CHAPTER 2

In the shadow of Yggdrasill

The tree between idea and reality in Scandinavian traditions

A distinct figure of thought in Old Norse cosmology is a world tree standing in the middle of the world, with a huge crown reaching up to heaven and with roots going into different parts of the world. The meaning, function, and historical background of this world tree have been extensively debated by textual scholars. Usually, however, archaeologists have been absent from these debates, probably because this central cosmological idea has been regarded as falling outside the realm of material culture (see Hawkes 1954). Such a position can nonetheless be questioned, since cosmologies have often been represented and enacted in the material culture of many societies in different parts of the world (see, for instance, Krautheimer 1942; Wheatley 1971; Rykwert 1988; Andrén 1998a). Therefore, there are good general arguments for undertaking an archaeological study of the Old Norse world tree.

This transcultural phenomenon – that worldviews can be represented in material culture – illustrates several aspects regarding the concept of material culture. Although the tangible and silent materiality of things has been underlined in recent debates (for instance Olsen 2010), it seems as if material culture is an umbrella term for highly varied and heterogeneous things (Hodder 1994). Some of these things may have representative qualities, others may not. But material representations should not necessarily be viewed as symbols in the linguistic sense of de Saussure, meaning that there always is an arbitrary relation between form and content. Instead, material representations can be regarded as ‘concrete symbols’, linking function and meaning in different ways. In that sense, there can be complex connections between the mental world and the experienced human world. This means that, in relation to the Old Norse world tree, there may have been complex interactions between mythological trees, real trees, and representations of trees. In order to study this figure of thought archaeologically, it is therefore necessary to discuss each of these forms in which the tree appears.

Mythological trees

The ash of Yggdrasill, which stands in the middle of the world, with its crown reaching heaven and its three roots extending to the different parts of the world, is a well-known element in Old Norse cosmology (Fig. 6). In textbooks on the pre-Christian religion of Scandinavia there is normally a description of the world tree, its attributes and inhabitants (see, for example, de Vries 1957:380 ff.; Ström 1961:97 ff.; Näsström 2001:27 ff.). There is also a more specialized literature about the tree, its mythological significance, and the meaning of its name (Steinsland 1979; Simek 1993:375–6; Kure 2006). With few exceptions, these modern commentaries and interpretations are often somewhat homogenizing, since aspects of trees with other names are often added to the description of Yggdrasill. All the same, it must be admitted that this homogenizing tendency can be detected as early as the works of Snorri Sturluson, since in Gylfaginning he already attributes elements to Yggdrasill, which have been borrowed from other contexts. From other parts of Snorri’s Edda and from the Poetic Edda and occasional skaldic verses it is clear that we can count references to at least three mythological trees, namely, Yggdrasill, Mimameid, and Lærad, which may all be viewed as representing three different aspects of the idea of a world tree.

Yggdrasill is mentioned most frequently, but the name is controversial. The most common interpretation is that the name means ‘Odin’s horse’, which is a poetic metaphor (kenning) for ‘gallows’, referring to how the god Odin (Óðinn) hanged himself in the world tree. Suggested interpretations such as ‘the terrible tree’ allude to the same motif, but there is also a completely different but less likely interpretation, according to which the name of the tree means ‘the yew support’ (Simek 1993:375–6).

The different parts and attributes of Yggdrasill are stated most clearly in Vǫluspá 19, 47, Grímnismál 29–35, 44, and Gylfaginning 14–15, where the description is largely based on Vǫluspá and Grímnismál (Steinsland 1979; Simek 1993:375–6). According to these Eddic poems, the ash Yggdrasill is a tree at the top of which sits an eagle. Four stags browse on the buds in the crown of the tree, and dew from the leaves drips all over the world. A dragon and countless serpents gnaw at the roots of the tree, while a squirrel runs up and down the trunk, carrying malicious messages between the eagle in the crown and the serpents at the roots. The three roots of the tree reach all over the world, and under the roots are humans, the giants, and the realm of the dead, Hel. Beside the tree are the well of fate or Urd’s well (Urðar brunnr) and the hall of the women of destiny of the Norns (nornar). According to Vǫluspá 19, the tree is showered with ‘shining loam’ (hvítaauri). Snorri states in Gylfaginning 15 that the Norns take this liquid from the well and pour it over the tree, so that the branches will not dry out. The seat of the speaker or reciter of the assembly (þular stóll) is placed at Urd’s well according to Hávamál 111, whereas the god Thor holds court with the other Æsir at Yggdrasill according to Gylfaginning 14.

Figure 6. A reconstruction of the Old Norse world tree. The Icelandic scholar Finnur Magnússon (1781–1847) was the first to visualize Yggdrasill. His understanding of Old Norse cosmology has had a long-lasting effect on scholarship and popular culture (see Clunies Ross 2011). (After Magnusen 1825, photo by Jens Östman, Kungliga Biblioteket, Stockholm.)

Snorri also states in Gylfaginning 14 that Yggdrasill has three roots, but he tells us instead that they reach the frost-giants (Hrímþursar), the dark realm of the dead (Niflheim) and the gods ‘in heaven’, in an attempt to harmonize different poetic accounts of Yggdrasill. According to Vǫluspá 47, Yggdrasill ‘groans’ on the eve of Ragnarok, but its fate in connection with the destruction of the world is not clearly expressed in the poem. Most scholars assume that the tree burns up along with the rest of the world (Hallberg 1952). Some think that a new tree grows up after the end of the world (Steinsland 1979), while others believe that there may have been a world tree in each preceding age of the world (Schjødt 1992).

