CHAPTER 4

CHANGE IS EASY —IF YOU KNOW HOW TO DO IT

TURN YOUR RUTS INTO SUPERHIGHWAYS OF SUCCESS

People don’t change when they see the light, only when they feel the heat.

PASTOR RICK WARREN

Change is easy —if you know how to do it. But it is hard if you keep doing things that reinforce negative behavior circuits in the brain. If you were an anxious child, for example, anxiety built specific connecting highways (neural networks) in your brain. Odds are you still feel anxious as an adult unless you did something to rewire them. If you deal with pressure by drinking alcohol or lashing out at those around you, you are likely to continue that behavior whenever you feel stressed —unless you develop a new model of doing things.

Once the brain learns how to do something, it becomes wired to do it automatically and reflexively through a process called neuroplasticity. New learning and change take strategy, effort, and resources, which is why we often get stuck. I find this to be true in my own life and bet you do too. Depending on what you’ve taught your brain to do, this neuroplasticity can help you develop and maintain good habits, or it can cause you to get stuck in ruts that steal portions of your life. An example of the former: When a waiter brings bread to my table at a restaurant, I now automatically request that it be taken away. An example of the latter: For years, my e-mail and smartphone controlled me.

When neurons fire together, they wire together, through a process called long-term potentiation (LTP), and habits and responses become an ingrained part of your life. LTP occurs when the brain learns something new, whether it’s good or bad, and causes networks of brain cells to make new connections. Early in the learning process the connections are weak, but over time, as behaviors are repeated, the networks become stronger, making the behaviors more likely to become automatic, reflexive, or habitual. At this point, the networks are said to be “potentiated.”

With the brain, what you practice and reinforce becomes your reality. One of my patients, Hank, learned that alcohol powerfully calmed his anxiety, and he couldn’t break the wiring underlying his addiction until the pain of losing his family short-circuited the connections. After repeated explosions at home, Hank’s children’s brains learned they could not trust that they would be safe and became hypervigilant, always watching for the next bad thing to happen. Fear became potentiated in their brains. The stronger the emotion, the more powerful the wiring or connections in the behavior. Some fears or habits will develop after repeated mild-to-moderate exposures, but others will develop after just one exposure if it is intense enough, such as after physical abuse, a fire, robbery, or rape.

Kindling is an important process to understand as it relates to the brain and change. When a scientist passes a low-volt electrical current through a nerve cell, initially nothing happens, but as the voltage is raised to a certain threshold, the cell will begin to fire. If the electrical intensity remains high enough for a long enough period of time, the cell will become kindled, meaning it is more sensitive. The voltage can then be lowered, and it will still cause nerve cell firing. Every time an emotional explosion happened at home, Hank’s kids experienced intense nerve cell firing in the limbic or emotional centers of their brains. Over time, as the trauma continued, it took less and less drama to trigger anxious feelings. Even years later, small things, such as an awkward look from a store clerk, could trigger big emotional reactions in the now-grown children.

Your brain has roughly 100 billion brain cells, or neurons. Throughout the day they are either at rest or firing to spark your thoughts, behaviors, and emotions. The activity becomes more intense in high-stress situations, such as the one described above. If you experience enough anxious moments as a child, your neurons may fire faster even at rest, making you feel on edge. As an adult, your neurons are still on guard, ready to fire with little provocation, like a hairpin trigger. Your son drops a plate, and the crashing noise makes you flip out. Someone raises his voice to make a point, and you start feeling panicky. You see someone intoxicated at a party, and you quickly leave, even though you wanted to stay. Because the resting state of your brain is elevated, which we have seen in our brain imaging work on posttraumatic stress disorder, you may be more inclined to drink alcohol, take painkillers, or overeat as a way to soothe your brain. Now your brain has become stuck in a rut, which the Oxford Dictionary, in one definition, describes as “a habit or pattern of behaviour that has become dull and unproductive but is hard to change.”[100]

Whatever behaviors formed or you allowed into your life, productive or not, are the ones that are likely to continue. This is why it is critical to assess your automatic behaviors and ask yourself if they are helping or hurting you.

Be very careful of the behaviors you allow into your life. They may end up hijacking it.

The exciting news is that you can change unwanted behaviors. Practicing good behaviors, such as getting seven to eight hours of sleep a night, exercising, and saying no to constantly checking your gadgets, strengthens the willpower circuits in the brain. Alternatively, giving in to negative behaviors, such as emotional explosions, mindlessly eating cookies at work, guzzling sodas, consuming excessive amounts of alcohol, procrastinating, or giving in to the urge to look at Internet pornography, strengthens those particular circuits. Whatever behaviors you engage in are the ones you are likely to continue doing. If you allow yourself to yell at your children or be rude to your spouse or coworkers, you are much more likely to do it again and again.

