FIGURE 10. Pericles, detail from the fresco Strength and Temperance (ca. 1497), by Perugino. Perugia, Collegio del Cambio. Image courtesy of the Collegio del Cambio. Photo by Sandro Bellu.

Pericles in Disgrace: A Long Spell in Purgatory (15th to 18th Centuries)

The Oeuvres Complètes (Complete Works) of Voltaire, published in 1771, contain an intriguing conversation between Pericles, a Russian, and an eighteenth-century Greek.1 After such a long time in the Underworld, the stratēgos is keen to find out what modern men think of him. Addressing his compatriot, he naively asks, “But tell me, is not my memory still venerated in Athens, the town where I introduced magnificence and good taste?” To his great disappointment, his Greek companion has never heard either of him or even of Athens: “So you are as little acquainted with the famous and superb town of Athens as with the names of Themistocles and Pericles? You must have lived in some underground place, in an unknown part of Greece.” The Russian, who is less ignorant than his companion, intervenes to explain to the stratēgos how much the world has changed since his death: the Greeks, now subjects of the Ottomans, no longer know even the name of Athens. The opulent city has been replaced by “a wretched, squalid little town called Setines.” Contemplating the ravages of time with horror, the disillusioned stratēgos concludes, “I hoped to have rendered my name immortal, yet I see that it is already forgotten in my own land.”

This conversation from beyond the tomb strikingly condenses Pericles’ uneven trajectory in the Western world. Having suffered a long eclipse up until the eighteenth century (this chapter), the stratēgos progressively made a comeback. Even as he confirmed the fact that Pericles had been forgotten, Voltaire contributed toward his rehabilitation, and helped to forge the expression “the age of Pericles” (chapter 12).

A disgraced, even forgotten Pericles: the very idea will come as a surprise to readers accustomed to identify Athens with the prestigious figure of the stratēgos. One of the primary virtues of a historiographical inquiry is certainly its ability to dispel automatic assumptions and show that traditions do themselves have a history. No, Pericles was not always an admired icon. In the accounts of Athens from Antiquity right down to the eighteenth century, the stratēgos, ignored and sometimes discredited, became no more than a marginal figure.

How can one understand that journey across a desert without memories? By way of explanation, a number of factors may be considered. In the first place, there is the crushing influence on Western culture of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives: the success of this work played a major role in the relative marginalization of the stratēgos. Second, a particular kind of relationship to the past: Pericles was the victim of a kind of history that was designed as “a lesson for life” and that above all looked to Antiquity to provide moral and aesthetic models. The moderns found Pericles too slippery a character and preferred more straightforward types. Moreover, last but not least, Pericles was a victim of the anti-democratic prejudice that pervaded the monarchical Europe of the modern period. In such a context, this Athenian leader certainly did not constitute an attractive model for those in power or for their cultural representatives.

So, after receiving an early, rather timid burst of acclaim in the Renaissance, Pericles was totally ignored by the Moderns. If his figure ever was evoked, it was as a foil—now as an embodiment of democratic instability (Machiavelli and Jean Bodin), now as a model of misleading eloquence (Montaigne). And in the great quarrel between the Ancients and the Moderns that gathered momentum at the end of the seventeenth century, the stratēgos remained for the most part sidelined, being considered unworthy of comparison to Louis XIV. Tellingly enough, his rare appearances were limited to “dialogues of the dead”—as if Pericles could be imagined only in the Underworld, relegated to the kingdom of ghosts and oblivion.

The Enlightenment tempered this representation no more than marginally. Up until the end of the French Revolution, the stratēgos remained in the shadow of an Antiquity that was, to be sure, glorified, but that resolutely remained either Spartan or Roman. Amid the chorus of authors fascinated by Lycurgus or the Gracchi, a few dissenting voices nevertheless began to be heard, preparing the way for Pericles’ return to favor, in the nineteenth century, in totally different historiographical circumstances.

An inquiry such as the present one must clearly be based on no more than a drastic selection from the vast body of documentation that is available. So it will above all be a matter of sketching in the main guiding lines in a quite exceptional historiographical itinerary, sometimes proceeding in a series of “skips and jumps” (à sauts et à gambades), as Montaigne famously put it.

A False Start: An Isolated Eulogy from Leonardo Bruni

Yet it had all started well. In the fifteenth-century Italian republics—in particular, Florence—the humanists drew directly upon Greek works in which, among the Ancients, they found models that they could follow. They lived on an equal footing with Antiquity, using it as a means to break away from their own past (which was to become known as the Middle Ages). In this way, there emerged “a vision of a new world reconstructed from the words of Antiquity.”2 It was in this civic context that, in the West, the figure of Pericles was first mobilized.

Leonardo Bruni was one of the main vectors of this early acclimatization. He was born in Arezzo and was one of the brilliant generation of humanists grouped around Coluccio Salutati, whom he later succeeded as head of the chancellery of Florence. Immersed in Greek literature, as he was, he translated Aristotle, Plutarch, Demosthenes, and Plato and even produced a theoretical account of his experience of translation in a treatise titled De interpretatione recta. He used his intimate knowledge of the ancient sources in his Laudatio Florentinae urbis (In praise of the city of Florence), composed in 1404.3 At the turn of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the Florentines had just expelled the Visconti and adopted a republican form of government. Leonardo Bruni, the humanist, composed his Laudatio in order to legitimate this development and, naturally enough, it was the Athenian model to which he turned. He drew his inspiration from Thucydides’ Peloponnesian War and the Panathenaic Oration of Aelius Aristides—two texts that unambiguously exalted the institutions of Athens. In a clear imitation of the funeral speech, Bruni celebrated the geographical position of Florence, the crucial role that it had played against the foreign autocrats (the struggle against Milan was then raging), the superiority of the political institutions of Florence and its cultural supremacy.4 The humanist Leonardo Bruni was treading in the footsteps of the stratēgos.

Two decades later, in 1428, it was again to the Periclean model that Bruni turned when he composed the funeral oration for Nanni degli Strozzi.5 Taking advantage of this funeral in order to celebrate the city of Florence as a whole, in this speech Bruni extolled the liberty and equality of citizens ruled by an exemplary government that offered opportunities to every good man who deserved them. Even if Pericles was not explicitly mentioned, it was certainly his thinking and heritage that Leonardo Bruni used to promote his own political project.

Not long after this, the thinking of Pericles received more publicity. Around 1450, at the request of Pope Nicholas V, the great humanist Lorenzo Valla completed the first translation of Thucydides into Latin, thereby making the text more accessible. This Latin version was diffused in printed form. It was published in Treviso in 1483, and several more editions appeared in the course of the sixteenth century, incorporating the corrections made by Henri Estienne in 1564. The stage thus seemed set for the promotion of a positive view of Athens and its leader.

It all came to nothing, however. As a result of a number of structural factors, the memory of Pericles remained in limbo in the Western imagination. The first of those factors was the incredible success of Plutarch: traditions favorable to the stratēgos for a long time remained overshadowed by The Parallel Lives. The second was the prevalence of a particular attitude toward the past that was fueled by a perpetual quest for exemplary heroes; in the perspective of historia magistra vitae, the figure of Pericles was widely judged to be too lackluster or even repulsive.

The Reasons for a Long Eclipse

Lost in Translation: The Distorting Filter of Ancient Translations

In order to understand Pericles’ failure to engage with modern Europe, we need to recognize a somewhat shocking fact: even when the ancient texts were translated, they were not necessarily read. Out of all the formidable efforts that were devoted to publishing and translating in the Renaissance, only a limited number of works eventually rose to the surface and were selected as required reading in the education of a gentleman. The works of Plutarch in particular must be picked out, along with those of Livy on the Roman side. For whole centuries, The Parallel Lives, more or less on their own, provided all that members of the cultivated elite knew about Greece and its successive leaders.

