HABIT 5

SEEK FIRST TO UNDERSTAND … THEN TO BE UNDERSTOOD

To learn to seek first to understand and then to be understood opens the floodgates to heart-to-heart family living. As the fox said in the classic The Little Prince, “And now here is my secret, a very simple secret: It is only with the heart that one can see rightly; what is essential is invisible to the eye.”

As we begin this chapter, I’d like to ask you to try an experiment. Please take a few seconds and just look at the picture on this page.

Now look at this picture and carefully describe what you see.

Do you see an Indian? What does he look like? How is he dressed? Which way is he facing?

You would probably say that the Indian has a prominent nose, that he’s wearing a feathered warbonnet, and that he is looking to the left of the page.

But what if I were to tell you that you’re wrong? What if I said that you were not looking at an Indian but at an Eskimo, and that he is wearing a coat with a hood that covers his head, that he has a spear in his hand, and that he is facing away from you and toward the right side of the page?

Who would be right? Look at the picture again. Can you see the Eskimo? If you can’t, keep trying. Can you see his spear and hooded coat?

If we were talking face-to-face, we could discuss the picture. You could describe what you see to me, and I could describe what I see to you. We could continue to communicate until you showed me what you see in the picture and I showed you what I see.

Because we can’t do that, turn to here and study the picture there. Then look at this picture again. Can you see the Eskimo now? It is important that you see him clearly before you continue reading.

For many years I have used these kinds of perception pictures to bring people to the realization that the way they see the world is not necessarily the way other people see the world. In fact, people do not see the world as it is; they see it as they are—or as they have been conditioned to be.

Almost always this kind of perception experience causes people to be humbled and to be much more respectful, more reverent, more open to understanding.

People do not see the world as it is; they see it as they are—or as they have been conditioned to be.

Often when I teach Habit 5, I will go out into the audience and take a pair of glasses from one person and try to talk another person into wearing them. I usually tell the audience that I’m going to use several methods of human influence to try to get this person to wear these glasses.

When I put these glasses on the person—let’s say a woman—she will usually quickly recoil in some way, particularly if they are strong prescription glasses. And so I appeal to her motivation. I say, “Try harder.” And there’s even more recoiling. Or if she feels intimidated by me, she’ll outwardly tend to go along, but there’s no real buy-in inside. So I say, “Well, I sense you’re kind of rebelling. You’ve got an ‘attitude.’ You’ve got to be positive. Think more positively. You can make this work.” So she’ll kind of smile, but that doesn’t work at all and she knows it. So she’ll usually say, “That doesn’t help at all.”

So then I try to create a little pressure or to intimidate her in some way. I step into the role of a parent and say, “Look, do you have any idea of the sacrifices your mother and I have made for you—the things we’ve done for you, the things we’ve denied ourselves to help you? And you’re going to take this kind of an attitude! Now wear these!” And sometimes that stirs up even more feelings of rebellion. I step into the role of a boss and try to exert some economic pressure: “How current is your résumé anyway?” I appeal to social pressure: “Aren’t you going to be part of this team?” I appeal to her vanity: “Oh, but they look so good on you! Look, everyone. Don’t they complement her features?”

I tap into motivation, attitude, vanity, economic and social pressure. I intimidate. I guilt-trip. I tell her to think positively, to try harder. But none of these methods of influence works. Why? Because they all come from me—not from her and her unique eye situation.

This brings us to the importance of seeking to understand before you seek to influence—of diagnosing before prescribing, as an optometrist does. Without understanding, you might as well be yelling into the wind. No one will hear you. Your effort may satisfy your ego for a moment, but there’s really no influence taking place.

We each look at the world through our own pair of glasses—glasses that come out of our own unique background and conditioning experiences, glasses that create our value system, our expectations, our implicit assumptions about the way the world is and the way it should be. Just think about the Indian/Eskimo experience at the beginning of this chapter. The first picture conditioned your mind to “see” or interpret the second picture similarly. But there was another way to see it that was just as accurate.

One of the main reasons behind communication breakdowns is that the people involved interpret the same event differently. Their different natures and background experiences condition them to do so. If they then interact without taking into account why they see things differently, they begin to judge each other. For instance, take a small thing such as a difference in room temperature. The thermostat on the wall registers 75 degrees. One person complains, “It’s too hot,” and opens the window; the other complains, “It’s too cold,” and closes it. Who is right? Is it too hot or too cold? The fact is they are both right. Logic would say that if two disagree and one is right, the other is wrong. But it isn’t logic; it’s psycho-logic. Both are right—each from his or her own point of view.

As we project our conditioning experiences onto the outside world, we assume we’re seeing the world the way it is. But we’re not. We’re seeing the world as we are—or as we have been conditioned to be. And until we gain the capacity to step out of our own autobiography—to set aside our own glasses and really see the world through the eyes of others—we will never be able to build deep, authentic relationships and have the capacity to influence in positive ways.

And that’s what Habit 5 is all about.

At the Heart of Family Pain Is Misunderstanding

Years ago I had a profound, almost shattering experience that taught me the essence of Habit 5 in a forcible and humbling way.

Our family was on a sabbatical for about fifteen months in Hawaii, and Sandra and I had begun what was to become one of the great traditions of our lives. I would pick her up a little before noon on an old red trail cycle. We would take our two preschool children with us—one between us and the other on my left knee—and ride out in the cane fields by my office. We would ride slowly along for about an hour, just talking. We usually ended up on an isolated beach; we parked the trail cycle and walked about two hundred yards to a secluded spot where we ate a picnic lunch. The children would play in the surf, and we would have great in-depth visits about all kinds of things. We would talk about almost everything.

One day we began to talk about a subject that was very sensitive for us both. I had always been bugged about what I considered Sandra’s inordinate attachment to buying Frigidaire appliances. She seemed to have an obsession about Frigidaire that I was at an absolute loss to understand. She would not even consider buying another brand. Even when we were just starting out and on a very tight budget, she insisted that we drive the fifty miles to the “big city” where Frigidaire appliances were sold, because no dealer in our small university town carried them at that time.

What bothered me the most was not that she liked Frigidaire but that she persisted in making what I considered illogical and indefensible statements that had no basis in fact whatsoever. If she had only agreed that her response was irrational and purely emotional, I think I could have handled it. But her justification was really upsetting. In fact it was such a tender issue that on this particular occasion we kept riding and postponed going to the beach. I think we were afraid to look each other in the eye.

But the spirit was such that we were very open. We started talking about our appliances in Hawaii, and I said, “I know you would probably prefer Frigidaire.”

“I would,” she agreed, “but these seem to be working out fine.” Then she began to open up. She said that as a young girl, she realized that her father worked very hard to support his family. He worked as a high school history teacher and coach for years, and to help make ends meet, he went into the appliance business. One of the main brands he carried in the store was Frigidaire. When he returned home after a full day of teaching and working late into the evening at the appliance store, he would lie on the couch and she would rub his feet and sing to him. It was a beautiful time they enjoyed together almost daily for years. Often during this time he would talk through his worries and concerns about the business, and he shared with Sandra his deep appreciation for Frigidaire. During an economic downturn, he had experienced serious financial difficulties, and the only thing that had enabled him to stay in business was that Frigidaire financed his inventory.

As Sandra shared these things, there were long pauses. I knew that she was tearing up. This was a deeply emotional thing for her. The communication between father and daughter had taken place spontaneously and naturally, when the most powerful kind of scripting takes place. And perhaps Sandra had forgotten about all this until the safety of our year of communication, when it could also come out in very natural and spontaneous ways.

