Pointed ovals, for good reasons, are referred to as ‘ship-formed stone settings’ or ‘stone ships’, and it should likewise be possible to detect ‘tree settings’ or ‘stone trees’ among Iron Age graves. In my opinion it is above all the three-pointed stone settings (also called tri-radial cairns or ‘tricorns’ on account of their concave sides) that could be described as ‘tree settings’ (Fig. 14). These have previously been interpreted as expressions of the three main Old Norse gods, Odin, Thor, and Freyr (Sjöborg 1822:54 ff.; Strömberg 1963), but I believe that an abstract interpretation like this does not consider the more concrete and ‘representational’ character of the external grave forms in the Iron Age. A more concrete interpretation of the tricorns would radically change our potential to investigate tree symbolism from an archaeological point of view. In present-day southern Sweden alone there are about 900 three-pointed stone settings from the Iron Age (Strömberg 1963; Slöjdare 1973; Hyenstrand 1984; Carlsson 1990).

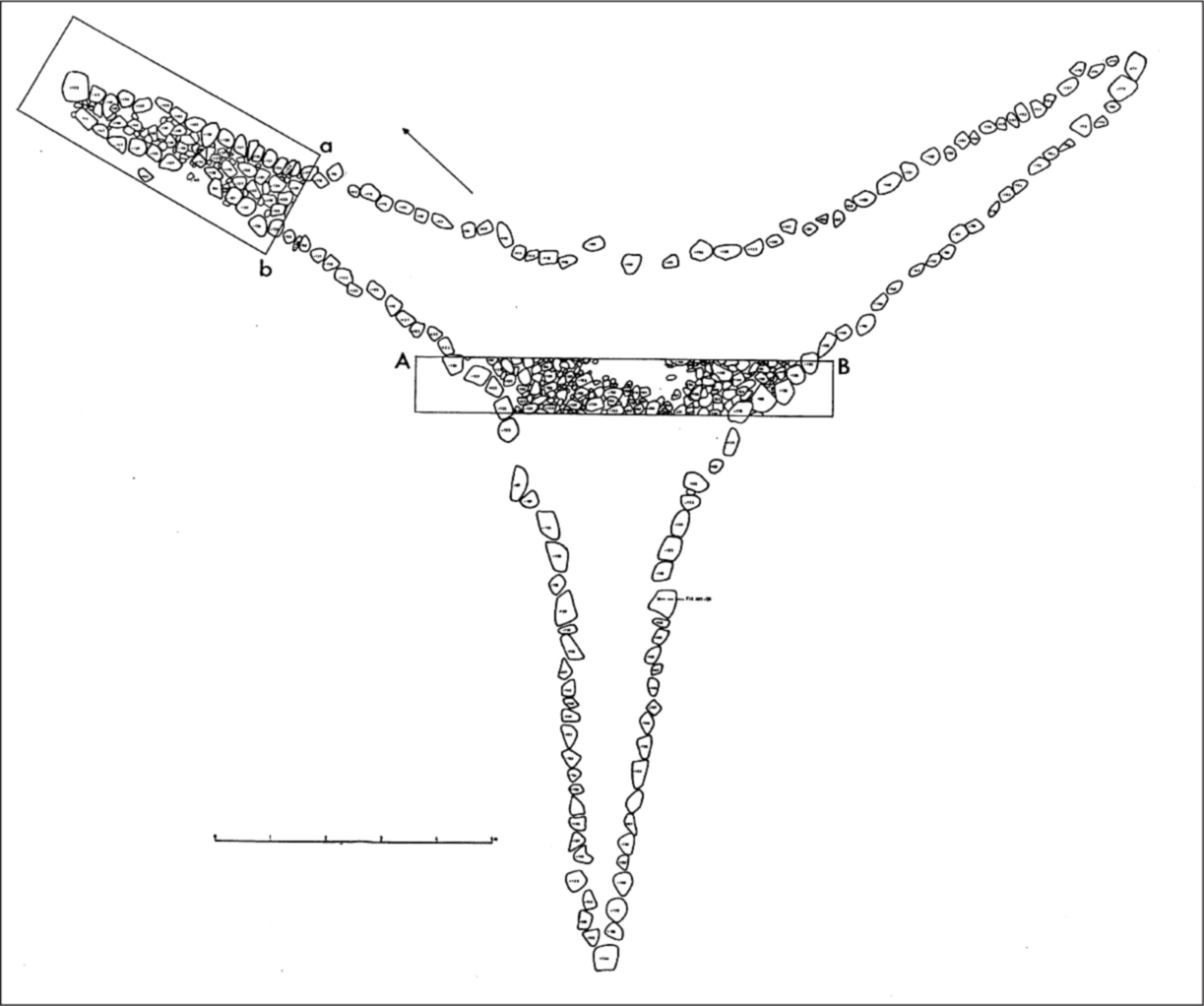

Figure 14. Three-pointed stone setting at Bjärsgård near Klippan in Skåne. (After Strömberg 1963:157.)

The archaeology of ‘tree settings’

There are four arguments for interpreting the three-pointed stone settings as ‘tree settings’: one semiotic, one typological, and two contextual. The semiotic argument proceeds from the unambiguous ship symbolism of ship-formed stone settings. Distinctive stones as stems of the ships, and sometimes stones to mark thwarts and masts, show that the pointed oval stone settings were built to represent ships. There is moreover a written reference, from the rune stone at Tryggevælde on Sjælland, which states that the widow had a ‘ship’ (skaiþ) erected in memory of her late husband (Moltke 1976:182). Stone ships, in other words, show that the geometric figures in the varied language of graves did not correspond to abstract principles, but instead were ‘representational’ images of central phenomena in Scandinavian culture. Stone ships were erected from the Late Bronze Age until the Viking Age, which also shows that the forms of representation could be in use for a very long time, but probably with varying meanings (Crumlin-Pedersen and Munch Tye 1995; Artelius 1996). The example of the stone ships thus opens the semiotic possibility that other graves with geometric shapes were constructed as representations of important cultural phenomena. Besides stone ships, this applies at least to ‘tree settings’ (three-pointed stone settings) and ‘house settings’ (rectangular stone settings, sometimes with convex long sides). In this context, however, I shall confine myself to discussing only ‘tree settings’.