Three further details are normally associated with Yggdrasill in accounts of the Nordic world tree. Under ‘the radiant, sacred tree’ (undir heiðvǫnom helgom baðmi), according to Vǫluspá 27, there is Heimdall’s hearing or sound (Heimdallar hljóð), which may refer to the ear of the god Heimdall (Heimdallr) or to the horn Gjallarhorn, which he blows at Ragnarok (Simek 1993:135–6). According to Hávamál 138–41, Odin hangs himself on a ‘windy tree’ (vindgameiði) for nine nights in order to acquire knowledge of the runes. Vǫluspá 2 mentions furthermore the mighty ‘measuring tree’ (mjǫtviðr), which is associated with nine worlds or nine preceding ages (Schjødt 1992). Many interpret these expressions as further descriptions of Yggdrasill, but the three poems do not explicitly state that they are referring to this particular tree. Yet another allusion to Yggdrasill could possibly be found in the note about eagles sitting on the branch of the ash in Helgakviða Hundingsbana II:50 (Hofsten 1957).

A different tree that is not mentioned so often is Mimameid (Mímameiðr), which can be interpreted without ambiguity as ‘Mimir’s tree’ (Simek 1993:216). It is described in the late Fjǫlsvinnsmál 20 and 24 as a deciduous tree that spreads its branches out over the world. An obscure passage states that the fruits of the tree should be borne ‘on fire’ to sick people and ‘women suffering in secret’, which perhaps refers to curative smoked fruit or roast nuts and acorns (Hofsten 1957). Sitting in the tree is a cock, which may only be killed by a sword and which then falls down into the halls of Hel. The sword is made by Loptr, another name for the god Loki, and is kept in a chest with nine locks by Sinmara, wife of the fire-giant Surt (Surtr). The reference to Surt also invokes associations with Ragnarok, since according to Vǫluspá 47, 52–3, Surt plays a crucial role in the destruction of the world (Simek 1993:303–4). Mimameid is attested only in Fjǫlsvinnsmál, but the tree must be connected to Mimir’s well (Mímis brunnr), which is mentioned in Vǫluspá 28. Snorri states in Gylfaginning 14 that Mimir is a wise man because he drinks from the well with the aid of Gjallarhorn. It was also in this well that Odin sacrificed one eye in order to attain wisdom. At Ragnarok, Odin will also acquire advice from Mimir’s head, according to Vǫluspá 46, Gylfaginning 50, and Ynglinga saga 4, 7. The scattered details about this particular tree can perhaps be juxtaposed with the information given in Vafþrúðnismál 45 about Hoddmimir’s wood (Hoddmímis holt), which may be interpreted as the tree trunk in which the two humans Life (Líf) and Lifthrasir (Lífþrasir) survived Ragnarok (Simek 1993:154–5). This interpretation hints that part of the tree somehow managed to escape destruction in the fire at the end of the world. The cock in Mimameid has meanwhile been regarded as a parallel to another cock, which, according to Vǫluspá 42, sits in the gallows tree (galgviðr) in Jǫtunheim, the world of the giants (Steinsland 1979:130).

A third tree, Lærad (Læraðr), is mentioned in Grímnismál 25–6 and hence also by Snorri in Gylfaginning 38. The meaning of the name is uncertain; suggested interpretations include ‘damager’, ‘protector’, and ‘giving liquid’ (Simek 1993:185). This tree stands by Valhall (Valhǫll), the hall of the slain warriors, and a goat and a stag gnaw at its branches. The goat stands on the roof of Valhall, and from its horns comes the mead that the heroes in Valhall (einherjar) drink. From the crown of the stag, water drips down into the well Hvergelmir (‘the bubbling cauldron’), which is the source of all rivers (Simek 1993:185, 166–7). In addition to these three trees, we read in Vǫlsunga Saga 2 that in the middle of the hall of the Volsungs there was a large oak called ‘children trunk’ (barnstokkr), which may indicate that women gave birth under the tree. Odin had stuck a sword into the oak and only Sigmund, son of Volsung, could pull it out (de Vries 1957:385).

In Old Norse cosmology, then, the tree stands out as a distinct but complex figure of thought. I therefore think that we should not regard Yggdrasill as the ‘true’ world tree, but should consider Yggdrasill, Mimameid, Lærad, and Volsung’s tree, and possibly ‘the sacred tree’, ‘the windy tree’, ‘the measuring tree’, and ‘the gallows tree’, as variations on a common tree theme. Some of the names seem to be poetic variations only, whereas other names were probably linked to different myths in which different aspects of the figure were emphasized. In part, the various names seem to reflect ideas about trees in different suprahuman worlds (Steinsland 1979). What the different versions have in common is the connection with Odin, who hangs himself in ‘the windy tree’, probably sacrificed his eye in Mimir’s well, lives near Lærad, possibly has given his name to Yggdrasill, and is the divine ancestor of the Volsungs. At least two of the trees are moreover linked to Odin’s search for knowledge (Schjødt 2004), namely, the knowledge of the runes that he acquired by hanging himself in ‘the windy tree’ and the wisdom attained by the possible sacrifice of an eye, in Mimir’s well. Urd’s well at the roots of Yggdrasill is likewise associated with knowledge and wisdom. Perhaps the statement about the mead flowing from the goat that stands on the roof of Valhall can also be viewed as an echo of an alternative myth about the origin of skaldic mead, and hence the art of poetry (Drobin 1991).

