CHAPTER 5

Placing Old Norse cosmology in time and space

The study of Old Norse religious traditions is a multidisciplinary field of research. Due to its complexity, the perspectives adopted in the field vary quite considerably, resulting in research that is conducted in fundamentally different ways. One example of this, as mentioned above in the introduction, is the various approaches to the Icelandic texts as sources of Old Norse religious traditions. The Icelandic texts are regarded by some as Christian interpretations of an imagined pagan homeland created in a diaspora culture. For others, the Icelandic narratives are viewed as an important source for fundamental pagan worldviews and practices with a very long history. Yet others see the Icelandic texts as mirrors of a more recent pagan past, at most going back to the sixth century AD.

The three perspectives seem incompatible, but the paradox is that all three of them are in some sense correct. The Icelandic texts, which contain the main written sources about Old Norse religion, are certainly fundamentally Christian. However, they also contain important references to pagan practice and pagan worldviews, as has been confirmed by recent archaeological research. In contrast to the Christian frame of the texts, it seems plausible that some elements in the texts are very old indeed. Classical authors, as well as linguistic and archaeological indications, point to a time perspective reaching beyond a millennium. However, a close correlation between the texts and material culture can only be maintained during the last centuries before the conversion, above all from the sixth and seventh centuries onwards.

Different trajectories

In the three main chapters of this book, I have tried to show how this paradox can be solved, by following three different cosmological elements through time and space. The notions of the world tree, the world, and the sun were all aspects of Old Norse cosmology, but had partly different trajectories over time. Although a possible representation of a world tree is known already at Seahenge in England as early as around 2050 BC, this motif remains elusive in Scandinavia for a long time. There are hardly any trees in the rock carvings from the Bronze Age. It is only from the fifth and fourth centuries BC that triangular stone settings, which can be regarded as tree representations, appear. The tree motif then became more distinct, with the three-pointed stone settings appearing around AD 200, and images of a cosmic tree from around AD 400, and ritual trees from the ninth and tenth centuries known from archaeology and written descriptions. Probably early place-names with names of different trees as their first element can be connected with early ritual trees, in turn associated with the idea of a world tree. The motif of the world tree seems to have been built up through the centuries until the time of the conversion. This is also reflected in the tree having a very strong position in the later Icelandic written tradition.

The notion of Midgard, or the world in its totality, is much more difficult to follow in material representations, because of the complexity of such a figure of thought. There are indications from around 1000 BC that hill forts, or so-called henged mountains, were built and used in central Sweden in accordance with anthropocentric worldviews. Otherwise, representations of the world can only be traced in circles of erected stones. Usually the numbers of stones are odd, often seven or nine. Sometimes the height of the stones varies according to the location of the stones in the circle, the tallest being placed in the north and the shortest in the south (Fig. 68). These monuments are difficult to date; some are probably as old as the first centuries BC, whereas others are from AD 200–550. The motif reflected in these circles of erected stone was transformed into complex ringforts on the island of Öland. In at least three cases, these ringforts were built with nine edges or gates, Ismantorp being the best preserved. After the sixth and seventh centuries these representations disappeared. Instead expressions of Old Norse worldviews became much more associated with central places, and the large halls that dominated these locations. These cosmological ideas probably go back to the third century, but became more dominant through time (Hedeager 2001; Sundqvist 2004). Ideas about Midgard consisting of several different worlds, sometimes numbering nine, survived in the later written Icelandic tradition, but a much stronger emphasis was put on gods and goddesses having different divine abodes in large halls.

In contrast, the solar cycle has a very different history. The sun, as a fundamental natural phenomenon, had a clear role already in the Neolithic. Sunset and sunrise at different times of the year were used as points of orientation for large monuments in many parts of Europe. However, at the start of the Bronze Age in the seventeenth and sixteenth centuries BC, a more specific Scandinavian solar tradition was created, with the sun-horse and the divine twins serving as central figures. In the eleventh century BC, this tradition was transformed, with ships, snakes, and aquatic birds becoming new elements. Later, from the fifth century BC, many elements of the solar cycle disappeared, and the sun was represented symbolically in the form of sun-wheels or as concentric circles only. In a final phase, AD 300–550, the sun, the divine twins, and the ships were again clearly expressed in metalwork and on picture stones. Place-names with a sol- prefix probably also date from this period, indicating sun rituals as well. After the sixth centuries, the sun more or less disappeared as a cosmological and ritual element, and only faint echoes were preserved in the Icelandic narrative tradition.

In all the three studies, changes over time have been interpreted as hybridizations in the form of variations, incorporations, and reinterpretations. These interpretations are based on the idea of culture as a gradually changing patchwork. Although hybridizations were constantly taking place, it seems that some periods as well as some regions were more decisive than others. Clusters of changes occur in specific periods, followed by other phases with fewer changes. Since these clusters of changes have geographical locations as well, they also tend to create more homogeneous regions for longer or shorter periods. In my three cases such clusters of changes can above all be located in the Early Bronze Age, probably the Early Iron Age, the first part of the late Roman Iron Age, and the Migration Period. In order to indicate how such a cluster of changes worked out, I will in this context dwell on the Migration Period. I have selected this time frame since it is decisive for several of my case studies, and since a number of archaeologists have argued that a new form of ‘Æsir religion’ was introduced in Scandinavia during the Migration Period (Bennett 1987; Hedeager 1997, 2007, 2011; Kaul 1998, 2004). Irrespective of whether the changes that took place during this time should be framed in such a way, the transformations in the Migration Period undoubtedly had fundamental consequences for Scandinavian society in general as well as for the later Icelandic narrative tradition.

The Migration Period as a cluster of changes

The Migration Period (AD 400–550) has for a long time been an enigmatic period in Scandinavian archaeology. The turbulent political events in central and southern Europe are well known, for instance the short-lived Hunnic realm, the replacement of the West Roman Empire with a number of Germanic kingdoms, the expansion and contraction of the Byzantine Empire, and the final expansion of Slavonic rule in eastern and south-eastern Europe (see Fig. 60). Many Scandinavian archaeologists have assumed that these fundamental changes must have affected Scandinavia in different ways. Above all, the Roman gold coins, the solidi, and other gold objects found in southern Scandinavia indicate long-distance connections with the late Roman army as well as different barbarian groups that received huge gold tributes from the Romans. However, the extent to which Scandinavia was part of the turbulent European history has remained uncertain.

