Another interesting link can be traced to mushroom- or pelta-shaped gilded silver pendants from Fulltofta in Skåne and Vännebo in Västergötland. Both pendants come from extraordinary deposits of horse equipment from the first half of the fifth century. These deposits have repeatedly been used to underline long-distance elite connections between south Scandinavia and south-east Europe, directly or indirectly linked with steppe-nomadic groups (Åberg 1936; Forssander 1937; Fabech 1991a; 2011; Bemmann 2007). The pendant from Fulltofta depicts a large whirl with three small circles on each side of the whirl and bird heads at the two ends, as a kind of abbreviated version of the Gotlandic solar cycle. The piece from Vännebo includes four representation of the sun (Fig. 48). The pendant as a whole can be interpreted as the world tree reaching to the sky as well as the underworld. On top of this tree is the sun at its zenith with long rays, flanked by two smaller suns representing sunrise and sunset. At the bottom of the figure is a sun with short rays, representing the sun passing through the roots of the tree in the underworld during the night. At the outer ends of the tree are animal heads, providing links with the antithetically placed figures on the early Gotlandic stones. From this perspective, the pendant from Vännebo can be regarded as a counterpart in metal to the complete cosmological image presented on the Sanda stone. Once again, it is interesting that the solar cycles from Fulltofta and Vännebo can be connected with horses and horse equipment, similar to the much earlier finds from Trundholm and Eskelhem.

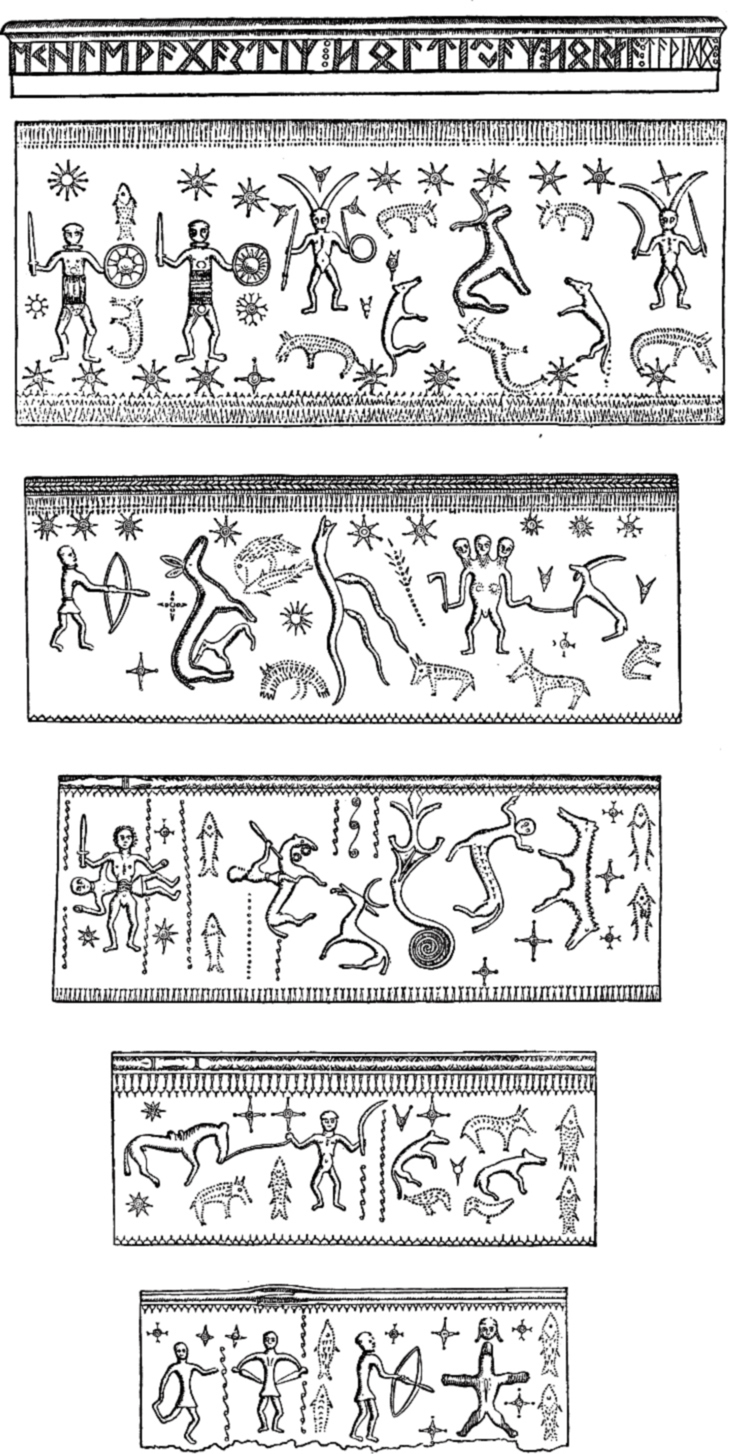

Figure 49. Drawing by J. R. Paulli in 1734 of the shorter of the two gold horns from Gallehus. (After Brøndsted 1954, table II.)

In addition to sun representations, the motif of pairs also reappeared in figurative metalwork. Two horned animals from Solberga on southern Öland have been found in a settlement dating from the third to the fifth centuries (Persson and Rasch 2001:373–4; cf. Fallgren 2008:132). Interestingly, a decorated ring at the withers of one of the animals can be interpreted as a sun symbol, recalling the sun-horse with a string connecting the sun with the neck of a horse (see Fig. 56). Twin motifs were also present on the enigmatic gold horns from Gallehus in Jutland from the fifth century. Many images on the horns are difficult to interpret, however, because the objects no longer exist and only are known from antiquarian sketches (Brøndsted 1954:64 ff.; cf. Oxenstierna 1956). According a drawing from 1734, the top panel of the shorter horn included two pairs of warriors, one with swords and shields, the other with spears, a shield, and a twig, as well as long horns on their heads. The two pairs of warriors were accompanied by one horned animal, eight small dog-like animals, and a fish (Fig. 49). This panel also included seventeen suns with six or more rays, more than any of the other panels on the horn. On the third panel of the short horn were another horned animal and a monster/snake with a coiling tail (Brøndsted 1954; Oxenstierna 1956). Otherwise the pictorial world of the Gallehus horns is quite different from the picture stones on Gotland, underlining the broad spectrum of possible images – and narratives – that seems to have existed also in the Iron Age.

A special case: the gold bracteates

Another iconographical connection existed, this time between the picture stones and gold bracteates. These gold pendants with stamped images on one side represented a pictorial world with a broader selection of images, but with several parallel motifs. Models for the bracteates were Roman coins and medallions, although the pictorial world of the bracteates was clearly changed in relation to the Roman models. Currently about a thousand bracteates and imitations of Roman gold medallions are known, primarily from Scandinavia, but also from Germany, Poland, Hungary, northern France, and England (Heinzmann and Axboe 2011). The gold medallions are usually dated to the fourth century, whereas the gold bracteates are dated from the mid fifth century to the early and mid sixth century (Axboe 2007:65–76). Owing to their coin-like character, the bracteates have been investigated in recurrent chronological studies from the mid nineteenth century (Malmer 1963:215 ff.; Axboe 2007; Behr 2011). Usually the bracteates are interpreted as protective amulets, but they may similarly have functioned as political gifts and signs of a claimed Scandinavian identity outside Scandinavia (Andrén 1991; Seebold 1992:307; Axboe 2007; Pesch 2007).

