2

The Birth of Good and Bad

Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure.

—JEREMY BENTHAM, AN INTRODUCTION TO THE PRINCIPLES OF MORALS AND LEGISLATION

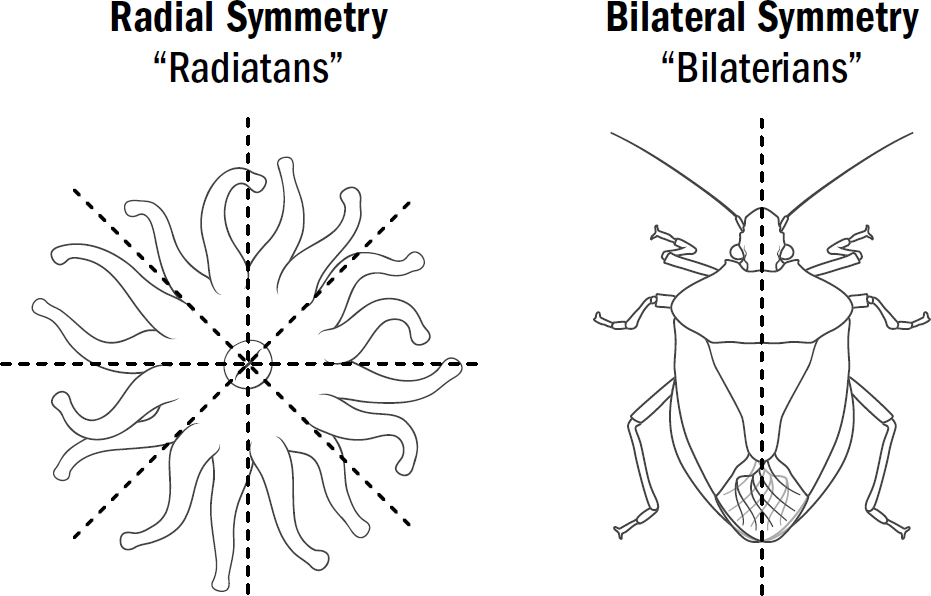

AT FIRST GLANCE, the diversity of the animal kingdom appears remarkable—from ants to alligators, bees to baboons, and crustaceans to cats, animals seem varied in countless ways. But if you pondered this further, you could just as easily conclude that what is remarkable about the animal kingdom is how little diversity there is. Almost all animals on Earth have the same body plan. They all have a front that contains a mouth, a brain, and the main sensory organs (such as eyes and ears), and they all have a back where waste comes out.

Evolutionary biologists call animals with this body plan bilaterians because of their bilateral symmetry. This is in contrast to our most distant animal cousins—coral polyps, anemones, and jellyfish—which have body plans with radial symmetry; that is, with similar parts arranged around a central axis, without any front or back. The most obvious difference between these two categories is how the animals eat. Bilaterians eat by putting food in their mouths and then pooping out waste products from their butts. Radially symmetrical animals have only one opening—a mouth-butt if you will—which swallows food into their stomachs and spits it out. The bilaterians are undeniably the more proper of the two.

