FROM SURVIVAL … TO STABILITY … TO SUCCESS … TO SIGNIFICANCE

I don’t know what your destiny will be, but one thing I know: The only ones among you who will really be happy are those who have sought and found how to serve.

—Albert Schweitzer

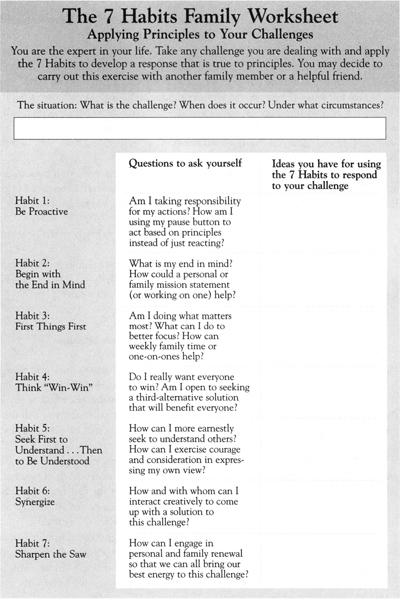

Now that we’ve been through each of the 7 Habits, I’d like to share with you the “bigger picture” of the power of this inside-out approach and how these habits work together to make it happen.

To begin with, I’d like to ask you to read a fascinating account of one woman’s inside-out odyssey. Notice how this experience reveals a proactive, courageous soul becoming a force of nature in her own right. Notice the impact her approach has on her, on her family, and on society:

By the time I was nineteen, I was divorced with a two-year-old child. We were in difficult circumstances, but I wanted to make the best possible life for my son. We had very little food. In fact, I reached the point where I would give food to my son but I wouldn’t eat. I lost so much weight that a coworker asked me if I was sick, and I finally broke down and told her what had happened. She put me in touch with Aid to Families with Dependent Children, which made it possible for me to attend community college.

At that point I still had this vision in my mind that I’d had when I was seventeen and pregnant with my son—a vision that I would go to college. I had no idea how I was going to do it. At seventeen I didn’t even have a high school diploma. But I just knew I was going to make a difference in the lives of others and be a light to others who faced the darkness I was facing. That vision was so strong that it got me through everything—including doing what was necessary to graduate from high school.

As I entered community college at nineteen, I still didn’t see how my vision was going to be fulfilled. How was I going to help anybody when I was still pretty traumatized from going through it all myself? But I felt driven because of the vision and because of my son. I wanted him to have a good life. I wanted him to have food and clothes and a yard to play in and an education. And I couldn’t provide those things for him without getting an education myself. So I kept rationalizing, “If I can just get a degree and make money, we will have a good life.” And I went to school and worked really hard.

When I was twenty-two I got married for the second time—this time to a wonderful man. We had a beautiful little daughter. I quit school to be with my children while they were small. We managed to make it okay financially, but I was still obsessed with fighting that monster called hunger. I just could not let that go. So when my children were a little older, it was “get the degree or bust.” My husband was basically “Mom” to the kids while I went to school.

I finally completed my degree—two, in fact: a four-year degree and a master’s degree in business administration. And this turned out to be very helpful. Later, when my husband lost his job as a factory worker, I was able to help him through school. My education saved us financially. He got his bachelor’s and master’s degrees and has been a counselor for several years now. He said he doesn’t think he would have done it without my support.

For some time I was very busy working and raising my family, and I thought: I’ve done it. I got my degree. I have a successful family. I should be happy. But then I realized that my vision had included helping others, and that still wasn’t part of my life. So when one of the alumni directors at school asked me to speak at an honors night for graduating seniors, I agreed. When I asked her what she wanted me to talk about, she said, “Just tell them how you got your education.”

To be quite honest, standing up in front of a group of at least two hundred highly educated women who were going to be honored for their expertise in science and math was a bit overwhelming. The thought of telling them where I had come from was not very thrilling to me. But by this time I’d learned about mission statements and I’d written one. It basically said that my mission in life was to help others to see the best in themselves. And I think it was the mission statement that gave me the courage to share my story.

I went into that speech making deals with God: “Okay, I’m going to do this. But if it fails, I’m never going to tell my story again.” It turned out to be a success because of what occurred afterward. After listening to my story, several of the faculty women got together and decided to do something to help welfare mothers, and the school started a scholarship fund. It was named after a woman who believed that if you educate a woman, you make a great impact not only on her life but on the lives of her children.

I was happy about what had happened and figured I’d done my part to help others, but then a little later I went through a developmental course for women where I had the opportunity to share my story again. One of the women there got the idea that we should fund a scholarship for one low-income woman, and we all agreed that we would each contribute $125 a year to do this.

From those beginnings my efforts have grown so that now I act as an advisor on a scholarship board for welfare women at a local women’s liberal arts college. I’m also involved in fund-raising for a scholarship for low-income women with high potential. These things may not seem like much to some, but I know what a big difference they can make. I had a lot of help along the way from people who felt they were doing “small things,” and I hope the small things I do for others now show my thanks.

All of this has had a positive impact on my family as well. My son, who is now working on his master’s degree, has a job where he helps people who have disabilities. He is very committed to these people and to their welfare. And my daughter—a first-year college student—is a volunteer teacher of English as a second language. She is also very committed to the underprivileged. They both seem to have a sense of responsibility to others. They have a deep awareness of the importance of contribution and actively seek it. And my husband’s work as a counselor provides a constant opportunity for him to serve people in a very personal way as well.

I guess I hadn’t really thought about it before, but as I look at it now, I see that in one way or another our entire family is serving and contributing to society as a whole. That makes me feel as though my vision is coming to pass—in a more expanded and complete way than I had originally understood it.

I believe that helping others is the most significant contribution anyone can make in life. I’m grateful that we’ve developed to the point where we’re able to do it.

Just think about the difference this woman’s proactivity has made in her own life, in the lives of the members of her family, and in the lives of all those who have benefited from her contribution. What a tribute to the resiliency of the human spirit! Instead of allowing her circumstances to overpower the vision she had inside, she held on to it and nurtured it so that it eventually became the driving force that empowered her to rise above those circumstances.

Notice how, in the process, she and her family moved through each of the four levels mentioned in the title of this chapter.

Survival

At first this woman’s consuming concern was for the basic need for food. She was hungry. Her child was hungry. The one focus of her life was to make enough to feed her son and herself so that they wouldn’t starve. This need to survive was so basic, so fundamental, so vital that even when her circumstances changed, she was still “obsessed with fighting that monster called hunger” and “could not let that go.”

This represents the first level: survival. And many families, many marriages, are literally fighting for it—not only economically but also mentally, spiritually, and socially as well. These people’s lives are filled with uncertainty and fear. They’re scrambling to make it through the day. They live in a world of chaos with no predictable principles to operate from, no structures or schedules to depend on, no sense of what tomorrow is going to hold. They often feel that they are victims of circumstances or of other people’s injustice. They’re like a person who has been rushed into the emergency room and then put into the intensive care unit: Their vital signs may be present but are unstable and unpredictable.

Eventually these families may hone their survival skills. They may even have brief breathing spaces between their efforts to survive. But their day-in, day-out objective is simply to survive.

Stability

Going back to the story, you’ll notice that through her efforts and help from others, this woman eventually moved from survival to stability. She had food and the basic necessities of life. She even had a stable marriage relationship. Although she was still struggling with scars from the “survival” days, she and her family were functional.

This represents the second level, which is what many families and marriages are trying to achieve. They’re surviving, but different work schedules and different habit patterns result in their hardly ever getting together to talk about what would bring more stability to the marriage or family. They live in a state of disorganization. They don’t know what to do; they have a sense of futility and feel trapped.