The iconography of the bracteates has also been a central issue since the mid nineteenth century. Basically, the images have been interpreted in three different perspectives: mythological, heroic, and political. As early as 1855 C. J. Thomsen proposed that the images represented some of the Old Norse gods, whereas Worsaae in 1870 suggested that some of the figures were heroes (Thomsen 1855; Worsaae 1870). Since the Roman models of the gold bracteates were coins depicting emperors, gods, and goddesses, other scholars have interpreted the pictures as ideal portraits of rulers (see Seebold 1992).

Today, the mythological interpretation totally dominates the debate, mainly due to the research by Karl Hauck and his colleagues and pupils (Hauck 1984, 1992; Behr 1991; Axboe 2007; Pesch 2007; cf. Gaimster 1998). However, the identification of specific Old Norse gods and goddesses is still disputed, mainly due to different methods in the iconographical analysis. Hauck’s ‘contextual iconology’ presupposes ideal models, which means that he reckons on broad variations of a very few distinct motifs, whereas some archaeologists instead underline the typological variations, which leads to many more distinct motifs.

Among the undisputed identifications are motifs of the sky god Tyr (Týr) putting his hand in the mouth of the wolf Fenrir (Öberg 1942; Oxenstierna 1956), and Baldr being killed by a twig of mistletoe (Hauck 1970). However, the commonest motif on the so-called C-bracteates, consisting of a horse or a horned animal with a human head at the neck of the animal (head-animal), is much more disputed (see Fig. 51). Since Thomsen’s study in 1855, many archaeologists have distinguished between head-animals with runes and birds, and head-animals without these characteristics, instead including a beard and horns on the animals. The first motif is interpreted as the rune-versed Odin with his ravens, whereas the second motif is believed to be Thor with one of his he-goats (Salin 1895:91; Malmer 1963:215 ff.). In a series of studies Hauck has criticized these interpretations as being incoherent, since the motifs are not mutually exclusive, with variants combining both motifs. Instead Hauck regards all variants as different forms of iconographical abbreviations of an ideal model. With references to the Second Merseburg Charm from the tenth century, he interprets the recurring motif on the C-bracteates as Odin curing the horse of Baldr by whispering in the ear of the horse. Hauck connects this interpretation of the motif with the function of the bracteates as protective amulets (Hauck 1992, 2011; overview in Pesch 2007).

Although Hauck’s interpretations have been widely accepted, they are not totally convincing, since he has based them mainly on classical and medieval texts and classical and Romanesque art, and to a much lesser extent on contemporary Scandinavian images, and especially the early picture stones from Gotland. It is well known that the picture stones and the bracteates share some common motifs. The bracteates have a broader range of motifs, but they are placed in less complex iconographical contexts. The more complex pictorial structure on the Gotlandic monuments may give new perspectives on the gold bracteates.

Among the parallel motifs are the quatrefoil knot, found on the picture stone from Havor in Hablingbo as well as on the double bracteate from Lyngby on Sjælland (Gaimster 1998:120). Another parallel motif is a triskele of three animals, represented on the picture stone from Smiss in När and on the double bracteate from Trollhättan in Västergötland. On the other side of the same bracteate is another link to Gotland, namely a man putting his hand into the mouth of a monster or wolf. Apart from the Trollhättan bracteate, the motif is known on other bracteates (Pesch 2007:123) and also the picture stone at Austers in Hangvar (see Fig. 54). The images on the bracteates as well as on the picture stone are, as mentioned above, interpreted as the sky god Tyr putting his hand into the mouth of Fenrir (Öberg 1942; Oxenstierna 1956; Ney 2006).

The disputed motif on the C-bracteates of a horned animal with or without a beard has several parallels, which have long been noted. Similar motifs are known from the picture stone at Häggeby in Uppland (Arne 1902:321 ff.; Gjessing 1943), from Gotlandic fibulas from the fifth century (Janse 1922:93; Öberg 1942:62), from one of the gold horns from Gallehus, and from several other Scandinavian sites (Oxenstierna 1956:44 ff.). Recently, the same motif was found in one of the high-ranking graves at Hagenow in northern Germany, dated to around AD 100 (Lüth and Vors 2001).

Figure 50. Picture stone from the church at Väskinde. Below the central whirl are two horned animals with beards. These horned and bearded animals have many parallels in the gold bracteates. (Photo by the author.)

However, it has not been noticed that the motif has an interesting parallel on the picture stone from Väskinde church (Fig. 50) found in 1955 (Lindqvist 1956). Below the large whirl and above the horizontal zone, two antithetical bearded animals are depicted, with some kind of flying figures close to their necks. As mentioned above, this image is connected with the common twin motif of spirals, horses, horned animals, or warriors, which I have interpreted as the sunrise and sunset or as the Dioscuri helping the sun at these transformations. A further argument for linking the image of the C-bracteates with these motifs is the appearance of the two horned animals at Solberga on Öland. The decorated ring on one of these animals is located at the same spot as the head of the C-bracteates, which indicates that a Roman model of a rider was reinterpreted as an already existing Scandinavian iconography of a solar animal with the sun at the mane or in a string from the mane.

Consequently, I interpret the disputed head-animals of the C-bracteates as a motif connected with the divine twins and the sunrise and sunset. Such a general context may explain the variation of the motif as well as the surprisingly uneven distribution of the direction of the animals (Fig. 51). Out of a total of 252 different images, the animals face left in 183 instances (73 per cent) and right in only 69 examples (27 per cent), according to the published corpus of bracteates (Hauck et al. 1985–9; Heizmann and Axboe 2011). This discrepancy cannot be explained by Hauck’s idea of a general variation of an ideal motif, but fits well with the idea that sunset – when the sun-horse or one of the twins is turning left – is the most critical part of the solar cycle. This is when the sun is entering the underworld, and a new day is beginning with the night, according to Old Norse time reckoning (see Nordberg 2006). A recurring motif connected with this fundamental and critical transition may also be linked with the protective aspects of the bracteates. Such an interpretation does not exclude a link with Odin, since some of the later motifs of the Dioscuri seem to have Odinic connections (see Hauck 1984; Magnus 2001a). However, the interpretation starts from a more general perspective and is less dependent on the Second Merseburg Charm as a specific and much later text.

Finally, another unnoticed link between the picture stones and the bracteates can be seen in the broad borders surrounding the central image on some bracteates. In contrast to the enormous efforts that have been put into chronological and iconographical studies of the bracteates, including the stamps of the borders (Axboe 1982, 2007; Wicker 1990), very little attention has been paid to the pictorial aspects of these borders. Only Carl-Axel Moberg (1953) has pointed to the star-like character of the pattern of some of the borders, because they consist of one or more zones with triangles and rays. Out of the total corpus of bracteates, about 325 have some kind of border, apart from the central motif and the rim (Hauck et al. 1985–9; Heizmann and Axboe 2011). The borders may consist of one to seven zones with points, circles, strokes, semicircles, spirals, crosses, wave lines, and triangles. Imitations of gold medallions from the third century, such as the finds from Inderøy and Svarteborg, already have star-like patterns around the central head. All types of the later bracteates have borders, but they are most common among the C-bracteates with an animal and a head. Only a small number of bracteates, about 40, have three or more zones, and all of these large bracteates come from Scandinavia, apart from two German finds (Fig. 52). Among these large bracteates, 26 have a central motif of an animal with a head at the neck, and in 24 cases (92 per cent) the figures are facing left. In only two cases (8 per cent) is the direction right.

Figure 51. Two gold bracteates from Åkarp in Burlöv in Skåne. These two bracteates represent the two possible directions of the animal and human head on the C-bracteates. In 27 per cent of the cases they are facing right and in 73 per cent of the cases left. (Photos by Ulf Bruxe, Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm.)