My eyes began to tear as well. I finally started to understand. I had never made it safe for her to talk about it. I had never empathized. I had simply judged. I had just moved in with my logic and my counsel and my condemnation and never even made an effort to really understand. But as Blaise Pascal has said, “The heart has its reasons which reason knows not of.”

We spent a long time in the cane fields that day. And when we finally did arrive at the beach, we felt so renewed, so bonded to each other, so reaffirmed in the preciousness of our relationship, that we just held each other. We didn’t even need to talk.

There’s no way to have rich, rewarding family relationships without real understanding.

There’s no way to have rich, rewarding family relationships without real understanding. Relationships can be superficial. They can be functional. They can be transactional. But they can’t be transformational—and deeply satisfying—unless they’re built on a foundation of genuine understanding.

In fact, at the heart of most of the real pain in families is misunderstanding.

A short time ago a father shared with me the experience of punishing his young son who kept disobeying him by constantly going around the corner. Each time he did so, the father would punish him and tell him not to go around the corner again. But the little boy kept doing it. Finally, after one such punishment, this boy looked at his father with tear-filled eyes and said, “What does ‘corner’ mean, Daddy?”

Catherine (daughter):

For quite a while I couldn’t figure out why our three-year-old son would not go over to his friend’s house to play. The friend would come over several times a week and play at our house, and they got along well. Then this friend would invite our son to play in his yard, which had a big sand pile, swing sets, trees, and a large green lawn. Each time he said he would go, but after walking halfway there, he would always come running back with tears in his eyes.

After I listened to him and tried to discover what his fears were, he finally opened up and told me that he was afraid to go to the bathroom at his friend’s house. He didn’t know where it was. He was afraid he might accidentally wet his pants.

I took him by the hand, and we walked together over to the friend’s house. We talked to his mother, and she showed our son where the bathroom was and how to open the door. She offered to help him find it if he was in need. Feeling greatly relieved, he decided to stay and play, and hasn’t had a problem since.

One of our neighbors related an experience he had had with one of his daughters who was in grade school. All of their other children were very bright, and school was easy for them. He was surprised when this daughter started doing poorly in math. The class was studying subtraction, and she just didn’t seem to get it. She would come home frustrated and in tears.

This father decided to spend an evening with his daughter and get to the bottom of the problem. He carefully explained the concept of subtraction and let her try a few problems. She still wasn’t making the connection. She just didn’t understand.

He patiently lined up five shiny red apples in a row. He took away two apples. All of a sudden her face lit up. It was as if a light had gone on inside her. She blurted out, “Oh, nobody told me we were doing take away.” No one had realized that she had no idea that “subtraction” meant “take away.”

Most mistakes with family members are not the result of bad intent. It’s just that we really don’t understand. We don’t see clearly into one another’s hearts.

From that moment on, she understood. With young children we have to understand where they are coming from, what they are thinking, because they usually don’t have the words to explain it.

Most mistakes with our children, with our spouses, with all family members are not the result of bad intent. It’s just that we really don’t understand. We don’t see clearly into one another’s hearts.

If we did—if an entire family could develop the kind of openness we’re talking about—over 90 percent of the difficulties and problems could be resolved.

A Flood of Witnesses

People have begun to realize that much of the pain in families is caused by lack of understanding. And if you take a look at the best-selling family books on the market today, you can get an idea of how significant this pain and this growing awareness are.

Books such as Deborah Tannen’s You Just Don’t Understand and John Gray’s Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus have become tremendously popular because they touch on this pain. And these books come on the crest of a wave of recognition of the problem. In the recent past there have been many other writers on the family, including Carl Rogers, Thomas Gordon, and Haim Ginott, who have recognized and attempted to deal with this issue. They provide a flood of witnesses who affirm the vital importance of seeking to understand.1

The fact that these books, programs, and movements have had enduring value illustrates how much people hunger to feel understood.

Satisfactions and Judgments Surround Expectations

Perhaps the greatest contribution of these materials is in helping us realize that by understanding the differences between people, we can learn to take them into account and adjust our expectations accordingly. Much of the material focuses on gender differences, but there are also other powerful dimensions that create differences, such as past and present experiences in the family and on the job. By understanding these differences we can adjust our expectations.

Basically, our satisfactions come from our expectations. So if we’re aware of our expectations, we can adjust them accordingly and—in a very real sense—adjust our satisfactions as well. To illustrate: I knew of one couple who came into marriage with totally different expectations. She expected everything to be sunshine, daffodils, and “happily ever after.” When the realities of marriage and family life hit, she spent much of her time feeling disappointed, frustrated, and dissatisfied. He, on the other hand, anticipated having to deal with the challenges of marriage and family life. And every moment of joy was a wonderful, happy surprise to him, for which he was deeply grateful.

As Gordon B. Hinckley, a wise leader, commented:

Of course all of marriage is not bliss. Stormy weather occasionally hits every household. Connected inevitably with the whole process is much of pain—physical, mental, and emotional. There is much of stress and struggle, of fear and worry. For most there is the ever haunting battle of economics. There seems never to be enough money to cover the needs of the family. Sickness strikes periodically. Accidents happen. The hand of death may reach in and with dread stealth to take a precious one. But all of this seems to be part of the processes of family life. Few indeed are those who get along without experiencing some of it.2

To understand that reality—and to adjust expectations accordingly—is, to a great extent, to control our own satisfaction.

Our expectations are also the basis for our judgments. If you knew, for example, that children in a growth stage of around six or seven had a very strong tendency to exaggerate, you wouldn’t overreact to that behavior because you would understand. That’s why it is so important to understand growth stages and unmet emotional needs, as well as what changes are taking place in the environment that stir up emotional needs and lead to particular behavior. Most child experts agree that almost all “acting out” can be explained in terms of growth stages, unmet emotional needs, environmental changes, just plain ignorance, or a combination.

When you understand, you don’t judge.

Isn’t it interesting: When you understand, you don’t judge. We even say to each other, “Oh, if you only understood, you wouldn’t judge.” You can see why the wise, ancient king Solomon prayed for an understanding heart, why he wrote, “In all thy getting, get understanding.” Wisdom comes from such understanding. Without it, people act unwisely. Yet from their own frame of reference, what they are doing makes perfect sense.

The reason we judge is that it protects us. We don’t have to deal with the person; we can just deal with the label. In addition, when you expect nothing, you’re never disappointed.

But the problem with judging or labeling is that you begin to interpret all data in a way that confirms your judgment. This is what is meant by “prejudice” or “prejudgment.” If you have judged a child as being ungrateful, for example, then you will subconsciously look for evidence in his behavior to support that judgment. Another person looking at the exact same behavior may see it as evidence of gratitude and appreciation. And the problem is compounded when you act on the basis of what you consider reconfirmed judgment—and it produces more of the same behavior. It becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

If you label your child as lazy, for example, and you act based on that label, your child will probably see you as bossy, domineering, and critical. Your behavior itself will invoke a resisting response in your child that you interpret as further evidence of his laziness—which gives you justification for being even more bossy, domineering, and critical. It creates a downward spiral, a form of codependency and collusion that feeds on itself until both parties are convinced they are right and actually need the bad behavior of the other to confirm their rightness.

This is the reason that the tendency to judge is such a major obstacle to healthy relationships. It causes you to interpret all data to support your judgment. And whatever misunderstanding existed before is compounded tenfold by the emotional energy surrounding this collusion.

Two major problems in communication are perception, or how people interpret the same data, and semantics, or how people define the same word. Through empathic understanding, both of these problems can be overcome.

