HABIT 1

BE PROACTIVE

As I mentioned in the original 7 Habits book, many years ago when I was in Hawaii on a sabbatical, I was wandering through some stacks of books in the back of a college library. A particular book drew my interest, and as I flipped through the pages, my eyes fell on a single paragraph that was so compelling, so memorable, so staggering that it has profoundly influenced the rest of my life.

In that paragraph were three sentences that contained a single powerful idea:

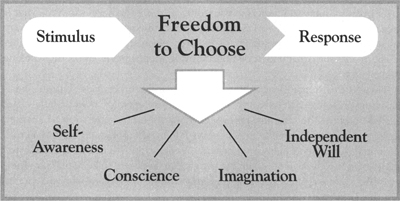

Between stimulus and response, there is a space.

In that space lies our freedom and power to choose our response.

In our response lies our growth and our happiness.

I cannot begin to describe the effect that idea had on me. I was overwhelmed by it. I reflected on it again and again. I reveled in the freedom of it. I personalized it. Between whatever happened to me and my response to it was a space. In that space was my freedom and power to choose my response. And in my response lay my growth and happiness.

The more I pondered it, the more I realized that I could choose responses that would affect the stimulus itself. I could become a force of nature in my own right.

This experience was forcibly brought to my mind again when I was in the middle of a taping session one evening and received a note saying that Sandra was on the phone and needed to speak to me.

“What are you doing?” she asked with impatience in her tone. “You knew we were having guests for dinner tonight. Where are you?”

I could tell she was upset, but as it happened, I had been involved all day in taping a video in a mountain setting. When we got to the final scene, the director insisted that it be done with the sun setting in the West, so we had to wait for nearly an hour to achieve this special effect.

In the midst of my own pent-up frustration over all these delays, I replied curtly, “Look, Sandra, it’s not my fault that you scheduled the dinner. And I can’t help it that things are running behind here. You’ll have to figure out how to handle things at home, but I can’t leave. And the longer we talk now, the later I’ll be. I have work to do. I’ll come when I can.”

As I hung up the phone and started walking back to the shoot, I suddenly realized that my response to Sandra had been completely reactive. Her question had been reasonable. She was in a tough social situation. Expectations had been created, and I wasn’t there to help fulfill them. But instead of understanding, I had been so filled with my own situation that I had responded abruptly—and that response had undoubtedly made things even worse.

The more I thought about it, the more I realized that my actions had really been off track. This was not the way I wanted to behave toward my wife. These were not the feelings I wanted in our relationship. If I had only acted differently, if I had been more patient, more understanding, more considerate—if I had acted out of my love for her instead of reacting to the pressures of the moment, the results would have been completely different.

But the problem was that I didn’t think about it at the time. Instead of acting based on the principles I knew would bring positive results, I reacted based on the feeling of the moment. I got sucked into the emotion of the situation, which seemed so overpowering, so consuming at the time that it completely blinded me to what I really felt deep inside and what I really wanted to do.

Fortunately, we were able to complete the taping quickly. As I drove home, it was Sandra—and not the taping—that was on my mind. My irritation was gone. Feelings of understanding and love for her filled my heart. I prepared to apologize. She ended up apologizing to me as well. Things worked out, and the warmth and closeness of our relationship were restored.

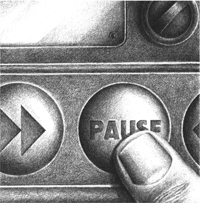

Creating a “Pause Button”

It is so easy to be reactive! Don’t you find this to be the case in your own life? You get caught up in the moment. You say things you don’t mean. You do things you later regret. And you think, “Oh, if only I had stopped to think about it, I never would have reacted that way!”

Obviously, family life would be a whole lot better if people acted based on their deepest values instead of reacting to the emotion or circumstance of the moment. What we all need is a “pause button”—something that enables us to stop between what happens to us and our response to it, and to choose our own response.

It’s possible for us as individuals to develop this capacity to pause. And it’s also possible to develop a habit right at the center of a family culture of learning to pause and give wiser responses. How to create that pause button in the family—how to cultivate the spirit of acting based on principle-centered values instead of reacting based on feelings or circumstance—is the focus of Habits 1, 2, and 3.

Your Four Unique Human Gifts

Habit 1—Be proactive—is the ability to act based on principles and values rather than reacting based on emotion or circumstance. The ability to do that comes from the development and use of four unique human gifts that animals do not have.

To help you understand what those gifts are, let me share with you how a single mother used them to become an agent of change in her family. She said:

For years I fought with my children and they fought with each other. I constantly judged, criticized, and scolded. Our home was filled with contention, and I knew my constant nagging was hurting my children’s self-esteem.

Again and again I resolved to try to change, but each time I would fall back into negative habit patterns. The whole situation caused me to hate myself and take my anger out on my children, and that made me feel even more guilty. I felt that I was caught in a downward spiral which started in my childhood and which I was helpless to do anything about it. I knew something had to be done, but I didn’t know what.

Eventually, I decided to make my problems a matter of sustained thought, meditation, and specific and earnest prayer. I gradually came to two insights about the real motives for my negative, critical behavior.

First, I came to see more clearly the impact my own childhood experiences had on my attitude and behavior. I began to see the psychological scarring of my own upbringing. My childhood home was broken in almost every way. I can’t remember ever seeing my parents talk through their problems and differences. They would either argue and fight, or they’d angrily go their separate ways and use the silent treatment. Sometimes that would last for days. My parents’ marriage eventually ended in divorce.

So when I had to deal with these same issues and problems with my own family, I didn’t know what to do. I had no model, no example to follow. Instead of finding a model or working it through within myself, I would take out my frustration and my confusion on the kids. And as much as I didn’t like it, I found myself dealing with my children exactly as my parents had dealt with me.

The second insight I gained was that I was trying to win social approval for myself through my children’s behavior. I wanted to get other people to like me because of their good behavior. I constantly feared that instead of winning approval, my children’s behavior would embarrass me. Because of that lack of faith in them, I instructed, threatened, bribed, and manipulated my kids into behaving the way I wanted them to behave. I began to see that my own hunger for approval was keeping my children from growth and responsibility. My actions were actually helping to create the very thing I feared: irresponsible behavior.

Those two insights helped me realize that I needed to conquer my own problems instead of trying to find solutions by getting others to change. My unhappy, confused childhood inclined me to be negative, but it didn’t force me to be that way. I could choose to respond differently. It was futile to blame my parents or my circumstances for my painful situation.

I had a very hard time admitting this to myself. I had to struggle with years of accumulated pride. But as I gradually swallowed the bitter pill, I discovered a marvelously free feeling. I was in control. I could choose a better way. I was responsible for myself.

Now when I get into a frustrating situation, I pause. I examine my tendencies. I compare them against my vision. I back away from speaking impulsively or striking out. I constantly strive for perspective and control.

Because the struggle continues, I retire frequently to the solitude of my own inner self to recommit to win my battles privately, to get my motives straight.

This woman was able to create a pause button or a space between what happened to her and her response to it. And in that space she was able to act instead of react. Now how did she do that?

Notice how she was able to step back and almost observe herself—to become aware of her own behavior. This is the first unique human gift: self-awareness. As humans we can stand apart from our own life and observe it. We can even observe our thoughts. We can then step in to make changes and improvements. Animals cannot do this, but we can. This mother did. And it led her to important insights.

The second gift she used was her conscience. Notice how her conscience—her moral or ethical sense or “inner voice”—let her know deep inside that the way she was treating her children was harmful, that it was taking her and her children down the same heartbreaking path that she had walked as a child. Conscience is another unique human gift. It enables you to evaluate what you observe about your own life. To use a computer metaphor, we could say that this moral sense of what is right and wrong is embedded in our “hardware.” But because of all of the cultural “software” we pick up and because we misuse, disregard, and neglect this special gift of conscience, we can lose contact with this moral nature within us. Conscience gives us not only a moral sense but a moral power. It represents an energy source that aligns us with the deepest and finest principles contained in our highest nature. All six of the major religions of the world—in one way or another and using different language—teach this basic idea.