Figure 15. Three-pointed stone setting at Seby in Segerstad on Öland. (Photo by the author.)

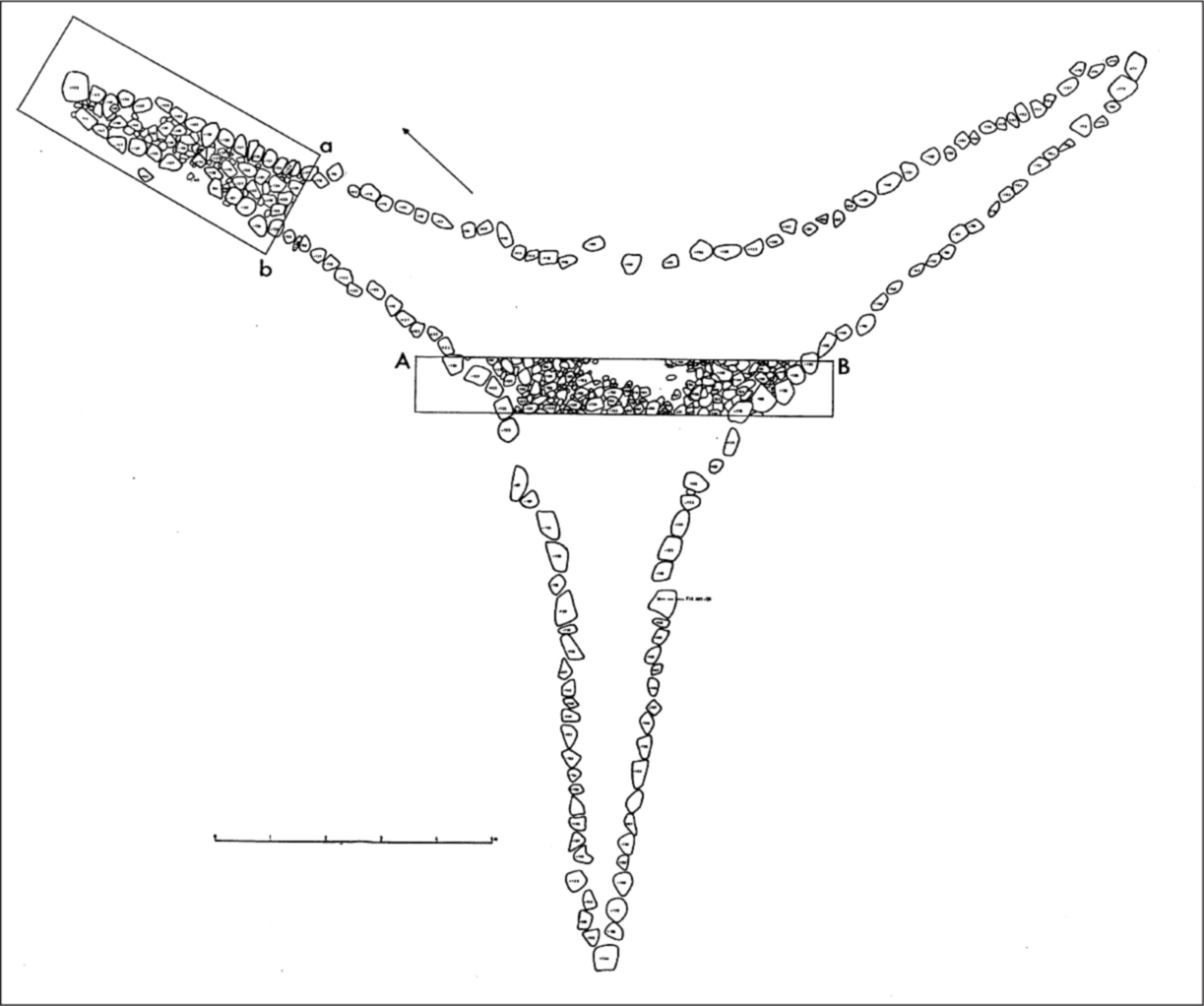

Figure 16. Three-pointed stone setting at Herresta in Odensala, Uppland. The monument no longer exists, but it had a huge monolith in the centre, standing about 3 metres high. (After Dybeck 1865, figure 16.)

The typological argument is based on the similarity in the shape of three-pointed stone settings and descriptions of Yggdrasill. The mythological tree is described in two different contexts as having a crown, a trunk, and three roots which reach out to other worlds. Tricorns can be built up of earth, of a mixture of earth and stone, or entirely of stone (Fig. 15). Irrespective of how they are built, they often consist of long, narrow points ending in a distinctive stone. In addition, there is sometimes a central stone, which in certain cases has the shape of a monolith (Fig. 16). In some Norwegian examples two stones are placed in the centre (Grav Ellingsen 2003). In several excavated monuments a post-hole has been found in the centre, showing that a wooden post could also have stood in the middle. In other words, the three-pointed stone settings may be viewed as representations of the trunk (sometimes of wood, sometimes of stone) and three roots (sometimes of earth, sometimes of stone) of the world tree.

