CHAPTER 1

Old Norse cosmology as an archaeological challenge

Young were the years when Ymir made his settlement,

there was no sand nor sea nor cool waves;

earth was nowhere nor the sky above,

chaos yawned, grass was there nowhere.

This is the famous description near the beginning of the Icelandic Eddic poem Vǫluspá (The Seeress’s Prophecy) of the empty void before the creation of an ordered world. The following stanzas tell how the gods gave everything in the world its name and right place, how they built ritual sites and made precious objects, and how they blew life into the first humans from two pieces of wood. After descriptions of the world tree and the first war between the two families of gods, the Æsir and the Vanir, the poem ends with the death of the god Baldr and the destruction of the world, Ragnarok (Ragnarǫk), literally ‘the destiny of the gods’. However, the poem states that after Ragnarok a new ‘eternally green’ world will come from the sea, and in the grass the children of the old Æsir gods will find ‘the wonderful golden chequers, those which they possessed in the ancient times’ (Vǫluspá 59, 61).

The ordered world in Vǫluspá was usually called Midgard (Miðgarðr), meaning ‘dwelling place in the middle’ (Simek 1993:214). This concept was known not only in Iceland, where Vǫluspá was composed probably in the eleventh century (McKinnell 2008), but also in other areas of the Germanic-speaking world. As early as AD 370, in Bishop Wulfila’s Gothic translation of the Bible, the same concept is rendered as midjungards. Other later but similar forms are known from Saxon, Old English, and Old High German. In Scandinavia, the earliest reference to Midgard comes from a runic inscription on a boulder at Fyrby in Södermanland in central Sweden, dated to the early eleventh century (de Vries 1957:372–3; Vikstrand 2006). An alternative name for the world, Jormungrund (Jǫrmungrundr) meaning ‘mighty ground’, also existed. It is recorded in Grímnismál 20, but also in Beowulf 859 and on the famous rune stone at Karlevi on Öland in eastern Sweden (Fig. 1) from about the year 1000 (Simek 1993:180).

Today, notions of an ordered universe are usually framed by the concept ‘cosmology’. The word, meaning ‘knowledge of good order’, was first coined by the German Enlightenment philosopher Christian Wolff (1679–1754) in his Cosmologia Generalis from 1731. Since then, the word has been given many different uses and meanings. One of the modern uses of the word is anthropological, being a general concept of different culturally constructed worldviews. Cosmology in this sense usually includes fundamental notions regarding time and space, the structure of the universe, the creation of the world, borders between supernatural powers and humans, origins of social groups, divisions between men and women, fate and death, ethics, and the criteria of truth. In several cultures, these different cosmological aspects are linked to one another in a cosmological system, as in the case of the Chinese principles of yin and yang (for example Douglas 1966; Geertz 1973; Clunies Ross 1994:42 ff.; Raudvere 2004).

Cosmology is accordingly a modern concept, like the concept of religion itself. Both words are modern attempts to define certain aspects of human action and human thought in time and space. Cosmology is not necessarily connected to religion, but in most pre-modern societies religious myths provided answers to many of the fundamental cosmological questions. A coherent worldview is seldom presented in these myths, and should not be expected, since cosmology is a modern concept. However, some general principles can often be deduced from the narratives (Raudvere 2004).

Cosmology can also be connected to rituals, since ritual sites and monuments in many cultures seem to have been modelled in accordance with aspects of different worldviews (Widengren 1969:340 ff.; Sundqvist 2004). In that sense, cosmology is a concept situated between the concepts of myth and ritual, since it can be connected to both. This conceptual location of cosmology is important, especially in current reconsiderations of ritual, myth, and religion.