An aspect of this enigmatic character of the Migration Period is whether this archaeological period should be regarded as the start of a new era of as the end of an old phase in Scandinavia. In Danish archaeology, the Migration Period is usually regarded as the start of the Late Iron Age, since the division of periods is basically defined from objects. Since the distinct animal art was created in the fifth century and used well into the twelfth century, the Migration Period is regarded as the beginning of a new era. However, in Swedish and Norwegian archaeology, the Migration Period is usually viewed as the end of the Early or Middle Iron Age, because the archaeology is much more concerned with studies of settlements and land use. The distinct stone-enclosed settlements were gradually abandoned at the end of the Migration Period, as were many of the hillforts and ringforts. Many settlements and some burial grounds were also relocated in the sixth century. Therefore, the Migration Period is viewed as the end of an expansive period, starting in the Roman Iron Age.

I have no intention to analyse all the problems of the Migration Period in full, but I will illuminate the paradoxical character of the period by using two recent discussions. One concerns a possible Hunnic conquest of Scandinavia in around 400 and the other a possible climatic disaster in the 530s. Moreover, these studies view the Migration Period from different perspectives, as a start or as an end of an era.

The Huns

In a recent provocative study, Lotte Hedeager argues that the Huns conquered southern Scandinavia in the late fourth or early fifth centuries (Hedeager 2011, cf. 2007). According to her, this conquest triggered the creation of animal art and was decisive for the late Old Norse religion, above all regarding the character of Odin, who she sees as modelled on the Hunnic king Attila. In many ways, she is returning to older discussions on eastern influences in Scandinavia during the Migration Period (see Salin 1904; Janse 1922), but her ideas have been ignored, met with scepticism (Ramqvist 2012), or firmly criticized (Näsman 2008b, 2009). However, I find her ideas interesting for two reasons of principle. Firstly, Scandinavian archaeologists usually underline the Scandinavians as active in long-distance connections. Kerstin Cassel has recently criticized this standard motif – that it is always Scandinavians ‘returning home’ from distant foreign regions who introduce new ideas to Scandinavia (Cassel 2008). Although we know that Scandinavians ‘returned home’, for instance during the Viking Age, Hedeager’s ideas open up for foreigners of non-Scandinavian origin having had a decisive influence on the Scandinavian past. Secondly, most Scandinavian archaeologists today look south or south-east, and ultimately to the Mediterranean when looking for foreign models and inspirations. Instead, Hedeager’s ideas are much more connected to older archaeological and art-historical discussions, where south-east Europe, the Black Sea, and ultimately central Asia and China are underlined (see Salin 1904; Janse 1922; Holmqvist 1980). It is also interesting that her Hunnic thesis adds a possible non-Indo-European aspect to Old Norse religion.

However, the empirical basis of Hedeager’s thesis is somewhat elusive. Her best argument for a Hunnic conquest of south Scandinavia is the late Roman author Priscius, who mentioned that Attila ‘ruled even the islands of the Ocean’, which can be interpreted as islands in the Baltic as well as the Scandinavian peninsula (Hedeager 2011:192, but cf. Näsman 1984:99 ff.). The archaeological remains in Scandinavia of a possible Hunnic conquest are more difficult to discern, and consequently an issue that has been critically examined (Näsman 2008b; Ramqvist 2012). No material culture that has been labelled as ‘Hunnic’ (cf. Werner 1956; Anke and Externbrink 2007) – such as deformation of heads, large copper cauldrons for cooking meat, pendant bronze mirrors, and plain gold earrings – have been found in secured contexts from the Migration Period in Scandinavia (Hedeager 2007, 2011; Näsman 2008b; Ramqvist 2012; cf. Ljungkvist 2005).

Since objects may have been moved over long distances for several reasons, the best arguments for some kind of Hunnic connection are a few distinct grave deposits of riding equipment from around AD 400. Such deposits have been found in present-day southern Romania, eastern Austria, western Ukraine, southern Poland, and southern Sweden, at Sösdala and Fulltofta in Skåne and at Vännebo in Västergötland (Fig. 59). For a long time now, these finds have been used in the discussion of a Gothic connection to southern Scandinavia (Norberg 1931; Åberg 1936; Forssander 1937), but Charlotte Fabech has demonstrated that they represented groups of mounted warriors in south Scandinavia that practised a specific form of ritual otherwise known in central and south-east Europe (Fabech 1991a; 2011). These grave deposits are not Hunnic in a narrow sense (see Werner 1956), but rather expressions of a hybrid culture created in the Hunnic realm, in the forced encounter between steppe nomads, Germanic groups, and a Romanized population. Whether the grave depositions represent a Hunnic conquest (Hedeager 2011:203), or returning Scandinavians from ‘multicultural barbarian societies beyond the disintegrating Roman empire’ (Fabech 2011:34) is a matter of minor differences. The rituals may even have been carried out by foreign, including Hunnic, mercenaries, enrolled by local Scandinavian rulers (see Andrén 2011b). What is important in this context is that they clearly express connections between southern Scandinavia and the Hunnic political centre in south-east Europe (Bemmann 2009).

