This chapter is all about keeping your toddler well and safe, with information on how to find good health care for your child, including how to choose a care provider, identifying and treating common childhood illnesses, learning about medical procedures, and more.

You’ll also find information about children’s accident prevention, how to childproof your home, and instructions on family fire safety, vehicle safety, and drowning prevention. There are practical hints on how to treat minor injuries, such as removing a splinter and tending to minor cuts, and how to deal with sprains, strains, and fractures.

A special section discusses autism and finding professional and intervention services for toddlers with autism or other childhood disabilities.

Special Note

This section has been written for educational purposes only. It does not cover ALL toddler illnesses—only the most common ones (and diseases that children are vaccinated against)—as well as toddler injuries. It is not intended to serve as a substitute for medical advice from a healthcare provider. Do not use this information to diagnose or treat any health problems, illnesses, or accidents your toddler has without first consulting your pediatrician or family doctor. Your toddler’s health-care provider is the best person to answer any questions or concerns you may have regarding your toddler’s health and safety.

CHOOSING A HEALTH-CARE PROVIDER

If you’re not happy with the healthcare provider you currently have, or you’re searching for a doctor during your child’s toddler years, this section will help you figure out where to go to ensure that your child gets the health care he needs.

Most communities offer a variety of resources you can tap for recommendations about healthcare providers. Ask your friends with children if they’re happy with the care they get from their medical professionals. Your own physician may have suggestions for pediatricians.

If you have health insurance, your insurer may require that you use only those physicians who are part of its network of providers. If you can’t afford health insurance, all states offer some form of medical services for children whose families have moderate or low incomes.

When choosing a health-care provider for your toddler and family, it’s important to think ahead about how that arrangement will work over the years to come, and not just what’s convenient right now.

Family physicians are trained to work with an entire family, parents and children alike, which can provide a welcome sense of familiarity and continuity, and they can be more convenient, too. They’re a good choice if everyone in your family is generally healthy. (Should serious problems arise, you will be referred to a specialist, depending on the situation.)

Pediatricians and pediatric nurse-practitioners have specialized training in caring just for babies and children. Pediatricians are medical doctors who diagnose, treat, examine, and prevent diseases and injuries in children. A pediatrician must hold a four-year undergraduate college degree, a four-year doctor of medicine (MD) or doctor of osteopathy (DO) degree, plus at least three years of residency training. A license and board certification from the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) are also required to practice as a pediatrician in the United States.

Nurse-practitioners (NPs) are registered nurses who have completed specific advanced nursing education, such as a master’s degree, and some specialize in pediatrics. They have training in the diagnosis and management of common as well as some complex medical conditions. Depending upon the state in which they are licensed, they can perform medical exams, order tests and therapy for patients, and write prescriptions. Unlike physician’s assistants, who can only practice under the license of a medical doctor, nurse-practitioners practice under their own license, and they may practice independently, or they can be affiliated with physicians’ practices.

Since no two health-care providers are the same, it makes sense to interview several providers before choosing the one that best suits your lifestyle and needs. When you meet a prospective provider, ask about nurse-practitioners, physician assistants, and other staff support, billing practices and charges, weekend and nighttime coverage, hospital affiliation, after-hours visits, home visits, and telephone consultations. Find out, too, how emergencies are handled, whether the doctor has privileges at any nearby hospitals, and how promptly you can expect a callback when there’s a problem.

When you go to meet with a prospective pediatrician or other provider, pay attention not only to your comfort level with him or her, but also the way the receptionist and the rest of the staff act toward you, your child, and other patients/ parents in the practice. (Once your child has been accepted as a patient, you’ll probably discover that you are spending as much time interacting with the staff as you do with the doctor.)

Of course, some providers may be very popular and have very busy practices. That translates into shorter visits and less time for talking with you and answering your questions. One solution is to try to get your child’s non-urgent health concerns, such as rashes, colds, cuts, and scrapes, answered by a nurse-practitioner or other professional on the staff.

To minimize long wait times in a waiting room after you’ve made an appointment, call ahead before you leave home to find out if the doctor is on schedule, and/or try to schedule appointments during the least busy times.

Since you’re going to be relying on your doctor’s support and advice for many years, pick one that not only relates well to you, but to your child, too. A child-friendly doctor will take some time to warm up to your child by smiling and talking to win his trust, rather than talking down to him. He’ll take special care not to upset your toddler if possible.

If You Can’t Afford Medical Care

Health departments in most cities offer well care and immunizations at low or no cost, and federal Medicaid programs administered through states provide medical care for low-income families who meet certain eligibility requirements.

• Working families who are ineligible for Medicaid could still qualify for their state’s Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) administered by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

• In some states, a family of four that earns up to about $36,200 a year may still be eligible for CHIP, but requirements vary by state. The program pays for doctor visits, immunizations, and hospitalizations.

• To apply for either Medicaid or CHIP, contact your local department of social services, often listed under the name of your county. To find out more about what programs your state offers, check out www.insurekidsnow.gov/state/index.html online.

MEDICAL EXAMS

Checkups for toddlers usually are at 12, 15, 18, 24, and 36 months. When your child reaches 18 months, most likely he will have received all of his immunizations until his “kindergarten shots,” which are usually administered between 4 years and 6 years of age.

Before going to your first appointment, use a small notebook to write down all the questions that have been nagging you. Take the notebook and a pen along to the appointment, so that you can log all the doctor’s recommendations.

Here’s how a good exam is likely to go: A nurse will take your child’s vital signs: temperature, heart rate (pulse), speed of breathing (respiration), weight, and height. (A child’s pulse is faster than a grownup’s and is usually around 110.)

Typically blood pressure won’t be measured until age 3, although doctors and health-care providers are becoming increasingly more concerned about the rising levels of chronic diseases affecting children, particularly obesity, so they are administering tests and ordering preventive care earlier than they used to.

Blood pressure is measured by inflating and deflating a small, child-size cuff around the upper arm while counting heartbeats with a stethoscope. Blood pressure (BP) measurements will show possible kidney, hormone, and circulation problems related to the heart. BP gradually increases throughout infancy and childhood, so your toddler’s blood pressure may seem lower than yours is as an adult.

A practitioner skilled in treating children will be careful about how he (or she) approaches your toddler. He will wash his own hands, both to make sure they’re clean and to warm them up. Then he will greet you and your child, and probably suggest that the exam take place with your toddler sitting on your lap or right beside you. A toy or doll may be used to make the procedure seem more playful. He will likely start his exam with the least-threatening body parts, your child’s hands, and end it with the ears and throat.

While taking a close look at your child, he will also be conversing with you to see if you have any questions or concerns. Take your time and don’t feel rushed about raising issues that are important to you, even if they could seem minor.

Even though your child’s physical exam may seem cursory and fast, in fact, your child’s health-care provider will be carefully evaluating a whole host of physical signs. Your toddler may stay dressed for part of the exam, but then might be asked to undress down to his diaper or underpants for the rest of the exam.

Your child’s general physical appearance will be noted, as well as his activity level, how he interacts in his surroundings, and whether or not he seems to be in distress (as many toddlers are when they’re in doctor’s offices).

His skull shape and circumference will be noted. His skin and scalp will be examined for birthmarks, moles, or other growths and for rashes, head lice, or ringworm. The shape and position of his eyes and any abnormal eye movements or an inability to focus will be noted.

The practitioner will want to know that the inside of your toddler’s nose is healthy and that his breathing passages are working well and aren’t inflamed or have unusual mucus or tenderness. He’ll be looking for inappropriate items in the nostrils, too.

Your care provider may ask if you suspect your toddler of having any hearing problems, will examine the shape and position of the ears, and may suggest a hearing test if your child isn’t acquiring words or speaking as expected. Peering into your child’s ear canal, he will be looking to see if the eardrum looks inflamed or is stiff from infection. And he’ll want to make sure that there isn’t something in the ear canals that shouldn’t be there.

Your child will be asked to stick out his tongue, and a flat, wooden stick (tongue depressor) may be used to inspect the tongue, teeth, gums, tonsils, and palate in the back for signs of problems. Your toddler may gag, but that’s on purpose so that the doctor can catch a quick glimpse deeper in his throat.

Your toddler’s chest and abdomen will be examined and listened to with a stethoscope for how his heart and breathing sound.

The practitioner will also be checking his belly to see that there are no lumps or hard places. He’ll want to check your toddler’s muscle tone and if your child’s arms and legs move okay, and that joints are not warm or swollen. He will check how responsive your child’s reflexes are by gently tapping certain places on his knees, ankles, and elbows using a small rubber hammer that will make these parts of limbs automatically jump.

While some practitioners prefer to check a child’s abdomen while he’s lying down, others have found that a toddler might cooperate if he is sitting in your lap. While your child is cooperative, the doctor will also check the belly and other places with you helping. He will be listening for bowel sounds or unusual gurgles and growls, since the belly makes five to thirty-four sounds per minute.

