CHAPTER 8

Pericles and the City Gods

Nothing was more alien to the Greeks than the notion of a separation between Church and State. In Athens, the community provided a tight framework for religious manifestations while, symmetrically, religion was deeply embedded in civic life.1 Within this context, participation in the rituals was an action highly political—in the broadest sense of the term.

In the first place, religious practices shaped in the citizens a sense of belonging. When, at the end of the Peloponnesian War, the herald Cleocritus urged the Athenians to seek reconciliation after having torn one another apart, he appealed to the memory of that shared experience: “we have shared with you in the most solemn rites and sacrifices and the most splendid festivals, we have been companions in the dance and schoolmates and comrades in arms and we have braved many dangers with you both by land and by sea.”2 Every bit as much as warfare, religious festivals bonded the civic community together around practices and values shared in common.

Second, to manifest one’s piety also had a more specific political meaning, one that, this time, played on individual distinction rather than collective solidarity. To celebrate a cult or to dedicate offerings was a way of distinguishing oneself personally—as politicians were well aware. However, to make a show of too great a proximity to the gods was risky: excessive piety, in the same way as a detachment that was too manifest, might be regarded by the Athenians as a lack of moderation. It was all a matter of balance.

To analyze Pericles’ relations with the gods, one has to position oneself at the intersection of the general and the particular, where what was personal and what was shared by the whole community came together. On the one hand, the career of the stratēgos will illuminate the Athenians’ collective relationship to all that was divine. As a reelected stratēgos and a persuasive orator, Pericles was the spokesman of a civic religion that was undergoing a mutation. He was implicated in a policy of making constant offerings and of launching huge architectural religious works not only on the Acropolis but also throughout Attica; and, furthermore, he was engaged in such activities at a time when the city was introducing profound changes into its religious account of its origins—that is, autochthony—within a context of strained diplomatic relations.

On the other hand, the ancient sources made it possible to glimpse the personal relations that Pericles had developed with the gods. These were relations of proximity in the first place: he was sometimes depicted as a protégé of Athena, but in Attic comedies he was also assimilated to Zeus, in an analogy that was in no way flattering. But then, there were also relations that emphasized distance: some philosophical accounts presented him as a man close to the sophists or even as a freethinker. And, finally, there were relations involving irreverence: some later—and untrustworthy—sources made much of several trials for impiety in which those close to him were involved, and this raises the question of religious tolerance in fifth-century Athens and, in particular, how far individuals enjoyed freedom of thought when faced with the civic community.

A SPOKESMAN FOR THE CIVIC RELIGION: COLLECTIVE RELATIONS WITH THE GODS

In Athens, the city regulated religious expression down to the smallest details. The Assembly concerned itself with sacred affairs at regular intervals, and it was the Assembly that fixed the salaries of certain priests and priestesses and was also empowered to accept new cults.3 Symptomatic of this overall civic control was the fact that the gods’ money could sometimes spill over into the community coffers. Between 441 and 439 B.C., the city borrowed funds from the treasury of Athena in order to cope with the expenses incurred in the long conflict with Samos.4 And in the speech that he delivered on the eve of the Peloponnesian War, Pericles himself presented, as a financial reserve, the heap of offerings that had accumulated on the Acropolis, at the same time accepting responsibility for restoring to the goddess the sum borrowed, once the hostilities came to an end.5

At the same time, though, religious rituals were ensconced at the very heart of the democratic institutional framework. When meetings took place in the Assembly, debates never began until the Pnyx had been purified by a sacrifice and the herald had pronounced blessings and curses too. On the tribunes, orators always had to wear a wreath, as did participants in a sacrifice. As for the juries in popular lawcourts, they pronounced a solemn oath, swearing by Zeus, Poseidon, and Demeter to give their verdict in accordance with the city laws.

Religion and Politics: A Festive Democracy

As a magistrate, Pericles participated fully in this rich and intense civic religion. The presence of Athenian magistrates was required at numerous rituals. At the opening ceremony of the Great Dionysia, the ten stratēgoi all offered libations. They played a prominent part in the Panathenaea procession and were presented with the portions that were reserved for them from the first sacrifice in honour of Athena.6 We even know that in the fourth century they were responsible for no fewer than eight sacrifices a year.

In his capacity as a stratēgos, Pericles was thus an actor in an intensely festive democracy. In his funeral speech of 431, he acknowledges this fact: “We have a succession of competitions and religious festivals throughout the year.”7 Although it delighted the democrats, this plethora of religious celebrations aroused hostility among the oligarchs. In a violent pamphlet composed between 430 and 415, the anonymous author of The Constitution of the Athenians—known as the Old Oligarch—regarded it all as specifically Athenian and typical of a debased mode of government. According to this author, the increasing number of festivals caused serious institutional problems, constantly interrupting the handling of important affairs:

Objections are raised against the Athenians because it is sometimes not possible for a person, though he sit about for a year, to negotiate with the council or the assembly. This happens at Athens for no other reason than that, owing to the quantity of business, they are not able to deal with all persons before sending them away. For how could they do this? First of all they have to hold more festivals than any other Greek city (and when these are going on it is even less possible for any of the city’s affairs to be transacted).8

Although it may be true that, placed end to end, the Athenian festivals occupied no less than one-third of the year, this was, to say the least, an exaggerated way of putting the matter. Only the major celebrations, such as the Great Dionysia and the Panathenaea involved the whole community and led to the suspension of institutional business.