Alongside Odin, the gods Thor and Heimdall can also be connected with the world tree. According to Snorri, Thor holds court with the Æsir at Yggdrasill (Gylfaginning 14) and saves himself from a flooded river by pulling himself out of the water with the aid of a tree trunk (Skáldskaparmál 18; Simek 1993:20–1). As noted above, Heimdall’s ear or horn Gjallarhorn can be found at Yggdrasill, and Heimdall also winds Gjallarhorn at Ragnarok. The interpretation of the name Heimdall is disputed (Ström 1961:133 ff.; Simek 1993:135–6; Cöllen 2011). Some scholars interpret it as ‘he who lights up the world’, while others believe that the meaning is ‘world tree’ or ‘world pillar’ (Cöllen 2011). The latter interpretation fits well with the god’s by-name Hallinskidi (Hallinskíði, meaning ‘the leaning split log’ or ‘the forward-leaning staff’) given in Gylfaginning 26. In this sense, Heimdall himself may be seen a personification of the world tree or the world pillar, which could explain his diffuse role in the Nordic myths.

Apart from these divine links, there is also a clear relationship between the tree and human beings. According to Vǫluspá 17–18, the first humans were Ask (‘ash’) and Embla (meaning disputed; Josefsson 2001). In Gylfaginning 8, Snorri also says that they were made from two tree trunks which had floated ashore. Odin and two other gods, according to Vǫluspá 18 and Gylfaginning 8, gave these tree trunks human life by adding ‘breath’ (ǫnd), ‘spirit’ (óðr), ‘vital spark’ (lá), and ‘fresh complexions’ (góðr litr) (Steinsland 1983; Simek 1993:21). In a similar way, the only two people who are said to survive Ragnarok probably derived from a tree trunk. As mentioned above, Líf (‘life’) and Lífþrasir (‘he who strives for life’) hid in Hoddmimir’s wood, according to Vafþrúðnismál 45. Similar ideas about a connection between trees and human life recur in Ǫrvar-Odds saga, which mentions that the hero rejuvenates himself by living as a ‘tree-man’ for a period (Simek 1993:20–1, 74, 335). One also notes that in Vǫluspá 1 humans are called ‘offspring of Heimdall’ (mǫgo Heimdallar), which may also allude to the same relationship between trees and man, especially if Heimdall is perceived as a personification of the world tree or world pillar. Indeed, the link between humans and trees is so prominent that the world tree and the well at its roots have recently been interpreted as a metaphor for the male and female sex organs (Kure 2002; see also Josefsson 2001).

The world tree, in other words, stands out as a central but ambivalent figure of thought in Old Norse cosmology. It was related to fundamental questions about the creation and structure of the world, about the origin of knowledge and the descent of man. The tree stood in the centre of the world, surrounded by the creatures and powers inhabiting the earth, and through its trunk it connected heaven, earth, and the underworld (Schjødt 2004). Concepts such as time and place, destiny and death were thus associated with the tree (Clunies Ross 1998:245).

The idea of a world tree or a world pillar in the middle of the world is not unique to Old Norse cosmology. Thanks above all to the classic study by Uno Holmberg, Der Baum des Lebens (1922–3), the Old Norse world tree has long been discussed in relation to many parallels in much of Europe and Asia. The Old Norse world tree has thus been incorporated into a general discussion in the history of religion about the world pillar, the axis mundi (Eliade 1958).

The boundary between world tree and world pillar is fluid, since they can both be perceived as ‘functional alternatives’ in early cosmologies. Åke Hultkrantz nevertheless believes that there are certain structural differences between the two forms. The world tree alludes chiefly to the link between heaven, earth, and the underworld, while at the same time the tree is often seen as a representation of a god. The world pillar, on the other hand, bears up the heavens, and in several traditions its top is attached by a nail to the ‘immobile’ Pole Star. The idea of a world pillar was most common in circumpolar cultures, whereas the idea of the world tree was more prominent outside the Arctic and subarctic area. In certain cultures, for instance among the Sámi, there were beliefs about both world tree and world pillar (Hultkrantz 1996).