Seeking to Understand: The Fundamental Deposit

Consider the following account of a father’s journey in seeking to understand his daughter and how it profoundly influenced them both:

Around the time our daughter Karen turned sixteen, she began to treat us very disrespectfully. She would make a lot of sarcastic comments, a lot of put-downs. And this began carrying over to her younger brothers and sisters.

I didn’t do much about it until it finally came to a head one night. My wife and I and our daughter were in our bedroom, and Karen let fly some very inappropriate comments. I decided that I had had enough, so I said, “Karen, listen. Let me tell you how life works in this household.” And I went through this long, authoritative argument that I was sure would convince her that she should treat her parents with respect. I mentioned all the things we had done for her recent birthday. I talked about the dress we had bought her. I reminded her how we had helped her get her driver’s license and how we were now letting her drive the car. I went on and on, and the list was quite impressive. By the time I finished, I was expecting Karen to almost drop on her knees and worship her parents. Instead, somewhat belligerently she said, “So?”

I was furious. I said angrily, “Karen, you go to your room. Your mother and I are going to talk about consequences, and we’ll let you know what’s going to happen.” She went storming off and slammed her bedroom door. I was so angry, I was literally pacing back and forth, seething with anger. And then suddenly it hit me. I had done nothing to try to understand Karen. I certainly wasn’t thinking win-win. I was totally on my own agenda. This realization caused a profound shift in my thinking and in the way I felt toward Karen.

When I went to her room a few minutes later, the first thing I did was apologize for my behavior. I didn’t excuse any of her behavior, but I apologized for my own. I had been pretty abrupt. I said, “Look, I can tell that something’s going on here, and I don’t know what it is.” I let her know that I really wanted to understand her, and I was finally able to create an atmosphere where she was willing to talk.

Somewhat hesitantly she began to share her feelings about being brand-new in high school: the struggle she was having trying to make good grades and make new friends. She said she was concerned about driving the car. It was such a new experience for her, and she worried whether she was going to be safe. She had just started a new part-time job and was wondering how her boss felt she was doing. She was taking piano lessons. She was teaching piano students. Her schedule was extremely busy.

Finally, I said, “Karen, you’re feeling totally overwhelmed.” And that was it. Bingo! She felt understood. She had been feeling overwhelmed by all these challenges, and her sarcastic comments and disrespect to her family were basically a cry for attention. She was saying, “Please, somebody, just listen to me!”

So I said to her, “Then when I asked you to treat us with a little more respect, that just sounded like one more thing for you to do.”

“That’s right!” she said. “Another thing for me to do—and I can’t handle what’s on my plate now.”

I got my wife involved, and the three of us sat down and brainstormed ways in which Karen might simplify her life. Ultimately, she decided to stop taking piano lessons and stop teaching her piano students—and she felt wonderful about it. In the weeks that followed, she was like a totally changed person.

From that experience she gained more confidence in her ability to make choices in her life. She knew her parents understood her and would support her. And soon after that, she decided to leave her job because it wasn’t as good a job as she wanted. She found a very good job elsewhere and reached manager status.

In looking back, I think much of that confidence came because we didn’t say, “Okay, there’s no excuse for behaving like that. You’re grounded!” Instead, we were willing to take the time to sit down and understand.

Notice how Karen’s father was able to rise above his concern about Karen’s outward behavior and seek to understand what was going on in her mind and heart. Only after doing this was he able to get at the real issue involved.

The argument between Karen and her parents was superficial. Karen’s behavior camouflaged the real concern. And as long as her parents focused only on her behavior, they never got to that concern. But then her father stepped out of the role of judge and became a genuinely concerned and affirming listener and friend. When Karen felt that her father really wanted to understand her, she began to feel safe in opening up and sharing on a deeper level. She herself may not even have realized what her own real concern was until she had someone who was willing to listen and give her the chance to get it out. Once the problem was clear and she really felt understood, Karen then wanted the guidance and direction her parents were able to give.

As long as we’re in the role of judge and jury, we rarely have the kind of influence we want. Perhaps you remember the story from the first chapter of this book of the man who “found his son again.” Do you remember how “overdrawn” that relationship was, how strained it was, how totally void of any authentic communication? (You may want to review that story here because it’s a wonderful example of the power of Habit 5.) That was another situation in which there were difficult, painful problems between parent and child, but there was no real communication. Only when the father stopped judging and really tried to understand his son was he able to begin to make a difference.

As long as we’re in the role of judge and jury, we rarely have the kind of influence we want.

In both these cases, parents were able to turn the situation around because they made the most significant deposit you can ever make into anyone’s Emotional Bank Account: They sought to understand.

Giving “Psychological Air”

One of the primary reasons seeking to understand is the first and most important deposit you can make is that it gives other people “psychological air.”

Try to remember a time when you had the wind knocked out of you and were gasping for air. At that moment, did anything else matter? Was anything as important as getting air?

That experience demonstrates why seeking to understand is so important. Being understood is the emotional and psychological equivalent of getting air, and when people are gasping for air—or for understanding—until they get it, nothing else matters. Nothing.

Sandra:

I remember one Saturday morning when Stephen was working at the office. I called him and said, “Stephen, come home fast. I’m going to be late for my appointment downtown, and I need help.”

“Why don’t you get Cynthia to help you?” he suggested. “She can take over, and you can be on your way.”

I replied, “She won’t help me at all. She’s totally uncooperative. I need you to come home.”

“Something must have happened in your relationship with Cynthia,” Stephen said. “Cure that relationship, and everything will work out.”

“Look, Stephen,” I said impatiently, “I don’t have time. I’ve got to go. I’m going to be late. Will you please just come home?”

“Sandra, it will take me fifteen minutes to get home,” he replied. “You can solve this thing in a matter of five or ten minutes if you’ll just sit down with her. Try to identify anything you’ve done that has in any way offended her. Then apologize. If you don’t find anything you’ve done, just say, ‘Honey, I’ve been rushing around so fast that I haven’t really paid attention to your concern. I can tell something is bothering you. What is it?’”

“I can’t think of a thing I’ve done to offend her,” I said.

“Well,” Stephen replied, “then just sit there and listen.”

So I went to Cynthia. At first she refused to cooperate. She was just kind of numb and stolid. She wouldn’t respond. So I said, “Honey, I’ve been rushing around and haven’t listened to you, and I sense something really important is bothering you. Would you like to talk about it?”

For a couple of minutes Cynthia refused to open up, but finally she blurted out, “It’s not fair! It’s not fair!” Then she talked about how she had been told she could have a sleep-over with her friends like her sister had had, and it never happened.

I just sat and listened. At that point I didn’t even attempt to solve the problem. But as she got out all her feelings, the air began to clear.

Suddenly she said, “Go on, Mom. Take off. I’ll take over.” She knew the challenge I had been going through—trying to handle all kinds of issues with the children when no one was being cooperative. But until she got that emotional air, nothing else mattered. Once she got that air, she was able to focus on the problem at hand and do what she knew she needed to do to help out.

Remember the phrase “I don’t care how much you know until I know how much you care.” People do not care about anything you have to say when they’re gasping for psychological air—to be understood, the first evidence of caring.

Think about it: Why do people shout and yell at each other? They want to be understood. They’re basically yelling, “Understand me! Listen to me! Respect me!” The problem is that the yelling is so emotionally charged and so disrespectful toward the other person that it creates defensiveness and more anger—even vindictiveness—and the cycle feeds on itself. As the interaction continues, the anger deepens and increases, and people end up not getting their point across at all. The relationship is wounded, and it takes far more time and effort to deal with the problems created by yelling at each other than simply practicing Habit 5 in the first place: exercising enough patience and self-control to listen first.

The deepest hunger of the human heart is to be understood.