The star-like borders combined with human heads and sometimes horned animals can be linked to the antithetical figures on the Gotlandic picture stones, such as whirls, spirals, sometimes with heads and tails, warriors, armed riders, and animals. Due to this parallel, my interpretation is that the borders, or at least the borders with star-like patterns and several zones, referred to the sun and its rays. It is interesting that the solar aspects of the broad borders have a very pronounced connection with the animal and head facing left, which I have interpreted as an expression of the transformation around sunset. The star-like borders consequently underlined this important and critical transition as well as the idea of the divine twins.

Figure 52. An imitation of a Roman gold medallion from Senoren in Blekinge and a gold bracteate from Ravlunda in Skåne. In both cases the central figure is surrounded by a broad star-like border, which can be interpreted as sun rays. (Photos by Ulf Bruxe, Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm.)

Iron Age perspectives on early Gotlandic picture stones

This short comparison with contemporary metalwork shows that the images on the early picture stones on Gotland were firmly based in a common Scandinavian pictorial world. Different aspects of the solar cycle, such as the sun itself and the divine twins, can also be traced in three-dimensional figures, dress ornaments and bracteates. However, the solar cycle was not the only major motif, but co-existed with other motifs, such as Baldr and Tyr on the bracteates and the uninterpreted images on the horns from Gallehus. This indicates that the sun as a mythological motif coexisted with narratives connected with other mythological figures as well.

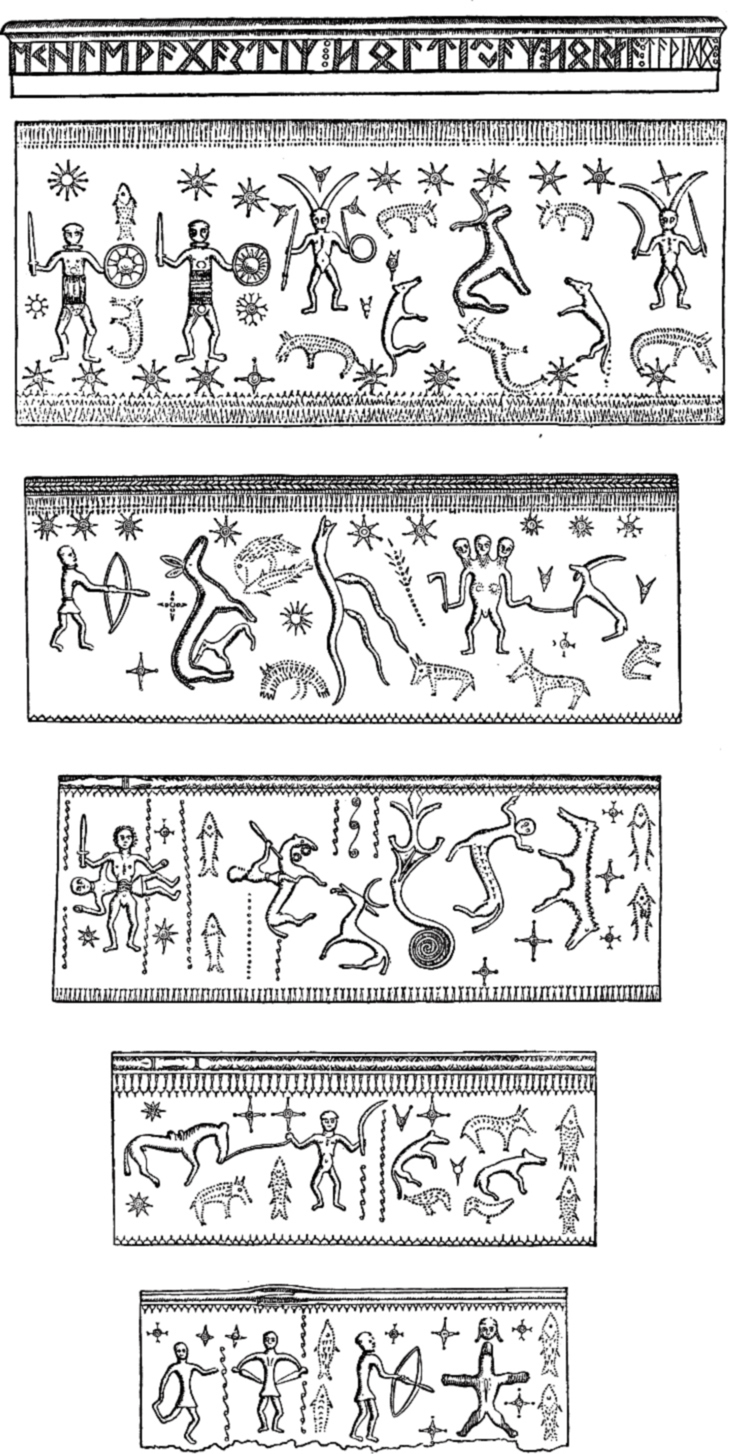

A similar pattern is indicated by the names of the runes. As is well known, each of the runic letters had its own name. The names are recorded in different continental manuscripts from the eighth and ninth centuries, but can be indirectly secured through the use of runes as concepts in inscriptions from at least around 600 (Nedoma 2003). The names probably go back to the invention of runes in the second century AD, since the order of runes has been unchanged since the first recorded runic alphabet in the fifth century, on a stone from Kylver on southern Gotland (Fig. 53) and on a bracteate from Vadstena in Östergötland (Nedoma 2003). The names were probably used as a mnemonic device to help in remembering the rune characters. For each runic character, a word was selected with the same initial sound value. Although the words for each character could have been selected from an enormous range, the final choice of the names points towards fundamental concepts which existed in the northern world in the second century AD. It is therefore interesting that we find rune names referring to concepts that can be directly or indirectly linked to the images on the Gotlandic monuments. The fundamental concepts in question include sun (*sowulo-), day (*daga-), water (*lagu-), horse (*ehwa-), man/human (*mann-), birch (*berkana-), and possibly elk (*algi-) (Nedoma 2006). Apart from these general concepts, the names of two gods also designated runes, namely the sky-god Tyr (*Teiwa-) and the chthonic god Yngvi (*Ingwa-), possibly linked to the later known god Freyr (Nedoma 2003). At least Tyr can be clearly linked with the solar cycle on the picture stone from Austers in Hangvar.

Figure 53. The runic alphabet from Kylver in Stånga on Gotland. This is one of the oldest recorded runic alphabets, and it is carved on a limestone slab that was part of a grave, probably from the first half of the fifth century. (Photo by Christer Åhlin, Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm.)

Another early example of the sun and its relation to other mythological figures is seen in the Germanic translations of the Roman names of the days of the week. The Germanic adoption of the Roman days of the week was probably completed in the fourth century. Through the names it is possible to see how the sun as a mythological figure coexisted with the moon, Tyr, Odin, Thor, and Frigg during this century, at least in the southern Germanic world, where the translation probably took place (Simek 1993:371).