A swollen or enlarged belly could mean there is a blockage, infection, or mass that’s in the way.

He’ll also be checking for tender spots that make your toddler wince or yelp. He will also take a quick look at your toddler’s genitals by pushing the diaper to the side to ensure that everything is as expected.

IMMUNIZATIONS

Modern vaccines provide protection from major, and sometimes life-threatening, illnesses. If your toddler requires immunizations, they could be first-time vaccines or, more likely, continuations of immunizations (booster shots) that were begun in your child’s first year.

Some parents have serious concerns about the safety of vaccines, and they worry about the rumors they have heard about shots causing autism. Talk frankly with your child’s health-care provider about your immunization concerns and seek his or her reasoned, educated opinion about it. Also, make sure to ask about the reactions you can expect and the signs of serious side effects that could potentially result from a vaccination.

It’s helpful to also do your own research about vaccines from trusted medical sources, but remember that immunizing is a hotly debated topic among parents, and they may provide highly biased views that aren’t always well informed or based on research.

Some injections may cause mild side effects such as redness, swelling, and a slight fever, but serious side effects are extremely rare. Once you’ve got all of the information available on immunizations, you’re in a better position to make an informed decision.

Getting Through Shots

Nobody likes to get shots, but they’re a necessary part of preventive care. Here are a few ideas for how you can help your toddler through the process of getting injections.

• Trust. Have confidence that your child’s health-care provider and nurse know how to administer shots quickly and correctly. Let the provider handle him. (The shot is more likely to be given in the thigh because the fat there makes it less uncomfortable than in the arm.)

• Be calm and lighthearted. The way you relax and act will help him to feel less anxious. Trying to prepare a toddler beforehand won’t do much good.

Make a fun little noise to distract him so he’s looking at you instead of the injection shot, or place some colorful stickers on his opposite arm to peel off for a distraction.

• Bring adhesive bandages. Most health-care providers supply child-friendly bandages, such as those with superheroes or Elmo pictured on them, but you can also bring your own, just in case. Keep some extras at home in case he wants a fresh one later.

• Praise. Instead of commiserating about how “awful” the shot was, let him know how proud you are for how he acted through it. Offer a sticker or some other small reward, if desired.

Questions to Ask About Immunizations

• How serious and prevalent is the illness that this shot will help to prevent?

• How effective is this immunization?

• Will a booster be needed? How often?

• Should my child be well (fever-free and without other symptoms) to have it?

• What’s the best way to prepare my toddler for the injection?

• Will there be any side effects? What are they and how should they be treated? How long do they typically last? What are the signs of a more serious side effect?

• If I am pregnant, could my toddler infect me with the vaccination virus and endanger the unborn child?

Immunization Guide

FEVERS AND THEIR TREATMENT

Fevers are quite common in toddlers, so it’s important to have at least one type of thermometer in your first aid kit. Knowing what your toddler’s temperature is can help your health-care provider decide how serious your child’s fever is and how best to treat it.

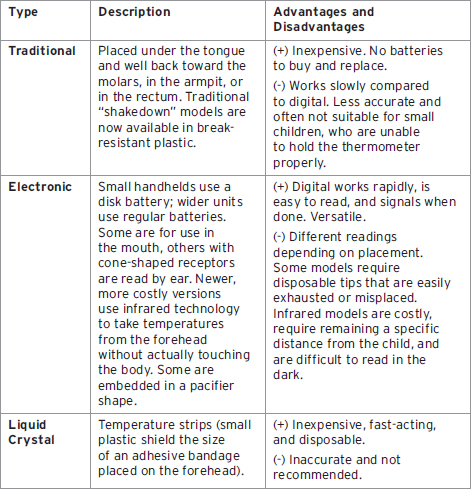

Types of Thermometers

Temperature can be measured by mouth, in the ear, under the arm, or rectally. It is measured in tenths. The average temperature for children and adults is 98.6°F. If you contact your health-care provider about your toddler’s temperature, you will need to tell him where it was measured—oral (mouth), aural (ear), axillary (armpit), or rectal (anus).

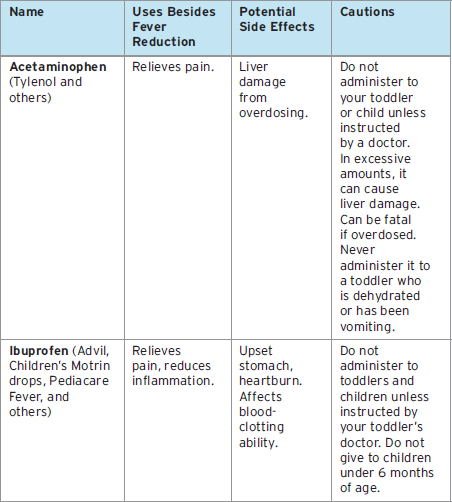

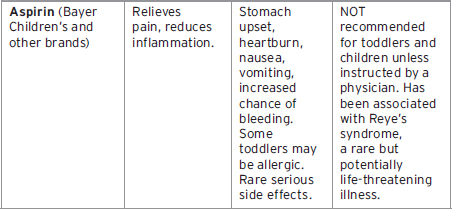

Over-the-Counter Fever-Reducing Medications

When a toddler has a fever, his health-care provider may recommend an over-the-counter medication to help bring his temperature down. Your child’s exact weight is important for determining how much medication to give him. Always consult your child’s health-care provider first before giving any medications and follow instructions very, very precisely.

If you have ever wondered what the difference is between medications such as Motrin, Tylenol, and aspirin, here’s a chart to help explain it.

Febrile Seizures

Sometimes a rapid rise in temperature to a high fever can trigger a seizure in a toddler. These episodes can be terrifying, but they’re usually harmless. They don’t lead to epilepsy, nor do they cause brain damage, nervous system problems, paralysis, mental retardation, or death.

• If your toddler has a fever-related seizure, he will start to look strange, then he will stiffen, twitch, and his eyes may roll back in his head. He may be momentarily unresponsive, and have uneven breathing, and his skin may appear darker than usual. He may shake on both sides of the body, or twitching may only appear in an arm or leg on only the right or the left side of the body.

• While it’s happening, quickly move your toddler away from anything he could hit if he is thrashing. Turn his head to the side so his mouth can drain, and don’t try to put anything into his mouth or try to feed him until he has recovered.

• Seizures typically happen in the first few hours after the onset of fever and last less than a minute. More rarely, they may go on for up to 15 minutes. After the seizure, your toddler may be sluggish for a couple of hours but will then return to normal. It’s rare that a toddler will have more than one febrile seizure in a 24-hour period. Children older than 1 year of age at the time of their first seizure have only a 30 percent chance of having a second febrile seizure.

To be on the safe side, contact your toddler’s pediatrician after the seizure has ended, particularly if your child seems to be seriously ill. In rare cases, a seizure accompanied by drowsiness, a stiff neck, vomiting, or other symptoms could signal a deadly attack of meningitis that needs rapid, life-saving intervention.

Cough Medicine Warning

In 2008, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a Public Health Advisory for parents and caregivers, recommending that over-the-counter (OTC) cough and cold medications not be used to treat infants and children younger than 2 years of age because of serious adverse events such as rapid heart rates, convulsions, decreased levels of consciousness, and death.

Administering Medications

Accurately measuring your toddler’s medicine doses is very important. There are a variety of devices and tactics for getting medicine into your toddler. Most toddler medications come in liquid form and have a dropper inside with tiny lines for measuring doses. (Use a bright light or flashlight, if needed, to ensure you get the right amount.)

There are also medicine spoons and tiny medicine cups with dose markings. The most accurate way to measure toddler medicine and make sure it doesn’t get spit out is to use a medicine syringe, which resembles a medical syringe, but without the needle. Draw the medicine up to the correct marking, and then squeeze out the medication at the back of your toddler’s tongue. Many pharmacies can add appealing flavorings to children’s liquid medicines. Over-the-counter flavor additives are also available, including some that are sugar-free.

Speak with your pharmacist about pill crushers that enable you to mix your child’s pill with his favorite foods, such as applesauce, pudding, or soft ice cream, to make taking pills more palatable. Also ask your pharmacist about which medicines shouldn’t be mixed with certain foods. Time-release medications cannot be crushed, as your child will not get the full effects of the medication.

A cold ice pop can help to numb your toddler’s taste buds, making bad-tasting medicine easier to take, and if swallowing a pill is required, a product called Swallow Aid is a gel that can be placed on a spoon to coat the pill, making it go down easier.

Sniffing a strong aroma, such as lemon zest or peppermint flavoring, while taking medication can help reduce your toddler’s awareness of bad-smelling liquids.

There are also suppository medications for fever or vomiting that you painlessly insert into your toddler’s anus.

A Note About Antibiotics

Antibiotics are used to fight bacterial infections, such as those that affect the ears, the throat, and the lungs, including tonsillitis (swollen inflamed glands in the throat) and bronchitis (infection in your toddler’s lungs).