Next to physical survival, our strongest need is psychological survival. The deepest hunger of the human heart is to be understood, for understanding implicitly affirms, validates, recognizes, and appreciates the intrinsic worth of another. When you really listen to another person, you acknowledge and respond to that most insistent need.

Knowing What Constitutes a “Deposit” in Someone’s Account

I have a friend who is happily married. For years her husband constantly said, “I love you,” and every so often he would bring her a single beautiful rose. She was delighted with this special communication of affection. It was a deposit in her Emotional Bank Account.

But she sometimes felt frustrated when he didn’t get to projects that she felt needed to be done around the home: hanging curtains, painting a room, building a cupboard. When he finally did get to these things, she responded as though he had suddenly made a hundred-dollar deposit into the account, compared to the ten-dollar deposits he was making whenever he gave her a rose.

This went on for years. Neither one of them really understood what was happening. And then one night as they were talking, she began to reminisce about her father, about how he was always working on projects around the house, repairing things that were broken, painting, or building something that would add to the value of their home. As she shared these things, she suddenly realized that to her, the things her father did represented a deep communication of his love for her mother. He was always doing things for her, helping her, making their home more beautiful to please her. Instead of bringing her roses, he planted rosebushes. Service was his language of love.

Without realizing it, our friend had transferred the importance of this form of communication to her own marriage. When her husband didn’t respond immediately to household needs, it became a huge but unrecognized withdrawal. And the “I love you’s” and the roses—though they were important to her—didn’t balance the account.

When they made this discovery, she was able to use her gift of self-awareness to understand the impact the culture in her own home had had on her. She used her conscience and creative imagination to look at her current situation with a new perspective. She used her independent will to begin to place greater value on her husband’s expressions.

In turn, her husband also engaged his four human gifts. He realized that what he had thought would be great deposits over the years were not as important to her as these little acts of service. He began communicating to her more often in this different language of love.

This story demonstrates another reason that seeking to understand is the first and foremost deposit you can make: Until you understand another person, you are never going to know what constitutes a deposit in his or her account.

Maria (daughter):

One time I planned an elaborate surprise birthday party for my husband, expecting him to be thrilled about it. He wasn’t! In fact, he hated it. He didn’t like a surprise party. He didn’t like a fuss being made over him. What he really would have liked was a nice, quiet dinner with me and a movie after. I have learned the hard way that it’s best to find out what’s really important to someone before trying to make a deposit.

It’s a common tendency to project our own feelings and motives on other people’s behavior. “If this means something to me, it must mean something to them.” But you never know what constitutes a deposit to others until you understand what is important to them. People live in their own private worlds. Your mission may be their minutia. It may not matter to them at all.

Each person needs to be loved in his or her own special way. The key to making deposits, therefore, is to understand—and to speak—that person’s language of love.

Because everyone is unique, each person needs to be loved in his or her own special way. The key to making deposits, therefore, is to understand—and to speak—that person’s language of love.

One father shared this experience of how understanding—rather than trying to “fix” things—worked in his family:

I have a ten-year-old daughter, Amber, who loves horses more than anything else in the world. Recently, her grandfather invited her to go on a daylong cattle drive. She was so excited. She was thrilled about the cattle drive and also about the fact that she would get to be with her grandfather, who also loves horses, all day long.

The night before the drive I came home from a trip to find Amber in bed with the flu. I said, “How are you doing, Amber?”

She looked at me and said, “I’m so sick!” And she started crying.

I said, “Boy, you must really feel bad.”

“It’s not that,” she said, sniffling. “I won’t be able to go on the cattle drive.” And she started crying again.

Through my mind went all of those things I thought a dad should say: “Oh, it will be fine. You can do it again. We’ll do something else instead.” But instead I just sat there and held her and didn’t say anything. I thought of times when I’d been bitterly disappointed. I just hugged her and felt her pain.

Well, the dam broke loose. She just bawled. She was shaking all over as I held her for a couple of minutes. And then it passed. She gave me a kiss on the cheek and said, “Thanks, Dad.” And that was it.

I thought again of all those wonderful things I could have said, all that advice I could have given. But she didn’t need that. She just needed someone to say, “It’s okay to be hurt, to cry when you’re disappointed.”

Notice how in both these situations people were able to make significant deposits into Emotional Bank Accounts. Because they sought to understand, they were able to speak their loved one’s language of love.

People Are Very Tender, Very Vulnerable Inside

Some years ago someone shared a beautiful expression with me anonymously through the mail. Reading this out loud slowly has moved audiences in incredible ways. It captures the essence of why Habit 5 is so powerful. I suggest you read it slowly and carefully, and attempt to visualize a safe setting where another person you care a lot about is really opening up.

Don’t be fooled by me. Don’t be fooled by the mask I wear. For I wear a mask. I wear a thousand masks—masks that I’m afraid to take off—and none of them is me. Pretending is an art that is second nature with me, but don’t be fooled.

I give the impression that I’m secure, that all is sunny and unruffled with me, within as well as without; that confidence is my name, and coolness is my game; that the waters are calm, and I’m in command and I need no one. But don’t believe it. Please don’t.

My surface may seem smooth, but my surface is my mask—my ever-varying and ever-concealing mask. Beneath lies no smugness, no coolness, no complacence. Beneath dwells the real me—in confusion, in fear, in loneliness. But I hide this; I don’t want anybody to know it. I panic at the thought of my weakness being exposed. That’s why I frantically create a mask to hide behind, a nonchalant sophisticated facade to help me pretend, to shield me from the glance that knows. But such a glance is precisely my salvation—my only salvation. And I know it. It’s the only thing that can liberate me from myself, from my own self-built prison walls, from the barriers I so painstakingly erect. But I don’t tell you this. I don’t dare. I’m afraid to.

I’m afraid your glance will not be followed by love and acceptance. I’m afraid that you’ll think less of me, that you’ll laugh, and that your laugh will kill me. I’m afraid that deep down inside I’m nothing, that I’m just no good, and that you’ll see and reject me. So I play my games—my desperate pretending games—with the facade of assurance on the outside and a trembling child within. And so begins the parade of masks, the glittering but empty parade of masks. And my life becomes a front.

I idly chatter with you in the suave tones of surface talk. I tell you everything that’s really nothing—nothing of what’s crying within me. So when I’m going through my routine, don’t be fooled by what I’m saying. Please listen carefully and try to hear what I’m NOT saying … what I would like to be able to say … what for survival I need to say, but I can’t say. I dislike the hiding. Honestly I do. I dislike the superficial phony games I’m playing. I’d really like to be genuine.

I’d really like to be genuine, spontaneous, and me; but you have to help me. You have to help me by holding out your hand, even when that’s the last thing I seem to want or need. Each time you are kind and gentle and encouraging, each time you try to understand because you really care, my heart begins to grow wings—very small wings, very feeble wings, but wings. With your sensitivity and sympathy, and your power of understanding, I can make it. You can breathe life into me. It will not be easy for you. A long conviction of worthlessness builds strong walls. But love is stronger than strong walls, and therein lies my hope. Please try to beat down those walls with firm hands, but with gentle hands, for a child is very sensitive, and I AM a child.

Who am I? you may wonder. I am someone you know very well. For I am every man, every woman, every child … every human you meet.

All people are very, very tender and sensitive. Some have learned to protect themselves from this level of vulnerability—to cover up, to pose and posture, to wear a safe “mask.” But unconditional love, kindness, and courtesy often penetrate these exteriors. They find a home in others’ hearts, and others begin to respond.

Creating a warm, caring, supportive, encouraging environment is probably the most important thing you can do for your family.