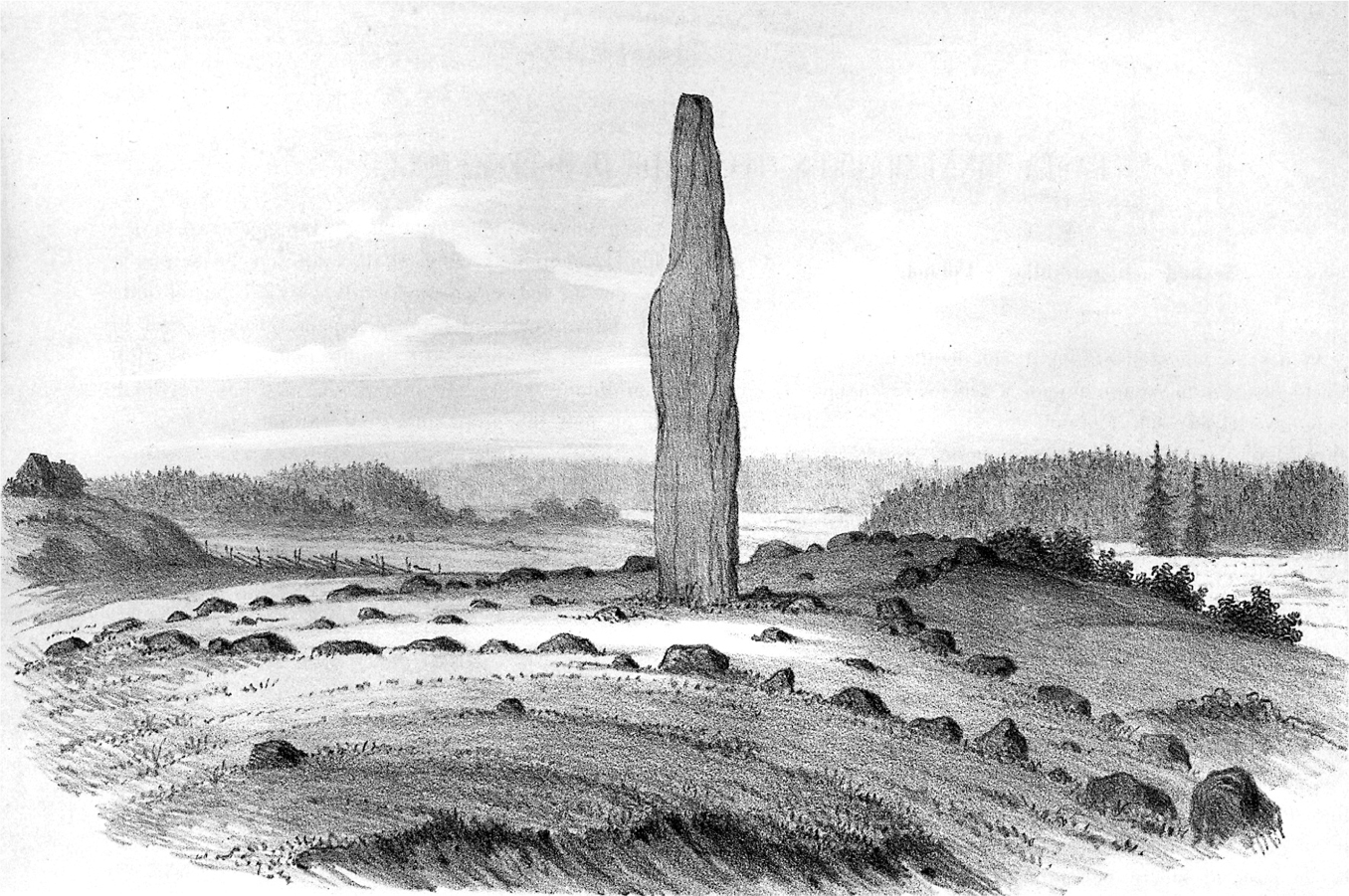

The contextual arguments are based on the placing of the three-pointed stone settings and their content. They are primarily found in Iron Age grave-fields, but in some parts of southern Sweden more than 30 per cent of tricorns are solitaries, showing no connection with any other visible graves. When found in burial grounds, normally just a few three-pointed stone settings occur in each one, and it is not uncommon that there is just one tricorn in a cemetery even when it contains many graves (Slöjdare 1973; Carlsson 1990; Myhre 2005). The tricorns, singly or as groups of a few, are often located at the highest point of the burial ground (Fig. 17). A single three-pointed stone setting can also be the centre of a burial ground, surrounded by distinct groups of graves (Stylegar 2006). In certain cases they are the oldest monuments in the cemetery (for example Petré 1984), and in several other instances they have deliberately been covered by later graves or they themselves overlie earlier structures (Hållans Stenholm 2006; 2012). The occurrence of three-pointed stone settings inside and outside burial grounds clearly demonstrates that they represented special monuments in time and place. In several cases they seem by their date and placing to have been the starting point or the spatial focus of the cemeteries. The special character of the three-pointed stone settings is further underlined by examples from south-western Norway. Two tricorns are found at tun sites, which are discussed in the next chapter, whereas several are found close to churches. One exceptional case is the church at Avaldsnes on Karmøy, which was probably erected on the site of a tricorn. Two monoliths marking two of the points are still standing in the churchyard, one of them being very close to the church wall (Hernæs 1999; Myhre 2005).

In view of the special character of three-pointed stone settings, the finds they yield are surprisingly simple. At least 120 examples have been excavated in Scandinavia, but only about 65 per cent of these have yielded cremated bones and grave finds (Arbman 1940; Ramskou 1951, 1976; Skjelsvik 1951; Kivikoski 1963; Strömberg 1963; Slöjdare 1973; Carlsson 1990; Grav Ellingsen 2003; Myhre 2005). The objects are normally very basic, and in only about fifteen cases do we find the type of objects traditionally used to determine the sex of the buried person. These objects primarily indicate men’s graves, but double graves with both men and women also occur (Slöjdare 1973:13 ff.; Carlsson 1990:28 ff.; Grav Ellingsen 2003; Myhre 2005). About 35 per cent of the excavated three-pointed stone settings contain neither human bones nor grave finds, and in some of these ‘empty graves’ all that is left are hearths and charcoal layers with no remains of cremated bones (Carlsson 1990:27; Grav Ellingsen 2003). The question is whether these monuments were graves at all in the conventional sense, and therefore the tricorns have long been discussed in terms of ‘cultic structures’ (Strömberg 1963). A particularly clear example showing that tricorns did not just mark graves can be found on Helgö, where a tricorn was placed on the terrace mentioned above (with its ritual deposits) where a post had been raised. Since the centre of the tricorn corresponds to the location of the earlier post, the stone setting may have been a new representation of a world tree or world pillar on the site (Zachrisson 2004a, 2004b).