More than sixty antibiotics are approved for use in pediatrics, and if your toddler has an infection you may well walk out of the hospital or doctor’s office with a prescription for something you’ve never heard of.

Antibiotics for toddlers are usually in liquid form, so make sure you have a good, easy-to-clean medicine dropper. Amoxicillin is the oldest and most prescribed for ear infections or strep throat, and is commonly used to treat acute middle-ear infections, but there are also other names and brands.

Whatever the prescription, it’s important to limit the use of antibiotics only to a diagnosed bacterial infection, because antibiotics can increase your toddler’s risk of developing asthma. Excessive antibiotic use can also contribute to the rise of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria. But, if your toddler does have a serious bacterial infection, antibiotics can be a (literal) lifesaver. It’s important that you follow your health-care provider’s instructions to a tee.

TIP

Never give your toddler any drug without your doctor’s prior approval and directions, including those available in drugstores or labeled “for children.”

TIP

The National Poison Center has poison experts (including for accidental medication overdose) on call 24 hours a day: 800-222-1212.

TIP

Antibiotics fight only bacteria, not viruses.

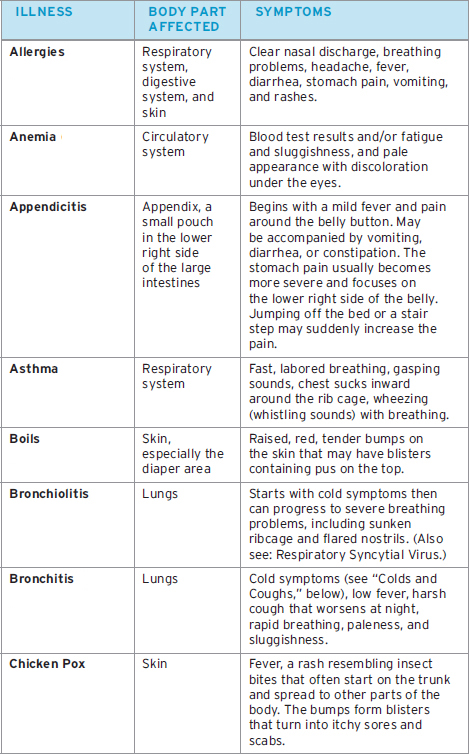

TYPICAL TODDLER ILLNESSES

Having your child come down with an illness can be distressing. Often toddlers are cranky and out of sorts before the symptoms of an illness actually show up. Your child may refuse to eat, or he may look different, too, perhaps more pale or red-faced, or with dark circles under his eyes, and he may be more whiney than usual.

As luck would have it, most parents don’t discover that their kids are really sick until the middle of the night, the day before a critical meeting or job interview, or on weekends when doctors (and babysitters) are hard to find.

There’s no need to panic or fear for the worst, though. Most children run a whole gamut of garden-variety illnesses before their immune systems become strong enough to help them ward off encroaching bacteria and viruses. Once their bodies get used to handling the bugs, most toddlers sail through weeks and even months without coming down with something.

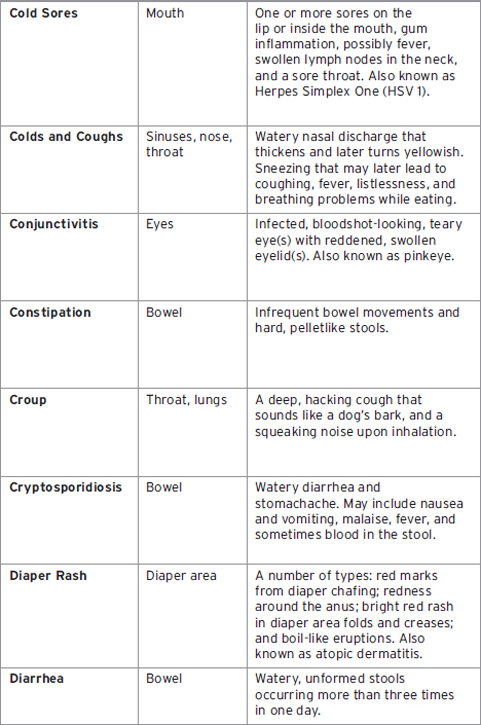

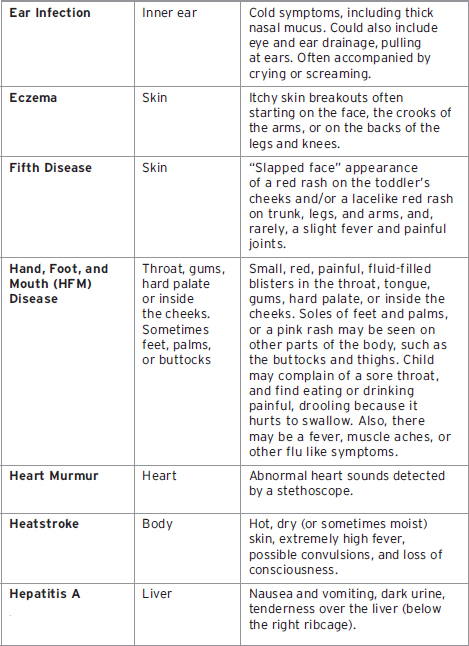

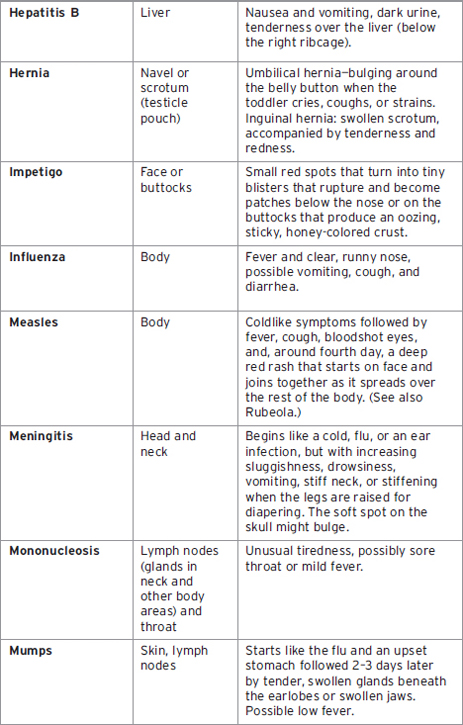

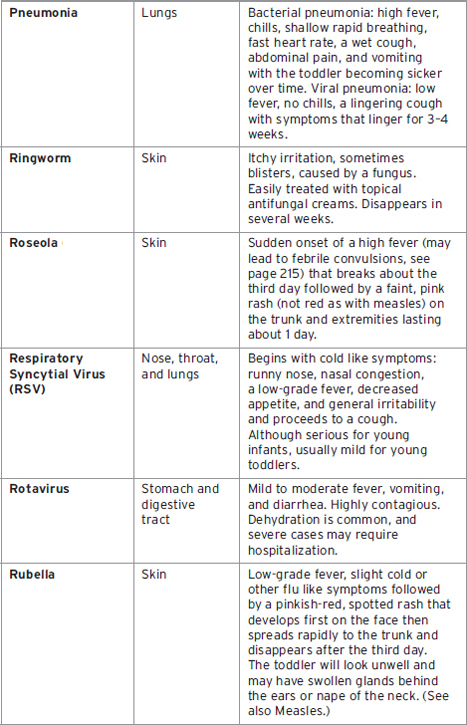

Below is a quick-reference guide to common toddler illnesses and physical problems you may encounter. The chart lists symptoms and gives you page numbers for where to find more detailed descriptions in this section or in other parts of the book.

TIP

Place a humidifier far enough away from the crib and other furniture to prevent moisture damage to wood surfaces.

TODDLER ILLNESSES A TO Z

Allergies

Sometimes the toddler’s body reacts to contact with substances and the immune system releases histamines and other chemicals to fight what the body believes to be an invader.

Symptoms of an allergic reaction may include any of these: a stuffy or runny nose (usually with clear discharge); sneezing or wheezing; red, itchy skin or rashes; and red, watery eyes. While some allergic reactions happen almost immediately, others may take days to happen, making it harder to find the cause.

Your toddler will be more likely to have allergic reactions if he is exposed to cigarette smoke, if you have a family history of allergies, including rashes, sneezing, asthma, or eczema, or if your toddler has been given antibiotics.

Sometimes toddlers will have allergic reactions to plant pollens and animal fur, foods, medications, or plastics found in disposable diapers.

Allergic rhinitis is the swelling and inflammation of the lining of the nose that lingers, rather than disappearing in a week to 10 days as a cold would. In addition to displaying some of the symptoms listed above, toddlers may have dark circles under their eyes, called “allergic shiners,” and a puffy-looking face.

Your doctor may recommend tests to help determine the cause of your toddler’s reaction, and a special elimination diet may be recommended to test for food reactivity. Medications may also be suggested.

