Jesus’ Arrest (18:1–11)

The Gospels narrate two trials of Jesus, one Jewish and one Roman.524 The former started with an informal hearing before Annas (18:12–14, 19–24), while Sanhedrin members were probably summoned in order to stage a more formal trial. A meeting of the highest Jewish body (Matt. 26:57–68; Mark 14:53–65) then led to formal charges and the sending of a delegation to Pilate (Matt. 27:1–2; Luke 22:66–71). The Roman trial consisted of an initial interrogation by Pilate (Matt. 27:11–14; John 18:28–38a), followed by an appearance before Herod (Luke 23:6–12) and a final summons before Pilate (Matt. 27:15–31; John 18:38b–19:16).

Though Jewish law contained numerous stipulations regarding legal proceedings against those charged with serious offenses, many such stipulations could be breached if the matter was judged to be urgent (including the possibility of mob violence). Another factor in Jesus’ case was that executions could proceed on feast days but not on a Sabbath. Thus if Jesus’ arrest took place on Thursday evening, little time remained if he was to be tried and put to death before the onset of the Sabbath at sundown of the following day. Moreover, Roman officials such as Pilate worked only from dawn until late morning, so that the Jews’ case against Jesus had to be prepared overnight.525

The Kidron Valley (18:1). The Kidron Valley is frequently mentioned in the LXX and Jewish intertestamental literature.526 Literally, the expression is “the brook [cheimarros] of Kidron,” where “brook” refers to an intermittent stream that is dry most of the year but swells up during rainfalls, particularly in the winter (Josephus, Ant. 8.1.5 §17). The Kidron Valley, called “Wadi en-Nar,” continues variously south or southeast until it reaches the Dead Sea (cf. Ezek. 47:1–12; Zech. 14:8).

An olive grove (18:1). To the east of the Kidron rises the Mount of Olives. The olive grove (kēpos, lit. “garden”) on its slopes is called “Gethsemane” (meaning “oil press”) in the Synoptics.527 This garden may have been made available to Jesus and his followers by a wealthy person who supported Jesus’ ministry. The phrase “there was” rather than “there is” may indicate that the garden had been destroyed by the time of the writing of John’s Gospel.

Went into it (18:1). John’s terminology (“went into it,” later “went out”) suggests a walled garden. According to Jewish custom (with reference to Deut. 16:7), Passover night was to be spent in Jerusalem, but in light of the large number of pilgrims, city limits were extended as far as Bethphage on the Mount of Olives (though Bethany lay beyond the legal boundary).528

A detachment of soldiers (18:3). A speira was a detachment consisting of a cohort of Roman soldiers.529 A full cohort was led by a chiliarchos (lit., “leader of a thousand,” rendered “tribune” or “commander”) and consisted of one thousand men, though in practice it often numbered only six hundred.530 The Romans could use surprisingly large numbers of soldiers even for a single person (like the 470 men protecting Paul in Acts 23:23), especially if they feared a riot. Roman troops were stationed in Caesarea, but during feast days gathered northwest of the temple by the fortress of Antonia. This enabled the Romans to keep a close eye on the large crowds during Jewish festivals and to quell any mob violence at the very outset.

Some officials from the chief priests and Pharisees (18:3). These “officials” (hypēretai) represented the temple police, the primary arresting officers. This unit was commanded by the captain of the temple guard (cf. Acts 4:1), who was charged with watching the temple at night (m. Mid. 1:1–2). Their arms and methods are recalled in a “street ballad”:

Woe is me, for the house of Boethus: woe is me, for their clubs!

Woe is me, for the house of Annas: woe is me, for their whisperings!

Woe is me, for the house of Kdathros: woe is me, for their pen!

Woe is me, for the house of Ishmael (ben Phabi): woe is me, for their fist!

For they are the High Priests, and their sons the treasurers: their sons-in-law are Temple-officers, and their servants beat the people with their staves.531

The chief priests (made up predominantly of Sadducees) and the Pharisees are regularly linked in this Gospel (cf. Josephus, Life 5 §21).