No one wants to be controlled by things that were done to them or by their own past negative choices. To feel better fast, you need to learn to make deliberate choices that will create new pathways in your brain. In this chapter, we’ll explore more about how ruts and negative behaviors develop in the brain and how you can quickly develop more positive habits, while becoming more adaptable and flexible. When you repeatedly engage in positive behaviors, you build the superhighways of success that help you reflexively do the things you want to do. I’ll show you how you can use your brain to change your habits.

WHY WE GET STUCK IN RUTS: HABITS AND THE BRAIN

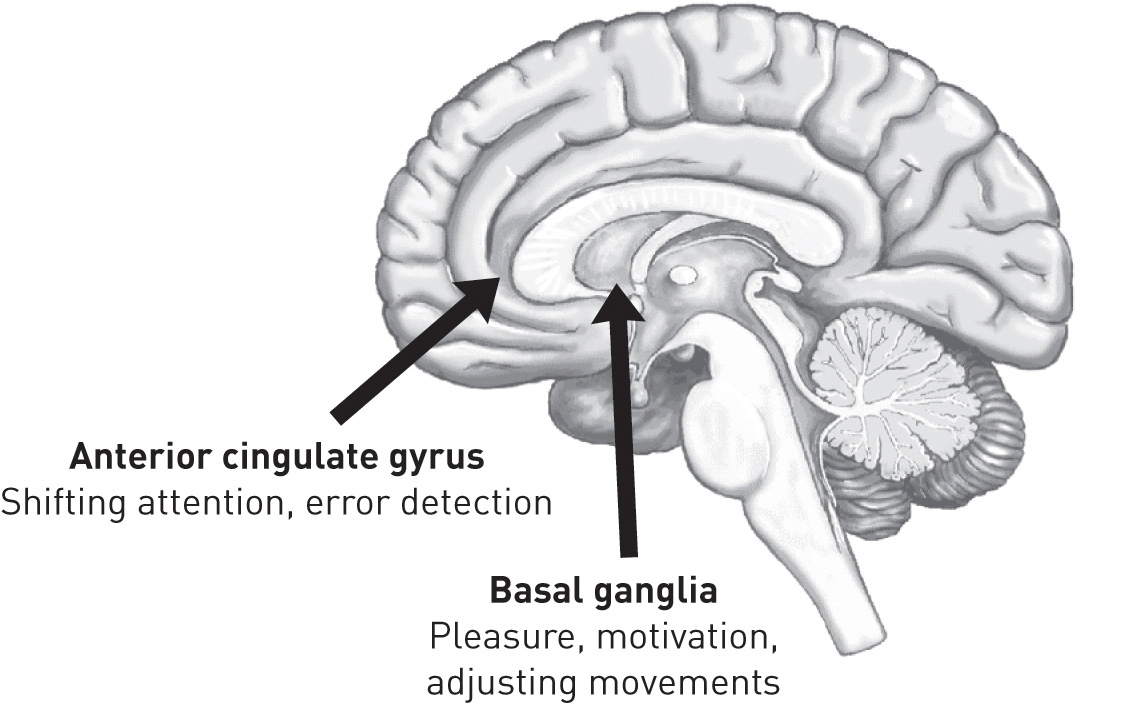

Along with long-term potentiation and kindling, it is important to know about two areas of the brain that are involved with mental flexibility and habit formation: the anterior cingulate gyrus, which I think of as the brain’s gear shifter, and the basal ganglia, where habits are formed and sustained.

INSIDE VIEW OF THE BRAIN

The Brain’s Gear Shifter

There’s an area deep in the frontal lobes called the anterior cingulate gyrus, or ACG, which allows us to shift our attention, go from thought to thought, move from idea to idea, see options, go with the flow, and cooperate, which involves getting outside ourselves to help others. The ACG is also involved in error detection. If you come home and see the front door wide open, for example, even though you know you locked it, it triggers an appropriate danger reaction in your mind.

When the ACG is healthy, we tend to be flexible, adaptable, and cooperative, learn from our mistakes, and effectively notice when things are wrong. When it is underactive, often due to head trauma or exposure to damaging toxins, we tend to be quiet and withdrawn. Alternatively, when the ACG is overactive, often due to low levels of the calming neurotransmitter serotonin, we tend to get stuck on negative thoughts (obsessions) or negative behaviors (compulsions/addictions) and be uncooperative. Serotonin-enhancing strategies, such as taking medicine that increases the availability of serotonin (SSRIs, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), have been used for decades to treat anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Practically speaking, getting stuck has many different potential manifestations, including worrying, holding grudges, and becoming upset if things don’t go your way. On the surface, people with high ACG activity may appear selfish (“My way or the highway”), but from a neuroscience standpoint, they’re not selfish; they’re rigid. Inflexibility causes them to automatically say no even when saying yes may be their best choice. They have trouble seeing options and tend to be argumentative and oppositional. Plus, they tend to see too many errors —in themselves, their spouses, kids, coworkers, and organizations, such as schools, government, and churches.