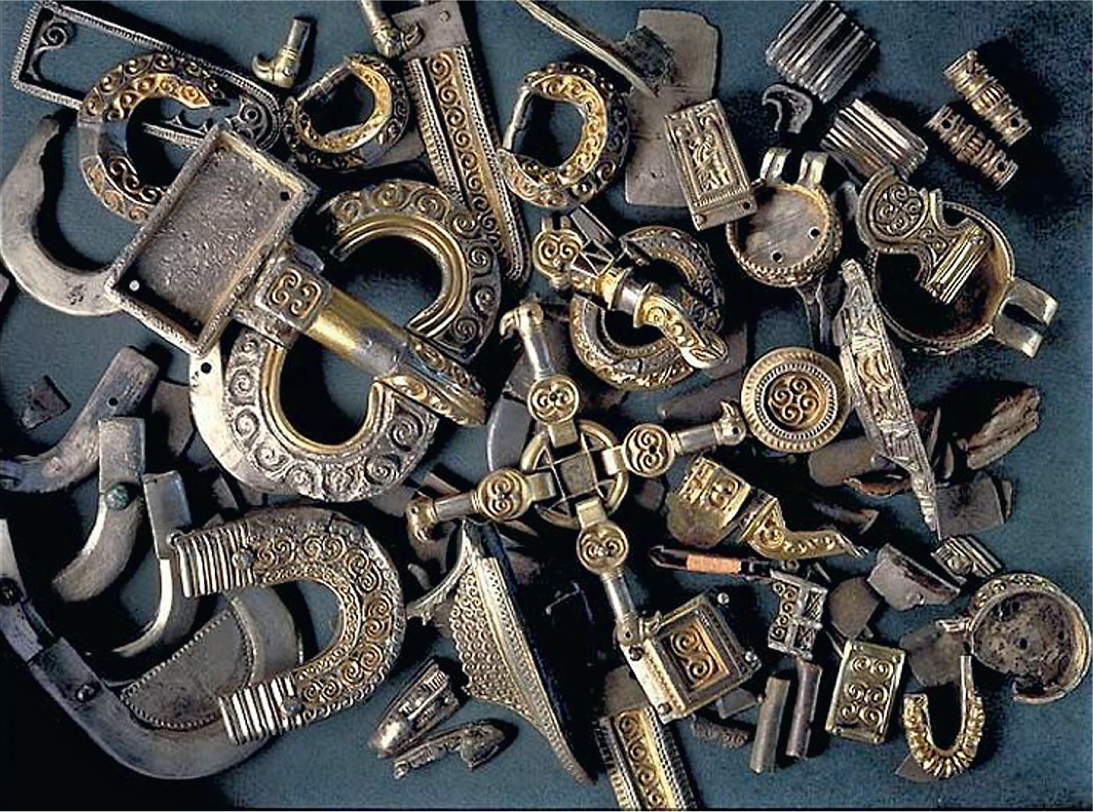

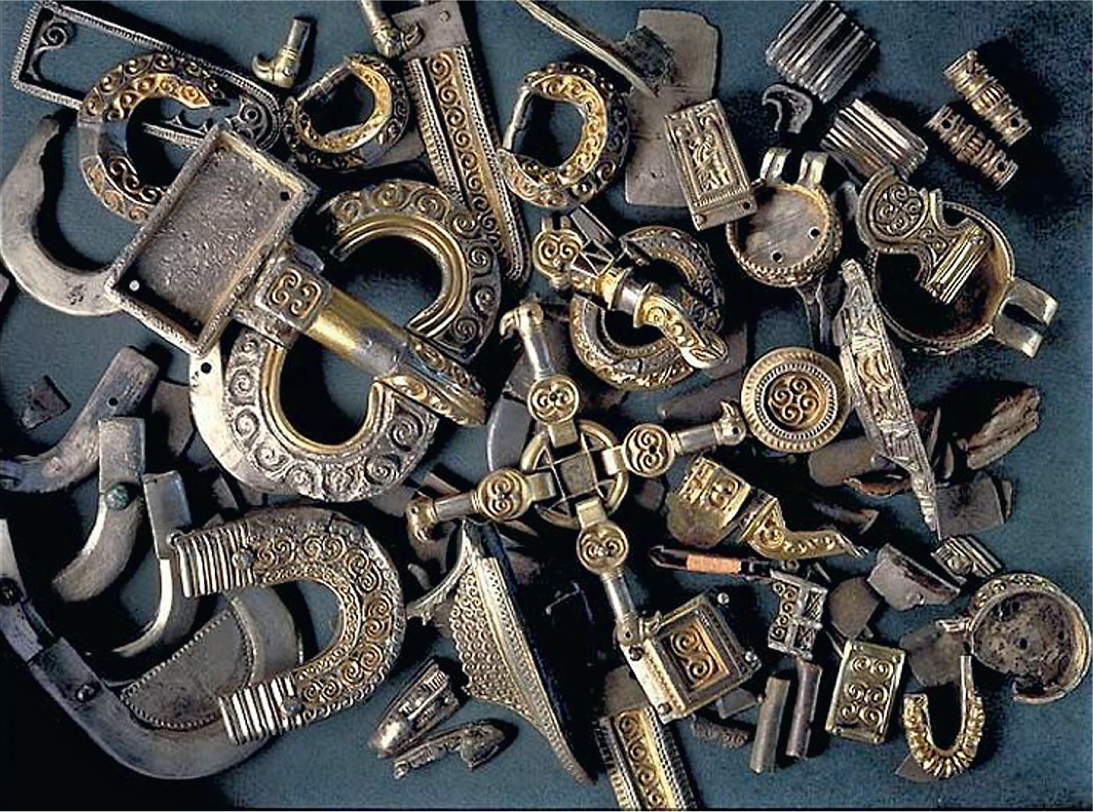

Figure 59. The hoard from Sjörup in Häglinge in Skåne. The objects are dated to the first half of the fifth century, and are decorated with an early form of animal art, sometimes called the Sjörup style after the hoard. The mount in the middle, with four bird heads, has parallels in south-east Europe and the Caucasus (see Werner 1956, table 47), thereby showing links with central and south-east Europe, dominated by the Huns. (Photo by Sören Hallgren, Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm.)

The Hunnic conquest of Scandinavia will remain a hypothesis, but it is not a necessary precondition for Hunnic elements in Scandinavian animal art and late paganism. Since the Huns clearly dominated east and central Europe from the 370s to the 450s (Anke and Externbrink 2007), Scandinavians had to accommodate to this political entity as they had done with the Roman Empire previously, and continued to do with the Byzantine Empire. Since Roman models were incorporated and reinterpreted in Scandinavia without a Roman conquest, similar processes may have been at work during the short Hunnic dominance of east and central Europe.