But the more knowledge these individuals acquire, the more hope they get. And as they act on this knowledge and begin to organize some schedules and some structures for communication and problem-solving, even more hope emerges. The hope overcomes ignorance and futility. And the family, the marriage, becomes stable, dependable, and predictable.

So they’re stable—but they’re not yet “successful.” There’s a degree of organization so that food is provided and bills are paid. But the problem-solving strategy is usually limited to “flight or fight.” People’s lives touch from time to time in order to deal with the most pressing issues, but there’s no real depth in the communication. People generally find their satisfactions away from the family. “Home” is just a place that has to take you in. There’s boredom. Interdependence is exhausting. There’s no sense of shared accomplishment. There’s no real happiness, love, joy, or peace.

Success

The third level, success, involves accomplishing worthy goals. These goals can be economic, such as having more income, managing existing income better, or agreeing to cut expenses in order to save or have money for education or a planned vacation. They can be mental, such as learning some new skill or getting a degree. You’ll notice that most of the goals reflected in this woman’s story were in these two areas. They involved economic well-being and education. But goals can also be social, such as having more time together as a family with good communication or establishing traditions. Or they can be spiritual, such as creating a sense of shared vision and values and renewing their faith and common beliefs.

In successful families, people set and achieve meaningful goals. “Family” matters to people. There’s genuine happiness in being together. There’s a sense of excitement and confidence. Successful families plan and carry out family activities and organize to accomplish different tasks. The focus is on better living, better loving, and better learning, and on renewing the family through fun family activities and traditions.

But even in many “successful” families, a dimension is missing. Look back once again at this woman’s account. She said, “For some time I was very busy working and raising my family, and I thought: I’ve done it. I got my degree. I have a successful family. I should be happy. But then I realized that my vision had included helping others, and that still wasn’t part of my life.”

Significance

The fourth level, significance, is where the family is involved in something meaningful outside itself. Rather than being content to be a successful family, the family has a sense of stewardship or responsibility to the greater family of mankind, as well as a sense of accountability around that stewardship. The family mission includes the leaving of some kind of legacy—of reaching out to other families who may be at risk, of participating together to make a real difference in the community or in the larger society, possibly through their church or other service organizations. This contribution brings a deeper and higher fulfillment—not just to individual family members but to the family as a whole.

The woman in this story felt a sense of responsibility and began to contribute in her own life. And because of her example, her children developed it in their lives. Families ideally would reach the point where this sense of stewardship or responsibility would be an integral part of their family mission statement—something the entire family would be involved in.

At times that might mean that one family member would contribute in a particular way and the rest of the family would work together to support that effort. In our own family, for example, it meant that we all rallied around Sandra to support her when she spent hours working as president of a women’s service organization. We tried to provide support and encouragement for some of our children when they chose to devote a couple of years to church service in foreign lands. We’ve all felt a sense of unity and contribution over the years as the family supported me in my work—and later some of our children’s work—in the Covey Leadership Center (now Franklin Covey). All of these things have been family efforts, though not all family members were involved directly in making the contribution.

There are other times when the entire family is directly involved in something such as a community project. I know of one family that works together to provide visits and entertaining videos for elderly people in rest homes. This began when their own grandmother had a stroke that forced them to put her in a rest home, and it seemed the only thing she really enjoyed was videos. The family decided that they would visit her at least once a week and bring her different old movies from the video store. It became such a success with the grandmother and with other patients that they started getting videos for others as well. Through all the years the five children in this family were teenagers, they continued serving in this manner. And it helped these kids not only to stay close to their grandmother but also to serve many other older people.

Another family spends each New Year’s Eve cooking for and feeding the homeless. They hold several planning meetings beforehand, deciding what they want to serve, how to decorate the tables, and who’s going to take care of what responsibility. It’s become a joyous tradition for them to work together to provide a wonderful evening in the county soup kitchen for the poor.

I’m aware of many other families in which contribution has meant, at least for a time, rallying around an extended or intergenerational family member in need. One husband and father shared how his family did this:

Near the end of 1989 my father was diagnosed with a brain tumor. For sixteen months we fought it with chemotherapy and radiation. Finally, near the end of 1990, he was no longer able to take care of himself, and my mother—who was in her 70s—was unable to provide the help he needed.

My wife and I were therefore confronted with some very serious decisions. After discussing it together, we decided to move my mother and father into our home. We put my father in a hospital bed in the middle of our family room, and that’s where he stayed for the next three months until he died.

I realize now that had I not had the grounding of principles and a clear understanding of what “first things” meant in my life, I might not have made that decision. But although this was one of the most difficult times in my life, it was also one of the most rewarding. I feel I can look back and know that we did what was the right thing to do in our circumstances. We did everything we possibly could to make him comfortable. We gave him the best it is humanly possibly to give—our selves. And we feel good about that.

The intimacy we were able to develop with my father in those last months was profound. Not only did my wife and I learn from this experience, but my mother did also. She knows she can look forward to the future and trust how we would handle the situation should she get into a similar position. And our children learned invaluable lessons in service as they watched what my wife and I did, and helped in the ways they could.

For those few months the significant contribution of this family was to help a father and grandfather die with dignity, surrounded by love. What a powerful message this sent to his wife and to everyone else in the family! And how enabling this experience will be for these children as they grow up with a sense of genuine service and love.

Often, even those who suffer in these difficult situations can leave a legacy of inspiration for their families. My own life has been profoundly affected by my sister Marilyn’s example of contribution and significance as she lay dying of cancer. Two nights before she passed away, she told me, “My only desire during this time has been to teach my children and grandchildren how to die with dignity and to give them the desire to contribute—to live life nobly based on principles.” Her whole focus during the weeks and months prior to this time had been on teaching her children and grandchildren, and I know they will be inspired and ennobled by her example—as I have been—for the rest of their lives.

There are many ways to become involved in significance—within the family, with other families, and in society as a whole.

There are many ways to become involved in significance—within the family, with other families, and in society as a whole. We have friends and relatives whose intergenerational and extended families have rallied around them in their struggles with a Down’s syndrome child, a severe drug problem, an overwhelming financial problem, or a failing marriage. The entire family culture went to work and came to the aid of those so involved, enabling them to reclaim their heritage and erase many psychic scars of the past.

Families can also become involved in local schools or communities to increase drug awareness, reduce crime, or assist children in families that are at risk. They can become involved in fund-raising, mentoring programs, tutoring programs, or other church or community service. Or they can become involved in significance on a higher level of interdependence—not just within the family but between families on common projects. This might include families working together in a “Neighborhood Watch” program or joining forces with other community- or church-sponsored service projects or events.

There are even some communities in the world where the entire population is involved in a massive interdependent and significant effort. One is Mauritius—a tiny, developing island nation in the Indian Ocean, two thousand miles off the east coast of Africa. The norm for the 1.3 million people who live there is to work together to survive economically, take care of the children, and nurture a culture of both independence and interdependence. They train people in marketable skills so that there is no unemployment or homelessness and very little poverty or crime. The interesting thing is that these people come from five distinct and very different cultures. Their differences are profound, yet they value these differences so highly that they even celebrate each other’s religious holidays! Their deeply integrated interdependence reflects their values of order, harmony, cooperation, and synergy, and their concern for all people—particularly children.

Contributing together as a family not only helps those who benefit from the contribution, but it also strengthens the contributing family.