In doing research on our extensive brain imaging/clinical database, we discovered that patients who have OCD or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) show increased activity in the ACG. In both disorders, people get stuck on negative feelings, thoughts, and behaviors (see “When the Gear Shifter and Enabler Are Over- or Underactive” on page 74). Knowing this information gives us the clue that strategies to boost serotonin could help increase cognitive flexibility to enable change. Research suggests that is indeed true[101] —more on this below (see Strategy #1, pages 76–77).

The Brain’s Enabler

Deep in the brain are two large structures called the basal ganglia (BG). Among other roles, they are involved with integrating thoughts, emotions, and movement, which is why we jump when we get excited or freeze when we become scared. The BG also help to shift and smooth motor behavior and may be involved in habit formation, according to studies. When they are overactive, our research and that of others suggests, people struggle with generalized anxiety, dislike uncertainty, and avoid conflict.[102] With increased BG activity we also see repetitive behaviors, such as tics, nail biting, and teeth grinding, as well as compulsions, such as hand washing and checking locks. When the BG are underactive, people tend to have low motivation, poor handwriting, and trouble feeling pleasure. They are also more vulnerable to attentional problems and movement disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease.

WHAT DO RUTS LOOK LIKE IN YOUR LIFE?

Getting stuck in a rut can take many forms, including addictions, depression, impulse-control issues, bad habits, staying in difficult or abusive relationships, or maintaining outdated business processes. Worry, holding grudges, obsessive thinking, compulsive behaviors, persistent anger, rude behavior, and being oppositional or argumentative can also be caused by ruts in the brain.

Check the questions that apply to you.

Do you dislike change?

Do you dislike change? Do you tend to get stuck in loops of thinking?

Do you tend to get stuck in loops of thinking? Do you struggle with repetitive, negative thoughts?

Do you struggle with repetitive, negative thoughts? Do you have difficulty seeing options in stressful situations?

Do you have difficulty seeing options in stressful situations? Do you tend to hold on to your own opinions and not listen to others?

Do you tend to hold on to your own opinions and not listen to others? Do you get locked into a course of action, even though it may not be good for you?

Do you get locked into a course of action, even though it may not be good for you? Do you tend to automatically say no without thinking?

Do you tend to automatically say no without thinking? Do you get upset if you are surprised or if things don’t go the way you expect they should?

Do you get upset if you are surprised or if things don’t go the way you expect they should? Do you struggle with compulsive behaviors, such as hand washing, checking locks, counting, or spelling?

Do you struggle with compulsive behaviors, such as hand washing, checking locks, counting, or spelling? Do you tend to be oppositional or argumentative?

Do you tend to be oppositional or argumentative? Have you been diagnosed with OCD or PTSD?

Have you been diagnosed with OCD or PTSD?

The more questions you checked, the more likely you have an ACG that is working too hard. Where do you feel stuck in your life?

Personal habits

Personal habits Relationships

Relationships Health

Health Work

Work Money

Money

Think about your day and the automatic behaviors you engage in without much thought, such as

- Using your cell phone or other gadgets

- Brushing your teeth

- Making coffee or tea

- Eating breakfast, healthy or not

- Being polite or curt to your kids or partner

- Reading the news

- Answering e-mail

- Exercising

- Showering

- Driving to work

- Texting with family or friends

- Snacking

- Eating lunch by yourself or with coworkers

- Eating dinner

- Having dessert

- Engaging in bedtime rituals

Ask yourself if the way you accomplish each of your behaviors is helping or hurting you. Do you lunch on salad and soup or wolf down fast food? Do you take regular breaks from e-mail and texting or spend endless hours on one or both? Do you listen to soothing music while driving or tailgate whenever you get behind the wheel?

Have you tried to change habits that have not been helpful but failed miserably over time? That happens to most people because they do not understand the brain. As we have seen, it is in your brain where you become adaptable, flexible, and able to change, or it is in your brain where you get stuck in a rut.

NINE STRATEGIES TO QUICKLY TURN YOUR RUTS INTO SUPERHIGHWAYS OF SUCCESS

Scientists have studied how the brain can facilitate change, whether it is to lose weight, beat an addiction, stay off your computer, be more successful at work, change personal habits, or revise business processes. Based on this research, together with our clinical experience at Amen Clinics, here are nine simple brain-based habits to promote change.

Strategy #1: Naturally boost serotonin.