Figure 17. The Kånna Högar burial ground in Småland. The grave-field is dominated by grave mounds, but in the north-western part of the site there are two three-pointed stone settings. The larger one is situated on the highest point of the burial ground. (After Svanberg 2003:190.)

Based on these four arguments, then, I would interpret the three-pointed stone settings as ‘tree settings’, that is, as representations of trees. This means that it is also possible to conduct a more systematic study of tree symbolism in pre-Christian Scandinavia from an archaeological perspective. Tricorns occur primarily in southern and central Sweden and in southern and central Norway. There are occasional sites with tricorns in Denmark and Skåne, in western and northern Norway, and along the Norrland coast in Sweden. Tricorns are found on the Åland islands, but none in mainland Finland, nor in the agricultural districts of Jämtland, Härjedalen, or Dalarna, nor on the islands of Gotland or Bornholm (Ramskou 1951, 1976; Skjelsvik 1951; Kivikoski 1963; Strömberg 1963; Glob 1967; Slöjdare 1973; Hyenstrand 1984; Carlsson 1990; Grav Ellingsen 2003; Myhre 2005). Outside Scandinavia, a few three-pointed stone settings have recently been found in eastern Northumberland, probably dating to the Late Bronze Age (Ford et al. 2002).

In Scandinavia, three-pointed stone settings are very clearly connected to Iron Age cremation customs. Those three-pointed stone settings which contain burials are all cremation graves (Slöjdare 1973; Carlsson 1990; Myhre 2005), with a single exception from the village of Danmark in Uppland (Rundkvist Westholm 2008). At Birka there are about 70 tricorns, occurring only in areas with cremation graves, while inhumations on the island are geographically separate from the tricorns (Arbman 1940; Gräslund 1980). The link with cremation graves can also partly explain the uneven distribution of tricorns in Scandinavia. When graves appear in southern Scandinavia during the Late Iron Age, they were usually inhumations. This means that three-pointed stone settings are found only in areas or at sites where cremation was practised, for example, in northern Skåne and in Danish cemeteries with cremation graves, such as at Lindholm Høje in northern Jutland (Ramskou 1951, 1976; Strömberg 1963; Carlie 1994).

The excavated three-pointed stone settings which can be dated belong to the period from the Late Roman Iron Age to the Viking Age (200– 1050 AD). During this period the form of these monuments changed; instead of having only slightly concave sides the triangles began to be built with more strongly curving sides and distinctly marked points (Carlsson 1990:18 ff.; Myhre 2005). This typological change means that the origin of tricorns can probably be sought in examples of stone triangles with perfectly straight sides, which generally date from the Pre-Roman Iron Age to the Migration Period (500 BC to AD 550). The straight triangles often have larger stones marking the three points and the centre (see Grav Ellingsen 2003). They could therefore also be viewed as a form of ‘tree settings’. Apart from the shape, stone triangles share other similarities with the tricorns. Stone triangles never make up grave-fields of their own: they occur as single monuments in cemeteries. In some cases, moreover, the triangles are among the oldest structures in the cemetery and are at the highest location (Andersson 1996). Like the three-pointed stone settings, they are most common in southern and central Sweden and in central Norway, and they are clearly associated with Iron Age cremation customs (Hyenstrand 1984:81 ff.).

Triangular stone settings also occur among the so-called lake graves, that is, graves situated by lakes in northern Scandinavia, far away from the traditional agricultural districts. The lake graves, which range in date from the start of our era until the Viking Age, are connected to the hunting grounds in the interior of northern Scandinavia. Their cultural background is disputed (Österman 1994; Ramqvist 2007), but some sites with triangular stone settings contain deposits of elk and reindeer antlers. Since these features have been connected to Sámi burial customs, some of the triangular stone settings in northern Scandinavia may have represented hunters and gatherers of Sámi background (Mebius 1968:96; Zachrisson 1997).

To sum up, the interpretation of tricorns as ‘tree settings’ means that tree symbolism persisted for over 800 years. But if we also include the stone triangles, the chronological span can be extended back another 700 years. The stone triangles in the hunting grounds also open the possibility of a Sámi connection. In view of this, the question is how the meaning ascribed to these monuments may have varied in time and place.

The semiotics of the ‘tree settings’

Stone tricorns and triangles may thus be generally interpreted as representations of trees. But the concrete meaning of these monuments has no doubt varied through time and place, in the same way as stone ships had changing meanings (Crumlin-Pedersen and Munch Tye 1995). Clues to the specific meaning of ‘tree settings’ should be sought in a combination of their ‘representational’ character, their connection with cremation, and the local contexts. Crucial aspects in the local contexts are the size and design of the monuments, their special placing, and their content. In the following, I provide some examples of possible cosmological, ritual, and social meanings of the ‘tree settings’. I will do that solely with the aid of the three-pointed stone settings since these are better documented than stone triangles, even though similar meanings can probably be ascribed to them.

