Nonstate Sponsored Attacks

Stealing Information is Our Business… and Business is Good

Information in this chapter

Introduction

Symmetry is a curious thing. Symmetry traditionally refers to proportion. It signifies a degree of regularity, balance, and evenness. At its core, symmetry implies a state of being in equilibrium. On the contrary, asymmetry traditionally refers to the lack or absence of proportion. It signifies a measure of irregularity, imbalance, and unevenness. At its core, asymmetry implies the antithesis of symmetry. It points to a state of being that is devoid of equilibrium.

Asymmetric Forms of Information Gathering

Asymmetry is often viewed as a state of imperfection depending on the context in which it is being applied and defined. With respect to the world of cybercrime and espionage, asymmetry is the preferred state of being. Asymmetrical methodologies provide the elements necessary for ensuring the successful promotion, execution, and completion of their mission. It is paramount for cybercriminals, as well as state sponsored and subnational cyber actors, to recognize this. Failure to do so can adversely affect the ability of the cyber actor to complete his or her mission as it is defined.

As we progress through this chapter, we address many common techniques used today by cybercriminals and cyber espionage operators alike. In some instances, these parties and their activities are one and the same while in others they are quite different. We delve into the realm of the professional cyber operator: those parties who seek out and make their livings exercising their understanding of application architecture, network transmission protocols and their behavior, traditional and nontraditional malicious code and content exploits, vulnerabilities, and human weakness, which is perhaps the greatest vulnerability of them all. We discuss how, in addition to the professionals, amateur involvement is on the rise. Some of these amateurs are merely the equivalent of cyber tourists, while others are seeking to advance themselves, their skills, and agendas. We see how a defined lack of symmetry, in addition to mimicry of the appearance of perfect symmetry, plays a role within these areas, and in those to come. Asymmetrical forms of information gathering will become clear and, once identified, easily recognized by the trained eye.

Blended Reconnaissance

Reconnaissance can be performed in a number of ways. It can be conducted physically, taking into consideration the physical security attributes or characteristics of a given target or its personnel or it can be conducted logically, via the execution of targeted exercises and automated tools developed to aid in the detection, identification, and enumeration of hosts, systems, and networks reachable via Internet protocol communications. A savvy adversary will leverage these and other avenues such as social engineering to accomplish this mission. In either selecting targets for exploitation or defending them, it is important to note and understand the means by which reconnaissance is conducted and achieved. Reconnaissance as an operational task is paramount to the success or failure of all missions and classes of attack. From the most simplistic to those classes that are involved and comprise truly sophisticated multivector approaches, proper execution of reconnaissance activity cannot be ignored. In terms of the most sophisticated attack classes such as Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs), those attacks comprising advanced and normally clandestine means to gain continual, persistent intelligence on an individual or group of individuals such as a foreign nation state government, understanding the targeted information is as important as knowing which individuals can be targeted to source the data. The ability to map/discover the targeted infrastructure can be achieved using simple scans of known external access points of the network. However, the majority of technology used for this specific reconnaissance is noisy and typically detected by most IDS/IPS devices that are monitoring network traffic. Unfortunately, Google has opened up many avenues for collecting and performing reconnaissance without even sending a single packet to the targeted infrastructure.

Blending reconnaissance involves leveraging multiple public and private data stores to clearly determine who will become “patient zero,” the index or primary case as seen in epidemiological investigations for identifying the initial patient within a population during an epidemiological investigation.1 For aggressors, this is very important, as they will seek out the target(s) that offer the least resistance and greatest degree of opportunity for initial exploitation.

Single-threaded data sets alone provide value; however, a correlated reconnaissance view, with information gained from a variety of sources, paints a crisp picture of the said targets and the infrastructures and ecosystems to which they belong. Whether you or your organizations are aware, your adversaries (cybercriminals, state sponsored adversaries, subnationally sponsored cyber actors, etc.) clearly understand the value of your data. As a result, it should come as no surprise that these parties would consider intermittent disruption of service or total denial of service as being viable.