Finally, the external views of classical authors point towards a similar pattern, with the sun being an important part of a broader mythological world. Tacitus in his Germania from AD 98 claimed that the main Germanic gods in general were Mercury, Mars, and Heracles, which have usually been equated with Odin, Tyr, and Thor (Tacitus 1999:42). However, when he is describing specific groups in the Baltic Sea region and in the far North, he actually mentioned the fertility goddess Nerthus, divine twins, and the sun. According to Tacitus, the Germanic tribe of the Naharnavali living south of the Baltic Sea worshipped the twin gods Alcis, which he directly equated with the Roman Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux (Tacitus 1999:59; cf. Simek 1993:240, 316, 337). The name Alcis probably means ‘elk’, associating the gods with horned animals (Vikstrand 2001:199 ff.). As noted, AlgiR (‘elk’) may have been the name of the a-rune in the futhark, giving further indications of Dioscuri in Scandinavia in the third and four centuries. Tacitus’ information may also be compared with that of the Greek historian Timaios, who as early as the third century BC reported that the ‘Celts’ along the North Sea coast were particularly devoted to the Dioscuri (de Vries 1957:247).

Tacitus also states that in the far North, beyond the sviones, is another sea at the end of the world, where ‘popular belief holds that the sound of the sun emerging from the sea can be heard and the shape of his horses and the ray of his head can be seen’ (Tacitus 1999:60; see de Vries 1956:355 ff.). Here, the connection between the sun and horses is mentioned in writing for the first time, although the motif had been known since the sun-horse of Trundholm. According to Tacitus, the sun in northern Europe was an anthropomorphic male figure with rays around his head. He had at least two horses that drew him across the sky. In this Roman interpretation, the sun was accordingly interpreted as a sun god, probably based on interpretative Mediterranean models such as Helios.

The parallels in metalwork, the names of the runes, and the days of the week as well as notices by classical authors clearly show that the early picture stones on Gotland formed part of a mental world that was in many ways common throughout the northern Europe during the Early Iron Age. The sun and the solar cycle with the divine twins were important parts of a broad mythological world, alongside other divinities such as Tyr, Thor, Odin, Ingwaz/Freyr, Frigg, Baldr, and Nerthus.

The sun in later mythological contexts

The solar cycle is well attested on the early picture stones, and some of the other divine powers are indirectly known from other sources. In spite of this, it is difficult to understand the more specific mythological context of this cycle, but possible fragments of a mythological context may be glimpsed from different later analogies. Because the analogies come from different times and places there is always a risk of reconstructing too homogeneous a mythological background. However, using the analogies in a dialogue with the Gotlandic pictorial world makes it possible to sketch a more specific background (cf. Wylie 1985).

Some aspects of the way the sun was understood can be gained from late references in Eddic poetry, and especially the metaphors for the sun in this poetry. According to Grímnismál 38 the sun is called ‘the shining god’ (scínanda goði), in front of which was a shield called Svalin, which protected the mountains and sea from burning up. Sigdrífumál 15 states that runes should be cut on the shield ‘which stands before the shining god’. In Alvíssmál 16, we read that ‘Sun it is called by men, and sunshine by the gods, for the dwarfs it is Dvalin’s deluder, the giants call it everglow, the elves the lovely wheel, the sons of the Æsir all-shining’ (Sol heitir með mǫnnom, enn sunna með goðom, kalla dvergar Dvalins leica, eygló iǫtnar, álfar fagrahvél, alscír ása synir). Snorri also mentions in Skáldskaparmál that the sun could be called the ‘day star’ (sunna), ‘elf-disc’ (alfrǫðull), ‘the doubt disc’ (ifrǫðull), and ‘the stained’ (mýlin). The idea of the sun as a wheel echoes the symbols of the sun-wheels, whereas the shield in front of the sun carries associations with the images of warriors bearing shields with whirls and spirals on some early picture stones.

In the Icelandic narrative tradition, the sun and the day, as well as the moon and the night, were also regarded as anthropomorphic powers. As noted above, the sun could be called ‘the shining god’. However, according to Snorri’s Gylfaginning 34, Sól (‘sun’) was one of the Æsir goddesses. In Gylfaginning 10, which Snorri based in part on Grímnismál 37–39, Sigrdrífumál 15, and Vafþrúðnismál 23, he mentioned that Sól and Máni (‘moon’) were children of Mundilfari (‘the one moving according to particular times’). Sól drove a chariot pulled by two horses, Árvakr (‘early awake’) and Alsvíðr (‘very quick’), across the sky by day, and was pursued by a wolf called Skǫll (‘mockery’). Similarly, according to Gylfaginning 10, Máni drove another chariot pulled by two horses across the sky by night, and was chased by the wolf Hati (‘despiser’). Both of these wolves are probably poetic embellishments of Fenrir (Simek 1993:201, 222, 297).

Snorri also stated in Gylfaginning 9, which he partly based on Alvíssmál 29 and Vafþrúðnismál 12, 14, and 25, that a giant in Jǫtunheim called Nǫrr (‘narrow’) had a daughter call Nótt (‘night’), who married three times, among others a man called Naglfari. From these marriages, she had a son Auðr (‘prosperity’), a daughter Jǫrð (‘earth’), and a son Dagr (‘day’). Snorri adds that Nótt drove a chariot pulled by Hrímfaxi (‘frostmane’), who dripped dew from his bit at dawn. Nótt was followed by Dagr (‘day’), who crossed the sky in a chariot pulled by Skinfaxi, (‘shining-mane’), who illuminates the world with his mane (Simek 1993:55, 235, 238). Although this story is only known in Snorri’s version, it contains several interesting aspects. The notion that the day is born from the night fits well with the Old Norse time-reckoning, which was based on the idea that the day ended at sunset, when a new night and day started (Nordberg 2006). Naglfari could possibly be connected with the ship Naglfar (‘nail-ship’, or ship of the dead), which appears in Vǫluspá 50, and is described by Snorri in Gylfaginning 42 and 50 as the biggest of all ships, which is used by the powers of chaos at the end of the world, Ragnarok (Simek 1993:226). Jǫrð is usually regarded as mother of the thunder-god Thor (Simek 1993:179), giving associations with the earth as well as the sky. At the same time, the personification of the day seems to have had a broader mythological context, since Snorri describes Dagr in Skáldskaparmál 62 as the divine ancestor of the Dǫglingar, to which the Eddic hero Helgi Hundingsbani is said to belong (Simek 1993:55).

The sun also has a central position in Sólarljóð, which is a late and clearly Christian poem. Many of the references to the sun in this poem have convincingly been interpreted as expressions of the Christian God (Fidjestøl 1979). However, in Sólarljóð 55 a sun-deer (sólar hjǫrt), with its hoofs on the earth and antlers in the sky, is mentioned. This figure could be a Christian symbol, but in view of the horned animals in Iron Age iconography, it could also be an older motif, and in that case possibly an alternative to the idea of a sun-horse.

Although the Eddic poems and Snorri describe the sun, the moon, the day, and the night as personifications, they do not play any particular role in the mythological narratives preserved in medieval Iceland. It is therefore difficult to determine whether the personifications are late inventions, possibly by Snorri himself, or echoes of older worldviews. Nonetheless, Tacitus’ account of an anthropomorphic sun god could indicate a deep history behind the personifications. Other arguments for early personifications can be taken from the Sámi and the Old Baltic religions, where the sun played a much more central role in mythological tradition (Nesheim 1971; Biezais 1975; Vaitkevicius 2004; Mebius 2003). Admittedly, these mythologies were collected at a later date, usually after the Middle Ages, but the geographical distance from the Sámi and Baltic regions to southern Scandinavia is very short, making them interesting as analogies nonetheless. After all, the distance between Gotland and the coast of Curonia is only 150 kilometres.