Figure 2.1

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

Figure 2.2

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

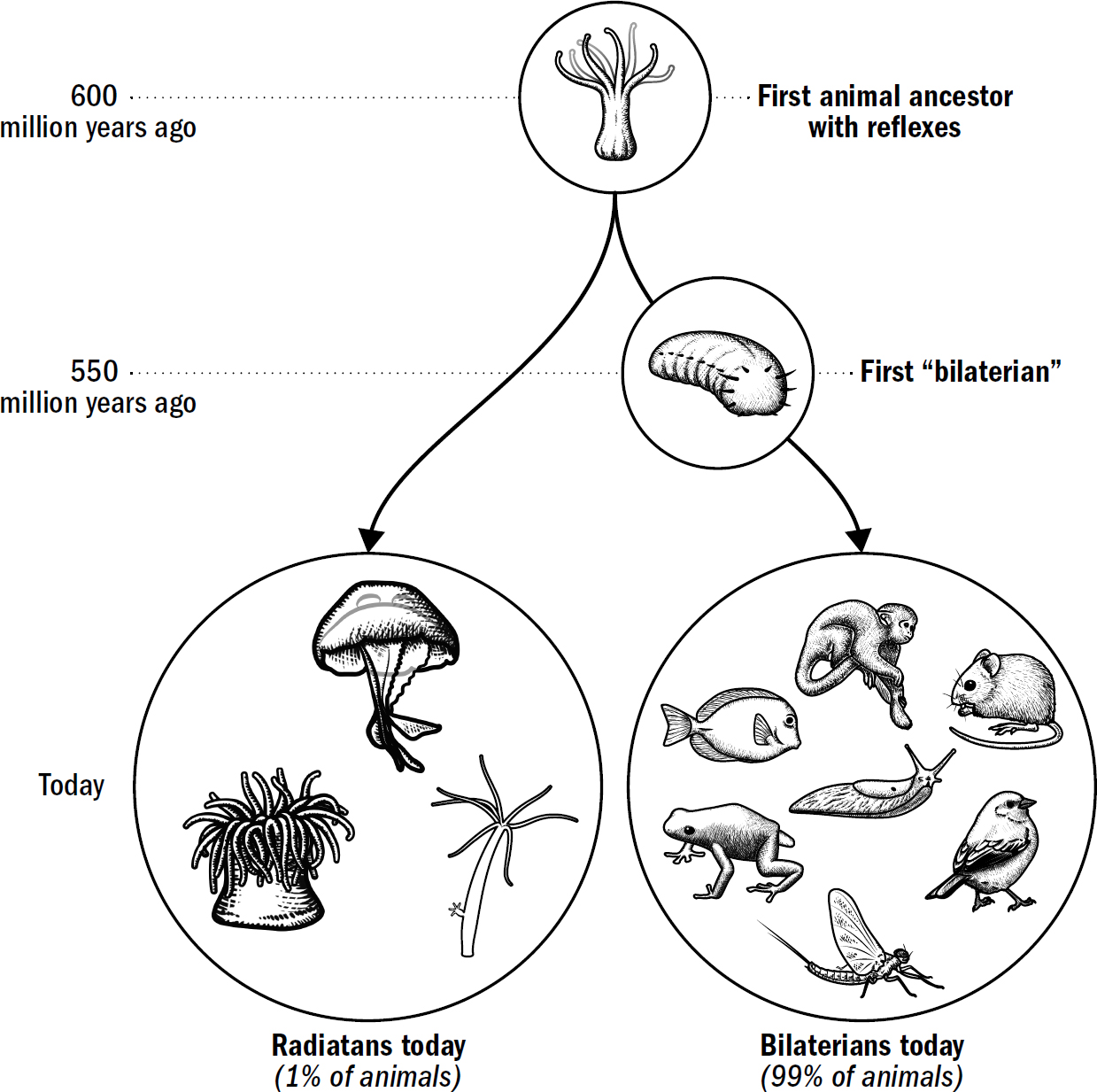

The first animals are believed to have been radially symmetric, and yet today, most animal species are bilaterally symmetric. Despite the diversity of modern bilaterians—from worms to humans—they all descend from a single bilaterian common ancestor who lived around 550 million years ago. Why, within this single lineage of ancient animals, did body plans change from radial symmetry to bilateral symmetry?

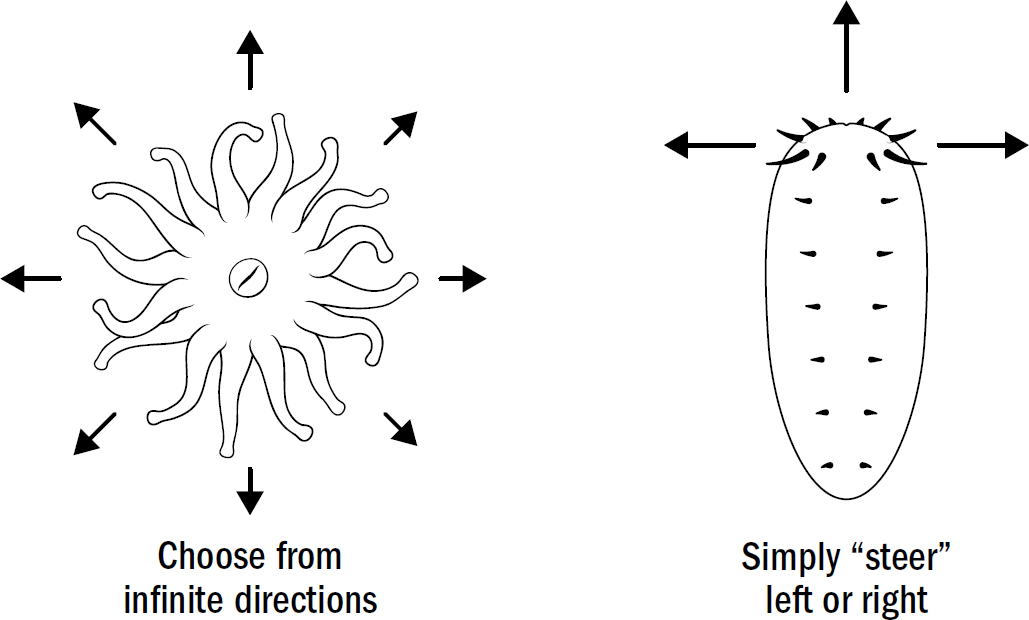

Radially symmetrical body plans work fine with the coral strategy of waiting for food. But they work horribly for the hunting strategy of navigating toward food. Radially symmetrical body plans, if they were to move, would require an animal to have sensory mechanisms to detect the location of food in any direction and then have the machinery to move in any direction. In other words, they would need to be able to simultaneously detect and move in all different directions. Bilaterally symmetrical bodies make movement much simpler. Instead of needing a motor system to move in any direction, they simply need one motor system to move forward and one to turn. Bilaterally symmetrical bodies don’t need to choose the exact direction; they simply need to choose whether to adjust to the right or the left.

Even modern human engineers have yet to find a better structure for navigation. Cars, planes, boats, submarines, and almost every human-built navigation machine is bilaterally symmetric. It is simply the most efficient design for a movement system. Bilateral symmetry allows a movement apparatus to be optimized for a single direction (forward) while solving the problem of navigation by adding a mechanism for turning.

Figure 2.3: Why bilateral symmetry is better for navigation

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

There is another observation about bilaterians, perhaps the more important one: They are the only animals that have brains. This is not a coincidence. The first brain and the bilaterian body share the same initial evolutionary purpose: They enable animals to navigate by steering. Steering was breakthrough #1.

