HABIT 6

SYNERGIZE

A friend of mine shared an insightful experience he had with his son. As you read it, think about what you might have done in his situation.

After one week of practice, my son told me that he wanted to quit the high school basketball team. I told him that if he quit basketball, he would just keep quitting things all of his life. I told him how I had wanted to quit things when I was young, but I didn’t, and that made a dramatic difference in my life. I also told him that all our other sons had been basketball players and that the hard work and cooperation involved in being on the team helped them all. I was confident it would help him, too.

My son didn’t seem to want to understand me at all. With choked emotion he replied, “Dad, I’m not my brothers. I’m not a good player. I’m tired of being harassed by the coach. I have other interests besides basketball.”

I was so upset that I walked away.

For the next two days I felt frustrated each time I thought of this son’s foolish and irresponsible decision. I had a fairly good relationship with him, but it upset me to think that he cared so little about my feelings in this matter. Several times I tried to talk to him, but he simply would not listen.

Finally, I began to wonder just what had led him to make the decision to quit. I determined to find out. At first he didn’t even want to talk about it, so I asked him about other things. He would answer “yes” or “no” to my small talk, but he wouldn’t say any more than that. After some time he began to get teary-eyed, and he said, “Dad, I know you think you understand me, but you don’t. No one knows how rotten I feel.”

I replied, “Pretty tough, huh?”

“I’ll say it’s tough! Sometimes I don’t even know if it’s all worth it.”

He then poured his heart out. He told me many things I had not known before. He expressed his pain at constantly being compared to his brothers. He said his coach expected him to play ball as well as his brothers. He felt that if he went down a different path and blazed a new trail, the comparisons might end. He said he felt I favored his brothers because they brought me more glory than he could. He also told me about the insecurities he felt—not only in basketball but in all areas of his life. And he said he felt that he and I had somehow lost touch with each other.

I have to admit that his words humbled me. I had the feeling that what he said about the comparisons with his brothers was true and that I was guilty. I acknowledged my sorrow to him and—with much emotion—apologized. But I also told him that I still thought he would benefit greatly from playing ball. I told him that the family and I could work together to make things better for him if he wanted to play. He listened with patience and understanding, but he would not budge from his decision to quit the team.

Finally, I asked him if he liked basketball. He said he loved basketball but disliked all the pressure associated with playing for the high school team. As we talked, he said that what he would really like to do was play for the church team. He explained that he just wanted to have fun playing, not try to conquer the world. As he talked, I found myself feeling good about what he was saying. I admit I still felt a little disappointed that he wouldn’t be on the school team, but I was glad that at least he still wanted to play.

He started telling me the names of the guys on the church team, and as he talked, I could sense his excitement and interest. I asked him when the church team played games so that I could attend. He told me he wasn’t sure, and then he added, “But we need to get a coach or they won’t even let us play at all.”

At that point, almost by magic, something shot between us. A new idea came into both of our minds at the same time. Almost in unison we said, “I/You could coach the church team!”

All of a sudden my heart felt light as I thought about how much fun it would be to coach the team and have my son as one of the players.

The weeks that followed were among the happiest of my athletic experiences. And they provided some of my most memorable experiences as a father. Our team played for the sheer joy of playing. Oh, sure, we wanted to win and we did get a few victories, but no one was under pressure. And my son—who had hated to have the high school coach shout at him—would beam each time I would shout, “Way to go, son! Way to go! Good shot, son! Nice pass!”

That basketball season transformed the relationship between my son and me.

This story captures the essence of Habit 6—synergy—and of the Habits 4, 5, and 6 process that creates it.

Notice how this father and son at first seemed to be locked in a win-lose situation. The father wanted his son to play ball. His motives were good. He thought that playing ball would be a long-term win for his son. But the son felt differently. Playing high school ball wasn’t a win for him; it was a lose. He was always being compared to his brothers. He didn’t like dealing with the pressure. It seemed to be “your way” or “my way.” Whatever decision was made, someone was going to lose.

But then this father made an important shift in his thinking. He sought to understand why this wasn’t a win for his son. As they talked, they were able to get past the positioning and into the real issues. Together they came up with a better way, an entirely new solution that was a win for both. And that’s what synergy is all about.

Synergy—the Summum Bonum of All the Habits

Synergy is the summum bonum—the supreme or highest fruit—of all the habits. It’s the magic that happens when one plus one equals three—or more. And it happens because the relationship between the parts is a part itself. It has such catalytic, dynamic power that it affects how the parts interact with one another. It comes out of the spirit of mutual respect (win-win) and mutual understanding in producing something new—not in compromising or meeting halfway.

A great way to understand synergy is through the metaphor of the body. The body is more than just hands and arms and legs and feet and brain and stomach and heart all thrown together. It’s a miraculous, synergistic whole that can do many wonderful things because of the way the individual parts work together. Two hands, for example, can do far more together than both hands can do separately. Two eyes working together can see more clearly, with greater depth perception, than two eyes working separately. Two ears working together can tell sound direction, which is not the case with two unconnected ears. The whole body can do far more than all the individual parts could do on their own, added up but unconnected.

So synergy deals with the part between the parts. In the family, this part is the quality and nature of the relationship between people. As a husband and wife interact, or as parents interact with children, synergy lies in the relationship between them. That’s where the creative mind is—the new mind that produces the new option, the third alternative.

You might even think of this part as a third person. The feeling of “we” in a marriage becomes more than two people; it’s the relationship between the two people that creates this third “person.” And the same is true with parents and children. The other “person” created by the relationship is the essence of the family culture with its deeply established purpose and principle-centered value system.

In synergy, then, you have not only mutual vulnerability and the creation of shared vision and values, new solutions, and better alternatives, but you also have a sense of mutual accountability to the norms and values built into those creations. Again, this is what puts moral or ethical authority into the culture. It encourages people to be more honest, to speak with more candor, and to have the courage to deal with the tougher issues rather than trying to escape or ignore them or avoid being with people so as to minimize the likelihood of having to deal with such issues.

This “third person” becomes something of a higher authority, something that embodies the collective conscience, the shared vision and values, the social mores and norms of the culture. It keeps people from being unethical or power hungry, or from borrowing strength from position or credentials or educational attainment or gender. And as long as people live with regard to this higher authority, they see things such as position, power, prestige, money, and status as part of their “stewardship”—something they are entrusted with, responsible for, accountable for. But when people do not live in accordance with this higher authority and become a law unto themselves, this sense of a “third person” disintegrates. People become alienated, wrapped up in ownership and self-focus. The culture becomes independent rather than interdependent, and the magic of synergy is gone.

The key ultimately lies in the moral authority of the culture—to which everyone is accountable.

Synergy Is Risky Business

Because it’s stepping out into the unknown, the process of creating synergy can sometimes be near chaos. The “end in mind” you begin with is not your end, your solution. It’s moving from the known to the unknown and creating something entirely new. And it’s building relationships and capacity in the process. So you don’t go into the situation seeking your own way. You go in not knowing what’s going to come out of it, but knowing that it’s going to be a lot better than anything you brought into it.

Synergy is the magic moment of mutual vulnerability. You don’t know what’s going to happen. You’re at risk.

