Jennifer Sherman

A lot of people leave and come back. There’s something about staying in a safe community, even in poverty, that’s easier for them than it is elsewhere…. It’s easier to live poor here than it is in the big cities. It’s safer.

—Cathy Graham, fifty-year-old married schoolteacher, Golden Valley, California

It’s not—I call it the rat race, but it’s not wake up, go to work, it’s not that routine of, every day you are surviving to make more money. That’s what—being a parent now, that’s what I really enjoy. It’s not live every day to make more money.

—Chad Lloyd, twenty-eight-year-old married sawmill worker and father of three, Paradise Valley, Washington

INTRODUCTION

What motivates people to live in rural communities, particularly in places where jobs are scarce, and survival is a struggle? Often rural residents will remark that a particular rural community is “a good place to raise a family.” When prodded for more detail on what this means to an individual, many talk about beauty, safety, a slow pace of life, and being “out of the rat race.” These idealized understandings of what it means to live in a rural community both capture and leave out much of what is vital to understanding the challenges and rewards faced by rural families. This chapter explores the types of resources rural families rely on for survival, social status, and meaning. In particular, it looks at the roles of symbolic forms of capital in rural communities, which both aid and impede families in their various struggles to get by in remote places when jobs and economic capital are scarce.

Many rural communities lack the benefits that draw people to urban and suburban settings, such as retail services, economic opportunities, and racial or ethnic diversity. However, rural life often comes with numerous advantages that residents who are well integrated into a community can draw upon to aid in survival. This chapter investigates and illustrates some of the less tangible forms of rural advantage as well as the types of challenges poor rural families face. The ways in which symbolic capital affects the experiences of poverty, unemployment, and underemployment in rural communities is examined in depth. Two case studies are woven into the chapter that draw on the author’s in-depth qualitative work in two towns in the Pacific Northwest: “Golden Valley,” California, from 2003 to 2004, and “Paradise Valley,” Washington, from 2014 to 2015.1 Both are small, remote, mostly white rural communities that have economic roots in logging, mining, and ranching. Golden Valley’s forest-dependent economy was in collapse during this time, resulting in widespread poverty for its population. Paradise Valley’s economy, on the other hand, had transitioned decades earlier to a heavy reliance on tourism and second-home ownership, resulting in more jobs and economic opportunities but also in deep inequality and persistent poverty at the bottom of the income ladder. The similarities and differences of these communities illustrate the ways in which different types of real and symbolic capital organize social life and influence poor families’ chances of survival in rural American communities.

THE FORMS OF CAPITAL, REAL AND SYMBOLIC

The concept of “symbolic capital” is based on the work of Pierre Bourdieu, who argued that the categories and hierarchies upon which social life is organized are based not solely in differences in income and wealth (“real” or economic capital) but also in differences of other types of resources that are not strictly economic in nature but act in similar ways. He referred to these types of resources as symbolic capital (Bourdieu 1986). Symbolic capital consists of noneconomic boundary markers between people that may be traded for one another, and for economic capital, depending on the social setting. Some of the types of symbolic capital commonly studied by sociologists include social capital, cultural capital, human capital, and moral capital. Social capital consists of one’s social connections and the network-based resources that can be accessed by those within the social network to procure benefits (Bourdieu 1986; Coleman 1988; Putnam 2001). A person’s social network may have resources of time, money, or other goods and services such as food, labor, and access to potential job opportunities, which they share with others in the network. Cultural capital consists of tastes, manners, and preferences that help to distinguish groups of people from each other, such as knowledge of, interest in, and preferences for such things as art, music, and entertainment. In certain circles and social settings, cultural capital may be traded for social connections, as well as potential job opportunities, as in the case of manners and self-presentation, which can help or hurt a job candidate (Bourdieu 1986; Woodward 2013). Human capital consists of investments in individual education, training, and job experience, with higher levels being converted into higher salaries, labor market opportunities, and job benefits (Becker 2009). Finally, moral capital, which has been documented in rural American settings, consists of external exhibitions of one’s morality according to locally constructed norms and understandings. It may be such things as outwardly manifesting one’s work ethic and family values within a community where these values are considered important. Like other forms of symbolic capital, moral capital can be traded for advantages in social settings as well as in school (where human capital is obtained) and in the labor market (Sherman 2006, 2009; Sherman and Sage 2011). Together, the various forms of real and symbolic capital contribute to a person’s social class status within a society and to the person’s life chances, opportunities, and choices.

The relative value and importance of different types of symbolic capital depend heavily on the social setting in which a person or family resides. In many U.S. settings, economic capital, in the forms of income and wealth, dominates social hierarchies and is the strongest indicator and predictor of advantage. Although economic capital is rarely unimportant in a capitalist society, in different settings other types of symbolic capital may be of greater or lesser importance, particularly when economic capital is scarce (Flora and Flora 2013; Sherman 2009). In settings such as remote, high-poverty rural communities, the lack of available economic capital can lead to a heavy reliance on symbolic forms of capital, which enable residents to create and sustain social boundaries and maintain social hierarchies in the absence of significant economic divisions and opportunities. The availability and usefulness of different types of real and symbolic capital constrain opportunities and create relative advantages for people within their unique social settings, depending on the social and economic organization of a community. Particularly when poverty is endemic and economic capital scarce, symbolic forms of capital can play vital roles in structuring social and economic life. Symbolic and real capital, however, are just one way in which social boundaries are built and maintained. In more heterogeneous societies and communities, the effects of symbolic capital are influenced by and intertwined with other social divisions, including those based in race and ethnicity, gender, age, and sexuality. These two case studies describe relatively homogenous communities in which social class plays a pivotal role in structuring social life and in which other axes of division are less central to social organization.