The rediscovery of Plutarch dated from the early sixteenth century, when the humanist Guillaume Budé, “the prince of Hellenists,” who was close to Francis I of France, published a series of Apophtegmes (precepts), borrowed from Plutarch’s works. But his popularity really took off in 1559, when Jacques Amyot translated the Parallel Lives. Amyot was the Grand Chaplain of France and the Bishop of Auxerre and he gave the work a new title, Vies des hommes illustres Grecs et Romains comparées l’une avec l’autre (The lives of illustrious Greeks and Romans compared to one another), dedicating it to Henri II, who had appointed him tutor to the royal children. This was the launching point of Plutarch’s incredible popularity both in France and beyond—in fact, throughout the West. As early as 1572, Henri Estienne, in Geneva, produced the first complete edition of the work. It was divided into two great tomes—on the one hand the Vies Parallèles and on the other the Oeuvres morales (the Moralia), taking over a division that dated back to the work of the Byzantine monk, Maximus Planudes.

The impact of Amyot’s translation was long-lasting. At the end of the sixteenth century, Montaigne was writing, “We ignorant fellows had been lost had not this book raised us out of the dirt; … ’tis our breviary.”6 Montaigne even went so far as to turn Plutarch into a close friend, almost a brother: “Plutarch is the man for me,”7 he exclaimed, to some extent setting him up as a rival to La Boétie! Far from being an isolated view, Montaigne’s admiration was shared across the board, from Machiavelli to Jean Bodin. It was thus through the prism of the Parallel Lives that the members of the elite groups of the modern age saw the figure of Pericles.8 But however much Plutarch admired Pericles’ great works, he denigrated the democrat and was only too happy to record the traditions that were the most hostile to the stratēgos.9

Should not a reading of Thucydides have somewhat redressed the balance? The Athenian historian had been translated into Latin very early on by Lorenzo Valla and subsequently into French by Claude de Seyssel (in a volume published posthumously, in 1527, under the aegis of King Francis I). However, up until the late eighteenth century The Peloponnesian War reached no more than a limited readership. In the first place, the translations of it left quite a lot to be desired. According to the scholar and publisher Henri Estienne, Valla and Seyssel had “distorted” the historian (Seyssel did not even read Greek).10 But above all, the work was out of step with the taste of the period. Occasionally, it was judged to be sublime and full of majesty, but the general opinion was that Thucydides’ style was austere and inelegant, and his dry, spare prose offended the aesthetics of classicism which, in contrast, praised to the skies the elegant expansiveness of Plutarch, which was even magnified by Amyot’s translation. Completed by a reading of Plato and of Aristotle (the Politics), the education of a man of the modern age paid no attention to any texts that might have corrected the detestable reputation of the stratēgos.

All this resulted in the creation of a filter that lastingly warped the reception of Antiquity in general and of Pericles in particular. Plutarch held first place and was followed by Plato and Aristotle. Clearly democracy and its leaders did not emerge flatteringly from the selective process applied to the ancient texts.

Pericles, a Man without Merit: Not an Exemplary Figure

Plutarch’s great popularity was accompanied by another factor that was equally negative for Pericles. This was a particular attitude to history that can be traced back to Cicero. Up until the eighteenth century, history was regarded primarily as a “teacher of life” (magistra vitae), as that Roman orator famously put it. It could be summed up as a collation of examples which, when picked out (ex-empla) elicited either imitation or, on the contrary, execration.11 All that men remembered from history were characters and images, great tableaux, and symbolic scenes that painters delighted in reproducing.12

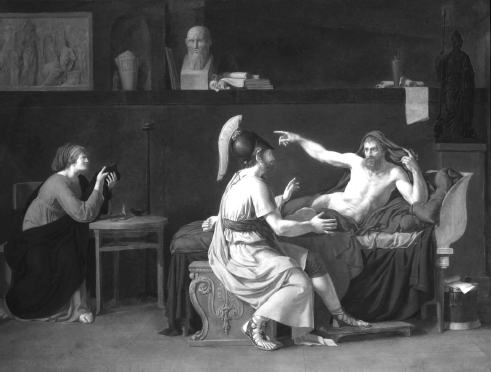

FIGURE 10. Pericles, detail from the fresco Strength and Temperance (ca. 1497), by Perugino. Perugia, Collegio del Cambio. Image courtesy of the Collegio del Cambio. Photo by Sandro Bellu.

As an exemplary figure, Pericles did not seem an attractive model. He was not among the colorful figures around whom analogies and comparisons crystallized. When the stratēgos was mentioned, it was seldom on his own account. Often enough he was cited in passing among the rest of the politicians who embodied Athenian democracy: Themistocles, Aristides, Cimon, and Alcibiades.13 Neither a glorious conqueror such as Alexander the Great, nor a brave warrior such as Themistocles or his own rival Cimon; neither a wise lawgiver such as the consensual Solon nor a heroic martyr such as Socrates; not even as scandalous a stratēgos as his pupil Alcibiades—nothing about Pericles really caught the eyes and attention of members of the modern elite. Even his death left them indifferent: how boring, to die in one’s bed, consumed by disease! That is why there were so few pictorial representations of the stratēgos. Apart from one timid appearance in Perugia, in the strange guise of a bearded old man painted by Perugino (ca. 1497; figure 10) in the reception hall of a guild of money-changers,14 Pericles was ignored by both the Renaissance painters and those of modern times. In Raphael’s famous painting, The School of Athens (ca. 1509–1510), he is conspicuous by his absence despite the fact that he might logically have found a place there since it was, after all, he who turned Athens into “a living lesson.”

Shunned by painters and poets, Pericles remained in the shadow of other ancients who were deemed more presentable. The glorification of those few figures affected the image of Pericles himself disastrously. What the readers of Plutarch remembered was that the great men of Athens were all dragged through the mud: Themistocles, Aristides, and Cimon had all been ostracized; Socrates and Phocion were executed. It was hard to cherish their memory without condemning the form of governance that had set them aside or put them to death. The role of the anti-hero was therefore assigned to democracy and to Pericles himself, who was more or less strongly associated with it.

Those who did deign to take an interest in him dwelt on his disturbing aspects; only the most equivocal events in his life were selected, all with a view to criticizing him. Presented as he was, now as a war-monger, now as a corrupter of the people, he seemed the very embodiment of both democratic instability and deceptive eloquence.

Pericles, or the Democratic Anti-model

Even in the small Italian city-states of the Renaissance, Pericles never became a positive model; in this respect, Leonardo Bruni was far more of an exception than a general rule. Moreover, even he did not explicitly praise the stratēgos, but drew his inspiration solely from his funeral speech. The fact was that the political thinkers of the Italian Renaissance displayed a marked preference for the Roman Republic and the government of Sparta. In view of the constant revolutions of Athenian democracy, they loudly and strongly proclaimed their admiration for the stability of the Spartan regime and its well-balanced constitution. In the writings of Machiavelli (1469–1527), the armed camp on the banks of the Eurotas River was presented as an ideal to imitate, while the city of Athena was an example to be avoided.15

Pericles in Italy: A Bad Counselor or a Virtuous Citizen?

In his Discourses on the First Ten Books of Titus Livius, published between 1512 and 1517, the great political thinker Machiavelli set up the following striking parallel:

Amongst those justly celebrated for having established such a constitution, Lycurgus beyond doubt merits the highest praise. He organized the government of Sparta in such manner that, in giving to the king, the nobles and the people each their portion of authority and duties, he created a government which maintained itself for over eight hundred years in the most perfect tranquillity, and reflected infinite glory upon this legislator. On the other hand, the constitution given by Solon to the Athenians, by which he established only a popular government, was of such short duration that before his death he saw the tyranny of Pisistratus arise (1.2).16

According to Machiavelli, Solon was the sole inventor of democracy: so exit Pericles, along with all the other Athenian leaders. But, as it happened, that mattered little since, according to the Florentine writer, the Athenian regime was vitiated right from top to bottom.

When Machiavelli cites Pericles by name (the only time in his entire work), it is, moreover, to mock his views. He criticizes his military ideas, declaring them to be totally misconceived: “History proves in a thousand cases what I maintain, notwithstanding that Pericles counselled the Athenians to make war with the entire Peloponnesus, demonstrating to them that by perseverance and the power of money they would be successful. And although it is true that the Athenians obtained some successes in that war, yet they succumbed in the end; and good counsels and the good soldiers of Sparta prevailed over the perseverance and money of the Athenians.”17 He claims that the stratēgos proved himself incapable of correctly evaluating the balance of power on the eve of the Peloponnesian War. Overconfident in the financial resources of his country, he forced it into a conflict that it was bound to lose.