Before we discuss the methods employed by these parties in addition to reconnaissance, let us first define some key areas of interest to them. The following is representative of a number of areas of interest to these adversaries; however, it does not address all areas in all use cases. It is important to note first the goal in gaining access to data (regardless of their owner) that are deemed sensitive by one party and protected from all unauthorized parties. Most information sought out by adversaries active in the cyber realm (cybercriminals, state sponsored, or subnationally sponsored actors) provides economic, industrial, military, and/or foreign intelligence advantages.

For example, merger and acquisition strategies, intellectual property, military strategies, and unclassified information in aggregate form can be deemed sensitive financial information; research and prototype information are a few examples of data sets that are typically sought after as they provide the most value and competitive advantages. No discussion regarding professional grade thievery or spying can begin without first addressing the concepts of reconnaissance and blended reconnaissance. Reconnaissance, as we discuss in more detail in Chapters 6 and 9, can be simply defined as the act of scouting and surveying in a covert manner to achieve a degree or level of knowledge via inspection, exploration, and investigation.

Social Engineering and Social Networking

Social engineering is just as effective in gathering information today as it was decades ago. There are many examples that describe in great detail just how easy it is to ascertain information from someone. Social engineering is the ability to collect sensitive information from individuals without their being aware that they are giving away the keys to the kingdom. Social engineering can take be summed up in six categories:

1. Pretexting: This is tricking the target into believing that you are something you are not. Typically, this could take the form of attacking or impersonating a colleague in the company you are trying to gain information from or even other forms of impersonating such as saying you are an investigator, law enforcement officer, auditor, IT security, and so on, the point being to take on the right persona to achieve your collection goal.

2. Diverson theft: This is the ability to con the delivery of goods to be dropped off at a location that is in close proximity to the intended location to intercept the goods. This is not very typical in terms of cyber theft and leaves a high probability of the actors involved getting caught.

3. Phish: This is a vector in which someone crafts an email that looks legitimate to trick an unsuspecting user into downloading malicious code and content onto their computer to collect information about the target. When this form of phishing came out, the probability of someone falling for it was alarming. Today, the attackers have become cleverer in terms of enticing you to click on a link. The following example was taken from Chase.

Your online Banking account needs Verification for security purpose, click on the verification link for you to continue on your online banking

This message has been sent to all Chase customers

Chase Bank Security Department

Note: failure to do so will lead to the suspension of your account

Please do not reply to this mail. Any message sent will not be answered2

4. Phone phishing: Phone phishing typically ties into email phishing by prompting the target to call a specific phone number regarding his or her account. Once the target calls the number, he or she will be prompted to enter account information and personal identification information. Additionally, phone phishing could be by someone pretending that he or she is from the organization you do business with, or even work for, to ascertain information.

5. Baiting: This is used often and is very common among trade shows. The premise here is that someone will load malware on a USB stick with a legitimate corporate logo and leave it hoping someone will insert it in his or her computer, thus executing the malware. The majority of baiting is intentional, but in early 2010 at AusCert, one of the largest security conferences in the Asia Pacific, IBM was giving out USB keys that contained malware. In this case, the malware was supply chained injected without IBM’s knowledge. Once this was discovered, every attendee of the conference was notified and given instructions on how to remove the malware. Case in point: do not use USBs that are given to you at a conference unless you are absolutely sure that they are clean. This was unfortunate for IBM, but this can happen to anyone.

6. Quid pro quo: This one takes many forms, and one of the most famous use cases was an IT security organization that sent out a survey in which users supplied their passwords in exchange for a small interoffice gift. Another way quid pro quo works is calling users claiming that you are IT and calling back on an IT issue. Let us face it, if you are dialing into a large company, you are bound to find someone with an IT issue, and by using virtual pretexting techniques, you could end up with all the information that you are looking for.

Additionally, social engineering is extremely effective in terms of industrial and government espionage. Understanding of your target’s weakness and habits can be used as bait in harnessing just about any information you are looking to capture. To give you a little more context, let us take Kevin Mitnik as an example. Mr. Mitnick went down in history as one of the most well-known computer hacker icons in the world. Mr. Mitnick was very intelligent and had a strong academic and practical understanding of a variety of vulnerabilities that allowed him access to sensitive information. He also understood the susceptibility to exploitation that exists in human beings. Given this, he exercised his knowledge of both systems and human vulnerabilities to capitalize and ultimately profit from the weakness of others. Additionally, Mr. Mitnick had a strong fluency in social engineering techniques and practicum. Through this knowledge, he was able to obtain the information necessary to access facilities and systems belonging to a host of organizations and individuals including the system of the man who eventually aided in bringing him down, Mr. Tsutomu Shimomura.3

We cite this case because what Mr. Mitnick did almost two decades ago is still relevant today.

