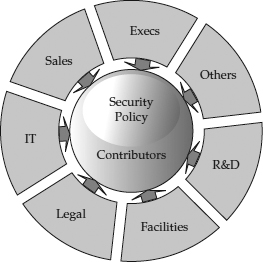

Security policy should not be developed in a vacuum. A good security policy forms the core of a comprehensive security awareness program for employees, and its development shouldn’t be the sole responsibility of the IT department. Every department that has a stake in the security policy should be involved in its development, not only because this enables them to tailor the policy to their requirements, but also because they will be responsible for enforcing and communicating the policies related to each of their specialties. Different groups and individuals should participate and be represented in order to ensure that everyone is on board, that all are willing to comply, and that the best interests of the entire organization are represented.

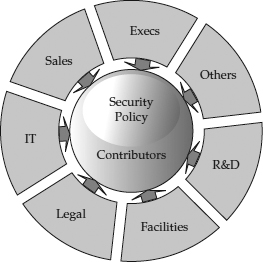

Figure 5-2 shows some example contributors to the security policy.

Figure 5-2 Example of security policy contributors

When creating a security policy, the following groups may be represented:

• Human Resources The enforcement of the security policy, when it involves employee rewards and punishments, is usually the responsibility of the HR department. HR implements discipline up to and including termination when the organization’s policies are violated. HR also obtains a signature from each employee certifying that they have read and understood the policies of the organization, so there is no question of responsibility when employees don’t comply with the policy.

• Legal Often, an organization that has an internal legal department or outside legal representation will want to have those attorneys review and clarify legal points in the document and advise on particular points of appropriateness and applicability, both in the organization’s home country and overseas. All organizations are advised to have some form of legal review and advice on their policies when those policies are applied to individual employees.

• Information Technology Security policy tends to focus on computer systems, and specifically on the security controls that are built into the computing infrastructure. IT employees are generally the largest consumers of the policy information.

• Physical Security Physical Security (or Facilities) departments usually implement the physical security controls specified in the security policy. In some cases, the IT department may manage the information systems components of physical security.

Security Policy Audience

The intended audience for the security policies is all the individuals who handle the organization’s information, such as:

• Employees

• Contractors and temporary workers

• Consultants, system integrators, and service providers

• Business partners and third-party vendors

• Employees of subsidiaries and affiliates

• Customers who use the organization’s information resources

Figure 5-3 shows a representation of some example security policy audience members.

Figure 5-3 Security policy audience

Technology-related security policies generally apply to information resources, including software, web browsers, e-mail, computer systems, workstations, PCs, servers, mobile devices, entities connected on the network, software, data, telephones, voice mail, fax machines, and any other information resources that could be considered valuable to the business.

Organizations may also need to implement security policy contractually with business partners and vendors. They may also need to release a security policy statement to customers.

Policy Categories

Security policies can be subdivided into three primary categories:

• Regulatory For audit and compliance purposes, it is useful to include this specific category. The policy is generally populated with a series of legal statements detailing what is required and why it is required. The results of a regulatory requirements assessment can be incorporated into this type of policy.

• Advisory This policy type advises all affected parties of business-specific policy and may include policies related to computer systems and networks, personnel, and physical security. This type of policy is generally based on security best practices.

• Informative This type of policy exists as a catch-all to ensure that policies not covered under Regulatory and Advisory are accounted for. These policies may apply to specific business units, business partners, vendors, and customers who use the organization’s information systems.

The security policy should be concise and easy to read, in order to be effective. An incomprehensible or overly complex policy risks being ignored by its audience and left to gather dust on a shelf, failing to influence current operational efforts. It should be a series of simple, direct statements of senior management’s intentions.

The form and organization of security policies can be reflected in an outline format with the following components:

• Author The policy writer

• Sponsor The Executive champion

• Authorizer The Executive signer with ultimate authority

• Effective date When the policy is effective; generally when authorized

• Review date Subject to agreement by all parties; annually at least

• Purpose Why the policy exists; regulatory, advisory, or informative

• Scope Who the policy affects and where the policy is applied

• Policy What the policy is about

• Exceptions Who or what is not covered by the policy

• Enforcement How the policy will be enforced, and consequences for not following it

• Definitions Terms the reader may need to know

• References Links to other related policies and corporate documents

Frameworks

The topics included in a security policy vary from organization to organization according to regulatory and business requirements. We refer to these topics together as a framework.

Organizations may prefer to take a control objective–based approach to creating a security policy framework. For instance, government agencies may take a FISMA-based approach. The Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 imposes a mandatory set of processes that must follow a combination of Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) documents, the NIST Special Publications 800 series, and other legislation pertinent to federal information systems.

Policy Categories

NIST Special Publication 800-53,

Recommended Security Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations, control objectives are organized into 18 major categories (see NIST in

Chapter 3).

Control objective subsets exist for each major control category and equal at least 170 control objectives. NIST SP 800-53 is a good starting point for any organization interested in making sure that all the basic control objectives are met regardless of the industry and whether it is regulated.

Additional Regulations and Frameworks

An organization that must comply with HIPAA (described in

Chapter 3) may map NIST SP 800-53 control objectives to the HIPAA Security Rule. HIPAA categorizes security controls (referred to as

safeguards) into three major categories: Administrative, Physical, and Technical. As an example, CFR Part 164.312 section (c)(1), which requires protection against improper alteration or destruction of data, is a HIPAA required control that maps to NIST 800-53 System and Information Integrity controls.

Some organizations may wish to select a framework based on COBIT (Control Objectives for Information and related Technology). COBIT is an IT governance framework and supporting toolset that allows managers to bridge the gap between control requirements, technical issues, and business risks. Developing policy from a COBIT framework may take considerable collaboration with the Finance and Audit departments. Other organizations may need to combine COBIT with ITIL (IT Infrastructure Library) to ensure that service management objectives are met. ITIL is a cohesive best-practices framework drawn from the public and private sectors internationally. It describes the organization of IT resources to deliver business value, and documents processes, functions, and roles in IT service management.