Navigating by Steering

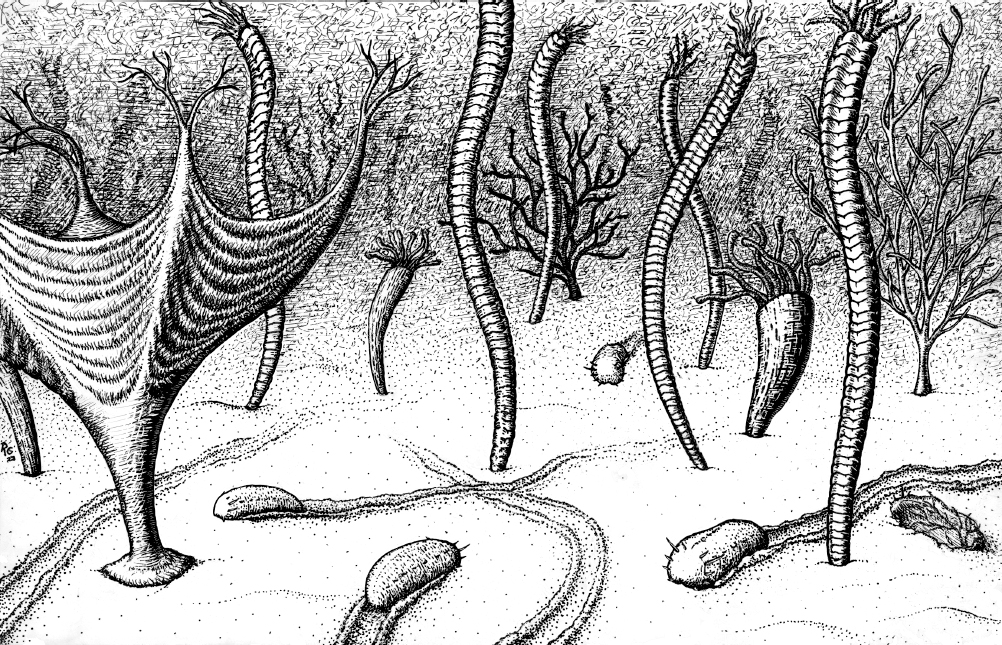

Although we don’t know exactly what the first bilaterians looked like, fossils suggest they were legless wormlike creatures about the size of a grain of rice. Evidence suggests that they first emerged sometime in the Ediacaran period, an era that stretched from 635 to 539 million years ago. The seafloor of the Ediacaran was filled with thick green gooey microbial mats in its shallow areas—vast colonies of cyanobacteria basking in the sun. Sensile multicellular animals like corals, sea sponges, and early plants would have been common.

Modern nematodes are believed to have remained relatively unchanged since early bilaterians; these creatures give us a window into the inner workings of our wormlike ancestors. Nematodes are almost literally just the basic template of a bilaterian: not much more than a head, mouth, stomach, butt, some muscles, and a brain.

Figure 2.4: The Ediacaran world

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

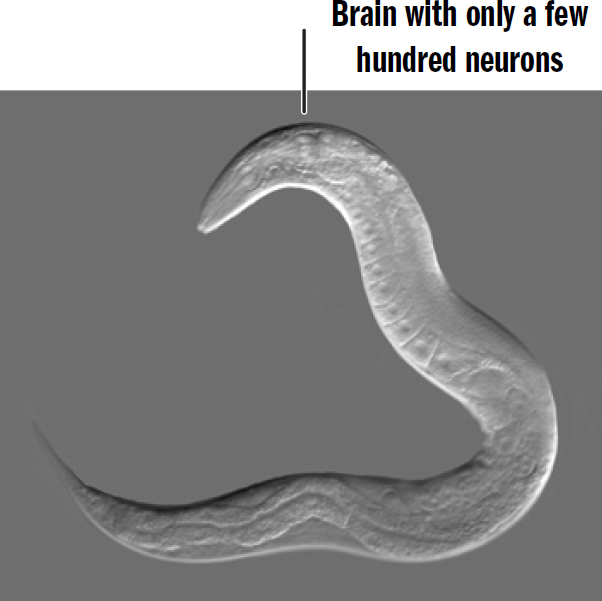

Figure 2.5: The nematode C. elegans

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

The first brains were, like those of nematodes, almost definitely very simple. The most well-studied nematode, Caenorhabditis elegans, has only 302 neurons, a minuscule number compared to a human’s 85 billion. However, nematodes display remarkably sophisticated behavior despite their minuscule brains. What a nematode does with their hopelessly simple brain suggests what the first bilaterians did with theirs.