This is why it is so important to create a loving, nurturing environment in the home—an environment where it is safe to be vulnerable, to be open. In fact, the consensus of almost all experts in the field of marriage and family relations and child development is that creating such a warm, caring, supportive, encouraging environment is probably the most important thing you can do for your family.

And this does not mean just for little children. It also means for your spouse, your grandchildren, your aunts, uncles, nieces, nephews, cousins—everyone. The creation of such a culture—such an unconditionally loving and nurturing feeling—is more important than almost everything else put together. In a very real sense, to create such a nurturing culture is tantamount to having everything else put together.

Dealing with Negative Baggage

Creating such a culture is sometimes very difficult to do—especially if you’re dealing with negative baggage from the past and negative emotions in the present.

One man shared this experience:

When I met my future wife, Jane, she had a six-month-old boy named Jared. Jane had married Tom when they were both quite young, and neither of them had been ready for marriage by any stretch of the imagination. The realities and stresses of married life hit them hard. There was some physical violence involved, and he left her when she was about five months pregnant.

When I met Jane, Tom had filed for divorce and joint custody of the child he had never seen. It was a difficult, complicated situation. There were many bitter feelings. There was no communication between Jane and Tom whatever. The judge swayed heavily in favor of Jane.

After Jane and I married, I took a job that required us to move to another state. Every other month Tom would come and visit with Jared, and in alternating months we would make Jared available in California.

Things began to settle down in a way that seemed superficially okay. But I ended up doing most of the communicating between Jane and Tom. About one out of every three times that Tom would phone, Jane would hang up on him. Often Jane would leave before Tom got there for visitations, and I would be the one to see Jared off. Tom would frequently call me and say, “Should I talk to you about this, or should I talk to Jane?” It was very uncomfortable for me.

This spring, Tom called me and said, “Hey, Jared turns five in August, and then he will be legally able to fly by himself. Rather than my coming to visit out there where I sit in a hotel room with no car or friends, why don’t I pay for Jared to fly here?” I told him I would bring it up with Jane.

“No way!” she said emphatically. “Absolutely not! He’s just a little boy. He can’t even go to the bathroom on a plane by himself.” She wouldn’t even discuss it with me—and especially not with Tom. At one point she said, “Just leave it to me. I’ll handle it.” But as the months passed, nothing happened. Finally, Tom phoned me and said, “What’s happening? Is Jared going to fly down? What’s the deal?”

I was convinced that there was a lot of good potential in both Jane and Tom. I knew that if they could just be focused on doing the best thing for Jared, they could communicate and understand each other and work something out. But there were so many personal animosities and bitter feelings that they couldn’t see beyond them.

I tried to encourage them to have a discussion. I told them there would have to be strict guidelines to prevent verbal attacks and things of that nature. They both trusted me and agreed to do it. But I became increasingly nervous that I would not be able to facilitate that discussion because I was too close to it. I felt that one or both of them would end up hating me for one reason or another. In the past when Jane and I were having a discussion and I tried to look at an issue objectively, she would accuse me of taking “his” side. On the other hand, Tom felt that Jane and I had an agenda. I didn’t know what to do.

I finally decided to call Adam, a friend and coworker who facilitates the 7 Habits, and he agreed to talk with both of them. Adam taught them the principle of empathic listening. He taught them how to set aside their own autobiography and really listen to the words and feelings that were being expressed. After Jane shared some of her feelings, Adam said to Tom, “Now Tom, what did Jane just tell you?” He said, “She’s afraid of me. She’s afraid one day if I lose my temper I might slap Jared.” Jane was wide-eyed. She realized that Tom had been able to hear more than just her words. She said, “That’s exactly how I feel deep down in my heart. I’m worried that one day this man could easily lose it and hurt Jared.”

And after Tom expressed himself, Adam asked Jane, “What did Tom just say?” She replied, “He said, ‘I’m afraid of rejection. I’m afraid of being alone. I’m afraid no one cares at all.’” Even though she’d known him for fifteen years, Jane had no idea that Tom had been abandoned by his father when he was small and that he was determined not to do that to Jared. She didn’t realize how alienated he felt from her family after the divorce. For Tom it had been like being abandoned all over again. She began to realize how lonely Tom had been during the past five years. She began to understand how his declaration of bankruptcy a few years earlier made it impossible for him to get a credit card, so that when he came to visit Jared, he had no car. He was alone in a hotel room, with no friends and no transportation. And, she realized, we had just dropped Jared off.

Once Jane and Tom felt really understood and got down to the issues, they discovered that there was not a single thing on either of their lists that the other did not also want. They talked for three and a half hours, and the issue of visitation never even came up. Independently, they both told me later, “You know, this isn’t about Jared. It’s about trust between the two of us. Once we have this solved, the problem with Jared is a no-brainer.”

After this meeting with Adam, the atmosphere was much more relaxed and congenial. We all went to a restaurant together, and Jane said to Tom, “You know, it’s kind of tough with the kids here to talk about things, but when I come down next month for visitation, let’s take some time to talk.”

I thought, This is Jane talking? I had never heard her say anything like this before.

When we dropped Tom off at his hotel with Jared, Jane said, “What time are we picking Jared up tomorrow?”

He said, “Well, my shuttle to the airport leaves at 4:00 P.M.”

“Let us take you to the airport,” she said.

“That would be great, if you want to.”

“No problem,” she replied.

Again I was thinking, Wow! This is a major turnaround!

Two weeks later, Jane went down for visitation. One of her bones of contention had been that he never acknowledged what he had done to her. But when they had their talk, for the first time Tom apologized to her in great detail for everything. “I’m sorry for pulling your hair. I’m sorry for taking drugs. I’m sorry for walking out on you.” And this led her to say, “Well, I’m sorry, too.”

Following his visit with us, Tom began saying “thank you.” Tom had never said “thank you” for much of anything before. His conversations were now filled with thank-yous. And the week after his visit here, Jane received this brief letter from him:

Dear Jane,

I find it necessary to put in written word my thanks to you. We have shared so many ill feelings toward each other in the past, but the initial steps we took together last Saturday toward their resolution should be documented. And so … thank you.

Thank you for agreeing to meet with Adam. Thank you for sharing the things you shared. Thank you for listening to me. Thank you for the love from which we created our boy. Thank you for being his mother.

I mean it as sincerely as can be,

Tom

At the same time he sent me a letter.

Dear Mike,

I wanted to take a formal moment to thank you for putting Jane and me together with Adam. It has done more for my outlook toward my relationship with Jared and Jane than I can find the words for.…

Your desire to do what’s right both now and in past years is quite commendable. Without your good offices, there is no telling how ugly things would have gotten between Jane and me.…

My deepest appreciation,

Tom

When we received these letters, we were stunned. And in the phone conversations that followed, Jane said, “We talked almost like giddy school kids.” The understanding, the letting go, the forgiving, was so unleashing.

So many good things are happening now. Jane even went so far as to say to me, “Maybe when Tom comes up here, we could let him use one of our cars.” I had thought about that many times, but I didn’t dare mention it for fear of being accused of taking his side. I thought her attitude would be, “How dare you! You’re trying to accommodate the enemy.” But now she is recommending it. She even said, “What would you think about letting Tom stay in our spare room to help with his costs?” And I thought, Is this really Jane? It was a 180-degree turnaround.

I’m sure there will be challenges ahead, but I believe the groundwork has been laid. The tools for appropriate communication are there. There’s almost a feeling of deep respect now for one another and a genuine concern that I see in Jane and Tom for each other and for our kids.

It’s been a real challenge at times, but through it all it’s been crystal clear to me that anything less than this would make life worse for everyone.