More serious still, according to this ferocious opponent of democracy, these festivals were designed simply to redistribute public wealth to the most poverty-stricken of the citizens. “The Athenian populace realizes that it is impossible for each of the poor to offer sacrifices, to give lavish feasts, to set up shrines and to manage a city that will be beautiful and great, and yet the populace has discovered how to have sacrifices, shrines, banquets and temples. The city sacrifices at public expense many victims, but it is the people who enjoy the feasts and to whom the victims are allotted.”9

In his view, the sole purpose of the religious festivals was to allow the people to indulge themselves whenever possible, at the expense of the city—that is to say, the wealthiest citizens.

According to his detractors, Pericles’ actions simply aggravated this state of affairs. Plutarch tells us that the stratēgos increased the number of religious banquets and entertainments in order to curry favor with his fellow-citizens: “At this time, therefore, particularly, Pericles gave the reins to the people and made his policy one of pleasing them [pros kharin], ever devising some sort of a pageant in the town for the masses, or a public meal [hestiasin], or a procession ‘amusing them like children with delights in which the Muses played their part.’”10 Echoing a tradition hostile to the stratēgos, as it does, the preceding description is clearly much exaggerated if one bears in mind that no religious festival was created on Pericles’ initiative except, possibly, the one in honor of Bendis, a deity of Thracian origin.11

The fact nevertheless remains that the stratēgos did reorganize certain celebrations. He is said to have introduced a music competition into the already extremely crammed festive ritual calendar, at the time of the Panathenaea, adding a whole day to this, the most important of all the Athenian festivals.12 But even this addition should be viewed with circumspection; in all probability, Pericles simply reorganized an earlier musical competition, moving it into the Odeon and possibly giving it official status.13 However, even if the action of the stratēgos was more limited than Plutarch suggests, it does testify to a real desire to democratize mousikē, the culture of the Muses that was in principle reserved for the Athenian elite.

However, the oligarchs’ attacks focused less on the festivals supposedly instituted by Pericles than on the program of constructions in which they were to take place. On this score, they criticized him for acting in the manner of a munificent tyrant.

Great Works in the Service of the Gods

The architectural program of the “great works” is closely associated with the name of Pericles. The impetus for this ambitious policy of monumental building is well known: in 448, the stratēgos convened a congress of the Greek cities of Europe and Asia, to discuss the issues of the temples destroyed by the Persians, the sacrifices due to the gods, freedom of navigation, and peace. It was in the aftermath of the Persian Wars that they had vowed not to reconstruct those devastated sanctuaries, so as to preserve forever the memory of the impiety of the Persians.14 In less than twenty years, numerous building sites were set up and, in many cases, completed. As well as a total remodeling of the Acropolis, a number of sanctuaries underwent more or less spectacular transformations: in eastern Attica, the sanctuary of Artemis at Brauron was given a double portico; and in the west, a new initiation hall (telesterion) was inaugurated at Eleusis.15 Meanwhile, a number of medium-sized temples were constructed throughout the territory in honor of a variety of deities: Poseidon was honored at Sunium, in the south; Nemesis at Rhamnous and Ares at Acharnae, in the north; Athena at Pallene in central Attica; and, finally, Hephaestus in the town of Athens itself, on the hill overlooking the Agora. All these finely wrought buildings with clearly similar stylistic features were probably executed by the same architect.16 In this way, in the space of twenty years the whole of Attica was affected by this epidemic of monuments.17

At this point, a historian is faced with two questions. First, what was Pericles’ precise role in this transformation of the Athenian religious landscape? It is a question that calls for a nuanced reply. Far from acting as an all-powerful demiurge, the stratēgos was, in reality, simply one of many actors involved in this architectural metamorphosis. Strictly speaking, only the Parthenon, the statue of Athena Parthenos, the Propylaea, the Odeon, and the Telesterion at Eleusis can be credited to him.18

Next, did all this involve a radical break from earlier building practices? In those few operations of his, Pericles conformed to an already well-established tradition: a few years earlier, his rival, Cimon, had launched the construction of a great public sanctuary in the Agora, the Theseum, after having the bones of its founder brought back from the island of Skyros19 with great pomp and ceremony. However, two major novelties characterized this Periclean moment. In the first place, the very scope of the operation was unmatched, with so many building sites being set up simultaneously throughout the territory; and furthermore, the new buildings testified as much to the city’s domination over its allies as to the Athenians’ piety toward their gods. Between 450–440, Athenian imperialism took to expressing itself in religious terms. As early as 450, Athens forced the cities belonging to the Delian League to take part, every four years, in the Great Panathenaea held in honor of Athena, bringing with them a heifer and a panoply as offerings to the goddess.20 Then, in the 440s, the city confirmed its religious hold even beyond Attica, insisting on the construction of a number of sanctuaries of Athena on land seized from the allies, as is testified by several boundary markers discovered in Aegina, Chalcis, Cos, and Samos.21

Although Athena, the guardian goddess of the whole community, was the principal beneficiary of these grandiose building sites, marginal deities in the Greek pantheon were also honored. In this respect, Hephaestus was particularly favored, for he received a magnificent temple in the Agora, ensconced at the very heart of the Athenian democratic system. Nor was this choice at all fortuitous, for it should be understood in the light of the great story about autochthony and the origins of Athens, which was being reconstructed in this same period.