Chief priests (18:3). The rubric of “chief [or high] priests” included the incumbent high priest, former high priests still living (such as Annas), and members of aristocratic families from whom high priests were chosen.532

They were carrying torches, lanterns and weapons (18:3). Torches (lampas) consisted of resinous strips of wood fastened together.533 Lanterns (phanoi) were “roughly cylindrical terracotta vessels with an opening on one side large enough for a household lamp to be inserted, its wick facing outward; a ceramic ring—or strap—handle on the top permitted easy carrying. Occasionally lanterns may have had built-in lamps.”534 Roman soldiers carried both kinds of lighting devices,535 and the temple guard went on their rounds with “lighted torches” (m. Mid. 1:2). While this was the time close to the full paschal moon, lanterns might still be needed to track down a suspect who (it probably was suspected) was hiding from the authorities in the dark corners of this olive grove. “They were carrying” does not mean that all are carrying torches; it would have been sufficient for only some to do so. Regarding the carrying of weapons, it may be noted that sometimes the temple guards were unarmed,536 but in the present instance both they and the Roman soldiers take no chances.

I am he (18:5). Literally, “I am.” In light of people’s response, the phrase probably has connotations of deity.

And fell to the ground (18:6). Falling to the ground is regularly a reaction to divine revelation.537 Legend has it that Pharaoh fell to the ground speechless when Moses uttered the secret name of God.538 Falling to the ground also speaks of the powerlessness of the enemies when confronted with the power of God. The phrase is reminiscent of certain passages in the Psalms.539 Jewish literature recounts the story of the attempted arrest of Simeon: “On hearing his voice they fell on their faces and their teeth were broken” (Gen. Rab. 91:6). The reaction also highlights Jesus’ messianic authority in keeping with passages such as Isaiah 11:4: “He will strike the earth with the rod of his mouth; with the breath of his lips he will slay the wicked” (cf. 2 Esd. 13:3–4).

Malchus (18:10). The name Malchus is not uncommon in the first century A.D. It occurs several times in Josephus, almost entirely of Natabean Arabs540 as well as in the Palmyrene and Nabatean inscriptions.541 The name probably derives from the common Semitic root mlk (melek means “king”).

MODEL OF A ROMAN ERA SWORD

Sword (18:10). According to Luke 22:38, Jesus’ disciples possessed a total of two swords. The term “sword” (machaira) may refer to a long knife or a short sword, with rhomphaia being the large sword. The fact that Peter’s action is unforeseen suggests the short sword, which could be concealed under one’s garments. It may have been illegal to carry such a weapon at Passover: “A man may not go out with a sword” (m. Šabb. 6:4; so the Sages with reference to Isa. 2:4, but not R. Eliezer [A.D. 90–130]: “They are his adornments”).

Right ear (18:10). Both Mark (14:47) and John use the term ōtarion, a double diminutive, equivalent to our “earlobe.” It is possible that Peter deliberately chooses the right ear (which was considered to be the more valuable)542 as a mark of defiance. While generally an injury to a slave would not have aroused much interest, Jesus shows concern even for this (by human standards) insignificant (Arab?) slave.

The cup (18:11). “Cup” serves here as a metaphor for death. In the Old Testament, the expression refers primarily to God’s “cup of wrath,” which evildoers will have to drink.543 Similar terminology is found in later Jewish writings and the New Testament.544 This imagery may have been transferred to the righteous, guiltless one taking on himself God’s judgment by way of substitutionary suffering.545

Jesus Taken to Annas (18:12–14)

The detachment of soldiers … its commander … the Jewish officials (18:12). See comments on 18:3.

They bound him (18:12). “To be bound” is a customary expression in conjunction with arrest or imprisonment (e.g., Acts 9:2, 14, 21; already in Plato, Leg. 9.864E).

Annas (18:13). See “Annas the High Priest.”

Caiaphas, the high priest that year. Caiaphas was the one who had advised the Jews that it would be good if one man died for the people (18:13–14). See comments on 11:49–52. Under Roman occupation, the high priests were the dominant political leaders of the Jewish nation.546

Peter’s First Denial (18:15–18)

Another disciple … was known to the high priest (18:15). The “other disciple” is probably none other than “the disciple Jesus loved” (cf. 20:2).547 While John was a fisherman, this does not mean that he stemmed from an inferior social background. John’s father Zebedee is presented in Mark 1:20 as a man with hired servants, and either John and his brother James or their mother had prestigious ambitions (Matt. 20:20–28 par.). Moreover, it is not impossible that John himself came from a priestly family.548 “Known” (gnōstos; used in John 18:15, 16) may suggest more than mere acquaintance. The term is used for a “close friend” in the LXX.549

The high priest’s courtyard (18:15). The official high priest was Caiaphas, though Annas may have been referred to under this designation as well (see comments on 18:13). Presumably, he lived in the Hasmonean palace on the west hill of the city, which overlooked the Tyropoeon Valley and faced the temple. It is possible that Caiaphas and Annas lived in the same palace, occupying different wings bound together by a common courtyard.