The Old Norse figure of a world tree beside a well shows general similarities to ‘the tree of life’ or ‘the tree of knowledge’ (Fig. 7), and to paradisal rivers of milk and honey, recurrent themes in many ancient traditions in the Near East, not least in the description of the Garden of Eden in the Old Testament. In certain other details, too, the Old Norse idea of the world tree finds striking parallels in European and Asian traditions concerning both world trees and world pillars (Holmberg 1922–23; de Vries 1957:382 ff.). An eagle sitting at the top of the crown is also found in the Persian ‘eagle-tree’, while stags and a goat are associated with the world tree in both Persian and Assyrian traditions. A squirrel, acting as intermediary in a battle between a bird and serpents, is found in both Greek and Indian myths. A dragon lies at the root of the cosmic tree in several Siberian traditions, while shamans move between the seven or nine worlds connected to the world tree or the celestial axis. Other Siberian myths mention a milky liquid found in a spring under the world tree or dripping from its branches over the first humans. Even such a particular detail as Snorri’s description of a root that reaches heaven has parallels in the idea of an arbor inversa, that is, an upside-down world tree. The belief is attested in Indian myths about trees, as also in Siberian ‘shaman trees’ and in Sámi sacrificial rituals involving tree trunks with their roots turned upwards (Coomaraswamy 1938; Edsman 1944; Mebius 1968:61 ff.). In certain Siberian myths, the upturned shaman tree symbolized the upper celestial world (Mebius 1968:151, 2003).

Figure 7. A gravestone from Ekeby on Gotland for one Olof of Ekeby, who died in 1316. The central image shows how the Christian cross could be regarded as the Tree of Life. (After Hildebrand 1898–1903:455.)

The similarities between notions of a world tree and world pillar in Europe and Asia have led to extensive discussions of the age and origin of the idea. Sophus Bugge argues that the parallels above all with the Near East simply show that the idea of the world tree was introduced with Christianity, and that it is an expression of the syncretistic society in which Old Norse literature was created (Bugge 1881–9:399 ff.). Although many scholars agree that there may be Christian elements in the Old Norse idea of the world tree, most believe that the idea is ‘primeval’, since the parallels show such a wide geographical and cultural spread (see, for instance, Ström 1961:98; Steinsland and Meulengracht Sørensen 1994:31). From a diffusionist perspective, Holmberg (1922–3) argues that the idea originated in the Near East and India, from where it spread over Asia and Europe. Jan de Vries (1957:392) claims instead that the idea is ‘pre-Germanic’, but nevertheless Indo-European, based on linguistic parallels. Björn Collinder (1926), on the other hand, regards the Arctic and subarctic regions as the source of the idea. Thede Palm (1948:121) is thinking along the same lines when he suggests that the Old Norse concept of the world tree and its shamanistic features were conveyed via Sámi culture. Åke Hultkrantz (1996) has recently arrived at a similar view, arguing from an ecological perspective that the world pillar represents an archaic circumpolar worldview, of Mesolithic or even Palaeolithic origin. The question of the history and meaning of the Old Norse world tree is thus disputed, and its relation to people’s lived world in the distant past is obscure.

Real trees

The discussion of mythological trees in relation to real trees has mainly followed two lines. On the one hand, there are various forms of ‘holy trees’, which can be regarded as a more or less obvious representation of the cosmology. On the other, there are ‘farm trees’ or ‘guardian trees’ of later times, which can be perceived as a fundamental element in the cultural landscape, from which the figure of the ‘world tree’ may have derived part of its inspiration.

