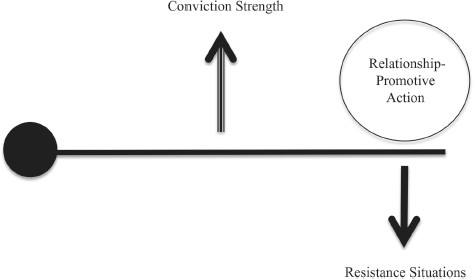

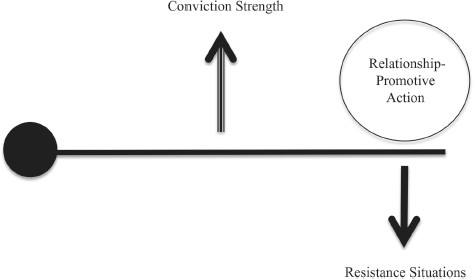

FIGURE 4.1 The Lever Model of Conviction

p.62

When Sylvia and Brian started dating, they never imagined taking a circuitous path to the altar. Those first semesters at college, it seemed like they were perfect for one another. They took the same classes, spent every day and night together, and enjoyed an overlapping circle of friends. They graduated convinced they would spend the rest of their lives together. Recently, the future has not seemed quite as clear. Brian got a job before Sylvia did and met a new circle of friends. Spending time with his engineering colleagues reminded Brian how much he loves high-adrenaline sports and adventure – pursuits he had largely put aside so he could share in Sylvia’s tamer interests. The prospect of an endless string of quiet movie nights alone with Sylvia does not feel quite as enticing as it once did. Watching Brian explore his new circle of friends, Sylvia is having some second thoughts too. On the odd occasion, she even catches herself daydreaming about one of her more refined and bookish male colleagues. Despite spending a short time apart as they settled into new jobs, Sylvia and Brian still want a future together. They just moved in together and they both feel like they have invested too much of themselves in their relationship to let it go, but they need to be sure that they really are right for one other and their future will be a rosy one.

The growing pains that Sylvia and Brian are experiencing naturally occur as interdependence increases. As encountered situations expand in breadth, partners discover new ways in which their needs and goals are less compatible than they thought (Kelley, 1979). Such expectancy violations can take many shapes and sizes. Partner qualities that first appeared charming may prove grating with time. The first time Brian was late for an appointment, it was easy for Sylvia to embrace it as part of his easy-going attitude. Now that they are both working and time is tight, his punctuality problems are a little harder to dismiss. At transition points in relationships, taking a new job, or having a baby, partners can also discover things they never knew, and do not particularly like, about one another. Sylvia seems a little too tame to Brian now that he sees her love for peace, quiet, and calm through the eyes of his new friends. Even familiar situations can violate expectations if one partner decides the status quo is no longer acceptable.

p.63

When reality disappoints, and partners violate one another’s expectations, doubt and ambivalence can start to creep in (Brickman, 1987). Rather than setting the stage for a relationship’s demise, doubt can actually sow the seeds for its resilience. This chapter takes us back to the functional imperative for purposeful and directed action introduced in Chapter 2. Decisive action requires certainty (Harmon-Jones, Amodio, & Harmon-Jones, 2009; Smith & Semin, 2004; Tritt, Inzlicht, & Harmon-Jones, 2012). Therefore, the experience of doubt is aversive and unpleasant because it interferes with directed and purposeful action. Doubt and ambivalence are even embodied as conflicted or stymied action. People instructed to physically sway side to side feel more doubtful, indecisive, and uncertain than people instructed to move up and down or stand still (Schneider et al., 2013). People exposed to two sides of an attitude issue also physically teeter side to side, conflicted both physically and mentally, unable to take a decisive step, either forward or backward (Schneider et al., 2013).

This chapter argues that seeing value and meaning in caring for the partner and relationship functions as an embodied goal because its ongoing pursuit neutralizes the doubts that could otherwise paralyze action. To care for Sylvia with a clear heart and mind, Brian needs to turn her distaste for his adventurous pursuits into something that he values in her. Such a capacity to defensively create value and meaning in action is crucial in relationships because perceiving value in the partner fosters steadfast intentions to be responsive and meet a partner’s needs when it is difficult to do so.

In the first section of this chapter, we introduce the desired end-state: To perceive unequivocal value in relationship-promotive action. “Relationship-promotive action” refers to behaviors that are personally costly, but nurture the partner and relationship, such as forgiveness, support, and sacrifice. We argue that people experience such actions as inherently valuable when they are convinced they are right; that is, when they are not ambivalent or uncertain (Brickman, 1987). We then describe how progress toward the goal of perceiving unequivocal value in relationship-promotive action is signaled through mental representations and bodily states associated with the experience of clear-minded conviction. We argue dissonance-related affective and bodily states capture incipient threats to conviction and signal when the basis for relationship-promotive action could become questionable (Harmon-Jones, Harmon-Jones, & Levy, 2015; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, & de Liver, 2009). We also argue that conscious thoughts of commitment capture the history of realized threats to commitment and signals when the basis for relationship-promotive action has already become questionable (Brickman, 1987).

p.64

In the second section of the chapter, we explain how people make progress towards the goal of perceiving unequivocal value and meaning in caring for the partner and relationship. That is, we focus on the means of goal pursuit. We examine how the goal to perceive value in relationship-promotive action biases attention, perception, and inference in situations that threaten conviction. We argue that the motivational machinations that restore value and meaning in action depend on (1) the decision context, that is, whether it is an initial versus ongoing choice and (2) overall progress in pursuit of value as represented by chronic commitment.

In describing goal pursuit, we first focus on the uncertainties provoked by initial romantic choice. As we will explore, deciding which partner to pursue selectively biases attention toward diagnostic cues to partner value that support decisive and confident choices. We then turn to the uncertainties that arise as people live with the choice they made. Because no partner is as perfect as he or she initially seemed, people inevitably encounter situations that cause them to question their choices (even if it is just for a moment). In such situations, evidence of a partner’s faults, the lure of a tempting alternative, the frustration of losing autonomy, or the necessity of making a sacrifice automatically activate biases in attention, perception, and memory that defuse doubt and restore certainty to relationship-promotive action. We will also see that people who are more committed are more likely to evidence the automatic biases that protect conviction.

In the final section, we explore the effects that perceiving (or failing to perceive) sufficient meaning and value in the partner have on ongoing relationships. We specifically focus on the role that possessing positive illusions about the partner plays in suppressing doubt and strengthening conviction and commitment. We conclude by acknowledging an unacknowledged reality. Although this chapter focuses on the motivational machinations that create and sustain a sense of value in action, such a sense of conviction is much more difficult to sustain for some people and in some relationship contexts than others (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). We return to the situational and motivational pressures that compete with value goal pursuits in the remaining chapters.

