CHAPTER 4

Whirls, horses, and ships

Solar aspects of Old Norse religion

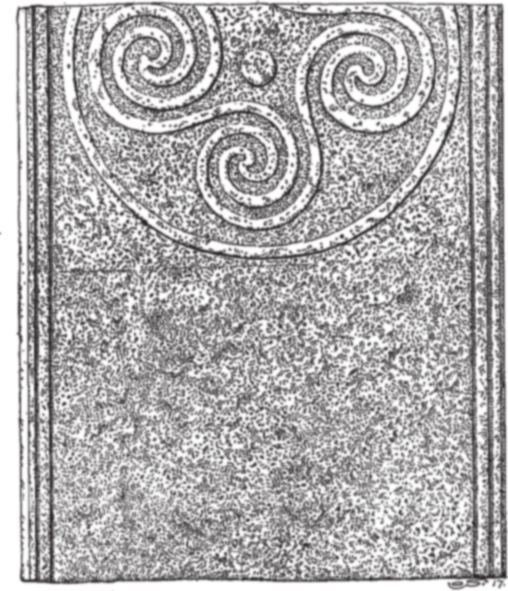

Ever since 1902, it has been clear that Scandinavian religion in the distant past was sun-oriented. That year, several extraordinary bronze objects were found in a bog outside the village of Trundholm in northern Sjælland. It turned out that they could be put together to form a carriage of six wheels, with a partly gilded bronze disc drawn by a horse placed on the carriage (Aner and Kersten 1976). This motif of a horse drawing a sun-disc with a string from its neck is also known from contemporary bronze razors and rock carvings. These recurring solar images show how the sun played a central mythological and ritual role in the Bronze Age. It is much more uncertain whether Old Norse religion in the Iron Age had a similar solar orientation, or if the importance of the sun disappeared at the end of the Bronze Age or vanished gradually. Some aspects of a solar motif were nonetheless clearly still known 2,600 years after Trundholm, since some of the lays in the Poetic Edda and Snorri Sturluson in his Edda mention how the sun and the moon are drawn by two horses over the sky, and how the personified day and night ride over the sky after horses. However, in the Icelandic tradition these celestial phenomena are reduced to faint figures without any role in the mythological narratives. Somewhere between Trundholm and Reykholt the sun lost much of its ritual, mythological, and narrative importance, but it is not known when and why.

Early picture stones on Gotland

I will reconsider the changing solar aspects of Old Norse religion, starting midway between Trundholm and Reykholt, with the early picture stones on Gotland. They are part of an extraordinary pictorial tradition on the island, which can be followed over nearly a millennium. About 475 picture stones with different designs were erected on Gotland from the Early Iron Age until about 1100. Above all, the large monuments from the early Viking Age (750–900) have attracted scholarly attention for a long time. They are covered with vivid images, which have been linked to motifs in Icelandic myths and heroic narratives, for instance Odin on his eight-legged horse (Lindqvist 1941), the smith Volund (Vǫlundr) (Buisson 1976), and scenes from the Volsung cycle (Andrén 1993; cf. Staecker 2004).

The early picture stones have attracted less interest, because they are much more formalized (but see Guber 2011). These monuments contain fewer, and less vivid images, which are repeated over and over again. Above all, the stones are covered with large whirls, ships and antithetical pairs of smaller spirals, horses, riders, warriors, and snakes or dragons. Ever since Sune Lindqvist’s large corpus Gotlands Bildsteine (1941–2), the early picture stones have been assumed to be grave markers, because lower parts of such stones as well as ornamented kerbstones have been found in graves. The monuments have been dated on stylistic grounds to the Migration Period – the fifth century and the first half of the sixth century AD. Due to this early dating, the images have been regarded as more difficult to interpret, being much more remote from the Icelandic tradition than the later monuments.

The round central figures on the early stones have in general been understood as sun representations. Already in the early twentieth century, Gabriel Gustafsson and Fredrik Nordin interpreted the large whirl at the top as a sun symbol and the ship at the bottom as a death ship (Lindqvist 1941:91). Lindqvist, however, was very hesitant in his interpretation of the early picture stones in his corpus. He argued that the round geometrical figures were perhaps depictions of shields. His main argument against Gustafsson and Nordin was that whirls, spirals, rosettes, and other figures on the Gotlandic stones actually occur in early Christian art in southern Europe at the same time (Lindqvist 1941:91 ff.). Hilda Ellis Davidson returned to solar interpretations of the early stones, with extensive chronological and geographical comparisons. She also understood the main round image to be the sun and the ship a ship of the dead (Gelling and Davidson 1969:139 ff.). Later on, she modified this idea in an interpretation of the complete stone from Sanda, which she saw as a representation of the Nordic cosmos. Davidson proposed that the large whirl was a symbol of the turning cosmos, whereas the two smaller spirals were the sun and the moon. A tree on a horizontal line she interpreted as the world tree, a creature underneath as a serpent of the depths, and a ship as the surrounding ocean (Davidson 1988:168 ff.). Since then, no one has tried to interpret the early Gotlandic picture stones systematically. Many scholars have accepted the idea of the sun and a ship of the dead (Nylén and Lamm 1978:15, 22; Althaus 1993; Andersson 2001), sometimes putting the images in a Celtic context (Görman 1998). Others have interpreted single motifs, above all a dragon and a man (Nylén and Lamm 2003:30 ff., 186; Raudvere 2004; Myrberg 2005; Ney 2006; Ragnarsson 2011).

Although Lindqvist has a point about the early Christian parallels, he does not take into account that the form and the Christian content of the models did not necessary follow each other. Late Roman and early Christian models might well have been incorporated into local non-Christian contexts in a process of hybridization. Since most of the large whirls and some of the smaller spirals have very distinct small rays at the rim, which the Roman models do not have, I still find it worth exploring the idea of sun representations. Seventy years after the publication of Lindqvist’s corpus there are also other good reasons for re-investigating the early picture stones. New finds point to a necessary revision of the chronology. The new dating consequently leads to new contexts and also opens up a new discussion of both contemporary parallels and older models.