RURAL POVERTY AND THE IMPORTANCE OF SYMBOLIC CAPITAL

In much of rural America, deindustrialization and economic decline have dominated the last half-century, a trend that accelerated during the Great Recession of 2007–2009 (Grusky, Western, and Wimer 2011; Hamilton et al. 2008; Smith and Tickamyer 2011; see also chapter 9 in this book). Across rural America, declines in land-based industries, extractive industries, and manufacturing left many places without strong economies and living-wage jobs, particularly for men. Some rural communities have seen growth in other sectors, such as service and tourism, or growth in new extractive industries, such as hydraulic fracturing. Other communities struggle to reinvent themselves with limited prospects for building healthy postindustrial economies (Hamilton et al. 2008). Lack of jobs and incomes affects rural communities in multiple ways, often resulting in loss of local businesses and decreasing services as well as the destabilization of social life and the out-migration of young adults.

For those who remain in rural communities without economic opportunities, survival options are often constrained by cultural understandings and social structures, which provide the cultural “tool kit” (Swidler 1986) residents have at their disposal for making sense of their lives and defining success and failure. Many rural communities are characterized by cultural conservatism (Bageant 2008; Frank 2004), which often includes understandings that stigmatize poverty, unemployment, and underemployment as individual failures rather than as outcomes of larger structural conditions (Fitchen 1991; Sherman 2009). Such stigma can heavily influence social life and available survival strategies for rural families experiencing economic strain, often limiting access to real and symbolic forms of capital (Sage and Sherman 2014; Sherman 2009; Whitley 2013). Symbolic capital such as social, cultural, and moral capital may help to mitigate conditions of poverty, but symbolic capital also presents challenges for low-income and poor rural families who lack access to this noneconomic resource. The following sections explore ways in which symbolic capital both helps and hinders rural poor families’ survival.

SOCIAL CAPITAL AND RURAL POVERTY

In rural settings in which income and wealth are scarce, the different forms of symbolic capital take on increased importance and have serious positive and negative effects on families struggling to survive. Generations of rural sociologists have documented the importance of social capital in high-poverty rural communities and have studied its benefits for families as well as the challenges faced by those families and communities that lack it. Duncan (1999) documents the stark differences in community outcomes for rural communities that experience high versus low levels of social capital due to social structures and legacies of inequality. Flora and Flora (2013) similarly describe the importance of social capital in rural communities and raise concerns about the ability of communities to defend themselves against economic and social challenges in its absence (Flora and Flora 2014). For families in poor rural communities, social capital can often mean the difference between aid through difficult times and facing difficulties alone (Whitley 2013). Social capital can substitute for economic capital in multiple ways for individuals and families, providing access to job opportunities through social networks and other types of informal support. The following quotes, from interviews conducted in Golden Valley and Paradise Valley, illustrate several different ways in which social capital operates to substitute for economic capital in rural communities.

Grace Prader, a forty-five-year-old secretary and married mother of two in Golden Valley, discusses her inability to find affordable housing due to her family’s low income and the community’s lack of low-cost housing:

We were caretaking a place for seven, eight years. And the guy calls and says, “By the way, I’ve just sold the place.” And I said, “Oh, OK.” And we’d lived there for seven, eight years, we’d accumulated a lot of stuff and a lot of garbage. And so my mother-in-law let us have her camp trailer, and at that point we moved, me and [my husband], and him working, making $7.50 an hour at that time. There’s no way that we could get the down payment to either buy a house or rent. I mean, we just, so my thought was, “Well, we’ll just park a camp trailer down at the fairgrounds.” It was fine. And then we ended up moving into another spot, caretaking it, and she said, “How long are you gonna be here?” I said, “I don’t see us here for more than three years.” She said, “Fine. Then you can have it rent-free.” That was really the only way we could do it on that paycheck.

Shawn Murphy, forty-three-year-old restaurant manager and single father of one in Paradise Valley, describes a lack of child-care options, a constraint that would otherwise affect families not only in their amount of leisure time but in their ability to work at service sector jobs like his, which requires him to be available at night and on weekends:

When it comes to my child-care challenge, it’s like, yeah, on a large scale, there’s a need and a challenge in child care still. But on a small scale, there’s a network of friends that you can always pretty much say, “Hey, you know, can you step in for two hours or whatever? And I’ll help you out.” There’s this whole informal network of tangible support when it comes to some of those—being in a big city, what are you gonna do? Something comes up, and there’s no daycare option, and you may not have that community support network. Everyone’s busy. Everyone else’s kids are in child care, too. And here there’s this flexibility.

Nicole Goodman, a twenty-five-year-old care worker and married mother of two in Golden Valley, discusses community-level charity provided on an informal level for families in need:

If your house burns down, like somebody’s did recently, everybody’s like, “What can we do, what can we do?” They come right over and start donating and helping. There’s not money here, but everybody teams together to take care of everybody.

In all of these examples, social capital provides noneconomic benefits that help families survive in the absence of sufficient economic capital, allowing them to mobilize informal networks to fill in the gaps in economic capacity and formal infrastructure. Grace’s social networks help her through what could otherwise be a serious crisis, providing her with low-cost housing through the community’s informal tradition of having less-privileged families “caretake” property for owners who have moved away in search of better jobs and economic prospects. Caretakers like Grace pay little to no rent in return for taking care of the property for someone who knows and trusts them. For Grace, her social integration provides what neither the labor market nor the community’s infrastructure can, allowing her to substitute social capital for economic capital in the local housing market. Shawn illustrates a similar scenario. Like Grace, Shawn can draw on his social networks to help provide what his income and Paradise Valley’s infrastructure cannot: in his case, after-hours, trustworthy child care.

Nicole’s story illustrates an aspect of social capital that plays a vital role in many cohesive rural communities. It is not uncommon to hear stories like this one in rural communities. Well-known families who experience disasters or illness are helped by the larger community in informal ways, such as throwing spaghetti-feed fund-raisers to help pay for hospital bills, or providing hands-on help with necessary home repairs after a natural disaster. This practice is certainly not unheard of in urban areas, where churches and other civic and social groups may engage in similar acts of collective, informal charity. But it is particularly common in rural communities such as Golden Valley, where formal infrastructure for handling emergencies, disasters, and medical crises is lacking or nonexistent and poor families frequently are un- or underinsured. In the case Nicole described, as in many similar stories from rural residents, social capital compensates for economic capital and aids in survival for socially integrated families who lack significant income or wealth.