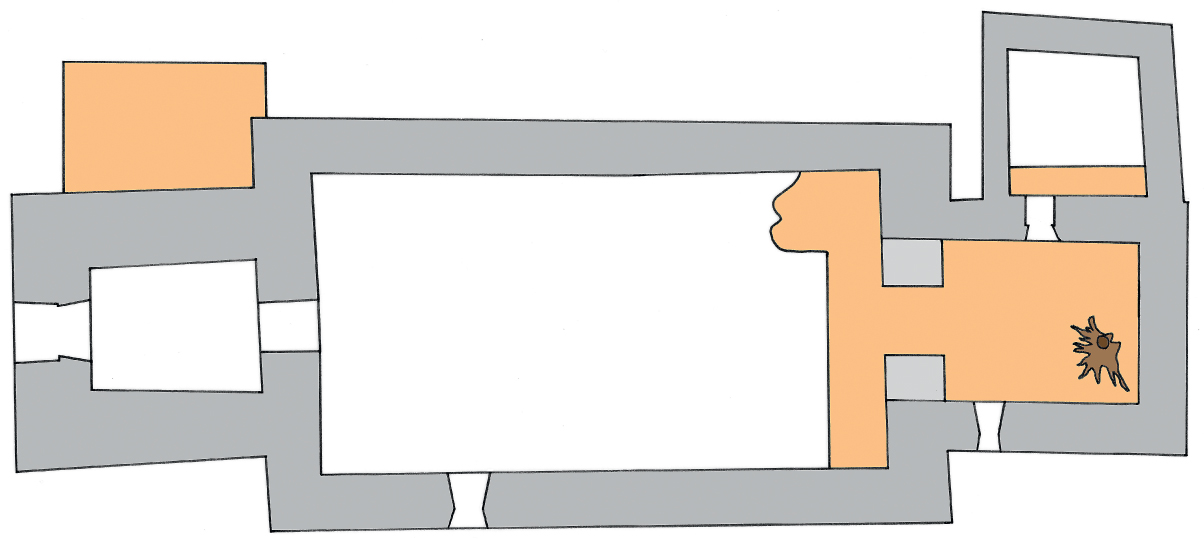

The link between the cosmological trees and ritually important trees in the real world has long been of interest in Scandinavia. The frequently cited but controversial example is Adam of Bremen’s account of the tree ‘always green, winter and summer’ (semper viridis in hieme et aestate), which stood ‘near the temple’ (prope illud templum) at Gamla Uppsala (Adam of Bremen IV, scholion 138; see de Vries 1957:382; Hultgård 1997). His description has long been questioned (most recently by Janson 1998), but it has a parallel in the independent Hervarar Saga, which also speaks of a ‘sacrificial tree’ (blóttré) at Gamla Uppsala (Sundqvist 2002:131). The tree at Gamla Uppsala could therefore be viewed as a ritual focus for the site and as a representation of the Old Norse world tree (Sundqvist 2004; Warmind 2004). The excavated remains in Frösö church of a birch root surrounded by deposited animal bones (Fig. 8) provide yet further support for the argument that votive trees, probably with cosmic associations, existed in Viking Age Scandinavia (Hildebrandt 1985, 1989; Iregren 1989; Näsström 1996; Andrén 2002:322).

Figure 8. The Romanesque church at Frösö in Jämtland, with the extent of the excavations (in yellow) and the investigated birch root (in brown) from the Viking Age. The birch root was found by the altar of the church, indicating a cosmological continuity at the site. (Plan by the author, based on Almqvist 1984:122 and Hildebrandt 1985, 1989.)

The idea of a link between the world tree and later guardian trees is old, going back to the ideas of, above all, Wilhelm Mannhardt that pagan relicts were preserved in European folk culture and that the fertility cult was the fundamental element in pre-Christian religion (Mannhardt 1875:54; de Vries 1957:382). He saw the origin of the Old Norse world tree in a fertility cult focusing on guardian trees and a generally ‘animated’ nature. Although later historians of religion have not accepted Mannhardt’s vegetative cult, many do stress the link between guardian trees and world trees (see, for instance, Ström 1961:97; Steinsland and Meulengracht Sørensen 1994:30). The relationship between latter-day guardian trees and the Old Norse world tree is nevertheless problematic as regards source criticism, since all the information on guardian trees is based on records of folk traditions from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries. These records show that each guardian tree was very closely related to the farm and its inhabitants. The fate of the tree was virtually synonymous with the fate of the people and the farm. That was why it was often forbidden to break off branches or to damage the tree in any way. It was also common that votive offerings were made at the tree in connection with childbirth and marriage (Palm 1948:60 ff.; Vikstrand 2001:283). The more or less explicit argument for seeing a link between these modern guardian trees and the world tree of Old Norse mythology is based on certain structural similarities, such as the link between humans, destiny, and trees.

The question of whether there were corresponding guardian trees for settlements in pre-Christian times is difficult to answer, but the best argument for their existence is that the names of various trees occur in place-names from the Iron Age. Sigurd Fries (1957), in his study of Nordic tree-names, has pointed out that trees in pre-Viking Age place-names with the generics -hem and -vin are always in the singular. In Viking Age place-names ending in -by, on the other hand, the specific is usually in the plural, although singular forms do occur. Just under 25 per cent are singular forms in Swedish names ending in -by with trees as the specific. The plural forms always refer to stands of several trees, but Fries believes that the singular forms can also refer primarily to more than one tree, as a kind of abstraction. Yet Fries does not dismiss the possibility that the names may have referred to individual trees. The best argument is that there are a number of single-element names such as Ask (ash), Ek (oak), and Krokek (crooked oak), which seem more clearly to have referred to important individual trees. In the Mälaren area these single-element names are always found in central Iron Age districts of great antiquity (Vikstrand 2001:275, 2004). In other words, the place-names suggest that both during and before the Viking Age there were important trees that were so closely associated with farms and villages that they served as the basis for the names people gave to places (see Brink 2001). What is interesting in this perspective is that by far the most common tree-name among the pre-Viking Age names ending in -hem is the ash (Fries 1957), which thus suggests associations with the Norse world tree.

It was not unique to Scandinavia that individual trees were of great importance in people’s lives. Evidence of sacred trees at places of assembly and cultic sites can be found, for example, in Celtic, Slavic, Saxon, and Greek traditions. Medieval Irish sources state that an ash on Mount Uisnech was the holiest tree in Ireland. The mountain was believed to be in the centre of Ireland, and was therefore the scene of large annual gatherings. Other places in Ireland were also associated with single ashes, oaks, and yews (Maier 1997:272, 275–6).

A Slavic equivalent to Gamla Uppsala and Uisnech may be Szczecin (Stettin) in Pomerania. According to the German monk Herbord’s description from the 1150s, there was a large oak and a spring beside a ‘temple’ with idols (Słupecki 1994:73, cf. Sundqvist 2004). Carolingian sources show that in Saxony there were likewise sacred trees with ritual associations. There is a particularly explicit record of the holy ‘Jupiter oak’ (probably ‘Thor’s oak’) in Geismar (Hessen), which the Anglo-Saxon missionary bishop Winfrid (St Boniface) ordered to be chopped down around 720 (Palm 1948:49 ff.). Before this, classical writers with their descriptions of the Celtic druids hint at a connection between humans, knowledge, and trees. The druids always performed their rituals with oak leaves, and the Latin word druida probably derives from a Celtic word meaning ‘he who has knowledge of the oak’ (Maier 1997:98–9, 211).