A pediatric allergist/immunologist may be needed to help ferret out the cause of your toddler’s reactions. This is a medical doctor trained to treat babies and children who have allergies.

TIP

A severe allergic reaction may be indicated by anaphylactic shock (red, itchy whelps [hives], difficulty breathing). Call 911; every second counts.

TIP

Ana-Kit and EpiPen are brand names of epinephrine emergency kits designed to help reduce the effects of severe, life-threatening body reactions (anaphylactic shock).

Anemia

Iron is important in your child’s diet, particularly during the toddler years of rapid brain growth. The body uses iron to carry oxygen through the blood to the tissues. Iron deficiency can cause serious damage during these formative years.

Anemia is very common during toddlerhood due to toddlers’ dietary changes, such as switching from breastmilk or iron-fortified formula to regular cow’s milk or changing from iron-fortified baby cereals to regular cereals, appetite changes, or drinking juices that don’t supply iron.

Several studies have shown that being iron deficient can also increase a toddler’s vulnerability to lead poisoning, which can cause serious neurological damage.

If your toddler looks pale and seems tired a lot, anemia could be the cause. Other symptoms include a rapid heartbeat, irritability, loss of appetite, brittle nails, and a sore or swollen tongue.

Ask your toddler’s healthcare provider about iron supplementation. Typically, 10 milligrams of elemental iron from iron-fortified drops are suitable for children ages 1 to 6.

Appendicitis

Appendicitis is one of the most common causes for having an operation in childhood. It happens to about 4 out of every 1,000 children. It is an infection in a small, fingerlike pouch in the lower right-hand side of the large bowel.

The most common symptom is pain starting around the belly button that migrates to the lower right side of his abdomen, a tenderness that he doesn’t want touched, and sometimes nausea and vomiting. Your toddler may have trouble eating, or seem unusually sleepy, and in young children, diarrhea may be an early symptom. If your child has appendicitis and is horrified at having his belly touched, you can help your doctor examine him by offering to push on your child’s belly as directed or by putting your child over your shoulder so he’s facing away from the doctor and having the doctor slip his hand between you and your child to feel his abdomen.

Stomach pain is a familiar complaint of toddlers, and that makes it hard to tell if appendicitis or something else is the problem. Only about 3 percent of the time is appendicitis the source of stomach pain. For example, constipation is a much more common cause of severe stomach pain.

If your doctor suspects appendicitis and has your child hospitalized, the chances are 82 percent that he’s right. Perforation is when the swollen appendix balloons and becomes so large that it bursts, sending infectious material into the abdomen, which can be life threatening. The perforation rates for appendicitis are much higher for children than adults (about 30 to 65 percent of the time).

The cure for appendicitis is abdominal surgery, called an appendectomy, to remove it, hopefully before it can rupture, which could lead to lead to a life-threatening inflammation of the abdomen and other organs.

An open appendectomy involves making an incision over the appendix to remove it. A laparoscopic appendectomy uses a special tubular instrument inserted into a tiny incision that allows the surgeon both to view the appendix and to remove it.

Asthma

Asthma is a recurrent inflammatory condition of the bronchial airways. In layman’s terms, it’s difficulty breathing, but it’s also known as bronchial asthma, asthmatic bronchitis, reactive airway disease, bronchitis, and wheezy bronchitis. It affects nearly five million children in the United States.

It has become so widespread that it is now considered one of the most common childhood illnesses. Toddlers and children are more likely to develop asthma if they have allergies or a family history of allergies and asthma, were exposed to tobacco smoke in utero or after birth, were born with low birthweight, or have frequent respiratory infections.

A baby’s or toddler’s first asthma attack can be triggered by a number of things: a chest cold, cold air, exercise, some types of viral infections, changes in air quality (such as cigarette smoke in the air), and allergens such as dust mites, mold, pollen, or animal dander.

During an attack, the lining of your toddler’s lungs will become inflamed, and his airways will spasm and produce mucus. Symptoms will include: coughing, tightness in the chest, shortness of breath, and an unusual wheezing or whistling sound when your toddler exhales.

There are many different kinds of asthma. Your child’s health-care provider is the best person to help you decide if your child has asthma and what treatments should be used. Your child may be prescribed an inhaler (bronchodilator) with a breathing mask for use during attacks without the need for daily medications. If your child develops moderate, persistent asthma, then an inhaled anti-inflammatory steroid and a long-acting bronchodilator may be recommended.

A 2002 study published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine found that wheezing or coughing in babies and toddlers 2 years or younger was not necessarily a sign of developing lifelong asthma. But, after age 2, these symptoms could signal that the child might be vulnerable to asthma later. The largest majority of children who developed chronic asthma were found to have a history of asthma in the family. But, the study showed, even with a strong family history of asthma, more than 60 percent of children in asthma-vulnerable families did not go on to have lifelong asthma.

Reducing Asthma Attacks

Take these steps to help to reduce the severity of your toddler’s asthma attacks:

• Eliminate triggers. Keep your home as free as possible of dust and animal hair and dander, eliminate carpeting, and vacuum the floor and stuffed furniture frequently using a vacuum with powerful filters. Change linens frequently, and use allergen-proof casings on all bedding.

• Clean the air. Stop smoking and don’t allow others to smoke in your home. (Even if you smoke outdoors, your lungs will exhale smoke for days, and smoke will also cling to your hair, skin, and clothing when you are indoors.) Constantly run a fan-style air cleaner that contains high-density filtration layers in your child’s bedroom.

• Lower exposure. If pollen is a trigger, you may need to reduce outdoor activities in spring and fall, and be vigilant during sudden or extremely cold temperatures in winter.

Boils

Boils are raised, red bumps on the skin that may develop into infected white-topped blisters. They can erupt anywhere on the skin, but for toddlers who are still in diapers, they most often appear in the diaper area. It’s best to let a boil heal on its own.

Don’t try to pick or squeeze the bumps, as this could cause the infection to spread and could also lead to scarring. If the bump seems seriously infected, your toddler’s doctor may decide to open the boil, and may recommend antibiotic ointment to help with healing.

Bronchiolitis

Bronchiolitis is a viral infection of the tiny bronchioles deep in the lungs of babies and toddlers who are usually less than 2 years of age. In many cases RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus) is the culprit. The illness begins with typical cold symptoms, including nasal congestion, a fever of 100 degrees or higher, and mild coughing. It then can progress to become more severe and life-threatening when the lungs’ smallest air passages become inflamed. Signs of severe bronchiolitis include: sucking in of the skin around the ribs and the base of the throat when the child tries to breathe (retractions), flaring nostrils, and grunting. A baby or young child can become exhausted from the effort required to breathe, and in some cases breathing may completely stop. In those cases, emergency care is required. (See also Respiratory Syncytial Virus).

Bronchitis

When the large breathing airways become swollen, bronchitis results. There are two types: acute and chronic. Symptoms of acute bronchitis include fever; a painful cough; a sore throat; thick, yellow mucus; and shortness of breath.

Acute bronchitis is usually the result of a cold or flu, and while this kind of bronchitis is not dangerous in itself, it may lead to pneumonia. If your toddler shows any signs of breathing problems accompanied by a fever, you should call your health-care provider right away. In children, bronchitis is nearly always caused by a virus.

Your doctor will recommend a cough suppressant and/or other methods of treating the individual symptoms. The best ways to prevent bronchitis are to keep your child away from people who are ill, and away from pollution and secondhand smoke.

Chronic bronchitis is bronchitis that lasts for three months or longer. Pollutants, such as secondhand smoke or dust, can make it worse.

Chicken Pox

Chicken pox is a highly contagious childhood disease caused by the varicella zoster virus (VZV), a member of the herpes family. It can be very serious for young toddlers. If you are an adult and haven’t had chicken pox, you may catch it, too. Your toddler may be contagious 1 to 2 days before symptoms show.

Chicken pox is spread by other children, so keep your toddler away from children who have been exposed to chicken pox at school or from siblings. The varicella vaccine is available, and is recommended between 12 to 18 months of age. (And it is also recommended for you if you’re not pregnant and for your toddler’s siblings if any of you have not had the disease.)

The symptoms of chicken pox are sluggishness, frequent crying, and loss of appetite. Several days after exposure, a rash of flat, red, splotchy dots will erupt. It usually starts on the chest or stomach and back, then spreads to the face and scalp a day or so later. The red dots of the rash then join together to form clusters of tiny pimples, which then progress to small, delicate, clear blisters with new rash areas developing each day. The blisters form into extremely itchy scabs. Recovery can take as long as two weeks.

Oatmeal baths can be very soothing to dry, itchy skin. Tie a handful of raw oatmeal in a washcloth and swish it around in your child’s bathwater. Your toddler’s health-care provider may prescribe creams to put on the itchy spots, or over-the-counter lotions, such as calamine lotion, to help relieve the intense itching.