The high priest (18:15–16). The sequence of references to “the high priest” in this chapter (esp. 18:13–14, 19, 24) shows that Annas is in view and that the courtyard (aulē) is the atrium connected with his house. The mention of a “girl on duty” confirms that the scene takes place outside the temple area, for there only men held such assignments (see also comments on 18:18). Caiaphas’s quarters may have shared the same courtyard, so that even the second stage of the investigation would have been relatively private (though with at least some Sanhedrin members present). The formal action taken by the Sanhedrin (at about dawn) is not recorded in John’s Gospel (cf. Matt. 27:1–2 par.).

The girl on duty … the girl at the door (18:16–17). On women gatekeepers, see 2 Samuel 4:6 (LXX) and Acts 12:13 (“servant girl named Rhoda”).550 The same word (paidiskē) is rendered “bondwoman” (in distinction from “free woman”) in Galatians 4:22–31. Apparently, the female doorkeeper was a domestic female slave, probably of mature age, since her responsibility required judgment and life experience.551

It was cold (18:18). Nights in Jerusalem, which is only half a mile above sea level, can be cold in the spring.

The servants and officials (18:18). The soldiers have returned to their barracks, entrusting the role of guarding Jesus to the temple guards.

A fire (18:18). The presence of a fire confirms that these preliminary proceedings against Jesus take place at night, when the cold would incite people to make a fire to stay warm. Even at night, fires were not normally lit,552 and night proceedings were generally regarded as illegal. Moreover, the fact that a fire was kept burning in the Chamber of Immersion so that the priests on night duty could warm themselves there and that lamps were burning even along the passage that led below the temple building (m. Tamid 1:1) suggest that the courtyard referred to in the present passage is private.

Jesus Before the High Priest (18:19–24)

The high priest (18:19). Again, Annas is referred to as “the high priest.” The appropriateness of such a designation even after he was removed from office is confirmed both by the Mishnah (where the high priest is said to retain his obligations even when no longer in office; m. Hor. 3:1–2, 4) and Josephus (where Jonathan is called high priest fifteen years after his deposition; J.W. 2.12.6 §243; cf. 4.3.7–9 §§151–60). There may even be an element of defiance in the Jewish practice of continuing to call previous high priests by that name, challenging the Roman right to depose officials whose tenure was to be for life according to Mosaic legislation (Num. 35:25). Apparently, the seasoned, aged Annas still wielded considerable high priestly power while his relatives held the title.

Questioned Jesus (18:19). The fact that Jesus is questioned—a procedure considered improper in formal Jewish trials where a case had to rest on the weight of witness testimony (e.g. m. Sanh. 6:2)—suggests that the present hearing is informal (see comments on 18:21). On the Sadducees’ reputation for judging in general, Josephus writes that “the school of the Sadducees … are indeed more heartless than any of the other Jews … when they sit in judgment” (Ant. 20.9.1 §199).

His disciples and his teaching (18:19). The question here addressed to Jesus indicates that the authorities’ primary concern is theological, though a political rationale is later given to Pilate (cf. 19:7, 12). The Jewish leadership seems to view Jesus as a false prophet (see later b. Sanh. 43a), who secretly entices people to fall away from the God of Israel, an offense punishable by death (Deut. 13:1–11).553 Apparently, Annas hopes Jesus might incriminate himself on those counts.

I have spoken openly to the world…. I always taught in synagogues or at the temple, where all the Jews come together. I said nothing in secret (18:20). Some see in the present statement an echo of the motif of Wisdom speaking to the people in public (Prov. 8:2–3; 9:3; Wisd. Sol. 6:14, 16; Bar. 3:37). More likely, Jesus is simply pointing to the public nature of his instruction, which has made it possible for the Jewish authorities to gather ample eyewitness testimony from those who have heard him teach. See further comment on “I said nothing in secret” below.