The Desired End-State: An Unconflicted Basis for Relationship-Promotive Action

Even decisions that seem incontrovertible – like parenting – still require ongoing rationalization. Eibach and Mock (2011) confronted parents with the exorbitant financial costs of raising children, but varied how much existential angst such costs could provoke. They let parents in the “uncertainty” condition ruminate about these costs. But they mitigated these costs for parents in the “certainty” condition by telling them that their children would take care of them in old age. Then they gave parents the opportunity to justify their parenting behavior by proselytizing for pronatalism (e.g., “Parents experience a lot more happiness and satisfaction in their lives compared to people who have never had children”). The findings spoke to the power of the need to construct value in action: Parents in the “uncertainty” condition were much more pronatal in their proselytizing than parents in the “certain” basis for action condition.

p.65

Ambivalence Is the Relationship Reality

Unlike parenting, the decision to commit to one particular partner over others has much less built-in justification. In fact, living with someone is bound to make the reasons not to commit especially salient, as Sylvia and Brian discovered once they moved in together (Kelley, 1979). Because greater interdependence reveals the good, the bad, and the ugly, Zayas and Shoda (2015) reasoned that significant-other representations should be inherently ambivalent. Thinking of a valued significant other should automatically and simultaneously activate positive and negative associations.

To test this hypothesis, they had participants generate four names: (1) the significant other they liked the most; (2) the significant other they liked the least; (3) the significant object they liked the most (e.g., sunset); and (4) the significant object they liked the least (e.g., spider). These names then served as primes in a sequential priming task. The experimental prime (e.g., Sylvia, sunset) or control prime (i.e., random-letter string) first flashed imperceptibly on the computer screen. A target word then appeared (e.g., chocolate, cockroach). This target word remained on the screen until participants decided whether this target word was “pleasant” or “unpleasant” (Zayas & Shoda, 2015).

Sequential priming tasks such as this one use basic principles of spreading activation to uncover how people really think and feel about particular attitude objects (Fazio, Sanbonmatsu, Powell, & Kardes, 1986). If priming Sylvia only activates positive associations, Brian should be faster to identify chocolate as “pleasant” and slower to identify cockroach as “unpleasant” when Sylvia is primed (as compared to a random-letter string). But, if priming Sylvia activates both positive and negative associations, Brian should be faster to identify chocolate as “pleasant” and cockroach as “unpleasant” when Sylvia is primed (as compared to a random-letter string).

Priming most-liked significant others automatically activated both positive and negative associations. Participants were faster to identify positive targets as pleasant and negative targets as unpleasant when thinking of the significant other they valued most. In contrast, priming the significant object participants liked the most automatically activated primarily positive associations and priming the significant others and objects participants liked the least generated primarily negative associations. Representations of beloved significant others are unique in this important respect: They are inherently conflicted. Significant others automatically bring positive and negative associations to mind.

p.66

But Ambivalent Realities Are Behaviorally Untenable

In most situations, people are not troubled by the internal contradictions in their beliefs because their attitudes do not have any immediate implications for action. During the work week, when Brian has no time to go on a sports adventure, the fact that he loves and hates Sylvia’s caution never really enters his mind. However, when people do need to act, the internal contradictions in ambivalent attitudes can become accessible (Newby-Clark, McGregor, & Zanna, 2002). Such conflicted attitudes, feelings, or beliefs point people in two opposite directions, making these conflicted or internally contradictory representations behaviorally untenable (Harmon-Jones et al., 2015).

Therein lies the problem people face in relationships (and elsewhere in life). People want and need to act with a clear-minded sense of purpose, but the conflicted nature of many attitudes, beliefs, and feelings thwarts that sense of purpose. Everything Brian likes about Sylvia’s caution motivates him to sacrifice his weekends freely, but everything he dislikes motivates him to go off with his friends. Because Brian cannot pursue both courses of action simultaneously, he needs to turn his behavioral indecision into the “right” decision (Elliot & Devine, 1994; Harmon-Jones et al., 2015).

The participants in the Zayas and Shoda (2015) studies did exactly this. Even though significant others automatically activated both positive and negative associations, people were not wracked by conscious doubts and uncertainties about those dearest to them. Instead, they reported uniformly positive feelings about their most liked significant others. The discrepancy between conflicted automatic associations and unconflicted conscious feelings makes perfect sense from our perspective. Conflicted feelings and beliefs stymie action (Schneider et al., 2013). To actually move forward, people need to turn such incipient conflicts into clear-minded resolve (van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., 2009).

Van Harreveld and Bullens and colleagues report fascinating illustrations of these basic dynamics in related programs of research on (1) ambivalent attitudes and (2) reversible versus irreversible decisions (Bullens, van Harreveld, Higgins, & Forster, 2014; Nordgren, van Harreveld, & van der Pligt, 2006; van Harreveld, Rutjens, Rotteveel, Nordgren, & van der Pligt, 2009; van Harreveld, Rutjens, Schneider, Nohlen, & Keskinis, 2014; van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., 2009). Their research warrants recapping here because it aptly illustrates how the basic need to perceive an unconflicted, unequivocal, and meaningful basis for action commandeers more specific goal pursuits in its service.

The ambivalence studies tested two related hypotheses. The first: Acting on the basis of an internally inconsistent attitude elicits angst and discomfort. Consistent with this hypothesis, people experience stress-related physiological arousal, conscious feelings of uncertainty, and generalized negative affect when they need to take a decided behavioral stand (either pro or con) on a conflicted attitude (van Harreveld, Rutjens, et al., 2009).

p.67

The second: Experiencing ambivalence motivates people to make actions “right.” What makes this hypothesis provocative is the flexibility with which people can make their decisions “right.” People can actually make their questionable actions seem sensible by perceiving greater order, consistency, and meaning in the world in general. For instance, people who feel ambivalent and uncertain because they just read about the pros and cons of enacting controversial abortion legislation restore perceptual order. They are more likely to perceive meaningful pictures in random dots than people who feel unconflicted (van Harreveld et al., 2014, Study 1). Similarly, people who feel anxious and uncertain because they just thought about something they feel personally conflicted about restore psychological order. They are more likely to grasp on to implausible conspiracy theories to explain the inexplicable than people thinking of a personal topic they feel unconflicted about (Study 2). Restoring physical order by straightening a messy lab room even inoculates people against the disorder in their personal lives. When people had to sit in a messy lab room, those who had just thought about a personal conflict restored order and consistency to their worlds by perceiving meaningful pictures in random dots. But this psychological meaning-restorative response disappeared when people first had the opportunity to straighten a messy lab room, and thus restore physical order to their worlds (van Harreveld et al., 2014, Study 3).