In the writings of Guicciardini (1485–1540), a friend of Machiavelli’s and a Florentine politician, blame gave way to praise. Pericles makes no more than a discreet appearance in his writings, but he does so to his advantage. The author draws attention to the incorruptibility of the stratēgos, thereby justifying his view that there was “no citizen more worthy and glorious” than Pericles, who governed Athens for thirty years “thanks solely to his authority and his reputation for virtue.”18 Did this amount to an exception to the doubtful reputation of the stratēgos? Not altogether. His praise was somewhat qualified: even if he gladly acknowledged Pericles’ virtue, Guicciardini criticized his demagogic views and maintained that to come to power thanks to the Senate was preferable to depending on the people in order to do so.19

One generation later, Carlo Sigonio (1523–1584), a native of Modena, returned to a negative view of the stratēgos, in the very first monograph to be devoted to the city of Athens, the De Republica Atheniensium (1564).20 Having been a teacher in Venice, where its powerful fleet reminded him of Athens, Sigonio was very well informed about the ancient sources and stuffed his text with Greek, citing not only philosophers but also the Athenian historians and orators. However, this scholar remained extremely reserved on the subject of Pericles, whom he accused of having ruined Solon’s admirable constitution: “As for Aristides, who acquired great authority through these [Persian] wars and, after him, Pericles, a man adept at speaking and action, both amplified the constitution of this popular republic and granted to the plebs and the incompetence of the multitude all that Solon’s laws had denied them.”21 A few pages later, Sigonio made his criticisms more explicit: “Pericles made the people more insolent and arrogant by assigning to the plebs the financial means to set up courts and to construct theatres for their entertainment, thereby toppling the power of the Areopagus through the intermediary of Ephialtes.”22 Despite Sigonio’s admiration for the democratic city, which was very rare in his day, he remained captivated by Plato’s vision, which spared neither Pericles nor even Aristides.23

“The Ruination of the Republic”: The Disenchanted View of Jean Bodin

In France, at the end of the sixteenth century, Jean Bodin (1530–1596) seized upon Pericles, making him the execrated emblem of all republican regimes. This remarkable jurist endowed with an encyclopedic mind was writing in a France rent apart by the religious quarrels between the Catholics and the Huguenots. Faced with the Religious Wars, Bodin chose to exalt the royal State that alone was capable of bringing those internecine struggles to an end. It was he who set out the bases of the first real doctrine of sovereignty, having engaged in an in-depth historical inquiry in the course of which he investigated the political regimes of the past.

Bodin began his investigations with a book that was published in 1566, titled Methodus ad Facilem Historiarum Cognitionem (Method for the Easy Comprehension of History). In chapter 6, devoted to the constitution of republics, Bodin set out to “compare the empires of the Ancients with our own” in order, by establishing historical parallels, to discover the best possible form of government. The Athenian system was scrutinized in a demonstration in which Pericles played a key role by reason of his actions against the aristocratic Areopagus and his introduction of payment for public services: “At length Pericles changed a popular state into a turbulent ochlocracy by eliminating, or at least greatly diminishing, the power of the Areopagites, by which the safety and dignity of the state had been upheld. He transferred to the lowest plebs all judgments, counsel, and direction of the entire state by offering payments and gratuities as a bait for dominion.”24 No good could come from this action of the stratēgos, whom Bodin found guilty of having put an end to the “constitutional and just” regime that preceded the evil government by the plebs.

In his great work, The Six Books of the Commonwealth (1576), which was published in French a few years later, Bodin continued in the same political vein, adding a number of new touches to his picture. As in the Method, Pericles was judged to be responsible for the decline of Athens: “As Pericles, to gain the favor of the common sort, had taken away the authority from the Areopagites and translated the fame to the people … shortly after, the state of that Commonwealth, sore shaken both with foreign and domestic wars, began forthwith to decline and decay.”25 Worse still, the stratēgos was said to have dragged his city into warfare so as to avoid having to present his accounts: “Pericles …, rather than he would hazard the account that [the people] demanded of him for the treasure of Athens, which he had managed, and so generally of his actions, raised the Peloponnesian war, which never after took end until it had ruined divers Commonwealths, and wholly changed the state of all the cities of Greece.”26

This was certainly a dark picture, but Bodin did introduce one shaft of light into it. He suggested that Pericles did nevertheless manifest a degree of genius in his management of the people:

So the wise Pericles, to draw the people of Athens into reason, fed them with feasts, with plays, with comedies, with songs and dances; and in time of dearth caused some distribution of corn or money to be made amongst them; and having by these means tamed this beast with many heads, one while by the eyes, another while by the ears, and sometimes by the belly, he then caused wholesome edicts and laws to be published, declaring into them the grave and wise reasons thereof: which the people in mutiny, or in hunger, would never have hearkened unto.27

Bodin, adapting a passage from Plutarch’s Life of Pericles (11.4), the tone of which was extremely critical, nevertheless turned it into praise for the stratēgos. What can be the explanation for this paradoxical praise? The fact is that, between The Method for the Easy Comprehension of History (1566) and The Six Books of the Commonwealth (1576), the massacre of Saint Bartholomew had taken place (1572). Horrified by the spectacle of those popular “emotions,” Bodin was forced to admire the way that Pericles had managed to tame the people, “this beast with many heads” that was always ready to launch into unbridled violence.

But despite that late correction of a detail, the picture as a whole was still a sinister one: as described by Bodin, the stratēgos remained the symbol of an eminently detestable regime in which the monarchist jurist could find nothing good.

Pericles the Flatterer: Montaigne’s Critique

Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) was equally critical of Pericles but adopted a different angle of attack in order to denigrate the stratēgos—not that he was systematically hostile to Athens, for, influenced by Plutarch, he was quite prepared to admire Aristides and Phocion. However, he regarded Pericles as the archetype of rhetoricians and grammarians who were adept at “the science of the gift of the gab.” In the Essays, the first two books of which were published in Bordeaux in 1580, Pericles thus found himself accused of having used language to corrupt “the very essence of things”:

A rhetorician of times past said that to make little things appear great was his profession. … They would in Sparta have sent such a fellow to be whipped for making profession of a tricky and deceitful act; and I fancy that Archidamus, who was king of that country, was a little surprised at the answer of Thucydides, the son of Melesias, when inquiring of him which was the better wrestler, Pericles or he, he replied that it was hard to affirm; for when I have thrown him, said he, he always persuades the spectators that he had no fall and carries away the prize.28

Now Pericles was reduced to one single outstanding characteristic: he was expert in “the art of flattery and deception” and was represented as a sophist who misled his listeners by the sole power of his speech.

Montaigne’s critique conveyed a political point: according to him, rhetoric was “an engine invented to manage and govern a disorderly and tumultuous rabble,” and it was primarily a feature of “discomposed States,” “such as that of Athens.”29 Montaigne contrasted this anti-model to Sparta, the virtue of which lay precisely in a sparing use of speech: “the republics that have maintained themselves in a regular and well-modelled government, such as those of Lacedaemon and Crete, had orators in no very great esteem.”30 The laconic Spartans, who refused to indulge themselves with words, emerged all the greater from being compared to the stratēgos.

Pericles the flatterer: By assimilating the stratēgos to a fast talker, Montaigne set up a stereotype that was lastingly to haunt the imagination of members of the European elite, when, that is, they deigned even to consider the case of the stratēgos. For he now interested hardly anyone; at the threshold of the seventeenth century, the name of Pericles evoked above all the hero of a tragicomedy by Shakespeare. In this play, written around 1608, William Shakespeare set on stage the ups and downs of Pericles, prince of Tyre, who, like a latter-day Odysseus, traveled around the Mediterranean, meeting with extraordinary adventures, before returning home to reign over his country. The fact that the name “Pericles” could be given to an Eastern prince in this way testifies to the oblivion into which Pericles had sunk in the imaginary representations of the western world.