Contributing together as a family not only helps those who benefit from the contribution, but it also strengthens the contributing family in the process. Can you imagine anything more energizing, more unifying, more filled with satisfaction than working with the members of your family to accomplish something that really makes a difference in the world? Can you imagine the bonding, the sense of fulfillment, the sense of shared joy?

Living outside ourselves in love actually helps the family become self-perpetuating. Its very giving increases the family’s sense of purpose and thus its longevity and ability to give. Hans Selye, the father of modern stress research, taught that the best way to stay strong, healthy, and alive is to follow the credo, “Earn thy neighbor’s love.” In other words, stay involved in meaningful, service-oriented projects and pursuits. He explains that the reason women live longer than men is psychological rather than physiological. A woman’s work is never done. Built into her psyche and cultural reinforcement is a continuing responsibility toward the family. Many men, on the other hand, center their lives on their careers and identify themselves in terms of these careers. Their family becomes secondary, and when they retire, they do not have this same sense of continuing service and contribution. As a result, the degenerative forces in the body are accelerated and the immune system is compromised, and so men tend to die earlier. There is much wisdom in the saying by an unknown author, “I sought my God, and my God I could not find. I sought my soul, and my soul eluded me. I sought to serve my brother in his need, and I found all three—my God, my soul, and thee.”

On the level of significance, the family becomes the vehicle through which people can effectively contribute to the well-being of others.

This level of significance is the supreme level of family fulfillment. Nothing energizes, unites, and satisfies the family like working together to make a significant contribution. This is the essence of true family leadership—not only the leadership you can provide to the family, but the leadership your family can provide to other families, to the neighborhood, to the community, to the country. On the level of significance, no longer is the family an end in and of itself. It becomes the means to an end that is greater than itself. It becomes the vehicle through which people can effectively contribute to the wellbeing of others.

From Problem-Solving to Creating

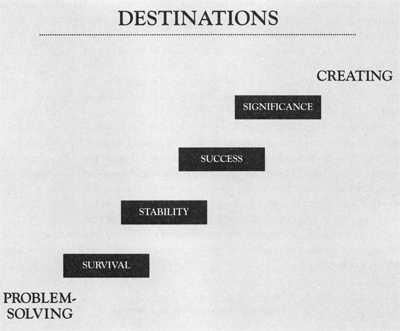

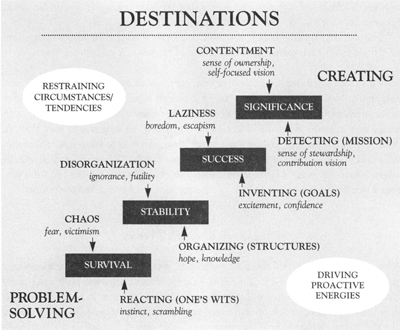

As you move toward your destination as a family, you may find it helpful to look at these four different levels as interim destinations on your path. The achieving of each destination represents a challenge in and of itself, but it may also provide the wherewithal to move to the next destination.

You will also want to be aware that in moving from survival to significance, there’s a dramatic shift in thinking. In the areas of survival and stability, the primary mental energy focus is on problem-solving:

“How can we provide food and shelter?”

“What can we do about Daryl’s behavior or Sara’s grades?”

“How can we get rid of the pain in our relationship?”

“How can we get out of debt?”

But as you move toward success and significance, that focus shifts to creating goals and visions and purposes that ultimately transcend the family itself:

“What kinds of education do we want to provide for our children?”

“What would we like our financial picture to look like five or ten years down the road?”

“How can we strengthen family relationships?”

“What can we do together as a family that will really make a difference?”

That doesn’t mean that families who have moved to success and significance don’t have problems to solve. They do. But the major focus is on creating. Instead of trying to eliminate negative things from the family, they’re focused on trying to create positive things that were not there before—new goals, new options, new alternatives that will optimize situations. Instead of rushing from one problem-solving crisis to another, they’re focused on coming up with synergistic springboards to future contribution and fulfillment.

When you’re problem minded, you want to eliminate something. When you’re opportunity or vision minded, you want to bring something into existence.

In short, they’re opportunity minded, not problem minded. When you’re problem minded, you want to eliminate something. When you’re opportunity or vision minded, you want to bring something into existence.

And this is an altogether different mind-set, a different emotional/spiritual orientation. And it leads to a completely different feeling in the culture. It’s like the difference between feeling exhausted from morning until night and feeling rested, energized, and enthused. Instead of feeling frustrated, mired in concerns, and surrounded by dark clouds of despair, you feel optimistic, invigorated, and full of hope. You’re filled with positive energy that leads to a creative, synergistic mode. Focused on your vision, you take problems in stride.

The wonderful thing about moving from survival to significance is that it has very little to do with extrinsic circumstances. One woman said this:

We’ve discovered that economics really has very little to do with achieving significance as a family. Now that we have more, we’re able to do more. But even in the early years of our marriage, we were able to give of our time and talents to help others. And it really united us as a family. When our children were very young, we were able to teach them the value of helping a neighbor, visiting a rest home, or taking a meal to someone who was sick. We found that these kinds of things helped define our family: “We are a family who helps others.” And that made a big difference while our children were growing up. I am convinced that their teenage years were very different because of that contribution focus.

Driving and Restraining Forces

As you move from survival toward significance, you’ll find that there are forces that energize you and help move you forward. Knowledge and hope will push you toward stability. Excitement and confidence drive you toward success. A sense of stewardship and a contribution vision will impel you toward significance. These things are like the tailwinds that help an airplane move more quickly toward its destination—sometimes arriving before the scheduled time.

But you’ll also find there are strong headwinds—forces that tend to restrain you, to slow or even reverse your progress, to push you back, to keep you from moving ahead. Victimism and fear tend to drive you back into the fundamental struggle for survival. Lack of knowledge and a sense of futility tend to keep you from becoming stable. Feelings of boredom and escapism thwart the effort to be successful. Self-focused vision and a sense of ownership—rather than stewardship—tend to keep you from significance.

You’ll notice that the restraining forces are generally more emotional, psychological, and illogical; driving forces are more logical, structural, and proactive.

Of course, we need to do what we can to power up the driving forces. This is the traditional approach. But in a force field, the restraining forces will eventually restore the old equilibrium.

Most important, we need to remove restraining forces. To ignore them is like trying to move toward your destination with your thrusters in reverse. You can put forth all kinds of effort, but unless you do something to remove the restraining forces, you’ll be going nowhere fast, and the effort will exhaust you. You do need to work on driving and restraining forces at the same time, but give the primary effort to working on the restraining forces.

Habits 1, 2, 3, and 7 fire up the driving forces. They build proactivity. They give you a clear, motivating sense of destination that is greater than self. In fact, without some kind of vision or mission of significance, the course of least resistance is to stay in your comfort zone, to use only those talents and gifts that are already developed and perhaps recognized by others. But when you share this vision of true significance, of stewardship, of contribution, then the course of least resistance will be to develop those capacities and fulfill that vision because fulfilling the vision becomes more compelling than the pain of leaving your comfort zone. This is what family leadership is about—the creating of this kind of compelling vision, the securing of consensual commitment toward it and toward doing whatever it takes to fulfill it. This is what taps into people’s deepest motivations and urges them to become their very best. Then Habits 4, 5, and 6 give you the process for working together to accomplish all those things. And Habit 7 gives you the renewing power to keep doing it.

But Habits 4, 5, and 6 also enable you to understand and unfreeze the restraining cultural, emotional, social, and illogical forces so that even the smallest amount of proactive energy on the positive side can make tremendous gains. In fact, a deep understanding of the fears and anxieties that hold you back changes their nature, content, and direction, enabling you to actually convert restraining forces into driving ones. We see this all the time when a so-called problem person feels listened to and understood and then becomes part of the solution.