When serotonin levels are low, the ACG and BG tend to be more active, which can inhibit change and also contribute to mental inflexibility and getting stuck on negative thoughts or behaviors. Increasing serotonin can help calm these areas of the brain.[105] This can be done with four simple strategies:[106]

- Physical exercise increases the ability of tryptophan, the amino acid precursor of serotonin, to enter the brain. Walking, running, swimming, or playing table tennis will help you feel happier and more mentally flexible. Exercise alone has been found to treat depression, with effectiveness similar to an SSRI antidepressant.[107] Whenever you feel stuck in a rut, get moving.

- Bright light exposure has been shown to increase serotonin and is a natural treatment for seasonal depression and premenstrual tension syndrome, as well as depression in pregnant women.[108] Depression and inflexibility are more common in winter and in places where sunlight is lacking. To improve your mood and increase cognitive flexibility and learning, get more sun or use bright light LED therapy,[109] which is a standard treatment for seasonal depression.

- Eating foods that contain tryptophan can increase serotonin levels. Whenever you feel stuck in a rut, combine tryptophan-containing foods, such as eggs, turkey, seafood, chickpeas, nuts, and seeds, with healthy carbohydrates, such as sweet potatoes and quinoa, to elicit a short-term insulin response that drives tryptophan into the brain. Dark chocolate also increases serotonin.[110]

- Nutritional supplements can also raise brain levels of serotonin. My favorite ones are L-tryptophan, 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), and saffron.[111] See chapter 10 for more information on these.

Strategy #2: Define what you want and why.

To help you make better behavioral choices, your BG and ACG need your prefrontal cortex to step in and take charge. For this to occur, it helps if you clarify which behaviors you want to change. Your brain makes happen what it sees. What patterns are making you feel worse by contributing to your anxiety, anger, stress, or worry? What ruts would you like to turn into superhighways of success, leaving you feeling better? Write them out. Create a vivid and believable “Future of Success” in detail. How will you feel in one, five, and ten years if you consistently engage in the new behavior? You could write, “I’ll feel amazing, healthy, energetic, cognitively better than I have ever been, in control.” Next, envision a vivid and believable “Future of Failure” in detail. How will you feel in one, five, and ten years if you do not stop this negative behavior? What will your life look like going forward? You might write, “I’ll feel embarrassed, lose my family, have a smaller brain, suffer from early disease and death!”

Define what you want, and then ask yourself if your behavior is getting you what you want. If not, be clear with yourself that every time you engage in the wrong behavior, it is strengthening your brain to do the wrong thing. Whenever you do the right thing, it is beginning to strengthen those circuits instead. Practice does not make perfect; it makes the brain do what you practice. Perfect practice makes perfect.

Strategy #3: Assess your readiness for change.

Remember this joke? “How many psychiatrists does it take to change a light bulb? One, but the light bulb really has to want to change.”

Likewise, your consent and motivation are critical elements of change. Are you ready to eliminate the ruts in your life? One of my favorite techniques to assess motivation for change is called Motivational Interviewing (MI). It helps people clarify their conviction and confidence to do things differently and uses questions to guide them through six stages of change. Ambivalence and uncertainty are the enemies of change.

When you meet a friend who . . . drinks too much; smokes a pack per day; is obese; doesn’t exercise; or has high blood pressure and yet is unwilling to take your advice, change her lifestyle, or comply with recommendations from her doctor, how do you feel?

When your adolescent ADHD son . . . refuses to turn down the music and do homework, smells of cigarette smoke, hangs out with friends who drink, and stops participating in healthy activities, how do you feel?

If you are like most people, you feel sad, scared, helpless, frustrated, and unsure of how to help. You may respond with judgment, unwanted advice, or scary stories of the risks these people face, hoping to help them see the light. For those of you who have tried this approach (I certainly have), how’s it been working for you? I want to help you become more effective at facilitating real behavioral change in yourself, your family, and your friends. Understanding these six stages of change will help you assess your own or someone else’s readiness for change and increase your conviction and confidence to make it happen.

SIX STAGES OF CHANGE

Decisions to make lifestyle changes are the result of a natural process that takes place in stages over time. Each stage is the foundation for the next one. Let’s talk about how to recognize, reinforce, and accelerate the natural process throughout these stages.

Change starts by determining a person’s readiness for it. First, ask yourself (or a loved one) an open-ended question about the behavior to be changed: Would you consider . . .

- Losing weight?

- Quitting smoking?

- Getting more exercise?

- Changing your eating habits?

- Cutting back or abstaining from alcohol?

- Going to bed earlier?

- Limiting your e-mail?

If you answer “no,” you’re in Stage I, which is called the pre-contemplation stage. You are not thinking about a change, you are not ready for it, and you do not believe you can accomplish it.