New contexts

When excavating the large burial ground Barshaldershed on southern Gotland in 1984, Peter Manneke found a cremation grave with the lower part of an erected stone still standing in the middle. Judging from the finds, the grave can be dated to AD 200–350. A similar grave, with a lower part of an erected stone, was excavated as early as the late nineteenth century at Bläsnungs in Väskinde, north-western Gotland, giving an even earlier date of AD 100–250 (Manneke 1984). It is not totally clear whether these erected stones had carved images, but they mark the beginning of limestone slabs being erected as grave markers.

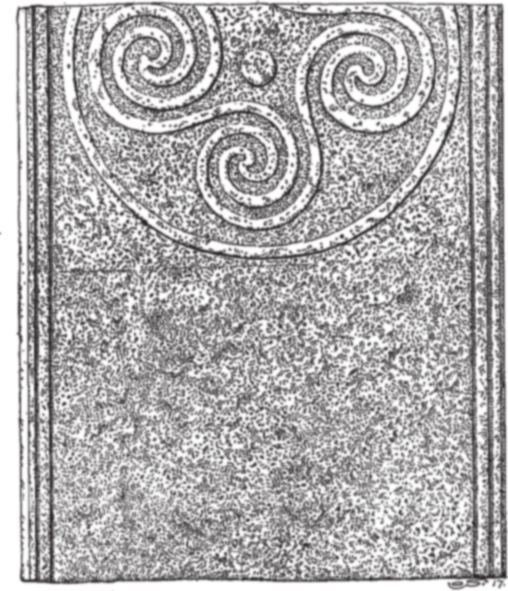

The possibility of an earlier start for the first picture stones actually fits well with the design and decorative elements of some early monuments. The overall design of some of the early picture stones, such as Stenkyrka Kyrka I (Lindqvist 1942, fig. 490), bears some resemblance to the so-called swastika fibulas from the third and fourth centuries (Fig. 39). Besides, some of the round figures on the early stones are not whirls, but rosettes with ‘leaves’ or figures with geometrical pleated and interlaced patterns. Such motifs are known from picture stones from Ire in Hellvi (Lindqvist 1941, figs 1–2), Burs (Lindqvist 1941, fig. 21), and Tofta (Lindqvist 1962). These motifs have good parallels in metalwork from the third and fourth centuries, such as bronze fittings found in the weapon deposits in present-day Denmark (Jørgensen et al. 2003). These links indicate that the early picture stones were erected during a longer period than Lindqvist suggested, probably from the third to the sixth centuries.

A consequence of the longer chronology is that the early picture stones can be placed in a much more prolific social context. They were part of new ‘stone enclosure communities’ (Sw. stengrundsbebyggelse), established on the island from the second and third centuries AD. These communities consisted of houses with stone foundations (Sw. stengrundshus) as well as stone enclosures (Sw. stensträngar) framing fields and meadows. Even today, more than 1,800 houses and large areas of deserted fields with stone walls are still preserved on the island (Nihlén and Boethius 1933; Stenberger and Klindt Jensen 1955; Carlsson 1979). Some of the ringforts on Gotland, such as the enormous Torsburgen with its perimeter of over 4.5 kilometres, also date from the same time (Engström 1984). Besides, distinct features of this expansive period are the Roman objects found everywhere on Gotland. They include bronze vessels, coins of silver and gold, and even terra sigillata pottery (Lund Hansen 1987; Lind 1981, 1988; Herschend 1980; Fagerlie 1967).

Lindqvist, and later Holmqvist, pointed to Roman gravestones and Roman mosaics as models for the design of the whirls and spirals (Lindqvist 1941:91 ff.; Holmqvist 1952). Davidson later gave further examples of Roman models, such as an altar with whirls and rosettes, found at Hadrian’s Wall in northern England (Gelling and Davidson 1969:144). A longer chronology of the early picture stones, starting possibly in the third century, would help to give a much better understanding of the proposed Roman models for these monuments. They can be viewed as just one of many cultural traits in Scandinavia that had a Roman background.

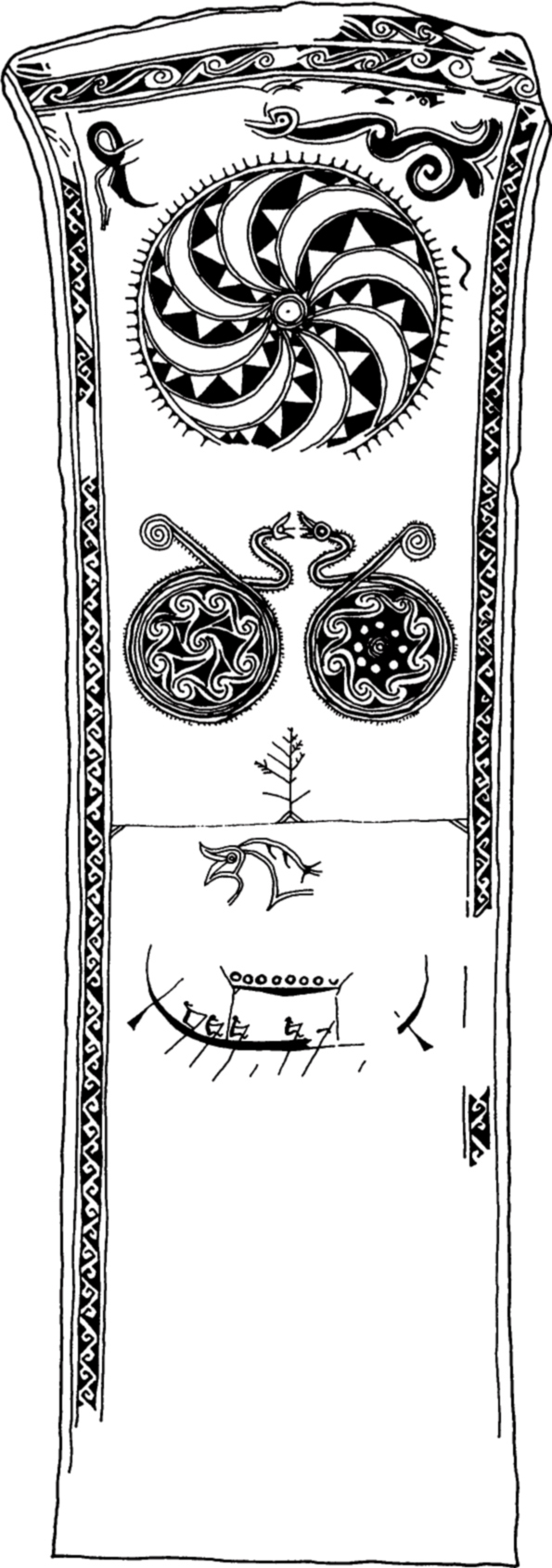

Figure 39. Picture stone from the church at Stenkyrka. This stone is an example of the first phase of the early picture stones, since the central figure has parallels with the so-called swastika fibulas from the third and fourth centuries. (Drawing by Olof Sörling in Lindqvist 1942, fig. 490.)