The fundamental meaning of three-pointed stone settings can be construed as ‘trees’, and apart from this association with trees, the link with Iron Age cremation customs is a common feature of the tricorns. Interestingly, this was also an aspect stressed in local traditions about three-pointed stone settings in the middle of the nineteenth century. Richard Dybeck states about a tricorn in Södertörn that ‘the old people say that much fire used to burn in the tricorn, and that the fire is still not completely extinguished, although it is only seen on certain nights’ and that this ‘old folk notion’ survives ‘in the whole country’ (Dybeck 1865:25–6, my translation).

When it comes to the more specific meaning of the tricorns, several different scenarios can be outlined. Cosmological significance could be argued for some three-pointed stone settings standing alone, and unconnected to other graves. Sometimes they are highly monumental, stoutly built, with a distance of up to 25–30 metres between the points. They could be used to mark actual trees of a more or less ‘sacred’ kind, especially if they have no grave and originally lacked a central stone. The marking of a tree in these cases need not have had any connection with burials, and an example of this situation is the tricorn on the central ritual terrace on Helgö (Zachrisson 2004a, 2004b).

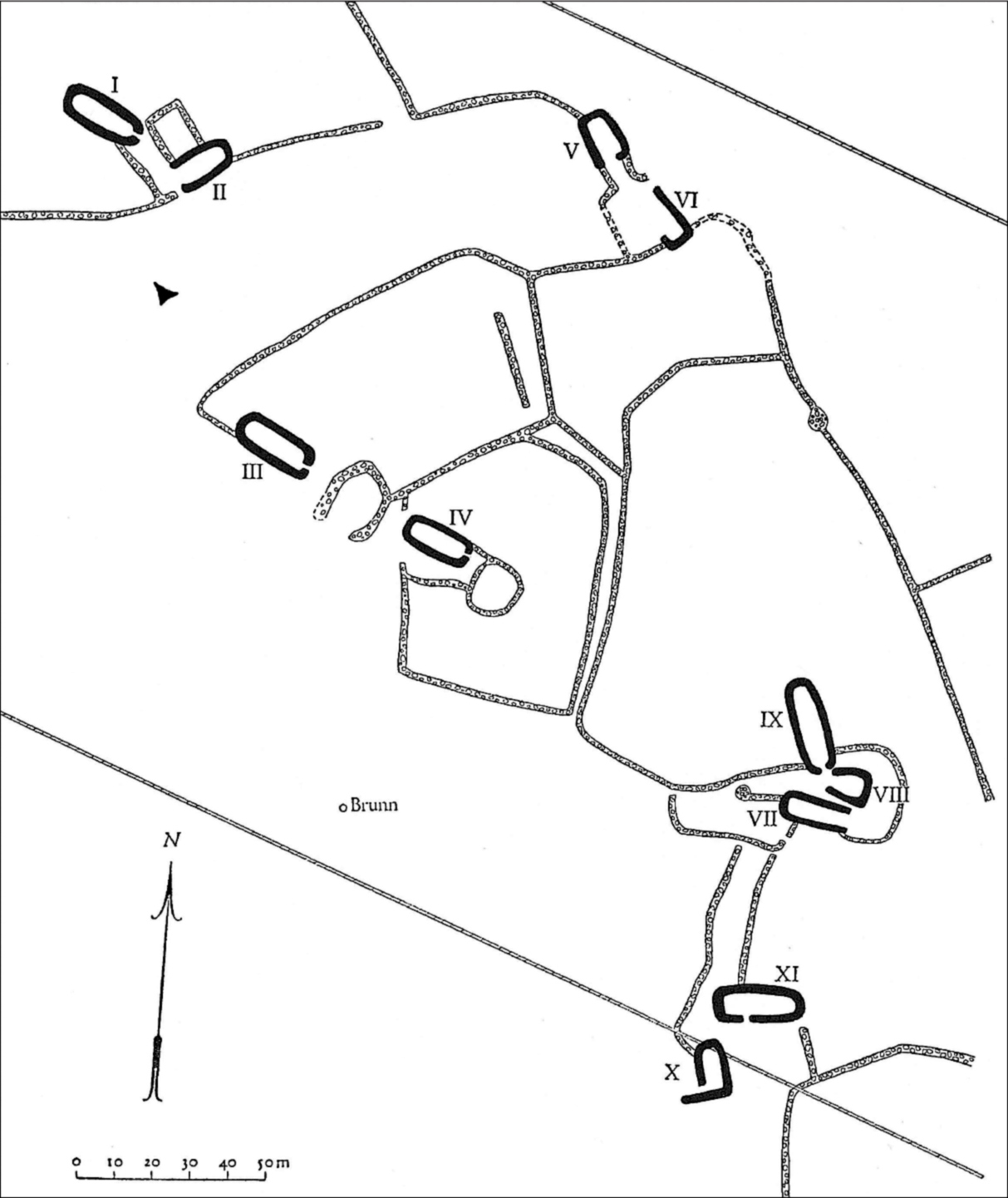

In other contexts, cosmological as well as ritual meanings to the three-pointed stone settings can be suggested. Many cemeteries contained only one tricorn, often in an elevated or central location. Such a three-pointed stone setting can be regarded as the centre of the cemetery, or the focus of the cremation rituals performed at the site. The actual tricorn could have marked a real tree or a post, or it might have been a representation in stone of a tree connected with the cremations on the site. Bearing in mind that some three-pointed stone settings contain only large layers of charcoal, they could thus have marked the site of the actual fire, perhaps evoking associations with the world tree and its fate at Ragnarok. A good example of a centrally located three-pointed stone setting is at the Borre cemetery in Vestfold (Myhre 2003), where the well-known huge burial mounds with cremation graves are placed in a semicircle around a large tricorn, which may have been the ritual centre of the site (Fig. 18). A comparable context, but with a real tree as the focus, is Frösö. Before the church was built there, the excavated birch stood as a votive tree at the centre of a burial ground of barrows (Rentzhog 1987).