Stage I: I Won’t or I Can’t. This is often called denial, when the cons of change outweigh the pros. “I won’t change” means you have little to no motivation to change; “I can’t change” means you lack the capability or confidence to change. In this stage either the negatives of changing the behavior (such as smoking, overeating, or looking at Internet pornography) seem to outweigh the positives, or you are in denial, lack knowledge or conviction to change, are skeptical, or feel powerless to change. If you or a loved one is in this stage, you can increase your conviction by asking, “If I decided to change, how would it benefit me?” Focusing on benefits is an important first strategy to help move someone to Stage II.

If you answer “maybe,” you are in Stage II, called the contemplation stage. You are thinking about changing but have not yet decided.

Stage II: I Might. The cons of change equal the pros, but ambivalence and lack of confidence are still issues. To boost your confidence, ask yourself three questions:

- If I really decide to change, do I think I can do it?

- What would prevent me from changing; what are the barriers?

- How do I think I can start changing; what are the strategies?

In this stage, it helps to focus on the benefits of changing and collect information that might help you develop solutions. I was once visiting my niece, who had just started seventh grade in a new school. She was struggling in music, and she told me the teacher was not helpful. Her instrument was the xylophone, and she had no idea how to play it. She lacked confidence. Together, we went to YouTube and searched the term “How to play the xylophone.” In 20 minutes she was able to play a simple song, and her confidence soared.

If you answer “yes,” you are in Stage III, called the determination stage. You are making the decision to change.

Stage III: I Will. The benefits of change now outweigh the drawbacks, and you can now develop a plan to make it happen.

If you answer, “I am doing it,” you are in Stage IV, called the action stage.

Stage IV: I Am. In this stage you build confidence and look for any barriers that might derail you. Long-term potentiation (LTP) is beginning to occur in this phase, meaning that you are beginning to rewire your brain.

If you answer, “I am still doing it,” you are in Stage V, called the maintenance stage.

Stage V: I Still Am. LTP is being strengthened and the new behavior feels more reflexive or automatic, but you are still on the lookout for barriers and traps.

If you answer, “I fell off the wagon,” you are in Stage VI, called the relapse stage.

Stage VI: Whoops! Most people backslide at some point. It is a natural part of change. When you fall off the wagon, it is critical to ask why, learn from your mistake(s), and start again. Some people have to start over at Stage I. Most people jump back in at Stage III or IV.

In general, the job of people in Stages I and II is enhancing their motivation and conviction, while those in Stages III through V focus on sustaining motivation and engagement, eliminating obstacles, and overcoming barriers. If someone is in the “I Won’t or I Can’t” phase, the first step is to work on conviction and confidence until they make the decision “I Will.” Then they can focus on the skills that will help them to engage in the new behavior.

For each behavior you want to change, ask yourself, “Which stage am I in?” and “How will it benefit me to change my behavior?”

By embracing change, we learn a principle inspired by Aristotle’s teachings: “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, then, is not an act, but a habit.”[112]

Strategy #4: Know what you need to do.

What are the new behaviors you need to master to be successful? For any problem, such as losing weight, overcoming an addiction, calming your temper, or avoiding distractions, it is critical to know which important behaviors will help you reach your goal, then practice them over and over. Here are a few general examples, followed by suggestions for specific issues:

- Make sure your blood sugar is stable to keep the PFC healthy

- Get enough sleep to keep the PFC healthy

- Take proper nutritional supplements

WEIGHT LOSS

- Start a food journal to monitor what you eat

- Stop drinking your calories; drink primarily water

- Upgrade the quality of your food

- Eliminate foods you may be intolerant of or allergic to, such as milk or wheat products

- Avoid places that trigger food cravings

- Add in exercise

- Learn to control your thoughts, so you don’t have to medicate them with food or drugs

- Get your blood work done so you do not miss an important contributor, such as low vitamin D, thyroid, or testosterone levels

OVERCOMING ADDICTION

- Avoid friends who use substances

- HALT —don’t let yourself get too hungry, angry, lonely, or tired

- Learn to control your thoughts, so you don’t have to medicate them with drugs

- Attend 12-step groups on a regular basis if they help you

- Work to keep your temper under control

- Eliminate the ANTs (see discussion of automatic negative thoughts in chapter 5)

- Learn diaphragmatic breathing

- Consider SPECT to see if you had a brain injury in the past that needs to be treated

- Establish group support

ELIMINATING DISTRACTIONS

- Have defined periods where you turn off your gadgets

- Stop texting while walking

- Put away your tablet, smartphone, and other tech items at least an hour before bed

Just as in the story about my niece, you can google how to change virtually any behavior. Once you have the desire and motivation, learn the critical steps to take.

Strategy #5: Identify your most vulnerable moments and learn from your mistakes.

It’s important to know when you are most vulnerable. Be curious about your behavior, not furious at your slipups or mistakes. Investigating setbacks can be extremely instructive if you take the time to really analyze them.