Now notice the third gift she used: imagination. This is her ability to envision something entirely different from her past experience. She could envision or imagine a far better response, one that would work in both the short and the long term. She recognized this capacity when she said, “I was in control. I could choose a better way.” And because she was self-aware, she could examine her tendencies and compare them against her vision of that better way.

And what is the fourth gift? It’s independent will—the power to take action. Listen to her language again: “I back away from speaking impulsively or striking out. I constantly strive for perspective and control” and “Because the struggle continues, I retire frequently to the solitude of my own inner self to recommit, to win my battles privately, to get my motives straight.” Just look at her tremendous intention and the willpower she’s exercising! She’s swimming upstream—even against deeply embedded tendencies. She’s getting a grip on her life. She’s willing it. She’s making it happen. Of course it’s hard. But that’s the essence of what true happiness is: subordinating what we want now for what we want eventually. This woman has subordinated her impulse to get back, to justify herself, to win, to satisfy her ego—all in the name of the wisdom that her awareness, conscience, and imagination have given her—because what she wants eventually is something far greater, far more powerful in the spirit of the family than the short-term ego gratification she had before.

These four gifts—self-awareness, conscience, creative imagination, and independent will—reside in the space we humans have between what happens to us and our response to it.

Animals have no such space between stimulus and response. They are totally a product of their natural instincts and training. Although they also possess unique gifts we don’t have, they basically live for survival and procreation.

But because of this space in human beings, there is more—infinitely more. And this “more” is the life force, the propensity that keeps us ever becoming. In fact, “grow or die” is the moral imperative of all existence.

Since the cloning in Scotland of a sheep named Dolly, there has been renewed interest in the possibility of cloning people and the question of whether it is ethical. So far, much of the discussion is based on the assumption that people are simply more advanced animals—that there is no space between stimulus and response and that we are fundamentally a product of nature (our genes) and nurture (our training, upbringing, culture, and present environment).

But this assumption does not begin to explain the magnificent heights that people such as Gandhi, Nelson Mandela, or Mother Teresa have climbed, or as many of the great mothers and fathers in the stories in this book have achieved. That is because deep in the DNA—in the chromosomal structure of the nucleus of every cell of our body—is the possibility of more development and growth and higher achievements and contribution because of the development and use of these unique human gifts.

Now as this woman learns how to develop and use her pause button, she is becoming proactive. She’s also becoming a “transition person” in her family—that is, she’s stopping the transmission of tendencies from one generation to another. She’s stopping it with herself. She’s stopping it in herself. She’s suffering, if you will, to some degree, which helps burn out the intergenerational dross—this inherited tendency, this well-developed habit to get back, to get even, to be right. Her example is like wildfire to the seedbed of the family culture, to everyone who had entered into this retaliating, contentious, fighting spirit.

Can you imagine the good this woman is doing, the change she’s bringing about, the modeling she’s providing, the example she’s giving? Slowly, subtly, perhaps almost imperceptibly she is bringing about a profound change in the family culture. She’s writing a new script. She has become an agent of change.

We all have the ability to do this, and nothing is more exciting. Nothing is more ennobling, more motivating, more affirming, more empowering than the awareness of these four gifts and how they can combine together to bring about fundamental personal and family change. Throughout this book we will explore these gifts in depth through the experiences of people who have developed and used them.

The fact that we have these four unique gifts means no one has to be a victim. Even if you came from a dysfunctional or abusive family, you can choose to pass on a legacy of kindness and love. Even if you just want to be kinder and more patient and respectful than some of the models you’ve had in your life, cultivating these four gifts can nourish that seed of desire and explode it, enabling you to become the kind of person, the kind of family member you really want to be.

A “Fifth” Human Gift

As Sandra and I have looked back at our family life over the years, we’ve come to the conclusion that, in one sense, we could say there is a fifth human gift: a sense of humor. We could easily place humor along with self-awareness, imagination, conscience, and independent will, but it is really more of a second order human gift because it emerges from the blending of the other four. Gaining a humorous perspective requires self-awareness, the ability to see the irony and paradox in things and to reassert what is truly important. Humor draws upon creative imagination, the ability to put things together in ways that are truly new and funny. True humor also draws on conscience so that it is genuinely uplifting and doesn’t fall into the counterfeit of cynicism or putting people down. It also involves willpower in making the choice to develop a humorous mind-set—to not be reactive, to not be overwhelmed.

Although it is a second order human gift, it is vitally important to the development of a beautiful family culture. In fact, I would say that in our own family the central element that has preserved the sanity, fun, unity, togetherness, and magnetic attraction of our family culture is laughter—telling jokes, seeing the “funny” side of life, poking holes at stuffed shirts, and simply having fun together.

I remember one day when our son Stephen was very young, we stopped at the dairy to get some ice cream. A woman came rushing in, zooming past us in a big hurry. She grabbed two bottles of milk and hurried to the cash register. In the rush, the momentum caused the heavy bottles to bang together, exploding and causing glass and milk to fly all over the floor. The whole place became totally silent. All eyes were on her in her drenched and embarrassed state. No one knew what to do or say.

Suddenly, little Stephen piped up: “Have a laugh, lady! Have a laugh!”

She and everyone else instantly broke out laughing, putting the incident into perspective. Thereafter, when any of us overreacted to a minor situation, someone would say, “Have a laugh!”

We enjoy humor even around our tendency to be reactive. For example, we once saw a Tarzan film together, and we decided to learn a little of the repertoire of the monkeys. So now when we realize we’re beginning to get a little reactive, we act out this repertoire. Someone will start, and we’ll all join in. We scratch our sides and shout, “Ooo! ooo! ooo! ah! ah! ah!” For us this clearly communicates “Hold it! There’s no space here between stimulus and response. We’ve become animals.”

Laughter is a great tension releaser. It’s a producer of endorphins and other mood-altering chemicals in the brain that give a sense of pleasure and relief from pain. Humor is also the humanizer and equalizer in relationships. It’s all of these things—but it’s also much, much more! A sense of humor reflects the very essence of “We’re off track—but so what?” It puts things in proper perspective so that we don’t “sweat the small stuff.” It enables us to realize that, in a sense, all stuff is small. It keeps us from taking ourselves too seriously and being constantly uptight, constricted, demanding, overexacting, disproportionate, imbalanced, and perfectionistic. It enables us to avoid the hazard of being so immersed in moral values or so wrapped up in moral rigidity that we’re blind to our own humanness and the realities of our situation.

People who can laugh at their mistakes, stupidities, and rough edges can get back on track much faster than those perfectionistic souls who place themselves on guilt trips. A sense of humor is often the third alternative to guilt tripping, perfectionistic expectations, and an undisciplined, loosey-goosey, “anything goes” lifestyle.

As with anything else, humor can be carried to excess. It can result in a culture of sarcasm and cutting humor, and it can even produce light-mindedness where nothing is taken seriously.

But true humor is not light-mindedness; it’s lightheartedness. And it is one of the fundamental elements of a beautiful family culture. Being around merry, cheerful people who are upbeat and full of good stories and good humor is the very thing that makes people want to be with others. It’s also a key to proactivity because it gives you a positive, uplifting, nonreactive way to respond to the ups and downs of daily life.

Love Is a Verb

At one seminar where I was speaking on the concept of proactivity, a man came up and said, “Stephen, I like what you’re saying, but every situation is different. Look at my marriage. I’m really worried. My wife and I just don’t have the same feelings for each other that we used to have. I guess I just don’t love her anymore, and she doesn’t love me. What can I do?”

