CHAPTER 3

A world of stone

Warrior culture and Old Norse cosmology

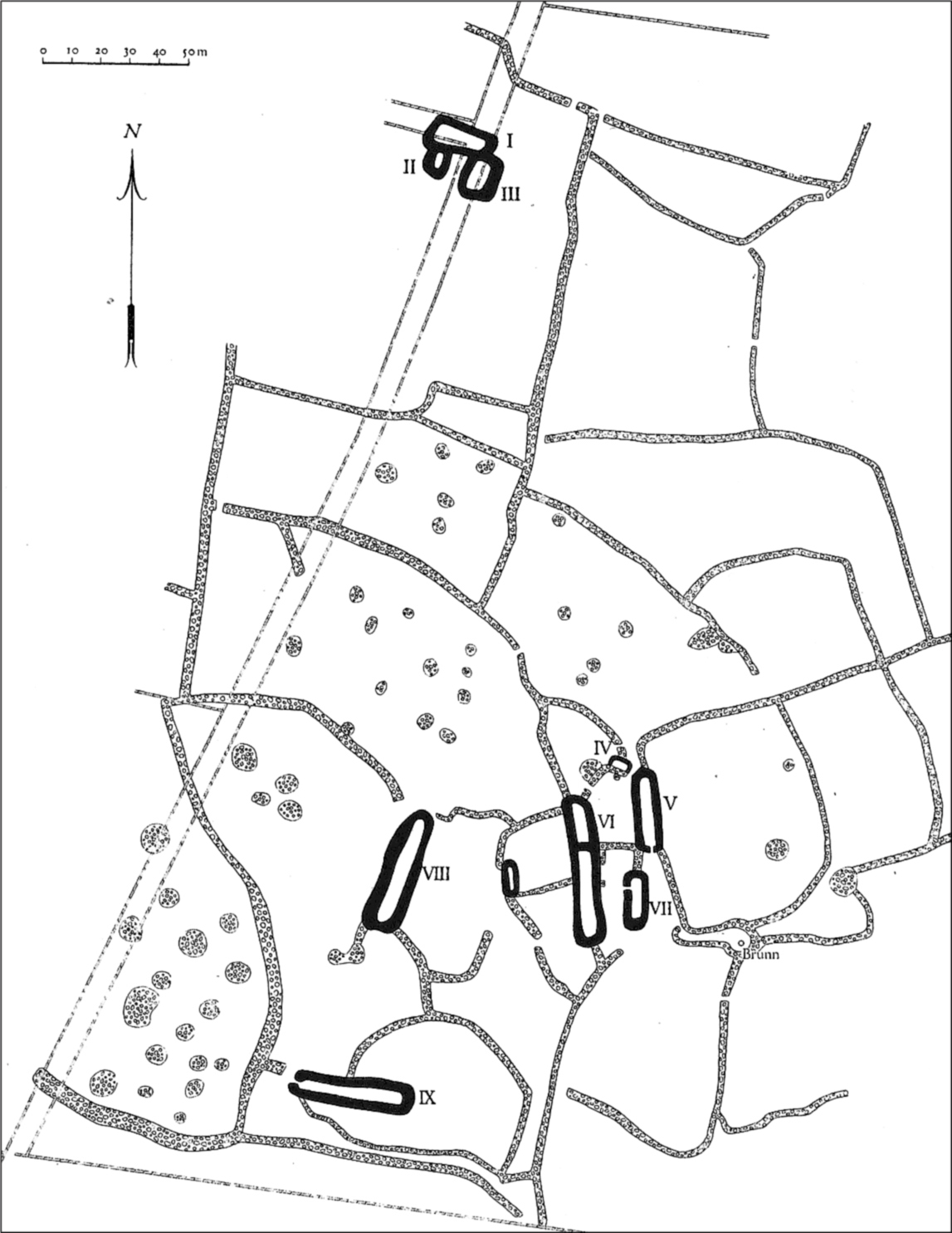

‘Ismantorp fort is undeniably one of the most interesting of Öland’s prehistoric defensive structures and one of the most remarkable ring-forts in our country as a whole.’ This is how the Swedish archaeologist Mårten Stenberger (1898–1973) begins his description of Ismantorp in his classic dissertation on Öland in the Early Iron Age (Stenberger 1933:235, my translation). Archaeologists often declare their finds to be unique and sensational, but in this case Stenberger’s words are fully justified. Ismantorp fort, located in the middle of the long, narrow island of Öland in the Baltic Sea, is amazingly well preserved. Even after one and a half millennia it still presents visitors with a ring-wall four metres high, surrounding almost a hundred fully visible house foundations of limestone. Nine gateways in the wall give access to the fort (Fig. 20), and at its centre there is a small open place.

This remarkable ringfort has been described, measured, and interpreted since the 1630s. Archaeological excavations have been conducted at the end of the nineteenth century and during the first four decades of the twentieth century. After extensive clearance of thick vegetation in and around the fort in the 1940s, the site has been a popular tourist attraction, and the ruin fires the imagination so strongly that it has even figured in a Swedish detective novel (Mårtenson 1987). In archaeological terms, the fort is remarkable because the ruin is so well preserved yet we know so little about the site. The old excavations have yielded very few results. No occupation layers or datable objects have been found, only scattered animal bones and pieces of charcoal.

Although our knowledge of the place is slight, the generally accepted interpretation was formulated by Stenberger nearly ninety years ago (Stenberger 1925, 1933:236 ff.; cf. Näsman 1997). He believed that Ismantorp served as a place of refuge in times of unrest during the Migration Period (400–550). Moreover, Stenberger claims that it was used as a central cultic site, since the nine gates were not suitable for defending a fort. In his interpretation, he refers to late Slavic strongholds from the eleventh and twelfth centuries, which functioned as places of refuge as well as ritual sites. One of the examples, Rethra/Radegost, a stronghold that has never been localized, is even described as having nine gates (Stenberger 1925, 1933:241–2; Słupecki 1994:51 ff.). Stenberger’s words contain a fantastic possibility. If his hypothesis is correct, the well-preserved fort of Ismantorp could give us a total picture of a pre-Christian cultic site. The monument could thus play a crucial role in the discussion of pre-Christian ritual and religion, but the interesting thing is that Ismantorp never assumed that role. Neither archaeologists nor historians of religion refer to the fort in connection with Old Norse religion. The reason for this silence is largely due to Stenberger himself. In the absence of direct evidence for ritual activities, he never generalized his interpretation of Ismantorp. Instead the interpretation remained an ad hoc explanation of a remarkable ruin.

To renew the discussion about Ismantorp, I revisited the ringfort in 1997–2001. The circumstances of these visits are different from those encountered by Stenberger when he did his fieldwork in the 1920s and 1930s. The nearby and contemporary ringfort of Eketorp was totally excavated in 1964–74, and the results of those excavations are an important point of reference for Ismantorp (Borg et al. 1976; Boessneck et al. 1979; Borg 1998). In addition, the archaeological discussion of forts has changed character in the last few decades. The very concept of ‘ringfort’ or ‘hillfort’ (Swedish fornborg) has been questioned, and the variation in these structures in both time and place has been stressed. The connection of the forts with wars and periods of unrest has also been criticized for being stereotypical. My visits have not found any support for Stenberger’s interpretation, but they have made it possible to put Ismantorp in other contexts which are at least as relevant for the discussion of both Scandinavian forts and the character of Old Norse religion.