Eloise, 42, a highly successful realtor, came into my office feeling sad and ashamed. I initially saw her for panic attacks and drug use. Within a few months she had made great progress and completely stopped using drugs. But after a major fight with her boyfriend, she slipped and went on a weekend binge.

“I’ll never be free of this behavior,” Eloise told me. Then she stopped herself and said, “I know that’s not true.” We had worked on her thoughts. “I am just so mad at myself.”

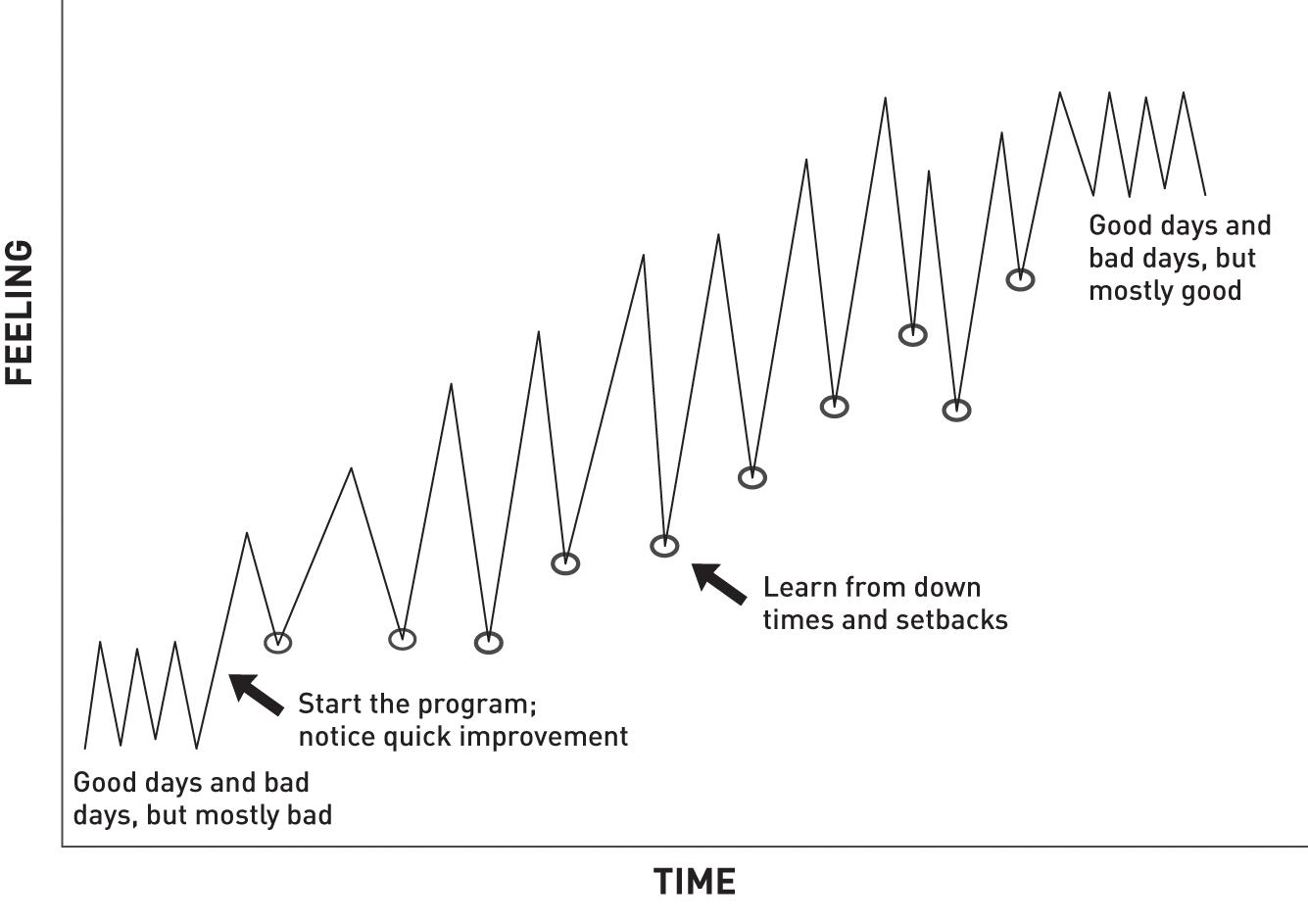

CHANGE DIAGRAM

I went to the whiteboard in my office and drew the graph on how people change.

“When people come to see me as patients, they have good days and bad days, but usually their days are not very good,” I said. “Then we work together to change things, and they get better. But they never just get better and stay there. There is an up-and-down course. Over time they feel much better and usually stay that way. But it is the down times, the slipups, the setbacks that teach us most of what we need to know —if we embrace them and take time to learn from them. We have to turn bad days into useful information.”