And this is risky business—an adventure. This is the magic moment of mutual vulnerability. You don’t know what’s going to happen. You’re at risk.

This is why the first three habits are so foundational. They enable you to develop the internal security that gives you the courage to live with this kind of risk. As paradoxical as it sounds, it takes a great deal of confidence to be humble. It takes a great deal of internal security to afford the risk of being vulnerable. But when people have the confidence and the kind of principle-based internal security that gives birth to humility and vulnerability, they then cease being a law unto themselves. Instead, they become conduits of exchanging insights. And in that very exchange is the dynamic that unleashes creative powers.

Truly, nothing is more exciting and bonding in relationships than creating together. And Habits 4 and 5 give you the mind-set and the skill-set to do it. You have to think win-win. You have to seek first to understand and then to be understood. In a sense you have to learn to listen with the third ear to create the third mind and the third alternative; in other words, you have to listen heart to heart in genuine respect and empathy. You have to reach the point where both parties are open to influence, teachable, humble, and vulnerable before the third mind that is the part between the two minds can become creative and produce alternatives and options that neither had considered initially. This level of interdependence requires two independent persons who recognize the interdependent nature of the circumstance, issue, problem, or need so that they can choose to exercise those interdependent muscles that enable synergy to happen.

Truly, Habit 6 is the summum bonum of all the habits. It’s not transactional cooperation where one plus one equals two. It’s not compromise cooperation where one plus one equals one and a half. And it’s not adversarial communication or negative synergy where more than half the energy is spent in fighting and defending so that one plus one equals less than one.

Synergy is a situation in which one plus one equals at least three. It is the highest, most productive and satisfying level of human interdependence. It represents the ultimate fruit on the tree. And there is no way to get that fruit unless the tree has been planted and nurtured and becomes mature enough to produce it.

The Key to Synergy: Celebrate the Difference

The key to creating synergy is in learning to value—even celebrate—the difference. Going back to the metaphor of the body, if the body were all hands or all heart or all feet, it could never work the way it does. The very differences enable it to accomplish so much.

A member of our extended family shared this powerful story of how she came to value the difference between her and her daughter:

When I turned eleven, my parents gave me a beautiful edition of a great classic. I read those pages lovingly, and when I turned the last one, I wept. I had lived through them.

Carefully, I kept the book for years, waiting to give it to my own daughter. When Cathy was eleven, I presented the book to her. Very pleased by her gift, she struggled through the first two chapters, then deposited it on her shelf where it remained unopened for months. I was deeply disappointed.

For some reason I had always supposed that my daughter would be like me, that she would like to read the same books I read as a girl, that she would have a temperament somewhat similar to mine, and that she would like what I liked.

“Cathy is a charming, bubbly, quick-to-laugh, slightly mischievous girl,” her teachers told me. “She’s fun to be around,” said her friends. “She’s excited about life, quick to seek humor everywhere, a sensitive soul,” said her father.

“This is really hard for me,” I said to my husband one day. “Her interminable zest for activities, her insatiable desire to ‘play,’ her ever-bubbling laughing and joking, are overwhelming to me. I’ve never been like that.”

Reading had been the singular joy of my preteen years. In my mind I knew I was wrong to be disappointed in the difference between us, but in the recesses of my heart I was. Cathy was something of an enigma to me, and I resented it.

Those unspoken feelings pass quickly to a child. I knew she would sense them and they would hurt her, if they hadn’t already. I agonized that I could be so uncharitable. I knew my disappointment was senseless, but as dearly as I loved this child, it did not change my heart.

Night after night when all were sleeping and the house was dark and quiet, I prayed for understanding. Then as I lay in bed one morning, very early, something happened. Quickly passing through my mind, in just seconds, I saw a picture of Cathy as an adult. We were two adult women, arms linked, smiling at each other. I thought of my own sister and how different we were. Yet I would never have wished that she be like me. I realized that Cathy and I would both be adults someday, just like my sister and me. And dearest friends do not have to be alike.

The words came to mind, “How dare you try to impose your personality on her. Rejoice in your differences!” Although it lasted but seconds, this flash, this reawakening, changed my heart when nothing else could.

My thankfulness, my gratitude, was renewed. And my relationship with my daughter took on a whole new dimension of richness and joy.

Notice how initially this woman assumed that her daughter would be like her. Notice how this assumption caused her frustration and blinded her to her daughter’s precious uniqueness. Only when she learned how to accept her daughter as she was and to rejoice in their differences was she able to create the rich, full relationship she wanted to have.

And this is the case in every relationship in the family.

One day I was presenting a seminar dealing with right and left brain differences to a company in Orlando, Florida. I called the seminar “Manage from the Left, Lead from the Right.” During the break, the president of the company came up to me and said, “Stephen, this is intriguing, but I have been thinking about this material more in terms of its application to my marriage than to my business. My wife and I have a real communication problem. I wonder if you would have lunch with the two of us and just kind of watch how we talk to each other.”

“Let’s do it,” I replied.

As the three of us sat down together, we exchanged a few pleasantries. Then this man turned to his wife and said, “Now, honey, I’ve invited Stephen to have lunch with us to see if he can help us in our communication with each other. I know you feel I should be a more sensitive, considerate husband. Can you give me something specific you think I ought to do?” His dominant left brain wanted facts, figures, specifics, parts.

“Well, as I’ve told you before, it’s nothing specific. It’s more of a general sense I have about priorities.” Her dominant right brain was dealing with sensing and with the gestalt, the whole, the relationship between the parts.

“What do you mean, ‘a general sense about priorities’? What is it you want me to do? Give me something specific that I can get a handle on.”

“Well, it’s just a feeling.” Her right brain was dealing in images, intuitive feelings. “I just don’t think our marriage is as important to you as you tell me it is.”

“What can I do to make it more important? Give me something concrete and specific to go on.”

“It’s hard to put into words.”

At that point, he just rolled his eyes and looked at me as if to say, Stephen, could you endure this kind of dumbness in your marriage?

“It’s just a feeling,” she said, “a very strong feeling.”

“Honey,” he said to her, “that’s your problem. And that’s the problem with your mother. In fact, it’s the problem with every woman I know.”

Then he began to interrogate her as though it were some kind of legal deposition.

“Do you live where you want to live?”

“That’s not it,” she said with a sigh. “That’s not it at all.”

“I know,” he replied with forced patience. “But since you won’t tell me exactly what it is, I figure the best way to find out what it is, is to find out what it is not. Do you live where you want to live?”

“I guess.”

“Honey, Stephen’s here for just a few minutes to try to help us. Just give me a quick ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer. Do you live where you want to live?”

“Yes.”

“Okay, that’s settled. Do you have the things you want to have?”

“Yes.”

“All right. Do you do the things you want to do?”

This went on for a little while, and I could see I wasn’t helping at all, so I intervened and said, “Is this kind of how it goes in your relationship?”

“Every day, Stephen,” he replied.

“It’s the story of our marriage,” she said.

I looked at the two of them, and the thought crossed my mind that they were two half-brained people living together. “Do you have any children?” I asked.

“Yes, two.”

“Really?” I asked incredulously. “How did you do it?”

“What do you mean, how did we do it?”