In the later Sámi tradition, the sun was regarded as a female being, from whom all living animals descended. The symbol of the sun was a cross, often inserted into a square or a rhomb. This symbol was painted in the middle of many shamanistic drums from the southern Sámi area (Nesheim 1971; Mebius 2003:75). In the Old Baltic mythological traditions from Latvia, Lithuania, and Old Prussia, recorded in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the sun goddess Saule played a central role (Biezais 1975:329 ff.; Vaitkevicius 2004:12 ff.). She drove her horsedrawn chariot over the celestial mountains by day and returned in a boat through the underworld by night. She was accompanied by Dieva deli, that is, the sons of the sky god Dievas. A solar tree as well as Saules meitas, or Saule’s daughters, were also important parts of the solar myth. The goddess Saule was one of the main figures in the Old Baltic pantheon, which also included divinities such as the moon god Meness, the morning star god Auseklis, the sky god Dievas who lived in the celestial mountains, the thunder god Perkunas who wielded a bolt, the goddess of fate Laima, and Mother Earth (Biezais 1975).

Most of the divine figures in the Old Baltic mythology are functionally and linguistically recognizable in the narrative tradition from Iceland, although their importance differed quite considerably. Saule can be equated with Sól, Meness with Máni, Auseklis possibly with Aurvandill, Dievas with Tyr, Mother Earth with Jǫrð, and Perkunas with Thor. However, no clear counterparts to Dievas deli existed in the Icelandic narratives, although they represented an Old Baltic version of the Dioscuri motif. In the Baltic tradition, they were sons of the sky god, just as the classical Dioscuri were sons of the sky god Zeus, literally dios kuroi (‘Zeus’ sons’).

Although no apparent Dioscuri motif is preserved in the Icelandic literature, several scholars have interpreted the references to two brothers of Haddingjar (tveir Haddingjar) in Hyndluljóð 23, Ǫrvar-Odds saga 29, Hervarar saga 3, and Saxo Grammaticus 5:13:4 as echoes of a Dioscuri motif, with Odinic associations (Ward 1968; Dumézil 1973; Simek 1993:127). Another possibility is to regard the two sons of Odin – Vidar and Vale – as echoes of the divine twins (Magnus 2001a). As mentioned above, there are also some references to twin motifs in earlier written sources and images until the eighth century regarding northern Europe (Krüger 1940; de Vries 1957:247 ff.; Ström 1975; Hauck 1984; Magnus 2001a). Apart from the earlier noted references by Tacitus to ‘Alcis’ and by Timaios to the ‘Celtic’ Dioscuri, the twin motif is present in several Germanic origin myths. According to these myths, the Langobards were led by Ibur and Aio, and the Vandals by Raos and Raptos, whereas the Anglo-Saxon conquest of Britain was led by the twins Hengist and Horsa, literally ‘stallion’ and ‘horse’. A twin motif may also be present in the Swedish royal brothers Alrik and Erik as well as Alf and Yngve mentioned in Ynglingatal (de Vries 1957:251 ff.; Hauck 1984). The sources on north European Dioscuri are thus sparse, but the names are connected with a semantic field of twin warriors, horses, and elk, which fits very well with the images of two men, warriors, armed riders, horses, and/or horned animals in Scandinavia from the third to the seventh centuries AD. The position of these images on the early Gotlandic picture stones shows that the Scandinavian Dioscuri were seen as helpers of the sun at sunrise and sunset, just like the Dieva deli of the Old Baltic tradition. The transformative character of these men/ riders/horses/deer/elk can best be explained by their functions during the daily trip of the sun.

As mentioned above, Tyr can be identified on the picture stone at Austers in Hangvar (Fig. 54) as well as on some of the gold bracteates (Öberg 1942; Oxenstierna 1956; Ney 2006). In the much later Icelandic narrative tradition, Tyr is a very vague figure, except for the story about how he lost his hand (Simek 1993:337). According to Snorri’s Gylfaginning 24, the wolf Fenrir grew too strong for the gods and threatened the world. Therefore the wolf had to be tied by strong fetters made by the dwarfs. The wolf only allowed the chain to be put on if Tyr put his hand in the mouth of the wolf. When the beast noticed that he could not break free he bit the god and Tyr lost his hand. This narrative has been interpreted as a divine sacrifice to secure the cosmic order (de Vries 1957:24). Regardless of this divine sacrifice, Tyr will finally be killed by the hound of Hel at Ragnarok, and the wolf will eventually eat the sun as well as the moon, according to Gylfaginning 50 (see Simek 1993:80).

Another god that may have been connected with the solar cycle is Thor, who was indirectly mentioned by Tacitus as early as AD 98. He is not depicted as a figure on the early Gotlandic monuments, but animal attributes connected with him can be traced. On the picture stone from Väskinde two horned animals are depicted above the whirl (see Fig 50). They seem to represent two he-goats, offering associations with Thor, who drove a chariot drawn by two he-goats (Hymiskviða 37; Gylfaginning 20, 43). Thor was the thunder god, but also a fertility god and a defender of the cosmic order against powers of chaos. One of his antagonists was the large snake surrounding the world, which Snorri called the Midgard serpent (Hymiskviða 18–25; Gylfaginning 47). This monster is probably depicted between the horizontal line and the ship in the underworld on the picture stone from Sanda, providing further links to Thor on the picture stones (see Fig. 47).

Another possible link between the solar cycle and a divine figure is Freyr. He has not been identified with any certainty on the picture stones, but he is known in the Icelandic narratives as a fertility god connected with sunshine, water, seafaring, ships, and carriages (Simek 1993:31 ff., 379 ff.). According to Snorri, Freyr rules over ‘rain and sunshine’ (Gylfaginning 23) and owns the ship Skíðblaðnir (Gylfaginning 42–43, Skáldskaparmál 7 and 33), with its associations with the sun as well as the night-ship on the early Gotlandic picture stones.

Figure 54. Picture stone from Austers in Hangvar. Above the central whirl is a monster and a human putting a hand into the mouth of the monster. The image, which has parallels among the gold bracteates, calls to mind the myth of Fenrir and Tyr. (Photo by the author.)

Summarizing the different analogies, it is possible to outline certain basic elements in the Gotlandic solar cycle, although the specific mythological context is not known. The sun could have been regarded as a sun goddess, comparable with the Icelandic Sól or the Baltic Saule. According to Tacitus and the Icelandic tradition of a ‘shining god’, however, the sun may also have been viewed as a sun god. In the later Icelandic narratives there are many candidates for a possible transformed sun god. Among the candidates are Freyr, who was the divine lord and ruler of sunshine; Ull (Ullr), whose name probably derives from a word meaning ‘lustrous’ (de Vries 1957:159); Baldr, whom Snorri describes as ‘so bright that light shines from him’ (Gylfaginning 21); and possibly Odin, who Snorri says was the Allfather of the gods and whose one-eyed-ness is a characteristic of many other sun gods ( cf. West 2007:194 ff.).

The sun, whether it was considered a female or male being, was helped at sunrise and sunset by divine twins in the shape of warriors, riders, horses, or horned animals. As noted above, no clear Dioscuri are known in the Icelandic literature, but some of the gods with solar aspects may have included elements from the divine twins, such as Baldr and Odin, especially since the character of the two Haddingjar was Odinic. At its zenith, the sun passed through the sky, where the sky god Tyr ensured the cosmic order. He did this by sacrificing his hand in the mouth of a chained wolf, which would otherwise devour the sun. The cosmic order was also secured by the thunder god Thor, who fought the powers of chaos in the sky and the world serpent in the sea around the world. During the night, the sun travelled in a night-ship in the underworld. The ship could also have been regarded as a ship of the dead, associated with a chthonic god and goddesses, such as Niord (Njǫrðr), Freyr, or Freyja.