Early animal art clearly has a hybrid character, which means that there will never be any definite model as a single origin. It includes Roman chip-carved design, which in itself was a hybrid expression, including Roman motifs as well as ‘barbarian features’ with animal heads as end motifs (Böhme 1986:48). The design is interpreted as an expression of the ‘barbarization’ of the late Roman army during the period 375–425 (Böhme 1986), with a large proportion of non-Roman soldiers, of Germanic, Sarmatian, and Armenian but also Hunnic origins (Elton 1996). However, the Roman chip-carved design was only ‘one root’ of animal art (Böhme 1986:25), and other models may have been of Germanic (Werner 1966; Roth 1979:44), Sarmatian (Lund Hansen 2003b), or Hunnic origin. Especially a possible central Asian background needs further consideration, because the standard survey of animal art (Haseloff 1981) was written long before central Asia was opened to new excavations, yielding very interesting results concerning animal art in the Xiongnu empire (Erööl-Erdene 2011; Leus 2011). It is disputed whether Xiongnu (reconstructed as ‘Hunnu’ in Old Chinese) was linked with the Huns, but central Asian sources equate the two names. Besides, both groups used similar copper cauldrons, and deposited them in similar ways in riverbanks (Miklos 1993). If the Huns partly originated from Xiongnu, a further important aspect can be added to the issue of Huns. The Xiongnu empire was an urbanized society, clearly influenced by China (Brosseder and Miller 2011), meaning that the Hunnic invasion of central Europe was not just a ‘barbaric storm’, but an invasion of urbanized steppe nomads.

The enigmatic divine figure of Odin has been discussed for over a century. Although most scholars agree that Odin is an old figure with ecstatic aspects, indirectly mentioned as the Germanic high god Mercury by Tacitus as early as AD 98, the complex character of Odin is difficult to explain and is without counterpart in other comparable religious traditions. Therefore, aspects of the god have been regarded as modelled on the Gallo-Roman cult of Mercury, the Roman cult of emperors, the Roman Mithras cult, or a nomadic shaman-god incorporated by Germanic warrior groups in south-east Europe (Kaliff and Sundqvist 2004; Hultgård 2007a).

Hedeager adds new arguments to this debate, but little is known directly about Hunnic religion, which means that she has to use fairly weak Mongol analogies in her arguments for a Hunnic origin of the shamanistic traits of Odin (Hedeager 2011:196). However, if we accept that the Huns spoke a Turkic language (see Heather 1995) a few other aspects of Hunnic religion may be added. The Hunnic personal names of two high-ranking men, Atakam and Eskam, are probably based on the Turkish word qam, which means shaman. Therefore, ‘shamans seem to have belonged to the upper stratum of Hun society’ (Maenchen-Helfen 1973:269). There are also indications that the Huns regarded Attila as a sun, possibly with inspiration from the Roman imperial cult of Sol Invictus (Maenchen-Helfen 1973:272). Therefore, shamanistic and solar aspects may have been added from Hunnic sources to Odin’s already complex divine figure.

Hedeager has clearly renewed the debate about the Migration Period, animal art, and late Old Norse religion, although the issues need further consideration, not least the possible central Asian connections. However, in one respect I cannot agree with her, namely that the animal styles represented a longue durée from 400 to 1200 that ‘consciously or un/sub-consciously reflect cosmological structures in pre-Christian Nordic societies’ (Hedeager 2011:75). Her perspective is based on current ideas that animal styles were not neutral decorations, but had fundamental meanings (see Kristoffersen 1995, 2000; Hedeager 1997). Generally speaking, I agree with this perspective, but I find that this close connection between animal styles and pre-Christian religion gives animal art too specific a pagan meaning. Hedeager uses figurative representations on metal, above all from the Merovingian Period, to interpret the animal styles in one longue durée (Hedeager 2011:66 ff.), but the Gotlandic picture stones clearly indicate more varied contexts. The picture stones were erected from probably the fourth to the early twelfth centuries and included figurative representations as well as animal art. As I have argued above and elsewhere (Andrén 1993), the figures can be associated with solar aspects as well as more classical Old Norse traditions and Christianity.

Following earlier scholars, I rather see animal art as a parallel to writing and skaldic poetry (Andrén 2000a; cf. Söderberg 1905; Lie 1952; Gurevich 1985). As a consequence, I regard animal art as a figurative discourse, with a much more open and contextual meaning. Each style has to been interpreted on its own terms. The early styles are very different from late styles, such as the Ringerike and Urnes styles. The late styles lack the divided humans and animals, and are dominated by motifs that have been convincingly interpreted as Christian symbols (Horn Fuglesang 1986). Only such open and contextual interpretations can explain the fact that animal art was used for 200 years in obviously Christian contexts (see Staecker 2011).

A good analogy is skaldic poetry, which was clearly linked to Old Norse mythology. At the same time it could be used without problems in Christian contexts (Clunies Ross 2007). Another analogy of a similar open discourse is runic writing. As mentioned above, the names of the runes clearly show that runic writing was embedded in pagan worldviews from the start. In the long run, however, runes were used in many different contexts, thereby transcending the pagan origin of the writing system (Jansson 1977:166 ff.; Benneth et al. 1994; Fischer 2005). Besides, the runes represent an even longer Scandinavian longue durée than animal art, covering in general 1,200 years from the second century to the fourteenth century – and in some regions continuing well into the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. Consequently, I think that Hedeager puts too much weight on animal art when trying to frame late pagan Scandinavia as a continuum from about 400.

The dust veil

For a long time Scandinavian archaeologists have discussed a possible crisis in the sixth century, at the transition between the Migration Period and the Merovingian Period. The background to this debate was that many of the houses built on terraces or stone foundations on Öland and Gotland and in Hälsingland and Rogaland seem to have been abandoned at the end of the Migration Period. Moreover, many of the Swedish and Norwegian hillforts and ringforts fell out of use at the same time. In several regions the number of graves in the Merovingian Period declined considerably as well. Usually the crisis was regarded as an expression of warfare and political unrest, leading to plundered and destroyed settlements and a decreasing population (see, for instance, Stenberger 1933, 1955). This conventional perspective has been repeatedly criticized for taking the material remains at face value. The number of buried people in a certain period does not need to have had any relation to the size of the population, but is dependent on different burial customs. Settlements and forts were not always abandoned in the middle of the sixth century and ruins of farms and villages could be the result of a new social order, moving settlements, and changing land use as well (Näsman and Lund 1988; Myhre 2002:170 ff.; Näsman 2012).