Although the early picture stones from Gotland are the best-known Scandinavian pictorial monuments from AD 200–550, they are not unique. In Uppland and Södermanland, around 25 small picture stones with similar images are known (Lindqvist 1941:30 ff.; Ahlberg 1978; Hamilton 2012). Usually they only contain one or two images of a whirl, a spiral, a ship, or two horses and warriors. They were grave markers, as on Gotland, and in one case, at Rällinge in Södermanland, the picture stone still stands on top of a small barrow. These small picture stones are part of a similar expansive period, above all in Uppland, where large houses were built on terraces, stone enclosures were erected around infields, and several Roman objects have been found (Lund Hansen 1987; Olausson 1997; Andersson 1998).

Closer parallels to the Gotlandic pictures stones may also have existed on the neighbouring island of Öland. Large limestone slabs are still standing today in many burial grounds on Öland. In contrast to the Gotlandic picture stones, however, no figures were cut or carved on the slabs, but instead the smooth show sides of the slabs were probably painted with images similar to the pictures on Gotland (Fig. 40). The limestone slabs on Öland can be put in a very similar context to the picture stones on Gotland. They were grave markers raised in a period of expansive settlement, in which houses were built on stone foundations, long stone walls enclosed fields, distinct ringforts were constructed and many Roman objects were deposited (Stenberger 1933; Fallgren 2006; Andrén 2006; Fargelie 1967; Lind 1981, 1988; Herschend 1980; Lund Hansen 1987; see also the previous chapter).

Figure 40. Two upright limestone slabs at Ottenby in Ås on Öland. This type of limestone slab are common in burial grounds on Öland, and they usually have smooth show sides facing north. (Photo by the author.)

The Roman background of the design of the pictorial monuments, especially in eastern Sweden from the third to the sixth centuries, fits well with Roman connections in general during that time in southern Scandinavia. However, the Roman background of the style of the figures does not necessarily give us a better understanding of the iconography of the early picture stones. In order to reach possible interpretations of these monuments, one has to move beyond style to investigate the content of the images, beginning with the pictorial structure.