A biography of Ismantorp

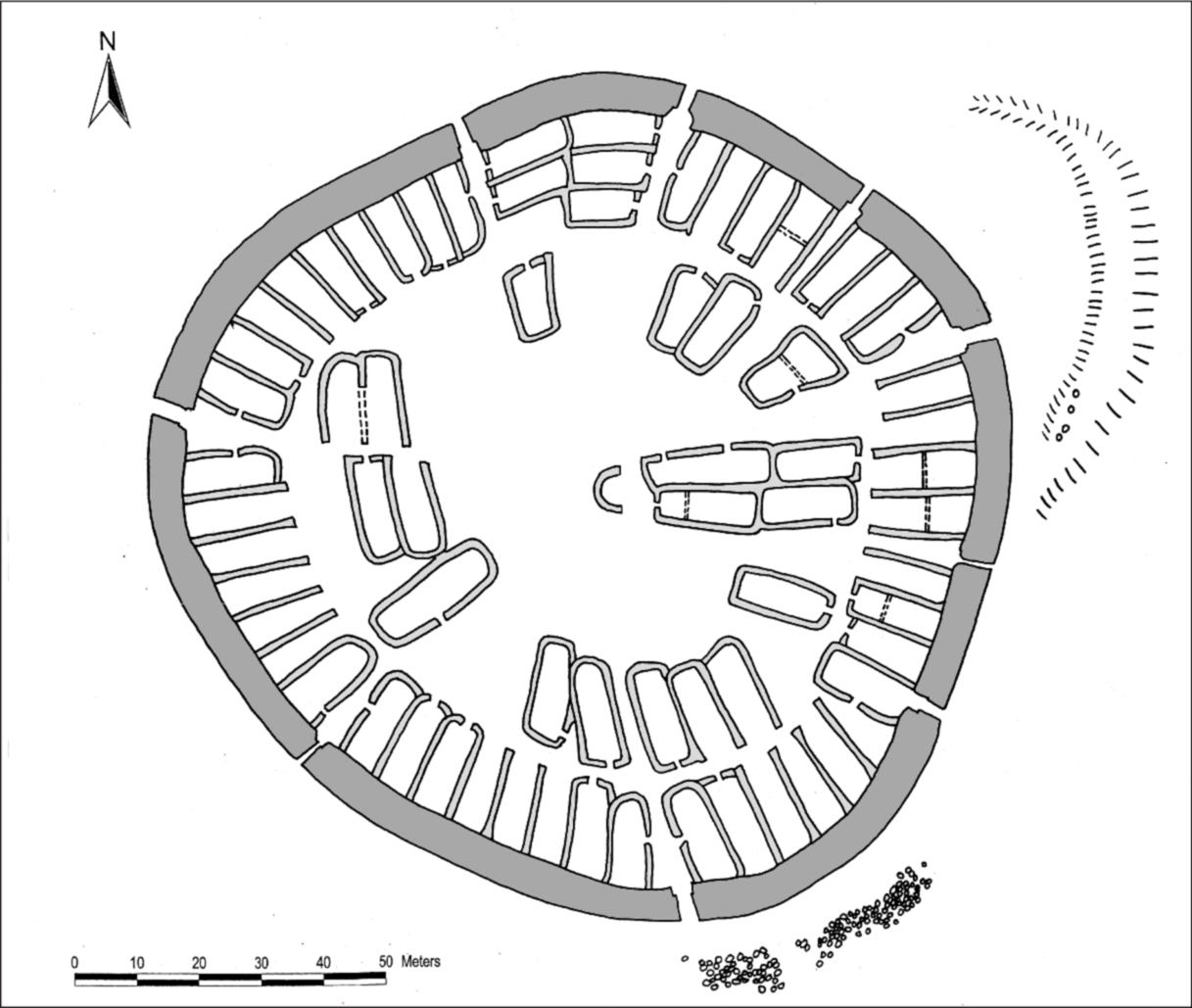

In this connection it is only possible to give a brief account of the fieldwork in 1997–2001, which was carried out in collaboration with Kalmar County Museum. In view of the disappointing results of previous excavations, a great deal of effort was expended on general surveys. Firstly, a new detailed plan of the fort and the topography was drawn up, based on rectified aerial photographs (Fig. 21).

The fort at Ismantorp was built on a dry moraine hillock, which rises just a few metres above a flat landscape with large shallow bogs and wetlands. The distances to the nearest settlements, both in the present and in the past, are one to two kilometres. The site was never permanently inhabited, because no occupation layers have been found either inside or outside the ring-wall.

The fort consists of a drystone limestone ring-wall 410 metres long with nine gates. Three of these openings, in the south, the west, and the north-east, are wide main gates, and from each a street leads directly to the centre of the fort, which consists of a triangular square. Outside two of the main gates there are special outworks, consisting in the northeast of a low rampart of earth and stone and in the south of a zone with closely placed granite boulders. In both cases the openings in the outworks are displaced counter-clockwise in relation to the gates in the ring-wall. The six smaller gates are narrower and in the final phase of the settlement they have no direct communication with the centre of the fort. Moreover, one of the smaller gates leads first into a house situated on the inside of the wall, and from this house into a narrow lane beside the building.

Inside the ring-wall, a total of 95 houses were built, 49 of them against the wall, 45 in three blocks in the centre and one small semi-circular building in the centre. Of the 49 houses along the ring-wall 5 were built parallel to the wall and not radially from it like the rest of the houses. Judging by joints between the foundations, the houses were built in several stages. At least two main phases of the settlement can be discerned, although they are not possible to date in absolute terms. The first phase consisted of all the houses along the ring-wall and nine small groups of houses in the interior, placed so that all the nine gates communicated with the centre of the ringfort (Fig. 22). In the second phase, further houses were irregularly built between the nine groups of houses, thereby creating three main blocks and three main streets linking the main gates with the centre.

Figure 21. Aerial photo of Ismantorp ringfort. (Photo by Metria, Norrköping.)