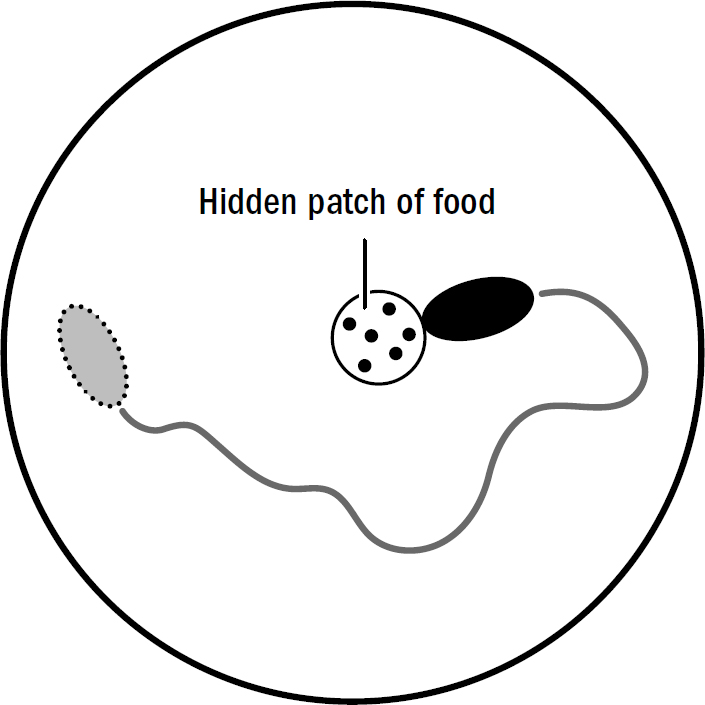

The most obvious behavioral difference between nematodes and more ancient animals like corals is that nematodes spend a lot of time moving. Here’s an experiment: Put a nematode on one side of a petri dish, place a tiny piece of food on the other side. Three things would reveal themselves: First, it always finds the food. Second, it finds the food much faster than it would if it were simply moving around randomly. And third, it doesn’t swim directly toward the food but rather circles in on the food.

The worm is not using vision; nematodes can’t see. They have no eyes to render any image useful for navigation. Instead, the worm is using smell. The closer it gets to the source of a smell, the higher the concentration of that smell. Worms exploit this fact to find food. All a worm must do is turn toward the direction where the concentration of food particles is increasing, and away from the direction it is decreasing. It is quite elegant how simple yet effective this navigational strategy is. It can be summarized in two rules:

Figure 2.6: Nematode steering toward food

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

- If food smells increase, keep going forward.

- If food smells decrease, turn.

This was the breakthrough of steering. It turns out that to successfully navigate in the complicated world of the ocean floor, you don’t actually need an understanding of that two-dimensional world. You don’t need an understanding of where you are, where food is, what paths you might have to take, how long it might take, or really anything meaningful about the world. All you need is a brain that steers a bilateral body toward increasing food smells and away from decreasing food smells.

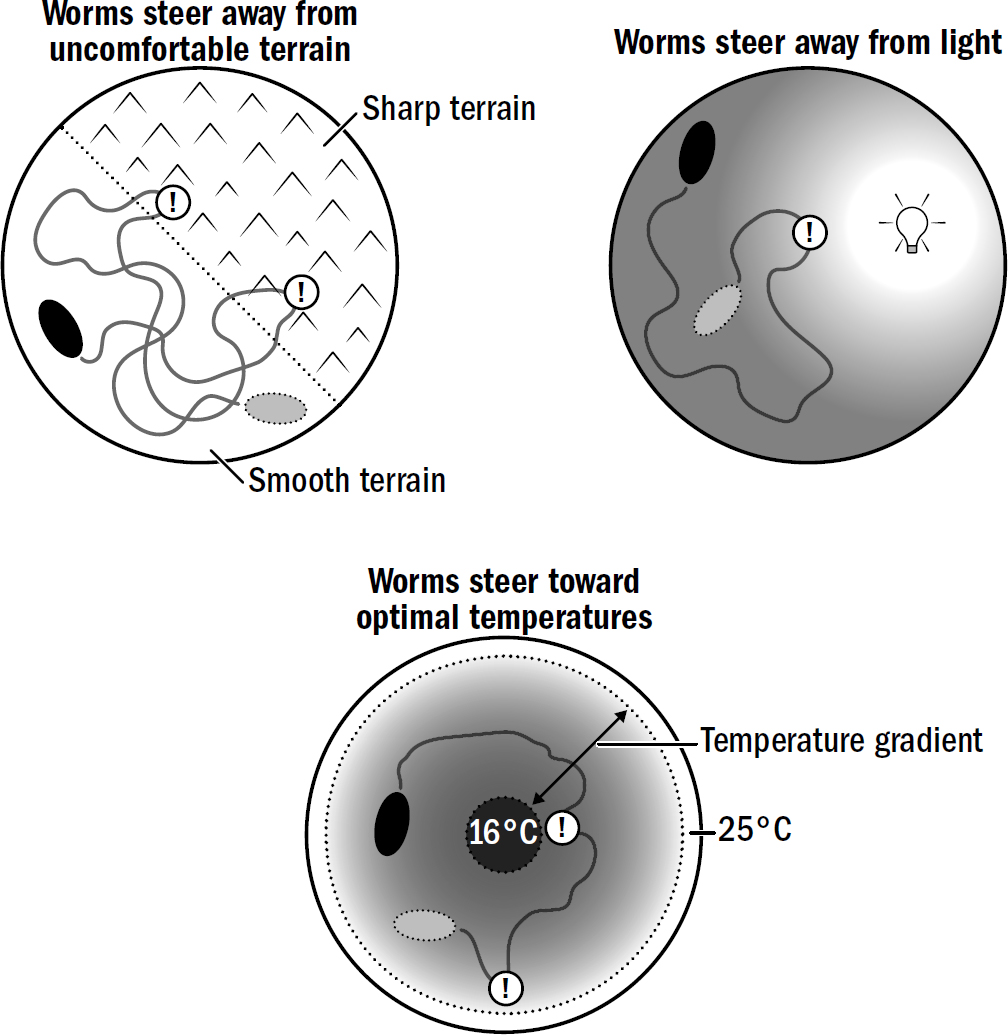

Steering can be used not only to navigate toward things but to navigate away from things. Nematodes have sensory cells that detect light, temperature, and touch. They steer away from light, where predators can more easily see them; they steer away from noxious heat and cold, where their bodily functions become harder to perform; and they steer away from surfaces that are sharp, where their fragile bodies might get wounded.