An initial pictorial analysis

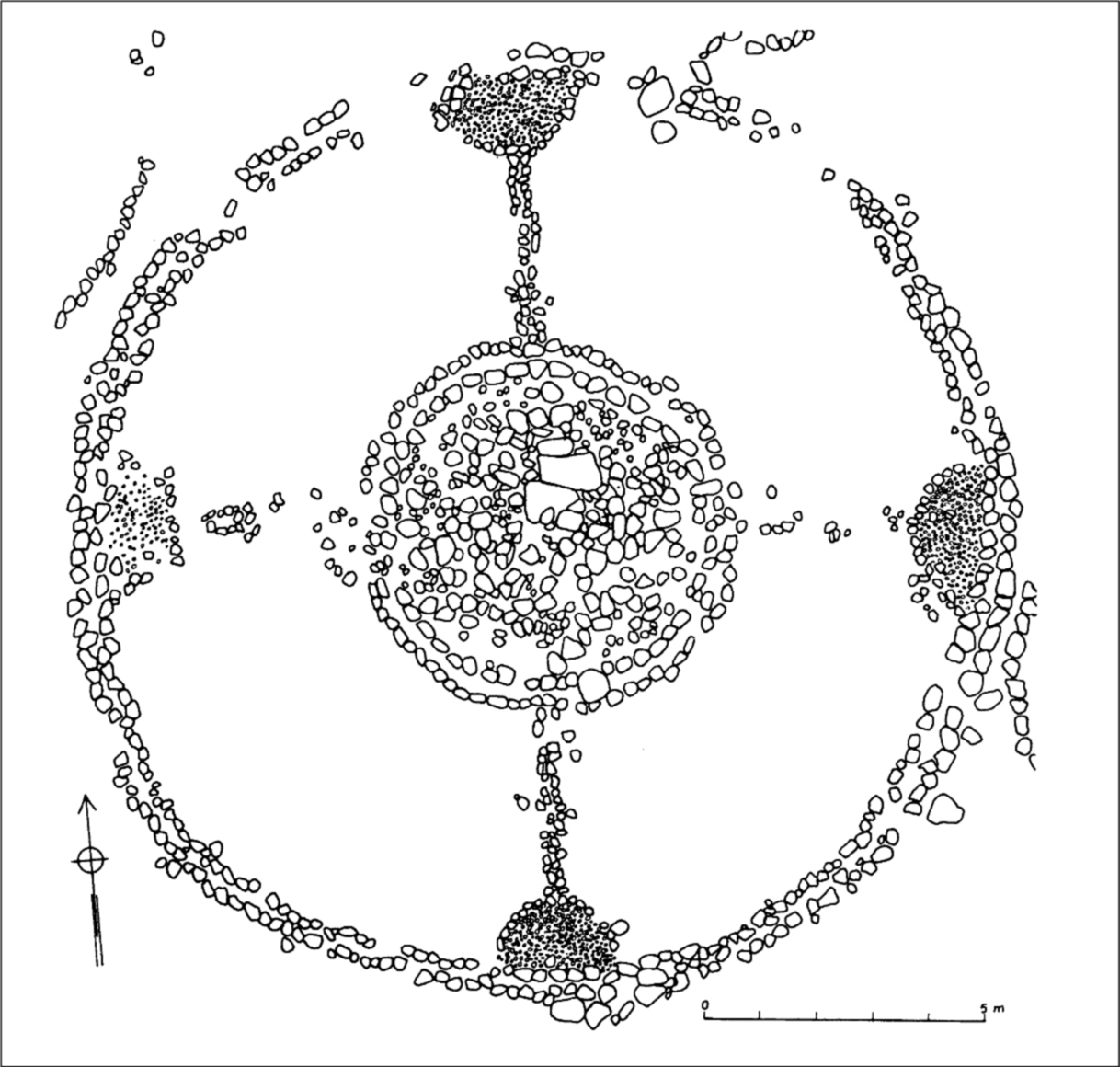

According to the latest survey, around 70 early picture stones are currently known from about 35 locations on Gotland (Nylén and Lamm 2003:177 ff.). Not one has been found in its original place, and more than half of the monuments have been found in medieval stone churches from the twelfth, thirteenth, and early fourteenth centuries (see Fig. 38). Many of the picture stones were probably still standing as grave markers in the burial grounds until that time when they were incorporated into the fabric of the stone churches. In several cases these parish churches are located near very large burial grounds, where the monuments were probably originally erected. The earliest stones were placed in the centre of graves surrounded by rectangular frames of stones (Manneke 1984). Later, the stones instead formed part of large round cairns built up with dry-stone walls. The upper edges of these walls sometimes had stones with cut decoration, such as lines and spirals (Lindqvist 1942:118 ff.).

The early picture stones varied considerably in size. A few very tall stones can be estimated to have had a height of between two and a half and four metres, and most of them have been found along the west coast of Gotland. Smaller stones had a height of no more than one metre, and were erected in all parts of the island (Nylén and Lamm 2003:177 ff.). The large stones usually contain more images than the smaller ones, and consequently are better suited for analysis of the pictorial structure. Most stones are in fragments, since many of them were broken into pieces to fit into the fabric of the medieval churches, but nevertheless the images on the different fragments fit into an overall structural pattern. The formal interpretation of the different images is not totally clear. The recurring geometrical figures are usually distinct enough, whereas the smaller accompanying images can be more problematic, due to the uneven preservation of the surface of the stones. For instance, on a stone from Vallstena, Lindqvist interpreted two figures as horses with their heads bent backwards, but these figures have later been reinterpreted as two armed riders (Arrhenius and Holmqvist 1960). This means that the overall pictorial pattern is fairly unambiguous, whereas the single image can sometimes be more problematic.

The basic structural pattern of the stones comprises a large round figure at the top, two antithetical smaller figures in the middle, and a ship at the bottom. Above the large round figure, animals or humans a B c are often antithetically placed (Fig. 41). This pictorial pattern is best illustrated by the stone from Sanda, which is the most complete monument of the large stones, measuring fully 3.3 metres. The stone consists of two parts, which were found around 1900 and 1956 respectively (Lindqvist 1962). It has all the main and supplementary elements of the recurring pictorial structure.

Figure 41. Pictorial structure of the early picture stones, demonstrated by five stones from Ire in Hellvi (A), the church at Martebo (B), the church at Sanda (C), the church at Bro (D), and Vallstenarum in Vallstena (E) (photos A–D by the author and E by Bengt A. Lundberg, Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm). Compare also Figs. 39, 50 and 54.

The recurring large round geometrical figure is known from about 45 stones. In most cases, this figure is a whirl, but in two early cases it is a rosette or a pleated round figure, and in three late cases it is a complex knot. On some smaller stones the whirl is the only image, whereas on most large stones it is accompanied by other figures. The configuration may differ between the stones, but they all follow the same structure.

In eleven cases, there are various creatures above the large whirl. These can include snakes, dragons, animals with horns, armed riders or three-pointed geometrical figures. In one case, a man seems to be placing his hand in the mouth of a multi-legged dragon (see Fig. 54). Beneath the large whirl on twenty stones appear a pair of antithetical figures, either round geometrical figures or humans or animals. In fifteen cases, the images are round geometrical figures, and most of them are spirals, but early rosettes and late knots also occur. In half of the cases, the small spirals end with animal heads and tails or are surrounded by a snake. In seven instances, the antithetical images are pairs of warriors, armed riders, horses, or, in one case, snakes. The riders and warriors have round shields with the same pattern of whirls and spirals as the round figures. Normally, only one pair of antithetical figures is depicted on a single stone, showing that two round figures could be replaced with two warriors, riders, or horses. This in turn, indicates that the figures represented some form of transformation.

Beneath the antithetical pairs, a horizontal line or a horizontal pleated zone is found on five stones. In one case, on the stone from Sanda, a small tree is standing on the horizontal line, accompanied by some kind of monster below the line. At the bottom of eight stones is a ship, with varying relations to the images above. The ship can be placed beneath the horizontal line/zone or the antithetical pairs, or even directly beneath the large round geometrical figure. The ship is always being rowed to the left, and it has steering oars in the stern as well as in the bow.

The pictorial pattern of the early stones is thus conspicuously uniform, although the different elements are not totally understood. The compulsory large round figure can provisionally be interpreted as a sun representation because of the common rays around the rim, but the other figures are much more difficult to grasp. In order to get a better understanding of the early stones, it is necessary to make several comparisons, chronologically and geographically.

A return trip to Bronze Age iconography

A good starting-point when comparing the early picture stones is the sun-chariot from Trundholm (Fig. 42). As mentioned earlier, the carriage is a ritual object, incorporating the disc and the horse as a mythical representation. The disc and the horse were originally connected by a string or a chain, creating a sun-horse. One side of the bronze disc, the one that is visible when the horse is seen drawing the disc from left to right, is gilded, whereas the other side is not. Ever since the discovery, the gilded side has been interpreted as the day-side, showing how the sun was seen as being drawn across the sky from east to west by a horse, whereas the ungilded side has been understood as the night-side, showing how the horse pulled the invisible sun back through the sky or through the underworld from west to east (Kaul 1998, 2004).