Consider the analogy of a car. If you had one foot on the gas pedal and the other foot on the brake, which would be the better approach to go faster—flooring the gas pedal or releasing the brake? Obviously, the key is to release the brake. You could even lighten up on the gas pedal and still go faster as long as you got that other foot off the brake.

Consider the analogy of a car. If you had one foot on the gas pedal and the other foot on the brake, which would be the better approach to go faster—flooring the gas pedal or releasing the brake?

Similarly, Habits 4, 5, and 6 release the emotional brake (or give air) in the family so that even the slightest increase in driving forces will take the culture to a new level. In fact, there is extensive research to show that by involving people in the problems and working out the solution together, restraining forces are transformed into driving forces.1

So these habits enable you to work on driving and restraining forces at the same time and free you to move from survival to significance. You may find it helpful to go over the chart on the previous page with your family to get a sense of perspective, to see where you feel you are as a family, and to identify driving and restraining forces, and decide what to do about them. You may also want to use it as a tool to help your family move from a problem-solving to a creative orientation.

Where Do I Begin?

Most of us have an innate desire to improve our families. Subconsciously we want to move from survival toward success or significance. But we often have a tough time. We may try as hard as we possibly can and do everything we can think of, and yet the results may be the exact opposite of the ones we want.

This is especially true when we’re dealing with a spouse or a teenager. But even when we’re dealing with young children, who are generally more open to influence, we wonder how to influence them in the best possible way. Do we punish? Do we spank? Do we send them to a room by themselves? Is it right to use our superior size or strength or mental development to force them to do what we want them to do? Or are there principles that can help us understand and know how to influence in a better way?

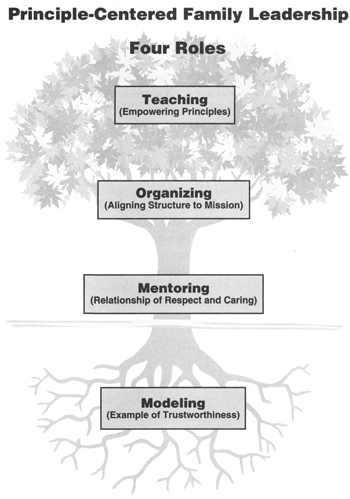

Any parent (or son, daughter, brother, sister, grandparent, aunt, uncle, nephew, niece, or other person) who really wants to become a transition person—an agent of change—and help a family move higher on the destination chart can do it, particularly if the person understands and lives the principles behind the four basic family leadership roles. Because family is a natural, living, growing thing, we’d like to describe these roles in terms of what we call the Principle-Centered Family Leadership Tree. This tree serves as a reminder that we’re dealing with nature and with natural laws or principles. It will help you understand these four basic leadership roles and also help you diagnose and think through strategies to resolve family problems. (You might want to take a look at the tree here.)

With the image of this tree in mind, let’s take a look at the four family leadership roles and how cultivating the 7 Habits in each role can help you move your family along the path from survival to significance.

Modeling

I know of one man who loved to go hunting with his father when he was a young boy. The father would plan weeks ahead with his sons, preparing and creating anticipation for the event.

As an adult, this son told us:

I will never forget one Saturday opening of the pheasant hunt. Dad, my older brother, and I were up at 4:00 A.M. We ate Mom’s big, hearty breakfast, packed the car, and drove to our designated field by 6:00 A.M. We arrived early to stake out our spot before any others, anticipating the 8:00 A.M. opening hour.

As that hour drew near, other hunters were frantically driving around us, trying to find spots in which to hunt. As 7:40 arrived, we saw hunters driving into the fields. By 7:45 the firing had started—fifteen minutes before the official start. We looked at Dad. He made no move except to look at his watch, still waiting for 8:00 A.M. Soon the birds were flying. By 7:50 all hunters had moved into the fields, and shots were everywhere.

Dad looked at his watch and said, “The hunt starts at eight o’clock, boys.” About three minutes before eight, four hunters drove into our spot and walked past us into our field. We looked at Dad. He said, “The hunt starts for us at eight.” At eight the birds were gone, but we started our drive into the field.

We didn’t get any birds that day. We did get an unforgettable memory of a man I fervently wanted to be like—my father, my ideal, who taught me absolute integrity.

Now what was at the center of this father’s life—the pleasure and recognition of being a successful hunter or the quiet soul satisfaction of being a man of integrity, a father, and a model of integrity to his boys?

On the other hand, I also know of another man who set quite a different example for his son. His wife recently said to us:

My husband, Jerry, leaves the guidance of our fourteen-year-old son Sam to me. It’s been that way ever since Sam was born. Jerry has always been sort of an uninvolved observer. He never tries to help.

Whenever I get after him and tell him he should get involved, he just shrugs. He tells me he has nothing to offer, and I am the one who should teach and lead our son.

Sam is now in junior high school, and you would not believe the problems he has! I told Jerry that the next time Sam’s school principal called, he would have to take the call because I’ve had it. That night Jerry told Sam that his mom wasn’t going to help him anymore, so he’d better quit causing problems.

I got so mad when he said that, I just wanted to get up and leave. When I exploded, Jerry said, “Hey, don’t blame me. You’re the one who’s been in charge. You’ve taught and led him, not me.”

Who is really teaching and leading this young boy? And what is this father teaching his son? The father has tried to forfeit his influential position by stepping aside and supposedly letting his wife do the influencing. But has he not had a powerful influence as well? When Sam grows up, won’t his father’s actions (or lack of actions) have influenced him in profound ways?

There is no question that example is the very foundation of influence. When Albert Schweitzer was asked how to raise children, he said, “Three principles—first, example; second, example; and third, example.” We are, first and foremost, models to our children. What they see in us speaks far more loudly than anything we could ever say. You cannot hide or disguise your deepest self. In spite of skillful pretending and posturing, your real desires, values, beliefs, and feelings come out in a thousand ways. Again, you teach only what you are—no more, no less.

You cannot not model. It’s impossible. People will see your example—positive or negative—as a pattern for the way life is to be lived.

That’s why the deepest part of this Principle-Centered Family Leadership Tree—the thick fibrous root structure—represents your role as a model.

This is your personal example. It’s the consistency and integrity of your own life. This is what gives credibility to everything you try to do in the family. As people see in your life the model of what you’re trying to encourage in the lives of others, they feel they can believe in you and can trust you because you are trustworthy.

The interesting thing is that, like it or not, you are a model. And if you’re a parent, you are your children’s first and foremost model. In fact, you cannot not model. It’s impossible. People will see your example—positive or negative—as a pattern for the way life is to be lived.

As one unknown author so beautifully expressed it:

If a child lives with criticism, he learns to condemn.

If a child lives with security, he learns to have faith in himself.

If a child lives with hostility, he learns to fight.

If a child lives with acceptance, he learns to love.

If a child lives with fear, he learns to be apprehensive.

If a child lives with recognition, he learns to have a goal.

If a child lives with pity, he learns to be sorry for himself.

If a child lives with approval, he learns to like himself.

If a child lives with jealousy, he learns to feel guilty.

If a child lives with friendliness, he learns that the world is a nice place in which to live.

If we are careful observers, we can see our own weaknesses reappear in the lives of our children. Perhaps this is most evident in the way differences and disagreements are handled. To illustrate, a mother goes to the family room to call her young sons to lunch and finds them arguing and fighting over a toy. “Boys, I’ve told you before not to fight! You work it out so each has a turn.” The older grabs it away from his smaller brother with “I’m first!” The younger cries and refuses to come to lunch.