Figure 18. The burial ground at Borre in Vestfold. All the famous royal mounds at the site consist of cremations from c. AD 500 to c. AD 1000. The mounds are placed as a kind of semicircle around a large three-pointed stone setting, which can be viewed as the centre of the burial ground. (After Liestøl 1975; see Myhre and Gansum 2003:52–3.)

Social meanings must also have been ascribable to the three-pointed stone settings, since many cemeteries comprise several small tricorns and some of these monuments contain graves as well. On a general level, these monuments could mark the graves of persons connected with ideas about the world tree, the origin of knowledge, the creation of man, and the fate of the world after Ragnarok. The three-pointed stone settings could thus have marked the graves of different types of religious specialists with particular knowledge of the world (Sundqvist 1998, 2007). An argument for this interpretation is that some tricorns contain iron rings with pendants in the shape of a Thor’s hammer (Slöjdare 1973:15, 28; Carlsson 1990:28). Long ago, Nils Henric Sjöborg touched on the idea of religious specialists, as he believed that certain three-pointed stone settings could have been graves for ‘sacrificial priests’ (Sjöborg 1822:55 ff.). But the three-pointed stone setting may also have marked persons connected with the local village tree or farm tree, to which modern-day guardian trees in some sense correspond. The tricorns in these cases could have marked the connection between person, tree, and settlement, especially for a person who ‘founded’ a farm or village with the trees belonging to it. Since a person like this had in a way ‘created’ the world from a local perspective, there could also have been associations with the world tree of the myths.

It is thus likely that several different specific meanings could exist for three-pointed stone settings in the same place. An example of probable parallel meanings for three-pointed stone settings is Birka, where virtually all of the over 70 tricorns are small or very small, while of the 17 excavated monument 13 are graves (Arbman 1940). Following the discussion above, these ought to mark the graves of persons who had special connections with trees and ideas about trees. The four ‘empty’ three-pointed stone settings are in three different burial grounds and may have symbolized the world tree or world pillar in these cemeteries. In Hemlanden, the biggest grave-field at Birka, besides two of the ‘empty’ small tricorns, there is also a very large freestanding tricorn (Arbman 1940, plate I, square N8). This big three-pointed stone setting has not been excavated, but it can probably be interpreted as having been a special focus for cremation rituals in the cemetery. If the small ‘empty’ three-pointed stone settings marked standing posts, the big three-pointed stone setting could have marked an actual tree or perhaps the site of a central pyre for cremations in the cemetery.

The world from the view-point of ‘tree settings’

Place-names referring to solitary trees clearly show that trees were important during the Iron Age in Scandinavia. However, as archaeological objects, trees are truly evasive, and only through the interpretation of three-pointed stone settings as tree settings can we get a glimpse of the importance of the tree. Accordingly, this interpretation has consequences beyond the monuments themselves and the burial grounds where the tricorns are located. In the following I will provide some hypothetical arguments about trees in Iron Age settlements, on the basis of three-pointed stone settings.

Our perception of Iron Age settlement and its relation to Old Norse cosmology can be affected by the interpretation of three-pointed stone settings as well. Traditionally, the solitary farm was regarded as the basic unit of Iron Age settlement in Scandinavia. The solitary farm was therefore viewed as the background to the Old Norse idea of Midgard, as the place of humans in the world (de Vries 1957:272). Archaeological excavations in recent decades, however, have shown that Iron Age settlement was much more complex and varied. It could consist of solitary farms, but also of loosely composed villages (Fallgren 1998, 2006), densely built villages (Hvass 1988), estates (Skre 1998), and large, permanent, central places (Hårdh and Larsson 2002). Yet despite the breadth of variation in settlement, the question remains: what was the basic unit? Was it the farm, the village, or the estate? The three-pointed stone settings, interpreted as a representation of a tree, could shed new light on this debate. Since tricorns do not occur in all cemeteries in any area, their distribution shows that certain cemeteries, and hence indirectly certain settlements, were associated with trees and ideas about trees, while others were not. This difference could be apprehended as a contrast between, on the one hand, settlements with trees or representations of trees which were perceived as ‘the centre of the world’ and, on the other hand, settlements which lacked these associations. In social terms, the difference could be expressed as an estate (with tree and three-pointed stone settings) versus its subject farms (without tree or three-pointed stone settings). This perspective accords well with many of the monumental tricorns in the Mälaren valley as well as in Rogaland and Trøndelag. They mostly occur in cemeteries with large barrows, which in other contexts are usually pointed out as expressions of large farms and estates in the Iron Age (Hyenstrand 1974:22, 1984:79 ff.; Grav Ellingsen 2003:75 ff.; Myhre 2005).

Another field of study, which could be renewed with the aid of three-pointed stone settings, is the relationship between settlement and cemetery. Traditionally, this has been viewed as an uncomplicated one-to-one relationship – that is to say, that one settlement used one burial ground. This is the assumption underlying a great deal of the cemetery-based settlement archaeology (for example, Ambrosiani 1964; Hyenstrand 1974; Wijkander 1983). The excavations of recent years have shown, however, that the situation is more complex, with settlements without graves, with settlements that used several burial grounds simultaneously (Petré 1984), or grave-fields used by several different settlements at the same time (for example, Liljeholm 1999). The latter relationship, in particular, could be illuminated by cemeteries containing several contemporary three-pointed stone settings. An illustrative example is a large Viking Age burial ground at Stora Dalby in central Öland (Beskow Sjöberg 1987:80 ff.). The burial ground contains eleven three-pointed stone settings, which could represent several different villages using the grave-field at the same time. This interpretation is supported by the fact that the cemetery, which is the only securely attested Viking Age cemetery in the area, is surrounded by several villages with names ending in -stad and -by. The burial ground at Stora Dalby may in this way have been a district cemetery in the Viking Age, and thus a forerunner of the medieval churchyards.