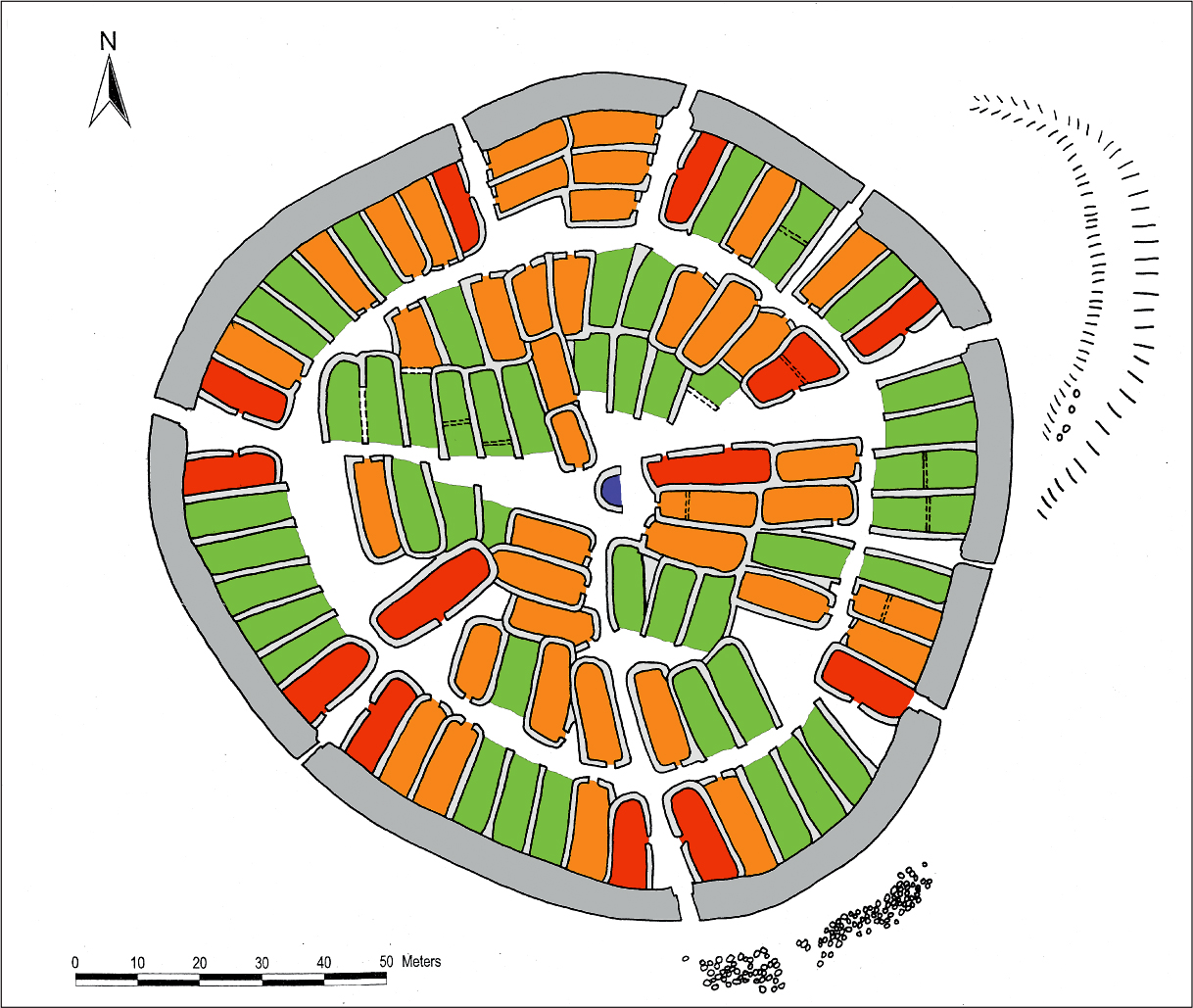

It has not been possible to ascertain the functions of the houses on the basis of the few finds. On the other hand, differences in building methods, which are also known from the historical settlement on the island, can be used to classify the houses broadly into different categories (see Stenberger 1933:93, 104–10). Based on the historical analogies, 55 houses with gable foundations can be interpreted as dwellings and workshops, while 39 houses without gable foundations were probably byres, stables, barns, and stores. The different types of houses can be found in all parts of the fort (Fig. 23).

The areas inside and outside the ring-wall were searched by metal detector and georadar. The metal detector survey only yielded modern objects, whereas the georadar survey basically confirmed a few anomalies that were already visible as shallow depressions. From the results of these surveys, excavations were conducted during two seasons. Test squares were dug in the central parts of ten houses in order to obtain charcoal for dating. Besides this, seven smaller trenches were dug in the open areas between the houses. In the test squares and the small trenches, some charcoal was found, as well as a few sherds of undecorated Iron Age pottery, a few pieces of iron slag, and small pieces of burnt animal bones from sheep/goat, cattle and horse (Sigvallius 1994).