Reconstruction of the Myth of Autochthony

All the indications suggest that this great story of origins took shape in its definitive form between 450 and 430, at the very time when Pericles was in power and the religious building sites were springing up all over Attica.22 It was at this point—not earlier, as is sometimes argued—that the Athenians began to proclaim themselves to be born from the earth, so that they were all, collectively, the descendants of the king Erechtheus, who was born from the very soil of Attica.23

To understand how this belief, central to Athenian imaginary representations, came to be elaborated, we must start with a comment on vocabulary. In the fifth century, the term autokhthōn did not mean people “born from the earth,” but simply people who had lived on their territory from time immemorial, without ever migrating.24 According to Herodotus, such were the cases of the Arcadians in the Peloponnese, the Carians in Ionia, and the Ethiopians and Libyans in Africa.25 The Athenians also belonged to this category since, already by the time of the Second Persian War, they were claiming to have lived always in Attica.

Furthermore, the Athenians had long believed that one of their earliest kings was born from the earth (gēgenēs), as is attested by the following lines from the Iliad: “And they that held Athens, the well-built citadel, the land of great-hearted Erechtheus, whom of old Athene, daughter of Zeus, fostered, when the earth, the giver of grain, had borne him.”26 The story of Erechtheus is well-known to us thanks to the eponymous tragedy by Euripides, written in the late fifth century. Seized by a violent desire for Athena, the lame Hephaestus attempted, unsuccessfully, to rape her. His semen did spatter the goddess’s thigh, however, and she grabbed a twist of wool (eru) to wipe her leg, and then dropped it on the Attic ground (khthon). From that fertilized earth, Erechtheus emerged and was received and raised by Athena.27

There is, however, nothing to prove that, as early as the Archaic period, the Athenians were considering themselves to be the descendants of Erechtheus. To believe in a king born from the soil is one thing; to believe yourselves, collectively, to be his descendants is quite another. It was not until the time of Pericles that the Athenians took to presenting themselves as the offspring of Erechtheus, thereby giving a new sense to the notion of autochthony. After a first fleeting appearance in the Eumenides of Aeschylus, the theme was developed by Sophocles in his Ajax, in the 440s. Here, the Athenians were presented as men born from the earth, the offspring of Erechtheus. It was at that point, and only then, that the various elements in the story of autochthony fused together, enabling the citizens to pride themselves on not only having always lived on the land of their fathers—their fatherland—but also being directly descended from their mother earth, their motherland.28

Autochthony, now part and parcel of the Athenian identity, functioned as a tale of collective ennoblement. This prestigious birth conferred upon the Athenians a very particular solidarity: since they all shared the same mother, they were all brothers; and on a social and ritual level, this was expressed by the phratries that united them all under the patronage of a common ancestor. Outside Athens, this belief justified them thinking that they were superior to other cities which, as Euripides put it, “were made up of elements imported from many origins, like counters set out on a chequer-board.”29

It was this imaginary context that made sense of the construction, in the early 440s, in the Agora, of a building consecrated to Hephaestus and Athena. Even though the temple was completed only after the peace of Nicias in 421 and the cult statues were not installed until 416/415, the project and the early stages of the construction work were, if not Periclean, at least of the Periclean period.30 This edifice, built entirely of marble, was by far the most luxurious in the Agora, and its sculpted ornaments spread over a larger area than any other Doric temple in the Greek world, except for the Parthenon. The splendor of the temple was matched by the munificence of the festival introduced in 421, when the great building was completed. It included a solemn procession, a torch-race between the tribes, imposing sacrifices and, possibly, a musical competition. The Hephaesteia celebrated the lame god with a lavishness unequaled anywhere in the Greek world.