At the temple (18:20). This refers to the temple precints, variously translated “temple courts” or “temple area” in the NIV.

I said nothing in secret (18:20). Note the earlier acknowledgment by the people of Jerusalem that Jesus was “speaking publicly” (7:26). Jesus’ words here echo Yahweh’s in Isaiah 45:19; 48:16: “I have not spoken in secret.” Socrates answered his judges similarly: “But if anyone says that he ever learned or heard anything privately from me, which all the others did not, be assured that he is not telling the truth” (Plato, Apol. 33B). The Qumran community, by contrast, preferred secret teaching, as did the mystery religions.

Why question me? Ask those who heard me. Surely they know what I said (18:21). Jesus’ challenge is understandable especially if the questioning of prisoners was considered improper in his day (see comments on 18:19). This is further confirmed by the recognized legal principle that a person’s own testimony regarding himself was deemed invalid (see 5:31). While an accused could raise an objection (which had to be heard: see 7:50–51; see also the apocryphal story of Susanna), a case was to be established by way of testimony, whereby witnesses for the defendant were to be questioned first (m. Sanh. 4:1; cf. Matt. 26:59–63 par.). If the testimony of witnesses agreed on essential points, the fate of the accused was sealed. This violation of formal procedure strongly suggests that Jesus’ hearing before Annas is unofficial.

Ask those who heard me (18:21). Jesus is asking for a proper trial where evidence is established by interrogation of witnesses; the present informal hearing does not meet such qualifications. Such display of self-confidence before authority is in all likelihood startling. As Josephus tells us, those charged normally maintained an attitude of humility before their judges, assuming “the manner of one who is fearful and seeks mercy” (Ant. 14.9.4 §172).

One of the officials (18:22). The official (hypēretēs) in question is one of the temple guard who took part in Jesus’ arrest (cf. 18:3, 12).

Struck him in the face (18:22). This is not the only ill-treatment Jesus has to endure during his Jewish trial before the Sanhedrin. According to Matthew, “they spit in his face and struck him with their fists. Others slapped him” (26:67). The word used here (rhapisma) denotes a sharp blow with the flat of one’s hand (cf. Isa. 50:6 LXX). Striking a prisoner was against Jewish law.554 Compare the similar incident involving Paul in Acts 23:1–5, where the high priest Ananias ordered those standing near Paul to strike him on the mouth.

Is this the way you answer the high priest? (18:22). A proper attitude toward authority was legislated by Exodus 22:28: “Do not blaspheme God or curse the ruler of your people” (quoted by Paul in Acts 23:5). See also Josephus, Ag. Ap. 2.24 §§194–95: “Anyone who disobeys him [the high priest] will pay the penalty as for impiety towards God himself.”

If I said something wrong (18:23). Literally, “spoke in an evil manner,” that is, “if I said something that dishonored the high priest.” Jesus implicitly refers to the law of Exodus 22:28 (see previous comment) and denies having violated it. The LXX uses the expression “speak evil” for cursing the deaf and blind (Lev. 19:14), one’s parents (20:9), the king and God (Isa. 8:21), and the sanctuary (1 Macc. 7:42).

Then Annas sent him, still bound, to Caiaphas the high priest (18:24). Before Jesus can be brought to Pilate, charges must be confirmed by the official high priest, Caiaphas, in his function as chairman of the Sanhedrin.555 Just where the Sanhedrin met at that time is subject to debate.556 A mishnaic source specifies the Chamber of Hewn Stone on the south side of the temple court (m. Mid. 5:4), while the Babylonian Talmud indicates that the Sanhedrin ceased meeting in this location “forty years” (not necessarily a literal time marker; e.g., b. Yoma 39a) prior to the destruction of the temple, moving to the marketplace.557 Then again, “sent” need not imply movement to another building at all but may merely refer to changing courtrooms in the temple.

Peter’s Second and Third Denials (18:25–27)

A relative of the man whose ear Peter had cut off (18:26). Being one of Jesus’ disciples was not a legal offence, though it could have been surmised that open confession might lead to trouble, especially if Jesus is found guilty and executed (cf. 20:19). Of more immediate concern for Peter may have been the earlier incident in which he drew a weapon (perhaps carried illegally) and assaulted one of the high priest’s servants (Malchus). Peter’s denial of association with Jesus may therefore stem from a basic instinct of self-preservation and a self-serving desire on his part not to incriminate himself.