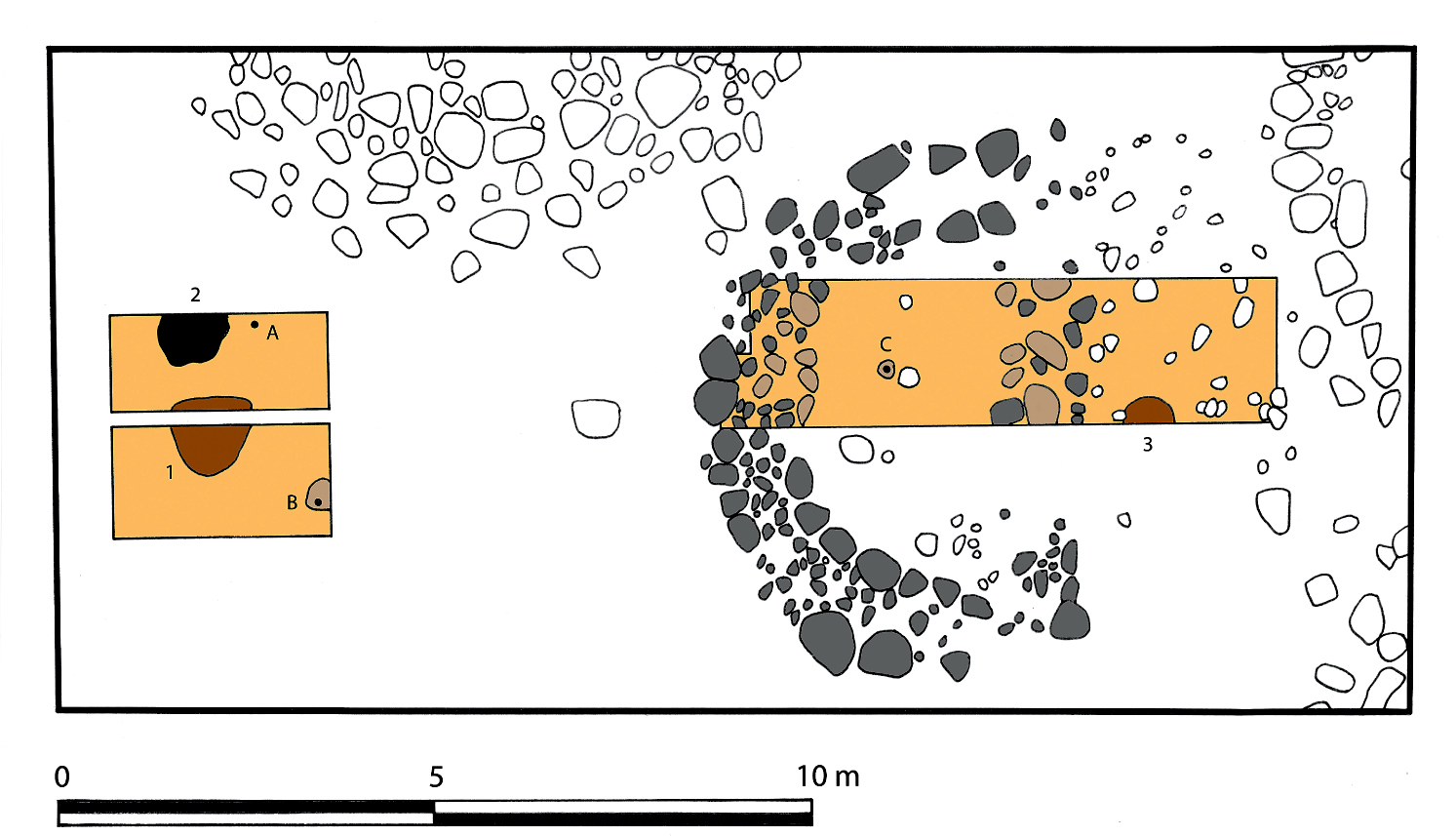

Of special interest in this context are two trenches that were opened in the centre of the ringfort (Fig. 24). The centre of the fort consisted of a triangular open place with a small semicircular house at its eastern end. In the middle of the open area a large pit was discovered, containing earth, charcoal, and unburnt cattle bones. Alongside the pit was a fireplace, and beside the fireplace a bow of an iron fibula of Haraldsted type was found which dates from the middle of the fourth century to the end of the fifth century (Norling-Christensen 1957; Brinch Madsen 1975). Close to the large pit was a lancehead without its socket, deposited in a small pit. With its rhomboid form the lancehead can be dated to the sixth century, according to parallels in a weapon deposit at Balsmyr on Bornholm (Nørgård Jørgensen 2009).

At the east end of the central square the semicircular house was partly excavated. The excavations revealed that the house had been partially destroyed, leaving only impressions of some of the foundations in the ground. Probably the destruction was deliberate, since all other houses are well preserved. In a small pit towards the middle of the house was found a narrow arrowhead with triangular cross-section, but without the point (Fig. 25). Judging by parallels on Gotland, it can be dated to the fifth or sixth centuries (Nerman 1935, fig. 599–600). East of the semicircular house a dugout post-hole was discovered, with stones scattered around the post-hole showing that it had once been stone-lined. The post had been placed between the small house and the houses in the eastern block of the fort.

The nine gates are oriented towards the large pit in the central square, which shows that it was the original geometrical centre of the fort. However, the small semicircular house and the post on the east side of the square were also part of the centre. The two partly destroyed weapons, deliberately deposited in small pits, indicate that small-scale weapon deposits took place in this centre (see Nørgård Jørgensen 2009), but they scarcely correspond to the large-scale rites that Stenberger envisaged in his interpretation of the fort.

Figure 22. Reconstruction of the first phase of Ismantorp ringfort. The reconstruction is based on a rectified aerial photo (see Fig. 21) and on joints between different house foundations. In the first phase all nine gates had access to the centre of the fort. (Plan by the author.)

The dating of the three objects can be confirmed by eight overlapping radiocarbon datings of charcoal. In order to avoid the possibility that the firewood was old in itself, for instance a trunk of oak several hundred years old, only samples of twigs of hazel, sallow, and willow were used. With a 68.2% probability (1 sigma), six samples from several houses can be dated from AD 240–390 to 430–600, and with a 95.4% probability (2 sigma) they can be dated from 130–430 to 420–640. One sample from the pit in the central square can be dated with 1 sigma to 410–560 and with 2 sigma to 340–620, whereas a rubbish heap outside one house can be dated with 1 sigma to 430–610 and with 2 sigma to 430–640. The objects and the radiocarbon datings show that Ismantorp was primarily in use in about 300–600.

Figure 23. Reconstruction of the second phase of Ismantorp ringfort, showing different types of houses. The reconstruction is based on a rectified aerial photo (see Fig. 21). The function of the houses is not possible to determine from the few finds. Instead their construction can give some indication of their different functions. Houses with gable foundations and gable doorways (orange) can be interpreted as dwellings and workshops, whereas houses with doorways on the long side of the houses (red) seem to have had special functions. Most of them flank the gates as some kind of gatehouses. Houses without gable foundations (green) were probably byres, stables, barns, or stores. The semicircular house in the centre (violet) is unique in its shape as well as in its location. (Plan by the author.)

The ringfort was reused later. An Arabic silver coin (Stenberger 1933:239) as well as a small smithy and eleven overlapping radiocarbon datings from the tenth to the thirteenth centuries indicate some form of activities in the historical ruin. Ismantorp was not radically rebuilt during this time, as four other forts on Öland were, but probably most of the gates were blocked and a few houses were rebuilt during this period.

Figure 24. Plan of excavations at the centre of the ringfort at Ismantorp. To the left is a trench in the open triangular place, with a large pit (1), a fireplace (2), and the find spots of an iron fibula (A) and a lancehead (B). To the right is a trench through the semicircular house east of the open place. In the trench was found an arrowhead (C) and a post-hole (3). Besides this, areas with fine humus without till were discovered. These areas probably represent impressions of large stones that have been removed. The preserved visible stone of the small house (grey) and the impressions (light brown) together form a small semicircular house, with a straight east wall. Directly to the east of the house was the post-hole. (Plan by the author.)

After this reuse, there is no documented activity until the seventeenth century. The modern traces represent local hunting and early visits by antiquarians, archaeological campaigns, and modern tourism. Unfortunately, the original name of the fort is long since lost. Its present name derives from the nearest village, which has a typical place-name reflecting medieval colonization, with the ending torp (new settlement) (Hallberg 1985:52).

Figure 25. Finds from the excavations at the centre of the ringfort: from left to right, (A) an iron fibula, (B) a lancehead, (C) and an arrowhead. (Photo by the author.)

Thanks to the fieldwork in 1997–2001, it is possible to outline the history of the fort over a period of 1,700 years. Here I shall concentrate on the first 300 years. Important questions to answer are how the fort was used during this time, and why it was given such a strange design. The answers can scarcely be sought in the fort itself and the few finds encountered there. Instead the site must be compared with those in other parts of Öland as well as in the rest of Scandinavia.