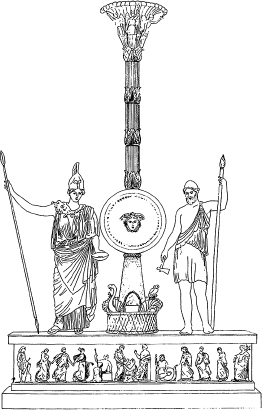

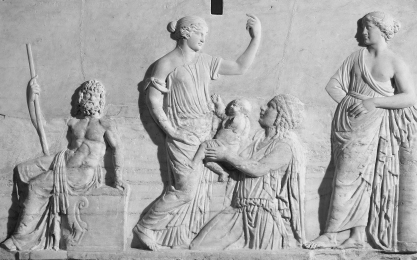

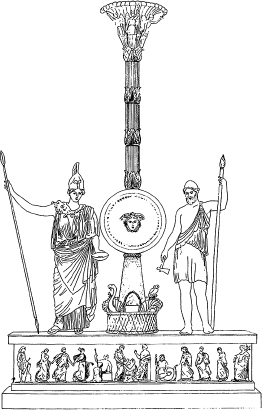

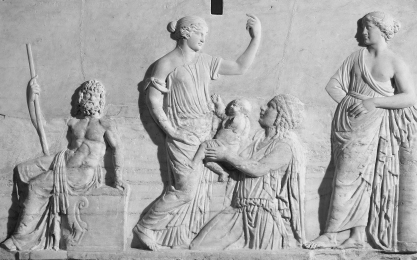

While the celebration of Athena is perfectly explicable, should we not be astonished at such a sumptuous outlay being devoted to “a rather secondary god”?31 We should indeed be somewhat surprised if, as a deeply rooted historiographical tradition has it, Hephaestus was celebrated in the Agora simply as the patron of craftsmen. The craftsmen, who were concentrated within the Ceramicus quarter, did certainly play a major role in the Athenian city, and it was probably by no means by chance that the decree relating to the organization of the Hephaesteia was proposed by an owner of craftsmen slaves who had made a fortune, Hyperbolus.32 Nevertheless, it would be mistaken to reduce the significance of the festival and the edifice solely to a celebration of the craftsmanship of Athens. The celebrations did not give blacksmiths and potters pride of place, but mobilized the tribes of the entire city, without privileging any particular category. And even if the metics, of whom there were many among the craftsmen, did take part in the ceremony, they did so in a minor role: they received no more than a portion of raw meat and did not have access to the sacrificial feasts, which were reserved solely for citizens. The point is that, in the Agora, Hephaestus and Athena were honored not simply as the patrons of the craftsmen, but as the protagonists in the story of autochthony that had now been rearticulated. Significantly enough, the base upon which the statues of the cult of Hephaestus and Athena rested represented the birth of Erechtheus (figures 7 and 8).33

Admittedly, Pericles’ personal involvement in the enterprise is not documented; even if the building site was set up in his lifetime, the festival in honor of Hephaestus was not established until eight years after his death. More troubling still, the stratēgos said not a word about the divine ancestry of the Athenians in the funeral oration that he delivered in 431, in which he went only so far as to mention the remarkable stability of the Athenian populace ever since its origins: “This land of ours, in which the same people have never ceased to dwell [aei oikountes] in an unbroken line of successive generations, [our ancestors] by their valor transmitted to our times as a free state.”34 Rather than put this down to a hypothetical memory lapse on the part of Thucydides, we should recognize that that lacuna could have been deliberately planned. For this speech, Pericles had decided to opt for an erotic vocabulary rather than an ancestral one, in order to describe the Athenians: he wanted his fellow-citizens to fight for the city as erastai would for their erōmenoi, not as sons defending their earth-mother.35

FIGURE 7. Hephaisteion statue-group (ca. 421 B.C.), as reconstructed by Evelyn Harrison. Evelyn B. Harrison, “Alkamenes’ Sculptures for the Hephaisteion: Part I, The Cult Statues.” American Journal of Archaeology, 81, 2 (1977): 137–178. Courtesy of Archaeological Institute of America and American Journal of Archaeology.

FIGURE 8. Copy of the bas-relief sculpture of the Hephaisteion statue-group. Musée du Louvre; Galerie de la Melpomène (Aile Sully). Rez-de-chaussée—Section 15. No. d’inv. MR 710 (no. usuel Ma 579). Paris, Musée du Louvre. © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée du Louvre) / Hervé Lewandowski.

Nevertheless, one detail does show the stratēgos’s personal interest in the autochthony tale: the iconography of the statue of Athena Parthenos. Ensconced at the heart of the Parthenon, this immense effigy, over eleven meters high from top to toe, constituted “as it were a brief recapitulation of Periclean themes.”36 According to Pausanias (1.24.7), “Athena … holds a statue of Victory about four cubits high, and in the other hand a spear; at her feet lies a shield and near the spear is a serpent. This serpent would be Erichthonius.” In this way, at the feet of the goddess there stood the first Athenian, born from the earth, for whom the city set up a cult on the Acropolis, in the Erechtheum, which was rebuilt shortly after the stratēgos’s death.

It turns out that Pericles was more the herald of civic religion than its hero. Even if he was actively involved in the ritual functioning of the community, his personal influence remained limited. He created no new festivals and was responsible for the construction of no sanctuary (for the Parthenon and the Odeon were not temples, in the ritualistic sense of the term). As for his direct involvement in the rehandling of the autochthony story, that cannot be confirmed. The stratēgos was thus a spokesman for the civic religion rather than its high priest.

But quite apart from this role as an intermediary, Pericles maintained with the gods personal relations that the sources take into account, allowing us to catch a glimpse of his religious convictions or, at least, of the beliefs ascribed to him, sometimes in order to glorify him, but often so as to denigrate him.

THE POSSESSOR OF AN EQUIVOCAL) PIETY: A PERSONAL RELATIONSHIP WITH THE DEITY

The Divine Pericles

According to the ancient sources, Pericles had established privileged links with several deities in the pantheon. At the time of the construction of the Propylaea, the monumental entrance to the Acropolis (437–433 B.C.), the stratēgos benefited from the personal care of Athena, the poliadic, or City deity. During the construction work, the most zealous of the workmen slipped and fell from the top of the edifice. “He lay in a sorry plight, despaired of by the physicians. Pericles was much cast down by this, but the goddess appeared to him in a dream and prescribed a course of treatment for him to use, so that he speedily and easily healed the man. It was in commemoration of this that he set up the bronze statue of Athena Hygieia on the acropolis near the altar of that goddess, which was there before.”37

At first sight, there is nothing exceptional about this dream. There was a well-known practice known as incubation that consisted in the sick receiving in their dreams a visit or revelations from the deity Asclepius. But such dreams came about only after the accomplishment of a well-established ritual: first, only the sick person could ask for a dream; then the god appeared in the sanctuary only after the appropriate rituals had been performed; and finally, the sick man never himself interpreted the signs that were sent to him, for that task fell to the deity’s priests.38 Nothing of the kind happened in the case of Pericles’ dream: Athena visited the stratēgos outside any ritual framework, short-circuiting the traditional mediations and leaving the dreamer and the goddess face to face. The anecdote thus places Pericles in a privileged position vis-à-vis the goddess, “as a mediator and quasi-diviner between the goddess and the wounded man.”39

That transaction operated, as was often the case, according to the logic of a gift and a counter-gift. The first gift—the monumental transformation of the Acropolis—elicited from Athena a response in the shape of a dream sent privately to the stratēgos. In return, Pericles offered her a new consecration, which not only completed the exchange cycle, closing it upon itself, but also commemorated forever his special close relations with the goddess. It is quite clear that Plutarch was making the most of an embellished story: the dedication of the statue of Athena Hygieia discovered by the archaeologists makes no mention at all of the stratēgos and refers only to the Athenians; the individual is effaced when confronted by the collectivity which, in the fifth century, banned all excessive forms of personal distinction. The fact nevertheless remains that the anecdote testifies to a tradition that is favorable to Pericles, since it draws attention to the divine protection that he enjoyed—as did Odysseus in the Odyssey.