The early Gotlandic solar cycle thus seems to have included some of the divinities known from the later Icelandic narratives. However, the context was different in the sense that the gods were part of a solar cycle that later disappeared. This means that their character, and consequently the narratives about them, must have changed fundamentally in most cases.

Tracing sun rituals

The pictorial world, as well as the rune-names and some written sources, indicate that solar traditions, resembling the Bronze Age solar myth that Kaul has reconstructed, still existed in the Iron Age until the sixth century. Kaul has also presented good evidence that the solar cycle was linked to rituals during the Bronze Age. In the Iron Age, there are obvious links between the sun and mortuary practice, since ship-forms, wheel-crosses, and other geometrical rings as well as the picture stones were directly connected with graves in many areas. The daily trip of the sun through the sky and the underworld, and possibly the annual solar cycle, must have still been regarded as being closely related to issues of life and death and the question of time. Indeed, as noted above, the night-ship could also have been associated with a death ship.

Sun rituals in general are more difficult to trace during the Iron Age, although there are indications from written sources as well as place-names. A few written sources about central and northern Europe underline the ritual importance of the sun in the Iron Age. According to Caesar’s De Bello Gallico 4:21, the Germanic tribes that he encountered in central Europe worshipped the sun (de Vries 1956:355 ff.). This statement has been viewed as a classical topos, making his enemies more primitive, because they did not have named gods. However, the details of a sun god given by Tacitus in AD 98 actually indicate the importance of the sun in northern Europe. As mentioned above, he writes that in the sea north of the sviones, the sound of sunrise could be heard and the shape of the sun god and his horses could been seen (Tacitus 1999:60; cf. de Vries 1956:355 ff.). Later on the sun is also mentioned by Procopius in his description of Scandinavia in the sixth century. He writes that people in Thule celebrated the return of the sun, after it had disappeared for 35 days during midwinter. Judging by his description of the five weeks without sun, this ritual must have taken place north of the polar circle in northern Scandinavia (de Vries 1956:355 ff.; cf. Nordberg 2006).

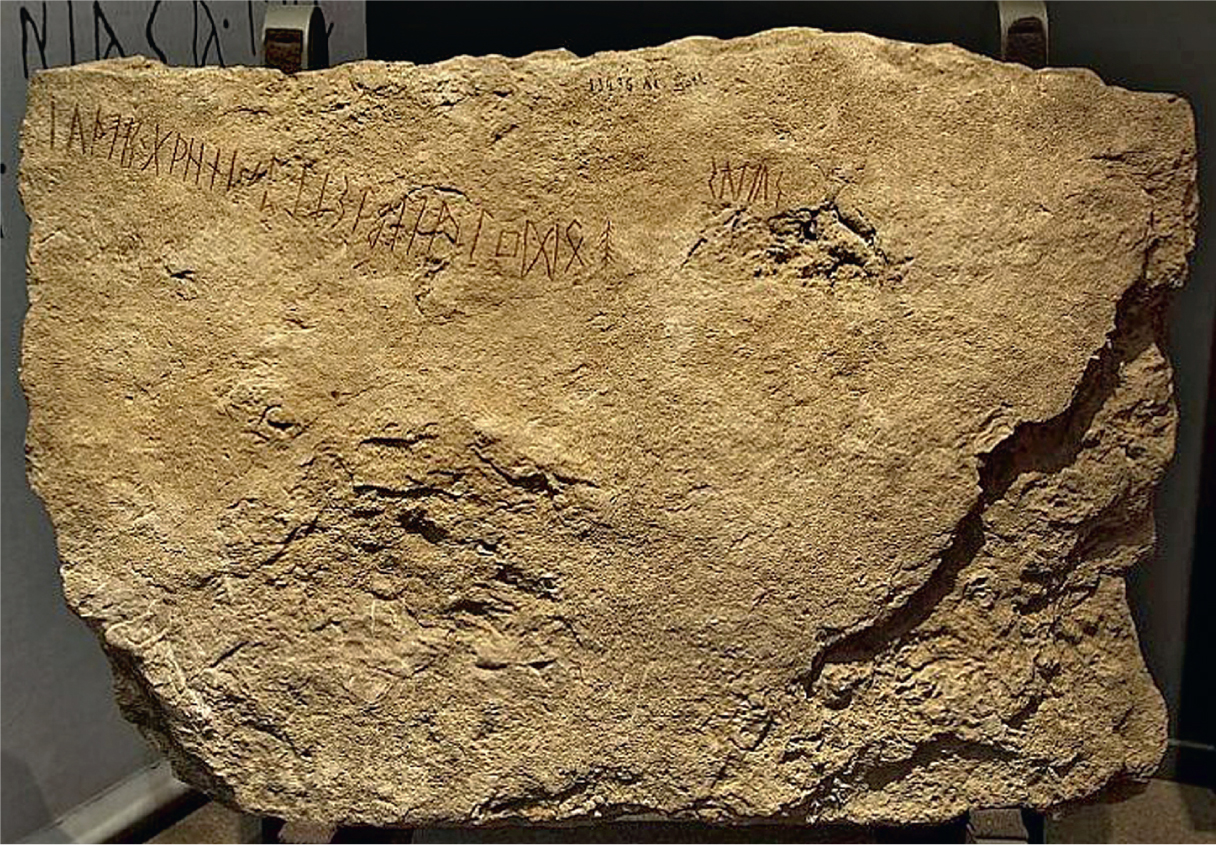

Another indication of the ritual importance of the sun during the Iron Age could be different place-names with the compound sol- (‘sun’), such as Solberga, Solheim, and Solstad. In earlier place-name studies these names were regarded as sacral (see Lindroth 1918; Kiil 1936), but they have, for quite some time, usually been explained away as non-sacral designations of sunny places. In a survey of the literature, Lars Hellberg underlines that many of the sol -names seem to be recent, and consequently should be regarded as profane. He does not exclude, however, that some older names could be interpreted in ritual terms (Hellberg 1967:193–6). For instance, the compound -berga, as in Solberga, is in several cases combined with names of divinities such as Freyja, Niord, Odin, Thor, and Ull (Vikstrand 2001), pointing to possible sacral aspects of hills (Fig. 55). Besides, many of the sol- names are securely attested as names for old, large settlements that can be linguistically dated before the Viking Age. The compound was not commonly used for place-names dated to the Viking Age and the early Middle Ages, such as -by, -torp, and -ryd, and if the sol- element only designated sunny places one would expect many more examples to be found among these younger place-names. Recently, the place-name Tungelunda in Östergötland has also been interpreted as a sacral name connected to the sun or the moon, because tungl means ‘celestial body’ (Strid 2009:85).

The best archaeological evidence for a ritual interpretation of the compound sol- in place-names comes from two bronze figures of horned animals from Solberga on Öland (Fig. 56), found on a large farm dated from the third to the fifth centuries (Persson and Rasch 2001:373–4, cf. Fallgren 2008:132). As mentioned above, one of the animals has a decorated ring at the neck, which resembles the remark by Snorri that the horse of Dagr, Skínfaxi, illuminated the world from his shining mane. The horned animals from Solberga can thus be interpreted as sun-animals, possibly used in rituals at the site. A ritual interpretation of the sol-names may also be supported by analogies with the Baltic region. In Latvia and Lithuania a common place-name is Saulekalns, meaning ‘sun hill’, a direct equivalent to the Scandinavian place-name Solberga. In many cases, midsummer rituals are recorded from places called Saulekalns (Vaitkevicius 2004:12 ff.).