In all of these cases, and in many other scenarios throughout rural America, social capital plays an important role in allowing families to share resources with others in their networks to get through difficult times. In places without healthy economies, social capital can become extremely important to survival.

The importance of social capital for rural families does not make it universally available to all, however. It is important to note that families who are not well integrated into their communities will likely lack the social capital they need to get them through difficult times. Lack of integration can occur for multiple reasons, including recent in-migration, prejudices along race or ethnic boundary lines, remote living, or lack of other types of symbolic capital, such as cultural or moral capital. For Paradise Valley resident Allison Lloyd, a twenty-eight-year-old, married, stay-at-home mother of three who moved there eight years earlier, her short tenure in the community, the remoteness of the family’s rented home, and her lack of cultural capital contribute to her isolation from the community’s social networks. She describes a very different experience from that of Shawn Murphy within the same setting. Unlike Shawn, Allison’s inability to find reliable child care prohibits her from taking on paid work, and instead she cares for her children full-time. I asked if she felt that she had enough support for her family, and she responded:

| Allison: |

We have nothing, which has been really hard on my husband and I just for a long while, actually, but the only support we really had in the past was my husband’s dad and his wife, and that was only like once every two months, if that. You know, we could have them watch the kids if we needed to, but we’re pretty much on our own. You know, and that’s really hard to know that we don’t have anybody to turn to if we need something or if we need help with something. |

| Q: |

You really feel that way? |

| Allison: |

Yeah. I mean, we know people. We have acquaintances. We don’t have a lot of really close friends. |

Allison’s discussion illustrates the opposite end of the social spectrum: a low-income family that lacks the kinds of developed social networks that might provide them with social capital. Instead of feeling that her needs are met informally, Allison describes lacking the type of child care support that Shawn has in the same community. As this example suggests, social capital can provide poor rural families with resources, but its lack can create additional challenges in communities that do not have an adequate formal infrastructure to provide for low-income and poor families’ needs. Like other forms of capital, social capital works as a source of social division as well as a resource for those families lucky enough to have access to it. For Allison, it helps to reinforce social exclusion and isolation by further impeding her ability to engage in adult social activities that might require her to have child care. Her isolation then contributes to her lack of social networks, impeding her ability to forge social capital, and creating a feedback loop that is difficult to interrupt.

CULTURAL CAPITAL AND RURAL POVERTY

The importance of cultural capital is often discussed in urban settings where cultural differences can be stark and visible and culture easily categorized as high or low (Bourdieu 1984; Lamont 1992). It is less frequently documented in rural settings where communities are less likely to contain the same level of cultural diversity, and often residents share cultural norms and understandings with little variation. Such is the case in Golden Valley where homogenous cultural understandings provide little space for cultural capital to come into play; rarely did cultural capital play an important role in dividing or structuring social life there. For rural communities with greater diversity, however, culture can become another axis on which social divisions rest and resources are divided and allocated. Particularly in rural communities that have experienced in-migration by newcomers with cultural backgrounds that are distinct from those of long-time residents, cultural distinctions can play an important role in structuring daily life and social and economic opportunities. As with social capital, in these situations, cultural capital may help form and maintain social hierarchies, providing resources and access to some families while simultaneously denying these advantages to others whose cultural norms, beliefs, and expectations mark them as different. Researchers have documented rural community divisions grounded in cultural differences of ethnicity, religion, and sexuality (Crowley and Lichter 2009; Devine 2006; Stein 2001). In these cases, deep cultural divisions allow for judgment and exclusion of one social group by another, resulting in the systematic denial of resources.

Cultural differences do not have to be gaping divides in worldviews and belief systems to provide the basis for social divisions, however. In the case of Paradise Valley, cultural differences are extremely important, but not necessarily grounded in deeply held religious or moral beliefs. In this community, cultural capital is not built on differences in ethnic backgrounds (most residents are white and of European descent) or religious belief systems. Rather, cultural capital is built on differences in tastes and preferences for things such as art, music, food and drink, and leisure activities, as well as differences in aspirations for children’s outcomes. The bulk of affluent newcomers to the area share similar interests in “high culture” forms of art, music, and food and drink (Bourdieu 1984) and strongly prefer outdoor sports activities such as hiking and skiing over leisure pursuits such as television, motorized vehicle use, or video games. These kinds of cultural differences can serve to structure social life, including influencing who is in one’s social networks. Families in Paradise Valley choose different venues for eating, shopping, and recreating, effectively segregating themselves in ways that result in different levels of exposure to cultural capital for children as well as the formation of social networks with vastly different access to economic, social, and human capital. Choosing to go to an upscale coffee shop versus drinking coffee at the grocery store deli affects whom one interacts with socially, as does choosing to drink Budweiser at a modest bar versus craft beer at an upscale pub. For children, going to dance, ski, and music lessons after school results in very different experiences and exposure than does watching television or playing video games at home. Thus, not only can cultural capital be traded for other forms of real and symbolic capital in this setting, but it also serves to maintain and reinforce social divisions.

Hannah Lowry, a well-integrated, middle-class, forty-five-year-old married mother of two, has a college education and an extensive background in art and literature. She explained how she perceives social divisions within the community, which she describes as being based on different interests that belie different cultural norms:

On weekends…we’re out backpacking with a group of friends or doing a day hike with a bunch of ladies. And then I have a book club once a month…. I get to go to book club…and not everybody has that luxury. The people I end up spending time with are the people who have that luxury. But there’s also a lot of families that go hunting together. I don’t want to go hunting, so I’m not friends with those families, because they’re going ATVing and hunting, and they’re having a great time outdoors together with other families who do that. But we’re not. We’re friends to, like, say hi on the street.

Although her description of variations in cultural interests makes them sound benign, for those on the “low culture” side of the divide such as Allison Lloyd (introduced previously), these differences clearly have a hierarchical quality that affects where they stand on the social ladder in Paradise Valley. Here is how Allison described it:

I think that people think that I’m a—that’s why I call myself a redneck. ‘Cause, like my brother came up here and he was like, “God, I can’t believe that you do that. You go hunting? You let your kids ride a 4-wheeler in your front yard?” You know, I think a lot of people, um, there’s a lot of people that have assumptions about me, and that’s fine. They can assume all they want, but I think I’m a good person.