Previously, myths were regarded as the core of religion, whereas rituals were often perceived as passive expressions of myths and actions designed to maintain a cosmological order (Eliade 1958). In recent decades, however, these perspectives have been challenged in anthropological criticism of the implicit Judeo-Christian background of many religious studies (Smith 1987; Asad 1993; Bell 1992; Humphrey and Laidlaw 1994; Rappaport 1999; Habbe 2005). Religion is no longer defined as theology, but is viewed much more as changing social practice, associated with a religious transcendental discourse. Myth and ritual are understood as two different but interrelated social categories. As a consequence, ritual is not necessarily regarded as a representation of myth, but can be apprehended as a formalized act that in itself creates meaning. Instead of merely maintaining a cosmological order, ritual is also seen as a transformative act. Besides, ritual is not regarded as necessarily religious, since it can refer to other – legal, political, and social – discourses (Nilsson Stutz 2003; Habbe 2005). Myth, meanwhile is still regarded as an important narrative, but in recent years above all its social functions have been underlined (Meulengracht Sørensen 1993; Clunies Ross 1994; Lindow 1997a).

Nonetheless, in those cases where ritual and myth can be related, cosmology may still play an important intermediate role. Cosmology is never limited to a single medium, but is usually played out in different myths as well as in ritual sites. This interface does not necessarily lead in a single direction. Ritual sites might be expressions of cosmological ideas, but it is also possible that the sites and monuments themselves created and reinforced cosmological notions. For example, the divine abodes of Old Norse gods and goddesses were expressed through, but also modelled on, the large halls that the political elite in Scandinavia used in the Iron Age (Hedeager 2011:148 ff.).

Still, since current ritual theory is above all based on the theory of practice (see Bourdieu 1990), questions concerning the history and meaning of rituals in long-term perspectives are to a large extent lacking in today’s debate. Similarly, it is noteworthy that material culture plays a minor role in much current ritual theory, since objects are conceived of as symbols in a traditional semiotic, sense. This means that objects are viewed as ‘empty symbols’, without any fundamental importance for the understanding of religion (Kyriakidis 2007). However, in recent religious studies inspired by cognitive science, material culture has been fully incorporated into investigations of religion. A good example is the work of Johan Modée, who underlines the fundamental role of objects, buildings, and places in religion. According to Modée (2005), without them, religion is not conceivable and would not exist as a social practice.

Cosmological aspects of Old Norse religion

Old Norse religion is the conventional name for religious traditions in Scandinavia before the conversion to Christianity in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Pre-Christian religion in Scandinavia was above all based on ritual practice and oral traditions, although runic writing has been used in northern Europe since about AD 200. This means that almost all written accounts of these religious traditions are external, written either by Christians referring back to their pagan past or by foreigners from ethnographical perspectives.

Most written accounts of Old Norse religion come from the rich and varied medieval Icelandic literature. The mythological world is summarized and explained in Snorri’s Edda, a poetic manual written by the Icelandic chieftain and skald (poet) Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241) in the early thirteenth century. He based his knowledge on a large corpus of skaldic poems, some lost, some preserved in fragments, and some extant in their full length. The most important surviving mythological and heroic poems are collected in the Poetic Edda, which was written down and edited in the early thirteenth century, although some of the poems were composed earlier. Besides, references are repeatedly made to the pagan past in many of the Icelandic sagas from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Apart from the Icelandic literature, the Danish scribe and historian Saxo Grammaticus wrote extensively about Scandinavia’s pagan past in his Danish history (Gesta Danorum) from the early thirteenth century. Descriptions of Scandinavian ritual practice are also known from accounts by the Arabic diplomat and geographer Ibn Fadlan (922) and by three German clerics and historians, Rimbert (c.870), Thietmar of Merseburg (c.1010) and Adam of Bremen (c.1075). Besides, the Old English poem Beowulf (probably tenth or eleventh century) includes references to worldviews in ancient Scandinavia. Cosmological ideas, of more or less clear pre-Christian origin, are scattered across many of these texts. Above all the Poetic Edda and Snorri’s Edda, but also skaldic poetry, contain descriptions and words connected to past worldviews.

Figure 2. A reconstruction of the Old Norse worldview with nine worlds. (After Magnusen 1825, photo by Jens Östman, Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm.)