The sun-horse from Trundholm is clearly part of a broader Scandinavian pattern. A more fragmented find, with two similar horses, comes from Tågaborg, in north-western Skåne. A possible sun-chariot, although without the disc, has also been found at Järfälla, north-west of Stockholm (Victor 2007:163 ff.). Several sun-horses, including the connecting string, are depicted on rock carvings in Bohuslän and on bronze razors in Denmark as well. Some of these images are more recent than the Trundholm find, dating to the period 1100–500 BC. However, the solar representations during the Bronze Age include other elements as well, which is most evident from recent studies by Flemming Kaul (1998, 2004). His detailed investigations of sun symbolism are inspired by earlier works by, among others, Ernst Sprockhoff (1954) and Peter Gelling (Gelling and Davidson 1969).

Figure 42. The sun-chariot from Trundholm in north-west Sjælland. (After Aner and Kersten 1976.)

Kaul bases his study on a very thorough analysis of the images on about 420 bronze objects, mostly from the Late Bronze Age (1100– 500 BC) that have been found in present-day Denmark (Kaul 1998). The images are preserved above all on asymmetric razors, but also on neck-rings and other objects such as knives and tweezers. Sometimes, he also includes pictures from objects found in present-day Sweden, Norway, and northern Germany in his analysis. Recurring images on these objects are one or several ships, which are sometimes combined with circles, horses, mushroom-shaped figures, fishes, snakes, birds, and occasionally humans. This pictorial world is clearly transformative, including snake-horses, and ship stems with human heads, heads of horses, snakes, birds, and mushroom-shaped figures (Kaul 1998:188 ff.; 2004:271 ff.). Apart from the ship, the most frequently recurring image is the circle. Kaul interprets the circle as a symbol of the sun, because it sometimes has rays and sometimes is connected with a horse, creating a sun-horse like the figure from Trundholm (Kaul 1998:195, 2004:352).

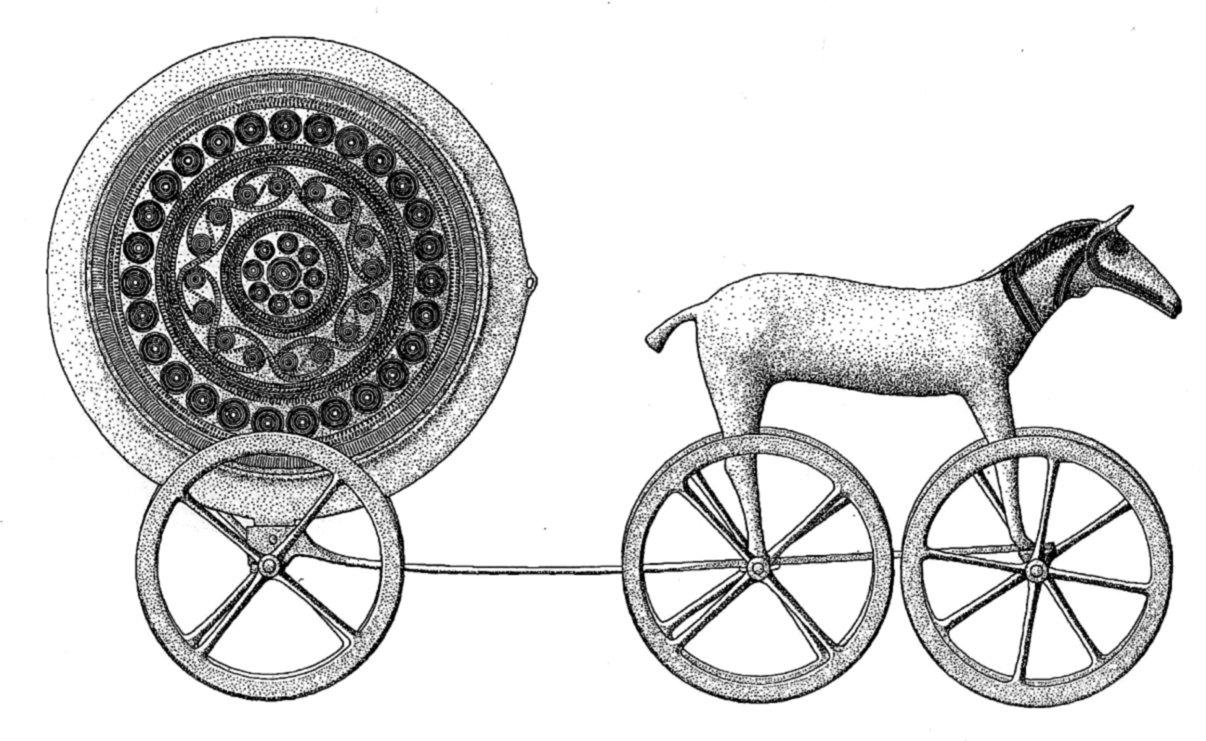

Kaul makes a fundamental distinction between the ships based on their direction of travel, and the images combined with ships sailing to the right or the left. This division offers a parallel to the day-side and the night-side of the disc from Trundholm (Kaul 1998:165 ff.). Since all circle motifs and all pictures of sun-horses are connected to ships travelling to the right, Kaul interprets these ships as images of ‘day-ships’, transporting the sun across the sky from sunrise in the east to sunset in the west. Consequently the ships travelling to the left are interpreted as images of ‘night-ships’, passing through the underworld from sunset in the west to sunrise in the east. The mushroom-shaped figure appears only with day-ships and the sun. The snakes, birds and fishes are more ambivalent in their connections to day-ships and night-ships, and are therefore regarded as helpers of the sun at critical transitions, such as sunrise, zenith, and sunset. Kaul argues that all these images represent a solar myth in Scandinavia from the Late Bronze Age (Kaul 1998:257 ff., 2004:241). The sun-horse of Trundholm, as well as early mushroom-shaped figures and fishes, shows that this myth existed already in the Early Bronze Age, although in a slightly different version. In the Late Bronze Age, aquatic birds, snakes, and ships as the main means of transport were introduced into narratives about the eternal journey of the sun (Fig. 43).