A third discussion point, on which the three-pointed stone settings could provide new perspectives, is the relationship between cemeteries, settlements, and place-names. Comparisons between settlements and place-names are often made today on a very general level, since there is a serious risk of circular argument, for example, in attempts to date place-names archaeologically (Lönn 1999; Vikstrand 2001, 2013). However, in contexts where three-pointed stone settings can be interpreted as marking the graves of people who ‘founded’ a settlement with a ‘village tree’ or ‘farm tree’, these monuments could allow new angles on the discussion. In several cases, the three-pointed stone settings belong to the oldest stratum of graves in a continuously used cemetery. The tricorns, as expressions of a newly founded settlement with a ‘village tree’, could then be used to date the adjacent settlement and the name it bears. An example is the cemetery at Lunda on the island of Lovö, where the oldest graves can be dated to the Migration Period (400–550), among them two three-pointed stone settings (Petré 1984). The name Lunda for this place could thus go back to the fifth century. In other cases there are three-pointed stone settings, which were placed over older graves, suggesting a breach in continuity and a renewal of burials and settlement as well as the place-name. An example of this situation is the totally excavated burial ground at Fiskeby in Östergötland (Lund-ström 1965, 1970). The cemetery was used continuously from the end of the Bronze Age, but during the Viking Age (800–1050) two tricorns were placed right over graves from the Early Iron Age. The tricorns can be interpreted as a new occupation of a cemetery that had been used for a long time, and may thereby have alluded to a renewal or new foundation of an adjacent settlement, which may also have been given a new name. The name Fiskeby could thus be dated by means of the three-pointed stone settings to the Viking Age, even though the cemetery as a whole originated in the Late Bronze Age.

A fourth area where this interpretation of tricorns could influence archaeological perceptions and future excavations is Iron Age settlement and its relation to real trees. Three-pointed stones-settings may have been built around special trees or referred to some kind of ‘farm tree’ or ‘village tree’, while trees in place-names simultaneously emphasize the crucial significance of real trees in Iron Age society. It is therefore essential to develop techniques for looking for real trees, and to discuss which indirect traces might hint at the existence of important trees in a settlement.

Trees may have been surrounded by constructions in various ways, such as by cairns, stone settings, and tricorns. An example can be taken from the remains of an Iron Age village at Valsnäs on Öland (Fig. 19). Between stone foundations of the farms, which can be dated to the Late Roman Iron Age and Migration Period (200–550) there is a small solitary three-pointed stone setting (Stenberger 1933:94). Since graves were usually put on the periphery of these villages (Fallgren 2006), this centrally placed tricorn must have had a different function, most probably marking the ‘village tree’.

Figure 19. Remains of an Iron Age village at Valsnäs in Löt on Öland. In the western part of the village there is a three-pointed stone setting. Since graves on Öland normally were located at some distance from the settlements, this three-pointed stone setting is probably not a grave, but more plausibly marks a village tree. (After Stenberger 1933:94.)

The location of trees may also be detected by means of absences, because people due to the holiness probably avoided everyday activities around the local tree. The totally excavated Jutlandic village of Hodde from the late Pre-Roman Iron Age (150–1 BC) could be an example of this (Hvass 1985). The village consisted of farms grouped around an open green, which has been interpreted above all as a place where the village livestock was rounded up. But the open place was not uniform. Large parts of the area contained finds and pits, but an area to the south-west lacked pits and finds, but included a cremation. The area totally lacking finds beside the cremation grave could have marked the site of a central tree on the green.

Another possible way of finding indirect traces of trees is based on the supposition that settlements were organized in relation to an important tree, which means that the site of a central tree should be obvious from the organization of a settlement in time and place. An example of this context could be the totally excavated Jutlandic village of Vorbasse (Hvass 1988; see Holst 2004). The settlement consisted of a village with farms moving a short distance every generation from around 100 BC until around AD 1100 (Holst 2004). The successive movement of the settlement was inscribed in a large circle, and the centre of this circle was a small rise in the otherwise flat landscape. The circular movement may have been dictated by a ‘village tree’ on this spot, which thus could have marked the continuity of settlement, although the farms were founded and refounded every generation.

The tree in Old Norse religion

In this investigation I have tried to show that a conceptual figure such as the Old Norse world tree can be discussed and studied from an archaeological perspective. But the question is what new insights this archaeological survey has yielded in relation to the debate about the world tree in the historical study of religion.

As we have seen, Bugge regards the Old Norse world tree as a Christian idea, while most other scholars perceive the world tree concept as a very archaic stratum of pre-Christian Scandinavian religion, without specifying more closely what this could mean in terms of absolute dating. Opinions about the historical origin of this figure of thought are likewise divergent. Mannhardt sees the guardian tree and the ‘primitive’ cult of animated nature as the original model for the world tree, but without stating where this idea came from. For Holmberg, the ‘civilizations’ in India and the Middle East are the origin of the idea of a world tree or world pillar. De Vries claims instead that the figure of thought belongs to the original Indo-European conceptual core of Old Norse religion. He moreover believes that the idea of the world tree is a variant of a more primordial notion of a celestial axis, with the post-built house as its ultimate model. In contrast, Collinder, and after him Palm and Hultkrantz, point to the circumpolar area as the source of the idea of a world pillar, which could therefore have been communicated to Scandinavians via the Sámi. Hultkrantz declares that the idea goes all the way back to Mesolithic and Palaeolithic round huts with a central post.

Archaeology can scarcely provide any unambiguous answers in this debate, but can be used to put cosmological phenomena in temporal and spatial contexts. When it comes to chronology, an exceptional find like Seahenge suggests that a notion of an upside-down world tree existed in north-western Europe as early as 2050 BC, at the transition from the Neolithic to the Early Bronze Age. In Scandinavia, both oak coffins from the fourteenth century BC and rock carvings indicate a metaphorical link between humans and trees. The indirect traces of tree-trunk coffins in the Late Neolithic (2400–2000 BC) hint at similar ideas from the same time as Seahenge. Certain features of the world tree idea may thus have been very old.