“You were synergistic!” I said. “One plus one usually equals two. But you made one plus one equal four. Now that’s synergy. The whole is greater than the sum of the parts. So how did you do it?”

“You know how we did it!” he replied.

“You must have valued the differences!” I exclaimed.

Now contrast that experience with that of some friends of ours who were in the same situation—except their roles were reversed. The wife said:

My husband and I have very different thinking styles. I tend to be more logical and sequential—more “left brained.” He tends to be more “right brained,” to look at things more holistically.

When we were first married, this difference created something of a problem in our communication. It seemed that he was always scanning the horizon, looking at new alternatives, new possibilities. It was easy for him to change course midstream if he thought he saw a better way. On the other hand, I tended to be diligent and precise. Once we had a clear direction, I would work out the details, burrow in, and stay the course, no matter what.

This gave rise to a number of challenges when it came to making decisions together on everything from setting goals to buying things to disciplining the children. Our commitment to each other was very solid, but we were both caught up in our own ways of thinking and it seemed like a lot of work to try to make decisions together.

For a time we tried to separate areas of responsibility. In doing the budget, for example, he would do much of the long-range planning, and I would keep the records. And this proved to be helpful. We were both contributing to the marriage and family in our own areas of strength.

But when we discovered how to use our differences to create synergy, we came to a new level of richness in our relationship. We discovered that we could take turns listening to each other and have our eyes opened to a whole new way of seeing things. Instead of approaching problems from “opposite” sides, we were able to come together and approach problems with shared and much greater understanding.

This opened the door to all kinds of new solutions to our problems. It also gave us something wonderful to do together. When we finally realized that our differences were parts of a greater whole, we began exploring the possibilities of putting those parts together in new ways.

We discovered that we love to write together. He goes for the big concepts, the holistic ideas and the right brain ways of teaching. I challenge and interact with him on the ideas, arrange the content, and do the wordsmithing. And we love it! This has brought us together in a whole new level of contribution. We’ve found that our togetherness is much better because of our differences rather than in spite of them.

Notice how both couples were dealing with right and left brain differences in thinking. In the first situation, these differences led to frustration, misunderstanding, and alienation. In the second, they led to a new level of unity and richness in the relationship.

How was the second couple able to get such positive results?

You must be able to say sincerely, “The fact that we see things differently is a strength—not a weakness—in our relationship.”

They learned how to value the difference and use it to create something new. As a result, they’re better together than they are alone.

As we said in Habit 5, everyone is unique. And that uniqueness, that difference, is the basis of synergy. In fact, the whole foundation of the biological creation of a family hinges on the physical differences between a man and a woman that produce children. And that physical creative power serves as a metaphor for other kinds of good things that can come as a result of differences.

It’s not enough to simply tolerate differences in the family. You can’t just accept differences. You can’t just diversify family functions to accommodate differences. To have the kind of creative magic we’re talking about, you must actually celebrate differences. You must be able to say sincerely, “The fact that we see things differently is a strength—not a weakness—in our relationship.”

From Admiration to Irritation

Ironically, often the very things that attract people to each other in the beginning of a relationship are the differences, the ways in which someone is delightfully, pleasantly, excitingly different. Yet as they get into the relationship, somehow admiration changes to irritation, and some of those differences are the very things that cause the greatest distress.

I remember coming home one night after having been away from meaningful communication with our young children for two or three days. I was feeling somewhat guilty about this lack of communication, and when I feel guilty, I tend to become a bit indulgent.

Because I was often away, Sandra had to compensate for my indulgence by coming on a bit too strong. Her toughness caused me to become a little softer. My increased softness caused her to become a little harder. Thus, the discipline system in our home was sometimes driven more by politics than by the consistent application of principles that create a beautiful family culture.

When I came home that night, I went to the top of the stairs and yelled, “Boys, are you there? How’s it going?”

One of the younger boys ran down the hall, looked up at me, and then shouted back to his brother, “Hey, Sean, he’s nice.” (In other words, “He’s in a good mood!”)

What I didn’t know was that these boys were in bed under threat of their lives. They had used every conceivable excuse to get up and keep playing and goofing off. That had gone on until my wife’s patience had come to an end. She had sent them to bed with a final command: “Now you boys stay in bed or else!”

So when they saw Dad’s car lights shine through the window, a new ray of hope was born. They thought, Let’s see what kind of mood Dad is in. If he’s in a good mood, we can get up and play some more. When I came into the house, they were waiting. The words, “Hey, Sean, he’s nice,” were their cue. We started wrestling around in the front room and having all kinds of fun.

Then out came Mom. With a mixture of frustration and anger in her voice, she shouted, “Are those kids still up?”

I quickly replied, “Hey, I haven’t seen much of them lately. I want to play with them for a little while.” Needless to say, she didn’t like my response, nor did I like hers. And there were the boys, watching Mom and Dad arguing right in front of them.

The problem was that we had not synergized on this issue and come up with agreements we were both willing to live with. I was too much a product of my moods and feelings, and I wasn’t consistent. I didn’t show respect for the fact that these boys were in bed and should have stayed in bed. But I also hadn’t seen them for some time. And a pertinent question was “How important is the bedtime rule anyway?”

The solution to this problem was not worked out immediately, but eventually we concluded that the bedtime rule wasn’t that important for our family—particularly as the children became teenagers. We felt that what were normal bedtimes for many families were important and fun family times for us. The kids would sit around and talk, eat, and laugh—particularly with Sandra, since I typically went to bed earlier. The thing that enabled that synergistic solution for our family was acknowledging the differences and allowing all of us to do what we individually and collectively felt strongly about.

Sometimes living with differences and appreciating other people’s uniqueness is hard. We tend to want to mold people in our own image. When we get our security from our opinions, to hear a different opinion—particularly from someone as close as our spouse or children—threatens that security. We want them to agree with us, to think the way we think, to go along with our ideas. But as someone once said, “When everybody thinks alike, nobody thinks very much.” Another said, “When two agree, one is unnecessary.” Without difference, there’s no basis for synergy, no option to create new solutions and opportunities.

The key is to learn to blend the best of them together in a way that creates something entirely new. You can’t have a delicious stew without diversity. You can’t have a fruit salad without diversity. It’s the diversity that creates the interest, the flavor, the new combination that puts together the best of all different things.

Over the years Sandra and I have come to recognize that one of the very best things about our marriage is our differences. We share an overarching commitment and value system and destination, but within that, we have great diversity. And we love it! Most of the time, that is. We count on each other’s different perspectives to increase our judgment, to help us make better decisions. We count on each other’s strengths to help compensate for our individual weaknesses. We count on each other’s uniqueness to give spice and flavor to our relationship.

We know we’re better together than we are alone. And we know that one of the primary reasons is that we are different.

Cynthia (daughter):

If you wanted advice about something, you’d go to Dad, and he’d give it to you. He’d say, “I’d do this.” And he’d outline everything.

But sometimes you didn’t want advice. You just wanted someone to say, “You’re the best. You’re the greatest. They should have chosen you as cheerleader [or class president or whatever] instead of that other girl.” You just wanted someone to be really supportive and loyal to you, no matter what. And that was Mom. In fact, she was so loyal, I was always afraid she was going to call whoever I was mad at and bawl them out and say, “Why are you being so rude to my daughter? Why don’t you ask her out?” or “Why didn’t you choose her to be the lead in the play?”