Although Kaul reckons on other myths too (Kaul 2004:183 ff.), he regards the solar myth as the fundamental narrative of the Scandinavian Bronze Age. He is, however, very reluctant to acknowledge anthropomorphic gods and goddesses, since very few humans are depicted on bronze objects (Kaul 2004:341 ff.). Instead he interprets most bronze figures and human images on rock carvings as different representations of rituals. Only a few human figures with solar rays around their heads that appear on bronze objects from the end of the Bronze Age are regarded as possible personifications of a solar god or perhaps divine twins, the Dioscuri (Kaul 1998:55 ff., 249 ff., 2004:80). This idea has since been developed by Kristian Kristiansen and Thomas Larsson (Kristiansen and Larsson 2005:262 ff.), who, following other scholars, also interpret the recurring ‘pair motif’ in figures and objects as expressions of divine twins (Krüger 1940–2; Althin 1945; Sprockhoff 1954; de Vries 1957:244 ff.; Fredell 2003; Kristiansen and Larsson 2005). The earliest double male figures, originally probably with horned hats, come from Stockhult in northern Skåne and are dated to 1500–1300 BC (Fig. 44). In a later version from Grevensvænge in Sjælland, the male pair have horned helmets and large axes, whereas the men from Fogdarp in central Skåne have horned helmets with bird beaks. On a razor from Vestrup Mark in northern Jutland a pair of men, and another accompanying man, are depicted with horned helmets and lurs. Similar pair motifs are also known from the large cairn at Kivik and rock carvings in Bohuslän. Since the pair motif is connected with the ship on the razor from Vestrup mark, it is argued that ideas of divine twins may have been part of the solar myth (Kristiansen and Larsson 2005, cf. Kaul 2004:345).

Figure 43. The solar cycle in the Bronze Age, according to Flemming Kaul. (After Kaul 1998:262.)

Figure 44. Two standing men from Stockhult in Loshult in Skåne. The two figures are dated to the fifteenth or early fourteenth centuries BC, and are a good example of the recurrent pair motif during the Bronze Age. (Photo by Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm.)

According to Kaul, the fundamental solar myth was also related to rituals. Some of the images on the bronze objects are placed in ritual contexts on rock carvings, for instance humans holding sun-symbols, bearing ships or mushroom-shaped figures (Kaul 2004:73 ff.). Other images, such as ships, horses, and wheel-crosses are also known from ritual contexts as parts of graves. In the spectacular graves at Kivik in Skåne and at Sagaholm and Hjortekrog in Småland, the images have been carved on specially made slabs or directly on the rock (Kaul 2004:137 ff., cf. Randsborg 1993; Goldhahn 1999; Widholm 1998). Likewise, more humble stones with cut images have been found on or at several grave mounds in Denmark (Kaul 2004:156). Besides, several ritual objects known from the pictorial world have been found as deposited full-scale artefacts. These include ceremonial bronze axes with clay cores, bronze helmets with horns, and bronze lurs. A large imported bronze shield with a wheel-cross may also have been used as a sun symbol carried in rituals (Kaul 2004:352).

Kaul maintains that the mythologies and rituals surrounding the sun were important aspects of Bronze Age religion in Scandinavia. Although he takes into account regional ritual variations in this religion, he argues that the religious traditions were basically the same from the middle of Norway and Sweden to northern Germany, since the pictorial world and the ritual objects are found in all parts of this region (Kaul 1998:274). Within Scandinavia, he suggests that Bohuslän, with the most rock carvings and also the most varied images, should be framed in a Scandinavian context and not in a local context as it usually is (cf. Bertilsson 1987). Instead, he sees this region as a kind of holy district, perhaps visited by people from many different regions on prehistoric ‘pilgrimages’ (Kaul 2004:98, 281; cf. Kristiansen 2001). Kaul points out two central places around which many of the bronze-objects from the Late Bronze Age containing images have been found. These centres are Voldtofte in south-western Funen, with a large mound adjacent to an unusually large settlement, and Boeslunde in western Sjælland, centred round a probably holy mountain called Borgbjerg (Kaul 2004:87).

This reconstructed religion, according to Kaul, is not only limited to Scandinavia as a region, but is also confined to the Bronze Age, which he sees as a specific ‘solar age’ (Kaul 1998:273 ff., 2004:407 ff.). The earliest images and ritual objects connected to the religion can be attested at the transition between period IB and period II in the Early Bronze Age (that is, around 1500 BC) in southern Scandinavia. Following other scholars, Kaul maintains that a new religious tradition was created at that time, by a new elite that monopolized the important bronze supply (Kaul 2004:231, 369 ff.; cf. Sprockhoff 1954, Randsborg 1993, Kristiansen and Larsson 2005). Imported objects show that a group of people had contacts with central Europe (the present-day Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and Romania) through alliances and long journeys (cf. Kristiansen and Larsson 2005). Probably via this region, they had further indirect contact with the eastern Mediterranean, which was the origin of several of the models of the iconography, such as the ship, the mushroom-shaped figure, and the wheel-cross. By combining local elements with selected foreign models, the elite created a new, specifically Scandinavian religious tradition, according to Kaul.

At the transition to the Late Bronze Age, around 1100 BC, the rituals and mythologies partly changed again, with cremations now replacing inhumations, ship symbolism being used more than before, and snakes and birds being introduced into the iconography (Kaul 1998:53, 145, 274 ff., 2004:218). Kaul does not see these changes as a new religion, but rather as a social widening of a former elite religion. Inspiration for these changes came once again from central Europe (the present-day Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Hungary), although imported objects from around 900–800 BC also point towards present-day southern Germany, eastern France, Switzerland, and northern Italy. At the end of the Bronze Age, around 500 BC, the former pictorial world more or less totally disappeared, along with the bronze supply. Like several other Bronze Age specialists, Kaul envisages a profound religious change in direct relation to a collapse of the long-distance travel and alliances that had previously secured foreign bronze. He thinks that the old elite disappeared, and with it the religion that for a thousand years had explained and legitimized its claim to power (Kaul 1998:110, 2004:391 ff.; cf. Jensen 1997; Kristiansen and Larsson 2005).

However, from a landscape perspective the transition around 500 BC is not that dramatic. Instead, a continuity or gradual change from the tenth and ninth centuries BC to the first centuries BC can be attested for land use (Welinder et al. 1998:239 ff.; Arnberg 2007), settlements (Feldt 2005), henged mountains or stone-enclosed hilltops (Olausson 1995), and burials (Wangen 2009). Simpler artefacts, such as pins and needles, did not change very much between the Bronze Age and the Iron Age. These similarities have led Claus Kjeld Jensen to suggest in a recent chronological study (Kjeld Jensen 2005) that the great divide came not around 500 BC but rather c.200 BC.