The exploitation of social networking technology and environments exemplifies this. It is a new advent in social engineering. Social networking falls squarely into the danger zone that allows for events such as those described by Goethe in Faust to occur. There is no privacy in social networking environments and any attempt at providing it is simply an illusion set in place to appease legal counsel and watchdog organizations. The reality is that anything placed on a publicly available server is not private and as such potential fodder for exploitation. The following is a quick blurb from Facebook and Twitter’s EULA.

Facebook: Privacy

“Your privacy is very important to us. We designed our Privacy Policy to make important disclosures about how you can use Facebook to share with others and how we collect and can use your content and information. We encourage you to read the Privacy Policy, and to use it to help make informed decisions.

Sharing Your Content and Information. You own all of the content and information you post on Facebook, and you can control how it is shared through your privacy and application settings. In addition:

1. For content that is covered by intellectual property rights, such as photos and videos (“IP content”), you specifically give us the following permission, subject to your privacy and application settings: you grant us a nonexclusive, transferable, sublicensable, royalty-free, worldwide license to use any IP content that you post on or in connection with Facebook (“IP License”). This IP License ends when you delete your IP content or your account unless your content has been shared with others, and they have not deleted it.

2. When you delete IP content, it is deleted in a manner similar to emptying the recycle bin on a computer. However, you understand that removed content may persist in backup copies for a reasonable period of time (but will not be available to others).

3. When you use an application, your content and information is shared with the application. We require applications to respect your privacy, and your agreement with that application will control how the application can use, store, and transfer that content and information. (To learn more about Platform, read our Privacy Policy and About Platform page.)

4. When you publish content or information using the “everyone” setting, it means that you are allowing everyone, including people off of Facebook, to access and use that information, and to associate it with you (i.e., your name and profile picture).

5. We always appreciate your feedback or other suggestions about Facebook, but you understand that we may use them without any obligation to compensate you for them (just as you have no obligation to offer them).”4

Twitter: Your Rights

“You retain your rights to any Content you submit, post, or display on or through the Services. By submitting, posting, or displaying Content on or through the Services, you grant us a worldwide, nonexclusive, royalty-free license (with the right to sublicense) to use, copy, reproduce, process, adapt, modify, publish, transmit, display and distribute such Content in any and all media or distribution methods (now known or later developed).”5

The common theme of both these terms is that Facebook and Twitter own the rights to any content you publish for their use. Let us not forget that anyone else with the right privileges can read and download any content you post and potentially take advantage of those data to conduct reconnaissance and exploitation on you, your employer, or any number of targets. The amount of information that can be acquired from social networking sites and used for reconnaissance purposes is endless. From a targeting perspective, Facebook can be used to establish your social habits, likes, and dislikes. All of these may be used by a party with nefarious intent bent on profiting or completing a mission with your data in tow. With the recent addition of geographic location information (incorporation of geographic information systems intelligence in modern Internet-enabled applications), it is easy to establish in what locations you work and play. All this information can be used in determining the approach one could use in gathering information.6

In a sanctioned penetration test, a security research firm Meta-Guard was able to penetrate a power company by using Facebook. On completion of their research, the researchers at Meta-Guard found that over 900 employees were using Facebook. As a result, they were able to create a fake persona of an attractive female employee. Over time, they were able to befriend many of the company’s employees. As part of their penetration testing, the team was able to find a cross-site scripting vulnerability in the company’s Web server. Once they were assured the fake persona was working, they posted a rogue link to Facebook indicating that there was an issue with the company’s Web server. Many individuals who were friends with the fake persona actually clicked on the link, and the security research firm was able to harvest user credentials, giving them access to very sensitive data stores.