Still other organizations may wish to follow the OCTAVE (Operationally Critical Threat, Asset, and Vulnerability Evaluation) framework. OCTAVE is a risk-based strategic assessment and planning technique for security from CERT (Carnegie Mellon University). And yet others may need to incorporate the ISO Family (27001 and 27002) from the International Standards Organization. ISO is a framework of standards that provides best practices for information security management.

Depending on which regulated industry an organization finds itself in, it is important to take the time to select an appropriate framework and to map out the regulatory and business requirements in the first phase of development.

Security Awareness

The first line of attack against any organization’s assets is often the trusted internal personnel, the employees that have been granted access to the internal resources. As with most things, the human element is the least predictable and easiest to exploit. Trusted employees are either corrupted or tricked into unintentionally providing valuable information that aids intruders. Because of the high level of trust placed in employees, they are the weakest link in any security chain. Attackers will often “mine” information from employees either by phone, by computer, or in person by gaining information that seems innocuous by itself but provides a more complete picture when pieced together with other fragments of information. Organizations that have a strong network security infrastructure may find their security weakened if the employees are convinced to reduce security levels or reveal sensitive information.

One of the most effective strategies to combat this exposure of information by employees is education. When employees understand that they shouldn’t give out private information, and know the reasons why, and know that they will be held accountable, they are less likely to inadvertently aid an attacker in harvesting information. A good

security awareness program should include communications and periodic reminders to employees about what they should and should not divulge to outside parties. Training and education help mitigate the threats of social engineering and information leakage.

Figure 5-4 depicts some examples of security awareness techniques that can inform different personality types and provide educational opportunities.

Figure 5-4 Ideas to incorporate into a security awareness program

Importance of Security Awareness

An ongoing security awareness program should be implemented for all employees. Security awareness programs vary in scope and content. See the “References” section of this chapter for pointers to good resources for starting and maintaining a security awareness program. In this section, we will explore some of the basics of how to raise security awareness among employees in organizations.

Employees often intentionally or accidentally undermine even the most carefully engineered security infrastructure. That is because they are allowed trusted access to information resources through firewalls, access control devices, buildings, phone systems, and other private resources in order to do their jobs. End users have the system accounts and passwords needed to copy, alter, delete, and print confidential information, change the integrity level of the information, or prevent the information from being available to an authorized user. Propping doors open, giving out their account and password information, and throwing away sensitive papers are common practices in most organizations, and it’s these practices that put the information security program at risk. It’s also these practices that a security awareness program seeks to modify and prevent.

In addition to practicing habits that weaken security, employees are also usually the first to notice security incidents. Employees that are well educated in security principles and procedures can quickly control the damage caused by a security breach. A staff that is aware of security concerns can prevent incidents and mitigate damage when incidents do occur. Employees are a useful component of a comprehensive security strategy.

Objectives of an Awareness Program

The practice of raising the awareness of each individual in the organization is similar to commercial advertising of products. The message must be understood and accepted by each and every person, because every employee is crucial to the success of the security program. One weak link can bring down the entire system. It’s imperative that these objectives be measurable. In a security awareness campaign, the security message is the sales pitch, the product to be sold is the idea of security, and the market is every employee in the organization. Communicating the message is the primary goal, and the information absorbed by the employees is the catalyst for behavioral change. Employees usually know much of what an awareness program conveys. The awareness program reminds them so that secure behaviors are automatic.

A plan for an effective security awareness program should include

• A statement of measurable goals for the awareness program

• Identification and categorization of the audience

• Specification of the information to be included in the program

• Description of how the employees will benefit from the program

Some of this information can be provided by security management (e.g., goals, types of information) and some can be provided by the audience themselves (e.g., demographics, benefits). Surveys and in-person interviews can be utilized to collect some of this information. Identification of specific problems in the organization can provide additional insight. This information is needed to determine how the awareness program will be developed and what form its communication may take.

The objectives of a security awareness program really need to be clarified in advance, because presentation is the key to success. A well-organized, clearly defined presentation to the employees will generate more support and less resistance than a poorly developed, random, ineffective attempt at communication. Compliance with this training is often a requirement. Of paramount importance is the need to avoid losing the audience’s interest or attention or alienating the audience by making them feel like culprits or otherwise inadequate to the task of protecting security. The awareness program should be positive, reassuring, and interesting.

Just as with any educational program, if the audience is given too much information to absorb all at once, they may become overwhelmed and may lose interest in the awareness program. This would result in a failure of the awareness program, since its goal is to motivate all employees to participate. An awareness program should be a long-term, gradual process. An effective awareness program reinforces desired behaviors and gradually changes undesired behaviors.

An awareness program may fail for any of the following reasons:

• It is not changed frequently

• It does not test whether the learner is understanding the material

• It does not test how a user behaves under a given scenario, such as whether the user calls the help desk to report a suspicious event

• It does not incentivize the user to participate

• It does not include performance evaluations and additional tracking

Participation should be consistent and comprehensive, attended and applied by all employees, including contractors and business partners who have access to information systems. New employees should also be folded into the current program. Refresher courses should be given periodically throughout the business year, so attention to the program does not wander, the information stays fresh in the employees’ memories, and changes can be communicated.

Management should allow sufficient time for employees to arrange their work schedules so that they can participate in awareness activities. Typically, the security policy requires that employees sign a document stating that they understand the material presented and will comply with security policies.

Responsibility for conducting awareness program activities needs to be clearly defined, and those who are responsible must demonstrate that they are performing to expectations. The organization’s training department and security staff may collaborate on the program, or an outside organization or consultant may be hired to perform program activities.

Increasing Effectiveness

Security awareness programs are meant to change behaviors, habits, and attitudes. To be successful in this, an awareness program must appeal to positive preferences. For example, a person who believes that it is acceptable to share confidential information with a colleague or give their password out to a new employee must be shown that people are respected and recognized in the organization for protecting confidential data rather than for sharing it.

The overall message of the program should emphasize factors that appeal to the audience. For example, the damage to a person done when their identity or personal information is stolen may result in a lowering of their credit score or increase in their insurance rates. An awareness program can focus on the victims and the harmful results of incautious activities. People need to be made aware that bad security practices hurt people, whether they intend to or not. The negative effects can be spotlighted to provide motivation, but the primary value of scare tactics is to get the user community to start thinking about security (and their decisions and behaviors) in a way that helps them see how they can protect themselves from danger.

