HABIT 3

PUT FIRST THINGS FIRST

Okay, now, I know what you’re going to hear from people is “We don’t have the time.” But if you don’t have the time for one night or at least one hour during the week where everybody can come together as a family, then the family is not the priority.

—Oprah Winfrey

In this chapter we’re going to take a look at two organizing structures that will help you prioritize your family in today’s turbulent world and turn your mission statement into your family’s constitution.

One of these structures is a weekly “family time.” And as television talk show host Oprah Winfrey told her audience when she talked with me about this book on her show, “If you don’t have the time for one night or at least one hour during the week where everybody can come together as a family, then the family is not the priority.”

The second structure is one-on-one bonding times with each member of your family. I suggest that these two structures create a powerful way to prioritize your family and keep “first things first” in your life.

When First Things Aren’t First

One of the worst feelings in the world is when you realize that the “first things” in your life—including your family—are getting pushed into second or third place, or even further down the list. And it becomes even worse when you realize what’s happening as a result.

I vividly remember the painful feeling I had one night as I went to bed in a hotel in Chicago. While I had been presenting that day, my fourteen-year-old daughter Colleen had had her final dress rehearsal for a play she was in—West Side Story. She had not been selected to play the lead but was the understudy. And I knew that for most of the performances—possibly all—she would not play the leading role.

But tonight was her night. Tonight she was going to be the star. I had called her to wish her well, but the feeling in my heart was one of deep regret. I really wanted to be there with Colleen. And, although this is not always the case, this time I could have arranged my schedule to be there. But somehow Colleen’s play had gotten lost in the press of work and other demands, and I simply didn’t have it on my calendar. As a result, here I was, alone, some thirteen hundred miles away, while my daughter sang and acted her heart out to an audience that didn’t include her dad.

I learned two things that night. One was that it doesn’t matter whether your child is in the leading role or in the chorus, is starting quarterback or third string. What matters is that you’re there for that child. And I was able to be there for several of the actual performances where Colleen was in the chorus. I affirmed her. I praised her. And I know she was glad I had come.

But the second thing I learned is that if you really want to prioritize your family, you simply have to plan ahead and be strong. It’s not enough to say your family is important. If “family” is really going to be top priority, you have to “hunker down, suck it up, and make it happen!”

“Things which matter most must never be at the mercy of things which matter least.”

The other night after the ten o’clock news there was an advertisement on television that I have often seen. It shows a little girl approaching her father’s desk. He’s hassled, has papers scattered all over, and is diligently writing in his planner. She stands by him—unnoticed until she finally says, “Daddy, what are you doing?”

Without even looking up, he replies, “Oh, never mind, honey. I’m just doing some planning and organizing. These pages have the names of all the people I need to visit and talk with and all the important things I have to do.”

The little girl hesitates and then asks: “Am I in that book, Daddy?”

As Goethe said, “Things which matter most must never be at the mercy of things which matter least.” There is no way we can be successful in our families if we don’t prioritize “family” in our lives.

And this is what Habit 3 is about. In a sense, Habit 2 tells us what “first things” are. Habit 3, then, has to do with our discipline and commitment to live by those things. Habit 3 is the test of the depth of our commitment to “first things” and of our integrity—whether or not our lives are truly integrated around principles.

So Why Don’t We Put First Things First?

Most people clearly feel that family is top priority. Most would even put family above their own health, if it came to it. They would put family ahead of their own life. They would even die for their family. But when you ask them to really look at their lifestyle and where they give their time and their primary attention and focus, you almost always find that family gets subordinated to other values—work, friends, private hobbies.

In our surveys of over a quarter of a million people, Habit 3 is, of all the habits, the one where people consistently give themselves the lowest marks. Most people feel there’s a real gap between what really matters most to them—including family—and the way they live their daily lives.

Why is this happening? What is the reason for the gap?

After one of my presentations I was visiting with a gentleman who said, “Stephen, I really don’t know if I’m happy with what I’ve done in my life. I don’t know if the price I’ve paid to get where I am has been worth it. I’m in line now for the presidency of my company, and I’m not sure I even want it. I’m in my late fifties, and could easily be the president for several years, but it would consume me. I know what it takes.

“What I missed most was the childhood of my kids. I just wasn’t there for them, and even when I was there, I wasn’t really ‘there.’ My mind and my heart were focused on other things. I tried to give quality time because I knew I didn’t have quantity, but often it was disorienting and confusing. I even tried to buy my kids off by giving them things and providing exciting experiences, but the real bonding never took place.

“And my kids feel the enormous loss themselves. It’s just as you talk about, Stephen—I have climbed the ladder of success, and as I’m getting near the top rung, I realize that the ladder is leaning against the wrong wall. I just don’t have this feeling in our family—this beautiful family culture you’ve been talking about. But I feel as if that’s where the riches are. It’s not in money; it’s not in positions. It’s in this family relationship.”

Then he began to open his briefcase. “Let me show you something,” he said as he pulled out a large piece of paper. “This is what excites me!” he exclaimed, spreading it out between us. It was a blueprint of a home he was building. He called it his “three-generation home.” It was designed to be a place where children and grandchildren could come and have fun and enjoy interacting with their cousins and other relatives. He was building it in Savannah, Georgia, right on the beach. As he went over the plans with me, he said, “What excites me most about this is the way it excites my kids. They also feel as though they lost their childhood with me. They miss that feeling, and they want and need it.

“In this three-generation home, we have a common project to work on together. And as we work on this project, we think about their children—my grandchildren. In a sense I am reaching my children through their children, and they love it. My children want my involvement with their children.”

As he rolled the paper up and put it back into his briefcase, he said, “This is so important to me, Stephen! If accepting this position means that we have to move or that I won’t have the time to really invest in my children and grandchildren, I’ve decided I’m not going to take it.”

Notice how, for many years, “family” was not this man’s most important priority. And he and his family lost many years of precious family experience because of it. But at this time in his life he had come to realize the importance of the family. In fact, family had become so important to him that it eclipsed even the presidency of a major international firm—the last rung on the ladder of “success.”

Clearly, putting family first doesn’t necessarily mean that you have to buy a new home or give up your job. But it does mean that you “walk your talk”—that your life really reflects and nurtures the supreme value of family.

In the midst of pressures—particularly regarding work and career—many people are blind to the real priority of family. But think about it: Your professional role is temporary. When you retire from being a salesman, banker, or designer, you will be replaced. The company will go on. And your life will change significantly as you move out of that culture and lose the immediate affirmation of your work and your talent.

In the end, life teaches us what is important, and that is family.

But your role in the family will never end. You will never be replaced. Your influence and the need for your influence never ends. Even after you are gone, your children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren will still look to you as their parent or grandparent. Family is one of the few permanent roles in life, perhaps the only truly permanent role.

So if you’re living your life around a temporary role and allowing your treasure chest to remain barren in terms of your only real permanent role, then you’re letting yourself be seduced by the culture and robbed of the true richness of your life—the deep and lasting satisfaction that only comes through family relationships.

In the end, life teaches us what is important, and that is family. Often for people on their deathbed, things not done in the family are a source of greatest regret. And hospice volunteers report that in many cases unresolved issues—particularly with family members—seem to keep people holding on, clinging to life until there is a resolution—an acknowledging, an apologizing, a forgiving—that brings peace and release.

So why don’t we get the message of the priority of family when we’re first attracted to someone, when our marriage is new, when our children are small? And why don’t we remember it when the inevitable challenges come?

