CHAPTER 7

OVERCOMING TRAUMA AND GRIEF

ELIMINATE THE HURTS THAT HAUNT YOU

Sometimes the bad things that happen in our lives put us directly on the path to the most wonderful things that will ever happen to us.

NICOLE REED, RUINING YOU

The brain you bring into a trauma will often determine the life that comes out of it.

DANIEL AMEN

On July 16, 2003, Steven, a 33-year-old bicycle repair mechanic working in Santa Monica, California, insisted on having an early lunch. He was not sure why, but he felt drawn to the Santa Monica Farmers’ Market, so he headed there on foot. As he arrived, George Russell Weller, 86, lost control of his 1992 Buick LeSabre and barreled through the three-block-long farmers’ market. Bodies went flying and people screamed as Weller’s car headed straight for Steven. He knew he would be hit. Steven later said, “I thought he was going to run over my legs. . . . I thought I would lose my legs.” At the last possible moment, he managed to jump out of the way. In the chaos, 10 people were killed, and more than 50 were injured. Steven, who had been a military tank commander in the first Gulf War, used the medical skills he had learned to help save others. Still, a woman died in his arms.

Traumatized, Steven went back to work that same day. But for months afterward he couldn’t sleep and couldn’t stop his hands from shaking. By chance —or fate, if you believe in such things —Linda Alvarez, a Los Angeles CBS News anchor, took her bicycle to Steven’s shop shortly after the disaster and discussed it with him in a brief conversation. As they talked, Linda noticed that Steven was shaking. “It started that day,” Steven said, showing her his trembling hands, “and it won’t stop.” The image of Steven’s hands stayed with Linda. A month later, while working on another story, Linda learned about work I was doing with a treatment technique called Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing, or EMDR, planting the seed for a story about the treatment and Steven’s trauma.

EMDR: A POWERFUL TOOL TO FEEL BETTER FAST

EMDR is an effective psychological treatment developed by my friend Francine Shapiro, a psychologist. In 1987, during a walk around a lake, she noticed that a disturbing thought disappeared when her eyes spontaneously started to move back and forth from the lower left to the upper right visual fields. She tried the eye movements again with another anxiety-provoking thought and found that the anxious feeling went away. In the days that followed, Francine tried the technique with friends, acquaintances, and interested students and found that it was helpful in relieving anxiety. She went on to work with patients and developed a technique that is now used worldwide.

This form of therapy is based on research suggesting that traumatic events can prevent the brain from processing information as it normally does, which results in these events getting “stuck” in the brain’s information processing center. Then, when someone who experienced a trauma recalls it, the memory triggers an intense re-experiencing of the original event, complete with all of its upsetting sights, sounds, smells, thoughts, and feelings. New incidents can have the same effect. During EMDR, to “unlock” the brain’s processing center, a client brings up emotionally troubling memories while his or her eyes follow a trained therapist’s hand moving horizontally back and forth. Employing a specific protocol, the clinician helps the client identify the images, negative beliefs, emotions, and body sensations associated with a targeted memory or event. Positive statements and beliefs replace negative ones, and the client rates the believability of a new thought while thinking of the disturbing event.

The goal of EMDR treatment is to help clients rapidly process information about a negative experience and move toward an adaptive resolution. When EMDR is effective, people who undergo it come to understand, both consciously in their minds and unconsciously in the physical functioning of their brains, that the event is in the past and no longer a threat. This means a reduction in distress, a shift from a negative belief to a more positive one, and the possibility of more optimal behavior in relationships and at work. It is often used with people who suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), a lasting emotional response to severe trauma that changes the nervous system.

HEALING MULTIPLE LAYERS OF TRAUMA

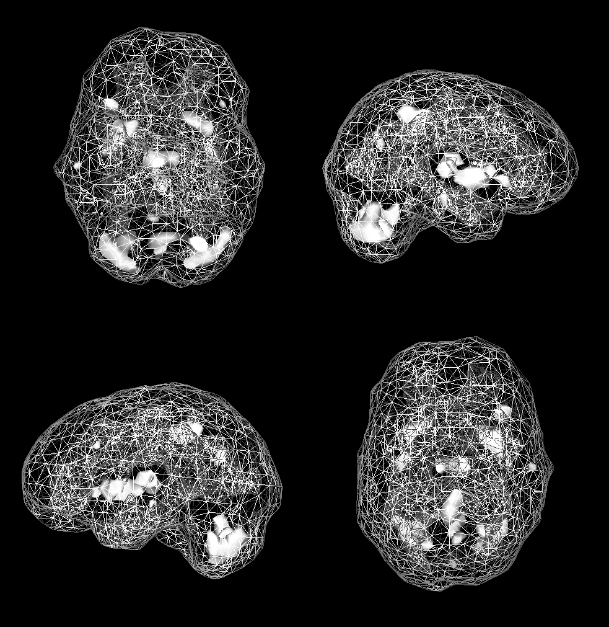

When CBS producer Angeline Chew called to ask if I would be interested in doing a segment about EMDR and using Steven’s story as an example, I was happy to help. I had just finished a study with therapist Karen Lansing on police officers who were involved in shootings and developed PTSD afterward.[177] EMDR was very effective in quickly alleviating the officers’ symptoms, as well as normalizing their brain function on SPECT scans. My colleagues and I have published several brain SPECT imaging studies on posttraumatic stress disorder that show significant increases in activity in the limbic or emotional areas in a pattern that looks like a diamond. The affected brain areas are the anterior cingulate gyrus, which indicates a fixation on negative thoughts or behaviors; the basal ganglia and amygdala, involved with anxiety; and the thalamus, which shows a heightened sensory awareness. In addition, we see increased activity in the right lateral temporal lobe, an area of the brain involved in reading the intentions of other people.

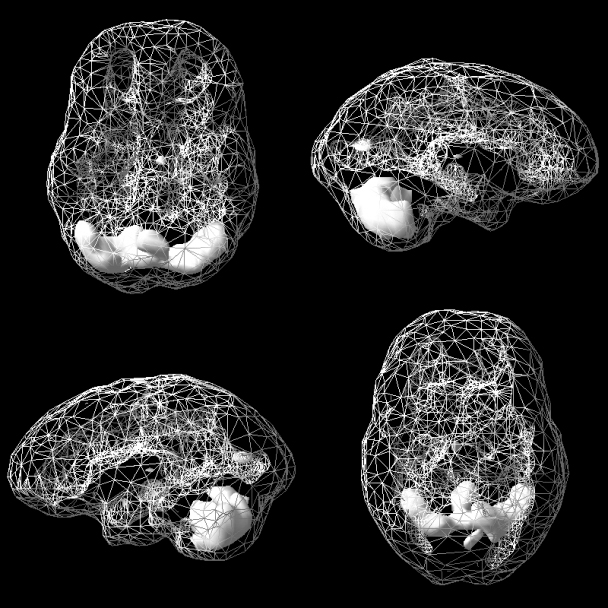

NORMAL “ACTIVE” BRAIN SPECT SCAN

Most active areas are in the cerebellum at the back of the brain.