Actions that cause inconvenience or require a sacrifice from the audience may not be adopted if the focus is on the difficulty of the actions themselves, rather than the positive effects of the actions. The right message will have a positive spin, encouraging the employees to perform actions that make them heroes, such as the courage and independence it takes to resist appeals from friends and coworkers to share copyrighted software. Withstanding peer pressure to make unethical or risky choices can be shown in a positive light.

Specific topics that are contained in most awareness programs include

• Privacy of personal, customer, and the organization’s information (including payroll, medical, and personnel records)

• The scope of inherent software and hardware vulnerabilities and how the organization manages this risk

• Hostile software or malicious code (for example, viruses, worms, Trojans, back doors, and spyware) and how it can damage the network and compromise the privacy of individuals, customers, and the organization

• The impact of distributed attacks and distributed denial of service attacks and how to defend against them

• The principle of shared risk in networked systems (the risk assumed by one employee is imposed on the entire network)

Walt Disney World’s Security Awareness Program: A Case Study

At the Computer Security Institute’s (CSI’s) NetSec conference in June 2003, Anne Kuhns of Walt Disney World’s IT division demonstrated some of the best features of Disney’s security awareness program at the time. The program included a self-study module incorporating animated visual activities, clever, eye-catching graphics with friendly characters, and a combination of friendly encouragement and stern correction, all in fun.

The module stopped at various checkpoints to ask the employee questions about what they just saw. For example, after describing password policy, it showed four passwords and asked which one complied with the policy. Choosing an incorrect answer earned the employee a stern “No” from the narrator along with an explanation of why the answer was incorrect. A correct answer was required to proceed.

Another section included an interactive activity, to maintain attention. A cartoon desk and computer were shown along with some other items. The items were clickable, and the module asked the employee to identify things on the desk that were violations of security policy—such as a mobile device left unattended, a stack of confidential documents in the trash, and a workstation left logged in while nobody is there. Upon clicking these items, the employee was treated to a positive narration along with a description of why those behaviors are undesirable. The consequences were also mentioned, including the personal risk to the employee, which was an effective attention-getter.

There was also a game-like objective to the training. At the completion of each section, the employee earned a “key.” After collecting four keys, the employee earned a big fanfare and an electronic certificate. Continued employment depended on the successful completion of the training, but the employee also gained a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment from “winning the game.”

Implementing the Awareness Program

Once employees understand how to recognize a security problem, they can begin thinking about how they can perform their job functions in compliance with the security policy, and how they should react to security events and incidents. Typical topics for complying with security policy and incident response include

• How to report potential security events, including who should be notified and what to do during and after an incident, the timeframe for such reporting, and what to do about unauthorized or suspicious activity. Some situations may require use of verbal communication instead of e-mail, such as when another employee (especially a system administrator) is acting suspicious, when a computer system is under attack, or when e-mail may be intercepted by the intruder.

• How to use information technology systems in a secure manner.

• How to create and manage passwords, how to safely conduct file transfers and downloads, and how to handle e-mail attachments.

The awareness program should emphasize that security is a top priority of management. Security practices should be shown to be the responsibility of everyone in the organization, from executive management down to each employee. Employees will take security practices more seriously when they see that it is important to the organization rather than just another initiative like any other, and when executives lead by example. Codes of ethics or behavior principles can be used to let all employees know exactly what to do and what is expected of them.

Employees should also be clear about whom to contact and what to report regarding security incidents. Information should be provided to the employees so that they know whom to contact during an incident. Contact information, such as telephone and pager numbers, e-mail addresses, and web addresses for security staff, the incident response team, and the help desk should be included.

Employees should be made aware that time is critical in security compromise situations. They should be informed that immediate reporting of incidents could contain damage, control the extent of the problem, and prevent further damage.

Enforcement

Enforcement is arguably the most important component of network security. Policies, procedures, and security technologies don’t work if they are ignored or misused. Enforcing the security policy ensures compliance with the principles and practices intended by the architects of the security infrastructure. Security policy enforcement includes a security operations component, which is discussed in more detail in

Chapter 31. However, penalties for not following the policy are typically performed by Human Resources, not Security. Security reports violations, and HR enforces.

Enforcement takes many forms. For general employees, enforcement provides the assurance that daily work activities comply with the security policy. For system administrators and other privileged staff, enforcement guarantees proper maintenance actions and prevents abuse of the higher level of trust given to this category of personnel. For managers, enforcement prevents overriding of the security practices intended by the framers of the security policy, and it reduces the incidence of conflicts of interest produced when managers give their employees orders that violate policy. For everyone, enforcement dissuades people from casually, intentionally, or accidentally breaking the rules.

Negative enforcement usually takes the form of threats to the employee—threats of negative comments on an employee’s review, of a manager’s displeasure, or of termination, for example. For some violations, a progression of corrective actions may be required, eventually culminating in loss of the employee’s job after many repeated violations. For other, more serious breaches of trust, termination may be the first step. Regardless of the severity of the correction, employees should clearly understand what is required of them, and what the process is for punishment when they don’t comply with the rules. In all cases, employees should sign a document indicating their understanding of this process.

Positive enforcement is just as important as negative enforcement, if not more so. This may take the form of rewards to employees who follow the rules. These employees are important—they are the ones who keep the business running smoothly within the parameters of the corporate policy. They should be retained and kept motivated to do the right thing. Rewards can range from verbal congratulations to financial incentives and awards for good behavior.

Policy Enforcement for Vendors

Security enforcement for business partners and other non-corporate entities is the responsibility of the organization’s Board of Directors, which manages relationships with other corporations, makes deals, and signs contracts and statements of intent. These documents should all include security expectations and include signatures of responsible executives. If you want to be able to enforce a particular level of service (defined in the service-level agreement), then you need to define it first. When security policy is violated by partner organizations, the Board of Directors should hold those organizations responsible and take appropriate business measures to correct the problem. This may include financial penalties for underperformance or incentives for overperformance.