The mother, puzzled as to why her boys never seem to learn, reflects for a moment on her own handling of differences with her husband. She remembers “only last night” when they had a sharp exchange over a matter of finances. She remembers “only this morning” when her husband left for work rather disgruntled after a disagreement on plans for the evening. And the more this mother reflects, the more she realizes she and her husband have demonstrated over and over again how not to handle differences and disagreements.

This book is filled with stories that illustrate how the thinking and actions of children are shaped by what parents think and do. The thinking of the parents will be inherited by their children, sometimes to the third and fourth generations. Parents have been scripted by their parents … who have been scripted by their parents in ways that none of the generations may even be aware of.

That is why our role modeling as parents to our children is our most basic, most sacred, most spiritual responsibility. We are handing life’s scripts to our children—scripts that, in all likelihood, will be acted out for much of the rest of their lives. How important it is for us to realize that our day-to-day modeling is far and away our highest form of influence in our children’s lives! And how important it is for us to examine what is really at the “center” of our lives, to ask ourselves, Who am I? How do I define myself? (Security) Where do I go and what do I do to receive direction to guide my life? (Guidance) How does life work? How should I live my life? (Wisdom) What resources and influences do I access to nurture myself and others? (Power) Whatever is our “center,” or the lens through which we look at life, will profoundly affect our children’s thinking—whether we are aware of it and whether we want to have this influence or not.

If you choose to live the 7 Habits in your personal life, what is it that your children will learn? Your modeling will provide an example of a proactive person who has developed a personal mission statement and is attempting to live by it; of a person who has great respect and love for others, who seeks to understand them and be understood by them, who believes in the power of synergy and is not afraid to take risks in working with others to create new third-alternative solutions. You will provide a model of a person who is in a state of constant renewal—of physical self-control and vitality, continual learning, continual building of relationships, and constant attempting to align with principles.

What impact will that kind of model have on your children’s lives?

Mentoring

I know a man who is very committed to his family. Even though he is involved in many good and worthwhile activities, the most important thing to him by far is to teach his children and to help them become responsible, caring, contributing adults. And he is an excellent model of all he is trying to teach.

He has a large family, and one summer two of his daughters were planning to marry. One evening when they both had their fiancés in the family home, he sat down with all four of them and spent several hours talking with them, sharing many things he had learned that he knew would help them along the way.

Later, after he had gone upstairs to get ready for bed, his daughters went to their mother and said, “Dad just wants to teach us; he doesn’t want to get to know us personally.” In other words, Dad just wants to dispense all this wisdom and knowledge he has accumulated through the years, but does he really know us as individuals? Does he accept us? Does he really care about us, just as we are? Until they knew that, until they could feel that unconditional love, they were not open to his influence—however good that influence might have been.

Again, as the saying goes, “I don’t care how much you know until I know how much you care.” That’s why the next level of the tree—the massive, sturdy trunk—represents your role as a mentor. “Mentoring” is building relationships. It’s investing in the Emotional Bank Account. It’s letting people know that you care about them—deeply, sincerely, personally, unconditionally. It’s championing them.

This deep, genuine caring encourages people to become open, teachable, and open to influence because it creates a profound feeling of trust. This clearly reaffirms the relationship we mentioned in Habit 1 between the Primary Laws of Love and the Primary Laws of Life. Again, only when you live the Primary Laws of Love—when you consistently make deposits in the Emotional Bank Accounts of others because you love them unconditionally and because of their intrinsic worth rather than because of their behavior or social status or for any other reason—do you encourage obedience to the Primary Laws of Life, laws such as honesty, integrity, respect, responsibility, and trust.

Now, if you’re a parent, it’s important to realize that whatever your relationship with your children, you are their first mentor—someone who relates to them, someone whose love they deeply desire. Positively or negatively, you cannot not mentor. You are your children’s first source of physical and emotional security or insecurity, their feeling of being loved or being neglected. And the way you fulfill your mentoring role will have a profound effect on your child’s sense of self-worth and on your ability to influence and teach.

The way you fulfill your mentoring role will have a profound effect on your child’s sense of self-worth and on your ability to influence and teach.

The way you fulfill your mentoring role with any family member—but particularly with your most difficult child—will have a profound impact on the level of trust in the entire family. As we said in Habit 6, the key to your family culture is how you treat the child that tests you the most. It is that child who will really test your ability to love unconditionally. When you can show unconditional love to that one, the other children will know that your love for them is also unconditional.

I have become convinced there is almost unbelievable power in loving another person in five ways simultaneously:

1. Empathizing: listening with your own heart to another’s heart.

2. Sharing authentically your most deeply felt insights, learnings, emotions, and convictions.

3. Affirming the other person with a profound sense of belief, valuation, confirmation, appreciation, and encouragement.

4. Praying with and for the other person from the depths of your soul, tapping into the energy and wisdom of higher powers.

5. Sacrificing for the other person: going the second mile, doing far more than is expected, caring and serving until it sometimes even hurts.

Most often neglected of the five are empathizing, affirming, and sacrificing. Many people will pray for others; many will share. But to truly listen empathically, to truly believe in and affirm others, and to walk with them in some kind of sacrifice mode so that you are doing what they would not expect you to do—in addition to praying and sharing—reaches people in ways that nothing else can.

One of the biggest mistakes people make is trying to teach (or influence or warn or discipline) before they have the relationship to sustain it. The next time you feel inclined to try to teach or correct your child, you might want to push your pause button and ask yourself this: Is my relationship with this child sufficient to sustain this effort? Is there enough reserve in the Emotional Bank Account to enable this child to have an open ear, or will my words just bounce off as though he or she were surrounded by some kind of bulletproof shield? It’s very easy to get so caught up in the emotion of the moment that we don’t stop to ask ourselves if what we’re about to do will be effective—if it will accomplish what we really want to accomplish. And if it won’t, much of the time it’s because there’s not enough reserve to sustain it.

So you can make deposits into the Emotional Bank Account. You can build the relationship. You can mentor. As people feel your love and caring, they will begin to value themselves and become more open to your influence as you try to teach. What people identify with far more than what they hear is what they see and what they feel.

Organizing

You could be a wonderful model and have a great relationship with the members of your family, but if your family is not organized effectively to help you accomplish what you’re trying to accomplish, then you’re going to be working against yourself.

It’s like the business that talks teamwork and cooperation but then has systems—such as compensation—that reward competition and individual achievement. Instead of being in alignment with and facilitating what you want to accomplish, the way you have things organized actually gets in the way.

In a like manner, in your family you may talk “love” and “family fun,” but if you never plan any time together to have family dinners, work on projects, go on vacations, watch a movie, or have a picnic in the park, then your very lack of organization gets in the way. You may say “I love you” to someone, but if you’re always too busy to spend meaningful one-on-one time with that person and fail to prioritize that relationship, you will allow entropy and decay to set in.

You may talk “love” and “family fun,” but if you never plan any time together, then your very lack of organization gets in the way.

Your organizing role is where you would align the structures and systems in the family to help you accomplish what’s truly important. This is where you would use the power of Habits 4, 5, and 6 at the mentoring level to create your family mission statement and set up two new structures that most families don’t have: dedicated weekly family times and calendared one-on-one dates. These are the structures and systems that will make it possible to carry out the things you’re trying to do in your family.