When Rahm Emanuel was the White House chief of staff, he once said that you never want a serious crisis to go to waste.[113] Slipups and setbacks are the same. Study them, learn from them, be curious. In my experience, the most successful people embrace their mistakes so they can learn from them.

Eloise and I investigated her relapse from a brain science perspective. The week before her relapse, a home fell through escrow and she lost sleep over it. In addition, her eating became more erratic, she did not take time to work out, and she skipped her supplements. Poor sleep, inconsistent eating habits, and a lack of exercise all contributed to lower activity in and blood flow to her brain. Combining those factors with a stressful week and relational conflict triggered more negative thoughts, and she relapsed. Rather than judge herself as a bad person, I encouraged her to be a good student and learn from the episode. She needed to be more diligent with sleep, exercise, and good food, along with learning how to master her mind (see Strategy #4).

I asked Eloise, “Do you have a GPS system in your car that talks to you?”

“Yes,” she replied.

“When you make a wrong turn, what does the voice say to you?”

“‘Make the next legal turn,’ or something like that,” she said.

“Does it start yelling or swearing at you?” I asked.

With a smile she said, “They wouldn’t sell many of those GPS systems. Of course not.”

“But isn’t this what you are doing to yourself when you make a mistake? Instead of beating yourself up, whenever you make a mistake, learn from it, turn around, and go in a better direction.”

Be both the investigator and the subject! Change is a process that occurs in steps. If you pay attention, the bad times can be more instructive than the good times. Journaling is key to helping keep track of both. Know when you are most vulnerable (not sleeping, forgetting to eat breakfast, waiting too long between meals, attending too many parties or social gatherings, etc.).

Strategy #6: Develop “if-then” plans to overcome your vulnerable moments.

Once you know when you are vulnerable, you can create contingency plans to overcome unwanted behaviors. Psychology professor Peter Gollwitzer from New York University has published extensive research on behavior change. He recommends that people create “if-then” scenarios that spell out how they’ll break unwanted habits.[114] For example, if x (situation) happens, then I will do y (preplanned action).

Dr. Gollwitzer wrote in Fortune magazine,

The most effective plans are those that specify when, where and how you want to act on your goals by using an “if-then” format. Take drinking too much in the company of your friends as an example. In the “if” part of the plan, you identify the critical situation that usually triggers your bad habit. Perhaps the trigger is being offered a drink by your friends. In the “then” part, you specify an action that can halt accepting the offer such as responding to it by saying that you prefer a glass of water today. And then you link the “if” and the “then” parts together by making an “if-then” plan: “If on Friday evening my friends offer me a drink, then I will answer: I prefer to have a glass of water today!”[115]

As insanely simple as it sounds, the research is impressive. If-then strategies have helped people reach their goals in dieting and athletics,[116] boosted physical activity in women by more than an hour a week compared to a control group,[117] increased the consumption of fruits and vegetables,[118] and helped to regulate emotions, including fear and disgust.[119] Using this simple technique has been shown to increase activity in the PFC,[120] which can help override the brain’s automatic or reflexive behaviors from the ACG and BG. It has even been shown to help normalize the brain in children with ADHD.[121] Making your “if-then” plans known to others also improves your ability to stay on track.[122]

In a similar way, I often tell my patients that when it comes to brain health, the two most important words in the English language are then what. If I do this, then what happens? Thinking ahead helps to prevent a lot of unwanted trouble.

CREATE SIMPLE “IF-THEN” RULES FOR VULNERABLE TIMES, SUCH AS

- If I am tempted to eat unhealthy foods, then I’ll at least eat the healthy ones first.

- If I find myself becoming irritated at someone, then I will take three deep belly breaths before I say anything else.

- If I am anxious about a meeting, then I will write down my anxious thoughts, which helps to dispel them.

- If I can cheat on my diet, then it can only be after reading my One-Page Miracle (see pages 190–193) and calling supportive friends (introduces delay and social support).

- If I become aware of the impulse to eat something that is not healthy, then I will focus on something else —like taking a walk, reciting a poem, or drinking a glass of water —until the impulse goes away.

Strategy #7: Reframe your pain.

To succeed at changing, you have to disarm your impulses and make the right choices pleasurable.

The only way you can sustain change is to change what brings you pleasure!

Learn how to find what you love about not being inebriated, or identify great low-calorie, highly nutritious food. Discover how good it feels when you’re not tied up with anxiety. One of my friends told me she hated exercise, but she loved walking with her children. Mind-set is key.

Connect to who you are becoming, and think like a healthy person. How would a healthy person order this meal or act in this vulnerable situation? Willpower is a skill you can develop. If you can distract yourself for just a minute, temptations often go away.