To draw attention to such a proximity to the gods was nevertheless a risky business, for the Athenians might interpret it as a sign of concealed tyrannical ambitions. The Pisistratids had boasted of their privileged relations with the goddess and Pisistratus had seized power escorted by a false Athena, at the culmination of a ruse that was never to be forgotten.40 Was Pericles too close to the gods? That was precisely the notion that his detractors sought to instill in the minds of the Athenians.

His opponents sometimes identified him with Dionysus, “king of the satyrs,”41 but it was to Zeus that the stratēgos was most frequently assimilated. This was a way of suggesting that Pericles had overstepped the boundaries of the human condition and had tipped over into overweening hubris. Plutarch was well aware of the accusation implied by such an association, and he endeavored explicitly to neutralize such attacks: “it seems to me that his otherwise puerile and pompous nickname [of “Olympian”] is rendered unobjectionable and becoming by this one circumstance, that it was so gracious a nature and a life so pure and undefiled in the exercise of sovereign power.”42 What could be more unsuitable, in a democracy, than a man who took himself for a god—worse still, the king of the gods?

That identification was all the more problematic given that, in Athenian theater, Zeus was often portrayed as a despot who heeded nothing but his own desires: in Prometheus Bound, Aeschylus (or Pseudo-Aeschylus) even depicted Zeus as a tyrant usurping power in order to set up his own whims as laws (409), without any need for justification (324). So the poet Cratinus aimed to create alarm when he chose to identify Pericles with the most powerful of all the gods: “Faction [stasis] and Old Cronos were united in wedlock; their offspring was of all the tyrants the greatest and lo! he is called by the gods the head-compeller.”43 Such a comparison turned the stratēgos into an unscrupulous usurper, prepared to do anything in order to hang on to power.

Cratinus repeated that same accusation, making it more pointed, in his play titled The Spirits of Wealth, which was performed in 430–429, at the time when Pericles was under attack from all quarters for his handling of the war: “Here is Zeus, chasing Cronos from the kingship and binding the rebellious Titans in unbreakable bonds.”44 Through this analogy, the comic poet covertly evoked the ostracism of Cimon, in 462/1: confronting Zeus/ Pericles, Cimon was identified with Cronos, a benevolent sovereign, ousted by his son. As it happened, the parallel was flattering to Pericles’ fallen rival, for ever since Hesiod, the reign of Cronos had evoked the golden age when “the grain-giving field bore crops of its own accord, much and unstinting, and they themselves, willing, mild-mannered, shared out the fruits of their labours, together with many good things.”45 With this analogy, the comic poet recalled the proverbial generosity of Cimon, which Plutarch carefully assesses: “[Cimon] made his home in the city a general public residence for his fellow citizens, and on his estates in the country allowed even the stranger to take and use the choicest of the ripened fruits, with all the fair things that the seasons bring. Thus, in a certain fashion, he restored to human life the fabled communalism of the age of Cronos—the golden age.”46 In this game of masks, the comparison proved extremely disadvantageous to Zeus-Pericles, who, by getting rid of Cronos-Cimon is implied not only to have established an unjust tyranny but also to have brought about the end of the golden age.

There was another reason why this “pantheonization” was particularly unpleasant: by being assimilated to Zeus, Pericles was represented as a flighty lover who disrupted family life. In this respect, Zeus’s reputation was by now certainly well established. Seducing both mortals and immortals as he pleased, he had engendered many bastards all over the world. So it was certainly not by chance that Aspasia was herself seen as Zeus’s irascible wife Hera : “And Sodomy [katapugosunē] produced for Cronos this Hera-Aspasia, the bitch-eyed concubine.”47 Inevitably, the analogy rebounded against the stratēgos’s partner and also his bastard son, Pericles the Younger.

These often alarming and sometimes grotesque jokes cracked by the comic poets were intended to provoke laughter and alarm among the spectators and, as such, were inclined to reflect the fantasies of Pericles’ opponents rather than Pericles’ own religious thinking. In order to get some idea of his own deeper convictions, we need to turn to other sources that are, unfortunately, equally biased.

A Clear Head or a Weak Mind?