Ölandic comparisons

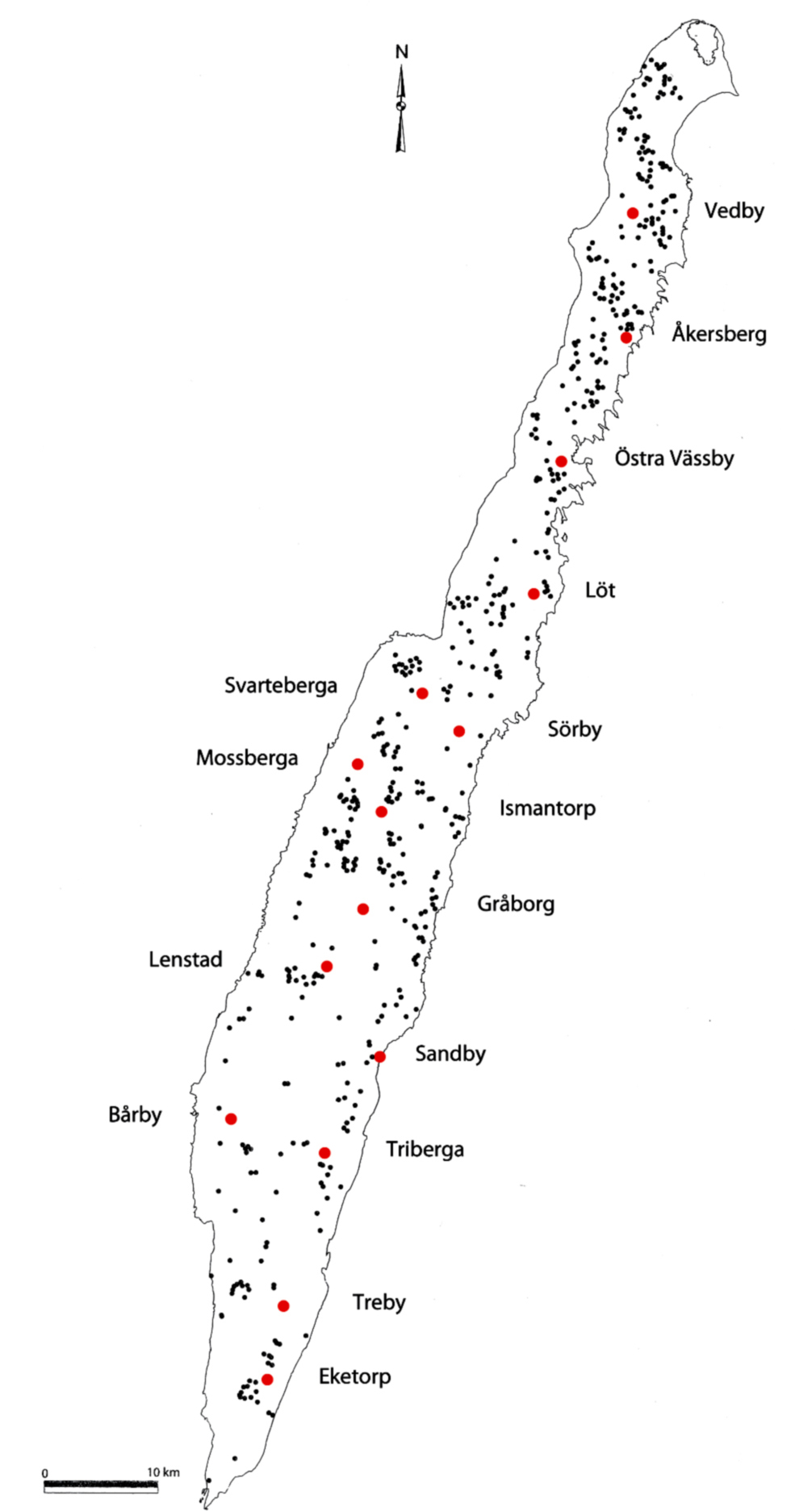

Ismantorp is just one of many ringforts from the Iron Age on Öland. Fifteen of these are still relatively well preserved, whereas three only are known from older maps and antiquarian sources (Stenberger 1933:213 ff.; Wegraeus 1976; Näsman 1981, 1997, 2001; Fallgren 2008). According to the latest survey (Fallgren 2008), three of these ringforts are different in design and location, and can be dated to the late Pre-Roman and early Roman Iron Age, that is, around 200 BC – AD 200. The primary use of the other fifteen ringforts, including Ismantorp, can be confined to about AD 300–650, although most finds can be dated to the period 400–550 (Fig. 26). Some of the sites were subsequently reused from the tenth to the thirteenth centuries. Ismantorp is one of the oldest forts, belonging to a group of at least three ringforts with activity from the fourth century. The early dating of Ismantorp fits well with the experimental and irregular design of the settlement, compared to Sandby (Viberg et al. 2012) and the second phase of Eketorp (Näsman 1976b), which were evidently built according to more explicit models around 400 AD.

The fifteen ringforts on Öland vary in design and size. Bårby is a semicircle placed on a limestone cliff, Treby consists of three small circles in a row, and Lenstad has a semicircular wall around half of the ring-wall, whereas all the others are circular or oval in shape. The smallest forts have a diameter of up to 60 metres, a middle group have a diameter between 60 and 100 metres, whereas the largest group, including Ismantorp, have a diameter of over 100 metres. The largest ringfort is the irregular Gråborg, with a diameter between 160 and 210 metres (Fallgren 2008). The state of preservation of Ismantorp is unique, but virtually every element in the fort can be found in one or more of the other contemporary fourteen ringforts on the island.

Outworks with large granite boulders outside the main gates, as at Ismantorp, are also preserved at Löt and Sandby, and are probably incorporated in the early medieval outer ringwalls at Eketorp and Gråborg. Three main gates, as at Ismantorp, are preserved or attested at Eketorp, Gråborg, Löt, Sandby, and possibly Mossberga (Borg et al. 1976; Tegnér, G. 2008; Viberg et al. 2012; Stenberger 1933). Even the seemingly unique and inexplicable nine gates in the ring-wall of Ismantorp have their counterparts on the island. The first small fort at Eketorp was built in around 300, consisting of a polygonal ring-wall with nine corners (Weber 1976a). The fort had only one gate, but the figure of nine was inscribed in the shape of the ring-wall. Even the large Gråborg seems to have had nine gates in its oldest phase, from about 300. The fort was radically rebuilt in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, when the ring-wall was reinforced and three gates were converted into gate towers (Stenberger 1933:228 ff.; Tegnér, G. 2008a). In the first half of the twentieth century, a fourth gate in the earlier ring-wall was found, indicating another design of the ring-wall in the Iron Age. In order to investigate this older plan, I made a thorough analysis of the masonry of the earlier ring-wall in 2003, with the help of digitized aerial photos, provided by colleagues from the Gråborg project (see Tegnér, G. 2008b). During this fieldwork, I found five more walled-up gates, two between the west and south gates, two between the south and east gates, and one north-east of the west gate. Evidently, Gråborg also had nine gates in the Iron Age.

Figure 26. Map of Öland with ringforts from c.300–650 (red dots) and ordinary settlements from c.200–700 (black dots) (after Fallgren 2006:24 and 2008:125).

Inside the rings-walls, dense settlement is preserved or can be attested in eleven cases (Fallgren 2008). Despite the many house foundations, most ringforts seem to have been used only temporarily, since graves in the surroundings are lacking, as are real cultural deposits inside the walls, although some objects have been retrieved from the different sites. The only clear exception is the second phase of Eketorp (around 400–650), which has been interpreted as a fortified village due to cultural deposits with many objects (Edgren 1979; Näsman 1981).