For residents of Paradise Valley, cultural capital opens doors to social capital in important ways. It helps form the basis of the social networks that Shawn Murphy and Hannah Lowry build, which include other educated adults with similar cultural norms as well as resources often of financial and human capital. In this way, social and cultural capital are mutually reinforcing in Paradise Valley. Families with interests in high culture activities take advantage of the community’s opportunities to enjoy art, theater, music, dance, and outdoor recreation and are exposed to others with similar interests—and similar resources—through these pursuits. This contrasts with families with lower culture interests, who often find themselves more isolated from the community and lacking access to formal social opportunities and activities. Cultural capital structures who interacts with whom, and where. For example, when asked about her local activities, Maria Setzer, a forty-year-old artist and married mother of two explained:

I used to play in the orchestra. I did a lot of volunteer stuff for the art gallery…and I used to help facilitate a dance class, we called it freestyle dance, at the studio. I used to do that once a week. So things here and there.

Although Maria’s family lives on less than 200 percent of the poverty line, she feels well integrated in Paradise Valley and has strong social connections there. Her description of social activities differs clearly from that of Wendy Harris, a thirty-seven-year-old, married, stay-at-home mother of one who also survives on the low income provided by her husband’s job as a long-haul truck driver. She explained her community pursuits:

| Wendy: |

I will not go to the theater thingy…. The Easter thing every year that they do, I usually go down and hang out for that. Just that kind of thing… |

| Q: |

Do these things cost money? |

| Wendy: |

They have to be free. They can’t cost me money, especially comin’ off two years of not havin’ any money. It’s gotta be somethin’ that’s—or very minimal cost…. Every weekend my aunt and I make a point of going yard-saling. I know that’s not community, but you know how many people you see at yard sales? [laughs] We see a lot of people at yard sales, so I get most of my social gathering that way. Almost every other day, now that [my husband]’s working and I can afford a cup of coffee, we go to coffee down at [the grocery store]. |

Maria’s cultural pursuits put her family into contact with many of Paradise Valley’s elite residents, but Wendy’s activities ensure that she only interacts with other low-income families who also lack significant cultural capital.

Like social capital, cultural capital in Paradise Valley serves to help some families gain access to social and human capital while effectively barring others. Those with high amounts of cultural capital can maintain their social status whether or not they have significant income or wealth, which increases their ability to build and utilize social capital. Those lacking cultural capital encounter boundary lines that effectively exclude them from many of the community’s other resources, exacerbating both financial strain and social isolation. In these ways, cultural capital, similar to social capital itself, can either ease the strain of poverty and low income or further disadvantage individuals and families.

HUMAN CAPITAL AND RURAL POVERTY

In most parts of the United States, it is taken for granted that education and training are required to succeed in the labor market. In rural communities, however, human capital can operate differently than it does in places with more diverse economies and opportunities. In communities where jobs for more educated adults are scarce, the outcome of advanced education can be more complicated. As in urban communities, in rural communities human capital is often vital in securing better jobs, incomes, and benefits, but returns to human capital are often lower in rural areas, particularly when highly skilled and high-paid jobs for more educated adults are scarce. Rural scholars have long expressed concern over the problem of “brain drain” in rural communities as young adults, often the community’s “best and brightest,” out-migrate to pursue education and work opportunities elsewhere (Carr and Kefalas 2009; Corbett 2007; Petrin, Schafft, and Meece 2014; Sherman and Sage 2011). Advanced education often offers the promise of better lives for young adults, but without significant job opportunities or amenities to lure them back home, education can become the vehicle that strips rural communities of talented and energetic individuals who leave to pursue better opportunities elsewhere. Some may return with increased human capital to invest in their home communities, but many do not. The brain drain process decreases human capital at the community level, and it often results in demographics skewed toward older adults. In such places, local schools are the channel through which the brain drain process often begins.

Despite its contribution to brain drain, human capital is important for finding and securing employment in most labor markets, including rural ones. For Angelica Finch of Golden Valley, a thirty-eight-year-old grade school secretary and married mother of three, lacking a high school diploma meant more than a decade of low-wage and insecure jobs that didn’t lift her family above the poverty line. For Angelica, it took years of going to school hours away while working full time to secure an AA-degree. But as she explained, the degree opened doors to a better job for her, allowing her to pull her family out of poverty: “The education paid off, but it took a long time…. [Without my education] I don’t think we would’ve made it.”

For twenty-eight-year-old Chad Lloyd of Paradise Valley, who dropped out of high school and later earned his GED, lacking a high school diploma meant having to work his way up from sweeping floors to prove himself to his employer.

| Chad: |

I strongly believe that if an employer sees that you got your GED, either he thinks that a) you’re a quitter, you decided you didn’t want to do it, or b) you had something major come up in your life, and you weren’t able to finish school. And I think that a) is a big part of it. “You didn’t even finish high school. Why should I hire you?” |

| Q: |

So you think it’s been a stigma? |

| Chad: |

I think so, a big one. |

In Chad’s case, he was able to slowly gain skills on the job and rise through the ranks, investing in human capital through experience. But the years he spent working for poverty-level wages put his family at a financial disadvantage, and he still struggles to support his wife Allison and their three children. Owning a house, a dream for the couple, is perpetually out of reach. As these examples suggest, human capital investment can make an important difference between poverty and the hopes of a middle-class existence for rural families, just as it does in urban settings.

Human capital can be very important in rural labor markets, but it doesn’t always provide the expected payoffs. Before Golden Valley’s economic collapse and Paradise Valley’s shift to a tourism-focused economy, the mainstays of both communities were forest-based jobs, many of which didn’t require or demand a college degree, or even a high school diploma. In many rural communities, there are insufficient jobs for those with higher training and education, making the rewards of human capital less certain. For thirty-three-year-old Sabena Griffin, a cohabiting mother of two, college was always a goal: “I was like, I got to support myself. I’m going to college because I am not going to depend on anybody.”