CLASSIC POSTTRAUMATIC STRESS DISORDER SCAN

“Diamond plus” pattern shows increased activity in the anterior cingulate gyrus (top of diamond), basal ganglia/amygdala (middle), and thalamus (bottom), as well as in the right lateral temporal lobe (indicated by the arrow).

After talking to Steven and discovering that he was willing to participate, we felt he would be a good candidate for EMDR and that his story of healing could be an inspiration to others. As is often the case in people who develop PTSD, Steven had experienced other traumas besides the one at the Santa Monica Farmers’ Market. He grew up in a severely abusive alcoholic home. One of his earliest memories was of his father burning down the family home, and he also remembered that his father had once dangled him over the side of a 400-foot-high bridge. When he was 11, his favorite firefighter uncle died in a fire set by an arsonist, and Steven faced death as a tank commander during the Gulf War. He had many layers of trauma.

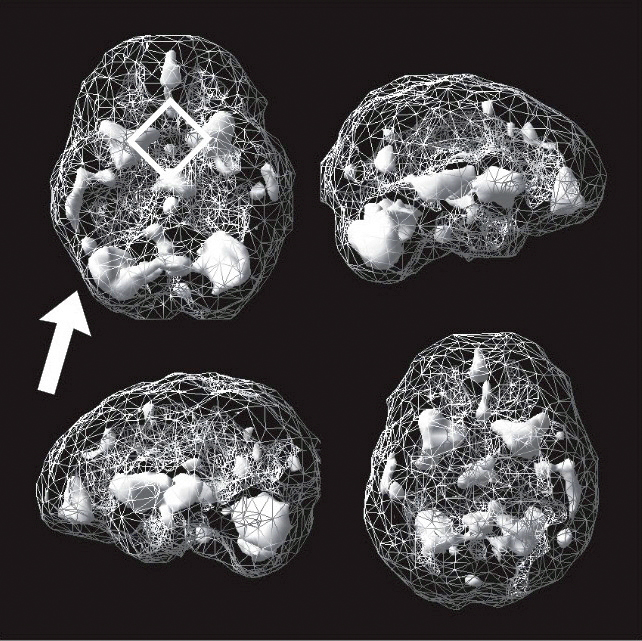

As part of his evaluation, we scanned Steven three times: before treatment, during his first EMDR session, and after eight hours of treatments. Initially, Steven’s brain showed the classic PTSD pattern, with his limbic or emotional brain being extremely hyperactive. Using EMDR with him, we cleared out the traumas one by one. His brain actually showed benefit during the first treatment and was markedly improved after eight hours of treatment (see the scans below). Steven’s shaking subsided, and he felt calmer and less stressed. One of the most healing insights Steven shared with me was that during the process, he started to forgive his father and wondered what his brain might have looked like. Steven had held deep and understandable resentment toward his father, but the brain science gave him a new perspective on himself and his dad. When we helped Steven calm and balance his brain, he was happier and able to sleep better.

STEVEN’S BASELINE “ACTIVE” SPECT SCAN

Strong “diamond plus” pattern

DURING FIRST EMDR SESSION

Calming starting to occur

AFTER EIGHT HOURS OF TREATMENT

Most active areas are in the cerebellum at the back of the brain.

GETTING THE RIGHT DIAGNOSIS IS CRITICAL TO FEELING BETTER FAST

Going through emotional trauma or grief can leave a lasting imprint on the brain. In order to properly heal it, it is critical to get the right diagnosis. In 2015, we published two studies on more than 21,000 patients, including veterans, that demonstrated we could distinguish between PTSD (emotional trauma) and traumatic brain injuries (physical trauma) with high levels of accuracy based on SPECT scans.[178] In January 2016, Discover magazine awarded this research 19th place among the top 100 stories in 2015 in all of science —between Tesla’s entry into the energy market (number 18) and the discovery of a new vegan dinosaur species (number 20). It was critically important because the symptoms of PTSD and traumatic brain injury (TBI) often overlap (anxiety, depression, irritability, headaches, and insomnia), but the treatments are very different. In fact, treating PTSD as if it is a TBI, or vice versa, can actually make people worse, which is why I believe neuroimaging studies are so important when people struggle and find that the simple treatments to feel better fast are ineffective.

Grief is often mislabeled as depression, ADHD, PTSD, panic disorder, and other psychiatric conditions. If you experience symptoms of these conditions after a loss, consider doing grief work before taking medication. If grief is misdiagnosed, psychotropic medications can get in the way of or even prolong recovery.

SEVEN STRATEGIES TO ELIMINATE THE HURTS THAT HAUNT YOU

Brain imaging research has shown that PTSD is associated with hyperactivity in the amygdala and other emotional parts of the brain, but it also leads to decreased activity in parts of the prefrontal cortex (PFC). This means that people who suffer from trauma have heightened fear responses (high amygdala activity) and lower self-control (lower PFC activity). The combination of heightened fear and lowered self-control is a prescription for trouble. Common forms of self-medication, such as alcohol, opiates, marijuana, or a diet laden with sugar and foods that turn to sugar, can help to calm the amygdala and anxiety in the short run, but they also reduce the activity of the PFC even more, giving someone less control over these behaviors. That leads to further trouble, including addictions and obesity.

Research has also found that the brains of those experiencing grief tend to show greater activity in the limbic system and parts of the PFC. The pain of grief is often so brutal that people will do anything to escape it. In so doing —just as for PTSD —they often choose strategies that hurt rather than help them. Alcohol, marijuana, or unhealthy food may lessen the pain for a short while, but unfortunately it returns even worse. Similarly, taking opiates or benzodiazepines, such as Valium or Xanax, can calm the pain briefly but actually will make it worse in the long run.[179]

Integrating my clinical experience with patients, extensive brain imaging work, and the science of healing from trauma and grief (see “Recovering from Grief: Additional Suggestions” on page 166), I’ve come up with seven strategies that will help you feel better fast. Whether you have PTSD because of past trauma, are mourning the loss of a family member or friend, or are dealing with significant stress in your life, the relief will be lasting.

Strategy #1: Consider EMDR (Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing).

As discussed earlier, EMDR is especially helpful in dealing with intrusive memories and anxiety that interfere with joy. It also helps control the triggers that make you feel upset. Initially used for people with PTSD,[180] EMDR has also been shown to be effective for grief,[181] anxiety,[182] panic disorders,[183] depression,[184] chronic pain,[185] phantom limb pain,[186] addictions,[187] and performance enhancement.[188] It was found to be helpful when used in groups of teenagers after the earthquake in Italy in 2016.[189] EMDR is one of the most rapid and effective treatments I have ever personally witnessed. I have my patients keep a journal of the times that are hard for them, then work with an EMDR therapist to help eliminate their anxious reactions. It is important that this technique be done by an EMDR certified therapist. You can find one at the EMDR International Association website (www.EMDRIA.org).

Strategy #2: Try trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT).