For many of us, life is well described by Rabindranath Tagore when he said, “The song that I came to sing remains unsung. I have spent my days in stringing and unstringing my instrument.”1 We’re busy—incredibly busy. We’re going through the motions. But we never seem to reach the level of life where the music happens.

The Family: Sideshow or Main Tent?

The first reason we don’t put family first goes back to Habit 2. We’re not really connected to our deepest priorities. Remember the story about the businessmen and -women and their spouses in Habit 2 who had difficulty creating their family mission statements? Remember how they were unable to achieve the victory they wanted in their families until they really, deeply prioritized “family” in their own hearts and minds—inside out?

Many people have the feeling that family should be first. They may really want to put family first. But until that deep priority connection is there—and a commitment is made to it that is stronger than all the other forces that play on our everyday lives—we will not have what it takes to prioritize the family. Instead, we will be driven or enticed or derailed by other things.

In April 1997, U.S. News & World Report published a hard-hitting article entitled “Lies Parents Tell Themselves About Why They Work” that really challenged parents to do some serious soul searching and conscience work in this area. Authors Shannon Brownlee and Matthew Miller claim that few topics are as important—and involve as much self-deception and dishonesty—as finding the proper balance between child-rearing and work. They list five lies that parents tell themselves to rationalize (create rational lies) around their work-preference decisions. In summary, their findings were as follows:

Lie #1: We need the extra money. (But research shows that better-off Americans are nearly as likely to say they work for basic necessities as those who live near the poverty line.)

Lie #2: Day care is perfectly good. (“The most recent comprehensive study conducted by researchers at four universities found that while 15 percent of day care facilities were excellent, 70 percent were ‘barely adequate,’ and 15 percent were abysmal. Children in that vast middle category were physically safe but received scant or inconsistent emotional support and little intellectual stimulation.”)

Lie #3: Inflexible companies are the key problem. (The truth is that family-friendly policies now in place are usually ignored. Many people want to spend more time at the office. “Home life has become more like an efficiently run but joyless workplace, while the actual workplace, with its new emphasis on empowerment and teamwork, is more like a family.”)

Lie #4: Dads would gladly stay home if their wives earned more money. (In reality, few men ever seriously contemplate such a thing. “Men and women define ‘masculinity’ not in terms of athletic or sexual prowess but by the ability to be a ‘good provider’ for their families.”)

Lie #5: High taxes force both of us to work. (Even recent tax cuts have sent well-off spouses rushing into the job market.)

It’s easy to get addicted to the stimulation of the work environment and a certain standard of living, and to make all other lifestyle decisions based on the assumption that both parents have to work full-time. As a result, parents are held hostage by these lies—violating their conscience but feeling that they really have no choice.

The place to start is not with the assumption that work is non-negotiable; it’s with the assumption that family is non-negotiable. That one shift of mind-set opens the door to all kinds of creative possibilities.

The place to start is not with the assumption that work is non-negotiable; it’s with the assumption that family is non-negotiable. That one shift of mind-set opens the door to all kinds of creative possibilities.

In her bestselling book The Shelter of Each Other, psychologist Mary Pipher shares the story of a couple who were caught up in a hectic lifestyle.2 Both husband and wife worked long hours, trying to make ends meet. They felt they had no time for personal interests, for each other, or for their three-year-old twins. They anguished over the fact that it was day care providers who had seen their boys’ first steps and heard their first words, and that they were now reporting problems in behavior. This couple felt they had essentially fallen out of love, and the wife also felt torn apart by her unfulfilled desire to help her mother who was ill with cancer. They seemed trapped in what appeared to them to be an impossible situation.

But through counseling they were able to make some changes that created a dramatic difference in their lives. They began by setting aside Sunday nights to spend with their family and paying attention to each other—giving back rubs and expressing words of affection. The husband told his employers he would no longer be able to work on Saturdays. The wife eventually quit her job and stayed home with the boys. They asked her mother to move in with them, pooling their financial resources and providing a built-in storyteller for the boys. They cut back in many areas. The husband carpooled to work. They quit buying things except for essentials. They stopped eating out.

As Mary Pipher said, “The family had made some hard choices. They had realized that they could have more time or more money but not both. They had chosen time.”3 And that choice made a profound difference in the quality of their personal and family lives. They were happier, more fulfilled, less stressful, and more in love.

Of course, this may not be the solution for every family that’s feeling hassled and out of sync. But the point is that there are options, there are choices. You can consider cutting back, simplifying your lifestyle, changing jobs, shifting from full- to part-time work, cutting commuting time by having fewer, longer workdays or working closer to home, participating in job sharing, or creating a virtual office in your home. The bottom line is that there is no need to be held hostage by these lies if family is really your top priority. And making the family priority will push you into creative exploration of possible alternatives.

Parenthood: A Unique Role

There’s no question that more money can mean a better lifestyle not only for yourself but for your kids. They may be able to go to a finer school, have educational computer software, and even better health care. And recent studies also confirm that a child whose father or mother stays home and resents it is worse off than if the parents go to work.

But there’s also no question that the role of parents is a unique one, a sacred stewardship in life. It has to do with nurturing the potential of a special human being entrusted to their care. Is there really anything on any list of values that would outweigh the importance of fulfilling that stewardship well—socially, mentally, and spiritually, as well as economically?

The role of parents is a unique one, a sacred stewardship in life. Is there really anything that would outweigh the importance of fulfilling that stewardship well?

There is no substitute for the special relationship between a parent and a child. There are times when we would like to believe there is. When we choose to put a child in day care, for example, we want to believe it’s good, and so we do. If someone seems to have a positive attitude and a caring disposition, we easily believe they have both the character and the competence to help raise our child. But that which we desire most earnestly, we believe most easily. This is all part of the rationalization process. The reality is that most day care is inadequate. To paraphrase child development expert Urie Bronfenbrenner, “You can’t pay someone to do for a child what a parent will do for free.”4 Even excellent child care can never do what a good parent can do.

So parents need to make their commitment to their children—to their family—before they make their commitment to work. And if they do need day care assistance, they need to shop for that care far more carefully than they ever would for a house or a car. They need to examine the track record of the person being considered to ensure that both character and competence are present and the person can pass the “smell test”—the sense of intuition and inspiration that parents can get regarding caregiving for their children. They need to build a relationship with the caregiver so that correct expectations and accountability are established.

Good faith is absolutely insufficient. Good intentions will never replace bad judgment. Parents need to give trust, but they also need to verify competence. Many people are trustworthy in terms of character, but they are simply not competent—they lack knowledge and skill, and often are absolutely unaware of their incompetence. Others may be very competent but lack the character—the maturity and integrity, sincere caring, and the ability to be both kind and courageous.

And even with good care, the question each parent has to ask is “How often is such proxy caregiving right in my situation?” Sandra and I have some friends who have said that when their children were little, they felt they had all kinds of options and freedoms to do whatever they wanted. Their children were subject to them and dependent on them, and essentially they could have surrogate parenting in the form of day care and sitters whenever they wanted. So both parents became very involved in other things. But now, as their children are getting older, they are beginning to reap the whirlwind. They have no relationship. The children are getting into destructive lifestyles, and the parents have become greatly alarmed. “If we had it to do over,” they’ve said, “we would put a higher priority on our family, on these children—particularly when they were little. We would have made a greater investment.”

“If we had it to do over, we would put a higher priority on our family, on these children—particularly when they were little. We would have made a greater investment.”