“The feeling isn’t there anymore?” I inquired.

“That’s right,” he reaffirmed. “And we have three children we’re really concerned about. What do you suggest?”

“Love her,” I replied.

“I told you, the feeling just isn’t there anymore.”

“Love her.”

“You don’t understand. The feeling of love just isn’t there.”

“Then love her. If the feeling isn’t there, that’s a good reason to love her.”

“But how do you love when you don’t love?”

“My friend, love is a verb. Love—the feeling—is a fruit of love the verb. So love her. Sacrifice. Listen to her. Empathize. Appreciate. Affirm her. Are you willing to do that?”

Hollywood has scripted us to believe that love is a feeling. Relationships are disposable. Marriage and family are matters of contract and convenience rather than commitment and integrity. But these messages give a highly distorted picture of reality. If we return to our metaphor of the airplane flight, these messages are like static that garbles the clear direction from the radio control tower. And they get many, many people off track.

“We do not have to love. We choose to love.”

Just look around you—maybe even in your own family. Anyone who has been through a divorce, an estrangement from a companion, a child, or a parent, or a broken relationship of any kind can tell you that there is deep pain, deep scarring. And there are long-lasting consequences that Hollywood usually doesn’t tell you about. So while it may seem “easier” in the short run, it is often far more difficult and more painful in the long run to break up a relationship than to heal it—particularly when children are involved.

As M. Scott Peck has said:

The desire to love is not itself love.… Love is an act of will—namely an intention and an action. Will also implies choice. We do not have to love. We choose to love. No matter how much we may think we are loving, if we are in fact not loving, it is because we have chosen not to love and therefore do not love despite our good intentions. On the other hand, whenever we do actually exert ourselves in the cause of spiritual growth, it is because we have chosen to do so. The choice to love has been made.1

I have one friend who uses his gifts to make a powerful proactive choice every day. When he comes home from work, he sits in his car in the driveway and pushes his pause button. He literally puts his life on pause. He gets perspective. He thinks about the members of his family and what they are doing inside the walls of his house. He considers what kind of environment and feeling he wants to help create when he goes inside. He says to himself, “My family is the most enjoyable, the most pleasant, the most important part of my life. I’m going to go into my home and feel and communicate my love for them.”

When he walks through the door, instead of finding fault and becoming critical or simply going off by himself to relax and take care of his own needs, he might dramatically shout, “I’m home! Please try to restrain yourselves from hugging and kissing me!” Then he might go around the house and interact in positive ways with every family member—kissing his wife, rolling around on the floor with the kids, or doing whatever it takes to create pleasantness and happiness, whether it’s taking out the garbage or helping with a project or just listening. In doing these things he rises above his fatigue, his challenges or setbacks at work, his tendencies to find fault or be disappointed in what he may find at home. He becomes a conscious, positive creative force in the family culture.

Think about the proactive choice this man is making and the impact it has on his family! Think about the relationships he’s building and about how that is going to impact every dimension of family life for years, perhaps for generations to come!

Any successful marriage, any successful family takes work. It’s not a matter of accident, it’s a matter of achievement. It takes effort and sacrifice. It takes knowing that—“for better or worse, in sickness and in health, as long as you live”—love is a verb.

Developing Your Unique Human Gifts

The four unique gifts we’ve talked about are common to all people except perhaps some who are sufficiently mentally handicapped that they lack self-awareness. But developing them takes conscious effort.

It’s like developing a muscle. If you’ve ever been into muscle development, you know that the key is to push the fiber until it breaks. Then nature overcompensates in repairing the broken material, and the fiber becomes stronger within forty-eight hours. You probably also know the importance of adjusting your exercises to bring into play the weaker muscles rather than taking the course of least resistance and staying only with those muscles that are strong and developed.

Because of my own knee and back problems, I have had to learn to exercise in a way that forces me to bring into play muscles and even entire muscle groups that I would otherwise rarely use or even be aware of. I realize now that the development of these muscles is necessary for an integrated, balanced level of health and fitness, for posture, for various skill activities, and sometimes even for normal walking. For example, to compensate for my knee injuries, I used to focus on developing the quadriceps—the muscles in the front of the upper leg—but I neglected the development of the hamstrings, which are the muscles at the back of the leg. And this affected a full, balanced recovery of my knees and also my back.

So it is in life. Our tendency is to run with our strengths and leave our weaknesses undeveloped. Sometimes that’s fine, when we can organize to make those weaknesses irrelevant through the strengths of others, but most of the time it isn’t fine because the full utilization of our capacities requires overcoming those weaknesses.

And so it is with our unique human gifts. As we go through life interacting with external circumstances, with other people, and with our own nature, we have constant ongoing opportunities to come face-to-face with our weaknesses. We can choose to ignore them, or we can push against the resistance and break through to new levels of competence and strength.

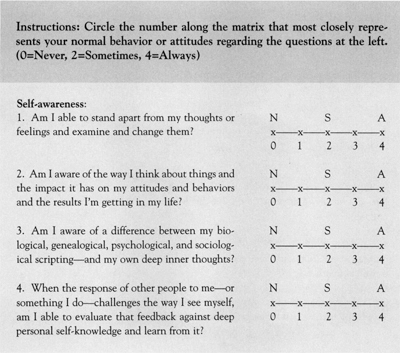

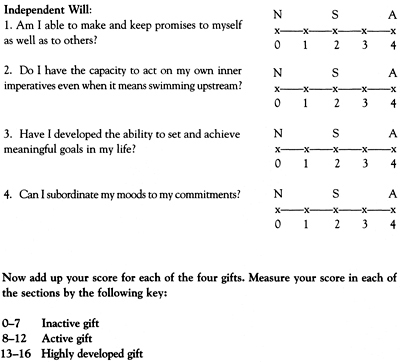

Consider the development of your own gifts as you go through the following questionnaire:2

I have done this questionnaire many times with thousands of people in many different settings, and the overwhelming finding is this: The gift most neglected is self-awareness. Perhaps you have heard the expression “Think outside the box,” meaning to get outside the normal way of thinking, the normal assumptions and paradigms in which we operate. That’s another expression for using self-awareness. Until the gift of self-awareness is cultivated, the use of conscience, imagination, and willpower will always be “within the box”—that is, within one’s own life experience or one’s present way of thinking or paradigm.

So in a sense the unique leveraging of the four human gifts is in self-awareness, because when you have the ability to think outside the box—to examine your own assumptions and your own way of thinking, to stand apart from your own mind and examine it, to think about your very thoughts, feelings, and even moods—then you have the basis for using imagination, conscience, and independent will in entirely new ways. You literally become transcendent. You have transcended yourself; you have transcended your background, your history, your psychic baggage.

This transcendence is fundamental to the life force in all of us and helps unleash the propensity to become, to grow, to develop. It is also fundamental in our relationships with others and in cultivating a beautiful family culture. The more the family has a collective sense of self-awareness, the more it can look in on itself and improve itself: make changes, select goals outside of tradition, and set up structures and other plans to achieve those goals that lie outside social scripting and deeply established habit patterns.

The ancient Greek saying “Know thyself”3 is enormously significant because it reflects the understanding that self-knowledge is the basis of all other knowledge. If we don’t take ourselves into account, all we are doing is projecting ourselves onto life and onto other people. We then judge ourselves by our motives—and others by their behavior. Until we know ourselves and are aware of ourselves as separate from others and from the environment—until we can be separated even from ourselves so that we can observe our own tendencies, thoughts, and desires—we have no foundation from which to know and respect other people, let alone to create change within ourselves.

Developing all four of these gifts is vital to proactivity. You cannot neglect one of them because the key is in the synergy or the relationship among them. Hitler, for example, had tremendous self-awareness, imagination, and willpower—but no conscience. And it proved to be his undoing. It also changed the course of the world in many tragic ways. Others are very principled and conscience driven, but they have no imagination, no vision. They are good—but good for what? Toward what end? Others have great willpower but no vision. They often do the same things again and again with no meaningful end in mind.