This is a prime example of how social networking can be used to collect and launch various attacks. The rapid adoption and use of social networking has exploded in terms of the number of people who utilize social networking on a daily basis. For example, Facebook currently touts as follows:

• More than 500 million active users

• 50% of our active users log on to Facebook in any given day

• Average user has 130 friends

• People spend over 700 billion minutes per month on Facebook

As a result of the advent of blended social networking connections becoming the norm, the likelihood of greater degrees of compromise and exploitation has increased significantly.

Blended connections are quite common and expected in applications such as LinkedIn7 or comparable sites, for example. This has led to what we call connection sprawl. In most cases, individuals want high numbers in terms of friends and connections, so that they can capitalize in one way or another. The idea of “staying connected” is an attractive one to users and adversaries alike.

Point, Click, and Own

Cybercriminals and actors are in a position of strength in many respects today because of the rapid adoption of next generation technology. The lemming-like willingness to adopt these technologies at any cost to achieve a higher degree of social acceptability has acted as an invitation to those with nefarious intent bent on profiting, regardless of the cost, or the pain and suffering of others.

In some respects, this is an obvious ailment of the social condition known as social networking. Cybercriminals are empowered and in a position today to gather voluminous amounts of intelligence about their targets and subsequently execute their plans. This has become less trivial over time especially when we consider the rapid adoption of technologies that promote dynamicism over security such as those affiliated with Web 2.0.

The Internet has made us more dependent on these technologies and by proxy on the security we believe to be inherent within them than ever before. We rely on Web browsers, email clients, word processors, and PDF viewers to name a few for work and pleasure. They are inextricable aspects of our existence. To do business today, enterprises must allow for Web, Mail (SMTP, POP3, IMAP, etc.), and DNS traffic in addition to other nontraditional enterprise applications.

From a security point of view any connection established internally to the Internet is implicitly trusted by the firewall. Typically, a traditional legacy firewall is useless in providing deep packet inspection and/or access control of egress traffic. From a hacker’s point of view, the return on investment in trying to bypass a firewall from the outside is extremely low. This brings us to the big shift in the paradigm. Today, hackers are utilizing common vulnerabilities within Web browsers and Web servers to deliver very sophisticated attacks in addition to phishing and spear phishing attacks. As a result, the following sections will be of interest to those tasked with securing enterprises against next-generation adversaries and aggressors.

Phishing: While we mentioned different forms of social engineering, we briefly discussed the use of phishing. In terms of the attack vector being used, it can range from an unsolicited email to an official email that appears to have come from your company or the company you do business with, shortened URL in Twitter, or embedded email that can be found in various social networking sites. The biggest angle here is to entice you to click on a link.

The range of sophistication involved in phishing really depends on the target. Common phishing attempts are quite clever, such as the one listed at the beginning of the chapter regarding Chase. Those who are not security savvy and are new to online banking might fall for clicking on the link. This can become more devastating if the user clicks on the link at work. Clicking a phishing link period is bad but in reality if this happens at home the amount of information taken is less and the damage is isolated.

If you are a corporate executive, researching, or in an administrative role, doing this at work not only opens you up to risk but also the entire corporation. Most of the phishing attempts can be combated with educating the end user on clicking embedded links within corporate email. In late 2009, it was reported that Exxon Mobil was targeted with a phishing email labeled “Emergency Economic Stabilization Act”8 with an embedded link.

Unfortunately, in this case, users actually clicked on the link, which introduced malware that transmitted sensitive information outside the corporate infrastructure. In this case, the attacker used an email that appeared to be a reply to an originating email. What is important to note is that any phishing email is harmless unless someone clicks on the link. The damage is really invoked by whatever vulnerability or exploit the attacker is trying to use.

Let us take Koobface for example. Although this attack was not that sophisticated in terms of the message the attacker used, it utilized social networking as the transport to bait the user to click on a link. The following is a quick analysis of Koobface:

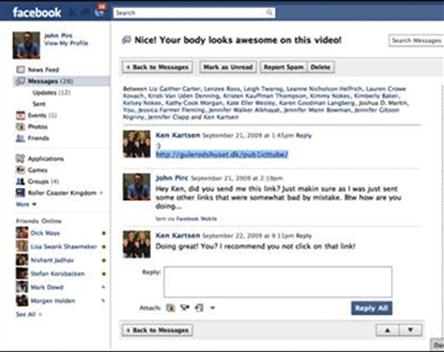

In this use case, we were sent a Facebook mail from a trusted friend with the subject “Nice! Your body looks awesome on this video” as shown in Figure 5.1.