Research comparing the psychological effects of reversible versus irreversible decisions further suggests that constructing consistency, order, and value in choice actually fosters unconflicted behavior. In their experiments, Bullens and colleagues instructed participants to decide between two equally desirable options (Bullens et al., 2014; Bullens, van Harreveld, & Forster, 2011; Bullens, van Harreveld, Forster, & van der Pligt, 2013). They manipulated the pressure to make the decision orderly and meaningful by telling participants the decision was either irreversible (i.e., they could not take it back) or reversible (i.e., they could take it back).

When decisions are irreversible, people need to act on the basis of the choices they made. But, when decisions are reversible, people do not need to live with the choice they made; they can bail at any point in time. Because irreversible decisions need to be acted upon immediately, irreversible decisions should motivate people to make their decision the “right” one. That is, people making irreversible decisions should justify and come to see greater value in their choices than people making reversible decisions (Gilbert & Ebert, 2002). Such a clear-minded sense of purpose should free people to move forward, productively acting on the basis of the decision. Consistent with this logic, people who had just made an irreversible decision showed greater promotion or approach-oriented motivation than people who had just made a reversible choice (Bullens et al., 2014). However, people who had just made a reversible decision were left stuck in ambivalence; they exhausted themselves cognitively, continually revisiting their choice, which left them unable to move forward (Bullens et al., 2013).

p.68

Conviction: Marking Goal Pursuit

The reviewed research suggests that the motivation to perceive an unconflicted and unequivocal basis for action commandeers goal pursuits in its service. The necessity of acting in the face of uncertainty compels people to perceive the actions they ultimately take as meaningful, purposeful, and “right.” Such clarity of mind can then afford effective and vigorous behavior (van Harreveld, van der Pligt, et al., 2009). In relationships, the need to perceive an unconflicted and unequivocal basis for relationship-promotive action manifests itself in the pursuit of value and meaning in the partner. Perceiving Sylvia as valuable and meaningful – as the “right” partner for him – takes any internal contradiction out of Brian’s inherently ambivalent or conflicted actions. His resistance to his coworker’s flirtations, his weekend sacrifices of adventure time, and his efforts to bite his tongue when she criticizes him all make sense. These actions are meaningful and rational rather than purposeless and foolish because seeing incontrovertible value and meaning in Sylvia makes her worth it.

FIGURE 4.1 The Lever Model of Conviction

Brian’s strength of conviction marks his progress in the pursuit of value goals, and thus, his current state of clarity in mind and action. Figure 4.1 depicts our conceptual model of conviction. It resembles a third-class lever because conviction is the psychological and bodily force applied to drive caring, communal, and responsive behavior in the face of resistance. In this model, “conviction strength” refers to a state of mind internal to the person. Conviction boils down to Brian’s resolute belief that he is in the “right” relationship with the “right” partner. Unless shaken, conviction gives clear value and meaning to caring, communal, and responsive behavior because it elevates it to a higher calling (Brickman, 1987). “Resistance” refers to situations that test conviction by making the unexpected costs of interdependence salient. Such unwelcome surprises might involve temptations of the flesh, such as Sylvia’s attraction to a colleague, weaknesses of the spirit, such as Sylvia’s reluctance to share in Brian’s outdoor activities, and impulses of emotion, such as Brian’s desire to snap at Sylvia in retaliation.

p.69

The psychological lever depicted in Figure 4.1 functions straightforwardly: The greater the situational “resistance,” the greater the “force” of conviction that needs to be applied to drive and energize unconflicted relationship-promotive behavior. Stronger convictions stabilize motivations to behave responsively because conviction necessitates a belief structure that puts doubt in context. For instance, people who put doubts in context by mentally linking their partner’s faults to their greater, compensatory virtues are involved in more rewarding and more stable relationships (Murray & Holmes, 1999).

For conviction to leverage unconflicted relationship-promotive behavior, perceivers need to “know” when situations necessitate applying more force. In our conceptual model, the intangible strength of conviction has two tangible experiential markers: (1) the affective state of dissonance arousal and uncertainty and (2) the cognitive state of commitment. These markers signal progress in the pursuit of value goals and motivate people to apply more force and solidify conviction when it is in question by adding compensatory value and meaning to the partner and relationship itself.

The experience of dissonance serves as an immediate or impulsive bodily signal that the value and purpose of relationship-promotive behavior might be in question. Brian’s experience of affective uncertainty and bodily discomfort in a threatening situation – such as when he has to choose between spending a quiet weekend with Sylvia or going off with his adventurous friends – functions as a first line of defense; a proverbial warning shot that Sylvia might not be worth the sacrifice of staying. The experience of commitment serves as a less immediate, more reflective, and more persistently pressing signal of whether the value of engaging in relationship-promotive behavior is already in question. Brian coming to consciously question his commitment functions as a second line of defense – a last-call warning that Sylvia might not be worth the sacrifices he has made in the past or might make in the future.

The Affective Marker of Conviction: Dissonance

In the action-based model, dissonance motivates people to make conflicted actions unconflicted (Harmon-Jones et al., 2015; Harmon-Jones, Schmeichel, Inzlicht, & Harmon-Jones, 2011). In signaling disquiet, dissonance motivates people to make their actions meaningful, valuable, and “right.” Dissonance-worthy internal contradictions between thought and behavior happen routinely in relationships. Now that Brian and Sylvia are living together, he consistently challenges her ideals for the division of domestic labor. She wants a 50/50 division, but she is the only who notices the need to dust, vacuum, and do the dishes. She is starting to think that Brian is a lot more stubborn and selfish than she ever realized. The secret delight she takes in talking to her bookish and impeccably neat workmate has also caught her by surprise. She never expected to be attracted to anyone else. Now that Sylvia takes up more and more of his weekends, Brian spends more time wondering what it would be like to be single than he thinks he should. Sylvia’s new hours at work also precipitated his unhappy discovery that she is a lot more irritable than he ever thought. Even though they are generally happy and eager to move their relationship forward, reality is not always turning out exactly as they expected.

p.70

Left unchecked, such expectancy violations put the basis for being kind, loyal, and responsive to the partner into question. In our conceptualization of conviction, expectancy violations such as these elicit feelings of disquiet and discomfort to motivate constructing clear-minded and unconflicted intentions to engage in caring, communal, and committed behavior. When ongoing events violate expectations, experiencing dissonance provides a “first-line of defense” signal that motivates partners to construct new and better justifications for the kindnesses they bestow on one another.

Research using misattribution paradigms suggests that the affective discomfort underlying dissonance indeed motivates people to create a clear and unconflicted basis for action. Nordgren and colleagues (2006) activated ambivalent attitudes by exposing participants to the pros and cons of genetically modified foods. Then they gave some participants an alternate explanation for their discomfort (by telling them a pill they had just taken would make them feel tense). When participants did not expect to feel tense, the internal contradiction in their attitudes elicited angst and discomfort. Such aversive feelings in turn motivated them to clarify their thoughts by favoring one side of the issue. The experience of dissonance thus motivated them to create value in decisions to eat (or not eat) genetically modified foods (Nordgren et al., 2006).