She thought we were the greatest. It wasn’t so much that she thought we were better than other kids, but she thought a lot of us. And we could feel that even though we knew she was prejudiced about us and usually exaggerated what we did. But it felt good to know that someone believed in you that much. And that’s what she instilled in us: “You can do anything. You will rise and accomplish your goals if you just stick with it. I believe in you, and you can do it.”

Somehow each of them taught us the best of what they were.

The Process in Action

Synergy is not just teamwork or cooperation. Synergy is creative teamwork, creative cooperation. Something new is created that was not there before and could not have been created without celebrating differences. Through deep empathic listening and courageous expressing and producing new insights, the third alternative is born.

Synergy is not just teamwork or cooperation. Synergy is creative teamwork, creative cooperation. Something new is created that was not there before.

Now you can apply Habits 4, 5, and 6 to create new third-alternative solutions in any family situation. In fact, I’d like to suggest that you try to do just that.

I’m going to share with you a real-life situation and ask you to engage your four human gifts to see how you would resolve it. I’ll interrupt this experience at points along the way and ask questions so that you can use your pause button and think through specifically how you could use your gifts and just what you would do. I suggest you take the time to think deeply about and answer each question before you continue reading.

My husband didn’t earn much money, but we were finally able to buy a small house. We were thrilled to have a home of our own even though the payments were such that we would just barely be able to stay financially solvent.

After living in the home for a month we became convinced that our front room looked shabby because of the threadbare couch that my husband’s mother had given us. We decided that although we couldn’t afford it, we had to have a new couch. We drove to a nearby furniture store and looked at the couches. We saw a beautiful Early American couch that was just what we wanted, but we were astonished at the high price. Even the least expensive couch was twice the price we had thought it would be.

The salesman asked us about our house. We told him, with some degree of pride, how much we loved it. Then he said, “How would that Early American couch look in your front room?”

We told him it would look grand. He suggested that it be delivered the following Wednesday. When we asked him how we could get it without any money, he assured us that would be no problem because they could defer the payments for two months.

My husband said, “Okay. We’ll take it.”

[Pause: Use your self-awareness and your conscience. Assuming you were the woman, what would you do?]

I told the salesman that we needed more time to think. [Notice how this woman used her Habit 1 proactivity to create a pause.]

“My husband replied, “What is there to think about? We need it now, and we can pay for it later.” But I told the salesman that we would look around and then maybe come back. I could tell my husband was upset as I took hold of his hand and began to walk away.

We walked to a little park and sat on a bench. He was still upset and hadn’t said a word since we left the store.

[Pause: Use your self-awareness and your conscience again. How would you handle this situation?]

I decided to let him tell me how he felt and to listen so that I could understand his feeling and thinking. [Notice the Habit 4 win-win thinking and the use of Habit 5.]

Finally, he told me that he felt embarrassed anytime anyone came to our home and saw that old couch. He told me that he worked hard and couldn’t see why we made so little money. He didn’t think it was fair that his brother and others got paid so much more than he did. He said that sometimes he felt he was a failure. A new couch would be a sign that he was okay.

His words sank into my heart. He almost convinced me that we should go back and get the couch. But then I asked him if he would listen while I told him my feelings. [Notice the use of the second half of Habit 5.] He said that he would.

I told him how proud I was of him and that to me he was the world’s greatest success. I told him how I could barely sleep at night sometimes because I was worried that we didn’t have enough money to pay the bills. I told him that if we bought that couch, in two months we’d have to pay for it—and we wouldn’t be able to do it.

He said that he knew that what I was saying was true, but he still felt bad that he could not live as well as all those around him.

[Pause: Use your creative imagination. Can you think of a third alternative solution?]

Somehow we got to talking about how we could make our front room more attractive without spending a lot of money. [Notice the beginning of Habit 6 synergy.] I mentioned that the local thrift store might have a couch that we could afford. He laughed and said, “They could have an Early American couch there that’s far more Early American than the one we’ve just seen.” I reached out and took his hand, and we sat there for a long moment just looking into each other’s eyes.

Finally, we decided to go over to the thrift store. We found a couch there that was mostly wood. The cushions were all detachable. They were terribly worn, but I didn’t think it would be too much trouble to re-cover them in some fabric that would match the colors of the room. We bought the couch for thirteen dollars and fifty cents and headed home. [Notice the use of conscience and independent will.]

The next week I enrolled in a furniture upholstery class. My husband refinished the wooden parts. Three weeks later we had a lovely Early American couch.

As time went by, we’d sit on those golden cushions and hold hands and smile. That couch was the symbol of our financial recovery. [Finally, notice the results.]

What kind of solutions did you come up with as you went through this experience? As you connected with your own gifts, you may even have come up with answers that would work for you better than the one this couple discovered.

Whatever solution you came up with, think about the difference it would make in your life. Think about the difference this couple’s synergy made in their lives. Can you see how they used their four gifts, how they created the pause that enabled them to act instead of react? Can you see how they engaged in the Habits 4, 5, and 6 process to come to a synergistic third-alternative solution? Can you see the value that was added to their lives as they developed their talents and created something beautiful together? Can you imagine the difference it will make each time they look at their couch and see something they bought with cash and worked together to beautify rather than something they bought on credit and are paying interest on every month?

One wife described living these habits in these words:

With Habits 4, 5, and 6, my husband and I are constantly seeking each other’s exploration. It’s like a ballet or dance of two dolphins—a very natural moving together. It has to do with mutual respect and trust, and the way these habits play out in day-to-day decisions—whether it’s huge decisions, like whose house we lived in after we were married, or what we should have for dinner. These habits themselves have become a habit between us.

The Family Immune System

This kind of synergy is the ultimate expression of a beautiful family culture—one that’s creative and fun, one that’s filled with variety and humor, one that has deep respect for every person and every person’s varied interests and approaches.

Synergy unleashes tremendous capacity. It gives birth to new ideas. It brings you together in new multidimensional ways, making huge deposits in the Emotional Bank Account because creating something new with someone else is enormously bonding.

It also helps you create a culture in which you can successfully deal with any family challenge you might face. In fact, you could compare the culture created by Habits 4, 5, and 6 to a healthy immune system in the body. It determines the family’s ability to handle whatever challenges are thrown at it. It protects family members so that when mistakes are made or when you get blindsided by some totally unexpected physical, financial, or social challenge, the family doesn’t get overcome by it. The family has the capacity to accommodate it and rise above it, to adapt—to deal with whatever life throws at it and to use it, learn from it, run with it, optimize it, and make the family stronger.

With this kind of immune system, you actually see “problems” differently. A problem becomes something of a vaccination. It triggers the immune system to produce antibodies so that you never get the full-blown disease. So you can take any problem in your family life—a problem in your marriage, a struggle with one of your teenage children, a layoff, an estranged relationship with an older brother or sister—and look at it as a potential vaccination. Undoubtedly it will cause some pain and perhaps a little scarring, but it can also trigger an immune response, the development of the capacity to fight.