And this applies to an entire family as well. The collective sense of these four gifts—the relationship among these gifts as well as the relationship among the individuals in the family—is what enables the family to move to higher and higher levels of achievement and significance and contribution. The key lies in the proper nurturance of all four gifts in the individual and in the family culture so that there is a great sense of self- and family awareness, a highly cultivated and sensitive individual and collective conscience, the development of the creative, imaginative instincts into shared vision, and the development and use of a strong personal and social will to do whatever it takes to fulfill a mission, to achieve a vision, to matter.

The Circle of Influence and the Circle of Concern

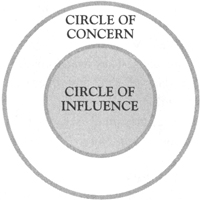

The essence of proactivity and the use of these four unique gifts lies in taking the responsibility and the initiative to focus on the things in our lives we can actually do something about. As Saint Francis wrote in his well-known “Serenity Prayer”: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”4

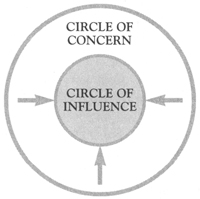

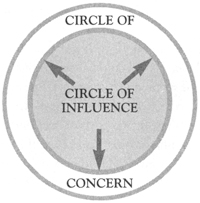

One way to make this differentiation more clear in our minds is to look at our lives in terms of what I call the Circle of Influence and the Circle of Concern. The Circle of Concern is a large circle that embraces everything in your life that you may be concerned about. The Circle of Influence is a smaller circle within the Circle of Concern that embraces the things you can actually do something about.

The reactive tendency is to focus on the Circle of Concern, but this only causes the inner Circle of Influence to be diminished. The nature of energy focused on the outer Circle of Concern is negative. And when you combine that negative energy with neglect of the Circle of Influence, inevitably the Circle of Influence gets smaller.

But proactive people focus on their Circle of Influence. As a result, that circle increases.

Consider the impact of one man’s decision to work in his Circle of Influence:

In my later teens I noticed that Mom and Dad were becoming very critical of each other. There were arguments and tears. They would say things that hurt—and they knew what to say. There was also making up and “everything’s fine.” But over time the arguments increased and the hurt got deeper.

When I was about twenty-one, they finally separated. I remember at the time feeling a great sense of duty and a desire to help “fix it.” I guess that’s a natural response for a child. You love your parents. You want to do everything you can.

I would say to my dad, “Why don’t you just go to Mom and say ‘I’m sorry. I know I’ve done lots of things that hurt you, but please forgive me. Let’s work at this. I’m committed to it.’” And he would say, “I can’t. I’m not going to bare my soul like that and have it stomped on again.”

I would say to my mom, “Look at everything you’ve had together. Isn’t it worth trying to save?” And she would say, “I can’t do it. I simply cannot handle this man.”

There was deep unhappiness, deep anguish, deep anger on both sides. And both Mom and Dad went to unbelievable effort to get us children to see that their side was right and the other was wrong.

When I finally realized they were going to divorce, I couldn’t believe it. I felt so empty and sad inside. Sometimes I would just weep. One of the most solid things in my life was gone. And I became consumed with self-focus. Why me? Why can’t I do something to help?

I had a very good friend who finally said to me, “You know what you need to do? You need to stop feeling sorry for yourself. Just look at you. This is not your problem. You are connected to it, but this is your parents’ problem, not yours. You need to stop feeling sorry for yourself and figure out what you can do to support and love each of your parents, because they need you more than they have ever needed you before.”

When my friend said that to me, something happened inside. I suddenly realized that I was not the victim here. My inner voice said, “Your greatest responsibility as a son is to love each of your parents and to chart your own course. You need to choose your response to what has happened here.”

That was a profound moment in my life. It was a moment of choice. It was realizing that I was not a victim and that I could do something about it.

So I focused on loving and supporting both my parents, and I refused to take sides. My parents did not like it. They accused me of being neutral, wimpy, not being willing to take a stand. But they both came to respect my position over time.

As I thought about my own life, it was suddenly as if I could step aside from myself, my family experience, their marriage, and become a learner. I knew that someday I wanted to be married and have a family. So I asked myself, “What does this mean to you, Brent? What are you going to learn from this? What kind of marriage are you going to build? Which of your weaknesses that you happen to share with your parents are you going to give up?”

I decided that what I really wanted was a strong, healthy, growing marriage. And I have since found that when you have that kind of resolve, it gives you the sustaining power to swallow hard in difficult moments—to not say something that will hurt feelings, to apologize, to come back to it, because you are affirming something that is more important to you than just the emotion of the moment.

I also made the resolve to always remember that it’s more important to be “one” than to be right or have it your way. The tiny victory that comes from winning the argument only causes greater separation, which really deprives you of the deeper satisfaction of a marriage relationship. I count that as one of my greatest life learnings. And from that I determined that when I faced a situation where I wanted something different from what my wife wanted and I did something dumb that put a wall between us (which, even at that time, I realized I would do on a regular basis), I would not live with it or let it expand but would always apologize. I would always say, “I’m sorry,” and reaffirm my love and commitment to her and work it out. I determined to always do everything in my power, not to be perfect—because I knew that was impossible— but to keep working at it, to keep trying.

It hasn’t been easy. Sometimes it takes a lot of effort when there are deep issues. But I believe my resolve reflects a priority that might never have been there had I not gone through the painful experience of my parents’ divorce.

Think about this man’s experience. Here were the two people he loved most in the world—the people from whom he had gotten much of his own sense of identity and security over the years—and their marriage was falling apart. He felt betrayed. His own sense of security was put in jeopardy. His vision, his feelings about marriage were threatened. He was in deep pain. He later said it was the most difficult, the most challenging time in his life.

Through the help of a friend he realized that their marriage was in his Circle of Concern but not in his Circle of Influence. He decided to be proactive. He realized he couldn’t fix their marriage, but there were things he could do. And his inner compass told him what those things were. So he began to focus on his Circle of Influence. He worked on loving and supporting both parents—even when it was hard, even when they reacted in negative ways. He gained the courage to act based on principle rather than reacting to his parents’ emotional response.

He also started to think about his own future, his own marriage. He began to recognize values he wanted to have in his relationship with his future wife. As a result, he was able to begin his marriage with the vision of that relationship in mind. And the power of that vision has carried him through the challenges to it. It’s given him the power to apologize and to keep coming back.

Can you see what a difference a Circle of Influence focus makes?

Consider another example. I’m aware of one set of parents who decided that the behavior of their daughter had deteriorated to the point where allowing her to continue to live at home would destroy the family. The father determined that when she got home that night, he would tell her that she had to do certain things or move out the next day. So he sat down to wait for her. While he was waiting, he decided to take a three-by-five card and list the changes she had to make in order to stay. When he finished the list, he had feelings that only those who have suffered a similar situation can know.

But in this emotionally pained spirit, as he continued to wait for her to come home, he turned the card over. The other side was blank. He decided to list on that side of the card the improvements he would agree to make if she would agree to her changes. He was in tears as he realized that his list was longer than hers. In that spirit he humbly greeted her when she came home, and they began a long, meaningful talk, beginning with his side of the card. His choice to begin with that side made all the difference—inside out.

Now just think about the word “responsible”—“response-able,” able to choose your own response. That is the essence of proactivity. It is something we can do in our own lives. The interesting thing is that when you focus on your Circle of Influence and it gets larger, you are also modeling to others through your example. And they will tend to focus on their inner circle also. Sometimes others may do the opposite out of reactive anger, but if you’re sincere and persistent, your example can eventually impact the spirit of everyone so that they will become proactive and take more initiative, more “response-ability” in the family culture.