In sum, the activation and alleviation of dissonance provide situation-sensitive markers of incipient threats to conviction that signal when Sylvia’s value to Brian might be in jeopardy. In expectancy-violating situations, the activation of dissonance signals insufficient progress toward value goals, motivating Brian to reclarify Sylvia’s value to him, solidifying the value of behaving with her best interest in mind (van Harreveld et al., 2014). In turn, the alleviation of dissonance then signals renewed progress toward the goal of perceiving value in action, remotivating decisive and steadfast relationship-promotive action (Harmon-Jones et al., 2009, 2011).

The Cognitive Marker of Conviction: Commitment

In the investment model, commitment motivates people to behave with the long-term interests of the relationship at heart (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Commitment captures intentions for the future that are based in the history of dependence, a structural property of the relationship (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Brian is more dependent on Sylvia when she satisfies more of his needs, when he has invested more time, energy, and resources in the relationship, and when he cannot imagine being happier living his life alone or with another partner (Rusbult, Martz, & Agnew, 1998). However, commitment also captures something more than just the history of dependence.

p.71

Interdependence theorists use the term “commitment” to capture psychological attachment to the partner and relationship that essentially goes beyond logic (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Brian’s commitment to Sylvia is not something that can simply be reduced to his reliance on her for need satisfaction, his concrete investment of time and energy, or his lack of other viable dating options. His commitment is intrinsic to his experience; it transcends practicalities and gives being with Sylvia meaning and purpose all on its own. In fact, commitment predicts greater relationship stability even controlling for its basis in dependence (Le & Agnew, 2003). Commitment supplies intrinsic meaning to action because it absolves the need to explain oneself (Brickman, 1987). Committed people do not need to think; they act. It is this clear-minded, resolute sense of purpose that gives rise to Brian’s desire to take care of Sylvia and makes the actions he takes to nurture his relationship intrinsically valuable and meaningful.

Commitment has one particular quality that makes it an especially adept marker of conviction. Like an elastic band, it is resilient to wear and tear, but it can still be stretched and manipulated. Because commitment is based in the history of the relationship, it affords a reasonably resilient chronic disposition to prioritize the relationship. As a chronic disposition, it functions to keep the relationship on an even keel, much as a rudder steadies a ship (Kelley, 1979; Rusbult et al., 1998; Rusbult & Buunk, 1993; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). However, events and situations can still test and stretch commitment. Even people who are highly committed experience doubts and question commitment given the right situations (Arriaga, 2001; Murray, Holmes, Griffin, & Derrick, 2015). Sylvia’s caution has become a source of confusion and ambivalence for Brian because he is so invested in his relationship. It has started to trouble him precisely because moving in together made him more dependent. Indeed, in Murray’s newlywed sample, people who were most committed at the point of marriage were the most likely to question their commitments over time (Murray et al., 2015).

This resilient elasticity means that commitment can signal the need to make further progress toward value goals in two respects. Through its resilience, commitment can function as a chronic motivational resource that incentivizes the pursuit of value. Much as the endorphins associated with exercise become addictive for the athletically minded, behaving caringly, communally, and responsively may become its own inherent reward for the committed-minded (Linardatos & Lydon, 2011). In Brian’s case, his usually strong commitment affords him the optimism needed to believe his actions are inherently meaningful, motivating him to think and behave in ways that sustain conviction. Through its elasticity, commitment wavering can signal especially testing “resistance” situations likely to require exerting a greater force of conviction in the future. In such situations, Brian’s unexpected and unsettling doubts about his commitment signal insufficient value goal progress and motivate him to reaffirm the importance of acting with Sylvia’s best interest in mind (van Harreveld et al., 2014).

p.72

Defending Goal Progress

As interdependence increases, people typically encounter more situations that test conviction and thwart value goal progress. These “resistance” situations differ from “risky” situations that test trust and thwart safety goal progress in one principal way. In “risky” situations, the perceiver is more dependent on the partner than the partner is on the perceiver (Chapter 3). In “resistance” situations, the balance of power is shifted and the partner is more dependent on the perceiver than the perceiver is on the partner. In interdependence terms, the perceiver has more “fate” control over the partner’s outcomes in “resistance” situations, whereas the partner has more “fate” control over the perceiver’s outcomes in “risky” situations. Fate control is the difference between Sylvia deciding whether to make a sacrifice for Brian (a “resistance” situation in which she has high fate control) and Sylvia asking Brian to make a sacrifice for her (a “risky” situation in which she has low fate control). In a “risky” situation, Brian gets to decide Sylvia’s fate, which gives him greater power to be selfish or selfless. In a “resistance” situation, Sylvia gets to decide Brian’s fate, which gives her greater power.

Typically, “resistance” situations have significant positive and negative features. This ambivalent feature mix tests Sylvia’s conviction in the value of caring for Brian and threatens her motivation to act in the relationship’s best interest. When Brian seeks Sylvia’s sympathetic ear, she knows she’ll have less time to spend on her own interests. When Sylvia cleans up after Brian without so much as a word of complaint, she also knows he might take advantage of her tolerance again. Thus, the strong positives and negatives that define “resistance” situations do not afford unequivocal reason for behaving caringly and communally. Instead, these situations cast people into a state of behavioral indecision that could stymie relationship-promotive action.

In the lever model of conviction depicted in Figure 4.1, “resistance” situations elicit dissonance and/or conscious doubts as a means of motivating clear-minded and unconflicted action. For Brian to behave responsively when it might be costly or unwise, he needs to perceive “value” in action. That is, he needs to make prioritizing Sylvia and his relationship the “right” choice. At those times when Brian needs to care for Sylvia when it is costly to him, experiencing dissonance or even doubting his commitment could provide the motivational incentive to make her more valuable and worth the sacrifice.

We now explore how uncertainty and the behavioral ambivalence inherent to resistance situations motivate people to turn conflicted interdependent situations into unconflicted ones. We review the motivated biases in attention, perception, and inference that allow people to perceive their partner as the “right” and “only” person for them. We start with motivated biases that turn the behavioral conflict created by a plethora of possible partners into the clear decision to pursue one “right” partner. We then examine the biases that keep the chosen partner the “right” partner when the going gets tougher.

p.73

Fitting Motivation to Context: Decision Deliberation

Uncertainty is inherent to choice. Even a trip to the grocery store presents a dizzying array of options. There’s ketchup in its original form, reduced-sugar, low-salt, jalapeño, organic, and ketchup blended with balsamic vinegar. Such a plethora of options invites indecision and behavioral conflict, but most people leave the grocery store believing they chose the right ketchup. In the social world, there are even more potential partners than ketchups to choose from, but most people leave the mating arena reasonably certain they chose the one partner that is “right” for them as well.