In the few accounts that bear upon his personal beliefs, Pericles appears to be torn between two diametrically opposed positions. At one moment, the stratēgos is presented as a defender of rationalist thinking, cursorily dismissing all supernatural interpretations; at other times, he is presented as a supporter of traditional religion or even a religion that never looked beyond superstition.48 Choosing between these two alternatives, many contemporary historians have often seemed to favor the former, even going so far as to represent Pericles as an aufklärer (an enlightenment figure), the herald of a world moving toward secularization.49

It is true that several anecdotes portray the Athenian leader as an enlightened disciple of the sophists, stripping the world of its enchanted aspects, the better to mock all divine omens. In 430, when a fleet of vessels was about to set sail under his orders, “It chanced that the sun was eclipsed and darkness came on and all were thoroughly frightened, looking upon it as a great portent. Accordingly, seeing that his steersman was timorous and utterly perplexed, Pericles held up his cloak before the man’s eyes, and, thus covering them, asked him if he thought it anything dreadful or portentous of anything dreadful. ‘No,’ said the steersman. ‘How then,’ said Pericles, ‘is yonder event different from this, except that it is something rather larger than my cloak which has caused the obscurity?’”50 It is a very nice story, but it has no historical basis since no eclipse of the sun is attested in that year.51

How should we interpret this cobbled-together anecdote? In order to understand it, we need to replace the story in the context in which it was circulated—that of the philosophical schools, according to Plutarch (Pericles, 35.2). The story was of a moral rather than a historical nature. The point was to set in contrast, term for term, the enlightened behavior of Pericles and the hidebound attitude of one of his unfortunate successors, Nicias. In late August 413, while in command of the Athenian troops massed against Syracuse, Nicias was confronted with a total eclipse of the moon. Faced with this omen, he dithered helplessly for several whole days, “spending his time making sacrifices and consulting diviners, right up until the moment when his enemies attacked.”52 That long delay had grave consequences, for it led to the rout of the Athenians at Syracuse and eventually decided the outcome of the war. So these two episodes reflected two leaders, two different attitudes, and two moments in Athenian history: the glorious start of the Peloponnesian War and the ignominious conclusion of the expedition to Sicily, and an implicit contrast was drawn between them.

Another account relayed by Plutarch tended to represent Pericles as, if not a sophist, at least a man close to them: “A certain athlete had hit Epitimus the Pharsalian with a javelin, accidentally, and killed him, and Pericles squandered an entire day discussing with Protagoras whether it was the javelin, or rather the one who hurled it, or the judges of the contests that ‘in the strictest sense,’ ought to be held responsible for the disaster.”53 Some historians believe that this passage confirms the stratēgos’s sympathy for the inflammatory ideas of the sophist Protagoras of Abdera. He had written a treatise titled On the Gods, in which he maintained that “man is the measure of all things” and even defended a number of agnostic ideas: “As to the gods, I have no means of knowing either that they exist or that they do not exist. For many are the obstacles that impede knowledge, both the obscurity of the question and the shortness of human life.”54

However, this supposed complicity between Pericles and Protagoras remains unverifiable. First, no source from the classical period even mentions it. The fact that Protagoras may have played some role in the founding of Thurii—for which he may have drawn up laws—does not necessarily prove that he was an adviser to the stratēgos.55 Besides, even if the anecdote recorded by Plutarch was true, the conversation was not about the gods but about irrelevant philosophico-juridical considerations. Finally, even Plutarch himself admits that he is recording biased or even untruthful words, for it was Xanthippus who was spreading this story, with the explicit intention of harming his father (36.4).

After examining the sources, we still have found nothing to suggest that Pericles was a visionary who rejected all forms of superstition. To be sure, the stratēgos did keep company with Anaxagoras and was in touch with other sophists who were living in Athens. But that does not mean to say that he accepted all their beliefs. On the contrary, Pericles was keen to show that he was not the captive of any doctrine and, besides, his close acquaintances also included men who held the most traditional of religious beliefs. Revealingly enough, it was the seer Lampon that the stratēgos chose as the founder of Thurii, not Protagoras, although the latter also took part in the expedition.

Plutarch tells us that the stratēgos did sometimes manifest superstitious beliefs. In 429, when struck down by the plague, he was assailed by “a kind of sluggish distemper that prolonged itself through various changes, used up his body slowly and undermined the loftiness of his spirit” (Pericles, 38.1). At this point, his clear head was supposedly taken over by a weak mind: “Pericles, as he lay sick, showed one of his friends who was come to see him an amulet that the women had hung round his neck. [Theophrastus saw this as a sign] that he was very badly off to put up with such folly as that” (Pericles, 38.2). According to Aristotle’s successor, Pericles forwent all control over his mores, abandoning himself to beliefs that were the more discredited for being associated with the world of women.56 That demeaning story, which was doing the rounds in the philosophical schools, should be regarded with the utmost circumspection, since Plutarch, for his part, relates an alternative version of the death of the stratēgos that, on the contrary, transforms his death-throes into a most edifying scene. Although he missed out on a heroic death on the battlefield, the stratēgos is reported to have displayed an unshakeable lucidity right up to his dying breath, when he delivered one last calm message to his friends gathered about him.57

Pericles is portrayed now as a strong-minded man who pours ridicule on divine omens and is in communication with the sophists, now as a weak-minded individual abandoning himself to superstition. The fact is, though, that these contrasting pictures tell us more about the preoccupations of the philosophers than about Pericles’ personal beliefs. Among the philosophical schools, Pericles became a stylized ideal type identified with one of the sharply defined caricatures of figures that Theophrastus sketched in so cleverly in his Characters.58

In The Life of Pericles, one passage conveys this tension particularly sharply:

A story is told that once on a time the head of a one-horned ram was brought to Pericles from his country-place, and that Lampon the seer, when he saw how the horn grew strong and solid from the middle of the forehead, declared that, whereas there were two powerful parties in the city, that of Thucydides and that of Pericles, the mastery would finally devolve upon one man—the man to whom this sign had been given. Anaxagoras, however, had the skull cut in two and showed that the brain had not filled out its position but had drawn together to a point, like an egg, at that particular spot in the entire cavity where the root of the horn began. At that time, the story says, it was Anaxagoras who won the plaudits of bystanders; but a little while after it was Lampon, for Thucydides was overthrown and Pericles was entrusted with the entire control of all the interests of the people.59

Here too, the story is unreliable, and its elegant symmetry may well arouse legitimate suspicion in the mind of a reader. All the same, one element in the account does ring true: Pericles does not himself choose between the two suggested interpretations. It is the others present who pronounce on the matter, initially inclining to favor Anaxagoras but then having second thoughts about the matter and swinging back to rally to Lampon. Throughout this process, the stratēgos himself remains obstinately out of view. Does this, once again, testify to the prudence of Pericles, who never commits himself unless it is absolutely necessary or unless it is in his precise interest to do so? That is perfectly possible, but there is another possible hypothesis. If the stratēgos refrained from expressing a preference, that may have been because he saw no obvious contradiction between the two explanations. Plutarch confirms this possibility in the conclusion to the anecdote: “There is nothing, in my opinion, to prevent both of them, the naturalist and the seer, from being in the right of the matter; the one correctly divined the cause, the other the object or purpose.”

But, in truth, was Pericles a freethinker or of a traditionalist cast of mind? He may have been both, either alternately or simultaneously. The two attitudes were not as contradictory as is suggested by some of the public pronouncements made by either the sophists or the Hippocratic doctors; the latter were prone to emphasize such a contradiction the better to justify their own practices before an audience that they had to convince.60 In reality, in the Greek world, there was no clear dividing line between rationality and “superstition”; in the fifth century, Hippocratic medicine and healing rituals functioned in parallel and for most of the time cohabited without clashing.61 Making offerings, taking part in festivals, believing in prophetic dreams, trying out experimental remedies, and observing natural phenomena without any reference to any other world were all modes of behavior or interpretation that could coexist perfectly well, not only in Greek society generally but also within a single individual who, depending on the context, would turn to the experiences that seemed most appropriate in the prevailing circumstances.

However, even if Pericles did not see these different beliefs as contradictions, that was not necessarily the case for all his fellow-citizens. There is evidence to suggest a certain hardening in religious matters in the 430s, as the political and diplomatic climate became progressively more difficult. According to certain sources, this was when several of those close to the stratēgos were charged with impiety in the lawcourts.

The Problem of Impiety

The increase in the number of impiety trials in Pericles’ time is a matter of historiographical debate. The fact is that this question involves adopting a definite position on the very nature of Athenian democracy. To accept their existence is to believe that this “Age of Enlightenment” was also a time of religious persecution, even before the Peloponnesian War brought about a hardening of attitudes. To reject it is to defend the irenic version of a tolerant and open democratic Athens. Depending on the view adopted, the trial of Socrates in 399 becomes either the climax of a series of attacks launched by the democracy against “freethinkers” or else an altogether exceptional case that can be explained by the philosopher’s provocative behavior in a context of political tension.62

The documentation is fraught with pitfalls, but along with many question marks, some things are clear. The first certainty is that Pericles’ reputation was murky on account of his maternal ancestors. As a member of the Alcmaeonid family, the stratēgos was sullied by the pollution of ancestors who had dared to massacre suppliants who had taken refuge on the Acropolis.63 Shortly before the Peloponnesian War, the Spartans had seized the opportunity to reactivate the memory of this embarrassing episode:

It was this “curse” that the Lacedaemonians now bade the Athenians drive out, principally, as they pretended, to avenge the honour of the gods, but in fact because they knew that Pericles, son of Xanthippus, was implicated in the curse on his mother’s side, and thinking that, if he were banished, they would find it easier to get from the Athenians the concessions they hoped for. They did not, however, so much expect that he would suffer banishment, as that they would discredit him with his fellow-citizens, who would feel that to some extent his misfortune would be the cause of the war.64

That inherited pollution was clearly at the origin of all the accusations made in Athens against the stratēgos.

The second certainty: Spartan propaganda never succeeded in harming him directly. No lawsuit was ever brought against him and, according to the orator Lysias, Pericles was even passed down to posterity as a model of piety: “Pericles, they say, advised you once that in dealing with impious persons you should enforce against them not only the written but also the unwritten laws … which no-one has yet had the authority to abolish or the audacity to gainsay—laws whose very author is unknown; he judged that they would thus pay the penalty not merely to men, but also to the gods.”65 So Pericles was represented as promoting a strict, even intransigent view of piety, and urging his fellow-citizens to punish offenders even more severely than was prescribed by law. That astonishing excessiveness should probably be ascribed to the very suspicion of impiety that surrounded him.

According to the ancient sources, his opponents, foiled in their attempts to damage Pericles in person, resorted to bringing charges of impiety (asebeia) against several of those close to him: the sculptor Phidias, Pericles’ partner, Aspasia, and his teacher, Anaxagoras. It is at this point that a historian is obliged to abandon the solid ground of certainties and venture into the fogs of speculation and hypothesis.