Without creating principle-based patterns and structures, you will not be able to build a culture with common vision and shared values. Moral authority will be sporadic and shallow because it will be based only on the present actions of a few people. It won’t be built into the culture of the family.

But the more moral or ethical authority grows and becomes institutionalized into the culture in the form of principles—both lived and structurally embodied—the less dependent you are on individual persons to maintain a beautiful family culture. The mores and norms inside the culture itself will reinforce the principles. The very fact that you have weekly family time says a hundredfold that family is truly important. So even though someone may be flaky or duplicitous and someone else may be lazy, the setting up of these structures and processes compensates for most—though not all—of those human deficiencies. It builds the principles into the patterns and structures that people can depend on. And the results are similar to those that happen when you go on a vacation: A family may have emotional ups and downs on a vacation, but the fact that they went on a vacation together and that it was renewing a tradition builds the principles into the culture. It frees the family from always being dependent on good example.

Again, in the words of sociologist Emile Durkheim, “When mores are sufficient, laws are unnecessary. When mores are insufficient, laws are unenforceable.” In adapting this to the family we might say, “When mores are sufficient, family rules are unnecessary. When mores are insufficient, family rules are unenforceable.”

“When mores are sufficient, family rules are unnecessary. When mores are insufficient, family rules are unenforceable.”

Ultimately, if people won’t support the patterns and structures, then you’ll see instability enter the family, and the family may even struggle for survival. But if these patterns become habits, they become strong enough to subordinate individual weaknesses that manifest themselves from time to time. For example, you may not begin a one-on-one or family time with the best of feelings, but if you spend the entire evening doing some fun thing together, you’ll probably end with the best of feelings.

This is one of the most powerful things that I have learned in my professional work with organizations. You must build the principles into the structures and systems so that they become part of the culture itself. Then you are no longer dependent on a few people at the top. I’ve seen situations in which an entire top management team moved into another company, but because of the “deep bench strength” in the culture, there was hardly a blip in the economic and social performance of the organization. This is one of the great insights of W. Edwards Deming, a guru in the field of quality and management and one of the key reasons for Japan’s past economic success. “The problem is not in bad people, it’s in bad processes, bad structures and systems.”2

That is why we give such energy to this organizing role. Without some basic organizing it’s easy for family members to become like ships that pass in the night. So the third level of this tree—depicted by the trunk breaking out into the larger and then smaller limbs—represents your role as an organizer. This is where people experience how the principles are built into the patterns and structures of everyday life so that not only do you say that family is important but they experience it—in frequent meals together, family times, and meaningful one-on-ones. Soon they come to trust these family structures and patterns. They can depend on them, and this gives them a sense of security and order and predictability.

By organizing around your deepest priorities, you’re creating alignment and order. You’re setting up systems and structures that support—rather than get in the way of—what you’re trying to do. Organizing becomes an enabler—literally transforming restraining factors into driving or enabling factors on the path from survival to significance.

Teaching

When one of our sons started junior high school, he began coming home with poor test scores. Sandra took him aside and said, “Look, I know you’re not dumb. What seems to be the problem?”

“I don’t know,” he mumbled.

“Well,” she said, “let’s see if we can’t do something to help you.”

After dinner they sat down together and went over some of the tests. As they talked, Sandra began to realize that this boy wasn’t reading the instructions carefully before taking the tests. Furthermore, he didn’t know how to outline a book, and there were several other gaps in his knowledge and understanding.

So they began to spend an hour together every evening, working on reading, outlining books, and understanding instructions. By the end of the semester he had gone from 40 percent test scores to all A’s and one A plus!

When his brother saw his report card on the fridge, he said, “You mean that’s your report card? You must be some kind of a genius!”

Teaching moments are some of the supreme moments of family life—those incomparable times when you know you’ve made a significant difference in the life of another family member.

I am convinced that part of the reason Sandra was able to have that kind of influence at that time in his life is because of her modeling, mentoring, and organizing. She placed a high value on education, and everyone in the family knew it. She had a great relationship with this son. She had spent hours and hours with him over the years, building the Emotional Bank Account and doing things he enjoyed. And she organized her time so that she could be with him to help him in this way.

These teaching moments are some of the supreme moments of family life—those incomparable times when you know you’ve made a significant difference in the life of another family member. This is the point at which your efforts help “empower” family members so that they develop the internal capacity and skill to live effectively. And this is at the heart of what parenting and family are all about.

Maria (daughter):

I’ll never forget an experience I had with my mother many years ago when I was a teenager. My father was away on a business trip, and it was my turn to stay up late with Mom. We made hot chocolate, chatted for a while, and then got comfortable in her big bed in time to watch a rerun of Starsky and Hutch.

She was a few months pregnant at the time, and while we were watching TV, she got up abruptly and ran to the bathroom where she stayed for a long time. After a while I realized that something was wrong as I heard her quietly weeping in the bathroom. I went in to find her with her nightgown covered in blood. She had just had a miscarriage.

When she saw me come in, she stopped crying and explained to me in a matter-of-fact way what had happened. She assured me that she was fine. She said that sometimes babies aren’t fully formed the way they should be, and this was for the best. I remember taking comfort in her words, and together we cleaned up and then went back to bed.

Now that I am a mother, I am amazed at how my mother was able to subordinate what must have been heart-wrenching emotions into a learning experience for her teenage daughter. Instead of wallowing in her grief, which would have been the natural thing to do, she cared more about my feelings than her own and turned what could have been a traumatic experience for me into a positive one.

Thus, the fourth level of the tree—the leaves and the fruit—represents your role as a teacher. This means that you explicitly teach others the Primary Laws of Life. You teach empowering principles so that as people understand them and live by them, they come to trust those principles and trust themselves because they have integrity. Having integrity means their lives are integrated around a balanced set of principles that are universal, timeless, and self-evident. When people see good examples or models, feel loved, and have good experiences, then they will hear what is taught. And the likelihood is very high that they will live what they hear so that they, too, become examples and models and even teachers for other people to see and trust. And this beautiful cycle begins again.

This kind of teaching creates “conscious competence.” People can be unconsciously incompetent—they can be completely ineffective and not even know it. Or they can be consciously incompetent—they know they’re ineffective but don’t have the internal desire or discipline to create needed change. Or they can be unconsciously competent—they’re effective but don’t know why. They’re living out positive scripts they’ve been handed by others; they can teach by example but not by precept because they don’t understand it. Or they can be consciously competent—they know what they’re doing and why it works. Then they can teach by both precept and example. It’s this level of conscious competence that enables people to effectively pass knowledge and skill from one generation to another.

Your role as a teacher—in creating conscious competence in your children—is absolutely irreplaceable. As we said in Habit 3, if you do not teach them, society will. And that is what will mold and shape them and their future.

Now, if you’ve done your own interior work so that you are modeling these Primary Laws of Life, if you’ve built relationships of trust by living the Primary Laws of Love, and if you’ve done the organizational work—having regular family times and one-on-ones—then this teaching will be much, much easier.

What you teach will essentially come out of your mission statement. It will be the principles and values that you have determined to be supremely important. And let me tell you here to pay no attention to people who say you shouldn’t teach values until your children are old enough to choose their own. (That statement itself is a “should” statement that represents a value system.) There is no such thing as value-free living or value-free teaching. Everything is hinged and infused in values. You therefore have to decide what your values are and what you want to live by and, since you have a sacred stewardship with these children, what you want them to live by as well. Get them into the wisdom literature. Expose them to the deepest thoughts and noblest feelings of the human heart and mind. Teach them how to recognize the whisperings of conscience and to be faithful and truthful—even when others are not.