Brickman (1987) argued that the impossibility of making a truly unconflicted choice between romantic partners motivates people to believe they have done just that. Indeed, being hopeful, but uncertain, of another’s romantic interest motivates people to make the case for pursuing them ironclad. For instance, women inspecting Facebook profiles of potential dating partners value men who “might” like them more than men who “definitely” like them (Whitchurch, Wilson, & Gilbert, 2011). As we see next, making a definite, but uncertain, romantic choice automatically activates the perceptual, cognitive, and behavioral means for people to believe they are making the “right” choice. Uncertainty sensitizes people to cues that diagnose the upsides of an intended commitment and desensitizes people to cues that diagnose its downsides. The automatic detection of such value thus makes it easier to commit to pursue one particular partner over others. In fact, subliminally associating an available partner with desirable traits is sufficient to spur dedicated romantic interest (Koranyi, Gast, & Rothermund, 2012).

Maximizing the Upsides

The prospect of making an uncertain choice among potential partners sensitizes perceivers to partner qualities that make a given choice more valuable and easier to justify. Women primed with thoughts of romance are better able to discriminate heterosexual (a sexually desirable trait) from homosexual men (Rule, Rosen, Slepian, & Ambady, 2011). On speed dates, women are more drawn to men displaying the wide and broad facial signature of dominance (a genetically valuable trait) than men with narrower faces (Valentine, Norman, Penke, & Perrett, 2014). Men and women primed with the desire to seek romantic partners also selectively attend to the most physically attractive of their options (Maner, Gailliot, Rouby, & Miller, 2007). Physiological states that spur romantic choice also increase sensitivity to diagnostic cues to a partner’s value. Ovulating women are better able to discern heterosexual from homosexual men than non-ovulating women (Rule et al., 2011). Ovulating women are also more likely to flirt with dominant, “sexy cad” men who show the behavioral markers of genetic fitness than non-ovulating women (Cantu et al., 2014). Men are also more likely to pick up on cues that make women desirable, such as sexual arousal, when women are ovulating than when they are not (Miller & Maner, 2011b).

p.74

Minimizing the Negative

The prospect of making an uncertain choice among partners also desensitizes perceivers to qualities that could make a desired choice questionable and hard to justify. In deciding to pursue Sylvia, Brian had to sacrifice some of his personal autonomy to follow his own interests, including pursuing alternate partners. If he were to perseverate on such limitations, he might never commit. However, people contemplating romantic commitments automatically adopt more positive attitudes toward dependence (Koranyi & Meissner, 2015) and direct their attention away from attractive alternatives (Koranyi & Rothermund, 2012b).

Fitting Motivation to Context: Decision Implementation

Objective threats to unconflicted caring and communal action typically increase in frequency and severity as interdependence increases. When Brian first started dating Sylvia, sacrificing his weekends rarely gave him a moment’s hesitation because he was so captivated by her. But now that the passion has started to ebb, the costs of sacrificing his weekends are more salient. They have also discovered points of conflict they never entertained before they moved in together. Much to Sylvia’s surprise, the appearance of household cleanliness Brian maintained while they were dating was just pure pretense.

The situations partners encounter as they become more interdependent bring reasons not to be caring, communal, and responsive into sharper relief. This ambivalent reality makes forceful conviction in the partner’s value and meaning even more important for leveraging relationship-promotive behavior (Murray et al., 2015) and satisfying the belongingness imperative (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). It also makes forceful conviction more difficult to sustain because it is more frequently tested (Kelley, 1979). Given such taxing realities, the cognitive burden of value creation needs to be light (Bargh, Schwader, Hailey, Daley, & Boothby, 2012; Bargh & Williams, 2006; Dijksterhuis & Nordgren, 2006). Otherwise Brian wouldn’t have much in the way of self-regulatory resources available for anything other than being responsive to Sylvia (Finkel et al., 2006). Fortunately, the “resistance” situations people typically encounter automatically activate biases in attention, perception, and inference that accentuate the positives and minimize the negatives of responsive behavior. In so doing, such biases efficiently and expediently restore the value and purpose of behaving responsively without Brian giving it a second thought.1 We describe the automatic biases implicit in four commonly encountered “resistance” situations next.

p.75

Maximizing the Upsides

The first “resistance” situation involves sacrificing self-interest to meet a partner’s needs. Imagine Sylvia made special plans to go on a quiet spa weekend with Brian, but he wants to go mountain biking with his friends. For Brian to sacrifice, the valuing of making Sylvia happy needs to outweigh losing out on adrenaline and time with his friends. If Brian were to perseverate on both the positives and the negatives in this situation, he could get stuck in behavioral conflict. But the “right” course of action would be clear if “sacrifice” situations automatically elicit his tendency to enhance the value of meeting Sylvia’s needs. Sacrifice situations have just this effect. People more willingly sacrifice for their partner when they are behaving on automatic pilot because their self-control is taxed (Righetti, Finkenauer, & Finkel, 2013).

The second “resistance” situation arises when one partner inadvertently interferes with the other’s goals. Brian’s careless disregard for shoes, clothes, and food wrappers strewn about constantly frustrates Sylvia’s aspirations of domestic civility. If she perseverated on Brian’s apparent disregard for her interests in such “goal interference” situations, she might question prioritizing his needs. However, the “right” course of patience and caring would be immediately clear if goal interference automatically elicits compensatory tendencies to value the partner all the more.

We tested the hypothesis through a combination of experimental and daily diary studies (Murray, Holmes, et al., 2009). In one of the experiments, participants in the “goal-interference” condition completed a biased survey. This survey took participants through a list of exceedingly common ways one partner could interfere with the other partner’s personal goals (e.g., “I couldn’t watch something I wanted to watch on TV”; “I had my sleep disrupted”; “I had to spend time with friends of my partner I didn’t like”). Participants typically indicated that their partner interfered with their goals in many, if not most, of the ways listed. Participants in one of the control conditions completed a survey that simply asked them to indicate whether their goal pursuits had ever been disrupted (e.g., “I couldn’t watch something I wanted to watch on TV”; “I had my sleep disrupted”). We then measured automatic compensatory partner valuing by examining how quickly people associated their dating partner with positive traits in a categorization task. People automatically valued their partner more when they thought of their partner as the root of their personal frustrations. A partner interfering with one’s goals even motivates the victims of such obstruction to perceive greater meaning and value in treating their partner well! In a diary study, newlyweds who valued their partner more when their partner interfered with their goals on Monday actually behaved more responsively toward their partner on Tuesday (Murray, Holmes et al., 2009).