Many aspects of Old Norse religion that can be covered by the modern concept of cosmology have been studied. A major field of research concerns the basic construction of the world. Most scholars have underlined the fragmentary, contradictory, and ambiguous notions of the pagan worldview in extant sources (Gurevich 1969; Hastrup 1985; Davidson 1988:167 ff.; Schjødt 1990; Clunies Ross 1994:42 ff., 2011; Brink 2004; Wellendorf 2006). The scattered nature of the evidence has been explained at least partly in terms of oral culture, which is usually characterized by regional and social variations. Nonetheless, much effort has also been put into understanding the basic structures that appear to lie behind these scattered remains. Some scholars have tried to harmonize what is known into more coherent images (Fig. 2), whereas others have tried to discern the different historical or regional horizons that may be detected in the sources.

The ritual aspects of Old Norse cosmology have been another main field of research. Place-name scholars have been able to show how the abodes of deities were present in the human world in the form of ritual sites with sacral place-names linking them with specific gods or goddesses. In some cases, such as the island of Selaö in central Sweden, practically the whole divine universe was present in a specific small area (Brink 2001, 2004; Vikstrand 2001, 2004). Other ritual aspects are reflected in the cosmological structure of the religious and political centres of the Iron Age, the so-called central places. Elements in the early descriptions of Gamla Uppsala have long since been considered to be expressions of central cosmological ideas, especially the references to a well, a tree, and a hall. Similar discussions have also been connected to Helgö, Gudme, and lately other central places (Widengren 1969:340 ff.; Alkarp 1997; Andrén 1998b:148; Hedeager 2001; Gunnell 2001; Sundqvist 2004; Zachrisson 2004b, 2004c).

Human and social aspects of Old Norse cosmology have also been studied. Above all, cultural models including issues such as the idea of society, the origins of humans, honour, ethics, healing, food, and the relation between humans and animals have been investigated (Dumézil 1973; Meulengracht Sørensen 1993; Clunies Ross 1994; Hedeager 1997, 2004, 2011; Jennbert 2004, 2011; Solli 2004).

The chronological and spatial horizons of Old Norse cosmology

Although the Old Icelandic texts have been used for a long time in studies of early Scandinavian worldviews, some fundamental methodological issues are raised by the nature of the rich and highly varied literature from Iceland. The texts are medieval Christian literature, and show how authors in thirteenth-century Iceland interpreted the pre-Christian oral culture of Iceland and Scandinavia. A basic question is therefore how we should view the relationship between the narratives, the authors’ society in the thirteenth century and later, and the pre-Christian society in which most of the narratives are placed retrospectively (see Meulengracht Sørensen 1977; Habbe 2005). Do these texts merely present a ‘fantasy religion’, created by classically learned authors in a diaspora culture who were looking back to an imagined homeland, or do the Icelandic stories contain elements based on social practices and worldviews that existed in a pagan past? Due to the multidisciplinary character of Old Norse studies, the answers to these questions vary quite considerably.

Today, most philologists, historians, and literary scholars underline the medieval Christian character of Old Icelandic literature, partly as a reaction against earlier views that tended to take the literature as representations of pagan customs and beliefs. The main arguments against using the texts in reconstructions of a pagan past are the many similarities between the Icelandic texts and contemporary Christian narratives, as well as the distance in time and space between medieval Iceland and prehistoric Scandinavia (Lönnroth 1965; Olsen 1966; Meulengracht Sørensen 1977; Clover and Lindow 1985; Düwel 1985; Krag 1991; Clunies Ross 1994, 1998). Consequently, this position has led scholars away from discussions of the pagan past to other interesting studies in which medieval Icelandic culture and literature have a value in their own right (for instance, Meulengracht Sørensen 1993; Clunies Ross 1994; Lassen 2011).

In contrast, many historians of religion and place-name scholars still emphasize the common non-Christian traits of many elements in the Icelandic texts (Steinsland 1991, 2005; Schjødt 1999a, 2009; Näsström 2001a; Sundqvist 2002; Brink 2004). Although these scholars acknowledge the huge source-critical problems involved, they nonetheless try to reconstruct a pagan past by comparing elements in the Icelandic texts with other kinds of evidence. This strategy includes comparisons with older descriptions of the Germanic peoples or Scandinavians in Roman, German, and Arabic sources, older runic inscriptions from Scandinavia, the etymology of various words, comparisons with other non-Christian Indo-European religions, and sometimes references to the phenomenology of religion. These comparisons show that many details in the Icelandic texts appear to have some relation to a pre-Christian past.