As John Greenleaf Whittier wrote, “For of all sad words of tongue or pen, the saddest are these: ‘It might have been!’”5

On the other hand, we have another friend who said, “I’ve learned that for these years when I am raising these children, my other interests—professional interests, development interests, social interests—are to become secondary. My most important focus is to be there for my children, to invest myself in them at this critical stage.” She went on to say that this is difficult for her because she has so many interests and capabilities, but she is committed to it because she knows how vitally important it is.

What is the difference in these two situations? Priority and commitment—a clear sense of vision and the commitment to live with integrity to it. So if we’re not really prioritizing the family in daily life, the first place to look for answers is back in Habit 2: Is the mission statement really deep enough?

“When the Infrastructure Shifts, Everything Rumbles”

Assuming that we do have our Habit 2 work done, the next place we need to look is at the turbulent environment we’re trying to navigate through.

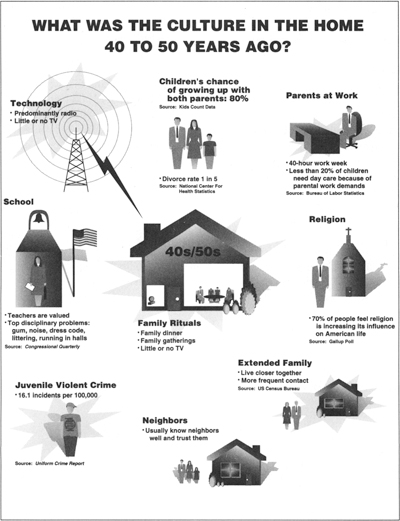

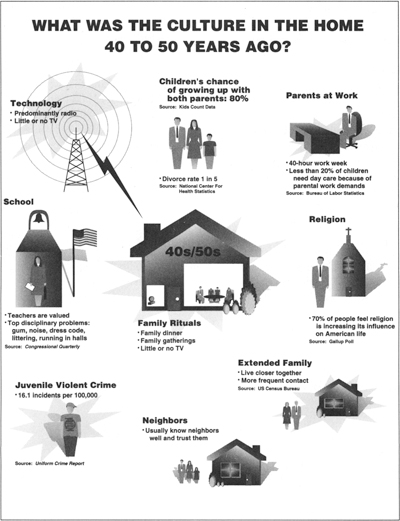

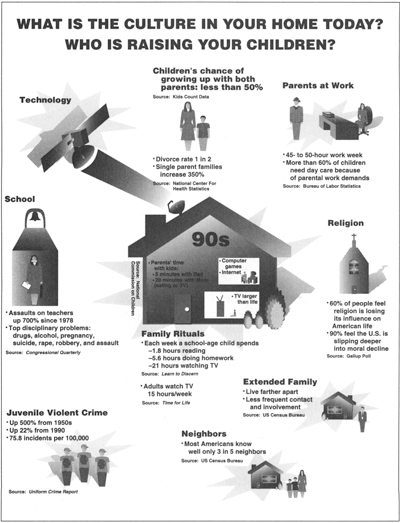

We took a brief look at a few major trends in Chapter 1. But now let’s take a closer look at the society we’re living in. Let’s examine a few of the changes over the past forty to fifty years in four dimensions—culture, laws, economy, and technology—and see how these changes impact you and your family. These facts I’m going to share come from surveys done in the United States, but they reflect growing trends worldwide.

Popular Culture

In the 1950s in the United States, the average child watched little or no TV, and what he saw on television was stable, two-parent families who generally interacted with respect. Today, the average child watches seven hours of television per day. By the end of grade school he’s seen over eight thousand murders and one hundred thousand acts of violence.6 During this time he’s spent an average of five minutes a day with his father and twenty minutes with his mother, and most of that time was spent either eating or watching TV!7

Just think about it: seven hours of TV a day and five minutes with Dad. Unbelievable!

He also has increasing access to videos and music that portray pornography, illicit sex, and violence. As we noted in Chapter 1, he goes to schools where the major concerns have shifted from chewing gum and running in the halls to drug abuse, teen pregnancy, suicide, rape, and assault.

Just think about it: The average child spends seven hours a day watching TV and five minutes with Dad. Unbelievable!

In addition to these influences, many homes have actually begun to take on the tone of the business world. In her groundbreaking analysis The Time Bind, sociologist Arlie Hochschild points out how, for many people, home and office have changed places. Home has become a frantic exercise in “beat the clock,” with family members having fifteen minutes to eat before rushing off to a soccer game, and trying to bond in the half hour before bed so they don’t waste time. At work, on the other hand, you can socialize and relax on a break. By comparison, work seems like a refuge—a haven of grown-up sociability, competence, and relative freedom. And as a result, some people even allow their workday to lengthen because they enjoy work more than home. Hochschild writes, “In this new model of family-and-work life, a tired parent flees a world of unresolved quarrels and unwashed laundry for the reliable orderliness, harmony, and managed cheer of work.”8

And it’s not just the changing tone of the home environment. There is enormous affirmation on the job. There are many extrinsic rewards—including recognition, compensation, and promotion—that feed our sense of self-worth, exhilarate us, and exert a powerful pull away from family and home. They create a seductive vision of a different destination, an idyllic, warm-climated Utopia that combines the satisfaction of hard work with the apparent justification—in the “busy-ness” of meeting the unbelievable schedules and demands—for neglecting what really matters most.

The rewards of home and family are almost all intrinsic. You’re not paid to do it. You don’t get prestige out of doing it. No one cheers you on in the role.

The rewards of home and family, on the other hand, are almost all intrinsic. In today’s world society is not on the sidelines giving praise and affirmation in your role as a father or mother. You’re not paid to do it. You don’t get prestige out of doing it. No one cheers you on in the role. As a parent your compensation is the satisfaction that comes from playing a significant role in influencing a life for good that no one else can fill. It’s a proactive choice that can only come out of your own heart.

Laws

These changes in the popular culture have driven profound changes in the political will and in resulting law. For example, throughout time, “marriage” has been recognized as the foundation of a stable society. Years ago the U.S. Supreme Court called it “the foundation of society, without which there would be neither civilization nor progress.”9 It was a commitment, a covenant among three parties—a man, a woman, and society. And for many it included a fourth: God.

Author and teacher Wendell Berry has said:

If they had only themselves to consider, lovers would not need to marry, but they must think of others and of other things. They say their vows to the community as much as to one another, and the community gathers around them to hear and to wish them well, on their behalf and on its own. It gathers around them because it understands how necessary, how joyful, and how fearful this joining is. These lovers, pledging themselves to one another “until death,” are giving themselves away, and they are joined by this as no law or contract could ever join them. Lovers, then, “die” into their union with one another as a soul “dies” into its union with God. And so here, at the very heart of community life, we find not something to sell as in the public market but this momentous giving. If the community cannot protect this giving, it can protect nothing.…

The marriage of two lovers joins them to one another, to forebears, to descendants, to the community, to Heaven and earth. It is the fundamental connection without which nothing holds, and trust is its necessity.10

But today, marriage is often no longer a covenant or a commitment. It’s simply a contract between consenting adults—a contract that’s sometimes considered unnecessary, is easily broken when no longer seen as convenient, and is sometimes even set up with the anticipation of possible failure through a prenuptial agreement. Society and God are often no longer even part of it. The legal system no longer supports it; in some instances, in fact, it discourages it by penalizing responsible fatherhood and encouraging mothers on welfare not to marry.