Notice how Tom and Jane were able to rise above the hate, the blaming and accusing. They were able to diffuse the conflict and act based on principles instead of reacting to each other. How did they do that?

In seeking to understand each other, they both got psychological air. It freed them to stop fighting each other and to connect with their own inner gifts, particularly conscience and awareness. They became open, vulnerable. They were each able to acknowledge their part in the situation, to apologize, to forgive. And this healing, this cleansing, opened the door to more authentic relationships, to creating a synergy in which they were able to establish a better situation for their child, for themselves, and for everyone involved.

As you can see in this story—and in every other story in this chapter—not seeking to understand leads to judgment (usually misjudgment), rejection, and manipulation. Seeking to understand leads to understanding, acceptance, and participation. Obviously, only one of these paths is built on the principles that create quality family life.

Overcoming Anger and Offense

Probably more than any other single factor, what gets families off track and gets in the way of synergy is negative emotions, including anger and taking offense. Temper gets us into problems, and pride keeps us there. As C. S. Lewis said, “Pride is competitive in nature. Pride gets no pleasure out of having something, only out of having more of it than the next man.… It is the comparison that makes you proud: the pleasure of being above the rest. Once the element of competition has gone, pride has gone.”3 One of the most common and debilitating forms of pride is the need to be “right,” to have it your way.

Temper gets us into problems, and pride keeps us there.

Again, remember: Even if anger surfaces only one-tenth of 1 percent of the time, that will affect the quality of all the rest of the time because people are never sure when that raw nerve might be touched again.

I know of one father who was pleasant and agreeable most of the time, but on occasion his vicious temper was aroused. And this affected the quality of all the rest of the time because family members had to brace themselves for the possibility that it might happen again. They would avoid social situations for fear of embarrassment. They would walk around minefields throughout the day to avoid stepping on a raw nerve. They never became authentic or real or opened up. They never dared to give him feedback for fear that it would stir up the anger more than ever. And without feedback, this man lost all contact with what was really happening in his family.

When someone in the family becomes angry and loses control, the effects are so wounding, so intimidating, so threatening, so overpowering that others lose their bearings. They tend to either fight back, which only exacerbates the problem, or capitulate and give in to this win-lose spirit. And then even compromise is not likely. The more likely scenario is that people will separate and go their own ways, refusing to communicate at all about anything meaningful. They try to live with the satisfactions of independence, since interdependence seems too hard, too far off, and too unrealistic. And no one has the mind-set or the skill-set to go for it.

This is why it is so important when this kind of culture has developed for people to go deep within themselves. Then they can do the necessary work within to acknowledge their negative tendencies, to overcome them, to apologize to others, and to process their experiences so that gradually those labels are unfrozen and people can come to trust the basic structure, the basic relationship, again.

Taking offense is a choice. We may be hurt, but there is a big difference between being hurt and taking offense.

Of course, some of the most important inner work is prevention work. It includes making up our minds not to say or do those things we know will offend and learning to overcome our anger or to express it at better times and in more productive ways. We need to be deeply honest with ourselves and realize that most anger is merely guilt overflowing when provoked by the weakness of another. We can also make up our minds not to be offended by others. Taking offense is a choice. We may be hurt, but there is a big difference between being hurt and taking offense. Being hurt is having our feelings wounded—and it does smart for a time—but taking offense is choosing to act on that hurt by getting back, getting even, walking out, complaining to others, or judging the “offender.”

Most of the time offenses are unintentional. Even when they are intentional, we can remember that forgive—like love—is a verb. It’s the choice to move from reactivity to proactivity, to take the initiative—whether you’ve offended someone or been offended yourself—to go and make reconciliation. It’s the choice to cultivate and depend on an internal source of personal security so that we are not so vulnerable to external offenses.

And above all it’s the choice to prioritize the family, to realize that family is too important to let offenses keep family members from talking to one another, prevent grown brothers and sisters from going to family events, or weaken or break the intergenerational and extended family ties that provide such strength and support.

Interdependency is hard. It takes tremendous effort, constant effort, and courage. It’s much easier in the short run to live independently inside a family—to do your own thing, to come and go as you wish, to take care of your own needs, and to interact as little as possible with others. But the real joys of family life are lost. When children grow up with this kind of modeling, they think that is the way family is, and the cycle continues. The devastating effect of these cyclical cold wars is almost as bad as the destruction of the hot wars.

It’s often important to process negative experiences—to talk them through, resolve them, empathize with each other, and seek forgiveness. Whenever ugly experiences take place, you can unfreeze them by acknowledging your part in them and by listening empathically to understand how other people saw them and how they felt about them. In other words, by modeling vulnerability yourself, you can help others become vulnerable. The deepest bonding arises out of such mutual vulnerability. You minimize the psychic and social scarring, and clear the path to the creation of rich synergy.

Becoming a “Faithful Translator”

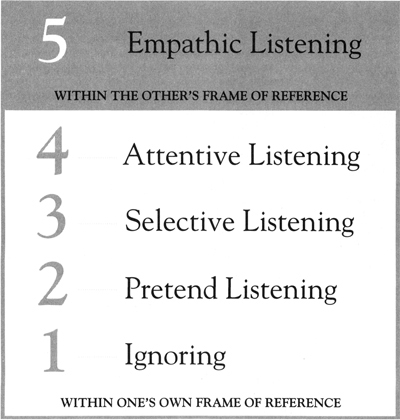

Really listening to get inside another person’s mind and heart is called “empathic” listening. It’s listening with empathy. It’s trying to see the world through someone else’s eyes. Of five different kinds of listening, it is the only one that really gets inside another person’s frame of reference.

You can ignore people. You can pretend to listen. You can listen selectively or even attentively. But until you listen empathically, you’re still inside your own frame of reference. You don’t know what constitutes a “win” for others. You don’t really know how they see the world, how they see themselves, and how they see you.

At one time I was in Jakarta, Indonesia, teaching the principle of empathic listening. As I looked out over the audience and saw many people wearing earphones, a thought came to me. I said, “If you want a good illustration of empathic listening, just think about what the interpreter or translator is doing right now through your earphones.” These translators were doing instantaneous translation, which meant that they had to be listening to what I was saying at the moment as well as restating what I had just said. It took incredible mental effort and concentration, and it required two translators to work in tandem, based on their level of fatigue. Both of those translators came up to me afterward and told me that what I had said was the finest compliment they had ever been given.

Even though you may be emotionally involved in a particular exchange with somebody, you can push your pause button and step outside of that emotion if you simply change the way you see your role—if you think of yourself as a “faithful translator.” Your job, then, is to translate and communicate back to the other person in new words the essential meaning (both verbal and nonverbal) of what that person communicated to you. In doing this you’re not taking a position yourself on what the person is talking about. You’re simply feeding back the essence of what he or she said to you.

One of the most effective ways to learn how to listen empathically is to simply change the way you see your role—to see yourself as a “faithful translator.”

Psychologist and author John Powell has said:

Listening in dialogue is listening more to meanings than to words.… In true listening, we reach behind the words, see through them, to find the person who is being revealed. Listening is a search to find the treasure of the true person as revealed verbally and nonverbally. There is the semantic problem, of course. The words bear a different connotation for you than they do for me.

Consequently, I can never tell you what you said, but only what I heard. I will have to rephrase what you have said, and check it out with you to make sure that what left your mind and heart arrived in my mind and heart intact and without distortion.

How to Do It: Principles of Empathic Listening

Now let’s go through a scenario together that will help us get at the heart of the understanding—or “faithful translator”—response.

Suppose for several days you’ve sensed that your teenage daughter is unhappy. When you’ve asked her what’s wrong, she’s replied, “Nothing. Everything’s okay.” But one night while you’re washing dishes together, she begins to open up.