This trick of navigating by steering was not new. Single-celled organisms like bacteria navigate around their environments in a similar way. When a protein receptor on the surface of a bacterium detects a stimulus like light, it can trigger a chemical process within the cell that changes the movement of the cell’s protein propellers, thereby causing it to change its direction. This is how single-celled organisms like bacteria swim toward food sources or away from dangerous chemicals. But this mechanism works only on the scale of individual cells, where simple protein propellers can successfully reorient the entire life-form. Steering in an organism that contains millions of cells required a whole new setup, one in which a stimulus activates circuits of neurons and the neurons activate muscle cells, causing specific turning movements. And so the breakthrough that came with the first brain was not steering per se, but steering on the scale of multicellular organisms.

Figure 2.7: Examples of steering decisions made by simple bilaterians like nematodes and flatworms.

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

The First Robot

In the 1980s and 1990s a schism emerged in the artificial intelligence community. On one side were those in the symbolic AI camp, who were focused on decomposing human intelligence into its constituent parts in an attempt to imbue AI systems with our most cherished skills: reasoning, language, problem solving, and logic. In opposition were those in the behavioral AI camp, led by the roboticist Rodney Brooks at MIT, who believed the symbolic approach was doomed to fail because “we will never understand how to decompose human level intelligence until we’ve had a lot of practice with simpler level intelligences.”

Brooks’s argument was partly based on evolution: it took billions of years before life could simply sense and respond to its environment; it took another five hundred million years of tinkering for brains to get good at motor skills and navigation; and only after all of this hard work did language and logic appear. To Brooks, compared to how long it took for sensing and moving to evolve, logic and language appeared in a blink of an eye. Thus he concluded that “language . . . and reason, are all pretty simple once the essence of being and reacting are available. That essence is the ability to move around in a dynamic environment, sensing the surroundings to a degree sufficient to achieve the necessary maintenance of life and reproduction. This part of intelligence is where evolution has concentrated its time—it is much harder.”

To Brooks, while humans “provided us with an existence proof of [human-level intelligence], we must be careful about what the lessons are to be gained from it.” To illustrate this, he offered a metaphor:

Suppose it is the 1890s. Artificial flight is the glamor subject in science, engineering, and venture capital circles. A bunch of [artificial flight] researchers are miraculously transported by a time machine to the 1990s for a few hours. They spend the whole time in the passenger cabin of a commercial passenger Boeing 747 on a medium duration flight. Returned to the 1890s they feel invigorated, knowing that [artificial flight] is possible on a grand scale. They immediately set to work duplicating what they have seen. They make great progress in designing pitched seats, double pane windows, and know that if only they can figure out those weird “plastics” they will have the grail within their grasp.

By trying to skip simple planes and directly build a 747, they risked completely misunderstanding the principles of how planes work (pitched seats, paned windows, and plastics are the wrong things to focus on). Brooks believed the exercise of trying to reverse-engineer the human brain suffered from this same problem. A better approach was to “incrementally build up the capabilities of intelligence systems, having complete systems at each step.” In other words, to start as evolution did, with simple brains, and add complexity from there.

Many do not agree with Brooks’s approach, but whether you agree with him or not, it was Rodney Brooks who, by any reasonable account, was the first to build a commercially successful domestic robot; it was Brooks who made the first small step toward Rosey. And this first step in the evolution of commercial robots has parallels to the first step in the evolution of brains. Brooks, too, started with steering.

In 1990, Brooks cofounded a robotics company named iRobot, and in 2002, he introduced the Roomba, a vacuum-cleaner robot. The Roomba was a robot that autonomously navigated around your house vacuuming the floor. It was an immediate hit; new models are still being produced today, and iRobot has sold over forty million units.

The first Roomba and the first bilaterians share a surprising number of properties. They both had extremely simple sensors—the first Roomba could detect only a handful of things, such as when it hit a wall and when it was close to its charging base. They both had simple brains—neither used the paltry sensory input they received to build a map of their environment or to recognize objects. They both were bilaterally symmetric—the Roomba’s wheels allowed it to go forward and backward only. To change directions, it had to turn in place and then resume its forward movement.

Figure 2.8: The Roomba. A vacuum-cleaning robot that navigated in a way similar to the first bilaterians.

Photograph by Larry D. Moore in 2006. Picture published on Wikipedia at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roomba.

The Roomba could clean all the nooks and crannies of your floor by simply moving around randomly, steering away from obstacles when it bumped into them, and steering toward its charging station when it was low on battery. Whenever the Roomba hit a wall, it would perform a random turn and try to move forward again. When it was low on battery, the Roomba searched for a signal from its charging station, and when it detected the signal, it simply turned in the direction where the signal was strongest, eventually making it back to its charging station.