Today, marriage is often no longer a covenant or a commitment. It’s simply a contract between consenting adults—a contract that’s sometimes considered unnecessary and is easily broken.

As a result, according to noted Princeton University family historian Lawrence Stone, “The scale of marital breakdowns in the West since 1960 has no historical precedent that I know of, and seems unique.… There has been nothing like it for the last 2,000 years, and probably longer.” And in the words of Wendell Berry, “If you depreciate the sanctity and solemnity of marriage, not just as a bond between two people but as a bond between those two people and their forebears, their children, and their neighbors, then you have prepared the way for an epidemic of divorce, child neglect, community ruin, and loneliness.”11

Economy

Since 1950 the median income in the United States has increased by ten times, but the cost of the average home has increased by fifteen times and inflation has risen by 600 percent. These changes alone are forcing more and more parents out of the home just to make ends meet. In a critical review of The Time Bind (referred to here), Betsy Morris takes exception to Hochschild’s view that parents spend more time at work because they find it more pleasant than dealing with the challenges of home life. “More likely,” she says, “is that parents are killing themselves because they have to keep their jobs.”12

To make ends meet and for other reasons—including the desire to maintain a certain lifestyle—the percentage of families where there is one parent working and one at home with the children has dropped from 66.7 percent in 1940 to 16.9 percent in 1994. And today some 14.6 million children live in poverty—90 percent of whom live in one-parent homes.13 There is simply much less parental involvement with children, and the reality is that for many, family gets “second shift.”

The very structure of the economic world in which we live has been redefined. When the government took over the responsibility of caring for the aged and destitute in response to the Great Depression, the economic link between family generations was broken. And this has had a reverberating effect on every other link of the family. Economics define survival, and when this economic sense of responsibility between generations is broken, it begins to cut into the other tendons and sinews that hold the generations together, including the social and the spiritual. As a result, the short-term solution has become the long-range problem. In most cases “family” is no longer seen as an intergenerational and extended family unit that cares for itself. It has become reduced to the nuclear family of parents and children at home, and even that is being threatened. The government is seen as the first resource rather than last.

We now live in a world that values personal freedom and independence more than responsibility and interdependence—in a world with tremendous mobility in which creature comforts (especially television) enable social isolation and independent entertainment. Social life is being fractured. Families and individuals are becoming increasingly isolated. Escape from responsibility and accountability is available everywhere.

Technology

Changes in technology have accelerated the impact of changes in every other dimension. In addition to global communication and instant access to vast sources of valuable information, today’s technology also provides immediate, graphic, and often unfiltered access to a full spectrum of highly impactful visual images—including pornography and vivid scenes of bloodshed and violence. Supported by and saturated with advertising, technology puts us into materialistic overload. It has caused a revolution in expectations. Certainly it increases our ability to reach out to others, including family members, and establish connections to people around the globe. But it also diverts us and keeps us from interacting with and relating in meaningful ways to members of our family in our own home.

What does your own heart tell you? Does watching television make you kinder? More thoughtful? More loving? Does it help you build strong relationships in your home?

We can look to research for these answers, but there may be an even better source. What does your own heart tell you about the effects of television on you and your children? Does watching television make you kinder? More thoughtful? More loving? Does it help you build strong relationships in your home? Or does it make you feel numb? Tired? Lonely? Confused? Mean? Cynical?

When we think about the effects of the media on our families, we must realize that the media can literally drive the culture in the home. In order to take seriously what is going on in the media (unlikely romance, promiscuity, battling robots, cynical relationships, fighting, and violent brutality), we must be willing to engage in a “suspension of disbelief.” We must be willing to suspend our disbelief in actions we know as adults are not real—to desensitize our adult wisdom—and for thirty or sixty minutes allow ourselves to be taken on a journey to see how we like it.

What happens to us? We begin to believe that even TV news is normal life! Children especially believe. For example, one mother told me that after watching the six o’clock news on TV, her six-year-old said to her, “Mommy, why is everybody killing everybody?” This child believed what she was seeing was normal life!

It is true that there is so much good on TV—good information and enjoyable, uplifting entertainment. But for most of us and for our families, the reality is more like digging a lovely tossed salad out of the garbage dump. There may be some great salad there, but it’s pretty hard to separate out the trash, the dirt, and the flies.

Low-grade, gradual pollution can desensitize us not only to how awful the pollution but also to what we are trading off for it. It would take an enormous amount of benefit from television to trade off the time that could be spent with family members learning, loving, working, and sharing together!

A recent U.S. News & World Report poll reported that 90 percent of those polled felt that the nation is slipping deeper into moral decline. That same poll found that 62 percent felt TV was hostile toward their moral and spiritual values.14 So why are so many watching so much TV?

As the societal indicators of crime, drug use, sexual pleasuring, and violence go on their upward climb with few plateaus, we should not forget that the most important indicator in any society is the commitment to loving, nurturing, and guiding the most important people in our lives—our children. Children learn the most important lessons not from Power Rangers or even Big Bird but from a loving family who reads with them, talks to them, works with them, listens to them, and spends happy time with them. When children feel loved, really loved, they thrive!

Suppose you were on your deathbed. Would you really wish you’d spent more time watching TV?

Reflect for one moment: What were the most memorable family times in your own life? Suppose you were on your deathbed. Would you really wish you’d spent more time watching TV?

In their book Time for Life, sociologists John Robinson and Geoffrey Godbey reported that on the average, Americans spend fifteen of their forty hours of free time every week watching television. They suggest that maybe we are not as “busy” as we seem to be.15

As Marilyn Ferguson said in her landmark book The Aquarian Conspiracy, “Before we choose our tools and technology, we must choose our dreams and values, for some technologies serve them, while others make them unobtainable.”16

* * *

It becomes increasingly apparent that the shifts in these meta-structures are dislocating everything. Almost all businesses are being reinvented and restructured to make them more competitive. Globalization of technology and markets is threatening the very survival not only of businesses but of governments, hospitals, health care, and educational systems as well. Every institution—including the family—is being impacted today as never before.

These changes represent a profound shift in the infrastructure, the underlying framework of our society. As Stanley M. Davis, a friend and colleague in various leadership development conferences, has said, “When the infrastructure shifts, everything else rumbles.”17 These meta-structure shifts represent the turning of a major gear, which in turn turns a smaller gear and then a smaller one, and eventually the tiny ones at the other end are whizzing. Every organization is being affected—including the family.

As we’re moving from the industrial to the informational infrastructure, everything is being dislocated and must find its bearing again. And yet many people are completely unaware of all this happening. Even though they see it and it creates anxiety, they don’t know what is happening or why, or what they can do about it.

A High Trapeze Act … with No Safety Net!

Where this infrastructure shift affects us all most personally and profoundly is in our families, our homes. Trying to successfully raise a family today is like trying to perform a high trapeze act—a feat that requires tremendous skill and almost unparalleled interdependence—and there’s no safety net!

There used to be a safety net. There were laws that supported the family. The media promoted it, upheld it. Society honored it, sustained it. And the family, in turn, sustained society. But there is no safety net anymore. The culture, the economics, and the law have unraveled it. And technology is accelerating the disintegration.