Cold Sores

Cold sores, also known as fever blisters, are small, fluid-filled blisters that crop up on or near the lips, and are very common during childhood. They can appear individually or in clusters. Despite their name, they have nothing to do with colds, but are caused by the herpes simplex virus type 1 (not herpes simplex virus type 2 that causes genital herpes, though either can cause sores in the facial or genital area).

Your toddler can catch the virus by sharing a cup, utensil, or slobbery toy with another person who has the infection or carried in his saliva through mouth-to-mouth kissing. During the first bout, called primary herpes, there may be mouth soreness, gum inflammation, possibly fever, swollen lymph nodes in the neck, and a sore throat, but symptoms could be very mild.

Recovery is in about 7 to 10 days, but the virus will stay in his body for life. For some children, the virus lies dormant; for others, it will periodically show up again. These flare-ups are called secondary herpes and can erupt from stress, fever, and sun exposure. Secondary flare-ups may be milder without swelling of his gums or lymph nodes or a fever or sore throat, but he will have the telltale blistering on or near his lips.

If your toddler develops a sore on his eyelid or the surface of his eye, call your health-care provider right away. Your child may need antiviral drugs to keep the infection from scarring his cornea. (In rare cases, ocular herpes can weaken vision and even cause blindness.)

Most treatments reduce the pain of the sore, but the virus has to run its course.

Colds and Coughs

It’s likely that your toddler will have more colds and other upper respiratory infections than any other illnesses throughout his childhood. On average, children catch nine colds during their first 2 years. Your toddler will be more vulnerable to these infections with more public contact, because viruses and bacteria are spread by contact and his body hasn’t yet learned how to fight them.

If your toddler has a cold, it will usually begin with clear fluid running from the nose, sneezing, and possibly a low fever. Though exposing your toddler to cold air doesn’t cause a cold, exposure to cold weather changes the way our bodies fight off viruses. The protective mucus and cilia in the respiratory tract do not function as efficiently, so if you get exposed to a virus in those conditions, you’re more likely to catch it.

If your toddler has a difficult time blowing his nose, treat his nasal congestion by using a ball-shaped, rubber suction bulb. Squeeze the bulb part of the syringe first, carefully place the tip into one nostril, and then gently release the bulb to create suction. Only a slight suction is needed. If secretions are particularly thick, your pediatrician may recommend mild saline nose drops. Using a dropper that has been cleaned with soap and water and rinsed well with plain water, place two drops in each nostril, and then immediately suction with the bulb. However, don’t suction too often as this can cause irritation. You might also try placing saline in the nose several times during the day.

When your child has a cold or an upper respiratory infection, place a cool-mist humidifier in his room to keep the air moist and make him more comfortable, being sure to clean and dry the humidifier thoroughly each day to prevent bacterial or mold contamination. (Hot-water vaporizers are not recommended because they can cause serious scalds or burns at their spouts.)

TIP

Nose drops that contain medication may be harmful to toddlers.

Conjunctivitis

Sometimes toddlers’ eyes get swollen or crusty, either because one or both tear ducts are plugged, or due to an infection, such as conjunctivitis (pinkeye). One or both eyes will appear red and swollen, crusty, or sticky with mucus. The infection can be caused by bacteria, a virus, or plugged tear ducts.

The home remedy is to dip a clean, soft washcloth or cotton ball in mildly warm water, squeeze out the excess moisture, and then gently massage the affected area every 2 to 4 hours. If symptoms persist after a day of lukewarm compresses, call your toddler’s health-care provider. Special eye drops or an ointment are likely to be prescribed. Most cases clear up in 3 to 5 days.

The viral and bacterial forms of pinkeye are highly contagious and can be spread very easily from one person to another, usually through hand-to-eye contact. Make sure everyone in the family keeps their hands clean when there’s an outbreak, and don’t allow anyone to share washcloths or towels.

Constipation

(See Chapter 9.)

Croup

Croup is not a single problem, but a symptom that occurs when a child’s upper airway swells and becomes narrowed by an illness or an allergic reaction. It causes a cough that sounds like a dog’s bark, and a squeaking noise when the child inhales. Croup is most common in babies and children between 3 months and 5 years.

Croup is usually not serious and can be helped with a cool-mist humidifier or by holding your toddler in the bathroom while a hot shower fills the room with steam. However, if your child shows signs of having difficulty breathing and/ or swallowing or is breathing rapidly, or the skin between his ribs pulls in with each breath, and/or he has a fever, call your pediatrician immediately.

In some toddlers and children, croup is a recurring problem, and those who are vulnerable to it may have three to four bouts of croup per flu season. Usually, croup doesn’t present a serious problem, but you should always seek your doctor’s advice. In most cases, children outgrow croup when their air passages mature and increase in size.

Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidiosis, called crypto for short, is an infectious diarrheal disease caused by the Cryptosporidium parasite. It’s common among children in child-care settings, but it can also be transmitted at swimming pools, especially kiddie pools.

Cryptosporidiosis is spread through fecal-oral transmission by feces of an infected person or an object that has been contaminated with the infected person’s feces. Infection can also occur if contaminated food or water is ingested. Outbreaks in child-care settings are most common in August and September.

Symptoms can take a week to develop and usually include watery diarrhea and stomachache, but can also include nausea and vomiting, general ill feeling, and fever, and sometimes there may be blood in the stool. The most severe part lasts from 4 to 7 days, but symptoms may come and go for up to 30 days.

The spread of cryptosporidiosis is highest among children who are not toilet-trained, and higher among toddlers than infants, because of their increased movement and interaction with other children. Child-care providers can get it from diaper changing.

The parasite is hard to detect, as few laboratories run tests for it, and there is no effective treatment for it. It simply runs its course.

Diaper Rash

Diaper rash is a red, sore patch of skin on your child’s bottom, genital area, or between the creases inside his thighs. It’s common for diaper users between 5 and 15 months of age. There are a variety of causes, but usually the red patches last for only a few days and then disappear.

Skin infections break out in the diaper area when moisture has broken down the skin’s naturally protective, oily barrier. Sometimes the breakdown is worsened by harsh chemicals produced when urine and feces mix together in the diaper and stay there for a while. That’s why it’s important to change your toddler’s diaper frequently and to keep the area rinsed off with clear water after a bowel movement.

Frequent airing out of the diaper area, preferably with some sunlight, can also help to improve the rash by letting the skin dry out. Baby powder and cornstarch don’t help diaper rash; in fact, they can make it worse, as can alcohol-based wipes. A thick layer of a zinc-based diaper cream can help to protect the skin long enough so that the rash can heal.

A cherry-red, oozing diaper rash may signal a yeast infection that may need special treatment. Your toddler’s health-care provider may recommend an anti-fungal cream, ointment, or a mild topical steroid. But don’t apply any over-the-counter products yourself unless they’ve gotten your health-care provider’s approval.

Contact your health-care provider if the rash doesn’t go away, or if it worsens, such as spreading to other body parts, there’s a fever involved, or it turns into pimples, blisters, ulcers, acne-like bumps or pus-filled sores.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea is loose, watery stools occurring more than three times per day. It is not the occasional loose stool or the frequent passing of barely formed stools. There are many possible causes of diarrhea in toddlers, such as bacterial infections, viruses, and parasites, and sometimes it can be caused by medical conditions, or allergic reactions to foods or milk products. One of the most common causes of toddler diarrhea is a stomach flu (viral gastroenteritis). Although many different viruses can cause stomach flu in toddlers, the most common one is called rotavirus.

Toddlers with diarrhea are a special concern because of their small body size, which puts them at greater risk for dehydration, particularly if the diarrhea is accompanied by vomiting. Your health-care provider will want to treat against dehydration by replacing lost fluid and electrolytes (sodium and potassium).

Giving special fluids by mouth (oral rehydration therapy) may be recommended using rehydration drinks such as Pedialyte, which can be found in bottles or as a powder to be added to water in most pharmacies and supermarkets and purchased without a prescription. (Note: Rehydration fluids have a brief shelf life. Once a bottle has been opened or a mix prepared, it must be used or thrown out within 24 hours. Bacteria rapidly grow in the solution, and a toddler could easily drink three or four bottles of the fluid during an illness.)

Do not try to treat diarrhea without first consulting with your toddler’s health-care provider. For home treatment, allow your toddler’s system to settle for a few hours after a diarrhea attack before encouraging him to eat again. If vomiting is involved, offer him small sips of water, or clear liquids, such as chicken or beef broth, or let him suck on ice chips. After several hours, gradually reintroduce food, starting with bland, easy-to-digest foods, such as applesauce, strained bananas, strained carrots, rice, or mashed potatoes.

Intestines that have been damaged by severe diarrhea may have trouble digesting whole cow’s milk, and your toddler’s health-care provider can suggest alternative liquids.

Diarrhea can cause your toddler’s diaper area to become red and sore. Use a thick layer of zinc-based diaper cream, to provide a shield for the skin. Change diapers frequently, rinsing his bottom with water and air-drying it, and cut down on the use of baby wipes, which can be irritating to toddlers’ irritated skin.