p.76

Minimizing the Downsides

The third resistance situation involves being hurt and let down by the other partner’s failure to be responsive. Brian encounters such “disappointment” situations whenever he wants Sylvia to do anything adventurous. In such situations, seeing compensatory value in being accommodative, forgiving, and responsive could keep Brian unconflicted and on the “right” behavioral course (Rusbult, Verette, Whitney, Slovik, & Lipkus, 1991). Such resistance situations do indeed elicit automatic inclinations to be accommodating and forgiving. For instance, imagining that a close other forgot to mail one’s application for a coveted job opportunity immediately brings thoughts of forgiving the errant partner to mind (Karremans & Aarts, 2007). People also blame themselves when their partner lets them down, concluding that they just did not communicate their needs clearly enough for their partner to understand them (Lemay & Melville, 2014). The impulsive inclination to compensate for a partner’s fallibility is so powerful that people even respond with positive facial affect to signs of a significant other’s faults in a stranger (Andersen, Reznik, & Manzella, 1996).

The fourth resistance situation takes us outside the relationship to the temptations posed by attractive alternatives. Knowing she has bookish colleagues at work who find her desirable has put Sylvia in something of a quandary. She doesn’t want to be attracted to anyone else, but sometimes she wonders if life would be easier if her partner had more similar interests to her own. If she got caught up with such thoughts, she could be locked into behavioral conflict about spending all of her time and energies on Brian. But, rather than being captivated by alternatives, people instead seem to quite automatically minimize what they could gain by pursuing alternate relationships.

The presence of attractive and available alternative partners automatically elicits compensatory tendencies to disregard and disparage (Maner, Gailliot, & Miller, 2009; Maner, Rouby, & Gonzaga, 2008). For instance, people primed with their love for their partner are quicker to deflect their attention away from attractive alternatives than control participants (Maner et al., 2009). People in committed dating and marital relationships also consciously disparage their alternatives, telling themselves they could never find anyone as desirable as the partner they possess (Johnson & Rusbult, 1989; Simpson, Gangestad, & Lerma, 1990). Just being involved in a relationship is enough to keep people from unconsciously mimicking the behaviors of attractive others (Karrenmans & Verwijmeren, 2008) and dull memory for the facial features of attractive others (Karrenmans, Dotsch, & Corneille, 2011). Women primed with commitment even take the unnecessary precaution of physically moving away from a virtual alternative partner (Lydon, Menzies-Toman, Burton, & Bell, 2008)! The automatic biases that turn alternative princes (and princesses) into frogs also keep people on an even behavioral keel. When tempting alternatives are salient, people are more likely to report intentions to behave caringly and communally toward their partner (Lydon et al., 2008).

p.77

Rebuilding Conviction: Giving Meaning to Action

The evidence that “resistance” situations motivate value creation supports one tenet of the psychological lever metaphor we introduced to explain how conviction motivates responsiveness (Figure 4.1). Threats to conviction, whether they come from the negatives inherent in sacrifice, goal interference, disappointment, or alternatives, automatically motivate people to find greater value in their partner. But the research we highlighted leaves a central question unaddressed: Does the compensatory creation of value actually alleviate threats to conviction and compel unconflicted action? Is it truly functional and adaptive in sustaining consistently responsive relationship interactions? Three lines of research suggest that it might have just this approach-motivating effect.

In the first line of research, Zheng, Fehr, Tai, Narayanan, and Gelfand (2015) hypothesized that the act of forgiveness makes actions feel more physically doable. They manipulated value creation by asking participants to think of a time when they had either forgiven or not forgiven someone who had transgressed against them. Then they surreptitiously measured how forceful people felt in the presence of a physically demanding world. Participants estimated the physical slant of a hill (Experiment 1) and jumped as high as they could (Experiment 2). In the terms of our lever model, the value that forgiveness imbues in the partner should supply greater force to behavior, even overcoming forces of physical resistance. In these studies, forgiveness did exactly that. It effectively unburdened participants, giving greater force to action. Those who recounted a time when they had forgiven a transgressor perceived the hill to be more climbable (i.e., less steep) and they could also jump measurably higher than participants who thought of a time they had not forgiven a transgressor. Consistent with this logic, hills also appear more physically conquerable (i.e., less steep) to people thinking of cherished significant others than the same hills appear to people thinking of less-valued companions (Schnall, Harber, Stefanucci, & Proffitt, 2008).

In the second line of research, Van Tongeren and colleagues (2015) hypothesized that the act of forgiving a romantic partner’s most serious transgressions gives greater meaning and purpose to action in general. These researchers invited committed couples to participate in a daily diary study. Participants initially completed a “meaning in life scale,” which tapped the extent to which they perceived their own life as being meaningful and purposeful. Every two weeks for the next five months participants then completed a standardized inventory, checking off “offenses” their partner had committed over the prior two weeks. They also rated their forgiveness of each offense. At the end of the study, participants then completed the “meaning in life” scale again.

p.78

In the terms of our level model, more frequent offenses (i.e., greater exposure to “disappointment” situations) threaten conviction and necessitate the compensatory creation of value in the partner. Forgiving the partner restores value, thereby restoring meaning to action, as captured by the sense that one’s life as a whole has purpose. The findings held true to this logic. When people compensated for conviction threats, life became more meaningful. When partners frequently offended, people who were more forgiving of these transgressions later reported a greater overall sense of meaning and purpose in their lives than people who were less forgiving. However, when partners rarely offended, forgiveness did not predict changes in the perception of meaning. It was only creating compensatory value that worked to restore meaning and purpose (Van Tongeren et al., 2015).

In the third line of research, we hypothesized that questioning commitment automatically motivates people to defend the value of commitment, hardening the resolve to behave caringly and communally over time (Murray et al., 2015). Murray’s newlywed study revealed exactly how this commitment-protective equilibrium unfolds (Murray et al., 2015). Both members of the couple reported feelings of commitment just after marriage and each year for the next three years. They also each completed 14 days of daily diaries at each of these time periods. These diaries allowed us to assess automatic intentions to protect commitment through IF-THEN contingencies in each partner’s thoughts and behavior. Specifically, these diaries allowed us to index Brian’s tendencies to (1) value Sylvia when she proved costly in interference situations; (2) accommodate to Sylvia when she behaved uncaringly in “disappointment” situations; and (3) make Sylvia depend on him when her willingness to sacrifice for him might be in question.