Figure 5.1 Koobface worm example.

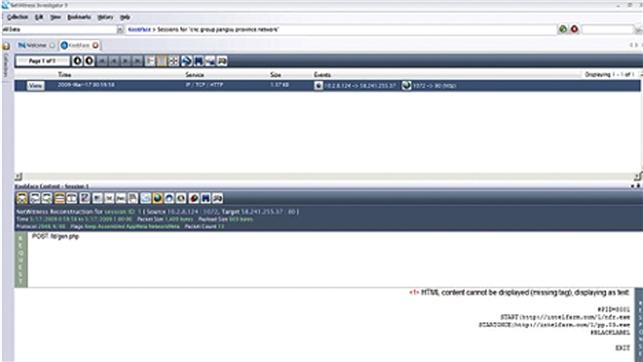

In this specific example, once the user clicks on the embedded link they are redirected to another site that tries to download executables. In this case, the malicious executables take the form of codec updates that seem convincing enough to allow the update. After the malware is executed, it will redirect the users to sites that host malware. This provides the attacker an à la carte of vulnerabilities to use on the target. However, phishing requires someone to participate in the attack (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2 Analysis of Koobface email with NetWitness investigator.

Another common method used in gaining access is called drive-by malware. One of the main reasons why drive-by malware is so effective is the way the attack is delivered. This involves the attacker taking over a legitimate Website and embedding specific calls that will redirect your browser to another Website without your knowledge. Typically, the redirected Website contains exploit code that can be run against your Web browser until the attacker finds vulnerability. Once he or she finds the vulnerability, he or she can load just about anything on the end point to harness user credentials, confidential information, and so on.

In the case of drive-by malware, we discuss iFrame injection. Frames have become a viable means of deploying malicious code and content on unsuspecting Web surfers the world over. iFrames are browser features that allow Websites to deliver content from remote Web sites within a frame on a page. This can manifest in a variety of ways on the site hosting the embedded malware. Cybercriminals exploit the feature of modern Web browser design by building iFrames into pages that are typically quite small. In some cases, iFrames have been reported as small as one pixel by one pixel! An iFrame of this size would be invisible to the naked eye of the casual Web surfer and thus not detected until it was too late, if ever. Within an iFrame, cybercriminals can store a cache of malicious code, typically a downloader program of some sort. In most instances, these downloader programs are in reality a single redirect instruction set in motion by events such as the following:

• A user surfs onto an iFramed Website.

• The downloader program is delivered from within the invisible iFrame.

• The browser on the user’s PC is then told by the downloader program to visit the site or IP address contained within the redirect instruction set.

• The site or IP address may contain another downloader program which then initiates ad infinitum.

• The user’s PC is thereby exploited, compromised, and owned by the parties responsible for the iFrame.

iFrames are a lucrative business within the subeconomic ecosystem of the Internet. Business models vary although in many cases they are quite simple in that those who host the iFrames on behalf of the cybercriminal actors are paid via clicks received. Payments are made in a variety of ways and have emerged over time in a variety of legitimate (e.g., PayPal and Western Union) and illegitimate (e.g., e-gold) ways. Rates vary and have been noted to be as low as 5–60 USD with minimum schedules being agreed to for payment (minimums referring to minimum number of clicks expected and/or guaranteed by the hosting party). Some hosting environments will even provide a new customer with the malicious code and content (e.g., binaries and executables), should they not own their own.

A full service business model can be ready to be rolled out to serve a growing customer demand. Profit is predicated off the number of domains owned by a provider and their drive to profit from their infrastructure. In addition to these illegitimate Websites, iFrames are also injected into legitimate sites (e.g., sites with good or benign Internet reputations). According to Kaspersky’s 2009 Security Bulletin, under “statistics,” iFrame exploits accounted for 1.27% of the total attacks they saw globally out of 27,443,757 identified incidents.9 Although this may not seem like a staggering number, when viewed in terms of the totality of cybercriminal activity this is a tremendously high number. Furthermore, it is one that shows no signs of slowing because of the ease of use, dissemination, and exploitation.