Then, no matter what difficulties come along, the immune system can wrap its arms around that difficulty—that setback, that disappointment, that deep fatigue or whatever it may be that threatens family health—and turn it into a growth experience that makes the family more creative, more synergistic, more capable of solving problems and of dealing with any kind of challenge you may confront. So problems don’t discourage you; they encourage you to develop new levels of effectiveness and immunity.

The key to your family culture is how you treat the child that tests you the most.

Seeing problems as vaccinations gives new perspective to the way you see even the challenge of dealing with your most difficult child. It will build strength in you and in the entire culture as well. In fact, the key to your family culture is how you treat the child that tests you the most. When you can show unconditional love to your most difficult child, others know that your love for them is also unconditional. And that knowledge builds trust. So strive to be grateful for the most difficult child, knowing that the very challenge can build strength in you and in the culture as well.

When we come to understand the family immune system, we come to look upon small problems as reinoculations of the family body. They cause the immune system to kick in, and by properly communicating and synergizing around them, the family builds greater immunity so that other small problems are not blown out of proportion.

The reason AIDS is such a horrific disease is that it destroys the immune system. People don’t die of AIDS; they die of the other diseases that take over because they have a compromised immune system. Families do not die from a particular setback; they die because they have a compromised immune system. They have overdrawn Emotional Bank Accounts and no organizing processes to institutionalize—or build into the day-to-day processes and patterns of family life—the principles or the natural laws on which family is based.

A healthy immune system fortifies you against four “cancers” that are deadly to family life: criticizing, complaining, comparing, and competing. These cancers are the opposite of a beautiful family culture, and without a healthy family immune system, they can metastasize and spread their negative consuming energy throughout the family.

“You See It Differently. Good! Help Me Understand.”

Another way to look at this Habits 4, 5, and 6 culture is through the airplane metaphor. We said at the outset that we’re going to be off track 90 percent of the time, but we can read the feedback and get back on course.

“Family” is about learning the lessons of life, and feedback is a natural part of that learning. Problems and challenges give you feedback. Once you realize that each problem is asking for a response instead of just triggering a reaction, you start to learn. You become a learning family. You welcome challenges that test your capacity to synergize and to respond with higher levels of character and competence. You have differences, and you say, “You see it differently. Good! Help me understand.” You also draw upon the collective conscience, the moral or ethical nature of everyone in the family.

Once you realize that each problem is asking for a response instead of just triggering a reaction, you start to learn. You become a learning family.

But in order to do this, you have to get beyond the blaming and accusing. You have to get beyond the criticizing, complaining, comparing, and competing. You have to think win-win, seek to understand and be understood, and synergize. If you don’t, at best you’ll end up satisfying, not optimizing; cooperating, not creating; compromising, not synergizing; and, at worst, fighting or flighting.

You also have to live Habit 1. As one man said, “This process is magic! All it takes is character.” And so it does. It takes character to think win-win when you and your spouse feel differently about buying a car, when your two-year-old wants to wear pink pants and an orange shirt to the grocery store, when your teenager wants to come home at 3 A.M., when your mother-in-law wants to rearrange your house. It takes character to seek first to understand when you think you really know what someone’s thinking (you usually don’t), when you’re sure you have the perfect answer to the problem (you usually don’t), and when you have an important appointment you have to be at in five minutes. It takes character to celebrate differences, to look for third-alternative solutions, to work with the members of your family to create this sense of synergy in the culture.

That’s why proactivity is foundational. Only as you develop the capacity to act based on principles instead of reacting to emotion or circumstance and only as you recognize the priority of family and organize around it will you be able to pay the price that’s necessary to create this powerful synergy.

One father shared this experience:

As I thought about Habits 4, 5, and 6 and worked to develop them in our family, I came to feel that I needed to work on my relationship with my seven-year-old daughter, Debbie. She often reacted very emotionally, and when things didn’t go her way, she tended to run to her room and cry. It seemed that no matter what my wife and I did, it put her in a tailspin.

And her frustration led to our frustration. We found ourselves reacting to her and constantly getting on her. “Settle down! Stop crying! Go into your room until you’re under control!” And this negative feedback caused her to act up even more.

But one day as I was thinking about her, an insight came. My heart was touched as I realized that her emotional nature was a very special gift that would be a great source of strength to her in life. I had often seen her show unusual compassion for her young friends. She was always one to make sure that everyone’s needs were met, that no one was left out. She had a great heart and a wonderful ability to express love. And when she wasn’t in one of her emotional tailspins, her cheeriness was like tangible sunshine in our home.

I realized that her “gift” was a vital competency that could bless her whole life. And if I kept up this negative, critical approach, I was likely to snuff out what could become her greatest strength. The problem was that she didn’t know how to deal with all her emotions. What she needed was someone to hang in there with her, to believe in her, to help her work it out.

So the next time she lost it, I didn’t react. And when her inner storm had spent itself, we sat down together and talked about what it really takes to solve problems, to find alternatives that everyone feels good about. I realized that in order for her to be willing to remain in the process, she needed a few victories, so I consciously helped provide her with experiences where synergy really worked. And this enabled her to develop the courage and belief that if she pushed her own pause button and hung in there with us, it would pay off.

We still have our moments, but we have found that she is much more cooperative, much more willing to work things out. And I have found that when she does have her struggles, things work out much better if I hang in there with her and don’t let her run away. I don’t say, “You don’t run away.” I say, “Come over here. Let’s work through this and solve it together.”

Notice how this father’s insight and vision of his daughter’s true nature helped him to value her unique difference and to be proactive in working with her. And notice, too, how even young children can learn and practice Habits 4, 5, and 6.

Based on a number of variables, you may find yourself at different levels of proactivity at different times. The circumstances you’re in, the nature of the crisis, the strength of your resolve around a particular purpose or vision, the level of your physical, mental, and emotional fatigue, and the amount of sheer willpower you have all affect the level of proactivity you bring to a potentially synergistic experience. But when you can get all these things in line and you can value the difference, it’s amazing how much resourcefulness and energy and intuitive wisdom you can access.

You also have to live Habit 2. This is the leadership work. This is creating the unity that makes diversity meaningful. You have to have a destination because destination defines feedback. Some say that feedback is the “breakfast of champions.” But it isn’t. Vision is the breakfast. Feedback is the lunch. Self-correction is the dinner. When you have your destination in mind, then you know what feedback means because it lets you know whether you’re headed toward your destination or you’re off track. And even when you have to go to other places because of the weather, you can keep coming back so that eventually you will reach it.

Some say that feedback is the “breakfast of champions.” But it isn’t. Vision is the breakfast. Feedback is the lunch. Self-correction is the dinner.

You also need to live Habit 3. One-on-one bonding times give you the Emotional Bank Account to interact authentically and in synergistic ways with the members of your family. And weekly family times provide the forum for synergistic interaction.

You can see how interwoven these habits are, how they come together and reinforce one another to create this beautiful family culture we’ve been talking about.

Involve People in the Problem and Work Out the Solution Together

Another way of expressing Habits 4, 5, and 6 can be found in one simple idea: Involve people in the problem and work out the solution together.