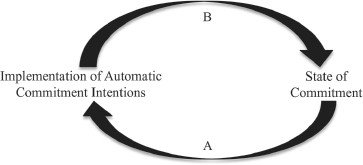

Looking at these marriages from year to year revealed strong evidence for a commitment-protective equilibrium. When people questioned their commitments, they defensively enacted automatic intentions to repair commitment. That is, people responded to years in their marriage when they felt less committed than usual by being more likely to justify costs, accommodate, and promote their partner’s dependence in subsequent interactions the next year (Path A in Figure 4.2). Being more likely to act on these automatic commitment intentions in turn hardened subsequent resolve to stay in the relationship. That is, being more likely to justify costs, accommodate, and promote their partner’s dependence in daily interactions strengthened feelings of commitment the next year (Path B in Figure 4.2). Thus, the compensatory defense of value fortifies conviction, as our lever model implies. When Brian experiences greater doubt, he thinks and behaves in ways that give greater value to caring and responsive behavior, which in turn, fortify his commitment to treat Sylvia caringly and communally in the face of future doubts.

p.79

FIGURE 4.2 The Equilibrium Model of Relationship Maintenance. (Adapted from Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., Griffin, D. W., & Derrick, J. L. (2015). The equilibrium model of relationship maintenance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108, 93–113. Copyright American Psychological Association; adapted with permission.)

Fitting Motivation to Context: Conviction Calibration

This brings us to our last set of arguments about value goal progress. Conviction is not only elastic and resilient; it is also self-perpetuating. For the most part, people who have made more overall progress toward value goals are more likely to think and behave in ways that further future goal progress (Linardatos & Lydon, 2011).

The duality in how commitment marks value goal progress is captured well by a daily diary study reported by Li and Fung (2015). In this study, people who were chronically more committed were more dissatisfied on days when their interactions with their partner were unexpectedly negative. Nonetheless, when daily interactions were unexpectedly negative, people who were more committed initially ended up even more satisfied months later. These effects should not be surprising by this point.

More committed people expect interactions with their partner to be caring and responsive (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). When negative interactions violate such expectations, more committed people likely experience unsettling feelings of dissonance and doubt. In the equilibrium model, it is experiencing acute doubts about commitment that signals the need to protect progress in the pursuit of value goals and motivates people to think and behave in ways that create compensatory value and bolster commitment (Murray et al., 2015). Therefore, being more threatened by daily negative interactions should motivate more committed people to apply still greater force to their convictions. By defensively creating greater value in the partner, more committed people could then restore purpose in caring, communal, and responsive behavior.

Consistent with this logic, chronic commitment helps keep relationships on an even keel. It supplies added incentive to sustain a sense of value and meaning in action by accentuating the positive and minimizing the negative in “resistance” situations. For instance, people who are more committed more readily forgive their partner’s betrayals (Finkel, Rusbult, Kamashiro, & Hannon, 2002), sacrifice on their partner’s behalf (Van Lange et al., 1997), and discount their partner’s imperfections (Arriaga, Slaughterbeck, Capezza, & Hmurovic, 2007). They also better resist the lure of attractive alternatives, derogating and ignoring even the most tempting of these temptations (Linardatos & Lydon, 2011; Lydon, Meana, Sepinwall, Richards, & Mayman, 1999). People who are more committed are also more practiced in suppressing aggressive impulses toward their partner when they are hurt and unjustifiably provoked by partner transgressions (Slotter et al., 2012).

p.80

Conviction Is Not Trust

These research examples highlight the last point we need to make about value goal progress. A person’s chronic level of conviction furthers value goal progress through a different calibration than chronic trust furthers safety goal progress. Possessing lower levels of chronic trust signals the need to make greater progress toward safety goals and intensifies this goal pursuit (Chapter 3). However, it is possessing higher levels of chronic conviction that signals the need to make greater progress toward value goals and intensifies this goal pursuit. How so?

Trust is largely a prevention-oriented regulatory sentiment; it functions to keep bad things from happening (Murray & Holmes, 2009, 2011). In risky situations, less-trusting people cannot afford for anything bad to happen because they are so readily hurt by rejection (Murray, Griffin, Rose, & Bellavia, 2003). Therefore, being less chronically trusting flags insufficient progress toward safety goals to motivate people to take the appropriate defensive action to keep bad things from happening (as we saw with Katy in Chapter 3).

Conviction is largely a promotion-oriented regulatory sentiment; it functions to make good things happen. People with greater chronic conviction thrive on the rewards their relationships offer and they are loath to miss out opportunities for good things to happen (Gable, 2005). Much like a runner addicted to an endorphin high, Brian just thrives on the feeling of contentment he gets when he takes care of Sylvia (Linardatos & Lydon, 2011; Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Because people with stronger chronic convictions are more promotion-oriented, they are likely to be more sensitive to the gains they might miss (e.g., Brian missing out on Sylvia’s happiness) than the losses they might incur (e.g., Brian not be able to go mountain biking) in resistance situations. By sensitizing people to reward, greater chronic conviction signals the likelihood and desirability of making even better things happen. Consequently, people with greater chronic conviction capitalize on available opportunities to revitalize their sense of conviction (Li & Fung, 2015). They are more likely to act on any automatically activated means to maximize the upsides and minimize the downsides of responsive action because they are essentially addicted to the conviction they already possess.

p.81

The Measure of Success: Value and Relationship Well-Being

Conviction is such a heady and addictive state because perceiving value in action generates belongingness rewards. Partner interactions are likely to be more caring, communal, and mutually responsive when partners know they are “right” for one another (Rusbult & Van Lange, 2003). Indeed, seeing a partner as intrinsically special and valuable motivates people to behave responsively (Gordon, Impett, Kogan, Oveis, & Keltner, 2012). Even subliminally reminding people of the value to be found in relationships (by priming sex) increases sacrifice and accommodation (Gillath, Mikulincer, Birnbaum, & Shaver, 2008). If the pursuit of value does indeed motivate responsiveness, goal attainment should differentiate well from poorly functioning relationships. Partners who come consistently closer to satisfying the goal to perceive incontrovertible value and meaning in the partner should be involved in more consistently responsive, satisfying, and more stable relationships than people who fall short. Is this the case?

This (finally) brings us to the most researched area of motivated cognition in relationships: The benefits of seeing special value in the partner that no one else really sees (de Jong & Reis, 2014; Eastwick & Neff, 2012; Fletcher & Kerr, 2010; Fletcher, Simpson, & Thomas, 2000; Martz et al., 1998; Miller, Niehuis, & Huston, 2006; Murray & Holmes, 1999; Murray, Holmes, Dolderman, & Griffin, 2000; Murray, Holmes, & Griffin,, 1996a, 1996b; Murray et al., 2011; Rusbult, Van Lange, Wilschut, Yovetich, & Verette, 2000). The literature on positive illusions is too extensive to review in entirety here, so we selectively sample highlights instead.