In classical Greece there were numerous special trees with ritual functions and mythological references. A recurrent feature was that important trees grew at major sanctuaries, as was the case with the olive tree on the Acropolis in Athens (Birge 1994). In certain instances the trees could be associated with the myths, since they were believed to mark the birthplace of gods and goddesses, for example, Hera on Samos and Apollo and Artemis on Delos (Marinatos and Hägg 1993). In other cases the ritual functions of the trees were particularly obvious, as with the oaks of Zeus in Dodona (Lauffer 1989:197 ff.), where an oracle spoke through the rustling of the oak leaves. The tenacious importance of the holy trees in Greece is particularly clear at Dodona (Fig. 9). The site with its oaks is mentioned as early as in the Iliad, probably from the eighth century BC, but even for Homer the oracular cult was ancient, said to be ‘Pelasgian’ (‘pre-Greek’). For more than a thousand years the oracular function of the oaks was maintained, and it was not until AD 391 that they were cut down, when a bishop’s see was established on the site. Dodona has been excavated, and the site of the oaks was found to be walled off by a small enclosure, which had been renewed several times (Lauffer 1989:199). Many of the surrounding buildings were much more monumental, which means that the most important place at Dodona does not stand out very clearly in archaeological terms.

Figure 9. The peribolos wall around the site of holy oaks at Dodona in north-west Greece. New oaks were planted within the walls during the twentieth century. (Photo by the author.)

The number of more or less ‘sacred trees’ could be multiplied with the addition of both European and non-European examples, since the tree seems to have had a virtually universal metaphorical potential (Rival 1998). The background to the prominent role of the tree is probably at once practical and cognitive. In the pre-industrial world, trees were a crucial resource for human activity and survival. Houses, boats, and tools were all made of wood, and leaves from pollarded trees were important fodder for livestock in some areas. Besides, trees in the form of fuel were necessary for all kinds of human transformation of nature, such as cooking, pottery, metal production, and cremation. From a cognitive perspective it is also important that certain species of tree can reach a very great age, such as yew, oak, and ash (see Fig. 5). The oldest examples in northern Europe today are at least 1,000 years old, some perhaps even 1,500 years (Österman 2001; Bevan-Jones 2002). Both now and in the past, old trees were therefore a kind of constant in the landscape, going far back beyond human memory. The trees have ‘always’ been there, and will ‘always’ be there. They had become a kind of ‘natural place’ (Bradley 2000) in the same way as rocks, mountains, and water, but with the difference that they were alive and growing. As growing species, trees were connected to the underworld by their roots, but also reached out towards heaven via their crowns. The wide-ranging practical uses for trees, along with their potential age and their growing structure, thus enabled them to serve as important metaphorical elements in the landscape. How important they were and the meaning they were assigned, however, were determined by the historical context.

Generally speaking, trees have been important elements, often with mythological associations and ritual functions. Even in Scandinavia there are occasional records showing that rites were connected to trees. Moreover, place-names with a tree as the first element suggest that particular trees had special relations to both settlements and people. But despite their great significance, the real trees are an almost insoluble archaeological challenge. We know that the trees existed, but at present we often lack techniques with which to detect them convincingly. All that remains are some important but highly random finds such as the tree root under Frösö church. Instead, archaeological investigations of the tree motif have to follow other paths, namely, representations of trees.

Representations of trees

In Scandinavia, as elsewhere, three different forms of representations of trees can in principle be studied: (i) tree trunks, logs, and posts; (ii) pictures; and (iii) monuments built of earth and stone.

The use of trunks and posts proceeds from the idea of pars pro toto, meaning that parts of a real tree have been used as a reference to more metaphorical trees. One such possible tree representation is the common custom of burying dead people in tree trunks or wooden containers. The oldest clear evidence of this practice in Scandinavia comes from the Danish oak coffins from the Early Bronze Age (Fig. 10), dated by dendrochronology mainly to the fourteenth century BC (Jensen 2002:186). But there are also more diffuse and indirect traces of probable tree-trunk coffins from the Late Neolithic (c.2400–2000 BC, see Lomborg 1973:112 ff.). In the Late Bronze Age and Pre-Roman Iron Age (1200–1 BC) cremation graves gradually took over and the tree-trunk coffins disappeared. But the association between dead people and trees was preserved, as the cremated human bones were sometimes placed in wooden vessels sealed with resin (Granlund 1939). From the Roman Iron Age onwards (AD 1–400), inhumation was reintroduced parallel to cremation graves, and in several cases there is indirect evidence that the dead were once again buried in tree trunks (Voss and Ørnes-Christensen 1948; Andersen et al. 1991:31–2). The end of this mortuary practice comes with early Christian tree-trunk coffins of ash, oak, and lime from several places in southern Scandinavia. In Lund this type of coffin can be dendrochronologically dated to the period AD 990–1050 (Mårtensson 1976).

Figure 10. Oak coffin found in a Bronze Age mound at Egtved in Jutland. The oak coffin contained a young woman who, according to dendrochronology and preserved flowers, was buried during the summer in 1370 BC. (After Thomsen 1929, table xi).