Nevertheless, these comparative methods pose problems of their own. The chronologically and geographically scattered statements given in earlier texts about Germanic tribes and Nordic peoples and their customs are sometimes too easily combined into a homogenized picture of their religious traditions. Since the comparisons are drawn from many different sources, periods, and places, the image of Old Norse religion often tends to be set outside time and space. Possible changes over time as well as regional variations have often been lacking in comparative accounts (see, however, McKinnell 1994; DuBois 1999; Brink 2007; Schjødt 2009; Andrén 2012; Nordberg 2012; Gunnell forthcoming).

The methodological issues are especially problematic in Georges Dumézil’s influential reconstruction of Indo-European mythology. Old Norse religion plays an important role in his work, since Dumézil assumes that Old Norse religion represents an archaic and unchanged religious tradition on the periphery of Europe (Dumézil 1958, 1973). His position has been criticized by many (Renfrew 1987; Drobin 1989; Clunies Ross 1994), and, from an archaeological perspective, the assumption of an unchanged periphery is hard to reconcile with the fact that Scandinavia was constantly interacting with other parts of Europe throughout prehistory. Besides, Dumézil’s tripartite mythology is too simple to correspond to the complex grammatical structure that is found in Indo-European comparative linguistics. Although Dumézil connects the mythology with the social structure, his reconstruction remains outside time and space. Due to their general character, his ideas can in a sense be applied everywhere and nowhere.

Furthermore, the methods used in historical linguistics mean that linguistic proximity is emphasized at the expense of geographical proximity. Various Indo-European languages have been drawn into the argument as self-evident points of reference in studies of pre-Christian Norse religion, regardless of the geographical location of the languages (Dumézil 1973; de Vries 1956, 1957). At the same time, nearby Sámi and Finnish areas have often been ignored, despite the extensive cultural encounters with these regions. In recent years, however, some studies have started to include these connections (see Lindow 1997b; DuBois 1999; Price 2002; Bertell 2003, 2006; Brink 2004).

Archaeology and Old Norse cosmology

Archaeology currently plays an increasing role in the study of Old Norse religion and cosmology, but the discipline has not always been a central part of Old Norse studies, due to changing perspectives on the complex interface between texts and material culture, as well as varying views of the interpretive possibilities of material culture. The role of archaeology in the research field largely runs parallel with the theoretical trends within archaeology itself.