PERICLES, FORGOTTEN IN THE GREAT CLASSICAL AGE

Pericles Nowhere to Be Found: The Quarrel between the Ancients and the Moderns

At the turn of the seventeenth century, relations with the Ancients imperceptibly changed. With the advent of the Classical age—the age of princes, the national interest, and absolutism—the great figures of Antiquity were considered no longer as political models but rather as a collection of admirable modes of behavior and incarnations of moral virtues such as heroism, self-control, and a sense of honor and obedience.31

In this new situation, Pericles was seldom mentioned. Even the most erudite of authors tended to pass over his actions in silence, one of them being Jacob Spon, the great Protestant scholar who produced one of the very first collections of Latin inscriptions, the Miscellanea eruditae antiquitatis. In his Voyage d’Italie, de Dalmatie, de Grèce et du Levant fait aux années 1675 & 1676, which he wrote in collaboration with George Wheler, the stratēgos appeared nowhere except where the Parthenon was described as “a temple built by Pericles.”32

Among the Greeks, it was now Alexander the Great who was the center of attention. In France, the great Condé and Turenne were both likened to the Macedonian king as, after the siege of La Rochelle (1627–1628), was Richelieu, who was called “the French Alexander.” But of course it was chiefly the French monarch who was compared to Alexander. Louis XIV even assigned him a key role in royal propaganda: in the 1660s, the painter Charles Le Brun, at the king’s request, produced a great cycle of paintings depicting the achievements of Alexander; and in 1665, the tragedian Racine played explicitly on the analogy when he dedicated his play, Alexandre le Grand, to the king.33

In the early 1670s, the wind of history suddenly veered. Parallels with the ancients were abandoned. Now Louis XIV would advance alone in all his majesty, refusing to be compared to anyone else, even Alexander. The court rapidly fell into line. In 1674, Jean Desmarets de Saint-Sorlin, in his Triomphe de Louis et de son siècle thus berated the Ancients, accusing them of not having displayed “the love and respect that they owed their country.” In 1687, the quarrel between the Ancients and the Moderns took off. In a session at the Académie Française, Charles Perrault had his poem Le Siècle de Louis le Grand read out, to celebrate the recovery of the convalescent king. Its opening lines became famous:

La belle antiquité fut toujours vénérable

Mais je ne crus jamais qu’elle fût adorable.

Je vois les anciens, sans plier les genoux;

Ils sont grands, il est vrai, mais hommes comme nous

Et l’on peut comparer, sans craindre d’être injuste,

Le siècle de Louis au beau siècle d’Auguste.

(Fine antiquity was always venerable

But I never considered it adorable

At the sight of the ancients I do not bend the knee;

True, they are great but just men as are we;

And we may, with no fear of seeming unjust, Compare our age of Louis to that fine age of Augustus.)

In 1688, one year later, Perrault’s first dialogue on the Parallel between the Ancients and the Moderns, which underpinned and justified that poem, was published. It was followed by three further dialogues that appeared, respectively, in 1690, 1692, and 1697. Perrault did not attack Antiquity as such, but denied it his allegiance. Convinced that there is “nothing that is not improved by time,” the courtier-poet proclaimed the Moderns’ superiority over the Ancients. The present became the supreme yardstick that had to be considered as both a reference and the pattern to be followed.34 Meanwhile Boileau and La Bruyère, as partisans of the Ancients, on the contrary continued to regard Antiquity as an essential resource and, above all, a model that encouraged Moderns not to be carried away by an excess of self-satisfaction.

It was, of course, not the first time that Greek Antiquity had come under attack.35 As early as the Renaissance, the Greek language had been accused by a Catholic and Latin Europe of being the vehicle of ancient paganism, the Byzantine schism, and, later, Lutheran heresy. Despite the eventual success of the humanists, in the Europe of the Counter-Reformation, Greek literature remained lastingly suspect. Criticism of Greek literature now again became fashionable, thanks to Charles Perrault, who lambasted Homer and the corrupt religion of the Greeks.36 However, what was new was that now the prestige of Rome too was being, if not questioned, at least challenged. Sometimes the discredit of the Ancients reached a ridiculous level: Father Hardouin, prompted by a radical skepticism, even suggested that most of the Greek and Roman texts were in truth the work of fourteenth-century Dominican forgers!37

In this long drawn-out quarrel, the figure of Pericles played an extremely marginal role. He was seldom targeted by the moderns but nor was he enrolled by the defenders of the Ancients. Attracting so little interest, the stratēgos remained in the shadows, or even in Hades, and he made no more than a few fleeting appearances in the Quarrel.

In his great poem on Le Siècle de Louis le Grand, Charles Perrault never even mentioned Pericles, whereas he did refer, each in turn, to Plato, Aristotle, Demosthenes, and Menander. More significantly still, in his works as a whole, which accumulate so many references to the Ancients, allusions to the stratēgos can be counted on the fingers of one hand, and, even then, he is never cited on his own. In the Parallèle entre les Anciens et les Modernes, Pericles is merely one of the many ancient orators that, according to Perrault, pedants use quite irrelevantly: “They make an appalling din and with the grandiose words of Demosthenes, Cicero, Isocrates and Pericles that are constantly on their lips and that they emit with an altogether unnatural pronunciation, they astonish even the cleverest people and sweep along the common folk to whom these kinds of ghosts always seem grander than the real scholars who possess both minds and life.”38 In this way, Perrault belittled Pericles even without targeting him in particular, along with other representatives of a hoary old rhetorical culture.

The same goes for a letter addressed to a friend, in which Perrault derides the pompous eloquence of the Ancients:

As for Prose, you complain that one no longer dares to mention the names of Cambyses or Epaminondas in a speech. Such a great shame! … Have not those two names, along with those of Themistocles, Alcibiades, and Pericles, sufficiently tired the ears of all our Princes, in the speeches that are addressed to them? Do you expect the King, when the good of the State obliges him to travel here and there in his kingdom, to suffer the same persecution in every town with a mayor or dignitary who fancies himself as an eloquent speaker? Just imagine how exhausting it must be to be assailed twice a day by Themistocles or Epaminondas or even both of them at once!39

For Perrault, Pericles was no more than a pompous name among others, a symbol worn threadbare by provincial dignitaries lacking all distinction.40

Charles Perrault’s niece, Marie-Jeanne l’Héritier de Villandon made the very same point in her Enchantements de l’éloquence (The Enchantments of Eloquence), a collection of stories dating from 1695. One of these, titled “The Fairies,” ends with a parallel that disparages the stratēgos:

I do not know, Madame, what you think of this story, but it seems to me no more incredible than many of the tales that ancient Greece brings us; and when describing the effects of Blanche’s eloquence, I am as happy to say that pearls and rubies fall from her lips as I am to say that flashes of lightning came from the mouth of Pericles. Story for story, it seems to me that those of ancient Gaul are worth roughly the same as those from Greek antiquity; and the fairies have just as much right to produce wonders as do the gods of fable.

As a worthy heir to Perrault, Madame de Villandon wished to tell French stories, unburdened by weighty ancient references, especially those involving heroes of Greece from a bygone age, such as Pericles.

Nor were the Ancients’ defenders any keener on the figure of Pericles than the supporters of the Moderns were. And on the rare occasions when they used it, they drowned him in a list in which the stratēgos was hard put to make his mark. That was the case, for example, in the speech that Jean Racine delivered to the Académie Française in honor of Pierre Corneille, who died in 1648: “This was a figure truly born for the glory of his country, comparable (I will not say to all Rome’s excellent tragedians, since Rome admits that she was not very successful in that genre) but at least to the likes of Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides of whom Athens was as proud as she was of figures such as Themistocles, Pericles and Alcibiades, who lived in that same period.” Although the citation is undeniably appreciative, Pericles is reduced to the role of a mere foil for the Athenian tragic poets and, on the rebound, for the deceased Corneille.

When the stratēgos does appear in the seventeenth century, it is in a very particular genre, that of Dialogues of the Dead, which flourished in the reign of Louis XIV. In these, we find a pensive or even saddened Pericles, meditating on his descent to the Underworld.

A Pericles in Torment: The Stratēgos in Dialogues of the Dead

Dialogues of the Dead were all the rage at the end of the seventeenth century. This narrative technique, inspired by Lucian of Samosata (A.D. 120–180) accommodated all kinds of encounters. Here, Ancients and Moderns could meet freely and talk together after their deaths. For those who adopted this format, imagining improbable postmortem encounters from which the heroes did not always emerge enhanced, it seemed an amusing way to undermine great figures of the past.