If tree-trunk coffins and resin-sealed vessels are considered as representations of trees, mortuary practices as well as worldviews can be placed in new perspectives. The tree-trunk coffins in particular could be given meaning by being associated with the idea that the first humans were made from two logs which floated ashore, and that the only two people to survive Ragnarok were hiding in a tree trunk (see the discussion of Hoddmimir’s wood above). From this point of view, the tree-trunk coffins could be seen as reflecting the idea that death was a return to man’s original vegetative form or as a rebirth comparable to the regeneration of the world after Ragnarok. At the same time, the early certain and possible datings of tree-trunk coffins mean that aspects of the world tree idea could be very old in Scandinavia.

When it comes to standing posts and logs, they may have represented either the world tree or the world pillar, but bearing in mind that these conceptions were ‘functional alternatives’, the specific references are less crucial in this context. There are, however, few clear archaeological examples in Scandinavia of posts or tree trunks with cosmic associations. The best example is a post placed on a central terrace near the main building at the central place at Helgö. Around the post, ritual deposits from the period 550–800 have been found, including several layers of clay. Torun Zachrisson (2004a, 2004b) has interpreted these layers of clay as counterparts to the ‘shining loam’ that the Norns poured over Yggdrasill according to Vǫluspá 19 and Gylfaginning 15.

Otherwise the ritual use of piles and posts is chiefly known from written sources (Drobin and Keinänen 2001), especially from Arabian descriptions from the tenth century. Ibn Fadlan records how Scandinavian merchants sacrificed food and drink to a tall wooden pole with a human-like head beside the Volga, while Al-Tartushi describes how the inhabitants of Hedeby hung up animal sacrifices on poles outside their houses (Wikander 1978; Montgomery 2000). Indirect evidence of posts and poles with ritual functions comes from the prohibition of the worship of ‘staves’ and ‘stave enclosures’ in the laws of Eidsivathing and Gotland, dated to the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, respectively (Holmbäck and Wessén 1943:207, 292; Olsson 1976; Nilsson 1992). Certain staves were clearly associated with the Old Norse pantheon, which is evident from place-names like Nälsta, meaning ‘Njärd’s staff’ and connected with a possible goddess Njärd (Vikstrand 2001:95, 294 ff.). The by-name of the god Heimdall, Hallinskidi (‘the forward-leaning staff’), could be apprehended as indirect evidence that posts with cosmological associations existed. Some scholars have taken high-seat pillars as possible representations of the world tree or world pillar. In particular, statements that ‘divine nails’ (reginnaglar) were hammered into the pillars have been regarded as an analogy to the world pillar, which was fixed by a nail to the ‘immobile’ Pole Star (Simek 1993:262–3; Drobin and Keinänen 2001).

These mainly indirect pieces of evidence are corroborated by a number of non-Scandinavian parallels involving posts as representations of the world tree or world axis. The best-known example comes from the Carolingian conquest and conversion of Saxony. In the Saxon stronghold of Eresburg (present-day Obermarsberg) stood Irminsul (Irminsūl, ‘the great pillar’), which was described as a ‘world column’. After the conquest of the stronghold in 772, the post was destroyed and replaced by a church, by order of Charlemagne. Later the Carolingian church was replaced by a Gothic church, which is still preserved and located at the highest point of Obermarsberg (Fig. 11). The location of the church shows that Irminsul stood at the highest point of Eresburg (Palm 1948:75 ff.; Best et al. 1999; see Sundqvist 2004).

Figure 11. Obermarsberg from the north. The Saxon hillfort of Eresburg was situated on the site of the modern Obermarsberg. The Gothic church with its tower is clearly visible at the top of the hill. The church replaced a Carolingian church which was built on the site of the world pillar Irminsul. (Photo by the author.)

Irminsul is known only from written sources, but in Russia there are clear archaeological parallels from the same time, for example, in Perynia south of Novgorod, in Pskov, and in Tushelma near Smolensk. The common pattern is large posts or post-holes, surrounded by circles of pits, graves, or smaller posts. Several of these structures have been found in the centre of fortresses, pointing towards contexts similar to Irminsul (Słupecki 1994:122 ff.). Another archaeological example is a large post found east of the main hall at the Anglo-Saxon royal site of Yeavering in Northumberland (Hope-Taylor 1977).

These examples come from a time corresponding to the Scandinavian Late Iron Age, but both archaeological and ethnographic records show that posts and logs as representations of trees have occurred over a very long time. A very early example is ‘Seahenge’, which was recently found in a marshy area in eastern England. The structure consisted of a circle with a diameter of about 5 metres, composed of 55 small stakes. In the middle of the circle was a large tree trunk placed with the roots upwards. The monument can be dated by dendrochronology to 2050 BC, that is, the transition between the Neolithic and the Bronze Age in England (Pryor 2001). The upside-down construction arouses immediate associations both with Snorri’s description of Yggdrasill and its one root in heaven and with other examples of the arbor inversa in Sámi, Siberian, and Indian traditions. As a contrast to the early Seahenge, there are also modern records of posts as symbols of the world axis, both from the Sámi of north Scandinavia and from central and northern Asia (Holmberg 1922–3). In certain parts of Siberia almost every farm had a post with an image of a bird at the top. The bird, which often symbolized an eagle, was often placed on a special little platform on top of the pole. The posts were often square in cross-section and were sometimes decorated with seven or nine grooves to mark the different worlds that surrounded the world tree. It is also worth noting that the sky-post, among the Sámi and certain ethnic groups in Altai, was supposed to be raised obliquely (de Vries 1957:388), which can be associated with Heimdall’s by-name as the ‘leaning’ log or staff.