In a 1992 statement, the U.S. Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Department summarized literally hundreds of research studies of environmental changes over recent years:

Unfortunately, economic circumstances, cultural norms, and federal legislation in the last two decades have helped to create an environment that is less supportive to strong, stable families … [and] at the same time these economic changes have occurred, the extended family support system has eroded.18

And all of this has happened so gradually that many are not even aware of it. It’s like the story that author and commentator Malcolm Muggeridge tells about some frogs that were killed without resistance by being boiled alive in a cauldron of water. Normally, a frog thrown into boiling water will immediately jump out, saving his life. But these frogs didn’t jump out. They didn’t even resist. Why? Because when they were put into the cauldron, the water was tepid. Then little by little the temperature was raised. The water became warm … then warmer … then hot … then boiling. The change was so gradual that the frogs accommodated themselves to their new environment until it was too late.

This is exactly what happens with all of these forces in the world. We get used to them and they become our comfort zone—even though they’re literally killing us and our families. In the words of Alexander Pope:

Vice is a monster of so frightful mien,

As to be hated needs but to be seen;

Yet seen too oft, familiar with her face,

We first endure, then pity, then embrace.19

It’s a process of gradual desensitization. And this is exactly what happens when we gradually subordinate principles to social values. These powerful cultural forces fundamentally alter our moral or ethical sense of what is, in fact, right. We even begin to think of social values as principles and call “bad” “good” and “good” “bad.” We lose our moral bearings. The airwaves get polluted with filth. The static makes it difficult to get a clear message from radio control.

And—to use the airplane metaphor again—we experience vertigo. This is what sometimes happens to a pilot who is flying without the use of instruments and goes through a sloping cloud bank, for example. He can no longer perceive ground references, and he may not even be able to tell from the “seat of the pants” sensation (the response of nerve endings in the muscles and joints) or from the tiny balance organs that are part of the inner ear, which way is up—because these feedback mechanisms are both dependent on a correct orientation to the pull of gravity. So as the brain struggles to decipher the messages sent from the senses without the clues normally supplied by vision, incorrect or conflicting interpretation may result. And the result of such sensory confusion is this dizzy, whirling sensation known as vertigo.

When we encounter extremely powerful influence sources … we literally experience a kind of conscience or spiritual vertigo. We become disoriented. Our moral compass is thrown off.

Similarly in life, when we encounter extremely powerful influence sources, such as a powerful social culture, charismatic people, or group movements, we experience a kind of conscience or spiritual vertigo. We become disoriented. Our moral compass is thrown off, and we don’t even know it. The needle that in less turbulent times pointed easily to “true north”—or the principles that govern in all of life—is being jerked about by the powerful electric and magnetic fields of the storm.

The Metaphor of the Compass

To demonstrate this phenomenon in my teaching—and to make five important points related to it—I will often get up in front of an audience and ask them to close their eyes. I say, “Now without peeking, everyone point north.” There is a little confusion as they all try to decide and point in the direction they think is north.

I then ask them to open their eyes and see where people are pointing. At that point there’s usually a great deal of laughter because they see that people are pointing in all directions—including straight up.

I then bring out a compass and show the north indicator, and I explain that north is always in the same direction. It never changes. It represents a natural magnetic force on the earth. I have used this demonstration in places throughout the world—including on ships at sea and even on satellite broadcasts with hundreds of thousands of people participating in different locations around the globe. It is one of the most powerful ways I have ever found to communicate that there is such a thing as magnetic north.

I use this illustration to make the first point: Just as there is a “true north”—a constant reality outside ourselves that never changes—so there are natural laws or principles that never change. And these principles ultimately govern all behavior and consequences. From that point on I use “true north” as a metaphor for principles or natural law.

I then proceed to show the difference between “principles” and behavior. I lay the see-through compass on an overhead so they can see the north indicator as well as the arrow that stands for the direction of travel. I move the compass around on the overhead so they can see that while the direction of travel changes, the north indicator never does. So if you want to go due east, you can put the arrow ninety degrees to the right of north and then follow that path.

I then explain that “direction of travel” is an interesting expression because it communicates essentially what people do; in other words, their behavior comes out of their basic values or what they think is important. If going east is important to them, they value that; therefore, they behave accordingly. People can move about based on their own desire and will, but the north indicator is totally independent of their desire and will.

I make the second point: There is a difference between principles (or true north) and our behavior (or direction of travel).

This demonstration enables me to introduce the third point: There is a difference between natural systems (which are based on principles) and social systems (which are based on values and behavior). To illustrate, I ask, “How many have ever ‘crammed’ in school?” Almost the entire audience raises their hands. I then ask, “How many got good at it?” Almost the same number raises their hands again. In other words, “cramming” worked.

I ask, “How many have ever worked on a farm?” Usually 10 to 20 percent raise their hands. I ask those people, “How many of you ever crammed on the farm?” There’s always extensive laughter because people immediately recognize that you can’t cram on the farm. It simply won’t work. It is patently absurd to think you can forget to plant in the spring and goof off all summer, then hit it hard in the fall and expect to bring in the harvest.

I ask, “How come cramming works in school and not on the farm?” And people come to realize that a farm is a natural system governed by natural laws or principles, but a school is a social system—a social invention—that is governed by social rules or social values.

I ask, “Is it possible to get good grades and even credentials out of school and not get an education?” And almost everyone acknowledges this is possible. In other words, when it comes to the natural system of developing your mind, it is governed more by the law of the farm than the law of the school—by a natural rather than a social system.

Then I proceed with this analysis into other areas that people can relate to, such as the body. I ask, “How many of you have tried to lose weight a thousand times in your life?” A good percentage raise their hands. I ask them, “What really is the whole key to weight loss?” Eventually, everyone comes to see that in order to achieve permanent and healthy weight loss, you must align the direction of travel—your habits and your lifestyle—with the natural laws or the principles that bring the desired result, with principles such as proper nutrition and regular exercise. The social value system may reward immediate weight loss through some crash diet program, but the body eventually outsmarts the strategy of the mind. It will slow down the metabolism processes and turn on the fat thermostat. And eventually the body returns to where it was—or perhaps even worse. So people begin to see that not only the farm but also the mind and the body are governed by natural laws.

I then apply this line of reasoning to relationships. I ask, “In the long run, are relationships governed more by the law of the farm or the law of the school?” People all acknowledge they’re governed by the law of the farm—that is, natural laws or principles rather than social values. In other words, you can’t talk yourself out of problems you behave yourself into, and unless you are trustworthy, you cannot produce trust. They come to acknowledge that the principles of trustworthiness, integrity, and honesty are the foundation of any relationship that endures over time. People may fake it for a period of time or cosmetically impress others, but eventually “the hens come home to roost.” Violated principles destroy trust. And it doesn’t make any difference if you’re dealing with relationships between people, or relationships between organizations, or relationships between society and government or between one nation and another. Ultimately, there is a moral law and a moral sense—an inward knowing, a set of principles that are universal, timeless, and self-evident—that control.

I then apply this level of thinking to issues in our society. I ask, “If we were really serious about health reform, what would we primarily focus on?” Almost everyone acknowledges that we would focus on prevention—on aligning people’s behavior, their value system, their direction of travel with natural law or principles. But the social value system regarding health care—which is in the direction of travel of society—focuses primarily on the diagnosis and treatment of disease rather than on prevention or lifestyle alteration. In fact, more money is often spent in the last few weeks or days of a person’s life in heroic efforts to keep that person alive than was spent on prevention during the person’s entire life. This is where society’s value system is, and it has essentially assigned medicine this role. That’s why almost all medical dollars are spent on diagnosis and treatment of disease.

I then carry this analysis into education reform, welfare reform, political reform—actually, any reform movement. Ultimately people come to realize the fourth point: The essence of real happiness and success is to align the direction of travel with natural laws or principles.