Ear Infection

Next to colds, middle-ear infection (otitis media) is the most common cause for trips to the pediatrician. As many as three out of four children have some form of ear infections by age 3.

There are two different kinds of infections: otitis media with effusion (OME), which means there is fluid in the middle ear, and acute otitis media (AOM), which refers to fluid in the middle ear that also comes with pain, redness, and a bulging eardrum.

Children with OME will seem completely fine, and you won’t know anything is wrong unless your pediatrician discovers the infection during a well-toddler visit. But toddlers with AOM will be fussy, especially at night, and may have a fever and other coldlike symptoms.

After a case of AOM, your toddler will probably have a case of OME for several weeks afterward. Typically, an acute infection will set in a few days after a cold has started. You can’t see that the toddler has the infection, but your health-care provider will be able to detect it by looking for swelling in your toddler’s ear with an otoscope and by blowing air on the eardrum to see if it’s swollen (the toddler will hate this, so be prepared for screaming).

If your toddler has an ear infection, a painkiller such as acetaminophen may be recommended along with a course of antibiotics that will usually come in liquid form. (If your toddler rejects the liquid, try mixing it in applesauce or yogurt.) In the meantime, your toddler may be more comfortable upright than lying down. Applying a warm, moist towel to your toddler’s cheek near the ears could help soothe the pain.

Usually ear infections get better after several days of treatment. If ear infections are recurrent (more than three episodes in 6 months), and your pediatrician believes the infections interfere with your toddler’s hearing and language development, minor surgery may be recommended that involves placing tiny tubes in the ear for draining fluid.

Eczema

Eczema (or atopic dermatitis) produces thickened, red, dry, flaky skin patches that itch. Sometimes the patches can become infected and look weepy with crusts, especially if your toddler scratches them. While eczema usually shows up on babies’ faces, toddlers get the rash around their knees, elbows, and ankles.

Eczema is thought to run in families who have other allergies, too, such as asthma and hay fever. It is not a direct allergic reaction itself, but certain things can trigger it, such as something your toddler eats or comes in contact with, such as wool or chemicals in detergents, soaps, lotions, and fabric softeners. Too much sun can also set off an attack.

Practical treatments can help to soothe the skin during an attack. Daily baths in lukewarm (not hot) water using bath oil and a soap substitute can help, but be careful to not rub the skin when drying off. Moisturizers are soothing. They may need to be applied repeatedly throughout the day, and sometimes moist wraps also can help to soothe the skin. Sunscreen can help to protect the skin from burning. Keeping fingernails trimmed and clean will help to reduce inflammation. (Mittens or socks over your toddler’s hands may help keep him from scratching himself during the night).

A recent study found that soaking a child for 5 to 10 minutes twice a week in a highly diluted bleach bath was five times more effective in treating eczema than plain water. The researchers’ treatment instructions were to stir a scant 2 teaspoons of bleach per gallon into bathwater (or ½ cup per full tub) before your child enters the tub with the caution that your child not be allowed to drink the water. Ask your health-care provider first before trying it.

Fifth Disease

A fine, lacy pink rash starts on the cheeks, giving the toddler a “slapped cheek” look, and it may then move to the backs of the arms and legs. It may show up and disappear over the process of 1 to 2 weeks, especially in response to a toddler bath or irritation. Rarely, the rash is accompanied by a slight fever and achy joints. The rash on the face will usually disappear within 4 days after it shows up, while the rash on the rest of the body will take 3 to 7 days to go away. Usually, the only symptom is the rash, and it will disappear on its own.

German Measles

(See Rubella.)

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease

Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease (HFMD) (coxsackie virus) is common among toddlers, especially children in child care. It is caused by a highly contagious virus, which is mostly spread through coughing and sneezing. The incubation stage is about 3 to 6 days, and, unfortunately, a child is most contagious before he shows any symptoms.

When they do appear, the symptoms include a blistery rash on the hands, feet, and mouth. There may also be an accompanying sore throat, fever, and a general sense of feeling unwell.

If a toddler refuses to eat or drink because his mouth and throat are too sore, it can lead to dehydration, a serious condition that can be detected by decreased urination. If his fever rises above 103°F, see his health-care provider.

Like most viruses, HFMD has no cure, and it simply has to run its course, which takes about 7 to 10 days.

Heart Murmur

Heart murmurs are common in children, and they’re often harmless. “Innocent” or “harmless” heart murmurs, as health-care providers call them, are simply the sound the blood makes as it moves through the chambers of the heart. They may get louder when a child’s heart beats faster, and softer when he’s calm.

More serious murmurs are caused by something wrong with a child’s heart, such as a hole in it, or a leaky or narrow heart valve. If your health-care provider is concerned about what is being heard with the stethoscope, your child may be refered to a pediatric cardiologist (children’s heart doctor). Your child will have an exam, and he may be given tests, such as a chest X-ray, an electrocardiogram (EKG, or ECG), or an echocardiogram (“echo”) to find out what is making the unusual sound. Depending upon the severity of the heart problem, medication or surgery may be options.

Heatstroke

Heat stroke occurs in toddlers when their bodies are unable to cool themselves down because of high temperatures, humidity or becoming dehydrated from insufficient fluids. Young children’s bodies don’t adapt as quickly to heat changes as adults’ do. They don’t sweat very well and can overdo their activities without realizing that they are too hot or thirsty. Fevers and medications can also make toddlers more susceptible to overheating, as can wrapping them up during a cold or flu in an attempt to cure it. (Never, ever leave your toddler in a hot car!)

Heat stroke at this age can be deadly and result in serious organ damage. If your toddler is in trouble, he may spike a high temperature (103°F and above), he may appear red-faced and feel hot and dry, he will have dark urine or none at all, and he may either not sweat at all or have profuse sweating. If he is dehydrated, his mouth will appear dry and parched, his eyes may appear sunken, and his hands and feet may feel cold or look splotchy. He may act sluggish, dizzy, or confused, see things that aren’t there, or even lose consciousness.

If you suspect heat stroke, notify 9-1-1 immediately, and meanwhile, get your child into the shade or inside a cool building. Offer him tepid water to drink. Apply cool or tepid water to the skin and seek out a vent or fan his wet body to help cool him down. Ice packs wrapped in towels and placed under the arms or at his crotch may help. Your child will likely be given fluids containing electrolytes to drink or through a vein.

Hepatitis

There are many types of hepatitis. All are infections of the liver. Some may be silent and hard to detect, while others may result in jaundice—a yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes—combined with nausea and weakness. Other symptoms could seem similar to the flu, such as loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and itchiness. Most children recover from hepatitis, but some go on to have chronic liver problems.

Hepatitis A is a liver inflammation. The virus can be passed through contaminated food, water, or contact with small amounts of an infected person’s bowel movements. It is usually short lived and may not lead to the serious consequences of hepatitis B.

Hepatitis B is a serious infection of the liver transmitted by exposure to an infected person’s blood. It can be transmitted from mother to baby during delivery. Hepatitis B infects more than 200,000 people each year in the United States and 4,000 to 5,000 die as a result of chronic problems relating to it. Since 1991, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have recommended that toddlers be vaccinated against hepatitis B through a series of shots given during the first 6 months after birth.

Hernia

A hernia is the protrusion of an organ through the structure that normally surrounds or contains it. With an umbilical hernia, a bit of intestine or fatty tissue near the navel breaks through the muscular wall of the abdomen. The hernia will bulge out around the belly button when the toddler cries, coughs, or strains.

Umbilical hernias are much more common in African-American toddlers than other races, and they usually resolve on their own by age 4. (Note: Having a permanent “innie” or “outie” belly button is not a hernia).

An inguinal hernia occurs when a small portion of the toddler’s intestine becomes captured in the scrotal sac (that holds his testicles) and causes swelling, tenderness, and redness. It may first happen after a bout of vigorous crying. Since it may cause severe problems with blockage in the intestine, medical intervention may be necessary.

Impetigo

Impetigo is a bacterial skin infection caused by a staph or strep bacterium. It begins as tiny blisters. The blisters burst and leave brown or red wet patches of skin that may weep fluid that forms a yellowish, honeycomblike crust, usually around the nose and mouth or the buttocks, and sometimes the hands and forearms.

Your toddler’s health-care provider may recommend applying an over-the-counter antibiotic ointment or prescribe an oral antibiotic to prevent its spreading. Also be sure to cut your toddler’s nails short to prevent scratching and a spread of the infection.

If applying antibiotic ointment doesn’t make the rash noticeably better in a few days, contact your pediatrician. In rare cases, impetigo may lead to a kidney problem known as glomerulonephritis, which causes the urine to turn dark (cola) brown. In most cases, impetigo is short lived and usually heals completely in children.

Influenza

Typically, flu starts with a fever, fatigue, and chills, followed by a runny nose with clear mucus and a cough. Your toddler may also be irritable and have swollen glands, arch his back with abdominal pain, have smelly, explosive diarrhea, and projectile vomiting.