From other ringforts come accidental finds, such as Roman gold coins from the fifth century, bronze fibulas, and gilded relief brooches of silver (Stenberger 1933:213–55; Palm 2008). The relief brooches found at Mossberga and Sandby indicate the presence of high-ranking women, possibly with the religious function of a seeress or a vǫlva (see Magnus 2001b, 2004). Possible ritual objects include gold-foil figures from Eketorp, a bronze figure of a sitting man found under a stone in the centre of the ringfort at Mossberga, and a bronze figure of a standing woman from Svarteberga (Stenberger 1933:246). Traces of violence and warfare are also present. At Eketorp, arrowheads and extensive burnt layers were found close to the southern gate (Weber 1976b:105–106). At Sandby, two skeletons have been found inside the threshold of two houses (Viberg et al. 2012), whereas weapons such as arrowheads, spearheads, and lanceheads have been discovered in several forts (Stenberger 1933:213–255).

The origins of the objects from the forts attest to different forms of contacts around the Baltic Sea, to Gotland, Bornholm, Skåne, Denmark, and Prussia. Further away, connections with the late Roman or Byzantine Empire are visible in the shape of gold coins and glass vessels (Herschend 1980; Näsman 1984; Magnus 2004). In many ways, the finds from the forts mirror those from the contemporary graves and hoards on Öland.

It is uncertain whether any original name of an Ölandic ringfort has survived. Eketorp in the early medieval phase seems to have been called Gräsgård (Vikstrand 2007), but four forts – Åkersberg, Svarteberga, Mossberga, and Triberga – have names with the ending -berga. This compound is very common for hillforts or settlements close to hillforts in eastern and central Sweden, indicating that these names might be original.

Alongside the ringforts, Öland is also known for its well-preserved traces of ordinary agrarian settlement from the same period, that is, about AD 200–700. Mårten Stenberger conducted the first investigations in the 1920s and 1930s (Stenberger 1933:85 ff.), but the most recent analysis of this agrarian settlement and its relation to the ringforts has been done by Jan-Henrik Fallgren (Fallgren 1993, 1998, 2006, 2008). According to his survey, 1,300 foundations are preserved or known from the outlands of the historical villages on the island (see Fig. 26).The ruins are in many cases still surrounded by abandoned fields, meadows, and cattle paths, all bordered by stone enclosures. The stone foundations correspond to perhaps 1,100 farms, situated in large and loosely organized villages. However, many more farms must have existed, but have been destroyed, because they were located too close to the historical villages and their arable land.

Based on the number and size of the houses, Fallgren has divided the farms of Öland into three different size classes, which also hint at the social order on the island (Fallgren 2006). Over 90 per cent of the stone-foundation buildings consisted of small farms with one or two houses, up to 20 metres long. About 8 per cent of the known settlement consisted of medium-sized farms, with three slightly larger buildings. Finally, there is a small group with decidedly large farms or estates. Accounting for less than 2 per cent of the known stone-foundation buildings, these farms consist of four or five houses, which can be up to 55 metres long (Fig. 27). Often there are also workshops and special free-standing hall buildings (see Herschend 1997) at these sites. In each village, there was normally just one larger farm, and these were chiefly located in the bigger villages with ten or so farms (Fallgren 2006).

The total number of houses in the contemporary ringforts is not known, but has been estimated as ‘at least 1,000’ (Fallgren 2008:124), which is probably too low regarding the inner space in some of the largest ringforts, such as Gråborg and Löt. A figure around 1,200 is more plausible, meaning that most of the inhabitants of the island could have been housed in the ringforts during periods of warfare. However, the ringforts were not refuges in the passive sense that they only reproduced the organization of the agrarian settlement. Instead, the location of the forts as well as their design clearly distinguished them from the surrounding settlement. This means that the ringforts must have represented an organization that was partly different from the agrarian settlement.

Figure 27. Remains of a village from c.200–550, with house foundations and stone enclosures at Rönnerum in Högsrum, about 2 kilometres west of Ismantorp ringfort. The inhabitants of the large farm or manor (houses IV–VII) were probably among the initiators of the building of the ringfort. (After Stenberger 1933:99.)

All the ringforts were placed in outland between the settlements; the smaller ringforts in outland between villages, and the larger ringforts on commons between regions of settlement (Fallgren 2008). Normally, the forts, as in the case of Ismantorp, were situated one or two kilometres away from the surrounding settlements. The forts were nevertheless clearly related to these settlements, since the main gates in several forts were directly facing the closest neighbouring villages. In Ismantorp the three main gates moreover had the same orientation as the three main roads in the surrounding agrarian landscape.

The forts and the villages were thus linked to one another, but at the same time they represented two different ways of organizing a settlement (Fallgren 2008). The obvious ranking of the farms and the tendency to build houses around enclosed yards emphasized hierarchy and enclosure in the unfortified settlements. The forts themselves were enclosed, but the houses inside the forts were relatively small and of equal size, and not placed in closed yards. Inside the ring-walls, the principles of equality and openness are therefore emphasized in the architecture. This combination of enclosed ring-walls and equal-sized houses inside the walls indicates military principles behind the ringforts.

The location of the ringforts between several different settlements must have meant that the initiative to build the forts came from several different villages at the same time, primarily from the large farms that dominated the villages. A collective initiative like this from several different estates could explain some of the differences between the unfortified and the fortified settlement. The forts were erected in outland on a kind of neutral periphery between the settlements, and the equal-sized houses toned down the competition between the estates. Instead the ringforts themselves represented a military order that for periods could replace the social order in the villages.

An interesting aspect of the links between the ringforts and the agrarian settlement is the observation that the size of each ringfort seems to correspond to the number of farms in the area around the fort (Näsman 1997; Fallgren 2008). This means that behind the larger ringforts were larger and more complex networks of high-ranking families from the large farms than there were behind the small ringforts. An outstanding case was the large Gråborg, which must have been the most central place on Öland during periods of war – perhaps representing a petty king of the island (see Näsman 1997).

To sum up, the Ölandic comparisons show that Ismantorp is not as unique and unusual as Stenberger claimed. The fort may be extremely well preserved, but in all other respects the site is deeply rooted in distinct Ölandic patterns. This applies both to other forts and to the relations between forts and ordinary settlement. Ismantorp therefore need no longer be treated as the great exception, which requires different or special explanations. Instead, the well-preserved ruin can be assigned a greater and in many ways more interesting role in the discussion of ringforts.