Policy Enforcement for Employees

Enforcement of the corporate security policy for employees and temporary workers is usually the direct responsibility of Human Resources. HR implements punitive actions up to and including termination for serious violations of security policy, and it also attempts to correct behavior with warnings and evaluations. Positive reinforcement can also be enacted by HR, in the form of financial bonuses and other incentives.

All employees, without exception, should be held to the same standards of policy enforcement. It is very important not to discriminate or differentiate between employees when enforcing policy. This is especially true of management. Managers, especially senior managers and corporate executives, should be just as accountable as regular employees—perhaps even more so. Senior management should set an example of right behavior for the rest of the organization, and perhaps should be held even to a higher standard than those employees who work for them. When management violates trust or policy, how can employees be expected to adhere to their expectations? By paving the way with high standards of conduct, management helps encourage compliance with the standards of behavior they have set for the employees.

Software-Based Enforcement

Software can sometimes be used to enforce policy compliance, preventing actions that are not allowed by the policy. One example of this is web browsing controls such as web site blockers. These programs maintain a list of prohibited web sites that is consulted each time an end user attempts to visit a web site. If the attempt is made to go to one of the prohibited sites, the attempt is blocked.

Software-based enforcement has the advantage that employees are physically unable to break the rules. Others include Group Policy settings for the operating system. This means that nobody will be able to violate the policy, regardless of how hard they try. Thus, the organization is assured 100 percent policy compliance. Software enforcement is the easiest and most reliable method of ensuring compliance with security policy.

There are some disadvantages to software enforcement as well. One disadvantage is that employees who are grossly negligent or willful policy violators (bad seeds) will not be discovered. Some organizations want to weed out these people from their staff, so their employees will consist of mostly honest, hard-working people. With software-based enforcement, it is harder to discover the time wasters, who may find other, less apparent ways of being inefficient. Another disadvantage of automated enforcement is that it may cause disgruntlement and unhappiness among employees who feel that the organization is constraining them, making them conform to a code of behavior with which they do not agree. These employees may feel that “big brother is watching them” and may feel uncomfortable with confining controls. Depending on the corporate culture, this may be a more or less serious problem.

Automated enforcement of policy by software can also be circumvented by trusted administrative personnel who have special access to disable, bypass, or modify the security configuration to give themselves special permissions not granted to regular employees. This breach of trust may be difficult to prevent or detect. This is a more general problem that applies to administrative personnel who are responsible for security devices and controls. The best solution is to implement separation of duties, so that violation of trust requires more than one person—two or more trusted employees would have to collude to get around the system. Finally, security policies must be in balance with functional requirements.

Regardless of the corporate culture, and how software-based enforcement is used in the organization to control behavior and encourage compliance with the corporate security policy and acceptable use policy, those policies should be well documented and clearly communicated to employees, with signatures by the employees indicating that they understand and agree to the terms. Additionally, software-based enforcement, when used, should be only one step in the chain of enforcement techniques that includes other levels, up to and including termination. Organizations should not rely solely on software for this purpose; they should have clearly defined levels of deterrence that employees understand. In most organizations, employment is an at-will contract between the employer and the employee, and employees should understand that they can lose their job if they try to behave in ways that violate the ethics or principles of the employer. Don’t use software as an excuse or a means of avoiding the difficulties and hardships of enforcement; instead, use it as a tool to accomplish the organization’s enforcement goals.

Every industry has different audit requirements and data retention policies based on which standards they adhere to. Some industries are required to have external, independent auditors, while other industries may be fine with internal, in-house audits. Do your due diligence and practice due care by finding out which laws and regulations you are required to be in compliance with.

Example Security Policy Topics

This section includes sample security policy topics to provide insight into the subjects that might be included in a general security policy for a typical organization. These examples are meant to inspire you to consider which topics might apply to your particular situation and to provide a starting point for thinking about other subjects that might be relevant. Many policy writers are focused on particular subjects, like passwords or network segmentation, and this can make it difficult to think about other topics that should be covered. Referring to this list may help policy writers broaden their focus.

This particular set of policy statements is oriented toward a typical small to midsize organization attempting to protect its data resources. Use this as a starting point for elements of your security policy, or compare it with your existing security policy to see whether yours needs additional scope.

NOTE The security policy can be divided into sections relating to any reasonable groupings of subjects, such as computers, networks, data, and so on.

The following policy examples are organized in conceptual categories, according to their general focus. These categories include acceptable use, computer, network, data privacy, data integrity, personnel management, security management, and physical security policies. These can serve either as topic ideas or as starting points for more comprehensive policy statements. A full policy would contain the information in the following examples along with a statement of purpose (indicating why each policy is required), a scope definition (indicating to whom each policy applies), a statement of monitoring and auditing (indicating how compliance will be measured and assessed), and a statement about enforcement (indicating what can happen if the policy is violated).

NOTE The following policy examples are intended to serve as a starting point for your organization. Your requirements will vary. Ideally, the following policy examples will provide you with ideas about topics for your own policy.

Acceptable Use Policies

Employees may find it helpful to understand exactly how the organization expects them to use computing resources. Every organization has expectations for employee use of computers, but these must be communicated in advance to be effectively enforced.

The following is a sample of an acceptable use policy. Notice that the policy is composed of clear, easy-to-read instructions that everyone can understand.

1. PURPOSE

1.1. The organization’s information resources exist in order to support business purposes. Inadvertent or intentional misuse can damage the organization’s business, its customers, vendors, partners, shareholders, and employees. This policy is intended to minimize that damage.

2. SCOPE

2.1. This policy is applicable to all information resources including software, web browsers, email, computer systems, workstations, PCs, servers, mobile devices, entities connected on the network, software, data, telephones, voice mail, fax machines, and any information resources that could be considered valuable to the business, in all locations.

3. RESPONSIBILITIES

3.1. All employees, contractors, consultants, service providers, and temporary workers are responsible for following these practices.