In other words, if your toddler gets the flu, it’s going to be a long, long night. Your health-care provider may want to examine your toddler to be sure that there are no other causes, and she might tell you that the most you can do is keep the toddler fed and hydrated, and be on the lookout for a high fever or signs of dehydration (sunken eyes and decreased urination).

Your health-care provider may prescribe an antiviral medication that can lessen the symptoms and shorten the length of the flu by a day or two. The trick is in making the diagnosis as soon as possible, because the medication must be given in the first 48 hours. Once that 48-hour window closes, the antiviral medications are no longer effective.

Also, you may be able to prevent your toddler from catching the flu in the first place by asking your health-care provider to give your toddler a flu shot at the beginning of flu season (usually in late fall).

Measles

Measles is a highly contagious viral illness characterized by coldlike symptoms, fever, cough, conjunctivitis (pinkeye), and a deep red rash that starts on the face. Around the fourth day, the toddler will seem more ill as the rash spreads over the rest of the body.

Over the last few decades, measles cases have decimated in the United States and Canada because of widespread immunization. Before widespread immunization, measles was so common during childhood that the majority of the population had been infected by age 20. Rarely, measles can develop into pneumonia, encephalitis (brain swelling), and ear infections. (See also Rubella, below.)

Meningitis

Meningitis is a rare but sometimes deadly infection of the tissues that cover the brain, and it can be deadly within a matter of hours. The beginning signs of meningitis are subtle and not very different from coming down with a bad cold. There may be fever, vomiting, and a general feeling of unwell. Your child may complain that his head or neck area hurts and he seems to dislike bright lights.

As meningitis progresses, your toddler may have seizures or become extremely sluggish, sleepy, and difficult to wake, which calls for racing to the emergency room. Sometimes a rash may be involved (be sure to tell your child’s healthcare provider about that).

A blood test to check for a bacterial infection may be called for, and possibly a spinal tap to see if the spinal fluid is infected. If meningitis is treated aggressively and quickly with antibiotics, the crippling and long-lasting effects of the disease can be minimized.

Mononucleosis

Mononucleosis (“mono,” or glandular fever) is caused by Epstein-Barr virus (EBV). Although it is more common among teenagers, it can also affect young children. In younger children there may be only a mild fever, and the child may not appear ill, but other symptoms may include being more tired than usual and having swollen lymph nodes (small, round infection-fighting lymph glands in different places on the body), and a mild fever.

A specific blood test for mono is available. It is transmitted by fluids from the nose and throat and sharing of utensils or cups. There is no current treatment for mono except plenty of rest. Once a child gets over the active phase, it will remain active in his body throughout his life and it may occasionally reactivate.

Mumps

Mumps is a highly contagious viral infection that spreads from child to child through saliva. It can be caught by sharing eating utensils or drinks, or even breathing the air immediately after someone has sneezed or coughed.

The first symptoms are usually mild: a fever and loss of appetite. Then, within a week, the area in front of your toddler’s ears, the parotid glands, will noticeably swell, giving your child a chipmunk appearance. Other symptoms could also include a stiff neck (see also meningitis), sluggishness and weakness, and painful chewing and swallowing. Sometimes mumps will affect the salivary glands under the tongue or chin or in the chest area.

Since it is caused by a virus, antibiotics don’t help, but having your child innoculated with the MMR vaccine before he is exposed to it can help to protect him from it. Generally, having mumps conveys lifelong immunity to catching it again. (See immunization table.)

Pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammation or infection of the lungs, when the air sacs fill with pus, mucus, and other liquid that interferes with their functioning. There are multiple causes and types of pneumonia. The symptoms of bacterial pneumonia are a fever, chills, rapid breathing, fast heart rate, a wet cough, abdominal pain, and vomiting, with the toddler becoming sicker over time.

Viral pneumonia is marked by a low fever, no chills, and a lingering cough, but with the toddler seeming almost normal and with symptoms persisting for 3 to 4 weeks. Lobar pneumonia refers to pneumonia in a section (lobe) of a lung, while bronchial pneumonia (or bronchopneumonia) refers to pneumonia that affects patches throughout both lungs.

In serious cases of pneumonia oxygen can’t reach the blood, and when there is insufficient oxygen in the blood, body cells can’t function properly and may die. Prompt treatment with antibiotics and oxygen almost always cures bacterial pneumonia, but treating it aggressively and early is important.

Ringworm

Ringworm is a harmless and sometimes itchy skin inflammation that often appears as a round ring of tiny blisters with a sharp border between the skin and the dime- to quarter-sized lesions, often with clear skin inside the ring. It is not caused by a worm, but by one or two types of fungus, Trichophyton and Microsporum, and it often shows up on the face, trunk, or limbs.

It is easily treated by topical, over-the-counter antifungal creams that contain clotrimazole (brand name Lotrimin or Mycelex) and are applied twice a day to the reddened area and surrounding skin. Your health-care provider will be able to recommend the most effective treatment.

The fungi in the rash are contagious by direct contact with the rash or from the hands of an infected person who has been scratching the rash. Your child can also catch it from infected pets, especially dogs and cats.

It will disappear with treatment after several weeks.

Roseola

Roseola infantum is a very common viral illness found in children all over the world. In the United States, about one in three children have some kind of roseola, and 86 percent of children have acquired the virus’ antibodies by 1 year of age.

Your toddler could be a carrier for the virus and neither show symptoms nor appear ill, or he could suddenly develop a fever between 102°F and 104°F that lasts for 3 to 5 days. In some cases, the sudden rise in the fever may lead to febrile seizures (see Febrile Seizures).

Your toddler will have decreased appetite, mild diarrhea, a slight cough, and a runny nose, and seem more irritable and sleepy than usual. His eyelids may seem swollen and droopy.

The fever will likely break on about the third day and be followed by a faint, pink rash (not red as with measles) on the toddler’s trunk, arms, and legs that will last about a day. After the fever subsides, a faint, pink rash develops on the body, spreads to the upper arms and neck, and then disappears in a day or so. Your toddler’s health-care provider may prescribe medications to increase comfort.

Rotavirus

Rotavirus is responsible for approximately 5 to 10 percent of all cases of diarrhea among children under 5 years of age. It accounts for more than 500,000 physician visits and approximately 55,000 to 70,000 hospitalizations each year among children under 5 years of age, and, sadly, an estimated 1 in 200,000 toddlers worldwide with rotavirus diarrhea die from the complications of the infection.

Symptoms can be mild to severe. It begins with few or no symptoms, or a mild to moderate fever followed by severe vomiting followed by diarrhea. The incubation period is about 2 days before symptoms appear, starting with vomiting followed by 4 to 8 days of profuse diarrhea. It is highly contagious and usually spread when children touch or place in their mouths small, usually invisible amounts of fecal matter found on surfaces such as toys, books, and clothing, or on the hands of caregivers. It can also be transmitted through contaminated water or food, and possibly by respiratory droplets in a sneeze, cough, or exhalation.

Dehydration is the most dangerous side effect of the virus. Your health-care provider will guide you in how to provide hydration, such as electrolyte solutions (Pedialyte), to keep your toddler well hydrated. Severe cases may require hospitalization with intravenous fluids.

Rotavirus can be prevented with a vaccination that usually is administered in 2 doses during infancy. Once a child has it, later infections are apt to be less severe as his immune system may provide some protection.

RSV

RSV stands for respiratory syncytial (pronounced “sin- SHISH-al”) virus. It infects most children sooner or later (usually by the age of 2), but during toddlerhood, it is rarely more troublesome for a child than the common cold. (It is more serious in babies and can cause serious respiratory infections such as bronchiolitis and pneumonia.)

RSV begins with coldlike symptoms, such as a runny or stuffy nose, a minor cough, and fever, with the cough becoming more pronounced after a few days. In severe cases, your toddler may have labored breathing (faster than 40 breaths per minute), flared nostrils, rib cage expanding more than usual, wheezing or grunting when breathing, bluish lips or fingernails, and a fever that rises to over 103°F—all of which are signs to contact your health-care provider.

Because RSV is a virus, antibiotics and other medications aren’t effective. Milder symptoms usually last 5 to 7 days and go away on their own, but the cough may linger for weeks longer. Severe forms may call for hospitalization for oxygen treatments, intravenous fluids, and drugs to help open your toddler’s airways.

A vaccination is available called Synagis, but the protection is only temporary and monthly shots may need to be given during RSV season, between October and April.

Rubella

Sometimes called “3-day measles” or German measles, this virus starts with mild symptoms of illness, such as a low-grade fever, a slight cold, or flulike indications. Then, a pinkish red, spotted rash develops, first on the toddler’s face and rapidly spreads to the trunk. It disappears after the third day. The toddler will look unwell and may have swollen glands behind the ears or nape of the neck but will recover within a few days. Contact your toddler’s health-care provider, although no medical treatment is usually needed.