We had an interesting experience with this in our own family some years ago. Sandra and I had read a great deal about the impact of television on the minds of children, and we had begun to feel that in many ways it was like an open sewage pipe right into our home. We had set up rules and guidelines to limit the amount of TV watching, but it seemed that there were always exceptions. The rules kept changing. We were constantly in the position of dispensing privileges and judgments, and we had grown weary of negotiating with the children. It had become a power struggle that occasionally caused feelings to flare in negative ways.

Although we agreed on the problem, we didn’t agree on the solution. I wanted to take an authoritarian approach inspired by an article I’d read about a man who actually threw the family TV set into the garbage! In some ways that kind of dramatic action seemed to demonstrate the message we wanted to send. But Sandra favored a more principle-based approach. She didn’t want the children to resent the decision, to feel it was not a win for them.

As we synergized together, we realized we were trying to decide how we could solve this problem for the children when what we needed to do was help them solve it for themselves. We decided to engage Habits 4, 5, and 6 on a family-wide basis. At our next family night we introduced the subject “TV—how much is enough?” Everyone’s interest was immediately focused because this was an important matter for all involved.

One son said, “What’s so bad about watching TV? There’s a lot of good stuff on. I still get my homework done. I can actually study while the TV is on. My grades are good, and so are everyone else’s. So what’s the problem?”

A daughter added, “If you’re afraid we’re going to be corrupted by TV, you’re wrong. We don’t usually watch bad shows. And if one is bad, we usually turn to another station. Besides, what’s shocking to you is not all that shocking to us.”

Another said, “If we don’t watch certain shows, we’re socially out of it. All the kids watch these shows. We even talk about them every day at school. These shows help us see how things really are in the world so that we don’t get caught up in all the dumb things that are going on.”

We didn’t interrupt the kids. They all had something to say about why they didn’t think we should make any drastic changes in our TV habits. As we listened to their concerns, we could see how deeply they were into their feelings about TV.

Finally, when their energy seemed spent, we said, “Now let us see if we really understand what you’ve just said.” And we proceeded to restate all we had heard and felt them say. Then we asked, “Do you feel that we truly understand your point of view?” They agreed that we did.

“Now we would like you to understand where we’re coming from.”

The response was not very favorable.

“You just want to tell us all the negative things people are saying about watching TV.”

“You want to pull the plug and take away our only escape from all the pressure we feel at school.”

We listened empathically and then assured them that this was not our intent at all. “In fact,” we said, “when we’ve gone over these articles together, we’re going to leave the room and let you kids decide what you feel we should do about watching TV.”

“You’re kidding!” they exclaimed. “What if our decision is different from what you want?”

“We’ll honor your decision,” we said. “All we ask is that you be in total agreement about what you recommend that we do.” We could see by the expressions on their faces that they liked the idea.

So, all together, we went over the information in the two articles we had brought to the meeting. The children sensed this material would be important in their upcoming decision, so they listened very attentively. We began by reading some shocking facts. One article said that the average television diet for a person between the ages of one and eighteen is six hours a day. If there is cable in the home, that increases to eight hours per day. By the time young Americans have graduated from school, they will have spent thirteen thousand hours in school and sixteen thousand hours in front of a television set. During that time they will have witnessed twenty-four thousand killings.1

We told the children that, as parents, those facts were scary to us and that when we watched as much TV as we did, it became by far the most powerful socializing force in our lives—more than education, more than time spent with the family.

We pointed out the discrepancy concerning TV program directors who claim there is no scientific evidence to link TV viewing to behavior and then quote evidence showing the powerful impact a twenty-second commercial has on behavior. Then we said, “Just think about how different you feel when you watch a television show and when you watch a commercial. When a thirty- to sixty-second commercial comes on, you know it’s an advertisement. You don’t believe a lot of what you see and hear. Your defenses are up because it’s advertising, it’s just hype, and we’ve all been burned by it again and again. But when you’re watching a show, your defenses are down. You become emotionally invested, vulnerable. You’re letting images come into your head, and you’re not even thinking about it. You’re just absorbing it. Of course, the commercials impact us in spite of our defensiveness. Can you imagine the impact the regular programs are having on us when we’re in a much more receptive posture?”

We continued these discussions as we read more. One author pointed out what happens when television becomes the baby-sitter for parents who are not cautious about what their children watch. He said that unsupervised TV watching is like inviting a stranger into your home for two or three hours every day to tell the children all about a perverse world where violence solves problems and all anyone needs to be happy is the right beer, a fast car, good looks, and lots of sex. Of course, the parents are not there while all this is happening because they trust this television character to keep the children as quiet, interested, and entertained as possible. This teacher could do a lot of damage during that long daily visit, planting misperceptions no one could ever change and causing problems no one could solve.

One U.S. government study linked watching television with being obese, hostile, and depressed. In this study the researchers found that those who watched TV four or more hours a day were more than twice as likely to smoke cigarettes and be physically inactive as those who viewed the tube one hour or less a day.2

After discussing the negative impact of watching too much television, we turned to some of the positive things that might happen if we changed our habit. In one of the articles a study was quoted which showed that families who cut back on TV watching found more time for conversation at home. One person said, “Before it was, like, mostly we’d see Dad before he left for work. When he came home he’d watch TV with us, and then it was like, ‘Good night Dad.’ Now we talk all the time, we’re really close.”3

Another author pointed out that research data indicate that families that limit television viewing to a maximum of two hours a day of carefully selected programs may see the following significant changes in family relationships:

• Value setting will be taught and reinforced by the family. Families will learn how to establish values and how to reason together.

• Relationships between parents and youth will improve in families.

• Homework will be completed with less time pressure.

• Personal conversations will increase substantially.

• Children’s imaginations will come back to life.

• Each family member will become a discriminating selector and evaluator of programs.

• Parents can become family leaders again.

• Good reading habits may be substituted for television viewing.4

After we shared this information, we got up and left the room. About an hour later we were invited to return for the verdict. One of our daughters later gave us the full report of what happened in that vitally important hour.

She said that after we had left the room, her brothers and sisters quickly appointed her the discussion leader. They knew she was an advocate of watching TV, and they anticipated a quick resolution.

At first the meeting was chaotic. They all wanted to speak up and get their views known in a hurry so they’d be able to get a liberal decision—perhaps to cut down just a little on the amount of TV they were watching. In order to satisfy us as parents, someone suggested that they all promise to do their household chores cheerfully and get their homework done without being reminded.

But then our oldest son spoke up. Everyone turned to listen as he told how the articles had impressed him. He said TV had put some ideas into his mind that were not what he wanted to be there, and he felt he would be better off if he watched a lot less TV. He also said he felt the younger children in the family were starting to see things far worse than what he had seen as a young boy.

Then one of the younger children spoke up. He told everyone about a show he had seen that made him feel scared when he went to bed. At that point the spirit of the meeting became very serious. As the children continued to discuss the issue, a new feeling gradually began to emerge. They started to think differently.

One said, “I think we’re watching too much TV, but I don’t want to give it up altogether. There are some shows I feel good about and I really want to watch.” Then others talked about shows they enjoyed and wanted to continue to watch.