4. ACCEPTABLE USE OF INFORMATION RESOURCES

What to do:

• Protect the organization’s intellectual property and keep it confidential

• Report any unauthorized or inappropriate use, or any security concerns

• Follow the guidance in the Information Classification, Labeling, and Handling policy

What not to do:

• Do not forward, provide access, store, distribute, and/or process confidential information to unauthorized people or places, or post confidential information on Internet bulletin boards, chat rooms, or other electronic forums

• Do not access information resources, records, files, information, or any other data when there is no proper, authorized, job-related need

• Do not provide false or misleading information to obtain access to information resources

• Do not use any account and/or password that has not been assigned to you

• Do not perform any conduct which may harm the organization’s reputation

• Do not view offensive websites, send or forward offensive email

• Do not place personal files on the organization’s computing servers

• Do not connect any equipment not owned and managed by the organization to the organization’s network

• Do not install personally owned software or non-licensed software on the organization’s computers

Personal Use of Information Systems Personal use of the organization’s computer systems is allowed on a limited basis to employees provided that it does not interfere with the organization’s business, expose the organization to liability or damage, compromise the organization’s intellectual property, or violate any laws.

Employees should be advised that the organization may at any time be required by law to print or copy files, e-mail, hard copy, or backups and provide this information to government or law enforcement agencies.

Internet Usage Monitoring All connections to the Internet must be monitored for the following activities:

• Attempts to access restricted web sites

• Transfers of very large files

• Excessive web browsing

• Unauthorized hosting of web servers by employees

• Transfers of the organization’s data to or from the Internet

Personal Web Sites Employees may not run personal web sites on the organization’s equipment.

Ethical Use of the Internet Personal Internet use must conform to the corporate standard of ethics.

Non-Corporate Usage Agreement Outside organizations must sign a usage agreement before connecting to the corporate data resources.

Employee Usage Agreement All employees must sign a usage agreement.

Personal Use of Telephones Corporate phone systems may be used for limited, local, personal calls, as long as this usage does not interfere with the performance of the corporate business.

Personal Use of Long-Distance Corporate phone systems may be used for personal domestic long-distance calls, providing that the expense for these calls does not exceed reasonable limits.

Computer Policies

This group of policies applies to computers and information systems. Authentication policies often form the largest collection of policy statements in a computer environment because authentication systems and variations are so complex and because they tend to have the greatest impact on the average computer user. Password policies are often the largest subset of authentication policies.

Account/Password Authentication A unique account and password combination must authenticate all users of information systems. The account name must be used only by a single individual, and the password must be a secret known only to that individual.

New Account Requests The manager responsible for a new end user must request access to corporate information systems via a new account. End users may not request their own accounts. The new account request must be recorded and logged for the record. When the account is no longer needed, the account must be disabled.

Account Changes The manager responsible for the end user must request changes in access privileges for corporate information systems for a system account. End users may not request access-privilege changes to their own accounts. The request must be recorded and logged for the record.

Two-Factor Authentication All administrators of critical information servers must be authenticated via a token card and PIN code. The individual must be uniquely identified based on possession of the token card and knowledge of a secret PIN code known only to the individual user.

Desktop Command Access Access to operating system components and system administration commands on end-user workstations or desktop systems is restricted to system support staff only. End users will be granted access only to commands required to perform their job functions.

Generic User Accounts Generic system accounts for use by people are prohibited. Each system account must be traceable to a single specific individual who is responsible and accountable for its use. Passwords may not be shared with any other person.

Inactive Screen Lock Computer systems that are left unattended must be configured to lock the screen with a password-protected screensaver after a period of inactivity. This screen locking must be configured on each computer system to ensure that unattended computer systems do not become a potential means to gain unauthorized access to the network.

Login Message All computer systems that connect to the network must display a message before connecting the user to the network. The intent of the login message is to remind users that information stored on the organization’s information systems belongs to the organization and should not be considered private or personal. The message must also direct users to the corporate information system usage policy for more detailed information. The message must state that by logging on, the user agrees to abide by the terms of the usage policy. Continuing to use the system indicates the user’s agreement to adhere to the policy.

Failed Login Account Disabling After ten successive failed login attempts, a system account must be automatically disabled to reduce the risk of unauthorized access. Any legitimate user whose account has been disabled in this manner may have it reactivated by providing both proof of identity and management approval for reactivation.

Password Construction Account names must not be used in passwords in any form. Dictionary words and proper names must not be used in passwords in any form. Numbers that are common or unique to the user must not be used in passwords in any form. Passwords shorter than eight characters are not allowed.

Password Expiration Passwords may only be used for a maximum of 3 months. Upon the expiration of this period, the system must require the user to change their password. The system authentication software must enforce this policy.

Password Privacy Passwords that are written down must be concealed in a way that hides the fact that the written text is a password. When written, the passwords should appear as part of a meaningless or unimportant phrase or message, or be encoded in a phrase or message that means something to the password owner but to nobody else. Passwords sent via e-mail must use the same concealment and encoding as passwords that are written down, and in addition must be encrypted using strong encryption.

Password Reset In the event that a new password must be selected to replace an old one outside of the normally scheduled password change period, such as when a user has forgotten their password or when an account has been disabled and is being reactivated, the new password may only be created by the end user, to protect the privacy of the password.

Password Reuse When the user changes a password, the last six previously used passwords may not be reused. The system authentication software must enforce this policy.

Employee Account Lifetime Permanent employee system accounts will remain valid for a period of 12 months, unless otherwise requested by the employee’s manager. The maximum limit on the requested lifetime of the account is 24 months. After the lifetime of the account has expired, it can be reactivated for the same length of time upon presentation of both proof of identity and management approval for reactivation.

Contractor Account Lifetime Contractor system accounts will remain valid for a period of 12 months, unless otherwise requested by the contractor’s manager. The maximum limit on the requested lifetime of the account is 24 months. After the lifetime of the account has expired, it can be reactivated for the same length of time upon presentation of both proof of identity and management approval for reactivation.

Business Partner Account Lifetime Business partner system accounts will remain valid for a period of 3 months, unless otherwise requested by the manager responsible for the business relationship with the business partner. The maximum limit on the requested lifetime of the account is 12 months. After the lifetime of the account has expired, it can be reactivated for the same length of time upon presentation of both proof of identity and management approval for reactivation.