TF-CBT was developed in the 1990s by psychiatrist Judith Cohen and psychologists Esther Deblinger and Anthony Mannarino. As they note, trauma can lead to guilt, anger, feelings of powerlessness, self-abuse, acting-out behavior, and mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety. It is common for PTSD to manifest itself with bothersome recurring thoughts about the traumatic experience. Similar to the ANT-elimination strategy discussed in chapter 5 (pages 107–108), the idea of TF-CBT is that learning to correct these thoughts is critical to getting and staying well. TF-CBT has been shown to be particularly effective with children and teens[191] and in group therapy settings,[192] and the results last over time.[193] You can find a TF-CBT therapist at www.tfcbt.org.

Strategy #3: Write the story of what happened in the context of your life.

Narrative exposure therapy (NET) is a brief psychotherapy for trauma developed by Drs. Maggie Schauer, Frank Neuner, and Thomas Elbert that has been shown in studies to be effective.[194] It has been used most often with individuals, groups, and communities that have experienced multiple traumas as a result of political or cultural forces (such as refugee groups or people affected by a natural disaster). NET has been shown to reduce PTSD symptoms after 4 to 10 sessions with a therapist.

The stories people tell themselves about trauma and their lives in general influence their health and well-being. Seeing yourself solely around traumatic experiences leads to lasting feelings of trauma and stress. NET therapy involves writing a chronological story of your life, including detailed accounts of the traumas you have experienced, and reliving the emotions without losing connection with the present moment. You include positive events in your story, which helps add balance and context to what you believe about your life. One of my patients, for example, grew up with an abusive alcoholic mother, but my patient also remembered the times her mother would put towels in the dryer to warm them before getting her and her siblings out of the bathtub. When treatment ends, the therapist will create a documented autobiography for the patient.

NET is different from other treatments in that it focuses on creating an account of what happened in a balanced way that helps to recapture a person’s self-respect. For more information, see the Narrative Exposure Therapy channel on the Vivo International website (www.vivo.org). NET is similar to written exposure therapy (WET), which has also been found to be effective for PTSD.[195]

Strategy #4: Don’t block your painful feelings.

Let painful feelings wash over you, cry or scream (not at others!), and then challenge the thoughts that underlie the feelings to see if they are true. Avoiding painful thoughts, feelings, and memories creates more harm than good in the long run. Many research studies have shown that avoidance increases the likelihood of a host of psychological issues, such as PTSD,[196] depression,[197] anxiety disorders,[198] binge eating,[199] chronic pain,[200] low academic performance,[201] and more. Whenever you are suffering with trauma or grief, write out your feelings or find a friend or therapist you can talk them out to. This can help bring perspective, which often gets lost during emotional crises. Blocking your feelings leads to engaging in negative behaviors to deal with the excess negative emotional energy.

One of my favorite poems about not blocking thoughts or emotions is by Rumi, a 13th-century Persian poet. In “The Guest House,” he describes being human as akin to a guest house that receives new “arrivals” —new emotions —every day. While some of these visitors are positive and some are negative, we can welcome them all, knowing that experiencing them may help us grow. Rumi wrote,

Still, treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out

for some new delight.[202]

Strategy #5: Break the bonds of the past.

One of the most powerful “feel better fast” techniques I’ve used with patients is what I call “breaking the bonds of the past.” It stems from the belief that negative feelings and behaviors are often based on past memories that are either toxic or misinterpreted, and evaluating the truth of these memories can help us feel better. This technique requires only five simple steps. Whenever you have a painful or disruptive memory or feeling, write out the answers to the following questions:

- When was the last time you struggled with the painful or disruptive memory or feeling, experienced it, or felt suffering because of it? Write down the details.

- What were you feeling at the time? Describe the predominant feeling.

- When was the first time you had that feeling? Imagine yourself on a train going backward through time. Go back to when you first experienced the feeling and write down the incident in detail.

- Can you go back even further to a time when you had that original feeling? Write down the details of the original incident.

- If you have a clear idea of the origins of the feelings, can you disconnect them from the past by reprocessing them through an adult or parent mind-set, or reframing them in light of new information? Consciously disconnect the emotional bridge to the past with the idea that what happened in the past belongs in the past, and what happens now is what matters.

Here are three examples of how this can work.

NATE: ADDRESSING PANIC ATTACKS

Nate, 15, came to see me for panic attacks. He had several episodes a day when he felt as if he were choking or drowning. His breathing became shallow, fast, and labored. His heart raced, he broke out in a sweat, and he felt as though he were dying. Nate hated these episodes. The fear of having them was so overwhelming that he stopped going to school. I went through the following steps with him during our second visit.

- Tell me about the last time you had a panic attack. Nate said it was the day before. He was eating dinner when all of a sudden he felt as if he were starting to choke, and he had all the familiar awful symptoms —a sense of suffocation, racing heart, sweating, and feeling as if he were going to die.

- Tell me what you were feeling at the time. Describe the predominant feeling. Nate said he felt as though he were going to die.

- Imagine yourself on a train going backward through time. Go back to a time when you first had that feeling. I asked Nate to go back in time to remember the first time he felt he was going to die. He sat there for a minute and then started to choke. I thought he was having a panic attack in front of me. I asked him to breathe slowly and tell me what was going on. He slowed his breathing, wiped his brow, and told me about a time when he was six years old. He was sitting at a lunch table at school and accidentally swallowed a plastic wrapper from a candy bar. He started to choke on the wrapper. Initially no one saw him. He couldn’t breathe, and no one noticed. He thought he was going to die. After what seemed an eternity, a teacher saw him and did the Heimlich maneuver on him, dislodging the wrapper. Nate said he had forgotten about the event until now.

- After he settled down and composed himself, I asked him to go back even further in his mind to see if there was an earlier time when he had the feeling he was going to die. He closed his eyes and said he remembered a time when he was very young. He was coming out of somewhere dark into a place filled with bright lights, lights that felt hot. People were moving around. He felt fear. He couldn’t breathe, and something awful covered his face. He felt as though he were going to die. To my amazement, Nate had just described a birth experience. When he opened his eyes, I asked him if he knew anything about his birth. He said no, no one had ever talked to him about it. I asked his mother to come into the room, and then I asked her about his birth experience. She told me that he was a meconium baby (this means the infant’s feces get into the amniotic fluid, which is very dangerous for the newborn). He was born blue and had to be resuscitated by the doctor. His mother said she had never talked about it with Nate because she didn’t want to worry him.

- Break the bonds of the past through an adult or parent mind-set, or reframe them in light of new information. With Nate’s mother in the room, I took him back to both of those times. First, with the birth experience, I had the teenage Nate go back and explain to the baby what had happened. The baby was in trouble for a short time, but the doctors helped clean him up so he could breathe normally. I then took him through the candy wrapper incident and had the teenage Nate tell six-year-old Nate that he is grateful to the teacher who helped him and that he is alive, well, and healthy (and he needed to stop eating candy wrappers).