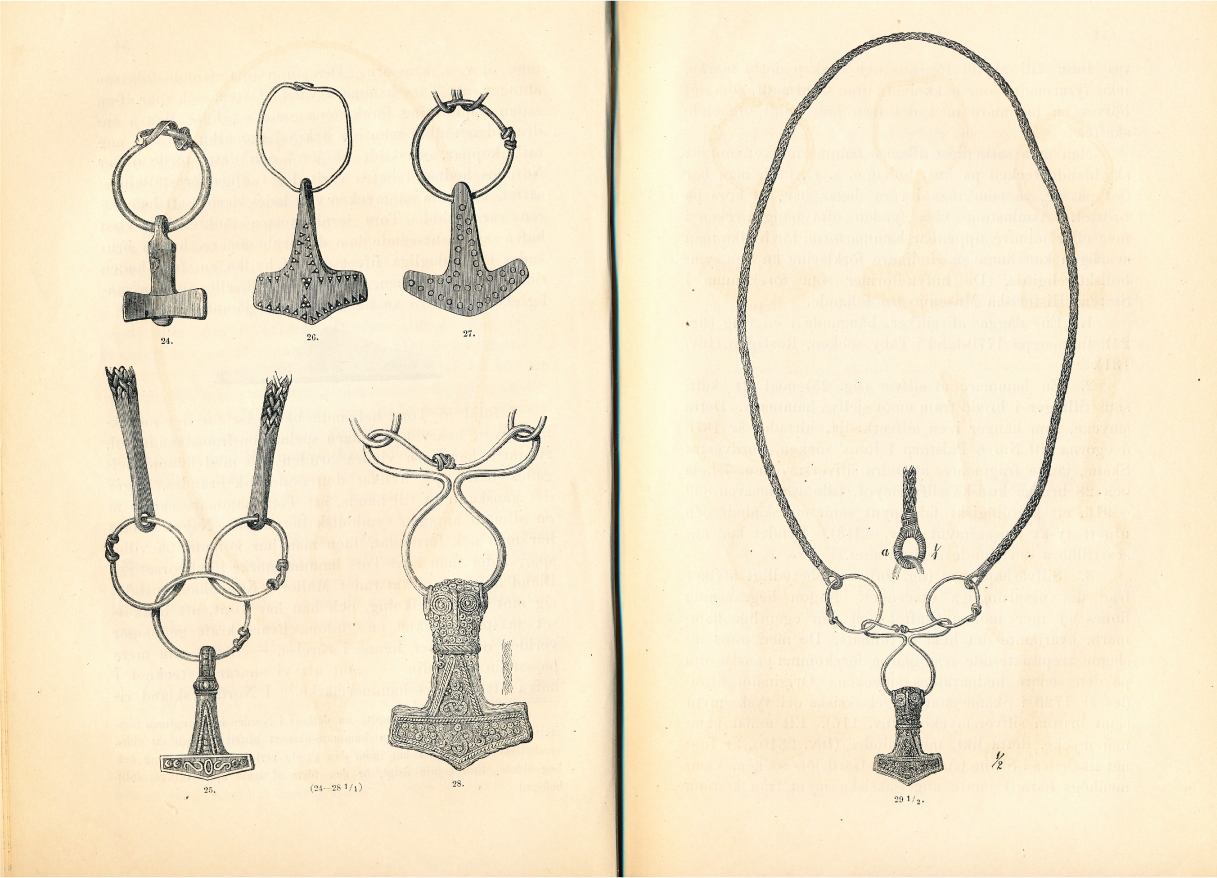

The first professional museum curators and archaeologists, such as C. J. Thomsen and J. J. A. Worsaae, were well versed in Old Icelandic literature, since it had become important in creating a Scandinavian identity and history with the Romantic movement of the first half of the nineteenth century. We therefore find some references to the Old Norse world in their works, for instance in the interpretations of gold bracteates (Thomsen 1855; Worsaae 1870). However, the first thorough archaeological study of Old Norse religion was a survey of pagan rituals and beliefs among the Scandinavians, written in 1876 by Henry Petersen, Om nordboernes gudedyrkelse og gudetro i hedenold: en antikvarisk undersøgelse. In this work, some of the fundamental links between objects and references in the Icelandic texts were examined for the first time. Petersen’s contemporary, Hans Hildebrand, used a similar approach when he identified for the first time certain small T-shaped silver amulets as representations of Miollnir (Mjǫllnir), the hammer of the thunder god Thor (Þórr) (Fig. 3; Hildebrand 1872). Nonetheless, as in other historical archaeologies (Andrén 1998a), the conventional method for a long time tended to be a rather simple ‘matching game’ between words and objects. Consequently, archaeology played a rather passive, secondary role in the study of Old Norse religion, often reduced to illustrating motifs in the texts.

In the first half of the twentieth century, the Old Icelandic literature preserved its role as a mental background for archaeological interpretations of the Iron Age, and above all for the Viking Age in Scandinavia. This is especially clear in the work of the more historically oriented archaeologists, such as A. W. Brøgger, Birger Nerman, and Sune Lindqvist (for instance, Brøgger 1916; Nerman 1941, Lindqvist 1945). In their studies, however, Icelandic textual references were used more to illuminate archaeological problems than to contribute to a general understanding of Old Norse traditions. In that sense, Scandinavian archaeology during the first half of the twentieth century followed the principles later outlined by Christopher Hawkes in a famous article from 1954, on ‘the ladder of reliability’ in this tradition (Hawkes 1954). According to him, archaeology in general could primarily be used to study technology, to a lesser extent economy and social organization, and only with great difficulty religion and mentality. Religion was more of a residual category for things that could not be explained otherwise. It was only when support came from additional texts that archaeology would be able to say anything more substantial about thoughts and beliefs.