Still, ritual practice clearly changed in the Pre-Roman Iron Age from about 500 BC, when pottery, animal bones, and humans began to be deposited in bogs (Becker 1971; Kaul 2003; Fischer 2007; Pauli Jensen 2009). In several cases there is a continuity of new ritual sites from the fifth and fourth centuries BC until the fifth century AD and later, for instance, at sites such as Ullevi in Östergötland, Kärringsjön in Halland, and Skedemosse on Öland (Nielsen 2005; Carlie 1998, 2009a; Monikander 2010). Due to these ritual patterns, Kaul reckons there were two fundamental religious changes, one about 500 BC, when the solar myth disappeared, and another around 500 AD, when he supposes that an ‘Æsir religion’ was established. Consequently, Kaul believes that Bronze Age religion has very little in common with Old Norse religion, although he is open for a few transformed elements, linking up with later periods, such as the snake motif (Kaul 1998:14). However, irrespective of these ritual changes, elements of a solar iconography can be traced in the Early Iron Age as well. Instead of disappearing, it seems as if the sun was placed in new ritual contexts, leading to redefinitions of its role.

Bridging the gap between Eskelhem and Sanda

At Eskelhem on western Gotland, a large deposit with horse bits and bronze fittings as well as a large bronze disc (Fig. 45) was found in 1866 (Montelius 1887). The bronze disc originated from central Europe, whereas some of the other objects came from south of the Baltic Sea (Larsson 1994:119–20). The deposit can be dated to the very end of the Bronze Age, around 500 BC. The disc, which for good reasons has been interpreted as a sun-disc, consists of five rings connected by many small spikes, giving an impression of many small rays, radiating from a wheel-cross in the centre. On one of the rings are two loops with four hanging bronze pieces of tin. At the top of the disc are three loops surrounded by two antithetically placed birds, similar to some of the birds in Kaul’s study. Judging by the loops, the disc must have been hung, either from the neck of a horse or from the shaft of a carriage making the dangling pieces of tin tinkle. This gives us an unusual illustration of a sun symbol in its functional, and probably ritual, context. A similar bronze disc has been found at Kurum in Tjust on the east coast of mainland Sweden. This disc seems to have been locally produced, showing that the motif was still actively used in Scandinavia (Goldhahn et al. 2012).

The sun-disc from Eskelhem, and its parallel at Kurum, represent the very end of Kaul’s proposed ‘sun age’, being a millennium later than the sun-disc from Trundholm, but still connected to horses. The main question here is whether it is possible to bridge the following centuries from the sun-disc at Eskelhem to the early picture stones on Gotland. The best-preserved early picture stone, from Sanda, was raised only five kilometres from Eskelhem, but about 900 years later. Davidson proposed some continuity between the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, but she based her studies on simple comparisons of images and symbols in time and space, without any considerations of context (Gelling and Davidson 1969:139 ff.) Nonetheless, bridging this gap between the two locations concerns not only traces of possible sun representations, but also issues of figurative expressions and questions of context.

Figure 45. The sun disc from Eskelhem, dated to c.500 BC. (Photo by Gunnel Jansson, Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm.)

The problem with discussing the division between the Bronze Age and the Iron Age is partly that there are few pictures from the Early Iron Age, and partly that the conventions of image representations changed. Much of the pictorial world that Kaul analyses actually disappeared at the end of the Bronze Age. Few figurative images are known from the end of the Bronze Age to the early Roman Iron Age, that is, 500 BC – AD 200. Those images that were created during these 700 years were nonetheless made according to other pictorial conventions from central Europe, first inspired by the Hallstatt culture, later by the Celtic world, and finally by early Roman models. This means that images have to be interpreted from their content rather than from their style.

Images from the earliest Iron Age (500–200 BC) can best be described as low-key expressions of Bronze Age origin, partly cast in new forms inspired by the Hallstatt culture in central Europe, such as the disc from Eskelhem. Kaul himself mentions that some rock carvings were still cut during this period in Bohuslän, Østfold, Trøndelag, Uppland, and Bornholm. A new motif in this final phase was the armed rider (Kaul 1998:87). This means that the rituals of cutting images on rocks survived in many parts of Scandinavia until the first centuries BC. Besides, new investigations of rock carvings have shown that rituals were conducted around the images long after the cutting itself had stopped. In some cases, it is possible to follow rituals at the site of rock carvings into the second and third centuries AD (Nilsson 2010). At Himmelstalund in Östergötland, an early runic inscription from the third or fourth centuries was even added to a rock with older rock carvings (Krause and Jankuhn 1966:121 ff.), showing a continued interest in or return to a historically important site. Kaul also points out that the Hjortspring boat from southern Jutland, dated to around 350 BC, seems to have had a ring as a sun symbol at the top of its stem, strongly resembling some of the ship images on earlier rock carvings (Kaul 1998:87 ff.).

Kaul, along with Kristiansen and Larsson, have convincingly argued that the wheel-cross was established as an alternative sun symbol already in the Early Bronze Age (Kaul 2004:352 ff.; Kristiansen and Larsson 2005:194 ff., 240 ff., 298 ff.). After 500 BC, the sun-motif was only represented in this formalized way, as more or less elaborate wheel-crosses or concentric rings, partly resembling the sun-disc from Eskelhem. Some bronze needles and pins had simple wheel-crosses at the top, whereas larger bronze buckles were designed as complex wheel-crosses with several rings, including small round discs. Another element of Bronze Age origin is the spiral, which was used to decorate some fibulas and pins (Nylén 1955; Arrhenius and Eriksson 2006). Some ritual aspects from the Bronze Age were also preserved during this period. Pairs of neck-rings were deposited in wetland, echoing the earlier twin motif (Kaul 2009). On Gotland, small ship-formed graves were still built for inhumations during the Early Iron Age. More or less complex wheel-crosses built from small stones were used as grave markers during the Early Iron Age in Norway (Wangen 2009) and eastern Sweden (Äijä 1999), as well as on Gotland (Nylén 1969; Arnberg 2007). Even the importance of the razor was preserved, since iron razors are known from Denmark, but without known or preserved images.