Scandinavian forts

The fifteen Ölandic forts are just a small proportion of the over 1,500 ringforts and hillforts registered in Scandinavia (Engström 1984, 1991; Taavitsainen 1990; Olausson 1997; Mitlid 2003, 2004). In the Baltic Sea area there are forts on Bornholm, Öland, Gotland, along the east coast of Sweden from northern Småland to central Norrland, around Lake Mälaren, and in south-west Finland. In western Scandinavia, forts are found along the coasts of Sweden and Norway from northern Halland to Trøndelag, in the provinces around Lake Vänern and in the interior of southern Norway. Ringforts and hillforts are thus found in areas of mixed landscape where farming country alternates with areas of forest. In the large plains of southern Scandinavia and in the agricultural districts of central Västergötland and western Östergötland there are virtually no forts.

The form of the forts varies according to the local topography. Ringforts where the walls totally surround the interior of the fort are found above all in flat terrain, as on Öland and partly on Gotland. The most common solution, however, was to place hillforts on cliffs and hills, with walls built along the least steep sections. The walls in these cases are often semicircular. A recurrent feature is the peripheral location of the forts in relation to contemporary settlement. As on Öland, the forts are usually built in outland and common land, some distance away from cemeteries and settlements. In many cases they are situated on later boundaries between parishes or hundreds. Several forts are also located facing lakes or seashores, and only a small group are placed close to settlements and cemeteries (Gihl 1918; Törnqvist 1993; Olausson 1997; Wall 2003:62 ff.; Mitlid 2004).

The link between certain forts on Öland and the place-name Berga and -berga (‘rock, mountain, hill’) has many parallels in other parts of Scandinavia. Besides many hillforts are related to place-names like Borg, -borg (‘fort’), and Sten, -sten (‘stone’). In certain cases the forts themselves have these names, while in other cases it is a nearby settlement that bears one of the names (Karlsson 1900; Gihl 1918; Johansen 1997; Wall 2003:167 ff.; Wahlberg 2003).

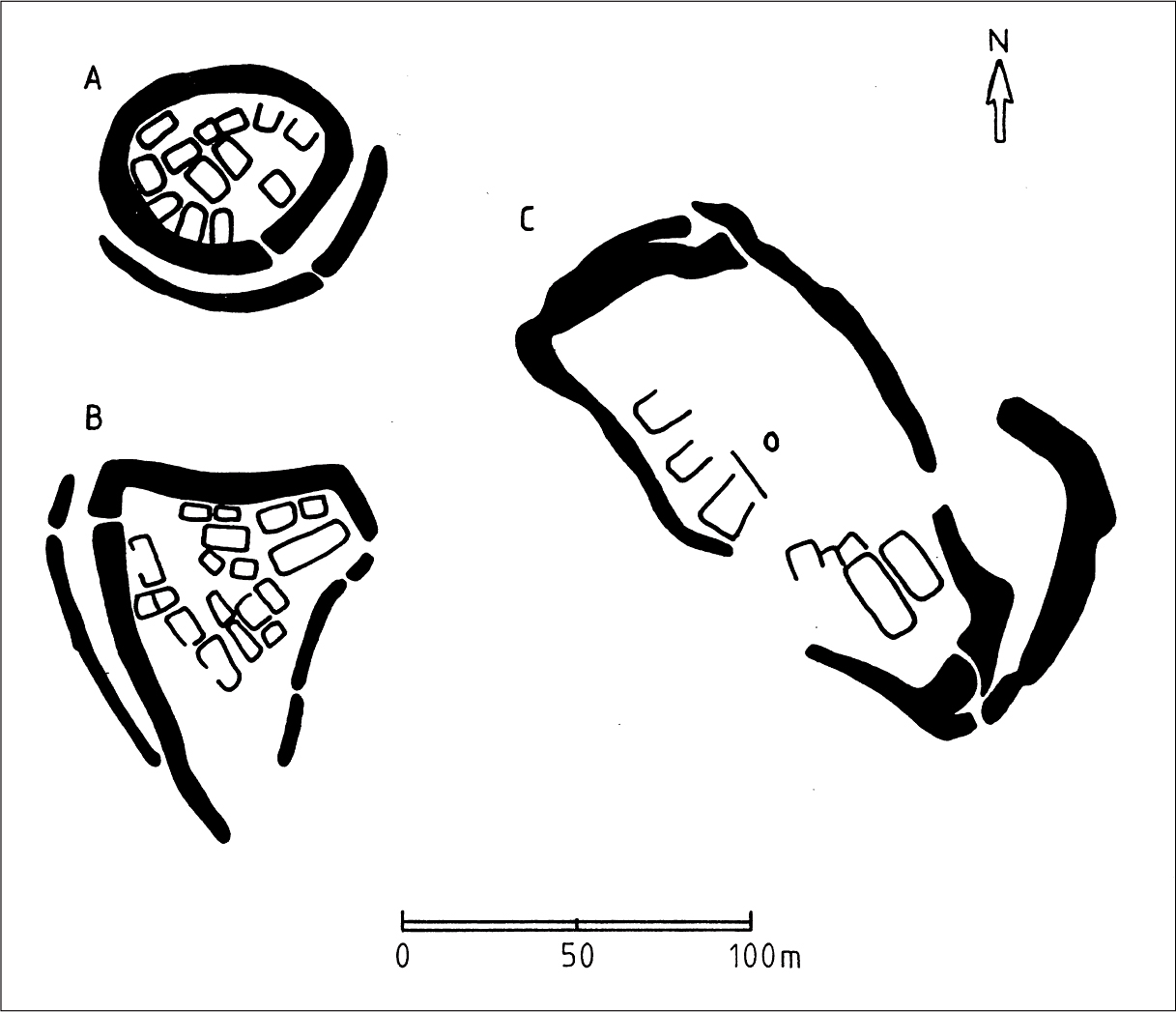

The Scandinavian forts generally date from the Late Bronze Age (c.1000 BC) to the Early Middle Ages (c. AD 1300), but the majority of the excavated sites belong to the period 200–700, and above all the period 400–550 (Olausson 2009, 2011), in other words, exactly the same time as the forts on Öland. There are both similarities and differences between the contemporary Scandinavian and Ölandic forts. Many ring-walls are similar in structure to the walls of Ölandic forts, with step-like ledges on the inside. Unlike the Ölandic forts, however, timber structures, sand, and clay were used in the construction of many hillfort walls (see, for example, Boman 1982; Engström 1984; Olausson 1997; 2009). Outworks with zones of closely spaced granite blocks are common, and as on Öland the openings in the outworks are shifted counter-clockwise in relation to the gates in the main wall. On the other hand, there are rarely more than one or two gates in the forts. An exception is Torsburgen on Gotland, which is one of the biggest ringforts in Scandinavia, with a circumference of about 4.5 kilometres. At least twelve entrances lead to this huge fortified plateau (Engström 1984). The characteristic density of buildings in the Ölandic forts, on the other hand, has no counterpart, although terraces with up to twenty houses occur at some hillforts in Uppland (Fig. 28; Olausson 1997; 2009). Occupation layers with pottery, food remains, craft waste, and the occasional dress artefact have also been found in some forts in Södermanland and eastern Östergötland, whereas finds of weapons are rare (Schnittger 1913; Nordén 1929, 1938; Olausson 1997, 2009). Analysis of animal bones from one site indicates that the hillforts with settlement remains were primarily used during the summer seasons (Olausson 2009:53). Yet the majority of forts lack cultural deposits and finds, so they can best be described as ‘empty places’ established directly on bare rock (see Wall 2003:139).