Figure 3. T-shaped silver amulets, for the first time identified as Thor’s hammer Miollnir. This identification is today fully internalized in scholarship as well as in popular culture. (After Hildebrand 1872:52–3.)

During the 1960s, 1970s, and early 1980s, the so-called processual archaeology turned away from issues of religion, on account of the neo-materialistic and neo-evolutionary aspects of this tradition (Trigger 2006:386 ff.). Consequently, very little archaeological research was carried out in the field of Old Norse studies during these decades. The focus was instead on landscape, settlement, economy, and social organization. Above all, the archaeology of landscape and settlement made its breakthrough. Important results included new perspectives on land use, settlement structure, and hierarchies of settlements (Ambrosiani 1964; Lindquist 1968; Myhre 1972; Hyenstrand 1974; Carlsson 1979; Widgren 1983; Hvass 1985; Berglund 1991).

It was only with the cultural turn in the 1980s and 1990s, which has been labelled in the discipline as post-processual or contextual archaeology, that ideology, mentality, and to a lesser extent religion returned as important research issues (Hodder 1986; Insoll 2004). In this tradition, material culture is viewed as an active element in constant negotiations and renegotiations between people. Meaning can be ascribed to artefacts, settlements, and landscapes, which can sometimes represent complex ideas. As in many other human sciences, interpretation has been placed centre-stage in archaeology.

This interest in ideology, mentality, and religion in archaeology means that totally new results concerning pre-Christian Scandinavian religion have been achieved in recent years (see, for example Bennett 1987; Andrén 1989, 1993, 2007a; Engdahl and Kaliff 1996; Hedeager 1997, 2011; Kaul 1998, 2004; Price 2002; Solli 2002; Andrén et al. 2006; Andersson and Skyllberg 2008; Carlie 2009b; Bäck and Hållans Stenholm 2012; Svensson 2012). For example, it is now possible for the first time to have a serious discussion about the occurrence of ritual buildings in pre-Christian Scandinavia on the basis of concrete physical evidence from the Iron Age (Nielsen 1997; Larsson 2004). A part of this trend is that the Old Norse tradition in general – and not only the religious aspects – has provided analogies for archaeological interpretations. As a result, parts of Scandinavian prehistory have become very historic.

In the last decade, however, a reaction against the optimistic views and the relativism of some interpretations in contextual archaeology can be discerned. Now the materiality of objects is underlined, instead of meaning (Olsen 2003, 2010; Glørstad and Hedeager 2009). The searchlight is being directed at what material culture does to people rather than what it means. Consequently, religion is again less in focus in some archaeological research, although issues of materiality and biographies of objects are well-suited to a dialogue with ritual theory, which underlines the social meaning rather than the mental meaning of rituals (see Lund 2009).

The new focus on materiality has clearly opened up other perspectives in archaeology, but issues of meaning will not disappear. Many results from processual archaeology have been integrated into contextual archaeology, and a similar confluence will probably take in the current theoretical shift. The critique of optimistic and shallow interpretations in contextual archaeology is sometimes well-grounded, but I still find the search for mental or religious meaning important in archaeology. Especially the metaphorical potential of material culture is worth studying in relation to religion, an issue that I will explore to some extent in further down. Besides, in the different historical archaeologies in particular, the dialogue between material culture and worldviews has been studied for a long time (Andrén 1998a). These studies are usually based on thorough contextual analysis of the material culture, but are in dialogue with written sources.

Although that dialogue will be continued, the relationship between Old Icelandic texts and material culture will remain complicated. The distance in time and place between thirteenth-century Iceland and Iron Age Scandinavia means that the texts never contain descriptions of actual contexts that can be studied archaeologically. Instead, it is always a question of other non-direct relations. The indirect relationship between the two nonetheless also has constructive causes, since the common background for the written word and materiality is oral tradition. As many scholars have stressed, oral tradition is both changeable and rich in variation (Clanchy 1979; Ong 1982; Herman 2005). An extant text is therefore only one possible variant of a narrative. Material culture related to the same narrative can thus represent yet further versions, meaning that the relationship between artefacts and texts will always be provisional.