After that session, Nate’s panic attacks disappeared. I saw him a few more times, but essentially disconnecting his present symptoms from the past sensitizing event took care of them.

CHUCK: GETTING FREE FROM IMPOTENCE

Chuck, 35, came to see me for impotence. He felt he was going to lose the woman he loved, who was getting frustrated over the issue.

- Tell me about the last time you were impotent. Two nights ago.

- Tell me what you were feeling at the time. Describe the predominant feeling. Chuck said, “I feel as if I am a failure.”

- Imagine yourself on a train going backward through time. Go back to a time when you first had that feeling. I asked Chuck to go back in time to when he first felt as if he were a failure. After about two minutes he started to sob. As he gained a measure of control, he told me of a time when he was seven years old and having trouble with his homework, especially reading. His father repeatedly hit him, called him stupid, and told Chuck he would never amount to anything. He would be a failure. Chuck said he had completely blocked the memory until that moment.

- I then asked Chuck to go back even further in his mind to see if there was an earlier time when he felt like a failure. After several minutes, he said no.

- Break the bonds of the past through an adult or parent mind-set, or reframe them in light of new information. I took Chuck back to the traumatizing incident and had the adult Chuck talk to his seven-year-old self. His father didn’t understand dyslexia, which Chuck was diagnosed with in the fourth grade. Once he was diagnosed, his father became more understanding and supportive.

After that session, Chuck’s issue with impotence was resolved, which improved his relationship.

JENNY: OVERCOMING ANNOYANCE AND ALCOHOLISM

Jenny, 42, struggled with alcohol use and lost her marriage in the process. During her recovery, she joined the Christian program Celebrate Recovery. She found that when she went, she usually showed up at meetings 30 minutes late to avoid the worship music. I asked her why.

- Tell me about the last time you were late to a meeting. A week ago.

- Tell me what you were feeling at the time. Describe the predominant feeling. Jenny said, “Annoyed.”

- Imagine yourself on a train going backward through time. Go back to a time when you first had that feeling. I asked Jenny to go back in time to when she first felt annoyed. After about 30 seconds, she said, “About age seven, when my mother wanted me to enter piano contests. I spent hours and hours practicing. Initially, I loved it, but the pressure was insane. All I did was go to school, practice music, and go to church. My dad was the minister, and my mom played the piano. And it went on and on for like 20 hours. There were times I would fall asleep in church and then get beaten with the belt when I got home.” “No wonder you get annoyed with the music at church,” I replied. Jenny laughed.

- I then asked Jenny to go back even further in her mind to see if there was an earlier time when she felt annoyed. After several minutes, she said there was a time when she was three when her father hit her mother and broke her lip, splattering blood all over Jenny’s new clothes. It made her feel really annoyed.

- Break the bonds of the past through an adult or parent mind-set, or reframe them in light of new information. Jenny’s adult self talked to her three- and seven-year-old selves. She told them her mom and dad were not healthy and had no business raising children under that level of stress. But she did not have to be like her parents and could start to enjoy the music at church. What happened in the past belongs in the past, and what happens now is what matters.

Jenny’s recovery has gone much better, and Celebrate Recovery is an integral part of her program.

Note: If this process brings up painful memories that do not go away in a short period of time, seek professional help from a licensed psychotherapist.

Strategy #6: Strive for “posttraumatic growth.”

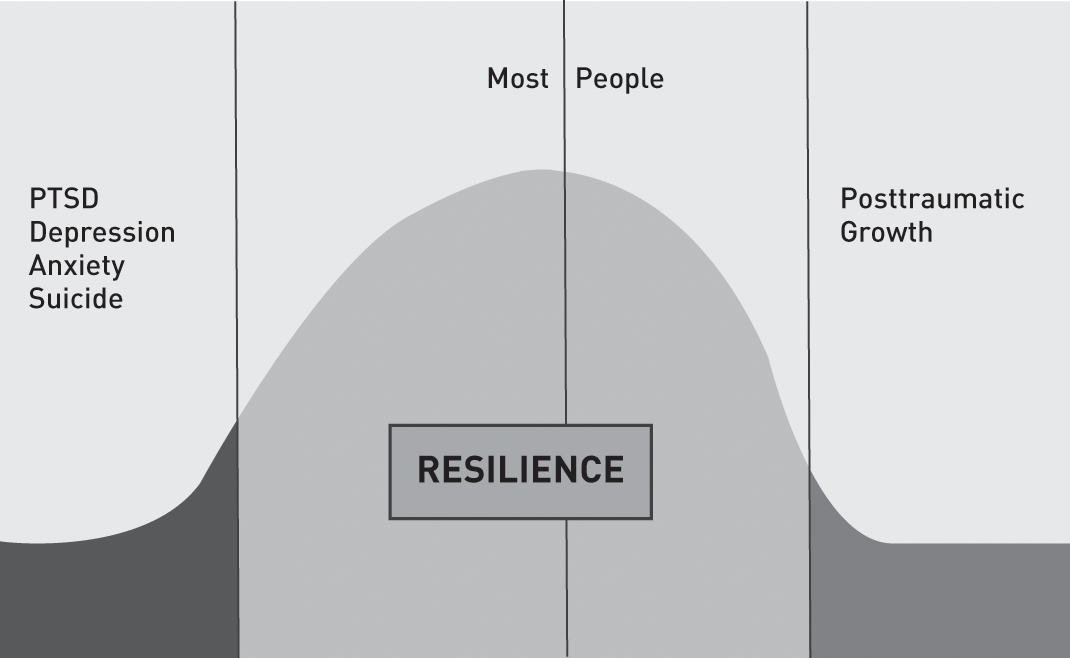

One of the most exciting areas of trauma research is in posttraumatic growth (PTG). The term was coined in the mid-1990s by psychologists Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte.[203] According to Dr. Tedeschi, as many as 90 percent of trauma survivors report at least one aspect of posttraumatic growth, such as a renewed appreciation for life. Whenever a group of people are traumatized, about 10 percent will develop PTSD, while 80 percent will return to their normal baseline within a few months. Another 10 percent will actually be stronger than they were before the trauma happened —those who experience PTG.