Listen to Your Language

One of the best ways to tell whether you’re in your Circle of Influence or Circle of Concern is to listen to your own language. If you’re in your Circle of Concern, your language will be blaming, accusing, reactive.

“I can’t believe the way these kids are behaving! They’re driving me crazy!”

“My spouse is so inconsiderate!”

“Why did my father have to be an alcoholic?”

If you’re in your Circle of Influence, your language will be proactive. It will reflect a focus on the things you can do something about.

“I can help create rules in our family that will enable the children to learn about the consequences of their behavior. I can look for opportunities to teach and reinforce positive behavior.”

“I can be considerate. I can model the kind of loving interaction I would like to see in my marriage.”

“I can learn more about my father and his addiction to alcohol. I can seek to understand him, to love and to forgive. I can choose a different path for myself, and I can teach and influence my family so that this will not be part of their lives.”

In order to get a deeper insight into your own level of proactivity or reactivity, you might like to try the following experiment. You may want to ask your spouse or someone else to participate with you and give you feedback.

1. Identify a problem in your family culture.

2. Describe it to someone else (or write your description down), using completely reactive terms. Focus on your Circle of Concern. Work hard. See how completely you can convince someone else that this problem is not your fault.

3. Describe the same problem in completely proactive terms. Focus on your response-ability. Talk about what you can do in your Circle of Influence. Convince someone else that you can make a real difference in this situation.

4. Now think about the difference in the two descriptions. Which one more closely resembles your normal habit pattern when talking about family problems?

If you find that you are using essentially reactive language, you can take immediate steps to replace that kind of language with proactive words and phrases. The very act of forcing yourself to use the words will help you recognize habits of reactivity and begin to change.

Teaching responsibility for language is another way we can help even young children learn to integrate Habit 1.

Colleen (our daughter):

Recently, I tried to help our three-year-old be more responsible for her language. I said to her, “In our family we don’t say hate or shut up or call people stupid. You have to be careful about the way you talk to people. You need to be responsible.” Every now and then I would remind her, “Don’t call people names, Erika. Try to be responsible for the way you talk and act.”

Then the other day I happened to remark, “Oh, I hated that movie!” Erika immediately replied, “Don’t say hate, Mom! You’re responsible.”

Erika is now like the Gestapo in our family. We all have to watch our language when we’re around her.

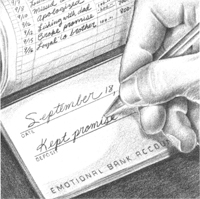

Building the Emotional Bank Account

One very practical, useful way to understand and apply this whole idea of proactivity and this inside-out approach of focusing on the Circle of Influence is by using the analogy or metaphor of the Emotional Bank Account.

The Emotional Bank Account represents the quality of the relationship you have with others. It’s like a financial bank account in that you can make “deposits,” by proactively doing things that build trust in the relationship, or you can make “withdrawals,” by reactively doing things that decrease the level of trust. And at any given time the balance of trust in the account determines how well you can communicate and solve problems with another person.

If you have a high balance in your Emotional Bank Account with a family member, then there’s a high level of trust. Communication is open and free. You can even make a mistake in the relationship, and the “emotional reserves” will compensate for it.

But if the account balance is low or even overdrawn, then there’s no trust and thus no authentic communication. It’s like walking on minefields. You’re always on your guard. You have to measure every word. And even your better intentions are misunderstood.

Remember the story of my friend who “found his son again.” You could say that the relationship between this father and son was $100, $200, or even $10,000 overdrawn. There was no trust, no real communication, no ability to work together to solve problems. And the harder this father pushed, the worse it got. But then my friend did something proactive that made a tremendous difference. Taking an inside-out approach, he became an agent of change. He stopped reacting to his son. He made an enormous deposit in this boy’s Emotional Bank Account. He listened, really, deeply listened. And the boy suddenly felt validated, affirmed, recognized as an important human being.

You can choose to make deposits instead of withdrawals. No matter what the situation, there are always things you can do that will make relationships better.

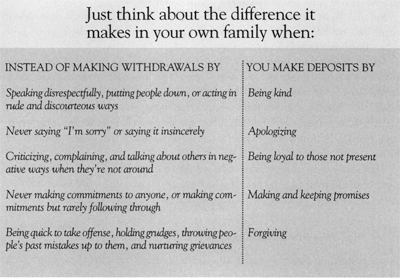

One of the biggest problems in many family cultures is the reactive tendency to continually make withdrawals instead of deposits. Consider on the following page what my friend Dr. Glen C. Griffin suggests is a typical day in the life of a teenager.

What kind of impact will this kind of communication—day in and day out—have on the balance in the Emotional Bank Account?

Remember, love is a verb. One of the great benefits of being proactive is that you can choose to make deposits instead of withdrawals. No matter what the situation, there are always things you can do that will make relationships better.

A Day’s Input To A Teen

6:55 A.M. |

|

Get up or you’ll be late again. |

7:14 A.M. |

|

But you’ve got to eat breakfast. |

7:16 A.M. |

|

You look like something on punk video. Put on something decent. |

7:18 A.M. |

|

Don’t forget to take out the garbage. |

7:23 A.M. |

|

Put on your coat. Don’t you know it’s cold outside? You can’t walk to school in weather like this. |

7:25 A.M. |

|

I expect you to come straight home from school and get your homework done before going off anywhere. |

5:42 P.M. |

|

You forgot the garbage. Thanks to you we’ll have garbage up to our ears for another week. |

5:46 P.M. |

|

Put this darn skateboard away. Someone’s going to trip over it and break his neck. |

5:55 P.M. |

|

Come to dinner. Why do I always have to look for you when it’s time to eat? You should have been helping to set the table. |

6:02 P.M. |

|

How many times do I have to tell you dinner is ready? |

6:12 P.M. |

|

Do you have to come to the table with earphones on your head, plugged into that rotten noise you call music? Can you hear what I’m saying? Take those things out of your ears. |

6:16 P.M. |

|

Things are going to have to shape up around here. Your room is a disgrace, and you’re going to have to start carrying your load. This isn’t a palace with servants to wait on you. |

6:36 P.M. |

|

Turn off that video game and unload the dishwasher and then put the dirty dishes in it. When I was your age, we didn’t have dishwashers. We had to wash dishes in hot soapy water. |

7:08 P.M. |

|

What are you watching? It doesn’t look very good to me, and it’s dumb to think you can do homework better with the TV going. |

7:32 P.M. |

|

I told you to turn off the TV until your homework is finished. And why are those shoes and candy wrappers in the middle of the floor? I’ve told you a million times it’s easier to put things away right then rather than later. Do you like to hear me yell? |

9:59 P.M. |

|

That stereo is so loud I can’t hear myself think. Go to sleep or you’ll be late again tomorrow.5 |

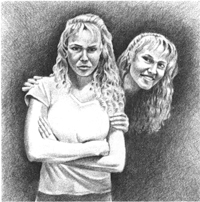

One father from a blended family shared this experience:

I have always considered myself to be an honest, hardworking man. I was successful at work and in my relationships with my wife and children—with the exception of our fifteen-year-old daughter Tara.

I had made several futile attempts to mend my broken relationship with her, but every attempt had ended in a frustrating failure. She just didn’t trust me. And whenever I tried to resolve our differences, I seemed to make things worse.

Then I learned about the Emotional Bank Account, and I came across a question that really hit me hard: “Ask yourself, are those around you made happier or better by your presence in the home?”

In my heart I had to answer, “No. My presence is making things worse for my daughter Tara.”

That introspection almost broke my heart.

After the initial shock I came to the realization that if this sad truth were to change, it would only be because I changed myself, because I changed my own heart. I not only had to act differently toward her; I needed to commit to truly loving her. I had to quit criticizing and always blaming her, to quit thinking that she was the source of our poor relationship. I had to quit competing with her by always making my will supersede hers.