However, ideas about a crisis in the middle of the sixth century have recently reappeared, prompted by a sudden disappearance of the sun behind a dust veil in 536. This event has been debated in the last fifteen years (Baillie 1999; Axboe 1999, 2001, 2007), and has most recently been summarized and developed by Bo Gräslund (2008), who sees a major population crisis as a result of the dust veil. A meteor impact or an enormous volcanic eruption took place in 536, resulting in a thick cloud covering the sky for years. The cloud had a global effect on the climate, as is visible in ice cores from Greenland and the Antarctic as well as in dendrochronology from Europe, Siberia, and north and south America. The cloud is also mentioned by several classical authors. John of Ephesus wrote in 536 that ‘the sun became dark and its darkness lasted for one and a half years. Each day it shone for about four hours, and still this light was only a feeble shadow’ (Gräslund 2008:103). Cassiodorus wrote in the same year about the fearful and terrifying experience of the darkened sun in Italy, leading to crop failure, hardened fruit, and bitter grapes. In northern Europe, dendrochronology shows even more drastic effects. From 536 to 545 the growth of tree-rings nearly stopped, indicating several years without real summers. The effects of the cloud must have been more pronounced than in the Mediterranean (Gräslund 2008), although the local consequences may have varied. Communities growing cereals must have been more hit than communities that were dependent on fishery (Widgren 2012).

Recently, Daniel Löwenborg has argued that the event in 536 was a shock that profoundly changed the economy as well as the social and political organization in central Sweden (Löwenborg 2012). He refers to extensive desertion, followed by relocated settlements and burial grounds, and new burial customs, such as large mounds. Using analogies from the late medieval agrarian crisis, he envisages profound changes in property rights as a result of the dust veil in 536 and the decline in population that followed the cold summers in the 530s and 540s. Löwenborg has been criticized for exaggerating the consequences of the event in 536, and for not taking into account other contemporary aspects such as warfare (Näsman 2012).

The dust veil will never explain all changes in the sixth century. Apart from warfare, another series of important events was sparked by the collapse of Byzantine rule in many parts of the Mediterranean, when the Byzantine Empire was reduced to Constantinople, a few Greek ports, and some heavily fortified sites in Anatolia (Fig. 60). An aspect of the Byzantine collapse was that Avarian and Slavonic groups conquered large parts of the Balkans and Greece (Hendy 1985:69 ff.; Gregory 1994; Andrén 1997). In this process, Scandinavia lost its old connections with south-east Europe and the Byzantine Empire, as well as its sources of gold. No new gold coins, solidi, entered Scandinavia after the mid sixth century (Fagerlie 1967), which must have had huge consequences because gold had been used as a social and political medium by Scandinavian elite groups since the first century AD (Andersson 1995:9 ff.).

Figure 60. Ruin of Basilica A in Nikopolis, founded by Bishop Alkyson, who died in 516. This basilica is just one example of over 300 large churches that were ruined or abandoned in Greece during the ‘dark ages’, from the end of the sixth century to the late eighth century (see Zakynthinos 1966; Pallas 1977). These church ruins represent a clear ‘system collapse’, when the Byzantine Empire lost its political and religious control over most of its European regions to different Slavic groups. (Photo by the author.)

However, the dust veil as a global phenomenon needs more consideration, not least with respect to possible consequences and reactions. Löwenborg used a few analogies with the late medieval agrarian crisis, but these can be expanded to other illuminating parallels. For a long time, the Black Death in 1347–51 has been explained away as a main source of the late medieval agrarian crisis, since its non-human background made it historically ‘meaningless’ (Gissel et al. 1981). The same reactions can be indirectly found in the discussion concerning the dust veil (Wickham 2005:548 ff.; Näsman 2012). However, in recent years the devastating consequences of the Black Death have become more and more obvious (Harrison 2000; Myrdal 2003), and probably a similar reorientation will be visible regarding the dust veil.

It is practically impossible to estimate how many people died in Scandinavia during the Black Death, but the consequences of the population decline are quite visible (Myrdal 2003). According to dendrochronological dates, no new blockhouses were built in northern Sweden between 1350 and 1490, since the surviving population used and reused abandoned houses. The desertion is above all visible in marginal land, since whole settlements were abandoned in those regions. In central agrarian regions, a depopulation is much more difficult to trace, since the land of the deserted farms was used by the surviving farms. However, a recent study of western Östergötland shows considerable desertion and depopulation, although the arable land continued to be used (Karsvall 2011).

The late medieval desertion of agrarian settlements hit large parts of the minor landowning nobility, which more or less disappeared. In contrast, a small group of aristocratic families became large landholders, with political aspirations (Benedictow et al. 1971; Christensen 1976). From a material point of view, this change in property holding is visible in the abandonment of many small castles and fortified settlements during the fourteenth century (Olsen 2011). Due to the disappearance of the many smaller feudal families, the population decline in the long run led to larger political units in many parts of Europe.

The population decline affected the towns as well. Some small towns disappeared as urban settlements, several larger cities were partly deserted, no new towns were established from 1350 to about 1400, and from the early fifteenth century the ranking between the larger cities changed (Andrén 1985:100 ff.). From a religious point of view, the Black Death resulted in a new image of God. The earlier view of a triumphant Christ was replaced more generally by an image of the sacrificial Christ, at the same time as religious practice became more personal (Nilsén 1991:107 ff.; Pernler 1999). In European philosophy, a distinct empirical and critical turn is also visible from the mid fourteenth century, basically because the old scholastic scholars died in the plague, and were replaced by a whole new generation of young teachers (Nordin 1995:221). It is generally important to understand how the word crisis is used in the late medieval case. It was a crisis for the old social and political order. For most people who survived the plague, however, living conditions improved. New opportunities opened for a few landowning families, and the crisis led to a distinct ideological and religious creativity.