Finally, I show the tremendous impact that the traditions, trends, and values of the culture can have on our sense of true north itself. I point out that often even the building we’re in can distort our sense of true north because it has a magnetic pull of its own. When you go outside the building and stand in nature, the north indicator shifts slightly. I compare this pull to the power of the wider culture—the mega traditions, trends, and values that can slightly warp our conscience so that we’re not even aware of it until we get out into nature alone where the “compass” really works, where we can slow down, reflect, and go deep inside ourselves to listen to our conscience.

I show the compass north shifting when I put it on the overhead projector, because the machine itself represents a magnetic force. I compare this to a person’s subculture—which could be the culture of the family or a business organization or a gang or a group of friends. There are many levels of subculture, and the illustration of how a machine can throw off the compass is very powerful. It’s easy to see how people lose their moral bearings and get uprooted by the need for acceptance and belonging.

This is perhaps the greatest role of parenting. More than directing and telling children what to do, it’s helping them connect with their own gifts—particularly conscience.

Then I take my pen and put it up against the compass, and I show how I can make the compass needle jump all over the place; how I can totally reverse it so that north looks south. I use this to explain how people can actually come to define “good” as “bad” and “bad” as “good,” because of an extremely powerful personality they come in contact with or an extremely powerful emotional experience—such as abuse or parental betrayal—or profound conscience betrayal. These traumas may be so shaking and devastating as to undermine their whole belief system.

I use this demonstration to make the fifth and final point: It’s possible for our deep, inward sense of knowing—our own moral or ethical sense of natural laws or principles—to become changed, subordinated, even eclipsed, by traditions or by repeated violation of one’s own conscience.

In spite of the work we do on mission statements, if we don’t internalize them in our hearts and minds and inside the culture of the family, these cultural forces will confuse and disorient us. They will stagger our sense of morality so that “wrong” is defined more by getting caught than by doing wrong.

This is also why it’s so important that pilots be trained in the use of instruments—whether or not they actually fly in instrument conditions. And that’s why it’s so important that children be trained to use the instruments—the four human gifts that help keep them on track. This is perhaps the greatest role of parenting. More than directing and telling children what to do, it’s helping them connect with their own gifts—particularly conscience—so that they are well trained and have immediate access to the lifesaving connection that will keep them oriented and on track. Without such a lifesaving connection, people crash. They become seduced by the culture.

Striking at the Root

I once attended a conference entitled “Religions United Against Pornography” in which leaders of religious organizations as well as women’s groups, ethnic groups, and educators joined together, united by the fight against this pernicious evil that victimizes primarily women and children. It became clear that although the subject was repugnant to people’s sense of decency and virtue and they would rather not discuss it, they knew it must be discussed because it is a reality in our culture.

At this conference we were shown video clips of interviews with people off the street, including many young men and young couples. These were not violent gang members, druggies, or criminals; they were normal, everyday people who looked on pornography as entertainment. Some said they watched it daily, sometimes several times a day. As we viewed these clips it became clear to us that pornography had become deeply embedded in the culture of many of the youth in the country today.

I gave a presentation on how to bring about culture change. I then attended a session where women leaders addressed this issue. They related how Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) had become a compelling force in society when enough women became so alarmed about the issue of alcohol abuse that their involvement created a serious impact on the cultural norms in American society. They gave us booklets that described rather than showed the kind of pornography that was out there. And as I read about it, I became physically ill.

In my second and final presentation I told of this experience and how convinced I was that the key to culture change is to get people so immersed in the reality of what’s happening that they can truly feel its full pernicious, sinister impact on the ethical and moral nature of people’s minds and hearts and how this affects our whole society. The key is to make people sick the way I had been made sick, involve them in the data until they become thoroughly repulsed and motivated, and then give them hope. Get them involved in coming up with solutions and identifying what has happened elsewhere that has been successful. Work on awareness and conscience before you work on imagination and will. Stir up the first two human gifts before releasing the energy of the next two. Then search together for models and mentoring people or organizations that can influence for good and develop laws that promote the good and protect the innocent.

But above all—above legislation, above every effort to influence popular culture—strengthen the home. As Henry David Thoreau put it, “For every thousand hacking at the leaves of evil, there is one striking at the root.” The home and family are the root. This is where the moral armament is developed in people to deal with these pernicious influences that technology has made available and to turn the technology into something that enables and facilitates good virtues and values and standards to be maintained throughout society.

For laws to be effective there has to be a social will (a set of mores) to enforce those laws. The great sociologist Émile Durkheim said, “When mores are sufficient, laws are unnecessary. When mores are insufficient, laws are unenforceable.” Without social will, there will always be legal loopholes and ways to break the law. And children can quickly lose their innocence and become callous and eroded inside—sarcastic and cynical and far more vulnerable as prey to violent gang behavior, to adoption into a new “family” that gives acceptance and social approbation. So the key is to nurture the four gifts inside each child and to build relationships of trust and unconditional love so that you can teach and influence the members of your family in principle-centered ways.

“For every thousand hacking at the leaves of evil, there is one striking at the root.”

Interestingly, one other significant outcome of the conference was the change in the very culture and feeling among the leaders of the various faiths. In just two days it moved from courteous respect and exchange of pleasantries to genuine love, profound unity, and open, authentic communication because of a common, transcendent mission. As the leaders discovered, in these perilous times we must focus on what unites us, not on what divides us!

Who’s Going to Raise Our Children?

In the absence of an inner connection with the four human gifts and a strong family influence, what impact is the kind of culture we’ve described in this chapter—power boosted by technology—going to have on a child’s thinking? Is it realistic to think that children are going to be impervious to the murder and killing and cruelty they watch seven hours a day on TV? Can we really believe the TV program directors who claim there is no hard scientific evidence to show a correlation between violence and immorality in our society and the graphic scenes they choose to show on the television screen—and then quote hard scientific evidence to show how much a twenty-second advertisement will impact the behavior of the viewers?20 Is it reasonable to think that young adults exposed to a visual and emotional TV diet of sexual pleasuring can grow up with anywhere near a realistic or holistic sense of the principles that create good, enduring relationships and a happy life?

In such a turbulent environment, how can we possibly think that we can continue with “business as usual” inside our families? If we don’t build better homes, we’ll have to build more prisons because surrogate parenting will nurture gangs. Then the social code will surround drugs, crime, and violence. Jails and courts will become even more overcrowded. “Catch and release” will become the order of the day. And emotionally starved children will turn into angry adults, plowing through life for love, respect, and “things.”

In an epic historical study, one of the world’s greatest historians, Edward Gibbon, identified five main causes of the decline and fall of Roman civilization:

1. the breakdown of the family structure

2. the weakening of a sense of individual responsibility

3. excessive taxes and government control and intervention

4. seeking pleasures that became increasingly hedonistic, violent, and immoral

5. the decline of religion.21

His conclusions provide a stimulating and instructive perspective through which we might well look at the culture of today. And this brings us to the pivotal question on which our future and the future of our children depends:

Who’s going to raise my children—today’s alarmingly destructive culture or me?

As I said in Habit 2, if we don’t take charge of the first creation, someone or something else will. And that “something” is a powerful, turbulent, amoral, family-unfriendly environment.

This is what will shape your family if you do not.