“Our family rule that I can’t date until I’m older is embarrassing me to death. All my friends are dating, and that’s all they can talk about. I feel like I’m out of it. John keeps asking me out, and I have to keep telling him I’m not old enough. I just know he’s going to ask me to go to the party on Friday night, and if I have to tell him no again, he’ll give up on me. So will Carol and Mary. Everyone’s talking about it.”

How would you respond?

“Don’t worry about it, honey. No one is going to give up on you.”

“Just stick to your guns. Don’t worry about what others say and think.”

“Tell me what they’re saying about you.”

“When they talk about you like that, they’re really admiring you for your stand. What you’re feeling is normal insecurity.”

Any one of these might be a typical response, but not an understanding one.

“Don’t worry about it, honey. No one is going to give up on you.” This is an evaluating or judging response based on your values and your needs.

“Just stick to your guns. Don’t worry about what others say and think.” This is advising from your point of view or in terms of your needs.

“Tell me what they’re saying about you.” This response is probing for information you feel is important.

“When they talk about you like that, they’re really admiring you for your stand. What you’re feeling is normal insecurity.” This is interpreting what’s happening with your daughter’s friends and inside her as you see it.

Most of us either seek first to be understood, or if we do seek to understand, we are often preparing our response as we “listen.” So we evaluate, advise, probe, or interpret from our own point of view. And none of these is an understanding response. They all come out of our autobiography, our world, our values.

So what would an understanding response be?

First, it would attempt to reflect back what your daughter feels and says so that she feels you really understand. For example, you might say, “You feel kind of torn up inside. You understand the family rule about dating, but you also feel embarrassed when everyone else can date and you have to say no. Is that it?”

Then she might respond, “Yes, that’s what I mean.” And she might continue, “But the thing I’m really afraid of is that I won’t know how to act around boys when I do start dating. Everyone else is learning, and I’m not.”

Again, an understanding response would reflect back: “You feel somewhat scared that when the time comes, you won’t know what to do.”

She might say yes and go on further and deeper into her feelings, or she might say, “Well, not exactly. What I really mean is…” and she would go on to try to give you a clearer picture of what she’s feeling and facing.

If you look back at the other responses, you’ll see that none of them accomplishes the same results as the understanding response. When you give an understanding response, both of you gain a greater understanding of what she’s really thinking and feeling. You make it safe for her to open up and share. You make it comfortable for her to engage her own inner gifts to help deal with the concern. And you build the relationship, which will prove immensely helpful further down the road.

Let’s look at another experience that shows the difference between the typical and the empathic response. Consider the contrast in these two conversations between Cindy, a varsity cheerleader, and her mother. In the first, Cindy’s mother seeks first to be understood:

CINDY: Oh, Mom, I have some bad news. Meggie got dropped from the cheer squad today.

MOTHER: Why?

CINDY: She was caught in her boyfriend’s car on the school grounds, and he was drinking. If you get caught drinking on the school grounds, you get in big trouble. Actually, it’s not fair because Meggie wasn’t drinking. Just her boyfriend was drunk.

MOTHER: Well, Cindy, I think it serves Meggie right for keeping bad company. I’ve warned you that people will judge you by your friends. I’ve told you that a hundred times. I don’t see why you and your friends can’t understand. I hope that you learn a lesson from this. Life is tough enough without hanging around with someone like that guy. Why wasn’t she in class? I hope you were in class when all this was going on. You were, weren’t you?

CINDY: Mom, it’s okay! Mellow out. Don’t get so mad. It wasn’t me, it was Meggie. Gosh, all I wanted to do was tell you something about somebody else, and I get the ten-minute lecture on my bad friends. I’m going to bed.

Now look at the difference when Cindy’s mother seeks first to understand:

CINDY: Oh, Mom, I have some bad news. Meggie got dropped from the cheer squad today.

MOTHER: Oh, honey, you really seem upset.

CINDY: I feel so bad about it, Mom. It wasn’t her fault. It was her boyfriend’s. He’s a jerk.

MOTHER: Hmm. You don’t like him.

CINDY: I sure don’t, Mom. He’s always in trouble. She’s a good girl, and he drags her down. It makes me sad.

MOTHER: You feel he’s a bad influence on her, and that hurts you because she’s your good friend.

CINDY: I wish she’d drop this guy and go with someone nice. Bad friends get you in trouble.

Notice how this mother’s desire to understand was reflected in the way she responded to her daughter the second time. At that point she didn’t attempt to share her own experience or ideas—even though she may have had real value to add. She didn’t evaluate, probe, advise, or interpret. And she didn’t take Cindy on, although she may have disagreed with what her daughter seemed to be saying.

What she did was respond in a way that helped clarify her own understanding of what Cindy was saying and communicate that understanding back to Cindy. And because Cindy didn’t have to engage in a win-lose conversation with her mother, she was able to connect with her four gifts and come to a sense of the real problem on her own.

The Tip and the Mass of the Iceberg

Now, it’s not always necessary to reflect back in words what someone is saying and feeling in order to empathize. The heart of empathy is understanding how people see the situation and how they feel about it, and the essence of what they are trying to say. It’s not mimicking. It’s not necessarily summarizing. It’s not even attempting to reflect back in all cases. You may not need to say anything at all. Or perhaps a facial expression will communicate that you understand. The point is that you don’t get hung up on the technique of reflecting back but instead focus on truly empathizing and then allow that genuine, sincere emotion to drive your technique.

The problem comes when people think the technique is empathy. They mimic, use the same phrases repeatedly, and rephrase what others say in ways that seem manipulative or insulting. It’s like the story about the serviceman who was complaining to the chaplain about how much he hated army life.

The chaplain responded, “Oh, you don’t like army life.”

‘“Yeah,” said the serviceman. “And that C.O.! I couldn’t trust him as far as I could throw him.”

“You just feel that you couldn’t trust a C.O. as far as you could throw him.”

“Yeah. And the food—it’s so plain!”

“You feel that the food is really plain.”

The technique of empathic listening is just the tip of the iceberg. The great mass of the iceberg is a deep and sincere desire to truly understand.

“And the people—they’re so low-caliber.”

“You feel that the people are low-caliber.”

“Yeah … and what in the heck is wrong with the way I’m saying it anyway?”

It may be good to practice the skill. It may even increase the desire. But always remember that the technique is just the tip of the iceberg. The great mass of the iceberg is a deep and sincere desire to truly understand.

That desire is ultimately based on respect. This is what keeps empathic listening from becoming just a technique.

If this sincere desire to understand isn’t there, efforts to empathize will be sensed as manipulative and insincere. Manipulation means that the real motive is hidden even though good techniques are being used. When people feel manipulated, they are not committed. They may say “yes,” but they mean “no”—and it will be evidenced in their behavior later on. Pseudodemocracy eventually shows its true colors. And when people feel manipulated, a major withdrawal takes place, and your next efforts—even though sincere—will be perceived as another form of manipulation.

When you’re willing to acknowledge the true motive behind your methods, then truthfulness and sincerity replace manipulation. Others may not agree or go along, but at least you have been forthright. And nothing baffles a person who is full of tricks and duplicity more than simple, straightforward honesty on the part of another.

Based on respect and a sincere desire to understand, responses other than “reflective responses” can also become empathic. If someone were to ask you, “Where’s the rest room?” you wouldn’t just respond, “You’re really hurting.”

There are also times when, if you really understand, you can sense that someone wants you to probe. They want the additional perspective and insight your questions are based on. This might be compared to visiting a doctor. You want the doctor to probe, to ask about your symptoms. You know that the questions are based on expert knowledge and are necessary in order to give a proper diagnosis. So in this case probing becomes empathic rather than controlling and autobiographical.