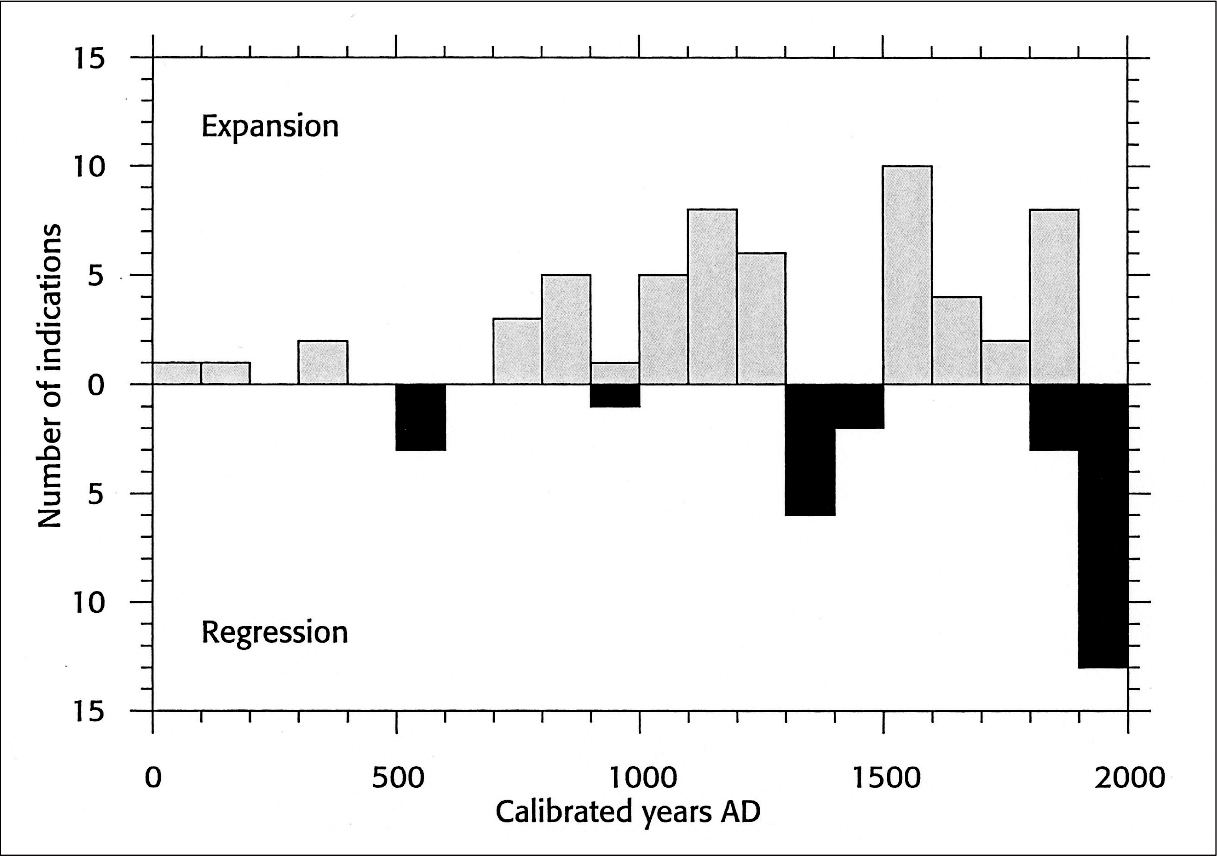

From a late medieval point of view, I see many similarities between the crisis in the fourteenth century and the profound changes in the sixth century. A non-‘man-made’ phenomenon led to a relatively pronounced population decrease. The desertion of settlements, following the population decease, is most visible in marginal regions, such as the interior of Småland (Fig. 61), where new comparative pollen analysis shows a distinct decrease in agrarian activities and signs of reforestation during the sixth century (Berglund et al. 2002; Häggström 2007; Lagerås 2007). The results clearly correspond to other pollen analyses in Sweden (Welinder 1975) as well as in other parts of northern Europe (Andersen and Berglund 1994). Besides, large-scale excavations show that the number of houses declined considerably in the sixth century, even in a central agrarian region such as Uppland (Göthberg 2007:440).

At the same time as the population declined, an old social and political order, based on ringforts, hillforts, and weapon deposits, was successively replaced by new or renewed elites that expressed their power through large halls and mounds (Skre 1998; Myhre 2002:170 ff.; Zachrisson 2011). In the long run, small political units, such as the gentes mentioned by Jordanes in the mid sixth century, were replaced by larger political coalitions of Danes, Svear, and Northmen mentioned from the ninth century onwards. There were no urban settlements in the sixth century, but the so-called central places were affected in the same way as the late medieval towns. Old centres such as Gudme and Högom disappeared (Jørgensen 2009:332 ff.; Ramqvist 1990:13 ff.), whereas other centres were newly established or became more important at the end of the sixth century, such as Lejre, Tissø, Järrestad, and Uppsala (Jørgensen 2009:337 ff.; cf. Ljungkvist 2005; Zachrisson 2011). The religious traditions changed as well, most notably with the disappearance of the sun-oriented traditions during the sixth century.

Figure 61. Indications of agricultural expansion (grey) and regression (black) in twenty high-quality pollen diagrams from upland areas in southern Sweden. Apart from decreasing agricultural activities in the last century and the late medieval agrarian crisis, the agrarian regression in the sixth century is clearly visible. (After Lagerås 2007:90.)

The profound changes in the sixth century must be related to the economy, social order, and political relations at that time. However, I have no doubts that the dust veil in 536 and the following depopulation were important aspects of these changes. This is especially true of the religious changes that occurred during that period.

The disappearance of the sun-oriented traditions in the sixth century

Different versions of solar myths and sun rituals existed in Scandinavia for two millennia, from 1500 BC to the sixth century AD, but the question is why the sun was venerated for such a long period and why it disappeared as an image after the sixth century, although some motifs ended up surviving in use until the thirteenth century. There are probably several answers to these two questions. Firstly, the metaphorical potential of the sun is quite obvious. The general idea of the sun moving across the sky in the day and through the underworld at night was a fundamental and natural element of many pre-modern worldviews, before the heliocentric cosmology was established in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Since the idea of the sun’s daily journey across the sky was shared by many pre-modern societies, different foreign aspects of this trip could easily be incorporated in local traditions. However, the general aspects of the journey of the sun cannot explain the special traits in the narrative tradition, such as the divine twins, or the disappearance of the solar narrative in the sixth century.