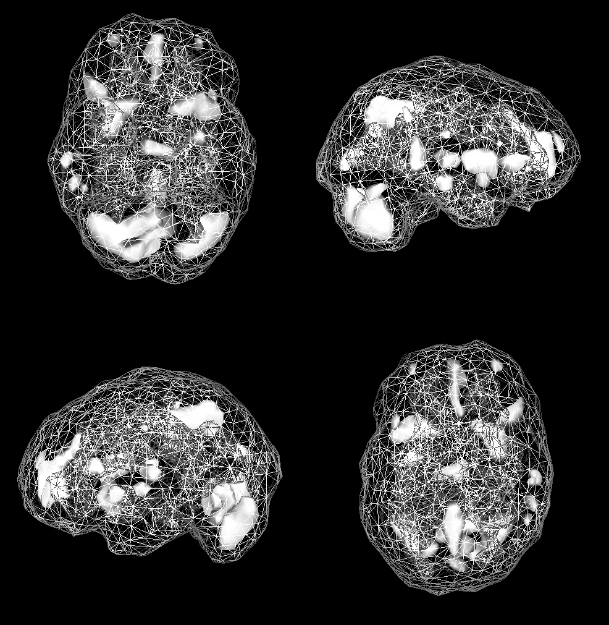

POSTTRAUMATIC GROWTH CURVE

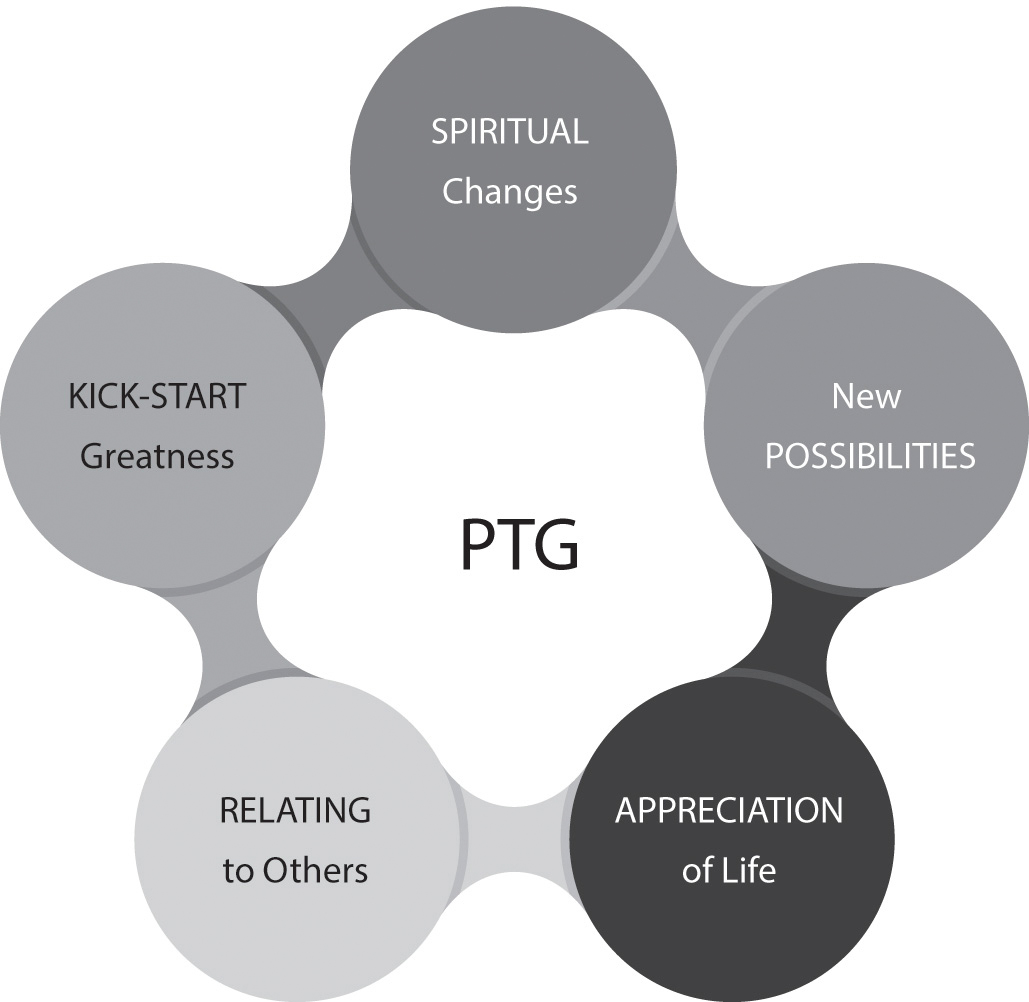

Research suggests that PTG is based on five factors that can improve symptoms of distress.[204] I’ve adapted them slightly to form the acronym SPARK:

- A deepening of spiritual life, including a significant change in one’s belief system or a new or stronger sense of meaning and purpose. Martin Luther gave his life to God and a religious order after he survived a life-threatening thunderstorm.

- Seeing new possibilities because of the trauma or grief. New opportunities have emerged from the situation, opening up possibilities that were not present before. One of my friends, for instance, lost her daughter to a drunk driver and now has traveled the country helping other families who have had similar experiences.

- Increased appreciation of life in general; becoming better at appreciating each moment. After a near-death experience, one of my patients lost her fear of death but also started putting in fewer hours at work to spend more time with her family.

- A change in relationships or relating to others in more meaningful ways than before the trauma occurred. There is an increased sense of connection, and people appreciate family and friends more. One of my friends who has experienced many challenges parenting a child with autism started Talk About Curing Autism, a support group with more than 50,000 members. She has a huge group of new friends who bring meaning and purpose to her life.

- Kick-start greatness through increased personal strength. This is seen in expressions such as “If I lived through that, I can live through anything!”

COMPONENTS OF POSTTRAUMATIC GROWTH

Eight sessions of EMDR helped to promote PTG in survivors of the large-scale ferry disaster that occurred in the Yellow Sea off South Korea in April 2014.[205] To encourage PTG in yourself, look back over your own traumas and, using these five criteria, ask yourself how your life may have changed in a positive way as a result of those events.

CHARLEY: THE HEALTHIEST PERSON I’VE EVER MET

Charley had anxiety and trouble breathing when he first came to see me. The 16-year-old had a condition known as Goldenhar syndrome, a deformity that usually affects just one side of the face. He was born without his left jawbone and had undergone 21 surgeries to fix the deformity, leaving his face scarred and looking like an old railroad yard. His panic started when the doctor put the anesthesia mask over his face for the 20th surgery. His mother brought Charley to see me. He had always been a resilient boy, and she was worried because he had at least two more surgeries to go. A few sessions of hypnosis easily cleared up his anxiety.

As I got to know Charley, I came to believe that despite his anxiety, he was the healthiest person I had ever met. He was president of his 10th-grade class, got straight As in school, and had a girlfriend he adored. He also had clear goals and a great attitude. After his anxiety had lifted, I continued to see him at no cost. For the most part, doctors study illness, not resilience, but I had to know why he was so healthy despite his circumstances. I came to believe that there were five reasons for Charley’s emotional strength, which paralleled the research of PTG.

- Spiritual changes: Charley had a deep sense of purpose and believed he was on the planet to make it better.

- Possibilities: Because of his experience, Charley had developed great empathy for others who suffered, and he was considering training to be a physician to help others like himself.

- Appreciation of life: Charley loved life. Each year he found he was more competent in school and relationships and more excited about his future.

- Relationships: He developed close relationships, especially with his mother, even though she never allowed his disability to be an excuse for anything. She suffered for her son, but early in his life she realized that babying him would only handicap him. Charley still did chores, was expected to do well at school, and participated with other kids even when they made fun of him. She helped him rehearse what to say when other kids were cruel, which they were. When he didn’t get upset by the teasing, the other kids became his friends and protected him against any further teasing.