Same Passwords On separate computer systems, the same password may be used. Any password that is used on more than one system must adhere to the policy on password construction.

Generic Application Accounts Generic system accounts for use by applications, databases, or operating systems are allowed when there is a business requirement for software to authenticate with other software. Extra precautions must be taken to protect the password for any generic account. Whenever any person no longer needs to know the password, it must be changed immediately. If the software is no longer in use, the account must be disabled.

Inactive Accounts System accounts that have not been used for a period of 90 days will be automatically disabled to reduce the risk of unused accounts being exploited by unauthorized parties. Any legitimate user whose account has been disabled in this manner may have it reactivated by providing both proof of identity and management approval for reactivation.

Unattended Session Logoff Login sessions that are left unattended must be automatically logged off after a period of inactivity. This automatic logoff must be configured on each server system to ensure that idle sessions do not become a potential means to gain unauthorized access to the network.

User-Constructed Passwords Only the individual owner of each account may create passwords, to help ensure the privacy of each password. No support staff member, colleague, or computer program may generate passwords.

User Separation Each individual user must be blocked by the system architecture from accessing other users’ data. This separation must be enforced by all systems that store or access electronic information. Each user must have a well-defined set of information that can be located in a private area of the data storage system.

Multiple Simultaneous Logins More than one login session at a time on any server is prohibited, with the exception of support staff. User accounts must be set up to automatically disallow multiple login sessions by default for all users. When exceptions are made for support staff, the accounts must be manually modified to allow multiple sessions.

Network Policies

This next group of policies applies to the network infrastructure to which computer systems are attached and over which data travels. Policies relating to network traffic between computers can be the most variable of all, because an organization’s network is the most unique component of its computing infrastructure, and because organizations use their networks in different ways. These example policies may or may not apply to your particular network, but they may provide inspiration for policy topics you can consider.

Extranet Connection Access Control All extranet connections (connections to and from other organizations’ networks outside of the organization, either originating from the external organization’s remote network into the internal network, or originating from the internal network going out to the external organization’s remote network) must limit external access to only those services authorized for the remote organization. This access control must be enforced by IP address and TCP/UDP port filtering on the network equipment used to establish the connection.

System Communication Ports Systems communicating with other systems on the local network must be restricted only to authorized communication ports. Communication ports for services not in use by operational software must be blocked by firewalls or router filters.

Inbound Internet Communication Ports Systems communicating from the Internet to internal systems must be restricted to use only authorized communication ports. Firewall filters must block communication ports for services not in use by operational system software. The default must be to block all ports, and to make exceptions to allow specific ports required by system software.

Outbound Internet Communication Ports Systems communicating with the Internet must be restricted to use only authorized communication ports. Firewall filters must block communication ports for services not in use by operational system software. The default must be to block all ports, and to make exceptions to allow specific ports required by system software.

Unauthorized Internet Access Blocking All users must be automatically blocked from accessing Internet sites identified as inappropriate for the organization’s use. This access restriction must be enforced by automated software that is updated frequently.

Extranet Connection Network Segmentation All extranet connections must be limited to separate network segments not directly connected to the corporate network.

Virtual Private Network All remote access to the corporate network is to be provided by virtual private network (VPN). Dial-up access into the corporate network is not allowed.

Virtual Private Network Authentication All virtual private network connections into the corporate network require token-based or biometric authentication.

Home System Connections Employee and contractor home systems may connect to the corporate network via a virtual private network only if they have been installed with a corporate-approved, standard operating system configuration with appropriate security patches as well as corporate-approved personal firewall software or a network firewall device.

Data Privacy Policies

The topic of data privacy is often controversial and can have significant legal ramifications. Consult a legal adviser before implementing this type of policy. The legal definition of data ownership can be complex depending on how an organization’s computer systems are used and what expectations have been communicated to employees.

Copyright Notice All information owned by the organization and considered intellectual property, whether written, printed, or stored as data, must be labeled with a copyright notice.

E-Mail Monitoring All e-mail must be monitored for the following activity:

• Non-business use

• Inflammatory, unethical, or illegal content

• Disclosure of the organization’s confidential information

• Large file attachments or message sizes

Information Classification Information must be classified according to its intended audience and be handled accordingly. Every piece of information must be classified into one of the following categories:

• Personal Information not owned by the organization, belonging to private individuals

• Public Information intended for distribution to and viewing by the general public

• Confidential Information for use by employees, contractors, and business partners only

• Proprietary Intellectual property of the organization to be handled only by authorized parties

• Secret Information for use only by designated individuals with a need to know

Intellectual Property All information owned by the organization is considered intellectual property. As such, it must not be disclosed to unauthorized individuals. The organization’s intellectual property must be protected and kept confidential. Forwarding intellectual property to unauthorized users, providing access to intellectual property to unauthorized users, distributing intellectual property to unauthorized users, storing intellectual property in unauthorized locations, and processing unauthorized intellectual property is prohibited. Any unauthorized or inappropriate use must be reported immediately.

Clear Text Passwords Passwords may not be sent in clear text over the Internet or any public or private network either by individuals or by software, nor may they be spoken over public voice networks without the use of encryption.

Clear Text E-mail E-mail may be sent in clear text over the Internet, as long as it does not contain secret, proprietary, or confidential corporate information. E-mail containing sensitive or non-public information must be encrypted.

Customer Information Sharing Corporate customer information may not be shared with outside organizations or individuals.

Employee Information Sharing No employee information may be disclosed to outside agencies or individuals, with the following exceptions:

• Date of hire

• Length of tenure

Employee Communication Monitoring The organization reserves the right to monitor employee communications.

Examination of Data on the Organization’s Systems The organization reserves the right to examine all data on its computer systems.

Search of Personal Property The organization reserves the right to examine the personal property of its employees and visitors brought onto the organization’s premises.

Confidentiality of Non-Corporate Information All customer and business partner information is to be treated as confidential.

Encryption of Data Backups All data backups must be encrypted.

Encryption of Extranet Connection All extranet connections must use encryption to protect the privacy of the information traversing the network.