Let us start with the misadventures of the sculptor Phidias. In The Life of Pericles (31.4), Plutarch reports that “when he wrought the battle of the Amazons on the shield of the goddess [belonging to the statue of Athena Parthenos], he carved out a figure that suggested himself as a bald old man lifting on high a stone with both hands, and also inserted a very fine likeness of Pericles fighting with an Amazon. And the attitude of the hand, which holds out a spear in front of the face of Pericles, is cunningly contrived as it were with a desire to conceal the resemblance, which is, however, plain to be seen from either side.” Having discovered this subterfuge, citizens were apparently revolted by this transgressive action that “raised the memory of men to the level of the celebration of heroes and of gods.”66 Plutarch claims that the sculptor was thrown into prison, where he died, and meanwhile Meno, who had denounced him, was honored by the city.

However, there is no evidence to confirm the veracity of such an episode, which is related in this form only in the works of later authors.67 Besides, Plutarch makes a factual error in his account: Phidias did not die in prison for, soon after 438, he went off to Elis to sculpt a gigantic statue of Zeus at Olympia.68 From there, it is but a step to consign the entire anecdote to the gallery of Plutarchian fantasies. However, it is a step that we should forbear to take. Not only are the sculptor’s misfortunes mentioned by several fifth-century and fourth-century sources,69 but Plutarch does appear to be speaking from some experience. It is possible that during his stay in Athens, he had himself spotted the portraits sculpted on the goddess’s shield.70 Moreover, it seems that this was not the only misdemeanor of which the sculptor was accused: it was said that he had diverted for his own use some of the gold and ivory allotted for the construction of the statue of Athena Parthenos.71

Even if we accept that those accusations have some historical basis, it was certainly not impiety that fueled the Athenians’ indignation. The statue of Athena was provided with no attested sacrifices, no altar, no priest, and it had no ritual role. Rather, it was a political monument erected to the glory of Athens. What Phidias was accused of was, first, of having ignored the ban on representations of individuals on public Athenian monuments—in effect, of manifest hubris, not impiety (asebeia)—and, second, of having embezzled public funds.

The legal attacks against Aspasia, Pericles’ partner, are even more doubtful. According to Plutarch, the sole source to mention this affair, this Milesian woman was dragged before the courts on charges of impiety, prompting Pericles to abandon his usual reserve and to move the jurors’ hearts with his tears. Far from being historically attested, the whole story is probably the fruit of a late reconstruction that misconstrues the accusations made on the comic stage as an actual lawsuit against impiety.72

Are we on any firmer ground with the lawsuit brought against Pericles’ teacher, Anaxagoras? That is far from certain. He had been living in Athens for many years and is said to have been condemned for impiety at a date that is uncertain—possibly 432—and this prompted him to flee to Lampsacus, his home city, in northern Asia Minor, where he is said to have lived until his death.73 However, the whole affair remains very unclear. The Hellenistic sources, recorded by Diogenes Laertius (2.12), in any case produce two different versions of the matter. In one, it is the demagogue Cleon who prosecuted him for impiety; in the other, it is Thucydides, Pericles’ opponent, ostracized in 443, who accuses him of collaboration with the Persians.

Nor are these the only gray areas surrounding this supposed trial. On what legal basis could Anaxagoras have been found guilty? According to Plutarch, a certain Diopeithes proposed “a bill providing for the public impeachment of such as did not believe in gods [ta theia] or who taught doctrines regarding the heavens.”74 The suggestion, then, is that Diopeithes, an influential seer, was one of the zealous figures who clung to traditional piety and was shocked by Anaxagoras’s studies on the heavenly bodies and phenomena. For did not Pericles’ friend believe that the sun was an incandescent mass—not a deity—and did he not refuse to believe that eclipses were divine portents75?

Yet Plutarch is the only one to mention this strange decree, the authenticity of which is such a bone of contention for historians.76 Without entering into this debate that is so full of pitfalls, we can perhaps try to rephrase the question. To be sure, attacks on “naturalists” (phusikoi) did make a comeback in the 430s,77 for as the Spartan threat became more pressing, the Athenians were clearly keen to make sure that the gods were on their side. But does this imply that these critics resorted to a legal solution? There is no evidence to suggest that it does. What is certain, however, is that the comic poets were busy attacking not only the sophists and “nebulous chatterboxes” (meteōroleskhai), but any individuals who in some way drew attention to themselves in the city. In this respect, the seer Diopeithes was not spared any more than Anaxagoras was; the comic poets portrayed him as an oracular expert of doubtful repute, or even as a dangerous visionary.78 Perhaps, after all, that is the main lesson to be learned here: in the 430s, all forms of individual distinction became suspect.

Thus, none of the trials for impiety involving those close to Pericles is attested with certainty. So it is hard to detect any symptoms of a democracy given to persecution let alone terrorism and bent on punishing the slightest religious deviation. If authoritarianism did become stricter, it probably did so after Pericles’ death. The plague that carried off the stratēgos along with so many of his fellow-citizens did have a profound effect on the Athenians and their beliefs. According to Thucydides, the epidemic even drove men into nihilism and despair, as all their invocations to the gods remained unanswered: “The sanctuaries too, in which they had quartered themselves, were full of the corpses of those who had died in them; for the calamity which weighed upon them was so overpowering that men, not knowing what was to become of them, became careless of all law, sacred as well as profane. And the customs which they had hitherto observed regarding burial were all thrown into confusion, and they buried their dead, each one as he could.”79 Relations between men and the gods were lastingly undermined, as is testified by the mutilation of the Hermai and the profanation of the Mysteries of Eleusis, in 416/5. Readers of Thucydides will not be surprised to learn that the death of the stratēgos constituted a definite break; according to the historian, with the disappearance of the stratēgos, the life of the whole community underwent a change for the worse.