On the other hand, the stone triangles (500 BC – AD 550) and the tricorns (AD 200–1050) are evidence of a successively formalized representation of the Old Norse world tree over more than 1,500 years. It is not until the period from the Late Roman Iron Age to the Migration Period (200–550) that the cosmic tree found a shape that can be recognized in Old Norse literature. It was expressed through the increasingly marked points of the tricorns and through the cosmic image of the Sanda stone (see Chapter 4).

As for the relationship between the idea of the world tree, real trees, representations of trees, and people, there are also certain tendencies that should be highlighted. Real trees are difficult to detect archaeologically, but occasional finds, along with indirect hints and place-names referring to particular trees, underline the central role of trees in relation to the estates and central places of the Iron Age. These trees and posts may be viewed as both models for and representations of the world tree, since the mental world and the real world must have influenced each other in constant interplay. If my hypothesis about Vorbasse is correct, the possible central tree surrounded by a continuously moving settlement could be viewed as an analogy to the various world trees that were associated with the ages of the mythic world. The nine worlds which, according to Vǫluspá, surrounded the ‘measuring tree’ (Schjødt 1992) can thus be perceived as both spatial and temporal if one uses Vorbasse as a model.

The idea of a connection between people and trees may have emerged in the same way in interaction between trees, tree symbols, and graves. Hollowed-out tree trunks were used as coffins perhaps as long ago as the Late Neolithic, and at least in the Early Bronze Age, and once again starting in the Roman Iron Age when inhumation was resumed in southern Scandinavia. Stone triangles and three-pointed stone settings, on the other hand, can be associated with the custom of cremation from the Pre-Roman Iron Age until the Viking Age (500 BC – AD 1050), above all in those parts of Scandinavia where inhumation remained uncommon in the Iron Age. In these links between graves and tree symbols it is possible to see both a source of inspiration and an expression of the idea of humankind’s vegetative origin. In the same way, there may have been an analogy between trees and death in the mental world as well as in the real world. Before the construction of the church over the birch at Frösö, the tree stood as a focus for the surrounding barrow cemetery, just as certain three-pointed stone settings were the central points of grave-fields, for example, at Borre. The placing of the birch and the single three-pointed stone setting can therefore be said to correspond to the mythical tree Lærad that stood by Valhall, which was not just Odin’s residence but also the realm of the dead for fallen warriors.

To sum up, I believe that archaeology above all can demonstrate a complex picture of the Old Norse idea of the world tree, which cannot be reduced to a primordial and unchanging idea. Instead, it is possible to sketch an alternative and more complex scenario for this particular figure of thought and its history. Since trees have been of great significance everywhere, the basis for the idea of a world tree must be sought in the huge metaphorical potential of trees, as ‘unchanging’ but growing constants in the landscape and as a fundamental source for human activity. This universal basis has then been activated differently in various historical contexts. The striking similarities in detail between the Old Norse world tree and ideas about trees in other parts of Europe and Asia indicate some form of historical connection, but how this should be perceived is not obvious.

An archaic stratum in the figure of thought is perfectly possible, especially with Seahenge in mind and its parallels with Old Norse, Sámi, Siberian, and Indian traditions. In the Bronze Age, the oak coffins and the trees depicted in rock carvings hint at ideas about trees with special relationships to humans and birds. The background to these ideas is obscure, but like a number of other phenomena in the Early Bronze Age they may derive from central Europe (Lomborg 1973:112 ff.) and ultimately from the eastern Mediterranean (Kristiansen 2004; Kristiansen and Larsson 2005). In the Iron Age, there was a general spread in the expressions of world trees, in the form of stone triangles and three-pointed stone settings. This spread can probably be linked to the custom of farm trees or village trees, as suggested by pre-Viking Age place-names. But it was not until the period 200–550 that the ex-pressions for the world tree became so formalized that they resemble the descriptions in Old Norse literature. Bearing in mind that this period is characterized by distinctly Roman hybrids in Scandinavian society, it is therefore highly probable that the figure of thought of the Old Norse world tree was crucially influenced by the Roman and Late Roman world, including early Christianity. The similarities to representations of trees in the Mediterranean area and the Middle East may therefore be due to cultural encounters. A result of these interactions may have been that motifs from classical traditions, such as the tree of life and the tree of knowledge, were incorporated into existing Old Norse traditions.

The question of a possible association between Old Norse and circumpolar traditions is difficult to answer with the aid of archaeology. The sometimes striking parallels in the ideas of a world tree suggest that there are connections, but the historical contexts of these parallels are unclear. A relationship between Sámi and Old Norse conceptions about trees is suggested by the triangular stone settings that are found among the so-called lake graves in northern Scandinavia. But since stone triangles occur earlier in the Scandinavian agricultural districts than in the hunting grounds, the parallel grave forms suggest rather that this form of expression was transmitted from Scandinavian to Sámi culture.

In other words, from an archaeological point of view, the Old Norse idea of a world tree seems to be a hybrid, or a figure of thought with many roots. It was gradually built up, partly through interaction with other areas over a long time, partly through interaction between the lived and the thought world. The practice of using real trees and representations of trees has both influenced and been influenced by the conceptual world. In the world of myth, likewise, we cannot find any uniform idea of the Old Norse world tree, since the myths are clearly variations on a theme. The tree has different names, partially different attributes, and occurs in different mythic contexts. These variations may be viewed as expressions of the narrative structure of the myths, but they can also be perceived as expressions of the hybrid character of the figure of thought. The variations, in other words, may be regarded as marking the idea of the world tree as composed of several elements, differing in their origin, history, and context.

Figure 20. The south-west gate at Ismantorp ringfort. This gate is the narrowest of the nine gates that give access to the ringfort. (Photo by the author.)