In 1685, Fontenelle (1657–1757), a well-established partisan of the Moderns, produced a series of Dialogues of the Dead in which, in the Elysian Fields of the Greek Underworld, figures from Antiquity met with more contemporary characters. For him, this was an ideal opportunity to confront ancient thought with modern ideas, rejecting the primacy so often accorded to the Ancients. In his third dialogue, Socrates and Montaigne are chatting in the Underworld and, ironically enough, it is the Greek philosopher who takes it upon himself to deflate the prestige of the great figures from Antiquity:

SOCRATES.—Take care you are not deceived; Antiquity is an Object of a peculiar kind; its distance magnifies it. Had you but known Aristides, Phocion, Pericles and myself (since you are pleased to place me among their number), you would certainly have found some to match us in your own Age. That which commonly possesses people so in favour of Antiquity is their being out of humour with their own times, and Antiquity takes advantage of their spleen. They cry up the Ancients in spite to their contemporaries. Thus, when we lived, we esteemed our ancestors more than they deserved; and, in requital, our posterity esteem us at present more than we deserve.41

However, the appearance of Pericles here is still very discreet. Although mentioned in passing, the stratēgos is not characterized at all, as if Fontenelle did not consider him worthy of being a major character in a dialogue of the dead. Five years later, in his Digression sur les Anciens et les Modernes, he did not even mention the stratēgos, but cited only Homer, Plato, and Demosthenes in support of his thesis.

It was not until the Dialogues of the Dead composed by Fénelon (1651–1715) that Pericles at last landed a leading role, even if this did not necessarily redound to his advantage. Fénelon, a latecomer to the Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, presented himself as a conciliator, refusing to take sides. He was appointed tutor to Louis XIV’s grandson (between 1689 and 1695), and during this period wrote his Dialogues des morts, which were, however, not published until after his disgrace.42 The purpose of this work, designed for the edification of the dauphin, was educational. The dauphin was presented with models either to emulate or, on the contrary, to shun. Freely inspired by an anecdote told by Plutarch,43 the eighteenth dialogue was entirely unambiguous in this respect. In it, Pericles held the role of a counterexample.

The stratēgos, here greeting his pupil Alcibiades upon the latter’s arrival in the Underworld, was depicted as a tormented man, bewailing his fate and his lost authority:

PERICLES.—You know very well, that could eloquence prevail (and this I may say without vanity) I should come off as well as any other: but talking to them is in vain. Those flatteries by which the Athenians were won, those subtle turns in discourse, those insinuating ways by which men are taken, by falling in with their humours and passions, are of no service here. Their ears are stopped, and their hearts of brass cannot be moved. Though I died in the unhappy Peloponnesian war, yet am I punished for it here below. They ought to have forgiven me such fault, in the commission of which I lost my life; and which I was led into by your persuasions.

ALCIBIADES.—True, I advised you to undertake this war, rather than be obliged to make up your accounts. … Can your judges here below be angry at such maxims?

PERICLES.—Yes, so very angry, that though in that cursed war I lost the confidence of the people, and died of the plague, yet have I suffered terrible punishments here, for having unseasonably disturbed the public quiet. By this you may judge, cousin, how well you are like to come off.44

Confessing himself guilty of unleashing the Peloponnesian War, Pericles thus ended up suffering in the Underworld, where his formidable rhetorical skills were of no avail to him and could not mollify his judges who remained deaf to all his fine words and judged only his actions.45 For once, he attracted attention at centerstage, but he was depicted as an unscrupulous politician, now punished for his reprehensible actions.

However, despite these timid appearances in the Underworld, for most of the time Pericles remained confined to the margins of Western imaginary representations.

A Flash of Lightning in the Darkness: Hobbes’s Pericles

The work of Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) presents an exception in this gloomy panorama. Before becoming the now famous great philosopher, the author of Leviathan made his name with a translation of The History of the Peloponnesian War, which was published in 1629 (figure 11). To translate this work by Thucydides was by no means an obvious thing to do, for the Greek historian aroused scant interest in Tudor England except among a few scholars, such as Francis Bacon. To be sure, the work had already been translated almost a century earlier, in 1550, by Thomas Nicoll. However, that translation was not at all trustworthy insofar as it was based on the faulty French translation by Seyssel, which was itself derived from the “faithless beauty” in Latin by Lorenzo Valla. “No doubt Hobbes was right in saying that Thucydides had been traduced rather than translated into English.”46

Hobbes, who came from a modest family, with neither fortune nor reputation, undertook this vast enterprise while employed as a tutor in the noble Cavendish family. In the humanist manner, he regarded history as a determining element in the education of the young aristocrat in his charge. Pericles, depicted as an honest man, motivated solely by virtue, emerged enhanced from a reading of this work. In contrast to Hobbes’s pessimistic diagnosis of human nature, Pericles did not appear as a bloodthirsty wolf but rather as an attentive shepherd, struggling against the impulses of his flock, with no concern for his own egoistic interests.47

Hobbes explained the mainsprings for his admiration for the stratēgos in a short text devoted to the life of Thucydides that accompanied the translation.48 According to him, the Athenian historian harbored no sympathy for democracy: “From his opinion touching the government of the state, it is manifest that he least of all liked the democracy.”49 According to Hobbes, Thucydides instead favored not only oligarchy but, even more, monarchy. In his view, Athens reached the peak of its glory when ruled by sovereigns, first Pisistratus, then Pericles: “He praiseth the government of Athens when it was mixed of the few and the many, but more he commendeth it both when Peisistratus reigned (saving that it was a usurped power) and when, in the beginning of this war, it was democratical in name, but in effect monarchical under Pericles. So that it seemeth that as he was of regal descent, so he best approved of the regal government.”50 Hobbes’s approval of the stratēgos was thus based on a particular reading of Thucydides, whom he considered to be a fervent supporter of monarchy. On those grounds, he interpreted the famous formula of book II—“It was in name a state democratical; but in fact a government of the principal man”—as a barely veiled monarchist slogan.51

FIGURE 11. Detail of the title page to Thomas Hobbes’s translation of Thucydides’ Eight Bookes of the Peloponnesian Warre, 1634 [first edition 1629]. Engraving by Thomas Cecill, 1634. Photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

In his old age, in 1672, Thomas Hobbes’s opinion remained unchanged. Looking back over his career, he claimed in his autobiography written in Latin verse that Thucydides pleased him “more than all the other” historians, because “he has shown that democracy was bad and [that] a single man was far wiser than the crowd.”52 The rehabilitation of Pericles thus took place to the detriment of democracy, which was depicted as a pure simulacrum that concealed an acceptance of royalty or, at any rate, of personal power: “This was to be not only the position of Thucydides, but a great political discovery that was to make it possible, throughout history, for conservatives in all countries and all ages, to admire the greatness of Athens without approving of the popular regime.”53

By inventing this elegant solution (praising Pericles and at the same time stigmatizing the popular regime), Hobbes established the bases for the rehabilitation of the stratēgos in a Europe dominated by monarchist culture and ideals. So, a priori, the period seemed ready for Pericles’ return to grace, given that, in the years that followed, the ancient models made a triumphant return. But, alas, the chance was yet again missed, and anti-Periclean clichés even enjoyed a rejuvenation.

PERICLES AS JUDGED BY THE ENLIGHTENMENT

After the Moderns’ victory over the Ancients in the last years of the seventeenth century, the century that followed was marked by a sudden “return to Antiquity.” Europe was seized by a veritable mania for the ancient world, which was sharpened by the discovery of the towns buried beneath the lava from Vesuvius: Herculaneum in 1738 and Pompeii ten years later: “for the first time, people penetrated, as if committing a burglary, right into Antiquity.”54 And this was not simply a return to the status quo ante. The eighteenth century helped to “repoliticize” the relationship to the Ancients and, in particular, to focus on Greece. However, this “repoliticization” process took place through the intermediary of the Sparta of Lycurgus, not the Athens of Pericles.

Pericles Eclipsed: Overshadowed by Lycurgus

After 1720, the return to Antiquity took place in a selective manner, drawing a dividing line within ancient history. Lycurgus’s Sparta and Republican Rome, both praised wholeheartedly, were set in opposition to the Athenian democracy, threatened by anarchy, and imperial Rome, “subjected to the bloodthirsty despotism of half-mad Caesars.”55 As a result of this great division, the Spartans found themselves credited with every virtue, leaving the Athenians very pallid by comparison.