This is not the place to thoroughly explore all the possible ritual aspects of the sol-names, but some general comments may be added. The names are known from all parts of the Scandinavian agrarian settlement, from the middle of Norway and Sweden to southern Denmark (see Fig. 55). Usually a few sol-names are known from each region or province – on Öland and Gotland there are two Solberga on each island, for example. The names occur in onomastic environments with old place-names, and sometimes designate regions and islands as well. Two good examples just north of Stockholm are Solland, a regional name surviving in the place-name Sollentuna (de Solendatunum, 1287), and Solna (Solnø, 1305) which originally was a name for an island (Wahlberg 2003:287–8).

Figure 55. Distribution of the place-names Solberg, Solberga, and Solbjerg in Scandinavia. Kiil emphasizes that his survey is not comprehensive, and probably the Norwegian examples are over-represented in relation to Denmark and Sweden. Nevertheless, the map gives an idea of the regions where these sun-related names are found. (Map by the author, based on Kiil 1936.)

Figure 56. Horned animals of bronze from Solberga in Gräsgård on Öland. One of the animals has a decorated ring at the neck, placed in the same way as the head on C-bracteates. This and the pair motif indicate that the animals were used in sun rituals at Solberga. (Photo by Pierre Rosberg, Kalmar Länsmuseum, Kalmar.)

The disappearance of solar symbols and sun rituals in the sixth century

As noted above, the early picture stones on Gotland were all surprisingly similar in structure and motifs, always including a whirl. However, a few late examples of these monuments, probably from the sixth century, contain some new expressions. The usual large whirl is replaced by a quatrefoil knot on two stones from Austers in Hangvar (see Fig. 54) and Havor in Hablingbo (Lindqvist 1941, fig. 23), and by a three-pointed figure, triskele, of three different animals on a stone from Smiss in När (Lindqvist 1962; Arrhenius 1994). Apart from the triskele, the Smiss stone also contains a totally new motif, namely a human in a sitting position holding a snake in each hand. These monuments mark the transition to an intermediate group of small picture stones, which are generally dated to the seventh and eighth centuries (Lindqvist 1941; Nylén and Lamm 2003).

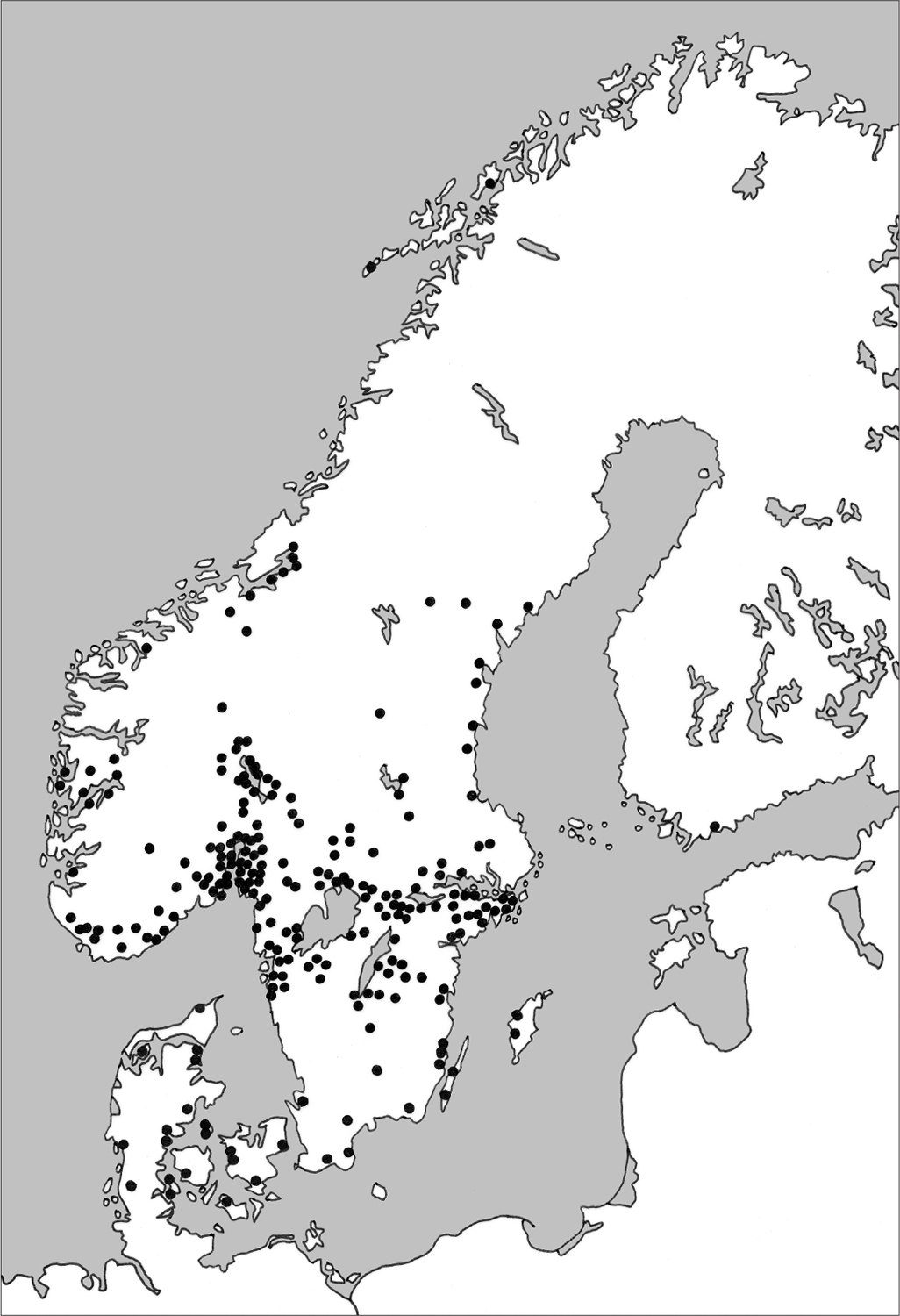

There are about 70 intermediate picture stones, usually not exceeding one metre in height (Fig. 57). They are often found in the burial grounds, where they were once erected, and not in medieval churches like the early large picture stones (Lindqvist 1941; Nylén and Lamm 2003). Not a single monument of this group of small stones contains a whirl or a spiral. Instead, the motifs are reduced to a few recurring images; ships with or without sails, horses, aquatic birds, snakes, riders, horned animals, and chess-formed patterns possibly representing sails. Sometimes the horses and birds are placed antithetically, sometimes they appear as pairs cut on both sides of a monument (Ragnarsson 2007). This means that the twin motif was partly preserved, whereas the sun disappeared. However, there is no recurring structure in the images found on these stones. Sometimes the ship is at the top of a stone, sometimes at the bottom.

In the ninth and tenth centuries, these intermediate stones were followed by the classic Gotlandic picture stones, which contain vivid and varied images. Some of these pictures can also be connected with Old Norse mythology and the heroic narratives known from Old Icelandic literature, but apart from the monument at Bote in Garda (Lindqvist 1941, fig. 41) none of the stones contain references to the sun. A few stones once again depict antithetically placed warriors, which may echo the former twin motif, and many of these later monuments also depict a ship at the bottom of the stone, as a parallel to the early picture stones (Myrberg 2005), but in contrast to the early stones the direction of the ship varies. However, it is quite clear from the later picture stones on Gotland that the sun symbolism, which was so dominant from the very first monuments in the third century, suddenly disappeared during the sixth century.