When you teach will be a function of the needs of family members, the family times and one-on-ones you set up, and those serendipitous “teaching moments” that present themselves as wonderful gifts to the parent who is watching for opportunity and is aware.

With regard to teaching, I would offer four suggestions:

1. Discern the overall situation. When people feel threatened, an effort to teach by precept—or telling—will generally increase the resentment toward both the teacher and the teaching. It’s often better to wait for or create a new situation in which the person is in a secure and receptive frame of mind. Your forbearance in not scolding or correcting in the emotionally charged moment will communicate and teach respect and understanding. In other words, when you can’t teach one value by precept, you can teach another by example. And example teaching is infinitely more powerful and lasting than precept teaching. Combining both, of course, is even better.

2. Sense your own spirit and attitude. If you’re angry and frustrated, you can’t avoid communicating this regardless of the logic of your words or the value of the principle you’re trying to teach. Restrain yourself or distance yourself. Teach at another time when you have feelings of affection, respect, and inward security. A good rule of thumb: If you can gently touch or hold the arm or hand of your son or daughter while correcting or teaching and you both feel comfortable with this, you’ll have a positive influence. You simply cannot do this in an angry mood.

3. Distinguish between the time to teach and the time to give help and support. To rush in with preachments and success formulas when your spouse or child is emotionally fatigued or under a lot of pressure is comparable to trying to teach a drowning man to swim. He needs a rope or a helping hand, not a lecture.

4. Realize that in a larger sense we are teaching one thing or another all the time because we are constantly radiating what we are.

Always remember that, as with modeling and mentoring, you cannot not teach. Your own character and example, the relationship you have with your children, and the priorities that are served by your organization (or lack of it) in the home make you your children’s first and most influential teacher. Their learning or their ignorance of life’s most vital lessons is largely in your hands.

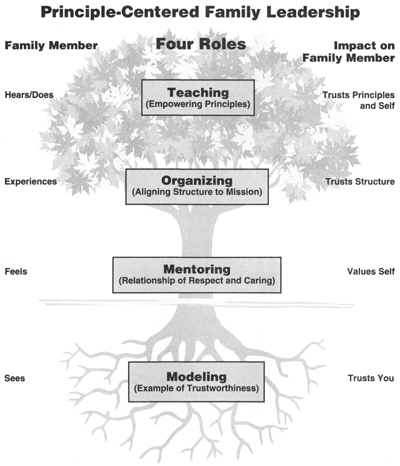

How the Leadership Roles Relate to the Four Needs and Gifts

In the following Principle-Centered Family Leadership model, you will see the four roles—modeling, mentoring, organizing, and teaching. In the left column, notice how the four basic universal needs—to live (physical/economic), to love (social), to learn (mental), and to leave a legacy (spiritual)—relate to those four roles. Remember, too, the fifth need in the family—to laugh and have fun. Notice in the right column how the four unique human gifts also relate to the four roles.

Modeling is essentially the spiritual. It draws primarily upon conscience for its energy and direction. Mentoring is essentially social and draws primarily upon self-awareness as manifested in respecting others, understanding others, empathizing and synergizing with others. Organizing is essentially the physical and taps into the independent as well as the social will to organize time and life—to set up a family mission statement, weekly family times, and one-on-ones. Teaching is primarily mental. The mind is the steering wheel of life as we are guided into a future that we create first in our minds through the power of our imagination.

In fact, the gifts are cumulative at every level so that mentoring involves conscience and self-awareness. Organizing involves conscience, self-awareness, and willpower. And teaching involves conscience, self-awareness, willpower, and imagination.

You Are a Leader in Your Family

As you look at these four leadership roles and how they relate to the four basic human needs and the four human gifts, you can see how fulfilling them well will enable you to create change in the family.

You model: Family members see your example and learn to trust you.

You mentor: Family members feel your unconditional love and begin to value themselves.

You organize: Family members experience order in their lives and grow to trust the structure that meets their basic needs.

You teach: Family members hear and do. They experience the results and learn to trust principles and themselves.

As you do these things, you exercise leadership and influence in your family. If you do them in a sound, principle-centered way, by modeling, you create trustworthiness. By mentoring you create trust. By organizing you create alignment and order. By teaching you create empowerment.

Like it or not, you are a leader in your family, and one way or another you are already fulfilling each of these roles.

The important thing to realize is that no matter where you are on the destination chart, you are doing all four of these things anyway. You may be modeling the struggle for survival, goal setting, or contribution. You may be mentoring by putting people down, “rewarding” success with conditional love, or loving unconditionally. The organization in your family may be a system of repeated disorganization, or you may have calendars, job charts, rules, or even a family mission statement. Informally or formally, you may be teaching anything from disrespect for the law to honesty, integrity, and service.

The point is that, like it or not, you are a leader in your family, and one way or another you are already fulfilling each of these roles. The question is how you are fulfilling them. Can you fulfill them in a way that will help you create the kind of family you want to create?

Are You Managing or Leading? Doing What’s “Urgent” or What’s “Important”?

For many years now I have asked audiences this question: “If you were to do one thing you know would make a tremendous difference for good in your personal life, what would that one thing be?” I then ask them the same question with regard to their professional or work life. People come up with answers very easily. Deep inside they already know what they need to do.

Then I ask them to examine their answers and determine whether what they wrote down is urgent or important or both. “Urgent” comes from the outside, from environmental pressures and crises. “Important” comes from the inside, from their own deep value system.

Almost without exception the things people write down that would make a tremendous positive difference in their lives are important but not urgent. As we talk about it, people come to realize that the reason they don’t do these things is that they’re not urgent. They’re not pressing. And, unfortunately, most people are addicted to the urgent. In fact, if they’re not being driven by the urgent, they feel guilty. They feel as if something is wrong.

But truly effective people in all walks of life focus on the important rather than the merely urgent. Research shows that worldwide, the most successful executives focus on importance, and less effective executives focus on urgency. Sometimes the urgent is also important, but much of the time it is not.

Clearly, a focus on what is truly important is far more effective than a focus on what is merely urgent. It’s true in all walks of life—including the family. Of course, parents are going to have to deal with crises and with putting out fires that are both important and urgent. But when they proactively choose to spend more time on things that are truly important but not necessarily urgent, it reduces the crises and “fires.”

Just think about some of the important things that have been suggested in this book: building an Emotional Bank Account; creating personal, marriage, and family mission statements; having weekly family times; having one-on-one dates with family members; creating family traditions; working together, learning together, and worshiping together. These things are not urgent. They don’t press on us in the same way as urgent matters such as rushing to the hospital to be with a child who has overdosed on drugs, responding to an emotionally hurting spouse who has just asked for a divorce, or trying to deal with a child who wants to drop out of school.

But the whole point is that by choosing to spend time on important things, we decrease the number and intensity of true emergencies in our family life. Many, many issues are talked over and worked out well in advance of their becoming a problem. The relationships are there. The structures are there. People can talk things over, work things out. Teaching is taking place. The focus is on fire prevention instead of putting out fires. As Benjamin Franklin summarized it, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.”

The reality is that most families are overmanaged and underled. But the more quality leadership that is provided in the family, the less management is needed because people will manage themselves. And vice versa: The less leadership is provided, the more management is needed because without a common vision and common value system, you have to control things and people to keep them in line. This requires external management, but it also stirs up rebellion or it breaks people’s spirit. Again, as it says in Proverbs, “Where there is no vision, the people perish.”