The Paradise Valley native put herself through college with summer jobs and student loans to gain a specialized nursing degree. However, jobs in her field are not available in Paradise Valley, and Sabena has to commute nearly an hour over a mountain pass for work. Since having her second child, she wonders whether the commute is worth it, and considers leaving the area:

I think the only thing that would keep me from staying here is if I couldn’t support my family, and that’s hard when my job is so specialized. And so I commute to Grass Flats, and that is daunting with a three-month-old. You know, I look at that, and I am like, oh my gosh, I don’t know how I am going to do it. And so I am thinking about cutting back my hours to not be full time and just kind of fill in. But I don’t know if I can afford it…. [But] it is a very dangerous road. There has been some days where I am like, oh my goodness, I shouldn’t have drove today.

These types of challenges make the acquisition of human capital a complicated issue in many rural communities, and often the brain drain dilemma contributes to ambivalence regarding the purpose and value of education.

The following quotations illustrate this range of perspectives on the importance of education, as well as the correlation between human capital and employment.

April Layton, thirty-two-year-old secretary and married mother of two, Golden Valley:

I want [my children] to leave Golden Valley, and go to college, and then if after they do something with their lives that way, if they choose to come back and can make a living, then they’re welcome to come back. I really want them to leave.

Tilda Conner, thirty-six-year-old care worker and cohabiting mother of one, Paradise Valley:

I hope that she goes to college. She’s got so many great ideas. And I want her to be—every parent wants their kid to be better than they were, and I do.

Greg Smith, forty-two-year-old unemployed married father of two, Golden Valley:

In all my life, a high school diploma wasn’t something that was necessary to do anything but go on to the next school. I mean, a job resume, who wants to know if you’ve got a high school diploma? You know, and then everybody I’ve seen go to college, including myself, it didn’t affect their life at all hardly.

Caleb Graham, twenty-six-year-old unemployed, single, Paradise Valley:

I wasn’t the best student. Actually, I was a horrible student. I kind of kick myself in the butt now, ’cause I know I could have done better, but I was angry at everyone and just figured it was a waste of my time.

Payoffs to human capital in cohesive rural communities are often further complicated by local perceptions of individuals such as Caleb, who don’t leave, and the assumption that out-migration is the only worthwhile path. Young adults who leave to pursue education are often welcomed back to their communities (Carr and Kefalas 2009; Fitchen 1991), and those who don’t leave are often judged as unworthy on multiple levels. The following quotes illustrate negative impressions of local kids who fail to out-migrate in pursuit of higher education.

Hannah Lowry, forty-five-year-old nonprofit employee and married mother of two, Paradise Valley:

Nothing good happens to kids who stay here without going somewhere else. It’s a very small community there are a lot of small—“small-minded” is too harsh—conservative values. There’s nothing a kid can do here work-wise after high school that’s at all challenging or rewarding.

Jeff Taylor, thirty-three-year-old mechanic and married father of two, Golden Valley:

The ones we get to keep are the ones that you didn’t want. You want ’em to leave. Seems like that’s what happens a lot. And that happens with a lot of the drugs I think around here. You know, the ones that have no future, I mean just didn’t get an education, or they’re stuck here, they turn to drugs.

Human capital plays a complex role for adults and children in many rural communities. Although education has the potential to allow low-income and poor children to improve upon their parents’ social and economic trajectories as adults, when rural communities lack job opportunities, out-migration may be necessary for returns on human capital investment (Carr and Kefalas 2009; Corbett 2007). Furthermore, human capital is often more accessible to those with more real and symbolic capital resources, and those who lack such advantages frequently encounter greater struggles in school and in acquiring education, leaving them even more disadvantaged in their communities’ social settings and labor markets (Calarco 2014; Fan and Chen 2001; Lareau 2003; Sage and Sherman 2014; Sherman and Sage 2011; Smith, Brooks-Gunn, and Klebanov 1997). Human capital can be an advantage, but it also can help to reproduce disadvantage by funneling communities’ best resources—their most talented and promising young adults—away into more urban settings. This process cuts these young adults off from their families and communities and leaves rural places with fewer educated and energetic leaders to help shape their futures.

MORAL CAPITAL AND RURAL POVERTY

In Golden Valley, outwardly exhibiting one’s moral worth resulted in opportunities that were denied to those who appeared to lack it. Similar to other forms of symbolic capital, in this setting, morality worked to create boundaries between people and could be traded for other resources such as job opportunities and social capital. Why did morality come to be so important that it evolved into a form of capital that could be traded? Research suggests that for people living on the margins of U.S. society, struggling with both poverty and job loss, conceptions of morality can help create new understandings of what it means to be successful (Bourgois 1995; Gowan 2010; Purser 2009; Sherman 2009). In Golden Valley, notions of proper work ethic and morally acceptable activities help create those definitions of success. At the same time, these moral understandings influence the choices people make about how to best survive unemployment and poverty, dictating proper behaviors and coping strategies. In this community, being able to illustrate your moral fortitude in the face of struggle is as important as having a high income (Sherman 2006, 2009). Subsequent work has documented the ways in which moral capital comes into play in the pursuit of multiple types of resources, including access to education (Sage and Sherman 2014; Sherman and Sage 2011) and healthy food (Whitley 2013).

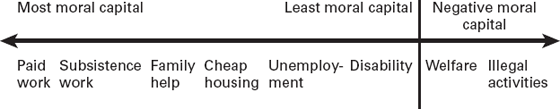

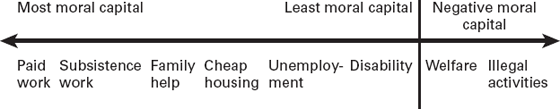

In small, homogenous rural communities, qualities such as independence and hard work often form the basis of moral capital, which can be traded for both economic benefits and social status. In many such communities, people’s activities are visible and known. For those who manifest their work ethic and moral values through culturally acceptable work activities—paid jobs, subsistence work, and even through the receipt of “earned” government aid such as Unemployment Insurance—there can be payoffs in both social support and economic opportunities. For those who fail to illustrate their moral worth—either through receipt of means-tested government aid or involvement in illicit activities such as drug dealing—both labor market opportunities and informal charity are frequently limited. Figure 8.1 illustrates the range of morally acceptable and unacceptable coping activities in Golden Valley. In this community, the importance of moral capital means that the majority of residents do their best to avoid stigmatized coping strategies, regardless of how badly they might need them. Thus, morality is both a positive force, helping people to access social and economic capital, and a negative control that discourages behaviors seen as damaging to the community and its families, whether or not they might aid in survival.