Another said, “I don’t think we should talk about how much time to watch each day because some days I don’t want to watch at all, but on other days I want to watch more.” So they decided to determine how many hours each week—rather than each day—would be appropriate. Some thought twenty hours would not be too much; some thought five hours would be better. Finally, they all agreed that seven hours a week was about right, and they appointed this daughter the monitor to ensure that the decision was carried out.

This decision proved to be a turning point in our family life. We began to interact more, to read more. We eventually reached the point where television was not an issue. And today—aside from news and an occasional movie or sports event—we hardly ever have it on.

By involving our children in the problem, we made them participators with us in finding a solution. And because the solution was their decision, they were invested in its success. We didn’t have to worry about “snoopervising” and keeping them on track.

Also, by sharing information about the consequences of excessive television watching, we were able to move beyond “our way” or “their way.” We were able to get into the principles involved in the issue and tap into the collective conscience of everyone involved. We were able to help them realize that a commitment to win-win is more than a commitment to having everyone temporarily pleased with the outcome. It’s a commitment to principles because a solution that is not based on principles is never a win for anyone in the long run.

An Exercise in Synergy

If you’d like to see how this Habits 4, 5, and 6 process can work in your own family, you might try the following experiment:

Take some issue that needs to be resolved, an issue where people have different opinions and different points of view. Try working together to answer the following four questions:

1. What is the problem from everyone’s point of view? Really listen to one another with the intent to understand, not to reply. Work at it until other people can express each person’s point of view to that person’s satisfaction. Focus on interests, not positions.

2. What are the key issues involved? Once the viewpoints are expressed and everyone feels thoroughly understood, then look at the problem together and identify the issues that need to be resolved.

3. What would constitute a fully acceptable solution? Determine the net results that would be a win for each person. Put the criteria on the table and refine and prioritize them so that everyone is satisfied they represent all involved.

4. What new options would meet those criteria? Synergize around creative new approaches and solutions.

As you go through this process, you’ll be amazed at the new options that open up and the shared excitement that develops when people focus on the problem and desired results instead of personalities and positions.

A Different Kind of Synergy

Up to this point we have primarily focused on the synergy that takes place when people interact, understand one another’s needs, purposes, and common objectives, and then produce insights and options that are truly better than those originally proposed. We could say that an integration has taken place in the thought processes, and the third mind has produced the synergistic result. This approach could be called transformational. In the language of nuclear change, you could compare this kind of synergy to the formation of an entirely new substance resulting from changes on the molecular level.

In transactional plus synergy, the cooperation between the people involved—rather than the creation of something new—is the essence of the relationship.

But there is another kind of synergy. This is the synergy that comes through a complementary approach—an approach in which one person’s strength is utilized and his or her weaknesses are made irrelevant by the strength of another. In other words, people work together like a team, but there’s no effort to integrate their thought processes to produce better solutions. This kind of synergy could be called transactional plus. Again, in nuclear language, the identifying properties of the substance would remain unchanged, and it would be synergistic in a different sense. In transactional plus synergy, the cooperation between the people involved—rather than the creation of something new—is the essence of the relationship.

This approach requires significant self-awareness. When a person is aware of a weakness, it instills humility sufficient to seek another’s strength to compensate for it. Then that weakness becomes a strength because it enabled complementariness to take place. But when people are unaware of their weaknesses and act as if their strengths are sufficient, their strengths become their weaknesses—and their very undoing for lack of complementariness.

For instance, if a husband’s strength lies in his courage and drive but the situation requires empathy and patience, then his strength can become a weakness. If a wife’s strength is sensitivity and patience, and the situation requires forceful decisions and actions, her strength can become a weakness. But if both husband and wife were aware of their strengths and weaknesses and had the humility to work as a complementary team, then their strengths would be well used and their weaknesses made irrelevant—and a synergistic result would occur.

I worked with an executive one time who was absolutely full of positive energy, but the executive to whom he reported was full of negative energy. When I asked him about this, he said, “I see my responsibility as finding out what’s lacking in my boss and supplying it. My role is not to criticize him but to complement him.” This man’s choice to be interdependent required great personal security and emotional independence. Husbands and wives, parents and children, can do similarly with one another. In short, complementariness means that we decide to be a light, not a judge; a model, not a critic.

When people are open to feedback regarding strengths and weaknesses—and when they have sufficient internal security so that the feedback will not destroy them emotionally and also sufficient humility to see the other’s strengths and work as a team—marvelous things begin to happen. Going back to the body metaphor: The hand cannot take the place of the foot, or the head the place of the heart. It works in a complementary way.

This is exactly what happens on a great athletic team or in a great family. And it requires much less intellectual interdependence than the other form of synergy. Perhaps it also requires a little less emotional interdependence, but it also requires great self-awareness and social awareness, internal security and humility. In fact, you might say that humility is the “plus” part between the two parts that enables this kind of complementariness. Transactional plus synergy is probably the most common form of creative cooperation, and it’s something even little children can learn.

Not All Situations Require Synergy

Now, not all decisions in the family require synergy. Sandra and I have synergistically arrived at what we’ve found to be a very effective way of making many decisions without synergy. One of us will simply say to the other, “Where are you?” That means, “On a scale of one to ten, how strongly do you feel about your point?” If one says, “I’m at a nine,” and the other says, “I’m at about a three,” then we go with the approach of the person who feels the strongest. If we both say five, we may go for a quick compromise. To make this work, both of us have agreed that we will always be totally honest with each other about where on the scale we are.

“On a scale of one to ten, how strongly do you feel about your point?”

We also have the same kind of agreement with our children. If we get into the car and people want to go different places, we sometimes say, “How important is this to you? Where are you on a scale of one to ten?” Then we all try to show respect for those who feel the strongest. In other words, we’ve tried to develop a kind of democracy that shows respect for the depth of feeling behind a person’s opinion or desire so that his or her vote counts more.

The Fruit of Synergy Is Priceless

This Habits 4, 5, and 6 process is a powerful problem-solving tool. It’s also a powerful tool that is tremendously helpful in creating family mission statements and enjoyable family times. I often teach Habits 4, 5, and 6 before teaching Habits 2 and 3 for this very reason. Habits 4, 5, and 6 cover a whole range of needs for synergy in the family—from the everyday decisions to the deepest, most potentially divisive, and most emotionally charged issues imaginable.

At one time, I was training two hundred MBA students at an eastern university, and many faculty and invited guests were there as well. We took the toughest, most sensitive, most vulnerable issue they could come up with: abortion. Two people came to the front of the classroom—a pro-life person and a pro-choice person who felt deeply about their positions. They had to interact with each other in front of these two hundred students. I was there to insist that they practice the habits of effective interdependence: think win-win, seek first to understand, and synergize. The following dialogue summarizes the essence of the interchange.

“Are you two willing to search for a win-win solution?”

“I don’t know what it could be. I don’t feel she—”

“Wait a minute. You won’t lose. You will both win.”

“But how can that possibly be? One of us wins, the other loses.”

“Are you willing to find a solution that you both feel good about, that is even better than what each of you is thinking now? Remember not to capitulate. Don’t give in and don’t compromise. It has to be better.”

“I don’t know what it could be.”

“I understand. No one does. We’ll have to create it.”

“I won’t compromise!”

“Of course. It has to be better. Remember now, seek first to understand. You can’t make your point until you restate his point to his satisfaction.”