Other common redirects such as cross-site scripting (also known as XSS) occur when Web applications gather malicious data from a user. This may seem like a foreign concept (a Website or Web application gaining malicious code and content from a user), but it happens. The malicious code and content are usually collected via a form or a hyperlink that contains malicious content itself. A user will generally click on a link or URL from another Website, an instant message, while visiting Web forums or checking email. Cybercriminals will typically encode the malicious payload of the link to the site in hexadecimal format or some other comparable coding method so that the request does not evoke suspicion on the part of the end user as he or she attempts to click on it.10

After the data have been collected by the Web application in question, it creates an output page for the user. This page generally contains the malicious data that were originally sent to it, although in a manner that gives the appearance that the data in question are valid content from the Website. Many Web-based applications today such as guestbook, forums, and other applications that support http, write actions in html along with embedded JavaScript. Attackers will often inject JavaScript, VBScript, ActiveX, HTML, or Flash into a vulnerable application to catch a user unaware. This often results in session or account hijacking, unauthorized manipulation of user settings, cookie theft and/or poisoning, or other illicit activities. Cross-site scripting experiences resurgences in popularity and as a result of Website and Web application weakness/vulnerability enjoys a position of prominence within the top five Internet-based attacks second only to SQL injection attacks.11

In this chapter, we have discussed some very effective avenues that attackers use to gain access to data of a variety of types, most of the time in perfect stealth. Asymmetric information gathering is as difficult to combat as asymmetric warfare. Though unconventional, it is quite effective and as such something to be wary of. Search engine providers never intended for their data stores to be used as a tool for caching, indexing, and analyzing data by cybercriminals and actors as a form of subversive information gathering. We have touched on the use of social engineering and social networking discussing the most common forms of use for harvesting and exploiting sensitive data. Additionally, we have reiterated the relevance of social engineering in today’s world for information and intelligence acquisition by cybercriminals, state sponsored cyber actors, and subnational cyber actors alike. It is our belief that this trend will continue and encourage additional instances of occurrence as time, availability, and technology become more available.

Summary

In this chapter, we looked at different forms of information gathering and details germane to their success. Additionally, we dove into asymmetric information gathering by exploring multiple ways a cyber actor collects information from a source with the intent to use those data to further his or her ends. Lastly, we discussed the various technical exploitation methods that are used to go after the data, which leverage social engineering and social networking.

References

1. Incompatible Browser | Facebook. Retrieved August 31, 2010, from www.facebook.com/terms.php?ref = pf; 2010.

2. Mackenzie K. Cyber attacks on oil majors FT.com. Retrieved August 31, 2010, from http://blogs.ft.com/energy-source/2010/01/26/cyber-attacks-on-oil-majors/; 2010.

3. Online Fraud. Chase Bank 2010; Retrieved August 31, 2010, from www.chase.com/index.jsp?pg_name=ccpmapp/privacy_security/fraud/page/fraud_examples; 2010.

4. Prince B. Using Facebook to social engineer your way around security eWeek. Retrieved August 31, 2010, from www.eweek.com/c/a/Security/Social-Engineering-Your-Way-Around-Security-With-Facebook-277803/; 2009.

5. Twitter Terms of Service. Twitter. Retrieved August 31, 2010, from http://twitter.com/tos; 2010.

1 http://news.techworld.com/security/113086/researchers-trawl-for-confickers-patient-zero/; http://wordnetweb.princeton.edu/perl/webwn?s=index%20case

2 https://www.chase.com/index.jsp?pg_name1/4ccpmapp/privacy_security/fraud/page/fraud_examples

3 www.takedown.com/bio/tsutomu.html

4 http://www.facebook.com/terms.php?ref1/4pf

6 www.eweek.com/c/a/Security/Social-Engineering-Your-Way-Around-Security-With-Facebook-277803/

8 http://blogs.ft.com/energy-source/2010/01/26/cyber-attacks-on-oil-majors/

9 www.securelist.com/en/analysis/204792101/Kaspersky_Security_Bulletin_2009_Statistics_2009