When you sense that someone really wants you to ask questions to draw them out, you might consider questions such as these:

What are your concerns?

What is truly important to you?

What values do you want to preserve the most?

What are your most pressing needs?

What are your highest priorities in this situation?

What are the possible unintended consequences of such an action plan?

These kinds of questions can be combined with reflective statements such as:

I sense your underlying concern is …

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I sense that …

I’m trying to see it from your point of view, and what I sense is …

What I hear you saying is …

You feel that …

I sense you mean …

In the right situation any of these questions and phrases could show an attempt to achieve understanding or empathy. The point is that the attitude or desire is what must be cultivated first and foremost. The technique is secondary and flows out of the desire.

Empathy: Some Questions and Guidelines

As you work on Habit 5, you may be interested in the answers to some of the questions other people have asked over the years.

Is empathy always appropriate? The answer is “yes!” Without exception, empathy is always appropriate. But reflecting back, summarizing, and mirroring are sometimes extremely inappropriate and insulting. They may even be perceived as manipulation. So remember the heart of the matter is a sincere desire to understand.

What can you do if the other person doesn’t open up? Remember that 70 to 80 percent of all communication is nonverbal. In this sense you cannot not communicate. If you truly have an empathic heart, a heart that desires to understand, you will always be reading the nonverbal cues. You’ll be noticing body and face language, tone of voice, and context. Voice inflection and tone are the keys to discerning the heart on the phone. You’ll be attempting to discern the spirit and heart of another, so don’t force it. Be patient. You may even sense that you need to apologize or make restitution for some wrongdoing. Act on that understanding and do it. In other words, if you sense that the Emotional Bank Account is overdrawn, act on that understanding and make the appropriate deposits.

Remember that 70 to 80 percent of all communication is nonverbal. If you truly have an empathic heart, you will always be reading the nonverbal cues.

What are other expressions of empathy besides mirroring, summarizing, and reflecting techniques? Again, the answer is to do what the mass of the iceberg tells you—what your understanding of the person, the need, and the situation direct you toward. Sometimes total silence is empathic. Sometimes asking questions or using expert knowledge showing conceptual awareness is empathic. Sometimes a nod or a single word is empathic. Empathy is a very sincere, nonmanipulative, flexible, and humble process. You realize you’re on sacred ground and that the other person is perhaps even a little more vulnerable than you.

You may also find these guidelines helpful:

• The higher the trust level, the more you can easily move in and out of empathic and autobiographical responses—particularly between reflecting and probing. Negative and positive energy is often, though not always, a key indicator of the level of trust.

• If the trust is very high, you can be extremely candid and efficient with each other. But if you are attempting to rebuild trust or if it is somewhat shaky and the person won’t risk vulnerability, then you need to stay longer and with more patience in the empathic mode.

• If you’re not sure that you understand or if you’re not sure the other feels understood, then say that and try again.

• Just as you come from the depth of the iceberg under the water, learn to listen to the depth of the iceberg inside the other person. In other words, focus primarily on the underlying meaning, which is usually found more in feeling and emotion than in content or the words the person is using. Listen with the eyes and with the “third ear”—the heart.

• The quality in a relationship is perhaps the factor that most determines what is appropriate. Remember that relationships in the family require constant attention because the expectation of being emotionally nurtured and supported is constant. This is where people get into trouble—when they take others, particularly their loved ones, for granted and treat a stranger at the door better than the dearest people in their lives. There must be constant effort in the family to apologize, to ask for forgiveness, to express love, appreciation, and the valuing of others.

• Read the context, the environment, the culture so that the technique you use is not interpreted differently from what you intended. Sometimes you have to be very explicit by saying, “I’m going to try to understand what you mean. I am not going to evaluate, agree, or disagree at all. I am not going to try to ‘figure you out.’ I want to understand only what you want me to understand.” And that understanding often comes only when you also understand the “bigger picture.”

When you are truly empathizing, you are also understanding what’s going on in the relationship and in the nature of the communication taking place between you—not just in the words the other person is attempting to communicate. You are empathic about the whole context as well as the meaning that is being communicated. And then you act based on that larger empathic understanding.

For instance, if the entire history of the relationship is one of judging and evaluation, the very effort to empathize will probably be seen in that context. To change the relationship will probably require apologizing and deep interior work to make sure one’s attitude and behavior are congruent with that apology, and then being open and sensitive to opportunities to show understanding.

I remember one time when Sandra and I had been on our son’s case for several weeks regarding his schoolwork. One evening we asked him if he wanted to go to dinner with us as a kind of special date. He said he wanted to go and asked who else was going. We said, “No one else. This is just a special time with you.”

He then said that he didn’t want to go. We talked him into it, but there was very little openness in spite of our best efforts to show understanding. Near the end of the dinner we began talking about another issue that was indirectly related to schoolwork, and the emotional energy was such that it drove us into the sensitive subject and caused bad feelings and further defensiveness on everyone’s part. Later, when we apologized, this son told us, “This is why I didn’t want to go to dinner.” He knew it would be another judgment experience. It took us some time to make enough deposits so that he trusted the relationship and became open again.

One of the greatest things we’ve learned in this area is that mealtimes should always be happy, pleasant occasions for eating, sharing pleasant talk, and learning—sometimes even serious discussions about various intellectual or spiritual topics—but never a place for disciplining, correcting, or judging. When people are extremely busy, they may be with their family only at mealtimes, and they therefore try to take care of all important family matters then. But there are other, better times to handle these things. When mealtimes are pleasant and devoid of judgment or instruction, people look forward to them and to being together. It is well worth the careful planning and considerable discipline it takes to preserve the happiness and pleasantness of mealtimes and to make dinner a time when family members enjoy one another and feel relaxed and emotionally safe.

When relationships are good—and both parties are genuinely understanding—people can often rapidly communicate with unusual candor. Sometimes just a few nods or an “uh-huh” is sufficient. In these situations people can cover great territory rapidly with each other. An outsider, watching this without understanding the quality of the relationship and the larger context, might observe that there was no reflective listening or understanding or empathy taking place at all, when in fact it was deeply empathic and very efficient.

Sandra and I were able to achieve this level of communication in our own marriage on that sabbatical in Hawaii. Through the years, we have fallen back into old ways from time to time. But we find that by working at it, we are able to regain it fairly rapidly. So much depends on the amount of emotion being generated, the nature of the subject, the time of the day, the level of our personal fatigue, and the nature of our mental focus.

Many people struggle with this iceberg approach to empathy because it’s not as easy as skill development. It requires a great deal more internal work, and it takes more of an inside-out approach. With skill development you can get better just by practicing.

The Second Half of the Habit

“Seek first to understand” does not mean seek only to understand. It doesn’t mean that you bag your role to teach and influence others. It simply means that you listen and understand first. And as you can see in the examples given, this is actually the key to influencing others. When you are open to their influence, you’ll find you almost always have greater influence with them.

Now we come to the second half of the habit —“seek to be understood.” This has to do with sharing the way you see the world, with giving feedback, with teaching your children, with having the courage to confront with love. And when you attempt to do any of these things, you can readily see another very practical reason for seeking first to understand: When you really understand someone, it’s much easier to share, to teach, to confront with love. You know how to speak to others in the language they understand.

One woman shared this experience:

For a long time in our marriage, my husband and I did not see eye to eye on spending. He would want to buy things I felt were unnecessary and expensive. I couldn’t seem to explain to him the pain I felt as the debt kept mounting and we had to spend more and more of our income on interest and credit card bills.