Figure 8.1 Moral value of coping strategies in Golden Valley.

Source: Sherman (2009, 68).

For many Golden Valley residents, the community’s moral norms, which include a strong stigma around means-tested programs such as Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF, also known colloquially as “welfare”), convince them to find other ways to survive. For example, George Woodhouse, who worked at the sawmill for thirty years before losing his job, explained why he and his wife choose subsistence activities such as hunting and fishing to supplement their diet rather than utilizing means-tested government aid programs:

We don’t try to get food stamps or welfare or anything like that. I mean, basically, we probably could. But I don’t know—we were always brought up that you worked for what you got, you didn’t have welfare and stuff like that. If you didn’t work, then you cut back on what you was eatin’ until you got a better job.

Rather than relying on the government to provide for them, Golden Valley residents often rely heavily on the local environment and their physical labor. Although men like George might no longer have jobs, they can still manifest work ethic in other ways, often through informal work. Continuing to manifest one’s work ethic through these sorts of activities, even when lacking a paying job, signals to others in the community that you are still an upstanding, moral citizen rather than a lazy, immoral “freeloader.” Emily Richards, a married mother of two, explained that “you want people to think you’re a hard worker” whether or not you can find paid work. For those who choose survival strategies that display moral capital to the community, the result is frequently better access to social support and social capital as well as to job opportunities.

Although it does not play as large a role in structuring daily life and behavioral choices in Paradise Valley, the importance of moral capital is visible there too. Sporadically employed and often homeless, Caleb Graham (introduced in the previous section) spoke about the difficulties he’d had in school, including a learning disability and a reputation as a troublemaker. His struggles dampened his interest in education, and he barely graduated from high school and did not pursue advanced education. His lack of human capital consigns Caleb to the bottom of Paradise Valley’s labor market, but his lack of moral capital damages him more deeply, making finding and keeping even low-wage jobs difficult for him:

| Caleb: |

I’d work for however long they needed me and then I’d go someplace else. They either wouldn’t want to hire me or the only way I’d get paid is if I worked under the table. |

| Q: |

Why would that be? |

| Caleb: |

Mostly I don’t know, but it’s also because apparently I’ve gotten a reputation around the valley, I’m not sure how, as a drug dealer, a troublemaker. I look at ‘em, and I’m like, “Really? I’ll take a drug test right now. I don’t do drugs.” |

| Q: |

A drug dealer? |

| Caleb: |

Yeah, ’cause it’s like, my dad was friends with a couple of drug dealers, and apparently they connected dots. I’m like, “You can connect all the dots you want. It’s not gonna add up.” Some of my friends are partiers, and just because I’m friends with them; they think that I’m like that, too. It’s hard to change what people think on first glance. |

As Caleb illustrates, moral capital often operates at the family level. Moral stigma, or negative moral capital (Sherman 2006), can brand entire extended families as unworthy of jobs, education, or community help throughout the life course. In both Golden Valley and Paradise Valley, multiple families complained about difficulties that occur in local schools when children are believed to come from families who lack moral capital. Schools and teachers heavily invest in the children of families with high moral capital, treating them as if destined for greatness, but children whose families lack moral capital frequently receive little investment from schools and teachers. Derek Lloyd, a thirty-eight-year-old married public employee and father of two in Golden Valley, explains it this way:

Now there’s a percentage of kids in school that it wouldn’t even dawn on ’em to go work for it, and [they think] somebody’s gotta give that to me. And I see that a lot here. We have in some cases third and fourth generation of welfare families that that’s almost their legacy. I mean, they wouldn’t even think about college, or think about what their career is. You know, why would you? And you know, that scares me.

Wendy Harris, a thirty-seven-year-old married, stay-at-home mother of one in Paradise Valley, has another outlook:

Well, I was a straight-A student up until high school, and then from there, that’s when—I don’t know, things changed. I don’t know why…. Well, the principal at the time, the system up here at the time, if you got in trouble, you had to go to an in-house, which is, you’re stuck in this tiny little room all day doin’ your work. Sometimes it didn’t have windows, you didn’t even have a window. But if you proceeded to get caught again or anything, you got suspension. He never gave me suspension. He kept me in that room. And I would get in trouble for the stupidest things at times. It got to the point where—and this was because my cousins were ahead of me. And I’m the spittin’ image of my cousin. So he figured I’d be just as much trouble. So the slightest thing I did, I got in trouble. And that’s when I gave up. I gave up trying to pull the straight A’s and stuff like that. I gave up. If I’m gonna be in trouble for stupid things, you know, forget it.

Jeff and Rosemary Taylor, thirty-three-year-old mechanic, thirty-six-year-old school secretary, and married parents of two in Golden Valley, explain:

| Jeff: |

You can almost pick, he’s not gonna make it, he’s gonna make it. Not necessarily exactly, ’cause you know, some can turn it around, do some good things. But then there are those other ones that, just their history and what their family’s done and what they’re doing, you just see the same pattern of going the wrong way. It’s kind of hard, especially since you know the families so well…. |

| Rosemary: |

It’s like they don’t have a chance. You know, they’re labeled…[by] the teachers and stuff. I mean, a lot of ’em are you know, really smart. And I’ve heard people say, “Well, look at his dad. He’s gonna wind up just like his dad.” You know, that’s not good. |

As with other forms of symbolic capital, moral capital can work in both positive and negative ways in rural communities. For those who have large amounts of moral capital, manifesting one’s morality can mean access to other forms of symbolic capital, including economic capital in the form of job opportunities; social capital in the form of strong, supportive networks willing to provide both economic and informal help; and human capital in the form of encouragement, teacher attention, and positive reinforcement in school. But for those families who lack moral capital, these forms of advantage can be difficult to access, leaving them without significant resources and exacerbating the struggles that poor families face. Particularly difficult for poor rural residents is the cultural notion that paid work is the most moral activity and that aid is seen as lacking moral value. For those who are unable to find paid work, they must choose between survival strategies that often bring in little economic capital, but help garner moral capital, and those that bring in more income (e.g., TANF or illegal activities), but lack moral capital. In either case, survival options are limited and come with repercussions.