I knew that unless I acted on these feelings immediately, I would probably never act on them, so I resolved to do so. I made a commitment that for thirty days I would make five deposits daily into my Emotional Bank Account with Tara—and absolutely no withdrawals.

My first impulse was to go to my daughter and tell her what I had learned, but my better judgment told me that the time was not right for teaching with words. It was time to begin making deposits. Later that day, when Tara came home from school, I greeted her with a warm smile and asked, “How are you?” Her curt reply was “A lot you care.” I swallowed hard and tried to act as if I’d not heard it. I smiled and replied, “I just wondered how you were doing.’”

During the next several days I worked hard to keep my commitment. I put reminder “stickies” everywhere, including on the rearview mirror of my car. I continued to dodge her frequent barbs, which was not easy for me because I had been conditioned to fight back. Each experience caused me to see just how cynical our relationship had become. I began to realize how often in the past I had expected her to change before I would do anything myself to make things better.

As I focused on changing my own feelings and actions rather than hers, I began to see Tara in an entirely new light. I began to appreciate her great need to be loved. And as I continued to let the negative blows glance off, I felt an increasing strength to do so without any inner resentment, but with increased love.

Almost without effort I found myself beginning to do little things for her—little favors that I knew I did not have to do. While she studied, I would quietly walk in and turn up the light. When she asked, “What’s this all about?,” I’d reply, “I just thought you could read better with more light.”

Finally, after about two weeks, Tara looked at me quizzically and asked, “Dad, there’s something different about you. What’s happening? What’s going on?”

I said, “I’ve come to recognize some things about myself that need changing, that’s all. I’m so grateful that now I can express my love to you by treating you the way I know I should have treated you all along.”

We began to spend more time together at home, just talking and listening to each other. More than two months have gone by now, and our relationship has been much, much deeper and more positive. It’s not flawless yet, but we’re getting there. The pain is gone. The trust and love increase each day, and it’s due to the simple yet profound idea of making only deposits and no withdrawals in the Emotional Bank Account—and doing it consistently and sincerely. As you do you will begin to see the person differently and begin to replace self-serving motives with service motives.

I am certain that if you ask my daughter what she thinks of me now, she would quickly reply, “My dad? We’re friends. I trust him.”

You can see how this father used proactivity to make a real difference in his relationship with his daughter. Notice how he used all four human gifts. Look at how self-aware he was. Look at how he could stand apart from himself, from his daughter, from the whole situation and see what was happening. Notice how he could compare what was happening with what his conscience was telling him was right. Notice how he had a sense of what was possible. Through his imagination he could envision something different. And notice how he used his willpower to act.

And as he used all four gifts, look at what began to happen. Things began to improve dramatically—not only the quality of the relationship but also how he felt about himself and how his daughter felt about herself. It was like flooding a toxic culture with a healing balm. That’s literally what he did. He made many deposits because he got his head out of the weaknesses of other people and focused on his own Circle of Influence—on those things he could do something about. He was truly an agent of change.

Just remember, every time you build your emotional life on the weaknesses of others, you give your power—that is, your unique human gifts—away to their weaknesses so that your emotional life is a product of how they treat you. You disempower yourself and empower the weaknesses of others.

But when you focus on your Circle of Influence and on doing what you can to build the Emotional Bank Account—to build relationships of trust and unconditional love—you dramatically increase your ability to influence others in positive ways.

Let me share with you some specific ideas—some “deposits” you can make in your own family—that may be helpful. These are practical ways that you can begin to practice Habit 1 in your family now.

Being Kind

Some years ago I spent a special evening with two of my sons. It was an organized father and sons outing, complete with gymnastics, wrestling matches, hotdogs, orangeade, and a movie—the works.

In the middle of the movie, Sean, who was then four years old, fell asleep in his seat. His older brother, Stephen, who was six, stayed awake, and we watched the rest of the movie together. When it was over, I picked Sean up in my arms, carried him out to the car, and laid him in the backseat. It was very cold that night, so I took off my coat and gently arranged it over and around him.

When we arrived home, I quickly carried Sean in and tucked him into bed. After Stephen put on his pajamas and brushed his teeth, I lay down next to him to talk about the night out together.

“How’d you like it, Stephen?”

“Fine,” he answered.

“Did you have fun?”

“Yes.”

“What did you like most?”

“I don’t know. The trampoline, I guess.”

“That was quite a thing, wasn’t it? Doing those somersaults and tricks in the air like that?”

There wasn’t much response on his part. I found myself making conversation. I wondered why Stephen wouldn’t open up more. He usually did when exciting things happened. I was a little disappointed. I sensed something was wrong; he had been so quiet on the way home and getting ready for bed.

Suddenly Stephen turned over on his side to face the wall. I wondered why and lifted myself up just enough to see his eyes welling up with tears.

“What’s wrong, honey? What is it?”

He turned back, and I could sense he was feeling some embarrassment for the tears and his quivering lips and chin.

“Daddy, if I were cold, would you put your coat around me, too?”

Of all the events of that special night out together, the most important was a little act of kindness—a momentary, unconscious showing of love to his little brother. What a powerful, personal lesson that was to me of the importance of kindness!

In relationships the little things are the big things. One woman told of growing up in a home where there was a plaque on the kitchen wall that read: “To do carefully and constantly and kindly many little things is not a little thing.”

Cynthia (daughter):

One thing that stands out in my mind about being a teenager is the feeling of being overwhelmed. I remember the pressure of trying to do well in school and being on the debate team and involved in three or four other things all at the same time.

And sometimes I’d come home and I’d find my whole room clean and organized. There would be a note that said, “Love, the Good Fairy,” and I knew Mom had just worked her head off to help me get ahead because I was so overwhelmed with what I had to do.

It really took a load off. I would come into that room and just whisper, “Oh, thank you. Thank you!”

Little kindnesses go a long way toward building relationships of trust and unconditional love. Just think about the impact in your own family of using words or phrases such as thank you, please, excuse me, you go first, and may I help you. Or performing unexpected acts of service such as helping with the dishes, taking children shopping for something that’s important to them, or phoning to see if there’s anything you can pick up at the store on the way home. Or finding little ways to express love, such as sending flowers, tucking a note in a lunch box or briefcase, or phoning to say “I love you” in the middle of the day. Or expressing gratitude and appreciation. Or giving sincere compliments. Or showing recognition—not just at times of special achievement or on occasions such as birthdays but on ordinary days, and just because your spouse or your children are who they are.

“To do carefully and constantly and kindly many little things is not a little thing.”

Twelve hugs a day—that’s what people need. Hugs come physically, verbally, visually, environmentally. We all need twelve hugs a day—different forms of emotional nourishment from other people or perhaps spiritual nourishment through meditation or prayer.

I know of one woman who grew up in poverty and contention, but came to realize how important such kindness and courtesy are in the home. She learned it where she worked—at a very prestigious hotel where the entire staff had a culture of courtesy toward every guest. She knew how good it made people feel to be treated so royally. She also realized how good it made her feel to perform acts of kindness and courtesy. One day she decided to try acting this way at home with her own family. She began doing little acts of service for family members. She began using language that was positive, gentle, and kind. When serving breakfast, for example, she would say, as she did at work, “It’s my pleasure!” She told me it transformed both her and her family and began a new intergenerational cycle.

One thing my brother John and his wife, Jane, do in their family is take time every morning to compliment one another. Family members take turns being the target for such compliments. And what a difference that makes!

One morning their strong, athletic son—the football hero of the high school—came bounding down the stairs with such energy, such excitement that Jane couldn’t imagine why he was so animated.

“Why are you so excited?” she asked.

“It’s my morning for compliments!” he replied with a smile.

One of the most important dimensions of kindness is expressing appreciation. What an important deposit to make—and to teach—in the family!