- Kick-start greatness through personal strength: Charley was an optimist. In listening to him speak, I found that he almost always saw the positive side of things. He did not see his condition as a handicap. When we talked about it, he said everyone has something. “This is my problem. At least I don’t have cancer.”

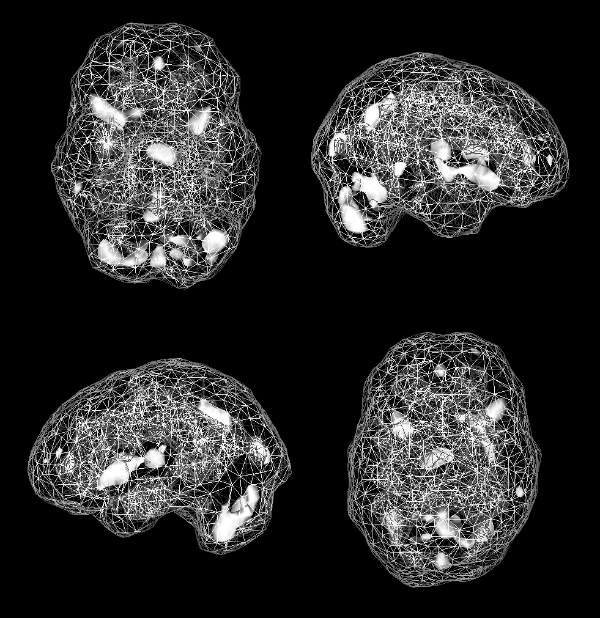

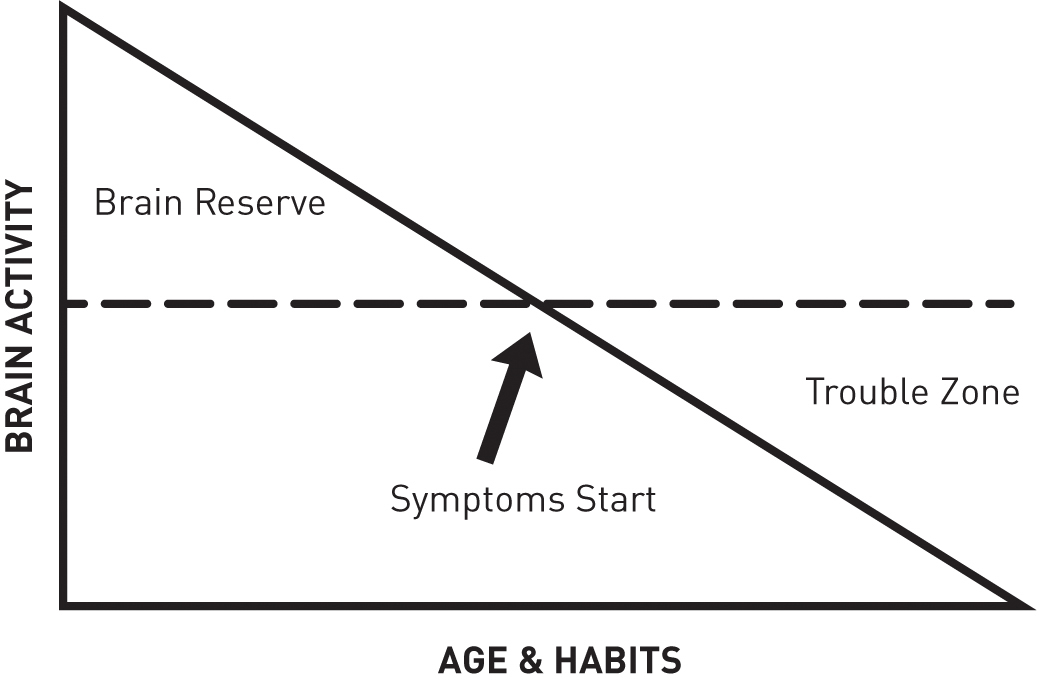

THE IMPORTANCE OF BRAIN RESERVE

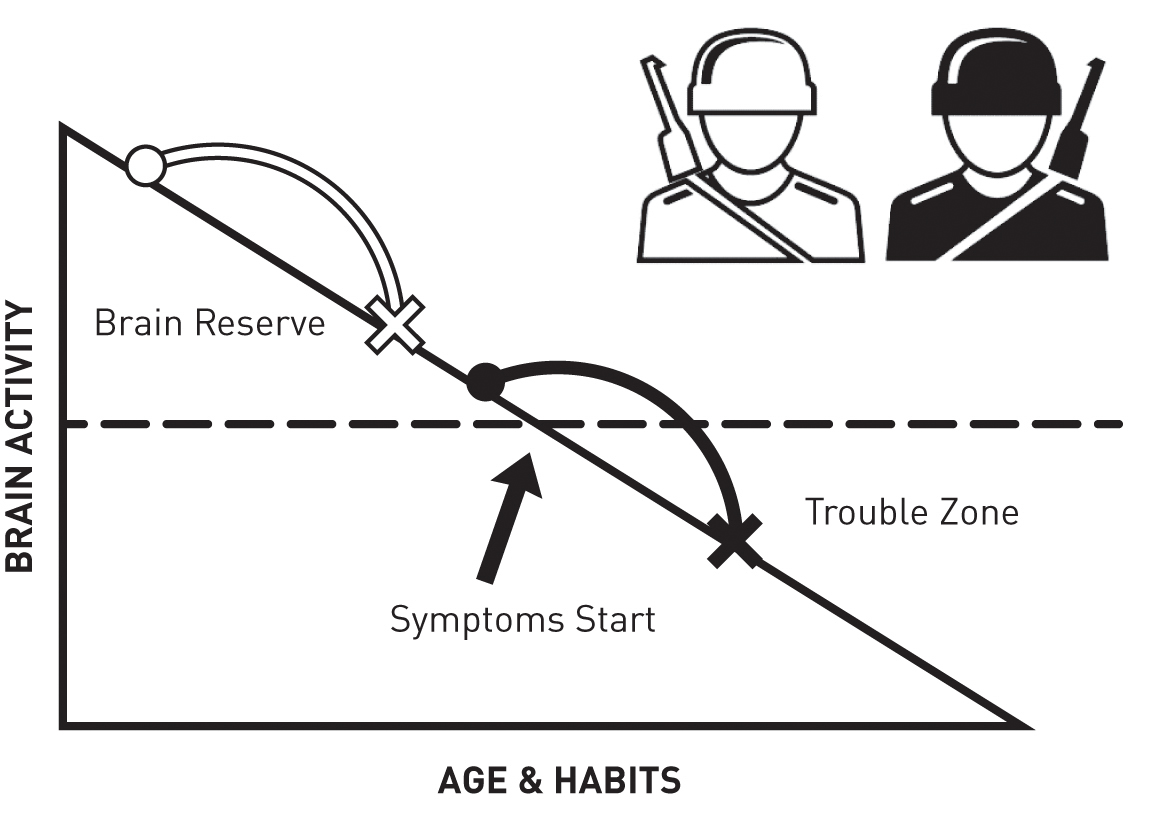

Another explanation for PTG is a concept I call brain reserve. Brain reserve is the extra cushion of brain function you have that helps you deal with whatever stresses come your way. The more reserve you have, the more resilient you are and the less impact trauma and grief will have on your life. To explain brain reserve to my patients, I often go to the whiteboard in my office and draw the image below.