Opinions about the forts are sharply divided, and, generally speaking, interpretations of them alternate between modern concepts of politics, economics, and religion (Johansen and Pettersson 1993; Flygare 2000; Wall 2003; Ystgaard 1998, 2003; Olausson 2009). There are clear parallels to similar discussions about forts in Britain and Ireland (see, for example, Hill 1993; Stout 1997; Alcock 2003:179 ff.). The different views in the Scandinavian debate are due to the fact that the words used, such as the Norwegian word bygdeborg and the Swedish word fornborg, cover completely different types of structures built in very different historical contexts. In addition, the character of ‘empty places’, with few or no finds, means that many forts lack clear contexts. As a result, the forts are open to diametrically opposed interpretations.

Figure 28. Plan of hillforts in Uppland, with terraces for houses, at Broborg (A), Darsgärde (B), and Runsa (C). (After Olausson 1997:159.)

Ever since the antiquarian tradition of the seventeenth century, the predominant interpretation has been that hillforts and ringforts are ancient structures providing defence against some form of military threat. However, opinions about the purpose of these fortifications have varied widely. The most common interpretation is that the forts were intended for defence against external enemies (for example Rygh 1882; Schnittger 1913; Stenberger 1933:213 ff.; Näsman 1997), but others view them as an expression of inner conflicts (Nordin 1881; Nihlén and Boethius 1933:24, 66; Olausson 1997, 2009; Skre 1998) or as bases for waging aggression outwards (Schnell 1934; Stenberger 1964). They have been regarded as places of assembly for weapon-bearing men (Mitlid 2003), but also as places of refuge for the non-fighting part of the population (Nordén 1938:338; Nerman 1941:155). Some scholars believe that the forts were fortified farms or defensive structures built at estates on private initiative (Ambrosiani 1964:12, 177; Olausson 1997, 2009; Skre 1998; Stylegar 1999). Others instead argue that the forts were expressions of small political units, preceding the medieval Swedish and Norwegian realms (Myhre 1966:193, 1987; Hyenstrand 1981; Damell 1993; Damell and Lorin 1994).

In opposition to the general military interpretation, various alternative views were expressed throughout the twentieth century. With particular reference to the astonishingly civilian character of the finds from several forts, some scholars have stressed the role of these sites as fortified dwelling places, as specially demarcated places of production (Hyenstrand 1984:89 ; Törnqvist 1993), as temporary places of assembly for a population chiefly subsisting on animal husbandry (Anjou 1935), as delimited spaces for people with power and with sacred and esoteric knowledge (Hegardt 1991), and as specially demarcated district centres, associated with the exchange of gifts and meetings with strangers (Cassel 1998:129 ff.). The ritual functions of forts have likewise been emphasized in several different contexts. The arguments for the ritual interpretations are that graves have been found inside the walls of some forts, that large erratic boulders with cup marks are found in a few forts, that the weak walls and many gates in some forts (for instance, Ismantorp) are not suitable for defence, and that sacral place-names can be associated with some forts or the nearby historical settlement (Gihl 1918:81; Nordén 1929, 1938; Stenberger 1933; Schnell 1934; Johansen 1997). From these perspectives, ringforts can be perceived as socially enclosed assembly places where judicial functions, cult, and initiation rites were performed. The walls would then not have been built against enemies, but instead would have marked holy places or symbolic fortifications, intended not just for men but also for women (Johansen 1997; Wall 2003). As holy places, the forts have also been viewed as images of Old Norse cosmology (Johansen 1997; Aannestad 2004; see also Sjöborg 1822:128).

It is scarcely likely that agreement can be reached about the function and meaning of forts, since the words bygdeborg and fornborg are umbrella terms for monuments from such different times and places. Broader and more neutral concepts, such as ‘henged mountains’ or ‘enclosed spaces’ have been introduced to account for the variations of the ancient monuments (for example, Johansen and Pettersson 1993; Wall 2003). However, these concepts may also be viewed as attempts to ‘demilitarize’ the forts, since these efforts are connected to a more or less unconscious desire to define war out of Iron Age society. Since war is not desirable today, it becomes undesirable in the past too, and thereby excluded from the discussion of interpretation (Keeley 1996; cf. Carman 1997; Vandkilde 2003, 2006).

I would not hesitate to view many forts from the period 200–700 in martial contexts, for several reasons. The stout walls and outworks of granite boulder from that period are on the whole difficult to understand in anything other than a primarily military context (Fig. 29), although the forts may have had other secondary functions as well (see Olausson 1997, 2009). Weapons that are found in forts are few, but archaeologists have actually found arrowheads, spearheads, lances, and sword details in several forts. The non-martial finds are not a direct argument against a military interpretation, since the maintenance of an army at the time required a distinct ‘civilian’ element in all military troops (Albrethsen 1997).

The military interpretation can also be supported by analogies with similar, contemporary forts in Scotland (Alcock 2003:119 ff.). About ten named and identified forts, according to statements in annals from 681 to 870, were subject to siege (obsessio), fire (combusta), or destruction (distructio) in connection with acts of war (Alcock 2003:144, 180 ff.). In these historical texts, then, forts occur in obvious military contexts. Of special interest is that burning down a fort was the ultimate sign of conquering a hillfort in Scotland (Alcock 2003:183 ff.), which fits very well with the walls of many hillforts in Sweden having been burnt several times and in some cases completely destroyed in ‘ritual obliteration’ (Olausson 2009:59). In some cases the hillforts have been so heavily burnt that parts of the walls have melted. These vitrified walls have been interpreted as deliberate measures to strengthen the walls (Kresten and Ambrosiani 1992), but the Scottish analogies rather speak in favour of a final destruction of a conquered hillfort.

Figure 29. Section of the hillfort at Rällinge on Fogdön in Södermanland. The main wall is up to five metres high and is partly surrounded by large boulders. (Photo by the author.)

A further argument for a military interpretation is the link between forts and the place-name elements -berga and -sten. In several heroic poems in the Poetic Edda these elements are specifically associated with fighting. The prose text between stanzas 18 and 19 in Helgakviða Hundingsbana II mentions that warriors ‘were sitting up on a cliff’ (sáto á biargi) when they met an enemy army. The mythic places Arastein and Frekastein are also mentioned in Helgakviða Hundingsbana II:21 and 26, and in the prose texts between the stanzas 13–14 and 18–19, as well as in Helgakviða Hundingsbana I:14, 44, and 53 and Helgakviða Hiǫrvarðssonar 39. The hero Helgi Hundingsbani rests after a battle at Arastein, whereas he travels with a large navy to Frekastein, where several of his opponents are killed in a violent battle. But Frekastein is also the scene of negotiations between warring parties. The portrayal of Frekastein in these poems is thus very apt as a description of the function of the forts as military structures.