A number of factors combine to explain the incredible success of Sparta in the Europe of the Enlightenment. First, the persistent popularity of the same texts (with the same lacunas) continued to produce the same effects. Thucydides remained the least appreciated of all the ancient historians, so much so that he was even considered—somewhat exaggeratedly—as “the major victim of the Enlightenment”56: The Peloponnesian War was treated to no French translation between the “faithless beauty” by Nicolas Perrot d’Ablancourt in 1662 and the version produced by Pierre Charles Lévesque in 1795. Plutarch, in contrast, continued to enjoy the same prestige among cultivated elite groups. Better still, it became easier to access his “Spartan works,” for in 1721 André Dacier offered a new translation of the Life of Lycurgus, in which the language was more accessible than that of Amyot’s 1559 translation.

In the Parallel Lives, Sparta also benefited from another advantage over Athens. The entire history of Sparta was covered by the Life of Lycurgus and, more marginally, that of Lysander, whereas the image of Athens was spread over eight different Lives, ranging from Solon to Demosthenes. Reduced to a single survey, the Spartan city was able to accommodate philosophical generalizations more easily than Athens, embroiled as it was in complex constitutional developments. The Spartan system, established all at once and fixed forever, offered the philosophers of the Enlightenment a fascinating model.

For the Athens of Pericles likewise to become “good to think with” required a quite different attitude to erudition in order to escape from so caricatural a representation. But the philosophes, on the contrary, developed a marked aversion to erudite scholars, accusing them of accumulating knowledge without the ability to discriminate between what was valuable and what was not. In the Discours préliminaire (preface) to the Encyclopédie, D’Alembert described an erudite scholar as “a kind of miser … who picks up the most worthless metals along with the most precious of them” and, in order to do so, needs nothing but a good memory, the faculty that is the first to be cultivated because it is the easiest to satisfy.”57 In France, the philosophes in no way sought to expand the available range of ancient sources, preferring to bask in the vision of a stylized Antiquity that was provided by Plutarch, with a little Plato and Aristotle mixed in.

Sparta held a final trump card that made its attraction almost irresistible to the philosophes of the Enlightenment: its austere mores. Lycurgus’s city fueled the critique of luxury that developed in reaction to the excesses of the Regency (1715–1723). Rousseau, among many others, referred constantly to the Spartan model in order to defend an ideal of frugality and to oppose the corruption of his day.58

The Greece of the eighteenth century was therefore primarily Spartan. Rousseau, Mably, Helvétius, Turpin, and the Encyclopédistes were all admirers of Sparta, ready to revile fifth-century Athens by contrast. To be sure, a number of discordant voices were raised and, in the Europe of the Enlightenment, Pericles’ fatherland was not solely denigrated by detractors; Rollin and Voltaire presented a definitely positive view of this member of the Alcmaeonid family, as we shall see in the next chapter. All the same, it was not necessarily the stratēgos who caught the attention of the few intellectuals sympathetic to the democratic city.

The case of Montesquieu is the most telling in this respect. In his Esprit des lois (1748), Athens, along with Rome, was presented as the model for “good democracies.”59 But we should be clear about the meaning of those words—in this case, what Montesquieu had in mind was not Pericles’ city but the voting qualifications established by Solon. This was the “democracy” that was close to his heart. In it, only the wealthy could become magistrates, the Council of the Areopagus supervised the regime’s stability, and commerce flourished without obstruction.60 In this entire work of his, there was no mention of Pericles either at this point or, indeed, later! For the author of L’Esprit des lois the stratēgos was the very embodiment of an excessive liberty that leads to decadence. In book VIII, chapter 4, Montesquieu considered that “the victory over the Persians at Salamis corrupted the republic of Athens” by engendering “the spirit of extreme equality, which leads to the despotism of one alone.”61 Even among the rare defenders of Athens, Pericles thus found himself eclipsed by more irenic figures such as the wise lawgiver Solon.62

Turgot proposed an equally ambivalent view. Before famously becoming Louis XVI’s great reformist minister, in about 1750 he had favored an on the whole positive view of Athens in his fragmentary universal historical sketch of the progress of science and the arts.63 All the same, that praise did not extend to the democratic regime as such: “Athens, governed by the decrees of the multitude, whose tumultuous excesses the orators calmed or encouraged as they saw fit, Athens where Pericles had taught its leaders to buy the State at the expense of the State itself and to dissipate its treasures so as not to have to render accounts; Athens, where the art of governing the people was the art of amusing it and feeding its ears, eyes and curiosity, always greedy for novelties, festivals, pleasures and constant spectacles: Athens owed to the very vices of its government that led to its defeat by the Spartans all the eloquence, taste, magnificence and the splendour in all the arts that made it the model of all nations.”64 This was, to put it mildly, an ambiguous paean of praise: even if, through its dazzling cultural achievements Athens had risen to the rank of “the model of all nations,” it owed that success to a vitiated culture that ineluctably condemned it to decadence and destruction. This was how Turgot contributed to the famous “quarrel about luxury” that led many other philosophes of the Enlightenment to mock the splendors of Periclean Athens in the name of the sacrosanct frugality of Sparta.65

Pericles under Attack: The Critique of the Sparta-Loving Philosophes

Rousseau and Mably: Pericles and the Corrupting Effects of Luxury

Jean-Jacques Rousseau admired Sparta so much that, in his Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts, he described the city of Lycurgus as “a Republic of demi-gods rather than of men.”66 In the view of the philosophe of Geneva, the city of Sparta had managed to combine austere mores with well-balanced institutions. It had seized a fortunate initiative and had “expelled the Arts and Artists, the Sciences and Scientists from [its] walls,” making itself “equally famed for its happy ignorance and for the wisdom of its Laws.”67 Athens was seen as an absolute foil to this model of austerity and sobriety. Rousseau, influenced by Montaigne’s Essays, could see Athens only as a land of “vices” and “fine arts.” This philosophe did not even deign to consider it a true democracy: “Athens was, in fact, not a democracy, but a most tyrannical aristocracy governed by learned men and orators.”68

In this dark picture, Pericles occupied a special position, as an orator in love with the fine arts rather than with virtue. “Pericles had great talents, much eloquence, grandeur and taste; he embellished Athens with excellent sculptures, lavish buildings and masterpieces in all the arts. And God knows how much he has been extolled as a result by the writing crowd! Yet it still remains to be seen whether Pericles was a good magistrate, for in the management of leading States, what matters is not to erect statues but to govern men well.”69 Echoing Plato’s attacks in the Gorgias and the Alcibiades, Rousseau deplored the stratēgos’s fundamental inability to improve his fellow-citizens in any way at all.

Rousseau’s reflections, in their turn, inspired the ferocious attack of Abbé Mably, who was Condillac’s brother. In his writings, this philosophe railed against the inequality of conditions and fortunes and yearned for a more egalitarian and virtuous society. Seen from this critical point of view, Pericles’ splendid Athens operated as an anti-model: it was nothing but a place of vice; the citizens of which clearly cared nothing for the common good. In his Observations sur l’histoire de la Grèce ou Des causes de la prospérité et des malheurs des Grecs (Observations on the history of Greece or On the causes of the prosperity and misfortunes of the Greeks), which appeared in 1766, this philosophe accused the arts and letters, in particular, of having encouraged debauchery and sensuality.70

In this process of accelerated decadence, Pericles was given a crucial role: “Elevated to the sublime views of Themistocles, [Athens] falls a dupe to Pericles, who leads her to the brink of her ruin.”71 Because he was extraordinarily talented, Xanthippus’s son was all the more effective as a corrupter: “A great captain, a great statesman and a still greater orator, Athens had never yet had a citizen who re-united in himself so many talents; but all these accomplishments employed to serve his ambition proved fatal to his country.”72 Mably then pinpointed his attack, accusing the stratēgos of having persuaded his fellow-citizens to replace their concern for republican virtue by a love of servile politeness: “[Pericles] foresaw with pleasure that Athens, in the midst of festivals, entertaining spectacles and pleasures, would abandon the customs suitable for a free State and that arts that were useless soon would become those most respected; the Athenians, distracted from their duties, would eventually aspire only to the puerile and dangerous glory of being the most polished and amiable people in Greece.”73 Mably thus added a Rousseauist touch to the generally accepted traditional picture derived from Plutarch, for, as Rousseau saw it, nothing could be worse than “this uniform and treacherous veil of politeness” that smothered republican liberty.