Apologizing

Perhaps there is nothing that tests our proactive capacity as much as saying “I’m sorry” to another person. If your security is based on your image or your position or on being right, to apologize is like draining all the juice from your ego. It wipes you out. It pushes every one of your human gifts to its limit.

Colleen (daughter):

Several years ago Matt and I went up to the cabin to be with the whole family for Christmas. I don’t remember the details, but for some reason I was supposed to drive Mom to Salt Lake City the next day. As it happened, I already had another obligation and couldn’t do it. When Dad heard my response, he just exploded—totally lost it.

“You’re being selfish!” he said. “You really need to do this!” And he said a lot of other things he didn’t mean.

Surprised by his abrasive response, I started crying. I was deeply hurt. I was so used to his being understanding and considerate all the time. In fact, in my whole life I can remember only about two times that he really lost his temper with me, so it took me aback. I shouldn’t have taken offense, but I did. Finally, I said, “Okay, I’ll do it,” knowing he wouldn’t listen to my conflict.

I headed home, and my husband came with me. “We’re not going back tonight,” I said. “I don’t even care if we miss the family Christmas party!” And all the way down the canyon I was harboring bad feelings.

Shortly after we got home, the phone rang. Matt answered it. He said, “It’s your dad.”

“I don’t want to talk to him,” I said, still hurt. But I really did, so I finally picked up the phone.

“Darling,” he said, “I apologize. There’s really no excuse that could justify my losing my temper with you, but let me tell you what’s been going on.” He told me that they had just started building the house, finances had been swelling up, things at the business were kind of shaky, and then with Christmas and the whole family there, he had felt so much pressure he blew up and I received the brunt of it. “I just took it all out on you,” he said. “I’m so sorry. I apologize.” I then returned the apology, knowing I had overreacted.

Dad’s apology was a big deposit in my Emotional Bank Account. And we had had a great relationship to begin with.

Matt and I went back up that night, I rearranged my schedule for the next day, took my mom to Salt Lake City, and it was as if nothing had happened. If anything, my dad and I grew closer because he could apologize immediately. I think it took a lot for him to be able to step back from the situation so quickly and say “I’m sorry.”

Even though our temper may surface only one-hundredth of 1 percent of the time, it will affect the quality of all the rest of the time if we do not take responsibility for it and apologize. Why? Because people never know when they might hit our raw nerve, so they’re always inwardly worried about it and defending themselves against it by second-guessing our behavior and curbing their own natural, spontaneous, intuitive responses.

The sooner we learn to apologize, the better. World traditions affirm this idea. The Far Eastern expression is so apt here: “If you’re going to bow, bow low.” A great lesson is also taught in the Bible about paying the uttermost farthing.

Agree with thine adversary quickly, whiles thou art in the way with him; lest at any time the adversary deliver thee to the judge, and the judge deliver thee to the officer, and thou be cast into prison. Verily I say unto thee, Thou shalt by no means come out thence, till thou hast paid the uttermost farthing.

There are undoubtedly a number of ways to apply this instruction in our lives, but one may be this: Whenever we disagree with others, we need to quickly “agree” with them—not on the issue of disagreement (that would compromise our integrity) but on the right to disagree, to see it the way they see it. Otherwise, to protect themselves they will put us into a mental/emotional “prison” in their own mind. And we won’t be released from this prison until we pay the uttermost farthing—until we humbly and fully acknowledge our mistake in not allowing them the right to disagree. And we must do this without in any way saying, “I’ll say I’m sorry if you’ll say you’re sorry.”

If you attempt to pay the uttermost farthing by merely trying to be better and not apologizing, other people may still be suspicious and keep you behind these prison bars, behind the mental and emotional labels they have put on you that give them some feeling of security in knowing not to expect much from you.

We all “blow it” from time to time. In other words, we get off track. And when we do, we need to own up to it, humbly acknowledge it, and sincerely apologize.

Honey, I’m so sorry I embarrassed you in front of your friends. That was wrong of me. I’m going to apologize to you and also to your friends. I should never have done that. I got on some kind of an ego trip with you, and I’m sorry. I hope you will give me another chance.

Sweetheart, I apologize for cutting you off that way. You were trying to share something with me that you feel deeply about, and I got so caught up in my own agenda that I just came on like a steamroller. Will you please forgive me?

Notice again in these apologies how all four gifts are being used. First, you’re aware of what’s happening. Second, you consult your conscience and tap into your moral or ethical sense. Third, you have a sense of what is possible—what would be better. And fourth, you act on the other three. If any one of these four is neglected, the entire effort will break down, and you will end up trying to defend, justify, explain, or cover up the offensive behavior in some way. You may apologize, but it’s superficial, it’s not sincere.

Being Loyal to Those Not Present

What happens when family members are not loyal to one another, when they criticize and gossip about the others behind their backs? What does it do to the relationship, to the culture when family members make disloyal comments to other family members or to their friends:

“My husband is such a tightwad! He worries about every penny we spend.”

“My wife jabbers constantly. You’d think she could shut up and let me get a word in once in a while.”

“Did you hear what my son did the other day? He talked back to a teacher. They called me from the school. It was so embarrassing! I don’t know what to do with that kid. He’s always causing trouble.”

“I can’t believe my mother-in-law! She tries to control everything we do. I don’t know why my wife can’t just cut the apron strings and get it over with.”

Comments like these are huge withdrawals not only from the person spoken about but also from the person spoken to. For example, if you were to discover that someone had made one of these comments about you, how would it make you feel? You’d probably feel misunderstood, violated, unjustly criticized, unfairly accused. How would it affect the amount of trust in your relationship with that person? Would you feel safe? Would you feel affirmed? Would you feel you could confide in that person and your confidence would be treated with respect?

On the other hand, if someone said something like this to you about someone else, how would you feel? You might initially be pleased that the person had “confided” in you, but wouldn’t you begin to wonder if that same person, in a different circumstance, might say something equally negative about you to someone else?

Next to apologizing, the toughest and one of the most important deposits an individual can make—or an entire family can adopt as a fundamental value and commitment—is to be loyal to family members when they are not present. In other words, talk about others as if they were present. That doesn’t mean you are unaware of their weaknesses and are Pollyannaish and take the “ostrich head in the sand” approach. It means, rather, that you usually focus on the positive rather than the negative—and if you do talk about those weaknesses, you do it in such a responsible and constructive way that you would not be ashamed to have those people you’re talking about overhear your conversation.

Always talk about others as if they were present.

A friend of ours had an eighteen-year-old son whose habits irritated his married brother and sisters and their spouses. When he wasn’t there (which was often, since he spent most hours away from home with friends), the family would talk about him. Their favorite conversation centered on his girlfriends, his habit of sleeping late, and his demands on his mother to serve him at his beck and call. This man participated in these rather gossipy conversations about his son, and the discussions caused him to believe that his son was truly irresponsible.

At one point this friend became aware of what was happening and the part he was playing in it. He decided to follow the principle of being loyal to those not present by being loyal to his son. Thereafter, when such conversations began to develop, he would gently interrupt any negative comments and say something good that he had observed his son doing. He had a good story to counteract any derogatory comments the others might make. Soon the conversation would lose its spice and shift to other, more interesting subjects.

Our friend said he soon felt that the others in the family began to connect with this principle of family loyalty. They began to realize that he would also defend them if they were not present. And in some almost unexplainable manner—perhaps because he began to see his son differently—this change also improved his Emotional Bank Account with this son, who hadn’t even been aware of the family conversations about him. Bottom line: The way you treat any relationship in the family will eventually affect every relationship in the family.

I remember one time when I was running out of the house to go somewhere in a hurry. I knew that if I stopped to say good-bye to my three-year-old son Joshua, I would get caught up in his needs and questions. It would take time, and I was into efficiency. So I said to my other children, “See ya, kids. I’ve got to run! Don’t tell Joshua I’m going.”