In central Sweden it is not possible to follow the changes in the same way, since picture stones on the whole ceased to be erected after the sixth century. However, some of the older pictorial monuments were destroyed and reused in later burials. This destruction has led some scholars to suggest a kind of iconoclasm, again mirroring fundamental religious changes (Hamilton 2012)

Images on metalwork followed the same pattern. Gold bracteates fell out of use in the mid sixth century (Axboe 2007:65–76). Only on Gotland did bracteates made of above all silver and bronze continue to be produced in the seventh and eighth centuries. The central figures on these bracteates were often simple triquetra motifs (Gaimster 1998). In order to follow the fate of the solar images in the sixth century and later it is therefore necessary to use other metalwork in Scandinavia from the Merovingian and Viking ages. Metalwork, such as decorated weapons and dress ornaments, gold-foil figures, and small three-dimensional figures, depict animals and human figures that can be provisionally related to the Icelandic narratives by their more distinct attributes. In many cases, the pictures from the sixth century onwards are more or less disguised in complicated animal art, but once again the sun seems to disappear in this context (Arrhenius 1994; cf. Price 2006). Twin motifs continued to be used in the seventh and eighth centuries, but later also disappeared (Magnus 2001a). Once again, there is a clear parallel to the images on the Gotlandic picture stones after the sixth century.

Figure 57. Picture stone from Smiss in Garda. This monument is an example of the intermediate picture stones of the sixth and seventh centuries. (Photo by the author.)

In short, after the sixth century, the solar cycle disappeared from the pictorial world of Scandinavia, and probably many of the sun rituals as well. Place-names with the compound sol- do not seem to have been coined in the Viking Age or later. In the Viking Age, we only find echoes of the former importance of the sun. A late sun ritual in burial context may be inferred from a site called Rösaring in southern Uppland, discovered only 25 years ago. It is a road, 540 metres long, running from a small house to a grave mound. The road bank is built in a straight line from north to south, and is flanked on the eastern side by a row of about 120 post-holes. The monument, which is dated to the ninth and tenth centuries, has been interpreted as a ritual road used in connection with funerals, and is said to have solar associations (Damell 1985; Pásztor et al. 2000). Another late reference to the sun comes from Cnut the Great’s Anglo-Saxon laws from the 1020s, partly directed at Scandinavians in the Danelaw. According to this code, rituals addressing the heathen gods as well as the sun, the moon, and the stars were prohibited (de Vries 1956:356–7). It is probably these remaining solar aspects of the Viking Age that can explain why the sun is mentioned in the later Icelandic texts. However, the sun plays no active role in the Eddas and the sagas, which shows that only distant echoes of the former role of the sun were left in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. In the late Sámi tradition, on the other hand, the female sun was still worshipped in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. There are references to offerings of food and burnt sacrifices at midsummer, and also the slaughter of white female animals, honouring the female character of the sun (Nesheim 1971). Similarly, in the Baltic traditions, the sun preserved much of its importance until the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Biezais 1975).

Solar traditions through time

The sun has shone on us since the beginning of time. The metaphorical potential of the sun as the source of light and warmth is endless, and the sun has consequently been important in many cultures around the world. In the European Neolithic, it is evident from the layout of Megalithic monuments as well as henge monuments that the sun played a fundamental role (Kaul 2004:379). In several cases the sunrise and the sunset at midwinter and midsummer were the main orientations of these monuments. However, the solar myths and rituals that Kaul has reconstructed are much more specific and detailed. They probably built on the old importance of the sun, but show that many new elements were introduced and reinterpreted. Groups in southern Scandinavia, with some form of long-distance relations across Europe, seem to have created a new religious tradition around 1500 BC. Many elements were taken from central Europe and ultimately from the eastern Mediterranean, but they were brought together in a new specific context, shaping an early form of a Scandinavian narrative and ritual tradition concerning the journey of the sun.

At the start, the solar myth included the sun being drawn across the sky and the underworld by one or two horses. The divine twins may have been part of the tradition from the beginning, their transformative functions being expressed through images of men with horned helmets, axes, and lurs. A mushroom-shaped figure also formed part of the tradition. It is clear from the Trundholm sun-chariot as well as rock carvings and graves that the solar myth was not only a narrative but also connected to rituals associated with the sun. The solar myth nonetheless changed gradually over time. Due to local reinterpretations of new models from central Europe, the image of the ship as a main form of transport for the sun was introduced, together with images of serpents and aquatic birds around 1100 BC. The narrative tradition was still connected to rituals, which must likewise have changed. Above all, ships, models of ships, and ship symbols became important parts of the rituals.

Around 500 BC, many of the representations of the solar myth disappeared. The expressions were reduced to formalized symbols such as wheel-crosses, concentric rings, and ship-forms, used in metalwork as well as external grave markers. Only burial rituals and deposits of neck-rings in pairs can be connected to the narrative tradition from that time. Three hundred years later, around 200 BC, even these sparse sun symbols disappeared, apart from some objects involving images of aquatic birds, triskeles, and more or less complex wheel-crosses and concentric rings as grave markers in Norway and Sweden. From an archaeological point of view the four centuries years between about 200 BC and AD 200 are the most obscure. Nonetheless, it is from this very period that the earliest classical sources actually describe the continuing mythological importance of the sun and its horses, as well as the divine twins in central and northern Europe.

From around AD 200 to 550 the existence of solar myths is once again clearly visible in images and objects. The narratives now appear to have involved the sun moving around the world tree, across the sky, and then through the underworld in a night-ship. At sunrise and sunset, the sun was helped by divine twins in the form of warriors, armed riders, horses, or horned animals. Possibly some of the gods in the Icelandic narratives have their roots in transformed sun divinities and the idea of divine twins. The sky god Tyr and the thunder god Thor secured the cosmic order by controlling forces of chaos in the form of monsters or serpents. As in earlier narratives, the late versions of the Scandinavian solar myths were also related to rituals. The narratives are visible in the burial context of the picture stones on Gotland and in Uppland and Södermanland, but the horned sun-animals from Solberga and the place-name compound sol- in general indicate other rituals, too.

The solar cycles in the Iron Age seem to have had many similarities to the old solar myths from the Bronze Age. However, the ship had lost much of its importance as a means of transport. It is also possible that the old solar myths were renewed with inspiration from the contemporary Roman world (Gelling and Davidson 1969:182). The Roman Dioscuri as well as the imperial cult of Sol Invictus, which was introduced in the early third century, may have stood as models for local reinterpretations of earlier mythologies. One argument for such Roman impulses is that the best formal parallels to the early Gotlandic picture stones come from Roman altars, mosaics, and gravestones (Lindqvist 1941:91 ff.; Holmqvist 1952; Gelling and Davidson 1969:144).

Above all the gold bracteates, and their parallels with some motifs on the Gotlandic picture stones, indicate that Scandinavian rulers, at least since the fourth and fifth centuries, ruled through a divided leadership legitimized through the divine twins as supporters of the sun. However, the important solar cycles with their sun symbols rapidly disappeared from images in the sixth century. Instead, the narratives and rituals about the divine and celestial world were thoroughly transformed during the sixth and seventh centuries. Only faint echoes of the solar cycles survived into the medieval Icelandic literature, probably due to the sun remaining an important natural phenomenon. To sum up, the solar myths and sun rituals of ancient Scandinavia show a great deal of continuity, with variations and successive changes being based on incorporations and reinterpretations of foreign models. It is a complex tradition that is largely outside the reach of the later Icelandic narratives, but was still an important part of Old Norse religious tradition.

Figure 58. Gamla Uppsala with its ‘royal mounds’ and the remains of the cathedral. The large mounds have been dated to the late sixth and seventh centuries, and can be regarded as symbols of a new social order emerging after a crisis in the mid sixth century. (Photo by the author.)