A rooster began to crow (18:27). While mishnaic legislation forbids the raising of fowl in Jerusalem (m. B. Qam. 7:7: “They may not rear fowls in Jerusalem”), it is unlikely this prohibition is strictly obeyed in Jesus’ day.558 Exactly when cocks crowed in first-century Jerusalem is subject to debate; estimates range from between 12:30 to 2:30 A.M. to between 3:00 and 5:00 A.M. Some have argued that reference is made here not to the actual crowing of a rooster but to the trumpet signal given at the close of the third watch, named “cockcrow” (midnight to 3:00 A.M.).559 If so, Jesus’ interrogation by Annas and Peter’s denials would have concluded at 3:00 A.M. See comments on 13:38.

Jesus Before Pilate (18:28–40)

The palace of the Roman governor (18:28). Jesus is led to the Praetorium, the headquarters of the Roman governor. While based in Caesarea in a palace built by Herod the Great (cf. Acts 23:33–35), Pilate, like his predecessors, made it a practice to go up to Jerusalem for high feast days in order to be at hand for any disturbance that might arise. It is unclear whether Pilate’s Jerusalem headquarters is to be identified with the Herodian palace on the western wall (suggested by the NIV’s “palace”) or the Fortress of Antonia (named after Mark Antony; Josephus, J.W. 1.21.1 §401) northwest of the temple grounds.560

FORTRESS OF ANTONIA

A model of the fortress, which stood in the northwest corner of the temple grounds.

Herod the Great had both palaces built, the former in 35 B.C. (on the site of an older castle erected by John Hyrcanus, see Josephus, Ant. 18.4.3 §91) and the latter in 23 B.C., whereby especially Philo identifies the (former) Herodian palace as the usual Jerusalem headquarters of Roman governors.561 Yet the discovery of massive stone slabs in the Fortress of Antonia in 1870 has convinced some that it is this building that is in view (see further comments on 19:13).562 On balance, the Herodian palace is more likely, especially in light of the above cited evidence from Philo and Josephus.563

Early morning (18:28). The expression “early morning” (prōi) is ambiguous. The last two watches of the night (from midnight to 6:00 A.M.) were called “cock-crow” (alektorophōnia) and “early morning” (prōi) by the Romans. If this is how the term is used here, Jesus is brought to Pilate before 6:00 A.M. This coheres with the practice, followed by many Roman officials, of starting the day very early and finishing the workday by late morning: “The emperor Vespasian was at his official duties even before the hour of dawn, and the elder Pliny, most industrious of Roman officials, had completed his working day, when Prefect of the Fleet, by the end of the fourth or fifth hour [i.e., 10:00 or 11:00 A.M.]. In Martial’s account of daily life at the capital, where two hours are assigned to the protracted duty of salutatio, the period of labores ends when the sixth hour begins [noon]. Even a country gentleman at leisure begins his day at the second hour [7:00 A.M.].”564 In light of Jewish scruples to try capital cases at night (see comments on 18:18), it is more likely that “early morning” means shortly after sunrise, when the Sanhedrin meets in formal session and pronounces its verdict on Jesus (Matt. 27:1–2 par.).

To avoid ceremonial uncleanness the Jews did not enter the palace; they wanted to be able to eat the Passover (18:28). Jews who entered Gentile homes were considered unclean,565 which would prevent them from celebrating the Passover. The present reference may not merely be to the Passover itself but to the Feast of Unleavened Bread, which lasted for seven days,566 in particular to the offering (hagigah) brought on the morning of the first day of the festival (cf. Num. 28:18–19). “Eat the Passover” probably simply means “celebrate the feast” (cf. 2 Chron. 30:21).567

PASSOVER SCENE

A model of the court of priests in the Jerusalem temple showing the altar of sacrifice.

Pilate (18:29). See “Pontius Pilate.”

Take him yourselves and judge him by your own law (18:31). Like Gallio after him (Acts 18:14–15), Pilate is not interested in being a judge of internal Jewish disputes.