Thus, the use of material culture in the study of pre-Christian Norse religion is not uncomplicated. Furthermore, the changed view of ritual means that it can be difficult to ascertain from material traces of ritualized acts whether the rituals were connected to a religious discourse or not. The element of variation in the oral tradition also means that the identification of different motifs and figures can never be any more than provisional (see Price 2006). At the same time, the fundamental, active role of materiality in all oral culture means that artefacts can be a truly primary source for narratives, conceptions, and patterns of action in ancient Scandinavia. Objects and images could be used as mnemonic devices for composing new variants of the narratives in the form of ekphrasis (Clunies Ross 2005:54). While cosmological perspectives are sometimes merely hinted at in mythical or heroic narratives, the worldview can be depicted in a highly systematic way in material culture, for example in settlement, buildings, and artefacts. Recurrent formalized acts at one and the same place may even show concretely how certain patterns of action were maintained for generations, in that the place and the acts were part of the collective memory. Consequently, the use of material culture in the study of Old Norse religion and cosmology has a great potential.

Figure 4. The chancel and apse of the Romanesque church at Vä in Skåne. The paintings in the vault of the chancel depict a divine choir of angels singing the psalm Te Deum, according to the banderoles. The images and the texts show how the chancel vault can be interpreted as a representation of heaven, being part of the Christian cosmology. (Photo by the author.)

It is clear that in many cultures, different aspects of worldviews are expressed through material culture. Objects and buildings may have been designed according to ideas about the structure of the world, and settlements as well as whole cities may have been laid out according to cosmological principles. Good examples from literate societies are Chinese cities planned as prototypes of the universe, Hindu temples constructed as the world mountain, and Romanesque churches (Fig. 4) built as expressions of Christian history from the Creation to Judgement Day (see Wheatley 1971; Fritz and Mitchell 1987; Krautheimer 1942; Deichmann 1983:89 ff.). Material culture can also be used to express worldviews in oral cultures such as the layout of Navaho houses (Aveni 2008:111 ff.) and the design of tattoos in Polynesia (Gell 1993). In several cases, it seems that the material representations of different cosmologies are more systematic than they are in the narrative references. This raises the question of whether material expressions of different cosmologies could not only trigger systematic thinking about the world, but in some sense could be regarded as the source of cosmological ideas. Material culture, accordingly, did not only represent ideas, but partly formed the material basis for these ideas.

The material aspect is above all underlined in cases where cosmologies were connected with ritual space, such as Hindu temples, Romanesque churches, and prayer rugs. In these instances, the different categories of ritual and myth all but merge into a single category, in ways that current ritual theory does not really take into account. In that sense, cosmology can be categorically placed between ritual and myth, making it an ideal point of departure for investigating fundamental myths as well as important rituals.

Three archaeological studies

The three following studies are all focused on central cosmological elements in the Old Norse worldview – that is, notions of the construction of the world. The first study, ‘In the shadow of Yggdrasill’, is a revised translation of a Swedish text published previously (Andrén 2004). It is an archaeological investigation of a question raised by a central figure of thought, the world tree, in Icelandic mythology. As I will show, the idea of a world tree seems to have developed gradually over time, to reach the notion recorded in the medieval Icelandic narratives. The second investigation, ‘A world of stone’, proceeds from the opposite position; in other words, it starts out from an analysis of an archaeological monument. The text is based on a preliminary report of the fieldwork at the site (2006). It is an investigation of the notion of Midgard, and its possible creation as part of the cultural encounter with ordered cosmologies in the Roman Empire. The final essay, ‘Whirls, spirals, and horses’, was also written specifically for this volume, but a summary of the text has been published recently (Andrén 2012b). It is based on images from the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, and concerns solar aspects of a cosmology that had almost completely disappeared before the Viking Age and early Middle Ages. The essays are ordered in a cosmological sequence, starting from the middle of the world and proceeding to the sun, which was seen as the main celestial figure moving around the world. In the conclusion, some aspects of Old Norse religion and cosmology in long-term perspectives will be considered.

Figure 5. The oak at Norra Kvill in Rumskulla in Småland. It is believed to be more than a thousand years old. (From Wikimedia Commons.)