From a specific Scandinavian point of view, other factors must also be accounted for. A possible explanation is that the solar narrative was some kind of political discourse, following the changes to the social order. Kristiansen and Larsson have explored this aspect in the Bronze Age, with analogies from Greece (Kristiansen and Larsson 2005:262 ff.). Sparta, being the mythological home of the Greek dios kuroi, was ruled in the sixth and fifth centuries BC by two leaders in a literal parallel to the divine twins. Likewise, the Mycenaean palaces in the fourteenth and thirteenth centuries BC seem to have been ruled by two leaders, a ritual ruler called wanax and a military leader called lawagetas (Palaima 1995). Kristiansen and Larsson argue for a similar divided leadership in Bronze Age Scandinavia, based on and legitimized through the idea of twin gods supporting the sun on its eternal tour around the world (Kristiansen and Larsson 2005:271 ff.).

We must account for distinct differences in the social order of the Bronze Age and the Iron Age, but still a similar divided leadership seems to have existed in some places during parts of the Iron Age. Several Germanic origin myths mention twins or two brothers as being the original leaders of the tribes. As I have argued above, the marginal location and temporary use of the ringforts on Öland also indicate temporary military leaders ruling for short periods. And according to the Vita of St Saba, describing a Visigothic village in the 370s, the Visigothic tribes were actually ruled in the fourth century by a chieftain (reiks) and a temporary leader (kindins). However, the account states that in the long run the chieftains managed to take control of the Visigoths (Thompson 1966; Näsman 1988).

Such a political background to the solar myth may partly explain why the sun narratives were transformed and later disappeared. The divided leadership, which is clear in many Germanic myths of origin, disappeared during the Migration Period, when large parts of Europe and the late Roman world were transformed into early medieval kingdoms (Wickham 2005, 2009; Hedeager 2011). In Scandinavia, above all the broad star-like borders on the imitations of Roman medallions and bracteates indicate that rulers in the fourth and fifth centuries legitimized their power through the sun or the divine twins as supporters of the sun. These ideas were old, but may have been renewed with inspiration from the Roman imperial cult of Sol Invictus as well as a possible Hunnic notion of a solar king.

However, in 536 the sun literally disappeared in a global dust veil. It is easy enough to link the darkened sun with the vanishing of the solar symbol, but climate change in itself cannot directly explain why the sun symbol disappeared in Scandinavia. After all, the sun remained a central mythological figure in the Baltic and Sámi religions, although these regions must have been as much affected as Scandinavia by the darkened sun. Instead, the clouds in front of the sun must have hit specific aspects of Old Norse religion, above all its eschatological and political basis.

Gräslund has underlined the link between the darkened sun in 536 and the myth of the Fimbul Winter (fimbulvetr, ‘the mighty winter’) mentioned in Vafþrúðnismál 44 and Snorri’s Gylfaginning 50 (Gräslund 2008). The Fimbul Winter is described by Snorri as being a terribly cold period of three winters and two non-existent summers. It marked the start of Ragnarok, the end of the world, when all the gods died in battle with the powers of chaos, and the world eventually was destroyed in a gigantic fire. Elements of this myth may have been inspired by the experience of the darkened sun in the 530s, as Gräslund proposes. However, Anders Hultgård has argued from Iranian parallels that the idea of a Fimbul Winter was part of an older eschatology (Hultgård 2004). If this suggestion is correct, the disappearance of the sun in 536 must have been terrifying, a sign of the imminent destruction of the world.

The clouds in the sky may also have posed a profound political challenge. If my interpretation of the star-like border zones of the bracteates and imitations of medallions is correct, the ideological link between the rulers and the sun must have made the rulers in some sense responsible for the climatic disaster in the 530s. Consequently, the sun could no longer be used in political discourse, which meant that the important solar cycles with their sun symbols rapidly disappeared from images in the sixth century. Instead, the narratives and rituals about the divine and celestial world were thoroughly transformed during the sixth and seventh centuries.

A golden age

The Migration Period will remain an enigma. In one sense it is the start of the distinct animal art and the distant mythical past of the Icelandic narrative tradition. In another sense it marks an end of weapon deposits, most hillforts and ringforts, most stone-enclosed settlements, and the solar cycle. As I have argued elsewhere (Andrén 1998b), the fifth and sixth centuries stand out as a literal golden age, not only in Scandinavia but also in the Byzantine and Carolingian empires of the eighth and ninth centuries. However, the changes in the sixth century were so profound that these retrospective tendences or ‘renaissances’ from about 800 were placed in very different social realities. From a Scandinavian point of view, this change can be framed as people thinking of gold but dealing in silver (Zachrisson 1998:29 ff.).

For several reasons, I see the final longue durée of pagan Scandinavian culture as starting in 550 rather than 400. The social and ritual continuity from the late sixth century to the eleventh century is quite clear in central elite places such as Tissø, Lejre, and Järrestad, as well as in high-ranking burial grounds such as Vendel, Valsgärde, and Borre (Jørgensen 2009:337 ff.; Myhre 2002:170 ff.). In all these places, the same kind of buildings were built and the same kind of burial rituals were used for more than four centuries. In Sweden and Norway most large mounds were built from the late sixth century to the tenth century, although a few older mounds are known in western Norway and northern Sweden. In the politically important Mälaren region alone, about 270 large mounds were erected from the late sixth century to the tenth century. The largest mounds are dated to the late sixth and seventh centuries (Bratt 2008:29 ff.).

Several scholars have underlined that the social and ritual continuity seen from the late sixth century onwards indicate the start of a new type of aristocracy, one that based its power on control of land and legitimized its role as divine descendants (Skre 1998; Myhre 2002; Zachrisson 2011). It seems as the former division between more temporary ritual and military leaders disappeared, and was replaced by permanent ruling lineages that combined the ritual and military aspects of lordship (Schjødt forthcoming). This idea fits well with the royal lineages of the Ynglingar and the Skjoldungar, since they are connected with Gamla Uppsala and Lejre respectively, which were established as central places in the late sixth century (see Fig. 58). The older central places, such as Gudme and Uppåkra, are interestingly enough not known in the later Icelandic narrative tradition.