For poor and low-income rural families, the various types of symbolic capital provide important means for gathering resources and meeting basic needs in the absence of sufficient income or wealth. As this chapter has illustrated, symbolic capital can be traded for both monetary and nonmonetary resources including child care, housing, jobs, education, aid, and social support. For poor individuals and families who have high amounts of symbolic capital, surviving on lower incomes can be somewhat more manageable, enabling people to live more comfortably and enjoy the quiet, safety, and escape from the “rat race” that rural communities can provide. For many such families, symbolic capital is at the base of the seemingly intangible benefits that they feel come with living in small, cohesive, rural communities.

For poor individuals and families who lack symbolic capital, this lack becomes another means of exclusion, exacerbating and deepening poverty, marginalization, lack of opportunities, and lack of power. This chapter focused on communities in which real and symbolic capital form the main sources of division and inclusion, but in more complex and diverse rural communities, such forms of capital can be just one part of a larger system of boundaries and exclusions based on attributes such as race and ethnicity, which are discussed in depth elsewhere in this book. As the stories in this chapter have illustrated, symbolic capital can provide access to resources, but it also can provide sources of division within communities—whether communities are more homogenous or more diverse. For those whose experiences, understandings, cultural norms, or behaviors cause them to lack access to significant amounts of symbolic or real capital, the social divides that symbolic capital creates, exacerbates, and reproduces can mean even greater challenges and struggles. Particularly in communities where formal structures for combating or easing poverty such as shelters, charitable organizations, and food banks are lacking, those families who are unable to access informal support through trading symbolic capital often find themselves worse off than they might be in larger cities with more formal infrastructure for these types of support. Symbolic capital provides many of the benefits that are often associated with rural life, but it also creates and sustains many forms of exclusion that further disenfranchise the most marginal and struggling individuals and families.

Jennifer Sherman

The two field sites that inform this chapter were chosen specifically for their similarities to and their differences from one another. In many ways, they represent the extremes on the spectrum of possibility for rural communities with declining natural resource bases. Hamilton et al. (2008) argue that there are four types of rural American communities: chronically poor communities, declining resource-dependent communities, amenity-declining communities, and amenity-rich communities. Chronically poor communities tend to have the fewest resources and the worst prospects, whereas amenity-rich communities tend to be doing the best in both economic and population growth. According to this scheme, Golden Valley would be a declining resource-dependent community, and Paradise Valley would be an amenity-rich community.

This typology hides much of what is similar about these two communities. Both are located in steep mountain ranges in the Pacific Northwest and have economic roots in mining, logging, ranching, and farming. These once-bustling industries declined precipitously throughout the region in the latter half of the twentieth century. For Golden Valley, the collapse of the forest industry decimated the local economy, resulting in a rapid loss of men’s jobs that were not replaced. These changes left families without male earners and meant widespread poverty and economic struggle around the valley. Paradise Valley might have been on a similar trajectory but for its transition into a tourism-based economy built around its outdoor amenities. As extractive industries dried up and the Forest Service down sized, increasing numbers of weekend visitors, second-home owners, and amenity migrants entered the valley, changing it forever. Recent waves of in-migrants have included counterculture hippies, back-to-the-landers, wealthy retirees, and young families hoping to get away from the fast-paced lifestyle of Seattle and other western cities. For many in-migrants, moving to Paradise Valley means significantly lower incomes than they had elsewhere, but often the wealth they bring with them allows them access to homes and financial security that their current incomes would have been insufficient to provide.

Golden Valley has remained a mostly small and homogenous community. Paradise Valley grew and experienced housing and population booms and now is a much more diverse community where residents differ in income, wealth, education, cultural norms, and experiences. These differences translate into very different social systems and systems of social boundaries.

In Golden Valley, the community’s lack of meaningful distinctions meant that most real and symbolic forms of capital played insignificant roles in structuring social life there. Few residents had significant wealth or income, so economic capital did not provide a common source of social class status. Similarly, the community shared a long history and had experienced little in-migration, so culture remained mostly shared by residents and provided little basis for distinction or social boundaries. Although human capital mattered to a degree, the lack of jobs also muted rewards for education in Golden Valley. Social capital did play an important role in residents’ lives, however, and was traded mostly for the types of in-kind help described in this chapter. The form of symbolic capital that became most salient in this setting was moral capital, which provided the strongest axis along which the community could divide itself, allowing people with little access to money or education to prove themselves successful in work ethic and family values. In Golden Valley, notions of proper work ethic and morally acceptable activities helped create those definitions of success. At the same time, these moral understandings influenced the choices people made about how to best survive unemployment and poverty, dictating proper behaviors and coping strategies. For residents of Golden Valley, this form of symbolic capital heavily influenced both their life choices and their social standing in the community.

Paradise Valley, with its diversity, provided access to multiple forms of real and symbolic capital, which resulted in a much more complex system of social boundaries and social divisions. Although incomes were constrained by the labor market and its dearth of higher-paying jobs, wealth was not similarly absent. Many residents brought significant wealth to the valley from their previous jobs and homes, invested in real estate that provided more wealth, and the processes of gentrification raised land values around the area. For those long-time residents who had inherited land, this process also increased their wealth. Thus, access to wealth and land provided a significant source of social division in Paradise Valley. In this community, other sources of symbolic capital were abundant as well. Many new residents brought high levels of human capital with them, allowing them to out-compete less-educated residents in the local labor market. Higher levels of education and job experience were necessary for most year-round, better-paid, and flexible jobs there, including those in schools, medical care, nonprofit organizations, environmental research, and even higher-end construction and carpentry. Thus, human capital provided another important axis of distinction and division. The same was true of cultural capital, which as this chapter illustrates, differed greatly between newcomers and valley natives. Moral capital also came into play in Paradise Valley in ways similar to Golden Valley, and a family’s moral status could affect children’s chances in school or adults’ chances of finding employment. Finally, social capital differed greatly between those who did and those who did not have multiple forms of symbolic and real capital to trade, resulting in social networks with very high amounts of resources, networks with very few resources, and the exclusion of families who were from both advantaged and disadvantaged networks.