More rarely, rubella can lead to brain swelling or a problem with bleeding. It is the most dangerous when mothers without immunity catch it and transmit it to their babies in utero during certain months of pregnancy. It can cause a fetus to be stillborn, or to be born blind or deaf or with learning disabilities. Rubella immunization is part of MMR shots (see immunization chart).

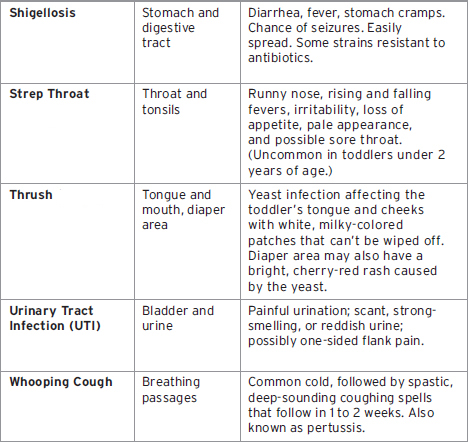

Shigellosis

Shigellosis is an infectious disease caused by a group of bacteria called Shigella. Toddlers who are infected with Shigella develop diarrhea, fever, and stomach cramps 1 or 2 days after being exposed to the bacterium, and diarrhea is often bloody.

The bacteria are present in the diarrheal stools of infected person while they are sick and for a week or two afterward, and it can be passed by soiled fingers from one person to another by mouth, particularly between children who are still wearing diapers. It also can be caught by swimming in contaminated water or eating vegetables that have been grown in fields contaminated by sewage.

It is more common during the summer months and in toddlers from 2 to 4 years of age. In some young children, the diarrhea can be so severe and the risks of dehydration so severe that hospitalization may be recommended. A high fever may also be associated with seizures in children younger than 2 years of age. Some persons who are infected may have no symptoms at all, but may still pass the Shigella bacteria to others.

Children with mild infections will usually recover quickly without antibiotic treatment, but it may take several months until their bowel habits return to normal. Some forms can later lead to Reiter’s syndrome, which causes joint pain, eye irritation, and painful urination that can last for months or years, and possibly lead to chronic arthritis.

Effective treatment depends on which germ is causing the diarrhea. Usually it is treated with antibiotics to kill it and shorten the illness. Unfortunately, some Shigella bacteria have become resistant to antibiotics and using antibiotics to treat shigellosis can actually make the germs more resistant in the future.

TIP

Avoid antidiarrheal medicines to treat shigellosis, as they are likely to make the illness worse.

Strep Throat

Officially called streptococcal pharyngitis, strep throat is caused by streptococcal bacteria. In children, the infection can cause red, swollen tonsils covered in a white, smelly material, red patches on the roof of the mouth, a white tongue, a high fever, swollen glands, abdominal pain, vomiting, and trouble swallowing. Neck glands may also be swollen.

In toddlers the symptoms are usually milder, and include a runny nose, rising and falling fevers, irritability, loss of appetite, and a pale appearance. The infection usually lasts about a week, but some toddlers can have chronic strep infections that last longer.

Your health-care provider will collect a culture from your toddler’s nose or throat to confirm that the infection is strep. Then it will be decided whether antibiotics will be needed to prevent more serious complications such as ear and sinus infections, or involvement of other organs such as the lungs, brain, or kidneys, or rheumatic fever. (Note: Strep throat is very rare in children under 2 years of age.)

Thrush

If your toddler’s tongue and cheeks stay coated in white patches that won’t wipe away, he may have thrush, a fungal problem. This yeast infection grows in moist places on the inside and on the skin, and it may also appear as red, irritated patches in the folds of your toddler’s skin, such as the neck, the armpits, and the thighs. Sometimes a cherry red diaper rash that doesn’t clear up easily can also be caused by yeast. Your health-care provider will suggest medication to treat it.

Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)

A urinary tract infection causes irritation of the lining of the bladder, urethra, ureters, or kidneys, just like the inside of the nose or the throat becomes irritated with a cold. The signs of a UTI may not be clear, since a toddler may not be able to describe how he is feeling. Sometimes symptoms include a high fever, irritability, and loss of appetite. And some children have a low-grade fever, nausea, and vomiting.

Urine may have an unusual smell, and your toddler may urinate more than usual. If he has a high temperature and appears sick for more than a day without signs of a runny nose or other obvious cause for discomfort, he or she may need to be checked for a bladder infection. If the kidney is infected, a child may complain of pain under the side of the rib cage, called the flank, or low back pain.

Crying or complaining that it hurts to urinate and producing only a few drops of urine at a time are other signs of urinary tract infection, or a child may have difficulty controlling the urine and may leak urine into clothing or bed sheets, and it could smell unusual or look cloudy or red.

If a urinary tract infection is suspected, your child’s urine will be collected. Toddlers who are not yet toilet trained may be fitted with a plastic collection bag over the genital area that is sealed with an adhesive strip. An older child may be asked to urinate into a container, or a small tube may be directly fed into the urethra to directly drain into a container, or a needle may be placed directly into the bladder through the skin of the lower abdomen.

Urinary tract infections are treated with antibiotics.

Whooping Cough (Pertussis)

Also known as pertussis, whooping cough is a highly contagious respiratory illness that used to kill thousands of people every year. But now, thanks to the DTaP vaccine, there are only a handful of deaths from the disease every year. Still, cases of pertussis seem to be on the rise, particularly among infants younger than 6 months who are not yet protected by immunizations, and in young adults whose childhood vaccines have begun to wear off.

If your toddler develops a spastic, honking cough, and possibly vomits after coughing, contact his health-care provider, who will probably prescribe antibiotics. Your toddler will be contagious until the course of the medication has been completed, which is about 5 days.

ACCIDENT-PROOFING YOUR TODDLER

Protecting your exploring toddler from his own curiosity is a full-time job! Your ever-moving child is driven by a powerful, innate urge to explore the world: to see, taste, and experience everything that attracts him.

Emergency Medical Restraint

If your child has been injured and needs treatment but isn’t able to cooperate, you may need to help medical personnel in restraining him so he can be examined or treated. Here’s how to hold your tot with your body to keep him still so he can be helped:

• Get into a sitting position. Sit in a chair or on the floor with your back against a wall.

• Place your child in your lap. Sit your child on your lap with his back to you.

• Hold his legs between yours. Cross your legs so that his legs are held still in between yours.

• Use one hand on his forehead. Gently press your child’s head toward your chest so you can talk softly to him in his ear.

• Hold him across his chest. Cross his chest with your other arm so that both of his arms are held in place.

• Unwind. Once your child has calmed down or the procedure has ended, start by slowly letting his legs go, followed by his arms and then his head.

When Your Toddler Should Stay Home from Child Care

Most child-care centers have their own rules about when kids have to stay home and when they can come back after illnesses, but here’s a quick reference guide to help you make the decision.

• Fever. Your toddler has a temperature according to the definition given by your toddler’s child-care provider.

• Breathing problems. Difficulty breathing, wheezing, or coughing.

• Diarrhea. Blood in stools not explainable by dietary change or medication.

• Vomiting. Two or more episodes in the previous 24 hours.

• Persistent abdominal pain. Complains of unusual belly pain that continues for more than 2 hours.

• Mouth sores. Outbreak on the lips, inside the mouth, or in the throat.

• Rash. Combined with a fever or overall sense of illness.

• Eye infection. Purulent conjunctivitis (“pinkeye”) with thick discharge from the eye, until after treatment has started.

Unfortunately, a toddler isn’t very discerning. He’ll try to open the bleach bottle, perch precariously on a second-story window ledge, and race unknowingly into traffic. He’ll pull any dog’s tail, drag down kitchen pots, and tug on electrical cords.

Many toddlers are raced to emergency rooms every year with serious injuries sustained from accidents in and around their homes and even from playgrounds designed for children. Most often, these accidents arise from toddlers just acting like toddlers.

What seems like simple exploration and play can turn tragic in only a matter of minutes when an adult is momentarily distracted by something else.

Hazards Inside Your Home

If you have a toddler, you’ve probably already discovered that all the decorative touches in the home, like figurines, ceramics, and glass objects, need to be put out of reach.

Pathways need to be as safe as possible to help reduce tripping. Electrical cords, throw rugs, and other “loose” things that could trip your toddler should be kept out of the way.

The truth is, during the toddler years, the most innocuous things can be potential dangers for a fearless and curious toddler. Low shelves can be climbed, appliance or floor-lamp cords could be pulled, and coffee tables can become stages of disaster.

Here’s a list of some potential hazards around the home and some easy solutions:

• Bureaus and shelves. Simple chests with drawers and open shelves don’t look dangerous, but when tots try to use them as steps for getting to the top, they can be downright deadly. Drawers can also drop out, crashing on small heads, hands, or feet. Too often television sets tumble from the tops of dressers, too.