Shredding of Private Documents Sensitive, confidential, proprietary, and secret paper documents must be shredded when discarded.

Destruction of Computer Data Sensitive, confidential, proprietary, and secret computer data must be strongly overwritten when deleted.

Cell Phone Privacy Private business information may not be discussed via cell phone, due to the risk and ease of eavesdropping.

Confidential Information Monitoring All electronic data entering or leaving the internal network must be monitored for the following:

• Confidential information sent via e-mail or file transfer

• Confidential information posted to web sites or chat rooms

• Disclosure of source code or other intellectual property

Unauthorized Data-Access Blocking Each individual user must be blocked by the system architecture from accessing unauthorized corporate data. This separation must be enforced by all systems that store or access electronic information. Corporate information that has been classified as being accessible to a subset of users, but not to all users, must be stored and accessed in such a way that accidental or intentional access by unauthorized parties is not possible.

Data Access Access to corporate information, hard copy, and electronic data is restricted to individuals with a need to know for a legitimate business reason. Each individual is granted access only to those corporate information resources required for them to perform their job functions.

Server Access Access to operating system components and system administration commands on corporate server systems is restricted to system support staff only. End users will be granted access only to commands required for them to perform their job functions.

Highly Protected Networks In networks that have unique security requirements that are more stringent than those for the rest of the corporate network and contain information that is not intended for general consumption by employees and is meant only for a small number of authorized individuals in the organization (such as salary and stock information or credit card information), the data on these networks must be secured from the rest of the network. Encryption must be used to ensure the privacy of communications between the protected network and other networks, and access control must be employed to block unauthorized or accidental attempts to access the protected network from the corporate network.

Data Integrity Policies

Data integrity policies focus on keeping valuable information intact. It is important to start with definitions of how data integrity may be compromised, such as by viruses, lack of change control, and backup failure.

Workstation Antivirus Software All workstations and servers require antivirus software.

Virus-Signature Updating Virus signatures must be updated immediately when they are made available from the vendor.

Central Virus-Signature Management All virus signatures must be updated (pushed) centrally.

E-Mail Virus Blocking All known e-mail virus payloads and executable attachments must be removed automatically at the mail server.

E-Mail Subject Blocking Known e-mail subjects related to viruses must be screened at the mail server, and messages with these subjects must be blocked at the mail server.

Virus Communications Virus warnings, news, and instructions must be sent periodically to all users to raise end-user awareness of current virus information and falsehoods.

Virus Detection, Monitoring, and Blocking All critical servers and end-user systems must be periodically scanned for viruses. The virus scan must identify the following:

• E-mail-based viruses arriving on servers and end-user systems

• Web-based viruses arriving on servers and end-user systems

• E-mail attachments containing suspected virus payloads

Notification must be provided to system administration staff and the intended recipient when a virus is detected.

All critical servers and end-user systems must be constantly monitored at all times for virus activity. This monitoring must consist of at least the following categories:

• E-mail-based viruses passing through mail servers

• Web-based viruses passing through web servers

• Viruses successfully installed or executed on individual systems

Notification must be provided to system administration staff and the intended recipient when a virus is detected.

Viruses passing through web proxy servers and e-mail gateways must be blocked in the following manner:

• E-mail-based viruses passing through mail servers must have the attachment removed

• Web-based viruses passing through web servers must have the attachment removed

• Messages with subject lines known to be associated with viruses must not be passed through mail servers, and must instead be discarded

Notification must be provided to system administration staff and the intended recipient when a message or web page containing a suspected virus is blocked.

Back-out Plan A back-out plan is required for all production changes.

Software Testing All software must be tested in a suitable test environment before installation on production systems.

Division of Environments The division of environments into Development, Test, Staging, and Production is required for critical systems.

Version Zero Software Version zero software (1.0, 2.0, and so on) must be avoided whenever possible to avoid undiscovered bugs.

Backup Testing Backups must be periodically tested to ensure their viability.

Online Backups For critical servers with unique data, online (disk) backups are required, along with offline (tape) backups.

Onsite Backup Storage Backups are to be stored onsite for one month before being sent to an offsite facility.

Fireproof Backup Storage Onsite storage of backups must be fireproof.

Offsite Backup Storage Backups older than one month must be sent offsite for permanent storage.

Quarter-End and Year-End Backups Quarter-end and year-end backups must be done separately from the normal schedule, for accounting purposes.

Change Control Board A corporate Change Control Board must be established for the purpose of approving all production changes before they take place.

Minor Changes Support staff may make minor changes without review if there is no risk of service outage.

Major Changes The Change Control Board must approve major changes to production systems in advance, because they may carry a risk of service outage.

Vendor-Supplied Application Patches Vendor-supplied patches for applications must be tested and installed immediately when they are made available.

Vendor-Supplied Operating System Patches Vendor-supplied patches for operating systems must be tested and installed immediately when they are made available.

Vendor-Supplied Database Patches Vendor-supplied patches for databases must be tested and installed immediately when they are made available.

Disaster Recovery A comprehensive disaster-recovery plan must be used to ensure continuity of the corporate business in the event of an outage.

System Redundancy All critical systems must be redundant and have automatic failover capability.

Network Redundancy All critical networks must be redundant and have automatic failover capability.

Personnel Management Policies

Personnel management policies describe how people are expected to behave. For each intended audience (management, system administrators, general employees, and so on), the policy addresses specific behaviors that are expected by management with respect to computer technologies and how they are used.

NOTE Some policies relate to computers and others relate to people. It can be helpful to separate the two types into different sections, because they may have different audiences. This section includes policies related to people.

Many of these policies apply to system administrators, who have elevated levels of privilege that provide fuller access to data and systems than regular employees have. This presents unique challenges and requirements for maintaining the privacy, integrity, and availability of systems to which administrators may have full, unrestricted access.

CAUTION Many organizations overlook the special requirements of system administrators in their security policies. Doing so can leave a large vulnerability unchecked, because system administrators have extensive privileges that can produce catastrophic consequences if they are misused or if accidents happen.