Mably even regarded Pericles as a veritable despot who sought the people’s support only the better to crush his own opponents: “This talented tyrant of Athens was too skilful to rely on the stability of their affections if he did not continually labour to fix them upon an immovable basis … He held the Great in subjection through the abasement wherein he had thrown the Areopagus and all the Magistracies so that no question was decided but conformably to his own will.”74 Having dispelled all competition, according to Mably, Pericles surrounded himself with insignificant and fawning courtiers: “Pericles had always banished merit from high places and employed only such persons in the Administration as were incapable of exciting his jealousy.”75

Pericles, “the scourge of his country and of Greece,” “the adroit tyrant of Athens,” a corrupt and corrupting stratēgos: there could be no appeal against such a verdict. In contrast to this terrible ogre, Abbé Mably sang the praises of an austere fourth-century Athenian, Phocion. It was a by no means fortuitous choice. Phocion, an ally of the Macedonians, possessed what Mably considered to be two inestimable qualities. In the first place, before being sentenced by the people to die by drinking hemlock, he had put a stop to democratic disorders by establishing a voting system based on tax qualifications. But above all, he had manifested Spartan virtues: “even in corrupt Athens, he retained the simple and frugal ways of ancient Sparta.”76 In this respect, Phocion constituted an exception in an Athens that had been corrupted by its orators. Mably represented him as heralding his own indictment of the stratēgos: “Pericles, whose superior genius might have made not only Athens but all Greece happy, did not stick at corrupting our morals, to cajole and gain the commonality; he made us the tyrants of our allies to make himself be thought necessary; and lastly kindled the fatal Peloponnesian War to shore up his tottering interest, and save himself from being called to an account for his maladministration.”77 Mably thus bestowed a whole new dimension upon the critique sketched in by Rousseau.

However, it was another Abbé (and another Jean-Jacques too) who, on the eve of the revolution, put the finishing touches to this dark portrait of the Pericles of the Enlightenment.

Abbé Barthélemy: Pericles, the Father of All Vices

In 1788, Abbé Jean-Jacques Barthélemy published his Voyage du jeune Anacharsis en Grèce. This work caused a great stir and attracted widespread attention throughout Europe.78 Instead of producing a conventional historical treatise, the author chose to approach Antiquity in a quite original manner. Readers discovered the world of Greek cities—its places, inhabitants, customs, and way of life—through the innocent eyes of a young Scythian traveling through Greece in the mid-fourth century. The work was also noticeably unusual in another respect. It was the result of thirty years of research and was based on first-hand knowledge that the author had acquired from work in the medallions section of the King’s Library in Paris.

But that intimate knowledge of Antiquity did Pericles no favors.79 While Abbé Barthélemy showered praise upon Solon, he poured bitter criticism upon the stratēgos, blaming him for being largely responsible for the decadence of Athens. In the long introduction designed to establish the background to his account, the abbé spelled out his reproaches in a separate section devoted to “the age of Pericles.”80

Admittedly, the portrait begins on a positive note, for Barthélemy ascribes a number of altogether exceptional virtues to the son of Xanthippus: he manifested “in his domestic life the simplicity and frugality of ancient times; in the administration of public affairs an unalterable disinterestedness and probity; in the command of armies a careful attention to leave nothing to chance and to risk his reputation rather than the safety of the state.”81 But all this was nothing but an “illusion,” as Barthélemy put it, for his personal qualities were not accompanied by any care for the public good.

On the contrary, Barthélemy alleges that Pericles acted as an unscrupulous demagogue. Predictably enough, the Abbé contrasted his pernicious behavior to the noble attitude of Cimon. While this rival of Pericles used his own fortune “in embellishing the city and relieving the wretched,” Pericles used the public treasury of the Athenians and that of the allies, with the sole aim of flattering the multitude: “The people, seeing only the hand that gave, shut their eyes to the source from whence it drew. They became more and more united to Pericles who, to attach them still more strongly to himself, rendered them the accomplices of the repeated acts of injustice of which he was guilty.”82 This was doubly unjust, for, as a result of Pericles’ demagogic maneuvers, Cimon was ostracized and the Areopagus was marginalized. “Under frivolous pretexts, [Pericles] destroyed the authority of the Areopagus, which vigorously opposed its influence to his innovations and the growing licentiousness of the times.”83

After driving away the aristocrat Thucydides, his last major opponent, the stratēgos is represented as having exercised his power without restraint and all the more effectively given that he never made a show of it. Like a skillful illusionist, Pericles governed hidden in the shadows, so that the people did not notice that he was manipulating it: “Everything was governed by his will, though everything was apparently transacted according to the established laws and customs; and liberty, lulled into security by the observance of the republican forms, imperceptibly expired under the weight of genius.”84

Beyond the city, Pericles’ behavior is represented as equally deplorable. Admittedly, Barthélemy recognizes his wise decision not to increase the conquests of Athens. “When he saw the Athenian power attain to a certain point of elevation, he deemed it disgraceful to suffer it to decline and a misfortune any farther to augment it. All his operations were governed by this consideration and it was the triumph of his politics so long to have retained the Athenians in inaction while he held their allies in dependence and kept Lacedaemon in awe.”85 Yet that strategic prudence was counterbalanced by his extreme rigor where the allies were concerned; all their revolts were crushed in bloodbaths of violence. Where the other nations of Greece were concerned, “Pericles was odious to some and formidable to all.”86 As an all-powerful demagogue within the city and a pitiless oppressor beyond it, Barthélemy’s Pericles had no saving graces at all.

The account of the Peloponnesian War does nothing to dispel this negative impression. On the contrary, according to Abbé Barthélemy, the conflict even dissipated the illusion that the stratēgos, with his genius, had created, for it brought to light the true extent of the corruption in the city: “At the commencement of the Peloponnesian war, the Athenians must have been greatly surprised to find themselves so different from their ancestors. A few years had sufficed to destroy the authority of all the laws, institutions, maxims and examples accumulated by preceding ages for the conservation of manners.”87 It seemed that in the space of three decades, Pericles had stripped the city of all the virtues painstakingly acquired by previous generations.

Barthélemy considered the increasing numbers of courtesans in Attica to be the very symbol of the general dissoluteness. In his view, Pericles was, if not the promoter of this fashion imported from Ionia, at least a passive accomplice in its development: “Pericles, a witness to the abuse, did not attempt to correct it. The more severe he was in his own manners, the more studious was he to corrupt those of the Athenians, which he relaxed by a rapid succession of festivals and games.”88 Inevitably, the Abbé made the most of the chance to remind his readers of the evil influence of Aspasia, whom he accused of having brought about the war “to avenge her personal quarrels.”89 And his conclusion fell with all the force of a guillotine blade: “Pericles authorized the licentiousness; Aspasia extended it.”90

As if the cup were not by now full, in his summing up Barthélemy blamed Pericles’ Athens for yet another reason. As a man of the Enlightenment, he ranted against the sectarian behavior of Athenians under the reign of the stratēgos: “Under Pericles, philosophical researches were rigorously proscribed by the Athenians and, whilst soothsayers frequently received an honourable public maintenance in the prytaneum, the philosophers scarcely ventured to confide their opinions to their most faithful disciples.”91 By the end of this exercise in character-assassination, the Periclean edifice was shattered from top to bottom: as an illusionist, a demagogue, a tyrant, and an intolerant and corrupting oppressor, the stratēgos was reduced to the anti-hero of a city adrift.

In this historiographical journey of ours, The Travels of the Young Anachar sis deserved, if not such a long detour, at least a pause. For, in the first place, this work presents the most extreme expression of the anti-Periclean tradition, amassing a vast collection of reproaches and gearing them up to a climactic paroxysm. Second, this work’s influence on the cultivated elite groups of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries should not be underestimated,92 for it ran into many editions and was widely diffused. It was this degenerate image of Pericles, produced by a combined reading of Plutarch and Barthélemy, that was particularly prevalent in revolutionary France.