As these two communities illustrate, the social, economic, and labor market structure of a rural community heavily affects both the ways in which it divides itself and the chances residents have for success within it.

NOTE

1. To protect the confidentiality of participants, all names of people and places in this chapter are pseudonyms.

REFERENCES

Bageant, Joe. 2008. Deer Hunting with Jesus: Dispatches from America’s Class War. New York: Crown.

Becker, Gary S. 2009. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

——. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed. John G. Richardson, 241–58. New York, NY: Greenwood.

Bourgois, Philippe. 1995. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Calarco, Jessica McCrory. 2014. “Coached for the Classroom: Parents’ Cultural Transmission and Children’s Reproduction of Educational Inequalities.” American Sociological Review 79(5):1015–37.

Carr, Patrick J., and Maria J. Kefalas. 2009. Hollowing Out the Middle: The Rural Brain Drain and What It Means for America. Boston: Beacon.

Coleman, James Samuel. 1988. “Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital.” American Journal of Sociology 94(supp.): S95–120.

Corbett, Michael. 2007. Learning to Leave: The Irony of Schooling in a Coastal Community. Nova Scotia, Canada: Fernwood Publishing.

Crowley, Martha, and Daniel T. Lichter. 2009. “Social Disorganization in New Latino Destinations?” Rural Sociology 74(4):573–604.

Devine, Jennifer. 2006. “Hardworking Newcomers and Generations of Poverty: Poverty Discourse in Central Washington State.” Antipode 38(5):953–76.

Duncan, Cynthia M. 1999. Worlds Apart: Why Poverty Persists in Rural America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Fan, Xitao, and Michael Chen. 2001. “Parental Involvement and Students’ Academic Achievement: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Psychology Review 13:1–23.

Fitchen, Janet M. 1991. Endangered Spaces, Enduring Places: Change, Identity, and Survival in Rural America. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Flora, Cornelia Butler, and Jan L. Flora. 2013. Rural Communities: Legacy and Change, 4th ed. Boulder, CO: Westview.

——. 2014. “Community Organization and Mobilization in Rural America.” In Rural America in a Globalizing World: Problems and Prospects for the 2010’s, ed. Elizabeth Ransom, Conner Bailey, and Leif Jensen. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press.

Frank, Thomas. 2004. What’s the Matter with Kansas? How Conservatives Won the Heart of America. New York: Metropolitan.

Gowan, Teresa. 2010. Hobos, Hustlers, and Backsliders: Homeless in San Francisco. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Grusky, David B., Bruce Western, and Christopher Wimer. 2011. “The Consequences of the Great Recession.” In The Great Recession, ed. David B. Grusky, Bruce Western, and Christopher Wimer, 3–20. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Hamilton, Lawrence C., Leslie R. Hamilton, Cynthia M. Duncan, and Chris R. Colocousis. 2008. “Place Matters: Challenges and Opportunities in Four Rural Americas.” Carsey Institute Reports on Rural America 1(4):2–32.

Lamont, Michèle. 1992. Money, Morals, and Manners: The Culture of the French and American Upper-Middle Class. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lareau, Annette. 2003. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Petrin, Robert A., Kai A. Schafft, and Judith L. Meece. 2014. “Educational Sorting and Residential Aspirations Among Rural High School Students: What Are the Contributions of Schools and Educators to Rural Brain Drain?” American Educational Research Journal 51(2):294–326.

Purser, Gretchen. 2009. “The Dignity of Job-Seeking Men.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 38(1):117–39.

Putnam, Robert D. 2001. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Sage, Rayna, and Jennifer Sherman. 2014. “ ‘There Are No Jobs Here’: Opportunity Structures, Moral Judgment, and Educational Trajectories in the Rural Northwest.” In Dynamics of Social Class, Race, and Place in Rural Education, ed. Craig B. Howley, Aimee Howley, and Jerry J. Johnson, 67–94. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Sherman, Jennifer. 2006. “Coping with Rural Poverty: Economic Survival and Moral Capital in Rural America.” Social Forces 85(2):891–913.

——. 2009. Those Who Work, Those Who Don’t: Poverty, Morality, and Family in Rural America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Sherman, Jennifer, and Rayna Sage. 2011. “ ‘Sending Off All Your Good Treasures’: Rural Schools, Brain-Drain, and Community Survival in the Wake of Economic Collapse.” Journal of Research in Rural Education 26(11):1–14.

Smith, Judith R., Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, and Pamela K. Klebanov. 1997. “Consequences of Living in Poverty for Young Children’s Cognitive and Verbal Ability and Early School Achievement.” In Consequences of Growing Up Poor, ed. Greg J. Duncan and Jeanne Brooks-Gunn, 132–67. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Smith, Kristin E., and Ann R. Tickamyer, eds. 2011. Economic Restructuring and Family Well-Being in Rural America. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Stein, Arlene. 2001. The Stranger Next Door: The Story of a Small Community’s Battle Over Sex, Faith, and Civil Rights. Boston: Beacon Press.

Swidler, Ann. 1986. “Culture in Action: Symbols and Strategies.” American Sociological Review 51(2):273–86.

Whitley, Sarah. 2013. “Changing Times in Rural America: Food Assistance and Food Insecurity in Food Deserts.” Journal of Family Social Work 16(1):36–52.

Woodward, Kerry C. 2013. Pimping the Welfare System: Empowering Participants with Economic, Social, and Cultural Capital. Lanham, MD: Lexington.