Application Monitoring All servers containing applications designated for monitoring must be constantly monitored during the hours the application operates. At least the following activities must be monitored:

• Application up/down status

• Resource usage

• Nonstandard behavior of application

• Addition or change of the version, or application of software patches

• Any other relevant application information

Desktop System Administration No user of a workstation or desktop system may be the system administrator for their own system. The root or Administrator password may not be made available to the user.

Intrusion-Detection Monitoring All critical servers must be constantly monitored at all times for intrusion detection. This monitoring must cover at least the following categories:

• Port scans and attempts to discover active services

• Nonstandard application connections

• Nonstandard application behavior

• Multiple applications

• Sequential activation of multiple applications

• Multiple failed system login attempts

• Any other relevant intrusion-detection information

Firewall Monitoring All firewalls must be constantly monitored, 24×7×365, by trained security analysts. This monitoring must include at least the following activities:

• Penetration detection (on the firewall)

• Attack detection (through the firewall)

• Denial of service detection

• Virus detection

• Attack prediction

• Intrusion response

Network Security Monitoring All internal and external networks must be constantly monitored, 24×7×365, by trained security analysts. This monitoring must detect at least the following activities:

• Unauthorized access attempts on firewalls, systems, and network devices

• Port scanning

• System intrusion originating from a protected system behind a firewall

• System intrusion originating from outside the firewall

• Network intrusion

• Unauthorized modem dial-in usage

• Unauthorized modem dial-out usage

• Denial of services

• Correlation between events on the internal network and the Internet

• Any other relevant security events

System Administrator Authorization System administration staff may examine user files, data, and e-mail when required to troubleshoot or solve problems. No private data may be disclosed to any other parties, and if any private passwords are thus identified, this must be disclosed to the account owner so they can be changed immediately.

System Administrator Account Monitoring All system administration accounts on critical servers must be constantly monitored at all times. At least the following categories of activities must be monitored:

• System administrator account login and logout

• Duration of login session

• Commands executed during login session

• Multiple simultaneous login sessions

• Multiple sequential login sessions

• Any other relevant account information

System Administrator Authentication Two-factor token or biometric authentication is required for all system administrator account access to critical servers.

System Administrator Account Login System administration staff must use accounts that are traceable to a single individual. Access to privileged system commands must be provided as follows:

• On Unix systems Initial login must be from a standard user account, and root access must be gained via the su command.

• On Windows systems System administration must be done from a standard user account that has been set up with Administrator privileges.

Direct login to the root or Administrator account is prohibited.

System Administrator Disk-Space Usage Monitoring System administration staff may examine user files, data, and e-mail when required to identify disk-space usage for the purposes of disk usage control and storage capacity enhancement and planning.

System Administrator Appropriate Use Monitoring System administration staff may examine user files, data, and e-mail when required to investigate appropriate use.

Remote Virus-Signature Management All virus software must be set up to support secure remote virus-signature updates, either automatically or manually, to expedite the process of signature file updating and to ensure that the latest signature files are installed on all systems.

Remote Server Security Management All critical servers must be set up to support secure remote management from a location different from where the server resides. Log files and other monitored data must be sent to a secure remote system that has been hardened against attack, to reduce the probability of log file tampering.

Remote Network Security Monitoring All network devices must be set up to support security management from a location different from where the network equipment resides. Log files and other monitored data must be sent to a secure remote system that has been hardened against attack, to reduce the probability of log file tampering.

Remote Firewall Management All firewalls must be set up to support secure remote management from a location different from where the firewall resides. Log files and other monitored data must be sent to a secure remote system that has been hardened against attack, to reduce the probability of log file tampering.

Security Management Policies

Managers have responsibilities for security just as employees do. Detailing expectations for managers is crucial to ensure compliance with senior management’s expectations.

Employee Nondisclosure Agreements All employees must sign a nondisclosure agreement that specifies the types of information they are prohibited from revealing outside the organization. The agreement must be signed before the employee is allowed to handle any private information belonging to the organization. Employees must be made aware of the consequences of violating the agreement, and signing the agreement must be a condition of employment, such that the organization may not employ anyone who fails to sign the agreement.

Nondisclosure Agreements All business partners wishing to do business with the organization must sign a nondisclosure agreement that specifies the types of information they are prohibited from revealing outside the organization. The agreement must be signed before the business partner is allowed to view, copy, or handle any private information belonging to the organization.

System Activity Monitoring All internal information system servers must be constantly monitored, 24×7×365, by trained security analysts. At least the following activities must be monitored:

• Unauthorized access attempts

• Root or Administrator account usage

• Nonstandard behavior of services

• Addition of modems and peripherals to systems

• Any other relevant security events

Software Installation Monitoring All software installed on all servers and end-user systems must be inventoried periodically. The inventory must contain the following information:

• The name of each software package installed on each system

• The software version

• The licensing status

System Vulnerability Scanning All servers and end-user systems must be periodically scanned for known vulnerabilities. The vulnerability scan must identify the following:

• Services and applications running on the system that could be exploited to compromise security

• File permissions that could grant unauthorized access to files

• Weak passwords that could be easily guessed by people or software

Security Document Lifecycle All security documents, including the corporate security policy, must be regularly updated and changed as necessary to keep up with changes in the infrastructure and in the industry.

Security Audits Periodic security audits must be performed to compare existing practices against the security policy.

Penetration Testing Penetration testing must be performed on a regular basis to test the effectiveness of information system security.

Security Drills Regular “fire drills” (simulated security breaches, without advance warning) must take place to test the effectiveness of security measures.

Extranet Connection Approval All extranet connections require management approval before implementation.

Non-Employee Access to Corporate Information Non-employees (such as spouses) are not allowed to access the organization’s information resources.

New Employee Access Approval Manager approval is required for new employee access requests.

Employee Access Change Approval Manager approval is required for employee access change requests.

Contractor Access Approval Manager approval is required for contractor access requests.

Employee Responsibilities The following categories of responsibilities are defined for corporate employees. These categories consist of groupings of responsibilities that require differing levels of access to computer systems and networks. They are used to limit access to computers and networks based on job requirements, to implement the principles of least privilege and separation of duties.

• General User

• Operator

• System Administrator