Positive Illusions in Relationships

What makes a partner feel like a “right” and valuable choice? In our research on positive illusions, we maintain that people create lasting value in partners by seeing them as ideal, or very nearly so (Murray et al., 1996a, 1996b). Brian’s image of his “ideal” partner epitomizes what he most desires and believes is right for him. Perceiving Sylvia as a close match to his ideals should make Brian happier and more responsive toward Sylvia if idealizing her cements his desired belief that she is exactly right for him.

Findings from Murray’s newlywed study illustrate the power that creating such inimitable value has to sustain satisfying relationships (Murray et al., 2011). In this study, we asked each husband and wife to describe himself or herself, his or her partner, and his or her hopes for an ideal partner on a variety of interpersonal qualities (e.g., warm, intelligent, critical and demanding, responsive, lazy). Participants made these ratings at six-month intervals over the first three years of their marriage. They also reported their overall satisfaction in the marriage at each of these seven times.

p.82

Constructing a measure of idealization that captured the creation of value in the partner took three steps. First, we correlated Brian’s ratings of Sylvia’s qualities across the 20 attributes with his ratings of his ideal partner’s qualities. This “projection” index captures the degree to which Brian believes that Sylvia has the same profile or relative ordering of qualities he hoped to find in an ideal partner. A strong positive correlation means that Brian ascribes the same profile of qualities to Sylvia and to his ideal partner (e.g., seeing both Sylvia and his ideal as more assertive than warm and more lazy than critical). Second, we correlated Brian’s ratings of his ideal partner’s qualities with Sylvia’s ratings of her own qualities. This “reality” index captures the degree to which Brian actually did find the qualities in Sylvia he had hoped to find (at least, according to Sylvia). Third, we used the “projection” and “reality” indices together to pinpoint whether people who created greater value in their partner would be better able to sustain satisfaction over the first three years of marriage. To do this, we predicted the path or trajectory of each person’s satisfaction (i.e., declining, stable, increasing) over time from the simultaneous effects of the “projection” and “reality” indices. In this analysis, the association between Brian’s ideals and his perception of Sylvia now captures Brian’s motivated creation of value (because we removed the kernel of truth in his perceptions).

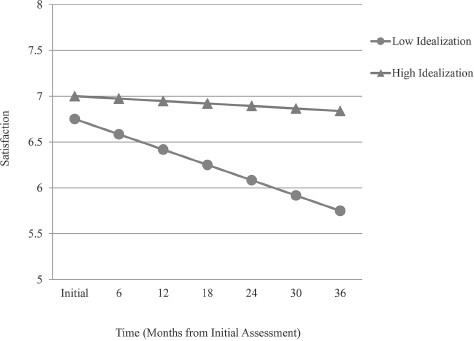

Figure 4.3 presents average declines in satisfaction for people who were more or less likely to idealize their partner at the time they married. Satisfaction declined precipitously for people who idealized their partner the least. However, perceiving greater value in the partner stabilized relationships. People who married optimistically believing that their (less-than-ideal) partner was a veritable mirror of their ideals were just as happy three years into marriage as they were when they married.

These findings provide a great analogue to our lever logic. The more ideal the partner is perceived to be, the more “right” the partner. Idealizing the partner more thus gives greater meaning to caring and communal behavior – tipping the psychological balance in “resistance” situations in its favor more often than not. If Brian’s resolve that Sylvia is truly right for him motivates him to be more responsive, it should prove to be contagious. Sylvia should be more satisfied when Brian sees her as a closer match to his ideals because valuing her should make it easier for him to be responsive. She should reap belongingness rewards from his idealization-fueled and clear-minded motivation to treat her well. Consistent with this logic, when people perceived their partner as a near-perfect match to their ideals at marriage, their partner also stayed blissfully satisfied. But, when people married without such a sense of resolve, their partner suffered as well.

p.83

FIGURE 4.3 Declines in Satisfaction as a Function of Initial Idealization. (Reproduced with permission from Murray, S. L., Griffin, D. W., Derrick, J., Harris, B., Aloni, M., & Leder, S. (2011). Tempting fate or inviting happiness? Unrealistic idealization prevents the decline of marital satisfaction. Psychological Science, 22, 619–626. Copyright Sage Publications.)

This newlywed study suggests that creating incontrovertible value and meaning in the partner is crucial for continued satisfaction. Value creation stabilizes relationships in our view because it vanquishes doubt and makes caring for the partner the “right” choice. Further findings buttress this idea. For instance, newlyweds coached to take the perspective of a third party who can see good intention in a partner’s conflict behavior are less distressed by their problems over time. They also report more stable relationship satisfaction over time than newlyweds who are not coached to take such a generous perspective (Finkel, Slotter, Luchies, Walton, & Gross, 2013). Creating greater value in the partner also protects against divorce, which provides perhaps the clearest evidence that value creation sustains purpose and meaning in relationship action. It actually keeps the relationship together. Newlyweds who marry partners they perceive to be spot-on matches to their ideals are less likely to divorce after 3.5 years of marriage than newlyweds who perceive poorer matches (Eastwick & Neff, 2012).

Conclusion

We opened this chapter with the uncertainties that Sylvia and Brian are experiencing now that they have moved in together. We then described how the pursuit of value vanquishes such doubts and restores meaning to action. But we glossed over one obvious fact: Not everyone is equally successful in vanquishing doubts. While some people easily find the conviction they seek, perceiving sufficient value and meaning in the partner proves elusive for others. For the unfortunate, the inability to quash doubts sets relationships on the path to discord. People who consciously feel conflicted – torn between positive and negative feelings about their partner – report greater dissatisfaction (Fincham & Linfield, 1997). Physical health suffers as well; people who report greater ambivalence about their partner’s value evidence greater coronary-artery calcification than people who put doubts to rest (Uchino, Smith, & Berg, 2014).

p.84

For better or worse, the motivated biases that serve value goals are not immune to the evidence. Some situations and partners are harder to find value in than others, as we will see in Chapter 7 (Murray et al., 1996a). The pursuit of value is not immune to other goal pursuits either. Safety and value are interconnected goal pursuits. People usually need to be safe before they let themselves truly believe they found the “right” partner (Murray, Holmes, & Collins, 2006). The imperial priority that safety has over value can make it difficult to sustain unconflicted value and meaning in relationship action. Low self-esteem people present a case in point. They evidence the same automatic biases to protect conviction as high self-esteem people. But low self-esteem people experience strong reservations about their partner’s value nonetheless, because they too often get entrenched in safety goal pursuits (Murray et al., 1996a, 2000; Murray, Holmes et al., 2009). The possibility of such goal competition brings us to the motivational tension between safety and value – the topic of Chapter 5.

Note

1 Automatic behavioral inclinations are flexible as well as efficient. By flexible, we mean that such behavioral inclinations can be corrected or overturned when people are both motivated and able to do so (Olson & Fazio, 2008). We return to this point in Chapter 5.