As they began to dialogue, they kept interrupting each other.

“Yeah. But don’t you realize that—”

I said, “Wait a minute! I don’t know if the other person feels understood. Do you feel understood?”

“Absolutely not.”

“Okay. You can’t make your point.”

You cannot believe the sweat those people were in. They couldn’t listen. They had judged each other right from the beginning because they took different positions.

After about forty-five minutes, they started to really listen, and this had a great effect on them—personally and emotionally—and on the audience. As they listened openly and empathically to the underlying needs, fears, and feelings of people on this tender issue, the entire spirit of the interaction changed. People on both sides began to feel ashamed of how they had judged one another, labeled one another, and condemned all who thought differently. The two people in front had tears in their eyes, and so did many in the audience. After two hours each side said of the other, “We had no idea that’s what it meant to listen! Now we understand why they feel the way they do.”

Bottom line: No one really wanted abortion except in very exceptional situations, but everyone was passionately concerned about the acute needs and profound pain of people involved in these situations. And they were all trying to solve the problem in the best way they could—the way they thought would really meet the need.

As the two speakers let go of their positions, as they really listened to each other and understood each other’s concerns and intent, they were able to start working together to figure out what could be done. Out of their different points of view came an unbelievable synergy, and they were astonished at the synergistic ideas that resulted from the interaction. They came up with a number of creative alternatives, including new insights into prevention, adoption, and education.

There isn’t any subject that isn’t amenable to synergistic communication as long as you can use Habits 4, 5, and 6. You can see how interwoven mutual respect, understanding, and creative cooperation are. And you’ll find there are different levels in each of these habits. Deep understanding leads to mutual respect, and that takes you to an even deeper level of understanding. If you persist, opening each new door as it comes, more and more creativity is released and even greater bonding takes place.

One of the reasons this process worked with the MBA students was that everyone in the audience became involved, which brought a whole new level of responsibility to the two in front. The same is true in a family when parents realize that they are providing the most fundamental model of problem-solving for their children. The awareness of that stewardship tends to enable us to rise above our less effective inclinations or feelings and to take the higher road—to seek to truly understand and creatively seek the third alternative.

The process of creating synergy is both challenging and thrilling, and it works. But don’t be discouraged if you aren’t able to solve your deepest challenges overnight. Remember how vulnerable we all are. If you get hung up on the toughest, most emotional issues between you, perhaps you can put them aside a little while and go back to them later. Work on the easier issues. Small victories lead to larger ones. Don’t bag the process and don’t bag each other. If necessary, go back to the smaller issues.

Small victories lead to larger ones. Don’t bag the process and don’t bag each other. If necessary, go back to the smaller issues.

And don’t become frustrated if you’re now in a relationship where synergy seems like the “impossible dream.” I’ve found that sometimes when people get a taste of how wonderful a truly synergistic relationship can be, they conclude that there is no way they will ever have this kind of relationship with their spouse. They may think their only hope of having this kind of relationship is with someone else. But once again remember the Chinese bamboo tree. Work in your Circle of Influence. Practice these habits in your own life. Be a light, not a judge; a model, not a critic. Share your learning experience. It may take weeks, months, or even years of patience and long-suffering. But with rare exception it will eventually come.

Never fall into the trap of allowing money or possessions or personal hobbies to take the place of a rich, synergistic relationship. Just as gangs can become a substitute family for young people, these things can become a substitute for synergy. But they are a poor substitute. While these things may temporarily soothe, they will never deeply satisfy. Always be aware that happiness does not come from money, possessions, or fame; it comes from the quality of relationships with the people you love and respect.

As you begin to establish the pattern of creative cooperation in your family, your capacity will increase. Your “immune system” will become stronger. The bonding between you will deepen. Your positive experiences will put you in a whole new place to deal with your challenges and opportunities. Interestingly, your use of this process will increase your power and capacity to convey the most precious message that could ever be given, particularly to a child: “There is no circumstance or condition in which I would give up on you. I will be there for you and hang in there with you regardless of the challenge.” In ways unlike any other, it will affirm this message: “I love and value you unconditionally. You are of infinite worth, never to be compared.”

The fruit and bonding of true synergy are priceless.

SHARING THIS CHAPTER WITH ADULTS AND TEENS

Learning About Synergy

• Discuss the meaning of “synergy.” Ask family members: What examples of synergy do you see in the world around you? Responses might include: two hands working together; two pieces of wood holding more weight than both could support separately; living things functioning together synergistically in the environment.

• Discuss together the stories here and here. Ask: Does our family operate synergistically? Do we celebrate differences? How could we improve?

• Consider your marriage. What differences initially attracted you to each other? Have those differences turned into irritations, or have they become the springboard for synergy? Together, explore this question: In what ways are we better together than we are alone?

• Discuss the idea of the family immune system. Ask family members: Do we look at problems as negative obstacles to be overcome or as opportunities to grow? Discuss the idea that challenges build your immune system.

• Ask family members: In what ways are we fulfilling our four basic needs—to live, to love, to learn, to leave a legacy? In what areas do we need to improve?

Family Learning Experiences

• Review the section entitled “Not All Situations Require Synergy.” Develop an approach to making cooperative family decisions without synergy. As a family, go through the “Exercise in Synergy”.

• Conduct some fun experiments that show how much easier it is to do a job with the help of another person rather than alone. For example, try to make a bed, carry a heavy box, or lift a large table by the edge with one hand. Then invite others to participate and help. Use you imagination and come up with your own experiments to demonstrate the need for synergy.

SHARING THIS CHAPTER WITH CHILDREN

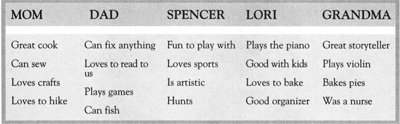

• Pretend that you are stranded in your home for an entire month with just your family. Ask: What kind of family synergy is available for us to draw on to make it through—and perhaps even enjoy—the challenge? Create a list of contributions each family member could make:

• Perform some experiments that teach the strength of synergy, such as the following: Experiment #1: Ask your children to tie their shoes with one hand. It cannot be done! Then ask another family member to help with one hand. It works! Point out how two working together can do more than one—or even two—working separately. Experiment #2: Give your children a Popsicle stick. Ask them to break it. They probably will be able to do so. Now give them four or five sticks stacked together and ask them to do the same. They probably won’t be able to do it. Use this as an illustration to teach that the family together is stronger than any one person alone.

• Share the experience about deciding on TV guidelines (here). Synergistically decide what the guidelines should be in your home.

• Ask your children to work together to create a poster for the family.

• Let your children plan a meal together. If they are old enough, let them prepare it together also. Encourage them to come up with dishes such as soup, fruit salad, or a casserole where the blending of a number of different ingredients creates something entirely new.

• Teach your children the system here: “On a scale of one to ten, how strongly do you feel about your point?” Practice it with your children in different situations. It’s fun to use and solves lots of problems!

• Plan a family talent night. Invite all family members to share their musical or dancing talent, a sports performance, scrapbooks, writings, drawings, woodwork, or collections. Point out how wonderful it is that we all have different things to offer, and that an important part of creating synergy is learning to appreciate others’ strengths and talents.