I got halfway out to the car before I realized what I had just done. I turned around, went back into the house, and said to the other children, “That was wrong of me to run out on Joshua like that and not to say good-bye to him as well. I’m going to find him to say good-bye.”

The way you treat any relationship in the family will eventually affect every relationship in the family.

Sure enough, I had to spend some time with him. I had to talk with him about what he wanted to talk about before I could go. But it built the Emotional Bank Account with Joshua and with the other children as well.

I sometimes think: What would have happened if I hadn’t gone back? What if I had gone to Joshua that night and tried to have a good relationship with him? Would he have been loving and open with me if he knew I had run out on him when he wanted and needed me? How would this have affected my relationship with my other sons and daughters? Would they have thought that I would run out on them, too, if interacting with them sidetracked my agenda?

The message sent to one is truly sent to all because everyone is a “one,” and they know that if you treat one that way, all it takes is a change of circumstances and you’ll treat them that way, too. That’s why it is so important to be loyal to those not present.

Notice here, too, how all four gifts are in proactive use. To be loyal, you have to be self-aware. You have to have a sense of conscience, a moral sense of right and wrong. You have to have a sense of what’s possible, what’s better. And you have to have the intestinal fortitude to make it happen.

Being loyal to those not present is clearly a proactive choice.

Making and Keeping Promises

Many times over the years people have asked if I had one idea that would best help people grow so that they could better cope with their problems, seize their opportunities, and make their life successful. I’ve come to give a simple four-word answer: “Make and keep promises.”

Although this may sound like an oversimplification, I truly believe it is profound. In fact, as you will discover, all of the first three habits are embodied in that simple four-word expression. If an entire family would cultivate the spirit of making and keeping promises to one another, it would create a multitude of other good things.

Cynthia (daughter):

When I was twelve years old, Dad promised to take me with him on a business trip to San Francisco. I was so excited! We talked about the trip for three months. We were going to be there for two days and one night, and we planned every detail. Dad was going to be busy in meetings the first day, so I would hang around the hotel. After his meetings, we planned to take a cab to Chinatown and have our favorite Chinese food. Then we’d see a movie, take a ride on a trolley car, and go back to our hotel room for a video and hot fudge sundaes from room service. I was dying with anticipation.

The day finally arrived. The hours dragged by as I waited at the hotel. Six o’clock came, but Dad didn’t. Finally, at 6:30, he arrived with another man—a dear friend and an influential business acquaintance. I remember how my heart sank as this man said, “I’m so excited to have you here, Stephen. Tonight, Lois and I would like to take you to the wharf for a spectacular seafood dinner, and then you must see the view from our house.” When Dad told him I was there, this man said, “Of course, she can come, too. We’d love having her.”

Oh, great! I thought. I hate fish, and I’ll be stuck alone in the backseat while Dad and his friend talk. I could see all my hopes and plans going down the drain.

My disappointment was bigger than life. This man was pressing so hard. I wanted to say, “Dad, this is our time together! You promised!” But I was twelve years old, so I only cried inside.

I will never forget the feeling I had when Dad said, “Gosh, Bill, I’d love to see you both, but this is a special time with my girl. We’ve already got it planned to the minute. You were kind to invite us.” I could tell this man was disappointed, but—amazingly to me—he seemed to understand.

We did absolutely everything we had planned on that trip. We didn’t miss a thing. That was just about the happiest time of my life. I don’t think any young girl ever loved her father as much as I loved mine that night.

I’m convinced you would be hard-pressed to come up with a deposit that has more impact in the family than making and keeping promises. Just think about it! How much excitement, anticipation, and hope is created by a promise? And the promises we make in the family are the most vital and often the most tender promises of all.

The most foundational promise we ever make to another human being is the vow inside a marriage. It’s the ultimate promise. And equal to it is the promise we implicitly have with our children—particularly when they’re little—that we will take care of them, that we will nurture them. That’s why divorce and abandonment are such painful withdrawals. Those involved often feel as though the ultimate promises have been broken. So when these things have occurred, it becomes even more important to make deposits that will help rebuild bridges of confidence and trust.

At one time a man who had helped me on a particular project described the awful divorce he had just gone through. But he spoke with a kind of glowing pride about how he had kept the promise he had made to himself and his wife many months before that no matter what happened, he would not bad-mouth her—especially in front of his kids—and that he would always speak of her in ways that were affirming, uplifting, and positive. This was during the time when the legal and emotional battles were going on, and he said it was the hardest thing he had ever done. But he also said how grateful he was that he did it because it made all the difference—not only in how his children felt about themselves but also in how they felt about both their parents and their sense of family, despite the very difficult situation. He couldn’t say enough about how glad he was that he kept the promise he had made.

Even when promises have been broken in the past, you can sometimes turn the situation into a deposit. I remember a man once who didn’t come through on a commitment he had made to me. Later, he asked if he could have the opportunity to do something else, and I said no. Based on my past experience with him, I wasn’t sure he would follow through.

But that man said to me, “I didn’t come through before. I should have acknowledged it. I just gave a halfhearted effort, and that was wrong of me. Would you please give me one more opportunity? Not only will I come through, I will come through in gangbuster style.”

I agreed, and he did it. He came through in a remarkable way. And in my eyes, he rose even higher than if he had kept his first commitment. His courage in coming back, in dealing with a difficult problem and a mistake in an honorable way, made a massive deposit in my Emotional Bank Account.

Forgiving

For many people the ultimate test of the proactive muscle comes in forgiving. In fact, you will always be a victim until you forgive.

You will always be a victim until you forgive.

One woman shared this experience:

I came from a very united family. We were always together—children, parents, brothers, sisters, aunts, uncles, cousins, grandparents—and we dearly loved one another.

When my father followed my mother in death, it deeply saddened us all. The four of us children met to divide our parents’ things among us and our families. What happened at that meeting was an unforeseen shock from which we thought we would never recover. We had always been an emotional family, and at times we had disagreed to the point of some arguing and temporary ill will toward one another. But this time we argued beyond anything we had ever known before. The fight became so heated that we found ourselves yelling bitterly at one another. We began to emotionally tear at each other. Without being able to settle our differences, we each determined and announced that we were going to get lawyers to represent us and that the matter would be settled in court.

Each of us left that meeting feeling bitter and deeply resentful. We stopped visiting or even phoning one another. We stopped getting together on birthdays or holidays.

The situation went on for four years. It was the hardest trial of my life. Often, I felt the pain of loneliness and the unforgiving spirit of the bitterness and accusations that divided us. As my pain deepened, I kept thinking, If they really loved me, they would call me. What’s wrong with them? Why don’t they call?

Then one day I learned about the concept of the Emotional Bank Account. I came to realize that not forgiving my brothers and sisters was reactive on my part and that love is a verb, an action, something that I must do.

That night, as I was sitting alone in my room, the phone seemed to cry out to be used. I mustered all my courage and dialed the number of my oldest brother. When I heard his wonderful voice say, “Hello,” tears flooded my eyes, and I could scarcely speak.

When he learned who it was, his emotions matched mine. We each raced to be the first to say, “I’m sorry.” The conversation turned to expressions of love, forgiveness, and memories.

I called the others. It took most of the night. Each responded just as my oldest brother had.

That was the greatest and most significant night of my life. For the first time in four years I felt whole. The pain that had quietly been ever present was gone—replaced by the joy of forgiveness and peace. I felt renewed.

Notice how all four gifts came into play in this remarkable reconciliation. Look at this woman’s depth of awareness of what was happening. Observe this woman’s connection with her conscience, her moral sense. Also note how the concept of the Emotional Bank Account created a vision of what is possible and how these three gifts joined in producing the willpower to forgive and connect together again, and to experience the happiness that such an emotional reunion brings.