The navigational strategies of the Roomba and first bilaterians were not identical. But it may not be a coincidence that the first successful domestic robot contained an intelligence not so unlike the intelligence of the first brains. Both used tricks that enabled them to navigate a complex world without actually understanding or modeling that world.

While others remained stuck in the lab working on million-dollar robots with eyes and touch and brains that attempted to compute complicated things like maps and movements, Brooks built the simplest possible robot, one that contained hardly any sensors and that computed barely anything at all. But the market, like evolution, rewards three things above all: things that are cheap, things that work, and things that are simple enough to be discovered in the first place.

While steering might not inspire the same awe as other intellectual feats, it was surely energetically cheap, it worked, and it was simple enough for evolutionary tinkering to stumble upon it. And so it was here where brains began.

Valence and the Inside of a Nematode’s Brain

Around the head of a nematode are sensory neurons, some of which respond to light, others to touch, and others to specific chemicals. For steering to work, early bilaterians needed to take each smell, touch, or other stimulus they detected and make a choice: Do I approach this thing, avoid this thing, or ignore this thing?

The breakthrough of steering required bilaterians to categorize the world into things to approach (“good things”) and things to avoid (“bad things”). Even a Roomba does this—obstacles are bad; charging station when low on battery is good. Earlier radially symmetric animals did not navigate, so they never had to categorize things in the world like this.

When animals categorize stimuli into good and bad, psychologists and neuroscientists say they are imbuing stimuli with valence. Valence is the goodness or badness of a stimulus. Valence isn’t about a moral judgment; it’s something far more primitive: whether an animal will respond to a stimulus by approaching it or avoiding it. The valence of a stimulus is, of course, not objective; a chemical, image, or temperature, on its own, has no goodness or badness. Instead, the valence of a stimulus is subjective, defined only by the brain’s evaluation of its goodness or badness.

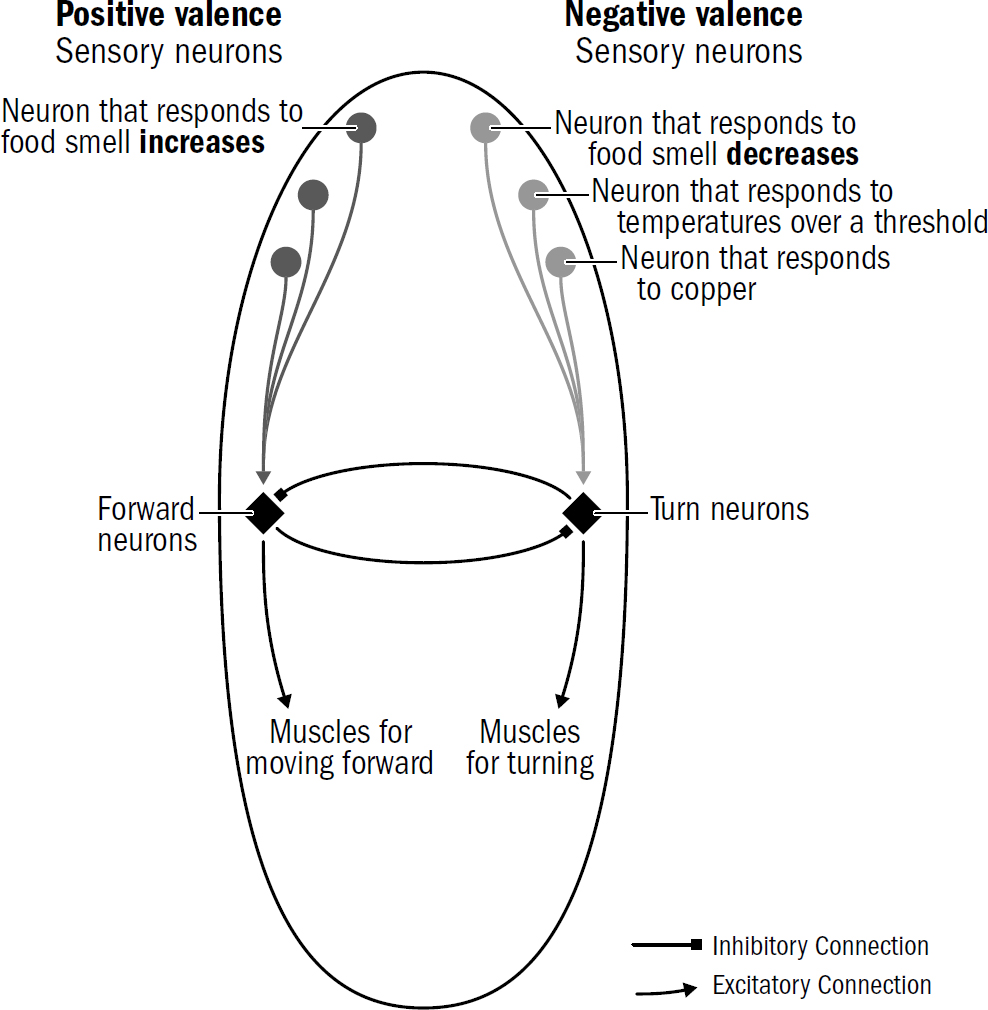

How does a nematode decide the valence of something it perceives? It doesn’t first observe something, ponder it, then decide its valence. Instead, the sensory neurons around its head directly signal the stimulus’s valence. One group of sensory neurons are, effectively, positive-valence neurons; they are directly activated by things nematodes deem good (such as food smells). Another group of sensory neurons are, effectively, negative-valence neurons; they are directly activated by things nematodes deem bad (such as high temperatures, predator smells, bright light).