“Outside in” No Longer Works

As I said in Chapter 1, forty years ago you could successfully raise a family “outside-in.” But outside-in no longer works. We cannot rely on societal support of our families as we used to. Success today can only come from the inside out. We can and we must be the agent of change and stability in creating the supporting structures for our families. We must be highly proactive. We must create. We must reinvent. We can no longer depend on society or most of its institutions. We must develop a new flight plan. We must rise above the turbulence and chart a “true north” path.

Just consider the effects of these changes in the culture of the home and the environment as represented in the chart on these pages. Think about the impact these changes are having on your own family. The point of comparing today to the past is not to suggest that we return to some idealized notion of the 40s and 50s. It is to recognize that because things have changed so much, and because the impact on the family is so staggering, we must respond in a way that is equal to the challenge.

History clearly affirms that family is the foundation of society. It is the building block of every nation. It is the headwaters of the stream of civilization. It is the glue by which everything is held together. And family itself is a principle built deeply into every person.

But the traditional family situation and the old family challenge are gone. We must understand that, more than at any other time in history, the role of parenting is absolutely vital and irreplaceable. We can no longer depend on role models in society to teach our children the true north principles that govern in all of life. We are grateful if they do, but we cannot depend on it. We must provide leadership in our families. Our children desperately need us. They need our support and advice. They need our judgment and experience, our strength and decisiveness. More than ever before they need us to provide family leadership.

So how do we do it? How do we prioritize and lead our families in significant, productive ways?

Creating Structure in the Family

Think once again about the words of Stanley M. Davis: “When the infrastructure shifts, everything else rumbles.”

The profound technological and other changes we’ve talked about have impacted organizations of all kinds in our society. Most organizations and professions are being reinvented and restructured to accommodate this new reality. But this same kind of restructuring has not happened in the family. Despite the fact that outside-in no longer works, and despite the astounding report that today only 4 to 6 percent of American households are made up of the “traditional” working husband, wife at home, and no history of divorce for either partner,22 most families are not effectively restructuring themselves. They’re either trying to carry on in the old way—the way that worked with the challenges of the past—or they’re trying to reinvent in ways that are not in harmony with the principles that create happiness and enduring family relationships. As a whole, families are not rising to the level of response the challenge demands.

So we must reinvent. The only truly successful response to structural change is structure.

When you consider the word “structure,” think carefully about your response to it. As you do, be aware that you are trying to navigate through an environment where the popular culture rejects the idea of structure as being limiting, confining.

But consult your own inner compass. Think about the words of Winston Churchill: “For the first twenty-five years of my life I wanted freedom. For the next twenty-five years of my life I wanted order. For the next twenty-five years of my life I realized that order is freedom.” It is the very structure of marriage and family that gives stability to society. The father in a popular family television show during the outside-in era said this: “Some men see the rules of marriage as a prison; others—the happy ones—see them as boundary lines that enclose all the things they hold dear.” It is the commitment to structure that builds trust in relationships.

Think about it: When your life is a mess, what do you say? “I have to get organized. I have to put things in order!” This means creating both structure and priority or sequencing. If your room is a mess, what do you do? You organize your things in closets and dresser drawers. You organize within structure. When we say about someone, “He has his head screwed on straight,” what do we mean? We basically mean that his priorities are in order. He’s living by what’s important. When we say to a person with a terminal disease, “Get your affairs in order,” what do we mean? We mean, “Make sure your finances, insurance, relationships, and so forth, are attended to.”

“Ultimately, we must decide either to steer or to go where the river takes us. The key to successful steering is to be intentional about our family rituals.”

In a family, order means that the family is prioritized and that some kind of structure is in place to make that priority happen. In the mega sense, Habit 2—the creation of a family mission statement—provides the foundational structure for the inside-out approach to family living. In addition, there are two major organizing structures or processes that will help you put the family first in a meaningful way in your daily life: a weekly “family time” and one-on-one bonding times.

As prominent marriage and family therapist William Doherty said, “The forces pulling on families are just too strong in the modern world. Ultimately, we must decide either to steer or to go where the river takes us. The key to successful steering is to be intentional about our family rituals.”23

Weekly Family Time

Outside of making and honoring the basic marriage covenant, I have come to feel that probably no single structure will help you prioritize your family more than a specific time set aside every week just for the family. You could call it “family time,” “family hour,” “family council,” or “family night” if you prefer. Whatever you call it, the main purpose is to have one time during the week that is focused on being a family.

A thirty-four-year-old woman from Oregon shared this:

My mother was the instigator of a weekly family activity time where we children got to pick whatever we wanted to do. Sometimes we went ice skating. At other times we went bowling or to a movie. We absolutely loved it! We always topped it off with a visit to our favorite restaurant in Portland. Those activity days always left me with a feeling of great closeness and that we really were part of a family unit.

I have such fond memories of these times. My mother passed away when I was a teenager, and this had a very traumatic impact on me. But my dad has made sure that every year since her death we all get together for at least one week—in-laws, children, everyone—to rekindle those same feelings.

When family members all leave to go to their homes in different states, I feel sad and yet so rich. There is such strength in a family that has lived together under the same roof. And the new members of our family have in no way detracted from this feeling—they have only enriched it.

My mother left quite a legacy. I have not married, but my brothers and sisters faithfully have their own weekly family times with their children. And that particular restaurant in Portland is still a gathering spot for us all.

Notice the feelings this woman is expressing about her memories of these family times. And look at the impact it has on her life now, on her relationships with her brothers and sisters, and on their relationships with the members of their families. Can you begin to see the kind of bonding a weekly family time creates? Can you see the way it builds the Emotional Bank Account?

A woman from Sweden shared this story:

When I was about five or six years old, my parents talked to someone who told them of the value of having regular meetings with their family. So they began to do it in our home.

I remember the first time my dad shared with us a principle of life. It was very powerful to me, because I had never seen him in the role of formal teacher, and I was impressed. My dad was a busy and successful businessman and had not had very much time for us children. I remember how special and important it made me feel that he valued us enough to take time out of his busy schedule and sit down and explain how he felt about life.

I also recall an evening when my parents invited a famous surgeon from the United States to join us for our family time. They asked him to share his experiences of medicine with us and how he had been able to help people all over the world.

This surgeon told us how decisions he had made in life eventually led him to reaching his goals and becoming more than he had imagined. I never forgot his words and the importance of taking each challenge “one step at a time.” But more important, his visit left me with the feeling that it was really neat that my parents wanted to invite visitors home to share their experiences with us.

Today I have five children, and almost monthly we bring some “outsider” to our home to get acquainted with, share with, and learn from. I know it is a direct result of what I saw in my parents’ home. In our jobs or at school, we have an opportunity to be exposed to people from other countries, and their visits have enriched our lives and have resulted in close friendships worldwide.

This woman was profoundly influenced by a regular family time as she was growing up and has passed the legacy on to her children. Think about the difference this will make to her children as their family tries to navigate through a turbulent, family-unfriendly environment.

A weekly family night is something we’ve had as part of our own family from the very beginning. When the children were very small, we used it as a time of deep communication and planning for the two of us. As they got older, we used the time to teach them, to play with them, and to involve them in fun and meaningful activities and family decisions. There have been times when one of us or one of the children could not be there. But for the most part we’ve tried to always set aside at least one evening a week as family time.

On a typical family night we would review our calendar on upcoming events so everyone would know what was going on. Then we’d hold a family council and discuss issues and problems. We’d each give suggestions, and together we’d make decisions. Often we would have a talent show where the kids would show us how they were coming along with their music or dance lessons. Then we’d have a short lesson and a family activity and serve refreshments. We would also always pray together and sing one of our family’s favorite songs, “Love at Home” by John Hugh McNaughton.