This is where the 7 Habits come in. They empower you to exercise leadership as well as management in the family—to do the “important” as well as the “urgent and important.” They help you build relationships. They help you teach your family the natural laws that govern in all of life and, together, institutionalize those laws into a mission statement and some enabling structures.

Without question, family life today is a high-wire trapeze act with no safety net. Only through principle-centered leadership can you provide a net in the form of moral authority in the culture itself, and simultaneously build the mind-set and the skill-set to perform the necessary “acrobatics” required.

The 7 Habits help you fulfill your natural family leadership roles in the principle-based ways that create stability, success, and significance.

The Three Common Mistakes

People often make one of three common mistakes with regard to the Principle-Centered Family Leadership Tree.

Mistake #1: To Think That Any One Role Is Sufficient

The first mistake is to think that each role is sufficient in and of itself. Many people seem to think that modeling alone is sufficient, that if you persist and set a good example long enough, children will eventually follow that example. These people see no real need for mentoring, organizing, and teaching.

Others feel that mentoring or loving is all-sufficient, that if you build a relationship and constantly communicate love, it will cover a multitude of sins in the area of personal example and render organizational structure and teaching unnecessary, even counterproductive. Love is seen as the panacea, the answer to everything.

Some are convinced that proper organizing—which includes planning and setting up structures and systems to make good things happen in relationships and in family life—is sufficient. Their families may be well managed, but they lack leadership. They may be proceeding correctly but in the wrong direction. Or they’re full of excellent systems and checklists for everybody but have no heart, no warmth, no feeling. Children will tend to move away from these situations as soon as possible and may not desire to return—except perhaps out of a sense of family duty or a strong spiritual desire to make some changes.

Others feel that the role of parents is basically to teach by way of telling and that explaining more clearly and consistently will eventually work. If it doesn’t work, it at least transfers responsibility to the children.

Some feel that setting the example and relating—in other words, modeling and mentoring—are all that is necessary. Others feel that modeling, mentoring, and teaching will suffice, and organizing is not that important because in the long run, it’s relationship, relationship, relationship that really counts.

This analysis could go on, but it essentially revolves around the idea that we don’t really need all four of these roles, that only one or two is sufficient. But this is a major—and a very common—mistake. Each role is necessary, but absolutely insufficient without the other three. For example, you might be a good person and have a good relationship, but without organization and teaching, there will be no structural and systemic reinforcement when you are not present or when something happens that negatively affects your relationship. Children need not only to see it and feel it but also to experience it and hear it—or they may never understand the important laws of life that govern happiness and success.

Mistake #2: To Ignore the Sequence

The second mistake, which is even more common, is to ignore the sequence: to think that you can explicitly teach without having the relationship; or that you can build a good relationship without being a trustworthy person; or that verbal teaching is sufficient and that the principles and laws of life contained in this verbal teaching do not need to be embodied into the patterns and process, the structures and systems of everyday family life.

Just as the roots of the tree bring nutrients and life to every other part of the tree, so your own example gives life to your relationships, to your efforts to organize, to your opportunities to teach.

But just as the leaves on the tree grow out of the branches, the branches grow out of the limbs, the limbs grow out of the trunk, and the trunk grows out of the roots, so each of these leadership roles grows out of those that precede it. In other words, there is an order here—model, mentor, organize, teach—that represents the true inside-out process. Just as the roots of the tree bring nutrients and life to every other part of the tree, so your own example gives life to your relationships, to your efforts to organize, to your opportunities to teach. Truly, your modeling is the foundation of every other part of the tree. And every other level is a necessary part of those that grow out of it. Effective family leaders recognize this order, and whenever there’s a breakdown, use the sequence to help diagnose the source of the problem and take the steps necessary to resolve it.

In Greek philosophy human influence comes from ethos, pathos, logos. Ethos basically means credibility that comes from example. Pathos comes from the relationship, the emotional alignment, the understanding that is taking place between people and the respect they have for one another. And logos deals with logic—the logic of life, the lessons of life.

As with the 7 Habits, the sequence and the synergy are the important things. People do not hear if they do not feel and see. The logic of life will not take root if you don’t care or if you lack credibility.

Mistake #3: To Think That Once Is Enough

The third mistake is to think that when you have fulfilled these roles once, you don’t have to do them anymore—in other words, to look at fulfilling these roles as an event rather than as an ongoing process.

Model, mentor, organize, and teach are present-tense verbs that must continually take place. They must go on day in and day out. Modeling or example must always be there, including the example of apologizing when we get off course. We must continually make deposits in the Emotional Bank Account because yesterday’s meal does not satisfy today’s hunger, especially in family relationships where expectations are high. Because circumstances are constantly changing, there is always the role of organizing to accommodate that changing reality so that the principles are institutionalized and adapted to the situation. And explicit teaching must constantly go on because people are continually moving from one level of development to another, and the same principles apply differently at different levels of development. In addition, because of changing circumstances and age and stage realities, new principles apply and come into play that must be taught and reinforced.

In our own family we’ve discovered that each child represents his or her own unique challenge, unique world, and unique needs. Each represents a whole new level of commitment and energy and vision. We even sensed with our last child—out of nostalgia for the past glorious years of raising a family—a tendency to overindulge. Perhaps this comes from our own need to be needed, even though our mission statement focuses on producing independence and interdependence.

Joshua (son):

Being the youngest of nine has its advantages. The older kids are always complaining and moaning to Mom and Dad that I’m spoiled and get away with murder. They say that Mom and Dad aren’t half as strict as they used to be, that I don’t have to work and slave like they did. They ask, “What do you do anyway besides pick up your room and take out the garbage?”

They tell me that when they were growing up, it was harder to become an Eagle Scout, their schoolteachers were meaner and tougher, and Mom and Dad weren’t nearly as well off. They complain that while they have to stay home and put food on the table, I get to go on trips. The boys say they used to lift weights and work out and have muscles, but now they have to be responsible—and that’s why they can’t beat me in a game of tennis or basketball anymore. They say I’d better buckle down and get straight A’s if I want to get into a good college, and I’ll never go to graduate school if I read Cliffs Notes instead of doing my own thinking. They tell me that’s why I should listen to their advice and not make the same mistakes they did. They also say for sure I’ll get to go “pro” in whatever sport I choose because they’ve all offered to train me. And if I just do what they say, my life will be a lot easier than they had it.

Even as I write this book, I find myself increasingly grateful for the significance of the airplane metaphor and the opportunity to constantly change and improve and to apply what I’m trying to teach. This has been a forceful reminder to me that we need to keep on keeping on, to endure to the end and respect the laws that govern growth, development, and happiness in all of life. Otherwise, we become like the well-intended person who, seeing a butterfly struggling to come out of its cocoon, wildly swinging its wings to break the one small tendon that holds it to the old form, the old structure, out of a spirit of helpfulness takes a penknife and cuts the remaining tendon. As a result, the butterfly’s wings never fully develop and the butterfly dies.

So we must never think that our work is done—with our children, our grandchildren, even our great-grandchildren.

Once in the Florida Keys I spoke to a group of extremely wealthy retired couples about the importance of the three-generation family. They acknowledged they had essentially compartmentalized their sense of responsibility to their grown children and their grandchildren. Family involvement was not the central force in their lives; it was an occasional “holidays only” guilt reliever justified by the rationale of helping the kids to become independent from them. But as they opened up and leveled, many acknowledged their sadness in this compartmentalization, even abdication, and resolved to become engaged with their families in a number of new ways. Helping our children become independent is important, of course, but this kind of compartmentalized attitude will never create the intergenerational family support system that is needed today to deal with the onslaught of the culture on the nuclear family.