But we have no right to execute anyone (18:31). Despite instances where the Jewish authorities are involved in executions, such as the stonings of Stephen (Acts 7) and of James the half-brother of Jesus in A.D. 62 (Josephus, Ant. 20.9.1 §200) and the burning of a priest’s daughter accused of committing adultery (m. Sanh. 7:2)—all of which involved lynch law or breaches of authority—the Sanhedrin did not have the power of capital punishment.568 As Josephus reports, “The territory of Archelaus was now [A.D. 6] reduced to a province, and Coponius, a Roman of the equestrian order, was sent out as procurator, entrusted by Augustus with full powers, including the infliction of capital punishment” (J.W. 2.3.4 §117).

The same writer tells of a case where the high priest had sentenced some people to death by stoning, a sentence that was protested by some apparently for the reason that the Sanhedrin did not have the authority to impose the death penalty during the period of Roman rule in Judea. Sure enough, the high priest was deposed for his presumption (Ant. 20.9.1 §§197–203). This comports with the acknowledgment in Talmudic literature that the Jews had lost this power “forty years” before the destruction of Jerusalem.569 Not only was this consistent with general Roman practice in provincial administration, capital punishment was the most jealously guarded of all governmental powers.570

Moreover, an equestrian procurator such as Pilate in an insignificant province like Judea had no assistants of high rank who could help him carry out his administrative and judicial duties. Thus, he must rely on local officials in minor matters while retaining the right to intervene in major cases, including “crimes for which the penalty was hard labor in mines, exile, or death.”571 Also, in handling criminal trials, the prefect or procurator was not bound by Roman law, which applied only to Roman citizens and cities. For this reason it is difficult to determine with certainty Pilate’s motives in offering to give the case back to the Jewish authorities.

Kind of death he was going to die (18:32). Crucifixion was looked upon by the Jews with horror, as when Alexander Jannaeus had eight hundred of his captives crucified in the center of Jerusalem.572 Execution on a cross was considered to be the same as hanging (Acts 5:30; 10:39), for which Mosaic law enunciated the principle, “Anyone who is hung on a tree is under God’s curse” (Deut. 21:23; cf. Gal. 3:13). If Jesus had been put to death by the Sanhedrin, stoning would have been the likely mode of execution, since that is the penalty specified in the Old Testament for blasphemy,573 the most common charge against Jesus in John. Other forms of capital punishment sanctioned by mishnaic teaching are burning, beheading, and strangling (m. Sanh. 7:1).

Pilate … asked him (18:33). In contrast to Jewish practice (see comments on 18:9 and 21), Roman law made provisions for detailed questioning of persons charged with crimes, whether they were Roman citizens (accusatio) or not (cognitio).574 These hearings were public and awarded the accused person with sufficient opportunity to defend himself against the charges, as seems to be presupposed in Jesus’ case by the Synoptics.

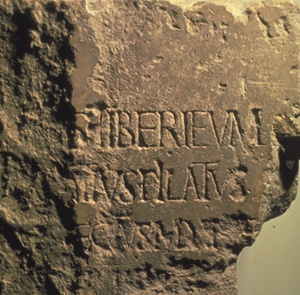

PONTIUS PILATE INSCRIPTION

The palace (18:33). See comments on 18:28.

Are you the king of the Jews? (18:33). “King of the Jews” may have been used by the Hasmoneans who ruled Judea prior to the Roman subjugation of Palestine. Josephus recounts that a golden vine or garden with the inscription “From Alexander, the king of the Jews” was given to the Roman general Pompey by Alexander, son of Alexander Jannaeus, and later transported to Rome and put in the temple of Jupiter Capitolinus (Ant. 14.3.1 §36). The title “king of the Jews” is also applied to Herod the Great (Ant. 16.10.2 §311).