Be careful about giving in to your own bad behavior! You may be causing your own behavior disorder. I was once with a patient who was struggling with her weight. She said she often felt as though she had to give in to her cravings. She had two teenage daughters, one of whom I was seeing because she had tantrums whenever she did not get her way. I asked this mother how her daughter would do if Mom always gave in to her temper tantrums —would she get better or worse? “Worse, of course,” she replied. When you give in to your own tantrums or cravings, you are creating your own internal behavior disorder, which can ruin your health and kill you before your time. Be a loving, effective parent to yourself.

Strategy #8: Turn accomplices into friends.

Whom you spend time with matters! Cultivating bad habits —and good ones —is a team sport, and you need friends rather than accomplices. Accomplices encourage or are complicit with your negative behaviors, while friends, mentors, or coaches are people who support your positive behaviors. Ask for their help. Adding friends improves your chances for success up to 40 percent, and this is especially true for weight loss and fitness.

If you want to change your behavior, either you need to stop seeing your accomplices or turn them into friends, or you need to change your friends. Many accomplices can become friends if you have crucial conversations with them. Explain what they can start doing, stop doing, and continue doing to help you.

IN YOUR LIFE, ARE THESE PEOPLE ACCOMPLICES OR FRIENDS?

- Spouse

- Children

- Parents

- Grandparents

- Siblings

- In-laws

- Aunts, uncles, cousins

- Friends

- Neighbors

- Bosses

- Coworkers

- Teachers

- Classmates

- Students

- School administrators

- Church members or staff

- AA participants

- Community club members

- Gym friends

Identify your five most powerful friends who will support your good habits, as well as five accomplices who make it less likely you will succeed in changing your behavior. Spend more time with the people who will help you.

Strategy #9: Use tiny behaviors to create massive change.

Small daily improvements are the key to staggering long-term results.

As I mentioned in the introduction, Amen Clinics partnered with Professor BJ Fogg, director of the Persuasive Tech Lab at Stanford University, and his sister, Linda Fogg-Phillips, to help our patients with behavior change. One of their key suggestions is to take baby steps. We have been sprinkling these “Tiny Habits” throughout the book, since developing those small new behaviors is one of the best ways to make change a reality in your life and slowly builds new circuits or superhighways in your brain.

Based on his research, Dr. Fogg has found that change is easy when designed properly. He said,

You don’t have to be perfect. No one is. You just need to keep working on it.

Change happens better and faster if you are playful, flexible, and iterative.

Few people change all at once; change occurs most effectively when it is small and incremental over time. Relying solely on willpower is usually a prescription for failure.

Know your motivation —when motivation is high you can do hard things. If you are just diagnosed with diabetes, for example, cutting out sugar becomes much easier than it would be if you simply want to lose a few pounds. When motivation is low, you have to make things as easy, simple, and “tiny” as possible. If you just want to lose a few pounds, you could start by packing your lunch two days a week, instead of eating out.

When things don’t work, be curious, not furious. Ask why and re-assess. It may take several tries.[123]

Our brains are wired to keep doing what we’ve always done —but we can change the ruts into superhighways of success. Making small changes is the secret to feeling better fast, and it can lead to taking on big changes that will ensure those feelings last.

NINE STRATEGIES TO EMBRACE CHANGE AND TURN YOUR RUTS INTO SUPERHIGHWAYS OF SUCCESS

- Naturally boost serotonin.

- Define what you want and why.

- Assess your readiness for change.

- Know what you need to do.

- Identify your most vulnerable moments.

- Develop “if-then” plans to overcome your vulnerable moments.

- Reframe your pain.

- Turn accomplices into friends.

- Use tiny behaviors to create massive change.

TINY HABITS THAT CAN HELP YOU FEEL BETTER FAST —AND LEAD TO BIG CHANGES

Each of these habits takes just a few minutes. They are anchored to something you do (or think or feel) so that they are more likely to become automatic. Once you do the behaviors you want, find a way to make yourself feel good about them —draw a happy face, pump your fist, or do whatever feels natural. Emotion helps the brain to remember.

- After I answer the phone, I will stand up and walk while I talk.

- After I start to argue, I will ask myself, Is my behavior getting me what I want?

- When I get out of bed in the morning, I will open the curtains/shades to let the sunshine in.

- When I feel anxious, I will eat a complex carbohydrate, such as a sweet potato, to boost serotonin.

- When I relapse or make a mistake with my health, I will ask myself, What can I learn from my mistake?

- When I am tempted to eat unhealthy foods, I will eat the healthy ones on my plate first.

- When I am dealing with someone who is stuck on a negative thought or arguing, I will ask them to go for a walk with me and will not bring up any charged topic for at least 10 minutes.

- When I want to go out to eat, I will ask the healthiest person I know to go with me.

- When I feel thoughts going over and over in my head, I will write them down, which helps to get rid of them.