Archaeologically speaking, posts as representations of trees are a potentially copious type of source material, but they are difficult to interpret, above all in the form of post-holes. Only through context can ordinary posts be distinguished from special posts. The post on Helgö is just one such example where the context clearly marks its special status. There are presumably similar archaeological examples that might be noticed in the future.

Another form in which trees are represented is in images. In Scandinavia there are no explicit pictorial motifs of trees until the rock carvings of the Bronze Age and the Early Iron Age. However, images of trees are uncommon, as is clear from the fact that Østfold and Bohuslän, despite their high density of rock carvings, have only about twenty examples (Hygen and Bengtsson 1999:118–19). The question whether these pictures represent an idea of a world tree is difficult to answer, especially since it goes together with the larger problem of the general meaning of the rock carvings (see, for instance, Kaul 1998, 2004; Goldhahn 1999; Hauptman Wahlgren 2002). The only thing that might indicate cosmic trees are certain features in the depiction and composition. All the rock images of trees seem to depict coniferous trees, probably spruce or yew, and a possible background for this selection is that coniferous trees were uncommon during the Bronze Age. Therefore, they were perceived as very special – evergreens in a landscape otherwise dominated by deciduous trees with vegetation that followed the changing seasons. Some images, moreover, show a standing person at the top of the tree, a motif with direct contemporary parallels in central Europe (Hygen and Bengtsson 1999:118–19). A few rock carvings also depict a capercaillie or black grouse sitting at the top of a tree. These pictures arouse associations with the cocks in the ‘gallows tree’ and in Mimameid. In short, although trees seldom occur in rock carvings, the petroglyphs do not seem to depict just any tree; these are trees with distinctive characteristics and special associations with humans and birds.

For the Iron Age, pictorial representations of trees are likewise not common. They are mostly confined to motifs on Gotlandic picture stones, textiles from the Oseberg grave, and the Överhogdal tapestry. But these images give a clearer impression of being representations of mythological trees than the earlier rock carvings. Scenes with people hanging in trees occur on the picture stone from Lärbo Stora Hammars (Fig. 12) (c. AD 800, see Andrén 1993) and on one of the Oseberg tapestries (c. AD 830). The motifs arouse associations not only with Odin hanging himself in ‘the windy tree’, but also with the hanging victims at Gamla Uppsala described by Adam of Bremen (Solli 2004; Sundqvist 2004, 2010; Warmind 2004). As I will discuss in Chapter 4, the image of a tree on the large Gotlandic picture stone from Sanda (c.400–550) in particular can be pointed out as a possible depiction of the Old Norse world tree (see Fig. 47).

A possible more formalized tree representation is the mushroomshaped image, to which I will return in Chapter 4. It is a recurring image known between the Early Bronze Age and the Migration Period. This form is above all attested on bronze razors, rock carvings, and in the form of ceremonial axes from the Bronze Age. However, a gilded silver pendant from Vännebo in Västergötland (see Fig. 48; Salin 1904:157) as well as the form of the Gotlandic picture stones (see Myrberg 2005) also arouse associations with the earlier images.

To sum up, pictorial representations show that the tree played a certain part in the human conceptual world, at least from the Bronze Age onwards. But it is not until pictures from the fifth century onwards that we find associations with mythological and ritual trees in the form in which they are known from Old Norse sources. These images of trees, moreover, are so few that it is not possible to perform any detailed spatial or chronological analyses.

Figure 12. A person hanging from a tree. Detail from one of the picture stones from Stora Hammars in Lärbro on Gotland, now in the open-air museum in Bunge. (Photo by the author.)

The third form of tree representations, and the one best suited for an archaeological study of the world tree idea, comprises monuments built of earth or stone. The classical example of this form of representation is the ‘Jupiter columns’ erected in the Roman period, above all in the southern Rhineland (Fig. 13). The columns are sometimes covered with oak leaves and crowned with a figure of Jupiter, and they often include symbols of the compass points and winds. The columns can be perceived as Roman interpretations of sacred Celtic oaks, and thus hybrid forms of Roman and Celtic religion (Müller 1975; Bauchhenss and Noelke 1981).

In Scandinavia, I believe that similar representations of trees should be sought among Iron Age graves, especially among those with a geometrical exterior in the form of circles, rectangles, triangles, and pointed ovals. The varied grave forms have attracted attention for a long time, but the different external shapes have primarily been used to give general datings for graves and cemeteries (Ambrosiani 1964; Hyenstrand 1974). Scholars have also assumed that the characteristic geometrical forms had different symbolic values (for example, Hyenstrand 1984; Bennett 1987), but relatively few have focused on the specific meaning of the shapes. Grave forms which have been examined from this perspective include stone ships (Crumlin-Pedersen and Munch Tye 1995; Artelius 1996), certain barrows (Zachrisson 1994; Johansen 1997), and stone circles (Bergström 1979).

Figure 13. Partially reconstructed Jupiter column, standing in front of the Römisch-Germanisches Museum in Mainz. (Photo by the author.)