Thus the designation “king of the Jews” has clearly political overtones, and Pilate’s question is designed to determine whether Jesus constitutes a political threat to Roman imperial power.575 Pilate’s gubernatorial tenure was punctuated by outbursts of ethnic nationalism, which rendered him ever more alert to potential sources of trouble, especially since Judea was “infested with brigands” (Ant. 20.10.5 §215) and “anyone might make himself king as the head of a band of rebels” (Ant. 17.10.8 §285).576

My kingdom is not of this world…. But now my kingdom is from another place (18:36). Earlier, Jesus refused people’s efforts to make him king (6:15). The answer given by the grandchildren of Jude, Jesus’ half-brother, at a trial before Domitian echoes Jesus’ words: “And when they were asked concerning Christ and his kingdom, of what sort it was and where and when it was to appear, they answered that it was not a temporal nor an earthly kingdom, but a heavenly and angelic one, which would appear at the end of the world” (Eusebius, Eccl. Hist. 3.20.6). Jesus’ description of the nature of his kingdom echoes similar passages in Daniel (e.g., Dan. 2:44; 7:14, 27).

My servants (18:36). The term rendered “servant” (hypēretēs) has previously been used for the temple police. In the LXX, the expression refers to the minister or officer of a king (Prov. 14:35; Isa. 32:5; Dan. 3:46) or even kings themselves (Wisd. Sol. 6:4: “servants of his kingdom”).

What is truth? (18:38). With this flippant remark, Pilate dismisses Jesus’ claim that he has come to testify to the truth and that everyone on the side of truth listens to him. Rather than being philosophical in nature, Pilate’s comment may reflect disillusionment (if not bitterness) from a political, pragmatic point of view. In his seven years as governor of Judea, he frequently clashed with the Jewish population. More recently, his position with the Roman emperor has become increasingly tenuous (see comments on 18:29).

He went out again to the Jews (18:38). Pilate returns to the outer colonnade (cf. 18:28–29).

I find no basis for a charge against him (18:38). (Cf. Luke 23:4.) Pilate’s thrice-repeated exoneration of Jesus (cf. 19:4, 6) stands in blatant contrast with the actual death sentence pronounced in deference to the Jewish authorities.

It is your custom for me to release to you one prisoner at the time of the Passover (18:39). Literally, “at Passover.”577 There is little extrabiblical evidence for the custom of releasing one prisoner at Passover. The practice may go back to Hasmonean times and may have been continued by the Romans after taking over Palestine.578 The release probably served as a gesture of goodwill designed to lessen political antagonism and to assure people that “no one coming to Jerusalem would be caught in the midst of political strife.”579 One mishnaic passage, which stipulates that the Passover lamb may be slaughtered for a variety of people whose actual condition is uncertain, including “one whom they have promised to bring out of prison” (m. Pesaḥ. 8:6), suggests that such releases were common enough to warrant legislation. Roman law provided for two kinds of amnesty: pardoning a condemned criminal (indulgentia) and acquitting someone prior to the verdict (abolitio); in Jesus’ case, the latter would have been in view.580

No, not him! Give us Barabbas! (18:40). Generally, Zealot-style political extremism was condemned. Yet here the Jews, at the instigation of the high priests, ask for the release of Barabbas, a terrorist, while calling for the death of Jesus of Nazareth, who has renounced all political aspirations. Apart from the irony of making such a one out as a political threat, this demonstrates both the influence the Sanhedrin had over the Jewish people at large as well as the Jewish authorities’ determination to have Jesus executed in order to preserve their own privileged position (11:49–52).

Barabbas (18:40). Nothing is known of this man apart from the Gospel evidence. “Barabbas” is not a personal name but a patronymic (like Simon Barjonah, i.e.,“son of Jonah”) that occurs also in the Talmud.581 Very possibly John saw in this designation a play on words: Bar-abbas literally means “son of the father,” and John has presented Jesus as the Son of the Father throughout the Gospel.

Taken part in a rebellion (18:40). Barabbas was a lēstēs (lit., “one who seizes plunder”). This probably refers not merely to a robber but to an insurrectionist, one who destabilized the political system by terrorist activity (cf. Mark 15:7). Luke indicates that Barabbas “had been thrown into prison for an insurrection in the city, and for murder” (Luke 23:19). Josephus frequently uses the term for those engaged in revolutionary guerilla warfare, who, harboring mixed motives of plunder and nationalism, roamed the Jewish countryside in those volatile days. The term applies particularly to the Zealots, who had made armed resistance against Rome the consuming passion of their lives and who were committed to attain to national liberty by all means, including risk of their own lives.582 In Matthew 27:16, Barabbas is characterized as “notorious” (episēmos), a word used by Josephus to describe Zealot leadership (John, son of Levi; J.W. 2.21.1 §585).