In nematodes, sensory neurons don’t signal objective features of the surrounding world—they encode steering votes for how much a nematode wants to steer toward or away from something. In more complex bilaterians, such as humans, not all sensory machinery is like this—the neurons in your eyes detect features of images; the valence of the image is computed elsewhere. But it seems that the first brains began with sensory neurons that didn’t care to measure objective features of the world and instead cast the entirety of perception through the simple binary lens of valence.

Figure 2.9 shows a simplified diagram of how steering works in nematodes. Valence neurons trigger different turning decisions by connecting to different downstream neurons.

Consider how a nematode uses this circuit to find food. Nematodes have positive-valence neurons that trigger forward movement when the concentration of a food smell increases. As we saw in the sensory neurons in the nerve net of earlier animals, these neurons quickly adapt to baseline levels of smells. This enables these valence neurons to signal changes across a wide range of smell concentrations. These neurons will generate a similar number of spikes whether a smell concentration goes from two to four parts or from one hundred to two hundred parts. This enables valence neurons to keep nudging the nematode in the right direction. It is the signal for Yes, keep going! from the first whiff of a faraway food smell all the way to the food source.

Figure 2.9: A simplified schematic of the wiring of the first brain

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

This use of adaptation is an example of evolutionary innovations enabling future innovations. Steering toward food in early bilaterians was possible only because adaptation had already evolved in earlier radially symmetric animals. Without adaptation, valence neurons would be either too sensitive (and continuously misfire when smells are too close) or not sensitive enough (unable to detect faraway smells).

At this point, new navigational behaviors could emerge simply by modifying the conditions under which different valence neurons get excited. For example, consider how nematodes navigate toward optimal temperatures. Temperature navigation requires some additional cleverness relative to the simple steering toward smells: the decreasing concentration of a food smell is always bad, but the decreasing temperature of an environment is bad only if a nematode is already too cold. If a nematode is hot, then decreasing temperature is good. A warm bath is miserable in a scorching summer but heavenly in a cold winter. How did the first brains manage to treat temperature fluctuations differently depending on the context?

Nematodes have a negative-valence neuron that triggers turning when temperatures increase, but only if the temperature is already above a certain threshold; it is a Too hot! neuron. Nematodes also have a Too cold! neuron; it triggers turning when temperatures decrease, but only when temperatures are already below a certain threshold. Together, these two negative-valence neurons enable nematodes to quickly steer away from heat when they’re too hot and away from cold when they’re too cold. Deep in the human brain is an ancient structure called the hypothalamus that houses temperature-sensitive neurons that work in the same way.

The Problem of Trade-Offs

Steering in the presence of multiple stimuli presented a problem: What happens if different sensory cells vote for steering in opposite directions? What if a nematode smells both something yummy and something dangerous at the same time?