In this way we would accomplish what we have come to feel are the four main ingredients of a successful family time: planning, teaching, problem-solving, and having fun.

Notice how this one structure can meet all four needs—physical, social, mental, and spiritual—and how it can become a major organizing element in the family.

But family time doesn’t have to be that involved—especially at first. If you want, you can just begin to do some of these things at a special family dinner. Use your imagination. Make it fun. After a while, family members will begin to realize they are receiving nourishment in more ways than one, and it will be easier to hold a more involved family time. People—particularly little children—long for family experiences that make them feel close to one another. They want a family in which people demonstrate that they care about one another. Also, the more often you do things like this in your family, the easier it will become.

And you cannot begin to imagine the positive impact this will have on your family. A friend of mine did his doctoral dissertation on the effect of holding family meetings on the self-image of children. Although his research showed the positive effect was significant, one unanticipated and surprising result was the positive effect that holding such meetings had on the fathers. He tells of one father who felt very inadequate and was initially reluctant to try to hold such meetings. But after three months the father said this:

Growing up, my family didn’t talk much except to put each other down and to argue. I was the youngest, and it seemed as if everyone in the family told me that I couldn’t do anything right. I guess I believed them, so I didn’t do much in school. It got so I didn’t even have enough confidence to try anything that took any brains.

I didn’t want to have these family nights because I just didn’t feel I could do it. But after my wife led a discussion one week and my daughter another week, I decided to try one myself.

It took a lot of courage for me to do it, but once I got started, it was like something turned loose in me that had been tied up in a painful knot ever since I was a little boy. Words just seemed to flow out of my heart. I told the members of my family why I was so glad to be their dad and why I knew they could do good things with their lives. Then I did something I had never done before. I told them all, one by one, how much I loved them. For the first time I felt like a real father—the kind of father I wished my father had been.

Since that night I have felt much closer to my wife and kids. It’s hard to explain what I mean, but a lot of new doors have opened for me and things at home seem different now.

Weekly family times provide a powerful, proactive response to today’s family challenge. They provide a very practical way to prioritize the family; the time commitment itself tells the children how important the family is. They build memories. They build Emotional Bank Accounts. They help you create your own family safety net. They also help you meet several fundamental family needs: physical, economic, social, mental, aesthetic, cultural, and spiritual.

I have taught this idea now for over twenty years, and many couples and single parents have said that family time is an enormously valuable and practical “take home” idea. They say it has had the most profound effect on family prioritization, closeness, and enjoyment of any family idea they have ever heard.

Turning Your Mission Statement into Your Constitution Through “Family Time”

Family time provides a great opportunity to discuss and create your family mission statement. And once you have the mission statement, it can help you meet the need for a practical way to turn it into the constitution of your family life and to meet four everyday needs: spiritual (to plan), mental (to teach), physical (to solve problems), and social (to have fun).

Sandra:

On one of our family nights, we were talking about the kind of family we wanted to be as we had described in our mission statement. We got into a discussion about service and how important it is to serve one another—the family, neighbors, and the larger community.

So for the next family night I decided to prepare a lesson on service. We rented the video Magnificent Obsession. It tells the story of a rich playboy who became involved in a car accident that resulted in a girl’s becoming blind. It showed how he felt guilty and terrible about it and realized that his careless actions had changed her life forever. In some way he wanted to make this up to her and help her deal with her new life situation, so he consulted a friend—an artist—who tried to teach him how to give anonymous service and help other people. At first he struggled with it and had difficulty understanding the reasons he should do this. But eventually he learned how to look for needs in people and situations and step into their lives and anonymously create positive change.

As we discussed this movie, we talked about what a great neighborhood we lived in—how caring and responsible the people were and how much we appreciated them. We all agreed that we wanted them to know that, and we wanted to be of some service or do something for them. We created what we called the “Phantom Family.” For about three months at every family night we made a special treat—popcorn balls, candy apples, cupcakes, or something similar. We decided which family we were going to spotlight. Then we put the treat on their porch, along with a note that told how we admired their family and appreciated them. We ended the note with “the Phantom Family strikes again!” We rang the doorbell and ran like wildfire.

Each week we did the same thing. We never did get caught, although on one occasion we were reported to the police because someone thought we were trying to break in!

Pretty soon all the neighbors were talking about the Phantom Family. We acted as if we didn’t know anything about it, but were also wondering who in the world the Phantom Family could be. People eventually had their suspicions, and one night we were left a treat with a note that said, “To the Phantom Family—from Your Suspicious Neighbors.”

The plotting, drama, and mystery made a great adventure. It also enabled us all to learn more about the principle of anonymous service and to more fully integrate an important part of our family mission statement into our lives.

We’ve found that every idea in our mission statement provides a great basis for family time discussions and activities—things that help us translate the mission into moments of family living. And as long as we make it fun and exciting, everyone learns and enjoys.

By creating and living by a mission statement, families are gradually able to build moral authority in the family itself. In other words, principles get built right into the very structure and culture of the family, and everyone comes to realize that principles are at the center of the family and are the key to keeping the family strong, together, and committed to its destination. Then the mission statement becomes like the Constitution of the United States—the ultimate arbiter of every law and statute. The principles upon which it is based and the value systems that flow out of those principles create a social will that is filled with moral or ethical authority.

A Time to Plan

One husband and father shared the following:

A couple of years ago my wife and I noticed that our summers were getting increasingly busy, and we were not spending as much time with the kids as we wanted while they were out of school. So right after school let out, we had a family night where we asked the children to tell us their favorite summer things to do. They mentioned everything from the little everyday things like swimming and going out for ice cream to daylong activities such as hiking up a nearby mountain and going to the water park. It was fun because each of them got to share what he or she really enjoyed doing.

Once we got all these activities out on the table, we worked on narrowing down the list. Obviously, we couldn’t do everything, so we tried to come up with those activities that everyone thought would be the most fun. Then we pulled out a huge calendar and planned when we would do them. We set aside some Saturdays for major daylong activities. We reserved some weeknights for those that didn’t take as much time. We also marked out a week for our family vacation at Lake Tahoe.

By creating and living by a mission statement, families are gradually able to build moral authority in the family itself.

The children were very excited to see that we had actually planned to do the things that were important to them. And we found over the summer that this planning made a big difference in their happiness and in ours. No longer were they constantly asking when we were going to do something because they knew when we were going to do it. It was on the family calendar. And we held to our plan. We all made it a big priority in our lives. It helped us form a collective commitment, and this sense of commitment greatly strengthened and bonded us.

This planning also made a big difference to me because it helped me commit to do what I really wanted to do but often didn’t do because of the pressure of the moment. There were times when I was tempted to work late to finish a particular project, but I realized that to miss keeping the commitment I’d made to my family would be a big withdrawal. I had to follow through, so I did. And I didn’t feel guilty because that’s what I had planned to do.

As this man discovered, family time is a wonderful time to plan. Everyone’s there and involved. You can decide together how to best spend your family time. And everyone knows what’s happening.

Many families do some kind of weekly planning during their family time. One mother said:

Planning is a big part of our family time together each week. We try to go over each person’s goals and activities, and put them on a magnetic chart that hangs on the door. This enables us to plan family activities together and helps us know what others in the family are doing during the week so that we can support them. It also gives us the information we need to arrange necessary transportation and baby-sitting, and resolve scheduling conflicts.