The Opponent of Liberty: Pericles in the Revolutionary Era

The men of the revolution were not sparing in their references to Antiquity. Although the French Revolution regarded itself as a new era, it constantly reverted to the past in order to legitimate itself. This new world presented itself as a return to the Ancients. In the course of the Convention (21 September 1792–26 October 1795), certain ancient heroes became “the saints of the new revolutionary cult.”93

“Everything Had to Be Spartan or Roman”: The Revolution and Antiquity

But which Antiquity? As Volney, the orientalist, observed as early as 1795 in his Lectures on History, “Names, surnames, dress, manners, laws seem all about to become Spartan or Roman.”94 Mainly Roman, it should be said: Jacques Bouineau’s study of the Archives parlementaires and the Moniteur—roughly thirty thousand pages between 1789 and 1799—shows that, in the speeches of the revolutionaries, there are almost twice as many references to Latin culture as there are to that of Greece.95

What is the explanation for this prevalence of Rome? The revolutionaries, steeped in the Latin rhetoric that was taught by the Jesuits and teachers of oratory had, for the most part, received a solid grounding in law (for example, Danton, Desmoulins, Robespierre, Barnave, Pétion, Vergniaud, Barère, Barbaroux, and Saint-Just), and the law taught in the French faculties of the eighteenth century was, essentially, Roman. All that the men of the Revolution knew about Greece was what they had read in the works of Plutarch or Abbé Barthélemy; and, compared to their lengthy exposure to Latin culture, that was very little.96

When the revolutionaries did refer to the Greek world, they usually favored Sparta. Among the Montagnards, this was perfectly clear; according to Robespierre, the city of Sparta “blazed like a streak of lightning through the immense darkness,”97 illuminating humanity and revealing the path to follow. This fascination with the Spartans was often expressed to the detriment of Athens, which was disparaged for its lax manners and the corruption of its morals.98 Not even the sage Solon always escaped their criticisms. Billaud-Varenne crudely contrasted the two rival cities and their respective lawgivers as follows: “Citizens, the inflexible austerity of Lycurgus, in Sparta, became the unshakeable basis of the republic; the weak and trusting character of Solon plunged Athens back into slavery. This is a parallel that reflects the entire science of government.”99 As for Saint-Just, he was equally harsh with ancient democracy, expressing nothing but scorn for a system in which “everything proceeded as the orators directed.”100

Was the image of Athens presented by the Girondins any different?

On this point, we should not be misled by the nineteenth-century historiography, which sets the “Spartan” Montagnards in opposition to the “Athenian” Girondins.101 The Girondins rejected the Spartan mirage, regarding it as nothing but “a dreadful equality of poverty,” but that did not mean that they favored the city of Pericles. For example, on 11 May 1793, the Girondin Verniaud dismissed both regimes, declaring, “I conclude that you do not wish to turn the French into a purely military [that is, Spartan] people, with praetorian guards that hold all the power … nor into a people so beguiled by the soft ways of peace that, like the Athenians, it fears kings that attack it for being enemies of its pleasures rather than enemies of its liberty.”102 So Athens gained nothing from the political divisions that were tearing France apart in the period prior to Thermidor.

Among the revolutionaries, Sparta was often exalted while Athens was frequently reviled. So did the revolutionaries simply take over the clichés that had been elaborated in earlier centuries? That would be too hasty a conclusion to draw, for in truth a number of differences are detectable. In the first place, the revolutionaries invoked the patronage of the great ancient lawgivers with singular acuity. This was a way for them, by analogy, to think through the rupture that they were themselves introducing. The figure of Lycurgus could certainly not be ignored, and his memory was indeed constantly invoked. A bust of the Spartan lawgiver was set up, alongside that of Solon, in the meeting hall of the Convention, when it took over the Tuileries on 10 May 1793.103

Besides, the revolutionaries drew upon a number of other episodes from the Greek past, exalting in particular the occasions when the Greeks had put up a heroic resistance to invaders. Of course, this was hardly surprising at a time when France itself was facing attack from the European powers that were in league against the young Republic. For instance, the Marseillaise (1792) was freely adapted from the paean sung by the Athenians at Salamis, and, in the summer of 1794, three plays relating to the Persian Wars were staged in Paris in less than one month: Miltiades at Marathon, The Battle of Thermopylae, and The Marathon Chorus.104

Following Thermidor and the end of the Terror, other moments from Greek history also came to the fore. Under the Directoire (1795–1799), the Athenians came to be celebrated for their ability to achieve reconciliation after such deep political divisions. In this respect, the action of Solon and the amnesty decreed by Thrasybulus attracted considerable attention: “Thrasybulus was surrounded by a certain aura in post-Thermidor France, owing to the fact that he had helped to impose the unity of the city upon the victorious Democrats of 403. In a France rent asunder, he was regarded as the model of a conciliator and French orators did not fail to mention his name.”105

The Warmonger: The Pericles of the French and American Revolutionaries

In these troubled circumstances, Pericles was mostly conspicuous by his absence. Just as well, probably, for when his memory was invoked, he was portrayed, among the Montagnards and the Girondins alike, as a corrupt aristocrat or even as a liberty-killing tyrant.106

His example was cited in May 1790 already when, in the Constituent Assembly, a question of burning importance prompted intense debate: should the king be stripped of the right to declare war? While the orator Barnave pleaded the cause of the patriotic party, recalling all the unjust and calamitous wars that kings had undertaken, Mirabeau defended the interests of the sovereign, whose secret adviser he then was.

According to Barnave, the right of war should be entrusted to the legislative body, not to the executive power, for a very simple and excellent reason: the National Assembly was less prone to corruption than the king’s ministers. In support of his argument, Barnave cited the case of Pericles, “a skilful minister” who was prepared to spark off the Peloponnesian War “so as to bury his own crimes”: “Pericles embarked upon the Peloponnesian War when he realized that he was unable to justify his accounts.”107

Mirabeau’s reply to him in the Assembly came the very next day, pointing out the inadequacy of that ancient analogy: “He [Barnave] has cited Pericles waging war so as not to have to present his accounts. According to what he says, does it not seem that Pericles was a king or some despotic minister? Pericles was a man who, knowing how to flatter the passions of the populace and win its applause as he left the tribune, by reason of his largesse and that of his friends, dragged Athens into the Peloponnesian War. … Who did? The national Assembly of Athens.”108 In this way, Mirabeau put his opponent straight: in the first place, Pericles was not the king of the Athenians; and second, it was the Athenian Assembly that voted for this disastrous war—not some kind of sovereign. So Barnave’s reference to Pericles did nothing to advance his own cause!109 All the same, over and above their differences, the two orators were in agreement on one point: Pericles was indeed a corrupt and corrupting warmonger.

On the other side of the Atlantic, criticism was equally ferocious. The American republicans, influenced as they were by their readings of Plutarch and Plato, had no sympathy at all for fifth-century Athenian democracy, which they judged to be unstable and anarchical. They far preferred that of Solon.110 But it was the Romans who fascinated them the most. Significantly enough, when the founding fathers of the American nation met in Philadelphia in 1787, they set up, not a Council of the Areopagus, but a Senate that was to meet in the “Capitol.”

Even when not totally ignored, Pericles became a target of virulent attacks. Alexander Hamilton (1757–1802), who founded the Federalist party and was an influential delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention, launched a direct attack on the stratēgos in an article in the Federalist Papers on 14 November 1787. At this point, we should note the importance of this collection of papers. It was designed to interpret the new American Constitution and promote it. Using the pen-name “Publius,” a pseudonym chosen in honor of the Roman consul Publius Valerius Publicola, Hamilton confirmed all the anti-Periclean clichés: “The celebrated Pericles, in compliance with the resentments of a prostitute, at the expense of much of the blood and treasure of his countrymen, attacked, vanquished and destroyed the city of the Samians. The same man … was the primitive author of that famous and fatal war which, after various vicissitudes, intermissions and renewals, terminated in the ruin of the Athenian commonwealth.”111 On both sides of the Atlantic, Pericles was thus presented as an unscrupulous warmonger.112

A Liberty-Killing Tyrant: The Pericles of the Terror