The new land-controlling elite must have claimed a divine origin through partly new mythological traditions. When the sun and the divine twins as central mythological motifs disappeared in the mid sixth century, many of the narratives of the other divine figures were transformed into versions that are recognizable in the much later Icelandic narrative tradition. The life of the new ruling elite was in many ways projected on to a divine world, where gods and goddesses lived in large halls and lived an aristocratic life in much the same way. This transformation explains why most of the motifs on the bracteates are difficult to interpret from an Icelandic point of view, and why most of the divine figures can, at least provisionally (cf. Price 2006), be identified in representations from only the Merovingian and Viking Age (550–1050).

Outlines of a new context

To conclude, I would maintain that Old Norse religion was not a coherent tradition, with a specific origin. Instead, different elements had different trajectories. I have argued earlier there were some very old elements in Scandinavian cosmology, which can be traced back to the fifteenth century BC. These include the sun-horse, the divine twins, and the night-ship. Possibly these old elements also include a version of the sky-god Tyr, since his name is cognate with other Indo-European sky-gods, such as Greek Zeus, Baltic Dievas, and Sanskrit Dyaus.

All these figures can be directly or indirectly traced in Scandinavian iconography running from the Early Bronze Age to the Middle Iron Age, including the early picture stones on Gotland. Interestingly enough, these are basically the same figures that Martin West, in a recent survey of Indo-European poetry and myth, labels as Indo-European (West 2007:166–237). Although he criticizes Georges Dumézil’s structural Indo-European mythology, he points out that these very general cosmological elements can actually be found cross-culturally in many Indo-European languages. It is therefore possible to interpret the new solar iconography in the Early Bronze Age as reflecting new Indo-European elements in Scandinavia, created in cultural interactions with continental Europe and indirectly with the eastern Mediterranean.

Although ideas of a world tree or a world pillar as well as an ordered world might be very old, it is not possible to trace these notions firmly in material culture until the Early Iron Age. It is also during this period that the fundamental figure ‘nine’ starts appearing in material culture for the first time. The central solar cycle survived the end of the Bronze Age, but new elements came to be included in the cosmology, or became more formalized.

In this context, I have not discussed a possible cultural encounter with the Celtic world, but the central European oppida culture from the third to the first centuries BC undoubtedly played an important role in Scandinavia (Rieckhoff and Biel 2001). The linguistic links between the thunder-god Thor and the Celtic god Taranis point to some shared history (Simek 1993:322), and aspects of the Scandinavian world tree might also be connected to the Celtic holy trees.

I have argued for the fundamental importance of cultural interaction with the Roman world, for instance, the expression of the idea of Midgard consisting of nine worlds and the distinct figure of an Old Norse world tree. In the last phase of the solar tradition, around 400–550, the incorporation of some kind of solar ruler is probably based on foreign models, such as the Roman Sol Invictus, the Byzantine emperor by God’s grace, and a possible Hunnic notion of a solar king.

Transformations in the wake of the dust veil in the 530s had very different effects on the cosmological elements. The sun lost all its central mythological role, although echoes of solar myths are still found in the later Icelandic written tradition. The divine twins, in the form of two horses or two warriors, were still found in images from the seventh and eighth centuries, but later disappeared or were transformed.

Tyr was an important god in the first centuries AD, which is clear from Tacitus mentioning him as one of the three main Germanic gods, from the Germanic translation of dies Martii, from the votive inscription of Mars Thingsus from the third century, and from early place-names (Simek 1993:337–8). However, after the sixth century, Tyr faded away to become a shadowy god, only mentioned in connection with the myth of how he saved the cosmic order by putting his hand in the mouth of the wolf Fenrir. In contrast, the importance of the god Thor remained unchallenged after the sixth century, and he actually seems to have been even more important at the end of paganism. This is above all visible in Thor’s hammer, which was introduced in the eighth century as a symbol of Thor and of paganism, offering a contrast to the Christian cross.

Some of the other Old Norse gods and goddesses may be more or less securely attested through the descriptions of Tacitus in AD 98, by the Germanic translations of the Roman days of the week and possibly also through some of the images on the bracteates. However, new attributes appearing from the sixth and seventh centuries clearly show how the mythological narratives have changed, and consequently how the character of the divinities has also changed (Fig. 62). Judging from the later written Icelandic tradition, it seems as if these new narratives of the gods in some cases actually included transformed solar elements from the earlier cosmology.

Among these transformed figures are Freyr, who according to Gylfaginning 23 ruled over ‘sunshine and rain’, and Ull, whose name probably derives from a word meaning ‘lustrous’ (de Vries 1957:159). Heimdall, who in Gylfaginning 27 was described as ‘the white As’, was said to have been born from the waves, thereby giving associations with the sun rising from the sea. In contrast, Baldr, who according to Gylfaginning 21 was ‘so bright that light shines from him’, is said in Gylfaginning 48 to have been cremated in a burning ship that sank into the sea, like the setting sun. Snorri also tells in Gylfaginning 53 that, after Ragnarok, Baldr would return from the dead and the underworld, coming back to the living world, as did the sun every morning. Odin’s ability to move between different worlds and transcend borders certainly fits the Dioscuri motif. Several late expressions of the Dioscuri motif from the sixth and seventh centuries have Odinic features, including elements such as spears and helmets with two birds (see Hauck 1984; Magnus 2001a).

As is clear from this very short overview, Old Norse religion and cosmology were not a coherent tradition with a single origin. Instead, the tradition was much more like a patchwork, with motifs and threads from different times and places. There were local and regional as well as social variations in this tradition, and there were more or less profound religious changes over time. One of these religious transformations occurred in the sixth century, but I will not label this transformation as a change to a new ‘Æsir religion’. Instead, it was a religious transformation where some old elements disappeared, some old aspects were remoulded into new contexts, and some new elements were introduced. It was this reworked patchwork of old and new threads that formed the mental background for the Christian authors who lived in Iceland centuries later.

Figure 62. Silver figure from a grave mound at Aska in Hagebyhöga in Östergötland. The figure has been interpreted as an image of the goddess Freyja with her necklace Brísingamen (Arrhenius 1969). Such an interpretation must remain provisional (see Price 2006), but the important point is that this figure, like other contemporary images, can be related to the mental world in the later Icelandic literary tradition in ways that older images cannot. (Photo by Gabriel Hildebrand, Statens Historiska Museum, Stockholm.)