THE CONCEPT OF BRAIN RESERVE

When you were conceived, your brain had a lot of potential for reserve, but if your mom smoked, ate unhealthy food, was chronically stressed, or had infections, your reserve was being depleted even before you were born. If, however, your mother was healthy, ate well, took her vitamins, and was not terribly stressed, she was helping to increase your reserve. Over the course of the rest of your life, you are either increasing or decreasing your brain reserve. If, for example, you fell down a flight of stairs at age three and hit your head, even if you had no symptoms, you decreased your reserve. If you started smoking marijuana as a teenager, you decreased your reserve further, and if you played tackle football or hit a lot of soccer balls with your head, you have even less reserve —even though you might not yet be symptomatic.

Think of it this way: Take two soldiers engaged in a war who are in the same tank and are both exposed to the same blast injury at the same angles. One of them walks away psychologically unharmed, while the other is permanently disabled by trauma. Why? It depends on the level of brain reserve that each of them had prior to the accident. One soldier had more reserve because he took good care of his brain, his parents fed him well, he had lots of educational opportunities, and he didn’t play football. The other soldier started lower on the line with less reserve. Both soldiers are effective at their jobs, but they started at different places. Even though the blast diminished the reserve of both, the one with a higher reserve remained functional.

WHY SOME WALK AWAY FROM ACCIDENTS UNHARMED AND OTHERS DO NOT

Most of the people we see at the Amen Clinics start below the dotted line and are symptomatic. Getting well is not just about becoming symptom-free; it’s also about boosting your brain reserve and getting back above the line. That requires the three simple strategies discussed in chapter 2 (pages 30–44): developing brain envy (you have to really care about your brain); avoiding anything that hurts your brain; and engaging in regular brain-healthy habits. Every day you are either boosting or stealing from your brain’s reserve; you are either aging your brain or rejuvenating it. When you truly understand this concept, you will have a lot more influence over how you deal with trauma and grief.

Strategy #7: Consider using the hormone oxytocin, which has been found to be helpful for both grief and emotional trauma.

Oxytocin is produced in both women and men. Although it’s often associated with female reproduction, more recently it has become known as “the love hormone,” as it brings forth feelings of trust, security, connection, calmness, and contentment. I first became aware of oxytocin’s unique ability to help with trauma and grief after reading a book by Dr. Ken Stoller, who worked with us at Amen Clinics for several years. In Oxytocin: The Hormone of Healing and Hope, Ken wrote about his own firsthand experience with oxytocin and grief. His 16-year-old son, Galen, had been killed in a train accident, and Ken was overwhelmed with what he termed pathological grief —a mixture of debilitating fear, anxiety, and panic permeating his grief. He was consumed with obsessive thoughts about how Galen had died and what he might have experienced in his last moments.

Ken had been prescribing oxytocin to treat fear and anxiety in children on the autism spectrum, but it was several weeks before he realized that it might help him as well. His greatest fear and panic were during the predawn hours, when he would have terrible nightmares. He wrote,

One night, I set my alarm to wake up before this period and dosed myself with oxytocin, and the outcome felt nearly miraculous. The severity of obsessive negative thoughts during this acute grieving period was altered within minutes after the application of an oxytocin nasal spray. Whereas before I had to breathe through this emotionally difficult hour as if I were in a Lamaze class, that survival strategy became unnecessary with the use of oxytocin. This time, I was actually able to play music until the sun came up.

It took about ten minutes to experience the full effect, and with each passing minute a great sense of emotional equanimity took place. The panic and fear dropped away from me as if I were shedding clothing. If I wanted to think about my son’s train accident, I could. But the moment I didn’t want to think about it, the accident faded into the background of my mind. It wasn’t there hammering away at me as if it had a life of its own. By successfully diverting these negative feelings from wherever they would have taken me, I was able to process my grief without the interference of negative obsessions. This was invaluable, to say the very least, and kept me from developing severe post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) . . . because that was certainly where I was headed.[206]

Oxytocin helped Ken get through the worst of his emotional pain, and he was able to stop using it after a few weeks. He has since prescribed oxytocin for other patients facing grief and has seen it benefit each one.

Other researchers have also recently shown the benefit of oxytocin for trauma.[207] Dr. J. L. Frijling and colleagues from Holland found that giving intranasal oxytocin calmed the fear circuit in the brain (amygdala) and decreased the symptoms of acute PTSD.[208] Oxytocin has also been shown to increase compassion in people who suffer with emotional trauma.[209] Any physician can write a prescription for it, and most compounding pharmacies can make the intranasal or sublingual (under the tongue) form. The typical adult dosage is 10–40 IUs two to three times a day. Dr. Stoller and others recommend it for short-term use only, as long-term use has the potential to change oxytocin receptors in the brain.

RECOVERING FROM GRIEF: ADDITIONAL SUGGESTIONS

The emotion of grief affects nearly all of us at some point in life. Eight million people become new grievers every year due to the death of someone they love. Nearly 50 percent of marriages end in divorce, leaving the broken couple, their children, and their families grieving.

Grief is the normal response to a significant loss. And it is often accompanied by regret and the pain of being unable to connect with someone (or something) who has been there for you for a period of time. Other common symptoms of grief include sadness, trouble concentrating, memory problems, insomnia, irritability, diarrhea, headaches, a loss of appetite, and feeling numb. Complicated grief, which is marked by intense and ongoing longing for the departed, is often associated with conflicting feelings —happiness that a loved one is no longer suffering, but yearning because you miss him or her terribly.

But grief is not just about losing a loved one to death, divorce, an empty nest, or another method. It can occur after losing one’s health, freedom, financial stability, a home, a job or career (with retirement), or even following a loss of trust or safety. When parents have a disabled child, they often experience intense grief over the loss of what they had dreamed for their son or daughter. Losing pets is also extremely painful for many people. One of the only times I’ve seen my very tough father cry was when he lost Vinnie, his dog and best friend of nine years.

The symptoms of unresolved grief may include

- Inability to accept the loss

- Emotional numbness

- Unwillingness to think or talk about someone who has died, or a loss you experienced

- Happy memories that frequently turn painful

- Talking only about the positive aspects of the relationship and ignoring the negative ones

- Talking only about the negative aspects of the relationship and ignoring the positive ones

- Feeling life is meaningless

- Loss of identity or purpose

- Inability to perform tasks of daily living

- Delusions or hallucinations

Be Intentional with Overcoming Grief

Overcoming grief takes time because humans are wired for connection. We become attached to others because that helps us to survive and thrive. When someone we are attached to goes away, either by death or by choice, our emotional brains become overfired through looking for him or her, leaving us vulnerable to depression. Therefore, to overcome grief we must be intentional. Healing will be easier if your brain is better, so make sure to keep a watchful eye on behaviors that either help healing or prevent it. Here are some simple additional steps:

- Start as soon as possible. People may tell you to wait, but if you fell and broke your arm, when would you want to start healing? Immediately! There’s no advantage to putting off the healing process.