The following period from about 200 BC to AD 200, however, from a Scandinavian point of view is more or less aniconic, making it a pictorial ‘Dark Age’. There are some figurative objects, such as the overwhelmingly richly decorated silver cauldron from Gundestrup in Jutland, but due to its foreign origin it has very little to say about the Scandinavian pictorial world (Kaul 1991). At the same time, some locally produced objects have whirls, triskeles, and aquatic birds inspired by decorated objects from the Celtic world (Kaul 2009). Further, wheel-crosses, concentric rings, rosettes, and rings with elaborate spokes of different shapes were still used as grave markers in Norway, mainland Sweden, and on Gotland (Äijä 1999; Nylén 1969; Arnberg 2007; Fig. 46)

It is only in the third and fourth centuries that a more complex pictorial world of Scandinavian origin can be discerned again, now based on Roman models (Åberg 1925; Holmquist 1952). From that time, images occur on metalwork as well as on stones, the Gotlandic picture stones being the best example of this new pictorial world. Although the links between the picture stones and the iconography of the Bronze Age are thin, I would argue that there is a connection. Above all it is possible to see a continuity of solar images by going beyond style and by using different kinds of archaeological categories. A strong case for continuity on Gotland at least is that wheel-crosses, concentric rings, and rosettes as grave markers were now replaced by cut picture stones with rosettes and whirls.

Bronze Age perspectives on early Gotlandic picture stones

This long return trip to the Bronze Age has basically confirmed older interpretations of the images of the early picture stones as being related to the sun (Lindqvist 1941:91; Gelling and Davidson 1969:141 ff.; Davidson 1988:168 ff.). However, it has also given new insights, which can be used to help understand the images in new ways, as well as offering interpretations for some of the unexplained details of this pictorial world. The complete stone from Sanda is the best starting point for a new interpretation (Fig. 47). Its layout is surprisingly similar to Kaul’s reconstructed solar cycle, although a day-ship is lacking, showing that the symbolic importance of the ship has been downplayed since the Late Bronze Age. Like Davidson, I see this stone as a representation of the Old Norse cosmos, although we comprehend some important elements differently.

The large whirl on top of the stone corresponds to the sun at its zenith, whereas the two smaller spirals with animal heads represent the sunrise and the sunset, respectively. The motif can be directly compared with a rock carving from Askum in Bohuslän (Kaul 2004:277), where two sun-horses are standing in front of each other, with the day-side to the left and the night-side to the right. The ship travelling to the left underneath the horizontal line can best be understood as the night ship of the sun making its voyage through the sea or the rivers of the underworld. The tree standing on the horizon can be interpreted as a world tree standing in the middle of the world, around which the sun makes its daily tour in the sky and the underworld.

Figure 46. A grave in the form of a wheel-cross at Sälle in Fröjel on Gotland. The grave is dated to the early Roman Iron Age, c. AD 1–200. (After Nylén 1969:107.)

The adjacent figures on the Sanda stone and the other early stones should in some way be connected with the main solar cycle. They could be regarded as helpers of the sun at critical passages, as in Kaul’s interpretations, or as creatures threatening the sun during its daily trip around the world. Monsters or snakes above the large whirl, around the two smaller spirals, and below the horizontal line could be interpreted as sky monsters and sea monsters threatening the sun. Meanwhile, the warriors, riders, and horses, which sometimes replaced the small spirals below the large whirl, could be regarded as representations of sunrise and sunset, or as helpers of the sun at these critical transitions. The pair motif may also recall the idea of divine twins connected with the solar cycle. In this context, it is also interesting to note that the Dioscuri in the Baltic as well as the Greek and Roman traditions were associated with horses (Rosenfeld 1984; Simek 1993:59–60.).

Figure 47. Drawing of the picture stone from the church at Sanda, from c.400. This is the best preserved early picture stone on Gotland. (Drawing by the author.)

It is not surprising that the motifs on the early Gotlandic picture stones are so close to Kaul’s reconstructed solar myth, since iconographic continuity throughout the Early Iron Age is best attested on Gotland. Although the Gotlandic picture stones are comparatively unique, they should not be regarded as expressions of a regional tradition or a religious relict, since there are other contemporary expressions elsewhere in Scandinavia linked into the same pictorial world. Echoes of a similar solar iconography are present in the much smaller picture stones from Uppland and Södermanland. The whirls, spirals, rowing ship, armed rider, and antithetically placed horses and warriors here recall the Gotlandic images (Ahlberg 1978). Contemporary Scandinavian metalwork in bronze, silver, and gold includes aspects of the same iconography, but also extends the pictorial world to other motifs. In order to place the solar cycle of the Iron Age in this broader context, it is therefore necessary to have a closer look at some of the contemporary metalwork.

Metalwork in the Iron Age

The main large round figure on the early picture stones has direct parallels in metal objects from the same period. Some of the large whirls, such as the whirl on the picture stones from Atlingbo and Stenkyrka I, are designed like the so-called swastika fibulas. These fibulas date to the third and fourth centuries, and are found in female as well as male graves in Denmark, southern Sweden, Norway, Finland, and northern Germany (Lund Hansen 1995:214 ff.; see Gelling and Davidson 1969:140). The fibulas can be viewed as developed sun-wheels, with the four main positions of the sun marked out as small round discs at the end of the bent arms, namely sunset, midnight, sunrise, and midday with the sun at its zenith. Some large whirls on early Gotlandic picture stones also have clear parallels in other fibulas, such as a plate fibula from Ejersten in Vestfold, dated to the early fifth century (see Salin 1904:209; Lindqvist 1941:109) and the so-called shield fibulas from Denmark, Norway, and England, also dated to the fifth century (Magnus 1975:47 ff.)

Figure 48. A pelta-shaped gilded silver pendant, dated to the early fifth century, from Vännebo in Roasjö in Västergötland. The image on the pendant can be regarded as a counterpart in metal to the cosmological image on the Sanda stone (Fig. 47). (Photo by Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm.)