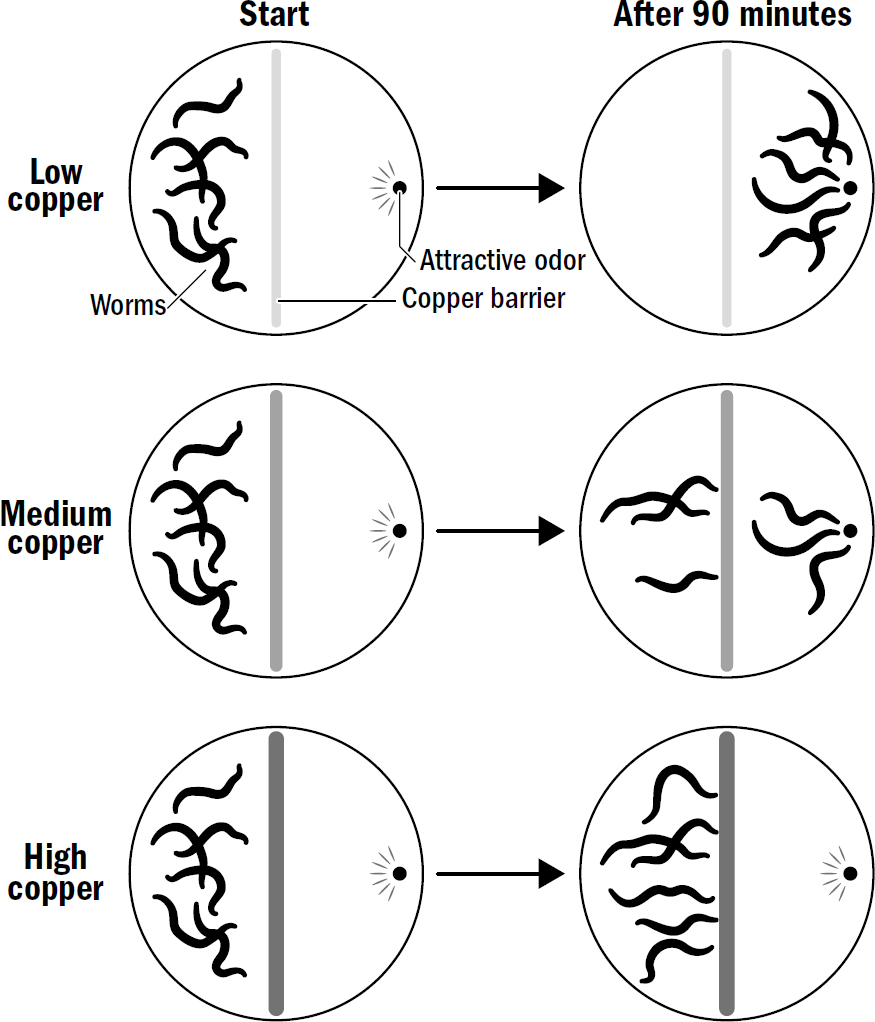

Scientists have tested nematodes in exactly such situations. Put a bunch of nematodes on one side of a petri dish and place yummy food on the opposite side of the petri dish, then place a dangerous copper barrier (nematodes hate copper) in the middle. Nematodes then have a problem: Are they willing to cross the barrier to get to the food? Impressively, the answer is—as you would expect from an animal with even an iota of smarts—it depends. It depends on the relative concentration of the food smell versus the copper smell.

At low levels of copper, most nematodes cross the barrier; at intermediate levels of copper, only some do; at high levels of copper, no nematodes are willing to cross the barrier.

This ability to make trade-offs in the decision making process has been tested across different species of simple wormlike bilaterians and across different sensory modalities. The results consistently show that even the simplest brains, those with less than a thousand neurons, can make these trade-offs.

Figure 2.10

Original art by Rebecca Gelernter

This requirement of integrating input across sensory modalities was likely one reason why steering required a brain and could not have been implemented in a distributed web of reflexes like those in a coral polyp. All these sensory inputs voting for steering in different directions had to be integrated together in a single place to make a single decision; you can go in only one direction at a time. The first brain was this mega-integration center—one big neural circuit in which steering directions were selected.

You can get an intuition for how this works from figure 2.9, which shows a simplified version of the nematode steering circuit. Positive-valence neurons connect to a neuron that triggers forward movement (what might be called a “forward neuron”), negative-valence neurons connect to a neuron that triggers turning (what might be called a “turning neuron”). The forward neuron accumulates votes for Keep going forward!, and the turning neuron accumulates votes for Turn away! The forward neuron and turn neurons mutually inhibit each other, enabling this network to integrate trade-offs and make a single choice—whichever neuron accumulates more votes wins and determines whether the animal will cross the copper barrier.

This is another example of how past innovations enabled future innovations. Just as a bilaterian cannot both go forward and turn at the same time, a coral polyp cannot both open and close its mouth at the same time. Inhibitory neurons evolved in earlier coral-like animals to enable these mutually exclusive reflexes to compete with each other so that only one reflex could be selected at a time; this same mechanism was repurposed in early bilaterians to enable them to make trade-offs in steering decisions. Instead of deciding whether to open or close one’s mouth, bilaterians used inhibitory neurons to decide whether to go forward or turn.

Are You Hungry?

The valence of something depends on an animal’s internal state. A nematode’s choice of whether to cross a copper barrier to get to food depends not only on the relative level of food smell and copper but also on how hungry a nematode is. It won’t cross the barrier to get to food if it is full, but it will if it is hungry. Further, nematodes can completely flip their preferences depending on how hungry they are. If a nematode is well fed, it will steer away from carbon dioxide; if hungry, it will steer toward it. Why? Carbon dioxide is a chemical that is released by both food and predators, so when a nematode is full, pursuing carbon dioxide for food isn’t worth the risk of predators; when it is hungry, however, the chance that the carbon dioxide is signaling food, not predators, makes it worth the risk.

The brain’s ability to rapidly flip the valence of a stimulus depending on internal states is ubiquitous. Compare the salivary ecstasy of the first bite of your favorite dinner after a long day of skipped meals to the bloated nausea of the last bite after eating yourself into a food coma. Within mere minutes, your favorite meal can transform from God’s gift to mankind to something you want nowhere near you.

The mechanisms by which this occurs are relatively simple and shared across bilaterians. Animal cells release specific chemicals—“full signals” such as insulin—in response to having a healthy amount of energy. And animal cells release a different set of chemicals—hunger signals—in response to having insufficient amounts of energy. Both signals diffuse throughout an animal’s body and provide a persistent global signal for an animal’s level of hunger. The sensory neurons of nematodes have receptors that detect the presence of these signals and change their responses accordingly. Positive valence food smell neurons in C. elegans become more responsive to food smells in the presence of hunger signals and less responsive in the presence of full signals.

Internal states are present in a Roomba as well. A Roomba will ignore the signal from its home base when it is fully charged. In this case, the signal from the home base can be said to have neutral valence. When the Roomba’s internal state changes to one where it is low on battery, the signal from home base shifts to having positive valence: the Roomba will no longer ignore the signal from its charging station and will steer toward it to replenish its battery.

Steering requires at least four things: a bilateral body plan for turning, valence neurons for detecting and categorizing stimuli into good and bad, a brain for integrating input into a single steering decision, and the ability to modulate valence based on internal states. But still, evolution continued tinkering. There is another trick that emerged in early bilaterian brains, a trick that further bolstered the effectiveness of steering. That trick was the early kernel of what we now call emotion.