- Keep a brain-healthy routine. It’s especially important to eat brain-healthy food, take supplements, exercise, and sleep.

- Discover what was left unsaid or unfinished, and write it down. That way it will not endlessly spin in your mind. Talk to others about what you wish had been different so you can learn from it.

- Be on the alert for an ANT invasion —especially the Guilt-Beating and Blaming species (see chapter 5, pages 102–106).

- Write out the story of what happened. Each day for four days, spend 15 minutes getting the story out, making sure to list both the positives (“He is no longer suffering”) and negatives (“I miss her so much it hurts”) of the situation. Writing has helped children and refugees deal with grief,[210] and it has been shown to decrease feelings of loneliness and help improve mood.[211] In one study, bereaved people who had lost someone to an accidental death or homicide wrote for 15 minutes a day for four days, either about the loss or about something trivial. Afterward, those who had written about the loss reported less anxiety and depression and greater grief recovery than those who had written about trivialities.[212]

- Reach out for social support. Therapy and support groups can help you build skills to overcome grief.

- Breathe with your belly. When you get anxious or short of breath, belly breathing can help you calm down or catch your breath (see chapter 1, pages 14–16).

- Consider supplements. As discussed in the last chapter, loss and rejection are felt in the same part of the brain as physical pain. Supplements such as s-adenosyl-methionine (SAMe), curcumins, magnesium, and omega-3 fatty acids help physical pain and may also help emotional pain.

- Get any chest pain checked out. Chest pain is particularly common in grief.[213] Stress hormones can make our hearts beat in an abnormal rhythm,[214] which can cause chest pain. When I went through a period of grief, my chest hurt so badly I thought I had heart disease. I didn’t. But after my assistant Kim lost her fiancé to a heart attack, she started to have chest pain. When she had it evaluated, the doctors discovered her coronary arteries were more than 90 percent blocked. She did have heart disease, which responded very well to treatment. It turned out that the death of her fiancé may have saved her life. If you experience chest pain, get a physical. If your heart is fine, practicing deep breathing, hand warming, guided imagery, and hypnosis can calm your brain, as can taking 250–400 mg of magnesium glycinate two to three times a day.

- Deal with triggers as they come up. Getting triggered is particularly common in grief, especially when the person or pet you lost can occupy every fun place in your brain. Whenever you get triggered by an anniversary, birthday, holiday, place, song, or smell, don’t try to block the feeling. Allow it to wash over you, cry if tears start to flow, and let yourself be grateful for the memory. Make sure to correct any negative thoughts that tag along with the painful feelings.

- Be patient. No one does grief perfectly. I lost someone important to me about 12 years ago. I knew many of the right things to do, but I still suffered for several months and could not get the person out of my head. Ultimately, reading Byron Katie’s book Loving What Is, which elegantly teaches you not to believe every stupid thought you have, was incredibly helpful. Be patient and forgive yourself as you work through the hard times.

What Would the Other Person Want for You?

Recently, my wife, Tana, and I took our 14-year-old daughter Chloe to see the movie The Shack. It’s a beautiful movie but hard to watch because it’s about a little girl who is kidnapped and killed by a sex offender. A parent’s greatest fear is losing a child, and this was particularly upsetting for Tana. During an episode of The Brain Warrior’s Way Podcast that we record together, Tana said, “Losing Chloe has always been my biggest fear. Why? Because I not only love her, I’m a sheepdog and protective by nature. It’s my responsibility to protect her. The Shack is about forgiveness, and as I watched, I kept wrestling with myself [about what I would do if this happened to Chloe]. No, I wouldn’t be able to do it. Then the movie would make an impactful point, and I would waver . . . I’d forgive this person. Then, all of a sudden, I’m back to No, I wouldn’t be able to do it . . . I’m watching this with my daughter, and she saw me crying and she looked at me; it was almost like she could read my mind. She said something so powerful to me.”

What Chloe had said to Tana was this: “I know you’re thinking that you would want to go find that person and do something awful to him. You can’t do that; I’m telling you, you can never do that.”

Tana was stunned and said, “You can’t say that . . . you can’t say that . . . take it back.”

Chloe responded, “No, you can’t, because I would be so disappointed. I would be so upset.”

Tana said, “Take it back right now.”

Chloe said, “No, because if I did have any way of knowing, I would be so disappointed, because it would ruin your life. The only thing that would ever make me happy is knowing you found some way to make sense of it and some way to be happy again.”

When my patients are experiencing grief, I often ask them what their loved one would have wanted for them: “Would they want you to spend your life angry, miserable, and seeking revenge; or would they want you to find peace? Would they want you to find love and joy?” Chloe’s message to her mother blew my mind.

Grief and trauma, at varying levels of intensity, are an inescapable part of the human experience. But we don’t have to passively endure the suffering that comes with them. The strategies I’ve talked about in this chapter will help you get a handle on your pain and begin to feel better.

SEVEN STRATEGIES TO ELIMINATE THE HURTS THAT HAUNT YOU

- Consider Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR).

- Try trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy (TF-CBT).

- Write the story of what happened in the context of your life.

- Don’t block your painful feelings.

- Break the bonds of the past.

- Strive for “posttraumatic growth.”

- Consider using oxytocin, which has been found to be helpful for both grief and emotional trauma.

TINY HABITS THAT CAN HELP YOU FEEL BETTER FAST—AND LEAD TO BIG CHANGES

Each of these habits takes just a few minutes. They are anchored to something you do (or think or feel) so that they are more likely to become automatic. Once you do the behaviors you want, find a way to make yourself feel good about them—draw a happy face, pump your fist, or do whatever feels natural. Emotion helps the brain to remember.

- Whenever I feel upset, I will cross my arms and stroke down from my shoulders to my lower forearms. (This stimulates both sides of the brain and helps to have a calming effect on the mind.)

- When I feel a wave of a traumatic memory or grief coming on, I will observe myself and write down any negative thoughts that come to my mind and challenge them.

- When painful memories from the past get stuck in my brain, I will write them out from an adult perspective, which can stop the thoughts from circling in my head.

- When I struggle with grief or a traumatic memory, I will read Rumi’s poem “The Guest House.”

- When I feel anxious, I will practice five diaphragmatic breaths to calm myself.

- When memories of a traumatic event surface, I will ask myself what I am thinking or feeling. Then in my mind, I will go back to the very first time in my life that I can remember thinking those thoughts or feeling those feelings to see if my past is infecting the present. If it is, I will say to myself, “That was then and this is now.”

- When a lost loved one’s birthday (or other anniversary) arrives, I will spend time recalling happy memories and be grateful for the time we had together.

- When I feel upset or lonely, I will call a friend and ask for his or her support.